User login

Weakness and facial droop: Is it a stroke?

CASE Sudden weakness

Ms. G, age 59, presents to a local critical access (rural) hospital after an episode of sudden-onset left-sided weakness followed by unconsciousness. She regained consciousness quickly and is awake when she arrives at the hospital. This event was not witnessed, although family members were nearby to call emergency personnel.

a) CT scan

b) MRI

c) EEG

d) head and neck magnetic resonance angiogram (MRA)

EXAMINATION Unremarkable

In the emergency department, Ms. G demonstrates left facial droop, left-sided weakness of her arm and leg, and aphasia. She says she has a severe headache that began after she regained consciousness. She is unable to see out of her left eye.

Ms. G’s NIH Stroke Scale score is 13, indicating a moderate stroke; an emergent head CT does not demonstrate any acute hemorrhagic process. Tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) is administered for a suspected stroke approximately 2 hours after her symptoms began. She is transferred to a larger, tertiary care hospital for further workup and observation.

Upon admission to the ICU, Ms. G’s laboratory values are: sodium, 137 mEq/L; potassium, 5.1 mEq/L; creatinine, 1.26 mg/dL; lipase, 126 U/L; and lactic acid, 9 mg/dL. The glucose level is within normal limits and her urinalysis is unremarkable.

Vital signs are stable and Ms. G is not in acute distress. A physical exam demonstrates 4/5 strength in the left-upper and -lower extremities. Additionally, there are 2+ deep tendon reflexes bilaterally in the biceps, triceps, and brachioradialis. She has left-sided facial droop while in the ICU, and continues to demonstrate some aphasia—although she is alert and oriented to person, time, and place.

The medical history is significant for depression, restless leg syndrome, tonic-clonic seizures, and previous stroke-like events. Medications include amitriptyline, 25 mg/d; citalopram, 20 mg/d; valproate, 1,200 mg/d; and ropinirole, 0.5 mg/d. Her mother has a history of stroke-like events, but her family history and social history are otherwise unremarkable.

The authors' observations

Conversion disorder requires the exclusion of medical causes that could explain the patient’s neurologic symptoms. It is prudent to rule out the most serious of the potential contributors to Ms. G’s condition—namely, an acute cerebrovascular accident. A CT scan did not find any significant pathology, however. In the ICU, an MRI showed no evidence of acute infarction based on diffusion-weighted imaging. A head and neck MRA demonstrated no hemodynamically significant stenosis of the internal carotid arteries. An EEG revealed generalized, polymorphic slow activity without evidence of seizures or epilepsy. An electrocardiogram showed normal ventricular size with an appropriate ejection fraction.

The ICU staff consulted psychiatry to evaluate a psychiatric cause of Ms. G’s symptoms.

An exhaustive and comprehensive workup was performed; there were no significant findings. Although laboratory tests were performed, it was the physical exam that suggested the diagnosis of conversion disorder. In that sense, the diagnostic tests were more of a supportive adjunct to the findings of the physical examination, which consistently failed to indicate a neurologic insult.

Hoover’s sign is a well-established test of functional weakness, in which the patient extends his (her) hip when the contralateral hip is flexed. However, there are other tests of functional weakness that can be useful when considering a conversion disorder diagnosis, including co-contraction, the so-called arm-drop sign, and the sternocleidomastoid test. Diukova and colleagues reported that 80% of patients with functional weakness demonstrated ipsilateral sternocleidomastoid weakness, compared with 11% with vascular hemiparesis.1

a) stroke

b) transient ischemic attack

c) conversion disorder

d) seizure disorder

Ms. G appeared to have suffered an acute ischemic event that caused her neurologic symptoms; her rather extensive psychiatric history was overlooked before the psychiatric service was consulted. When Ms. G was admitted to the ICU, the working differential was postictal seizure state rather than cerebrovascular accident. Ms. G had a poorly defined seizure history, and her history of stroke-like events was murky, at best. She had not been treated previously with tPA, and in all past instances her symptoms resolved spontaneously.

Ms. G’s case illustrates why conversion disorder is difficult to diagnose and why, perhaps, it is even a dangerous diagnostic consideration. Booij and colleagues described two patients with neurologic sequelae thought to be the result of conversion disorder; subsequent imaging demonstrated a posterior stroke.2 Over a 6-year period in an emergency department, Glick and coworkers identified six patients with neurologic pathology who were misdiagnosed with conversion disorder.3 In a study of 4,220 patients presenting to a psychiatric emergency service, three patients complained of extremity paralysis or pain, which was attributed to conversion disorder but later attributed to an organic disease.4

These studies emphasize the precarious nature of diagnosing conversion disorder. For that reason, an extensive medical workup is necessary prior to considering a diagnosis of conversion disorder. In Ms. G’s case, a reasonably thorough workup failed to reveal any obvious pathology. Only then was conversion disorder included as a diagnostic possibility.

