User login

Improving Patient Safety and Quality of Care

Patient safety and improved quality of care have become priority issues in the American healthcare system. The potential for medical errors was highlighted in 1999 when the Quality of Health Care in America Committee of the Institute of Medicine (IOM) published its first report, To Err is Human: Building a Safer Health System. The committee estimated that between 44,000 and 98,000 people die annually from inpatient medical errors. The eighth leading cause of death in this country, preventable medical errors, cost the U.S. approximately $17 billion annually in direct and indirect costs (IOM). These alarming statistics in the IOM report ignited the patient safety movement (I).

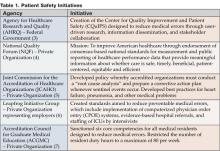

The IOM report made a series of recommendations that included the creation of a center for patient safety, the development of a national public reporting system, the establishment of oversight agencies, and the incorporation of safety principles into monitoring systems. Public and private agencies have responded with a series of initiatives that address these recommendations (See Table 1).

One healthcare expert describes three reasons as to why the potential for medical errors has increased. First, technology has created a sophisticated array of test, x-rays, laboratory procedures, and diagnostic tools. Second, pharmaceutical research has introduced thousands of new medications to the marketplace. Finally, specialization has led to experts, both physician and non-physician, in a wide range of body systems, diseases, settings, procedures, and therapies. Hospital medicine represents a new type of medical specialty that has the potential to address this increased complexity and sophistication and to improve patient care in the hospital inpatient environment (2).

Hospitalists as Team Coordinators

To achieve maximum positive outcomes in the complex inpatient environment, a qualified coordinator must educate others and facilitate activity revolving around patient care. Hospitalists as inpatient experts possess the necessary qualifications to integrate hospital systems and maximize efforts to enhance patient safety by monitoring medication distribution, chairing pharmaceuticals and therapeutics (P&T) committees, overseeing computerized physician order entry (CPOE), directing quality/performance improvement projects, and collaborating with discharge planning and case management.

Lakshmi Halasyamani, MD, is vice chair of the department of Internal Medicine at St. Joseph Mercy Hospital in Michigan and chairperson of the Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM) Hospital Quality and Patient Safety Committee. She says, Hospitalists have a ‘lens of understanding the systems under which they care for patients.’ They take care of patients in the hospital every single day so they can examine the processes with which they work. Hospitalists have an ideal perspective from which to reform ineffective systems.”

In spite of all the guidelines established by federal agencies and expert groups, Dr. Halasyamani points out that implementation barriers exist that prevent well-intentioned protocols and best practices from being carried out. Part of the challenge is the performance of a critical piece of the infrastructure—the multidisciplinary team. The very nature of healthcare demands an inherent need to coordinate and communicate. “Treating the patient is not the responsibility of one single individual,” says Halasyamani. “This is a team effort. The hospitalist recognizes that he is part of that team.” By elevating the ideals of teamwork, hospitalists can deliver to the patients the essential care that patients need, both while in the hospital and after they are discharged. In managing hospital inpatients, physicians must cope with high intensity of illness, pressures to reduce length of stay (LOS), and the coordination of handoffs among many specialists. According to Halasyamani, this can be a “recipe for disaster.”

Halasyamani acknowledges the vital role of protocols in reducing medical errors and improving quality of care. The training, education, and experience a hospitalist has acquired enables him to optimize communication and implement protocols, thus facilitating the practice of delivering safe and consistent care to all patients. In fact, with this smaller core group of inpatient physicians, the development and implementation of protocols can potentially be more effective because it targets a smaller group of physicians than the traditional inpatient model (8).

Kaveh C. Shojania, MD, is assistant professor of medicine at the University of Ottawa and co-author of Internal Bleeding: The Terrifying Truth Behind America's Epidemic Medical Mistakes. He points out that the current inpatient medical landscape involves a significant number of clinicians who practice at the hospital but not all their activity is centered there. “From a clinical perspective, no one has ownership,” he says. “On the other hand, hospitalists are based in a single hospital and have a vested interest in that particular hospital.” Typically generalists, hospitalists tend to interact with all specialists and therefore have a good sense of all interests.

Medical errors occur most often during transition times, from the ICU to the floor or from inpatient to outpatient status. There is the potential for a loss of clinical information during these transfers. According to Shojania, a significant portion of the hospitalist’s time is spent managing these transitions and overseeing patients as they are relocated from floor to floor and discharge to home, rehabilitation facility, or nursing home. He notes that the regulatory agencies have begun to acknowledge the importance of hospitalists. “The JCAHO (Joint Commission for the Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations) recognizes hospitalists as a resource because they are always in the hospital and have a vested interest,” he says (9).

Stakeholder Analysis

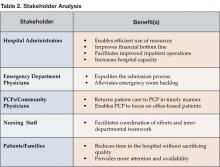

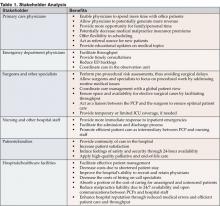

Patients stand to gain the most benefit from hospitalists insofar as safety and quality of care is concerned. Through the efforts and oversight of hospitalists, patients may experience reduced medical errors and lower mortality rates. For primary care physicians and hospitals, this lower rate of medical error means fewer medical malpractice cases, the potential for lower insurance premiums and, as a result, enhanced reputations. When hospitals are run more efficiently and provide a greater sense of trust and efficient management practices, society in general becomes the benefactor.

Clinical Trials

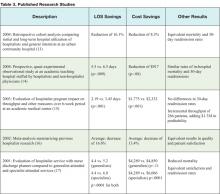

To date, few research studies measuring the impact of hospitalists on patient safety and quality of care have been conducted. Quality of care has been assessed largely through the surrogate markers of mortality and readmission rates. One study showed decreased in-hospital and 1-year mortality rates for hospitalist patients (10), and another indicated a decrease in 30-day readmission rates (11).

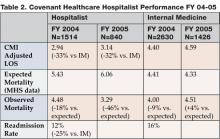

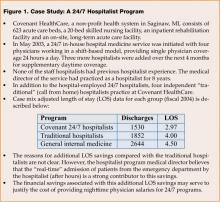

In addition, data from individual programs demonstrate positive findings. For example, Stacy Goldsholl, MD, medical director of the Covenant Healthcare hospital medicine program in Michigan, reports a 17% decrease in the expected mortality rate in the first year of the hospital medicine program. The information was drawn from the Michigan Hospital Association (MHA) databank and matched for severity and diagnosis (See Table 2). “This was significant when compared to the internal medicine comparison group with similar case mix index (CMI),” says Goldsholl. “In the first half of our second year, we have demonstrated a 46% decrease in expected mortality, while internal medicine had a 4% increase” (12).

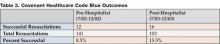

Additionally, Goldsholl reports that Covenant initiated a Code Blue and emergency consult service to improve patient outcome and experienced a marked increase in efficiency. Table 3 represents elementary data collected during the first 6 months pre- and post-initiation of the hospital medicine program at Covenant (12).

Conclusion

Patient safety and quality of care in the hospital require a team of dedicated people to effect change. Orchestrating the team effectively is the responsibility of an attending physician. With the numerous “handoffs” that take place during hospitalization, the potential for medical errors increases exponentially. Federal mandates requiring the conversion to electronic medical records, which includes basic health information as well as critical data regarding medications, procedures, and surgeries, further complicates efficient and safe patient management. According to Robert Wachter, “Those doctors with the best outcomes were those who tended to treat similar patients with similar problems using similar techniques.” By definition, the hospitalist is a “physician who focuses his practice on the care, coordination, and safety of hospitalized patients.” Who better to stand at the center of the issue of reduced medical errors, improved patient care, and enhanced quality of care than hospitalists (13)?

Dr. Pak can be contacted at mhp@medicine.wisc.edu.

References

- To Err is Human: Building a Safer Health System, Institute of Medicine, November 1999.

