User login

Stories of the Heart: Illness Narratives of Veterans Living With Heart Failure

Heart failure (HF) is a costly and burdensome illness and is the top reason for hospital admissions for the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) and Medicare.1 The cost of HF to the United States is estimated to grow to $3 billion annually by 2030.2 People living with HF have a high symptom burden and poor quality of life.3,4 Symptoms include shortness of breath, fatigue, depression, and decreases in psychosocial, existential, and spiritual well-being.5-9

Veterans in the US are a unique cultural group with distinct contextual considerations around their experiences.10 Different groups of veterans require unique cultural considerations, such as the experiences of veterans who served during the Vietnam war and during Operation Iraqi Freedom/Operation Enduring Freedom (OIF/OEF). The extent of unmet needs of people living with HF, the number of veterans living with this illness, and the unique contextual components related to living with HF among veterans require further exploration into this illness experience for this distinct population. Research should explore innovative ways of managing both the number of people living with the illness and the significant impact of HF in people’s lives due to the high symptom burden and poor quality of life.3

This study used the model of adjustment to illness to explore the psychosocial adjustment to illness and the experience of US veterans living with HF, with a focus on the domains of meaning creation, self-schema, and world schema.11 The model of adjustment to illness describes how people learn to adjust to living with an illness, which can lead to positive health outcomes. Meaning creation is defined as the process in which people create meaning from their experience living with illness. Self-schema is how people living with illness see themselves, and world schema is how people living with chronic illness see their place in the world. These domains shift as part of the adjustment to living with an illness described in this model.11 This foundation allowed the investigators to explore the experience of living with HF among veterans with a focus on these domains. Our study aimed to cocreate illness narratives among veterans living with HF and to explore components of psychosocial adjustment informed by the model.

Methods

This study used narrative inquiry with a focus on illness narratives.12-17 Narrative inquiry as defined by Catherine Riessman involves the generation of socially constructed and cocreated meanings between the researcher and narrator. The researcher is an active participant in narrative creation as the narrator chooses which events to include in the stories based on the social, historical, and cultural context of both the narrator (study participant) and audience (researcher). Riessman describes the importance of contextual factors and meaning creation as an important aspect of narrative inquiry.12-14,16,17 It is important in narrative inquiry to consider how cultural, social, and historical factors influence narrative creation, constriction, and/or elimination.

This study prospectively created and collected data at a single time point. Semi-structured interviews explored psychosocial adjustment for people living with HF using an opening question modified from previous illness narrative research: Why do you think you got heart failure?18 Probes included the domains of psychosocial adjustment informed by the model of adjustment to illness domains (Figure). Emergent probes were used to illicit additional data around psychosocial adjustment to illness. Data were created and collected in accordance with narrative inquiry during the cocreation of the illness narratives between the researcher and study participants. This interview guide was tested by the first author in preliminary work to prepare for this study.

Allowing for emergent probes and acknowledging the role of the researcher as audience is key to the cocreation of narratives using this methodological framework. Narrators shape their narrative with the audience in mind; they cocreate their narrative with their audience using this type of narrative inquiry.12,16 What the narrator chooses to include and exclude from their story provides a window into how they see themselves and their world.19 Audio recordings were used to capture data, allowing for the researcher to take contemporaneous notes exploring contextual considerations to the narrative cocreation process and to be used later in analysis. Analytic notes were completed during the interviews as well as later in analysis as part of the contextual reflection.

Setting

Research was conducted in the Rocky Mountain Regional VA Medical Center, Aurora, Colorado. Participants were recruited through the outpatient cardiology clinic where the interviews also took place. This study was approved through the Colorado Institutional Review Board and Rocky Mountain Regional VA Medical Center (IRB: 19-1064). Participants were identified by the treating cardiologist who was a part of the study team. Interested veterans were introduced to the first author who was stationed in an empty clinic room. The study cardiologist screened to ensure all participants were ≥ 18 years of age and had a diagnosis of HF for > 1 year. Persons with an impairment that could interfere with their ability to construct a narrative were also excluded.

Recruitment took place from October 2019 to January 2020. Three veterans refused participation. Five study participants provided informed consent and were enrolled and interviewed. All interviews were completed in the clinic at the time of consent per participant preference. One-hour long semi-structured interviews were conducted and audio recorded. A demographic form was administered at the end of each interview to capture contextual data. The researcher also kept a reflexive journal and audit trail.

Narrative Analysis

Riessman described general steps to conduct narrative analysis, including transcription, narrative clean-up, consideration of contextual factors, exploration of thematic threads, consideration of larger social narratives, and positioning.12 The first author read transcripts while listening to the audio recordings to ensure accuracy. With narrative clean-up each narrative was organized to cocreate overall meaning, changed to protect anonymity, and refined to only include the illness narrative. For example, if a narrator told a story about childhood and then later in the interview remembered another detail to add to their story, narrative clean-up reordered events to make cohesive sense of the story. Demographic, historical, cultural, and social contexts of both the narrator and audience were reflected on during analysis to explore how these components may have shaped and influenced cocreation. Context was also considered within the larger VA setting.

Emergent themes were explored for convergence, divergence, and points of tension within and across each narrative. Larger social narratives were also considered for their influence on possible inclusion/exclusion of experience, such as how gender identity may have influenced study participants’ descriptions of their roles in social systems. These themes and narratives were then shared with our team, and we worked through decision points during the analysis process and discussed interpretation of the data to reach consensus.

Results

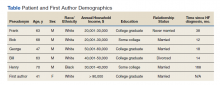

Five veterans living with HF were recruited and consented to participate in the study. Demographics of the participants and first author are included in the Table. Five illness narratives were cocreated, entitled: Blame the Cheese: Frank’s Illness Narrative; Love is Love: Bob’s Illness Narrative; The Brighter Things in Life is My Family: George’s Illness Narrative; We Never Know When Our Time is Coming: Bill’s Illness Narrative; and A Dream Deferred: Henry’s Illness Narrative.

Each narrative was explored focusing on the domains of the model of adjustment to illness. An emergent theme was also identified with multiple subthemes: being a veteran is unique. Related subthemes included: financial benefits, intersectionality of government and health care, the intersectionality of masculinity and military service, and the dichotomy of military experience.

The search for meaning creation after the experience of chronic illness emerged across interviews. One example of meaning creation was in Frank's illness narrative. Frank was unsure why he got HF: “Probably because I ate too much cheese…I mean, that’s gotta be it. It can’t be anything else.” By tying HF to his diet, he found meaning through his health behaviors.

Model of Adjustment to Illness

The narratives illustrate components of the model of adjustment to illness and describe how each of the participants either shifted their self-schema and world schema or reinforced their previously established schemas. It also demonstrates how people use narratives to create meaning and illness understanding from their illness experience, reflecting, and emphasizing different parts creating meaning from their experience.

A commonality across the narratives was a shift in self-schema, including the shift from being a provider to being reliant on others. In accordance with the dominant social narrative around men as providers, each narrator talked about their identity as a provider for themselves and their families. Often keeping their provider identity required modifications of the definition, from physical abilities and employment to financial security and stability. George made all his health care decisions based on his goal of providing for his family and protecting them from having to care for him: “I’m always thinking about the future, always trying to figure out how my family, if something should happen to me, how my family would cope, and how my family would be able to support themselves.” Bob’s health care goals were to stay alive long enough for his wife to get financial benefits as a surviving spouse: “That’s why I’m trying to make everything for her, you know. I’m not worried about myself. I’m not. Her I am, you know. And love is love.” Both of their health care decisions are shaped by their identity as a provider shifting to financial support.

