User login

7 tools to help patients adopt healthier behaviors

› Determine the patient’s stage of change (Precontemplation, Contemplation, Preparation, Action, Maintenance, or Relapse) before selecting an intervention to help him or her change health-related behaviors. B

› Consider using motivational interviewing or narrative techniques to help patients who aren’t yet ready to change their health-related behaviors or who plan to do so within 6 months. C

› Be aware that patients seldom become motivated to change behaviors by being given information about health risks and benefits; to overcome ambivalence, they need to focus on their core values and goals. C

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

CASE › Your patient, Bob G, age 47, has a body mass index of 33, hypertension (blood pressure 150/85 mm Hg), and elevated cholesterol (low-density lipoprotein level, 187 mg/dL) and glucose levels (fasting glucose 122 mg/dL, with an HbA1c of 6.1%). He gets out of breath when he plays with his 2 children. His father has diabetes and had a myocardial infarction (MI) at age 55; Mr. G tells you he is concerned he will develop similar health problems. Mr. G frequents fast food restaurants and eats high-calorie snacks after work, especially when he feels stressed. During a recent office visit, he expresses his desire to “be there” for his children and says he is motivated to lose weight to prevent diabetes and/or an MI.

How would you proceed?

Most health conditions in the United States are directly or indirectly the result of patients’ health-related behaviors.1 Fortunately, family physicians (FPs) and primary care teams are in an excellent position to help their patients make healthy behavior changes by using brief, evidence-based interventions that can be implemented during the typical office visit.

Specifically, the use of the following 7 techniques can build on patients’ own motivations, successes, and life circumstances to improve their satisfaction and self-efficacy:

- the 5 As (Ask, Advise, Assess, Assist, Arrange)

- the FRAMES protocol (Feedback, Responsibility, Advice, Menu, Empathy, and Self-efficacy)

- teachable moments (TM)

- solution-focused brief therapy (SFBT)

- cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT)

- narrative techniques (NT)

- motivational interviewing (MI).

But before we describe the practical application of these 7 techniques, we’ll begin by explaining a few underlying concepts for helping patients change their health-related behaviors.

Understanding what does—and doesn’t—help patients change

Research from the field of psychology and other social sciences has described several important concepts that affect how FPs can best help their patients change to healthier behaviors.2-9 First, several “common factors” have been found to reliably predict behavior change. The likelihood of change is strongly tied to the patient’s strengths, the environment, and the quality of the physician-patient relationship. The patient’s expectations and the techniques a physician uses also predict behavior change, but to a lesser extent.10

Second, patients seldom become motivated to change ingrained behaviors solely by being provided with information about the risks and benefits associated with those behaviors. People overcome ambivalence and develop motivation for change when they align their behaviors with their core values and goals. FPs can help patients link their motivation to change to specific plans and environments. This can then facilitate small changes that can yield large returns by increasing a patient’s self-efficacy and sense of control.2-9

Third, willpower is a finite but renewable resource that increases or decreases based on an individual’s internal and external environments. Reliance on willpower alone to make changes is unlikely to be successful without shaping the environment to support the new behavior.11

A patient’s readiness to change affects choice of technique

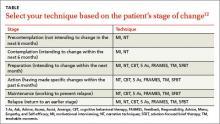

Knowing how ready a patient is to change is important for determining which approaches are likely to be effective at a given visit. Prochaska and DiClemente developed a model that defines 6 stages of change: Precontemplation (patient does not intend to change in the next 6 months), Contemplation (patient intends to change within the next 6 months), Preparation (patient intends to change within the next month), Action (patient has made specific changes within the past 6 months), Maintenance (patient works to prevent relapse), and Relapse (patient returns to an earlier stage) (TABLE).12

Patients who identify change as important and are ready to make changes benefit from collaborative work with an FP or other clinicians on the how, when, where, and who (eg, the patient, his or her significant other, family, and friends) of the new behaviors. These individuals are in the Preparation or Action stages of change, which comprise roughly 20% of patients.13 In these circumstances, techniques such as the 5 As, FRAMES, TM, SFBT, and CBT can be effective.

For the estimated 80% of patients who are in the Precontemplation or Contemplation stages and are unsure about the relative importance of changing behaviors and/or lack confidence to make changes, these directive techniques can cause defensiveness, which can make both the patient and the FP uncomfortable. For such patients, approaches that build on the patient’s own motivations and stories, such as MI and NT, may be preferred.

3 techniques that overlap

The FRAMES protocol and TM are based on behavior change theories, and each mixes directive techniques with relationship building to facilitate health behavior change. There is overlap in concepts across the 5 As, FRAMES, and TM, and some evidence suggests these approaches can be adapted for use in primary care settings.14-16

The 5 As is a brief intervention in which the FP sets an agenda and provides advice at the outset. This technique has been shown to improve smoking cessation rates in pregnant women compared with physician recommendations alone.17 It may also help with weight loss for patients who are ready to change and are given support for their

efforts.18

Putting the 5 As into action

CASE › An FP who wants to use the 5 As technique to assist Mr. G might proceed as follows: Ask: “How often do you exercise and follow a diet?” Advise: “I recommend that you start exercising 30 minutes each day and start following a healthier diet. It is one of the most important things you can do for your health.” Assess: “Are you willing to start exercising and trying a diet in the next month?” Assist: “Here is a list of local recreation centers and some information about a healthy diet.” Arrange: “I’d like to have one of the nurses call you in a week to see how things are going and have you return in a month for a follow-up appointment.”

The 6 components of the FRAMES protocol overlap with the 5 As.14 FRAMES utilizes relationship-building by explicitly reinforcing patient autonomy, offering a menu of choices, and acknowledging patient strengths.14

Putting the FRAMES protocol into action

CASE › Using the FRAMES protocol for Mr. G might consist of the following: Feedback: “Your eating habits and lack of exercise have contributed to your weight, high glucose and cholesterol levels, and shortness of breath.” Responsibility: “The decision to lose weight is a choice only you can make.” Advice: “I recommend that you start regularly exercising and eating healthily.” Menu: “Here are some options that many people find helpful when they try to lose weight.” Empathy: “It is challenging to change the way we eat and exercise.” Self-efficacy: “You have been able to overcome a lot of difficult things in your life already and it seems very important to you to make these changes.”

TM begins with the FP linking a patient concern, such as shortness of breath, to a physician concern, such as obesity.15 The FP then provides advice, assesses readiness, and responds based on the patient’s stage of change.16

Putting TM into action

CASE › Using the TM approach to help Mr. G might work as follows: Link a patient concern with specific behavioral change: “I think that your shortness of breath is caused by your weight.” Recommend change, offer support, and ask for commitment: “I recommend that you lose 15 pounds. I’m confident that you can do this, and am here to help you. Are you ready to talk about some specific ways you can do this?” Respond based on the patient’s readiness to change: “All right, let’s talk about healthy food choices and exercise.” (This statement would be appropriate if Mr. G was in the Preparation or Action stage of change.)

