User login

Infectious disease pop quiz: Clinical challenge #17 for the ObGyn

What are the best tests for identification of a patient with chronic hepatitis B infection?

Continue to the answer...

Patients with chronic hepatitis B infection typically test positive for the hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) and for IgG antibody to the hepatitis B core antigen (HBcAg). In addition, they also may test positive for the hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg), and their viral load can be quantified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) when significant antigenemia is present. The presence of the e antigen indicates a high rate of viral replication and a corresponding high rate of infectivity.

- Duff P. Maternal and perinatal infections: bacterial. In: Landon MB, Galan HL, Jauniaux ERM, et al. Gabbe’s Obstetrics: Normal and Problem Pregnancies. 8th ed. Elsevier; 2021:1124-1146.

- Duff P. Maternal and fetal infections. In: Resnik R, Lockwood CJ, Moore TJ, et al. Creasy & Resnik’s Maternal-Fetal Medicine: Principles and Practice. 8th ed. Elsevier; 2019:862-919.

What are the best tests for identification of a patient with chronic hepatitis B infection?

Continue to the answer...

Patients with chronic hepatitis B infection typically test positive for the hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) and for IgG antibody to the hepatitis B core antigen (HBcAg). In addition, they also may test positive for the hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg), and their viral load can be quantified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) when significant antigenemia is present. The presence of the e antigen indicates a high rate of viral replication and a corresponding high rate of infectivity.

What are the best tests for identification of a patient with chronic hepatitis B infection?

Continue to the answer...

Patients with chronic hepatitis B infection typically test positive for the hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) and for IgG antibody to the hepatitis B core antigen (HBcAg). In addition, they also may test positive for the hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg), and their viral load can be quantified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) when significant antigenemia is present. The presence of the e antigen indicates a high rate of viral replication and a corresponding high rate of infectivity.

- Duff P. Maternal and perinatal infections: bacterial. In: Landon MB, Galan HL, Jauniaux ERM, et al. Gabbe’s Obstetrics: Normal and Problem Pregnancies. 8th ed. Elsevier; 2021:1124-1146.

- Duff P. Maternal and fetal infections. In: Resnik R, Lockwood CJ, Moore TJ, et al. Creasy & Resnik’s Maternal-Fetal Medicine: Principles and Practice. 8th ed. Elsevier; 2019:862-919.

- Duff P. Maternal and perinatal infections: bacterial. In: Landon MB, Galan HL, Jauniaux ERM, et al. Gabbe’s Obstetrics: Normal and Problem Pregnancies. 8th ed. Elsevier; 2021:1124-1146.

- Duff P. Maternal and fetal infections. In: Resnik R, Lockwood CJ, Moore TJ, et al. Creasy & Resnik’s Maternal-Fetal Medicine: Principles and Practice. 8th ed. Elsevier; 2019:862-919.

Infectious disease pop quiz: Clinical challenge #16 for the ObGyn

What is the best test for the diagnosis of acute hepatitis A infection?

Continue to the answer...

The single best test for the diagnosis of acute hepatitis A infection is detection of immunoglobulin M (IgM)–specific antibody to the virus.

- Duff P. Maternal and perinatal infections: bacterial. In: Landon MB, Galan HL, Jauniaux ERM, et al. Gabbe’s Obstetrics: Normal and Problem Pregnancies. 8th ed. Elsevier; 2021:1124-1146.

- Duff P. Maternal and fetal infections. In: Resnik R, Lockwood CJ, Moore TJ, et al. Creasy & Resnik’s Maternal-Fetal Medicine: Principles and Practice. 8th ed. Elsevier; 2019:862-919.

What is the best test for the diagnosis of acute hepatitis A infection?

Continue to the answer...

The single best test for the diagnosis of acute hepatitis A infection is detection of immunoglobulin M (IgM)–specific antibody to the virus.

What is the best test for the diagnosis of acute hepatitis A infection?

Continue to the answer...

The single best test for the diagnosis of acute hepatitis A infection is detection of immunoglobulin M (IgM)–specific antibody to the virus.

- Duff P. Maternal and perinatal infections: bacterial. In: Landon MB, Galan HL, Jauniaux ERM, et al. Gabbe’s Obstetrics: Normal and Problem Pregnancies. 8th ed. Elsevier; 2021:1124-1146.

- Duff P. Maternal and fetal infections. In: Resnik R, Lockwood CJ, Moore TJ, et al. Creasy & Resnik’s Maternal-Fetal Medicine: Principles and Practice. 8th ed. Elsevier; 2019:862-919.

- Duff P. Maternal and perinatal infections: bacterial. In: Landon MB, Galan HL, Jauniaux ERM, et al. Gabbe’s Obstetrics: Normal and Problem Pregnancies. 8th ed. Elsevier; 2021:1124-1146.

- Duff P. Maternal and fetal infections. In: Resnik R, Lockwood CJ, Moore TJ, et al. Creasy & Resnik’s Maternal-Fetal Medicine: Principles and Practice. 8th ed. Elsevier; 2019:862-919.

Infectious disease pop quiz: Clinical challenge #15 for the ObGyn

What is the most appropriate treatment for a pregnant woman who is moderately to severely ill with COVID-19 infection?

Continue to the answer...

Moderately to severely ill pregnant women with COVID-19 infection should be hospitalized and treated with supplementary oxygen, remdesivir, and dexamethasone. Other possible therapies include inhaled nitric oxide, baricitinib (a Janus kinase inhibitor), and tocilizumab (an anti-interleukin 6 receptor antibody). (RECOVERY Collaborative Group; Horby P, Lim WS, Emberson JR, et al. Dexamethasone in hospitalized patients with COVID-19. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:693-704. Kalil AC, Patterson TF, Mehta AK, et al; ACTT-2 Study Group. Baricitinib plus remdesivir for hospitalized adults with COVID-19. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:795-807. Berlin DA, Gulick RM, Martinez FJ, et al. Severe COVID-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;383;2451-2460.)

- Duff P. Maternal and perinatal infections: bacterial. In: Landon MB, Galan HL, Jauniaux ERM, et al. Gabbe’s Obstetrics: Normal and Problem Pregnancies. 8th ed. Elsevier; 2021:1124-1146.

- Duff P. Maternal and fetal infections. In: Resnik R, Lockwood CJ, Moore TJ, et al. Creasy & Resnik’s Maternal-Fetal Medicine: Principles and Practice. 8th ed. Elsevier; 2019:862-919.

What is the most appropriate treatment for a pregnant woman who is moderately to severely ill with COVID-19 infection?

Continue to the answer...

Moderately to severely ill pregnant women with COVID-19 infection should be hospitalized and treated with supplementary oxygen, remdesivir, and dexamethasone. Other possible therapies include inhaled nitric oxide, baricitinib (a Janus kinase inhibitor), and tocilizumab (an anti-interleukin 6 receptor antibody). (RECOVERY Collaborative Group; Horby P, Lim WS, Emberson JR, et al. Dexamethasone in hospitalized patients with COVID-19. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:693-704. Kalil AC, Patterson TF, Mehta AK, et al; ACTT-2 Study Group. Baricitinib plus remdesivir for hospitalized adults with COVID-19. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:795-807. Berlin DA, Gulick RM, Martinez FJ, et al. Severe COVID-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;383;2451-2460.)

What is the most appropriate treatment for a pregnant woman who is moderately to severely ill with COVID-19 infection?

Continue to the answer...

Moderately to severely ill pregnant women with COVID-19 infection should be hospitalized and treated with supplementary oxygen, remdesivir, and dexamethasone. Other possible therapies include inhaled nitric oxide, baricitinib (a Janus kinase inhibitor), and tocilizumab (an anti-interleukin 6 receptor antibody). (RECOVERY Collaborative Group; Horby P, Lim WS, Emberson JR, et al. Dexamethasone in hospitalized patients with COVID-19. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:693-704. Kalil AC, Patterson TF, Mehta AK, et al; ACTT-2 Study Group. Baricitinib plus remdesivir for hospitalized adults with COVID-19. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:795-807. Berlin DA, Gulick RM, Martinez FJ, et al. Severe COVID-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;383;2451-2460.)

- Duff P. Maternal and perinatal infections: bacterial. In: Landon MB, Galan HL, Jauniaux ERM, et al. Gabbe’s Obstetrics: Normal and Problem Pregnancies. 8th ed. Elsevier; 2021:1124-1146.

- Duff P. Maternal and fetal infections. In: Resnik R, Lockwood CJ, Moore TJ, et al. Creasy & Resnik’s Maternal-Fetal Medicine: Principles and Practice. 8th ed. Elsevier; 2019:862-919.

- Duff P. Maternal and perinatal infections: bacterial. In: Landon MB, Galan HL, Jauniaux ERM, et al. Gabbe’s Obstetrics: Normal and Problem Pregnancies. 8th ed. Elsevier; 2021:1124-1146.

