User login

Honor thy parents? Understanding parricide and associated spree killings

Mr. B, age 37, presents to a community mental health center for an appointment following a recent emergency department visit. He is diagnosed with schizophrenia, and has been treated for approximately 1 year. Six months ago, Mr. B stopped taking his antipsychotic due to its adverse effects. Despite compliance with another agent, he has become increasingly disorganized and paranoid.

He now believes that his mother, with whom he has lived all his life and who serves as his guardian, is poisoning his food and trying to kill him. She is an employee at a local grocery store, and Mr. B has expressed concern that her coworkers are assisting her in the plot to kill him.

Following a home visit, Mr. B’s case manager indicates that the patient showed them the collection of weapons he is amassing to “defend” himself. This leads to a concern for the safety of the patient, his mother, and others.

Although parricide—killing one’s parent—is a relatively rare event, its sensationalistic nature has long captured the attention of headline writers and the general public. This article discusses the diagnostic and demographic factors that may be seen among individuals who kill their parents, with an emphasis on those who commit matricide (murder of one’s mother) and associated spree killings, where an individual kills multiple people within a single brief but contiguous time period. Understanding these characteristics can help clinicians identify and more safely manage patients who may be at risk of harming their parents in addition to others.

Characteristics of perpetrators of parricide

Worldwide, approximately 2% to 4% of homicides involve parricide, or killing one’s parent.1,2 Most offenders are men in early adulthood, though a proportion are adolescents and some are women.1,3 They are often single, unemployed, and live with the parent prior to the killing.1 Patricide occurs more frequently than matricide.4 In the United States, approximately 150 fathers and 100 mothers are killed by their child each year.5

In a study of all homicides in England and Wales between 1997 and 2014, two-thirds of parricide offenders had previously been diagnosed with a mental disorder.1 One-third were diagnosed with schizophrenia.1 In a Canadian study focusing on 43 adult perpetrators found not criminally responsible,6 most were experiencing psychotic symptoms at the time of parricide; symptoms of a personality disorder were the second-most prevalent symptoms. Similarly, Bourget et al4 studied Canadian coroner records for 64 parents killed by their children. Of the children involved in those parricides, 15% attempted suicide after the killing. Two-thirds of the male offenders evidenced delusional thinking, and/or excessive violence (overkill) was common. Some cases (16%) followed an argument, and some of those perpetrators were intoxicated or psychotic. From our clinical experience, when there are identifiable nonpsychotic triggers, they often can be small things such as an argument over food, smoking, or video games. Often, the perpetrator was financially dependent on their parents and were “trapped in a difficult/hostile/dependence/love relationship” with that parent.6 Adolescent males who kill their parents may not have psychosis7; however, they may be victims of longstanding serious abuse at the hands of their parents. These perpetrators often express relief rather than remorse after committing murder.

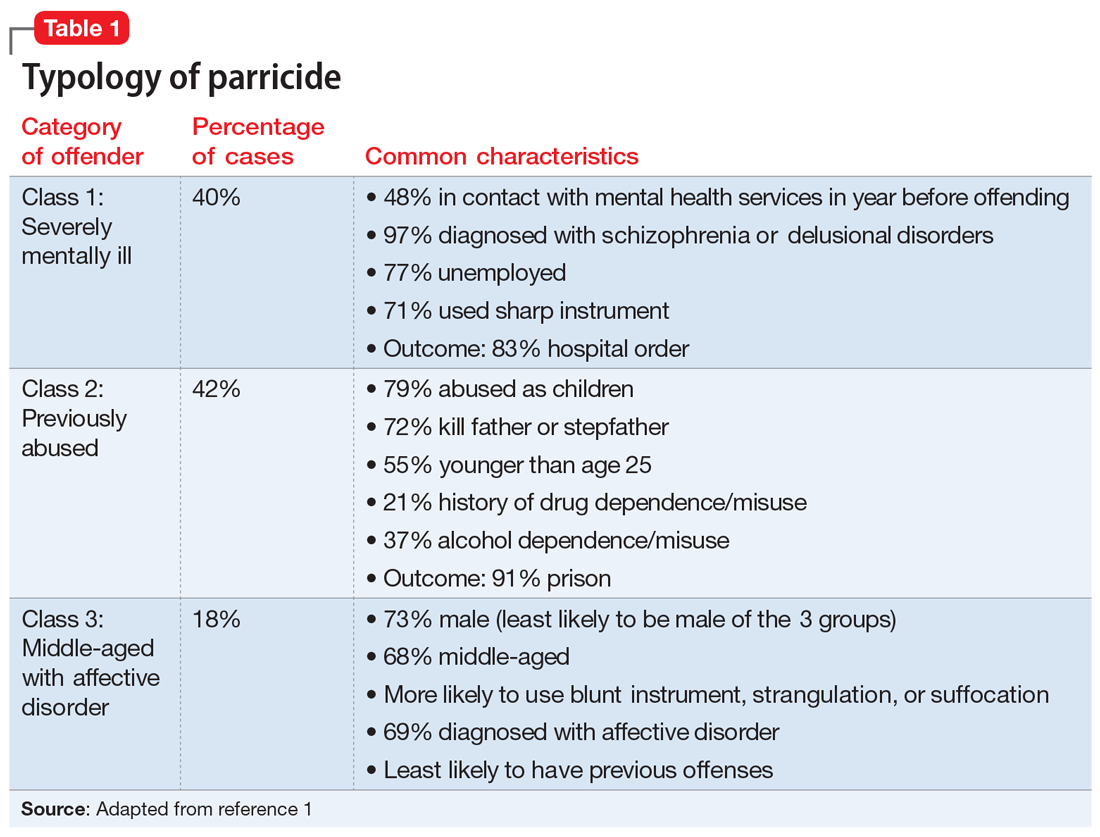

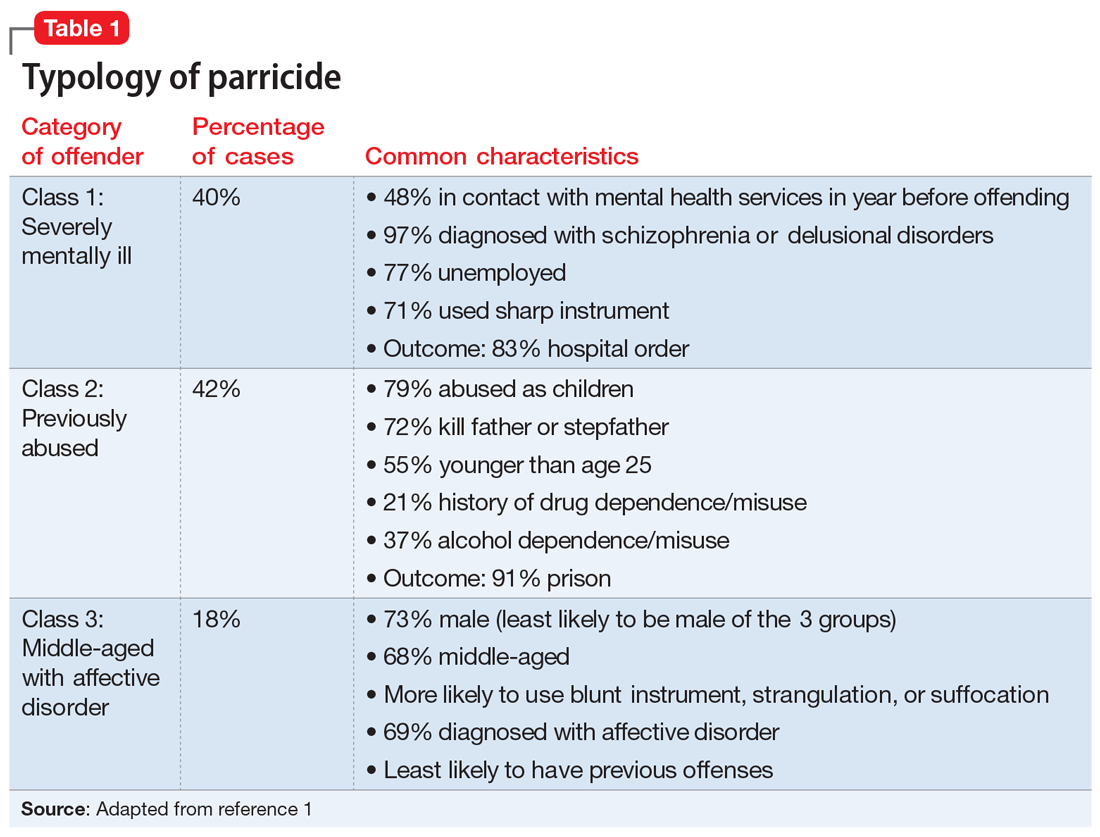

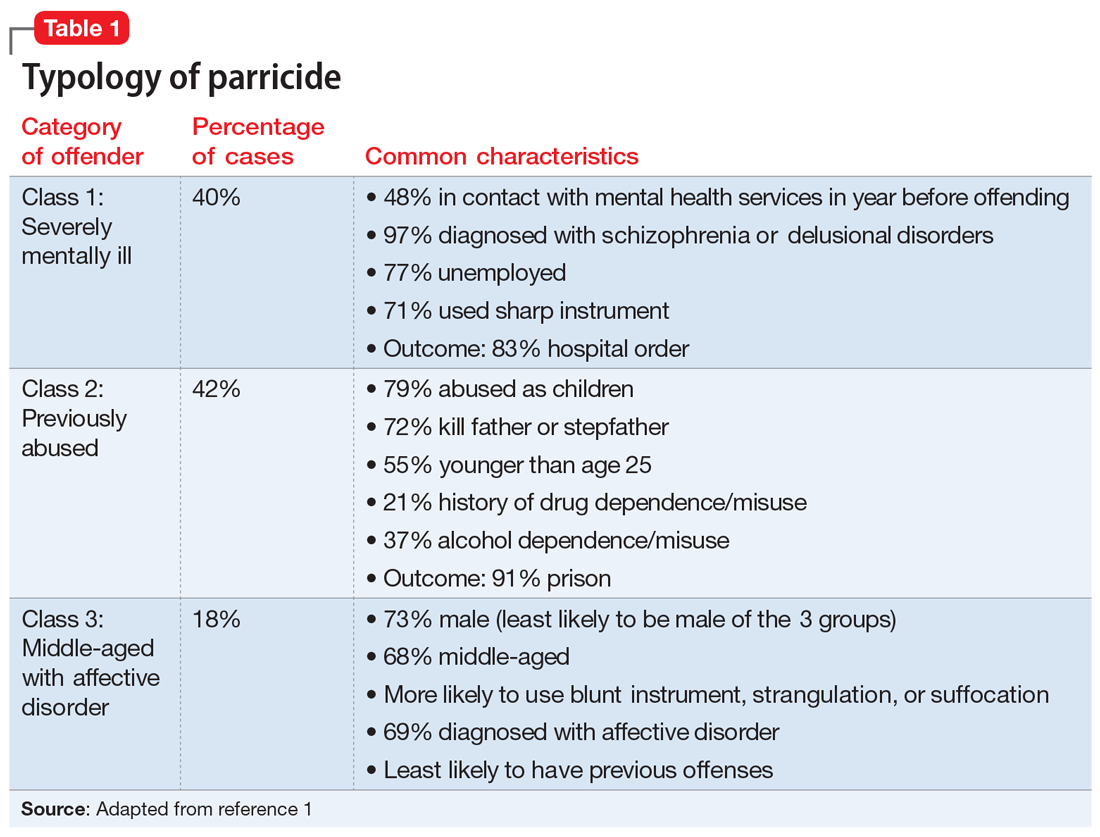

Three categories to classify the perpetrators of parricide have been proposed: severely abused, severely mentally ill, and “dangerously antisocial.”3 While severe mental illness was most common in adult defendants, severe abuse was most common in adolescent offenders. There may be significant commonalities between adolescent and adult perpetrators. A more recent latent class analysis by Bojanic et al1 indicated 3 unique types of parricide offenders (Table 1).

