User login

Factor V Leiden: How great is the risk of venous thromboembolism?

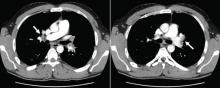

A 29-year-old white man with no chronic medical problems presents to the emergency department with shortness of breath, left-sided pleuritic chest pain, cough, and hemoptysis. These symptoms began abruptly 1 day ago and have persisted. He also has mild pain and swelling in both calves. He denies having any fever, night sweats, or chills. On further questioning, he reports having taken a long, nonstop driving trip that lasted 8 hours 1 week ago.

His medical history is negative, and he specifically reports no history of deep venous thrombosis or pulmonary embolism. He underwent appendectomy 10 years ago but has had no other operations. He does not take any medications. His family history is noncontributory and is negative for venous thromboembolism. He smokes and uses alcohol occasionally but not illicit drugs.

Examination. He appears to be in considerable distress because of his chest pain. His temperature is 100.4°F (38.0°C), blood pressure 125/70 mm Hg, heart rate 125 beats per minute, respiratory rate 26 breaths per minute, oxygen saturation 92% on room air, and body mass index 19 kg/m2.

Chest examination reveals diminished vesicular breathing in the left base, which is normal to percussion without added sounds. Both calves are swollen and tender to palpation without skin discoloration. The rest of his examination is normal.

Laboratory values:

- White blood cell count 9.3 × 109/L (reference range 4.5–11.0)

- Hemoglobin 15.9 g/dL (14.0–17.5)

- Platelets 205 × 109/L (150–350)

- Sodium 140 mEq/L (136–142)

- Potassium 3.9 mEq/L (3.5–5.0)

- Chloride 108 mEq/L (96–106)

- Bicarbonate 23 mEq/L (21–28)

- Blood urea nitrogen 14 mg/dL (8–23)

- Creatinine 0.9 mg/dL (0.6–1.2)

- Glucose 95 mg/dL (70–110)

- International normalized ratio (INR) 0.90 (0.00–1.2)

- Partial thromboplastin time 27.5 seconds (24.6–31.8)

- Creatine phosphokinase 205 U/L (39–308)

- Troponin T < 0.015 ng/mL (0.01–0.045).

Pulmonary embolism is diagnosed

Factor V Leiden is diagnosed, and the patient recovers with treatment

Anticoagulation is started in the emergency department.

Given this patient’s young age and clot burden, a hypercoagulable state is suspected. Thrombophilia screening is performed, with tests for the factor V Leiden mutation, the prothrombin G20210A mutation, and antiphospholipid and lupus anticoagulant antibodies. The rest of the thrombophilia panel, including antithrombin III, factor VIII, protein C, and protein S, is deferred because the levels of these substances would be expected to change during the acute thrombosis.

The direct test for factor V Leiden mutation is positive for the heterozygous type. The test for the prothrombin G20210A mutation is negative, and his antiphospholipid antibody levels, including the lupus anticoagulant titer, are within normal limits.

The patient is kept on a standard regimen of unfractionated heparin, overlapped with warfarin (Coumadin) until his INR is 2.0 to 3.0 on 2 consecutive days. His hospital course is uneventful and his condition gradually improves.

He is discharged home to continue on oral anticoagulation for 6 months with a target INR of 2.0 to 3.0. Two weeks after completing his anticoagulation therapy, his levels of antithrombin III, factor VIII, protein C, and protein S are all within normal limits.

FACTOR V LEIDEN IS COMMON

Factor V Leiden is the most common inherited thrombophilia, with a prevalence of 3% to 7% in the general US population,1 approximately 5% in whites, 2.2% in Hispanics, and 1.2% in blacks.2 Its prevalence in patients with venous thromboembolism, however, is 50%.1,3 The annual incidence of venous thromboembolism in patients with factor V Leiden is 0.5%.4,5

MORE COAGULATION, LESS ANTICOAGULATION

Factor V has a critical position in both the coagulant and anticoagulant pathways. Factor V Leiden results in a hypercoagulable state by both increasing coagulation and decreasing anticoagulation.

This mutation causes factor V to be resistant to being cleaved and inactivated by activated protein C, a condition known as APC resistance. As a result, more factor Va is available within the prothrombinase complex, increasing coagulation by increased generation of thrombin.6–8

Furthermore, a cofactor formed by cleavage of factor V at position 506 is thought to support activated protein C in degrading factor VIIIa (in the tenase complex), along with protein S. People with factor V Leiden lack this cleavage product and thus have less anticoagulant activity from activated protein C. The increased coagulation and decreased anticoagulation appear to contribute equally to the hypercoagulable state in factor V Leiden-associated APC resistance.9–11

Heterozygosity for the factor V Leiden mutation accounts for 90% to 95% of cases of APC resistance. A much smaller number of people are homozygous for it.1

People who are homozygous for factor V Leiden are at higher risk of venous thromboembolism than those who are heterozygous for it, since the latter group’s blood contains both factor V Leiden and normal factor V. The normal factor V allows anticoagulation via the second pathway of inactivation of factor VIIIa by activated protein C, giving some protection against thrombosis. In people who are homozygous for factor V Leiden, the lack of normal factor V acting as an anticoagulant protein results in a higher thrombotic risk.9–11

Other factor V mutations may also cause APC resistance

Although factor V Leiden is the only genetic defect for which a causal relationship with APC resistance has been clearly determined, other, rarer hereditary factor V mutations or polymorphisms have been described, such as factor V Cambridge (Arg306Thr)12 and factor V Hong Kong (Arg306Gly).13 These mutations may result in APC resistance, but their clinical association with thrombosis is less clear.14 Factor V Liverpool (Ile359Thr) is associated with a higher risk of thrombosis, apparently because of reduced APC-mediated inactivation of factor Va and because it is a poor cofactor with activated protein C for the inactivation of factor VIIIa.15

An R2 haplotype has also been described in association with APC resistance.16,17 The phenomenon may be due to a reduction in activated protein C cofactor activity.9 However, not all studies have been convincing regarding the role of this haplotype in clinical disease.18 Coinheritance of this haplotype with factor V Leiden may increase the risk of venous thromboembolism above that associated with factor V Leiden alone.19

Although factor V Leiden is the most common cause of inherited APC resistance, other changes in hemostasis cause acquired APC resistance and may contribute to the thrombotic tendency in these patients.20–22 The most common causes of acquired APC resistance include elevated factor VIII levels,23–25 pregnancy,26–28 use of oral contraceptives,29,30 and antiphospholipid antibodies.31

USUALLY MANIFESTS AS DEEP VEIN THROMBOSIS

Factor V Leiden usually manifests as deep vein thrombosis with or without pulmonary embolism, but thrombosis in unusual locations also occurs.32

The risk of a first episode of venous thromboembolism is two to five times higher with heterozygous factor V Leiden. However, even though the relative risk is high, the absolute risk is low. Furthermore, despite the higher risk of venous thrombosis, there is no evidence that heterozygosity for factor V Leiden increases the overall mortality rate.4,33–36

In people with homozygous factor V Leiden or with combined inherited thrombophilias, the risk of venous thromboembolism is increased to a greater degree: it is 20 to 50 times higher.7,8,37–39 However, whether the risk of death is higher is not clear.

VENOUS THROMBOEMBOLISM IS MULTIFACTORIAL

The pathogenesis of venous thromboembolism is multifactorial and involves an interaction between inherited and acquired factors. Very often, people with factor V Leiden have additional risk factors that contribute to the development of venous clots, and it is very unusual for them to have thrombosis in the absence of these additional factors.

These factors include older age, surgery, obesity, prolonged travel, immobility, hospitalization, oral contraceptive use, hormonal replacement therapy, pregnancy, and malignancy. They increase the risk of venous thrombosis in normal individuals as well, but more so in people with factor V Leiden.40–43

Testing for other known causes of thrombophilia may also be pursued. These include elevated homocysteine levels, the factor II (prothrombin) G20210A mutation, anticardiolipin antibody, lupus anticoagulant, and deficiencies of antithrombin III, protein C, and protein S.

Factor V Leiden by itself does not appear to increase the risk of arterial thrombosis, ie, heart attack and stroke.33,38,44–46

Family history: A risk indicator for venous thrombosis

Family history is an important indicator of risk for a first venous thromboembolic event, regardless of other risk factors identified. The risk of a first event is two to three times higher in people with a family history of thrombosis in a first-degree relative. The risk is four times higher when multiple family members are affected, at least one of them before age 50.47

In people with genetic thrombophilia, the risk of thrombosis (especially unprovoked thrombosis at a young age) is also higher in those with a strong family history than in those without a family history. In those with factor V Leiden, the risk of venous thromboembolism is three to four times higher if there is a positive family history. The risk is five times higher in carriers of factor V Leiden with a family history of venous thromboembolism before age 50, and 13 times higher in those with more than one affected family member.47

Possible shared environmental factors or coinheritance of other unidentified genetic factors may also contribute to the higher susceptibility in thrombosis-prone families.

TESTING FOR APC RESISTANCE AND FACTOR V LEIDEN

The factor V Leiden mutation can be detected directly by genetic testing of peripheral blood mononuclear cells. This method is relatively time-consuming and expensive, however.