- Wachter R. The end of the beginning: patient safety five years after ‘To Err Is Human.’ Health Affairs. November 30, 2004.

- Mission Statement: Center for Quality Improvement and Patient Safety. February 2004. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, MD. www.ahrq.gov/about/cquips/cquipsmiss.htm.

- Safe Practices for Better Healthcare: a Consensus. The National Quality Forum, 2003.

- Joint Commission for Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (JCAHO), www.jcaho.org.

- Leapfrog Group, www.leapfroggroup.org.

- Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME), www.acgme.org.

- Halasyamani L. Telephone interview. February 7, 2005.

- Shojania KG. Assistant professor of medicine, University of Ottawa. Telephone interview. January 31, 2005.

- Auerbach AD, Wachter RM, Katz P. et al. Implementation of a voluntary hospitalist service at a community teaching hospital: improved clinical efficiency and patient outcomes. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137:859-65.

- Kulaga ME, Charney P, O’Mahoney SP, et al. The positive impact of initiation of hospitalist clinician educators. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19:293-301.

- Goldsholl S. Medical director. Covenant Healthcare hospital medicine program, Saginaw, Michigan, email interview. January 31, 2005.

- Wachter R, Shojania K. Internal bleeding: the truth behind America’s terrifying epidemic of medical mistakes. Rugged Land, LLC, 2004.

Patient safety and improved quality of care have become priority issues in the American healthcare system. The potential for medical errors was highlighted in 1999 when the Quality of Health Care in America Committee of the Institute of Medicine (IOM) published its first report, To Err is Human: Building a Safer Health System. The committee estimated that between 44,000 and 98,000 people die annually from inpatient medical errors. The eighth leading cause of death in this country, preventable medical errors, cost the U.S. approximately $17 billion annually in direct and indirect costs (IOM). These alarming statistics in the IOM report ignited the patient safety movement (I).

The IOM report made a series of recommendations that included the creation of a center for patient safety, the development of a national public reporting system, the establishment of oversight agencies, and the incorporation of safety principles into monitoring systems. Public and private agencies have responded with a series of initiatives that address these recommendations (See Table 1).

One healthcare expert describes three reasons as to why the potential for medical errors has increased. First, technology has created a sophisticated array of test, x-rays, laboratory procedures, and diagnostic tools. Second, pharmaceutical research has introduced thousands of new medications to the marketplace. Finally, specialization has led to experts, both physician and non-physician, in a wide range of body systems, diseases, settings, procedures, and therapies. Hospital medicine represents a new type of medical specialty that has the potential to address this increased complexity and sophistication and to improve patient care in the hospital inpatient environment (2).

Hospitalists as Team Coordinators

To achieve maximum positive outcomes in the complex inpatient environment, a qualified coordinator must educate others and facilitate activity revolving around patient care. Hospitalists as inpatient experts possess the necessary qualifications to integrate hospital systems and maximize efforts to enhance patient safety by monitoring medication distribution, chairing pharmaceuticals and therapeutics (P&T) committees, overseeing computerized physician order entry (CPOE), directing quality/performance improvement projects, and collaborating with discharge planning and case management.

Lakshmi Halasyamani, MD, is vice chair of the department of Internal Medicine at St. Joseph Mercy Hospital in Michigan and chairperson of the Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM) Hospital Quality and Patient Safety Committee. She says, Hospitalists have a ‘lens of understanding the systems under which they care for patients.’ They take care of patients in the hospital every single day so they can examine the processes with which they work. Hospitalists have an ideal perspective from which to reform ineffective systems.”

In spite of all the guidelines established by federal agencies and expert groups, Dr. Halasyamani points out that implementation barriers exist that prevent well-intentioned protocols and best practices from being carried out. Part of the challenge is the performance of a critical piece of the infrastructure—the multidisciplinary team. The very nature of healthcare demands an inherent need to coordinate and communicate. “Treating the patient is not the responsibility of one single individual,” says Halasyamani. “This is a team effort. The hospitalist recognizes that he is part of that team.” By elevating the ideals of teamwork, hospitalists can deliver to the patients the essential care that patients need, both while in the hospital and after they are discharged. In managing hospital inpatients, physicians must cope with high intensity of illness, pressures to reduce length of stay (LOS), and the coordination of handoffs among many specialists. According to Halasyamani, this can be a “recipe for disaster.”

Halasyamani acknowledges the vital role of protocols in reducing medical errors and improving quality of care. The training, education, and experience a hospitalist has acquired enables him to optimize communication and implement protocols, thus facilitating the practice of delivering safe and consistent care to all patients. In fact, with this smaller core group of inpatient physicians, the development and implementation of protocols can potentially be more effective because it targets a smaller group of physicians than the traditional inpatient model (8).

Kaveh C. Shojania, MD, is assistant professor of medicine at the University of Ottawa and co-author of Internal Bleeding: The Terrifying Truth Behind America's Epidemic Medical Mistakes. He points out that the current inpatient medical landscape involves a significant number of clinicians who practice at the hospital but not all their activity is centered there. “From a clinical perspective, no one has ownership,” he says. “On the other hand, hospitalists are based in a single hospital and have a vested interest in that particular hospital.” Typically generalists, hospitalists tend to interact with all specialists and therefore have a good sense of all interests.

Medical errors occur most often during transition times, from the ICU to the floor or from inpatient to outpatient status. There is the potential for a loss of clinical information during these transfers. According to Shojania, a significant portion of the hospitalist’s time is spent managing these transitions and overseeing patients as they are relocated from floor to floor and discharge to home, rehabilitation facility, or nursing home. He notes that the regulatory agencies have begun to acknowledge the importance of hospitalists. “The JCAHO (Joint Commission for the Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations) recognizes hospitalists as a resource because they are always in the hospital and have a vested interest,” he says (9).

Stakeholder Analysis

Patients stand to gain the most benefit from hospitalists insofar as safety and quality of care is concerned. Through the efforts and oversight of hospitalists, patients may experience reduced medical errors and lower mortality rates. For primary care physicians and hospitals, this lower rate of medical error means fewer medical malpractice cases, the potential for lower insurance premiums and, as a result, enhanced reputations. When hospitals are run more efficiently and provide a greater sense of trust and efficient management practices, society in general becomes the benefactor.

Clinical Trials

To date, few research studies measuring the impact of hospitalists on patient safety and quality of care have been conducted. Quality of care has been assessed largely through the surrogate markers of mortality and readmission rates. One study showed decreased in-hospital and 1-year mortality rates for hospitalist patients (10), and another indicated a decrease in 30-day readmission rates (11).

In addition, data from individual programs demonstrate positive findings. For example, Stacy Goldsholl, MD, medical director of the Covenant Healthcare hospital medicine program in Michigan, reports a 17% decrease in the expected mortality rate in the first year of the hospital medicine program. The information was drawn from the Michigan Hospital Association (MHA) databank and matched for severity and diagnosis (See Table 2). “This was significant when compared to the internal medicine comparison group with similar case mix index (CMI),” says Goldsholl. “In the first half of our second year, we have demonstrated a 46% decrease in expected mortality, while internal medicine had a 4% increase” (12).

Additionally, Goldsholl reports that Covenant initiated a Code Blue and emergency consult service to improve patient outcome and experienced a marked increase in efficiency. Table 3 represents elementary data collected during the first 6 months pre- and post-initiation of the hospital medicine program at Covenant (12).

Conclusion

Patient safety and quality of care in the hospital require a team of dedicated people to effect change. Orchestrating the team effectively is the responsibility of an attending physician. With the numerous “handoffs” that take place during hospitalization, the potential for medical errors increases exponentially. Federal mandates requiring the conversion to electronic medical records, which includes basic health information as well as critical data regarding medications, procedures, and surgeries, further complicates efficient and safe patient management. According to Robert Wachter, “Those doctors with the best outcomes were those who tended to treat similar patients with similar problems using similar techniques.” By definition, the hospitalist is a “physician who focuses his practice on the care, coordination, and safety of hospitalized patients.” Who better to stand at the center of the issue of reduced medical errors, improved patient care, and enhanced quality of care than hospitalists (13)?