EVALUATION Childhood abuse

When performing a mental status exam, Ms. G has poor eye contact, but is cooperative with our interview. She is disheveled and overweight, and denies suicidal or homicidal ideation. She displays constricted affect.

During the interview, we note a left facial droop, although Ms. G is able to smile fully. As the interview progresses, her facial droop seems to become more apparent as we discuss her past, including a history of childhood physical and sexual abuse. She has a history of depression and has been seeing an outpatient psychiatrist for the past year. Ms. G describes being hospitalized in a psychiatric unit, but she is unable to provide any details about when and where this occurred.

Ms. G admits to occasional auditory and visual hallucinations, mostly relating to the abuse she experienced as a child by her parents. She exhibits no other signs or symptoms of psychosis; the hallucinations she describes are consistent with flashbacks and vivid memories relating to the abuse. Ms. G also recently lost her job and is experiencing numerous financial stressors.

The authors' observations

There are many examples in the literature of patients with conversion disorder (Table 1),4 ranging from pseudoseizures, which are relatively common, to intriguing cases, such as cochlear implant failure.5

Some studies estimate that the prevalence of conversion disorder symptoms ranges from 16.1% to 21.9% in the general population.6 Somatoform disorders, including conversion disorder, often are comorbid with anxiety and depression. In one study, 26% of somatoform disorder patients also had depression or anxiety, or both.7 Patients with conversion disorder often report a history of childhood physical or sexual abuse.6 In many patients with conversion disorder, there also appears to be a significant association between the disorder and a recent and distant history of psychosocial stressors.8

Ms. G had an extensive history of abuse by her parents. Conversion disorder presenting as a stroke with realistic and convincing physical manifestations is an unusual presentation. There are case reports that detail this presentation, particularly in the emergency department setting.6

Clinical considerations

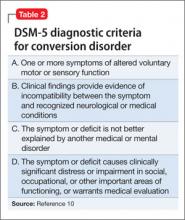

The relative uncertainty that accompanies a diagnosis of conversion disorder can be discomforting for clinicians. As demonstrated by Ms. G, as well as other case reports of conversion disorder, it takes time for the patient to find a clinician who will consider a diagnosis of conversion disorder.9 Largely, this is because DSM-5 requires that other medical causes be ruled out (Table 2).10 This often proves to be problematic because feigning, or the lack thereof, is difficult to prove.9

Further complicating the diagnosis is the lack of a diagnostic test. Neurologists can use video EEG or physical exam maneuvers such as the Hoover’s sign to help make a diagnosis of conversion disorder.11 In this sense, the physical exam maneuvers form the basis of making a diagnosis, while imaging and lab work support the diagnosis. Hoover’s sign, for example, has not been well studied in a controlled manner, but is recognized as a test that may aid a conversion disorder diagnosis. Clinicians should not solely rely upon these physical exam maneuvers; interpreting them in the context of the patient’s overall presentation is critical. This demonstrates the importance of using the physical exam as a way to guide the diagnosis in association with other tests.12

Despite the lack of pathology, studies demonstrate that patients with conversion disorder may have abnormal brain activity that causes them to perceive motor symptoms as involuntary.11 Therefore, there is a clear need for an increased understanding of psychiatric and neurologic components of diagnosing conversion disorder.8

With Ms. G, it was prudent to make a conversion disorder diagnosis to prevent harm to the patient should future stroke-like events occur. Without considering a conversion disorder diagnosis, a patient may continue to receive unnecessary interventions. Basic physical exam maneuvers, such as Hoover’s sign, can be performed quickly in the ED setting before proceeding with other potentially harmful interventions, such as administering tPA.

Treatment. There are few therapies for conversion disorder. This is, in part, because of lack of understanding about the disorder’s neurologic and biologic etiologies. Although there are some studies that support the use of cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), there is little evidence advocating the use of a single mechanism to treat conversion disorder.13 There is evidence that CBT is an effective treatment for several somatoform disorders, including conversion disorder. Research suggests that patients with somatoform disorder have better outcomes when CBT is added to a traditional follow-up.14,15

In Ms. G’s case, we provided information about the diagnosis and scheduled visits to continue her outpatient therapy.