Some narrators changed the way they saw their world, or world schema, while others felt their illness experience just reinforced the way they had already experienced the world. Frank was able to reprioritize what was important to him after his diagnosis and accept his own mortality: “I might as well chill out, no more stress, and just enjoy things ’cause you could die…” For Henry, getting HF was only part of the experience of systemic oppression that had impacted his and his family’s lives for generations. He saw how his oppression by the military and US government led to his father’s exposure to chemicals that Henry believed he inherited and caused his illness. Henry’s illness experience reinforced his distrust in the institutions that were oppressed him and his family.

Veteran Status

Being a veteran in the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) system impacted how a narrative understanding of illness was created. Veterans are a unique cultural population with aspects of their illness experience that are important to understand.10 Institutions such as the VA also enable and constrain components of narrative creation.20 The illness narratives in this study were cocreated within the institutional setting of the VA. Part of the analysis included exploring how the institutional setting impacted the narrative creation. Emergent subthemes of the uniqueness of the veteran experience include financial benefits, intersectionality of government and health care, intersectionality of masculinity and military service, and the dichotomy of military experience.

In the US it is unique to the VA that the government both treats and assesses the severity of medical conditions to determine eligibility for health care and financial benefits. The VA’s financial benefits are intended to help compensate veterans who are experiencing illness as a result of their military experience.21 However, because the VA administers them the Veterans Benefits Administration and the VHA, veterans see both as interconnected. The perceived tie between illness severity and financial compensation could influence or bias how veterans understand their illness severity and experience. This may inadvertently encourage veterans to see their illness as being tied to their military service. This shaping of narratives should be considered as a contextual component as veterans obtain financial compensation and health insurance from the same larger organization that provides their health care and management.

George was a young man who during his service had chest pains and felt tired during physical training. He was surprised when his cardiologist explained his heart was enlarged. “All I know is when I initially joined the military, I was perfectly fine, you know, and when I was in the military, graduating, all that stuff, there was a glitch on the [electrocardiogram] they gave me after one day of doing [physical training] and then they’re like, oh, that’s fine. Come to find out it was mitral valve prolapse. And the doctors didn’t catch it then.” George feels the stress of the military caused his heart problems: “It wasn’t there before… so I’d have to say the strain from the military had to have caused it.” George’s medical history noted that he has a genetic connective tissue disorder that can lead to HF and likely was underlying cause of his illness. This example of how George pruned his narrative experience to highlight the cause as his military experience instead of a genetic disorder could have multiple financial and health benefits. The financial incentive for George to see his illness as caused by his military service could potentially bias his illness narrative to find his illness cause as tied to his service.

Government/Health Care Intersectionality

Veterans who may have experienced trust-breaking events with the government, like Agent Orange exposure or intergenerational racial trauma, may apply that experience to all government agencies. Bob felt the government had purposefully used him to create a military weapon. The army “knew I was angry and they used that for their advantage,” he said. Bob learned that he was exposed to Agent Orange in Vietnam, which is presumed to be associated with HF. Bob felt betrayed that the VHA had not figured out his health problems earlier. “I didn’t know anything about it until 6 months ago… Our government knew about it when they used it, and they didn’t care. They just wanted to win the war, and a whole lot of GIs like me suffered because of that, and I was like my government killed me? And I was fighting for them?”

Henry learned to distrust the government and the health care system because of a long history of systematic oppression and exploitation. These institutions’ erosion of trust has impact beyond the trust-breaking event itself but reverberates into how communities view organizations and institutions for generations. For Black Americans, who have historically been experimented on without consent by the US government and health care systems, this can make it especially hard to trust and build working relationships with those institutions. Health care professionals (HCPs) need to build collaborative partnerships with patients to provide effective care while understanding why some patients may have difficulty trusting health care systems, especially government-led systems.

The nature of HF as an illness can also make it difficult to predict and manage.22 This uncertainty and difficulty in managing HF can make it especially hard for people to establish trust with their HCPs whom they want to see as experts in their illness. HCPs in these narratives were often portrayed as incompetent or neglectful. The unpredictable nature of the illness itself was not reflected in the narrator’s experience.

Masculinity/Military Service Intersectionality

For the veteran narrators, tied into the identity of being a provider are social messages about masculinity. There is a unique intersectionality of being a man, the military culture, and living with chronic illnesses. Dominant social messages around being a man include being tough, not expressing emotion, self-reliance, and having power. This overlaps with social messages on military culture, including self-reliance, toughness, persistence in the face of adversity, limited expression of emotions, and the recognition of power and respect.23

People who internalize these social messages on masculinity may be less likely to access mental health treatment.23 This stigmatizing barrier to mental health treatment could impact how positive narratives are constructed around the experience of chronic illness for narrators who identify as masculine. Military and masculine identity could exclude or constrain stories about a veteran who did not “solider on” or who had to rely on others in a team to get things done. This shift can especially impact veterans experiencing chronic illnesses like HF, which often impact their physical abilities. Veterans may feel pressured to think of and portray themselves as being strong by limiting their expression of pain and other symptoms to remain in alignment with the dominant narrative. By not being open about the full experience of their illness both positive and negative, veterans may have unaddressed aspects of their illness experience or HCPs may not be able have all the information they need before the concern becomes a more serious health problem.

Dichotomy of Military Experience

Some narrators in this study talked about their military experience as both traumatic and beneficial. These dichotomous viewpoints can be difficult for veterans to construct a narrative understanding around. How can an inherently painful potentially traumatic experience, such as war, have benefits? This way of looking at the world may require a large narrative shift in their world and self-schemas to accept.

Bob hurt people in Vietnam as part of his job. “I did a lot of killing.” Bob met a village elder who stopped him from hurting people in the village and “in my spare time, I would go back to the village and he would teach me, how to be a better man,” Bob shared. “He taught me about life and everything, and he was awesome, just to this day, he’s like a father to me.” Bob tried to change his life and learned how to live a life full of love and care because of his experience in Vietnam. Though Bob hurt a lot of people in Vietnam, which still haunts him, he found meaning through his life lessons from the village elder. “I’m ashamed of what I did in Vietnam. I did some really bad stuff, but ever since then, I’ve always tried to do good to help people.”

Discussion

Exploring a person’s illness experience from a truly holistic pathway allows HCPs to see how the ripples of illness echo into the interconnection of surrounding systems and even across time. These stories suggest that veterans may experience their illness and construct their illness narratives based on the distinct contextual considerations of veteran culture.10 Research exploring how veterans see their illness and its potential impact on their health care access and choices could benefit from exploration into narrative understanding and meaning creation as a potentially contributing factor to health care decision making. As veterans are treated across health care systems, this has implications not only for VHA care, but community care as well.

These narratives also demonstrate how veterans create health care goals woven into their narrative understanding of their illness and its cause, lending insight into understanding health care decision making. This change in self-schema shapes how veterans see themselves and their role which shapes other aspects of their health care. These findings also contribute to our understanding of meaning creation. By exploring meaning making and narrative understanding, this work adds to our knowledge of the importance of spirituality as a component of the holistic experience of illness. There have been previous studies exploring the spiritual aspects of HF and the importance of meaning making.24,25 Exploring meaning making as an aspect of illness narratives can have important implications. Future research could explore the connections between meaning creation and illness narratives.