At present, the most cost-effective approach is to test first for APC resistance using a second-generation coagulation assay—the modified APC sensitivity test. In this clot-based method, the patient’s sample is prediluted with factor V-deficient plasma to eliminate the effect of lupus anticoagulants and factor deficiencies that could prolong the baseline clotting time, and heparin is inactivated by polybrene. Then either an augmented partial-thromboplastin-time-based assay or a tissue-factor-dependent factor V assay is performed.

This test is nearly 100% sensitive and specific for factor V Leiden, in contrast to the first-generation, or classic, APC sensitivity test, which lacked specificity and sensitivity for it.9–11,48–60 This modification also permits testing of patients receiving anticoagulants or who have abnormal augmented partial thromboplastin times due to coagulation factor deficiencies.

A positive result on the modified APC sensitivity test should be confirmed by a direct genetic test for the factor V Leiden mutation. An APC resistance assay is unnecessary if a direct genetic test is used initially.

HOW LONG TO GIVE ANTICOAGULATION AFTER VENOUS THROMBOEMBOLISM?

Patients who have had an episode of venous thromboembolism have to be treated with anticoagulants.

In general, the initial management of venous thromboembolism in patients with heritable thrombophilias is no different from that in any other patient with a clot. Anticoagulants such as warfarin are given at a target INR of 2.5 (range 2.0–3.0).32 The duration of treatment is based on the risk factors that resulted in the thrombotic event.

After a first event, some authorities recommend anticoagulant therapy for 6 months.32 A shorter period (3 months) is recommended if there is a transient risk factor (eg, surgery, oral contraceptive use, travel, pregnancy, the puerperium) and the thrombosis is confined to distal veins (eg, the calf veins).32

Factor V Leiden does not necessarily increase the risk of recurrent events in patients who have a transient risk factor. Therefore, people who are heterozygous for this mutation do not usually need to be treated lifelong with anticoagulants if they have had only one episode of deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism, given the risk of bleeding associated with anticoagulation, unless they have additional risk factors.

Conditions in which indefinite anticoagulation may be required after careful consideration of the risks and benefits are:

- Life-threatening events such as near-fatal pulmonary embolism

- Cerebral or visceral vein thrombosis

- Recurrent thrombotic events

- Additional persistent risk factors (eg, active malignant neoplasm, extremity paresis, and antiphospholipid antibodies)

- Combined thrombophilias (eg, combined heterozygosity for factor V Leiden and the prothrombin G20210A mutation)

- Homozygosity for factor V Leiden.32,46,48

Factor V Leiden by itself or combined with other thrombophilic abnormalities is not associated with a higher risk of recurrent venous thromboembolism during warfarin therapy (a possible exception is the combination of factor V Leiden plus antiphospholipid antibodies).32,34 Furthermore, current evidence suggests that no thrombophilic defect is a clinically important risk factor for recurrent venous thromboembolism after anticoagulant therapy is stopped. All these facts indicate that clinical factors are probably more important than laboratory abnormalities in determining the duration of anticoagulation therapy.32,35,36,61–63

PRIMARY PROPHYLAXIS IN PATIENTS WITH FACTOR V LEIDEN

Factor V Leiden is only one of many risk factors for deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism. If carriers of factor V Leiden have never had a blood clot, then they are not routinely treated with an anticoagulant. Rather, they should be counseled about reducing or eliminating other factors that may add to their risk of developing a clot in the future.

Usually, the effect of risk factors is additive: the more risk factors present, the higher the risk.46,50 Sometimes, however, the effect of multiple risk factors is more than additive.

Some risk factors, such as genetics or age, are not alterable, but many can be controlled by medications or lifestyle modifications. Therefore, general measures and precautions are recommended to minimize the risk of thrombosis. For example:

Losing weight (if the patient is overweight) is an important intervention for risk reduction, since obesity is probably the most common modifiable risk factor for developing blood clots.

Avoiding long periods of immobility is recommended. For example, if the patient is taking a long car ride (more than 2 hours), then stopping every few hours and walking around for a few minutes is a good way to keep the blood circulating. If the patient has a desk job, getting up and walking around the office periodically is advised. On long airplane trips, a walk in the aisle every so often and preventing dehydration by drinking plenty of fluids and avoiding alcohol are recommended.

Wearing elastic stockings with a graduated elastic pressure may prevent deep venous thrombosis from developing on long flights.63–65

Staying active and getting regular exercise through such activities as walking, bicycling, or swimming are helpful.

Avoiding smoking is critical.50,63

Thromboprophylaxis is recommended for most acutely ill hospitalized patients, especially those confined to bed with additional risk factors. Guidelines for prophylaxis are based on an individualized risk assessment and not on thrombophilia status. Prophylactic anticoagulation is routinely recommended for patients undergoing major high-risk surgery, such as an orthopedic, urologic, gynecologic, or bariatric procedure. Any excess thrombotic risk conferred by thrombophilia is likely small compared with the risk of surgery, and recommendations on the duration and intensity of thromboprophylaxis are not based on thrombophilic status.46,48

Education. Pain, swelling, redness of a limb, unexplained shortness of breath, and chest pain are the most common symptoms of deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism.46,50 It is crucial to teach patients with factor V Leiden to recognize these symptoms and to seek early medical attention in case they experience any of them.

SCREENING FAMILY MEMBERS FOR THE FACTOR V LEIDEN MUTATION

Factor V Leiden by itself is a relatively mild thrombophilic defect that does not cause thrombosis in all carriers, and there is no evidence that early diagnosis reduces rates of morbidity or mortality. Therefore, routine screening of all asymptomatic relatives of affected patients with venous thrombosis is not recommended. Rather, the decision to screen should be made on an individual basis.50,66

Screening may be beneficial in selected cases, especially when patients have a strong family history of recurrent venous thrombosis at a young age (younger than 50 years) and the family member has additional risk factors for venous thromboembolism such as oral contraception or is planning for pregnancy.32,48,49,66

- Rees DC, Cox M, Clegg JB. World distribution of factor V Leiden. Lancet 1995; 346:1133–1134.

- Ridker PM, Miletich JP, Hennekens CH, Buring JE. Ethnic distribution of factor V Leiden in 4047 men and women. Implications for venous thromboembolism screening. JAMA 1997; 277:1305–1307.

- Rosendaal FR, Koster T, Vandenbroucke JP, Reitsma PH. High risk of thrombosis in patients homozygous for factor V Leiden (activated protein C resistance). Blood 1995; 85:1504–1508.

- Stolz E, Kemkes-Matthes B, Pötzsch B, et al. Screening for thrombophilic risk factors among 25 German patients with cerebral venous thrombosis. Acta Neurol Scand 2000; 102:31–36.

- Langlois NJ, Wells PS. Risk of venous thromboembolism in relatives of symptomatic probands with thrombophilia: a systematic review. Thromb Haemost 2003; 90:17–26.

- Juul K, Tybjaerg-Hansen A, Mortensen J, Lange P, Vestbo J, Nordestgaard BG. Factor V leiden homozygosity, dyspnea, and reduced pulmonary function. Arch Intern Med 2005; 165:2032–2036.

- Bertina RM, Koeleman BP, Koster T, et al. Mutation in blood coagulation factor V associated with resistance to activated protein C. Nature 1994; 369:64–67.

- Dahlbäck B. New molecular insights into the genetics of thrombophilia. Resistance to activated protein C caused by Arg506 to Gln mutation in factor V as a pathogenic risk factor for venous thrombosis. Thromb Haemost 1995; 74:139–148.

- Castoldi E, Brugge JM, Nicolaes GA, Girelli D, Tans G, Rosing J. Impaired APC cofactor activity of factor V plays a major role in the APC resistance associated with the factor V Leiden (R506Q) and R2 (H1299R) mutations. Blood 2004; 103:4173–4179.

- Dahlback B. Anticoagulant factor V and thrombosis risk (editorial). Blood 2004; 103:3995.

- Simioni P, Castoldi E, Lunghi B, Tormene D, Rosing J, Bernardi F. An underestimated combination of opposites resulting in enhanced thrombotic tendency. Blood 2005; 106:2363–2365.

- Williamson D, Brown K, Luddington R, Baglin C, Baglin T. Factor V Cambridge: a new mutation (Arg306-->Thr) associated with resistance to activated protein C. Blood 1998; 91:1140–1144.

- Chan WP, Lee CK, Kwong YL, Lam CK, Liang R. A novel mutation of Arg306 of factor V gene in Hong Kong Chinese. Blood 1998; 91:1135–1139.

- Liang R, Lee CK, Wat MS, Kwong YL, Lam CK, Liu HW. Clinical significance of Arg306 mutations of factor V gene. Blood 1998; 92:2599–2600.

- Steen M, Norstrøm EA, Tholander AL, et al. Functional characterization of factor V-Ile359Thr: a novel mutation associated with thrombosis. Blood 2004; 103:3381–3387.

- Bernardi F, Faioni EM, Castoldi E, et al. A factor V genetic component differing from factor V R506Q contributes to the activated protein C resistance phenotype. Blood 1997; 90:1552–1557.

- Lunghi B, Castoldi E, Mingozzi F, Bernardi F. A new factor V gene polymorphism (His 1254 Arg) present in subjects of African origin mimics the R2 polymorphism (His 1299 Arg). Blood 1998; 91:364–365.