Solution-focused brief therapy

SFBT highlights a patient’s previous successes and strengths, as opposed to exploring problems and past failures.19,20 The FP fosters behavior change by using strategic questions to develop an intervention with the patient.21 SFBT involves encouraging patients to find exceptions to current problems and increasing the occurrence of current beneficial behaviors.19 This approach begins with the patient identifying a problem for which he or she would like help. The FP helps the patient explore solutions and/or exceptions to this problem that have worked for the patient previously (or solutions/exceptions that the patient can imagine). The FP does not offer suggestions to solve the patient’s problem. Instead, the patient and FP collaboratively identify and support the patient’s strengths, and they develop a behavioral task to try based on these patient-derived solutions.22

Putting SFBT into action

CASE › A physician who wants to use SFBT to help Mr. G might start by asking an “exception” question (“When have you been able to eat in a more healthy way?”) and following up with a “difference” question (“What was different about those times?”). Perhaps Mr. G remembers that previously he had improved his diet by buying and keeping a bag of apples in the car to snack on. He additionally recalls that he ate less at night if he brushed his teeth right after dinner.

Mr. G decides to revisit the apple and brushing strategies. Mr. G’s physician commends him for wanting to be there for his kids and identifying the apple and brushing strategies. She helps him design a small “experiment” in which he would use these strategies and observe the outcomes. They arrange to speak in one month to discuss how things are going.

Cognitive behavioral therapy

CBT is a practical, goal-directed, action-oriented treatment that focuses on helping patients make changes in their thinking and behavior.23-28 A basic premise of CBT is that emotions are difficult to change directly, so CBT targets distressing emotions by focusing on changing thoughts and/or behaviors that contribute to those emotions. CBT can be useful when the patient and FP can find a link between the patient’s thoughts and a troubling behavior. After thoroughly assessing situations that bother the patient, the FP provides the patient with an empathic summary that captures the essence of the problem. CBT practitioners typically conceptualize problems and plan treatment by working with the patient to gather information on the patient’s thoughts, feelings, and behaviors.

By exploring patterns of thinking that lead to self-destructive behaviors, an FP can help the patient understand and challenge strongly held but often limited patterns of thinking. For example, a patient with depression-related overeating might think, “I am worthless. Nothing ever goes right for me.” A patient with anxiety-related smoking may believe, “I am in danger.” Through a collaborative, respectful relationship, patients learn to test their “hypotheses,” challenge their thoughts, and experiment with alternate ways of thinking and behaving. Patients are given homework assignments, such as tracking their thoughts and behaviors, practicing relaxation techniques, and challenging automatic ways of viewing themselves and the world around them.

Putting CBT into action

CASE › An FP who wants to implement CBT to help Mr. G would begin by trying to understand his patient’s view: “Tell me how your weight is a part of your life.” Next, he would offer Mr. G an empathic summary: “You’re worried that your weight could cause some of the same health problems your dad has and that will prevent you from being the kind of active father you want to be. You sometimes eat when you are feeling stressed and tired, but then you feel worse afterwards.” He would assign Mr. G homework: “Notice and write down your thoughts when you are eating due to stress rather than hunger. Bring this in and we can look at it together.” The FP might also teach Mr. G relaxation breathing, and encourage him to try doing 5 relaxation breaths when he feels stressed and wants to eat.

Narrative techniques

NT can be effective for patients who are in the Precontemplation or Contemplation stages of change.29-33 NT focuses on the patient’s story, context, and language. FPs explore connections, discuss hypotheses, strategize, share power with the patient, and offer reflections in order to understand the patient’s illness experience. This approach fits well with the complex way that many behaviors are woven into the concerns that patients bring to their FPs. As a patient’s story unfolds, the diagnosis and treatment can occur simultaneously. The FP involves the patient in choices about how to proceed and what to focus on together.

NT avoids unsolicited advice and interpretations and rarely imposes the FP’s agenda on the patient. This approach invites the FP and patient to co-create an understanding and narrative of what the symptoms mean, why they are there, and what can be done about them. Ultimately, this approach can result in a new narrative that puts the patient on the path to healing.29-33

Putting NT into action

CASE › A physician might implement an NT approach with Mr. G to co-create a narrative about health and life goals by asking him: “Tell me about how losing weight fits into your goals for being there for your children. Tell me about how you see yourself avoiding some of the health problems your dad has faced.”

Motivational interviewing

For patients who are in the Precontemplation or Contemplation stages of change, MI might be a helpful approach. MI is a person-centered counseling style that addresses ambivalence about change while strengthening internal motivation for, and commitment to, change. It originally was used in addiction treatment, but has since been studied for and applied to a wide variety of medical and psychological conditions.34

MI has an underlying perspective (often called the “spirit” of MI) that includes partnership, acceptance, compassion, and evocation.34 Partnership implies a respectful collaboration between equals—while the FP may be an expert on a particular diagnosis, the patient is the expert on herself. Acceptance is unconditional positive regard and involves a nonjudgmental and person-centered recognition of an individual’s absolute worth and potential that supports autonomy and affirms strengths. Compassion is the sense of actively promoting a patient’s well being and prioritizing his or her needs over your own. Evocation refers to calling forth the patient’s own wisdom based on a realization that the patient has motivation and resources that can be elicited.

In contrast to a deficit model (“You are lacking something; I have it, and I will install it in you”), MI focuses on strengths (“You have what you need, and together we will find it”).

The skills of MI are practiced in a series of 4 sequential and overlapping processes known as Engaging, Focusing, Evoking, and Planning.34 Engaging is establishing a helpful connection and working relationship with a patient. Focusing is developing and maintaining a specific direction toward a goal (or goals). Evoking is eliciting the patient’s own motivations for change. Planning is developing commitment to change and formulating a specific action plan. Five core communication skills are used flexibly and strategically during these 4 processes: asking open questions, affirming, reflective listening, summarizing, and informing and advising with permission.34

Putting MI into action

CASE › An FP who wants to use MI with Mr. G would begin the Engaging and Focusing processes by asking permission: “May I ask you a question about weight loss?” If Mr. G says Yes, the FP would start the process of Evoking using scaling questions, such as: “On a scale of one to 10, where one means it’s not at all important, and 10 means that it’s very important, how important to you is losing weight?" (Mr. G: “I’d say 9, it is very important to me.”) “On a scale of one to 10, where one means that you are not at all confident, and 10 means that you are extremely confident, how confident are you that you can lose weight?” (Mr. G: “I’m a 6.”)

“Why are you at 6 rather than 1?” (Mr. G: “I have lost a few pounds in the past, so I know a little bit about losing weight.”) “What would have to happen for you to get to 7, that is, for you to become just a little bit more confident?” (Mr. G: “I would need to get my family’s support.”)

The FP would implement the Planning process by suggesting that Mr. G talk to his wife about taking a walk with him after dinner and buying skim milk instead of 2%.

