User login

Infectious disease pop quiz: Clinical challenge #8 for the ObGyn

For uncomplicated gonorrhea in a pregnant woman, what is the most appropriate treatment?

Continue to the answer...

The current recommendation from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for treatment of uncomplicated gonorrhea is a single 500-mg intramuscular dose of ceftriaxone. For the patient who is opposed to an intramuscular injection, an alternative treatment is cefixime 800 mg orally. With either of these regimens, if chlamydia infection cannot be excluded, the pregnant patient also should receive azithromycin 1,000 mg orally in a single dose. In a nonpregnant patient, doxycycline 100 mg orally twice daily for 7 days should be used to cover for concurrent chlamydia infection.

In a patient with an allergy to β-lactam antibiotics, an alternative regimen for treatment of uncomplicated gonorrhea is intramuscular gentamicin 240 mg plus a single 2,000-mg dose of oral azithromycin. (St Cyr S, Barbee L, Workowski KA, et al. Update to CDC’s treatment guidelines for gonococcal infection, 2020. MMWR Morbid Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:1911-1916.)

- Duff P. Maternal and perinatal infections: bacterial. In: Landon MB, Galan HL, Jauniaux ERM, et al. Gabbe’s Obstetrics: Normal and Problem Pregnancies. 8th ed. Elsevier; 2021:1124-1146.

- Duff P. Maternal and fetal infections. In: Resnik R, Lockwood CJ, Moore TJ, et al. Creasy & Resnik’s Maternal-Fetal Medicine: Principles and Practice. 8th ed. Elsevier; 2019:862-919.

For uncomplicated gonorrhea in a pregnant woman, what is the most appropriate treatment?

Continue to the answer...

The current recommendation from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for treatment of uncomplicated gonorrhea is a single 500-mg intramuscular dose of ceftriaxone. For the patient who is opposed to an intramuscular injection, an alternative treatment is cefixime 800 mg orally. With either of these regimens, if chlamydia infection cannot be excluded, the pregnant patient also should receive azithromycin 1,000 mg orally in a single dose. In a nonpregnant patient, doxycycline 100 mg orally twice daily for 7 days should be used to cover for concurrent chlamydia infection.

In a patient with an allergy to β-lactam antibiotics, an alternative regimen for treatment of uncomplicated gonorrhea is intramuscular gentamicin 240 mg plus a single 2,000-mg dose of oral azithromycin. (St Cyr S, Barbee L, Workowski KA, et al. Update to CDC’s treatment guidelines for gonococcal infection, 2020. MMWR Morbid Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:1911-1916.)

For uncomplicated gonorrhea in a pregnant woman, what is the most appropriate treatment?

Continue to the answer...

The current recommendation from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for treatment of uncomplicated gonorrhea is a single 500-mg intramuscular dose of ceftriaxone. For the patient who is opposed to an intramuscular injection, an alternative treatment is cefixime 800 mg orally. With either of these regimens, if chlamydia infection cannot be excluded, the pregnant patient also should receive azithromycin 1,000 mg orally in a single dose. In a nonpregnant patient, doxycycline 100 mg orally twice daily for 7 days should be used to cover for concurrent chlamydia infection.

In a patient with an allergy to β-lactam antibiotics, an alternative regimen for treatment of uncomplicated gonorrhea is intramuscular gentamicin 240 mg plus a single 2,000-mg dose of oral azithromycin. (St Cyr S, Barbee L, Workowski KA, et al. Update to CDC’s treatment guidelines for gonococcal infection, 2020. MMWR Morbid Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:1911-1916.)

- Duff P. Maternal and perinatal infections: bacterial. In: Landon MB, Galan HL, Jauniaux ERM, et al. Gabbe’s Obstetrics: Normal and Problem Pregnancies. 8th ed. Elsevier; 2021:1124-1146.

- Duff P. Maternal and fetal infections. In: Resnik R, Lockwood CJ, Moore TJ, et al. Creasy & Resnik’s Maternal-Fetal Medicine: Principles and Practice. 8th ed. Elsevier; 2019:862-919.

- Duff P. Maternal and perinatal infections: bacterial. In: Landon MB, Galan HL, Jauniaux ERM, et al. Gabbe’s Obstetrics: Normal and Problem Pregnancies. 8th ed. Elsevier; 2021:1124-1146.

- Duff P. Maternal and fetal infections. In: Resnik R, Lockwood CJ, Moore TJ, et al. Creasy & Resnik’s Maternal-Fetal Medicine: Principles and Practice. 8th ed. Elsevier; 2019:862-919.

Infectious disease pop quiz: Clinical challenge #7 for the ObGyn

What is the most appropriate treatment for trichomonas infection in pregnancy?

Continue to the answer...

Trichomonas infection should be treated with oral metronidazole 500 mg twice daily for 7 days. Metronidazole also can be given as a single oral 2-g dose. This treatment is not quite as effective as the multidose regimen, but it may be appropriate for patients who are not likely to be adherent with the longer course of treatment.

Resistance to metronidazole is rare; in such instances, oral tinidazole 2 g in a single dose may be effective.

- Duff P. Maternal and perinatal infections: bacterial. In: Landon MB, Galan HL, Jauniaux ERM, et al. Gabbe’s Obstetrics: Normal and Problem Pregnancies. 8th ed. Elsevier; 2021:1124-1146.

- Duff P. Maternal and fetal infections. In: Resnik R, Lockwood CJ, Moore TJ, et al. Creasy & Resnik’s Maternal-Fetal Medicine: Principles and Practice. 8th ed. Elsevier; 2019:862-919.

What is the most appropriate treatment for trichomonas infection in pregnancy?

Continue to the answer...

Trichomonas infection should be treated with oral metronidazole 500 mg twice daily for 7 days. Metronidazole also can be given as a single oral 2-g dose. This treatment is not quite as effective as the multidose regimen, but it may be appropriate for patients who are not likely to be adherent with the longer course of treatment.

Resistance to metronidazole is rare; in such instances, oral tinidazole 2 g in a single dose may be effective.

What is the most appropriate treatment for trichomonas infection in pregnancy?

Continue to the answer...

Trichomonas infection should be treated with oral metronidazole 500 mg twice daily for 7 days. Metronidazole also can be given as a single oral 2-g dose. This treatment is not quite as effective as the multidose regimen, but it may be appropriate for patients who are not likely to be adherent with the longer course of treatment.

Resistance to metronidazole is rare; in such instances, oral tinidazole 2 g in a single dose may be effective.

- Duff P. Maternal and perinatal infections: bacterial. In: Landon MB, Galan HL, Jauniaux ERM, et al. Gabbe’s Obstetrics: Normal and Problem Pregnancies. 8th ed. Elsevier; 2021:1124-1146.

- Duff P. Maternal and fetal infections. In: Resnik R, Lockwood CJ, Moore TJ, et al. Creasy & Resnik’s Maternal-Fetal Medicine: Principles and Practice. 8th ed. Elsevier; 2019:862-919.

- Duff P. Maternal and perinatal infections: bacterial. In: Landon MB, Galan HL, Jauniaux ERM, et al. Gabbe’s Obstetrics: Normal and Problem Pregnancies. 8th ed. Elsevier; 2021:1124-1146.

- Duff P. Maternal and fetal infections. In: Resnik R, Lockwood CJ, Moore TJ, et al. Creasy & Resnik’s Maternal-Fetal Medicine: Principles and Practice. 8th ed. Elsevier; 2019:862-919.

Infectious disease pop quiz: Clinical challenge #6 for the ObGyn

Which vaccines are contraindicated in pregnancy?

Continue to the answer...

Live virus vaccines should not be used in pregnancy because of the possibility of teratogenic effects. Live agents include the measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) vaccine; live influenza vaccine (FluMist); oral polio vaccine; BCG (bacille Calmette-Guerin) vaccine; yellow fever vaccine; and smallpox vaccine.

- Duff P. Maternal and perinatal infections: bacterial. In: Landon MB, Galan HL, Jauniaux ERM, et al. Gabbe’s Obstetrics: Normal and Problem Pregnancies. 8th ed. Elsevier; 2021:1124-1146.

- Duff P. Maternal and fetal infections. In: Resnik R, Lockwood CJ, Moore TJ, et al. Creasy & Resnik’s Maternal-Fetal Medicine: Principles and Practice. 8th ed. Elsevier; 2019:862-919.

Which vaccines are contraindicated in pregnancy?

Continue to the answer...

Live virus vaccines should not be used in pregnancy because of the possibility of teratogenic effects. Live agents include the measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) vaccine; live influenza vaccine (FluMist); oral polio vaccine; BCG (bacille Calmette-Guerin) vaccine; yellow fever vaccine; and smallpox vaccine.

Which vaccines are contraindicated in pregnancy?

Continue to the answer...

Live virus vaccines should not be used in pregnancy because of the possibility of teratogenic effects. Live agents include the measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) vaccine; live influenza vaccine (FluMist); oral polio vaccine; BCG (bacille Calmette-Guerin) vaccine; yellow fever vaccine; and smallpox vaccine.

- Duff P. Maternal and perinatal infections: bacterial. In: Landon MB, Galan HL, Jauniaux ERM, et al. Gabbe’s Obstetrics: Normal and Problem Pregnancies. 8th ed. Elsevier; 2021:1124-1146.

- Duff P. Maternal and fetal infections. In: Resnik R, Lockwood CJ, Moore TJ, et al. Creasy & Resnik’s Maternal-Fetal Medicine: Principles and Practice. 8th ed. Elsevier; 2019:862-919.

- Duff P. Maternal and perinatal infections: bacterial. In: Landon MB, Galan HL, Jauniaux ERM, et al. Gabbe’s Obstetrics: Normal and Problem Pregnancies. 8th ed. Elsevier; 2021:1124-1146.