- Luddington R, Jackson A, Pannerselvam S, Brown K, Baglin T. The factor V R2 allele: risk of venous thromboembolism, factor V levels and resistance to activated protein C. Thromb Haemost 2000; 83:204–208.

- Faioni EM, Franchi F, Bucciarelli P, et al. Coinheritance of the HR2 haplotype in the factor V gene confers an increased risk of venous thromboembolism to carriers of factor V R506Q (factor V Leiden). Blood 1999; 94:3062–3066.

- Clark P, Walker ID. The phenomenon known as acquired activated protein C resistance. Br J Haematol 2001; 115:767–773.

- Tosetto A, Simioni M, Madeo D, Rodeghiero F. Intraindividual consistency of the activated protein C resistance phenotype. Br J Haematol 2004; 126:405–409.

- de Visser MC, Rosendaal FR, Bertina RM. A reduced sensitivity for activated protein C in the absence of factor V Leiden increases the risk of venous thrombosis. Blood 1999; 93:1271–1276.

- Kraaijenhagen RA, in’t Anker PS, Koopman MM, et al. High plasma concentration of factor VIIIc is a major risk factor for venous thromboembolism. Thromb Haemost 2000; 83:5–9.

- Kamphuisen PW, Eikenboom JC, Bertina RM. Elevated factor VIII levels and the risk of thrombosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2001; 21:731–738.

- Koster T, Blann AD, Briët E, Vandenbroucke JP, Rosendaal FR. Role of clotting factor VIII in effect of von Willebrand factor on occurrence of deep-vein thrombosis. Lancet 1995; 345:152–155.

- Clark P, Brennand J, Conkie JA, McCall F, Greer IA, Walker ID. Activated protein C sensitivity, protein C, protein S and coagulation in normal pregnancy. Thromb Haemost 1998; 79:1166–1170.

- Cumming AM, Tait RC, Fildes S, Yoong A, Keeney S, Hay CR. Development of resistance to activated protein C during pregnancy. Br J Haematol 1995; 90:725–727.

- Mathonnet F, de Mazancourt P, Bastenaire B, et al. Activated protein C sensitivity ratio in pregnant women at delivery. Br J Haematol 1996; 92:244–246.

- Post MS, Rosing J, Van Der Mooren MJ, et al; Ageing Women’ and the Institute for Cardiovascular Research-Vrije Universiteit (ICaRVU). Increased resistance to activated protein C after short-term oral hormone replacement therapy in healthy post-menopausal women. Br J Haematol 2002; 119:1017–1023.

- Olivieri O, Friso S, Manzato F, et al. Resistance to activated protein C in healthy women taking oral contraceptives. Br J Haematol 1995; 91:465–470.

- Bokarewa MI, Blombäck M, Egberg N, Rosén S. A new variant of interaction between phospholipid antibodies and the protein C system. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis 1994; 5:37–41.

- Baglin T, Gray E, Greaves M, et al; British Committee for Standards in Haematology. Clinical guidelines for testing for heritable thrombophilia. Br J Haematol 2010; 149:209–220.

- van Stralen KJ, Doggen CJ, Bezemer ID, Pomp ER, Lisman T, Rosendaal FR. Mechanisms of the factor V Leiden paradox. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2008; 28:1872–1877.

- Agaoglu N, Mustafa NA, Turkyilmaz S. Prothrombotic disorders in patients with mesenteric vein thrombosis. J Invest Surg 2003; 16:299–304.

- El-Karaksy H, El-Koofy N, El-Hawary M, et al. Prevalence of factor V Leiden mutation and other hereditary thrombophilic factors in Egyptian children with portal vein thrombosis: results of a single-center case-control study. Ann Hematol 2004; 83:712–715.

- Heijmans BT, Westendorp RG, Knook DL, Kluft C, Slagboom PE. The risk of mortality and the factor V Leiden mutation in a population-based cohort. Thromb Haemost 1998; 80:607–609.

- Turkstra F, Karemaker R, Kuijer PM, Prins MH, Büller HR. Is the prevalence of the factor V Leiden mutation in patients with pulmonary embolism and deep vein thrombosis really different? Thromb Haemost 1999; 81:345–348.

- Ridker PM, Hennekens CH, Lindpaintner K, Stampfer MJ, Eisenberg PR, Miletich JP. Mutation in the gene coding for coagulation factor V and the risk of myocardial infarction, stroke, and venous thrombosis in apparently healthy men. N Engl J Med 1995; 332:912–917.

- Manten B, Westendorp RG, Koster T, Reitsma PH, Rosendaal FR. Risk factor profiles in patients with different clinical manifestations of venous thromboembolism: a focus on the factor V Leiden mutation. Thromb Haemost 1996; 76:510–513.

- Blom JW, Doggen CJ, Osanto S, Rosendaal FR. Malignancies, prothrombotic mutations, and the risk of venous thrombosis. JAMA 2005; 293:715–722.

- Bloemenkamp KW, Rosendaal FR, Helmerhorst FM, Büller HR, Vandenbroucke JP. Enhancement by factor V Leiden mutation of risk of deep-vein thrombosis associated with oral contraceptives containing a third-generation progestagen. Lancet 1995; 346:1593–1596.

- Murphy PT. Factor V Leiden and venous thromboembolism. Ann Intern Med 2004; 141:483–484.

- Nizankowska-Mogilnicka E, Adamek L, Grzanka P, et al. Genetic polymorphisms associated with acute pulmonary embolism and deep venous thrombosis. Eur Respir J 2003; 21:25–30.

- Arsov T, Miladinova D, Spiroski M. Factor V Leiden is associated with higher risk of deep venous thrombosis of large blood vessels. Croat Med J 2006; 47:433–439.

- Simioni P, Prandoni P, Lensing AW, et al. Risk for subsequent venous thromboembolic complications in carriers of the prothrombin or the factor V gene mutation with a first episode of deep-vein thrombosis. Blood 2000; 96:3329–3333.

- Ornstein DL, Cushman M. Cardiology patient page. Factor V Leiden. Circulation 2003; 107:e94–e97.

- Bezemer ID, van der Meer FJ, Eikenboom JC, Rosendaal FR, Doggen CJ. The value of family history as a risk indicator for venous thrombosis. Arch Intern Med 2009; 169:610–615.

- Press RD, Bauer KA, Kujovich JL, Heit JA. Clinical utility of factor V leiden (R506Q) testing for the diagnosis and management of thromboembolic disorders. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2002; 126:1304–1318.

- Gadelha T, Roldán V, Lecumberri R, et al; RIETE Investigators. Clinical characteristics of patients with factor V Leiden or prothrombin G20210A and a first episode of venous thromboembolism. Findings from the RIETE Registry. Thromb Res 2010; 126:283–286.

- Severinsen MT, Overvad K, Johnsen SP, et al. Genetic susceptibility, smoking, obesity and risk of venous thromboembolism. Br J Haematol 2010; 149:273–279.

- Kujovich JL. Factor V Leiden thrombophilia. Genet Med 2011; 13:1–16.

- Lijfering WM, Brouwer JL, Veeger NJ, et al. Selective testing for thrombophilia in patients with first venous thrombosis: results from a retrospective family cohort study on absolute thrombotic risk for currently known thrombophilic defects in 2479 relatives. Blood 2009; 113:5314–5322.

- Kearon C, Julian JA, Kovacs MJ, et al; ELATE Investigators. Influence of thrombophilia on risk of recurrent venous thromboembolism while on warfarin: results from a randomized trial. Blood 2008; 112:4432–4436.

- Ho WK, Hankey GJ, Quinlan DJ, Eikelboom JW. Risk of recurrent venous thromboembolism in patients with common thrombophilia: a systematic review. Arch Intern Med 2006; 166:729–736.

- Christiansen SC, Cannegieter SC, Koster T, Vandenbroucke JP, Rosendaal FR. Thrombophilia, clinical factors, and recurrent venous thrombotic events. JAMA 2005; 293:2352–2361.

- Strobl FJ, Hoffman S, Huber S, Williams EC, Voelkerding KV. Activated protein C resistance assay performance: improvement by sample dilution with factor V-deficient plasma. Arch Pathol Lab Med 1998; 122:430–433.

- Legnani C, Palareti G, Biagi R, et al. Activated protein C resistance: a comparison between two clotting assays and their relationship to the presence of the factor V Leiden mutation. Br J Haematol 1996; 93:694–699.

- Gouault-Heilmann M, Leroy-Matheron C. Factor V Leiden-dependent APC resistance: improved sensitivity and specificity of the APC resistance test by plasma dilution in factor V-depleted plasma. Thromb Res 1996; 82:281–283.

- Svensson PJ, Zöller B, Dahlbäck B. Evaluation of original and modified APC-resistance tests in unselected outpatients with clinically suspected thrombosis and in healthy controls. Thromb Haemost 1997; 77:332–335.

- Tripodi A, Negri B, Bertina RM, Mannucci PM. Screening for the FV:Q506 mutation—evaluation of thirteen plasma-based methods for their diagnostic efficacy in comparison with DNA analysis. Thromb Haemost 1997; 77:436–439.

- Wåhlander K, Larson G, Lindahl TL, et al. Factor V Leiden (G1691A) and prothrombin gene G20210A mutations as potential risk factors for venous thromboembolism after total hip or total knee replacement surgery. Thromb Haemost 2002; 87:580–585.

