User login

Hidden Basal Cell Carcinoma in the Intergluteal Crease

Practice Gap

Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) is the most common cancer, and its incidence is on the rise.1 The risk of this skin cancer is increased when there is a history of squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) or BCC.2 Basal cell carcinoma often is found in sun-exposed areas, most commonly due to a history of intense sunburn.3 Other risk factors include male gender and increased age.4

Eighty percent to 85% of BCCs present on the head and neck5; however, BCC also can occur in unusual locations. When BCC presents in areas such as the perianal region, it is found to be larger than when found in more common areas,6 likely because neoplasms in this sensitive area often are overlooked. Literature on BCC of the intergluteal crease is limited.7 Being educated on the existence of BCC in this sensitive area can aid proper diagnosis.

The Technique and Case

An 83-year-old woman presented to the dermatology clinic for a suspicious lesion in the intergluteal crease that was tender to palpation with drainage. She first noticed this lesion and reported it to her primary care physician at a visit 6 months prior. The primary care physician did not pursue investigation of the lesion. One month later, the patient was seen by a gastroenterologist for the lesion and was referred to dermatology. The patient’s medical history included SCC and BCC on the face, both treated successfully with Mohs micrographic surgery.

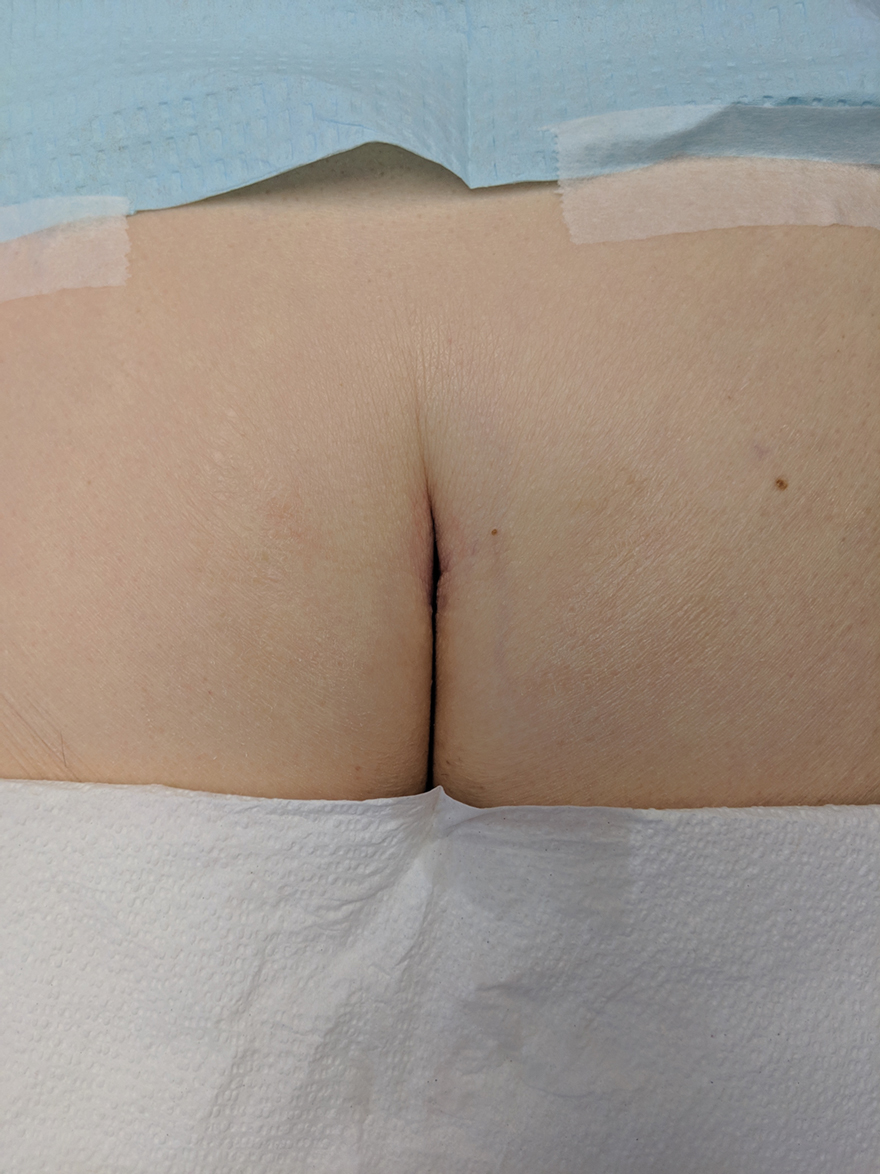

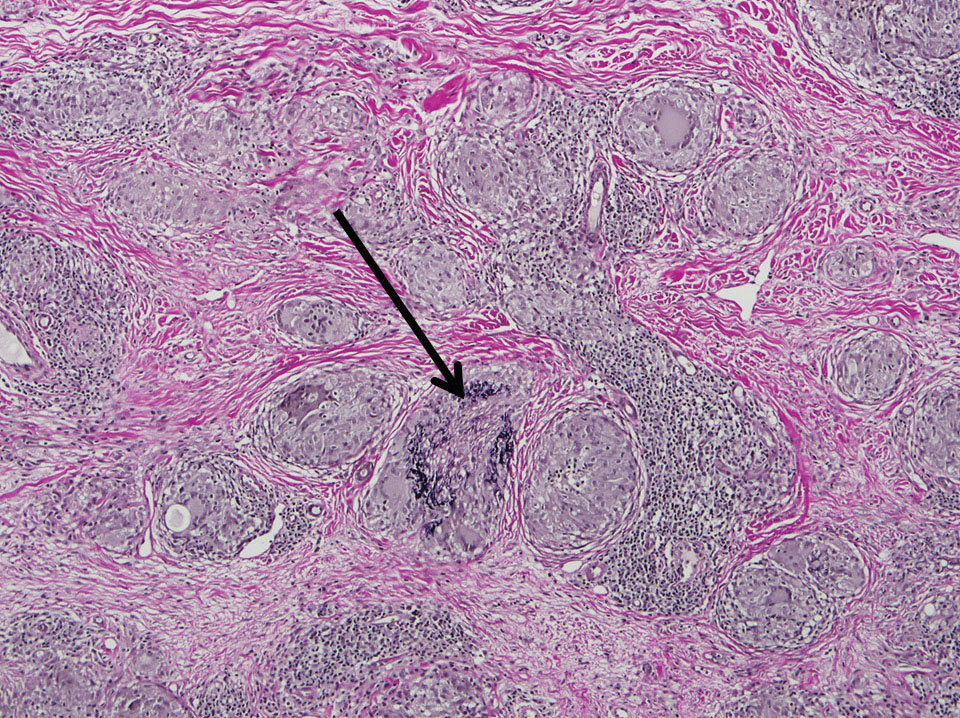

Physical examination revealed a 2.6×1.1-cm, erythematous, nodular plaque in the coccygeal area of the intergluteal crease (Figure 1). A shave biopsy disclosed BCC, nodular type, ulcerated. Microscopically, there were nodular aggregates of basaloid cells with hyperchromatic nuclei and peripheral palisading, separated from mucinous stromal surroundings by artefactual clefts.

The initial differential diagnosis for this patient’s lesion included an ulcer or SCC. Basal cell carcinoma was not suspected due to the location and appearance of the lesion. The patient was successfully treated with Mohs micrographic surgery.