CORRESPONDENCE

Michael Raddock, MD, Department of Family Medicine, MetroHealth Medical Center; 2500 MetroHealth Drive, Cleveland, Ohio 44109; mraddock@metrohealth.org

1. Mokdad AH, Marks JS, Stroup DF, et al. Actual causes of death in the United States, 2000. JAMA. 2004;291:1238-1245.

2. Heath C, Heath D. Switch: How to Change Things When Change is Hard. New York, NY: Crown Business; 2010.

3. Achor S. The Happiness Advantage: The Seven Principles of Positive Psychology That Fuel Success and Performance at Work. New York, NY: Crown Business; 2010.

4. Dweck CS. Mindset: The New Psychology of Success. New York, NY: Ballantine Books; 2006.

5. Kotter JP, Cohen DS. The Heart of Change: Real-Life Stories of How People Change Their Organizations. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Publishing; 2002.

6. Wansink B. Mindless Eating: Why We Eat More Than We Think. New York, NY: Bantam; 2006.

7. Thaler RH, Sunstein CS. Nudge: Improving Decisions About Health, Wealth, and Happiness. New York, NY: Penguin Books; 2009.

8. Maurer R. One Small Step Can Change Your Life: The Kaizen Way. New York, NY: Workman Publishing Company; 2004.

9. Patterson K, Grenny J, Maxfield D, et al. Influencer: The New Science of Leading Change. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2007.

10. Hubble MA, Duncan BL, Miller SD, eds. The Heart and Soul of Change: What Works in Therapy. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 1999.

11. Baumeister RF, Tierney J. Willpower: Rediscovering the Greatest Human Strength. New York, NY: Penguin Books; 2011.

12. Prochaska JO, DiClemente CC. The Transtheoretical Approach: Crossing Traditional Boundaries of Therapy. Homewood, IL: Dow Jones/Irwin; 1984.

13. Prochaska JO, Norcross JC. Stages of change. Psychother: Theory, Res, Pract, Training. 2001;38:443-448.

14. Searight HR. Realistic approaches to counseling in the office setting. Am Fam Physician. 2009;79:277-284.

15. Cohen DJ, Clark EC, Lawson PJ, et al. Identifying teachable moments for health behavior counseling in primary care. Patient Educ Couns. 2011;85:e8-e15.

16. Flocke SA, Antognoli E, Step MM, et al. A teachable moment communication process for smoking cessation talk: description of a group randomized clinician-focused intervention. BMC Health Serv Res. 2012;12:109.

17. Fiore MC, Bailey WC, Cohen SJ, et al. Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence. Clinical Practice Guideline. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2000.

18. Alexander SC, Cox ME, Boling Turer CL, et al. Do the Five A’s work when physicians counsel about weight loss? Fam Med. 2011;43:179-184.

19. Trepper TS, McCollum E, De Jong P, et al. Solution focused therapy treatment manual for working with individuals. Solution Focused Brief Therapy Association Web site. Available at: http://www.sfbta.org/research.pdf. Accessed December 23, 2014.

20. Molnar A, de Shazer S. Solution-focused therapy: Towards the identification of therapeutic tasks. J Marital Fam Ther. 1987;13:349-358.

21. Greenberg G, Ganshorn K, Danilkewich A. Solution-focused therapy. Counseling model for busy family physicians. Can Fam Physician. 2001;47:2289-2295.

22. Giorlando ME, Schilling RJ. On becoming a solution-focused physician: The MED-STAT acronym. Families Syst Health. 1997;15:361-373.

23. Beck AT. Thinking and depression. I. Idiosyncratic content and cognitive distortions. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1963;9:324-333.

24. Beck AT. Thinking and depression. II. Theory and therapy. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1964;10:561-571.

25. Beck AT. The current state of cognitive therapy: a 40-year retrospective. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:953-959.

26. Wright JH, Beck AT, Thase ME. Cognitive therapy. In: Hales RE, Yudofsky SC, Talbott JA, eds. Textbook of Clinical Psychiatry. 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2003:1245-1284.

27. Clark DA, Beck AT, Alford BA. Scientific Foundations of Cognitive Theory and Therapy of Depression. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons; 1999.

28. Wright JH, Basco MR, Thase ME. Learning Cognitive-Behavior Therapy: An Illustrated Guide. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2006.

29. Launer J. Narrative-based Primary Care: A Practical Guide. Abingdon, United Kingdom: Radcliffe Medical Press; 2002.

30. Engel JD, Zarconi J, Pethtel L, et al. Narrative in Health Care: Healing Patients, Practitioners, Profession, and Community. Abingdon, United Kingdom: Radcliffe Publishing; 2008.

31. Charon R. Narrative Medicine: Honoring the Stories of Illness. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2006.

32. Kleinman A. The Illness Narratives: Suffering, Healing & the Human Condition. New York, NY: Basic Books; 1988.

33. Kleinman A, Eisenberg L, Good B. Culture, illness, and care: clinical lessons from anthropologic and cross-cultural research. Ann Intern Med. 1978;88:251-258.

34. Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational Interviewing: Helping People Change. 3rd ed. New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 2013.

› Determine the patient’s stage of change (Precontemplation, Contemplation, Preparation, Action, Maintenance, or Relapse) before selecting an intervention to help him or her change health-related behaviors. B

› Consider using motivational interviewing or narrative techniques to help patients who aren’t yet ready to change their health-related behaviors or who plan to do so within 6 months. C

› Be aware that patients seldom become motivated to change behaviors by being given information about health risks and benefits; to overcome ambivalence, they need to focus on their core values and goals. C

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

CASE › Your patient, Bob G, age 47, has a body mass index of 33, hypertension (blood pressure 150/85 mm Hg), and elevated cholesterol (low-density lipoprotein level, 187 mg/dL) and glucose levels (fasting glucose 122 mg/dL, with an HbA1c of 6.1%). He gets out of breath when he plays with his 2 children. His father has diabetes and had a myocardial infarction (MI) at age 55; Mr. G tells you he is concerned he will develop similar health problems. Mr. G frequents fast food restaurants and eats high-calorie snacks after work, especially when he feels stressed. During a recent office visit, he expresses his desire to “be there” for his children and says he is motivated to lose weight to prevent diabetes and/or an MI.

How would you proceed?

Most health conditions in the United States are directly or indirectly the result of patients’ health-related behaviors.1 Fortunately, family physicians (FPs) and primary care teams are in an excellent position to help their patients make healthy behavior changes by using brief, evidence-based interventions that can be implemented during the typical office visit.

Specifically, the use of the following 7 techniques can build on patients’ own motivations, successes, and life circumstances to improve their satisfaction and self-efficacy:

- the 5 As (Ask, Advise, Assess, Assist, Arrange)

- the FRAMES protocol (Feedback, Responsibility, Advice, Menu, Empathy, and Self-efficacy)

- teachable moments (TM)

- solution-focused brief therapy (SFBT)

- cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT)

- narrative techniques (NT)

- motivational interviewing (MI).

But before we describe the practical application of these 7 techniques, we’ll begin by explaining a few underlying concepts for helping patients change their health-related behaviors.