- Duff P. Maternal and fetal infections. In: Resnik R, Lockwood CJ, Moore TJ, et al. Creasy & Resnik’s Maternal-Fetal Medicine: Principles and Practice. 8th ed. Elsevier; 2019:862-919.

Infectious disease pop quiz: Clinical challenges for the ObGyn

In this question-and-answer article (the second in a series), our objective is to reinforce for the clinician several practical points of management for common infectious diseases. The principal references for the answers to the questions are 2 textbook chapters written by Dr. Duff.1,2 Other pertinent references are included in the text.

9. For uncomplicated chlamydia infection in a pregnant woman, what is the most appropriate treatment?

Uncomplicated chlamydia infection in a pregnant woman should be treated with a single 1,000-mg oral dose of azithromycin. An acceptable alternative is amoxicillin

500 mg orally 3 times daily for 7 days.

In a nonpregnant patient, doxycycline 100 mg orally twice daily for 7 days is also an appropriate alternative. However, doxycycline is relatively expensive and may not be well tolerated because of gastrointestinal adverse effects. (Workowski KA, Bolan GA. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2015. MMWR Morbid Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64[RR3]:1-137.)

10. What are the characteristic mucocutaneous lesions of primary, secondary, and tertiary syphilis?

The characteristic mucosal lesion of primary syphilis is the painless chancre. The usual mucocutaneous manifestations of secondary syphilis are maculopapular lesions (red or violet in color) on the palms and soles, mucous patches on the oral membranes, and condyloma lata on the genitalia. The classic mucocutaneous lesion of tertiary syphilis is the gumma.

Other serious manifestations of advanced syphilis include central nervous system abnormalities, such as tabes dorsalis, the Argyll Robertson pupil, and dementia, and cardiac abnormalities, such as aortitis, which can lead to a dissecting aneurysm of the aortic root. (Workowski KA, Bolan GA. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2015. MMWR Morbid Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64[RR3]:1-137.)

11. In a pregnant woman with a history of recurrent herpes simplex virus infection, what is the best way to prevent an outbreak of lesions near term?

Obstetric patients with a history of recurrent herpes simplex infection should be treated with acyclovir 400 mg orally 3 times daily from 36 weeks until delivery. This

regimen significantly reduces the likelihood of a recurrent outbreak near the time of delivery, which if it occurred, would necessitate a cesarean delivery. In patients at increased risk for preterm delivery, the prophylactic regimen should be started earlier.

Valacyclovir, 500 mg orally twice daily, is an acceptable alternative but is significantly more expensive.

Continue to: 12. What are the best office-based tests for the diagnosis of bacterial vaginosis?...

12. What are the best office-based tests for the diagnosis of bacterial vaginosis?

In patients with bacterial vaginosis, the vaginal pH typically is elevated in the range of 4.5. When a drop of potassium hydroxide solution is added to the vaginal secretions, a characteristic fishlike (amine) odor is liberated (positive “whiff test”). With saline microscopy, the key findings are a relative absence of lactobacilli in the background, an abundance of small cocci and bacilli, and the presence of clue cells, which are epithelial cells studded with bacteria along their

outer margin.

13. For a moderately ill pregnant woman, what is the most appropriate antibiotic combination for inpatient treatment of community-acquired pneumonia?

This patient should be treated with intravenous ceftriaxone (2 g every 24 hours) plus oral or intravenous azithromycin. The appropriate oral dose of azithromycin is 500 mg on day 1, then 250 mg daily for 4 doses. The appropriate intravenous dose of azithromycin is 500 mg every 24 hours. The goal is to provide appropriate coverage for the most likely pathogens: Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, Moraxella catarrhalis, and mycoplasmas. (Antibacterial drugs for community-acquired pneumonia. Med Lett Drugs Ther. 2021:63:10-14. Postma DF, van Werkoven CH, van Eldin LJ, et al; CAP-START Study Group. Antibiotic treatment strategies for community acquired pneumonia in adults. N Engl J Med. 2015;372: 1312-1323.)

14. What tests are best for the diagnosis of COVID-19 infection?

The 2 key diagnostic tests for COVID-19 infection are detecting antigen in nasopharyngeal washings or saliva by nucleic acid amplification tests and identifying groundglass opacities on computed tomography imaging of the chest. (Berlin DA, Gulick RM, Martinez FJ. Severe Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:2451-2460.)

15. What is the most appropriate treatment for a pregnant woman who is moderately to severely ill with COVID-19 infection?

Moderately to severely ill pregnant women with COVID-19 infection should be hospitalized and treated with supplementary oxygen, remdesivir, and dexamethasone. Other possible therapies include inhaled nitric oxide, baricitinib (a Janus kinase inhibitor), and tocilizumab (an anti-interleukin 6 receptor antibody). (RECOVERY Collaborative Group; Horby P, Lim WS, Emberson JR, et al. Dexamethasone in hospitalized patients with COVID-19. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:693704. Kalil AC, Patterson TF, Mehta AK, et al; ACTT-2 Study Group. Baricitinib plus remdesivir for hospitalized adults with COVID-19. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:795-807. Berlin DA, Gulick RM, Martinez FJ, et al. Severe COVID19. N Engl J Med. 2020;383;2451-2460.)

16. What is the best test for the diagnosis of acute hepatitis A infection?

The single best test for the diagnosis of acute hepatitis A infection is detection of immunoglobulin M (IgM)–specific antibody to the virus.

17. What are the best tests for identification of a patient with chronic hepatitis B infection?

Patients with chronic hepatitis B infection typically test positive for the hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) and for IgG antibody to the hepatitis B core antigen (HBcAg). In addition, they also may test positive for the hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg), and their viral load can be quantified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) when significant antigenemia is present. The presence of the e antigen indicates a high rate of viral replication and a corresponding high rate of infectivity.

18. What antenatal treatment is indicated in a pregnant woman at 28 weeks’ gestation who has a hepatitis B viral load of 2 million copies/mL?

This patient has a markedly elevated viral load and is at significantly increased risk of transmitting hepatitis B infection to her neonate even if the infant receives hepatitis B immune globulin immediately after birth and quickly begins the hepatitis B vaccine series. Daily antenatal treatment with tenofovir (300 mg daily) from 28 weeks until delivery will significantly reduce the risk of perinatal transmission.

19. Should a postpartum patient with chronic hepatitis C infection be discouraged from breastfeeding her infant?

Hepatitis C is not a contraindication to breastfeeding. Although the virus has been identified in breast milk, the risk of transmission to the infant is exceedingly low.

20. What are the principal microorganisms that cause puerperal mastitis?

Staphylococci and Streptococcus viridans are the 2 dominant microorganisms that cause puerperal mastitis. For the initial treatment of mastitis, the drug of choice is dicloxacillin sodium (500 mg orally every 6 to 8 hours for 7 to 10 days). If the patient has a mild allergy to penicillin, cephalexin (500 mg orally every 6 to 8 hours for 7 to 10 days) is an appropriate alternative. If the allergy to penicillin is severe or if methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) infection is suspected, either clindamycin (300 mg orally twice daily for 7 to 10 days) or trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole double strength orally twice daily for 7 to 10 days should be used. ●

- Duff P. Maternal and perinatal infections: bacterial. In: Landon MB, Galan HL, Jauniaux ERM, et al. Gabbe’s Obstetrics: Normal and Problem Pregnancies. 8th ed. Elsevier; 2021:1124-1146.

- Duff P. Maternal and fetal infections. In: Resnik R, Lockwood CJ, Moore TJ, et al. Creasy & Resnik’s Maternal-Fetal Medicine: Principles and Practice. 8th ed. Elsevier; 2019:862-919.

In this question-and-answer article (the second in a series), our objective is to reinforce for the clinician several practical points of management for common infectious diseases. The principal references for the answers to the questions are 2 textbook chapters written by Dr. Duff.1,2 Other pertinent references are included in the text.

9. For uncomplicated chlamydia infection in a pregnant woman, what is the most appropriate treatment?

Uncomplicated chlamydia infection in a pregnant woman should be treated with a single 1,000-mg oral dose of azithromycin. An acceptable alternative is amoxicillin

500 mg orally 3 times daily for 7 days.

In a nonpregnant patient, doxycycline 100 mg orally twice daily for 7 days is also an appropriate alternative. However, doxycycline is relatively expensive and may not be well tolerated because of gastrointestinal adverse effects. (Workowski KA, Bolan GA. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2015. MMWR Morbid Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64[RR3]:1-137.)

10. What are the characteristic mucocutaneous lesions of primary, secondary, and tertiary syphilis?

The characteristic mucosal lesion of primary syphilis is the painless chancre. The usual mucocutaneous manifestations of secondary syphilis are maculopapular lesions (red or violet in color) on the palms and soles, mucous patches on the oral membranes, and condyloma lata on the genitalia. The classic mucocutaneous lesion of tertiary syphilis is the gumma.

Other serious manifestations of advanced syphilis include central nervous system abnormalities, such as tabes dorsalis, the Argyll Robertson pupil, and dementia, and cardiac abnormalities, such as aortitis, which can lead to a dissecting aneurysm of the aortic root. (Workowski KA, Bolan GA. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2015. MMWR Morbid Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64[RR3]:1-137.)

11. In a pregnant woman with a history of recurrent herpes simplex virus infection, what is the best way to prevent an outbreak of lesions near term?

Obstetric patients with a history of recurrent herpes simplex infection should be treated with acyclovir 400 mg orally 3 times daily from 36 weeks until delivery. This

regimen significantly reduces the likelihood of a recurrent outbreak near the time of delivery, which if it occurred, would necessitate a cesarean delivery. In patients at increased risk for preterm delivery, the prophylactic regimen should be started earlier.

Valacyclovir, 500 mg orally twice daily, is an acceptable alternative but is significantly more expensive.