Practical Implications

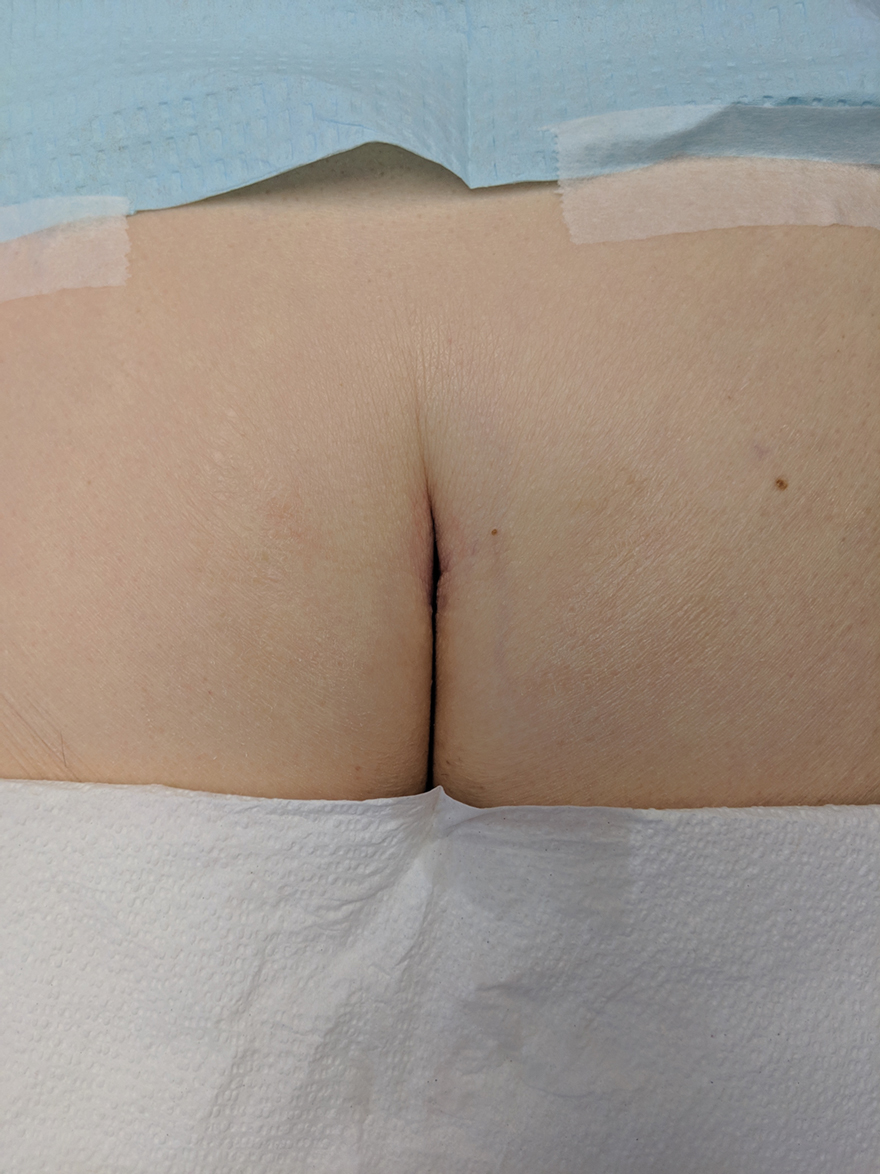

Without thorough examination, this cancerous lesion would not have been seen (Figure 2). Therefore, it is important to practice thorough physical examination skills to avoid missing these cancers, particularly when examining a patient with a history of SCC or BCC. Furthermore, biopsy is recommended for suspicious lesions to rule out BCC.

Be careful not to get caught up in epidemiological or demographic considerations when making a diagnosis of this kind or when assessing the severity of a lesion. This patient, for instance, was female, which makes her less likely to present with BCC.8 Moreover, the cancer presented in a highly unlikely location for BCC, where there had not been significant sunburn.9 Patients and physicians should be educated about the incidence of BCC in unexpected areas; without a second and close look, this BCC could have been missed.

Final Thoughts

The literature continuously demonstrates the rarity of BCC in the intergluteal crease.10 However, when perianal BCC is properly identified and treated with local excision, prognosis is good.11 Basal cell carcinoma has been seen to arise in other sensitive locations; vulvar, nipple, and scrotal BCC neoplasms are among the uncommon locations where BCC has appeared.12 These areas are frequently—and easily—ignored. A total-body skin examination should be performed to ensure that these insidious-onset carcinomas are not overlooked to protect patients from the adverse consequences of untreated cancer.13

- Roewert-Huber J, Lange-Asschenfeldt B, Stockfleth E, et al. Epidemiology and aetiology of basal cell carcinoma. Br J Dermatol. 2007;157(suppl 2):47-51.

- Rogers HW, Weinstock MA, Feldman SR, et al. Incidence estimate of nonmelanoma skin cancer (keratinocyte carcinomas) in the US population, 2012. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:1081-1086.

- Zanetti R, Rosso S, Martinez C, et al. Comparison of risk patterns in carcinoma and melanoma of the skin in men: a multi-centre case–case–control study. Br J Cancer. 2006;94:743-751.

- Marzuka AG, Book SE. Basal cell carcinoma: pathogenesis, epidemiology, clinical features, diagnosis, histopathology, and management. Yale J Biol Med. 2015;88:167-179.

- Lorenzini M, Gatti S, Giannitrapani A. Giant basal cell carcinoma of the thoracic wall: a case report and review of the literature. Br J Plast Surg. 2005;58:1007-1010.

- Lee HS, Kim SK. Basal cell carcinoma presenting as a perianal ulcer and treated with radiotherapy. Ann Dermatol. 2015;27:212-214.

- Salih AM, Kakamad FH, Rauf GM. Basal cell carcinoma mimicking pilonidal sinus: a case report with literature review. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2016;28:121-123.

- Scrivener Y, Grosshans E, Cribier B. Variations of basal cell carcinomas according to gender, age, location and histopathological subtype. Br J Dermatol. 2002;147:41-47.

- Park J, Cho Y-S, Song K-H, et al. Basal cell carcinoma on the pubic area: report of a case and review of 19 Korean cases of BCC from non-sun-exposed areas. Ann Dermatol. 2011;23:405-408.

- Damin DC, Rosito MA, Gus P, et al. Perianal basal cell carcinoma. J Cutan Med Surg. 2002;6:26-28.

- Paterson CA, Young-Fadok TM, Dozois RR. Basal cell carcinoma of the perianal region: 20-year experience. Dis Colon Rectum. 1999;42:1200-1202.

- Mulvany NJ, Rayoo M, Allen DG. Basal cell carcinoma of the vulva: a case series. Pathology. 2012;44:528-533.

- Leonard D, Beddy D, Dozois EJ. Neoplasms of anal canal and perianal skin. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2011;24:54-63.

Practice Gap

Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) is the most common cancer, and its incidence is on the rise.1 The risk of this skin cancer is increased when there is a history of squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) or BCC.2 Basal cell carcinoma often is found in sun-exposed areas, most commonly due to a history of intense sunburn.3 Other risk factors include male gender and increased age.4

Eighty percent to 85% of BCCs present on the head and neck5; however, BCC also can occur in unusual locations. When BCC presents in areas such as the perianal region, it is found to be larger than when found in more common areas,6 likely because neoplasms in this sensitive area often are overlooked. Literature on BCC of the intergluteal crease is limited.7 Being educated on the existence of BCC in this sensitive area can aid proper diagnosis.

The Technique and Case

An 83-year-old woman presented to the dermatology clinic for a suspicious lesion in the intergluteal crease that was tender to palpation with drainage. She first noticed this lesion and reported it to her primary care physician at a visit 6 months prior. The primary care physician did not pursue investigation of the lesion. One month later, the patient was seen by a gastroenterologist for the lesion and was referred to dermatology. The patient’s medical history included SCC and BCC on the face, both treated successfully with Mohs micrographic surgery.