- Joseph JE, Low J, Courtenay B, Neil MJ, McGrath M, Ma D. A single-centre prospective study of clinical and haemostatic risk factors for venous thromboembolism following lower limb arthroplasty. Br J Haematol 2005; 129:87–92.

- Geerts WH, Bergqvist D, Pineo GF, et al; American College of Chest Physicians. Prevention of venous thromboembolism: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines (8th Edition). Chest 2008; 133(suppl 6):381S–453S.

- Brenner B. Prophylaxis for travel-related thrombosis? Yes. J Thromb Haemost 2004; 2:2089–2091.

- Gavish I, Brenner B. Air travel and the risk of thromboembolism. Intern Emerg Med 2011; 6:113–116.

- Grody WW, Griffin JH, Taylor AK, Korf BR, Heit JA; ACMG Factor V Leiden Working Group. American College of Medical Genetics consensus statement on factor V Leiden mutation testing. Genet Med 2001; 3:139–148.

A 29-year-old white man with no chronic medical problems presents to the emergency department with shortness of breath, left-sided pleuritic chest pain, cough, and hemoptysis. These symptoms began abruptly 1 day ago and have persisted. He also has mild pain and swelling in both calves. He denies having any fever, night sweats, or chills. On further questioning, he reports having taken a long, nonstop driving trip that lasted 8 hours 1 week ago.

His medical history is negative, and he specifically reports no history of deep venous thrombosis or pulmonary embolism. He underwent appendectomy 10 years ago but has had no other operations. He does not take any medications. His family history is noncontributory and is negative for venous thromboembolism. He smokes and uses alcohol occasionally but not illicit drugs.

Examination. He appears to be in considerable distress because of his chest pain. His temperature is 100.4°F (38.0°C), blood pressure 125/70 mm Hg, heart rate 125 beats per minute, respiratory rate 26 breaths per minute, oxygen saturation 92% on room air, and body mass index 19 kg/m2.

Chest examination reveals diminished vesicular breathing in the left base, which is normal to percussion without added sounds. Both calves are swollen and tender to palpation without skin discoloration. The rest of his examination is normal.

Laboratory values:

- White blood cell count 9.3 × 109/L (reference range 4.5–11.0)

- Hemoglobin 15.9 g/dL (14.0–17.5)

- Platelets 205 × 109/L (150–350)

- Sodium 140 mEq/L (136–142)

- Potassium 3.9 mEq/L (3.5–5.0)

- Chloride 108 mEq/L (96–106)

- Bicarbonate 23 mEq/L (21–28)

- Blood urea nitrogen 14 mg/dL (8–23)

- Creatinine 0.9 mg/dL (0.6–1.2)

- Glucose 95 mg/dL (70–110)

- International normalized ratio (INR) 0.90 (0.00–1.2)

- Partial thromboplastin time 27.5 seconds (24.6–31.8)

- Creatine phosphokinase 205 U/L (39–308)

- Troponin T < 0.015 ng/mL (0.01–0.045).

Pulmonary embolism is diagnosed

Factor V Leiden is diagnosed, and the patient recovers with treatment

Anticoagulation is started in the emergency department.

Given this patient’s young age and clot burden, a hypercoagulable state is suspected. Thrombophilia screening is performed, with tests for the factor V Leiden mutation, the prothrombin G20210A mutation, and antiphospholipid and lupus anticoagulant antibodies. The rest of the thrombophilia panel, including antithrombin III, factor VIII, protein C, and protein S, is deferred because the levels of these substances would be expected to change during the acute thrombosis.

The direct test for factor V Leiden mutation is positive for the heterozygous type. The test for the prothrombin G20210A mutation is negative, and his antiphospholipid antibody levels, including the lupus anticoagulant titer, are within normal limits.

The patient is kept on a standard regimen of unfractionated heparin, overlapped with warfarin (Coumadin) until his INR is 2.0 to 3.0 on 2 consecutive days. His hospital course is uneventful and his condition gradually improves.

He is discharged home to continue on oral anticoagulation for 6 months with a target INR of 2.0 to 3.0. Two weeks after completing his anticoagulation therapy, his levels of antithrombin III, factor VIII, protein C, and protein S are all within normal limits.

FACTOR V LEIDEN IS COMMON

Factor V Leiden is the most common inherited thrombophilia, with a prevalence of 3% to 7% in the general US population,1 approximately 5% in whites, 2.2% in Hispanics, and 1.2% in blacks.2 Its prevalence in patients with venous thromboembolism, however, is 50%.1,3 The annual incidence of venous thromboembolism in patients with factor V Leiden is 0.5%.4,5

MORE COAGULATION, LESS ANTICOAGULATION

Factor V has a critical position in both the coagulant and anticoagulant pathways. Factor V Leiden results in a hypercoagulable state by both increasing coagulation and decreasing anticoagulation.

This mutation causes factor V to be resistant to being cleaved and inactivated by activated protein C, a condition known as APC resistance. As a result, more factor Va is available within the prothrombinase complex, increasing coagulation by increased generation of thrombin.6–8

Furthermore, a cofactor formed by cleavage of factor V at position 506 is thought to support activated protein C in degrading factor VIIIa (in the tenase complex), along with protein S. People with factor V Leiden lack this cleavage product and thus have less anticoagulant activity from activated protein C. The increased coagulation and decreased anticoagulation appear to contribute equally to the hypercoagulable state in factor V Leiden-associated APC resistance.9–11

Heterozygosity for the factor V Leiden mutation accounts for 90% to 95% of cases of APC resistance. A much smaller number of people are homozygous for it.1

People who are homozygous for factor V Leiden are at higher risk of venous thromboembolism than those who are heterozygous for it, since the latter group’s blood contains both factor V Leiden and normal factor V. The normal factor V allows anticoagulation via the second pathway of inactivation of factor VIIIa by activated protein C, giving some protection against thrombosis. In people who are homozygous for factor V Leiden, the lack of normal factor V acting as an anticoagulant protein results in a higher thrombotic risk.9–11

Other factor V mutations may also cause APC resistance

Although factor V Leiden is the only genetic defect for which a causal relationship with APC resistance has been clearly determined, other, rarer hereditary factor V mutations or polymorphisms have been described, such as factor V Cambridge (Arg306Thr)12 and factor V Hong Kong (Arg306Gly).13 These mutations may result in APC resistance, but their clinical association with thrombosis is less clear.14 Factor V Liverpool (Ile359Thr) is associated with a higher risk of thrombosis, apparently because of reduced APC-mediated inactivation of factor Va and because it is a poor cofactor with activated protein C for the inactivation of factor VIIIa.15

An R2 haplotype has also been described in association with APC resistance.16,17 The phenomenon may be due to a reduction in activated protein C cofactor activity.9 However, not all studies have been convincing regarding the role of this haplotype in clinical disease.18 Coinheritance of this haplotype with factor V Leiden may increase the risk of venous thromboembolism above that associated with factor V Leiden alone.19

Although factor V Leiden is the most common cause of inherited APC resistance, other changes in hemostasis cause acquired APC resistance and may contribute to the thrombotic tendency in these patients.20–22 The most common causes of acquired APC resistance include elevated factor VIII levels,23–25 pregnancy,26–28 use of oral contraceptives,29,30 and antiphospholipid antibodies.31

USUALLY MANIFESTS AS DEEP VEIN THROMBOSIS

Factor V Leiden usually manifests as deep vein thrombosis with or without pulmonary embolism, but thrombosis in unusual locations also occurs.32

The risk of a first episode of venous thromboembolism is two to five times higher with heterozygous factor V Leiden. However, even though the relative risk is high, the absolute risk is low. Furthermore, despite the higher risk of venous thrombosis, there is no evidence that heterozygosity for factor V Leiden increases the overall mortality rate.4,33–36

In people with homozygous factor V Leiden or with combined inherited thrombophilias, the risk of venous thromboembolism is increased to a greater degree: it is 20 to 50 times higher.7,8,37–39 However, whether the risk of death is higher is not clear.

VENOUS THROMBOEMBOLISM IS MULTIFACTORIAL

The pathogenesis of venous thromboembolism is multifactorial and involves an interaction between inherited and acquired factors. Very often, people with factor V Leiden have additional risk factors that contribute to the development of venous clots, and it is very unusual for them to have thrombosis in the absence of these additional factors.

These factors include older age, surgery, obesity, prolonged travel, immobility, hospitalization, oral contraceptive use, hormonal replacement therapy, pregnancy, and malignancy. They increase the risk of venous thrombosis in normal individuals as well, but more so in people with factor V Leiden.40–43

Testing for other known causes of thrombophilia may also be pursued. These include elevated homocysteine levels, the factor II (prothrombin) G20210A mutation, anticardiolipin antibody, lupus anticoagulant, and deficiencies of antithrombin III, protein C, and protein S.