Understanding what does—and doesn’t—help patients change

Research from the field of psychology and other social sciences has described several important concepts that affect how FPs can best help their patients change to healthier behaviors.2-9 First, several “common factors” have been found to reliably predict behavior change. The likelihood of change is strongly tied to the patient’s strengths, the environment, and the quality of the physician-patient relationship. The patient’s expectations and the techniques a physician uses also predict behavior change, but to a lesser extent.10

Second, patients seldom become motivated to change ingrained behaviors solely by being provided with information about the risks and benefits associated with those behaviors. People overcome ambivalence and develop motivation for change when they align their behaviors with their core values and goals. FPs can help patients link their motivation to change to specific plans and environments. This can then facilitate small changes that can yield large returns by increasing a patient’s self-efficacy and sense of control.2-9

Third, willpower is a finite but renewable resource that increases or decreases based on an individual’s internal and external environments. Reliance on willpower alone to make changes is unlikely to be successful without shaping the environment to support the new behavior.11

A patient’s readiness to change affects choice of technique

Knowing how ready a patient is to change is important for determining which approaches are likely to be effective at a given visit. Prochaska and DiClemente developed a model that defines 6 stages of change: Precontemplation (patient does not intend to change in the next 6 months), Contemplation (patient intends to change within the next 6 months), Preparation (patient intends to change within the next month), Action (patient has made specific changes within the past 6 months), Maintenance (patient works to prevent relapse), and Relapse (patient returns to an earlier stage) (TABLE).12

Patients who identify change as important and are ready to make changes benefit from collaborative work with an FP or other clinicians on the how, when, where, and who (eg, the patient, his or her significant other, family, and friends) of the new behaviors. These individuals are in the Preparation or Action stages of change, which comprise roughly 20% of patients.13 In these circumstances, techniques such as the 5 As, FRAMES, TM, SFBT, and CBT can be effective.

For the estimated 80% of patients who are in the Precontemplation or Contemplation stages and are unsure about the relative importance of changing behaviors and/or lack confidence to make changes, these directive techniques can cause defensiveness, which can make both the patient and the FP uncomfortable. For such patients, approaches that build on the patient’s own motivations and stories, such as MI and NT, may be preferred.

3 techniques that overlap

The FRAMES protocol and TM are based on behavior change theories, and each mixes directive techniques with relationship building to facilitate health behavior change. There is overlap in concepts across the 5 As, FRAMES, and TM, and some evidence suggests these approaches can be adapted for use in primary care settings.14-16

The 5 As is a brief intervention in which the FP sets an agenda and provides advice at the outset. This technique has been shown to improve smoking cessation rates in pregnant women compared with physician recommendations alone.17 It may also help with weight loss for patients who are ready to change and are given support for their

efforts.18

Putting the 5 As into action

CASE › An FP who wants to use the 5 As technique to assist Mr. G might proceed as follows: Ask: “How often do you exercise and follow a diet?” Advise: “I recommend that you start exercising 30 minutes each day and start following a healthier diet. It is one of the most important things you can do for your health.” Assess: “Are you willing to start exercising and trying a diet in the next month?” Assist: “Here is a list of local recreation centers and some information about a healthy diet.” Arrange: “I’d like to have one of the nurses call you in a week to see how things are going and have you return in a month for a follow-up appointment.”

The 6 components of the FRAMES protocol overlap with the 5 As.14 FRAMES utilizes relationship-building by explicitly reinforcing patient autonomy, offering a menu of choices, and acknowledging patient strengths.14

Putting the FRAMES protocol into action

CASE › Using the FRAMES protocol for Mr. G might consist of the following: Feedback: “Your eating habits and lack of exercise have contributed to your weight, high glucose and cholesterol levels, and shortness of breath.” Responsibility: “The decision to lose weight is a choice only you can make.” Advice: “I recommend that you start regularly exercising and eating healthily.” Menu: “Here are some options that many people find helpful when they try to lose weight.” Empathy: “It is challenging to change the way we eat and exercise.” Self-efficacy: “You have been able to overcome a lot of difficult things in your life already and it seems very important to you to make these changes.”

TM begins with the FP linking a patient concern, such as shortness of breath, to a physician concern, such as obesity.15 The FP then provides advice, assesses readiness, and responds based on the patient’s stage of change.16

Putting TM into action

CASE › Using the TM approach to help Mr. G might work as follows: Link a patient concern with specific behavioral change: “I think that your shortness of breath is caused by your weight.” Recommend change, offer support, and ask for commitment: “I recommend that you lose 15 pounds. I’m confident that you can do this, and am here to help you. Are you ready to talk about some specific ways you can do this?” Respond based on the patient’s readiness to change: “All right, let’s talk about healthy food choices and exercise.” (This statement would be appropriate if Mr. G was in the Preparation or Action stage of change.)

Solution-focused brief therapy

SFBT highlights a patient’s previous successes and strengths, as opposed to exploring problems and past failures.19,20 The FP fosters behavior change by using strategic questions to develop an intervention with the patient.21 SFBT involves encouraging patients to find exceptions to current problems and increasing the occurrence of current beneficial behaviors.19 This approach begins with the patient identifying a problem for which he or she would like help. The FP helps the patient explore solutions and/or exceptions to this problem that have worked for the patient previously (or solutions/exceptions that the patient can imagine). The FP does not offer suggestions to solve the patient’s problem. Instead, the patient and FP collaboratively identify and support the patient’s strengths, and they develop a behavioral task to try based on these patient-derived solutions.22

Putting SFBT into action

CASE › A physician who wants to use SFBT to help Mr. G might start by asking an “exception” question (“When have you been able to eat in a more healthy way?”) and following up with a “difference” question (“What was different about those times?”). Perhaps Mr. G remembers that previously he had improved his diet by buying and keeping a bag of apples in the car to snack on. He additionally recalls that he ate less at night if he brushed his teeth right after dinner.

Mr. G decides to revisit the apple and brushing strategies. Mr. G’s physician commends him for wanting to be there for his kids and identifying the apple and brushing strategies. She helps him design a small “experiment” in which he would use these strategies and observe the outcomes. They arrange to speak in one month to discuss how things are going.

Cognitive behavioral therapy

CBT is a practical, goal-directed, action-oriented treatment that focuses on helping patients make changes in their thinking and behavior.23-28 A basic premise of CBT is that emotions are difficult to change directly, so CBT targets distressing emotions by focusing on changing thoughts and/or behaviors that contribute to those emotions. CBT can be useful when the patient and FP can find a link between the patient’s thoughts and a troubling behavior. After thoroughly assessing situations that bother the patient, the FP provides the patient with an empathic summary that captures the essence of the problem. CBT practitioners typically conceptualize problems and plan treatment by working with the patient to gather information on the patient’s thoughts, feelings, and behaviors.

By exploring patterns of thinking that lead to self-destructive behaviors, an FP can help the patient understand and challenge strongly held but often limited patterns of thinking. For example, a patient with depression-related overeating might think, “I am worthless. Nothing ever goes right for me.” A patient with anxiety-related smoking may believe, “I am in danger.” Through a collaborative, respectful relationship, patients learn to test their “hypotheses,” challenge their thoughts, and experiment with alternate ways of thinking and behaving. Patients are given homework assignments, such as tracking their thoughts and behaviors, practicing relaxation techniques, and challenging automatic ways of viewing themselves and the world around them.

