User login

Can US “pattern recognition” of classic adnexal lesions reduce surgery, and even referrals for other imaging, in average-risk women?

Gupta A, Jha P, Baran TM, et al. Ovarian cancer detection in average-risk women: classic- versus nonclassic-appearing adnexal lesions at US. Radiology. 2022;212338. doi: 10.1148/radiol.212338.

Expert commentary

Gupta and colleagues conducted a multicenter, retrospective review of 970 adnexal lesions among 878 women—75% were premenopausal and 25% were postmenopausal.

Imaging details

The lesions were characterized by pattern recognition as “classic” (simple cysts, endometriomas, hemorrhagic cysts, or dermoids) or “nonclassic.” Out of 673 classic lesions, there were 4 malignancies (0.6%), of which 1 was an endometrioma and 3 were classified as simple cysts. However, out of 297 nonclassic lesions (multilocular, unilocular with solid areas or wall irregularity, or mostly solid), 32% (33/103) were malignant when vascularity was present, while 8% (16/184) were malignant when no intralesional vascularity was appreciated.

The authors pointed out that, especially because their study was retrospective, there was no standardization of scan technique or equipment employed. However, this point adds credibility to the “real world” nature of such imaging.

Other data corroborate findings

Other studies have looked at pattern recognition in efforts to optimize a conservative approach to benign masses and referral to oncology for suspected malignant masses, as described above. This was the main cornerstone of the International Consensus Conference,2 which also identified next steps for indeterminate masses, including evidence-based risk assessment algorithms and referral (to an expert imager or gynecologic oncologist). A multicenter trial in Europe3 found that ultrasound experience substantially impacts on diagnostic performance when adnexal masses are classified using pattern recognition. This occurred in a stepwise fashion with increasing accuracy directly related to the level of expertise. Shetty and colleagues4 found that pattern recognition performed better than the risk of malignancy index (sensitivities of 95% and 79%, respectively). ●

While the concept of pattern recognition for some “classic” benign ovarian masses has been around for some time, this is the first time a large United States–based study (albeit retrospective) has corroborated that when ultrasonography reveals a classic, or “almost certainly benign” finding, patients can be reassured that the lesion is benign, thereby avoiding extensive further workup. When a lesion is “nonclassic” in appearance and without any blood flow, further imaging with follow-up magnetic resonance imaging or repeat ultrasound could be considered. In women with a nonclassic lesion with blood flow, particularly in older women, referral to a gynecologic oncologic surgeon will help ensure expeditious treatment of possible ovarian cancer.

- Boll D, Geomini PM, Brölmann HA. The pre-operative assessment of the adnexal mass: the accuracy of clinical estimates versus clinical prediction rules. BJOG. 2003;110:519-523.

- Glanc P, Benacerraf B, Bourne T, et al. First International Consensus Report on adnexal masses: management recommendations. J Ultrasound Med. 2017;36:849-863. doi: 10.1002/jum.14197.

- Van Holsbeke C, Daemen A, Yazbek J, et al. Ultrasound experience substantially impacts on diagnostic performance and confidence when adnexal masses are classified using pattern recognition. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2010;69:160-168. doi: 10.1159/000265012.

- Shetty J, Reddy G, Pandey D. Role of sonographic grayscale pattern recognition in the diagnosis of adnexal masses. J Clin Diagn Res. 2017;11:QC12-QC15. doi: 10.7860 /JCDR/2017/28533.10614.

Gupta A, Jha P, Baran TM, et al. Ovarian cancer detection in average-risk women: classic- versus nonclassic-appearing adnexal lesions at US. Radiology. 2022;212338. doi: 10.1148/radiol.212338.

Expert commentary

Gupta and colleagues conducted a multicenter, retrospective review of 970 adnexal lesions among 878 women—75% were premenopausal and 25% were postmenopausal.

Imaging details

The lesions were characterized by pattern recognition as “classic” (simple cysts, endometriomas, hemorrhagic cysts, or dermoids) or “nonclassic.” Out of 673 classic lesions, there were 4 malignancies (0.6%), of which 1 was an endometrioma and 3 were classified as simple cysts. However, out of 297 nonclassic lesions (multilocular, unilocular with solid areas or wall irregularity, or mostly solid), 32% (33/103) were malignant when vascularity was present, while 8% (16/184) were malignant when no intralesional vascularity was appreciated.