Bottom Line

Conversion disorder is difficult to diagnose, and can mimic potentially life- threatening medical conditions. Conduct a thorough medical workup of these patients, even when it is tempting to jump to a diagnosis of conversion disorder. The use of physical exam maneuvers such as Hoover’s sign may help guide the diagnosis when used in conjunction with other testing.

Related Resources

- Conversion disorder. www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/ency/ article/000954.htm.

- Couprie W, Wijdicks EF, Rooijmans HG, et al. Outcome in conver- sion disorder: a follow up study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1995;58(6):750-752.

Drug Brand Names

Amitriptyline • Elavil Citalopram • Celexa

Ropinirole • Requip Valproate • Depakote

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Diukova GM, Stolajrova AV, Vein AM. Sternocleidomastoid (SCM) muscle test in patients with hysterical and organic paresis. J Neurol Sci. 2001;187(suppl 1):S108.

2. Booij HA, Hamburger HL, Jöbsis GJ, et al. Stroke mimicking conversion disorder: two young women who put our feet back on the ground. Pract Neurol. 2012;12(3):179-181.

3. Glick TH, Workman TP, Gaufberg SV. Suspected conversion disorder: foreseeable risks and avoidable errors. Acad Emerg Med. 2000;7(11):1272-1277.

4. Fishbain DA, Goldberg M. The misdiagnosis of conversion disorder in a psychiatric emergency service. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1991;13(3):177-181.

5. Carlson ML, Archibald DJ, Gifford RH, et al. Conversion disorder: a missed diagnosis leading to cochlear reimplantation. Otol Neurotol. 2011;32(1):36-38.

6. Sar V, Akyüz G, Kundakçi T, et al. Childhood trauma, dissociation, and psychiatric comorbidity in patients with conversion disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161(12):2271-2276.

7. de Waal MW, Arnold IA, Eekhof JA, et al. Somatoform disorders in general practice: prevalence, functional impairment and comorbidity with anxiety and depressive disorders. Br J Psychiatry. 2004;184:470-476.

8. Nicholson TR, Stone J, Kanaan RA. Conversion disorder: a problematic diagnosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2011;82(11):1267-1273.

9. Stone J, LaFrance WC, Jr, Levenson JL, et al. Issues for

DSM-5: conversion disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167(6): 626-627.

10. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

11. Voon V, Gallea C, Hattori N, et al. The involuntary nature of conversion disorder. Neurology. 2010;74(3):223-228.

12. Stone J, Zeman A, Sharpe M. Functional weakness and sensory disturbance. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2002; 73:241-245.

13. Aybek S, Kanaan RA, David AS. The neuropsychiatry of conversion disorder. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2008;21(3):275-280.

14. Kroenke K. Efficacy of treatment for somatoform disorders: a review of randomized controlled trials. Psychosom Med. 2007;69(9):881-888.

15. Sharpe M, Walker J, Williams C, et al. Guided self-help for functional (psychogenic) symptoms: a randomized controlled efficacy trial. Neurology. 2011;77(6):564-572.

CASE Sudden weakness

Ms. G, age 59, presents to a local critical access (rural) hospital after an episode of sudden-onset left-sided weakness followed by unconsciousness. She regained consciousness quickly and is awake when she arrives at the hospital. This event was not witnessed, although family members were nearby to call emergency personnel.

a) CT scan

b) MRI

c) EEG

d) head and neck magnetic resonance angiogram (MRA)

EXAMINATION Unremarkable

In the emergency department, Ms. G demonstrates left facial droop, left-sided weakness of her arm and leg, and aphasia. She says she has a severe headache that began after she regained consciousness. She is unable to see out of her left eye.

Ms. G’s NIH Stroke Scale score is 13, indicating a moderate stroke; an emergent head CT does not demonstrate any acute hemorrhagic process. Tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) is administered for a suspected stroke approximately 2 hours after her symptoms began. She is transferred to a larger, tertiary care hospital for further workup and observation.

Upon admission to the ICU, Ms. G’s laboratory values are: sodium, 137 mEq/L; potassium, 5.1 mEq/L; creatinine, 1.26 mg/dL; lipase, 126 U/L; and lactic acid, 9 mg/dL. The glucose level is within normal limits and her urinalysis is unremarkable.