Putting CBT into action

CASE › An FP who wants to implement CBT to help Mr. G would begin by trying to understand his patient’s view: “Tell me how your weight is a part of your life.” Next, he would offer Mr. G an empathic summary: “You’re worried that your weight could cause some of the same health problems your dad has and that will prevent you from being the kind of active father you want to be. You sometimes eat when you are feeling stressed and tired, but then you feel worse afterwards.” He would assign Mr. G homework: “Notice and write down your thoughts when you are eating due to stress rather than hunger. Bring this in and we can look at it together.” The FP might also teach Mr. G relaxation breathing, and encourage him to try doing 5 relaxation breaths when he feels stressed and wants to eat.

Narrative techniques

NT can be effective for patients who are in the Precontemplation or Contemplation stages of change.29-33 NT focuses on the patient’s story, context, and language. FPs explore connections, discuss hypotheses, strategize, share power with the patient, and offer reflections in order to understand the patient’s illness experience. This approach fits well with the complex way that many behaviors are woven into the concerns that patients bring to their FPs. As a patient’s story unfolds, the diagnosis and treatment can occur simultaneously. The FP involves the patient in choices about how to proceed and what to focus on together.

NT avoids unsolicited advice and interpretations and rarely imposes the FP’s agenda on the patient. This approach invites the FP and patient to co-create an understanding and narrative of what the symptoms mean, why they are there, and what can be done about them. Ultimately, this approach can result in a new narrative that puts the patient on the path to healing.29-33

Putting NT into action

CASE › A physician might implement an NT approach with Mr. G to co-create a narrative about health and life goals by asking him: “Tell me about how losing weight fits into your goals for being there for your children. Tell me about how you see yourself avoiding some of the health problems your dad has faced.”

Motivational interviewing

For patients who are in the Precontemplation or Contemplation stages of change, MI might be a helpful approach. MI is a person-centered counseling style that addresses ambivalence about change while strengthening internal motivation for, and commitment to, change. It originally was used in addiction treatment, but has since been studied for and applied to a wide variety of medical and psychological conditions.34

MI has an underlying perspective (often called the “spirit” of MI) that includes partnership, acceptance, compassion, and evocation.34 Partnership implies a respectful collaboration between equals—while the FP may be an expert on a particular diagnosis, the patient is the expert on herself. Acceptance is unconditional positive regard and involves a nonjudgmental and person-centered recognition of an individual’s absolute worth and potential that supports autonomy and affirms strengths. Compassion is the sense of actively promoting a patient’s well being and prioritizing his or her needs over your own. Evocation refers to calling forth the patient’s own wisdom based on a realization that the patient has motivation and resources that can be elicited.

In contrast to a deficit model (“You are lacking something; I have it, and I will install it in you”), MI focuses on strengths (“You have what you need, and together we will find it”).

The skills of MI are practiced in a series of 4 sequential and overlapping processes known as Engaging, Focusing, Evoking, and Planning.34 Engaging is establishing a helpful connection and working relationship with a patient. Focusing is developing and maintaining a specific direction toward a goal (or goals). Evoking is eliciting the patient’s own motivations for change. Planning is developing commitment to change and formulating a specific action plan. Five core communication skills are used flexibly and strategically during these 4 processes: asking open questions, affirming, reflective listening, summarizing, and informing and advising with permission.34

Putting MI into action

CASE › An FP who wants to use MI with Mr. G would begin the Engaging and Focusing processes by asking permission: “May I ask you a question about weight loss?” If Mr. G says Yes, the FP would start the process of Evoking using scaling questions, such as: “On a scale of one to 10, where one means it’s not at all important, and 10 means that it’s very important, how important to you is losing weight?" (Mr. G: “I’d say 9, it is very important to me.”) “On a scale of one to 10, where one means that you are not at all confident, and 10 means that you are extremely confident, how confident are you that you can lose weight?” (Mr. G: “I’m a 6.”)

“Why are you at 6 rather than 1?” (Mr. G: “I have lost a few pounds in the past, so I know a little bit about losing weight.”) “What would have to happen for you to get to 7, that is, for you to become just a little bit more confident?” (Mr. G: “I would need to get my family’s support.”)

The FP would implement the Planning process by suggesting that Mr. G talk to his wife about taking a walk with him after dinner and buying skim milk instead of 2%.

CORRESPONDENCE

Michael Raddock, MD, Department of Family Medicine, MetroHealth Medical Center; 2500 MetroHealth Drive, Cleveland, Ohio 44109; mraddock@metrohealth.org

› Determine the patient’s stage of change (Precontemplation, Contemplation, Preparation, Action, Maintenance, or Relapse) before selecting an intervention to help him or her change health-related behaviors. B

› Consider using motivational interviewing or narrative techniques to help patients who aren’t yet ready to change their health-related behaviors or who plan to do so within 6 months. C

› Be aware that patients seldom become motivated to change behaviors by being given information about health risks and benefits; to overcome ambivalence, they need to focus on their core values and goals. C

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

CASE › Your patient, Bob G, age 47, has a body mass index of 33, hypertension (blood pressure 150/85 mm Hg), and elevated cholesterol (low-density lipoprotein level, 187 mg/dL) and glucose levels (fasting glucose 122 mg/dL, with an HbA1c of 6.1%). He gets out of breath when he plays with his 2 children. His father has diabetes and had a myocardial infarction (MI) at age 55; Mr. G tells you he is concerned he will develop similar health problems. Mr. G frequents fast food restaurants and eats high-calorie snacks after work, especially when he feels stressed. During a recent office visit, he expresses his desire to “be there” for his children and says he is motivated to lose weight to prevent diabetes and/or an MI.

How would you proceed?

Most health conditions in the United States are directly or indirectly the result of patients’ health-related behaviors.1 Fortunately, family physicians (FPs) and primary care teams are in an excellent position to help their patients make healthy behavior changes by using brief, evidence-based interventions that can be implemented during the typical office visit.

Specifically, the use of the following 7 techniques can build on patients’ own motivations, successes, and life circumstances to improve their satisfaction and self-efficacy:

- the 5 As (Ask, Advise, Assess, Assist, Arrange)

- the FRAMES protocol (Feedback, Responsibility, Advice, Menu, Empathy, and Self-efficacy)

- teachable moments (TM)

- solution-focused brief therapy (SFBT)

- cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT)

- narrative techniques (NT)

- motivational interviewing (MI).

But before we describe the practical application of these 7 techniques, we’ll begin by explaining a few underlying concepts for helping patients change their health-related behaviors.