Limitations

The sample of veterans who participated in this study and are not generalizable to all veteran populations. The sample also only reflects people who were willing to participate and may exclude experience of people who may not have felt comfortable talking to a VA employee about their experience. It is also important to note that the small sample size included primarily male and White participants. In narrative inquiry, the number of participants is not as essential as diving into the depth of the interviews with the participants.

It is also important to note the position of the interviewer. As a White cisgender, heterosexual, middle-aged, middle class female who was raised in rural Kansas in a predominantly Protestant community, the positionality of the interviewer as a cocreator of the data inherently shaped and influenced the narratives created during this study. This contextual understanding of narratives created within the research relationship is an essential component to narrative inquiry and understanding.

Conclusions

Exploring these veterans’ narrative understanding of their experience of illness has many potential implications for health care systems, HCPs, and our military and veteran populations described in this article. Thinking about how the impact of racism, the influence of incentives to remain ill, and the complex intersection of identity and health brings light to how these domains may influence how people see themselves and engage in health care. These domains from these stories of the heart may help millions of people living with chronic illnesses like HF to not only live with their illness but inform how their experience is shaped by the systems surrounding them, including health care, government, and systems of power and oppression.

1. Ashton CM, Bozkurt B, Colucci WB, et al. Veterans Affairs quality enhancement research initiative in chronic heart failure. Medical care. 2000;38(6):I-26-I-37.

2. Writing Group Members, Mozaffarian D, Benjamin EJ, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics-2016 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2016;133(4):e38-e360. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000350

3. Blinderman CD, Homel P, Billings JA, Portenoy RK, Tennstedt SL. Symptom distress and quality of life in patients with advanced congestive heart failure. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2008;35(6):594-603. doi:10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2007.06.007

4. Zambroski CH. Qualitative analysis of living with heart failure. Heart Lung. 2003;32(1):32-40. doi:10.1067/mhl.2003.10

5. Walthall H, Jenkinson C, Boulton M. Living with breathlessness in chronic heart failure: a qualitative study. J Clin Nurs. 2017;26(13-14):2036-2044. doi:10.1111/jocn.13615

6. Francis GS, Greenberg BH, Hsu DT, et al. ACCF/AHA/ACP/HFSA/ISHLT 2010 clinical competence statement on management of patients with advanced heart failure and cardiac transplant: a report of the ACCF/AHA/ACP Task Force on Clinical Competence and Training. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;56(5):424-453. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2010.04.014

7. Rumsfeld JS, Havranek E, Masoudi FA, et al. Depressive symptoms are the strongest predictors of short-term declines in health status in patients with heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;42(10):1811-1817. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2003.07.013

8. Leeming A, Murray SA, Kendall M. The impact of advanced heart failure on social, psychological and existential aspects and personhood. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2014;13(2):162-167. doi:10.1177/1474515114520771

9. Bekelman DB, Havranek EP, Becker DM, et al. Symptoms, depression, and quality of life in patients with heart failure. J Card Fail. 2007;13(8):643-648. doi:10.1016/j.cardfail.2007.05.005

10. Weiss E, Coll JE. The influence of military culture and veteran worldviews on mental health treatment: practice implications for combat veteran help-seeking and wellness. Int J Health, Wellness Society. 2011;1(2):75-86. doi:10.18848/2156-8960/CGP/v01i02/41168

11. Sharpe L, Curran L. Understanding the process of adjustment to illness. Soc Sci Med. 2006;62(5):1153-1166. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.07.010

12. Riessman CK. Narrative Methods for the Human Sciences. SAGE Publications; 2008.

13. Riessman CK. Performing identities in illness narrative: masculinity and multiple sclerosis. Qualitative Research. 2003;3(1):5-33. doi:10.1177/146879410300300101

14. Riessman CK. Strategic uses of narrative in the presentation of self and illness: a research note. Soc Sci Med. 1990;30(11):1195-1200. doi:10.1016/0277-9536(90)90259-U

15. Riessman CK. Analysis of personal narratives. In: Handbook of Interview Research. Sage; 2002:695-710.

16. Riessman CK. Illness Narratives: Positioned Identities. Invited Annual Lecture. Cardiff University. May 2002. Accessed April 14 2022. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/241501264_Illness_Narratives_Positioned_Identities

17. Riessman CK. Performing identities in illness narrative: masculinity and multiple sclerosis. Qual Res. 2003;3(1):5-33. doi:10.1177/146879410300300101

18. Williams G. The genesis of chronic illness: narrative re‐construction. Sociol Health Illn. 1984;6(2):175-200. doi:10.1111/1467-9566.ep10778250

19. White M, Epston D. Narrative Means to Therapeutic Ends. WW Norton & Company; 1990.

20. Burchardt M. Illness Narratives as Theory and Method. SAGE Publications; 2020.

21. Sayer NA, Spoont M, Nelson D. Veterans seeking disability benefits for post-traumatic stress disorder: who applies and the self-reported meaning of disability compensation. Soc Sci Med. 2004;58(11):2133-2143. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2003.08.009

22. Winters CA. Heart failure: living with uncertainty. Prog Cardiovasc Nurs. 1999;14(3):85.

23. Plys E, Smith R, Jacobs ML. Masculinity and military culture in VA hospice and palliative care: a narrative review with clinical recommendations. J Palliat Care. 2020;35(2):120-126. doi:10.1177/0825859719851483

24. Johnson LS. Facilitating spiritual meaning‐making for the individual with a diagnosis of a terminal illness. Counseling and Values. 2003;47(3):230-240. doi:10.1002/j.2161-007X.2003.tb00269.x

25. Shahrbabaki PM, Nouhi E, Kazemi M, Ahmadi F. Defective support network: a major obstacle to coping for patients with heart failure: a qualitative study. Glob Health Action. 2016;9:30767. Published 2016 Apr 1. doi:10.3402/gha.v9.30767

Heart failure (HF) is a costly and burdensome illness and is the top reason for hospital admissions for the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) and Medicare.1 The cost of HF to the United States is estimated to grow to $3 billion annually by 2030.2 People living with HF have a high symptom burden and poor quality of life.3,4 Symptoms include shortness of breath, fatigue, depression, and decreases in psychosocial, existential, and spiritual well-being.5-9

Veterans in the US are a unique cultural group with distinct contextual considerations around their experiences.10 Different groups of veterans require unique cultural considerations, such as the experiences of veterans who served during the Vietnam war and during Operation Iraqi Freedom/Operation Enduring Freedom (OIF/OEF). The extent of unmet needs of people living with HF, the number of veterans living with this illness, and the unique contextual components related to living with HF among veterans require further exploration into this illness experience for this distinct population. Research should explore innovative ways of managing both the number of people living with the illness and the significant impact of HF in people’s lives due to the high symptom burden and poor quality of life.3

This study used the model of adjustment to illness to explore the psychosocial adjustment to illness and the experience of US veterans living with HF, with a focus on the domains of meaning creation, self-schema, and world schema.11 The model of adjustment to illness describes how people learn to adjust to living with an illness, which can lead to positive health outcomes. Meaning creation is defined as the process in which people create meaning from their experience living with illness. Self-schema is how people living with illness see themselves, and world schema is how people living with chronic illness see their place in the world. These domains shift as part of the adjustment to living with an illness described in this model.11 This foundation allowed the investigators to explore the experience of living with HF among veterans with a focus on these domains. Our study aimed to cocreate illness narratives among veterans living with HF and to explore components of psychosocial adjustment informed by the model.