Vital signs are stable and Ms. G is not in acute distress. A physical exam demonstrates 4/5 strength in the left-upper and -lower extremities. Additionally, there are 2+ deep tendon reflexes bilaterally in the biceps, triceps, and brachioradialis. She has left-sided facial droop while in the ICU, and continues to demonstrate some aphasia—although she is alert and oriented to person, time, and place.

The medical history is significant for depression, restless leg syndrome, tonic-clonic seizures, and previous stroke-like events. Medications include amitriptyline, 25 mg/d; citalopram, 20 mg/d; valproate, 1,200 mg/d; and ropinirole, 0.5 mg/d. Her mother has a history of stroke-like events, but her family history and social history are otherwise unremarkable.

The authors' observations

Conversion disorder requires the exclusion of medical causes that could explain the patient’s neurologic symptoms. It is prudent to rule out the most serious of the potential contributors to Ms. G’s condition—namely, an acute cerebrovascular accident. A CT scan did not find any significant pathology, however. In the ICU, an MRI showed no evidence of acute infarction based on diffusion-weighted imaging. A head and neck MRA demonstrated no hemodynamically significant stenosis of the internal carotid arteries. An EEG revealed generalized, polymorphic slow activity without evidence of seizures or epilepsy. An electrocardiogram showed normal ventricular size with an appropriate ejection fraction.

The ICU staff consulted psychiatry to evaluate a psychiatric cause of Ms. G’s symptoms.

An exhaustive and comprehensive workup was performed; there were no significant findings. Although laboratory tests were performed, it was the physical exam that suggested the diagnosis of conversion disorder. In that sense, the diagnostic tests were more of a supportive adjunct to the findings of the physical examination, which consistently failed to indicate a neurologic insult.

Hoover’s sign is a well-established test of functional weakness, in which the patient extends his (her) hip when the contralateral hip is flexed. However, there are other tests of functional weakness that can be useful when considering a conversion disorder diagnosis, including co-contraction, the so-called arm-drop sign, and the sternocleidomastoid test. Diukova and colleagues reported that 80% of patients with functional weakness demonstrated ipsilateral sternocleidomastoid weakness, compared with 11% with vascular hemiparesis.1

a) stroke

b) transient ischemic attack

c) conversion disorder

d) seizure disorder

Ms. G appeared to have suffered an acute ischemic event that caused her neurologic symptoms; her rather extensive psychiatric history was overlooked before the psychiatric service was consulted. When Ms. G was admitted to the ICU, the working differential was postictal seizure state rather than cerebrovascular accident. Ms. G had a poorly defined seizure history, and her history of stroke-like events was murky, at best. She had not been treated previously with tPA, and in all past instances her symptoms resolved spontaneously.

Ms. G’s case illustrates why conversion disorder is difficult to diagnose and why, perhaps, it is even a dangerous diagnostic consideration. Booij and colleagues described two patients with neurologic sequelae thought to be the result of conversion disorder; subsequent imaging demonstrated a posterior stroke.2 Over a 6-year period in an emergency department, Glick and coworkers identified six patients with neurologic pathology who were misdiagnosed with conversion disorder.3 In a study of 4,220 patients presenting to a psychiatric emergency service, three patients complained of extremity paralysis or pain, which was attributed to conversion disorder but later attributed to an organic disease.4

These studies emphasize the precarious nature of diagnosing conversion disorder. For that reason, an extensive medical workup is necessary prior to considering a diagnosis of conversion disorder. In Ms. G’s case, a reasonably thorough workup failed to reveal any obvious pathology. Only then was conversion disorder included as a diagnostic possibility.

EVALUATION Childhood abuse

When performing a mental status exam, Ms. G has poor eye contact, but is cooperative with our interview. She is disheveled and overweight, and denies suicidal or homicidal ideation. She displays constricted affect.

During the interview, we note a left facial droop, although Ms. G is able to smile fully. As the interview progresses, her facial droop seems to become more apparent as we discuss her past, including a history of childhood physical and sexual abuse. She has a history of depression and has been seeing an outpatient psychiatrist for the past year. Ms. G describes being hospitalized in a psychiatric unit, but she is unable to provide any details about when and where this occurred.

Ms. G admits to occasional auditory and visual hallucinations, mostly relating to the abuse she experienced as a child by her parents. She exhibits no other signs or symptoms of psychosis; the hallucinations she describes are consistent with flashbacks and vivid memories relating to the abuse. Ms. G also recently lost her job and is experiencing numerous financial stressors.

