User login

Patient Flow Composite Measurement

Patient flow refers to the management and movement of patients in a healthcare facility. Healthcare institutions utilize patient flow analyses to evaluate and improve aspects of the patient experience including safety, effectiveness, efficiency, timeliness, patient centeredness, and equity.[1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8] Hospitals can evaluate patient flow using specific metrics, such as time in emergency department (ED) or percent of discharges completed by a certain time of day. However, no single metric can represent the full spectrum of processes inherent to patient flow. For example, ED length of stay (LOS) is dependent on inpatient occupancy, which is dependent on discharge timeliness. Each of these activities depends on various smaller activities, such as cleaning rooms or identifying available beds.

Evaluating the quality that healthcare organizations deliver is growing in importance.[9] Composite scores are being used increasingly to assess clinical processes and outcomes for professionals and institutions.[10, 11] Where various aspects of performance coexist, composite measures can incorporate multiple metrics into a comprehensive summary.[12, 13, 14, 15, 16] They also allow organizations to track a range of metrics for more holistic, comprehensive evaluations.[9, 13]

This article describes a balanced scorecard with composite scoring used at a large urban children's hospital to evaluate patient flow and direct improvement resources where they are needed most.

METHODS

The Children's Hospital of Philadelphia identified patient flow improvement as an operating plan initiative. Previously, performance was measured with a series of independent measures including time from ED arrival to transfer to the inpatient floor, and time from discharge order to room vacancy. These metrics were dismissed as sole measures of flow because they did not reflect the complexity and interdependence of processes or improvement efforts. There were also concerns that efforts to improve a measure caused unintended consequences for others, which at best lead to little overall improvement, and at worst reduced performance elsewhere in the value chain. For example, to meet a goal time for entering discharge orders, physicians could enter orders earlier. But, if patients were not actually ready to leave, their beds were not made available any earlier. Similarly, bed management staff could rush to meet a goal for speed of unit assignment, but this could cause an increase in patients admitted to the wrong specialty floor.

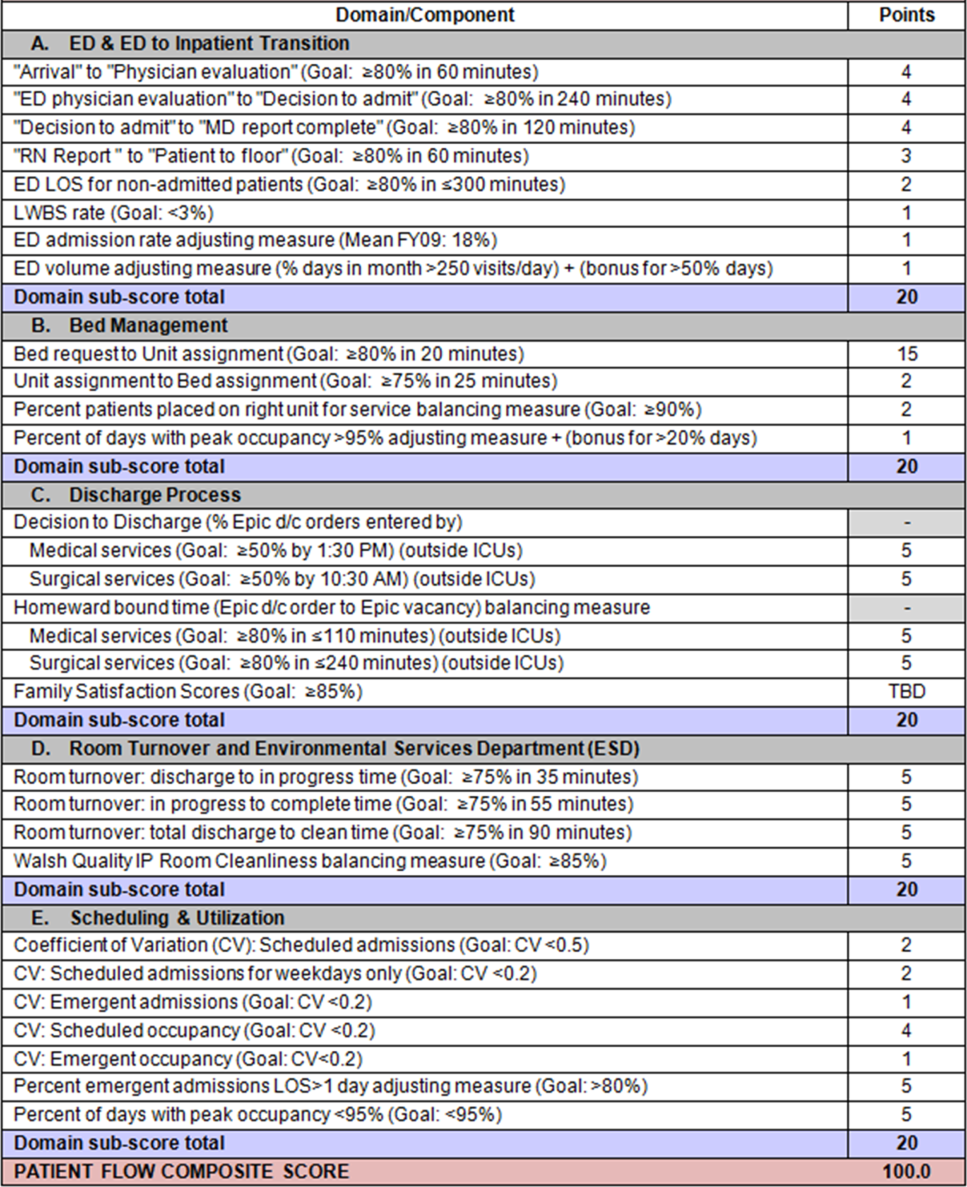

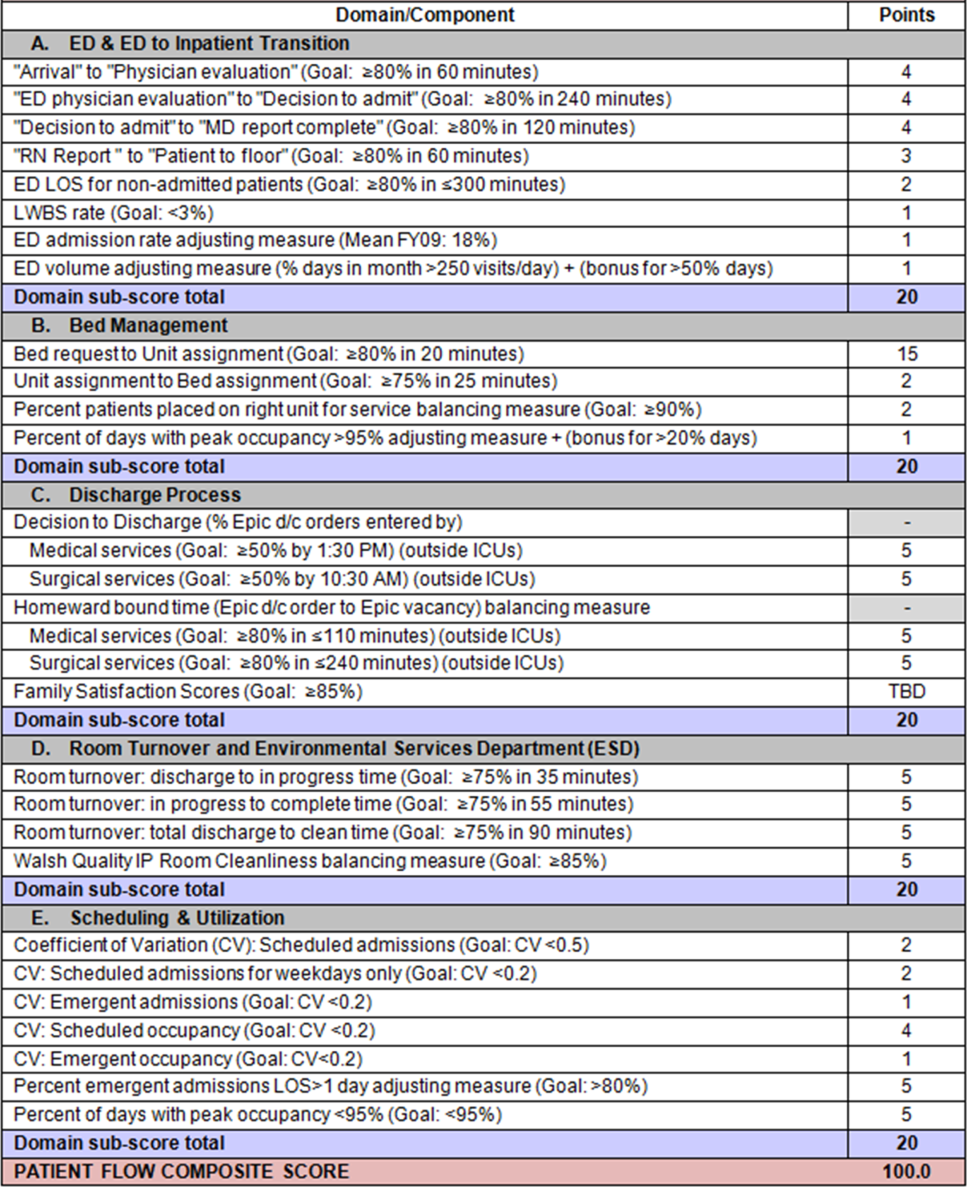

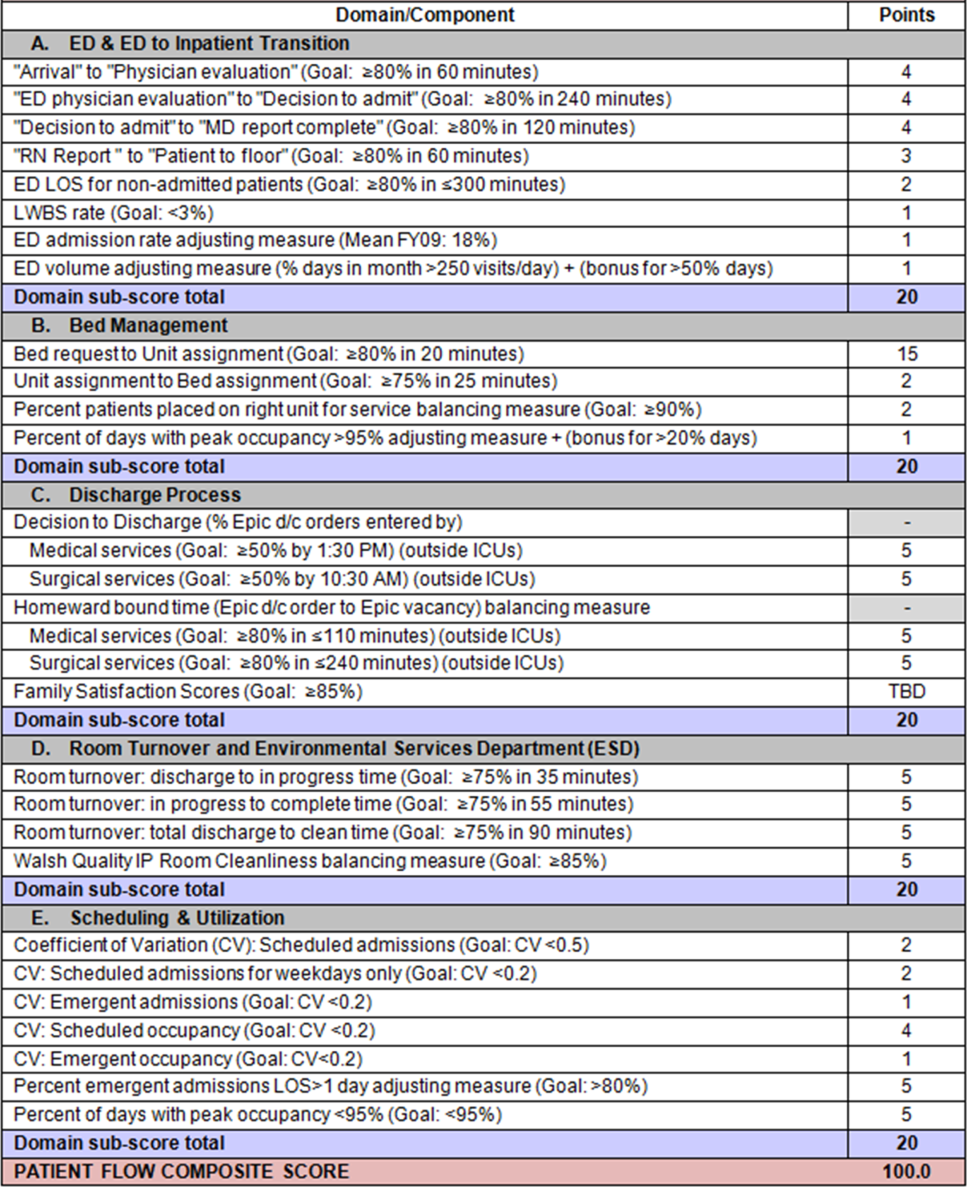

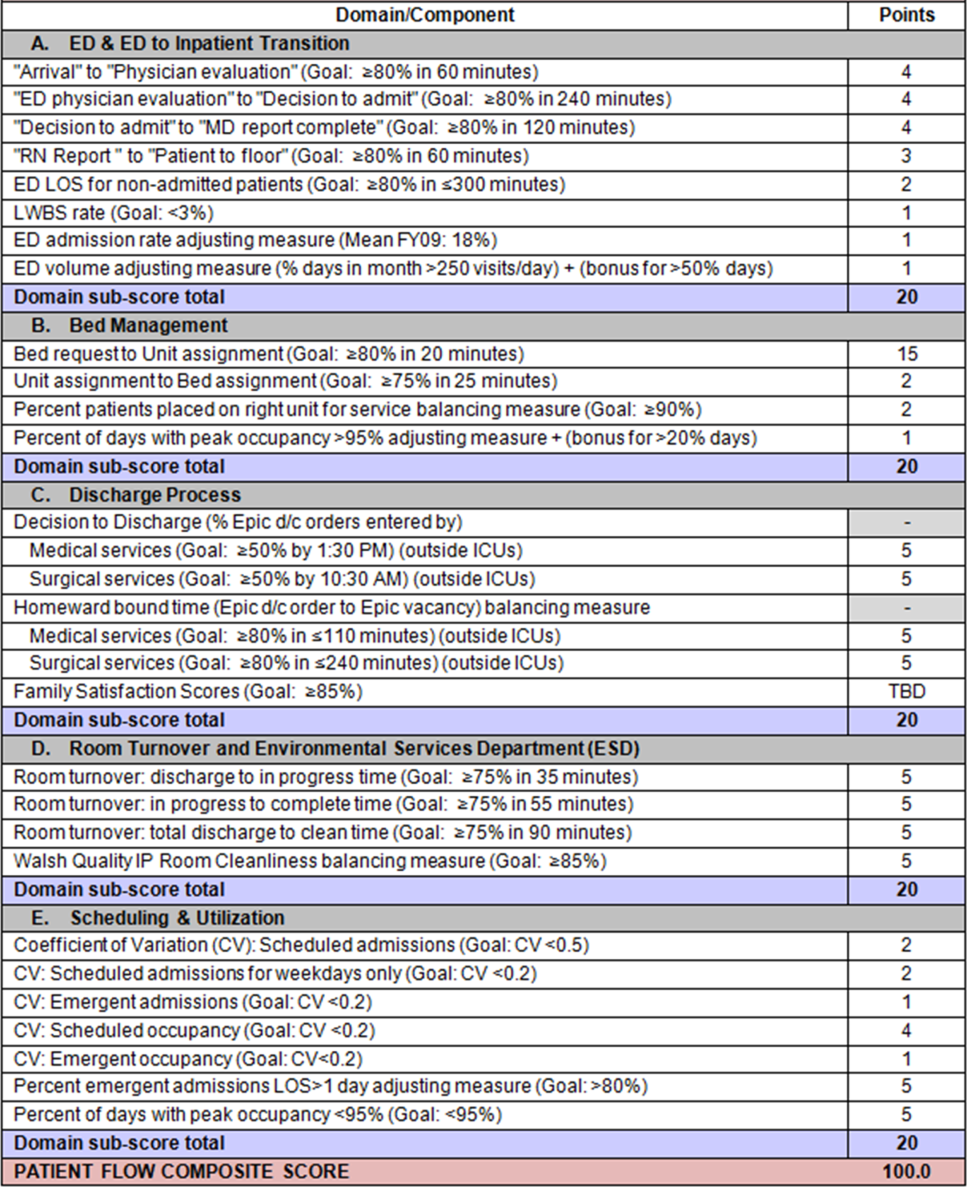

To address these concerns, a group of physicians, nurses, quality improvement specialists, and researchers designed a patient flow scorecard with composite measurement. Five domains of patient flow were identified: (1) ED and ED‐to‐inpatient transition, (2) bed management, (3) discharge process, (4) room turnover and environmental services department (ESD) activities, and (5) scheduling and utilization. Component measures for each domain were selected for 1 of 3 purposes: (1) to correspond to processes of importance to flow and improvement work, (2) to act as adjusters for factors that affect performance, or (3) to act as balancing measures so that progress in a measure would not result in the degradation of another. Each domain was assigned 20 points, which were distributed across the domain's components based on a consensus of the component's relative importance to overall domain performance (Figure 1). Data from the previous year were used as guidelines for setting performance percentile goals. For example, a goal of 80% in 60 minutes for arrival to physician evaluation meant that 80% of patients should see a physician within 1 hour of arriving at the ED.