Continue to: 12. What are the best office-based tests for the diagnosis of bacterial vaginosis?...

12. What are the best office-based tests for the diagnosis of bacterial vaginosis?

In patients with bacterial vaginosis, the vaginal pH typically is elevated in the range of 4.5. When a drop of potassium hydroxide solution is added to the vaginal secretions, a characteristic fishlike (amine) odor is liberated (positive “whiff test”). With saline microscopy, the key findings are a relative absence of lactobacilli in the background, an abundance of small cocci and bacilli, and the presence of clue cells, which are epithelial cells studded with bacteria along their

outer margin.

13. For a moderately ill pregnant woman, what is the most appropriate antibiotic combination for inpatient treatment of community-acquired pneumonia?

This patient should be treated with intravenous ceftriaxone (2 g every 24 hours) plus oral or intravenous azithromycin. The appropriate oral dose of azithromycin is 500 mg on day 1, then 250 mg daily for 4 doses. The appropriate intravenous dose of azithromycin is 500 mg every 24 hours. The goal is to provide appropriate coverage for the most likely pathogens: Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, Moraxella catarrhalis, and mycoplasmas. (Antibacterial drugs for community-acquired pneumonia. Med Lett Drugs Ther. 2021:63:10-14. Postma DF, van Werkoven CH, van Eldin LJ, et al; CAP-START Study Group. Antibiotic treatment strategies for community acquired pneumonia in adults. N Engl J Med. 2015;372: 1312-1323.)

14. What tests are best for the diagnosis of COVID-19 infection?

The 2 key diagnostic tests for COVID-19 infection are detecting antigen in nasopharyngeal washings or saliva by nucleic acid amplification tests and identifying groundglass opacities on computed tomography imaging of the chest. (Berlin DA, Gulick RM, Martinez FJ. Severe Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:2451-2460.)

15. What is the most appropriate treatment for a pregnant woman who is moderately to severely ill with COVID-19 infection?

Moderately to severely ill pregnant women with COVID-19 infection should be hospitalized and treated with supplementary oxygen, remdesivir, and dexamethasone. Other possible therapies include inhaled nitric oxide, baricitinib (a Janus kinase inhibitor), and tocilizumab (an anti-interleukin 6 receptor antibody). (RECOVERY Collaborative Group; Horby P, Lim WS, Emberson JR, et al. Dexamethasone in hospitalized patients with COVID-19. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:693704. Kalil AC, Patterson TF, Mehta AK, et al; ACTT-2 Study Group. Baricitinib plus remdesivir for hospitalized adults with COVID-19. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:795-807. Berlin DA, Gulick RM, Martinez FJ, et al. Severe COVID19. N Engl J Med. 2020;383;2451-2460.)

16. What is the best test for the diagnosis of acute hepatitis A infection?

The single best test for the diagnosis of acute hepatitis A infection is detection of immunoglobulin M (IgM)–specific antibody to the virus.

17. What are the best tests for identification of a patient with chronic hepatitis B infection?

Patients with chronic hepatitis B infection typically test positive for the hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) and for IgG antibody to the hepatitis B core antigen (HBcAg). In addition, they also may test positive for the hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg), and their viral load can be quantified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) when significant antigenemia is present. The presence of the e antigen indicates a high rate of viral replication and a corresponding high rate of infectivity.

18. What antenatal treatment is indicated in a pregnant woman at 28 weeks’ gestation who has a hepatitis B viral load of 2 million copies/mL?

This patient has a markedly elevated viral load and is at significantly increased risk of transmitting hepatitis B infection to her neonate even if the infant receives hepatitis B immune globulin immediately after birth and quickly begins the hepatitis B vaccine series. Daily antenatal treatment with tenofovir (300 mg daily) from 28 weeks until delivery will significantly reduce the risk of perinatal transmission.

19. Should a postpartum patient with chronic hepatitis C infection be discouraged from breastfeeding her infant?

Hepatitis C is not a contraindication to breastfeeding. Although the virus has been identified in breast milk, the risk of transmission to the infant is exceedingly low.

20. What are the principal microorganisms that cause puerperal mastitis?

Staphylococci and Streptococcus viridans are the 2 dominant microorganisms that cause puerperal mastitis. For the initial treatment of mastitis, the drug of choice is dicloxacillin sodium (500 mg orally every 6 to 8 hours for 7 to 10 days). If the patient has a mild allergy to penicillin, cephalexin (500 mg orally every 6 to 8 hours for 7 to 10 days) is an appropriate alternative. If the allergy to penicillin is severe or if methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) infection is suspected, either clindamycin (300 mg orally twice daily for 7 to 10 days) or trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole double strength orally twice daily for 7 to 10 days should be used. ●

In this question-and-answer article (the second in a series), our objective is to reinforce for the clinician several practical points of management for common infectious diseases. The principal references for the answers to the questions are 2 textbook chapters written by Dr. Duff.1,2 Other pertinent references are included in the text.

9. For uncomplicated chlamydia infection in a pregnant woman, what is the most appropriate treatment?

Uncomplicated chlamydia infection in a pregnant woman should be treated with a single 1,000-mg oral dose of azithromycin. An acceptable alternative is amoxicillin

500 mg orally 3 times daily for 7 days.

In a nonpregnant patient, doxycycline 100 mg orally twice daily for 7 days is also an appropriate alternative. However, doxycycline is relatively expensive and may not be well tolerated because of gastrointestinal adverse effects. (Workowski KA, Bolan GA. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2015. MMWR Morbid Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64[RR3]:1-137.)

10. What are the characteristic mucocutaneous lesions of primary, secondary, and tertiary syphilis?

The characteristic mucosal lesion of primary syphilis is the painless chancre. The usual mucocutaneous manifestations of secondary syphilis are maculopapular lesions (red or violet in color) on the palms and soles, mucous patches on the oral membranes, and condyloma lata on the genitalia. The classic mucocutaneous lesion of tertiary syphilis is the gumma.

Other serious manifestations of advanced syphilis include central nervous system abnormalities, such as tabes dorsalis, the Argyll Robertson pupil, and dementia, and cardiac abnormalities, such as aortitis, which can lead to a dissecting aneurysm of the aortic root. (Workowski KA, Bolan GA. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2015. MMWR Morbid Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64[RR3]:1-137.)

11. In a pregnant woman with a history of recurrent herpes simplex virus infection, what is the best way to prevent an outbreak of lesions near term?

Obstetric patients with a history of recurrent herpes simplex infection should be treated with acyclovir 400 mg orally 3 times daily from 36 weeks until delivery. This

regimen significantly reduces the likelihood of a recurrent outbreak near the time of delivery, which if it occurred, would necessitate a cesarean delivery. In patients at increased risk for preterm delivery, the prophylactic regimen should be started earlier.

Valacyclovir, 500 mg orally twice daily, is an acceptable alternative but is significantly more expensive.

Continue to: 12. What are the best office-based tests for the diagnosis of bacterial vaginosis?...

12. What are the best office-based tests for the diagnosis of bacterial vaginosis?

In patients with bacterial vaginosis, the vaginal pH typically is elevated in the range of 4.5. When a drop of potassium hydroxide solution is added to the vaginal secretions, a characteristic fishlike (amine) odor is liberated (positive “whiff test”). With saline microscopy, the key findings are a relative absence of lactobacilli in the background, an abundance of small cocci and bacilli, and the presence of clue cells, which are epithelial cells studded with bacteria along their

outer margin.

13. For a moderately ill pregnant woman, what is the most appropriate antibiotic combination for inpatient treatment of community-acquired pneumonia?

This patient should be treated with intravenous ceftriaxone (2 g every 24 hours) plus oral or intravenous azithromycin. The appropriate oral dose of azithromycin is 500 mg on day 1, then 250 mg daily for 4 doses. The appropriate intravenous dose of azithromycin is 500 mg every 24 hours. The goal is to provide appropriate coverage for the most likely pathogens: Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, Moraxella catarrhalis, and mycoplasmas. (Antibacterial drugs for community-acquired pneumonia. Med Lett Drugs Ther. 2021:63:10-14. Postma DF, van Werkoven CH, van Eldin LJ, et al; CAP-START Study Group. Antibiotic treatment strategies for community acquired pneumonia in adults. N Engl J Med. 2015;372: 1312-1323.)

14. What tests are best for the diagnosis of COVID-19 infection?

The 2 key diagnostic tests for COVID-19 infection are detecting antigen in nasopharyngeal washings or saliva by nucleic acid amplification tests and identifying groundglass opacities on computed tomography imaging of the chest. (Berlin DA, Gulick RM, Martinez FJ. Severe Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:2451-2460.)

15. What is the most appropriate treatment for a pregnant woman who is moderately to severely ill with COVID-19 infection?

Moderately to severely ill pregnant women with COVID-19 infection should be hospitalized and treated with supplementary oxygen, remdesivir, and dexamethasone. Other possible therapies include inhaled nitric oxide, baricitinib (a Janus kinase inhibitor), and tocilizumab (an anti-interleukin 6 receptor antibody). (RECOVERY Collaborative Group; Horby P, Lim WS, Emberson JR, et al. Dexamethasone in hospitalized patients with COVID-19. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:693704. Kalil AC, Patterson TF, Mehta AK, et al; ACTT-2 Study Group. Baricitinib plus remdesivir for hospitalized adults with COVID-19. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:795-807. Berlin DA, Gulick RM, Martinez FJ, et al. Severe COVID19. N Engl J Med. 2020;383;2451-2460.)

16. What is the best test for the diagnosis of acute hepatitis A infection?

The single best test for the diagnosis of acute hepatitis A infection is detection of immunoglobulin M (IgM)–specific antibody to the virus.