The authors' observations

There are many examples in the literature of patients with conversion disorder (Table 1),4 ranging from pseudoseizures, which are relatively common, to intriguing cases, such as cochlear implant failure.5

Some studies estimate that the prevalence of conversion disorder symptoms ranges from 16.1% to 21.9% in the general population.6 Somatoform disorders, including conversion disorder, often are comorbid with anxiety and depression. In one study, 26% of somatoform disorder patients also had depression or anxiety, or both.7 Patients with conversion disorder often report a history of childhood physical or sexual abuse.6 In many patients with conversion disorder, there also appears to be a significant association between the disorder and a recent and distant history of psychosocial stressors.8

Ms. G had an extensive history of abuse by her parents. Conversion disorder presenting as a stroke with realistic and convincing physical manifestations is an unusual presentation. There are case reports that detail this presentation, particularly in the emergency department setting.6

Clinical considerations

The relative uncertainty that accompanies a diagnosis of conversion disorder can be discomforting for clinicians. As demonstrated by Ms. G, as well as other case reports of conversion disorder, it takes time for the patient to find a clinician who will consider a diagnosis of conversion disorder.9 Largely, this is because DSM-5 requires that other medical causes be ruled out (Table 2).10 This often proves to be problematic because feigning, or the lack thereof, is difficult to prove.9

Further complicating the diagnosis is the lack of a diagnostic test. Neurologists can use video EEG or physical exam maneuvers such as the Hoover’s sign to help make a diagnosis of conversion disorder.11 In this sense, the physical exam maneuvers form the basis of making a diagnosis, while imaging and lab work support the diagnosis. Hoover’s sign, for example, has not been well studied in a controlled manner, but is recognized as a test that may aid a conversion disorder diagnosis. Clinicians should not solely rely upon these physical exam maneuvers; interpreting them in the context of the patient’s overall presentation is critical. This demonstrates the importance of using the physical exam as a way to guide the diagnosis in association with other tests.12

Despite the lack of pathology, studies demonstrate that patients with conversion disorder may have abnormal brain activity that causes them to perceive motor symptoms as involuntary.11 Therefore, there is a clear need for an increased understanding of psychiatric and neurologic components of diagnosing conversion disorder.8

With Ms. G, it was prudent to make a conversion disorder diagnosis to prevent harm to the patient should future stroke-like events occur. Without considering a conversion disorder diagnosis, a patient may continue to receive unnecessary interventions. Basic physical exam maneuvers, such as Hoover’s sign, can be performed quickly in the ED setting before proceeding with other potentially harmful interventions, such as administering tPA.

Treatment. There are few therapies for conversion disorder. This is, in part, because of lack of understanding about the disorder’s neurologic and biologic etiologies. Although there are some studies that support the use of cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), there is little evidence advocating the use of a single mechanism to treat conversion disorder.13 There is evidence that CBT is an effective treatment for several somatoform disorders, including conversion disorder. Research suggests that patients with somatoform disorder have better outcomes when CBT is added to a traditional follow-up.14,15

In Ms. G’s case, we provided information about the diagnosis and scheduled visits to continue her outpatient therapy.

Bottom Line

Conversion disorder is difficult to diagnose, and can mimic potentially life- threatening medical conditions. Conduct a thorough medical workup of these patients, even when it is tempting to jump to a diagnosis of conversion disorder. The use of physical exam maneuvers such as Hoover’s sign may help guide the diagnosis when used in conjunction with other testing.

Related Resources

- Conversion disorder. www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/ency/ article/000954.htm.

- Couprie W, Wijdicks EF, Rooijmans HG, et al. Outcome in conver- sion disorder: a follow up study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1995;58(6):750-752.

Drug Brand Names

Amitriptyline • Elavil Citalopram • Celexa

Ropinirole • Requip Valproate • Depakote

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

CASE Sudden weakness

Ms. G, age 59, presents to a local critical access (rural) hospital after an episode of sudden-onset left-sided weakness followed by unconsciousness. She regained consciousness quickly and is awake when she arrives at the hospital. This event was not witnessed, although family members were nearby to call emergency personnel.

a) CT scan

b) MRI

c) EEG

d) head and neck magnetic resonance angiogram (MRA)

EXAMINATION Unremarkable

In the emergency department, Ms. G demonstrates left facial droop, left-sided weakness of her arm and leg, and aphasia. She says she has a severe headache that began after she regained consciousness. She is unable to see out of her left eye.

Ms. G’s NIH Stroke Scale score is 13, indicating a moderate stroke; an emergent head CT does not demonstrate any acute hemorrhagic process. Tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) is administered for a suspected stroke approximately 2 hours after her symptoms began. She is transferred to a larger, tertiary care hospital for further workup and observation.