Methods

This study used narrative inquiry with a focus on illness narratives.12-17 Narrative inquiry as defined by Catherine Riessman involves the generation of socially constructed and cocreated meanings between the researcher and narrator. The researcher is an active participant in narrative creation as the narrator chooses which events to include in the stories based on the social, historical, and cultural context of both the narrator (study participant) and audience (researcher). Riessman describes the importance of contextual factors and meaning creation as an important aspect of narrative inquiry.12-14,16,17 It is important in narrative inquiry to consider how cultural, social, and historical factors influence narrative creation, constriction, and/or elimination.

This study prospectively created and collected data at a single time point. Semi-structured interviews explored psychosocial adjustment for people living with HF using an opening question modified from previous illness narrative research: Why do you think you got heart failure?18 Probes included the domains of psychosocial adjustment informed by the model of adjustment to illness domains (Figure). Emergent probes were used to illicit additional data around psychosocial adjustment to illness. Data were created and collected in accordance with narrative inquiry during the cocreation of the illness narratives between the researcher and study participants. This interview guide was tested by the first author in preliminary work to prepare for this study.

Allowing for emergent probes and acknowledging the role of the researcher as audience is key to the cocreation of narratives using this methodological framework. Narrators shape their narrative with the audience in mind; they cocreate their narrative with their audience using this type of narrative inquiry.12,16 What the narrator chooses to include and exclude from their story provides a window into how they see themselves and their world.19 Audio recordings were used to capture data, allowing for the researcher to take contemporaneous notes exploring contextual considerations to the narrative cocreation process and to be used later in analysis. Analytic notes were completed during the interviews as well as later in analysis as part of the contextual reflection.

Setting

Research was conducted in the Rocky Mountain Regional VA Medical Center, Aurora, Colorado. Participants were recruited through the outpatient cardiology clinic where the interviews also took place. This study was approved through the Colorado Institutional Review Board and Rocky Mountain Regional VA Medical Center (IRB: 19-1064). Participants were identified by the treating cardiologist who was a part of the study team. Interested veterans were introduced to the first author who was stationed in an empty clinic room. The study cardiologist screened to ensure all participants were ≥ 18 years of age and had a diagnosis of HF for > 1 year. Persons with an impairment that could interfere with their ability to construct a narrative were also excluded.

Recruitment took place from October 2019 to January 2020. Three veterans refused participation. Five study participants provided informed consent and were enrolled and interviewed. All interviews were completed in the clinic at the time of consent per participant preference. One-hour long semi-structured interviews were conducted and audio recorded. A demographic form was administered at the end of each interview to capture contextual data. The researcher also kept a reflexive journal and audit trail.

Narrative Analysis

Riessman described general steps to conduct narrative analysis, including transcription, narrative clean-up, consideration of contextual factors, exploration of thematic threads, consideration of larger social narratives, and positioning.12 The first author read transcripts while listening to the audio recordings to ensure accuracy. With narrative clean-up each narrative was organized to cocreate overall meaning, changed to protect anonymity, and refined to only include the illness narrative. For example, if a narrator told a story about childhood and then later in the interview remembered another detail to add to their story, narrative clean-up reordered events to make cohesive sense of the story. Demographic, historical, cultural, and social contexts of both the narrator and audience were reflected on during analysis to explore how these components may have shaped and influenced cocreation. Context was also considered within the larger VA setting.

Emergent themes were explored for convergence, divergence, and points of tension within and across each narrative. Larger social narratives were also considered for their influence on possible inclusion/exclusion of experience, such as how gender identity may have influenced study participants’ descriptions of their roles in social systems. These themes and narratives were then shared with our team, and we worked through decision points during the analysis process and discussed interpretation of the data to reach consensus.

Results

Five veterans living with HF were recruited and consented to participate in the study. Demographics of the participants and first author are included in the Table. Five illness narratives were cocreated, entitled: Blame the Cheese: Frank’s Illness Narrative; Love is Love: Bob’s Illness Narrative; The Brighter Things in Life is My Family: George’s Illness Narrative; We Never Know When Our Time is Coming: Bill’s Illness Narrative; and A Dream Deferred: Henry’s Illness Narrative.

Each narrative was explored focusing on the domains of the model of adjustment to illness. An emergent theme was also identified with multiple subthemes: being a veteran is unique. Related subthemes included: financial benefits, intersectionality of government and health care, the intersectionality of masculinity and military service, and the dichotomy of military experience.

The search for meaning creation after the experience of chronic illness emerged across interviews. One example of meaning creation was in Frank's illness narrative. Frank was unsure why he got HF: “Probably because I ate too much cheese…I mean, that’s gotta be it. It can’t be anything else.” By tying HF to his diet, he found meaning through his health behaviors.

Model of Adjustment to Illness

The narratives illustrate components of the model of adjustment to illness and describe how each of the participants either shifted their self-schema and world schema or reinforced their previously established schemas. It also demonstrates how people use narratives to create meaning and illness understanding from their illness experience, reflecting, and emphasizing different parts creating meaning from their experience.

A commonality across the narratives was a shift in self-schema, including the shift from being a provider to being reliant on others. In accordance with the dominant social narrative around men as providers, each narrator talked about their identity as a provider for themselves and their families. Often keeping their provider identity required modifications of the definition, from physical abilities and employment to financial security and stability. George made all his health care decisions based on his goal of providing for his family and protecting them from having to care for him: “I’m always thinking about the future, always trying to figure out how my family, if something should happen to me, how my family would cope, and how my family would be able to support themselves.” Bob’s health care goals were to stay alive long enough for his wife to get financial benefits as a surviving spouse: “That’s why I’m trying to make everything for her, you know. I’m not worried about myself. I’m not. Her I am, you know. And love is love.” Both of their health care decisions are shaped by their identity as a provider shifting to financial support.

Some narrators changed the way they saw their world, or world schema, while others felt their illness experience just reinforced the way they had already experienced the world. Frank was able to reprioritize what was important to him after his diagnosis and accept his own mortality: “I might as well chill out, no more stress, and just enjoy things ’cause you could die…” For Henry, getting HF was only part of the experience of systemic oppression that had impacted his and his family’s lives for generations. He saw how his oppression by the military and US government led to his father’s exposure to chemicals that Henry believed he inherited and caused his illness. Henry’s illness experience reinforced his distrust in the institutions that were oppressed him and his family.

Veteran Status

Being a veteran in the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) system impacted how a narrative understanding of illness was created. Veterans are a unique cultural population with aspects of their illness experience that are important to understand.10 Institutions such as the VA also enable and constrain components of narrative creation.20 The illness narratives in this study were cocreated within the institutional setting of the VA. Part of the analysis included exploring how the institutional setting impacted the narrative creation. Emergent subthemes of the uniqueness of the veteran experience include financial benefits, intersectionality of government and health care, intersectionality of masculinity and military service, and the dichotomy of military experience.

In the US it is unique to the VA that the government both treats and assesses the severity of medical conditions to determine eligibility for health care and financial benefits. The VA’s financial benefits are intended to help compensate veterans who are experiencing illness as a result of their military experience.21 However, because the VA administers them the Veterans Benefits Administration and the VHA, veterans see both as interconnected. The perceived tie between illness severity and financial compensation could influence or bias how veterans understand their illness severity and experience. This may inadvertently encourage veterans to see their illness as being tied to their military service. This shaping of narratives should be considered as a contextual component as veterans obtain financial compensation and health insurance from the same larger organization that provides their health care and management.