Continue to: Matricide: A closer look...

Matricide: A closer look

Though multiple studies have found a higher rate of psychosis among perpetrators of matricide, it is important to note that most people with psychotic disorders would never kill their mother. These events, however, tend to grab headlines and may be highly focused upon by the general population. In addition, matricide may be part of a larger crime that draws additional attention. For example, the 1966 University of Texas Bell Tower shooter and the 2012 Sandy Hook Elementary school shooter both killed their mothers before engaging in mass homicide. Often in cases of matricide, a longer-term dysfunctional relationship existed between the mother and the child. The mother is frequently described as controlling and intrusive and the (often adult) child as overly dependent, while the father may be absent or ineffectual. Hostility and mutual dependence are usual hallmarks of these relationships.8

However, in some cases where an individual with a psychotic disorder kills their mother, there may have been a traditional nurturing relationship.8 Alternative motivations unrelated to psychosis must be considered, including crimes motivated by money/inheritance or those perpetrated out of nonpsychotic anger. Green8 described motive categories for matricide that include paranoid and persecutory, altruistic, and other. In the “paranoid and persecutory” group, delusional beliefs about the mother occur; for example, the perpetrator may believe their mother was the devil. Sexual elements are found in some cases.8 Alternatively, the “altruistic” group demonstrated rather selfless reasons for killing, such as altruistic infanticide cases, or killing out of love.9 The altruistic matricide perpetrator may believe their mother is unwell, which may be a delusion or actually true. Finally, the “other” category contains cases related to jealousy, rage, and impulsivity.

In a study of 15 matricidal men in New York conducted by Campion et al,10 individuals seen by forensic psychiatric services for the crime of matricide included those with schizophrenia, substance-induced psychosis, and impulse control disorders. The authors noted there was often “a serious chronic derangement in the relationships of most matricidal men and their mothers.” Psychometric testing in these cases indicated feelings of dependency, weakness, and difficulty accepting an adult role separate from their mother. Some had conceptualized their mothers as a threat to their masculinity, while others had become enraged at their mothers.

Prevention requires addressing underlying issues

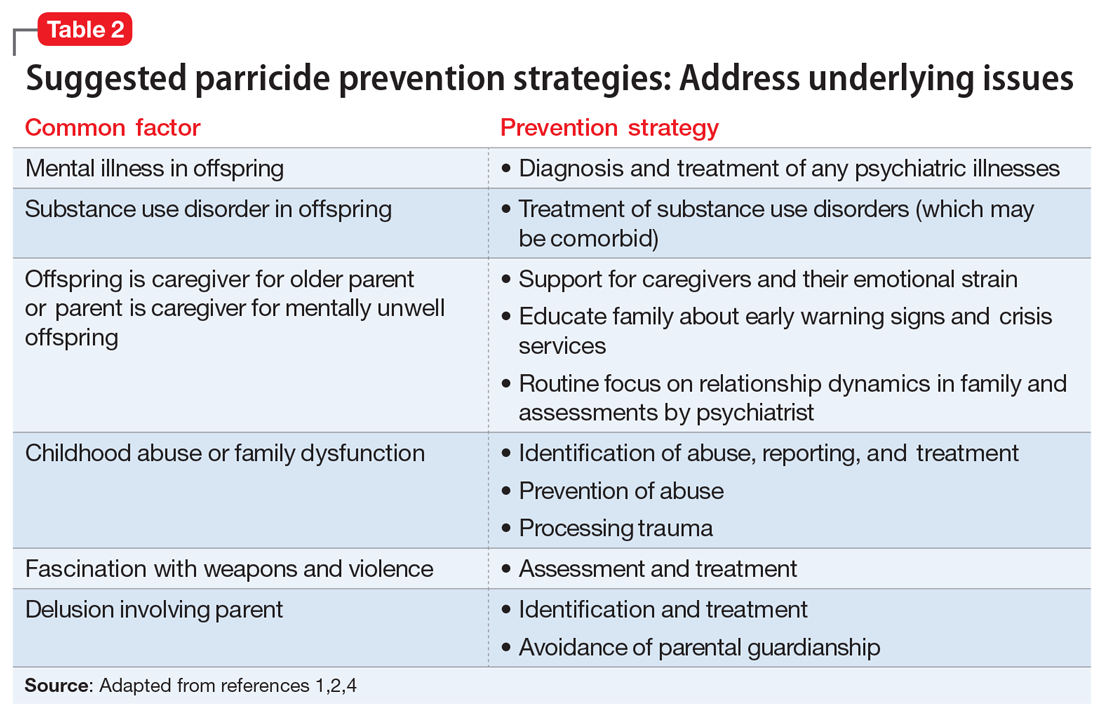

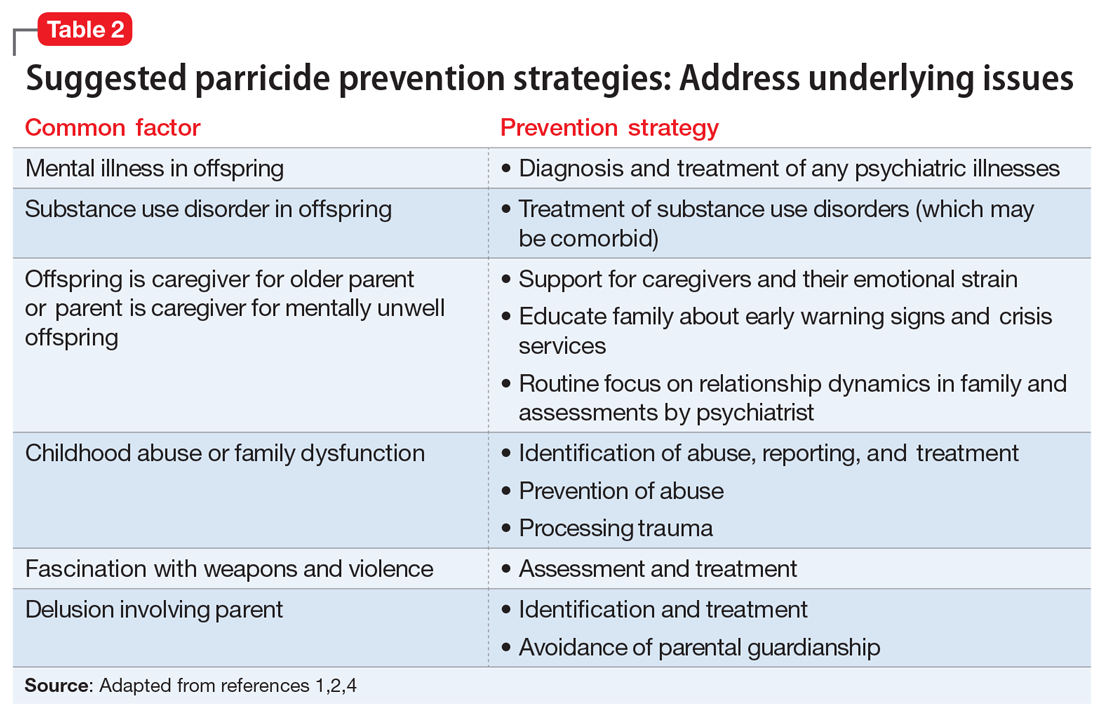

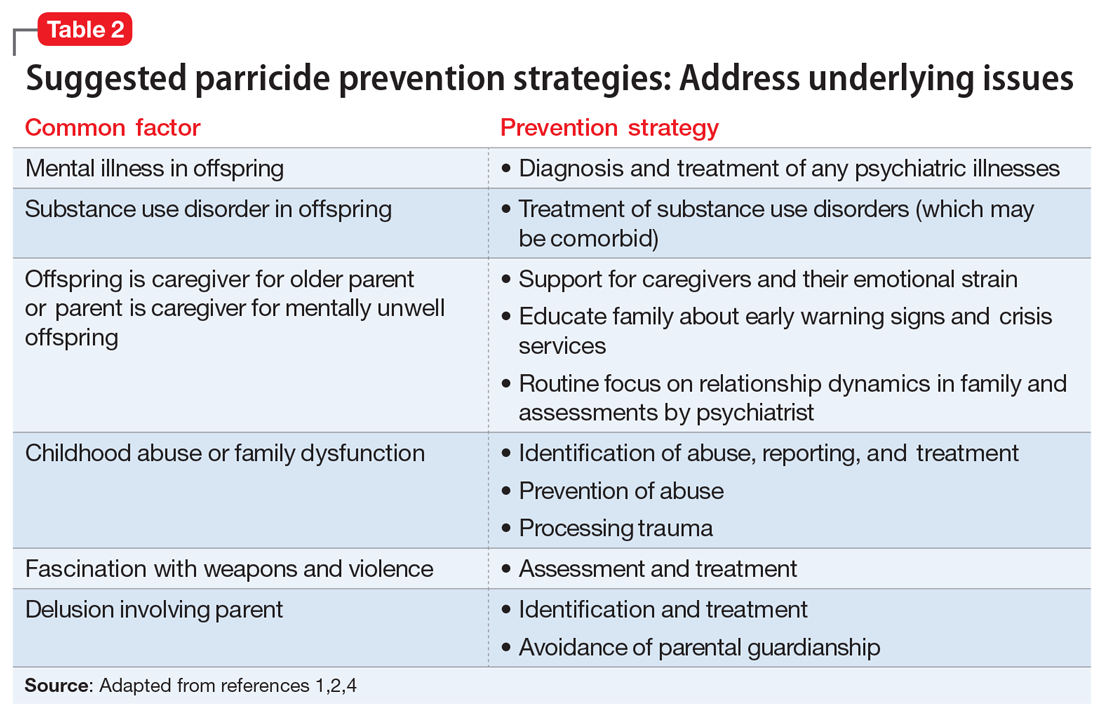

As described above, several factors are common among individuals who commit parricide, and these can be used to develop prevention strategies that focus on addressing underlying issues (Table 2). It is important to consider the relationship dynamics between the potential victim and perpetrator, as well as the motive, rather than focusing solely on mental illness or substance misuse.2

Spree killings that start as parricide

Although spree killing is a relatively rare event, a subset of spree killings involve parricide. One infamous recent event occurred in 2012 at Sandy Hook Elementary School, where the gunman killed his mother before going to the school and killing 26 additional people, many of whom were children.11,12 Because such events are rare, and because in these cases there is a high likelihood that the perpetrator is deceased (eg, died by suicide or killed by the police), much remains unknown about specific motivations and causative factors.