Understanding what does—and doesn’t—help patients change

Research from the field of psychology and other social sciences has described several important concepts that affect how FPs can best help their patients change to healthier behaviors.2-9 First, several “common factors” have been found to reliably predict behavior change. The likelihood of change is strongly tied to the patient’s strengths, the environment, and the quality of the physician-patient relationship. The patient’s expectations and the techniques a physician uses also predict behavior change, but to a lesser extent.10

Second, patients seldom become motivated to change ingrained behaviors solely by being provided with information about the risks and benefits associated with those behaviors. People overcome ambivalence and develop motivation for change when they align their behaviors with their core values and goals. FPs can help patients link their motivation to change to specific plans and environments. This can then facilitate small changes that can yield large returns by increasing a patient’s self-efficacy and sense of control.2-9

Third, willpower is a finite but renewable resource that increases or decreases based on an individual’s internal and external environments. Reliance on willpower alone to make changes is unlikely to be successful without shaping the environment to support the new behavior.11

A patient’s readiness to change affects choice of technique

Knowing how ready a patient is to change is important for determining which approaches are likely to be effective at a given visit. Prochaska and DiClemente developed a model that defines 6 stages of change: Precontemplation (patient does not intend to change in the next 6 months), Contemplation (patient intends to change within the next 6 months), Preparation (patient intends to change within the next month), Action (patient has made specific changes within the past 6 months), Maintenance (patient works to prevent relapse), and Relapse (patient returns to an earlier stage) (TABLE).12

Patients who identify change as important and are ready to make changes benefit from collaborative work with an FP or other clinicians on the how, when, where, and who (eg, the patient, his or her significant other, family, and friends) of the new behaviors. These individuals are in the Preparation or Action stages of change, which comprise roughly 20% of patients.13 In these circumstances, techniques such as the 5 As, FRAMES, TM, SFBT, and CBT can be effective.

For the estimated 80% of patients who are in the Precontemplation or Contemplation stages and are unsure about the relative importance of changing behaviors and/or lack confidence to make changes, these directive techniques can cause defensiveness, which can make both the patient and the FP uncomfortable. For such patients, approaches that build on the patient’s own motivations and stories, such as MI and NT, may be preferred.

3 techniques that overlap

The FRAMES protocol and TM are based on behavior change theories, and each mixes directive techniques with relationship building to facilitate health behavior change. There is overlap in concepts across the 5 As, FRAMES, and TM, and some evidence suggests these approaches can be adapted for use in primary care settings.14-16

The 5 As is a brief intervention in which the FP sets an agenda and provides advice at the outset. This technique has been shown to improve smoking cessation rates in pregnant women compared with physician recommendations alone.17 It may also help with weight loss for patients who are ready to change and are given support for their

efforts.18

Putting the 5 As into action

CASE › An FP who wants to use the 5 As technique to assist Mr. G might proceed as follows: Ask: “How often do you exercise and follow a diet?” Advise: “I recommend that you start exercising 30 minutes each day and start following a healthier diet. It is one of the most important things you can do for your health.” Assess: “Are you willing to start exercising and trying a diet in the next month?” Assist: “Here is a list of local recreation centers and some information about a healthy diet.” Arrange: “I’d like to have one of the nurses call you in a week to see how things are going and have you return in a month for a follow-up appointment.”

The 6 components of the FRAMES protocol overlap with the 5 As.14 FRAMES utilizes relationship-building by explicitly reinforcing patient autonomy, offering a menu of choices, and acknowledging patient strengths.14

Putting the FRAMES protocol into action

CASE › Using the FRAMES protocol for Mr. G might consist of the following: Feedback: “Your eating habits and lack of exercise have contributed to your weight, high glucose and cholesterol levels, and shortness of breath.” Responsibility: “The decision to lose weight is a choice only you can make.” Advice: “I recommend that you start regularly exercising and eating healthily.” Menu: “Here are some options that many people find helpful when they try to lose weight.” Empathy: “It is challenging to change the way we eat and exercise.” Self-efficacy: “You have been able to overcome a lot of difficult things in your life already and it seems very important to you to make these changes.”

TM begins with the FP linking a patient concern, such as shortness of breath, to a physician concern, such as obesity.15 The FP then provides advice, assesses readiness, and responds based on the patient’s stage of change.16

Putting TM into action

CASE › Using the TM approach to help Mr. G might work as follows: Link a patient concern with specific behavioral change: “I think that your shortness of breath is caused by your weight.” Recommend change, offer support, and ask for commitment: “I recommend that you lose 15 pounds. I’m confident that you can do this, and am here to help you. Are you ready to talk about some specific ways you can do this?” Respond based on the patient’s readiness to change: “All right, let’s talk about healthy food choices and exercise.” (This statement would be appropriate if Mr. G was in the Preparation or Action stage of change.)

Solution-focused brief therapy

SFBT highlights a patient’s previous successes and strengths, as opposed to exploring problems and past failures.19,20 The FP fosters behavior change by using strategic questions to develop an intervention with the patient.21 SFBT involves encouraging patients to find exceptions to current problems and increasing the occurrence of current beneficial behaviors.19 This approach begins with the patient identifying a problem for which he or she would like help. The FP helps the patient explore solutions and/or exceptions to this problem that have worked for the patient previously (or solutions/exceptions that the patient can imagine). The FP does not offer suggestions to solve the patient’s problem. Instead, the patient and FP collaboratively identify and support the patient’s strengths, and they develop a behavioral task to try based on these patient-derived solutions.22

Putting SFBT into action

CASE › A physician who wants to use SFBT to help Mr. G might start by asking an “exception” question (“When have you been able to eat in a more healthy way?”) and following up with a “difference” question (“What was different about those times?”). Perhaps Mr. G remembers that previously he had improved his diet by buying and keeping a bag of apples in the car to snack on. He additionally recalls that he ate less at night if he brushed his teeth right after dinner.

Mr. G decides to revisit the apple and brushing strategies. Mr. G’s physician commends him for wanting to be there for his kids and identifying the apple and brushing strategies. She helps him design a small “experiment” in which he would use these strategies and observe the outcomes. They arrange to speak in one month to discuss how things are going.

Cognitive behavioral therapy

CBT is a practical, goal-directed, action-oriented treatment that focuses on helping patients make changes in their thinking and behavior.23-28 A basic premise of CBT is that emotions are difficult to change directly, so CBT targets distressing emotions by focusing on changing thoughts and/or behaviors that contribute to those emotions. CBT can be useful when the patient and FP can find a link between the patient’s thoughts and a troubling behavior. After thoroughly assessing situations that bother the patient, the FP provides the patient with an empathic summary that captures the essence of the problem. CBT practitioners typically conceptualize problems and plan treatment by working with the patient to gather information on the patient’s thoughts, feelings, and behaviors.

By exploring patterns of thinking that lead to self-destructive behaviors, an FP can help the patient understand and challenge strongly held but often limited patterns of thinking. For example, a patient with depression-related overeating might think, “I am worthless. Nothing ever goes right for me.” A patient with anxiety-related smoking may believe, “I am in danger.” Through a collaborative, respectful relationship, patients learn to test their “hypotheses,” challenge their thoughts, and experiment with alternate ways of thinking and behaving. Patients are given homework assignments, such as tracking their thoughts and behaviors, practicing relaxation techniques, and challenging automatic ways of viewing themselves and the world around them.