George was a young man who during his service had chest pains and felt tired during physical training. He was surprised when his cardiologist explained his heart was enlarged. “All I know is when I initially joined the military, I was perfectly fine, you know, and when I was in the military, graduating, all that stuff, there was a glitch on the [electrocardiogram] they gave me after one day of doing [physical training] and then they’re like, oh, that’s fine. Come to find out it was mitral valve prolapse. And the doctors didn’t catch it then.” George feels the stress of the military caused his heart problems: “It wasn’t there before… so I’d have to say the strain from the military had to have caused it.” George’s medical history noted that he has a genetic connective tissue disorder that can lead to HF and likely was underlying cause of his illness. This example of how George pruned his narrative experience to highlight the cause as his military experience instead of a genetic disorder could have multiple financial and health benefits. The financial incentive for George to see his illness as caused by his military service could potentially bias his illness narrative to find his illness cause as tied to his service.

Government/Health Care Intersectionality

Veterans who may have experienced trust-breaking events with the government, like Agent Orange exposure or intergenerational racial trauma, may apply that experience to all government agencies. Bob felt the government had purposefully used him to create a military weapon. The army “knew I was angry and they used that for their advantage,” he said. Bob learned that he was exposed to Agent Orange in Vietnam, which is presumed to be associated with HF. Bob felt betrayed that the VHA had not figured out his health problems earlier. “I didn’t know anything about it until 6 months ago… Our government knew about it when they used it, and they didn’t care. They just wanted to win the war, and a whole lot of GIs like me suffered because of that, and I was like my government killed me? And I was fighting for them?”

Henry learned to distrust the government and the health care system because of a long history of systematic oppression and exploitation. These institutions’ erosion of trust has impact beyond the trust-breaking event itself but reverberates into how communities view organizations and institutions for generations. For Black Americans, who have historically been experimented on without consent by the US government and health care systems, this can make it especially hard to trust and build working relationships with those institutions. Health care professionals (HCPs) need to build collaborative partnerships with patients to provide effective care while understanding why some patients may have difficulty trusting health care systems, especially government-led systems.

The nature of HF as an illness can also make it difficult to predict and manage.22 This uncertainty and difficulty in managing HF can make it especially hard for people to establish trust with their HCPs whom they want to see as experts in their illness. HCPs in these narratives were often portrayed as incompetent or neglectful. The unpredictable nature of the illness itself was not reflected in the narrator’s experience.

Masculinity/Military Service Intersectionality

For the veteran narrators, tied into the identity of being a provider are social messages about masculinity. There is a unique intersectionality of being a man, the military culture, and living with chronic illnesses. Dominant social messages around being a man include being tough, not expressing emotion, self-reliance, and having power. This overlaps with social messages on military culture, including self-reliance, toughness, persistence in the face of adversity, limited expression of emotions, and the recognition of power and respect.23

People who internalize these social messages on masculinity may be less likely to access mental health treatment.23 This stigmatizing barrier to mental health treatment could impact how positive narratives are constructed around the experience of chronic illness for narrators who identify as masculine. Military and masculine identity could exclude or constrain stories about a veteran who did not “solider on” or who had to rely on others in a team to get things done. This shift can especially impact veterans experiencing chronic illnesses like HF, which often impact their physical abilities. Veterans may feel pressured to think of and portray themselves as being strong by limiting their expression of pain and other symptoms to remain in alignment with the dominant narrative. By not being open about the full experience of their illness both positive and negative, veterans may have unaddressed aspects of their illness experience or HCPs may not be able have all the information they need before the concern becomes a more serious health problem.

Dichotomy of Military Experience

Some narrators in this study talked about their military experience as both traumatic and beneficial. These dichotomous viewpoints can be difficult for veterans to construct a narrative understanding around. How can an inherently painful potentially traumatic experience, such as war, have benefits? This way of looking at the world may require a large narrative shift in their world and self-schemas to accept.

Bob hurt people in Vietnam as part of his job. “I did a lot of killing.” Bob met a village elder who stopped him from hurting people in the village and “in my spare time, I would go back to the village and he would teach me, how to be a better man,” Bob shared. “He taught me about life and everything, and he was awesome, just to this day, he’s like a father to me.” Bob tried to change his life and learned how to live a life full of love and care because of his experience in Vietnam. Though Bob hurt a lot of people in Vietnam, which still haunts him, he found meaning through his life lessons from the village elder. “I’m ashamed of what I did in Vietnam. I did some really bad stuff, but ever since then, I’ve always tried to do good to help people.”

Discussion

Exploring a person’s illness experience from a truly holistic pathway allows HCPs to see how the ripples of illness echo into the interconnection of surrounding systems and even across time. These stories suggest that veterans may experience their illness and construct their illness narratives based on the distinct contextual considerations of veteran culture.10 Research exploring how veterans see their illness and its potential impact on their health care access and choices could benefit from exploration into narrative understanding and meaning creation as a potentially contributing factor to health care decision making. As veterans are treated across health care systems, this has implications not only for VHA care, but community care as well.

These narratives also demonstrate how veterans create health care goals woven into their narrative understanding of their illness and its cause, lending insight into understanding health care decision making. This change in self-schema shapes how veterans see themselves and their role which shapes other aspects of their health care. These findings also contribute to our understanding of meaning creation. By exploring meaning making and narrative understanding, this work adds to our knowledge of the importance of spirituality as a component of the holistic experience of illness. There have been previous studies exploring the spiritual aspects of HF and the importance of meaning making.24,25 Exploring meaning making as an aspect of illness narratives can have important implications. Future research could explore the connections between meaning creation and illness narratives.

Limitations

The sample of veterans who participated in this study and are not generalizable to all veteran populations. The sample also only reflects people who were willing to participate and may exclude experience of people who may not have felt comfortable talking to a VA employee about their experience. It is also important to note that the small sample size included primarily male and White participants. In narrative inquiry, the number of participants is not as essential as diving into the depth of the interviews with the participants.

It is also important to note the position of the interviewer. As a White cisgender, heterosexual, middle-aged, middle class female who was raised in rural Kansas in a predominantly Protestant community, the positionality of the interviewer as a cocreator of the data inherently shaped and influenced the narratives created during this study. This contextual understanding of narratives created within the research relationship is an essential component to narrative inquiry and understanding.

Conclusions

Exploring these veterans’ narrative understanding of their experience of illness has many potential implications for health care systems, HCPs, and our military and veteran populations described in this article. Thinking about how the impact of racism, the influence of incentives to remain ill, and the complex intersection of identity and health brings light to how these domains may influence how people see themselves and engage in health care. These domains from these stories of the heart may help millions of people living with chronic illnesses like HF to not only live with their illness but inform how their experience is shaped by the systems surrounding them, including health care, government, and systems of power and oppression.