Information is often pieced together from postmortem reviews, which can be hampered by hindsight/recall bias and lack of contemporaneous documentation. Even worse, when these events occur, they may lead to a bias that all parricides or mass murders follow the pattern of the most recent case. This can result in overgeneralization of an individual’s history as being actionable risk violence factors for all potential parricide cases both by the public (eg, “My sister’s son has autism, and the Sandy Hook shooter was reported to have autism—should I be worried for my sister?”) and professionals (eg, “Will I be blamed for the next Sandy Hook by not taking more aggressive action even though I am not sure it is clinically warranted?”).

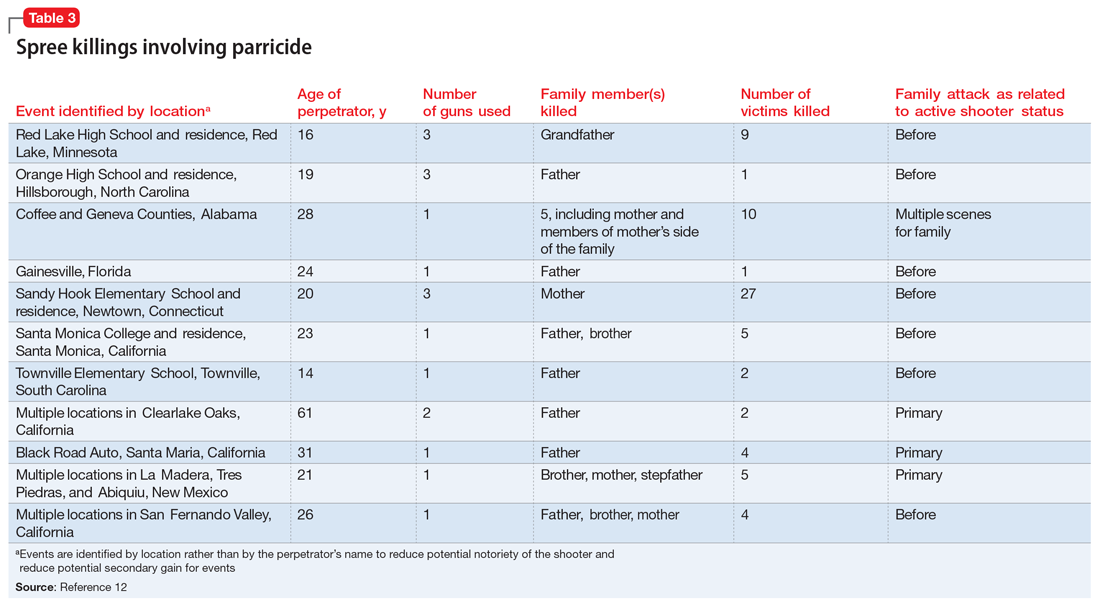

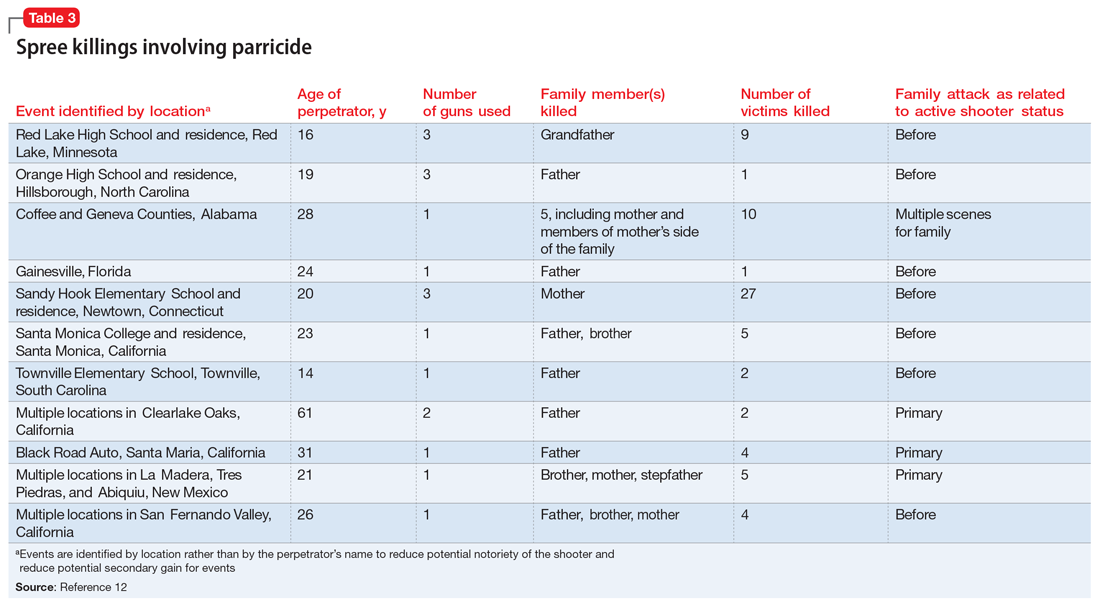

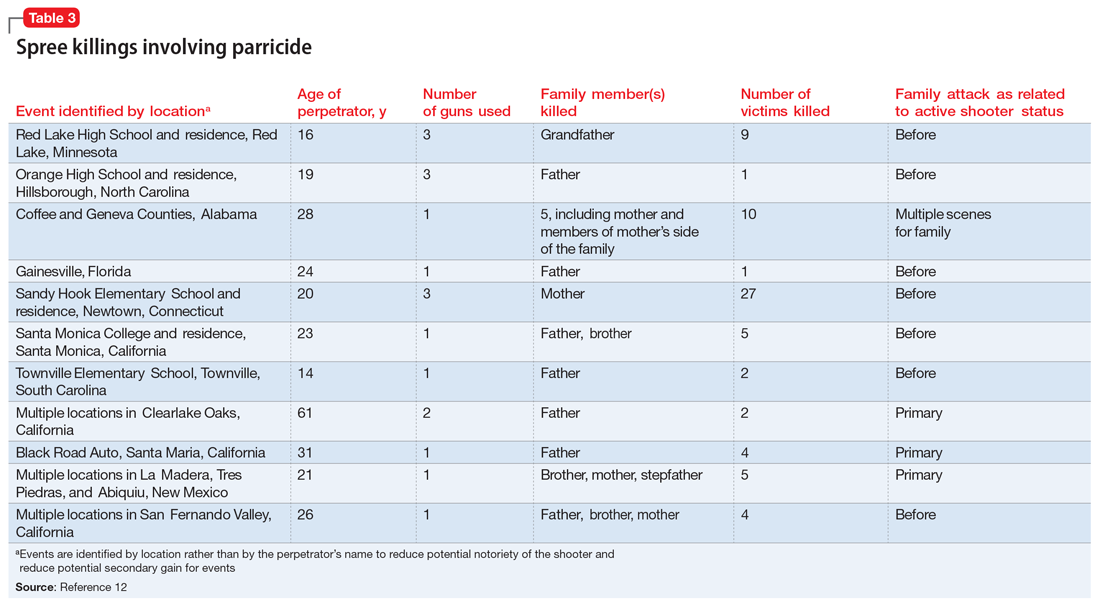

To identify trends for individuals committing parricide who engage in mass murder events (such as spree killing), we reviewed the 2000-2019 FBI active shooter list.12 Of the 333 events identified, 46 could be classified as domestic violence situations (eg, the perpetrator was in a romantic or familial relationship/former relationship and engaged in an active shooting incident involving at least 1 person from that relationship). We classified 11 of those 46 cases as parricide. Ten of those 11 parricides involved a child killing a parent (Table 3), and the other involved a grandchild killing a grandfather who served as their primary caregiver. Of the 11 incidents, mothers were involved (killed or wounded) in 4, and father figures (including the grandfather serving as a father and a stepfather) were killed in 9, with 2 incidents involving both parents. In 4 of the 11 parricides, other family members were killed in addition to the parent (including siblings, grandparents, or extended family). When considering spree shooters who committed parricide, 4 alleged perpetrators died by suicide, 1 was killed at the scene, and the rest were apprehended. The most common active shooting site endangering the public was an educational location (5), followed by commerce locations (4), with 2 involving open spaces. Eight of the 11 parricides occurred before the event was designated as an active shooting. The mean age for a parricide plus spree shooter was 23, once the oldest (age 61) and youngest (age 14) were removed from the calculation. The majority of the cases fell into the age range of 16 to 25 (n = 6), followed by 3 individuals who were age 26 to 31 (n = 3). All suspected individuals were male.

It is difficult to ascertain the existence of prior mental health care because perpetrators’ medical records may be confidential, juvenile court records may be sealed, and there may not even be a trial due to death or suicide (leading to limited forensic psychiatry examination or public testimony). Among those apprehended, many individuals raise some form of mental health defense, but the validity of their diagnosis may be undermined by concerns of possible malingering, especially in cases where the individual did not have a history of psychiatric treatment prior to the event.11 In summary, based on FBI data,12 spree shooters who committed parricide were usually male, in their late adolescence or early 20s, and more frequently targeted father figures. They often committed the parricide first and at a different location from later “active” shootings. Police were usually not aware of the parricide until after the spree is over.

Continue to: Parricide and society...

Parricide and society

For centuries, mothers and fathers have been honored and revered. Therefore, it is not surprising that killing of one’s mother or father attracts a great deal of macabre interest. Examples of parricide are present throughout popular culture, in mythology, comic books, movies, and television. As all psychiatrists know, Oedipus killed his father and married his mother. Other popular culture examples include: Grant Morrison’s Arkham Asylum: A Serious House on Serious Earth, Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho, Oliver Stone’s Natural Born Killers, Peter Jackson’s Heavenly Creatures, The Affair drama series, and Star Wars: The Force Awakens.13,14

CASE CONTINUED

In Mr. B’s case, it is imperative for the treatment team to inquire about his history of violence, paying particular attention to prior violent acts towards his mother. His clinicians should consider hospitalization with the guardian’s consent if the danger appears imminent, especially considering the presence of weapons at home. They should attempt to stabilize Mr. B on effective, tolerable medications to ameliorate his psychosis, and to refer him for long-term psychotherapy to address difficult dynamic issues in the family relationship and encourage compliance with treatment. These steps may help avert a tragedy.

Bottom Line

Individuals who commit parricide often have a history of psychosis, a mood disorder, childhood abuse, and/or difficult relationship dynamics with the parent they kill. Some go on a spree killing in the community. Through careful consideration of individual risk factors, psychiatrists may help prevent some cases of parent murder by a child and possibly more tragedy in the community.