- Duff P. Maternal and fetal infections. In: Resnik R, Lockwood CJ, Moore TJ, et al. Creasy & Resnik’s Maternal-Fetal Medicine: Principles and Practice. 8th ed. Elsevier; 2019:862-919.

Infectious disease pop quiz: Clinical challenge #14 for the ObGyn

What tests are best for the diagnosis of COVID-19 infection?

Continue to the answer...

The 2 key diagnostic tests for COVID-19 infection are detecting antigen in nasopharyngeal washings or saliva by nucleic acid amplification tests and identifying ground-glass opacities on computed tomography imaging of the chest. (Berlin DA, Gulick RM, Martinez FJ. Severe Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:2451-2460.)

- Duff P. Maternal and perinatal infections: bacterial. In: Landon MB, Galan HL, Jauniaux ERM, et al. Gabbe’s Obstetrics: Normal and Problem Pregnancies. 8th ed. Elsevier; 2021:1124-1146.

- Duff P. Maternal and fetal infections. In: Resnik R, Lockwood CJ, Moore TJ, et al. Creasy & Resnik’s Maternal-Fetal Medicine: Principles and Practice. 8th ed. Elsevier; 2019:862-919.

What tests are best for the diagnosis of COVID-19 infection?

Continue to the answer...

The 2 key diagnostic tests for COVID-19 infection are detecting antigen in nasopharyngeal washings or saliva by nucleic acid amplification tests and identifying ground-glass opacities on computed tomography imaging of the chest. (Berlin DA, Gulick RM, Martinez FJ. Severe Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:2451-2460.)

What tests are best for the diagnosis of COVID-19 infection?

Continue to the answer...

The 2 key diagnostic tests for COVID-19 infection are detecting antigen in nasopharyngeal washings or saliva by nucleic acid amplification tests and identifying ground-glass opacities on computed tomography imaging of the chest. (Berlin DA, Gulick RM, Martinez FJ. Severe Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:2451-2460.)

- Duff P. Maternal and perinatal infections: bacterial. In: Landon MB, Galan HL, Jauniaux ERM, et al. Gabbe’s Obstetrics: Normal and Problem Pregnancies. 8th ed. Elsevier; 2021:1124-1146.

- Duff P. Maternal and fetal infections. In: Resnik R, Lockwood CJ, Moore TJ, et al. Creasy & Resnik’s Maternal-Fetal Medicine: Principles and Practice. 8th ed. Elsevier; 2019:862-919.

- Duff P. Maternal and perinatal infections: bacterial. In: Landon MB, Galan HL, Jauniaux ERM, et al. Gabbe’s Obstetrics: Normal and Problem Pregnancies. 8th ed. Elsevier; 2021:1124-1146.

- Duff P. Maternal and fetal infections. In: Resnik R, Lockwood CJ, Moore TJ, et al. Creasy & Resnik’s Maternal-Fetal Medicine: Principles and Practice. 8th ed. Elsevier; 2019:862-919.

Infectious disease pop quiz: Clinical challenge #13 for the ObGyn

For a moderately ill pregnant woman, what is the most appropriate antibiotic combination for inpatient treatment of community-acquired pneumonia?

Continue to the answer...

This patient should be treated with intravenous ceftriaxone (2 g every 24 hours) plus oral or intravenous azithromycin. The appropriate oral dose of azithromycin is 500 mg on day 1, then 250 mg daily for 4 doses. The appropriate intravenous dose of azithromycin is 500 mg every 24 hours. The goal is to provide appropriate coverage for the most likely pathogens: Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, Moraxella catarrhalis, and mycoplasmas. (Antibacterial drugs for community-acquired pneumonia. Med Lett Drugs Ther. 2021:63:10-14. Postma DF, van Werkoven CH, van Eldin LJ, et al; CAP-START Study Group. Antibiotic treatment strategies for community acquired pneumonia in adults. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:1312-1323.)

- Duff P. Maternal and perinatal infections: bacterial. In: Landon MB, Galan HL, Jauniaux ERM, et al. Gabbe’s Obstetrics: Normal and Problem Pregnancies. 8th ed. Elsevier; 2021:1124-1146.

- Duff P. Maternal and fetal infections. In: Resnik R, Lockwood CJ, Moore TJ, et al. Creasy & Resnik’s Maternal-Fetal Medicine: Principles and Practice. 8th ed. Elsevier; 2019:862-919.

For a moderately ill pregnant woman, what is the most appropriate antibiotic combination for inpatient treatment of community-acquired pneumonia?

Continue to the answer...

This patient should be treated with intravenous ceftriaxone (2 g every 24 hours) plus oral or intravenous azithromycin. The appropriate oral dose of azithromycin is 500 mg on day 1, then 250 mg daily for 4 doses. The appropriate intravenous dose of azithromycin is 500 mg every 24 hours. The goal is to provide appropriate coverage for the most likely pathogens: Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, Moraxella catarrhalis, and mycoplasmas. (Antibacterial drugs for community-acquired pneumonia. Med Lett Drugs Ther. 2021:63:10-14. Postma DF, van Werkoven CH, van Eldin LJ, et al; CAP-START Study Group. Antibiotic treatment strategies for community acquired pneumonia in adults. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:1312-1323.)

For a moderately ill pregnant woman, what is the most appropriate antibiotic combination for inpatient treatment of community-acquired pneumonia?

Continue to the answer...

This patient should be treated with intravenous ceftriaxone (2 g every 24 hours) plus oral or intravenous azithromycin. The appropriate oral dose of azithromycin is 500 mg on day 1, then 250 mg daily for 4 doses. The appropriate intravenous dose of azithromycin is 500 mg every 24 hours. The goal is to provide appropriate coverage for the most likely pathogens: Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, Moraxella catarrhalis, and mycoplasmas. (Antibacterial drugs for community-acquired pneumonia. Med Lett Drugs Ther. 2021:63:10-14. Postma DF, van Werkoven CH, van Eldin LJ, et al; CAP-START Study Group. Antibiotic treatment strategies for community acquired pneumonia in adults. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:1312-1323.)

- Duff P. Maternal and perinatal infections: bacterial. In: Landon MB, Galan HL, Jauniaux ERM, et al. Gabbe’s Obstetrics: Normal and Problem Pregnancies. 8th ed. Elsevier; 2021:1124-1146.

- Duff P. Maternal and fetal infections. In: Resnik R, Lockwood CJ, Moore TJ, et al. Creasy & Resnik’s Maternal-Fetal Medicine: Principles and Practice. 8th ed. Elsevier; 2019:862-919.

- Duff P. Maternal and perinatal infections: bacterial. In: Landon MB, Galan HL, Jauniaux ERM, et al. Gabbe’s Obstetrics: Normal and Problem Pregnancies. 8th ed. Elsevier; 2021:1124-1146.

- Duff P. Maternal and fetal infections. In: Resnik R, Lockwood CJ, Moore TJ, et al. Creasy & Resnik’s Maternal-Fetal Medicine: Principles and Practice. 8th ed. Elsevier; 2019:862-919.

Infectious disease pop quiz: Clinical challenge #12 for the ObGyn

What are the best office-based tests for the diagnosis of bacterial vaginosis?

Continue to the answer...

In patients with bacterial vaginosis, the vaginal pH typically is elevated in the range of 4.5. When a drop of potassium hydroxide solution is added to the vaginal secretions, a characteristic fishlike (amine) odor is liberated (positive “whiff test”). With saline microscopy, the key findings are a relative absence of lactobacilli in the background, an abundance of small cocci and bacilli, and the presence of clue cells, which are epithelial cells studded with bacteria along their outer margin.

- Duff P. Maternal and perinatal infections: bacterial. In: Landon MB, Galan HL, Jauniaux ERM, et al. Gabbe’s Obstetrics: Normal and Problem Pregnancies. 8th ed. Elsevier; 2021:1124-1146.

- Duff P. Maternal and fetal infections. In: Resnik R, Lockwood CJ, Moore TJ, et al. Creasy & Resnik’s Maternal-Fetal Medicine: Principles and Practice. 8th ed. Elsevier; 2019:862-919.

What are the best office-based tests for the diagnosis of bacterial vaginosis?

Continue to the answer...

In patients with bacterial vaginosis, the vaginal pH typically is elevated in the range of 4.5. When a drop of potassium hydroxide solution is added to the vaginal secretions, a characteristic fishlike (amine) odor is liberated (positive “whiff test”). With saline microscopy, the key findings are a relative absence of lactobacilli in the background, an abundance of small cocci and bacilli, and the presence of clue cells, which are epithelial cells studded with bacteria along their outer margin.

What are the best office-based tests for the diagnosis of bacterial vaginosis?

Continue to the answer...

In patients with bacterial vaginosis, the vaginal pH typically is elevated in the range of 4.5. When a drop of potassium hydroxide solution is added to the vaginal secretions, a characteristic fishlike (amine) odor is liberated (positive “whiff test”). With saline microscopy, the key findings are a relative absence of lactobacilli in the background, an abundance of small cocci and bacilli, and the presence of clue cells, which are epithelial cells studded with bacteria along their outer margin.