Upon admission to the ICU, Ms. G’s laboratory values are: sodium, 137 mEq/L; potassium, 5.1 mEq/L; creatinine, 1.26 mg/dL; lipase, 126 U/L; and lactic acid, 9 mg/dL. The glucose level is within normal limits and her urinalysis is unremarkable.

Vital signs are stable and Ms. G is not in acute distress. A physical exam demonstrates 4/5 strength in the left-upper and -lower extremities. Additionally, there are 2+ deep tendon reflexes bilaterally in the biceps, triceps, and brachioradialis. She has left-sided facial droop while in the ICU, and continues to demonstrate some aphasia—although she is alert and oriented to person, time, and place.

The medical history is significant for depression, restless leg syndrome, tonic-clonic seizures, and previous stroke-like events. Medications include amitriptyline, 25 mg/d; citalopram, 20 mg/d; valproate, 1,200 mg/d; and ropinirole, 0.5 mg/d. Her mother has a history of stroke-like events, but her family history and social history are otherwise unremarkable.

The authors' observations

Conversion disorder requires the exclusion of medical causes that could explain the patient’s neurologic symptoms. It is prudent to rule out the most serious of the potential contributors to Ms. G’s condition—namely, an acute cerebrovascular accident. A CT scan did not find any significant pathology, however. In the ICU, an MRI showed no evidence of acute infarction based on diffusion-weighted imaging. A head and neck MRA demonstrated no hemodynamically significant stenosis of the internal carotid arteries. An EEG revealed generalized, polymorphic slow activity without evidence of seizures or epilepsy. An electrocardiogram showed normal ventricular size with an appropriate ejection fraction.

The ICU staff consulted psychiatry to evaluate a psychiatric cause of Ms. G’s symptoms.

An exhaustive and comprehensive workup was performed; there were no significant findings. Although laboratory tests were performed, it was the physical exam that suggested the diagnosis of conversion disorder. In that sense, the diagnostic tests were more of a supportive adjunct to the findings of the physical examination, which consistently failed to indicate a neurologic insult.

Hoover’s sign is a well-established test of functional weakness, in which the patient extends his (her) hip when the contralateral hip is flexed. However, there are other tests of functional weakness that can be useful when considering a conversion disorder diagnosis, including co-contraction, the so-called arm-drop sign, and the sternocleidomastoid test. Diukova and colleagues reported that 80% of patients with functional weakness demonstrated ipsilateral sternocleidomastoid weakness, compared with 11% with vascular hemiparesis.1

a) stroke

b) transient ischemic attack

c) conversion disorder

d) seizure disorder

Ms. G appeared to have suffered an acute ischemic event that caused her neurologic symptoms; her rather extensive psychiatric history was overlooked before the psychiatric service was consulted. When Ms. G was admitted to the ICU, the working differential was postictal seizure state rather than cerebrovascular accident. Ms. G had a poorly defined seizure history, and her history of stroke-like events was murky, at best. She had not been treated previously with tPA, and in all past instances her symptoms resolved spontaneously.

Ms. G’s case illustrates why conversion disorder is difficult to diagnose and why, perhaps, it is even a dangerous diagnostic consideration. Booij and colleagues described two patients with neurologic sequelae thought to be the result of conversion disorder; subsequent imaging demonstrated a posterior stroke.2 Over a 6-year period in an emergency department, Glick and coworkers identified six patients with neurologic pathology who were misdiagnosed with conversion disorder.3 In a study of 4,220 patients presenting to a psychiatric emergency service, three patients complained of extremity paralysis or pain, which was attributed to conversion disorder but later attributed to an organic disease.4

These studies emphasize the precarious nature of diagnosing conversion disorder. For that reason, an extensive medical workup is necessary prior to considering a diagnosis of conversion disorder. In Ms. G’s case, a reasonably thorough workup failed to reveal any obvious pathology. Only then was conversion disorder included as a diagnostic possibility.

EVALUATION Childhood abuse

When performing a mental status exam, Ms. G has poor eye contact, but is cooperative with our interview. She is disheveled and overweight, and denies suicidal or homicidal ideation. She displays constricted affect.

During the interview, we note a left facial droop, although Ms. G is able to smile fully. As the interview progresses, her facial droop seems to become more apparent as we discuss her past, including a history of childhood physical and sexual abuse. She has a history of depression and has been seeing an outpatient psychiatrist for the past year. Ms. G describes being hospitalized in a psychiatric unit, but she is unable to provide any details about when and where this occurred.