Dr. Pak can be contacted at mhp@medicine.wisc.edu.

References

- To Err is Human: Building a Safer Health System, Institute of Medicine, November 1999.

- Wachter R. The end of the beginning: patient safety five years after ‘To Err Is Human.’ Health Affairs. November 30, 2004.

- Mission Statement: Center for Quality Improvement and Patient Safety. February 2004. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, MD. www.ahrq.gov/about/cquips/cquipsmiss.htm.

- Safe Practices for Better Healthcare: a Consensus. The National Quality Forum, 2003.

- Joint Commission for Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (JCAHO), www.jcaho.org.

- Leapfrog Group, www.leapfroggroup.org.

- Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME), www.acgme.org.

- Halasyamani L. Telephone interview. February 7, 2005.

- Shojania KG. Assistant professor of medicine, University of Ottawa. Telephone interview. January 31, 2005.

- Auerbach AD, Wachter RM, Katz P. et al. Implementation of a voluntary hospitalist service at a community teaching hospital: improved clinical efficiency and patient outcomes. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137:859-65.

- Kulaga ME, Charney P, O’Mahoney SP, et al. The positive impact of initiation of hospitalist clinician educators. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19:293-301.

- Goldsholl S. Medical director. Covenant Healthcare hospital medicine program, Saginaw, Michigan, email interview. January 31, 2005.

- Wachter R, Shojania K. Internal bleeding: the truth behind America’s terrifying epidemic of medical mistakes. Rugged Land, LLC, 2004.

Patient safety and improved quality of care have become priority issues in the American healthcare system. The potential for medical errors was highlighted in 1999 when the Quality of Health Care in America Committee of the Institute of Medicine (IOM) published its first report, To Err is Human: Building a Safer Health System. The committee estimated that between 44,000 and 98,000 people die annually from inpatient medical errors. The eighth leading cause of death in this country, preventable medical errors, cost the U.S. approximately $17 billion annually in direct and indirect costs (IOM). These alarming statistics in the IOM report ignited the patient safety movement (I).

The IOM report made a series of recommendations that included the creation of a center for patient safety, the development of a national public reporting system, the establishment of oversight agencies, and the incorporation of safety principles into monitoring systems. Public and private agencies have responded with a series of initiatives that address these recommendations (See Table 1).

One healthcare expert describes three reasons as to why the potential for medical errors has increased. First, technology has created a sophisticated array of test, x-rays, laboratory procedures, and diagnostic tools. Second, pharmaceutical research has introduced thousands of new medications to the marketplace. Finally, specialization has led to experts, both physician and non-physician, in a wide range of body systems, diseases, settings, procedures, and therapies. Hospital medicine represents a new type of medical specialty that has the potential to address this increased complexity and sophistication and to improve patient care in the hospital inpatient environment (2).

Hospitalists as Team Coordinators

To achieve maximum positive outcomes in the complex inpatient environment, a qualified coordinator must educate others and facilitate activity revolving around patient care. Hospitalists as inpatient experts possess the necessary qualifications to integrate hospital systems and maximize efforts to enhance patient safety by monitoring medication distribution, chairing pharmaceuticals and therapeutics (P&T) committees, overseeing computerized physician order entry (CPOE), directing quality/performance improvement projects, and collaborating with discharge planning and case management.

Lakshmi Halasyamani, MD, is vice chair of the department of Internal Medicine at St. Joseph Mercy Hospital in Michigan and chairperson of the Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM) Hospital Quality and Patient Safety Committee. She says, Hospitalists have a ‘lens of understanding the systems under which they care for patients.’ They take care of patients in the hospital every single day so they can examine the processes with which they work. Hospitalists have an ideal perspective from which to reform ineffective systems.”

In spite of all the guidelines established by federal agencies and expert groups, Dr. Halasyamani points out that implementation barriers exist that prevent well-intentioned protocols and best practices from being carried out. Part of the challenge is the performance of a critical piece of the infrastructure—the multidisciplinary team. The very nature of healthcare demands an inherent need to coordinate and communicate. “Treating the patient is not the responsibility of one single individual,” says Halasyamani. “This is a team effort. The hospitalist recognizes that he is part of that team.” By elevating the ideals of teamwork, hospitalists can deliver to the patients the essential care that patients need, both while in the hospital and after they are discharged. In managing hospital inpatients, physicians must cope with high intensity of illness, pressures to reduce length of stay (LOS), and the coordination of handoffs among many specialists. According to Halasyamani, this can be a “recipe for disaster.”

Halasyamani acknowledges the vital role of protocols in reducing medical errors and improving quality of care. The training, education, and experience a hospitalist has acquired enables him to optimize communication and implement protocols, thus facilitating the practice of delivering safe and consistent care to all patients. In fact, with this smaller core group of inpatient physicians, the development and implementation of protocols can potentially be more effective because it targets a smaller group of physicians than the traditional inpatient model (8).

Kaveh C. Shojania, MD, is assistant professor of medicine at the University of Ottawa and co-author of Internal Bleeding: The Terrifying Truth Behind America's Epidemic Medical Mistakes. He points out that the current inpatient medical landscape involves a significant number of clinicians who practice at the hospital but not all their activity is centered there. “From a clinical perspective, no one has ownership,” he says. “On the other hand, hospitalists are based in a single hospital and have a vested interest in that particular hospital.” Typically generalists, hospitalists tend to interact with all specialists and therefore have a good sense of all interests.

Medical errors occur most often during transition times, from the ICU to the floor or from inpatient to outpatient status. There is the potential for a loss of clinical information during these transfers. According to Shojania, a significant portion of the hospitalist’s time is spent managing these transitions and overseeing patients as they are relocated from floor to floor and discharge to home, rehabilitation facility, or nursing home. He notes that the regulatory agencies have begun to acknowledge the importance of hospitalists. “The JCAHO (Joint Commission for the Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations) recognizes hospitalists as a resource because they are always in the hospital and have a vested interest,” he says (9).

Stakeholder Analysis

Patients stand to gain the most benefit from hospitalists insofar as safety and quality of care is concerned. Through the efforts and oversight of hospitalists, patients may experience reduced medical errors and lower mortality rates. For primary care physicians and hospitals, this lower rate of medical error means fewer medical malpractice cases, the potential for lower insurance premiums and, as a result, enhanced reputations. When hospitals are run more efficiently and provide a greater sense of trust and efficient management practices, society in general becomes the benefactor.

Clinical Trials

To date, few research studies measuring the impact of hospitalists on patient safety and quality of care have been conducted. Quality of care has been assessed largely through the surrogate markers of mortality and readmission rates. One study showed decreased in-hospital and 1-year mortality rates for hospitalist patients (10), and another indicated a decrease in 30-day readmission rates (11).

In addition, data from individual programs demonstrate positive findings. For example, Stacy Goldsholl, MD, medical director of the Covenant Healthcare hospital medicine program in Michigan, reports a 17% decrease in the expected mortality rate in the first year of the hospital medicine program. The information was drawn from the Michigan Hospital Association (MHA) databank and matched for severity and diagnosis (See Table 2). “This was significant when compared to the internal medicine comparison group with similar case mix index (CMI),” says Goldsholl. “In the first half of our second year, we have demonstrated a 46% decrease in expected mortality, while internal medicine had a 4% increase” (12).

Additionally, Goldsholl reports that Covenant initiated a Code Blue and emergency consult service to improve patient outcome and experienced a marked increase in efficiency. Table 3 represents elementary data collected during the first 6 months pre- and post-initiation of the hospital medicine program at Covenant (12).