17. What are the best tests for identification of a patient with chronic hepatitis B infection?

Patients with chronic hepatitis B infection typically test positive for the hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) and for IgG antibody to the hepatitis B core antigen (HBcAg). In addition, they also may test positive for the hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg), and their viral load can be quantified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) when significant antigenemia is present. The presence of the e antigen indicates a high rate of viral replication and a corresponding high rate of infectivity.

18. What antenatal treatment is indicated in a pregnant woman at 28 weeks’ gestation who has a hepatitis B viral load of 2 million copies/mL?

This patient has a markedly elevated viral load and is at significantly increased risk of transmitting hepatitis B infection to her neonate even if the infant receives hepatitis B immune globulin immediately after birth and quickly begins the hepatitis B vaccine series. Daily antenatal treatment with tenofovir (300 mg daily) from 28 weeks until delivery will significantly reduce the risk of perinatal transmission.

19. Should a postpartum patient with chronic hepatitis C infection be discouraged from breastfeeding her infant?

Hepatitis C is not a contraindication to breastfeeding. Although the virus has been identified in breast milk, the risk of transmission to the infant is exceedingly low.

20. What are the principal microorganisms that cause puerperal mastitis?

Staphylococci and Streptococcus viridans are the 2 dominant microorganisms that cause puerperal mastitis. For the initial treatment of mastitis, the drug of choice is dicloxacillin sodium (500 mg orally every 6 to 8 hours for 7 to 10 days). If the patient has a mild allergy to penicillin, cephalexin (500 mg orally every 6 to 8 hours for 7 to 10 days) is an appropriate alternative. If the allergy to penicillin is severe or if methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) infection is suspected, either clindamycin (300 mg orally twice daily for 7 to 10 days) or trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole double strength orally twice daily for 7 to 10 days should be used. ●

- Duff P. Maternal and perinatal infections: bacterial. In: Landon MB, Galan HL, Jauniaux ERM, et al. Gabbe’s Obstetrics: Normal and Problem Pregnancies. 8th ed. Elsevier; 2021:1124-1146.

- Duff P. Maternal and fetal infections. In: Resnik R, Lockwood CJ, Moore TJ, et al. Creasy & Resnik’s Maternal-Fetal Medicine: Principles and Practice. 8th ed. Elsevier; 2019:862-919.

- Duff P. Maternal and perinatal infections: bacterial. In: Landon MB, Galan HL, Jauniaux ERM, et al. Gabbe’s Obstetrics: Normal and Problem Pregnancies. 8th ed. Elsevier; 2021:1124-1146.

- Duff P. Maternal and fetal infections. In: Resnik R, Lockwood CJ, Moore TJ, et al. Creasy & Resnik’s Maternal-Fetal Medicine: Principles and Practice. 8th ed. Elsevier; 2019:862-919.

Infectious disease pop quiz: Clinical challenge #5 for the ObGyn

What are the major manifestations of congenital rubella syndrome?

Continue to the answer...

Rubella is one of the most highly teratogenic of all the viral infections, particularly when maternal infection occurs in the first trimester. Manifestations of congenital rubella include hearing deficits, cataracts, glaucoma, microcephaly, mental retardation, cardiac malformations such as patent ductus arteriosus and pulmonic stenosis, and growth restriction.

- Duff P. Maternal and perinatal infections: bacterial. In: Landon MB, Galan HL, Jauniaux ERM, et al. Gabbe’s Obstetrics: Normal and Problem Pregnancies. 8th ed. Elsevier; 2021:1124-1146.

- Duff P. Maternal and fetal infections. In: Resnik R, Lockwood CJ, Moore TJ, et al. Creasy & Resnik’s Maternal-Fetal Medicine: Principles and Practice. 8th ed. Elsevier; 2019:862-919.

What are the major manifestations of congenital rubella syndrome?

Continue to the answer...

Rubella is one of the most highly teratogenic of all the viral infections, particularly when maternal infection occurs in the first trimester. Manifestations of congenital rubella include hearing deficits, cataracts, glaucoma, microcephaly, mental retardation, cardiac malformations such as patent ductus arteriosus and pulmonic stenosis, and growth restriction.

What are the major manifestations of congenital rubella syndrome?

Continue to the answer...

Rubella is one of the most highly teratogenic of all the viral infections, particularly when maternal infection occurs in the first trimester. Manifestations of congenital rubella include hearing deficits, cataracts, glaucoma, microcephaly, mental retardation, cardiac malformations such as patent ductus arteriosus and pulmonic stenosis, and growth restriction.

- Duff P. Maternal and perinatal infections: bacterial. In: Landon MB, Galan HL, Jauniaux ERM, et al. Gabbe’s Obstetrics: Normal and Problem Pregnancies. 8th ed. Elsevier; 2021:1124-1146.

- Duff P. Maternal and fetal infections. In: Resnik R, Lockwood CJ, Moore TJ, et al. Creasy & Resnik’s Maternal-Fetal Medicine: Principles and Practice. 8th ed. Elsevier; 2019:862-919.

- Duff P. Maternal and perinatal infections: bacterial. In: Landon MB, Galan HL, Jauniaux ERM, et al. Gabbe’s Obstetrics: Normal and Problem Pregnancies. 8th ed. Elsevier; 2021:1124-1146.

- Duff P. Maternal and fetal infections. In: Resnik R, Lockwood CJ, Moore TJ, et al. Creasy & Resnik’s Maternal-Fetal Medicine: Principles and Practice. 8th ed. Elsevier; 2019:862-919.

Fever following cesarean delivery: What are your steps for management?

CASE Woman who has undergone recent cesarean delivery

A 23-year-old woman had a primary cesarean delivery 72 hours ago due to an arrest of dilation at 6 cm. She was in labor for 22 hours, and her membranes were ruptured for 18 hours. She had 10 internal vaginal examinations, and the duration of internal fetal monitoring was 12 hours; 24 hours after delivery, she developed a fever of 39°C, in association with lower abdominal pain and tenderness. She was presumptively treated for endometritis with cefepime; 48 hours after the initiation of antibiotics, she remains febrile and symptomatic.

- What are the most likely causes of her persistent fever?

- What should be the next steps in her evaluation?

Cesarean delivery background

Cesarean delivery is now the most common major operation performed in US hospitals. Cesarean delivery rates hover between 25% and 30% in most medical centers in the United States.1 The most common postoperative complication of cesarean delivery is infection. Infection typically takes 1 of 3 forms: endometritis (organ space infection), wound infection (surgical site infection), and urinary tract infection (UTI).1 This article will review the initial differential diagnosis, evaluation, and management of the patient with a postoperative fever and also will describe the appropriate assessment and treatment of the patient who has a persistent postoperative fever despite therapy. The article will also highlight key interventions that help to prevent postoperative infections.

Initial evaluation of the febrile patient

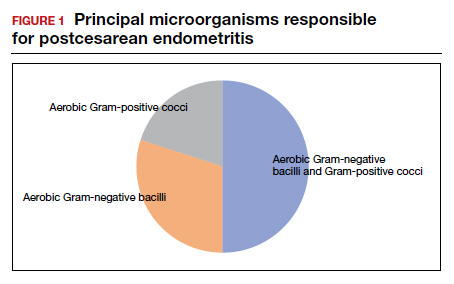

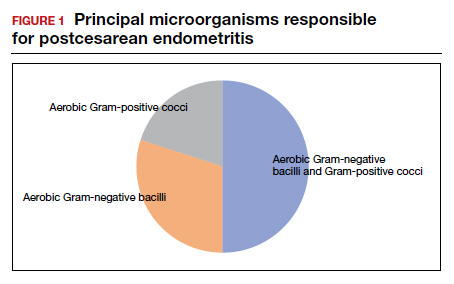

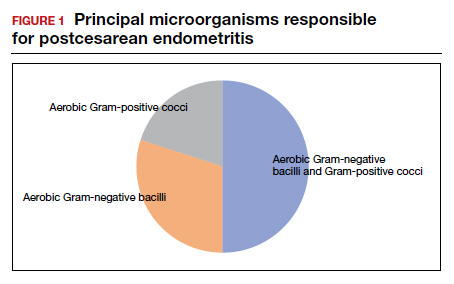

In the first 24 to 48 hours after cesarean delivery, the most common cause of fever is endometritis (organ space infection). This condition is a polymicrobial, mixed aerobic-anaerobic infection (FIGURE). The principal pathogens include anaerobic gram-positive cocci (

The major risk factors for postcesarean endometritis are extended duration of labor and ruptured membranes, multiple internal vaginal examinations, invasive fetal monitoring, and pre-existing colonization with group B Streptococcus and/or the organisms that cause bacterial vaginosis. Affected patients typically have a fever in the range of 38 to 39°C, tachycardia, mild tachypnea, lower abdominal pain and tenderness, and purulent lochia in some individuals.1

Differential for postoperative fever

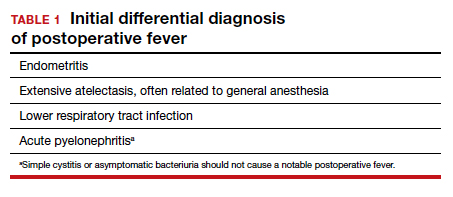

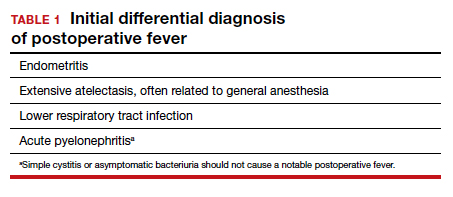

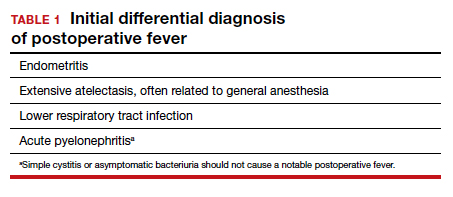

The initial differential diagnosis of postoperative fever is relatively limited (TABLE 1). In addition to endometritis, it includes extensive atelectasis, perhaps resulting from general anesthesia; lower respiratory tract infection, either viral influenza or bacterial pneumonia; and acute pyelonephritis. A simple infection of the bladder (cystitis or asymptomatic bacteriuria) should not cause a substantial temperature elevation and systemic symptoms.1

Differentiation between these entities usually is possible based on physical examination and a few laboratory tests. The peripheral white blood cell count usually is elevated, and a left shift may be evident. If a respiratory tract infection is suspected, chest radiography is indicated. A urine culture should be obtained if acute pyelonephritis strongly is considered. Lower genital tract cultures are rarely of value, and uncontaminated upper tract cultures are difficult to obtain. I do not believe that blood cultures should be performed as a matter of routine. They are expensive, and the results are often not available until after the patient has cleared her infection and left the hospital. However, I would obtain blood cultures in patients who meet one of these criteria1,2:

- They are immunocompromised (eg, HIV infection).