- Duff P. Maternal and perinatal infections: bacterial. In: Landon MB, Galan HL, Jauniaux ERM, et al. Gabbe’s Obstetrics: Normal and Problem Pregnancies. 8th ed. Elsevier; 2021:1124-1146.

- Duff P. Maternal and fetal infections. In: Resnik R, Lockwood CJ, Moore TJ, et al. Creasy & Resnik’s Maternal-Fetal Medicine: Principles and Practice. 8th ed. Elsevier; 2019:862-919.

- Duff P. Maternal and perinatal infections: bacterial. In: Landon MB, Galan HL, Jauniaux ERM, et al. Gabbe’s Obstetrics: Normal and Problem Pregnancies. 8th ed. Elsevier; 2021:1124-1146.

- Duff P. Maternal and fetal infections. In: Resnik R, Lockwood CJ, Moore TJ, et al. Creasy & Resnik’s Maternal-Fetal Medicine: Principles and Practice. 8th ed. Elsevier; 2019:862-919.

Infectious disease pop quiz: Clinical challenge #11 for the ObGyn

In a pregnant woman with a history of recurrent herpes simplex virus infection, what is the best way to prevent an outbreak of lesions near term?

Continue to the answer...

Obstetric patients with a history of recurrent herpes simplex infection should be treated with acyclovir 400 mg orally 3 times daily from 36 weeks until delivery. This regimen significantly reduces the likelihood of a recurrent outbreak near the time of delivery, which if it occurred, would necessitate a cesarean delivery. In patients at increased risk for preterm delivery, the prophylactic regimen should be started earlier.

Valacyclovir, 500 mg orally twice daily, is an acceptable alternative but is significantly more expensive.

- Duff P. Maternal and perinatal infections: bacterial. In: Landon MB, Galan HL, Jauniaux ERM, et al. Gabbe’s Obstetrics: Normal and Problem Pregnancies. 8th ed. Elsevier; 2021:1124-1146.

- Duff P. Maternal and fetal infections. In: Resnik R, Lockwood CJ, Moore TJ, et al. Creasy & Resnik’s Maternal-Fetal Medicine: Principles and Practice. 8th ed. Elsevier; 2019:862-919.

In a pregnant woman with a history of recurrent herpes simplex virus infection, what is the best way to prevent an outbreak of lesions near term?

Continue to the answer...

Obstetric patients with a history of recurrent herpes simplex infection should be treated with acyclovir 400 mg orally 3 times daily from 36 weeks until delivery. This regimen significantly reduces the likelihood of a recurrent outbreak near the time of delivery, which if it occurred, would necessitate a cesarean delivery. In patients at increased risk for preterm delivery, the prophylactic regimen should be started earlier.

Valacyclovir, 500 mg orally twice daily, is an acceptable alternative but is significantly more expensive.

In a pregnant woman with a history of recurrent herpes simplex virus infection, what is the best way to prevent an outbreak of lesions near term?

Continue to the answer...

Obstetric patients with a history of recurrent herpes simplex infection should be treated with acyclovir 400 mg orally 3 times daily from 36 weeks until delivery. This regimen significantly reduces the likelihood of a recurrent outbreak near the time of delivery, which if it occurred, would necessitate a cesarean delivery. In patients at increased risk for preterm delivery, the prophylactic regimen should be started earlier.

Valacyclovir, 500 mg orally twice daily, is an acceptable alternative but is significantly more expensive.

- Duff P. Maternal and perinatal infections: bacterial. In: Landon MB, Galan HL, Jauniaux ERM, et al. Gabbe’s Obstetrics: Normal and Problem Pregnancies. 8th ed. Elsevier; 2021:1124-1146.

- Duff P. Maternal and fetal infections. In: Resnik R, Lockwood CJ, Moore TJ, et al. Creasy & Resnik’s Maternal-Fetal Medicine: Principles and Practice. 8th ed. Elsevier; 2019:862-919.

- Duff P. Maternal and perinatal infections: bacterial. In: Landon MB, Galan HL, Jauniaux ERM, et al. Gabbe’s Obstetrics: Normal and Problem Pregnancies. 8th ed. Elsevier; 2021:1124-1146.

- Duff P. Maternal and fetal infections. In: Resnik R, Lockwood CJ, Moore TJ, et al. Creasy & Resnik’s Maternal-Fetal Medicine: Principles and Practice. 8th ed. Elsevier; 2019:862-919.

Infectious disease pop quiz: Clinical challenge #10 for the ObGyn

What are the characteristic mucocutaneous lesions of primary, secondary, and tertiary syphilis?

Continue to answer...

The characteristic mucosal lesion of primary syphilis is the painless chancre. The usual mucocutaneous manifestations of secondary syphilis are maculopapular lesions (red or violet in color) on the palms and soles, mucous patches on the oral membranes, and condyloma lata on the genitalia. The classic mucocutaneous lesion of tertiary syphilis is the gumma.

Other serious manifestations of advanced syphilis include central nervous system abnormalities, such as tabes dorsalis, the Argyll Robertson pupil, and dementia, and cardiac abnormalities, such as aortitis, which can lead to a dissecting aneurysm of the aortic root. (Workowski KA, Bolan GA. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2015. MMWR Morbid Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64[RR3]:1-137.)

- Duff P. Maternal and perinatal infections: bacterial. In: Landon MB, Galan HL, Jauniaux ERM, et al. Gabbe’s Obstetrics: Normal and Problem Pregnancies. 8th ed. Elsevier; 2021:1124-1146.

- Duff P. Maternal and fetal infections. In: Resnik R, Lockwood CJ, Moore TJ, et al. Creasy & Resnik’s Maternal-Fetal Medicine: Principles and Practice. 8th ed. Elsevier; 2019:862-919.

What are the characteristic mucocutaneous lesions of primary, secondary, and tertiary syphilis?

Continue to answer...

The characteristic mucosal lesion of primary syphilis is the painless chancre. The usual mucocutaneous manifestations of secondary syphilis are maculopapular lesions (red or violet in color) on the palms and soles, mucous patches on the oral membranes, and condyloma lata on the genitalia. The classic mucocutaneous lesion of tertiary syphilis is the gumma.

Other serious manifestations of advanced syphilis include central nervous system abnormalities, such as tabes dorsalis, the Argyll Robertson pupil, and dementia, and cardiac abnormalities, such as aortitis, which can lead to a dissecting aneurysm of the aortic root. (Workowski KA, Bolan GA. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2015. MMWR Morbid Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64[RR3]:1-137.)

What are the characteristic mucocutaneous lesions of primary, secondary, and tertiary syphilis?

Continue to answer...

The characteristic mucosal lesion of primary syphilis is the painless chancre. The usual mucocutaneous manifestations of secondary syphilis are maculopapular lesions (red or violet in color) on the palms and soles, mucous patches on the oral membranes, and condyloma lata on the genitalia. The classic mucocutaneous lesion of tertiary syphilis is the gumma.

Other serious manifestations of advanced syphilis include central nervous system abnormalities, such as tabes dorsalis, the Argyll Robertson pupil, and dementia, and cardiac abnormalities, such as aortitis, which can lead to a dissecting aneurysm of the aortic root. (Workowski KA, Bolan GA. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2015. MMWR Morbid Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64[RR3]:1-137.)

- Duff P. Maternal and perinatal infections: bacterial. In: Landon MB, Galan HL, Jauniaux ERM, et al. Gabbe’s Obstetrics: Normal and Problem Pregnancies. 8th ed. Elsevier; 2021:1124-1146.

- Duff P. Maternal and fetal infections. In: Resnik R, Lockwood CJ, Moore TJ, et al. Creasy & Resnik’s Maternal-Fetal Medicine: Principles and Practice. 8th ed. Elsevier; 2019:862-919.

- Duff P. Maternal and perinatal infections: bacterial. In: Landon MB, Galan HL, Jauniaux ERM, et al. Gabbe’s Obstetrics: Normal and Problem Pregnancies. 8th ed. Elsevier; 2021:1124-1146.

- Duff P. Maternal and fetal infections. In: Resnik R, Lockwood CJ, Moore TJ, et al. Creasy & Resnik’s Maternal-Fetal Medicine: Principles and Practice. 8th ed. Elsevier; 2019:862-919.

UTIs in pregnancy: Managing urethritis, asymptomatic bacteriuria, cystitis, and pyelonephritis

CASE Pregnant woman with dysuria and suprapubic pain

A 25-year-old primigravid woman at 18 weeks of gestation requests evaluation because of the acute onset of frequent urination, dysuria, urination hesitancy, and suprapubic pain on the morning following intercourse. She has not experienced similar symptoms in the past. On physical examination, her temperature is 38 °C, pulse is 96 beats per minute, respirations are 18 per minute, and blood pressure is 100/76 mm Hg. She has no urethral discharge but is tender to palpation in the suprapubic area.

- What is the most likely diagnosis?

- What tests would be of greatest value in confirming the diagnosis?