Conclusion

Patient safety and quality of care in the hospital require a team of dedicated people to effect change. Orchestrating the team effectively is the responsibility of an attending physician. With the numerous “handoffs” that take place during hospitalization, the potential for medical errors increases exponentially. Federal mandates requiring the conversion to electronic medical records, which includes basic health information as well as critical data regarding medications, procedures, and surgeries, further complicates efficient and safe patient management. According to Robert Wachter, “Those doctors with the best outcomes were those who tended to treat similar patients with similar problems using similar techniques.” By definition, the hospitalist is a “physician who focuses his practice on the care, coordination, and safety of hospitalized patients.” Who better to stand at the center of the issue of reduced medical errors, improved patient care, and enhanced quality of care than hospitalists (13)?

Dr. Pak can be contacted at mhp@medicine.wisc.edu.

References

- To Err is Human: Building a Safer Health System, Institute of Medicine, November 1999.

- Wachter R. The end of the beginning: patient safety five years after ‘To Err Is Human.’ Health Affairs. November 30, 2004.

- Mission Statement: Center for Quality Improvement and Patient Safety. February 2004. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, MD. www.ahrq.gov/about/cquips/cquipsmiss.htm.

- Safe Practices for Better Healthcare: a Consensus. The National Quality Forum, 2003.

- Joint Commission for Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (JCAHO), www.jcaho.org.

- Leapfrog Group, www.leapfroggroup.org.

- Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME), www.acgme.org.

- Halasyamani L. Telephone interview. February 7, 2005.

- Shojania KG. Assistant professor of medicine, University of Ottawa. Telephone interview. January 31, 2005.

- Auerbach AD, Wachter RM, Katz P. et al. Implementation of a voluntary hospitalist service at a community teaching hospital: improved clinical efficiency and patient outcomes. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137:859-65.

- Kulaga ME, Charney P, O’Mahoney SP, et al. The positive impact of initiation of hospitalist clinician educators. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19:293-301.

- Goldsholl S. Medical director. Covenant Healthcare hospital medicine program, Saginaw, Michigan, email interview. January 31, 2005.

- Wachter R, Shojania K. Internal bleeding: the truth behind America’s terrifying epidemic of medical mistakes. Rugged Land, LLC, 2004.

Maximizing Throughput and Improving Patient Flow

According to data from the American Hospital Association (1), in 1985, the United States had 5732 operational community hospitals; by 2002, the latest year for which figures are available, the number had decreased to 4927, a loss of approximately 14% (1). In that same timeframe, these hospitals lost approximately 18% of their beds, dropping from just over 1 million to 820,653 beds. This reduction in bed capacity has been accompanied by hospital cost-cutting efforts, staff downsizing, and elimination of services. Many explanations for these trends have been suggested, including changes in Medicare reimbursement and the growth of managed care organizations (MCOs).

However, as the current baby boom generation ages, rising inpatient demands are presenting hospitals with significant challenges. According to a 2001 report from Solucient (2), who maintains the nation’s largest health care database, the senior population—individuals age 65 and older—are projected to experience an 85% growth rate over the next two decades. Since this age group utilizes inpatient services 4.5 times more than younger populations, the number of admissions and beds to accommodate those cases will soar. By the year 2027, hospitals can anticipate a 46% rise in demand for acute inpatient beds as admissions escalate by approximately 13 million cases. Currently, the nation’s healthcare facilities admit 31 million cases; this number will jump to more than 44 million, representing a 41% growth from present admissions figures. For hospitals that maintain an 80% census rate, an additional 238,000 beds will be needed to meet demands (1).

Adding to this increase in demand and pressure on bed capacity, hospitals must address the requirements of the Emergency Medical Treatment and Active Labor Act (EMTALA) passed by the US Congress in 1986 as part of the Consolidated Omnibus Reconciliation Act (COBRA). The law’s initial intent was to ensure patient access to emergency medical care and to prevent the practice of patient dumping, in which uninsured patients were transferred, solely for financial reasons, from private to public hospitals without consideration of their medical condition or stability for the transfer (3). EMTALA mandates that hospitals rank the severity of patients. Thus, tertiary referral centers are required to admit the sickest patients first. This directive presents a significant challenge to many healthcare facilities. High census rates prohibit the admission of elective surgical cases, which, although profitable, are considered second tier. Routine medical cases or complicated emergency surgical cases have the potential to adversely affect the institution’s financial performance.

In addition to the challenge of increased bed demands and EMTALA, hospitals also cite an increasingly smaller number of on-site community physicians. Longstanding trends from inpatient to outpatient care have prompted many community physicians to concentrate their efforts on serving the needs of office-based patients, limiting their accessibility to hospital cases.

To address these pressures, hospitals must execute innovative strategies that deliver efficient throughput and enhance revenue, while still preserving high-quality services. Since 1996, hospital medicine programs have demonstrated a positive impact on the healthcare facility’s ability to increase overall productivity and profitability and still maintain high quality Patients today present to the doctor sicker than in the past and require more careful and frequent outpatient care. Since hospitalists operate solely on an inpatient basis, their availability to efficiently admit and manage hospitalized patients enables delivery of quality care that expedites appropriate treatment and shortens length of stay.

Two Roles of the Hospitalist

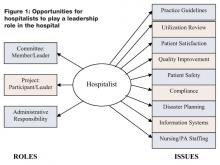

According to the Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM), “Hospitalists are physicians whose primary professional focus is the general medical care of hospitalized patients. Their activities include patient care, teaching, research, and leadership related to hospital medicine.” Coined by Drs. Robert Wachter and Lee Goldman in 1996 (4), the term implies an additional point of emphasis. Part of a new paradigm in clinical care, the hospitalist enhances the processes of care surrounding patients and adopts an attitude of accountability for that care. In practice, hospitalists play two key roles.

Primarily, the hospitalist is a practicing clinician — managing throughput on a case-by-case, patient-by-patient basis. In addition, a hospitalist performs a non-clinical role as an “inpatient expert,” taking the lead in creating system changes and communicating those changes to other hospital personnel as well as to community physicians. As an inpatient expert, hospitalists are often asked to lead organization-wide throughput initiatives to identify and implement strategies to facilitate patient flow and efficiency. As dedicated members of multi-disciplinary in-house teams, the hospitalist is in a prime position to foster change and improve systems.

Throughput as Continuum of Care

As suggested by Heffner (5), the process of admission, hospitalization, and discharge resembles a “bell-shaped curve.” To achieve effective throughput, hospitals must expedite patient care and also maintain careful oversight throughout a patient’s entire hospital stay. The hospitalist, as an integral part of a multidisciplinary team, coordinates care to promote a positive outcome and shorten length of stay. Drawing on strong leadership qualities, as well as on intimate knowledge of hospital procedures, layout design and infrastructure, and available community resources, the hospitalist plays a pivotal role in creating efficient throughput from admission to discharge.

Emergency Department

At the front end of the bell-shaped curve, the hospitalist may be engaged by emergency department (ED) physicians to assist in ensuring smooth patient flow and, more important, identifies the “intensity of service” needed. Through the use of clinical criteria, such as lnterQual, the hospitalist, together with the ED physician, may be asked to quantitatively rate the patient’s illness for degree of severity.

Timely patient evaluation helps prevent a backlog of ED cases and enables more patients to be seen. Immediate attention to and initiation of appropriate therapy guarantees a better outcome while minimizing the potential risk for complications, which could possibly lead to longer inpatient stays.

Inpatient Unit

Once a patient has been admitted to an inpatient unit, the hospitalist, together with a multidisciplinary team, facilitates care and determines the inpatient services that will optimize patient recovery through strong interdepartmental communications. Working together with admissions, medical records, nursing, laboratory and diagnostic services, information technology and other pertinent departments, the hospitalist maintains a pulse on all activity surrounding the patient and his care.

Judicious inpatient consultations and treatment decisions result in timely changes in therapy, potentially reducing the length of stay. The frequency with which the hospitalist sees the patient allows him to monitor any changes in condition and reduce possible decompensation, a practice known as vertical continuity (6). Such careful attention may reduce inpatient length of stay significantly. When aggressive management is mandated, the presence of the hospitalist enables initiation of effective therapy and results in quicker discharge and a reduction in potential readmission (7).