- They have a cardiac or vascular prosthesis and, thus, are at increased risk of complications related to bacteremia.

- They seem critically ill at the onset of evaluation.

- They fail to respond appropriately to initial therapy.

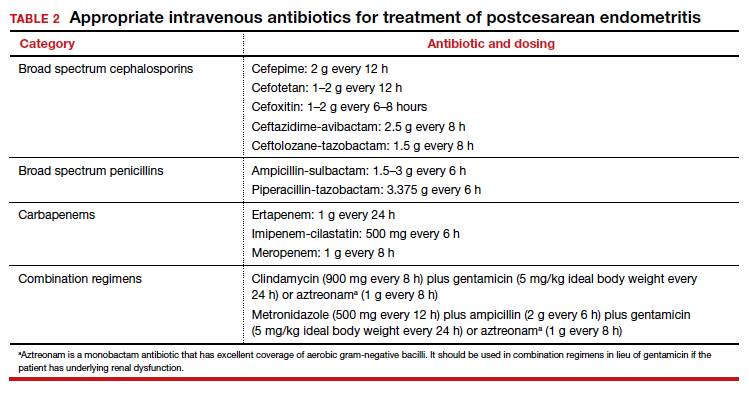

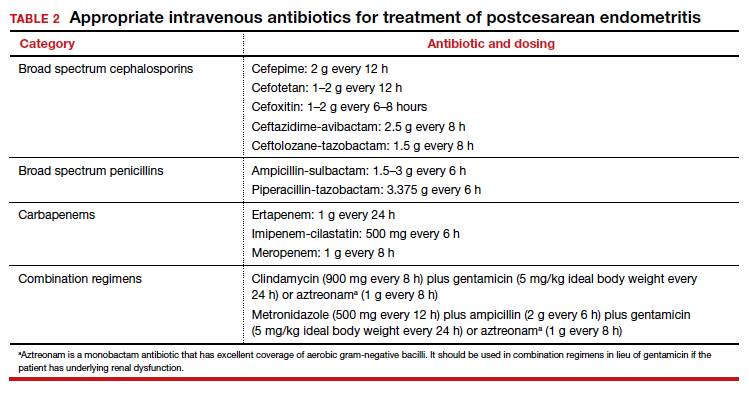

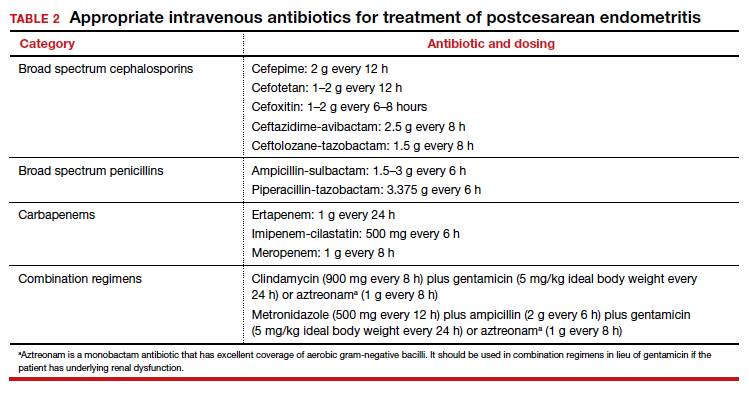

The cornerstone of therapy is broad spectrum antibiotics that target the multiple organisms responsible for endometritis.3 There are several single agents and several combination antibiotic regimens that provide excellent coverage against the usual pelvic pathogens (TABLE 2). I personally favor the generic combination regimen (clindamycin plus gentamicin) because it is relatively inexpensive and has been very well validated in multiple studies. In patients who have underlying renal dysfunction, aztreonam can be substituted for gentamicin.

Approximately 90% of patients will show clear evidence of clinical improvement (ie, decrease in temperature and resolution of abdominopelvic pain) within 48 hours of starting antibiotics. Patients should then continue therapy until they have been afebrile and asymptomatic for approximately 24 hours. At that point, antibiotics should be discontinued, and the patient can be discharged. With rare exceptions, there is no indication for administration of oral antibiotics on an outpatient basis.1,4

Continue to: Persistent postoperative fever...

Persistent postoperative fever

Resistant microorganism

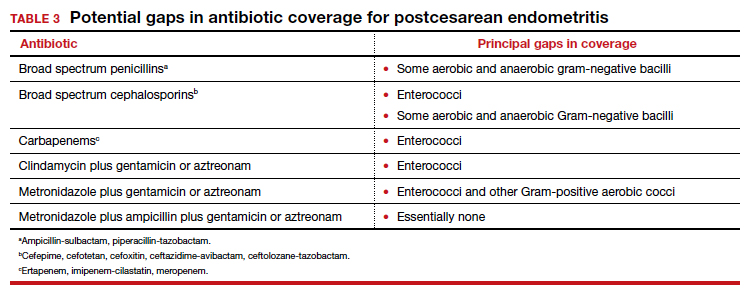

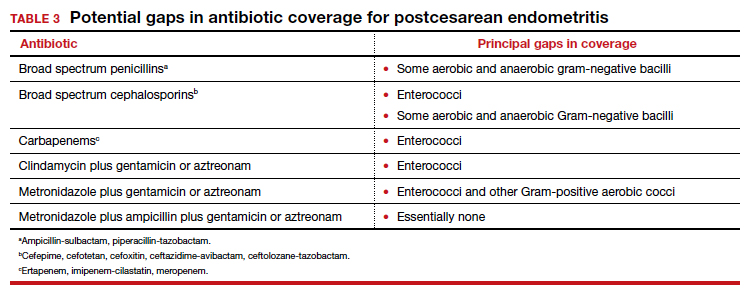

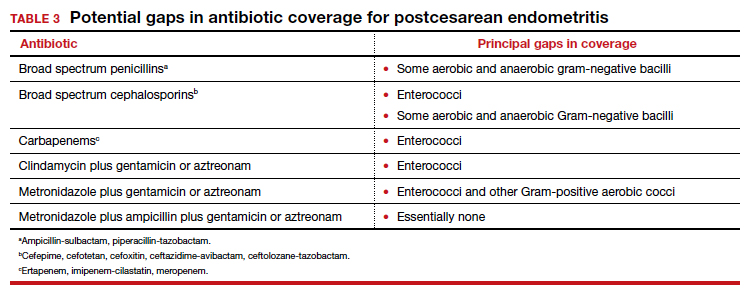

The most common cause of a persistent fever after initiating antibiotic therapy is a resistant microorganism. There are potential gaps in coverage for the antibiotic regimens commonly used to treat postcesarean endometritis (TABLE 3).1,4 Assuming there is no other obvious cause for treatment failure, I recommend that therapy be changed to the triple combination of metronidazole plus ampicillin plus gentamicin (or aztreonam). The first drug provides superb coverage against anaerobes; the second covers enterococci. Gentamicin or aztreonam cover virtually all aerobic Gram-negative bacilli likely to cause postcesarean infection. I prefer metronidazole rather than clindamycin in this regimen because, unlike clindamycin, it is less likely to trigger diarrhea when used in combination with ampicillin. The 3-drug regimen should be continued until the patient has been afebrile and asymptomatic for approximately 24 hours.1,3,4

Wound infection

The second most common reason for a poor response to initial antibiotic therapy is a wound (surgical site) infection. Wound infections are caused by many of the same pelvic pathogens responsible for endometritis combined with skin flora, notably Streptococcus and Staphylococcus species, including methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA).1,4

Wound infections typically take one of two forms. The first is an actual incisional abscess. The patient is febrile; the margins of the wound are warm, indurated, erythematous, and tender; and purulent material drains from the incision. In this situation, the wound should be opened widely to drain the purulent collection. The fascia should then be probed to be certain that dehiscence has not occurred. In addition, intravenous vancomycin (1 g every 12 h) should be included in the antibiotic regimen to ensure adequate coverage of hospital-acquired MRSA.1,4

The second common presentation of a wound infection is cellulitis. The patient is febrile, and there is a spreading area of erythema, warmth, and exquisite tenderness extending from the edges of the incision; however, no purulent drainage is apparent. In this second scenario, the wound should not be opened, but intravenous vancomycin should be added to the treatment regimen.1,3,4

A third and very rare form of wound infection is necrotizing fasciitis. In affected patients, the margins of the wound are darkened and necrotic rather than erythematous and indurated. Two other key physical findings are crepitance and loss of sensation along the margins of the wound. Necrotizing fasciitis is truly a life-threatening emergency and requires immediate and extensive debridement of the devitalized tissue, combined with broad spectrum therapy with antibiotics that provide excellent coverage against anaerobes, aerobic streptococci (particularly group A streptococci), and staphylococci. The requirement for debridement may be so extensive that a skin graft subsequently is necessary to close the defect.1,4

Continue to: Unusual causes of persistent postoperative fever...