Scores were also categorized to correspond to commonly used color descriptors.[17] For each component measure, performance meeting or exceeding the goal fell into the green category. Performances 10 percentage points below the goal fell into the yellow category, and performances below that level fell into the red category. Domain‐level scores and overall composite scores were also assigned colors. Performance at or above 80% (16 on the 20‐point domain scale, or 80 on the 100‐point overall scale) were designated green, scores between 70% and 79% were yellow, and scores below 70% were red.

DOMAINS OF THE PATIENT FLOW COMPOSITE SCORE

ED and ED‐to‐Inpatient Transition

Patient progression from the ED to an inpatient unit was separated into 4 steps (Figure 1A): (1) arrival to physician evaluation, (2) ED physician evaluation to decision to admit, (3) decision to admit to medical doctor (MD) report complete, and (4) registered nurse (RN) report to patient to floor. Four additional metrics included: (5) ED LOS for nonadmitted patients, (6) leaving without being seen (LWBS) rate, (7) ED admission rate, and (8) ED volume.

Arrival to physician evaluation measures time between patient arrival in the ED and self‐assignment by the first doctor or nurse practitioner in the electronic record, with a goal of 80% of patients seen within 60 minutes. The component score is calculated as percent of patients meeting this goal (ie, seen within 60 minutes) component weight. ED physician evaluation to decision to admit measures time from the start of the physician evaluation to the decision to admit, using bed request as a proxy; the goal was 80% within 4 hours. Decision to admit to MD report complete measures time from bed request to patient sign‐out to the inpatient floor, with a goal of 80% within 2 hours. RN report to patient to floor measures time from sign‐out to the patient leaving the ED, with a goal of 80% within 1 hour. ED LOS for nonadmitted patients measures time in the ED for patients who are not admitted, and the goal was 80% in 5 hours. The domain also tracks the LWBS rate, with a goal of keeping it below 3%. Its component score is calculated as percent patients seen component weight. ED admission rate is an adjusting factor for the severity of patients visiting the ED. Its component score is calculated as (percent of patients visiting the ED who are admitted to the hospital 5) component weight. Because the average admission rate is around 20%, the percent admitted is multiplied by 5 to more effectively adjust for high‐severity patients. ED volume is an adjusting factor that accounts for high volume. Its component score is calculated as percent of days in a month with more than 250 visits (a threshold chosen by the ED team) component weight. If these days exceed 50%, that percent would be added to the component score as an additional adjustment for excessive volume.

Bed Management

The bed management domain measures how efficiently and effectively patients are assigned to units and beds using 4 metrics (Figure 1B): (1) bed request to unit assignment, (2) unit assignment to bed assignment, (3) percentage of patients placed on right unit for service, and (4) percent of days with peak occupancy >95%.

Bed request to unit assignment measures time from the ED request for a bed in the electronic system to patient being assigned to a unit, with a goal of 80% of assignments made within 20 minutes. Unit assignment to bed assignment measures time from unit assignment to bed assignment, with a goal of 75% within 25 minutes. Because this goal was set to 75% rather than 80%, this component score was multiplied by 80/75 so that all component scores could be compared on the same scale. Percentage of patients placed on right unit for service is a balancing measure for speed of assignment. Because the goal was set to 90% rather than 80%, this component score was also multiplied by an adjusting factor (80/90) so that all components could be compared on the same scale. Percent of days with peak occupancy >95% is an adjusting measure that reflects that locating an appropriate bed takes longer when the hospital is approaching full occupancy. Its component score is calculated as (percent of days with peak occupancy >95% + 1) component weight. The was added to more effectively adjust for high occupancy. If more than 20% of days had peak occupancy greater than 95%, that percent would be added to the component score as an additional adjustment for excessive capacity.

Discharge Process

The discharge process domain measures the efficiency of patient discharge using 2 metrics (Figure 1C): (1) decision to discharge and (2) homeward bound time.

Decision to discharge tracks when clinicians enter electronic discharge orders. The goal was 50% by 1:30 pm for medical services and 10:30 am for surgical services. This encourages physicians to enter discharge orders early to enable downstream discharge work to begin. The component score is calculated as percent entered by goal time component weight (80/50) to adjust the 50% goal up to 80% so all component scores could be compared on the same scale. Homeward bound time measures the time between the discharge order and room vacancy as entered by the unit clerk, with a goal of 80% of patients leaving within 110 minutes for medical services and 240 minutes for surgical services. This balancing measure captures the fact that entering discharge orders early does not facilitate flow if the patients do not actually leave the hospital.

Room Turnover and Environmental Services Department

The room turnover and ESD domain measures the quality of the room turnover processes using 4 metrics (Figure 1D): (1) discharge to in progress time, (2) in progress to complete time, (3) total discharge to clean time, and (4) room cleanliness.

Discharge to in progress time measures time from patient vacancy until ESD staff enters the room, with a goal of 75% within 35 minutes. Because the goal was set to 75% rather than 80%, this component score was multiplied by 80/75 so all component scores could be compared on the same scale. In progress to complete time measures time as entered in the electronic health record from ESD staff entering the room to the room being clean, with a goal of 75% within 55 minutes. The component score is calculated identically to the previous metric. Total discharge to clean time measures the length of the total process, with a goal of 75% within 90 minutes. This component score was also multiplied by 80/75 so that all component scores could be compared on the same scale. Although this repeats the first 2 measures, given workflow and interface issues with our electronic health record (Epic, Epic Systems Corporation, Verona Wisconsin), it is necessary to include a total end‐to‐end measure in addition to the subparts. Patient and family ratings of room cleanliness serve as balancing measures, with the component score calculated as percent satisfaction component weight (80/85) to adjust the 85% satisfaction goal to 80% so all component scores could be compared on the same scale.

Scheduling and Utilization

The scheduling and utilization domain measures hospital operations and variations in bed utilization using 7 metrics including (Figure 1E): (1) coefficient of variation (CV): scheduled admissions, (2) CV: scheduled admissions for weekdays only, (3) CV: emergent admissions, (4) CV: scheduled occupancy, (5) CV: emergent occupancy, (6) percent emergent admissions with LOS >1 day, and (7) percent of days with peak occupancy 95%.

The CV, standard deviation divided by the mean of a distribution, is a measure of dispersion. Because it is a normalized value reported as a percentage, CV can be used to compare variability when sample sizes differ. CV: scheduled admissions captures the variability in admissions coded as an elective across all days in a month. The raw CV score is the standard deviation of the elective admissions for each day divided by the mean. The component score is (1 CV) component weight. A higher CV indicates greater variability, and yields a lower component score. CV on scheduled and emergent occupancy is derived from peak daily occupancy. Percent emergent admissions with LOS >1 day captures the efficiency of bed use, because high volumes of short‐stay patients increases turnover work. Its component score is calculated as the percent of emergent admissions in a month with LOS >1 day component weight. Percent of days with peak occupancy 95% incentivizes the hospital to avoid full occupancy, because effective flow requires that some beds remain open.[18, 19] Its component score is calculated as the percent of days in the month with peak occupancy 95% component weight. Although a similar measure, percent of days with peak occupancy >95%, was an adjusting factor in the bed management domain, it is included again here, because this factor has a unique effect on both domains.