The authors pointed out that, especially because their study was retrospective, there was no standardization of scan technique or equipment employed. However, this point adds credibility to the “real world” nature of such imaging.

Other data corroborate findings

Other studies have looked at pattern recognition in efforts to optimize a conservative approach to benign masses and referral to oncology for suspected malignant masses, as described above. This was the main cornerstone of the International Consensus Conference,2 which also identified next steps for indeterminate masses, including evidence-based risk assessment algorithms and referral (to an expert imager or gynecologic oncologist). A multicenter trial in Europe3 found that ultrasound experience substantially impacts on diagnostic performance when adnexal masses are classified using pattern recognition. This occurred in a stepwise fashion with increasing accuracy directly related to the level of expertise. Shetty and colleagues4 found that pattern recognition performed better than the risk of malignancy index (sensitivities of 95% and 79%, respectively). ●

While the concept of pattern recognition for some “classic” benign ovarian masses has been around for some time, this is the first time a large United States–based study (albeit retrospective) has corroborated that when ultrasonography reveals a classic, or “almost certainly benign” finding, patients can be reassured that the lesion is benign, thereby avoiding extensive further workup. When a lesion is “nonclassic” in appearance and without any blood flow, further imaging with follow-up magnetic resonance imaging or repeat ultrasound could be considered. In women with a nonclassic lesion with blood flow, particularly in older women, referral to a gynecologic oncologic surgeon will help ensure expeditious treatment of possible ovarian cancer.

Gupta A, Jha P, Baran TM, et al. Ovarian cancer detection in average-risk women: classic- versus nonclassic-appearing adnexal lesions at US. Radiology. 2022;212338. doi: 10.1148/radiol.212338.

Expert commentary

Gupta and colleagues conducted a multicenter, retrospective review of 970 adnexal lesions among 878 women—75% were premenopausal and 25% were postmenopausal.

Imaging details

The lesions were characterized by pattern recognition as “classic” (simple cysts, endometriomas, hemorrhagic cysts, or dermoids) or “nonclassic.” Out of 673 classic lesions, there were 4 malignancies (0.6%), of which 1 was an endometrioma and 3 were classified as simple cysts. However, out of 297 nonclassic lesions (multilocular, unilocular with solid areas or wall irregularity, or mostly solid), 32% (33/103) were malignant when vascularity was present, while 8% (16/184) were malignant when no intralesional vascularity was appreciated.

The authors pointed out that, especially because their study was retrospective, there was no standardization of scan technique or equipment employed. However, this point adds credibility to the “real world” nature of such imaging.

Other data corroborate findings

Other studies have looked at pattern recognition in efforts to optimize a conservative approach to benign masses and referral to oncology for suspected malignant masses, as described above. This was the main cornerstone of the International Consensus Conference,2 which also identified next steps for indeterminate masses, including evidence-based risk assessment algorithms and referral (to an expert imager or gynecologic oncologist). A multicenter trial in Europe3 found that ultrasound experience substantially impacts on diagnostic performance when adnexal masses are classified using pattern recognition. This occurred in a stepwise fashion with increasing accuracy directly related to the level of expertise. Shetty and colleagues4 found that pattern recognition performed better than the risk of malignancy index (sensitivities of 95% and 79%, respectively). ●

While the concept of pattern recognition for some “classic” benign ovarian masses has been around for some time, this is the first time a large United States–based study (albeit retrospective) has corroborated that when ultrasonography reveals a classic, or “almost certainly benign” finding, patients can be reassured that the lesion is benign, thereby avoiding extensive further workup. When a lesion is “nonclassic” in appearance and without any blood flow, further imaging with follow-up magnetic resonance imaging or repeat ultrasound could be considered. In women with a nonclassic lesion with blood flow, particularly in older women, referral to a gynecologic oncologic surgeon will help ensure expeditious treatment of possible ovarian cancer.

- Boll D, Geomini PM, Brölmann HA. The pre-operative assessment of the adnexal mass: the accuracy of clinical estimates versus clinical prediction rules. BJOG. 2003;110:519-523.