Factor V Leiden by itself does not appear to increase the risk of arterial thrombosis, ie, heart attack and stroke.33,38,44–46

Family history: A risk indicator for venous thrombosis

Family history is an important indicator of risk for a first venous thromboembolic event, regardless of other risk factors identified. The risk of a first event is two to three times higher in people with a family history of thrombosis in a first-degree relative. The risk is four times higher when multiple family members are affected, at least one of them before age 50.47

In people with genetic thrombophilia, the risk of thrombosis (especially unprovoked thrombosis at a young age) is also higher in those with a strong family history than in those without a family history. In those with factor V Leiden, the risk of venous thromboembolism is three to four times higher if there is a positive family history. The risk is five times higher in carriers of factor V Leiden with a family history of venous thromboembolism before age 50, and 13 times higher in those with more than one affected family member.47

Possible shared environmental factors or coinheritance of other unidentified genetic factors may also contribute to the higher susceptibility in thrombosis-prone families.

TESTING FOR APC RESISTANCE AND FACTOR V LEIDEN

The factor V Leiden mutation can be detected directly by genetic testing of peripheral blood mononuclear cells. This method is relatively time-consuming and expensive, however.

At present, the most cost-effective approach is to test first for APC resistance using a second-generation coagulation assay—the modified APC sensitivity test. In this clot-based method, the patient’s sample is prediluted with factor V-deficient plasma to eliminate the effect of lupus anticoagulants and factor deficiencies that could prolong the baseline clotting time, and heparin is inactivated by polybrene. Then either an augmented partial-thromboplastin-time-based assay or a tissue-factor-dependent factor V assay is performed.

This test is nearly 100% sensitive and specific for factor V Leiden, in contrast to the first-generation, or classic, APC sensitivity test, which lacked specificity and sensitivity for it.9–11,48–60 This modification also permits testing of patients receiving anticoagulants or who have abnormal augmented partial thromboplastin times due to coagulation factor deficiencies.

A positive result on the modified APC sensitivity test should be confirmed by a direct genetic test for the factor V Leiden mutation. An APC resistance assay is unnecessary if a direct genetic test is used initially.

HOW LONG TO GIVE ANTICOAGULATION AFTER VENOUS THROMBOEMBOLISM?

Patients who have had an episode of venous thromboembolism have to be treated with anticoagulants.

In general, the initial management of venous thromboembolism in patients with heritable thrombophilias is no different from that in any other patient with a clot. Anticoagulants such as warfarin are given at a target INR of 2.5 (range 2.0–3.0).32 The duration of treatment is based on the risk factors that resulted in the thrombotic event.

After a first event, some authorities recommend anticoagulant therapy for 6 months.32 A shorter period (3 months) is recommended if there is a transient risk factor (eg, surgery, oral contraceptive use, travel, pregnancy, the puerperium) and the thrombosis is confined to distal veins (eg, the calf veins).32

Factor V Leiden does not necessarily increase the risk of recurrent events in patients who have a transient risk factor. Therefore, people who are heterozygous for this mutation do not usually need to be treated lifelong with anticoagulants if they have had only one episode of deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism, given the risk of bleeding associated with anticoagulation, unless they have additional risk factors.

Conditions in which indefinite anticoagulation may be required after careful consideration of the risks and benefits are:

- Life-threatening events such as near-fatal pulmonary embolism

- Cerebral or visceral vein thrombosis

- Recurrent thrombotic events

- Additional persistent risk factors (eg, active malignant neoplasm, extremity paresis, and antiphospholipid antibodies)

- Combined thrombophilias (eg, combined heterozygosity for factor V Leiden and the prothrombin G20210A mutation)

- Homozygosity for factor V Leiden.32,46,48

Factor V Leiden by itself or combined with other thrombophilic abnormalities is not associated with a higher risk of recurrent venous thromboembolism during warfarin therapy (a possible exception is the combination of factor V Leiden plus antiphospholipid antibodies).32,34 Furthermore, current evidence suggests that no thrombophilic defect is a clinically important risk factor for recurrent venous thromboembolism after anticoagulant therapy is stopped. All these facts indicate that clinical factors are probably more important than laboratory abnormalities in determining the duration of anticoagulation therapy.32,35,36,61–63

PRIMARY PROPHYLAXIS IN PATIENTS WITH FACTOR V LEIDEN

Factor V Leiden is only one of many risk factors for deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism. If carriers of factor V Leiden have never had a blood clot, then they are not routinely treated with an anticoagulant. Rather, they should be counseled about reducing or eliminating other factors that may add to their risk of developing a clot in the future.

Usually, the effect of risk factors is additive: the more risk factors present, the higher the risk.46,50 Sometimes, however, the effect of multiple risk factors is more than additive.

Some risk factors, such as genetics or age, are not alterable, but many can be controlled by medications or lifestyle modifications. Therefore, general measures and precautions are recommended to minimize the risk of thrombosis. For example:

Losing weight (if the patient is overweight) is an important intervention for risk reduction, since obesity is probably the most common modifiable risk factor for developing blood clots.

Avoiding long periods of immobility is recommended. For example, if the patient is taking a long car ride (more than 2 hours), then stopping every few hours and walking around for a few minutes is a good way to keep the blood circulating. If the patient has a desk job, getting up and walking around the office periodically is advised. On long airplane trips, a walk in the aisle every so often and preventing dehydration by drinking plenty of fluids and avoiding alcohol are recommended.

Wearing elastic stockings with a graduated elastic pressure may prevent deep venous thrombosis from developing on long flights.63–65

Staying active and getting regular exercise through such activities as walking, bicycling, or swimming are helpful.

Avoiding smoking is critical.50,63

Thromboprophylaxis is recommended for most acutely ill hospitalized patients, especially those confined to bed with additional risk factors. Guidelines for prophylaxis are based on an individualized risk assessment and not on thrombophilia status. Prophylactic anticoagulation is routinely recommended for patients undergoing major high-risk surgery, such as an orthopedic, urologic, gynecologic, or bariatric procedure. Any excess thrombotic risk conferred by thrombophilia is likely small compared with the risk of surgery, and recommendations on the duration and intensity of thromboprophylaxis are not based on thrombophilic status.46,48

Education. Pain, swelling, redness of a limb, unexplained shortness of breath, and chest pain are the most common symptoms of deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism.46,50 It is crucial to teach patients with factor V Leiden to recognize these symptoms and to seek early medical attention in case they experience any of them.

SCREENING FAMILY MEMBERS FOR THE FACTOR V LEIDEN MUTATION

Factor V Leiden by itself is a relatively mild thrombophilic defect that does not cause thrombosis in all carriers, and there is no evidence that early diagnosis reduces rates of morbidity or mortality. Therefore, routine screening of all asymptomatic relatives of affected patients with venous thrombosis is not recommended. Rather, the decision to screen should be made on an individual basis.50,66

Screening may be beneficial in selected cases, especially when patients have a strong family history of recurrent venous thrombosis at a young age (younger than 50 years) and the family member has additional risk factors for venous thromboembolism such as oral contraception or is planning for pregnancy.32,48,49,66

A 29-year-old white man with no chronic medical problems presents to the emergency department with shortness of breath, left-sided pleuritic chest pain, cough, and hemoptysis. These symptoms began abruptly 1 day ago and have persisted. He also has mild pain and swelling in both calves. He denies having any fever, night sweats, or chills. On further questioning, he reports having taken a long, nonstop driving trip that lasted 8 hours 1 week ago.

His medical history is negative, and he specifically reports no history of deep venous thrombosis or pulmonary embolism. He underwent appendectomy 10 years ago but has had no other operations. He does not take any medications. His family history is noncontributory and is negative for venous thromboembolism. He smokes and uses alcohol occasionally but not illicit drugs.

Examination. He appears to be in considerable distress because of his chest pain. His temperature is 100.4°F (38.0°C), blood pressure 125/70 mm Hg, heart rate 125 beats per minute, respiratory rate 26 breaths per minute, oxygen saturation 92% on room air, and body mass index 19 kg/m2.

Chest examination reveals diminished vesicular breathing in the left base, which is normal to percussion without added sounds. Both calves are swollen and tender to palpation without skin discoloration. The rest of his examination is normal.

Laboratory values:

- White blood cell count 9.3 × 109/L (reference range 4.5–11.0)

- Hemoglobin 15.9 g/dL (14.0–17.5)

- Platelets 205 × 109/L (150–350)

- Sodium 140 mEq/L (136–142)

- Potassium 3.9 mEq/L (3.5–5.0)

- Chloride 108 mEq/L (96–106)

- Bicarbonate 23 mEq/L (21–28)

- Blood urea nitrogen 14 mg/dL (8–23)

- Creatinine 0.9 mg/dL (0.6–1.2)

- Glucose 95 mg/dL (70–110)

- International normalized ratio (INR) 0.90 (0.00–1.2)

- Partial thromboplastin time 27.5 seconds (24.6–31.8)

- Creatine phosphokinase 205 U/L (39–308)

- Troponin T < 0.015 ng/mL (0.01–0.045).

Pulmonary embolism is diagnosed

Factor V Leiden is diagnosed, and the patient recovers with treatment

Anticoagulation is started in the emergency department.

Given this patient’s young age and clot burden, a hypercoagulable state is suspected. Thrombophilia screening is performed, with tests for the factor V Leiden mutation, the prothrombin G20210A mutation, and antiphospholipid and lupus anticoagulant antibodies. The rest of the thrombophilia panel, including antithrombin III, factor VIII, protein C, and protein S, is deferred because the levels of these substances would be expected to change during the acute thrombosis.

The direct test for factor V Leiden mutation is positive for the heterozygous type. The test for the prothrombin G20210A mutation is negative, and his antiphospholipid antibody levels, including the lupus anticoagulant titer, are within normal limits.