Putting CBT into action

CASE › An FP who wants to implement CBT to help Mr. G would begin by trying to understand his patient’s view: “Tell me how your weight is a part of your life.” Next, he would offer Mr. G an empathic summary: “You’re worried that your weight could cause some of the same health problems your dad has and that will prevent you from being the kind of active father you want to be. You sometimes eat when you are feeling stressed and tired, but then you feel worse afterwards.” He would assign Mr. G homework: “Notice and write down your thoughts when you are eating due to stress rather than hunger. Bring this in and we can look at it together.” The FP might also teach Mr. G relaxation breathing, and encourage him to try doing 5 relaxation breaths when he feels stressed and wants to eat.

Narrative techniques

NT can be effective for patients who are in the Precontemplation or Contemplation stages of change.29-33 NT focuses on the patient’s story, context, and language. FPs explore connections, discuss hypotheses, strategize, share power with the patient, and offer reflections in order to understand the patient’s illness experience. This approach fits well with the complex way that many behaviors are woven into the concerns that patients bring to their FPs. As a patient’s story unfolds, the diagnosis and treatment can occur simultaneously. The FP involves the patient in choices about how to proceed and what to focus on together.

NT avoids unsolicited advice and interpretations and rarely imposes the FP’s agenda on the patient. This approach invites the FP and patient to co-create an understanding and narrative of what the symptoms mean, why they are there, and what can be done about them. Ultimately, this approach can result in a new narrative that puts the patient on the path to healing.29-33

Putting NT into action

CASE › A physician might implement an NT approach with Mr. G to co-create a narrative about health and life goals by asking him: “Tell me about how losing weight fits into your goals for being there for your children. Tell me about how you see yourself avoiding some of the health problems your dad has faced.”

Motivational interviewing

For patients who are in the Precontemplation or Contemplation stages of change, MI might be a helpful approach. MI is a person-centered counseling style that addresses ambivalence about change while strengthening internal motivation for, and commitment to, change. It originally was used in addiction treatment, but has since been studied for and applied to a wide variety of medical and psychological conditions.34

MI has an underlying perspective (often called the “spirit” of MI) that includes partnership, acceptance, compassion, and evocation.34 Partnership implies a respectful collaboration between equals—while the FP may be an expert on a particular diagnosis, the patient is the expert on herself. Acceptance is unconditional positive regard and involves a nonjudgmental and person-centered recognition of an individual’s absolute worth and potential that supports autonomy and affirms strengths. Compassion is the sense of actively promoting a patient’s well being and prioritizing his or her needs over your own. Evocation refers to calling forth the patient’s own wisdom based on a realization that the patient has motivation and resources that can be elicited.

In contrast to a deficit model (“You are lacking something; I have it, and I will install it in you”), MI focuses on strengths (“You have what you need, and together we will find it”).

The skills of MI are practiced in a series of 4 sequential and overlapping processes known as Engaging, Focusing, Evoking, and Planning.34 Engaging is establishing a helpful connection and working relationship with a patient. Focusing is developing and maintaining a specific direction toward a goal (or goals). Evoking is eliciting the patient’s own motivations for change. Planning is developing commitment to change and formulating a specific action plan. Five core communication skills are used flexibly and strategically during these 4 processes: asking open questions, affirming, reflective listening, summarizing, and informing and advising with permission.34

Putting MI into action

CASE › An FP who wants to use MI with Mr. G would begin the Engaging and Focusing processes by asking permission: “May I ask you a question about weight loss?” If Mr. G says Yes, the FP would start the process of Evoking using scaling questions, such as: “On a scale of one to 10, where one means it’s not at all important, and 10 means that it’s very important, how important to you is losing weight?" (Mr. G: “I’d say 9, it is very important to me.”) “On a scale of one to 10, where one means that you are not at all confident, and 10 means that you are extremely confident, how confident are you that you can lose weight?” (Mr. G: “I’m a 6.”)

“Why are you at 6 rather than 1?” (Mr. G: “I have lost a few pounds in the past, so I know a little bit about losing weight.”) “What would have to happen for you to get to 7, that is, for you to become just a little bit more confident?” (Mr. G: “I would need to get my family’s support.”)

The FP would implement the Planning process by suggesting that Mr. G talk to his wife about taking a walk with him after dinner and buying skim milk instead of 2%.

CORRESPONDENCE

Michael Raddock, MD, Department of Family Medicine, MetroHealth Medical Center; 2500 MetroHealth Drive, Cleveland, Ohio 44109; mraddock@metrohealth.org

1. Mokdad AH, Marks JS, Stroup DF, et al. Actual causes of death in the United States, 2000. JAMA. 2004;291:1238-1245.

2. Heath C, Heath D. Switch: How to Change Things When Change is Hard. New York, NY: Crown Business; 2010.

3. Achor S. The Happiness Advantage: The Seven Principles of Positive Psychology That Fuel Success and Performance at Work. New York, NY: Crown Business; 2010.

4. Dweck CS. Mindset: The New Psychology of Success. New York, NY: Ballantine Books; 2006.

5. Kotter JP, Cohen DS. The Heart of Change: Real-Life Stories of How People Change Their Organizations. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Publishing; 2002.

6. Wansink B. Mindless Eating: Why We Eat More Than We Think. New York, NY: Bantam; 2006.

7. Thaler RH, Sunstein CS. Nudge: Improving Decisions About Health, Wealth, and Happiness. New York, NY: Penguin Books; 2009.

8. Maurer R. One Small Step Can Change Your Life: The Kaizen Way. New York, NY: Workman Publishing Company; 2004.

9. Patterson K, Grenny J, Maxfield D, et al. Influencer: The New Science of Leading Change. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2007.

10. Hubble MA, Duncan BL, Miller SD, eds. The Heart and Soul of Change: What Works in Therapy. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 1999.

11. Baumeister RF, Tierney J. Willpower: Rediscovering the Greatest Human Strength. New York, NY: Penguin Books; 2011.

12. Prochaska JO, DiClemente CC. The Transtheoretical Approach: Crossing Traditional Boundaries of Therapy. Homewood, IL: Dow Jones/Irwin; 1984.

13. Prochaska JO, Norcross JC. Stages of change. Psychother: Theory, Res, Pract, Training. 2001;38:443-448.

14. Searight HR. Realistic approaches to counseling in the office setting. Am Fam Physician. 2009;79:277-284.

15. Cohen DJ, Clark EC, Lawson PJ, et al. Identifying teachable moments for health behavior counseling in primary care. Patient Educ Couns. 2011;85:e8-e15.

16. Flocke SA, Antognoli E, Step MM, et al. A teachable moment communication process for smoking cessation talk: description of a group randomized clinician-focused intervention. BMC Health Serv Res. 2012;12:109.

17. Fiore MC, Bailey WC, Cohen SJ, et al. Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence. Clinical Practice Guideline. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2000.

18. Alexander SC, Cox ME, Boling Turer CL, et al. Do the Five A’s work when physicians counsel about weight loss? Fam Med. 2011;43:179-184.

19. Trepper TS, McCollum E, De Jong P, et al. Solution focused therapy treatment manual for working with individuals. Solution Focused Brief Therapy Association Web site. Available at: http://www.sfbta.org/research.pdf. Accessed December 23, 2014.