Surgery

The surgeon and hospitalist are ideally suited to work together in managing a surgical patient. The hospitalist focuses on the peri-operative management of medical issues and risk reduction, which allows the surgeon to concentrate more on surgical indications and the surgery itself. The hospitalist’s role in the management of a surgical patient enables vertical continuity when the surgeon may be occupied in the operating room with another patient as documented by Huddleston’s Hospitalist Orthopedic Team (HOT) approach (8).

Intensive Care Unit (ICU)

In many hospitals, particularly those that do not have intensivists, hospitalists are able to provide quality care to patients. Even in hospitals where intensivists manage ICU patients, hospitalists work together with the intensivist to ensure smoother transition into and out of the unit.

Discharge

Timing is a critical issue with regard to discharge. Since the hospitalist operates solely in-house and in collaboration with a multidisciplinary team, he is able to round early in the day to discharge patients by mid- or late-morning, freeing a bed for a new patient. In some cases, the hospitalist, in anticipation of early discharge, may begin pre-planning the day prior to discharge, which further expedites the process. Early discharge applies to the ICU, step-down areas and general inpatient care areas, as well as to full discharge from the healthcare facility. Moving a patient from one of these areas enables other patients to fill those empty beds thus optimizing throughput.

Having managed the patient throughout his hospital stay, the hospitalist — again working together with a multidisciplinary team —can facilitate arrangements to send the patient home or to a rehabilitation or skilled nursing facility or alternative housing situation upon discharge, as well as coordinating post-discharge care, whether it be arranging for a visiting nursing or social services or communicating with the primary care physician regarding follow-up appointments. If additional outpatient care is prescribed, the hospitalist will work with the discharge planning staff to contact various community agencies to arrange services best suited to the patient’s needs. Efficient discharge makes possible the admission of other, more critically ill patients, potentially enhancing the hospital’s revenue stream.

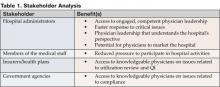

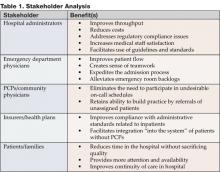

Stakeholder Analysis

Five specific stakeholders need to be examined to document the value-added by hospitalists. Anecdotal evidence, as well as documented studies, has demonstrated numerous returns—physical, social, psychological and financial—to stakeholders involved in the hospital process. With regard to throughput, the hospitalist provides benefits to each of the stakeholders listed in Table 1.

Study Results

A dozen studies have been conducted that document the impact of hospital medicine programs on cost and clinical outcomes. Of these trials, nine found a significant decrease in the average length of stay (15%) as well as reductions in cost (9). Two other studies, one from an academic medical center and the other from a community teaching hospital, demonstrate similar reductions during a 2-year follow-up period. At the Western Penn Hospital, a 54% reduction in readmissions was reported with a 12% decrease in hospital costs, while the average LOS was 17% shorter. Additionally, an unpublished study from the University of California, San Francisco Medical Center revealed a consistent 10-15% decline in cost and length of stay between hospitalists and non-hospitalist teaching faculty. More important, those differences remained stable through 6 years of follow-up. In general, hospitals with hospitalist programs realized a 5-39% decrease in costs and a shortened average LOS of 7-25% (6).

According to Robert M. Wachter, author of the 2002 study, “If the average U.S. hospitalist cares for 600 inpatients each year and generates a 10% savings over the average medical inpatient cost of $8,000, the nation’s 4500 hospitalists save approximately $2.2 billion per year while potentially improving quality” (6).

In a study conducted by Douglas Gregory, Walter Baigelman, and Ira B. Wilson, hospitalists at Tufts-New England Medical Center in Boston, MA were found to substantially improve throughput with high baseline occupancy levels. Compared with a control group, the hospitalist group reduced LOS from 3.45 days to 2.19 days (p<.001). Additionally, the total cost of hospital admission decreased from $2,332 to $1,775 (p<.001) when hospitalists were involved. According to the study authors, improved throughput generated an incremental 266 patients per year with a related incremental hospital profitability of $1.3 million with the use of hospitalists (7).

Conclusion

As hospital administrators attempt to address the issue of expeditiously admitting, treating and discharging patients in these days of restricted budgets and increased demand, hospitalist programs are poised as an invaluable factor in the throughput process.

Dr. Cawley can be contacted at pcawley@ushosp.com.

References

- Hospital Statistics: the comprehensive reference source for analysis and comparison of hospital trends. Published annually by Health Forum, an affiliate of the American Hospital Association.

- National and local impact of long-term demographic change on inpatient acute care. 2001. Solucient, LLC.

- Zibulewsky J. The Emergency Medical Treatment and Active Labor Act (EMTALA): what it is and what it means for physicians. Baylor University Medical Center (BUMC) Proceedings. 2001;14:339-46.

- Wachter RM, Goldman L. The emerging role of “hospitalists” in the American health care system. N Eng J Med. 1996;335:514-7.

- Heffner JE. Executive medical director, Medical University of South Carolina (MUSC). Personal interview. June 24, 2004.

- Whitcomb WF. Director, Mercy Inpatient Medicine Service, Mercy Medical Center, Springfield, MA.

- Gregory D, Baigelman W, Wilson IB. Hospital economics of the hospitalist. Health Serv Res. 2003;38:905-18.

- Huddleston JM, Long KH, Naessens JM, et al. Medical and surgical co-management after elective hip and knee arthroplasty: a randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141:28-38.

- Wachter RM. The evolution of the hospitalist model in the United States. Med Clin North Am. 2002;86:687-706.

According to data from the American Hospital Association (1), in 1985, the United States had 5732 operational community hospitals; by 2002, the latest year for which figures are available, the number had decreased to 4927, a loss of approximately 14% (1). In that same timeframe, these hospitals lost approximately 18% of their beds, dropping from just over 1 million to 820,653 beds. This reduction in bed capacity has been accompanied by hospital cost-cutting efforts, staff downsizing, and elimination of services. Many explanations for these trends have been suggested, including changes in Medicare reimbursement and the growth of managed care organizations (MCOs).

However, as the current baby boom generation ages, rising inpatient demands are presenting hospitals with significant challenges. According to a 2001 report from Solucient (2), who maintains the nation’s largest health care database, the senior population—individuals age 65 and older—are projected to experience an 85% growth rate over the next two decades. Since this age group utilizes inpatient services 4.5 times more than younger populations, the number of admissions and beds to accommodate those cases will soar. By the year 2027, hospitals can anticipate a 46% rise in demand for acute inpatient beds as admissions escalate by approximately 13 million cases. Currently, the nation’s healthcare facilities admit 31 million cases; this number will jump to more than 44 million, representing a 41% growth from present admissions figures. For hospitals that maintain an 80% census rate, an additional 238,000 beds will be needed to meet demands (1).

Adding to this increase in demand and pressure on bed capacity, hospitals must address the requirements of the Emergency Medical Treatment and Active Labor Act (EMTALA) passed by the US Congress in 1986 as part of the Consolidated Omnibus Reconciliation Act (COBRA). The law’s initial intent was to ensure patient access to emergency medical care and to prevent the practice of patient dumping, in which uninsured patients were transferred, solely for financial reasons, from private to public hospitals without consideration of their medical condition or stability for the transfer (3). EMTALA mandates that hospitals rank the severity of patients. Thus, tertiary referral centers are required to admit the sickest patients first. This directive presents a significant challenge to many healthcare facilities. High census rates prohibit the admission of elective surgical cases, which, although profitable, are considered second tier. Routine medical cases or complicated emergency surgical cases have the potential to adversely affect the institution’s financial performance.

In addition to the challenge of increased bed demands and EMTALA, hospitals also cite an increasingly smaller number of on-site community physicians. Longstanding trends from inpatient to outpatient care have prompted many community physicians to concentrate their efforts on serving the needs of office-based patients, limiting their accessibility to hospital cases.