1. Bojanié L, Flynn S, Gianatsi M, et al. The typology of parricide and the role of mental illness: data-driven approach. Aggress Behav. 2020;46(6):516-522.

2. Pinals DS. Parricide. In Friedman SH, ed. Family Murder: Pathologies of Love and Hate. American Psychiatric Publishing; 2019:113-138.

3. Heide KM. Matricide and stepmatricide victims and offenders: an empirical analysis of US arrest data. Behav Sci Law. 2013;31(2):203-214.

4. Bourget D, Gagné P, Labelle ME. Parricide: a comparative study of matricide versus patricide. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2007;35(3):306-312.

5. Heide KM, Frei A. Matricide: a critique of the literature. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2010;11(1):3-17.

6. Marleau JD, Auclair N, Millaud F. Comparison of factors associated with parricide in adults and adolescents. J Fam Viol. 2006;21:321-325.

7. West SG, Feldsher M. Parricide: characteristics of sons and daughters who kill their parents. Current Psychiatry. 2010;9(11):20-38.

8. Green CM. Matricide by sons. Med Sci Law. 1981;21(3):207-214.

9. Friedman SH. Conclusions. In Friedman SH, ed. Family Murder: Pathologies of Love and Hate. American Psychiatric Publishing; 2019:161-164.

10. Campion J, Cravens JM, Rotholc A, et al. A study of 15 matricidal men. Am J Psychiatry. 1985;142(3):312-317.

11. Hall RCW, Friedman SH, Sorrentino R, et al. The myth of school shooters and psychotropic medications. Behav Sci Law. 2019;37(5):540-558.

12. Department of Justice Federal Bureau of Investigation. Active Shooter Incidents: 20-Year Review, 2000-2019. June 1, 2021. Accessed October 12, 2021. https://www.fbi.gov/file-repository/active-shooter-incidents-20-year-review-2000-2019-060121.pdf/view

13. Friedman SH, Hall RCW. Star Wars: The Force Awakens, forensic teaching about matricide. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2017;45(1):128-130.

14. Friedman SH, Hall RCW. Deadly and dysfunctional family dynamics: when fiction mirrors fact. In: Packer S, Fredrick DR, eds. Welcome to Arkham Asylum: Essays on Psychiatry and the Gotham City Institution. McFarland; 2019:65-75.

Mr. B, age 37, presents to a community mental health center for an appointment following a recent emergency department visit. He is diagnosed with schizophrenia, and has been treated for approximately 1 year. Six months ago, Mr. B stopped taking his antipsychotic due to its adverse effects. Despite compliance with another agent, he has become increasingly disorganized and paranoid.

He now believes that his mother, with whom he has lived all his life and who serves as his guardian, is poisoning his food and trying to kill him. She is an employee at a local grocery store, and Mr. B has expressed concern that her coworkers are assisting her in the plot to kill him.

Following a home visit, Mr. B’s case manager indicates that the patient showed them the collection of weapons he is amassing to “defend” himself. This leads to a concern for the safety of the patient, his mother, and others.

Although parricide—killing one’s parent—is a relatively rare event, its sensationalistic nature has long captured the attention of headline writers and the general public. This article discusses the diagnostic and demographic factors that may be seen among individuals who kill their parents, with an emphasis on those who commit matricide (murder of one’s mother) and associated spree killings, where an individual kills multiple people within a single brief but contiguous time period. Understanding these characteristics can help clinicians identify and more safely manage patients who may be at risk of harming their parents in addition to others.

Characteristics of perpetrators of parricide

Worldwide, approximately 2% to 4% of homicides involve parricide, or killing one’s parent.1,2 Most offenders are men in early adulthood, though a proportion are adolescents and some are women.1,3 They are often single, unemployed, and live with the parent prior to the killing.1 Patricide occurs more frequently than matricide.4 In the United States, approximately 150 fathers and 100 mothers are killed by their child each year.5

In a study of all homicides in England and Wales between 1997 and 2014, two-thirds of parricide offenders had previously been diagnosed with a mental disorder.1 One-third were diagnosed with schizophrenia.1 In a Canadian study focusing on 43 adult perpetrators found not criminally responsible,6 most were experiencing psychotic symptoms at the time of parricide; symptoms of a personality disorder were the second-most prevalent symptoms. Similarly, Bourget et al4 studied Canadian coroner records for 64 parents killed by their children. Of the children involved in those parricides, 15% attempted suicide after the killing. Two-thirds of the male offenders evidenced delusional thinking, and/or excessive violence (overkill) was common. Some cases (16%) followed an argument, and some of those perpetrators were intoxicated or psychotic. From our clinical experience, when there are identifiable nonpsychotic triggers, they often can be small things such as an argument over food, smoking, or video games. Often, the perpetrator was financially dependent on their parents and were “trapped in a difficult/hostile/dependence/love relationship” with that parent.6 Adolescent males who kill their parents may not have psychosis7; however, they may be victims of longstanding serious abuse at the hands of their parents. These perpetrators often express relief rather than remorse after committing murder.

Three categories to classify the perpetrators of parricide have been proposed: severely abused, severely mentally ill, and “dangerously antisocial.”3 While severe mental illness was most common in adult defendants, severe abuse was most common in adolescent offenders. There may be significant commonalities between adolescent and adult perpetrators. A more recent latent class analysis by Bojanic et al1 indicated 3 unique types of parricide offenders (Table 1).

Continue to: Matricide: A closer look...

Matricide: A closer look

Though multiple studies have found a higher rate of psychosis among perpetrators of matricide, it is important to note that most people with psychotic disorders would never kill their mother. These events, however, tend to grab headlines and may be highly focused upon by the general population. In addition, matricide may be part of a larger crime that draws additional attention. For example, the 1966 University of Texas Bell Tower shooter and the 2012 Sandy Hook Elementary school shooter both killed their mothers before engaging in mass homicide. Often in cases of matricide, a longer-term dysfunctional relationship existed between the mother and the child. The mother is frequently described as controlling and intrusive and the (often adult) child as overly dependent, while the father may be absent or ineffectual. Hostility and mutual dependence are usual hallmarks of these relationships.8

However, in some cases where an individual with a psychotic disorder kills their mother, there may have been a traditional nurturing relationship.8 Alternative motivations unrelated to psychosis must be considered, including crimes motivated by money/inheritance or those perpetrated out of nonpsychotic anger. Green8 described motive categories for matricide that include paranoid and persecutory, altruistic, and other. In the “paranoid and persecutory” group, delusional beliefs about the mother occur; for example, the perpetrator may believe their mother was the devil. Sexual elements are found in some cases.8 Alternatively, the “altruistic” group demonstrated rather selfless reasons for killing, such as altruistic infanticide cases, or killing out of love.9 The altruistic matricide perpetrator may believe their mother is unwell, which may be a delusion or actually true. Finally, the “other” category contains cases related to jealousy, rage, and impulsivity.

In a study of 15 matricidal men in New York conducted by Campion et al,10 individuals seen by forensic psychiatric services for the crime of matricide included those with schizophrenia, substance-induced psychosis, and impulse control disorders. The authors noted there was often “a serious chronic derangement in the relationships of most matricidal men and their mothers.” Psychometric testing in these cases indicated feelings of dependency, weakness, and difficulty accepting an adult role separate from their mother. Some had conceptualized their mothers as a threat to their masculinity, while others had become enraged at their mothers.

Prevention requires addressing underlying issues

As described above, several factors are common among individuals who commit parricide, and these can be used to develop prevention strategies that focus on addressing underlying issues (Table 2). It is important to consider the relationship dynamics between the potential victim and perpetrator, as well as the motive, rather than focusing solely on mental illness or substance misuse.2

Spree killings that start as parricide

Although spree killing is a relatively rare event, a subset of spree killings involve parricide. One infamous recent event occurred in 2012 at Sandy Hook Elementary School, where the gunman killed his mother before going to the school and killing 26 additional people, many of whom were children.11,12 Because such events are rare, and because in these cases there is a high likelihood that the perpetrator is deceased (eg, died by suicide or killed by the police), much remains unknown about specific motivations and causative factors.

Information is often pieced together from postmortem reviews, which can be hampered by hindsight/recall bias and lack of contemporaneous documentation. Even worse, when these events occur, they may lead to a bias that all parricides or mass murders follow the pattern of the most recent case. This can result in overgeneralization of an individual’s history as being actionable risk violence factors for all potential parricide cases both by the public (eg, “My sister’s son has autism, and the Sandy Hook shooter was reported to have autism—should I be worried for my sister?”) and professionals (eg, “Will I be blamed for the next Sandy Hook by not taking more aggressive action even though I am not sure it is clinically warranted?”).

To identify trends for individuals committing parricide who engage in mass murder events (such as spree killing), we reviewed the 2000-2019 FBI active shooter list.12 Of the 333 events identified, 46 could be classified as domestic violence situations (eg, the perpetrator was in a romantic or familial relationship/former relationship and engaged in an active shooting incident involving at least 1 person from that relationship). We classified 11 of those 46 cases as parricide. Ten of those 11 parricides involved a child killing a parent (Table 3), and the other involved a grandchild killing a grandfather who served as their primary caregiver. Of the 11 incidents, mothers were involved (killed or wounded) in 4, and father figures (including the grandfather serving as a father and a stepfather) were killed in 9, with 2 incidents involving both parents. In 4 of the 11 parricides, other family members were killed in addition to the parent (including siblings, grandparents, or extended family). When considering spree shooters who committed parricide, 4 alleged perpetrators died by suicide, 1 was killed at the scene, and the rest were apprehended. The most common active shooting site endangering the public was an educational location (5), followed by commerce locations (4), with 2 involving open spaces. Eight of the 11 parricides occurred before the event was designated as an active shooting. The mean age for a parricide plus spree shooter was 23, once the oldest (age 61) and youngest (age 14) were removed from the calculation. The majority of the cases fell into the age range of 16 to 25 (n = 6), followed by 3 individuals who were age 26 to 31 (n = 3). All suspected individuals were male.

It is difficult to ascertain the existence of prior mental health care because perpetrators’ medical records may be confidential, juvenile court records may be sealed, and there may not even be a trial due to death or suicide (leading to limited forensic psychiatry examination or public testimony). Among those apprehended, many individuals raise some form of mental health defense, but the validity of their diagnosis may be undermined by concerns of possible malingering, especially in cases where the individual did not have a history of psychiatric treatment prior to the event.11 In summary, based on FBI data,12 spree shooters who committed parricide were usually male, in their late adolescence or early 20s, and more frequently targeted father figures. They often committed the parricide first and at a different location from later “active” shootings. Police were usually not aware of the parricide until after the spree is over.

Continue to: Parricide and society...