- Glanc P, Benacerraf B, Bourne T, et al. First International Consensus Report on adnexal masses: management recommendations. J Ultrasound Med. 2017;36:849-863. doi: 10.1002/jum.14197.

- Van Holsbeke C, Daemen A, Yazbek J, et al. Ultrasound experience substantially impacts on diagnostic performance and confidence when adnexal masses are classified using pattern recognition. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2010;69:160-168. doi: 10.1159/000265012.

- Shetty J, Reddy G, Pandey D. Role of sonographic grayscale pattern recognition in the diagnosis of adnexal masses. J Clin Diagn Res. 2017;11:QC12-QC15. doi: 10.7860 /JCDR/2017/28533.10614.

- Boll D, Geomini PM, Brölmann HA. The pre-operative assessment of the adnexal mass: the accuracy of clinical estimates versus clinical prediction rules. BJOG. 2003;110:519-523.

- Glanc P, Benacerraf B, Bourne T, et al. First International Consensus Report on adnexal masses: management recommendations. J Ultrasound Med. 2017;36:849-863. doi: 10.1002/jum.14197.

- Van Holsbeke C, Daemen A, Yazbek J, et al. Ultrasound experience substantially impacts on diagnostic performance and confidence when adnexal masses are classified using pattern recognition. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2010;69:160-168. doi: 10.1159/000265012.

- Shetty J, Reddy G, Pandey D. Role of sonographic grayscale pattern recognition in the diagnosis of adnexal masses. J Clin Diagn Res. 2017;11:QC12-QC15. doi: 10.7860 /JCDR/2017/28533.10614.

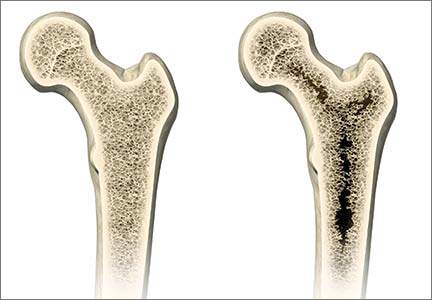

2015 Update on osteoporosis

More than 9 million American women are estimated to have osteoporosis, making it the most common bone disease and an especially prevalent health problem in postmenopausal women.1

Osteoporosis causes 2 million fractures every year, leading to major medical consequences for patients.2 These fractures are associated with significant morbidity and mortality, often requiring the extended use of long-term care facilities and causing severe disability.

With a rapidly increasing elderly population, the cost of care for osteoporosis is estimated to rise to $25.3 billion by 2025.3 The medical and financial impacts of osteoporosis underscore the need for timely screening and diagnosis and the implementation of effective prevention and treatment strategies. As women’s health care providers, we are the first line of screening and diagnosis and implementation of effective treatment strategies.

In this “Update on Osteoporosis,” I discuss:

- 2 studies that explore the use of zoledronic acid or denosumab in women with breast cancer undergoing adjuvant therapy with an aromatase inhibitor

- a report of a task force of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research on the long-term use of bisphosphonate therapy

- a look at the trabecular bone score as a tool to characterize bone strength and overall fracture risk

- the relationship of sarcopenia and body composition with osteoporosis.

- Wright NC, Looker AC, Saag KG, et al. The recent prevalence of osteoporosis and low bone mass in the United States based on bone mineral density at the femoral neck or lumbar spine. J Bone Miner Res. 2014;29(11):2520–2526.

- Management of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women: 2010 position statement of the North American Menopause Society. Menopause. 2010;17(1):25–54.

- Burge R, Dawson-Hughes B, Solomon DH, Wong JB, King AB, Tosterson A. Incidence and economic burden of osteoporosis-related fractures in the United States. 2007;22(3):465–475.

- Goss PE, Ingle JN, Martino S, et al. A randomized trial of letrozole in postmenopausal women after five years of tamoxifen therapy for early-stage breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2003;349(19):1793–1802.

- Coombes RC, Hall E, Gibson LJ, et al. A randomized trial of exemestane after two to three years of tamoxifen therapy in postmenopausal women with primary breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;350(11):1081–1092.

- Johnell O, Kanis JA. An estimate of the worldwide prevalence and disability associated with osteoporotic fractures. Osteoporos Int. 2006;17(12):1726–1733.