Heart failure (HF) is a costly and burdensome illness and is the top reason for hospital admissions for the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) and Medicare.1 The cost of HF to the United States is estimated to grow to $3 billion annually by 2030.2 People living with HF have a high symptom burden and poor quality of life.3,4 Symptoms include shortness of breath, fatigue, depression, and decreases in psychosocial, existential, and spiritual well-being.5-9

Veterans in the US are a unique cultural group with distinct contextual considerations around their experiences.10 Different groups of veterans require unique cultural considerations, such as the experiences of veterans who served during the Vietnam war and during Operation Iraqi Freedom/Operation Enduring Freedom (OIF/OEF). The extent of unmet needs of people living with HF, the number of veterans living with this illness, and the unique contextual components related to living with HF among veterans require further exploration into this illness experience for this distinct population. Research should explore innovative ways of managing both the number of people living with the illness and the significant impact of HF in people’s lives due to the high symptom burden and poor quality of life.3

This study used the model of adjustment to illness to explore the psychosocial adjustment to illness and the experience of US veterans living with HF, with a focus on the domains of meaning creation, self-schema, and world schema.11 The model of adjustment to illness describes how people learn to adjust to living with an illness, which can lead to positive health outcomes. Meaning creation is defined as the process in which people create meaning from their experience living with illness. Self-schema is how people living with illness see themselves, and world schema is how people living with chronic illness see their place in the world. These domains shift as part of the adjustment to living with an illness described in this model.11 This foundation allowed the investigators to explore the experience of living with HF among veterans with a focus on these domains. Our study aimed to cocreate illness narratives among veterans living with HF and to explore components of psychosocial adjustment informed by the model.

Methods

This study used narrative inquiry with a focus on illness narratives.12-17 Narrative inquiry as defined by Catherine Riessman involves the generation of socially constructed and cocreated meanings between the researcher and narrator. The researcher is an active participant in narrative creation as the narrator chooses which events to include in the stories based on the social, historical, and cultural context of both the narrator (study participant) and audience (researcher). Riessman describes the importance of contextual factors and meaning creation as an important aspect of narrative inquiry.12-14,16,17 It is important in narrative inquiry to consider how cultural, social, and historical factors influence narrative creation, constriction, and/or elimination.

This study prospectively created and collected data at a single time point. Semi-structured interviews explored psychosocial adjustment for people living with HF using an opening question modified from previous illness narrative research: Why do you think you got heart failure?18 Probes included the domains of psychosocial adjustment informed by the model of adjustment to illness domains (Figure). Emergent probes were used to illicit additional data around psychosocial adjustment to illness. Data were created and collected in accordance with narrative inquiry during the cocreation of the illness narratives between the researcher and study participants. This interview guide was tested by the first author in preliminary work to prepare for this study.

Allowing for emergent probes and acknowledging the role of the researcher as audience is key to the cocreation of narratives using this methodological framework. Narrators shape their narrative with the audience in mind; they cocreate their narrative with their audience using this type of narrative inquiry.12,16 What the narrator chooses to include and exclude from their story provides a window into how they see themselves and their world.19 Audio recordings were used to capture data, allowing for the researcher to take contemporaneous notes exploring contextual considerations to the narrative cocreation process and to be used later in analysis. Analytic notes were completed during the interviews as well as later in analysis as part of the contextual reflection.

Setting

Research was conducted in the Rocky Mountain Regional VA Medical Center, Aurora, Colorado. Participants were recruited through the outpatient cardiology clinic where the interviews also took place. This study was approved through the Colorado Institutional Review Board and Rocky Mountain Regional VA Medical Center (IRB: 19-1064). Participants were identified by the treating cardiologist who was a part of the study team. Interested veterans were introduced to the first author who was stationed in an empty clinic room. The study cardiologist screened to ensure all participants were ≥ 18 years of age and had a diagnosis of HF for > 1 year. Persons with an impairment that could interfere with their ability to construct a narrative were also excluded.

Recruitment took place from October 2019 to January 2020. Three veterans refused participation. Five study participants provided informed consent and were enrolled and interviewed. All interviews were completed in the clinic at the time of consent per participant preference. One-hour long semi-structured interviews were conducted and audio recorded. A demographic form was administered at the end of each interview to capture contextual data. The researcher also kept a reflexive journal and audit trail.

Narrative Analysis

Riessman described general steps to conduct narrative analysis, including transcription, narrative clean-up, consideration of contextual factors, exploration of thematic threads, consideration of larger social narratives, and positioning.12 The first author read transcripts while listening to the audio recordings to ensure accuracy. With narrative clean-up each narrative was organized to cocreate overall meaning, changed to protect anonymity, and refined to only include the illness narrative. For example, if a narrator told a story about childhood and then later in the interview remembered another detail to add to their story, narrative clean-up reordered events to make cohesive sense of the story. Demographic, historical, cultural, and social contexts of both the narrator and audience were reflected on during analysis to explore how these components may have shaped and influenced cocreation. Context was also considered within the larger VA setting.

Emergent themes were explored for convergence, divergence, and points of tension within and across each narrative. Larger social narratives were also considered for their influence on possible inclusion/exclusion of experience, such as how gender identity may have influenced study participants’ descriptions of their roles in social systems. These themes and narratives were then shared with our team, and we worked through decision points during the analysis process and discussed interpretation of the data to reach consensus.

Results

Five veterans living with HF were recruited and consented to participate in the study. Demographics of the participants and first author are included in the Table. Five illness narratives were cocreated, entitled: Blame the Cheese: Frank’s Illness Narrative; Love is Love: Bob’s Illness Narrative; The Brighter Things in Life is My Family: George’s Illness Narrative; We Never Know When Our Time is Coming: Bill’s Illness Narrative; and A Dream Deferred: Henry’s Illness Narrative.

Each narrative was explored focusing on the domains of the model of adjustment to illness. An emergent theme was also identified with multiple subthemes: being a veteran is unique. Related subthemes included: financial benefits, intersectionality of government and health care, the intersectionality of masculinity and military service, and the dichotomy of military experience.

The search for meaning creation after the experience of chronic illness emerged across interviews. One example of meaning creation was in Frank's illness narrative. Frank was unsure why he got HF: “Probably because I ate too much cheese…I mean, that’s gotta be it. It can’t be anything else.” By tying HF to his diet, he found meaning through his health behaviors.

Model of Adjustment to Illness

The narratives illustrate components of the model of adjustment to illness and describe how each of the participants either shifted their self-schema and world schema or reinforced their previously established schemas. It also demonstrates how people use narratives to create meaning and illness understanding from their illness experience, reflecting, and emphasizing different parts creating meaning from their experience.

A commonality across the narratives was a shift in self-schema, including the shift from being a provider to being reliant on others. In accordance with the dominant social narrative around men as providers, each narrator talked about their identity as a provider for themselves and their families. Often keeping their provider identity required modifications of the definition, from physical abilities and employment to financial security and stability. George made all his health care decisions based on his goal of providing for his family and protecting them from having to care for him: “I’m always thinking about the future, always trying to figure out how my family, if something should happen to me, how my family would cope, and how my family would be able to support themselves.” Bob’s health care goals were to stay alive long enough for his wife to get financial benefits as a surviving spouse: “That’s why I’m trying to make everything for her, you know. I’m not worried about myself. I’m not. Her I am, you know. And love is love.” Both of their health care decisions are shaped by their identity as a provider shifting to financial support.

Some narrators changed the way they saw their world, or world schema, while others felt their illness experience just reinforced the way they had already experienced the world. Frank was able to reprioritize what was important to him after his diagnosis and accept his own mortality: “I might as well chill out, no more stress, and just enjoy things ’cause you could die…” For Henry, getting HF was only part of the experience of systemic oppression that had impacted his and his family’s lives for generations. He saw how his oppression by the military and US government led to his father’s exposure to chemicals that Henry believed he inherited and caused his illness. Henry’s illness experience reinforced his distrust in the institutions that were oppressed him and his family.

Veteran Status

Being a veteran in the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) system impacted how a narrative understanding of illness was created. Veterans are a unique cultural population with aspects of their illness experience that are important to understand.10 Institutions such as the VA also enable and constrain components of narrative creation.20 The illness narratives in this study were cocreated within the institutional setting of the VA. Part of the analysis included exploring how the institutional setting impacted the narrative creation. Emergent subthemes of the uniqueness of the veteran experience include financial benefits, intersectionality of government and health care, intersectionality of masculinity and military service, and the dichotomy of military experience.