Parricide and society

For centuries, mothers and fathers have been honored and revered. Therefore, it is not surprising that killing of one’s mother or father attracts a great deal of macabre interest. Examples of parricide are present throughout popular culture, in mythology, comic books, movies, and television. As all psychiatrists know, Oedipus killed his father and married his mother. Other popular culture examples include: Grant Morrison’s Arkham Asylum: A Serious House on Serious Earth, Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho, Oliver Stone’s Natural Born Killers, Peter Jackson’s Heavenly Creatures, The Affair drama series, and Star Wars: The Force Awakens.13,14

CASE CONTINUED

In Mr. B’s case, it is imperative for the treatment team to inquire about his history of violence, paying particular attention to prior violent acts towards his mother. His clinicians should consider hospitalization with the guardian’s consent if the danger appears imminent, especially considering the presence of weapons at home. They should attempt to stabilize Mr. B on effective, tolerable medications to ameliorate his psychosis, and to refer him for long-term psychotherapy to address difficult dynamic issues in the family relationship and encourage compliance with treatment. These steps may help avert a tragedy.

Bottom Line

Individuals who commit parricide often have a history of psychosis, a mood disorder, childhood abuse, and/or difficult relationship dynamics with the parent they kill. Some go on a spree killing in the community. Through careful consideration of individual risk factors, psychiatrists may help prevent some cases of parent murder by a child and possibly more tragedy in the community.

Mr. B, age 37, presents to a community mental health center for an appointment following a recent emergency department visit. He is diagnosed with schizophrenia, and has been treated for approximately 1 year. Six months ago, Mr. B stopped taking his antipsychotic due to its adverse effects. Despite compliance with another agent, he has become increasingly disorganized and paranoid.

He now believes that his mother, with whom he has lived all his life and who serves as his guardian, is poisoning his food and trying to kill him. She is an employee at a local grocery store, and Mr. B has expressed concern that her coworkers are assisting her in the plot to kill him.

Following a home visit, Mr. B’s case manager indicates that the patient showed them the collection of weapons he is amassing to “defend” himself. This leads to a concern for the safety of the patient, his mother, and others.

Although parricide—killing one’s parent—is a relatively rare event, its sensationalistic nature has long captured the attention of headline writers and the general public. This article discusses the diagnostic and demographic factors that may be seen among individuals who kill their parents, with an emphasis on those who commit matricide (murder of one’s mother) and associated spree killings, where an individual kills multiple people within a single brief but contiguous time period. Understanding these characteristics can help clinicians identify and more safely manage patients who may be at risk of harming their parents in addition to others.

Characteristics of perpetrators of parricide

Worldwide, approximately 2% to 4% of homicides involve parricide, or killing one’s parent.1,2 Most offenders are men in early adulthood, though a proportion are adolescents and some are women.1,3 They are often single, unemployed, and live with the parent prior to the killing.1 Patricide occurs more frequently than matricide.4 In the United States, approximately 150 fathers and 100 mothers are killed by their child each year.5

In a study of all homicides in England and Wales between 1997 and 2014, two-thirds of parricide offenders had previously been diagnosed with a mental disorder.1 One-third were diagnosed with schizophrenia.1 In a Canadian study focusing on 43 adult perpetrators found not criminally responsible,6 most were experiencing psychotic symptoms at the time of parricide; symptoms of a personality disorder were the second-most prevalent symptoms. Similarly, Bourget et al4 studied Canadian coroner records for 64 parents killed by their children. Of the children involved in those parricides, 15% attempted suicide after the killing. Two-thirds of the male offenders evidenced delusional thinking, and/or excessive violence (overkill) was common. Some cases (16%) followed an argument, and some of those perpetrators were intoxicated or psychotic. From our clinical experience, when there are identifiable nonpsychotic triggers, they often can be small things such as an argument over food, smoking, or video games. Often, the perpetrator was financially dependent on their parents and were “trapped in a difficult/hostile/dependence/love relationship” with that parent.6 Adolescent males who kill their parents may not have psychosis7; however, they may be victims of longstanding serious abuse at the hands of their parents. These perpetrators often express relief rather than remorse after committing murder.

Three categories to classify the perpetrators of parricide have been proposed: severely abused, severely mentally ill, and “dangerously antisocial.”3 While severe mental illness was most common in adult defendants, severe abuse was most common in adolescent offenders. There may be significant commonalities between adolescent and adult perpetrators. A more recent latent class analysis by Bojanic et al1 indicated 3 unique types of parricide offenders (Table 1).

Continue to: Matricide: A closer look...

Matricide: A closer look

Though multiple studies have found a higher rate of psychosis among perpetrators of matricide, it is important to note that most people with psychotic disorders would never kill their mother. These events, however, tend to grab headlines and may be highly focused upon by the general population. In addition, matricide may be part of a larger crime that draws additional attention. For example, the 1966 University of Texas Bell Tower shooter and the 2012 Sandy Hook Elementary school shooter both killed their mothers before engaging in mass homicide. Often in cases of matricide, a longer-term dysfunctional relationship existed between the mother and the child. The mother is frequently described as controlling and intrusive and the (often adult) child as overly dependent, while the father may be absent or ineffectual. Hostility and mutual dependence are usual hallmarks of these relationships.8

However, in some cases where an individual with a psychotic disorder kills their mother, there may have been a traditional nurturing relationship.8 Alternative motivations unrelated to psychosis must be considered, including crimes motivated by money/inheritance or those perpetrated out of nonpsychotic anger. Green8 described motive categories for matricide that include paranoid and persecutory, altruistic, and other. In the “paranoid and persecutory” group, delusional beliefs about the mother occur; for example, the perpetrator may believe their mother was the devil. Sexual elements are found in some cases.8 Alternatively, the “altruistic” group demonstrated rather selfless reasons for killing, such as altruistic infanticide cases, or killing out of love.9 The altruistic matricide perpetrator may believe their mother is unwell, which may be a delusion or actually true. Finally, the “other” category contains cases related to jealousy, rage, and impulsivity.

In a study of 15 matricidal men in New York conducted by Campion et al,10 individuals seen by forensic psychiatric services for the crime of matricide included those with schizophrenia, substance-induced psychosis, and impulse control disorders. The authors noted there was often “a serious chronic derangement in the relationships of most matricidal men and their mothers.” Psychometric testing in these cases indicated feelings of dependency, weakness, and difficulty accepting an adult role separate from their mother. Some had conceptualized their mothers as a threat to their masculinity, while others had become enraged at their mothers.

Prevention requires addressing underlying issues

As described above, several factors are common among individuals who commit parricide, and these can be used to develop prevention strategies that focus on addressing underlying issues (Table 2). It is important to consider the relationship dynamics between the potential victim and perpetrator, as well as the motive, rather than focusing solely on mental illness or substance misuse.2

Spree killings that start as parricide

Although spree killing is a relatively rare event, a subset of spree killings involve parricide. One infamous recent event occurred in 2012 at Sandy Hook Elementary School, where the gunman killed his mother before going to the school and killing 26 additional people, many of whom were children.11,12 Because such events are rare, and because in these cases there is a high likelihood that the perpetrator is deceased (eg, died by suicide or killed by the police), much remains unknown about specific motivations and causative factors.

Information is often pieced together from postmortem reviews, which can be hampered by hindsight/recall bias and lack of contemporaneous documentation. Even worse, when these events occur, they may lead to a bias that all parricides or mass murders follow the pattern of the most recent case. This can result in overgeneralization of an individual’s history as being actionable risk violence factors for all potential parricide cases both by the public (eg, “My sister’s son has autism, and the Sandy Hook shooter was reported to have autism—should I be worried for my sister?”) and professionals (eg, “Will I be blamed for the next Sandy Hook by not taking more aggressive action even though I am not sure it is clinically warranted?”).

To identify trends for individuals committing parricide who engage in mass murder events (such as spree killing), we reviewed the 2000-2019 FBI active shooter list.12 Of the 333 events identified, 46 could be classified as domestic violence situations (eg, the perpetrator was in a romantic or familial relationship/former relationship and engaged in an active shooting incident involving at least 1 person from that relationship). We classified 11 of those 46 cases as parricide. Ten of those 11 parricides involved a child killing a parent (Table 3), and the other involved a grandchild killing a grandfather who served as their primary caregiver. Of the 11 incidents, mothers were involved (killed or wounded) in 4, and father figures (including the grandfather serving as a father and a stepfather) were killed in 9, with 2 incidents involving both parents. In 4 of the 11 parricides, other family members were killed in addition to the parent (including siblings, grandparents, or extended family). When considering spree shooters who committed parricide, 4 alleged perpetrators died by suicide, 1 was killed at the scene, and the rest were apprehended. The most common active shooting site endangering the public was an educational location (5), followed by commerce locations (4), with 2 involving open spaces. Eight of the 11 parricides occurred before the event was designated as an active shooting. The mean age for a parricide plus spree shooter was 23, once the oldest (age 61) and youngest (age 14) were removed from the calculation. The majority of the cases fell into the age range of 16 to 25 (n = 6), followed by 3 individuals who were age 26 to 31 (n = 3). All suspected individuals were male.

It is difficult to ascertain the existence of prior mental health care because perpetrators’ medical records may be confidential, juvenile court records may be sealed, and there may not even be a trial due to death or suicide (leading to limited forensic psychiatry examination or public testimony). Among those apprehended, many individuals raise some form of mental health defense, but the validity of their diagnosis may be undermined by concerns of possible malingering, especially in cases where the individual did not have a history of psychiatric treatment prior to the event.11 In summary, based on FBI data,12 spree shooters who committed parricide were usually male, in their late adolescence or early 20s, and more frequently targeted father figures. They often committed the parricide first and at a different location from later “active” shootings. Police were usually not aware of the parricide until after the spree is over.

Continue to: Parricide and society...

Parricide and society

For centuries, mothers and fathers have been honored and revered. Therefore, it is not surprising that killing of one’s mother or father attracts a great deal of macabre interest. Examples of parricide are present throughout popular culture, in mythology, comic books, movies, and television. As all psychiatrists know, Oedipus killed his father and married his mother. Other popular culture examples include: Grant Morrison’s Arkham Asylum: A Serious House on Serious Earth, Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho, Oliver Stone’s Natural Born Killers, Peter Jackson’s Heavenly Creatures, The Affair drama series, and Star Wars: The Force Awakens.13,14

CASE CONTINUED

In Mr. B’s case, it is imperative for the treatment team to inquire about his history of violence, paying particular attention to prior violent acts towards his mother. His clinicians should consider hospitalization with the guardian’s consent if the danger appears imminent, especially considering the presence of weapons at home. They should attempt to stabilize Mr. B on effective, tolerable medications to ameliorate his psychosis, and to refer him for long-term psychotherapy to address difficult dynamic issues in the family relationship and encourage compliance with treatment. These steps may help avert a tragedy.

Bottom Line

Individuals who commit parricide often have a history of psychosis, a mood disorder, childhood abuse, and/or difficult relationship dynamics with the parent they kill. Some go on a spree killing in the community. Through careful consideration of individual risk factors, psychiatrists may help prevent some cases of parent murder by a child and possibly more tragedy in the community.

1. Bojanié L, Flynn S, Gianatsi M, et al. The typology of parricide and the role of mental illness: data-driven approach. Aggress Behav. 2020;46(6):516-522.

2. Pinals DS. Parricide. In Friedman SH, ed. Family Murder: Pathologies of Love and Hate. American Psychiatric Publishing; 2019:113-138.