To address these pressures, hospitals must execute innovative strategies that deliver efficient throughput and enhance revenue, while still preserving high-quality services. Since 1996, hospital medicine programs have demonstrated a positive impact on the healthcare facility’s ability to increase overall productivity and profitability and still maintain high quality Patients today present to the doctor sicker than in the past and require more careful and frequent outpatient care. Since hospitalists operate solely on an inpatient basis, their availability to efficiently admit and manage hospitalized patients enables delivery of quality care that expedites appropriate treatment and shortens length of stay.

Two Roles of the Hospitalist

According to the Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM), “Hospitalists are physicians whose primary professional focus is the general medical care of hospitalized patients. Their activities include patient care, teaching, research, and leadership related to hospital medicine.” Coined by Drs. Robert Wachter and Lee Goldman in 1996 (4), the term implies an additional point of emphasis. Part of a new paradigm in clinical care, the hospitalist enhances the processes of care surrounding patients and adopts an attitude of accountability for that care. In practice, hospitalists play two key roles.

Primarily, the hospitalist is a practicing clinician — managing throughput on a case-by-case, patient-by-patient basis. In addition, a hospitalist performs a non-clinical role as an “inpatient expert,” taking the lead in creating system changes and communicating those changes to other hospital personnel as well as to community physicians. As an inpatient expert, hospitalists are often asked to lead organization-wide throughput initiatives to identify and implement strategies to facilitate patient flow and efficiency. As dedicated members of multi-disciplinary in-house teams, the hospitalist is in a prime position to foster change and improve systems.

Throughput as Continuum of Care

As suggested by Heffner (5), the process of admission, hospitalization, and discharge resembles a “bell-shaped curve.” To achieve effective throughput, hospitals must expedite patient care and also maintain careful oversight throughout a patient’s entire hospital stay. The hospitalist, as an integral part of a multidisciplinary team, coordinates care to promote a positive outcome and shorten length of stay. Drawing on strong leadership qualities, as well as on intimate knowledge of hospital procedures, layout design and infrastructure, and available community resources, the hospitalist plays a pivotal role in creating efficient throughput from admission to discharge.

Emergency Department

At the front end of the bell-shaped curve, the hospitalist may be engaged by emergency department (ED) physicians to assist in ensuring smooth patient flow and, more important, identifies the “intensity of service” needed. Through the use of clinical criteria, such as lnterQual, the hospitalist, together with the ED physician, may be asked to quantitatively rate the patient’s illness for degree of severity.

Timely patient evaluation helps prevent a backlog of ED cases and enables more patients to be seen. Immediate attention to and initiation of appropriate therapy guarantees a better outcome while minimizing the potential risk for complications, which could possibly lead to longer inpatient stays.

Inpatient Unit

Once a patient has been admitted to an inpatient unit, the hospitalist, together with a multidisciplinary team, facilitates care and determines the inpatient services that will optimize patient recovery through strong interdepartmental communications. Working together with admissions, medical records, nursing, laboratory and diagnostic services, information technology and other pertinent departments, the hospitalist maintains a pulse on all activity surrounding the patient and his care.

Judicious inpatient consultations and treatment decisions result in timely changes in therapy, potentially reducing the length of stay. The frequency with which the hospitalist sees the patient allows him to monitor any changes in condition and reduce possible decompensation, a practice known as vertical continuity (6). Such careful attention may reduce inpatient length of stay significantly. When aggressive management is mandated, the presence of the hospitalist enables initiation of effective therapy and results in quicker discharge and a reduction in potential readmission (7).

Surgery

The surgeon and hospitalist are ideally suited to work together in managing a surgical patient. The hospitalist focuses on the peri-operative management of medical issues and risk reduction, which allows the surgeon to concentrate more on surgical indications and the surgery itself. The hospitalist’s role in the management of a surgical patient enables vertical continuity when the surgeon may be occupied in the operating room with another patient as documented by Huddleston’s Hospitalist Orthopedic Team (HOT) approach (8).

Intensive Care Unit (ICU)

In many hospitals, particularly those that do not have intensivists, hospitalists are able to provide quality care to patients. Even in hospitals where intensivists manage ICU patients, hospitalists work together with the intensivist to ensure smoother transition into and out of the unit.

Discharge

Timing is a critical issue with regard to discharge. Since the hospitalist operates solely in-house and in collaboration with a multidisciplinary team, he is able to round early in the day to discharge patients by mid- or late-morning, freeing a bed for a new patient. In some cases, the hospitalist, in anticipation of early discharge, may begin pre-planning the day prior to discharge, which further expedites the process. Early discharge applies to the ICU, step-down areas and general inpatient care areas, as well as to full discharge from the healthcare facility. Moving a patient from one of these areas enables other patients to fill those empty beds thus optimizing throughput.

Having managed the patient throughout his hospital stay, the hospitalist — again working together with a multidisciplinary team —can facilitate arrangements to send the patient home or to a rehabilitation or skilled nursing facility or alternative housing situation upon discharge, as well as coordinating post-discharge care, whether it be arranging for a visiting nursing or social services or communicating with the primary care physician regarding follow-up appointments. If additional outpatient care is prescribed, the hospitalist will work with the discharge planning staff to contact various community agencies to arrange services best suited to the patient’s needs. Efficient discharge makes possible the admission of other, more critically ill patients, potentially enhancing the hospital’s revenue stream.

Stakeholder Analysis

Five specific stakeholders need to be examined to document the value-added by hospitalists. Anecdotal evidence, as well as documented studies, has demonstrated numerous returns—physical, social, psychological and financial—to stakeholders involved in the hospital process. With regard to throughput, the hospitalist provides benefits to each of the stakeholders listed in Table 1.

Study Results

A dozen studies have been conducted that document the impact of hospital medicine programs on cost and clinical outcomes. Of these trials, nine found a significant decrease in the average length of stay (15%) as well as reductions in cost (9). Two other studies, one from an academic medical center and the other from a community teaching hospital, demonstrate similar reductions during a 2-year follow-up period. At the Western Penn Hospital, a 54% reduction in readmissions was reported with a 12% decrease in hospital costs, while the average LOS was 17% shorter. Additionally, an unpublished study from the University of California, San Francisco Medical Center revealed a consistent 10-15% decline in cost and length of stay between hospitalists and non-hospitalist teaching faculty. More important, those differences remained stable through 6 years of follow-up. In general, hospitals with hospitalist programs realized a 5-39% decrease in costs and a shortened average LOS of 7-25% (6).

According to Robert M. Wachter, author of the 2002 study, “If the average U.S. hospitalist cares for 600 inpatients each year and generates a 10% savings over the average medical inpatient cost of $8,000, the nation’s 4500 hospitalists save approximately $2.2 billion per year while potentially improving quality” (6).

In a study conducted by Douglas Gregory, Walter Baigelman, and Ira B. Wilson, hospitalists at Tufts-New England Medical Center in Boston, MA were found to substantially improve throughput with high baseline occupancy levels. Compared with a control group, the hospitalist group reduced LOS from 3.45 days to 2.19 days (p<.001). Additionally, the total cost of hospital admission decreased from $2,332 to $1,775 (p<.001) when hospitalists were involved. According to the study authors, improved throughput generated an incremental 266 patients per year with a related incremental hospital profitability of $1.3 million with the use of hospitalists (7).

Conclusion

As hospital administrators attempt to address the issue of expeditiously admitting, treating and discharging patients in these days of restricted budgets and increased demand, hospitalist programs are poised as an invaluable factor in the throughput process.

Dr. Cawley can be contacted at pcawley@ushosp.com.

References

- Hospital Statistics: the comprehensive reference source for analysis and comparison of hospital trends. Published annually by Health Forum, an affiliate of the American Hospital Association.

- National and local impact of long-term demographic change on inpatient acute care. 2001. Solucient, LLC.

- Zibulewsky J. The Emergency Medical Treatment and Active Labor Act (EMTALA): what it is and what it means for physicians. Baylor University Medical Center (BUMC) Proceedings. 2001;14:339-46.