Physical examination revealed a 2.6×1.1-cm, erythematous, nodular plaque in the coccygeal area of the intergluteal crease (Figure 1). A shave biopsy disclosed BCC, nodular type, ulcerated. Microscopically, there were nodular aggregates of basaloid cells with hyperchromatic nuclei and peripheral palisading, separated from mucinous stromal surroundings by artefactual clefts.

The initial differential diagnosis for this patient’s lesion included an ulcer or SCC. Basal cell carcinoma was not suspected due to the location and appearance of the lesion. The patient was successfully treated with Mohs micrographic surgery.

Practical Implications

Without thorough examination, this cancerous lesion would not have been seen (Figure 2). Therefore, it is important to practice thorough physical examination skills to avoid missing these cancers, particularly when examining a patient with a history of SCC or BCC. Furthermore, biopsy is recommended for suspicious lesions to rule out BCC.

Be careful not to get caught up in epidemiological or demographic considerations when making a diagnosis of this kind or when assessing the severity of a lesion. This patient, for instance, was female, which makes her less likely to present with BCC.8 Moreover, the cancer presented in a highly unlikely location for BCC, where there had not been significant sunburn.9 Patients and physicians should be educated about the incidence of BCC in unexpected areas; without a second and close look, this BCC could have been missed.

Final Thoughts

The literature continuously demonstrates the rarity of BCC in the intergluteal crease.10 However, when perianal BCC is properly identified and treated with local excision, prognosis is good.11 Basal cell carcinoma has been seen to arise in other sensitive locations; vulvar, nipple, and scrotal BCC neoplasms are among the uncommon locations where BCC has appeared.12 These areas are frequently—and easily—ignored. A total-body skin examination should be performed to ensure that these insidious-onset carcinomas are not overlooked to protect patients from the adverse consequences of untreated cancer.13

Practice Gap

Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) is the most common cancer, and its incidence is on the rise.1 The risk of this skin cancer is increased when there is a history of squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) or BCC.2 Basal cell carcinoma often is found in sun-exposed areas, most commonly due to a history of intense sunburn.3 Other risk factors include male gender and increased age.4

Eighty percent to 85% of BCCs present on the head and neck5; however, BCC also can occur in unusual locations. When BCC presents in areas such as the perianal region, it is found to be larger than when found in more common areas,6 likely because neoplasms in this sensitive area often are overlooked. Literature on BCC of the intergluteal crease is limited.7 Being educated on the existence of BCC in this sensitive area can aid proper diagnosis.

The Technique and Case

An 83-year-old woman presented to the dermatology clinic for a suspicious lesion in the intergluteal crease that was tender to palpation with drainage. She first noticed this lesion and reported it to her primary care physician at a visit 6 months prior. The primary care physician did not pursue investigation of the lesion. One month later, the patient was seen by a gastroenterologist for the lesion and was referred to dermatology. The patient’s medical history included SCC and BCC on the face, both treated successfully with Mohs micrographic surgery.

Physical examination revealed a 2.6×1.1-cm, erythematous, nodular plaque in the coccygeal area of the intergluteal crease (Figure 1). A shave biopsy disclosed BCC, nodular type, ulcerated. Microscopically, there were nodular aggregates of basaloid cells with hyperchromatic nuclei and peripheral palisading, separated from mucinous stromal surroundings by artefactual clefts.

The initial differential diagnosis for this patient’s lesion included an ulcer or SCC. Basal cell carcinoma was not suspected due to the location and appearance of the lesion. The patient was successfully treated with Mohs micrographic surgery.

Practical Implications

Without thorough examination, this cancerous lesion would not have been seen (Figure 2). Therefore, it is important to practice thorough physical examination skills to avoid missing these cancers, particularly when examining a patient with a history of SCC or BCC. Furthermore, biopsy is recommended for suspicious lesions to rule out BCC.

Be careful not to get caught up in epidemiological or demographic considerations when making a diagnosis of this kind or when assessing the severity of a lesion. This patient, for instance, was female, which makes her less likely to present with BCC.8 Moreover, the cancer presented in a highly unlikely location for BCC, where there had not been significant sunburn.9 Patients and physicians should be educated about the incidence of BCC in unexpected areas; without a second and close look, this BCC could have been missed.

Final Thoughts

The literature continuously demonstrates the rarity of BCC in the intergluteal crease.10 However, when perianal BCC is properly identified and treated with local excision, prognosis is good.11 Basal cell carcinoma has been seen to arise in other sensitive locations; vulvar, nipple, and scrotal BCC neoplasms are among the uncommon locations where BCC has appeared.12 These areas are frequently—and easily—ignored. A total-body skin examination should be performed to ensure that these insidious-onset carcinomas are not overlooked to protect patients from the adverse consequences of untreated cancer.13

- Roewert-Huber J, Lange-Asschenfeldt B, Stockfleth E, et al. Epidemiology and aetiology of basal cell carcinoma. Br J Dermatol. 2007;157(suppl 2):47-51.

- Rogers HW, Weinstock MA, Feldman SR, et al. Incidence estimate of nonmelanoma skin cancer (keratinocyte carcinomas) in the US population, 2012. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:1081-1086.

- Zanetti R, Rosso S, Martinez C, et al. Comparison of risk patterns in carcinoma and melanoma of the skin in men: a multi-centre case–case–control study. Br J Cancer. 2006;94:743-751.

- Marzuka AG, Book SE. Basal cell carcinoma: pathogenesis, epidemiology, clinical features, diagnosis, histopathology, and management. Yale J Biol Med. 2015;88:167-179.

- Lorenzini M, Gatti S, Giannitrapani A. Giant basal cell carcinoma of the thoracic wall: a case report and review of the literature. Br J Plast Surg. 2005;58:1007-1010.

- Lee HS, Kim SK. Basal cell carcinoma presenting as a perianal ulcer and treated with radiotherapy. Ann Dermatol. 2015;27:212-214.

- Salih AM, Kakamad FH, Rauf GM. Basal cell carcinoma mimicking pilonidal sinus: a case report with literature review. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2016;28:121-123.

- Scrivener Y, Grosshans E, Cribier B. Variations of basal cell carcinomas according to gender, age, location and histopathological subtype. Br J Dermatol. 2002;147:41-47.

- Park J, Cho Y-S, Song K-H, et al. Basal cell carcinoma on the pubic area: report of a case and review of 19 Korean cases of BCC from non-sun-exposed areas. Ann Dermatol. 2011;23:405-408.

- Damin DC, Rosito MA, Gus P, et al. Perianal basal cell carcinoma. J Cutan Med Surg. 2002;6:26-28.

- Paterson CA, Young-Fadok TM, Dozois RR. Basal cell carcinoma of the perianal region: 20-year experience. Dis Colon Rectum. 1999;42:1200-1202.

- Mulvany NJ, Rayoo M, Allen DG. Basal cell carcinoma of the vulva: a case series. Pathology. 2012;44:528-533.

- Leonard D, Beddy D, Dozois EJ. Neoplasms of anal canal and perianal skin. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2011;24:54-63.

- Roewert-Huber J, Lange-Asschenfeldt B, Stockfleth E, et al. Epidemiology and aetiology of basal cell carcinoma. Br J Dermatol. 2007;157(suppl 2):47-51.

- Rogers HW, Weinstock MA, Feldman SR, et al. Incidence estimate of nonmelanoma skin cancer (keratinocyte carcinomas) in the US population, 2012. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:1081-1086.

- Zanetti R, Rosso S, Martinez C, et al. Comparison of risk patterns in carcinoma and melanoma of the skin in men: a multi-centre case–case–control study. Br J Cancer. 2006;94:743-751.

- Marzuka AG, Book SE. Basal cell carcinoma: pathogenesis, epidemiology, clinical features, diagnosis, histopathology, and management. Yale J Biol Med. 2015;88:167-179.