3. Heide KM. Matricide and stepmatricide victims and offenders: an empirical analysis of US arrest data. Behav Sci Law. 2013;31(2):203-214.

4. Bourget D, Gagné P, Labelle ME. Parricide: a comparative study of matricide versus patricide. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2007;35(3):306-312.

5. Heide KM, Frei A. Matricide: a critique of the literature. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2010;11(1):3-17.

6. Marleau JD, Auclair N, Millaud F. Comparison of factors associated with parricide in adults and adolescents. J Fam Viol. 2006;21:321-325.

7. West SG, Feldsher M. Parricide: characteristics of sons and daughters who kill their parents. Current Psychiatry. 2010;9(11):20-38.

8. Green CM. Matricide by sons. Med Sci Law. 1981;21(3):207-214.

9. Friedman SH. Conclusions. In Friedman SH, ed. Family Murder: Pathologies of Love and Hate. American Psychiatric Publishing; 2019:161-164.

10. Campion J, Cravens JM, Rotholc A, et al. A study of 15 matricidal men. Am J Psychiatry. 1985;142(3):312-317.

11. Hall RCW, Friedman SH, Sorrentino R, et al. The myth of school shooters and psychotropic medications. Behav Sci Law. 2019;37(5):540-558.

12. Department of Justice Federal Bureau of Investigation. Active Shooter Incidents: 20-Year Review, 2000-2019. June 1, 2021. Accessed October 12, 2021. https://www.fbi.gov/file-repository/active-shooter-incidents-20-year-review-2000-2019-060121.pdf/view

13. Friedman SH, Hall RCW. Star Wars: The Force Awakens, forensic teaching about matricide. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2017;45(1):128-130.

14. Friedman SH, Hall RCW. Deadly and dysfunctional family dynamics: when fiction mirrors fact. In: Packer S, Fredrick DR, eds. Welcome to Arkham Asylum: Essays on Psychiatry and the Gotham City Institution. McFarland; 2019:65-75.

1. Bojanié L, Flynn S, Gianatsi M, et al. The typology of parricide and the role of mental illness: data-driven approach. Aggress Behav. 2020;46(6):516-522.

2. Pinals DS. Parricide. In Friedman SH, ed. Family Murder: Pathologies of Love and Hate. American Psychiatric Publishing; 2019:113-138.

3. Heide KM. Matricide and stepmatricide victims and offenders: an empirical analysis of US arrest data. Behav Sci Law. 2013;31(2):203-214.

4. Bourget D, Gagné P, Labelle ME. Parricide: a comparative study of matricide versus patricide. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2007;35(3):306-312.

5. Heide KM, Frei A. Matricide: a critique of the literature. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2010;11(1):3-17.

6. Marleau JD, Auclair N, Millaud F. Comparison of factors associated with parricide in adults and adolescents. J Fam Viol. 2006;21:321-325.

7. West SG, Feldsher M. Parricide: characteristics of sons and daughters who kill their parents. Current Psychiatry. 2010;9(11):20-38.

8. Green CM. Matricide by sons. Med Sci Law. 1981;21(3):207-214.

9. Friedman SH. Conclusions. In Friedman SH, ed. Family Murder: Pathologies of Love and Hate. American Psychiatric Publishing; 2019:161-164.

10. Campion J, Cravens JM, Rotholc A, et al. A study of 15 matricidal men. Am J Psychiatry. 1985;142(3):312-317.

11. Hall RCW, Friedman SH, Sorrentino R, et al. The myth of school shooters and psychotropic medications. Behav Sci Law. 2019;37(5):540-558.

12. Department of Justice Federal Bureau of Investigation. Active Shooter Incidents: 20-Year Review, 2000-2019. June 1, 2021. Accessed October 12, 2021. https://www.fbi.gov/file-repository/active-shooter-incidents-20-year-review-2000-2019-060121.pdf/view

13. Friedman SH, Hall RCW. Star Wars: The Force Awakens, forensic teaching about matricide. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2017;45(1):128-130.

14. Friedman SH, Hall RCW. Deadly and dysfunctional family dynamics: when fiction mirrors fact. In: Packer S, Fredrick DR, eds. Welcome to Arkham Asylum: Essays on Psychiatry and the Gotham City Institution. McFarland; 2019:65-75.

Parricide: Characteristics of sons and daughters who kill their parents

Discuss this article at http://currentpsychiatry.blogspot.com/2010/11/parricide-characteristics-of-sons-and.html#comments

Mr. B, age 37, is single and lives with his elderly mother. Since being diagnosed with schizophrenia in his early 20s, he has been intermittently compliant with antipsychotic therapy. When unmedicated, Mr. B develops paranoid delusions and becomes preoccupied with the idea that his mother is plotting to kill him. He has been hospitalized twice in the last 5 years for physical aggression toward his mother. In the last 10 years, Mr. B has been placed in several group homes, but when he takes his medications, he is able to convince his mother to allow him to live with her.

During his most recent stay in his mother’s home, Mr. B again stops taking his psychotropic medications and decompensates. His mother becomes concerned about her son’s paranoid behavior—such as trying to listen in on her telephone conversations and smelling his food before he eats it—and considers having her son involuntarily committed. One day, after she prepares Mr. B a sandwich, he decides the meat is poisoned. When his mother tries to convince him to eat the sandwich, Mr. B becomes enraged and stabs her 54 times with a kitchen knife.

Mr. B is arrested without resistance. He is adjudicated incompetent to stand trial and is restored to competency within 3 months. Mr. B is found not guilty by reason of insanity (NGRI) and is civilly committed to a state psychiatric facility.

Parricide—killing one’s parents—once was referred to as “the schizophrenic crime,”1 but is now recognized as being more complex.2 In the United States, parricides accounted for 2% of all homicides from 1976 to 1998,3 which is consistent with studies from France4 and the United Kingdom.5 Parricide’s scandalous nature has long attracted the public’s fascination (see this article at CurrentPsychiatry.com).

This article primarily focuses on the interplay of the diagnostic and demographic factors seen in adults who kill their biological parents but briefly notes differences seen in juvenile perpetrators and those who kill their stepparents. Knowledge of these characteristics can help clinicians identify and more safely manage patients who may be at risk of harming their parents.

The public maintains a morbid curiosity about parricide. In ancient times, the Roman emperor Nero was responsible for the death of his mother, Agrippina. In 1892, Lizzie Borden attracted national attention—and inspired a children’s song about “40 whacks”—when she was suspected, but acquitted, of murdering her father and stepmother. Charles Whitman, infamous for his 1966 killing spree from the University of Texas at Austin tower, killed his mother before his rampage. In 1993, the trial of the Menendez brothers, who were eventually convicted of murdering their parents, was broadcast on Court TV.

Parricide also plays a role in literature and popular culture. Oedipus would have never been able to marry his mother had he not first killed his father. In the movie Psycho, Alfred Hitchcock told the story of Norman Bates, a hotel owner who killed his mother and preserved her body in the basement. In the novel Carrie, Stephen King uses matricide as a means to sever the relationship between the main character and her domineering mother. In 1989, the band Aerosmith released a song, Janie’s Got a Gun, about a girl who kills her father after he sexually abused her.

A limited evidence base

The common themes found in the literature on parricide should be interpreted cautiously because of the limitations of this research. The number of individuals assessed in these studies often is small, which limits the statistical power of the findings. Studies often are conducted in forensic hospitals, which excludes those who are imprisoned or commit suicide following the acts. Finally, most individuals studied were diagnosed with a psychiatric disorder after the crime, which makes it difficult to distinguish the primary illness from the crime’s effect on a person’s mental state. Additionally, some individuals may be tempted to exaggerate or feign psychiatric symptoms in an effort to be found NGRI or granted leniency during sentencing. Despite these limitations, several conclusions can be drawn from these investigations.

The sex of the victims and perpetrators needs to be carefully considered when reviewing characteristics of those who commit parricide. Killing a mother is matricide, and killing a father is patricide.

Sons who kill their parents

Men are more likely to kill their parents than women.6-9 In a study of 5,488 cases of parricide in the United States, 4,738 (86%) of perpetrators were male.3 Common characteristics of men who commit parricide are listed in Table 1.5,8,10-14

Matricide by sons. Although sons kill their fathers more often than their mothers,15 authors writing about parricide commonly focus on men who commit matricide. Wertham described sons who kill their mothers in terms of the “Orestes Complex,” which refers to ambivalent feelings toward the mother that ultimately manifest in homicidal rage. He noted that many matricides are committed with excessive force, occur in the bedroom, and are precipitated by trivial reasons. Wertham stated that these crimes represent the son’s unconscious hatred for his mother superimposed on sexual desire for her.16 Sigmund Freud argued that matricide served as a displacement defense against incestuous impulses.17

In 5 studies that looked at sons who killed their mothers (n=13 to 58),5,10-13 most of which examined men residing in forensic hospitals after the crime, perpetrators were noted to be immature, dependent, and passive. In a study of 16 men with schizophrenia who committed matricide, subjects perceived themselves as “weak, small, inadequate, hopeless, doubtful about sexual identity, dependent, and unable to accept a separate, adult male role.”11 Mothers generally were domineering, demanding, and possessive.

Based on our literature review, most men who committed matricide had a schizophrenia diagnosis (weighted mean 72%, range 50% to 100%); other diagnoses included depression and personality disorders. Many men were experiencing psychosis shortly before the crime, and their acts were influenced by persecutory delusions and/or auditory hallucinations. Approximately one-quarter of sons killed their mothers for altruistic reasons, such as to relieve actual or perceived suffering.

Nearly all men in these 5 studies were single and lived with their mothers before killing them, and many of the perpetrators’ fathers were absent. Mothers often were the only victims of their sons’ violent acts. In addition to delusional beliefs, sons were motivated to kill their mothers for various reasons, including threatened separation or minor arguments (eg, over food or money). Many of these homicides took place in the home. Sharp or blunt objects were the most common weapons, but guns and strangulation/asphyxiation also were used. Approximately one-half of the men used excessive violence; for example, 1 victim had 177 stab wounds. After the crimes, the perpetrators generally expressed remorse or relief.