- Wachter RM, Goldman L. The emerging role of “hospitalists” in the American health care system. N Eng J Med. 1996;335:514-7.

- Heffner JE. Executive medical director, Medical University of South Carolina (MUSC). Personal interview. June 24, 2004.

- Whitcomb WF. Director, Mercy Inpatient Medicine Service, Mercy Medical Center, Springfield, MA.

- Gregory D, Baigelman W, Wilson IB. Hospital economics of the hospitalist. Health Serv Res. 2003;38:905-18.

- Huddleston JM, Long KH, Naessens JM, et al. Medical and surgical co-management after elective hip and knee arthroplasty: a randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141:28-38.

- Wachter RM. The evolution of the hospitalist model in the United States. Med Clin North Am. 2002;86:687-706.

According to data from the American Hospital Association (1), in 1985, the United States had 5732 operational community hospitals; by 2002, the latest year for which figures are available, the number had decreased to 4927, a loss of approximately 14% (1). In that same timeframe, these hospitals lost approximately 18% of their beds, dropping from just over 1 million to 820,653 beds. This reduction in bed capacity has been accompanied by hospital cost-cutting efforts, staff downsizing, and elimination of services. Many explanations for these trends have been suggested, including changes in Medicare reimbursement and the growth of managed care organizations (MCOs).

However, as the current baby boom generation ages, rising inpatient demands are presenting hospitals with significant challenges. According to a 2001 report from Solucient (2), who maintains the nation’s largest health care database, the senior population—individuals age 65 and older—are projected to experience an 85% growth rate over the next two decades. Since this age group utilizes inpatient services 4.5 times more than younger populations, the number of admissions and beds to accommodate those cases will soar. By the year 2027, hospitals can anticipate a 46% rise in demand for acute inpatient beds as admissions escalate by approximately 13 million cases. Currently, the nation’s healthcare facilities admit 31 million cases; this number will jump to more than 44 million, representing a 41% growth from present admissions figures. For hospitals that maintain an 80% census rate, an additional 238,000 beds will be needed to meet demands (1).

Adding to this increase in demand and pressure on bed capacity, hospitals must address the requirements of the Emergency Medical Treatment and Active Labor Act (EMTALA) passed by the US Congress in 1986 as part of the Consolidated Omnibus Reconciliation Act (COBRA). The law’s initial intent was to ensure patient access to emergency medical care and to prevent the practice of patient dumping, in which uninsured patients were transferred, solely for financial reasons, from private to public hospitals without consideration of their medical condition or stability for the transfer (3). EMTALA mandates that hospitals rank the severity of patients. Thus, tertiary referral centers are required to admit the sickest patients first. This directive presents a significant challenge to many healthcare facilities. High census rates prohibit the admission of elective surgical cases, which, although profitable, are considered second tier. Routine medical cases or complicated emergency surgical cases have the potential to adversely affect the institution’s financial performance.

In addition to the challenge of increased bed demands and EMTALA, hospitals also cite an increasingly smaller number of on-site community physicians. Longstanding trends from inpatient to outpatient care have prompted many community physicians to concentrate their efforts on serving the needs of office-based patients, limiting their accessibility to hospital cases.

To address these pressures, hospitals must execute innovative strategies that deliver efficient throughput and enhance revenue, while still preserving high-quality services. Since 1996, hospital medicine programs have demonstrated a positive impact on the healthcare facility’s ability to increase overall productivity and profitability and still maintain high quality Patients today present to the doctor sicker than in the past and require more careful and frequent outpatient care. Since hospitalists operate solely on an inpatient basis, their availability to efficiently admit and manage hospitalized patients enables delivery of quality care that expedites appropriate treatment and shortens length of stay.

Two Roles of the Hospitalist

According to the Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM), “Hospitalists are physicians whose primary professional focus is the general medical care of hospitalized patients. Their activities include patient care, teaching, research, and leadership related to hospital medicine.” Coined by Drs. Robert Wachter and Lee Goldman in 1996 (4), the term implies an additional point of emphasis. Part of a new paradigm in clinical care, the hospitalist enhances the processes of care surrounding patients and adopts an attitude of accountability for that care. In practice, hospitalists play two key roles.

Primarily, the hospitalist is a practicing clinician — managing throughput on a case-by-case, patient-by-patient basis. In addition, a hospitalist performs a non-clinical role as an “inpatient expert,” taking the lead in creating system changes and communicating those changes to other hospital personnel as well as to community physicians. As an inpatient expert, hospitalists are often asked to lead organization-wide throughput initiatives to identify and implement strategies to facilitate patient flow and efficiency. As dedicated members of multi-disciplinary in-house teams, the hospitalist is in a prime position to foster change and improve systems.

Throughput as Continuum of Care

As suggested by Heffner (5), the process of admission, hospitalization, and discharge resembles a “bell-shaped curve.” To achieve effective throughput, hospitals must expedite patient care and also maintain careful oversight throughout a patient’s entire hospital stay. The hospitalist, as an integral part of a multidisciplinary team, coordinates care to promote a positive outcome and shorten length of stay. Drawing on strong leadership qualities, as well as on intimate knowledge of hospital procedures, layout design and infrastructure, and available community resources, the hospitalist plays a pivotal role in creating efficient throughput from admission to discharge.

Emergency Department

At the front end of the bell-shaped curve, the hospitalist may be engaged by emergency department (ED) physicians to assist in ensuring smooth patient flow and, more important, identifies the “intensity of service” needed. Through the use of clinical criteria, such as lnterQual, the hospitalist, together with the ED physician, may be asked to quantitatively rate the patient’s illness for degree of severity.

Timely patient evaluation helps prevent a backlog of ED cases and enables more patients to be seen. Immediate attention to and initiation of appropriate therapy guarantees a better outcome while minimizing the potential risk for complications, which could possibly lead to longer inpatient stays.

Inpatient Unit

Once a patient has been admitted to an inpatient unit, the hospitalist, together with a multidisciplinary team, facilitates care and determines the inpatient services that will optimize patient recovery through strong interdepartmental communications. Working together with admissions, medical records, nursing, laboratory and diagnostic services, information technology and other pertinent departments, the hospitalist maintains a pulse on all activity surrounding the patient and his care.

Judicious inpatient consultations and treatment decisions result in timely changes in therapy, potentially reducing the length of stay. The frequency with which the hospitalist sees the patient allows him to monitor any changes in condition and reduce possible decompensation, a practice known as vertical continuity (6). Such careful attention may reduce inpatient length of stay significantly. When aggressive management is mandated, the presence of the hospitalist enables initiation of effective therapy and results in quicker discharge and a reduction in potential readmission (7).

Surgery

The surgeon and hospitalist are ideally suited to work together in managing a surgical patient. The hospitalist focuses on the peri-operative management of medical issues and risk reduction, which allows the surgeon to concentrate more on surgical indications and the surgery itself. The hospitalist’s role in the management of a surgical patient enables vertical continuity when the surgeon may be occupied in the operating room with another patient as documented by Huddleston’s Hospitalist Orthopedic Team (HOT) approach (8).

Intensive Care Unit (ICU)

In many hospitals, particularly those that do not have intensivists, hospitalists are able to provide quality care to patients. Even in hospitals where intensivists manage ICU patients, hospitalists work together with the intensivist to ensure smoother transition into and out of the unit.

Discharge

Timing is a critical issue with regard to discharge. Since the hospitalist operates solely in-house and in collaboration with a multidisciplinary team, he is able to round early in the day to discharge patients by mid- or late-morning, freeing a bed for a new patient. In some cases, the hospitalist, in anticipation of early discharge, may begin pre-planning the day prior to discharge, which further expedites the process. Early discharge applies to the ICU, step-down areas and general inpatient care areas, as well as to full discharge from the healthcare facility. Moving a patient from one of these areas enables other patients to fill those empty beds thus optimizing throughput.