RESULTS

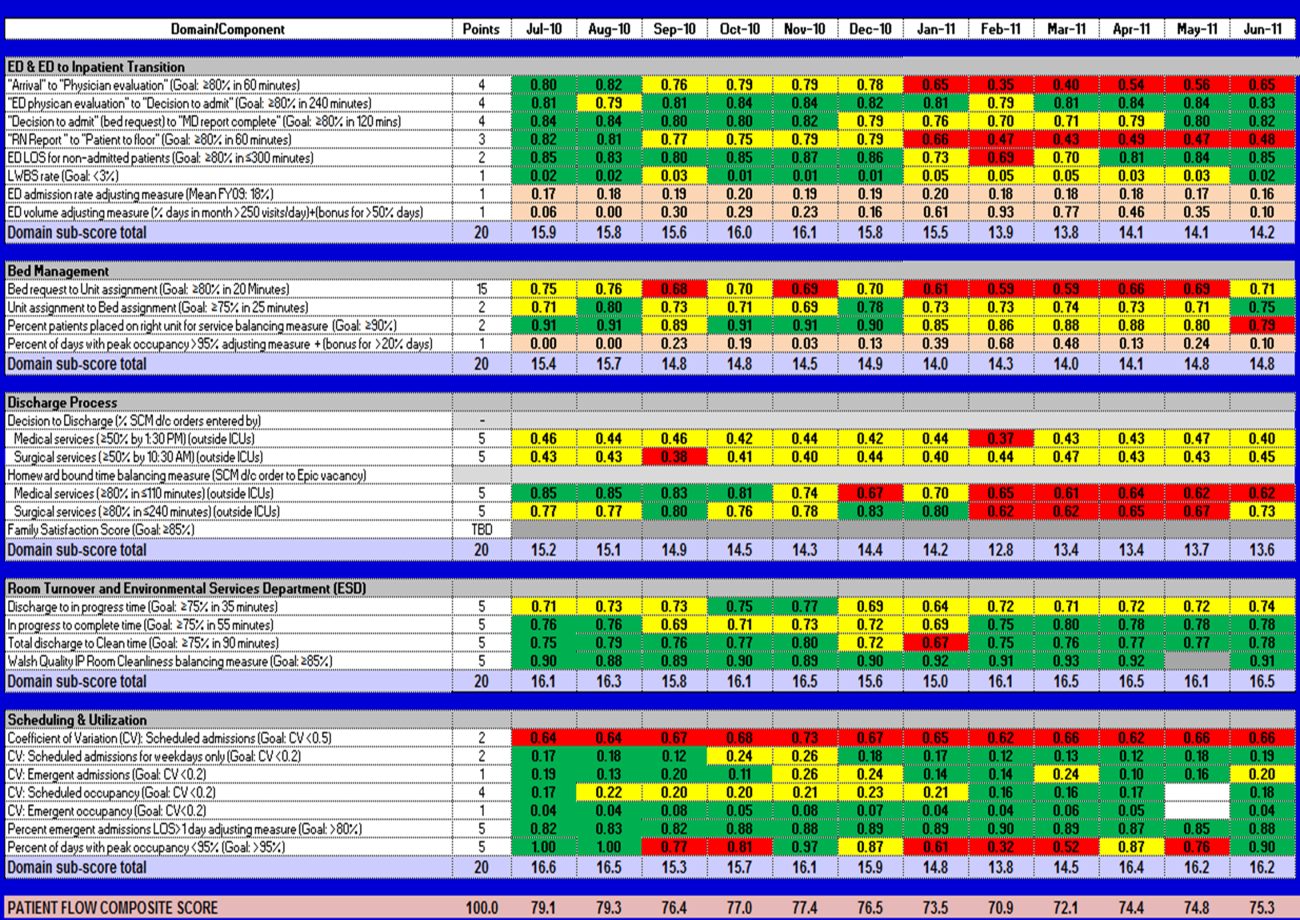

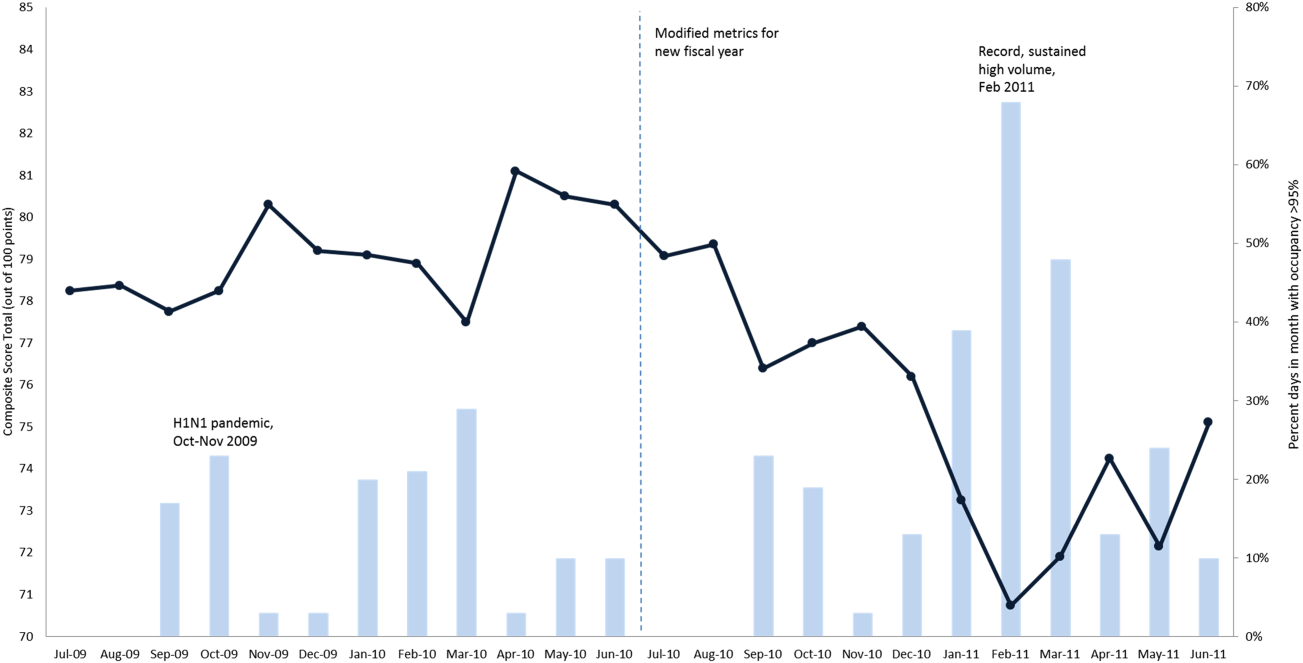

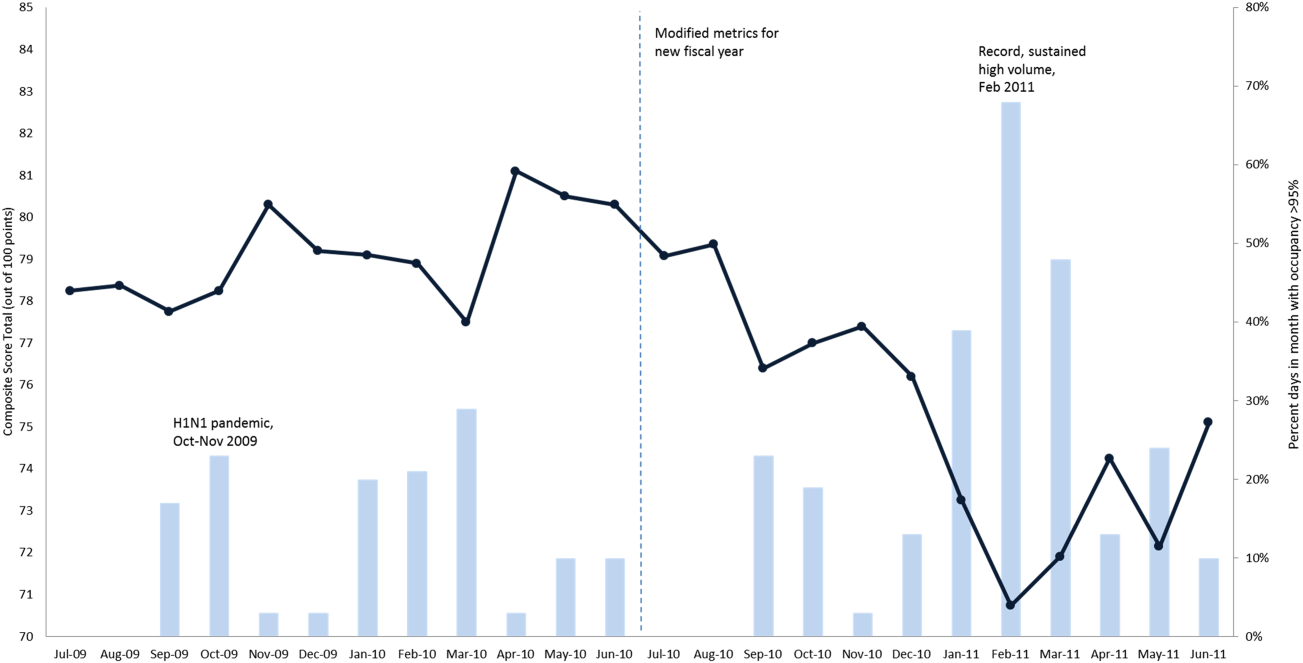

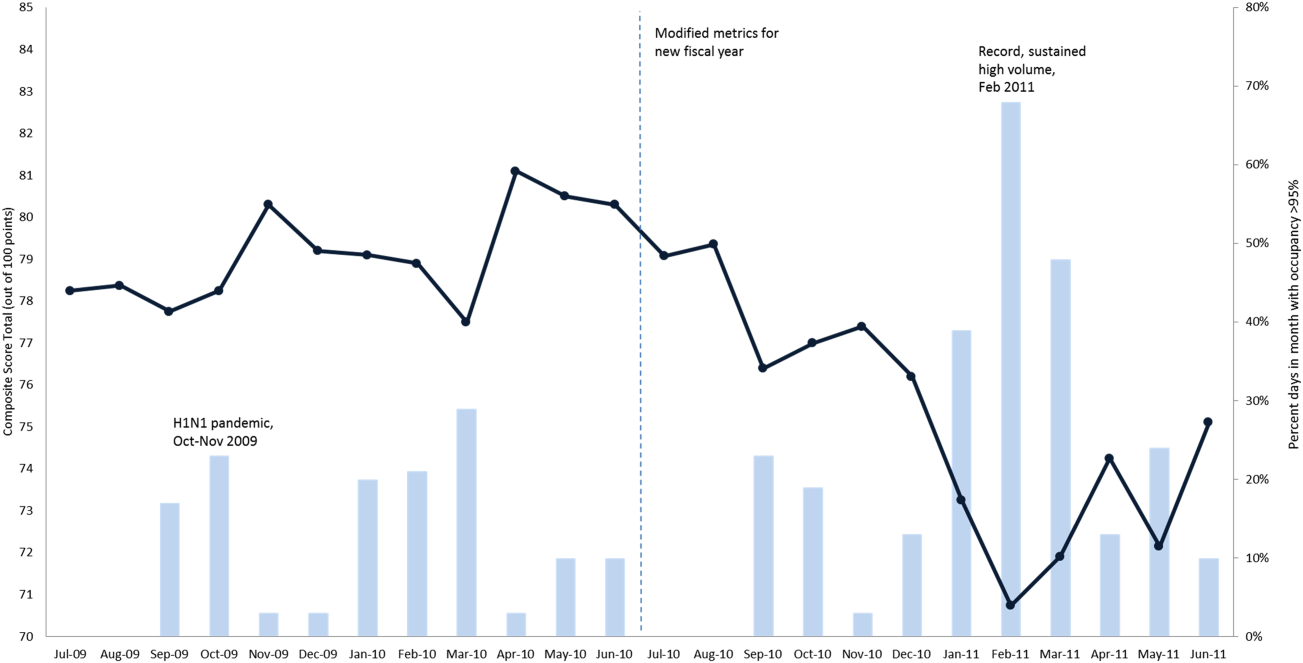

The balanced scorecard with composite measures provided improvement teams and administrators with a picture of patient flow (Figure 2). The overall score provided a global perspective on patient flow over time and captured trends in performance during various states of hospital occupancy. One trend that it captured was an association between high volume and poor composite scores (Figure 3). Notably, the H1N1 influenza pandemic in the fall of 2009 and the turnover of computer systems in January 2011 can be linked to dips in performance. The changes between fiscal years reflect a shift in baseline metrics.