- What is the most appropriate treatment for this patient?

Meet our perpetrator

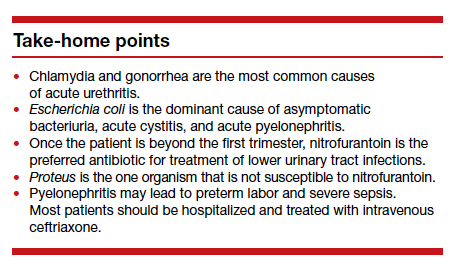

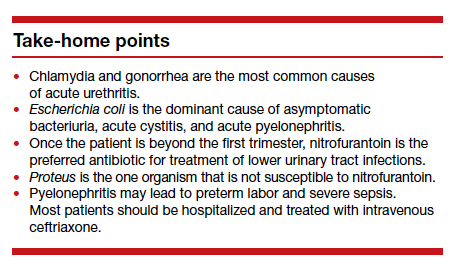

Urinary tract infections (UTIs) are among the most common infections that occur during pregnancy. They may take one of 4 forms: acute urethritis, asymptomatic bacteriuria, acute cystitis, and acute pyelonephritis.1 The first 3 conditions usually are straightforward to diagnose and treat, and they usually do not cause major problems for the mother or fetus. The latter, however, can cause serious complications that pose risk to the mother and fetus.

This article will review the microbiology, clinical manifestations, diagnosis, and treatment of these 4 disorders in pregnancy. Particular emphasis will be placed on measures to avoid adverse effects on the mother and fetus from antimicrobial agents.

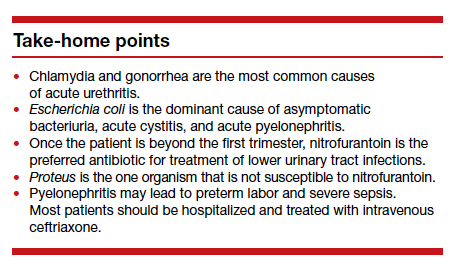

Acute urethritis

Acute urethritis can be caused by low concentrations of coliform organisms in the lower urinary tract, but it usually is secondary to infection by Neisseria gonorrhea or Chlamydia trachomatis. In most prenatal populations, the prevalence of one or the other of these 2 infections is approximately 5%.1

The most common clinical manifestations of acute urethritis are a purulent urethral discharge, increased frequency of urination, dysuria, and urination hesitancy. The diagnosis most easily is confirmed by obtaining a specimen of urethral discharge or urine and evaluating the sample by a nucleic acid amplification test for both gonorrhea and chlamydia.

Antibiotic therapy is preferred. The current recommended treatment for gonococcal urethritis is a single intramuscular injection of ceftriaxone 500 mg. If the patient prefers oral therapy, she can receive cefixime 800 mg in a single dose. For patients with an allergy to beta-lactam antibiotics, the alternative regimen is gentamicin 240 mg in a single intramuscular injection, combined with oral azithromycin in a single 2,000-mg dose. For treatment of chlamydia in pregnancy, the recommended therapy is azithromycin 1,000 mg in a single oral dose.2 A test of cure should be performed within 4 weeks of treatment.

Asymptomatic bacteriuria

Asymptomatic bacteriuria (ASB) is the most common UTI in women. Approximately 5% to 8% of all sexually active women have ASB. The condition is not unique to pregnancy; it is associated primarily with the assumption of coital activity. In point of fact, the ASB typically precedes pregnancy by several years.1

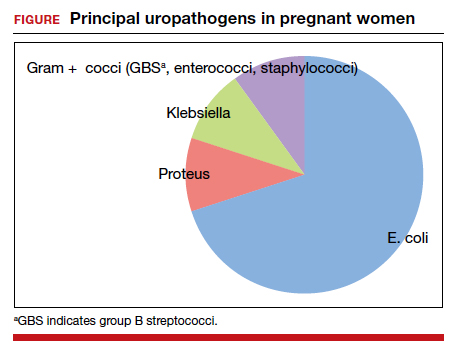

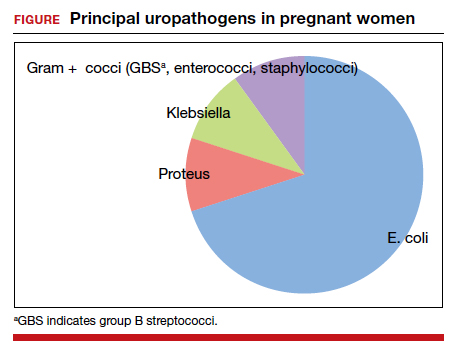

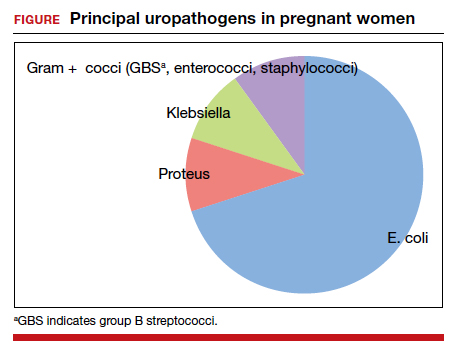

The principal pathogens responsible for ASB are shown in the FIGURE. Over 80% of first-time infections are secondary to Escherichia coli. As more recurrent episodes occur, the other Gram-negative bacilli (ie, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Proteus species) become more prevalent. The 3 major Gram-positive cocci that cause UTIs are enterococci, Staphylococcus saprophyticus, and group B streptococci.1,3,4

In nonpregnant women, ASB usually remains completely asymptomatic, and ascending infections only rarely occur. In pregnancy, however, urinary stasis is present due to the effects of progesterone on ureteral peristalsis and because of pressure on the ureters (particularly the right) by the expanding gravid uterus. As a result, ascending infection may occur in approximately 20% of patients if the lower tract infection is not identified and treated adequately.1

Clean-catch specimens and treatment

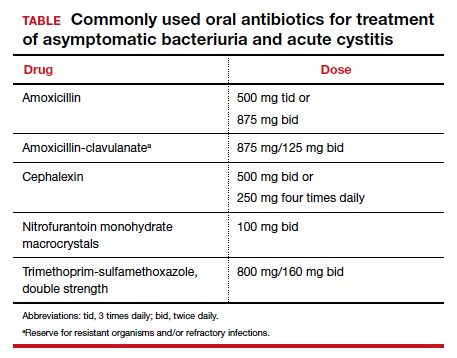

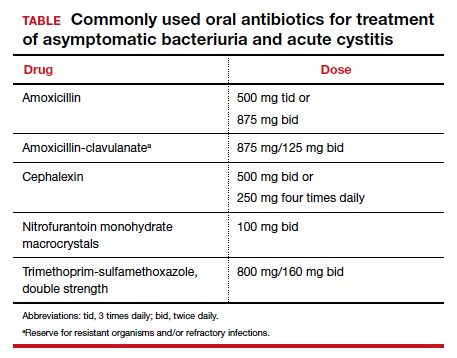

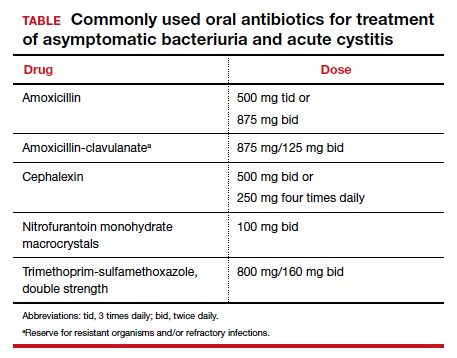

The standard criterion for the diagnosis of ASB is a urine culture that shows greater than 100,000 colonies/mL of a recognized uropathogen.1 The urine usually is obtained as a midstream, clean-catch specimen, and the test should be performed at the time of the first prenatal appointment. Once identified, ASB should be treated promptly with one of the antibiotics listed in the TABLE. Nitrofurantoin monohydrate macrocrystals (nitrofurantoin) and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole should be avoided in the first trimester unless no other drug is active against the identified microorganism.

Both have been linked to teratogenic fetal effects.5-8 The defects associated with the former drug include eye abnormalities, heart defects, and facial clefts. The abnormalities associated with the latter include neural tube defects, heart defects, choanal atresia, and diaphragmatic hernia. In the first trimester, amoxicillin and cephalexin are reasonable choices for treatment. As a general rule, a 3-day course of antibiotics will be effective for eradicating the initial episode of ASB. For recurrent infections, a 7- to 10-day course is indicated.1,3,4

Acute cystitis

The microbiology of acute cystitis essentially is identical to that of asymptomatic bacteriuria. The usual clinical manifestations include increased frequency of urination, dysuria, and urination hesitancy in association with suprapubic discomfort and a lowgrade fever.

The diagnosis can be quickly confirmed by testing the urine pH and assessing for leukocyte esterase and nitrites. If both the leukocyte esterase and nitrite test are positive, the probability of a positive urine culture is high; however, the nitrite test can be falsely negative if the urine has been incubating in the bladder for only a short period of time or if a Gram-positive organism is responsible for the infection. The urine pH is particularly helpful if it is elevated in the range of 8. This finding strongly is associated with a Proteus infection.1,9-11

Continue to: In-out catheterization is ideal...