Unusual causes of persistent postoperative fever

If a resistant microorganism and wound infection can be excluded, the clinician then must begin a diligent search for “zebras” (ie, uncommon but potentially serious causes of persistent fever).1,4 One possible cause is a pelvic abscess. These purulent collections typically form in the retrovesicle space as a result of infection of a hematoma that formed between the posterior bladder wall and the lower uterine segment, in the leaves of the broad ligament, or in the posterior cul-de-sac. The abscess may or may not be palpable. The patient’s peripheral white blood cell count usually is elevated, with a preponderance of neutrophils. The best imaging test for an abscess is a computed tomography (CT) scan. Abscesses require drainage, which usually can be accomplished by insertion of a percutaneous drain under ultrasonographic or CT guidance.

A second unusual cause of persistent fever is septic pelvic vein thrombophlebitis. The infected venous emboli usually are present in the ovarian veins, with the right side predominant. The patient’s peripheral white blood cell count usually is elevated, and the infected clots are best imaged by CT scan with contrast or magnetic resonance angiography. The appropriate treatment is continuation of broad-spectrum antibiotics and administration of therapeutic doses of parenteral anticoagulants such as enoxaparin or unfractionated heparin.

A third explanation for persistent fever is retained products of conception. This diagnosis is best made by ultrasonography. The placental fragments should be removed by sharp curettage.

A fourth consideration when evaluating the patient with persistent fever is an allergic drug reaction. In most instances, the increase in the patient’s temperature will correspond with administration of the offending antibiotic(s). Affected patients typically have an increased number of eosinophils in their peripheral white blood cell count. The appropriate management of drug fever is discontinuation of antibiotics.

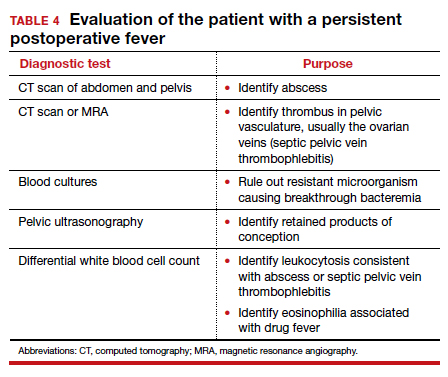

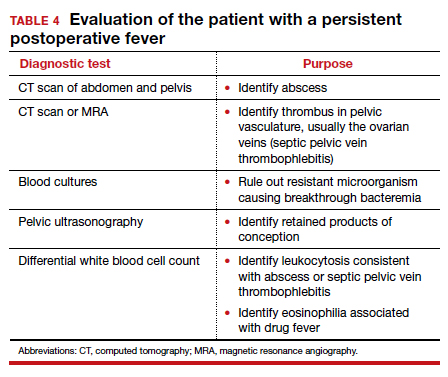

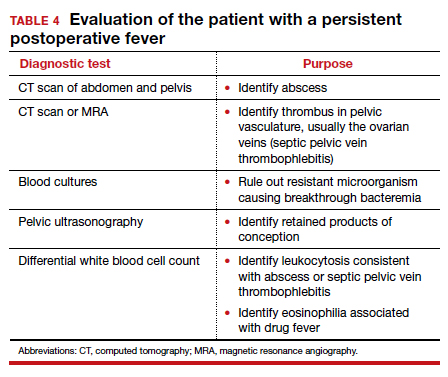

A final and distinctly unusual consideration is recrudescence of a connective tissue disorder such as systemic lupus erythematosus. The best test to confirm this diagnosis is the serum complement assay, which will demonstrate a decreased serum concentration of complement, reflecting consumption of this serum protein during the inflammatory process. The correct management for this condition is administration of a short course of systemic glucocorticoids. TABLE 4 summarizes a simple, systematic plan for evaluation of the patient with a persistent postoperative fever.

Preventive measures

We all remember the simple but profound statement by Benjamin Franklin, “An ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure.” That folksy adage rings true with respect to postoperative infection because this complication extends hospital stay, increases hospital expense, and causes considerable discomfort and inconvenience for the patient. Therefore, we would do well to prevent as many instances of postoperative infection as possible.

Endometritis

On the basis of well-designed, prospective, randomized trials (Level 1 evidence), 3 interventions have proven effective in reducing the frequency of postcesarean endometritis. The first is irrigation of the vaginal canal preoperatively with an iodophor solution.5,6 The second is preoperative administration of systemic antibiotics.7-9 The combination of cefazolin (2 g IV within 30 minutes of incision) plus azithromycin (500 mg IV over 1 hour prior to incision) is superior to cefazolin alone.10,11 The third important preventive measure is removing the placenta by traction on the umbilical cord rather than by manual extraction.12,13

Wound infection

Several interventions are of proven effectiveness in reducing the frequency of postcesarean wound (surgical site) infection. The first is removal of hair at the incision site by clipping rather than by shaving (Level 2 evidence).14 The second is cleansing of the skin with chlorhexidine rather than iodophor (Level 1 evidence).15 The third is closing of the deep subcutaneous layer of the incision if it exceeds 2 cm in depth (Level 1 evidence).16,17 The fourth is closure of the skin with subcutaneous sutures rather than staples (Level 1 evidence).18 The monofilament suture poliglecaprone 25 is superior to the multifilament suture polyglactin 910 for this purpose (Level 1 evidence).19 Finally, in obese patients (body mass index >30 kg/m2), application of a negative pressure wound vacuum dressing may offer additional protection against infection (Level 1 evidence).20 Such dressings are too expensive, however, to be used routinely in all patients.

Urinary tract infection

The most important measures for preventing postoperative UTIs are identifying and clearing asymptomatic bacteriuria prior to delivery, inserting the urinary catheter prior to surgery using strict sterile technique, and removing the catheter as soon as possible after surgery, ideally within 12 hours.1,4

CASE Resolved

The 2 most likely causes for this patient’s poor response to initial therapy are resistant microorganism and wound infection. If a wound infection can be excluded by physical examination, the patient’s antibiotic regimen should be changed to metronidazole plus ampicillin plus gentamicin (or aztreonam). If an incisional abscess is identified, the incision should be opened and drained, and vancomycin should be added to the treatment regimen. If a wound cellulitis is evident, the incision should not be opened, but vancomycin should be added to the treatment regimen to enhance coverage against aerobic Streptococcus and Staphylococcus species. ●

- Duff WP. Maternal and perinatal infection in pregnancy: bacterial. In: Landon MB, Galan HL, Jauniaux ERM, et al, eds. Gabbe’s Obstetrics: Normal and Problem Pregnancies. 8th ed. Elsevier; 2020:1124-1146.

- Locksmith GJ, Duff P. Assessment of the value of routine blood cultures in the evaluation and treatment of patients with chorioamnionitis. Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol. 1994;2:111-114.

- Duff P. Antibiotic selection in obstetric patients. Infect Dis Clin N Am. 1997;11:1-12.

- Duff P. Maternal and fetal infections. In: Creasy RK, Resnik R, Iams, JD, et al, eds. Creasy & Resnik’s Maternal Fetal Medicine: Principles and Practice. 8th ed. Elsevier; 2019:862-919.

- Haas DM, Morgan S, Contreras K. Vaginal preparation with antiseptic solution before cesarean section for preventing postoperative infections. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;12:CD007892.

- Caissutti C, Saccone G, Zullo F, et al. Vaginal cleansing before cesarean delivery. a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:527-538.

- Sullivan SA, Smith T, Change E, et al. Administration of cefazolin prior to skin incision is superior to cefazolin at cord clamping in preventing postcesarean infectious morbidity; a randomized controlled trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;196:455.e1-455.e5.

- Tita ATN, Hauth JC, Grimes A, et al. Decreasing incidence of postcesarean endometritis with extended-spectrum antibiotic prophylaxis. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;111:51-56.

- Tita ATN, Owen J, Stamm AM, et al. Impact of extended-spectrum antibiotic prophylaxis on incidence of postcesarean surgical wound infection. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;199: 303.e1-303.e3.

- Tita ATN, Szchowski JM, Boggess K, et al. Two antibiotics before cesarean delivery reduce infection rates further than one agent. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:1231-1241.

- Harper LM, Kilgore M, Szychowski JM, et al. Economic evaluation of adjunctive azithromycin prophylaxis for cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:328-334.

- Lasley DS, Eblen A, Yancey MK, et al. The effect of placental removal method on the incidence of postcesarean infections. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1997;176:1250-1254.

- Anorlu RI, Maholwana B, Hofmeyr GJ. Methods of delivering the placenta at cesarean section. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;3:CD004737.

- Cruse PJ, Foord R. A five-year prospective study of 23,649 surgical wounds. Arch Surg. 1973;107:206-209.

- Tuuli MG, Liu J, Stout MJ, et al. A randomized trial comparing skin antiseptic agents at cesarean delivery. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:657-665.

- Del Valle GO, Combs P, Qualls C, et al. Does closure of camper fascia reduce the incidence of post-cesarean superficial wound disruption? Obstet Gynecol. 1992;80:1013-1016.

- Chelmow D. Rodriguez EJ, Sabatini MM. Suture closure of subcutaneous fat and wound disruption after cesarean delivery: a meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;103:974-980.

- Tuuli MG, Rampersod RM, Carbone JF, et al. Staples compared with subcuticular suture for skin closure after cesarean delivery. a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117:682-690.

- Buresch AM, Arsdale AV, Ferzli M, et al. Comparison of subcuticular suture type for skin closure after cesarean delivery. a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:521-526.

- Yu L, Kronen RJ, Simon LE, et al. Prophylactic negative-pressure wound therapy after cesarean is associated with reduced risk of surgical site infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018;218:200-210.