The patient is kept on a standard regimen of unfractionated heparin, overlapped with warfarin (Coumadin) until his INR is 2.0 to 3.0 on 2 consecutive days. His hospital course is uneventful and his condition gradually improves.

He is discharged home to continue on oral anticoagulation for 6 months with a target INR of 2.0 to 3.0. Two weeks after completing his anticoagulation therapy, his levels of antithrombin III, factor VIII, protein C, and protein S are all within normal limits.

FACTOR V LEIDEN IS COMMON

Factor V Leiden is the most common inherited thrombophilia, with a prevalence of 3% to 7% in the general US population,1 approximately 5% in whites, 2.2% in Hispanics, and 1.2% in blacks.2 Its prevalence in patients with venous thromboembolism, however, is 50%.1,3 The annual incidence of venous thromboembolism in patients with factor V Leiden is 0.5%.4,5

MORE COAGULATION, LESS ANTICOAGULATION

Factor V has a critical position in both the coagulant and anticoagulant pathways. Factor V Leiden results in a hypercoagulable state by both increasing coagulation and decreasing anticoagulation.

This mutation causes factor V to be resistant to being cleaved and inactivated by activated protein C, a condition known as APC resistance. As a result, more factor Va is available within the prothrombinase complex, increasing coagulation by increased generation of thrombin.6–8

Furthermore, a cofactor formed by cleavage of factor V at position 506 is thought to support activated protein C in degrading factor VIIIa (in the tenase complex), along with protein S. People with factor V Leiden lack this cleavage product and thus have less anticoagulant activity from activated protein C. The increased coagulation and decreased anticoagulation appear to contribute equally to the hypercoagulable state in factor V Leiden-associated APC resistance.9–11

Heterozygosity for the factor V Leiden mutation accounts for 90% to 95% of cases of APC resistance. A much smaller number of people are homozygous for it.1

People who are homozygous for factor V Leiden are at higher risk of venous thromboembolism than those who are heterozygous for it, since the latter group’s blood contains both factor V Leiden and normal factor V. The normal factor V allows anticoagulation via the second pathway of inactivation of factor VIIIa by activated protein C, giving some protection against thrombosis. In people who are homozygous for factor V Leiden, the lack of normal factor V acting as an anticoagulant protein results in a higher thrombotic risk.9–11

Other factor V mutations may also cause APC resistance

Although factor V Leiden is the only genetic defect for which a causal relationship with APC resistance has been clearly determined, other, rarer hereditary factor V mutations or polymorphisms have been described, such as factor V Cambridge (Arg306Thr)12 and factor V Hong Kong (Arg306Gly).13 These mutations may result in APC resistance, but their clinical association with thrombosis is less clear.14 Factor V Liverpool (Ile359Thr) is associated with a higher risk of thrombosis, apparently because of reduced APC-mediated inactivation of factor Va and because it is a poor cofactor with activated protein C for the inactivation of factor VIIIa.15

An R2 haplotype has also been described in association with APC resistance.16,17 The phenomenon may be due to a reduction in activated protein C cofactor activity.9 However, not all studies have been convincing regarding the role of this haplotype in clinical disease.18 Coinheritance of this haplotype with factor V Leiden may increase the risk of venous thromboembolism above that associated with factor V Leiden alone.19

Although factor V Leiden is the most common cause of inherited APC resistance, other changes in hemostasis cause acquired APC resistance and may contribute to the thrombotic tendency in these patients.20–22 The most common causes of acquired APC resistance include elevated factor VIII levels,23–25 pregnancy,26–28 use of oral contraceptives,29,30 and antiphospholipid antibodies.31

USUALLY MANIFESTS AS DEEP VEIN THROMBOSIS

Factor V Leiden usually manifests as deep vein thrombosis with or without pulmonary embolism, but thrombosis in unusual locations also occurs.32

The risk of a first episode of venous thromboembolism is two to five times higher with heterozygous factor V Leiden. However, even though the relative risk is high, the absolute risk is low. Furthermore, despite the higher risk of venous thrombosis, there is no evidence that heterozygosity for factor V Leiden increases the overall mortality rate.4,33–36

In people with homozygous factor V Leiden or with combined inherited thrombophilias, the risk of venous thromboembolism is increased to a greater degree: it is 20 to 50 times higher.7,8,37–39 However, whether the risk of death is higher is not clear.

VENOUS THROMBOEMBOLISM IS MULTIFACTORIAL

The pathogenesis of venous thromboembolism is multifactorial and involves an interaction between inherited and acquired factors. Very often, people with factor V Leiden have additional risk factors that contribute to the development of venous clots, and it is very unusual for them to have thrombosis in the absence of these additional factors.

These factors include older age, surgery, obesity, prolonged travel, immobility, hospitalization, oral contraceptive use, hormonal replacement therapy, pregnancy, and malignancy. They increase the risk of venous thrombosis in normal individuals as well, but more so in people with factor V Leiden.40–43

Testing for other known causes of thrombophilia may also be pursued. These include elevated homocysteine levels, the factor II (prothrombin) G20210A mutation, anticardiolipin antibody, lupus anticoagulant, and deficiencies of antithrombin III, protein C, and protein S.

Factor V Leiden by itself does not appear to increase the risk of arterial thrombosis, ie, heart attack and stroke.33,38,44–46

Family history: A risk indicator for venous thrombosis

Family history is an important indicator of risk for a first venous thromboembolic event, regardless of other risk factors identified. The risk of a first event is two to three times higher in people with a family history of thrombosis in a first-degree relative. The risk is four times higher when multiple family members are affected, at least one of them before age 50.47

In people with genetic thrombophilia, the risk of thrombosis (especially unprovoked thrombosis at a young age) is also higher in those with a strong family history than in those without a family history. In those with factor V Leiden, the risk of venous thromboembolism is three to four times higher if there is a positive family history. The risk is five times higher in carriers of factor V Leiden with a family history of venous thromboembolism before age 50, and 13 times higher in those with more than one affected family member.47

Possible shared environmental factors or coinheritance of other unidentified genetic factors may also contribute to the higher susceptibility in thrombosis-prone families.

TESTING FOR APC RESISTANCE AND FACTOR V LEIDEN

The factor V Leiden mutation can be detected directly by genetic testing of peripheral blood mononuclear cells. This method is relatively time-consuming and expensive, however.

At present, the most cost-effective approach is to test first for APC resistance using a second-generation coagulation assay—the modified APC sensitivity test. In this clot-based method, the patient’s sample is prediluted with factor V-deficient plasma to eliminate the effect of lupus anticoagulants and factor deficiencies that could prolong the baseline clotting time, and heparin is inactivated by polybrene. Then either an augmented partial-thromboplastin-time-based assay or a tissue-factor-dependent factor V assay is performed.

This test is nearly 100% sensitive and specific for factor V Leiden, in contrast to the first-generation, or classic, APC sensitivity test, which lacked specificity and sensitivity for it.9–11,48–60 This modification also permits testing of patients receiving anticoagulants or who have abnormal augmented partial thromboplastin times due to coagulation factor deficiencies.

A positive result on the modified APC sensitivity test should be confirmed by a direct genetic test for the factor V Leiden mutation. An APC resistance assay is unnecessary if a direct genetic test is used initially.

HOW LONG TO GIVE ANTICOAGULATION AFTER VENOUS THROMBOEMBOLISM?

Patients who have had an episode of venous thromboembolism have to be treated with anticoagulants.

In general, the initial management of venous thromboembolism in patients with heritable thrombophilias is no different from that in any other patient with a clot. Anticoagulants such as warfarin are given at a target INR of 2.5 (range 2.0–3.0).32 The duration of treatment is based on the risk factors that resulted in the thrombotic event.

After a first event, some authorities recommend anticoagulant therapy for 6 months.32 A shorter period (3 months) is recommended if there is a transient risk factor (eg, surgery, oral contraceptive use, travel, pregnancy, the puerperium) and the thrombosis is confined to distal veins (eg, the calf veins).32

Factor V Leiden does not necessarily increase the risk of recurrent events in patients who have a transient risk factor. Therefore, people who are heterozygous for this mutation do not usually need to be treated lifelong with anticoagulants if they have had only one episode of deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism, given the risk of bleeding associated with anticoagulation, unless they have additional risk factors.

Conditions in which indefinite anticoagulation may be required after careful consideration of the risks and benefits are:

- Life-threatening events such as near-fatal pulmonary embolism

- Cerebral or visceral vein thrombosis

- Recurrent thrombotic events

- Additional persistent risk factors (eg, active malignant neoplasm, extremity paresis, and antiphospholipid antibodies)

- Combined thrombophilias (eg, combined heterozygosity for factor V Leiden and the prothrombin G20210A mutation)

- Homozygosity for factor V Leiden.32,46,48

Factor V Leiden by itself or combined with other thrombophilic abnormalities is not associated with a higher risk of recurrent venous thromboembolism during warfarin therapy (a possible exception is the combination of factor V Leiden plus antiphospholipid antibodies).32,34 Furthermore, current evidence suggests that no thrombophilic defect is a clinically important risk factor for recurrent venous thromboembolism after anticoagulant therapy is stopped. All these facts indicate that clinical factors are probably more important than laboratory abnormalities in determining the duration of anticoagulation therapy.32,35,36,61–63

PRIMARY PROPHYLAXIS IN PATIENTS WITH FACTOR V LEIDEN

Factor V Leiden is only one of many risk factors for deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism. If carriers of factor V Leiden have never had a blood clot, then they are not routinely treated with an anticoagulant. Rather, they should be counseled about reducing or eliminating other factors that may add to their risk of developing a clot in the future.