In-out catheterization is ideal

I recommend that the urine sample be obtained by an in-out catheterization in symptomatic patients. This technique eliminates any concern about contamination of the specimen by vaginal organisms and provides a “pure” sample for culture. When urine is obtained by this method, the criterion for a positive culture result is greater than 100 colonies/mL.3 If the urine is obtained by the midstream clean-catch method, the cutoff for a positive culture remains greater than 100,000 colonies/mL.1,3

Unless the clinician is working in a low resource environment, the culture should always be obtained even though the patient will be empirically treated prior to the culture result being available. The culture can be helpful in guiding changes in antibiotic therapy if the initial response to treatment is poor.

In the first trimester, empiric treatment should be with amoxicillin or cephalexin. Beyond the first trimester, nitrofurantoin should be the drug of choice. This antibiotic is inexpensive and well-tolerated. It has limited effect on the bowel or vaginal flora and is unlikely to cause a secondary yeast infection or diarrhea. If a Proteus infection is suspected, however, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole double strength (800 mg/ 160 mg) should be used because this organism is not susceptible to nitrofurantoin. The duration of therapy should be a minimum of 3 days with the first infection and 7 to 10 days with recurrent infections.1,3,4

Acute pyelonephritis

Pyelonephritis may develop de novo or may result from inadequate treatment of lower urinary tract infection. The right kidney is affected in approximately 75% of cases because the right ureter is more subject to compression by the gravid uterus. The principal pathogen is E coli, although Klebsiella pneumoniae and Proteus species also are of importance. Other aerobic Gram-negative bacilli, such as Pseudomonas and Serratia species, are much less common unless the patient is immunosuppressed or has an indwelling catheter.1

The characteristic clinical manifestations of acute pyelonephritis are high fever (>39 °C), shaking chills, nausea and vomiting, and flank pain and tenderness. Increased frequency of urination and dysuria also may be present. In addition, pyelonephritis may be accompanied by preterm labor, sepsis, and acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). The diagnosis is established by clinical findings, urinalysis, and urine culture. The urine specimen should be obtained by an in-out catheterization, analyzed initially by dipstick for nitrites and leukocyte esterase, and submitted for culture and sensitivity. Blood cultures should be obtained, and chest radiography should be performed if ARDS is suspected.

Empiric treatment should be started as soon as these initial diagnostic tests are completed. Many women in the first 20 weeks of pregnancy will not be seriously ill and may be treated as outpatients. I recommend an initial dose of intramuscular ceftriaxone 2 g followed by oral amoxicillin-clavulanate (875 mg twice daily) for a total of 10 days. If the patient is allergic to beta-lactam antibiotics, oral trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole double strength (800 mg/160 mg) twice daily would be an excellent alternative.1,12

Treating seriously ill patients

Patients who are more seriously ill, particularly in the second half of pregnancy when preterm labor is more likely, should be hospitalized for supportive care (intravenous [IV] fluids, antipyretics, anti-emetics) and treatment with parenteral antibiotics.1,12 At our medical center, IV ceftriaxone (2 g every 24 hours), is the agent of choice. It has a convenient dosing schedule and covers almost all of the potential uropathogens. If an unusually drug-resistant organism is suspected, gentamicin or aztreonam can be combined with ceftriaxone to ensure complete coverage (see dosage recommendations below).

If the patient is allergic to beta-lactam antibiotics, alternative IV agents include:

- trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (8–10 mg/kg/d in 2 divided doses)

- gentamicin (5 mg/kg of ideal body weight every 24 hours)

- aztreonam (2 g every 8 hours)

Parenteral antibiotics should be administered until the patient has been afebrile and asymptomatic for 24 hours. At this point, oral antibiotics, based on sensitivity testing, can be started, and the patient can be discharged to complete a 10-day course of therapy.

Continue to: Treatment failure...

Treatment failure

Obstetric patients with pyelonephritis usually respond promptly to antibiotics. More than 75% will be afebrile within 48 hours, and more than 90% will be afebrile within 72 hours. When patients fail to respond promptly, 2 major causes should be considered. The first is antibiotic resistance, and this problem can be corrected on the basis of the sensitivity studies. The second is ureteral obstruction, secondary either to the effect of the gravid uterus or a urinary stone. If obstruction is suspected, renal ultrasonography should be performed. Depending upon the cause of the obstruction, a procedure such as a percutaneous nephrostomy or cystoscopic removal of the stone may be necessary.

Recurrence is possible. Following an initial episode of pyelonephritis, approximately 20% of patients will experience a recurrent lower or upper tract infection.1 Because of this recurrence rate, I recommend that these patients receive suppressive doses of antibiotics for the remainder of pregnancy. An ideal agent for suppression is nitrofurantoin (100 mg at bedtime). An alternative agent is trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole double strength (800 mg/160 mg) once daily. Amoxicillin and cephalexin are less desirable for prophylaxis because of their adverse effects on vaginal and bowel flora and their propensity for precipitating yeast infection and/or diarrhea.

CASE Resolved

The most likely diagnosis in this patient is acute cystitis. An in-out catheterization should be performed to obtain an uncontaminated urine specimen. A portion of the specimen should be forwarded to the laboratory for urine culture and sensitivity. Another portion should be used for assessment by dipstick. If the nitrite and leukocyte tests are positive, the diagnosis of acute cystitis is confirmed. Since this infection is the patient’s first episode, a reasonable antibiotic regimen would be oral nitrofurantoin (100 mg twice daily) for 3 days. The course should be extended to 7 days if symptoms persist at the end of 3 days. ●

- Duff P. Maternal and fetal infections. In: Resnik R, Lockwood CJ, Moore TR, et al, eds. Creasy & Resnik’s Maternal-Fetal Medicine: Principles and Practice. 8th ed. Elsevier; 2019:862- 919.

- St Cyr S, Barbee L, Workowski KA, et al. Update to CDC’s Treatment Guidelines for Gonococcal Infection, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:1911-1916.

- Hooton TM. Uncomplicated urinary tract infection. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1028-1037.

- Finn SD. Acute uncomplicated urinary tract infection in women. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:259-266.

- Crider KS, Cleves MA, Reefhuis J, et al. Antibacterial medication use during pregnancy and risk of birth defects. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2009;163:978-985.

- Ailes EC, Gilboa SM, Gill SK, et al. Association between antibiotic use among pregnant women with urinary tract infections in the first trimester and birth defects, National Birth Defects Prevention Study 1997 to 2011. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol. 2016;106:940-949.

- ACOG Committee Opinion No. 717 summary: sulfonamides, nitrofurantoin, and risk of birth defects. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:666-667.

- Duff P. Which antibiotics should be used with caution in pregnant women with UTI? OBG Manag. 2018;30:14-17.

- Hooton TM, Roberts PL, Cox ME, et al. Voided midstream urine culture and acute cystitis in premenopausal women. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:1883-1891.

- Mignini L, Carroli G, Abalos E, et al. Accuracy of diagnostic tests to detect asymptomatic bacteriuria during pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;113:346-352.

- Schneeberger C, van den Heuvel ER, Erwich JJHM, et al. Contamination rates of three urine-sampling methods to assess bacteriuria in pregnant women. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;121:299-305.

- Duff P. Antibiotic selection in obstetrics: making cost-effective choices. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2002;45:59-72.

CASE Pregnant woman with dysuria and suprapubic pain

A 25-year-old primigravid woman at 18 weeks of gestation requests evaluation because of the acute onset of frequent urination, dysuria, urination hesitancy, and suprapubic pain on the morning following intercourse. She has not experienced similar symptoms in the past. On physical examination, her temperature is 38 °C, pulse is 96 beats per minute, respirations are 18 per minute, and blood pressure is 100/76 mm Hg. She has no urethral discharge but is tender to palpation in the suprapubic area.

- What is the most likely diagnosis?

- What tests would be of greatest value in confirming the diagnosis?

- What is the most appropriate treatment for this patient?

Meet our perpetrator

Urinary tract infections (UTIs) are among the most common infections that occur during pregnancy. They may take one of 4 forms: acute urethritis, asymptomatic bacteriuria, acute cystitis, and acute pyelonephritis.1 The first 3 conditions usually are straightforward to diagnose and treat, and they usually do not cause major problems for the mother or fetus. The latter, however, can cause serious complications that pose risk to the mother and fetus.

This article will review the microbiology, clinical manifestations, diagnosis, and treatment of these 4 disorders in pregnancy. Particular emphasis will be placed on measures to avoid adverse effects on the mother and fetus from antimicrobial agents.