Ms. G admits to occasional auditory and visual hallucinations, mostly relating to the abuse she experienced as a child by her parents. She exhibits no other signs or symptoms of psychosis; the hallucinations she describes are consistent with flashbacks and vivid memories relating to the abuse. Ms. G also recently lost her job and is experiencing numerous financial stressors.

The authors' observations

There are many examples in the literature of patients with conversion disorder (Table 1),4 ranging from pseudoseizures, which are relatively common, to intriguing cases, such as cochlear implant failure.5

Some studies estimate that the prevalence of conversion disorder symptoms ranges from 16.1% to 21.9% in the general population.6 Somatoform disorders, including conversion disorder, often are comorbid with anxiety and depression. In one study, 26% of somatoform disorder patients also had depression or anxiety, or both.7 Patients with conversion disorder often report a history of childhood physical or sexual abuse.6 In many patients with conversion disorder, there also appears to be a significant association between the disorder and a recent and distant history of psychosocial stressors.8

Ms. G had an extensive history of abuse by her parents. Conversion disorder presenting as a stroke with realistic and convincing physical manifestations is an unusual presentation. There are case reports that detail this presentation, particularly in the emergency department setting.6

Clinical considerations

The relative uncertainty that accompanies a diagnosis of conversion disorder can be discomforting for clinicians. As demonstrated by Ms. G, as well as other case reports of conversion disorder, it takes time for the patient to find a clinician who will consider a diagnosis of conversion disorder.9 Largely, this is because DSM-5 requires that other medical causes be ruled out (Table 2).10 This often proves to be problematic because feigning, or the lack thereof, is difficult to prove.9

Further complicating the diagnosis is the lack of a diagnostic test. Neurologists can use video EEG or physical exam maneuvers such as the Hoover’s sign to help make a diagnosis of conversion disorder.11 In this sense, the physical exam maneuvers form the basis of making a diagnosis, while imaging and lab work support the diagnosis. Hoover’s sign, for example, has not been well studied in a controlled manner, but is recognized as a test that may aid a conversion disorder diagnosis. Clinicians should not solely rely upon these physical exam maneuvers; interpreting them in the context of the patient’s overall presentation is critical. This demonstrates the importance of using the physical exam as a way to guide the diagnosis in association with other tests.12

Despite the lack of pathology, studies demonstrate that patients with conversion disorder may have abnormal brain activity that causes them to perceive motor symptoms as involuntary.11 Therefore, there is a clear need for an increased understanding of psychiatric and neurologic components of diagnosing conversion disorder.8

With Ms. G, it was prudent to make a conversion disorder diagnosis to prevent harm to the patient should future stroke-like events occur. Without considering a conversion disorder diagnosis, a patient may continue to receive unnecessary interventions. Basic physical exam maneuvers, such as Hoover’s sign, can be performed quickly in the ED setting before proceeding with other potentially harmful interventions, such as administering tPA.

Treatment. There are few therapies for conversion disorder. This is, in part, because of lack of understanding about the disorder’s neurologic and biologic etiologies. Although there are some studies that support the use of cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), there is little evidence advocating the use of a single mechanism to treat conversion disorder.13 There is evidence that CBT is an effective treatment for several somatoform disorders, including conversion disorder. Research suggests that patients with somatoform disorder have better outcomes when CBT is added to a traditional follow-up.14,15

In Ms. G’s case, we provided information about the diagnosis and scheduled visits to continue her outpatient therapy.

Bottom Line

Conversion disorder is difficult to diagnose, and can mimic potentially life- threatening medical conditions. Conduct a thorough medical workup of these patients, even when it is tempting to jump to a diagnosis of conversion disorder. The use of physical exam maneuvers such as Hoover’s sign may help guide the diagnosis when used in conjunction with other testing.

Related Resources

- Conversion disorder. www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/ency/ article/000954.htm.

- Couprie W, Wijdicks EF, Rooijmans HG, et al. Outcome in conver- sion disorder: a follow up study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1995;58(6):750-752.

Drug Brand Names

Amitriptyline • Elavil Citalopram • Celexa

Ropinirole • Requip Valproate • Depakote

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Diukova GM, Stolajrova AV, Vein AM. Sternocleidomastoid (SCM) muscle test in patients with hysterical and organic paresis. J Neurol Sci. 2001;187(suppl 1):S108.