CASE Woman who has undergone recent cesarean delivery

A 23-year-old woman had a primary cesarean delivery 72 hours ago due to an arrest of dilation at 6 cm. She was in labor for 22 hours, and her membranes were ruptured for 18 hours. She had 10 internal vaginal examinations, and the duration of internal fetal monitoring was 12 hours; 24 hours after delivery, she developed a fever of 39°C, in association with lower abdominal pain and tenderness. She was presumptively treated for endometritis with cefepime; 48 hours after the initiation of antibiotics, she remains febrile and symptomatic.

- What are the most likely causes of her persistent fever?

- What should be the next steps in her evaluation?

Cesarean delivery background

Cesarean delivery is now the most common major operation performed in US hospitals. Cesarean delivery rates hover between 25% and 30% in most medical centers in the United States.1 The most common postoperative complication of cesarean delivery is infection. Infection typically takes 1 of 3 forms: endometritis (organ space infection), wound infection (surgical site infection), and urinary tract infection (UTI).1 This article will review the initial differential diagnosis, evaluation, and management of the patient with a postoperative fever and also will describe the appropriate assessment and treatment of the patient who has a persistent postoperative fever despite therapy. The article will also highlight key interventions that help to prevent postoperative infections.

Initial evaluation of the febrile patient

In the first 24 to 48 hours after cesarean delivery, the most common cause of fever is endometritis (organ space infection). This condition is a polymicrobial, mixed aerobic-anaerobic infection (FIGURE). The principal pathogens include anaerobic gram-positive cocci (

The major risk factors for postcesarean endometritis are extended duration of labor and ruptured membranes, multiple internal vaginal examinations, invasive fetal monitoring, and pre-existing colonization with group B Streptococcus and/or the organisms that cause bacterial vaginosis. Affected patients typically have a fever in the range of 38 to 39°C, tachycardia, mild tachypnea, lower abdominal pain and tenderness, and purulent lochia in some individuals.1

Differential for postoperative fever

The initial differential diagnosis of postoperative fever is relatively limited (TABLE 1). In addition to endometritis, it includes extensive atelectasis, perhaps resulting from general anesthesia; lower respiratory tract infection, either viral influenza or bacterial pneumonia; and acute pyelonephritis. A simple infection of the bladder (cystitis or asymptomatic bacteriuria) should not cause a substantial temperature elevation and systemic symptoms.1

Differentiation between these entities usually is possible based on physical examination and a few laboratory tests. The peripheral white blood cell count usually is elevated, and a left shift may be evident. If a respiratory tract infection is suspected, chest radiography is indicated. A urine culture should be obtained if acute pyelonephritis strongly is considered. Lower genital tract cultures are rarely of value, and uncontaminated upper tract cultures are difficult to obtain. I do not believe that blood cultures should be performed as a matter of routine. They are expensive, and the results are often not available until after the patient has cleared her infection and left the hospital. However, I would obtain blood cultures in patients who meet one of these criteria1,2:

- They are immunocompromised (eg, HIV infection).

- They have a cardiac or vascular prosthesis and, thus, are at increased risk of complications related to bacteremia.

- They seem critically ill at the onset of evaluation.

- They fail to respond appropriately to initial therapy.

The cornerstone of therapy is broad spectrum antibiotics that target the multiple organisms responsible for endometritis.3 There are several single agents and several combination antibiotic regimens that provide excellent coverage against the usual pelvic pathogens (TABLE 2). I personally favor the generic combination regimen (clindamycin plus gentamicin) because it is relatively inexpensive and has been very well validated in multiple studies. In patients who have underlying renal dysfunction, aztreonam can be substituted for gentamicin.

Approximately 90% of patients will show clear evidence of clinical improvement (ie, decrease in temperature and resolution of abdominopelvic pain) within 48 hours of starting antibiotics. Patients should then continue therapy until they have been afebrile and asymptomatic for approximately 24 hours. At that point, antibiotics should be discontinued, and the patient can be discharged. With rare exceptions, there is no indication for administration of oral antibiotics on an outpatient basis.1,4

Continue to: Persistent postoperative fever...

Persistent postoperative fever

Resistant microorganism

The most common cause of a persistent fever after initiating antibiotic therapy is a resistant microorganism. There are potential gaps in coverage for the antibiotic regimens commonly used to treat postcesarean endometritis (TABLE 3).1,4 Assuming there is no other obvious cause for treatment failure, I recommend that therapy be changed to the triple combination of metronidazole plus ampicillin plus gentamicin (or aztreonam). The first drug provides superb coverage against anaerobes; the second covers enterococci. Gentamicin or aztreonam cover virtually all aerobic Gram-negative bacilli likely to cause postcesarean infection. I prefer metronidazole rather than clindamycin in this regimen because, unlike clindamycin, it is less likely to trigger diarrhea when used in combination with ampicillin. The 3-drug regimen should be continued until the patient has been afebrile and asymptomatic for approximately 24 hours.1,3,4

Wound infection

The second most common reason for a poor response to initial antibiotic therapy is a wound (surgical site) infection. Wound infections are caused by many of the same pelvic pathogens responsible for endometritis combined with skin flora, notably Streptococcus and Staphylococcus species, including methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA).1,4

Wound infections typically take one of two forms. The first is an actual incisional abscess. The patient is febrile; the margins of the wound are warm, indurated, erythematous, and tender; and purulent material drains from the incision. In this situation, the wound should be opened widely to drain the purulent collection. The fascia should then be probed to be certain that dehiscence has not occurred. In addition, intravenous vancomycin (1 g every 12 h) should be included in the antibiotic regimen to ensure adequate coverage of hospital-acquired MRSA.1,4

The second common presentation of a wound infection is cellulitis. The patient is febrile, and there is a spreading area of erythema, warmth, and exquisite tenderness extending from the edges of the incision; however, no purulent drainage is apparent. In this second scenario, the wound should not be opened, but intravenous vancomycin should be added to the treatment regimen.1,3,4

A third and very rare form of wound infection is necrotizing fasciitis. In affected patients, the margins of the wound are darkened and necrotic rather than erythematous and indurated. Two other key physical findings are crepitance and loss of sensation along the margins of the wound. Necrotizing fasciitis is truly a life-threatening emergency and requires immediate and extensive debridement of the devitalized tissue, combined with broad spectrum therapy with antibiotics that provide excellent coverage against anaerobes, aerobic streptococci (particularly group A streptococci), and staphylococci. The requirement for debridement may be so extensive that a skin graft subsequently is necessary to close the defect.1,4

Continue to: Unusual causes of persistent postoperative fever...

Unusual causes of persistent postoperative fever

If a resistant microorganism and wound infection can be excluded, the clinician then must begin a diligent search for “zebras” (ie, uncommon but potentially serious causes of persistent fever).1,4 One possible cause is a pelvic abscess. These purulent collections typically form in the retrovesicle space as a result of infection of a hematoma that formed between the posterior bladder wall and the lower uterine segment, in the leaves of the broad ligament, or in the posterior cul-de-sac. The abscess may or may not be palpable. The patient’s peripheral white blood cell count usually is elevated, with a preponderance of neutrophils. The best imaging test for an abscess is a computed tomography (CT) scan. Abscesses require drainage, which usually can be accomplished by insertion of a percutaneous drain under ultrasonographic or CT guidance.

A second unusual cause of persistent fever is septic pelvic vein thrombophlebitis. The infected venous emboli usually are present in the ovarian veins, with the right side predominant. The patient’s peripheral white blood cell count usually is elevated, and the infected clots are best imaged by CT scan with contrast or magnetic resonance angiography. The appropriate treatment is continuation of broad-spectrum antibiotics and administration of therapeutic doses of parenteral anticoagulants such as enoxaparin or unfractionated heparin.

A third explanation for persistent fever is retained products of conception. This diagnosis is best made by ultrasonography. The placental fragments should be removed by sharp curettage.

A fourth consideration when evaluating the patient with persistent fever is an allergic drug reaction. In most instances, the increase in the patient’s temperature will correspond with administration of the offending antibiotic(s). Affected patients typically have an increased number of eosinophils in their peripheral white blood cell count. The appropriate management of drug fever is discontinuation of antibiotics.

A final and distinctly unusual consideration is recrudescence of a connective tissue disorder such as systemic lupus erythematosus. The best test to confirm this diagnosis is the serum complement assay, which will demonstrate a decreased serum concentration of complement, reflecting consumption of this serum protein during the inflammatory process. The correct management for this condition is administration of a short course of systemic glucocorticoids. TABLE 4 summarizes a simple, systematic plan for evaluation of the patient with a persistent postoperative fever.

Preventive measures

We all remember the simple but profound statement by Benjamin Franklin, “An ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure.” That folksy adage rings true with respect to postoperative infection because this complication extends hospital stay, increases hospital expense, and causes considerable discomfort and inconvenience for the patient. Therefore, we would do well to prevent as many instances of postoperative infection as possible.

Endometritis

On the basis of well-designed, prospective, randomized trials (Level 1 evidence), 3 interventions have proven effective in reducing the frequency of postcesarean endometritis. The first is irrigation of the vaginal canal preoperatively with an iodophor solution.5,6 The second is preoperative administration of systemic antibiotics.7-9 The combination of cefazolin (2 g IV within 30 minutes of incision) plus azithromycin (500 mg IV over 1 hour prior to incision) is superior to cefazolin alone.10,11 The third important preventive measure is removing the placenta by traction on the umbilical cord rather than by manual extraction.12,13

Wound infection

Several interventions are of proven effectiveness in reducing the frequency of postcesarean wound (surgical site) infection. The first is removal of hair at the incision site by clipping rather than by shaving (Level 2 evidence).14 The second is cleansing of the skin with chlorhexidine rather than iodophor (Level 1 evidence).15 The third is closing of the deep subcutaneous layer of the incision if it exceeds 2 cm in depth (Level 1 evidence).16,17 The fourth is closure of the skin with subcutaneous sutures rather than staples (Level 1 evidence).18 The monofilament suture poliglecaprone 25 is superior to the multifilament suture polyglactin 910 for this purpose (Level 1 evidence).19 Finally, in obese patients (body mass index >30 kg/m2), application of a negative pressure wound vacuum dressing may offer additional protection against infection (Level 1 evidence).20 Such dressings are too expensive, however, to be used routinely in all patients.