Acute urethritis

Acute urethritis can be caused by low concentrations of coliform organisms in the lower urinary tract, but it usually is secondary to infection by Neisseria gonorrhea or Chlamydia trachomatis. In most prenatal populations, the prevalence of one or the other of these 2 infections is approximately 5%.1

The most common clinical manifestations of acute urethritis are a purulent urethral discharge, increased frequency of urination, dysuria, and urination hesitancy. The diagnosis most easily is confirmed by obtaining a specimen of urethral discharge or urine and evaluating the sample by a nucleic acid amplification test for both gonorrhea and chlamydia.

Antibiotic therapy is preferred. The current recommended treatment for gonococcal urethritis is a single intramuscular injection of ceftriaxone 500 mg. If the patient prefers oral therapy, she can receive cefixime 800 mg in a single dose. For patients with an allergy to beta-lactam antibiotics, the alternative regimen is gentamicin 240 mg in a single intramuscular injection, combined with oral azithromycin in a single 2,000-mg dose. For treatment of chlamydia in pregnancy, the recommended therapy is azithromycin 1,000 mg in a single oral dose.2 A test of cure should be performed within 4 weeks of treatment.

Asymptomatic bacteriuria

Asymptomatic bacteriuria (ASB) is the most common UTI in women. Approximately 5% to 8% of all sexually active women have ASB. The condition is not unique to pregnancy; it is associated primarily with the assumption of coital activity. In point of fact, the ASB typically precedes pregnancy by several years.1

The principal pathogens responsible for ASB are shown in the FIGURE. Over 80% of first-time infections are secondary to Escherichia coli. As more recurrent episodes occur, the other Gram-negative bacilli (ie, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Proteus species) become more prevalent. The 3 major Gram-positive cocci that cause UTIs are enterococci, Staphylococcus saprophyticus, and group B streptococci.1,3,4

In nonpregnant women, ASB usually remains completely asymptomatic, and ascending infections only rarely occur. In pregnancy, however, urinary stasis is present due to the effects of progesterone on ureteral peristalsis and because of pressure on the ureters (particularly the right) by the expanding gravid uterus. As a result, ascending infection may occur in approximately 20% of patients if the lower tract infection is not identified and treated adequately.1

Clean-catch specimens and treatment

The standard criterion for the diagnosis of ASB is a urine culture that shows greater than 100,000 colonies/mL of a recognized uropathogen.1 The urine usually is obtained as a midstream, clean-catch specimen, and the test should be performed at the time of the first prenatal appointment. Once identified, ASB should be treated promptly with one of the antibiotics listed in the TABLE. Nitrofurantoin monohydrate macrocrystals (nitrofurantoin) and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole should be avoided in the first trimester unless no other drug is active against the identified microorganism.

Both have been linked to teratogenic fetal effects.5-8 The defects associated with the former drug include eye abnormalities, heart defects, and facial clefts. The abnormalities associated with the latter include neural tube defects, heart defects, choanal atresia, and diaphragmatic hernia. In the first trimester, amoxicillin and cephalexin are reasonable choices for treatment. As a general rule, a 3-day course of antibiotics will be effective for eradicating the initial episode of ASB. For recurrent infections, a 7- to 10-day course is indicated.1,3,4

Acute cystitis

The microbiology of acute cystitis essentially is identical to that of asymptomatic bacteriuria. The usual clinical manifestations include increased frequency of urination, dysuria, and urination hesitancy in association with suprapubic discomfort and a lowgrade fever.

The diagnosis can be quickly confirmed by testing the urine pH and assessing for leukocyte esterase and nitrites. If both the leukocyte esterase and nitrite test are positive, the probability of a positive urine culture is high; however, the nitrite test can be falsely negative if the urine has been incubating in the bladder for only a short period of time or if a Gram-positive organism is responsible for the infection. The urine pH is particularly helpful if it is elevated in the range of 8. This finding strongly is associated with a Proteus infection.1,9-11

Continue to: In-out catheterization is ideal...

In-out catheterization is ideal

I recommend that the urine sample be obtained by an in-out catheterization in symptomatic patients. This technique eliminates any concern about contamination of the specimen by vaginal organisms and provides a “pure” sample for culture. When urine is obtained by this method, the criterion for a positive culture result is greater than 100 colonies/mL.3 If the urine is obtained by the midstream clean-catch method, the cutoff for a positive culture remains greater than 100,000 colonies/mL.1,3

Unless the clinician is working in a low resource environment, the culture should always be obtained even though the patient will be empirically treated prior to the culture result being available. The culture can be helpful in guiding changes in antibiotic therapy if the initial response to treatment is poor.

In the first trimester, empiric treatment should be with amoxicillin or cephalexin. Beyond the first trimester, nitrofurantoin should be the drug of choice. This antibiotic is inexpensive and well-tolerated. It has limited effect on the bowel or vaginal flora and is unlikely to cause a secondary yeast infection or diarrhea. If a Proteus infection is suspected, however, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole double strength (800 mg/ 160 mg) should be used because this organism is not susceptible to nitrofurantoin. The duration of therapy should be a minimum of 3 days with the first infection and 7 to 10 days with recurrent infections.1,3,4

Acute pyelonephritis

Pyelonephritis may develop de novo or may result from inadequate treatment of lower urinary tract infection. The right kidney is affected in approximately 75% of cases because the right ureter is more subject to compression by the gravid uterus. The principal pathogen is E coli, although Klebsiella pneumoniae and Proteus species also are of importance. Other aerobic Gram-negative bacilli, such as Pseudomonas and Serratia species, are much less common unless the patient is immunosuppressed or has an indwelling catheter.1

The characteristic clinical manifestations of acute pyelonephritis are high fever (>39 °C), shaking chills, nausea and vomiting, and flank pain and tenderness. Increased frequency of urination and dysuria also may be present. In addition, pyelonephritis may be accompanied by preterm labor, sepsis, and acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). The diagnosis is established by clinical findings, urinalysis, and urine culture. The urine specimen should be obtained by an in-out catheterization, analyzed initially by dipstick for nitrites and leukocyte esterase, and submitted for culture and sensitivity. Blood cultures should be obtained, and chest radiography should be performed if ARDS is suspected.

Empiric treatment should be started as soon as these initial diagnostic tests are completed. Many women in the first 20 weeks of pregnancy will not be seriously ill and may be treated as outpatients. I recommend an initial dose of intramuscular ceftriaxone 2 g followed by oral amoxicillin-clavulanate (875 mg twice daily) for a total of 10 days. If the patient is allergic to beta-lactam antibiotics, oral trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole double strength (800 mg/160 mg) twice daily would be an excellent alternative.1,12

Treating seriously ill patients

Patients who are more seriously ill, particularly in the second half of pregnancy when preterm labor is more likely, should be hospitalized for supportive care (intravenous [IV] fluids, antipyretics, anti-emetics) and treatment with parenteral antibiotics.1,12 At our medical center, IV ceftriaxone (2 g every 24 hours), is the agent of choice. It has a convenient dosing schedule and covers almost all of the potential uropathogens. If an unusually drug-resistant organism is suspected, gentamicin or aztreonam can be combined with ceftriaxone to ensure complete coverage (see dosage recommendations below).

If the patient is allergic to beta-lactam antibiotics, alternative IV agents include:

- trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (8–10 mg/kg/d in 2 divided doses)

- gentamicin (5 mg/kg of ideal body weight every 24 hours)

- aztreonam (2 g every 8 hours)

Parenteral antibiotics should be administered until the patient has been afebrile and asymptomatic for 24 hours. At this point, oral antibiotics, based on sensitivity testing, can be started, and the patient can be discharged to complete a 10-day course of therapy.

Continue to: Treatment failure...

Treatment failure

Obstetric patients with pyelonephritis usually respond promptly to antibiotics. More than 75% will be afebrile within 48 hours, and more than 90% will be afebrile within 72 hours. When patients fail to respond promptly, 2 major causes should be considered. The first is antibiotic resistance, and this problem can be corrected on the basis of the sensitivity studies. The second is ureteral obstruction, secondary either to the effect of the gravid uterus or a urinary stone. If obstruction is suspected, renal ultrasonography should be performed. Depending upon the cause of the obstruction, a procedure such as a percutaneous nephrostomy or cystoscopic removal of the stone may be necessary.

Recurrence is possible. Following an initial episode of pyelonephritis, approximately 20% of patients will experience a recurrent lower or upper tract infection.1 Because of this recurrence rate, I recommend that these patients receive suppressive doses of antibiotics for the remainder of pregnancy. An ideal agent for suppression is nitrofurantoin (100 mg at bedtime). An alternative agent is trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole double strength (800 mg/160 mg) once daily. Amoxicillin and cephalexin are less desirable for prophylaxis because of their adverse effects on vaginal and bowel flora and their propensity for precipitating yeast infection and/or diarrhea.