2. Booij HA, Hamburger HL, Jöbsis GJ, et al. Stroke mimicking conversion disorder: two young women who put our feet back on the ground. Pract Neurol. 2012;12(3):179-181.

3. Glick TH, Workman TP, Gaufberg SV. Suspected conversion disorder: foreseeable risks and avoidable errors. Acad Emerg Med. 2000;7(11):1272-1277.

4. Fishbain DA, Goldberg M. The misdiagnosis of conversion disorder in a psychiatric emergency service. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1991;13(3):177-181.

5. Carlson ML, Archibald DJ, Gifford RH, et al. Conversion disorder: a missed diagnosis leading to cochlear reimplantation. Otol Neurotol. 2011;32(1):36-38.

6. Sar V, Akyüz G, Kundakçi T, et al. Childhood trauma, dissociation, and psychiatric comorbidity in patients with conversion disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161(12):2271-2276.

7. de Waal MW, Arnold IA, Eekhof JA, et al. Somatoform disorders in general practice: prevalence, functional impairment and comorbidity with anxiety and depressive disorders. Br J Psychiatry. 2004;184:470-476.

8. Nicholson TR, Stone J, Kanaan RA. Conversion disorder: a problematic diagnosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2011;82(11):1267-1273.

9. Stone J, LaFrance WC, Jr, Levenson JL, et al. Issues for

DSM-5: conversion disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167(6): 626-627.

10. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

11. Voon V, Gallea C, Hattori N, et al. The involuntary nature of conversion disorder. Neurology. 2010;74(3):223-228.

12. Stone J, Zeman A, Sharpe M. Functional weakness and sensory disturbance. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2002; 73:241-245.

13. Aybek S, Kanaan RA, David AS. The neuropsychiatry of conversion disorder. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2008;21(3):275-280.

14. Kroenke K. Efficacy of treatment for somatoform disorders: a review of randomized controlled trials. Psychosom Med. 2007;69(9):881-888.

15. Sharpe M, Walker J, Williams C, et al. Guided self-help for functional (psychogenic) symptoms: a randomized controlled efficacy trial. Neurology. 2011;77(6):564-572.

1. Diukova GM, Stolajrova AV, Vein AM. Sternocleidomastoid (SCM) muscle test in patients with hysterical and organic paresis. J Neurol Sci. 2001;187(suppl 1):S108.

2. Booij HA, Hamburger HL, Jöbsis GJ, et al. Stroke mimicking conversion disorder: two young women who put our feet back on the ground. Pract Neurol. 2012;12(3):179-181.

3. Glick TH, Workman TP, Gaufberg SV. Suspected conversion disorder: foreseeable risks and avoidable errors. Acad Emerg Med. 2000;7(11):1272-1277.

4. Fishbain DA, Goldberg M. The misdiagnosis of conversion disorder in a psychiatric emergency service. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1991;13(3):177-181.

5. Carlson ML, Archibald DJ, Gifford RH, et al. Conversion disorder: a missed diagnosis leading to cochlear reimplantation. Otol Neurotol. 2011;32(1):36-38.

6. Sar V, Akyüz G, Kundakçi T, et al. Childhood trauma, dissociation, and psychiatric comorbidity in patients with conversion disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161(12):2271-2276.

7. de Waal MW, Arnold IA, Eekhof JA, et al. Somatoform disorders in general practice: prevalence, functional impairment and comorbidity with anxiety and depressive disorders. Br J Psychiatry. 2004;184:470-476.

8. Nicholson TR, Stone J, Kanaan RA. Conversion disorder: a problematic diagnosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2011;82(11):1267-1273.

9. Stone J, LaFrance WC, Jr, Levenson JL, et al. Issues for

DSM-5: conversion disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167(6): 626-627.

10. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

11. Voon V, Gallea C, Hattori N, et al. The involuntary nature of conversion disorder. Neurology. 2010;74(3):223-228.

12. Stone J, Zeman A, Sharpe M. Functional weakness and sensory disturbance. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2002; 73:241-245.

13. Aybek S, Kanaan RA, David AS. The neuropsychiatry of conversion disorder. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2008;21(3):275-280.

14. Kroenke K. Efficacy of treatment for somatoform disorders: a review of randomized controlled trials. Psychosom Med. 2007;69(9):881-888.

15. Sharpe M, Walker J, Williams C, et al. Guided self-help for functional (psychogenic) symptoms: a randomized controlled efficacy trial. Neurology. 2011;77(6):564-572.