- Lorenzini M, Gatti S, Giannitrapani A. Giant basal cell carcinoma of the thoracic wall: a case report and review of the literature. Br J Plast Surg. 2005;58:1007-1010.

- Lee HS, Kim SK. Basal cell carcinoma presenting as a perianal ulcer and treated with radiotherapy. Ann Dermatol. 2015;27:212-214.

- Salih AM, Kakamad FH, Rauf GM. Basal cell carcinoma mimicking pilonidal sinus: a case report with literature review. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2016;28:121-123.

- Scrivener Y, Grosshans E, Cribier B. Variations of basal cell carcinomas according to gender, age, location and histopathological subtype. Br J Dermatol. 2002;147:41-47.

- Park J, Cho Y-S, Song K-H, et al. Basal cell carcinoma on the pubic area: report of a case and review of 19 Korean cases of BCC from non-sun-exposed areas. Ann Dermatol. 2011;23:405-408.

- Damin DC, Rosito MA, Gus P, et al. Perianal basal cell carcinoma. J Cutan Med Surg. 2002;6:26-28.

- Paterson CA, Young-Fadok TM, Dozois RR. Basal cell carcinoma of the perianal region: 20-year experience. Dis Colon Rectum. 1999;42:1200-1202.

- Mulvany NJ, Rayoo M, Allen DG. Basal cell carcinoma of the vulva: a case series. Pathology. 2012;44:528-533.

- Leonard D, Beddy D, Dozois EJ. Neoplasms of anal canal and perianal skin. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2011;24:54-63.

Annular Elastolytic Giant Cell Granuloma: Mysterious Enlarging Scarring Lesions

To the Editor:

A 52-year-old woman with a medical history of migraines and cervicalgia presented with lesions on the right arm, back, and right calf. The patient stated that the lesions began as small papules that had grown over 13 months, with the largest papule on the right forearm. She reported no itching, bleeding, pain, discharge, or other symptoms associated with the lesions. She had a multiple-year history of similar lesions that did not respond to treatment with antifungals, moderate-potency steroids, and other over-the-counter creams. The lesions would resolve spontaneously with scarring and subsequently recur. Prior skin biopsies were inconclusive. The patient did not report any systemic symptoms or a personal or family history of connective tissue diseases.

Physical examination revealed a 4-cm asymmetric, annular, erythematous plaque with central clearing on the right dorsal forearm with defined margins except over the distal aspect (Figure 1). She also had several 1- to 2-cm erythematous, nummular, asymmetric plaques on the right upper arm with well-defined margins. She had several lesions over the central and left sides of the upper back that were similar to the lesions on the upper arm.