Having managed the patient throughout his hospital stay, the hospitalist — again working together with a multidisciplinary team —can facilitate arrangements to send the patient home or to a rehabilitation or skilled nursing facility or alternative housing situation upon discharge, as well as coordinating post-discharge care, whether it be arranging for a visiting nursing or social services or communicating with the primary care physician regarding follow-up appointments. If additional outpatient care is prescribed, the hospitalist will work with the discharge planning staff to contact various community agencies to arrange services best suited to the patient’s needs. Efficient discharge makes possible the admission of other, more critically ill patients, potentially enhancing the hospital’s revenue stream.

Stakeholder Analysis

Five specific stakeholders need to be examined to document the value-added by hospitalists. Anecdotal evidence, as well as documented studies, has demonstrated numerous returns—physical, social, psychological and financial—to stakeholders involved in the hospital process. With regard to throughput, the hospitalist provides benefits to each of the stakeholders listed in Table 1.

Study Results

A dozen studies have been conducted that document the impact of hospital medicine programs on cost and clinical outcomes. Of these trials, nine found a significant decrease in the average length of stay (15%) as well as reductions in cost (9). Two other studies, one from an academic medical center and the other from a community teaching hospital, demonstrate similar reductions during a 2-year follow-up period. At the Western Penn Hospital, a 54% reduction in readmissions was reported with a 12% decrease in hospital costs, while the average LOS was 17% shorter. Additionally, an unpublished study from the University of California, San Francisco Medical Center revealed a consistent 10-15% decline in cost and length of stay between hospitalists and non-hospitalist teaching faculty. More important, those differences remained stable through 6 years of follow-up. In general, hospitals with hospitalist programs realized a 5-39% decrease in costs and a shortened average LOS of 7-25% (6).

According to Robert M. Wachter, author of the 2002 study, “If the average U.S. hospitalist cares for 600 inpatients each year and generates a 10% savings over the average medical inpatient cost of $8,000, the nation’s 4500 hospitalists save approximately $2.2 billion per year while potentially improving quality” (6).

In a study conducted by Douglas Gregory, Walter Baigelman, and Ira B. Wilson, hospitalists at Tufts-New England Medical Center in Boston, MA were found to substantially improve throughput with high baseline occupancy levels. Compared with a control group, the hospitalist group reduced LOS from 3.45 days to 2.19 days (p<.001). Additionally, the total cost of hospital admission decreased from $2,332 to $1,775 (p<.001) when hospitalists were involved. According to the study authors, improved throughput generated an incremental 266 patients per year with a related incremental hospital profitability of $1.3 million with the use of hospitalists (7).

Conclusion

As hospital administrators attempt to address the issue of expeditiously admitting, treating and discharging patients in these days of restricted budgets and increased demand, hospitalist programs are poised as an invaluable factor in the throughput process.

Dr. Cawley can be contacted at pcawley@ushosp.com.

References

- Hospital Statistics: the comprehensive reference source for analysis and comparison of hospital trends. Published annually by Health Forum, an affiliate of the American Hospital Association.

- National and local impact of long-term demographic change on inpatient acute care. 2001. Solucient, LLC.

- Zibulewsky J. The Emergency Medical Treatment and Active Labor Act (EMTALA): what it is and what it means for physicians. Baylor University Medical Center (BUMC) Proceedings. 2001;14:339-46.

- Wachter RM, Goldman L. The emerging role of “hospitalists” in the American health care system. N Eng J Med. 1996;335:514-7.

- Heffner JE. Executive medical director, Medical University of South Carolina (MUSC). Personal interview. June 24, 2004.

- Whitcomb WF. Director, Mercy Inpatient Medicine Service, Mercy Medical Center, Springfield, MA.

- Gregory D, Baigelman W, Wilson IB. Hospital economics of the hospitalist. Health Serv Res. 2003;38:905-18.

- Huddleston JM, Long KH, Naessens JM, et al. Medical and surgical co-management after elective hip and knee arthroplasty: a randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141:28-38.

- Wachter RM. The evolution of the hospitalist model in the United States. Med Clin North Am. 2002;86:687-706.

Improving Resource Utilization

Today’s hospitals must address a variety of challenges stemming from the expectation to provide more services and better quality with fewer financial, material, and human resources. According to the annual survey conducted by the American Hospital Association (AHA) in 2003, total expenses for all U.S. community hospitals were more than $450 billion. In managing these expenditures, hospitals face the following pressures:

- Cost increases in medical supplies and pharmaceuticals.

- Record shortages of nurses, pharmacists, and technicians.

- A growing uncompensated patient pool.

- Annual potential reductions in Medicare and Medicaid reimbursements.

- Rising bad debt resulting from greater patient responsibility for the cost of care.

- The diversion of more profitable cases to specialty and freestanding ambulatory care facilities and surgery centers.

- Soaring costs associated with adequately serving high-risk conditions, such as cancer, heart disease, and HIV/AIDS.

- Discounted reimbursement rates with insurers.

- Increasing pressure to commit financial resources to clinical information technology.

- The need to fund infrastructure improvements and physical plant renovations as well as expansions to address increasing demand (1).

To overcome these challenges, hospitals must find innovative ways to balance revenues and expenses, fund necessary capital investments, and satisfy the public’s demand for quality, safety, and accessibility.

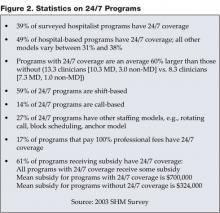

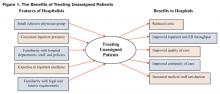

Hospitalist Programs: A Good Investment

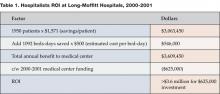

One solution to the above-mentioned situations is a hospitalist program, which, in its short history, has already had a profound impact on inpatient care. Robert M. Wachter, MD, associate chair in the department of medicine at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) and medical service chief at Moffitt-Long Hospitals, coined the term Hospitalist in an article in the New England Journal of Medicine in 1996 (2). At the 2002 annual meeting of the Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM), Wachter presented findings from a study conducted at his institution. The results demonstrate a significant return on investment (ROI) of 5.8:1 when a hospitalist program is utilized (See Table 1 for details) (3).

How do hospitalists reduce length of stay (LOS) and cost per stay? William David Rifkin, MD, associate director of the Yale Primary Care Residency Program, offers three basic reasons why hospitalist programs contribute to effective and efficient use of resources. Since hospitalists are physically onsite, they are better able to react to condition changes and requests for consultations in a timely manner, he asserts. Also, being familiar with the hospital’s systems of care, the hospitalist knows who to call and how to utilize the services of social workers and other contingency staff when arranging for post-discharge care. Third, Rifkin indicates that inpatients today are sicker than they were in past years, a fact well known and understood by hospitalists. “There is an increased level of acuity,” he says. “Hospitalists are used to seeing these kinds of patients. They are more comfortable taking care of these patients and will see more of them with any given diagnosis” (4).

In one of his studies, Rifkin noted a reduction in LOS for inpatients with a pneumonia diagnosis. “The hospitalist had switched the patient from IV (intravenous) to oral antibiotics,” he says. Reacting quickly to indications that the patient was ready for a change in treatment modality facilitated an earlier discharge (5).

L. Craig Miller, MD, senior vice president of medical affairs at Baptist Health Care, reports that his hospital saved $2.56 million in 2 years as a direct result of its inpatient management program (6). Although attention to technical and clinical details is important, Miller emphasizes the critical role the human factor plays, specifically the impact of teamwork, on achieving resource utilization savings.

“Hospitalists work as a team, collaborating with physicians and ED doctors,” he says. This cooperative spirit enables the efficient use of manpower in patient care. Miller adds that at Baptist, as is the case at most hospitals, the medical complexity of patients dictates a need for cooperation in order to successfully treat illness. The presence of hospitalists facilitates the team effort, causing a positive trickle down effect regarding LOS, readmission and mortality rates, he affirms. “The hospitalist provides focused leadership to utilization resource management,” says Miller (7).