Patricide by sons. Psychoanalysts may consider the Oedipal Complex to be the primary impetus for a son to commit patricide. By eliminating his father the son gains possession of his mother.18 Three studies looked at sons who killed their fathers; 2 examined 10 perpetrators residing in a forensic hospital after the crimes8,14 and the third was based on coroners’ reports.10 Although the sons’ personality traits were not described, the fathers were noted to be “domineering and aggressive,” and their relationships with their sons were “cruel and unusual.”8 In our review of these studies, >50% of sons were diagnosed with schizophrenia (weighted mean 60%, range 49% to 80%). Many perpetrators exhibited psychotic symptoms, including delusions and hallucinations. In 1 study, 40% of sons with psychotic symptoms perceived their fathers as posing “threats of physical or psychological annihilation.”14

In 2 of these studies all of the sons were single or separated from their spouses.8,14 Most killed only their fathers at the time of the act. Immediately before the crime, one-half of the fathers were consuming alcohol and/or arguing with their sons. Ninety percent of the fathers were killed by excessive violence. Following the acts, the sons described feeling “relief rather than remorse or guilt…leading to a feeling of freedom from the abnormal relationship.”14 One study noted that, in the course of legal proceedings, one-fifth were deemed competent to stand trial and the others were found to be incompetent and hospitalized.14

Table 1

Sons who kill their parents: Schizophrenia is common

| Sons who kill their mothers | Sons who kill their fathers |

|---|---|

Sons:

| Sons:

|

Mothers:

| Fathers:

|

Crime:

| Crime:

|

| Source: References 5,8,10-14 | |

Daughters who commit parricide

d’Orban and O’Connor conducted the only major study examining women who commit parricide,9 a retrospective evaluation of 17 women who killed a parent and were housed in a prison or hospital. The authors highlight the importance of delusional beliefs as a motive for parricide (Table 2).9

In a 1970 Japanese study of 21 women who killed parents or in-laws, half of the victims were mothers-in-law, but none were biological mothers.19 According to the authors, this finding suggests that relationships between Japanese women and their mothers-in-law often are particularly contentious; however, no research has examined this theory in the United States.

Matricide by daughters. In the d’Orban and O’Connor study,9 >80% of women who committed parricide killed their mothers. In general, the daughters were described as being “in mid-life, living alone with an elderly, domineering mother in marked social isolation.” The parent-child relationship was “characterized by mutual hostility and dependence.” Seventy-five percent of the daughters suffered from psychotic illness. Extreme violence often was used.

Patricide by daughters. Of the 3 women who killed their fathers in d’Orban and O’Connor’s study,9 none were psychotic. Furthermore, 2 women had no psychiatric diagnosis—the third had antisocial personality disorder—and “killed tyrannical fathers in response to prolonged parental violence.” One woman reported that she was forced into a long-term incestuous relationship before killing her father. The women who killed their fathers were younger (mean age 21.3) than those who killed their mothers (mean age 39.5).

Table 2

Daughters who kill their parents: Strained relationships

| Daughters who kill their mothers | Daughters who kill their fathers |

|---|---|

Daughters:

| Daughters:

|

Mothers:

| Fathers:

|

Crime:

| |

| Source: Reference 9 | |

Other perpetrators and victims

Patricide is most often committed by adults20; however, some important conclusions can be drawn regarding juveniles who kill their parents (Table 3).21-27 The most common scenario is of adolescent boys who have no history of psychosis and kill their fathers in a burst of rage brought on by ongoing abuse from parents. These murders typically are followed by feelings of relief rather than remorse.21-27

Stepparents often have a more challenging relationship with children than biological parents.28 Research indicates that stepparents are more likely than biological parents to be killed by juvenile offenders.29 Also, stepparent victims tended to be younger than biological parent victims.29

Table 3

Characteristics of juveniles who kill their parents or stepparents

| Often teenage boys |

| Generally lack history of psychosis |

| Actions often are spontaneous |

| Motivated by long-term parental abuse |

| Often feel relief rather than remorse after the crime |

| More likely to kill stepparents than biological parents |

| Source: References 21-27 |

Clinical applications

Ask adult schizophrenia patients living with a parent about the quality of the relationship. If the relationship is characterized by conflict or abuse or if psychotic symptoms are present, assess for violent thoughts toward the parent. For patients with uncontrolled psychosis coupled with a contentious parental relationship, in addition to aggressively treating psychotic symptoms, consider initiating family therapy, anger management classes, group home placement, or involuntary hospitalization to lower the risk of parricide.

Related resources

- Heide KM, Boots DP. A comparative analysis of media reports of U.S. parricide cases with officially reported national crime data and the psychiatric and psychological literature. Int J Offender Ther Comp Criminol. 2007;51(6):646-675.

- Jacobs A. On matricide: myth, psychoanalysis, and the law of the mother. New York, NY: Columbia University Press; 2007.

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article, or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Gillies H. Murder in the west of Scotland. Br J Psychiatry. 1965;111:1087-1094.

2. Clark SA. Matricide: the schizophrenic crime? Med Sci Law. 1993;33(4):325-328.

3. Federal Bureau of Investigation. Crime in the United States. Washington, DC: Department of Justice; 1998.

4. Devaux C, Petit G, Perol Y, et al. Enquête sure le parricide en France. Ann Med Psychol (Paris). 1974;1:161-168.

5. Green C. Matricide by sons. Med Sci Law. 1981;21:207-214.

6. Marleau JD, Millaud F, Auclair N. A comparison of parricide and attempted parricide: a study of 39 psychotic adults. Int J Law Psychiatry. 2003;26(3):269-279.

7. Weisman AM, Ehrenclou MG, Sharma KK. Double parricide: forensic analysis and psycholegal implications. J Forensic Sci. 2002;47(2):313-317.

8. Singhal S, Dutta A. Who commits patricide? Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1990;82:40-43.

9. d’Orban PT, O’Connor A. Women who kill their parents. Br J Psychiatry. 1989;154:27-33.

10. Bourget D, Gagné P, Labelle ME. Parricide: a comparative study of matricide versus patricide. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2007;35(3):306-312.

11. Singhal S, Dutta A. Who commits matricide? Med Sci Law. 1992;32:213-217.

12. Campion J, Cravens JM, Rotholc A, et al. A study of 15 matricidal men. Am J Psychiatry. 1985;142:312-317.

13. O’Connell B. Matricide (report of a meeting of the Royal Medico-Psychological Association). Lancet. 1963;1:1083-1084.

14. Cravens JM, Campion J, Rotholc A, et al. A study of 10 men charged with patricide. Am J Psychiatry. 1985;142(9):1089-1092.

15. Shon PC, Targonski JR. Declining trends in U.S. parricides, 1976-1978: testing the Freudian assumptions. Int J Law Psychiatry. 2003;26:387-402.

16. Wertham F. Dark legend: a study in murder. New York, NY: Duell, Sloan and Pearce; 1941.

17. Freud S. The interpretation of dreams. Strachey J, trans. New York, NY: Discus; 1925.

18. Freud S. Sigmund Freud: collected papers. Vol 5. New York, NY: Basic Books; 1959.

19. Hirose K. A psychiatric study of female homicide: on the cases of parricide. Acta Criminologiae et Medicinae Legalis Japonica. 1970;36:29.-

20. Heide KM. Parents who get killed and the children who kill them. J Interpers Violence. 1993;8(4):531-544.

21. Hellsten P, Katila O. Murder and homicide by children under 15 in Finland. Psychiatr Q Suppl. 1965;39:54-74.

22. Scherl DJ, Mack JE. A study of adolescent matricide. J Am Acad Child Psychiatry. 1966;5:569-593.

23. Sadoff RL. Clinical observations on parricide. Psychiatr Q. 1971;45:65-69.

24. Tanay E. Proceedings: adolescents who kill parents—reactive parricide. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 1973;7:263-277.

25. Tuovinen M. On parricide. Psychiatrica Fennica. 1973;141-146.

26. Corder BF, Ball BC, Haizlip TM, et al. Adolescent parricide: a comparison with other adolescent murder. Am J Psychiatry. 1976;133:957-961.

27. Post S. Adolescent parricide in abusive families. Child Welfare. 1982;61:445-455.

28. Daly M, Wilson M. Evolutionary social psychology and family homicide. Science. 1988;242:520-524.

29. Heide KM. Why kids kill parents: child abuse and adolescent homicide. Columbus, OH: Ohio State University Press; 1992.

Discuss this article at http://currentpsychiatry.blogspot.com/2010/11/parricide-characteristics-of-sons-and.html#comments

Mr. B, age 37, is single and lives with his elderly mother. Since being diagnosed with schizophrenia in his early 20s, he has been intermittently compliant with antipsychotic therapy. When unmedicated, Mr. B develops paranoid delusions and becomes preoccupied with the idea that his mother is plotting to kill him. He has been hospitalized twice in the last 5 years for physical aggression toward his mother. In the last 10 years, Mr. B has been placed in several group homes, but when he takes his medications, he is able to convince his mother to allow him to live with her.

During his most recent stay in his mother’s home, Mr. B again stops taking his psychotropic medications and decompensates. His mother becomes concerned about her son’s paranoid behavior—such as trying to listen in on her telephone conversations and smelling his food before he eats it—and considers having her son involuntarily committed. One day, after she prepares Mr. B a sandwich, he decides the meat is poisoned. When his mother tries to convince him to eat the sandwich, Mr. B becomes enraged and stabs her 54 times with a kitchen knife.

Mr. B is arrested without resistance. He is adjudicated incompetent to stand trial and is restored to competency within 3 months. Mr. B is found not guilty by reason of insanity (NGRI) and is civilly committed to a state psychiatric facility.

Parricide—killing one’s parents—once was referred to as “the schizophrenic crime,”1 but is now recognized as being more complex.2 In the United States, parricides accounted for 2% of all homicides from 1976 to 1998,3 which is consistent with studies from France4 and the United Kingdom.5 Parricide’s scandalous nature has long attracted the public’s fascination (see this article at CurrentPsychiatry.com).

This article primarily focuses on the interplay of the diagnostic and demographic factors seen in adults who kill their biological parents but briefly notes differences seen in juvenile perpetrators and those who kill their stepparents. Knowledge of these characteristics can help clinicians identify and more safely manage patients who may be at risk of harming their parents.

The public maintains a morbid curiosity about parricide. In ancient times, the Roman emperor Nero was responsible for the death of his mother, Agrippina. In 1892, Lizzie Borden attracted national attention—and inspired a children’s song about “40 whacks”—when she was suspected, but acquitted, of murdering her father and stepmother. Charles Whitman, infamous for his 1966 killing spree from the University of Texas at Austin tower, killed his mother before his rampage. In 1993, the trial of the Menendez brothers, who were eventually convicted of murdering their parents, was broadcast on Court TV.

Parricide also plays a role in literature and popular culture. Oedipus would have never been able to marry his mother had he not first killed his father. In the movie Psycho, Alfred Hitchcock told the story of Norman Bates, a hotel owner who killed his mother and preserved her body in the basement. In the novel Carrie, Stephen King uses matricide as a means to sever the relationship between the main character and her domineering mother. In 1989, the band Aerosmith released a song, Janie’s Got a Gun, about a girl who kills her father after he sexually abused her.

A limited evidence base

The common themes found in the literature on parricide should be interpreted cautiously because of the limitations of this research. The number of individuals assessed in these studies often is small, which limits the statistical power of the findings. Studies often are conducted in forensic hospitals, which excludes those who are imprisoned or commit suicide following the acts. Finally, most individuals studied were diagnosed with a psychiatric disorder after the crime, which makes it difficult to distinguish the primary illness from the crime’s effect on a person’s mental state. Additionally, some individuals may be tempted to exaggerate or feign psychiatric symptoms in an effort to be found NGRI or granted leniency during sentencing. Despite these limitations, several conclusions can be drawn from these investigations.