- Eisman JA, Bogoch ER, Dell R, et al; ASBMR Task Force on secondary fracture prevention. Making the first fracture the last fracture: ASBMR task force report on secondary fracture prevention. J Bone Miner Res. 2012;27(10):2039–2046.

- Adler RA, Fuleihan GE, Bauer DC, Camacho PM, Clarke BL, Clines GA. Managing osteoporosis in patients on long-term bisphosphonate treatment: Report of a task force on the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research [published online ahead of print September 9, 2015]. J Bone Miner Res. doi:10.1002/jbmr.2708.

- Black DM, Schwartz AV, Ensrud KE, et al; FLEX Research Group. Effects of continuing or stopping alendronate after five years of treatment. The Fracture Intervention Trial Long-Term Extension (FLEX): a randomized trial. JAMA. 2006;296(24):2927–2938.

- Mellström DD, Sörensen OH, Goemaere S, Roux C, Johnson TD, Chines AA. Seven years of treatment with risedronate in women with postmenopausal osteoporosis. Calcif Tissue Int. 2004;75(6):462–468.

- Black DM, Reid IR, Boonen S, et al. The effect of three versus six years of zoledronic acid treatment of osteoporosis: a randomized extension to the HORIZON-Pivotal Fracture Trial (PFT). J Bone Miner Res. 2012;7(2):243–254.

- Von Haehling S, Morley JE, Anker SD. An overview of sarcopenia: facts and numbers on prevalence and clinical impact. J Cachex Sarcopenia Muscle. 2010;1(2):129–133.

- Coin A, Perissinotto E, Enzi G, et al. Predictors of low bone mineral density in the elderly: the role of dietary intake, nutritional status and sarcopenia. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2008;62(6):802–809.

- Taaffe DR, Cauley JA, Danielson M, et al. Race and sex effects on the association between muscle strength, soft tissue, and bone mineral density in healthy elders: the Health, Aging, and Body Composition Study. J Bone Miner Res. 2001;16(7):1343–1352.

- Fielding RA, Vellas B, Evans WJ, et al. Sarcopenia: an undiagnosed condition in older adults. Current consensus definition: prevalence, etiology, and consequences. International Working Group on Sarcopenia. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2011;12(4):249–256.

- Kanis JA, McCloskey EV, Johansson H, Oden A, Melton LJ 3rd, Khaltaev N. A reference standard for the description of osteoporosis. Bone. 2008;42(3):467–475.

- Cheng Q, Zhu X, Zhang X, et al. A cross-sectional study of loss of muscle mass corresponding to sarcopenia in healthy Chinese men and women: reference values, prevalence, and association with bone mass. J Bone Miner Metab. 2013;32(1):78–88.

More than 9 million American women are estimated to have osteoporosis, making it the most common bone disease and an especially prevalent health problem in postmenopausal women.1

Osteoporosis causes 2 million fractures every year, leading to major medical consequences for patients.2 These fractures are associated with significant morbidity and mortality, often requiring the extended use of long-term care facilities and causing severe disability.

With a rapidly increasing elderly population, the cost of care for osteoporosis is estimated to rise to $25.3 billion by 2025.3 The medical and financial impacts of osteoporosis underscore the need for timely screening and diagnosis and the implementation of effective prevention and treatment strategies. As women’s health care providers, we are the first line of screening and diagnosis and implementation of effective treatment strategies.

In this “Update on Osteoporosis,” I discuss:

- 2 studies that explore the use of zoledronic acid or denosumab in women with breast cancer undergoing adjuvant therapy with an aromatase inhibitor

- a report of a task force of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research on the long-term use of bisphosphonate therapy

- a look at the trabecular bone score as a tool to characterize bone strength and overall fracture risk

- the relationship of sarcopenia and body composition with osteoporosis.

More than 9 million American women are estimated to have osteoporosis, making it the most common bone disease and an especially prevalent health problem in postmenopausal women.1

Osteoporosis causes 2 million fractures every year, leading to major medical consequences for patients.2 These fractures are associated with significant morbidity and mortality, often requiring the extended use of long-term care facilities and causing severe disability.