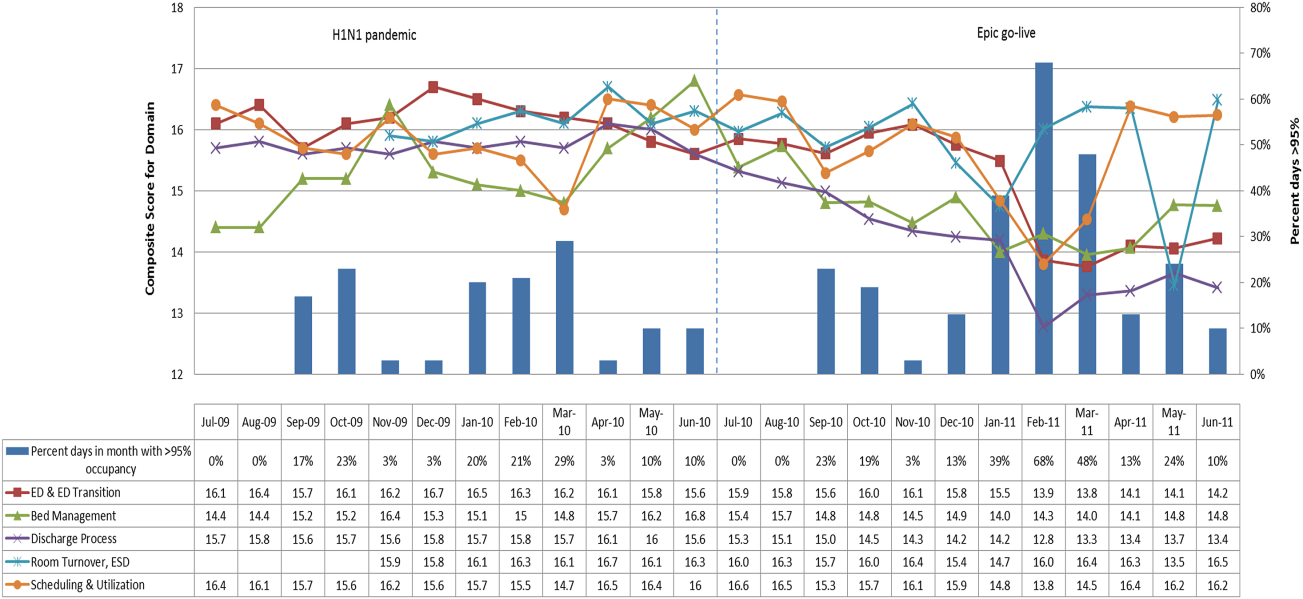

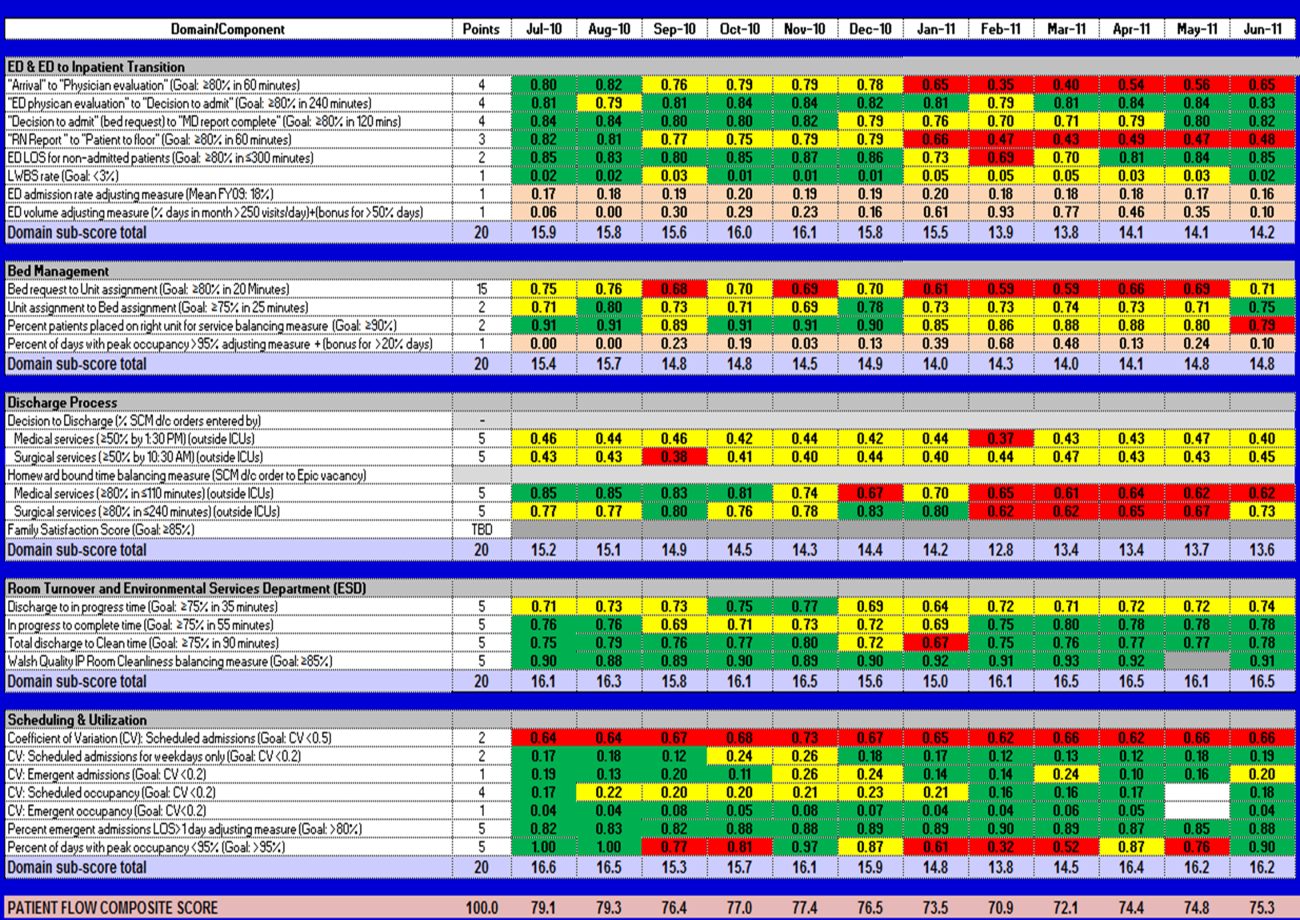

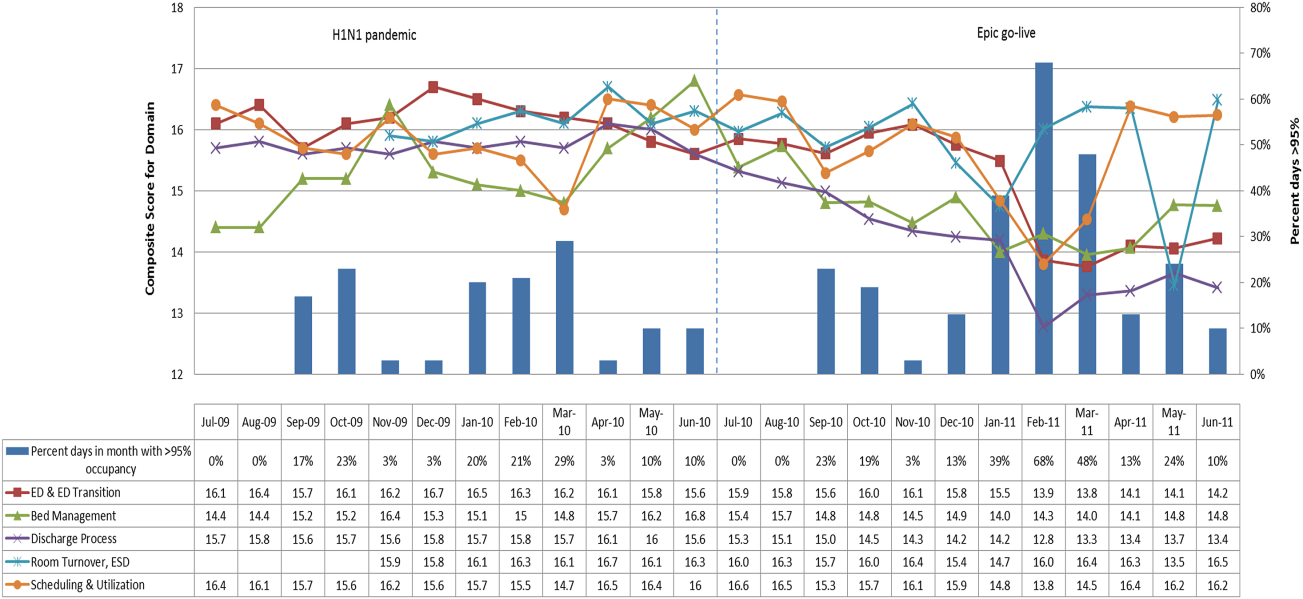

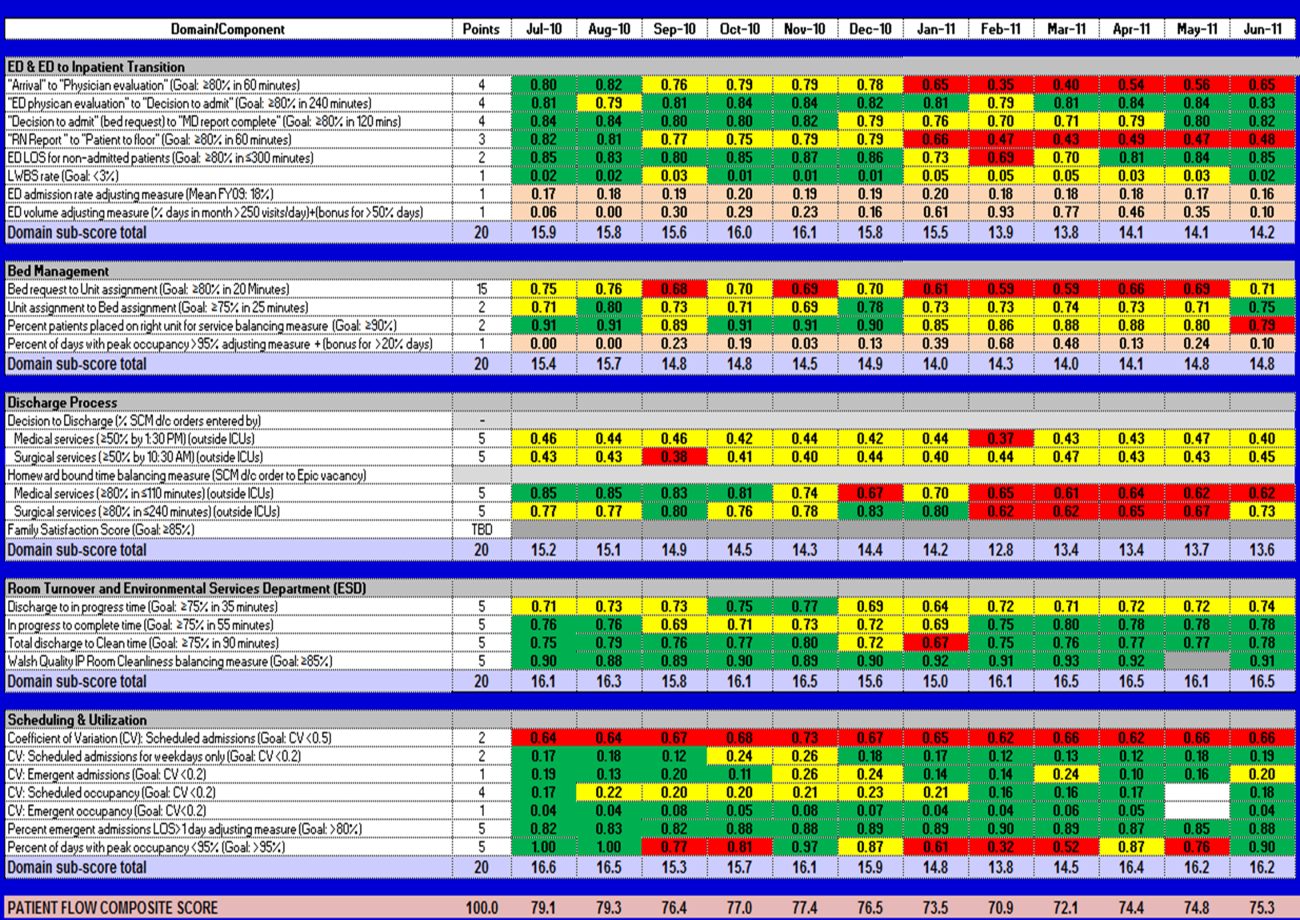

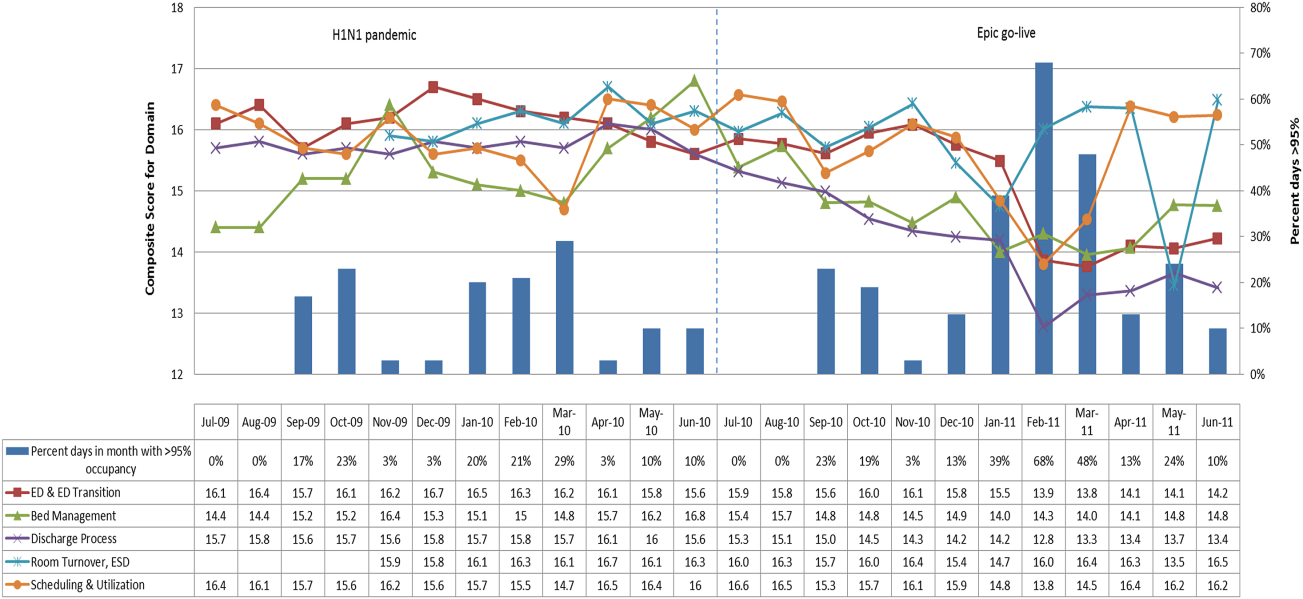

In addition to the overall composite score, the domain level and individual component scores allowed for more specific evaluation of variables affecting quality of care and enabled targeted improvement activities (Figure 4). For example, in December 2010 and January 2011, room turnover and ESD domain scores dropped, especially in the total discharge to clean time component. In response, the ESD made staffing adjustments, and starting in February 2011, component scores and the domain score improved. Feedback from the scheduling and utilization domain scores also initiated positive change. In August 2010, the CV: scheduled occupancy component score started to drop. In response, certain elective admissions were shifted to weekends to distribute hospital occupancy more evenly throughout the week. By February 2011, the component returned to its goal level. This continual evaluation of performance motivates continual improvement.

DISCUSSION

The use of a patient flow balanced scorecard with composite measurement overcomes pitfalls associated with a single or unaggregated measure. Aggregate scores alone mask important differences and relationships among components.[13] For example, 2 domains may be inversely related, or a provider with an overall average score might score above average in 1 domain but below in another. The composite scorecard, however, shows individual component and domain scores in addition to an aggregate score. The individual component and domain level scores highlight specific areas that need improvement and allow attention to be directed to those areas.

Additionally, a composite score is more likely to engage the range of staff involved in patient flow. Scaling out of 100 points and the red‐yellow‐green model are familiar for operations performance and can be easily understood.[17] Moreover, a composite score allows for dynamic performance goals while maintaining a stable measurement structure. For example, standardized LOS ratios, readmission rates, and denied hospital days can be added to the scorecard to provide more information and balancing measures.

Although balanced scorecards with composites can make holistic performance visible across multiple operational domains, they have some disadvantages. First, because there is a degree of complexity associated with a measure that incorporates multiple aspects of flow, certain elements, such as the relationship between a metric and its balancing measure, may not be readily apparent. Second, composite measures may not provide actionable information if the measure is not clearly related to a process that can be improved.[13, 14] Third, individual metrics may not be replicable between locations, so composites may need to be individualized to each setting.[10, 20]

Improving patient flow is a goal at many hospitals. Although measurement is crucial to identifying and mitigating variations, measuring the multidimensional aspects of flow and their impact on quality is difficult. Our scorecard, with composite measurement, addresses the need for an improved method to assess patient flow and improve quality by tracking care processes simultaneously.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Bhuvaneswari Jayaraman for her contributions to the original calculations for the first version of the composite score.

Disclosures: Internal funds from The Children's Hospital of Philadelphia supported the conduct of this work. The authors report no conflicts of interest.

- AHA Solutions. Patient Flow Challenges Assessment 2009. Chicago, IL: American Hospital Association; 2009.

- , , , et al. The impact of emergency department crowding measures on time to antibiotics for patients with community‐acquired pneumonia. Ann Emerg Med. 2007;50(5):510–516.

- . Practice variation: implications for our health care system. Manag Care. 2004;13(9 suppl):3–7.

- . Managing variability in patient flow is the key to improving access to care, nursing staffing, quality of care, and reducing its cost. Paper presented at: Institute of Medicine; June 24, 2004; Washington, DC.

- , , . Developing models for patient flow and daily surge capacity research. Acad Emerg Med. 2006;13(11):1109–1113.

- , , , , . Patient flow variability and unplanned readmissions to an intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2009;37(11):2882–2887.

- , , , , , . Scheduled admissions and high occupancy at a children's hospital. J Hosp Med. 2011;6(2):81–87.

- , , . Frequent overcrowding in US emergency departments. Acad Emerg Med. 2001;8(2):151–155.

- Institute of Medicine. Performance measurement: accelerating improvement. Available at: http://www.iom.edu/Reports/2005/Performance‐Measurement‐Accelerating‐Improvement.aspx. Published December 1, 2005. Accessed December 5, 2012.

- , , , . Emergency department performance measures and benchmarking summit. Acad Emerg Med. 2006;13(10):1074–1080.

- . The Surgical Infection Prevention and Surgical Care Improvement Projects: promises and pitfalls. Am Surg. 2006;72(11):1010–1016; discussion 1021–1030, 1133–1048.

- , , . Patient safety quality indicators. Composite measures workgroup. Final report. Rockville, MD; Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2008.

- , , , et al. ACCF/AHA 2010 position statement on composite measures for healthcare performance assessment: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on performance measures (Writing Committee to develop a position statement on composite measures). Circulation. 2010;121(15):1780–1791.

- , . A five‐point checklist to help performance reports incentivize improvement and effectively guide patients. Health Aff (Millwood). 2012;31(3):612–618.

- , , , , . Composite measures for profiling hospitals on surgical morbidity. Ann Surg. 2013;257(1):67–72.

- , . All‐or‐none measurement raises the bar on performance. JAMA. 2006;295(10):1168–1170.

- , , , et al. Quality improvement. Red light‐green light: from kids' game to discharge tool. Healthc Q. 2011;14:77–81.

- , , , . Myths of ideal hospital occupancy. Med J Aust. 2010;192(1):42–43.

- , . Emergency department overcrowding in the United States: an emerging threat to patient safety and public health. Emerg Med J. 2003;20(5):402–405.

- , , , . Emergency department crowding: consensus development of potential measures. Ann Emerg Med. 2003;42(6):824–834.

Patient flow refers to the management and movement of patients in a healthcare facility. Healthcare institutions utilize patient flow analyses to evaluate and improve aspects of the patient experience including safety, effectiveness, efficiency, timeliness, patient centeredness, and equity.[1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8] Hospitals can evaluate patient flow using specific metrics, such as time in emergency department (ED) or percent of discharges completed by a certain time of day. However, no single metric can represent the full spectrum of processes inherent to patient flow. For example, ED length of stay (LOS) is dependent on inpatient occupancy, which is dependent on discharge timeliness. Each of these activities depends on various smaller activities, such as cleaning rooms or identifying available beds.

Evaluating the quality that healthcare organizations deliver is growing in importance.[9] Composite scores are being used increasingly to assess clinical processes and outcomes for professionals and institutions.[10, 11] Where various aspects of performance coexist, composite measures can incorporate multiple metrics into a comprehensive summary.[12, 13, 14, 15, 16] They also allow organizations to track a range of metrics for more holistic, comprehensive evaluations.[9, 13]

This article describes a balanced scorecard with composite scoring used at a large urban children's hospital to evaluate patient flow and direct improvement resources where they are needed most.

METHODS

The Children's Hospital of Philadelphia identified patient flow improvement as an operating plan initiative. Previously, performance was measured with a series of independent measures including time from ED arrival to transfer to the inpatient floor, and time from discharge order to room vacancy. These metrics were dismissed as sole measures of flow because they did not reflect the complexity and interdependence of processes or improvement efforts. There were also concerns that efforts to improve a measure caused unintended consequences for others, which at best lead to little overall improvement, and at worst reduced performance elsewhere in the value chain. For example, to meet a goal time for entering discharge orders, physicians could enter orders earlier. But, if patients were not actually ready to leave, their beds were not made available any earlier. Similarly, bed management staff could rush to meet a goal for speed of unit assignment, but this could cause an increase in patients admitted to the wrong specialty floor.

To address these concerns, a group of physicians, nurses, quality improvement specialists, and researchers designed a patient flow scorecard with composite measurement. Five domains of patient flow were identified: (1) ED and ED‐to‐inpatient transition, (2) bed management, (3) discharge process, (4) room turnover and environmental services department (ESD) activities, and (5) scheduling and utilization. Component measures for each domain were selected for 1 of 3 purposes: (1) to correspond to processes of importance to flow and improvement work, (2) to act as adjusters for factors that affect performance, or (3) to act as balancing measures so that progress in a measure would not result in the degradation of another. Each domain was assigned 20 points, which were distributed across the domain's components based on a consensus of the component's relative importance to overall domain performance (Figure 1). Data from the previous year were used as guidelines for setting performance percentile goals. For example, a goal of 80% in 60 minutes for arrival to physician evaluation meant that 80% of patients should see a physician within 1 hour of arriving at the ED.

Scores were also categorized to correspond to commonly used color descriptors.[17] For each component measure, performance meeting or exceeding the goal fell into the green category. Performances 10 percentage points below the goal fell into the yellow category, and performances below that level fell into the red category. Domain‐level scores and overall composite scores were also assigned colors. Performance at or above 80% (16 on the 20‐point domain scale, or 80 on the 100‐point overall scale) were designated green, scores between 70% and 79% were yellow, and scores below 70% were red.

DOMAINS OF THE PATIENT FLOW COMPOSITE SCORE

ED and ED‐to‐Inpatient Transition

Patient progression from the ED to an inpatient unit was separated into 4 steps (Figure 1A): (1) arrival to physician evaluation, (2) ED physician evaluation to decision to admit, (3) decision to admit to medical doctor (MD) report complete, and (4) registered nurse (RN) report to patient to floor. Four additional metrics included: (5) ED LOS for nonadmitted patients, (6) leaving without being seen (LWBS) rate, (7) ED admission rate, and (8) ED volume.

Arrival to physician evaluation measures time between patient arrival in the ED and self‐assignment by the first doctor or nurse practitioner in the electronic record, with a goal of 80% of patients seen within 60 minutes. The component score is calculated as percent of patients meeting this goal (ie, seen within 60 minutes) component weight. ED physician evaluation to decision to admit measures time from the start of the physician evaluation to the decision to admit, using bed request as a proxy; the goal was 80% within 4 hours. Decision to admit to MD report complete measures time from bed request to patient sign‐out to the inpatient floor, with a goal of 80% within 2 hours. RN report to patient to floor measures time from sign‐out to the patient leaving the ED, with a goal of 80% within 1 hour. ED LOS for nonadmitted patients measures time in the ED for patients who are not admitted, and the goal was 80% in 5 hours. The domain also tracks the LWBS rate, with a goal of keeping it below 3%. Its component score is calculated as percent patients seen component weight. ED admission rate is an adjusting factor for the severity of patients visiting the ED. Its component score is calculated as (percent of patients visiting the ED who are admitted to the hospital 5) component weight. Because the average admission rate is around 20%, the percent admitted is multiplied by 5 to more effectively adjust for high‐severity patients. ED volume is an adjusting factor that accounts for high volume. Its component score is calculated as percent of days in a month with more than 250 visits (a threshold chosen by the ED team) component weight. If these days exceed 50%, that percent would be added to the component score as an additional adjustment for excessive volume.

Bed Management

The bed management domain measures how efficiently and effectively patients are assigned to units and beds using 4 metrics (Figure 1B): (1) bed request to unit assignment, (2) unit assignment to bed assignment, (3) percentage of patients placed on right unit for service, and (4) percent of days with peak occupancy >95%.

Bed request to unit assignment measures time from the ED request for a bed in the electronic system to patient being assigned to a unit, with a goal of 80% of assignments made within 20 minutes. Unit assignment to bed assignment measures time from unit assignment to bed assignment, with a goal of 75% within 25 minutes. Because this goal was set to 75% rather than 80%, this component score was multiplied by 80/75 so that all component scores could be compared on the same scale. Percentage of patients placed on right unit for service is a balancing measure for speed of assignment. Because the goal was set to 90% rather than 80%, this component score was also multiplied by an adjusting factor (80/90) so that all components could be compared on the same scale. Percent of days with peak occupancy >95% is an adjusting measure that reflects that locating an appropriate bed takes longer when the hospital is approaching full occupancy. Its component score is calculated as (percent of days with peak occupancy >95% + 1) component weight. The was added to more effectively adjust for high occupancy. If more than 20% of days had peak occupancy greater than 95%, that percent would be added to the component score as an additional adjustment for excessive capacity.

Discharge Process

The discharge process domain measures the efficiency of patient discharge using 2 metrics (Figure 1C): (1) decision to discharge and (2) homeward bound time.

Decision to discharge tracks when clinicians enter electronic discharge orders. The goal was 50% by 1:30 pm for medical services and 10:30 am for surgical services. This encourages physicians to enter discharge orders early to enable downstream discharge work to begin. The component score is calculated as percent entered by goal time component weight (80/50) to adjust the 50% goal up to 80% so all component scores could be compared on the same scale. Homeward bound time measures the time between the discharge order and room vacancy as entered by the unit clerk, with a goal of 80% of patients leaving within 110 minutes for medical services and 240 minutes for surgical services. This balancing measure captures the fact that entering discharge orders early does not facilitate flow if the patients do not actually leave the hospital.

Room Turnover and Environmental Services Department

The room turnover and ESD domain measures the quality of the room turnover processes using 4 metrics (Figure 1D): (1) discharge to in progress time, (2) in progress to complete time, (3) total discharge to clean time, and (4) room cleanliness.