Usually, the effect of risk factors is additive: the more risk factors present, the higher the risk.46,50 Sometimes, however, the effect of multiple risk factors is more than additive.

Some risk factors, such as genetics or age, are not alterable, but many can be controlled by medications or lifestyle modifications. Therefore, general measures and precautions are recommended to minimize the risk of thrombosis. For example:

Losing weight (if the patient is overweight) is an important intervention for risk reduction, since obesity is probably the most common modifiable risk factor for developing blood clots.

Avoiding long periods of immobility is recommended. For example, if the patient is taking a long car ride (more than 2 hours), then stopping every few hours and walking around for a few minutes is a good way to keep the blood circulating. If the patient has a desk job, getting up and walking around the office periodically is advised. On long airplane trips, a walk in the aisle every so often and preventing dehydration by drinking plenty of fluids and avoiding alcohol are recommended.

Wearing elastic stockings with a graduated elastic pressure may prevent deep venous thrombosis from developing on long flights.63–65

Staying active and getting regular exercise through such activities as walking, bicycling, or swimming are helpful.

Avoiding smoking is critical.50,63

Thromboprophylaxis is recommended for most acutely ill hospitalized patients, especially those confined to bed with additional risk factors. Guidelines for prophylaxis are based on an individualized risk assessment and not on thrombophilia status. Prophylactic anticoagulation is routinely recommended for patients undergoing major high-risk surgery, such as an orthopedic, urologic, gynecologic, or bariatric procedure. Any excess thrombotic risk conferred by thrombophilia is likely small compared with the risk of surgery, and recommendations on the duration and intensity of thromboprophylaxis are not based on thrombophilic status.46,48

Education. Pain, swelling, redness of a limb, unexplained shortness of breath, and chest pain are the most common symptoms of deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism.46,50 It is crucial to teach patients with factor V Leiden to recognize these symptoms and to seek early medical attention in case they experience any of them.

SCREENING FAMILY MEMBERS FOR THE FACTOR V LEIDEN MUTATION

Factor V Leiden by itself is a relatively mild thrombophilic defect that does not cause thrombosis in all carriers, and there is no evidence that early diagnosis reduces rates of morbidity or mortality. Therefore, routine screening of all asymptomatic relatives of affected patients with venous thrombosis is not recommended. Rather, the decision to screen should be made on an individual basis.50,66

Screening may be beneficial in selected cases, especially when patients have a strong family history of recurrent venous thrombosis at a young age (younger than 50 years) and the family member has additional risk factors for venous thromboembolism such as oral contraception or is planning for pregnancy.32,48,49,66

- Rees DC, Cox M, Clegg JB. World distribution of factor V Leiden. Lancet 1995; 346:1133–1134.

- Ridker PM, Miletich JP, Hennekens CH, Buring JE. Ethnic distribution of factor V Leiden in 4047 men and women. Implications for venous thromboembolism screening. JAMA 1997; 277:1305–1307.

- Rosendaal FR, Koster T, Vandenbroucke JP, Reitsma PH. High risk of thrombosis in patients homozygous for factor V Leiden (activated protein C resistance). Blood 1995; 85:1504–1508.

- Stolz E, Kemkes-Matthes B, Pötzsch B, et al. Screening for thrombophilic risk factors among 25 German patients with cerebral venous thrombosis. Acta Neurol Scand 2000; 102:31–36.

- Langlois NJ, Wells PS. Risk of venous thromboembolism in relatives of symptomatic probands with thrombophilia: a systematic review. Thromb Haemost 2003; 90:17–26.

- Juul K, Tybjaerg-Hansen A, Mortensen J, Lange P, Vestbo J, Nordestgaard BG. Factor V leiden homozygosity, dyspnea, and reduced pulmonary function. Arch Intern Med 2005; 165:2032–2036.

- Bertina RM, Koeleman BP, Koster T, et al. Mutation in blood coagulation factor V associated with resistance to activated protein C. Nature 1994; 369:64–67.

- Dahlbäck B. New molecular insights into the genetics of thrombophilia. Resistance to activated protein C caused by Arg506 to Gln mutation in factor V as a pathogenic risk factor for venous thrombosis. Thromb Haemost 1995; 74:139–148.

- Castoldi E, Brugge JM, Nicolaes GA, Girelli D, Tans G, Rosing J. Impaired APC cofactor activity of factor V plays a major role in the APC resistance associated with the factor V Leiden (R506Q) and R2 (H1299R) mutations. Blood 2004; 103:4173–4179.

- Dahlback B. Anticoagulant factor V and thrombosis risk (editorial). Blood 2004; 103:3995.

- Simioni P, Castoldi E, Lunghi B, Tormene D, Rosing J, Bernardi F. An underestimated combination of opposites resulting in enhanced thrombotic tendency. Blood 2005; 106:2363–2365.

- Williamson D, Brown K, Luddington R, Baglin C, Baglin T. Factor V Cambridge: a new mutation (Arg306-->Thr) associated with resistance to activated protein C. Blood 1998; 91:1140–1144.

- Chan WP, Lee CK, Kwong YL, Lam CK, Liang R. A novel mutation of Arg306 of factor V gene in Hong Kong Chinese. Blood 1998; 91:1135–1139.

- Liang R, Lee CK, Wat MS, Kwong YL, Lam CK, Liu HW. Clinical significance of Arg306 mutations of factor V gene. Blood 1998; 92:2599–2600.

- Steen M, Norstrøm EA, Tholander AL, et al. Functional characterization of factor V-Ile359Thr: a novel mutation associated with thrombosis. Blood 2004; 103:3381–3387.

- Bernardi F, Faioni EM, Castoldi E, et al. A factor V genetic component differing from factor V R506Q contributes to the activated protein C resistance phenotype. Blood 1997; 90:1552–1557.

- Lunghi B, Castoldi E, Mingozzi F, Bernardi F. A new factor V gene polymorphism (His 1254 Arg) present in subjects of African origin mimics the R2 polymorphism (His 1299 Arg). Blood 1998; 91:364–365.

- Luddington R, Jackson A, Pannerselvam S, Brown K, Baglin T. The factor V R2 allele: risk of venous thromboembolism, factor V levels and resistance to activated protein C. Thromb Haemost 2000; 83:204–208.

- Faioni EM, Franchi F, Bucciarelli P, et al. Coinheritance of the HR2 haplotype in the factor V gene confers an increased risk of venous thromboembolism to carriers of factor V R506Q (factor V Leiden). Blood 1999; 94:3062–3066.

- Clark P, Walker ID. The phenomenon known as acquired activated protein C resistance. Br J Haematol 2001; 115:767–773.

- Tosetto A, Simioni M, Madeo D, Rodeghiero F. Intraindividual consistency of the activated protein C resistance phenotype. Br J Haematol 2004; 126:405–409.

- de Visser MC, Rosendaal FR, Bertina RM. A reduced sensitivity for activated protein C in the absence of factor V Leiden increases the risk of venous thrombosis. Blood 1999; 93:1271–1276.

- Kraaijenhagen RA, in’t Anker PS, Koopman MM, et al. High plasma concentration of factor VIIIc is a major risk factor for venous thromboembolism. Thromb Haemost 2000; 83:5–9.

- Kamphuisen PW, Eikenboom JC, Bertina RM. Elevated factor VIII levels and the risk of thrombosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2001; 21:731–738.

- Koster T, Blann AD, Briët E, Vandenbroucke JP, Rosendaal FR. Role of clotting factor VIII in effect of von Willebrand factor on occurrence of deep-vein thrombosis. Lancet 1995; 345:152–155.

- Clark P, Brennand J, Conkie JA, McCall F, Greer IA, Walker ID. Activated protein C sensitivity, protein C, protein S and coagulation in normal pregnancy. Thromb Haemost 1998; 79:1166–1170.

- Cumming AM, Tait RC, Fildes S, Yoong A, Keeney S, Hay CR. Development of resistance to activated protein C during pregnancy. Br J Haematol 1995; 90:725–727.

- Mathonnet F, de Mazancourt P, Bastenaire B, et al. Activated protein C sensitivity ratio in pregnant women at delivery. Br J Haematol 1996; 92:244–246.

- Post MS, Rosing J, Van Der Mooren MJ, et al; Ageing Women’ and the Institute for Cardiovascular Research-Vrije Universiteit (ICaRVU). Increased resistance to activated protein C after short-term oral hormone replacement therapy in healthy post-menopausal women. Br J Haematol 2002; 119:1017–1023.

- Olivieri O, Friso S, Manzato F, et al. Resistance to activated protein C in healthy women taking oral contraceptives. Br J Haematol 1995; 91:465–470.

- Bokarewa MI, Blombäck M, Egberg N, Rosén S. A new variant of interaction between phospholipid antibodies and the protein C system. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis 1994; 5:37–41.