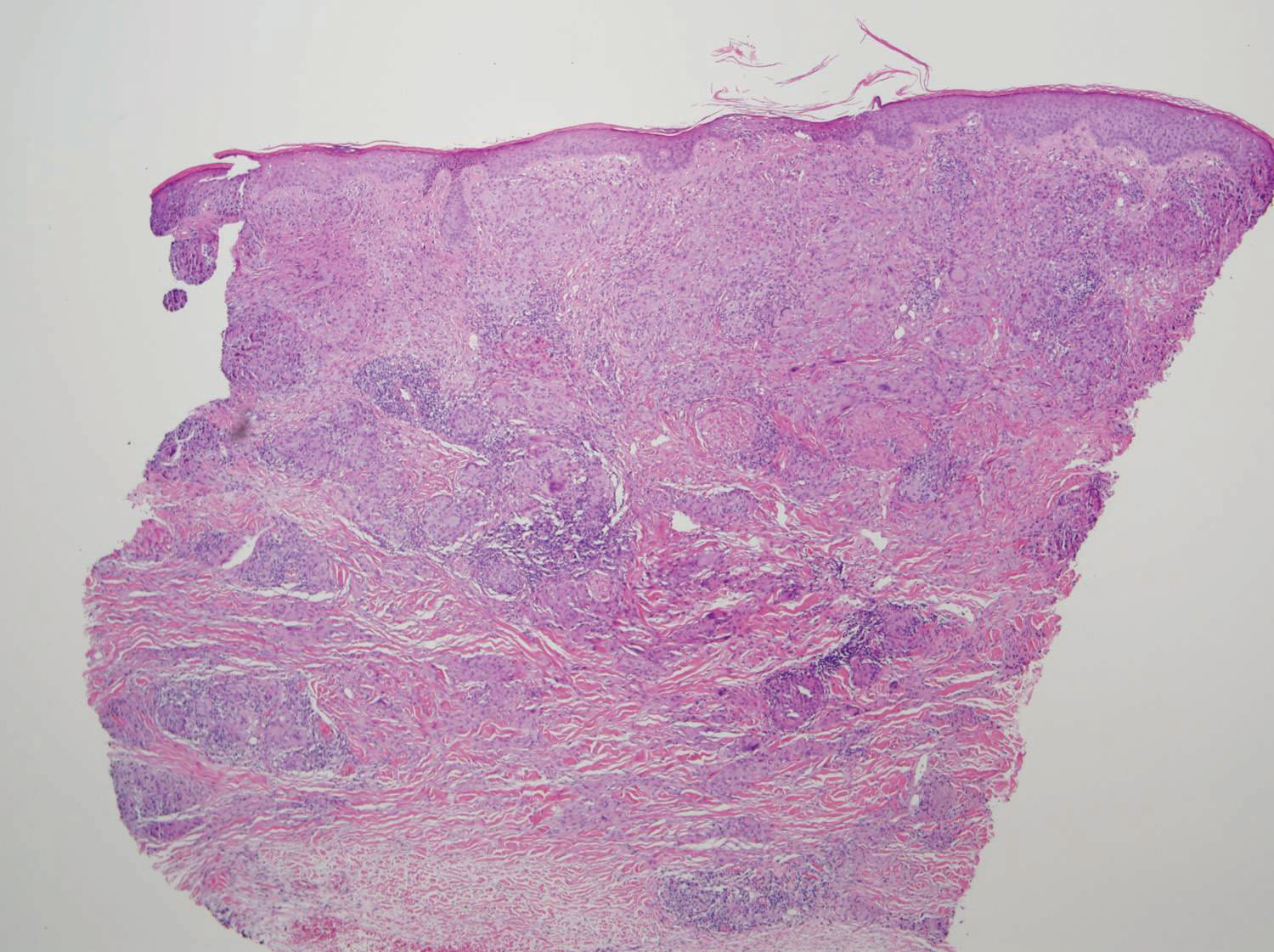

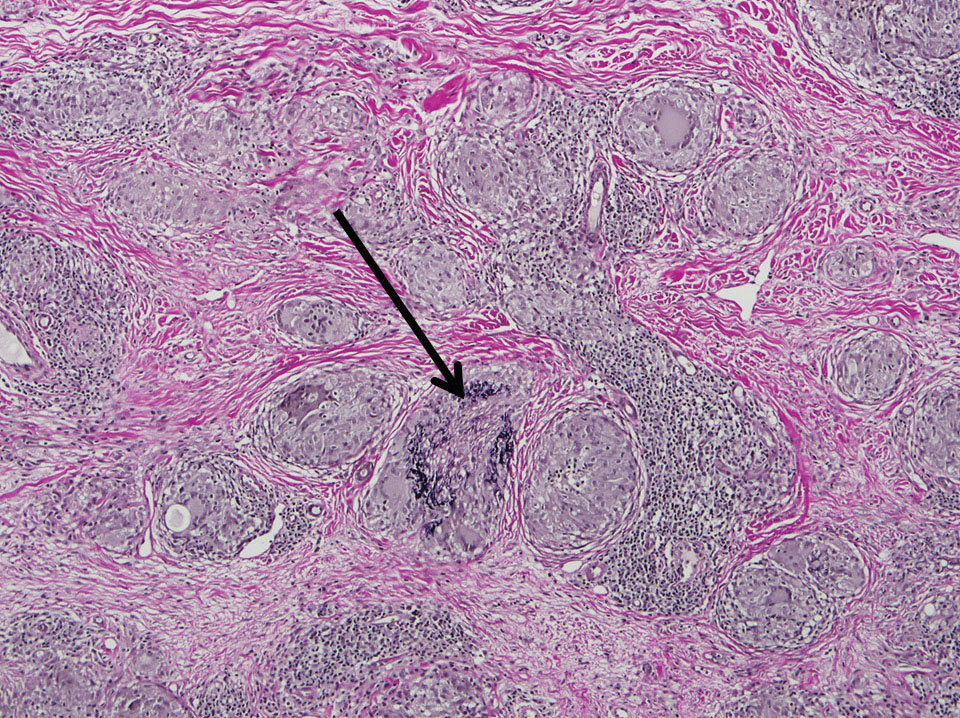

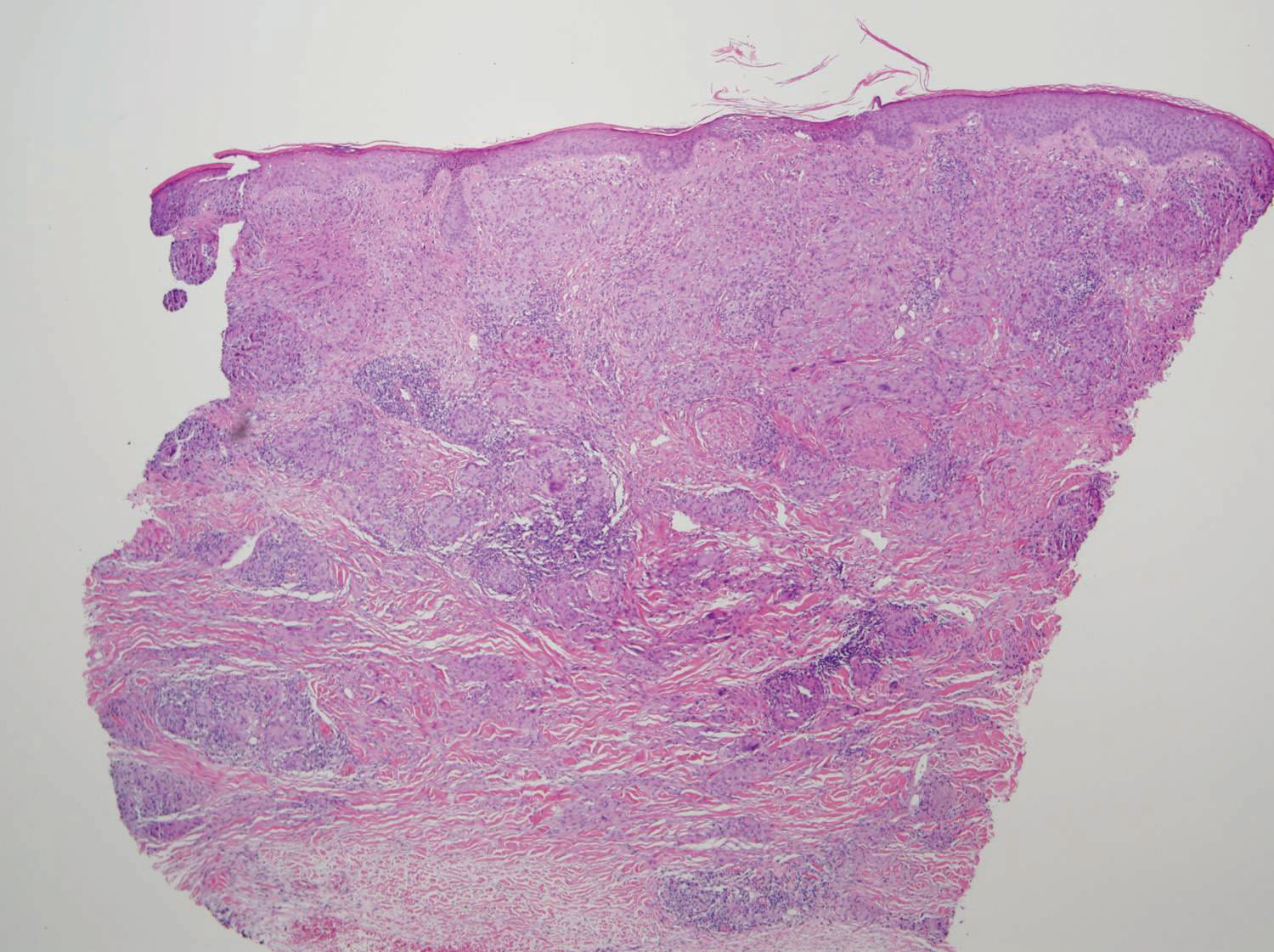

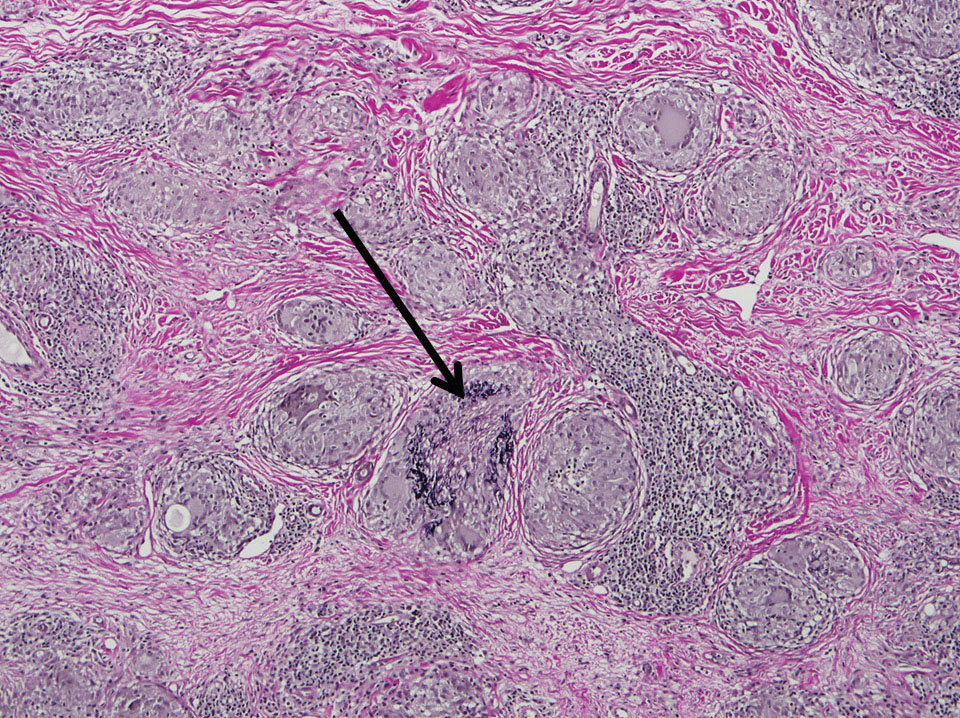

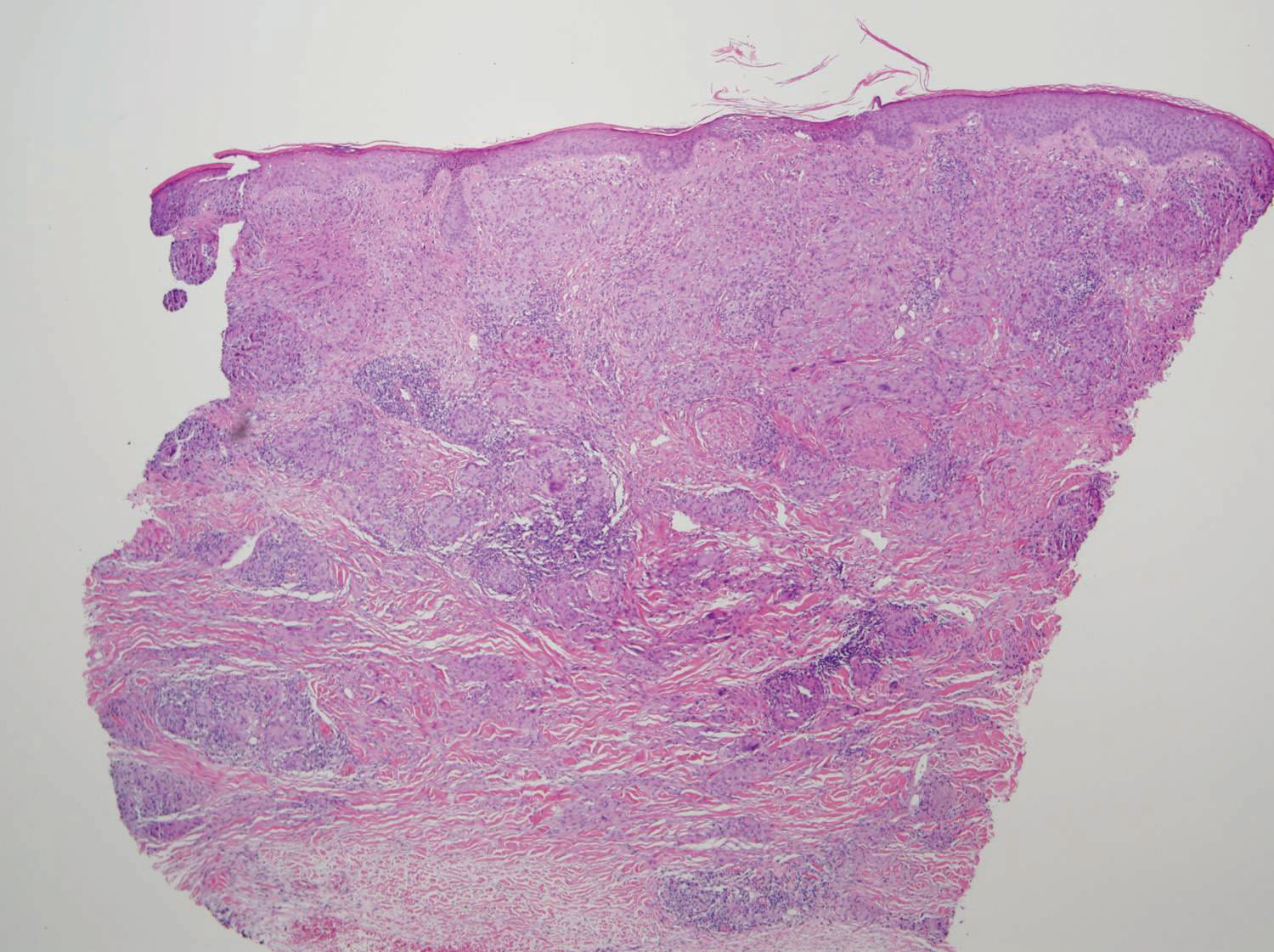

Two 4-mm punch biopsies of the right dorsal forearm and left side of the upper back revealed similar histologic features with a predominantly unremarkable epidermis. The dermis revealed a lymphohistiocytic infiltrate with prominent multinucleated giant cells organized into foreign body–type granulomas that extended into the deep dermis and subcutaneous tissue (Figure 2). In the granulomatous areas, there was a near-complete loss of elastic fibers with focal elastophagocytosis highlighted with Verhoeff-van Gieson (elastin) stain (Figure 3). Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver and Fite stains for microorganisms were negative, and there was an absence of necrobiosis, lipids, and mucin.

The histologic findings of a granulomatous dermatitis with loss of elastic fibers and elastophagocytosis in addition to the patient’s clinical presentation and history were consistent with the diagnosis of annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma (AEGCG). Infectious and other granulomatous diseases including sarcoidosis were ruled out via clinical history, unremarkable laboratory analysis (ie, complete blood cell count, chemistry panel, antinuclear antibody, urinalysis), and a normal chest radiograph. The histologic findings via the various stains were instrumental to the diagnosis. The patient was treated with fluocinonide and subsequently lost to follow-up.

Annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma is an uncommon cutaneous disease that presents with recurring annular plaques with raised erythematous borders and subsequent residual scarring.1 O’Brien2 originally described this condition in 1975 as an actinic granuloma due to similar histologic findings in areas of the patient’s sun-exposed skin. Ragaz and Ackerman3 disputed O’Brien’s2 description, claiming granulomatous inflammation was a primary pathologic process and not a consequence to damaged elastotic material. In 1979, Hanke et al4 termed the lesions as AEGCG because he did not find a correlation to the sun-exposed areas of the patients and did not see solar elastosis.

Although AEGCG has an unclear pathogenesis, cellular immunologic reactions induced by modified function of elastic fibers’ antigenicity contribute to AEGCG formation.5 Therefore, environmental and host factors may play a role in its etiopathogenesis. In one study, 37% of 38 Japanese patients with AEGCG were found to have definitive or latent diabetes mellitus, raising the possible role of diabetes in the structural damage of the elastic fibers.6