The sex of the victims and perpetrators needs to be carefully considered when reviewing characteristics of those who commit parricide. Killing a mother is matricide, and killing a father is patricide.

Sons who kill their parents

Men are more likely to kill their parents than women.6-9 In a study of 5,488 cases of parricide in the United States, 4,738 (86%) of perpetrators were male.3 Common characteristics of men who commit parricide are listed in Table 1.5,8,10-14

Matricide by sons. Although sons kill their fathers more often than their mothers,15 authors writing about parricide commonly focus on men who commit matricide. Wertham described sons who kill their mothers in terms of the “Orestes Complex,” which refers to ambivalent feelings toward the mother that ultimately manifest in homicidal rage. He noted that many matricides are committed with excessive force, occur in the bedroom, and are precipitated by trivial reasons. Wertham stated that these crimes represent the son’s unconscious hatred for his mother superimposed on sexual desire for her.16 Sigmund Freud argued that matricide served as a displacement defense against incestuous impulses.17

In 5 studies that looked at sons who killed their mothers (n=13 to 58),5,10-13 most of which examined men residing in forensic hospitals after the crime, perpetrators were noted to be immature, dependent, and passive. In a study of 16 men with schizophrenia who committed matricide, subjects perceived themselves as “weak, small, inadequate, hopeless, doubtful about sexual identity, dependent, and unable to accept a separate, adult male role.”11 Mothers generally were domineering, demanding, and possessive.

Based on our literature review, most men who committed matricide had a schizophrenia diagnosis (weighted mean 72%, range 50% to 100%); other diagnoses included depression and personality disorders. Many men were experiencing psychosis shortly before the crime, and their acts were influenced by persecutory delusions and/or auditory hallucinations. Approximately one-quarter of sons killed their mothers for altruistic reasons, such as to relieve actual or perceived suffering.

Nearly all men in these 5 studies were single and lived with their mothers before killing them, and many of the perpetrators’ fathers were absent. Mothers often were the only victims of their sons’ violent acts. In addition to delusional beliefs, sons were motivated to kill their mothers for various reasons, including threatened separation or minor arguments (eg, over food or money). Many of these homicides took place in the home. Sharp or blunt objects were the most common weapons, but guns and strangulation/asphyxiation also were used. Approximately one-half of the men used excessive violence; for example, 1 victim had 177 stab wounds. After the crimes, the perpetrators generally expressed remorse or relief.

Patricide by sons. Psychoanalysts may consider the Oedipal Complex to be the primary impetus for a son to commit patricide. By eliminating his father the son gains possession of his mother.18 Three studies looked at sons who killed their fathers; 2 examined 10 perpetrators residing in a forensic hospital after the crimes8,14 and the third was based on coroners’ reports.10 Although the sons’ personality traits were not described, the fathers were noted to be “domineering and aggressive,” and their relationships with their sons were “cruel and unusual.”8 In our review of these studies, >50% of sons were diagnosed with schizophrenia (weighted mean 60%, range 49% to 80%). Many perpetrators exhibited psychotic symptoms, including delusions and hallucinations. In 1 study, 40% of sons with psychotic symptoms perceived their fathers as posing “threats of physical or psychological annihilation.”14

In 2 of these studies all of the sons were single or separated from their spouses.8,14 Most killed only their fathers at the time of the act. Immediately before the crime, one-half of the fathers were consuming alcohol and/or arguing with their sons. Ninety percent of the fathers were killed by excessive violence. Following the acts, the sons described feeling “relief rather than remorse or guilt…leading to a feeling of freedom from the abnormal relationship.”14 One study noted that, in the course of legal proceedings, one-fifth were deemed competent to stand trial and the others were found to be incompetent and hospitalized.14

Table 1

Sons who kill their parents: Schizophrenia is common

| Sons who kill their mothers | Sons who kill their fathers |

|---|---|

Sons:

| Sons:

|

Mothers:

| Fathers:

|

Crime:

| Crime:

|

| Source: References 5,8,10-14 | |

Daughters who commit parricide

d’Orban and O’Connor conducted the only major study examining women who commit parricide,9 a retrospective evaluation of 17 women who killed a parent and were housed in a prison or hospital. The authors highlight the importance of delusional beliefs as a motive for parricide (Table 2).9

In a 1970 Japanese study of 21 women who killed parents or in-laws, half of the victims were mothers-in-law, but none were biological mothers.19 According to the authors, this finding suggests that relationships between Japanese women and their mothers-in-law often are particularly contentious; however, no research has examined this theory in the United States.

Matricide by daughters. In the d’Orban and O’Connor study,9 >80% of women who committed parricide killed their mothers. In general, the daughters were described as being “in mid-life, living alone with an elderly, domineering mother in marked social isolation.” The parent-child relationship was “characterized by mutual hostility and dependence.” Seventy-five percent of the daughters suffered from psychotic illness. Extreme violence often was used.

Patricide by daughters. Of the 3 women who killed their fathers in d’Orban and O’Connor’s study,9 none were psychotic. Furthermore, 2 women had no psychiatric diagnosis—the third had antisocial personality disorder—and “killed tyrannical fathers in response to prolonged parental violence.” One woman reported that she was forced into a long-term incestuous relationship before killing her father. The women who killed their fathers were younger (mean age 21.3) than those who killed their mothers (mean age 39.5).

Table 2

Daughters who kill their parents: Strained relationships

| Daughters who kill their mothers | Daughters who kill their fathers |

|---|---|

Daughters:

| Daughters:

|

Mothers:

| Fathers:

|

Crime:

| |

| Source: Reference 9 | |

Other perpetrators and victims

Patricide is most often committed by adults20; however, some important conclusions can be drawn regarding juveniles who kill their parents (Table 3).21-27 The most common scenario is of adolescent boys who have no history of psychosis and kill their fathers in a burst of rage brought on by ongoing abuse from parents. These murders typically are followed by feelings of relief rather than remorse.21-27

Stepparents often have a more challenging relationship with children than biological parents.28 Research indicates that stepparents are more likely than biological parents to be killed by juvenile offenders.29 Also, stepparent victims tended to be younger than biological parent victims.29

Table 3

Characteristics of juveniles who kill their parents or stepparents

| Often teenage boys |

| Generally lack history of psychosis |

| Actions often are spontaneous |

| Motivated by long-term parental abuse |

| Often feel relief rather than remorse after the crime |

| More likely to kill stepparents than biological parents |

| Source: References 21-27 |

Clinical applications

Ask adult schizophrenia patients living with a parent about the quality of the relationship. If the relationship is characterized by conflict or abuse or if psychotic symptoms are present, assess for violent thoughts toward the parent. For patients with uncontrolled psychosis coupled with a contentious parental relationship, in addition to aggressively treating psychotic symptoms, consider initiating family therapy, anger management classes, group home placement, or involuntary hospitalization to lower the risk of parricide.

Related resources

- Heide KM, Boots DP. A comparative analysis of media reports of U.S. parricide cases with officially reported national crime data and the psychiatric and psychological literature. Int J Offender Ther Comp Criminol. 2007;51(6):646-675.

- Jacobs A. On matricide: myth, psychoanalysis, and the law of the mother. New York, NY: Columbia University Press; 2007.

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article, or with manufacturers of competing products.

Discuss this article at http://currentpsychiatry.blogspot.com/2010/11/parricide-characteristics-of-sons-and.html#comments

Mr. B, age 37, is single and lives with his elderly mother. Since being diagnosed with schizophrenia in his early 20s, he has been intermittently compliant with antipsychotic therapy. When unmedicated, Mr. B develops paranoid delusions and becomes preoccupied with the idea that his mother is plotting to kill him. He has been hospitalized twice in the last 5 years for physical aggression toward his mother. In the last 10 years, Mr. B has been placed in several group homes, but when he takes his medications, he is able to convince his mother to allow him to live with her.

During his most recent stay in his mother’s home, Mr. B again stops taking his psychotropic medications and decompensates. His mother becomes concerned about her son’s paranoid behavior—such as trying to listen in on her telephone conversations and smelling his food before he eats it—and considers having her son involuntarily committed. One day, after she prepares Mr. B a sandwich, he decides the meat is poisoned. When his mother tries to convince him to eat the sandwich, Mr. B becomes enraged and stabs her 54 times with a kitchen knife.

Mr. B is arrested without resistance. He is adjudicated incompetent to stand trial and is restored to competency within 3 months. Mr. B is found not guilty by reason of insanity (NGRI) and is civilly committed to a state psychiatric facility.

Parricide—killing one’s parents—once was referred to as “the schizophrenic crime,”1 but is now recognized as being more complex.2 In the United States, parricides accounted for 2% of all homicides from 1976 to 1998,3 which is consistent with studies from France4 and the United Kingdom.5 Parricide’s scandalous nature has long attracted the public’s fascination (see this article at CurrentPsychiatry.com).

This article primarily focuses on the interplay of the diagnostic and demographic factors seen in adults who kill their biological parents but briefly notes differences seen in juvenile perpetrators and those who kill their stepparents. Knowledge of these characteristics can help clinicians identify and more safely manage patients who may be at risk of harming their parents.

The public maintains a morbid curiosity about parricide. In ancient times, the Roman emperor Nero was responsible for the death of his mother, Agrippina. In 1892, Lizzie Borden attracted national attention—and inspired a children’s song about “40 whacks”—when she was suspected, but acquitted, of murdering her father and stepmother. Charles Whitman, infamous for his 1966 killing spree from the University of Texas at Austin tower, killed his mother before his rampage. In 1993, the trial of the Menendez brothers, who were eventually convicted of murdering their parents, was broadcast on Court TV.

Parricide also plays a role in literature and popular culture. Oedipus would have never been able to marry his mother had he not first killed his father. In the movie Psycho, Alfred Hitchcock told the story of Norman Bates, a hotel owner who killed his mother and preserved her body in the basement. In the novel Carrie, Stephen King uses matricide as a means to sever the relationship between the main character and her domineering mother. In 1989, the band Aerosmith released a song, Janie’s Got a Gun, about a girl who kills her father after he sexually abused her.

A limited evidence base

The common themes found in the literature on parricide should be interpreted cautiously because of the limitations of this research. The number of individuals assessed in these studies often is small, which limits the statistical power of the findings. Studies often are conducted in forensic hospitals, which excludes those who are imprisoned or commit suicide following the acts. Finally, most individuals studied were diagnosed with a psychiatric disorder after the crime, which makes it difficult to distinguish the primary illness from the crime’s effect on a person’s mental state. Additionally, some individuals may be tempted to exaggerate or feign psychiatric symptoms in an effort to be found NGRI or granted leniency during sentencing. Despite these limitations, several conclusions can be drawn from these investigations.

The sex of the victims and perpetrators needs to be carefully considered when reviewing characteristics of those who commit parricide. Killing a mother is matricide, and killing a father is patricide.

Sons who kill their parents

Men are more likely to kill their parents than women.6-9 In a study of 5,488 cases of parricide in the United States, 4,738 (86%) of perpetrators were male.3 Common characteristics of men who commit parricide are listed in Table 1.5,8,10-14