Discharge to in progress time measures time from patient vacancy until ESD staff enters the room, with a goal of 75% within 35 minutes. Because the goal was set to 75% rather than 80%, this component score was multiplied by 80/75 so all component scores could be compared on the same scale. In progress to complete time measures time as entered in the electronic health record from ESD staff entering the room to the room being clean, with a goal of 75% within 55 minutes. The component score is calculated identically to the previous metric. Total discharge to clean time measures the length of the total process, with a goal of 75% within 90 minutes. This component score was also multiplied by 80/75 so that all component scores could be compared on the same scale. Although this repeats the first 2 measures, given workflow and interface issues with our electronic health record (Epic, Epic Systems Corporation, Verona Wisconsin), it is necessary to include a total end‐to‐end measure in addition to the subparts. Patient and family ratings of room cleanliness serve as balancing measures, with the component score calculated as percent satisfaction component weight (80/85) to adjust the 85% satisfaction goal to 80% so all component scores could be compared on the same scale.

Scheduling and Utilization

The scheduling and utilization domain measures hospital operations and variations in bed utilization using 7 metrics including (Figure 1E): (1) coefficient of variation (CV): scheduled admissions, (2) CV: scheduled admissions for weekdays only, (3) CV: emergent admissions, (4) CV: scheduled occupancy, (5) CV: emergent occupancy, (6) percent emergent admissions with LOS >1 day, and (7) percent of days with peak occupancy 95%.

The CV, standard deviation divided by the mean of a distribution, is a measure of dispersion. Because it is a normalized value reported as a percentage, CV can be used to compare variability when sample sizes differ. CV: scheduled admissions captures the variability in admissions coded as an elective across all days in a month. The raw CV score is the standard deviation of the elective admissions for each day divided by the mean. The component score is (1 CV) component weight. A higher CV indicates greater variability, and yields a lower component score. CV on scheduled and emergent occupancy is derived from peak daily occupancy. Percent emergent admissions with LOS >1 day captures the efficiency of bed use, because high volumes of short‐stay patients increases turnover work. Its component score is calculated as the percent of emergent admissions in a month with LOS >1 day component weight. Percent of days with peak occupancy 95% incentivizes the hospital to avoid full occupancy, because effective flow requires that some beds remain open.[18, 19] Its component score is calculated as the percent of days in the month with peak occupancy 95% component weight. Although a similar measure, percent of days with peak occupancy >95%, was an adjusting factor in the bed management domain, it is included again here, because this factor has a unique effect on both domains.

RESULTS

The balanced scorecard with composite measures provided improvement teams and administrators with a picture of patient flow (Figure 2). The overall score provided a global perspective on patient flow over time and captured trends in performance during various states of hospital occupancy. One trend that it captured was an association between high volume and poor composite scores (Figure 3). Notably, the H1N1 influenza pandemic in the fall of 2009 and the turnover of computer systems in January 2011 can be linked to dips in performance. The changes between fiscal years reflect a shift in baseline metrics.

In addition to the overall composite score, the domain level and individual component scores allowed for more specific evaluation of variables affecting quality of care and enabled targeted improvement activities (Figure 4). For example, in December 2010 and January 2011, room turnover and ESD domain scores dropped, especially in the total discharge to clean time component. In response, the ESD made staffing adjustments, and starting in February 2011, component scores and the domain score improved. Feedback from the scheduling and utilization domain scores also initiated positive change. In August 2010, the CV: scheduled occupancy component score started to drop. In response, certain elective admissions were shifted to weekends to distribute hospital occupancy more evenly throughout the week. By February 2011, the component returned to its goal level. This continual evaluation of performance motivates continual improvement.

DISCUSSION

The use of a patient flow balanced scorecard with composite measurement overcomes pitfalls associated with a single or unaggregated measure. Aggregate scores alone mask important differences and relationships among components.[13] For example, 2 domains may be inversely related, or a provider with an overall average score might score above average in 1 domain but below in another. The composite scorecard, however, shows individual component and domain scores in addition to an aggregate score. The individual component and domain level scores highlight specific areas that need improvement and allow attention to be directed to those areas.

Additionally, a composite score is more likely to engage the range of staff involved in patient flow. Scaling out of 100 points and the red‐yellow‐green model are familiar for operations performance and can be easily understood.[17] Moreover, a composite score allows for dynamic performance goals while maintaining a stable measurement structure. For example, standardized LOS ratios, readmission rates, and denied hospital days can be added to the scorecard to provide more information and balancing measures.

Although balanced scorecards with composites can make holistic performance visible across multiple operational domains, they have some disadvantages. First, because there is a degree of complexity associated with a measure that incorporates multiple aspects of flow, certain elements, such as the relationship between a metric and its balancing measure, may not be readily apparent. Second, composite measures may not provide actionable information if the measure is not clearly related to a process that can be improved.[13, 14] Third, individual metrics may not be replicable between locations, so composites may need to be individualized to each setting.[10, 20]

Improving patient flow is a goal at many hospitals. Although measurement is crucial to identifying and mitigating variations, measuring the multidimensional aspects of flow and their impact on quality is difficult. Our scorecard, with composite measurement, addresses the need for an improved method to assess patient flow and improve quality by tracking care processes simultaneously.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Bhuvaneswari Jayaraman for her contributions to the original calculations for the first version of the composite score.

Disclosures: Internal funds from The Children's Hospital of Philadelphia supported the conduct of this work. The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Patient flow refers to the management and movement of patients in a healthcare facility. Healthcare institutions utilize patient flow analyses to evaluate and improve aspects of the patient experience including safety, effectiveness, efficiency, timeliness, patient centeredness, and equity.[1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8] Hospitals can evaluate patient flow using specific metrics, such as time in emergency department (ED) or percent of discharges completed by a certain time of day. However, no single metric can represent the full spectrum of processes inherent to patient flow. For example, ED length of stay (LOS) is dependent on inpatient occupancy, which is dependent on discharge timeliness. Each of these activities depends on various smaller activities, such as cleaning rooms or identifying available beds.

Evaluating the quality that healthcare organizations deliver is growing in importance.[9] Composite scores are being used increasingly to assess clinical processes and outcomes for professionals and institutions.[10, 11] Where various aspects of performance coexist, composite measures can incorporate multiple metrics into a comprehensive summary.[12, 13, 14, 15, 16] They also allow organizations to track a range of metrics for more holistic, comprehensive evaluations.[9, 13]

This article describes a balanced scorecard with composite scoring used at a large urban children's hospital to evaluate patient flow and direct improvement resources where they are needed most.

METHODS

The Children's Hospital of Philadelphia identified patient flow improvement as an operating plan initiative. Previously, performance was measured with a series of independent measures including time from ED arrival to transfer to the inpatient floor, and time from discharge order to room vacancy. These metrics were dismissed as sole measures of flow because they did not reflect the complexity and interdependence of processes or improvement efforts. There were also concerns that efforts to improve a measure caused unintended consequences for others, which at best lead to little overall improvement, and at worst reduced performance elsewhere in the value chain. For example, to meet a goal time for entering discharge orders, physicians could enter orders earlier. But, if patients were not actually ready to leave, their beds were not made available any earlier. Similarly, bed management staff could rush to meet a goal for speed of unit assignment, but this could cause an increase in patients admitted to the wrong specialty floor.

To address these concerns, a group of physicians, nurses, quality improvement specialists, and researchers designed a patient flow scorecard with composite measurement. Five domains of patient flow were identified: (1) ED and ED‐to‐inpatient transition, (2) bed management, (3) discharge process, (4) room turnover and environmental services department (ESD) activities, and (5) scheduling and utilization. Component measures for each domain were selected for 1 of 3 purposes: (1) to correspond to processes of importance to flow and improvement work, (2) to act as adjusters for factors that affect performance, or (3) to act as balancing measures so that progress in a measure would not result in the degradation of another. Each domain was assigned 20 points, which were distributed across the domain's components based on a consensus of the component's relative importance to overall domain performance (Figure 1). Data from the previous year were used as guidelines for setting performance percentile goals. For example, a goal of 80% in 60 minutes for arrival to physician evaluation meant that 80% of patients should see a physician within 1 hour of arriving at the ED.

Scores were also categorized to correspond to commonly used color descriptors.[17] For each component measure, performance meeting or exceeding the goal fell into the green category. Performances 10 percentage points below the goal fell into the yellow category, and performances below that level fell into the red category. Domain‐level scores and overall composite scores were also assigned colors. Performance at or above 80% (16 on the 20‐point domain scale, or 80 on the 100‐point overall scale) were designated green, scores between 70% and 79% were yellow, and scores below 70% were red.

DOMAINS OF THE PATIENT FLOW COMPOSITE SCORE

ED and ED‐to‐Inpatient Transition

Patient progression from the ED to an inpatient unit was separated into 4 steps (Figure 1A): (1) arrival to physician evaluation, (2) ED physician evaluation to decision to admit, (3) decision to admit to medical doctor (MD) report complete, and (4) registered nurse (RN) report to patient to floor. Four additional metrics included: (5) ED LOS for nonadmitted patients, (6) leaving without being seen (LWBS) rate, (7) ED admission rate, and (8) ED volume.

Arrival to physician evaluation measures time between patient arrival in the ED and self‐assignment by the first doctor or nurse practitioner in the electronic record, with a goal of 80% of patients seen within 60 minutes. The component score is calculated as percent of patients meeting this goal (ie, seen within 60 minutes) component weight. ED physician evaluation to decision to admit measures time from the start of the physician evaluation to the decision to admit, using bed request as a proxy; the goal was 80% within 4 hours. Decision to admit to MD report complete measures time from bed request to patient sign‐out to the inpatient floor, with a goal of 80% within 2 hours. RN report to patient to floor measures time from sign‐out to the patient leaving the ED, with a goal of 80% within 1 hour. ED LOS for nonadmitted patients measures time in the ED for patients who are not admitted, and the goal was 80% in 5 hours. The domain also tracks the LWBS rate, with a goal of keeping it below 3%. Its component score is calculated as percent patients seen component weight. ED admission rate is an adjusting factor for the severity of patients visiting the ED. Its component score is calculated as (percent of patients visiting the ED who are admitted to the hospital 5) component weight. Because the average admission rate is around 20%, the percent admitted is multiplied by 5 to more effectively adjust for high‐severity patients. ED volume is an adjusting factor that accounts for high volume. Its component score is calculated as percent of days in a month with more than 250 visits (a threshold chosen by the ED team) component weight. If these days exceed 50%, that percent would be added to the component score as an additional adjustment for excessive volume.

Bed Management

The bed management domain measures how efficiently and effectively patients are assigned to units and beds using 4 metrics (Figure 1B): (1) bed request to unit assignment, (2) unit assignment to bed assignment, (3) percentage of patients placed on right unit for service, and (4) percent of days with peak occupancy >95%.

Bed request to unit assignment measures time from the ED request for a bed in the electronic system to patient being assigned to a unit, with a goal of 80% of assignments made within 20 minutes. Unit assignment to bed assignment measures time from unit assignment to bed assignment, with a goal of 75% within 25 minutes. Because this goal was set to 75% rather than 80%, this component score was multiplied by 80/75 so that all component scores could be compared on the same scale. Percentage of patients placed on right unit for service is a balancing measure for speed of assignment. Because the goal was set to 90% rather than 80%, this component score was also multiplied by an adjusting factor (80/90) so that all components could be compared on the same scale. Percent of days with peak occupancy >95% is an adjusting measure that reflects that locating an appropriate bed takes longer when the hospital is approaching full occupancy. Its component score is calculated as (percent of days with peak occupancy >95% + 1) component weight. The was added to more effectively adjust for high occupancy. If more than 20% of days had peak occupancy greater than 95%, that percent would be added to the component score as an additional adjustment for excessive capacity.

Discharge Process

The discharge process domain measures the efficiency of patient discharge using 2 metrics (Figure 1C): (1) decision to discharge and (2) homeward bound time.

Decision to discharge tracks when clinicians enter electronic discharge orders. The goal was 50% by 1:30 pm for medical services and 10:30 am for surgical services. This encourages physicians to enter discharge orders early to enable downstream discharge work to begin. The component score is calculated as percent entered by goal time component weight (80/50) to adjust the 50% goal up to 80% so all component scores could be compared on the same scale. Homeward bound time measures the time between the discharge order and room vacancy as entered by the unit clerk, with a goal of 80% of patients leaving within 110 minutes for medical services and 240 minutes for surgical services. This balancing measure captures the fact that entering discharge orders early does not facilitate flow if the patients do not actually leave the hospital.

Room Turnover and Environmental Services Department

The room turnover and ESD domain measures the quality of the room turnover processes using 4 metrics (Figure 1D): (1) discharge to in progress time, (2) in progress to complete time, (3) total discharge to clean time, and (4) room cleanliness.

Discharge to in progress time measures time from patient vacancy until ESD staff enters the room, with a goal of 75% within 35 minutes. Because the goal was set to 75% rather than 80%, this component score was multiplied by 80/75 so all component scores could be compared on the same scale. In progress to complete time measures time as entered in the electronic health record from ESD staff entering the room to the room being clean, with a goal of 75% within 55 minutes. The component score is calculated identically to the previous metric. Total discharge to clean time measures the length of the total process, with a goal of 75% within 90 minutes. This component score was also multiplied by 80/75 so that all component scores could be compared on the same scale. Although this repeats the first 2 measures, given workflow and interface issues with our electronic health record (Epic, Epic Systems Corporation, Verona Wisconsin), it is necessary to include a total end‐to‐end measure in addition to the subparts. Patient and family ratings of room cleanliness serve as balancing measures, with the component score calculated as percent satisfaction component weight (80/85) to adjust the 85% satisfaction goal to 80% so all component scores could be compared on the same scale.

Scheduling and Utilization

The scheduling and utilization domain measures hospital operations and variations in bed utilization using 7 metrics including (Figure 1E): (1) coefficient of variation (CV): scheduled admissions, (2) CV: scheduled admissions for weekdays only, (3) CV: emergent admissions, (4) CV: scheduled occupancy, (5) CV: emergent occupancy, (6) percent emergent admissions with LOS >1 day, and (7) percent of days with peak occupancy 95%.

The CV, standard deviation divided by the mean of a distribution, is a measure of dispersion. Because it is a normalized value reported as a percentage, CV can be used to compare variability when sample sizes differ. CV: scheduled admissions captures the variability in admissions coded as an elective across all days in a month. The raw CV score is the standard deviation of the elective admissions for each day divided by the mean. The component score is (1 CV) component weight. A higher CV indicates greater variability, and yields a lower component score. CV on scheduled and emergent occupancy is derived from peak daily occupancy. Percent emergent admissions with LOS >1 day captures the efficiency of bed use, because high volumes of short‐stay patients increases turnover work. Its component score is calculated as the percent of emergent admissions in a month with LOS >1 day component weight. Percent of days with peak occupancy 95% incentivizes the hospital to avoid full occupancy, because effective flow requires that some beds remain open.[18, 19] Its component score is calculated as the percent of days in the month with peak occupancy 95% component weight. Although a similar measure, percent of days with peak occupancy >95%, was an adjusting factor in the bed management domain, it is included again here, because this factor has a unique effect on both domains.

RESULTS

The balanced scorecard with composite measures provided improvement teams and administrators with a picture of patient flow (Figure 2). The overall score provided a global perspective on patient flow over time and captured trends in performance during various states of hospital occupancy. One trend that it captured was an association between high volume and poor composite scores (Figure 3). Notably, the H1N1 influenza pandemic in the fall of 2009 and the turnover of computer systems in January 2011 can be linked to dips in performance. The changes between fiscal years reflect a shift in baseline metrics.

In addition to the overall composite score, the domain level and individual component scores allowed for more specific evaluation of variables affecting quality of care and enabled targeted improvement activities (Figure 4). For example, in December 2010 and January 2011, room turnover and ESD domain scores dropped, especially in the total discharge to clean time component. In response, the ESD made staffing adjustments, and starting in February 2011, component scores and the domain score improved. Feedback from the scheduling and utilization domain scores also initiated positive change. In August 2010, the CV: scheduled occupancy component score started to drop. In response, certain elective admissions were shifted to weekends to distribute hospital occupancy more evenly throughout the week. By February 2011, the component returned to its goal level. This continual evaluation of performance motivates continual improvement.