Patients typically are middle-aged women who present clinically with red or atrophic plaques that have slightly elevated borders. They have centripetal spread with a resulting atrophic center.7 Clinically, the differential diagnosis of this condition includes actinic granuloma, granuloma annulare, and granuloma multiforme.8

Histologically, AEGCG has a granulomatous component with multinucleated giant cells in the upper and mid dermis. This component typically is distributed peripherally to a central zone that lacks elastic tissue. Elastophagocytosis, a classic finding in AEGCG, is the phagocytosis of elastic fibers that can microscopically be seen in the cytoplasm of histiocytes and multinucleated giant cells. There also is an absence of necrobiosis, lipids, mucin, and a palisading arrangement of the granulomas. These findings distinguish AEGCG from granuloma annulare and necrobiosis lipoidica, the primary histologic differential diagnoses.9 In addition, consideration of entities consistently exhibiting elastophagocytosis such as mid-dermal elastolysis, papillary dermal elastolysis, actinic granuloma, and granulomatous slack skin should be considered.5,10,11

Therapy for AEGCG is broad and includes topical, intralesional, and systemic corticosteroids. Hydroxychloroquine, isotretinoin, clofazimine, dapsone, photochemotherapy, and cyclosporine also have been utilized with varying results. Other reports show improvement with surgical excision, cryotherapy, or cauterization of small lesions.12-15

1. Tock CL, Cohen PR. Annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma. Cutis. 1998;62:181-187.

2. O’Brien JP. Actinic granuloma: an annular connective tissue disorder affecting sun- and heat-damaged (elastotic) skin. Arch Dermatol. 1975;111:460-466.

3. Ragaz A, Ackerman AB. Is actinic granuloma a specific condition? Am J Dermatopathol. 1979;1:43-50.

4. Hanke CW, Bailin PL, Roenigk HH Jr. Annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma. a clinicopathologic study of five cases and a review of similar entities. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1979;1:413-421.

5. El-Khoury J, Kurban M, Abbas O. Elastophagocytosis: underlying mechanisms and associated cutaneous entities. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:934-44.

6. Aso Y, Izaki Y, Teraki Y. Annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma associated with diabetes mellitus: a case report and review of the Japanese literature. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2011;36:917-919.