CASE Resolved

The most likely diagnosis in this patient is acute cystitis. An in-out catheterization should be performed to obtain an uncontaminated urine specimen. A portion of the specimen should be forwarded to the laboratory for urine culture and sensitivity. Another portion should be used for assessment by dipstick. If the nitrite and leukocyte tests are positive, the diagnosis of acute cystitis is confirmed. Since this infection is the patient’s first episode, a reasonable antibiotic regimen would be oral nitrofurantoin (100 mg twice daily) for 3 days. The course should be extended to 7 days if symptoms persist at the end of 3 days. ●

CASE Pregnant woman with dysuria and suprapubic pain

A 25-year-old primigravid woman at 18 weeks of gestation requests evaluation because of the acute onset of frequent urination, dysuria, urination hesitancy, and suprapubic pain on the morning following intercourse. She has not experienced similar symptoms in the past. On physical examination, her temperature is 38 °C, pulse is 96 beats per minute, respirations are 18 per minute, and blood pressure is 100/76 mm Hg. She has no urethral discharge but is tender to palpation in the suprapubic area.

- What is the most likely diagnosis?

- What tests would be of greatest value in confirming the diagnosis?

- What is the most appropriate treatment for this patient?

Meet our perpetrator

Urinary tract infections (UTIs) are among the most common infections that occur during pregnancy. They may take one of 4 forms: acute urethritis, asymptomatic bacteriuria, acute cystitis, and acute pyelonephritis.1 The first 3 conditions usually are straightforward to diagnose and treat, and they usually do not cause major problems for the mother or fetus. The latter, however, can cause serious complications that pose risk to the mother and fetus.

This article will review the microbiology, clinical manifestations, diagnosis, and treatment of these 4 disorders in pregnancy. Particular emphasis will be placed on measures to avoid adverse effects on the mother and fetus from antimicrobial agents.

Acute urethritis

Acute urethritis can be caused by low concentrations of coliform organisms in the lower urinary tract, but it usually is secondary to infection by Neisseria gonorrhea or Chlamydia trachomatis. In most prenatal populations, the prevalence of one or the other of these 2 infections is approximately 5%.1

The most common clinical manifestations of acute urethritis are a purulent urethral discharge, increased frequency of urination, dysuria, and urination hesitancy. The diagnosis most easily is confirmed by obtaining a specimen of urethral discharge or urine and evaluating the sample by a nucleic acid amplification test for both gonorrhea and chlamydia.

Antibiotic therapy is preferred. The current recommended treatment for gonococcal urethritis is a single intramuscular injection of ceftriaxone 500 mg. If the patient prefers oral therapy, she can receive cefixime 800 mg in a single dose. For patients with an allergy to beta-lactam antibiotics, the alternative regimen is gentamicin 240 mg in a single intramuscular injection, combined with oral azithromycin in a single 2,000-mg dose. For treatment of chlamydia in pregnancy, the recommended therapy is azithromycin 1,000 mg in a single oral dose.2 A test of cure should be performed within 4 weeks of treatment.

Asymptomatic bacteriuria

Asymptomatic bacteriuria (ASB) is the most common UTI in women. Approximately 5% to 8% of all sexually active women have ASB. The condition is not unique to pregnancy; it is associated primarily with the assumption of coital activity. In point of fact, the ASB typically precedes pregnancy by several years.1

The principal pathogens responsible for ASB are shown in the FIGURE. Over 80% of first-time infections are secondary to Escherichia coli. As more recurrent episodes occur, the other Gram-negative bacilli (ie, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Proteus species) become more prevalent. The 3 major Gram-positive cocci that cause UTIs are enterococci, Staphylococcus saprophyticus, and group B streptococci.1,3,4

In nonpregnant women, ASB usually remains completely asymptomatic, and ascending infections only rarely occur. In pregnancy, however, urinary stasis is present due to the effects of progesterone on ureteral peristalsis and because of pressure on the ureters (particularly the right) by the expanding gravid uterus. As a result, ascending infection may occur in approximately 20% of patients if the lower tract infection is not identified and treated adequately.1

Clean-catch specimens and treatment

The standard criterion for the diagnosis of ASB is a urine culture that shows greater than 100,000 colonies/mL of a recognized uropathogen.1 The urine usually is obtained as a midstream, clean-catch specimen, and the test should be performed at the time of the first prenatal appointment. Once identified, ASB should be treated promptly with one of the antibiotics listed in the TABLE. Nitrofurantoin monohydrate macrocrystals (nitrofurantoin) and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole should be avoided in the first trimester unless no other drug is active against the identified microorganism.

Both have been linked to teratogenic fetal effects.5-8 The defects associated with the former drug include eye abnormalities, heart defects, and facial clefts. The abnormalities associated with the latter include neural tube defects, heart defects, choanal atresia, and diaphragmatic hernia. In the first trimester, amoxicillin and cephalexin are reasonable choices for treatment. As a general rule, a 3-day course of antibiotics will be effective for eradicating the initial episode of ASB. For recurrent infections, a 7- to 10-day course is indicated.1,3,4

Acute cystitis

The microbiology of acute cystitis essentially is identical to that of asymptomatic bacteriuria. The usual clinical manifestations include increased frequency of urination, dysuria, and urination hesitancy in association with suprapubic discomfort and a lowgrade fever.

The diagnosis can be quickly confirmed by testing the urine pH and assessing for leukocyte esterase and nitrites. If both the leukocyte esterase and nitrite test are positive, the probability of a positive urine culture is high; however, the nitrite test can be falsely negative if the urine has been incubating in the bladder for only a short period of time or if a Gram-positive organism is responsible for the infection. The urine pH is particularly helpful if it is elevated in the range of 8. This finding strongly is associated with a Proteus infection.1,9-11

Continue to: In-out catheterization is ideal...

In-out catheterization is ideal

I recommend that the urine sample be obtained by an in-out catheterization in symptomatic patients. This technique eliminates any concern about contamination of the specimen by vaginal organisms and provides a “pure” sample for culture. When urine is obtained by this method, the criterion for a positive culture result is greater than 100 colonies/mL.3 If the urine is obtained by the midstream clean-catch method, the cutoff for a positive culture remains greater than 100,000 colonies/mL.1,3

Unless the clinician is working in a low resource environment, the culture should always be obtained even though the patient will be empirically treated prior to the culture result being available. The culture can be helpful in guiding changes in antibiotic therapy if the initial response to treatment is poor.

In the first trimester, empiric treatment should be with amoxicillin or cephalexin. Beyond the first trimester, nitrofurantoin should be the drug of choice. This antibiotic is inexpensive and well-tolerated. It has limited effect on the bowel or vaginal flora and is unlikely to cause a secondary yeast infection or diarrhea. If a Proteus infection is suspected, however, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole double strength (800 mg/ 160 mg) should be used because this organism is not susceptible to nitrofurantoin. The duration of therapy should be a minimum of 3 days with the first infection and 7 to 10 days with recurrent infections.1,3,4

Acute pyelonephritis

Pyelonephritis may develop de novo or may result from inadequate treatment of lower urinary tract infection. The right kidney is affected in approximately 75% of cases because the right ureter is more subject to compression by the gravid uterus. The principal pathogen is E coli, although Klebsiella pneumoniae and Proteus species also are of importance. Other aerobic Gram-negative bacilli, such as Pseudomonas and Serratia species, are much less common unless the patient is immunosuppressed or has an indwelling catheter.1

The characteristic clinical manifestations of acute pyelonephritis are high fever (>39 °C), shaking chills, nausea and vomiting, and flank pain and tenderness. Increased frequency of urination and dysuria also may be present. In addition, pyelonephritis may be accompanied by preterm labor, sepsis, and acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). The diagnosis is established by clinical findings, urinalysis, and urine culture. The urine specimen should be obtained by an in-out catheterization, analyzed initially by dipstick for nitrites and leukocyte esterase, and submitted for culture and sensitivity. Blood cultures should be obtained, and chest radiography should be performed if ARDS is suspected.

Empiric treatment should be started as soon as these initial diagnostic tests are completed. Many women in the first 20 weeks of pregnancy will not be seriously ill and may be treated as outpatients. I recommend an initial dose of intramuscular ceftriaxone 2 g followed by oral amoxicillin-clavulanate (875 mg twice daily) for a total of 10 days. If the patient is allergic to beta-lactam antibiotics, oral trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole double strength (800 mg/160 mg) twice daily would be an excellent alternative.1,12

Treating seriously ill patients

Patients who are more seriously ill, particularly in the second half of pregnancy when preterm labor is more likely, should be hospitalized for supportive care (intravenous [IV] fluids, antipyretics, anti-emetics) and treatment with parenteral antibiotics.1,12 At our medical center, IV ceftriaxone (2 g every 24 hours), is the agent of choice. It has a convenient dosing schedule and covers almost all of the potential uropathogens. If an unusually drug-resistant organism is suspected, gentamicin or aztreonam can be combined with ceftriaxone to ensure complete coverage (see dosage recommendations below).