With a rapidly increasing elderly population, the cost of care for osteoporosis is estimated to rise to $25.3 billion by 2025.3 The medical and financial impacts of osteoporosis underscore the need for timely screening and diagnosis and the implementation of effective prevention and treatment strategies. As women’s health care providers, we are the first line of screening and diagnosis and implementation of effective treatment strategies.

In this “Update on Osteoporosis,” I discuss:

- 2 studies that explore the use of zoledronic acid or denosumab in women with breast cancer undergoing adjuvant therapy with an aromatase inhibitor

- a report of a task force of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research on the long-term use of bisphosphonate therapy

- a look at the trabecular bone score as a tool to characterize bone strength and overall fracture risk

- the relationship of sarcopenia and body composition with osteoporosis.

- Wright NC, Looker AC, Saag KG, et al. The recent prevalence of osteoporosis and low bone mass in the United States based on bone mineral density at the femoral neck or lumbar spine. J Bone Miner Res. 2014;29(11):2520–2526.

- Management of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women: 2010 position statement of the North American Menopause Society. Menopause. 2010;17(1):25–54.

- Burge R, Dawson-Hughes B, Solomon DH, Wong JB, King AB, Tosterson A. Incidence and economic burden of osteoporosis-related fractures in the United States. 2007;22(3):465–475.

- Goss PE, Ingle JN, Martino S, et al. A randomized trial of letrozole in postmenopausal women after five years of tamoxifen therapy for early-stage breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2003;349(19):1793–1802.

- Coombes RC, Hall E, Gibson LJ, et al. A randomized trial of exemestane after two to three years of tamoxifen therapy in postmenopausal women with primary breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;350(11):1081–1092.

- Johnell O, Kanis JA. An estimate of the worldwide prevalence and disability associated with osteoporotic fractures. Osteoporos Int. 2006;17(12):1726–1733.

- Eisman JA, Bogoch ER, Dell R, et al; ASBMR Task Force on secondary fracture prevention. Making the first fracture the last fracture: ASBMR task force report on secondary fracture prevention. J Bone Miner Res. 2012;27(10):2039–2046.

- Adler RA, Fuleihan GE, Bauer DC, Camacho PM, Clarke BL, Clines GA. Managing osteoporosis in patients on long-term bisphosphonate treatment: Report of a task force on the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research [published online ahead of print September 9, 2015]. J Bone Miner Res. doi:10.1002/jbmr.2708.

- Black DM, Schwartz AV, Ensrud KE, et al; FLEX Research Group. Effects of continuing or stopping alendronate after five years of treatment. The Fracture Intervention Trial Long-Term Extension (FLEX): a randomized trial. JAMA. 2006;296(24):2927–2938.

- Mellström DD, Sörensen OH, Goemaere S, Roux C, Johnson TD, Chines AA. Seven years of treatment with risedronate in women with postmenopausal osteoporosis. Calcif Tissue Int. 2004;75(6):462–468.

- Black DM, Reid IR, Boonen S, et al. The effect of three versus six years of zoledronic acid treatment of osteoporosis: a randomized extension to the HORIZON-Pivotal Fracture Trial (PFT). J Bone Miner Res. 2012;7(2):243–254.

- Von Haehling S, Morley JE, Anker SD. An overview of sarcopenia: facts and numbers on prevalence and clinical impact. J Cachex Sarcopenia Muscle. 2010;1(2):129–133.

- Coin A, Perissinotto E, Enzi G, et al. Predictors of low bone mineral density in the elderly: the role of dietary intake, nutritional status and sarcopenia. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2008;62(6):802–809.

- Taaffe DR, Cauley JA, Danielson M, et al. Race and sex effects on the association between muscle strength, soft tissue, and bone mineral density in healthy elders: the Health, Aging, and Body Composition Study. J Bone Miner Res. 2001;16(7):1343–1352.

- Fielding RA, Vellas B, Evans WJ, et al. Sarcopenia: an undiagnosed condition in older adults. Current consensus definition: prevalence, etiology, and consequences. International Working Group on Sarcopenia. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2011;12(4):249–256.

- Kanis JA, McCloskey EV, Johansson H, Oden A, Melton LJ 3rd, Khaltaev N. A reference standard for the description of osteoporosis. Bone. 2008;42(3):467–475.