In the US it is unique to the VA that the government both treats and assesses the severity of medical conditions to determine eligibility for health care and financial benefits. The VA’s financial benefits are intended to help compensate veterans who are experiencing illness as a result of their military experience.21 However, because the VA administers them the Veterans Benefits Administration and the VHA, veterans see both as interconnected. The perceived tie between illness severity and financial compensation could influence or bias how veterans understand their illness severity and experience. This may inadvertently encourage veterans to see their illness as being tied to their military service. This shaping of narratives should be considered as a contextual component as veterans obtain financial compensation and health insurance from the same larger organization that provides their health care and management.

George was a young man who during his service had chest pains and felt tired during physical training. He was surprised when his cardiologist explained his heart was enlarged. “All I know is when I initially joined the military, I was perfectly fine, you know, and when I was in the military, graduating, all that stuff, there was a glitch on the [electrocardiogram] they gave me after one day of doing [physical training] and then they’re like, oh, that’s fine. Come to find out it was mitral valve prolapse. And the doctors didn’t catch it then.” George feels the stress of the military caused his heart problems: “It wasn’t there before… so I’d have to say the strain from the military had to have caused it.” George’s medical history noted that he has a genetic connective tissue disorder that can lead to HF and likely was underlying cause of his illness. This example of how George pruned his narrative experience to highlight the cause as his military experience instead of a genetic disorder could have multiple financial and health benefits. The financial incentive for George to see his illness as caused by his military service could potentially bias his illness narrative to find his illness cause as tied to his service.

Government/Health Care Intersectionality

Veterans who may have experienced trust-breaking events with the government, like Agent Orange exposure or intergenerational racial trauma, may apply that experience to all government agencies. Bob felt the government had purposefully used him to create a military weapon. The army “knew I was angry and they used that for their advantage,” he said. Bob learned that he was exposed to Agent Orange in Vietnam, which is presumed to be associated with HF. Bob felt betrayed that the VHA had not figured out his health problems earlier. “I didn’t know anything about it until 6 months ago… Our government knew about it when they used it, and they didn’t care. They just wanted to win the war, and a whole lot of GIs like me suffered because of that, and I was like my government killed me? And I was fighting for them?”

Henry learned to distrust the government and the health care system because of a long history of systematic oppression and exploitation. These institutions’ erosion of trust has impact beyond the trust-breaking event itself but reverberates into how communities view organizations and institutions for generations. For Black Americans, who have historically been experimented on without consent by the US government and health care systems, this can make it especially hard to trust and build working relationships with those institutions. Health care professionals (HCPs) need to build collaborative partnerships with patients to provide effective care while understanding why some patients may have difficulty trusting health care systems, especially government-led systems.

The nature of HF as an illness can also make it difficult to predict and manage.22 This uncertainty and difficulty in managing HF can make it especially hard for people to establish trust with their HCPs whom they want to see as experts in their illness. HCPs in these narratives were often portrayed as incompetent or neglectful. The unpredictable nature of the illness itself was not reflected in the narrator’s experience.

Masculinity/Military Service Intersectionality

For the veteran narrators, tied into the identity of being a provider are social messages about masculinity. There is a unique intersectionality of being a man, the military culture, and living with chronic illnesses. Dominant social messages around being a man include being tough, not expressing emotion, self-reliance, and having power. This overlaps with social messages on military culture, including self-reliance, toughness, persistence in the face of adversity, limited expression of emotions, and the recognition of power and respect.23

People who internalize these social messages on masculinity may be less likely to access mental health treatment.23 This stigmatizing barrier to mental health treatment could impact how positive narratives are constructed around the experience of chronic illness for narrators who identify as masculine. Military and masculine identity could exclude or constrain stories about a veteran who did not “solider on” or who had to rely on others in a team to get things done. This shift can especially impact veterans experiencing chronic illnesses like HF, which often impact their physical abilities. Veterans may feel pressured to think of and portray themselves as being strong by limiting their expression of pain and other symptoms to remain in alignment with the dominant narrative. By not being open about the full experience of their illness both positive and negative, veterans may have unaddressed aspects of their illness experience or HCPs may not be able have all the information they need before the concern becomes a more serious health problem.

Dichotomy of Military Experience

Some narrators in this study talked about their military experience as both traumatic and beneficial. These dichotomous viewpoints can be difficult for veterans to construct a narrative understanding around. How can an inherently painful potentially traumatic experience, such as war, have benefits? This way of looking at the world may require a large narrative shift in their world and self-schemas to accept.

Bob hurt people in Vietnam as part of his job. “I did a lot of killing.” Bob met a village elder who stopped him from hurting people in the village and “in my spare time, I would go back to the village and he would teach me, how to be a better man,” Bob shared. “He taught me about life and everything, and he was awesome, just to this day, he’s like a father to me.” Bob tried to change his life and learned how to live a life full of love and care because of his experience in Vietnam. Though Bob hurt a lot of people in Vietnam, which still haunts him, he found meaning through his life lessons from the village elder. “I’m ashamed of what I did in Vietnam. I did some really bad stuff, but ever since then, I’ve always tried to do good to help people.”

Discussion

Exploring a person’s illness experience from a truly holistic pathway allows HCPs to see how the ripples of illness echo into the interconnection of surrounding systems and even across time. These stories suggest that veterans may experience their illness and construct their illness narratives based on the distinct contextual considerations of veteran culture.10 Research exploring how veterans see their illness and its potential impact on their health care access and choices could benefit from exploration into narrative understanding and meaning creation as a potentially contributing factor to health care decision making. As veterans are treated across health care systems, this has implications not only for VHA care, but community care as well.

These narratives also demonstrate how veterans create health care goals woven into their narrative understanding of their illness and its cause, lending insight into understanding health care decision making. This change in self-schema shapes how veterans see themselves and their role which shapes other aspects of their health care. These findings also contribute to our understanding of meaning creation. By exploring meaning making and narrative understanding, this work adds to our knowledge of the importance of spirituality as a component of the holistic experience of illness. There have been previous studies exploring the spiritual aspects of HF and the importance of meaning making.24,25 Exploring meaning making as an aspect of illness narratives can have important implications. Future research could explore the connections between meaning creation and illness narratives.

Limitations

The sample of veterans who participated in this study and are not generalizable to all veteran populations. The sample also only reflects people who were willing to participate and may exclude experience of people who may not have felt comfortable talking to a VA employee about their experience. It is also important to note that the small sample size included primarily male and White participants. In narrative inquiry, the number of participants is not as essential as diving into the depth of the interviews with the participants.

It is also important to note the position of the interviewer. As a White cisgender, heterosexual, middle-aged, middle class female who was raised in rural Kansas in a predominantly Protestant community, the positionality of the interviewer as a cocreator of the data inherently shaped and influenced the narratives created during this study. This contextual understanding of narratives created within the research relationship is an essential component to narrative inquiry and understanding.

Conclusions

Exploring these veterans’ narrative understanding of their experience of illness has many potential implications for health care systems, HCPs, and our military and veteran populations described in this article. Thinking about how the impact of racism, the influence of incentives to remain ill, and the complex intersection of identity and health brings light to how these domains may influence how people see themselves and engage in health care. These domains from these stories of the heart may help millions of people living with chronic illnesses like HF to not only live with their illness but inform how their experience is shaped by the systems surrounding them, including health care, government, and systems of power and oppression.