Urinary tract infection

The most important measures for preventing postoperative UTIs are identifying and clearing asymptomatic bacteriuria prior to delivery, inserting the urinary catheter prior to surgery using strict sterile technique, and removing the catheter as soon as possible after surgery, ideally within 12 hours.1,4

CASE Resolved

The 2 most likely causes for this patient’s poor response to initial therapy are resistant microorganism and wound infection. If a wound infection can be excluded by physical examination, the patient’s antibiotic regimen should be changed to metronidazole plus ampicillin plus gentamicin (or aztreonam). If an incisional abscess is identified, the incision should be opened and drained, and vancomycin should be added to the treatment regimen. If a wound cellulitis is evident, the incision should not be opened, but vancomycin should be added to the treatment regimen to enhance coverage against aerobic Streptococcus and Staphylococcus species. ●

CASE Woman who has undergone recent cesarean delivery

A 23-year-old woman had a primary cesarean delivery 72 hours ago due to an arrest of dilation at 6 cm. She was in labor for 22 hours, and her membranes were ruptured for 18 hours. She had 10 internal vaginal examinations, and the duration of internal fetal monitoring was 12 hours; 24 hours after delivery, she developed a fever of 39°C, in association with lower abdominal pain and tenderness. She was presumptively treated for endometritis with cefepime; 48 hours after the initiation of antibiotics, she remains febrile and symptomatic.

- What are the most likely causes of her persistent fever?

- What should be the next steps in her evaluation?

Cesarean delivery background

Cesarean delivery is now the most common major operation performed in US hospitals. Cesarean delivery rates hover between 25% and 30% in most medical centers in the United States.1 The most common postoperative complication of cesarean delivery is infection. Infection typically takes 1 of 3 forms: endometritis (organ space infection), wound infection (surgical site infection), and urinary tract infection (UTI).1 This article will review the initial differential diagnosis, evaluation, and management of the patient with a postoperative fever and also will describe the appropriate assessment and treatment of the patient who has a persistent postoperative fever despite therapy. The article will also highlight key interventions that help to prevent postoperative infections.

Initial evaluation of the febrile patient

In the first 24 to 48 hours after cesarean delivery, the most common cause of fever is endometritis (organ space infection). This condition is a polymicrobial, mixed aerobic-anaerobic infection (FIGURE). The principal pathogens include anaerobic gram-positive cocci (

The major risk factors for postcesarean endometritis are extended duration of labor and ruptured membranes, multiple internal vaginal examinations, invasive fetal monitoring, and pre-existing colonization with group B Streptococcus and/or the organisms that cause bacterial vaginosis. Affected patients typically have a fever in the range of 38 to 39°C, tachycardia, mild tachypnea, lower abdominal pain and tenderness, and purulent lochia in some individuals.1

Differential for postoperative fever

The initial differential diagnosis of postoperative fever is relatively limited (TABLE 1). In addition to endometritis, it includes extensive atelectasis, perhaps resulting from general anesthesia; lower respiratory tract infection, either viral influenza or bacterial pneumonia; and acute pyelonephritis. A simple infection of the bladder (cystitis or asymptomatic bacteriuria) should not cause a substantial temperature elevation and systemic symptoms.1

Differentiation between these entities usually is possible based on physical examination and a few laboratory tests. The peripheral white blood cell count usually is elevated, and a left shift may be evident. If a respiratory tract infection is suspected, chest radiography is indicated. A urine culture should be obtained if acute pyelonephritis strongly is considered. Lower genital tract cultures are rarely of value, and uncontaminated upper tract cultures are difficult to obtain. I do not believe that blood cultures should be performed as a matter of routine. They are expensive, and the results are often not available until after the patient has cleared her infection and left the hospital. However, I would obtain blood cultures in patients who meet one of these criteria1,2:

- They are immunocompromised (eg, HIV infection).

- They have a cardiac or vascular prosthesis and, thus, are at increased risk of complications related to bacteremia.

- They seem critically ill at the onset of evaluation.

- They fail to respond appropriately to initial therapy.

The cornerstone of therapy is broad spectrum antibiotics that target the multiple organisms responsible for endometritis.3 There are several single agents and several combination antibiotic regimens that provide excellent coverage against the usual pelvic pathogens (TABLE 2). I personally favor the generic combination regimen (clindamycin plus gentamicin) because it is relatively inexpensive and has been very well validated in multiple studies. In patients who have underlying renal dysfunction, aztreonam can be substituted for gentamicin.

Approximately 90% of patients will show clear evidence of clinical improvement (ie, decrease in temperature and resolution of abdominopelvic pain) within 48 hours of starting antibiotics. Patients should then continue therapy until they have been afebrile and asymptomatic for approximately 24 hours. At that point, antibiotics should be discontinued, and the patient can be discharged. With rare exceptions, there is no indication for administration of oral antibiotics on an outpatient basis.1,4

Continue to: Persistent postoperative fever...

Persistent postoperative fever

Resistant microorganism

The most common cause of a persistent fever after initiating antibiotic therapy is a resistant microorganism. There are potential gaps in coverage for the antibiotic regimens commonly used to treat postcesarean endometritis (TABLE 3).1,4 Assuming there is no other obvious cause for treatment failure, I recommend that therapy be changed to the triple combination of metronidazole plus ampicillin plus gentamicin (or aztreonam). The first drug provides superb coverage against anaerobes; the second covers enterococci. Gentamicin or aztreonam cover virtually all aerobic Gram-negative bacilli likely to cause postcesarean infection. I prefer metronidazole rather than clindamycin in this regimen because, unlike clindamycin, it is less likely to trigger diarrhea when used in combination with ampicillin. The 3-drug regimen should be continued until the patient has been afebrile and asymptomatic for approximately 24 hours.1,3,4

Wound infection

The second most common reason for a poor response to initial antibiotic therapy is a wound (surgical site) infection. Wound infections are caused by many of the same pelvic pathogens responsible for endometritis combined with skin flora, notably Streptococcus and Staphylococcus species, including methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA).1,4

Wound infections typically take one of two forms. The first is an actual incisional abscess. The patient is febrile; the margins of the wound are warm, indurated, erythematous, and tender; and purulent material drains from the incision. In this situation, the wound should be opened widely to drain the purulent collection. The fascia should then be probed to be certain that dehiscence has not occurred. In addition, intravenous vancomycin (1 g every 12 h) should be included in the antibiotic regimen to ensure adequate coverage of hospital-acquired MRSA.1,4

The second common presentation of a wound infection is cellulitis. The patient is febrile, and there is a spreading area of erythema, warmth, and exquisite tenderness extending from the edges of the incision; however, no purulent drainage is apparent. In this second scenario, the wound should not be opened, but intravenous vancomycin should be added to the treatment regimen.1,3,4

A third and very rare form of wound infection is necrotizing fasciitis. In affected patients, the margins of the wound are darkened and necrotic rather than erythematous and indurated. Two other key physical findings are crepitance and loss of sensation along the margins of the wound. Necrotizing fasciitis is truly a life-threatening emergency and requires immediate and extensive debridement of the devitalized tissue, combined with broad spectrum therapy with antibiotics that provide excellent coverage against anaerobes, aerobic streptococci (particularly group A streptococci), and staphylococci. The requirement for debridement may be so extensive that a skin graft subsequently is necessary to close the defect.1,4

Continue to: Unusual causes of persistent postoperative fever...

Unusual causes of persistent postoperative fever

If a resistant microorganism and wound infection can be excluded, the clinician then must begin a diligent search for “zebras” (ie, uncommon but potentially serious causes of persistent fever).1,4 One possible cause is a pelvic abscess. These purulent collections typically form in the retrovesicle space as a result of infection of a hematoma that formed between the posterior bladder wall and the lower uterine segment, in the leaves of the broad ligament, or in the posterior cul-de-sac. The abscess may or may not be palpable. The patient’s peripheral white blood cell count usually is elevated, with a preponderance of neutrophils. The best imaging test for an abscess is a computed tomography (CT) scan. Abscesses require drainage, which usually can be accomplished by insertion of a percutaneous drain under ultrasonographic or CT guidance.

A second unusual cause of persistent fever is septic pelvic vein thrombophlebitis. The infected venous emboli usually are present in the ovarian veins, with the right side predominant. The patient’s peripheral white blood cell count usually is elevated, and the infected clots are best imaged by CT scan with contrast or magnetic resonance angiography. The appropriate treatment is continuation of broad-spectrum antibiotics and administration of therapeutic doses of parenteral anticoagulants such as enoxaparin or unfractionated heparin.

A third explanation for persistent fever is retained products of conception. This diagnosis is best made by ultrasonography. The placental fragments should be removed by sharp curettage.

A fourth consideration when evaluating the patient with persistent fever is an allergic drug reaction. In most instances, the increase in the patient’s temperature will correspond with administration of the offending antibiotic(s). Affected patients typically have an increased number of eosinophils in their peripheral white blood cell count. The appropriate management of drug fever is discontinuation of antibiotics.

A final and distinctly unusual consideration is recrudescence of a connective tissue disorder such as systemic lupus erythematosus. The best test to confirm this diagnosis is the serum complement assay, which will demonstrate a decreased serum concentration of complement, reflecting consumption of this serum protein during the inflammatory process. The correct management for this condition is administration of a short course of systemic glucocorticoids. TABLE 4 summarizes a simple, systematic plan for evaluation of the patient with a persistent postoperative fever.

Preventive measures