7. Pestoni C, Pereiro M Jr, Toribio J. Annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma produced on an old burn scar and spreading after a mechanical trauma. Acta Derm Venereol. 2003;83:312-313.

8. Oka M, Kunisada M, Nishigori C. Generalized annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma with sparing of striae distensae. J Dermatol. 2013;40:220-222.

9. Limas C. The spectrum of primary cutaneous elastolytic granulomas and their distinction from granuloma annulare: a clinicopathological analysis. Histopathology. 2004;44:277-282.

10. McGrae JD Jr. Actinic granuloma: a clinical, histopathologic, and immunocytochemical study. Arch Dermatol. 1986;122:43-47.

11. Shah A, Safaya A. Granulomatous slack skin disease: a review, in comparison with mycosis fungoides. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2012;26:1472-1478.

12. Chou WT, Tsai TF, Hung CM, et al. Multiple annular erythematous plaques on the back. Annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma (AEGCG). Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2011;77:727-728.

13. Pérez-Pérez L, Garcia-Gavin J, Alleque F, et al. Successful treatment of generalized elastolytic giant cell granuloma with psoralen-ultraviolet A. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2012;28:264-266.

14. Babuna G, Buyukbabani N, Yazganoglu KD, et al. Effective treatment with hydroxychloroquine in a case of annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2011;77:110-111.

15. Can B, Kavala M, Türkoglu Z, et al. Successful treatment of annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma with hydroxylchloroquine. Int J Dermatol. 2013;52:509-511.

To the Editor:

A 52-year-old woman with a medical history of migraines and cervicalgia presented with lesions on the right arm, back, and right calf. The patient stated that the lesions began as small papules that had grown over 13 months, with the largest papule on the right forearm. She reported no itching, bleeding, pain, discharge, or other symptoms associated with the lesions. She had a multiple-year history of similar lesions that did not respond to treatment with antifungals, moderate-potency steroids, and other over-the-counter creams. The lesions would resolve spontaneously with scarring and subsequently recur. Prior skin biopsies were inconclusive. The patient did not report any systemic symptoms or a personal or family history of connective tissue diseases.

Physical examination revealed a 4-cm asymmetric, annular, erythematous plaque with central clearing on the right dorsal forearm with defined margins except over the distal aspect (Figure 1). She also had several 1- to 2-cm erythematous, nummular, asymmetric plaques on the right upper arm with well-defined margins. She had several lesions over the central and left sides of the upper back that were similar to the lesions on the upper arm.

Two 4-mm punch biopsies of the right dorsal forearm and left side of the upper back revealed similar histologic features with a predominantly unremarkable epidermis. The dermis revealed a lymphohistiocytic infiltrate with prominent multinucleated giant cells organized into foreign body–type granulomas that extended into the deep dermis and subcutaneous tissue (Figure 2). In the granulomatous areas, there was a near-complete loss of elastic fibers with focal elastophagocytosis highlighted with Verhoeff-van Gieson (elastin) stain (Figure 3). Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver and Fite stains for microorganisms were negative, and there was an absence of necrobiosis, lipids, and mucin.

The histologic findings of a granulomatous dermatitis with loss of elastic fibers and elastophagocytosis in addition to the patient’s clinical presentation and history were consistent with the diagnosis of annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma (AEGCG). Infectious and other granulomatous diseases including sarcoidosis were ruled out via clinical history, unremarkable laboratory analysis (ie, complete blood cell count, chemistry panel, antinuclear antibody, urinalysis), and a normal chest radiograph. The histologic findings via the various stains were instrumental to the diagnosis. The patient was treated with fluocinonide and subsequently lost to follow-up.

Annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma is an uncommon cutaneous disease that presents with recurring annular plaques with raised erythematous borders and subsequent residual scarring.1 O’Brien2 originally described this condition in 1975 as an actinic granuloma due to similar histologic findings in areas of the patient’s sun-exposed skin. Ragaz and Ackerman3 disputed O’Brien’s2 description, claiming granulomatous inflammation was a primary pathologic process and not a consequence to damaged elastotic material. In 1979, Hanke et al4 termed the lesions as AEGCG because he did not find a correlation to the sun-exposed areas of the patients and did not see solar elastosis.

Although AEGCG has an unclear pathogenesis, cellular immunologic reactions induced by modified function of elastic fibers’ antigenicity contribute to AEGCG formation.5 Therefore, environmental and host factors may play a role in its etiopathogenesis. In one study, 37% of 38 Japanese patients with AEGCG were found to have definitive or latent diabetes mellitus, raising the possible role of diabetes in the structural damage of the elastic fibers.6

Patients typically are middle-aged women who present clinically with red or atrophic plaques that have slightly elevated borders. They have centripetal spread with a resulting atrophic center.7 Clinically, the differential diagnosis of this condition includes actinic granuloma, granuloma annulare, and granuloma multiforme.8

Histologically, AEGCG has a granulomatous component with multinucleated giant cells in the upper and mid dermis. This component typically is distributed peripherally to a central zone that lacks elastic tissue. Elastophagocytosis, a classic finding in AEGCG, is the phagocytosis of elastic fibers that can microscopically be seen in the cytoplasm of histiocytes and multinucleated giant cells. There also is an absence of necrobiosis, lipids, mucin, and a palisading arrangement of the granulomas. These findings distinguish AEGCG from granuloma annulare and necrobiosis lipoidica, the primary histologic differential diagnoses.9 In addition, consideration of entities consistently exhibiting elastophagocytosis such as mid-dermal elastolysis, papillary dermal elastolysis, actinic granuloma, and granulomatous slack skin should be considered.5,10,11

Therapy for AEGCG is broad and includes topical, intralesional, and systemic corticosteroids. Hydroxychloroquine, isotretinoin, clofazimine, dapsone, photochemotherapy, and cyclosporine also have been utilized with varying results. Other reports show improvement with surgical excision, cryotherapy, or cauterization of small lesions.12-15

To the Editor:

A 52-year-old woman with a medical history of migraines and cervicalgia presented with lesions on the right arm, back, and right calf. The patient stated that the lesions began as small papules that had grown over 13 months, with the largest papule on the right forearm. She reported no itching, bleeding, pain, discharge, or other symptoms associated with the lesions. She had a multiple-year history of similar lesions that did not respond to treatment with antifungals, moderate-potency steroids, and other over-the-counter creams. The lesions would resolve spontaneously with scarring and subsequently recur. Prior skin biopsies were inconclusive. The patient did not report any systemic symptoms or a personal or family history of connective tissue diseases.

Physical examination revealed a 4-cm asymmetric, annular, erythematous plaque with central clearing on the right dorsal forearm with defined margins except over the distal aspect (Figure 1). She also had several 1- to 2-cm erythematous, nummular, asymmetric plaques on the right upper arm with well-defined margins. She had several lesions over the central and left sides of the upper back that were similar to the lesions on the upper arm.

Two 4-mm punch biopsies of the right dorsal forearm and left side of the upper back revealed similar histologic features with a predominantly unremarkable epidermis. The dermis revealed a lymphohistiocytic infiltrate with prominent multinucleated giant cells organized into foreign body–type granulomas that extended into the deep dermis and subcutaneous tissue (Figure 2). In the granulomatous areas, there was a near-complete loss of elastic fibers with focal elastophagocytosis highlighted with Verhoeff-van Gieson (elastin) stain (Figure 3). Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver and Fite stains for microorganisms were negative, and there was an absence of necrobiosis, lipids, and mucin.

The histologic findings of a granulomatous dermatitis with loss of elastic fibers and elastophagocytosis in addition to the patient’s clinical presentation and history were consistent with the diagnosis of annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma (AEGCG). Infectious and other granulomatous diseases including sarcoidosis were ruled out via clinical history, unremarkable laboratory analysis (ie, complete blood cell count, chemistry panel, antinuclear antibody, urinalysis), and a normal chest radiograph. The histologic findings via the various stains were instrumental to the diagnosis. The patient was treated with fluocinonide and subsequently lost to follow-up.

Annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma is an uncommon cutaneous disease that presents with recurring annular plaques with raised erythematous borders and subsequent residual scarring.1 O’Brien2 originally described this condition in 1975 as an actinic granuloma due to similar histologic findings in areas of the patient’s sun-exposed skin. Ragaz and Ackerman3 disputed O’Brien’s2 description, claiming granulomatous inflammation was a primary pathologic process and not a consequence to damaged elastotic material. In 1979, Hanke et al4 termed the lesions as AEGCG because he did not find a correlation to the sun-exposed areas of the patients and did not see solar elastosis.

Although AEGCG has an unclear pathogenesis, cellular immunologic reactions induced by modified function of elastic fibers’ antigenicity contribute to AEGCG formation.5 Therefore, environmental and host factors may play a role in its etiopathogenesis. In one study, 37% of 38 Japanese patients with AEGCG were found to have definitive or latent diabetes mellitus, raising the possible role of diabetes in the structural damage of the elastic fibers.6

Patients typically are middle-aged women who present clinically with red or atrophic plaques that have slightly elevated borders. They have centripetal spread with a resulting atrophic center.7 Clinically, the differential diagnosis of this condition includes actinic granuloma, granuloma annulare, and granuloma multiforme.8

Histologically, AEGCG has a granulomatous component with multinucleated giant cells in the upper and mid dermis. This component typically is distributed peripherally to a central zone that lacks elastic tissue. Elastophagocytosis, a classic finding in AEGCG, is the phagocytosis of elastic fibers that can microscopically be seen in the cytoplasm of histiocytes and multinucleated giant cells. There also is an absence of necrobiosis, lipids, mucin, and a palisading arrangement of the granulomas. These findings distinguish AEGCG from granuloma annulare and necrobiosis lipoidica, the primary histologic differential diagnoses.9 In addition, consideration of entities consistently exhibiting elastophagocytosis such as mid-dermal elastolysis, papillary dermal elastolysis, actinic granuloma, and granulomatous slack skin should be considered.5,10,11

Therapy for AEGCG is broad and includes topical, intralesional, and systemic corticosteroids. Hydroxychloroquine, isotretinoin, clofazimine, dapsone, photochemotherapy, and cyclosporine also have been utilized with varying results. Other reports show improvement with surgical excision, cryotherapy, or cauterization of small lesions.12-15

1. Tock CL, Cohen PR. Annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma. Cutis. 1998;62:181-187.

2. O’Brien JP. Actinic granuloma: an annular connective tissue disorder affecting sun- and heat-damaged (elastotic) skin. Arch Dermatol. 1975;111:460-466.

3. Ragaz A, Ackerman AB. Is actinic granuloma a specific condition? Am J Dermatopathol. 1979;1:43-50.

4. Hanke CW, Bailin PL, Roenigk HH Jr. Annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma. a clinicopathologic study of five cases and a review of similar entities. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1979;1:413-421.

5. El-Khoury J, Kurban M, Abbas O. Elastophagocytosis: underlying mechanisms and associated cutaneous entities. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:934-44.

6. Aso Y, Izaki Y, Teraki Y. Annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma associated with diabetes mellitus: a case report and review of the Japanese literature. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2011;36:917-919.

7. Pestoni C, Pereiro M Jr, Toribio J. Annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma produced on an old burn scar and spreading after a mechanical trauma. Acta Derm Venereol. 2003;83:312-313.

8. Oka M, Kunisada M, Nishigori C. Generalized annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma with sparing of striae distensae. J Dermatol. 2013;40:220-222.

9. Limas C. The spectrum of primary cutaneous elastolytic granulomas and their distinction from granuloma annulare: a clinicopathological analysis. Histopathology. 2004;44:277-282.

10. McGrae JD Jr. Actinic granuloma: a clinical, histopathologic, and immunocytochemical study. Arch Dermatol. 1986;122:43-47.

11. Shah A, Safaya A. Granulomatous slack skin disease: a review, in comparison with mycosis fungoides. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2012;26:1472-1478.

12. Chou WT, Tsai TF, Hung CM, et al. Multiple annular erythematous plaques on the back. Annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma (AEGCG). Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2011;77:727-728.

13. Pérez-Pérez L, Garcia-Gavin J, Alleque F, et al. Successful treatment of generalized elastolytic giant cell granuloma with psoralen-ultraviolet A. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2012;28:264-266.

14. Babuna G, Buyukbabani N, Yazganoglu KD, et al. Effective treatment with hydroxychloroquine in a case of annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2011;77:110-111.

15. Can B, Kavala M, Türkoglu Z, et al. Successful treatment of annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma with hydroxylchloroquine. Int J Dermatol. 2013;52:509-511.

1. Tock CL, Cohen PR. Annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma. Cutis. 1998;62:181-187.

2. O’Brien JP. Actinic granuloma: an annular connective tissue disorder affecting sun- and heat-damaged (elastotic) skin. Arch Dermatol. 1975;111:460-466.

3. Ragaz A, Ackerman AB. Is actinic granuloma a specific condition? Am J Dermatopathol. 1979;1:43-50.

4. Hanke CW, Bailin PL, Roenigk HH Jr. Annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma. a clinicopathologic study of five cases and a review of similar entities. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1979;1:413-421.

5. El-Khoury J, Kurban M, Abbas O. Elastophagocytosis: underlying mechanisms and associated cutaneous entities. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:934-44.

6. Aso Y, Izaki Y, Teraki Y. Annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma associated with diabetes mellitus: a case report and review of the Japanese literature. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2011;36:917-919.

7. Pestoni C, Pereiro M Jr, Toribio J. Annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma produced on an old burn scar and spreading after a mechanical trauma. Acta Derm Venereol. 2003;83:312-313.

8. Oka M, Kunisada M, Nishigori C. Generalized annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma with sparing of striae distensae. J Dermatol. 2013;40:220-222.

9. Limas C. The spectrum of primary cutaneous elastolytic granulomas and their distinction from granuloma annulare: a clinicopathological analysis. Histopathology. 2004;44:277-282.

10. McGrae JD Jr. Actinic granuloma: a clinical, histopathologic, and immunocytochemical study. Arch Dermatol. 1986;122:43-47.

11. Shah A, Safaya A. Granulomatous slack skin disease: a review, in comparison with mycosis fungoides. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2012;26:1472-1478.

12. Chou WT, Tsai TF, Hung CM, et al. Multiple annular erythematous plaques on the back. Annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma (AEGCG). Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2011;77:727-728.

13. Pérez-Pérez L, Garcia-Gavin J, Alleque F, et al. Successful treatment of generalized elastolytic giant cell granuloma with psoralen-ultraviolet A. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2012;28:264-266.

14. Babuna G, Buyukbabani N, Yazganoglu KD, et al. Effective treatment with hydroxychloroquine in a case of annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2011;77:110-111.

15. Can B, Kavala M, Türkoglu Z, et al. Successful treatment of annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma with hydroxylchloroquine. Int J Dermatol. 2013;52:509-511.

Practice Points

- Annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma (AEGCG) should be kept in the differential diagnosis when assessing a middle-aged woman with recurring annular plaques with a raised border and an atrophic center on both sun-exposed and sun-protected areas of the body.

- Histologically, AEGCG classically has a granulomatous component in the dermis that lacks elastic tissue and has no necrobiosis, lipids, or mucin. Staining with elastin may be necessary to highlight these areas as well as demonstrate elastophagocytosis.