1. Ashton CM, Bozkurt B, Colucci WB, et al. Veterans Affairs quality enhancement research initiative in chronic heart failure. Medical care. 2000;38(6):I-26-I-37.

2. Writing Group Members, Mozaffarian D, Benjamin EJ, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics-2016 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2016;133(4):e38-e360. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000350

3. Blinderman CD, Homel P, Billings JA, Portenoy RK, Tennstedt SL. Symptom distress and quality of life in patients with advanced congestive heart failure. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2008;35(6):594-603. doi:10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2007.06.007

4. Zambroski CH. Qualitative analysis of living with heart failure. Heart Lung. 2003;32(1):32-40. doi:10.1067/mhl.2003.10

5. Walthall H, Jenkinson C, Boulton M. Living with breathlessness in chronic heart failure: a qualitative study. J Clin Nurs. 2017;26(13-14):2036-2044. doi:10.1111/jocn.13615

6. Francis GS, Greenberg BH, Hsu DT, et al. ACCF/AHA/ACP/HFSA/ISHLT 2010 clinical competence statement on management of patients with advanced heart failure and cardiac transplant: a report of the ACCF/AHA/ACP Task Force on Clinical Competence and Training. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;56(5):424-453. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2010.04.014

7. Rumsfeld JS, Havranek E, Masoudi FA, et al. Depressive symptoms are the strongest predictors of short-term declines in health status in patients with heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;42(10):1811-1817. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2003.07.013

8. Leeming A, Murray SA, Kendall M. The impact of advanced heart failure on social, psychological and existential aspects and personhood. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2014;13(2):162-167. doi:10.1177/1474515114520771

9. Bekelman DB, Havranek EP, Becker DM, et al. Symptoms, depression, and quality of life in patients with heart failure. J Card Fail. 2007;13(8):643-648. doi:10.1016/j.cardfail.2007.05.005

10. Weiss E, Coll JE. The influence of military culture and veteran worldviews on mental health treatment: practice implications for combat veteran help-seeking and wellness. Int J Health, Wellness Society. 2011;1(2):75-86. doi:10.18848/2156-8960/CGP/v01i02/41168

11. Sharpe L, Curran L. Understanding the process of adjustment to illness. Soc Sci Med. 2006;62(5):1153-1166. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.07.010

12. Riessman CK. Narrative Methods for the Human Sciences. SAGE Publications; 2008.

13. Riessman CK. Performing identities in illness narrative: masculinity and multiple sclerosis. Qualitative Research. 2003;3(1):5-33. doi:10.1177/146879410300300101

14. Riessman CK. Strategic uses of narrative in the presentation of self and illness: a research note. Soc Sci Med. 1990;30(11):1195-1200. doi:10.1016/0277-9536(90)90259-U

15. Riessman CK. Analysis of personal narratives. In: Handbook of Interview Research. Sage; 2002:695-710.

16. Riessman CK. Illness Narratives: Positioned Identities. Invited Annual Lecture. Cardiff University. May 2002. Accessed April 14 2022. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/241501264_Illness_Narratives_Positioned_Identities

17. Riessman CK. Performing identities in illness narrative: masculinity and multiple sclerosis. Qual Res. 2003;3(1):5-33. doi:10.1177/146879410300300101

18. Williams G. The genesis of chronic illness: narrative re‐construction. Sociol Health Illn. 1984;6(2):175-200. doi:10.1111/1467-9566.ep10778250

19. White M, Epston D. Narrative Means to Therapeutic Ends. WW Norton & Company; 1990.

20. Burchardt M. Illness Narratives as Theory and Method. SAGE Publications; 2020.

21. Sayer NA, Spoont M, Nelson D. Veterans seeking disability benefits for post-traumatic stress disorder: who applies and the self-reported meaning of disability compensation. Soc Sci Med. 2004;58(11):2133-2143. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2003.08.009

22. Winters CA. Heart failure: living with uncertainty. Prog Cardiovasc Nurs. 1999;14(3):85.

23. Plys E, Smith R, Jacobs ML. Masculinity and military culture in VA hospice and palliative care: a narrative review with clinical recommendations. J Palliat Care. 2020;35(2):120-126. doi:10.1177/0825859719851483

24. Johnson LS. Facilitating spiritual meaning‐making for the individual with a diagnosis of a terminal illness. Counseling and Values. 2003;47(3):230-240. doi:10.1002/j.2161-007X.2003.tb00269.x

25. Shahrbabaki PM, Nouhi E, Kazemi M, Ahmadi F. Defective support network: a major obstacle to coping for patients with heart failure: a qualitative study. Glob Health Action. 2016;9:30767. Published 2016 Apr 1. doi:10.3402/gha.v9.30767

1. Ashton CM, Bozkurt B, Colucci WB, et al. Veterans Affairs quality enhancement research initiative in chronic heart failure. Medical care. 2000;38(6):I-26-I-37.

2. Writing Group Members, Mozaffarian D, Benjamin EJ, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics-2016 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2016;133(4):e38-e360. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000350

3. Blinderman CD, Homel P, Billings JA, Portenoy RK, Tennstedt SL. Symptom distress and quality of life in patients with advanced congestive heart failure. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2008;35(6):594-603. doi:10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2007.06.007

4. Zambroski CH. Qualitative analysis of living with heart failure. Heart Lung. 2003;32(1):32-40. doi:10.1067/mhl.2003.10

5. Walthall H, Jenkinson C, Boulton M. Living with breathlessness in chronic heart failure: a qualitative study. J Clin Nurs. 2017;26(13-14):2036-2044. doi:10.1111/jocn.13615

6. Francis GS, Greenberg BH, Hsu DT, et al. ACCF/AHA/ACP/HFSA/ISHLT 2010 clinical competence statement on management of patients with advanced heart failure and cardiac transplant: a report of the ACCF/AHA/ACP Task Force on Clinical Competence and Training. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;56(5):424-453. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2010.04.014

7. Rumsfeld JS, Havranek E, Masoudi FA, et al. Depressive symptoms are the strongest predictors of short-term declines in health status in patients with heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;42(10):1811-1817. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2003.07.013

8. Leeming A, Murray SA, Kendall M. The impact of advanced heart failure on social, psychological and existential aspects and personhood. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2014;13(2):162-167. doi:10.1177/1474515114520771

9. Bekelman DB, Havranek EP, Becker DM, et al. Symptoms, depression, and quality of life in patients with heart failure. J Card Fail. 2007;13(8):643-648. doi:10.1016/j.cardfail.2007.05.005

10. Weiss E, Coll JE. The influence of military culture and veteran worldviews on mental health treatment: practice implications for combat veteran help-seeking and wellness. Int J Health, Wellness Society. 2011;1(2):75-86. doi:10.18848/2156-8960/CGP/v01i02/41168

11. Sharpe L, Curran L. Understanding the process of adjustment to illness. Soc Sci Med. 2006;62(5):1153-1166. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.07.010

12. Riessman CK. Narrative Methods for the Human Sciences. SAGE Publications; 2008.

13. Riessman CK. Performing identities in illness narrative: masculinity and multiple sclerosis. Qualitative Research. 2003;3(1):5-33. doi:10.1177/146879410300300101

14. Riessman CK. Strategic uses of narrative in the presentation of self and illness: a research note. Soc Sci Med. 1990;30(11):1195-1200. doi:10.1016/0277-9536(90)90259-U