- Cheng Q, Zhu X, Zhang X, et al. A cross-sectional study of loss of muscle mass corresponding to sarcopenia in healthy Chinese men and women: reference values, prevalence, and association with bone mass. J Bone Miner Metab. 2013;32(1):78–88.

- Wright NC, Looker AC, Saag KG, et al. The recent prevalence of osteoporosis and low bone mass in the United States based on bone mineral density at the femoral neck or lumbar spine. J Bone Miner Res. 2014;29(11):2520–2526.

- Management of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women: 2010 position statement of the North American Menopause Society. Menopause. 2010;17(1):25–54.

- Burge R, Dawson-Hughes B, Solomon DH, Wong JB, King AB, Tosterson A. Incidence and economic burden of osteoporosis-related fractures in the United States. 2007;22(3):465–475.

- Goss PE, Ingle JN, Martino S, et al. A randomized trial of letrozole in postmenopausal women after five years of tamoxifen therapy for early-stage breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2003;349(19):1793–1802.

- Coombes RC, Hall E, Gibson LJ, et al. A randomized trial of exemestane after two to three years of tamoxifen therapy in postmenopausal women with primary breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;350(11):1081–1092.

- Johnell O, Kanis JA. An estimate of the worldwide prevalence and disability associated with osteoporotic fractures. Osteoporos Int. 2006;17(12):1726–1733.

- Eisman JA, Bogoch ER, Dell R, et al; ASBMR Task Force on secondary fracture prevention. Making the first fracture the last fracture: ASBMR task force report on secondary fracture prevention. J Bone Miner Res. 2012;27(10):2039–2046.

- Adler RA, Fuleihan GE, Bauer DC, Camacho PM, Clarke BL, Clines GA. Managing osteoporosis in patients on long-term bisphosphonate treatment: Report of a task force on the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research [published online ahead of print September 9, 2015]. J Bone Miner Res. doi:10.1002/jbmr.2708.

- Black DM, Schwartz AV, Ensrud KE, et al; FLEX Research Group. Effects of continuing or stopping alendronate after five years of treatment. The Fracture Intervention Trial Long-Term Extension (FLEX): a randomized trial. JAMA. 2006;296(24):2927–2938.

- Mellström DD, Sörensen OH, Goemaere S, Roux C, Johnson TD, Chines AA. Seven years of treatment with risedronate in women with postmenopausal osteoporosis. Calcif Tissue Int. 2004;75(6):462–468.

- Black DM, Reid IR, Boonen S, et al. The effect of three versus six years of zoledronic acid treatment of osteoporosis: a randomized extension to the HORIZON-Pivotal Fracture Trial (PFT). J Bone Miner Res. 2012;7(2):243–254.

- Von Haehling S, Morley JE, Anker SD. An overview of sarcopenia: facts and numbers on prevalence and clinical impact. J Cachex Sarcopenia Muscle. 2010;1(2):129–133.

- Coin A, Perissinotto E, Enzi G, et al. Predictors of low bone mineral density in the elderly: the role of dietary intake, nutritional status and sarcopenia. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2008;62(6):802–809.

- Taaffe DR, Cauley JA, Danielson M, et al. Race and sex effects on the association between muscle strength, soft tissue, and bone mineral density in healthy elders: the Health, Aging, and Body Composition Study. J Bone Miner Res. 2001;16(7):1343–1352.

- Fielding RA, Vellas B, Evans WJ, et al. Sarcopenia: an undiagnosed condition in older adults. Current consensus definition: prevalence, etiology, and consequences. International Working Group on Sarcopenia. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2011;12(4):249–256.

- Kanis JA, McCloskey EV, Johansson H, Oden A, Melton LJ 3rd, Khaltaev N. A reference standard for the description of osteoporosis. Bone. 2008;42(3):467–475.

- Cheng Q, Zhu X, Zhang X, et al. A cross-sectional study of loss of muscle mass corresponding to sarcopenia in healthy Chinese men and women: reference values, prevalence, and association with bone mass. J Bone Miner Metab. 2013;32(1):78–88.

In this Article

- Optimal duration of bisphosphonate therapy?

- How a new bone score may help us refine fracture risk prediction

- Is sarcopenia an important piece of the bone health equation?