DISCUSSION

The use of a patient flow balanced scorecard with composite measurement overcomes pitfalls associated with a single or unaggregated measure. Aggregate scores alone mask important differences and relationships among components.[13] For example, 2 domains may be inversely related, or a provider with an overall average score might score above average in 1 domain but below in another. The composite scorecard, however, shows individual component and domain scores in addition to an aggregate score. The individual component and domain level scores highlight specific areas that need improvement and allow attention to be directed to those areas.

Additionally, a composite score is more likely to engage the range of staff involved in patient flow. Scaling out of 100 points and the red‐yellow‐green model are familiar for operations performance and can be easily understood.[17] Moreover, a composite score allows for dynamic performance goals while maintaining a stable measurement structure. For example, standardized LOS ratios, readmission rates, and denied hospital days can be added to the scorecard to provide more information and balancing measures.

Although balanced scorecards with composites can make holistic performance visible across multiple operational domains, they have some disadvantages. First, because there is a degree of complexity associated with a measure that incorporates multiple aspects of flow, certain elements, such as the relationship between a metric and its balancing measure, may not be readily apparent. Second, composite measures may not provide actionable information if the measure is not clearly related to a process that can be improved.[13, 14] Third, individual metrics may not be replicable between locations, so composites may need to be individualized to each setting.[10, 20]

Improving patient flow is a goal at many hospitals. Although measurement is crucial to identifying and mitigating variations, measuring the multidimensional aspects of flow and their impact on quality is difficult. Our scorecard, with composite measurement, addresses the need for an improved method to assess patient flow and improve quality by tracking care processes simultaneously.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Bhuvaneswari Jayaraman for her contributions to the original calculations for the first version of the composite score.

Disclosures: Internal funds from The Children's Hospital of Philadelphia supported the conduct of this work. The authors report no conflicts of interest.

- AHA Solutions. Patient Flow Challenges Assessment 2009. Chicago, IL: American Hospital Association; 2009.

- , , , et al. The impact of emergency department crowding measures on time to antibiotics for patients with community‐acquired pneumonia. Ann Emerg Med. 2007;50(5):510–516.

- . Practice variation: implications for our health care system. Manag Care. 2004;13(9 suppl):3–7.

- . Managing variability in patient flow is the key to improving access to care, nursing staffing, quality of care, and reducing its cost. Paper presented at: Institute of Medicine; June 24, 2004; Washington, DC.

- , , . Developing models for patient flow and daily surge capacity research. Acad Emerg Med. 2006;13(11):1109–1113.

- , , , , . Patient flow variability and unplanned readmissions to an intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2009;37(11):2882–2887.

- , , , , , . Scheduled admissions and high occupancy at a children's hospital. J Hosp Med. 2011;6(2):81–87.

- , , . Frequent overcrowding in US emergency departments. Acad Emerg Med. 2001;8(2):151–155.

- Institute of Medicine. Performance measurement: accelerating improvement. Available at: http://www.iom.edu/Reports/2005/Performance‐Measurement‐Accelerating‐Improvement.aspx. Published December 1, 2005. Accessed December 5, 2012.

- , , , . Emergency department performance measures and benchmarking summit. Acad Emerg Med. 2006;13(10):1074–1080.

- . The Surgical Infection Prevention and Surgical Care Improvement Projects: promises and pitfalls. Am Surg. 2006;72(11):1010–1016; discussion 1021–1030, 1133–1048.

- , , . Patient safety quality indicators. Composite measures workgroup. Final report. Rockville, MD; Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2008.

- , , , et al. ACCF/AHA 2010 position statement on composite measures for healthcare performance assessment: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on performance measures (Writing Committee to develop a position statement on composite measures). Circulation. 2010;121(15):1780–1791.

- , . A five‐point checklist to help performance reports incentivize improvement and effectively guide patients. Health Aff (Millwood). 2012;31(3):612–618.

- , , , , . Composite measures for profiling hospitals on surgical morbidity. Ann Surg. 2013;257(1):67–72.

- , . All‐or‐none measurement raises the bar on performance. JAMA. 2006;295(10):1168–1170.

- , , , et al. Quality improvement. Red light‐green light: from kids' game to discharge tool. Healthc Q. 2011;14:77–81.

- , , , . Myths of ideal hospital occupancy. Med J Aust. 2010;192(1):42–43.

- , . Emergency department overcrowding in the United States: an emerging threat to patient safety and public health. Emerg Med J. 2003;20(5):402–405.

- , , , . Emergency department crowding: consensus development of potential measures. Ann Emerg Med. 2003;42(6):824–834.

- AHA Solutions. Patient Flow Challenges Assessment 2009. Chicago, IL: American Hospital Association; 2009.

- , , , et al. The impact of emergency department crowding measures on time to antibiotics for patients with community‐acquired pneumonia. Ann Emerg Med. 2007;50(5):510–516.

- . Practice variation: implications for our health care system. Manag Care. 2004;13(9 suppl):3–7.

- . Managing variability in patient flow is the key to improving access to care, nursing staffing, quality of care, and reducing its cost. Paper presented at: Institute of Medicine; June 24, 2004; Washington, DC.

- , , . Developing models for patient flow and daily surge capacity research. Acad Emerg Med. 2006;13(11):1109–1113.

- , , , , . Patient flow variability and unplanned readmissions to an intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2009;37(11):2882–2887.

- , , , , , . Scheduled admissions and high occupancy at a children's hospital. J Hosp Med. 2011;6(2):81–87.

- , , . Frequent overcrowding in US emergency departments. Acad Emerg Med. 2001;8(2):151–155.

- Institute of Medicine. Performance measurement: accelerating improvement. Available at: http://www.iom.edu/Reports/2005/Performance‐Measurement‐Accelerating‐Improvement.aspx. Published December 1, 2005. Accessed December 5, 2012.

- , , , . Emergency department performance measures and benchmarking summit. Acad Emerg Med. 2006;13(10):1074–1080.

- . The Surgical Infection Prevention and Surgical Care Improvement Projects: promises and pitfalls. Am Surg. 2006;72(11):1010–1016; discussion 1021–1030, 1133–1048.

- , , . Patient safety quality indicators. Composite measures workgroup. Final report. Rockville, MD; Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2008.

- , , , et al. ACCF/AHA 2010 position statement on composite measures for healthcare performance assessment: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on performance measures (Writing Committee to develop a position statement on composite measures). Circulation. 2010;121(15):1780–1791.

- , . A five‐point checklist to help performance reports incentivize improvement and effectively guide patients. Health Aff (Millwood). 2012;31(3):612–618.

- , , , , . Composite measures for profiling hospitals on surgical morbidity. Ann Surg. 2013;257(1):67–72.

- , . All‐or‐none measurement raises the bar on performance. JAMA. 2006;295(10):1168–1170.

- , , , et al. Quality improvement. Red light‐green light: from kids' game to discharge tool. Healthc Q. 2011;14:77–81.

- , , , . Myths of ideal hospital occupancy. Med J Aust. 2010;192(1):42–43.

- , . Emergency department overcrowding in the United States: an emerging threat to patient safety and public health. Emerg Med J. 2003;20(5):402–405.

- , , , . Emergency department crowding: consensus development of potential measures. Ann Emerg Med. 2003;42(6):824–834.

Matching Workforce to Workload

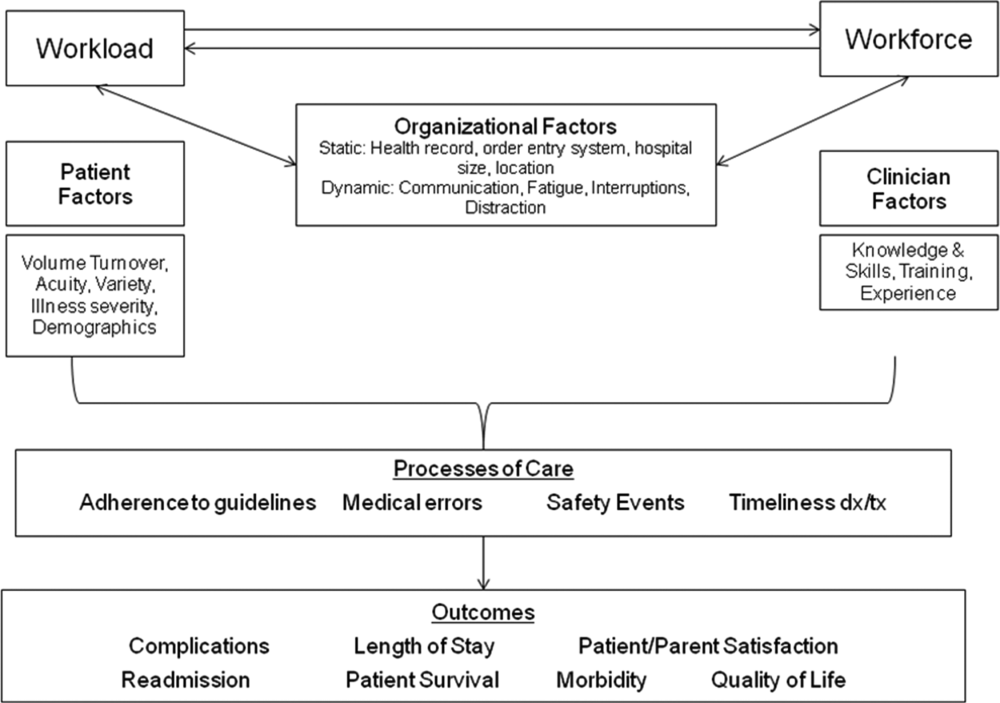

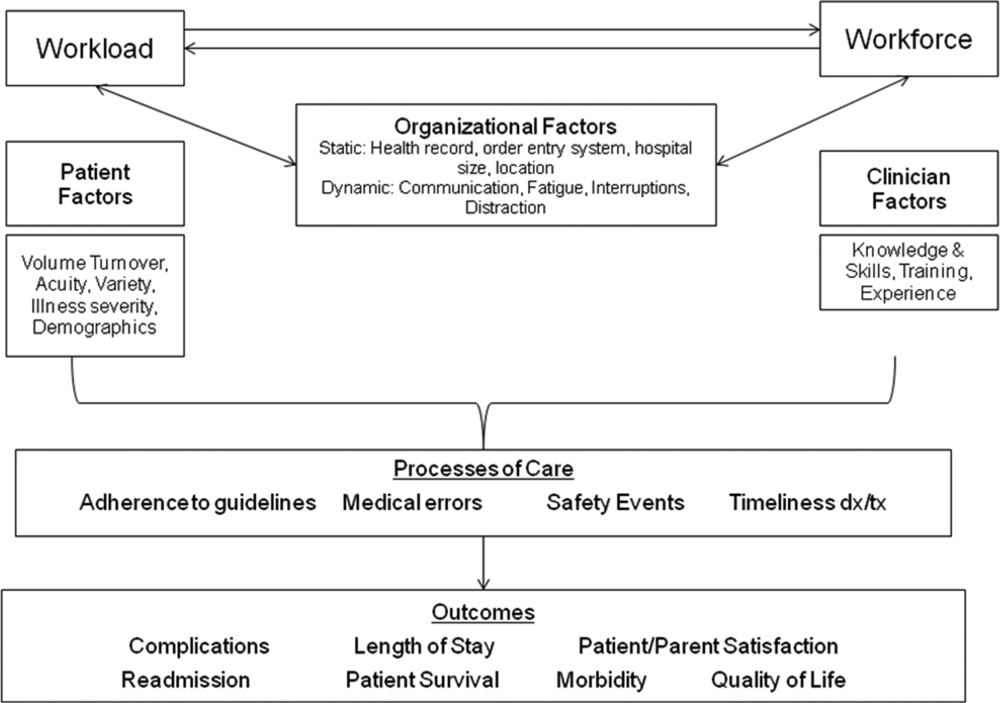

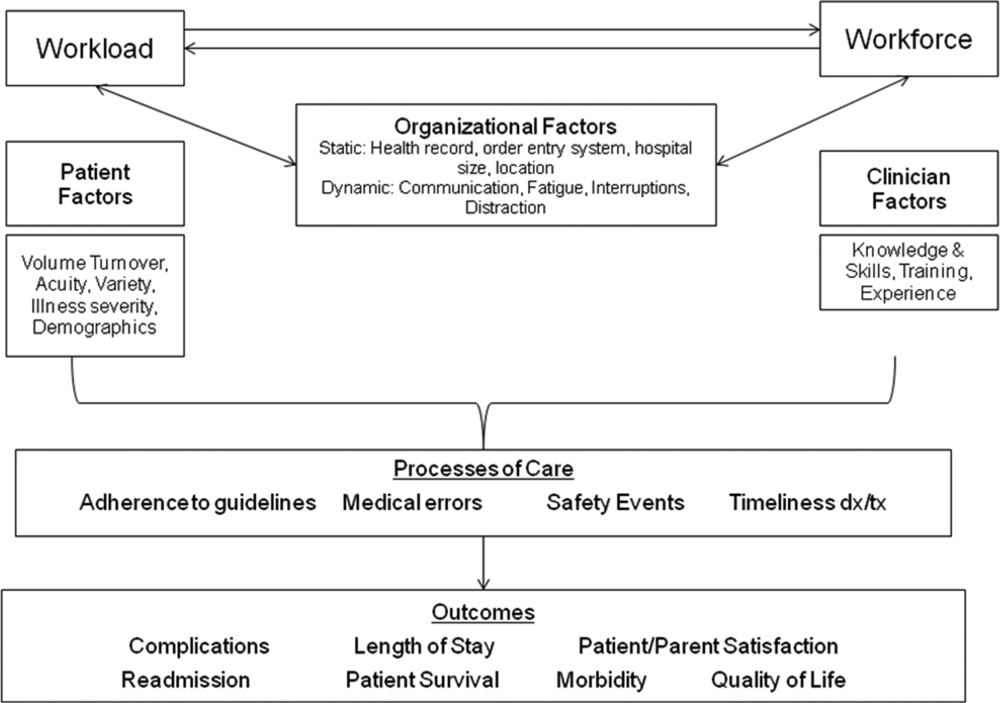

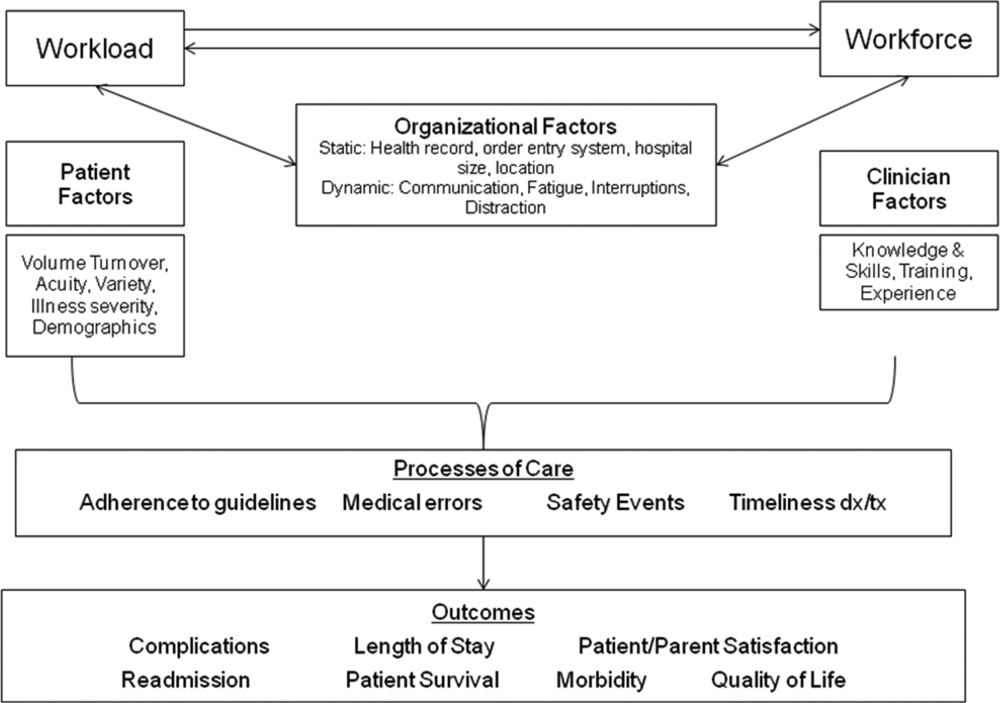

Healthcare systems face many clinical and operational challenges in optimizing the quality of patient care across the domains of safety, effectiveness, efficiency, timeliness, patient‐centeredness, and equity.[1] They must also balance staff satisfaction, and in academic settings, the education of trainees. In inpatient settings, the process of care encompasses many microsystems, and clinical outcomes are the result of a combination of endogenous patient factors, the capabilities of clinical staff, as well as the static and dynamic organizational characteristics of the systems delivering care.[2, 3, 4, 5] Static organizational characteristics include hospital type and size, whereas dynamic organizational characteristics include communications between staff, staff fatigue, interruptions in care, and other factors that impact patient care and clinical outcomes (Figure 1).[2] Two major components of healthcare microsystems are workload and workforce.