- Baglin T, Gray E, Greaves M, et al; British Committee for Standards in Haematology. Clinical guidelines for testing for heritable thrombophilia. Br J Haematol 2010; 149:209–220.

- van Stralen KJ, Doggen CJ, Bezemer ID, Pomp ER, Lisman T, Rosendaal FR. Mechanisms of the factor V Leiden paradox. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2008; 28:1872–1877.

- Agaoglu N, Mustafa NA, Turkyilmaz S. Prothrombotic disorders in patients with mesenteric vein thrombosis. J Invest Surg 2003; 16:299–304.

- El-Karaksy H, El-Koofy N, El-Hawary M, et al. Prevalence of factor V Leiden mutation and other hereditary thrombophilic factors in Egyptian children with portal vein thrombosis: results of a single-center case-control study. Ann Hematol 2004; 83:712–715.

- Heijmans BT, Westendorp RG, Knook DL, Kluft C, Slagboom PE. The risk of mortality and the factor V Leiden mutation in a population-based cohort. Thromb Haemost 1998; 80:607–609.

- Turkstra F, Karemaker R, Kuijer PM, Prins MH, Büller HR. Is the prevalence of the factor V Leiden mutation in patients with pulmonary embolism and deep vein thrombosis really different? Thromb Haemost 1999; 81:345–348.

- Ridker PM, Hennekens CH, Lindpaintner K, Stampfer MJ, Eisenberg PR, Miletich JP. Mutation in the gene coding for coagulation factor V and the risk of myocardial infarction, stroke, and venous thrombosis in apparently healthy men. N Engl J Med 1995; 332:912–917.

- Manten B, Westendorp RG, Koster T, Reitsma PH, Rosendaal FR. Risk factor profiles in patients with different clinical manifestations of venous thromboembolism: a focus on the factor V Leiden mutation. Thromb Haemost 1996; 76:510–513.

- Blom JW, Doggen CJ, Osanto S, Rosendaal FR. Malignancies, prothrombotic mutations, and the risk of venous thrombosis. JAMA 2005; 293:715–722.

- Bloemenkamp KW, Rosendaal FR, Helmerhorst FM, Büller HR, Vandenbroucke JP. Enhancement by factor V Leiden mutation of risk of deep-vein thrombosis associated with oral contraceptives containing a third-generation progestagen. Lancet 1995; 346:1593–1596.

- Murphy PT. Factor V Leiden and venous thromboembolism. Ann Intern Med 2004; 141:483–484.

- Nizankowska-Mogilnicka E, Adamek L, Grzanka P, et al. Genetic polymorphisms associated with acute pulmonary embolism and deep venous thrombosis. Eur Respir J 2003; 21:25–30.

- Arsov T, Miladinova D, Spiroski M. Factor V Leiden is associated with higher risk of deep venous thrombosis of large blood vessels. Croat Med J 2006; 47:433–439.

- Simioni P, Prandoni P, Lensing AW, et al. Risk for subsequent venous thromboembolic complications in carriers of the prothrombin or the factor V gene mutation with a first episode of deep-vein thrombosis. Blood 2000; 96:3329–3333.

- Ornstein DL, Cushman M. Cardiology patient page. Factor V Leiden. Circulation 2003; 107:e94–e97.

- Bezemer ID, van der Meer FJ, Eikenboom JC, Rosendaal FR, Doggen CJ. The value of family history as a risk indicator for venous thrombosis. Arch Intern Med 2009; 169:610–615.

- Press RD, Bauer KA, Kujovich JL, Heit JA. Clinical utility of factor V leiden (R506Q) testing for the diagnosis and management of thromboembolic disorders. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2002; 126:1304–1318.

- Gadelha T, Roldán V, Lecumberri R, et al; RIETE Investigators. Clinical characteristics of patients with factor V Leiden or prothrombin G20210A and a first episode of venous thromboembolism. Findings from the RIETE Registry. Thromb Res 2010; 126:283–286.

- Severinsen MT, Overvad K, Johnsen SP, et al. Genetic susceptibility, smoking, obesity and risk of venous thromboembolism. Br J Haematol 2010; 149:273–279.

- Kujovich JL. Factor V Leiden thrombophilia. Genet Med 2011; 13:1–16.

- Lijfering WM, Brouwer JL, Veeger NJ, et al. Selective testing for thrombophilia in patients with first venous thrombosis: results from a retrospective family cohort study on absolute thrombotic risk for currently known thrombophilic defects in 2479 relatives. Blood 2009; 113:5314–5322.

- Kearon C, Julian JA, Kovacs MJ, et al; ELATE Investigators. Influence of thrombophilia on risk of recurrent venous thromboembolism while on warfarin: results from a randomized trial. Blood 2008; 112:4432–4436.

- Ho WK, Hankey GJ, Quinlan DJ, Eikelboom JW. Risk of recurrent venous thromboembolism in patients with common thrombophilia: a systematic review. Arch Intern Med 2006; 166:729–736.

- Christiansen SC, Cannegieter SC, Koster T, Vandenbroucke JP, Rosendaal FR. Thrombophilia, clinical factors, and recurrent venous thrombotic events. JAMA 2005; 293:2352–2361.

- Strobl FJ, Hoffman S, Huber S, Williams EC, Voelkerding KV. Activated protein C resistance assay performance: improvement by sample dilution with factor V-deficient plasma. Arch Pathol Lab Med 1998; 122:430–433.

- Legnani C, Palareti G, Biagi R, et al. Activated protein C resistance: a comparison between two clotting assays and their relationship to the presence of the factor V Leiden mutation. Br J Haematol 1996; 93:694–699.

- Gouault-Heilmann M, Leroy-Matheron C. Factor V Leiden-dependent APC resistance: improved sensitivity and specificity of the APC resistance test by plasma dilution in factor V-depleted plasma. Thromb Res 1996; 82:281–283.

- Svensson PJ, Zöller B, Dahlbäck B. Evaluation of original and modified APC-resistance tests in unselected outpatients with clinically suspected thrombosis and in healthy controls. Thromb Haemost 1997; 77:332–335.

- Tripodi A, Negri B, Bertina RM, Mannucci PM. Screening for the FV:Q506 mutation—evaluation of thirteen plasma-based methods for their diagnostic efficacy in comparison with DNA analysis. Thromb Haemost 1997; 77:436–439.

- Wåhlander K, Larson G, Lindahl TL, et al. Factor V Leiden (G1691A) and prothrombin gene G20210A mutations as potential risk factors for venous thromboembolism after total hip or total knee replacement surgery. Thromb Haemost 2002; 87:580–585.

- Joseph JE, Low J, Courtenay B, Neil MJ, McGrath M, Ma D. A single-centre prospective study of clinical and haemostatic risk factors for venous thromboembolism following lower limb arthroplasty. Br J Haematol 2005; 129:87–92.

- Geerts WH, Bergqvist D, Pineo GF, et al; American College of Chest Physicians. Prevention of venous thromboembolism: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines (8th Edition). Chest 2008; 133(suppl 6):381S–453S.

- Brenner B. Prophylaxis for travel-related thrombosis? Yes. J Thromb Haemost 2004; 2:2089–2091.

- Gavish I, Brenner B. Air travel and the risk of thromboembolism. Intern Emerg Med 2011; 6:113–116.

- Grody WW, Griffin JH, Taylor AK, Korf BR, Heit JA; ACMG Factor V Leiden Working Group. American College of Medical Genetics consensus statement on factor V Leiden mutation testing. Genet Med 2001; 3:139–148.

- Rees DC, Cox M, Clegg JB. World distribution of factor V Leiden. Lancet 1995; 346:1133–1134.

- Ridker PM, Miletich JP, Hennekens CH, Buring JE. Ethnic distribution of factor V Leiden in 4047 men and women. Implications for venous thromboembolism screening. JAMA 1997; 277:1305–1307.

- Rosendaal FR, Koster T, Vandenbroucke JP, Reitsma PH. High risk of thrombosis in patients homozygous for factor V Leiden (activated protein C resistance). Blood 1995; 85:1504–1508.

- Stolz E, Kemkes-Matthes B, Pötzsch B, et al. Screening for thrombophilic risk factors among 25 German patients with cerebral venous thrombosis. Acta Neurol Scand 2000; 102:31–36.

- Langlois NJ, Wells PS. Risk of venous thromboembolism in relatives of symptomatic probands with thrombophilia: a systematic review. Thromb Haemost 2003; 90:17–26.

- Juul K, Tybjaerg-Hansen A, Mortensen J, Lange P, Vestbo J, Nordestgaard BG. Factor V leiden homozygosity, dyspnea, and reduced pulmonary function. Arch Intern Med 2005; 165:2032–2036.

- Bertina RM, Koeleman BP, Koster T, et al. Mutation in blood coagulation factor V associated with resistance to activated protein C. Nature 1994; 369:64–67.

- Dahlbäck B. New molecular insights into the genetics of thrombophilia. Resistance to activated protein C caused by Arg506 to Gln mutation in factor V as a pathogenic risk factor for venous thrombosis. Thromb Haemost 1995; 74:139–148.

- Castoldi E, Brugge JM, Nicolaes GA, Girelli D, Tans G, Rosing J. Impaired APC cofactor activity of factor V plays a major role in the APC resistance associated with the factor V Leiden (R506Q) and R2 (H1299R) mutations. Blood 2004; 103:4173–4179.