20. Molnar A, de Shazer S. Solution-focused therapy: Towards the identification of therapeutic tasks. J Marital Fam Ther. 1987;13:349-358.

21. Greenberg G, Ganshorn K, Danilkewich A. Solution-focused therapy. Counseling model for busy family physicians. Can Fam Physician. 2001;47:2289-2295.

22. Giorlando ME, Schilling RJ. On becoming a solution-focused physician: The MED-STAT acronym. Families Syst Health. 1997;15:361-373.

23. Beck AT. Thinking and depression. I. Idiosyncratic content and cognitive distortions. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1963;9:324-333.

24. Beck AT. Thinking and depression. II. Theory and therapy. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1964;10:561-571.

25. Beck AT. The current state of cognitive therapy: a 40-year retrospective. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:953-959.

26. Wright JH, Beck AT, Thase ME. Cognitive therapy. In: Hales RE, Yudofsky SC, Talbott JA, eds. Textbook of Clinical Psychiatry. 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2003:1245-1284.

27. Clark DA, Beck AT, Alford BA. Scientific Foundations of Cognitive Theory and Therapy of Depression. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons; 1999.

28. Wright JH, Basco MR, Thase ME. Learning Cognitive-Behavior Therapy: An Illustrated Guide. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2006.

29. Launer J. Narrative-based Primary Care: A Practical Guide. Abingdon, United Kingdom: Radcliffe Medical Press; 2002.

30. Engel JD, Zarconi J, Pethtel L, et al. Narrative in Health Care: Healing Patients, Practitioners, Profession, and Community. Abingdon, United Kingdom: Radcliffe Publishing; 2008.

31. Charon R. Narrative Medicine: Honoring the Stories of Illness. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2006.

32. Kleinman A. The Illness Narratives: Suffering, Healing & the Human Condition. New York, NY: Basic Books; 1988.

33. Kleinman A, Eisenberg L, Good B. Culture, illness, and care: clinical lessons from anthropologic and cross-cultural research. Ann Intern Med. 1978;88:251-258.

34. Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational Interviewing: Helping People Change. 3rd ed. New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 2013.

1. Mokdad AH, Marks JS, Stroup DF, et al. Actual causes of death in the United States, 2000. JAMA. 2004;291:1238-1245.

2. Heath C, Heath D. Switch: How to Change Things When Change is Hard. New York, NY: Crown Business; 2010.

3. Achor S. The Happiness Advantage: The Seven Principles of Positive Psychology That Fuel Success and Performance at Work. New York, NY: Crown Business; 2010.

4. Dweck CS. Mindset: The New Psychology of Success. New York, NY: Ballantine Books; 2006.

5. Kotter JP, Cohen DS. The Heart of Change: Real-Life Stories of How People Change Their Organizations. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Publishing; 2002.

6. Wansink B. Mindless Eating: Why We Eat More Than We Think. New York, NY: Bantam; 2006.

7. Thaler RH, Sunstein CS. Nudge: Improving Decisions About Health, Wealth, and Happiness. New York, NY: Penguin Books; 2009.

8. Maurer R. One Small Step Can Change Your Life: The Kaizen Way. New York, NY: Workman Publishing Company; 2004.

9. Patterson K, Grenny J, Maxfield D, et al. Influencer: The New Science of Leading Change. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2007.

10. Hubble MA, Duncan BL, Miller SD, eds. The Heart and Soul of Change: What Works in Therapy. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 1999.

11. Baumeister RF, Tierney J. Willpower: Rediscovering the Greatest Human Strength. New York, NY: Penguin Books; 2011.

12. Prochaska JO, DiClemente CC. The Transtheoretical Approach: Crossing Traditional Boundaries of Therapy. Homewood, IL: Dow Jones/Irwin; 1984.

13. Prochaska JO, Norcross JC. Stages of change. Psychother: Theory, Res, Pract, Training. 2001;38:443-448.

14. Searight HR. Realistic approaches to counseling in the office setting. Am Fam Physician. 2009;79:277-284.

15. Cohen DJ, Clark EC, Lawson PJ, et al. Identifying teachable moments for health behavior counseling in primary care. Patient Educ Couns. 2011;85:e8-e15.

16. Flocke SA, Antognoli E, Step MM, et al. A teachable moment communication process for smoking cessation talk: description of a group randomized clinician-focused intervention. BMC Health Serv Res. 2012;12:109.

17. Fiore MC, Bailey WC, Cohen SJ, et al. Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence. Clinical Practice Guideline. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2000.

18. Alexander SC, Cox ME, Boling Turer CL, et al. Do the Five A’s work when physicians counsel about weight loss? Fam Med. 2011;43:179-184.

19. Trepper TS, McCollum E, De Jong P, et al. Solution focused therapy treatment manual for working with individuals. Solution Focused Brief Therapy Association Web site. Available at: http://www.sfbta.org/research.pdf. Accessed December 23, 2014.

20. Molnar A, de Shazer S. Solution-focused therapy: Towards the identification of therapeutic tasks. J Marital Fam Ther. 1987;13:349-358.

21. Greenberg G, Ganshorn K, Danilkewich A. Solution-focused therapy. Counseling model for busy family physicians. Can Fam Physician. 2001;47:2289-2295.

22. Giorlando ME, Schilling RJ. On becoming a solution-focused physician: The MED-STAT acronym. Families Syst Health. 1997;15:361-373.

23. Beck AT. Thinking and depression. I. Idiosyncratic content and cognitive distortions. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1963;9:324-333.

24. Beck AT. Thinking and depression. II. Theory and therapy. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1964;10:561-571.

25. Beck AT. The current state of cognitive therapy: a 40-year retrospective. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:953-959.

26. Wright JH, Beck AT, Thase ME. Cognitive therapy. In: Hales RE, Yudofsky SC, Talbott JA, eds. Textbook of Clinical Psychiatry. 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2003:1245-1284.

27. Clark DA, Beck AT, Alford BA. Scientific Foundations of Cognitive Theory and Therapy of Depression. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons; 1999.

28. Wright JH, Basco MR, Thase ME. Learning Cognitive-Behavior Therapy: An Illustrated Guide. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2006.

29. Launer J. Narrative-based Primary Care: A Practical Guide. Abingdon, United Kingdom: Radcliffe Medical Press; 2002.

30. Engel JD, Zarconi J, Pethtel L, et al. Narrative in Health Care: Healing Patients, Practitioners, Profession, and Community. Abingdon, United Kingdom: Radcliffe Publishing; 2008.

31. Charon R. Narrative Medicine: Honoring the Stories of Illness. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2006.

32. Kleinman A. The Illness Narratives: Suffering, Healing & the Human Condition. New York, NY: Basic Books; 1988.

33. Kleinman A, Eisenberg L, Good B. Culture, illness, and care: clinical lessons from anthropologic and cross-cultural research. Ann Intern Med. 1978;88:251-258.

34. Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational Interviewing: Helping People Change. 3rd ed. New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 2013.