A principle in operations management describes the need to match capacity (eg, workforce) to demand (eg, workload) to optimize efficiency.[6] This is particularly relevant in healthcare settings, where an excess of workload for the available workforce may negatively impact processes and outcomes of patient care and resident learning. These problems can arise from fatigue and strain from a heavy cognitive load, or from interruptions, distractions, and ineffective communication.[7, 8, 9, 10, 11] Conversely, in addition to being inefficient, an excess of workforce is financially disadvantageous for the hospital and reduces trainees' opportunities for learning.

Workload represents patient demand for clinical resources, including staff time and effort.[5, 12] Its elements include volume, turnover, acuity, and patient variety. Patient volume is measured by census.[12] Turnover refers to the number of admissions, discharges, and transfers in a given time period.[12] Acuity reflects the intensity of patient needs,[12] and variety represents the heterogeneity of those needs. These 4 workload factors are highly variable across locations and highly dynamic, even within a fixed location. Thus, measuring workload to assemble the appropriate workforce is challenging.

Workforce is comprised of clinical and nonclinical staff members who directly or indirectly provide services to patients. In this article, clinicians who obtain histories, conduct physical exams, write admission and progress notes, enter orders, communicate with consultants, and obtain consents are referred to as front‐line ordering clinicians (FLOCs). FLOCs perform activities listed in Table 1. Historically, in teaching hospitals, FLOCs consisted primarily of residents. More recently, FLOCs include nurse practitioners, physician assistants, house physicians, and hospitalists (when providing direct care and not supervising trainees).[13] In academic settings, supervising physicians (eg, senior supervising residents, fellows, or attendings), who are usually on the floor only in a supervisory capacity, may also contribute to FLOC tasks for part of their work time.

| FLOC Responsibilities | FLOC Personnel |

|---|---|

| |

| Admission history and physical exam | Residents |

| Daily interval histories | Nurse practitioners |

| Daily physical exams | Physician assistants |

| Obtaining consents | House physicians |

| Counseling, guidance, and case management | Hospitalists (when not in supervisory role) |

| Performing minor procedures | Fellows (when not in supervisory role) |

| Ordering, performing and interpreting diagnostic tests | Attendings (when not in supervisory role) |

| Writing prescriptions | |

Though matching workforce to workload is essential for hospital efficiency, staff satisfaction, and optimizing patient outcomes, hospitals currently lack a means to measure and match dynamic workload and workforce factors. This is particularly problematic at large children's hospitals, where high volumes of admitted patients stay for short amounts of time (less than 2 or 3 days).[14] This frequent turnover contributes significantly to workload. We sought to address this issue as part of a larger effort to redefine the care model at our urban, tertiary care children's hospital. This article describes our work to develop and obtain consensus for use of a tool to dynamically match FLOC workforce to clinical workload in a variety of inpatient settings.

METHODS

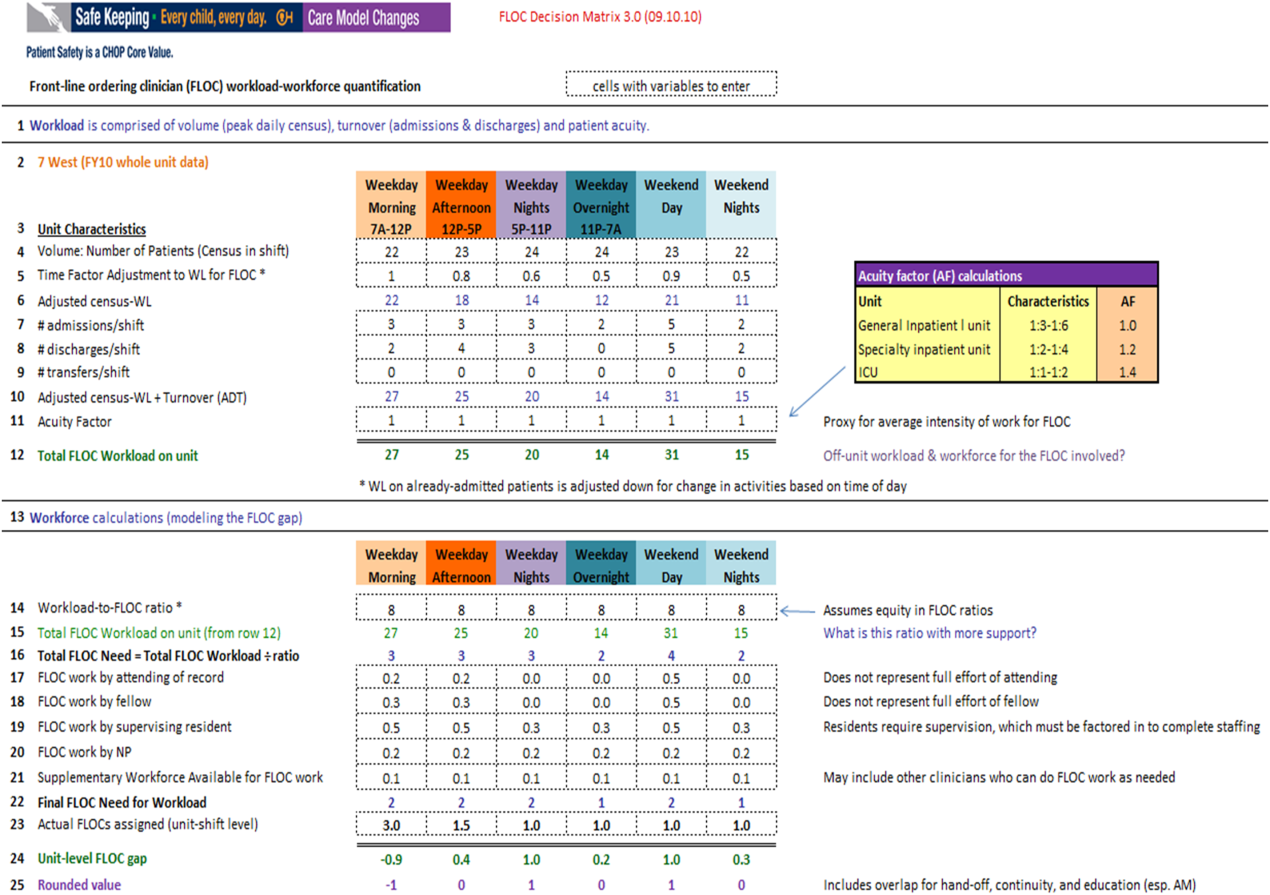

We undertook an iterative, multidisciplinary approach to develop the Care Model Matrix tool (Figure 2). The process involved literature reviews,[2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14] discussions with clinical leadership, and repeated validation sessions. Our focus was at the level of the patient nursing units, which are the discrete areas in a hospital where patient care is delivered and physician teams are organized. We met with physicians and nurses from every clinical care area at least twice to reach consensus on how to define model inputs, decide how to quantify those inputs for specific microsystems, and to validate whether model outputs seemed consistent with clinicians' experiences on the floors. For example, if the model indicated that a floor was short 1 FLOC during the nighttime period, relevant staff confirmed that this was consistent with their experience.

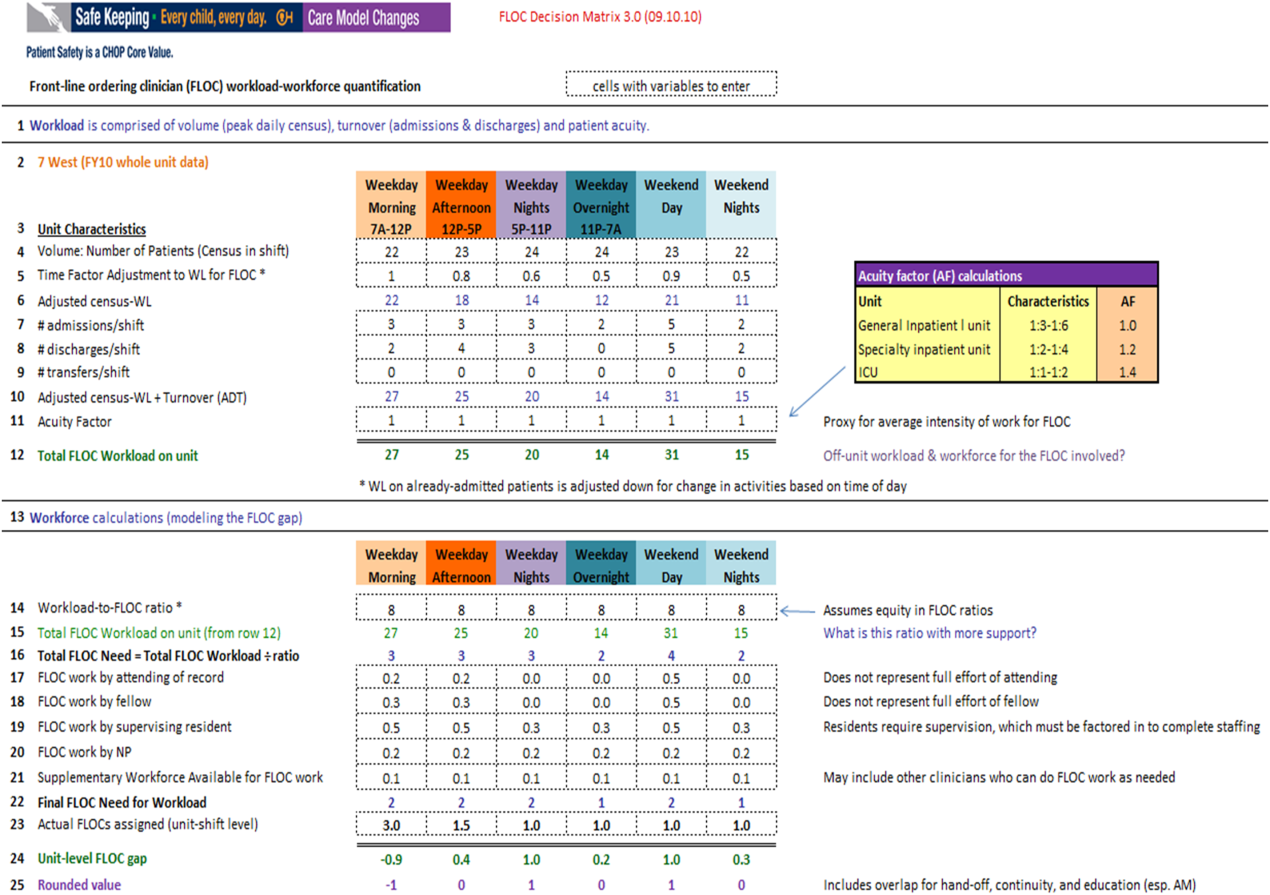

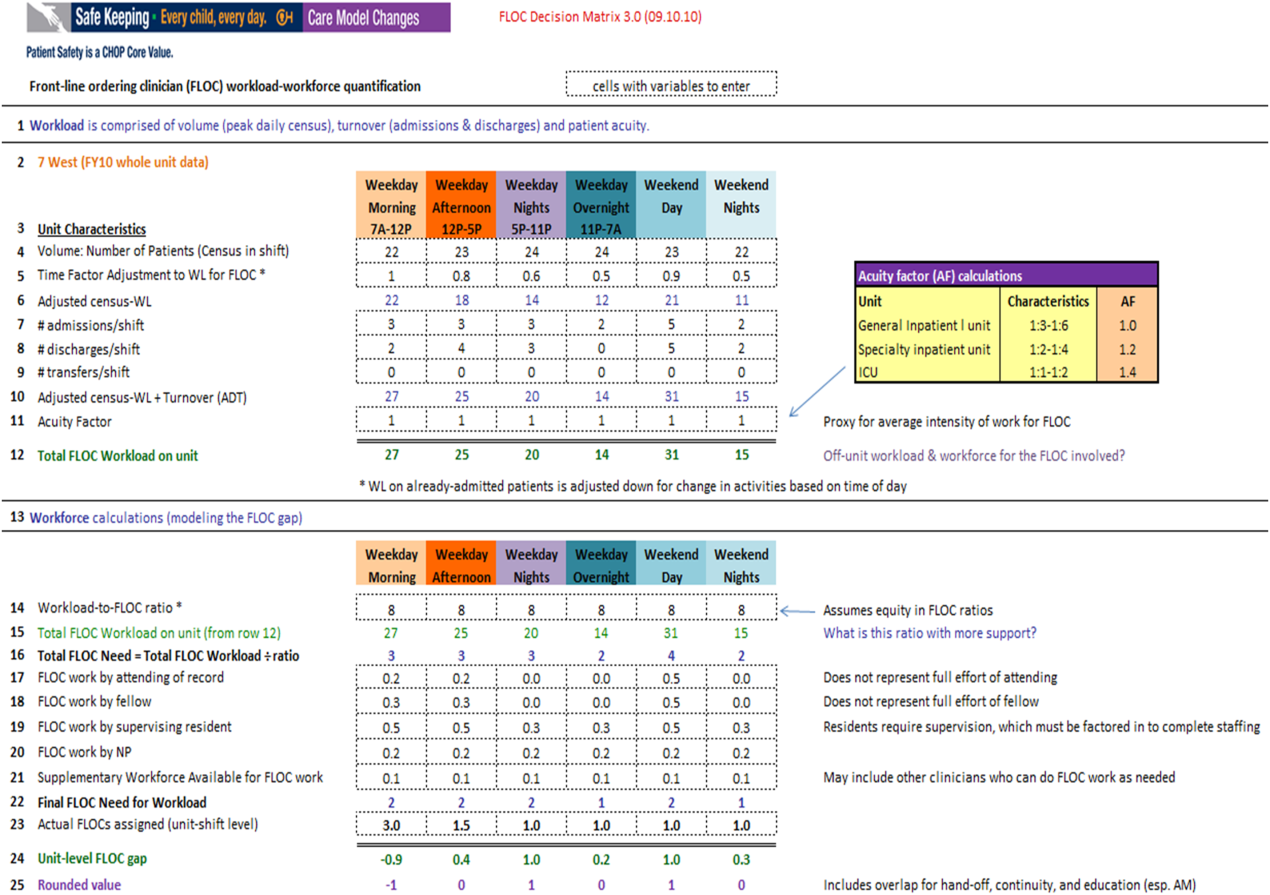

Quantifying Workload

In quantifying FLOC workload, we focused on 3 elements: volume, turnover, and acuity.[12] Volume is equal to the patient census at a moment in time for a particular floor or unit. Census data were extracted from the hospital's admission‐discharge‐transfer (ADT) system (Epic, Madison, WI). Timestamps for arrival and departure are available for each unit. These data were used to calculate census estimates for intervals of time that corresponded to activities such as rounds, conferences, or sign‐outs, and known variations in patient flow. Intervals for weekdays were: 7 am to 12 pm, 12 pm to 5 pm, 5 pm to 11 pm, and 11 pm to 7 am. Intervals for weekends were: 7 am to 7 pm (daytime), and 7 pm to 7 am (nighttime). Census data for each of the 6 intervals were averaged over 1 year.

In addition to patient volume, discussions with FLOCs highlighted the need to account for inpatients having different levels of need at different points throughout the day. For example, patients require the most attention in the morning, when FLOCs need to coordinate interval histories, conduct exams, enter orders, call consults, and interpret data. In the afternoon and overnight, patients already in beds have relatively fewer needs, especially in nonintensive care unit (ICU) settings. To adjust census data to account for time of day, a time factor was added, with 1 representing the normalized full morning workload (Figure 2, line 5). Based on clinical consensus, this time factor decreased over the course of the day, more so for non‐ICU patients than for ICU patients. For example, a time factor of 0.5 for overnight meant that patients in beds on that unit generated half as much work overnight as those same patients would in the morning when the time factor was set to 1. Multiplication of number of patients and the time factor equals adjusted census workload, which reflects what it felt like for FLOCs to care for that number of patients at that time. Specifically, if there were 20 patients at midnight with a time factor of 0.5, the patients generated a workload equal to 20 0.5=10 workload units (WU), whereas in the morning the same actual number of patients would generate a workload of 20 1=20 WU.