If the patient is allergic to beta-lactam antibiotics, alternative IV agents include:

- trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (8–10 mg/kg/d in 2 divided doses)

- gentamicin (5 mg/kg of ideal body weight every 24 hours)

- aztreonam (2 g every 8 hours)

Parenteral antibiotics should be administered until the patient has been afebrile and asymptomatic for 24 hours. At this point, oral antibiotics, based on sensitivity testing, can be started, and the patient can be discharged to complete a 10-day course of therapy.

Continue to: Treatment failure...

Treatment failure

Obstetric patients with pyelonephritis usually respond promptly to antibiotics. More than 75% will be afebrile within 48 hours, and more than 90% will be afebrile within 72 hours. When patients fail to respond promptly, 2 major causes should be considered. The first is antibiotic resistance, and this problem can be corrected on the basis of the sensitivity studies. The second is ureteral obstruction, secondary either to the effect of the gravid uterus or a urinary stone. If obstruction is suspected, renal ultrasonography should be performed. Depending upon the cause of the obstruction, a procedure such as a percutaneous nephrostomy or cystoscopic removal of the stone may be necessary.

Recurrence is possible. Following an initial episode of pyelonephritis, approximately 20% of patients will experience a recurrent lower or upper tract infection.1 Because of this recurrence rate, I recommend that these patients receive suppressive doses of antibiotics for the remainder of pregnancy. An ideal agent for suppression is nitrofurantoin (100 mg at bedtime). An alternative agent is trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole double strength (800 mg/160 mg) once daily. Amoxicillin and cephalexin are less desirable for prophylaxis because of their adverse effects on vaginal and bowel flora and their propensity for precipitating yeast infection and/or diarrhea.

CASE Resolved

The most likely diagnosis in this patient is acute cystitis. An in-out catheterization should be performed to obtain an uncontaminated urine specimen. A portion of the specimen should be forwarded to the laboratory for urine culture and sensitivity. Another portion should be used for assessment by dipstick. If the nitrite and leukocyte tests are positive, the diagnosis of acute cystitis is confirmed. Since this infection is the patient’s first episode, a reasonable antibiotic regimen would be oral nitrofurantoin (100 mg twice daily) for 3 days. The course should be extended to 7 days if symptoms persist at the end of 3 days. ●

- Duff P. Maternal and fetal infections. In: Resnik R, Lockwood CJ, Moore TR, et al, eds. Creasy & Resnik’s Maternal-Fetal Medicine: Principles and Practice. 8th ed. Elsevier; 2019:862- 919.

- St Cyr S, Barbee L, Workowski KA, et al. Update to CDC’s Treatment Guidelines for Gonococcal Infection, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:1911-1916.

- Hooton TM. Uncomplicated urinary tract infection. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1028-1037.

- Finn SD. Acute uncomplicated urinary tract infection in women. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:259-266.

- Crider KS, Cleves MA, Reefhuis J, et al. Antibacterial medication use during pregnancy and risk of birth defects. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2009;163:978-985.

- Ailes EC, Gilboa SM, Gill SK, et al. Association between antibiotic use among pregnant women with urinary tract infections in the first trimester and birth defects, National Birth Defects Prevention Study 1997 to 2011. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol. 2016;106:940-949.

- ACOG Committee Opinion No. 717 summary: sulfonamides, nitrofurantoin, and risk of birth defects. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:666-667.

- Duff P. Which antibiotics should be used with caution in pregnant women with UTI? OBG Manag. 2018;30:14-17.

- Hooton TM, Roberts PL, Cox ME, et al. Voided midstream urine culture and acute cystitis in premenopausal women. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:1883-1891.

- Mignini L, Carroli G, Abalos E, et al. Accuracy of diagnostic tests to detect asymptomatic bacteriuria during pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;113:346-352.

- Schneeberger C, van den Heuvel ER, Erwich JJHM, et al. Contamination rates of three urine-sampling methods to assess bacteriuria in pregnant women. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;121:299-305.

- Duff P. Antibiotic selection in obstetrics: making cost-effective choices. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2002;45:59-72.

- Duff P. Maternal and fetal infections. In: Resnik R, Lockwood CJ, Moore TR, et al, eds. Creasy & Resnik’s Maternal-Fetal Medicine: Principles and Practice. 8th ed. Elsevier; 2019:862- 919.

- St Cyr S, Barbee L, Workowski KA, et al. Update to CDC’s Treatment Guidelines for Gonococcal Infection, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:1911-1916.

- Hooton TM. Uncomplicated urinary tract infection. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1028-1037.

- Finn SD. Acute uncomplicated urinary tract infection in women. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:259-266.

- Crider KS, Cleves MA, Reefhuis J, et al. Antibacterial medication use during pregnancy and risk of birth defects. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2009;163:978-985.

- Ailes EC, Gilboa SM, Gill SK, et al. Association between antibiotic use among pregnant women with urinary tract infections in the first trimester and birth defects, National Birth Defects Prevention Study 1997 to 2011. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol. 2016;106:940-949.

- ACOG Committee Opinion No. 717 summary: sulfonamides, nitrofurantoin, and risk of birth defects. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:666-667.

- Duff P. Which antibiotics should be used with caution in pregnant women with UTI? OBG Manag. 2018;30:14-17.

- Hooton TM, Roberts PL, Cox ME, et al. Voided midstream urine culture and acute cystitis in premenopausal women. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:1883-1891.

- Mignini L, Carroli G, Abalos E, et al. Accuracy of diagnostic tests to detect asymptomatic bacteriuria during pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;113:346-352.

- Schneeberger C, van den Heuvel ER, Erwich JJHM, et al. Contamination rates of three urine-sampling methods to assess bacteriuria in pregnant women. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;121:299-305.

- Duff P. Antibiotic selection in obstetrics: making cost-effective choices. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2002;45:59-72.

Infectious disease pop quiz: Clinical challenge #9 for the ObGyn

For uncomplicated chlamydia infection in a pregnant woman, what is the most appropriate treatment?

Continue to the answer...

Uncomplicated chlamydia infection in a pregnant woman should be treated with a single 1,000-mg oral dose of azithromycin. An acceptable alternative is amoxicillin 500 mg orally 3 times daily for 7 days.

In a nonpregnant patient, doxycycline 100 mg orally twice daily for 7 days is also an appropriate alternative. However, doxycycline is relatively expensive and may not be well tolerated because of gastrointestinal adverse effects. (Workowski KA, Bolan GA. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2015. MMWR Morbid Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64[RR3]:1-137.)

- Duff P. Maternal and perinatal infections: bacterial. In: Landon MB, Galan HL, Jauniaux ERM, et al. Gabbe’s Obstetrics: Normal and Problem Pregnancies. 8th ed. Elsevier; 2021:1124-1146.

- Duff P. Maternal and fetal infections. In: Resnik R, Lockwood CJ, Moore TJ, et al. Creasy & Resnik’s Maternal-Fetal Medicine: Principles and Practice. 8th ed. Elsevier; 2019:862-919.

For uncomplicated chlamydia infection in a pregnant woman, what is the most appropriate treatment?

Continue to the answer...

Uncomplicated chlamydia infection in a pregnant woman should be treated with a single 1,000-mg oral dose of azithromycin. An acceptable alternative is amoxicillin 500 mg orally 3 times daily for 7 days.

In a nonpregnant patient, doxycycline 100 mg orally twice daily for 7 days is also an appropriate alternative. However, doxycycline is relatively expensive and may not be well tolerated because of gastrointestinal adverse effects. (Workowski KA, Bolan GA. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2015. MMWR Morbid Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64[RR3]:1-137.)

For uncomplicated chlamydia infection in a pregnant woman, what is the most appropriate treatment?

Continue to the answer...

Uncomplicated chlamydia infection in a pregnant woman should be treated with a single 1,000-mg oral dose of azithromycin. An acceptable alternative is amoxicillin 500 mg orally 3 times daily for 7 days.

In a nonpregnant patient, doxycycline 100 mg orally twice daily for 7 days is also an appropriate alternative. However, doxycycline is relatively expensive and may not be well tolerated because of gastrointestinal adverse effects. (Workowski KA, Bolan GA. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2015. MMWR Morbid Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64[RR3]:1-137.)

- Duff P. Maternal and perinatal infections: bacterial. In: Landon MB, Galan HL, Jauniaux ERM, et al. Gabbe’s Obstetrics: Normal and Problem Pregnancies. 8th ed. Elsevier; 2021:1124-1146.

- Duff P. Maternal and fetal infections. In: Resnik R, Lockwood CJ, Moore TJ, et al. Creasy & Resnik’s Maternal-Fetal Medicine: Principles and Practice. 8th ed. Elsevier; 2019:862-919.

- Duff P. Maternal and perinatal infections: bacterial. In: Landon MB, Galan HL, Jauniaux ERM, et al. Gabbe’s Obstetrics: Normal and Problem Pregnancies. 8th ed. Elsevier; 2021:1124-1146.

- Duff P. Maternal and fetal infections. In: Resnik R, Lockwood CJ, Moore TJ, et al. Creasy & Resnik’s Maternal-Fetal Medicine: Principles and Practice. 8th ed. Elsevier; 2019:862-919.