The ADT system was also used to track information about turnover, including number of admissions, discharges, and transfers in or out of each unit during each interval. Each turnover added to the workload count to reflect the work involved in admitting, transferring, or discharging a patient (Figure 2, lines 79). For example, a high‐turnover floor might have 20 patients in beds, with 4 admissions and 4 discharges in a given time period. Based on clinical consensus, it was determined that the work involved in managing each turnover would count as an additional workload element, yielding an adjusted census workload+turnover score of (20 1)+4+4=28 WU. Although only 20 patients would be counted in a static census during this time, the adjusted workload score was 28 WU. Like the time factor, this adjustment helps provide a feels‐like barometer.

Finally, this workload score is multiplied by an acuity factor that considers the intensity of need for patients on a unit (Figure 2, line 11). We stratified acuity based on whether the patient was in a general inpatient unit, a specialty unit, or an ICU, and assigned acuity factors based on observations of differences in intensity between those units. The acuity factor was normalized to 1 for patients on a regular inpatient floor. Specialty care areas were 20% higher (1.2), and ICUs were 40% higher (1.4). These differentials were estimated based on clinician experience and knowledge of current FLOC‐to‐patient and nurse‐to‐patient ratios.

Quantifying Workforce

To quantify workforce, we assumed that each FLOC, regardless of type, would be responsible for the same number of workload units. Limited evidence and research exist regarding ideal workload‐to‐staff ratios for FLOCs. Published literature and hospital experience suggest that the appropriate volume per trainee for non‐ICU inpatient care in medicine and pediatrics is between 6 and 10 patients (not workload units) per trainee.[13, 15, 16, 17, 18] Based on these data, we chose 8 workload units as a reasonable workload allocation per FLOC. This ratio appears in the matrix as a modifiable variable (Figure 2, line 14). We then divided total FLOC workload (Figure 2, line 15) from our workload calculations by 8 to determine total FLOC need (Figure 2, line 16). Because some of the workload captured in total FLOC need would be executed by personnel who are typically classified as non‐FLOCs, such as attendings, fellows, and supervising residents, we quantified the contributions of each of these non‐FLOCs through discussion with clinical leaders from each floor. For example, if an attending physician wrote complete notes on weekends, he or she would be contributing to FLOC work for that location on those days. A 0.2 contribution under attendings would mean that an attending contributed an amount of work equivalent to 20% of a FLOC. We subtracted contributions of non‐FLOCs from the total FLOC need to determine final FLOC need (Figure 2, line 22). Last, we subtracted the actual number of FLOCs assigned to a unit for a specific time period from the final FLOC need to determine the unit‐level FLOC gap at that time (Figure 2, line 24).

RESULTS

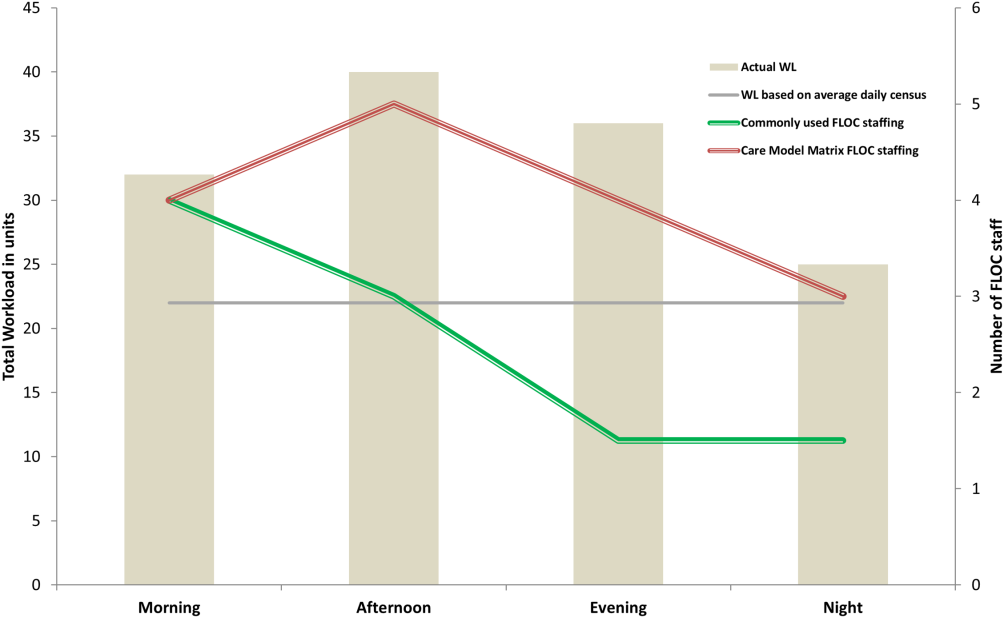

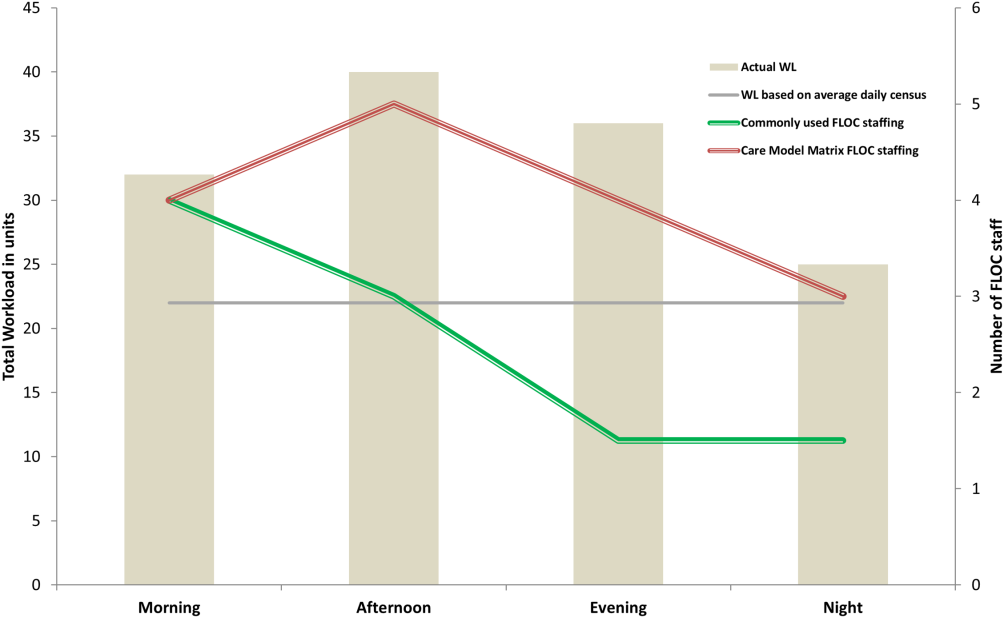

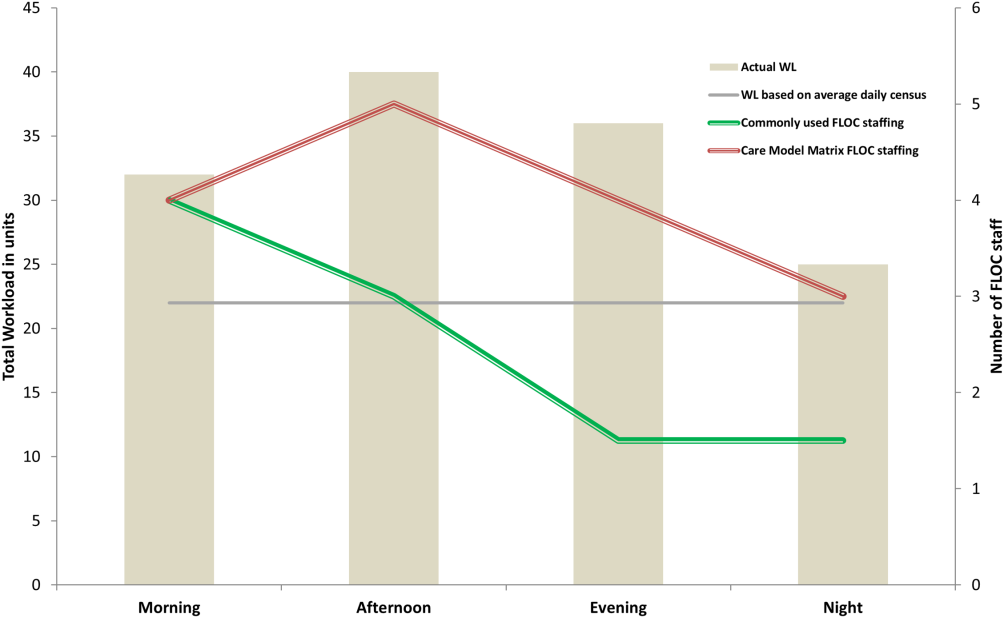

The Care Model Matrix compares predicted workforce need and actual workforce assignments, while considering the contributions of non‐FLOCs to FLOC work in various inpatient care settings. Figure 3 shows graphical representations of FLOC staffing models. The green line shows the traditional approach, and the red line shows the dynamic approach using the Care Model Matrix. The dynamic approach better captures variations in workload.

We presented the tool at over 25 meetings in 14 hospital divisions, and received widespread acceptance among physician, nursing, and administrative leadership. In addition, the hospital has used the tool to identify gaps in FLOC coverage and guide hiring and staffing decisions. Each clinical area also used the tool to review staffing for the 2012 academic year. Though a formal evaluation of the tool has not been conducted, feedback from attending physicians and FLOCs has been positive. Specifically, staffing adjustments have increased the available workforce in the afternoons and on weekends, when floors were previously perceived to be understaffed.

DISCUSSION

Hospitals depend upon a large, diverse workforce to manage and care for patients. In any system there will be a threshold at which workload exceeds the available workforce. In healthcare delivery settings, this can harm patient care and resident education.[12, 19] Conversely, a workforce that is larger than necessary is inefficient. If hospitals can define and measure relevant elements to better match workforce to workload, they can avoid under or over supplying staff, and mitigate the risks associated with an overburdened workforce or the waste of unused capacity. It also enables more flexible care models to dynamically match resources to needs.

The Care Model Matrix is a flexible, objective tool that quantifies multidimensional aspects of workload and workforce. With the tool, hospitals can use historic data on census, turnover, and acuity to predict workload and staffing needs at specific time periods. Managers can also identify discrepancies between workload and workforce, and match them more efficiently during the day.

The tool, which uses multiple modifiable variables, can be adapted to a variety of academic and community inpatient settings. Although our sample numbers in Figure 2 represent census, turnover, acuity, and workload‐to‐FLOC ratios at our hospital, other hospitals can adjust the model to reflect their numbers. The flexibility to add new factors as elements of workload or workforce enhances usability. For example, the model can be modified to capture other factors that affect staffing needs such as frequency of handoffs[11] and the staff's level of education or experience.

There are, however, numerous challenges associated with matching FLOC staffing to workload. Although there is a 24‐hour demand for FLOC coverage, unlike nursing, ideal FLOC to patients or workload ratios have not been established. Academic hospitals may experience additional challenges, because trainees have academic responsibilities in addition to clinical roles. Although trainees are included in FLOC counts, they are unavailable during certain didactic times, and their absence may affect the workload balance.

Another challenge associated with dynamically adjusting workforce to workload is that most hospitals do not have extensive flex or surge capacity. One way to address this is to have FLOCs choose days when they will be available as backup for a floor that is experiencing a heavier than expected workload. Similarly, when floors are experiencing a lighter than expected workload, additional FLOCs can be diverted to administrative tasks, to other floors in need of extra capacity, or sent home with the expectation that the day will be made up when the floor is experiencing a heavier workload.

Though the tool provides numerous advantages, there are several limitations to consider. First, the time and acuity factors used in the workload calculation, as well as the non‐FLOC contribution estimates and numbers reflecting desired workload per FLOC used in the workforce calculation, are somewhat subjective estimations based on observation and staff consensus. Thus, even though the tool's approach should be generalizable to any hospital, the specific values may not be. Therefore, other hospitals may need to change these values based on their unique situations. It is also worth noting that the flexibility of the tool presents both a virtue and potential vice. Those using the tool must agree upon a standard to define units so inconsistent definitions do not introduce unjustified discrepancies in workload. Second, the current tool does not consider the costs and benefits of different staffing approaches. Different types of FLOCs may handle workload differently, so an ideal combination of FLOC types should be considered in future studies. Third, although this work focused on matching FLOCs to workload, the appropriate matching of other workforce members is also essential to maximizing efficiency and patient care. Finally, because the tool has not yet been tested against outcomes, adhering to the tool's suggested ratios cannot necessary guarantee optimal outcomes in terms of patient care or provider satisfaction. Rather, the tool is designed to detect mismatches of workload and workforce based on desired workload levels, defined through local consensus.

CONCLUSION

We sought to develop a tool that quantifies workload and workforce to help our freestanding children's hospital predict and plan for future staffing needs. We created a tool that is objective and flexible, and can be applied to a variety of academic and community inpatient settings to identify mismatches of workload and workforce at discrete time intervals. However, given that the tool's recommendations are sensitive to model inputs that are based on local consensus, further research is necessary to test the validity and generalizability of the tool in various settings. Model inputs may need to be calibrated over time to maximize the tool's usefulness in a particular setting. Further study is also needed to determine how the tool directly impacts patient and provider satisfaction and the quality of care delivered.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the dozens of physicians and nurses for their involvement in the development of the Care Model Matrix through repeated meetings and dialog. The authors thank Sheyla Medina, Lawrence Chang, and Jennifer Jonas for their assistance in the production of this article.

Disclosures: Internal funds from The Children's Hospital of Philadelphia supported the conduct of this work. The authors have no financial interests, relationships, affiliations, or potential conflicts of interest relevant to the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript to disclose.

- . A user's manual for the IOM's “quality chasm” report. Health Aff. 2002;21(3):80–90.

- . Human error: models and management. BMJ. 2000;320(7237):768–770.

- , . Knowledge for Improvement: Improving Quality in the Micro‐systems of Care. in Providing Quality of Care in a Cost‐Focused Environment, Goldfield N, Nach DB (eds.), Gaithersburg, Maryland: Aspen Publishers, Inc. 1999;75–88.

- World Alliance For Patient Safety Drafting Group1, , , , et al. Towards an International Classification for Patient Safety: the conceptual framework. Int J Qual Health Care. F2009;21(1):2–8.

- , . Impact of workload on service time and patient safety: an econometric analysis of hospital operations. Manage Sci. 2009;55(9):1486–1498.

- , . Matching Supply With Demand: An Introduction to Operations Management. New York, NY: McGraw‐Hill; 2006.

- , . Operational failures and interruptions in hospital nursing. Health Serv Res. 2006;41:643–662.

- , , , , . Association of interruptions with an increased risk and severity of medication administration errors. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170(8):683–690.

- . The impact of fatigue on patient safety. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2006;53(6):1135–1153.

- , , , , . Effects of hospital care environment on patient mortality and nurse outcomes. J Nurs Adm. 2009;39(7/8):S45–S51.

- , , , , , . Perspective: beyond counting hours: the importance of supervision, professionalism, transitions of care, and workload in residency training. Acad Med. 2012;87(7):883–888.

- , , , et al. Hospital workload and adverse events. Med Care. 2007;45(5):448–455.

- , . Resident Work Hours, Hospitalist Programs, and Academic Medical Centers. The Hospitalist. Vol Jan/Feb: Society of Hospital Medicine; 2005: http://www.the‐hospitalist.org/details/article/257983/Resident_Work_Hours_Hospitalist_Programs_and_Academic_Medical_Centers.html#. Accessed on August 21, 2012.

- . Hospital stays for children, 2006. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project. Statistical brief 56. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2008. Available at: http://www.hcup‐us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb56.pdf. Accessed on August 21, 2012

- , , , et al. Implications of the California nurse staffing mandate for other states. Health Serv Res. 2010;45:904–921.