User login

A mood disorder complicated by multiple sclerosis

CASE Depression, or something else?

Ms. A, age 56, presents to the emergency department (ED) with depressed mood, poor sleep, anhedonia, irritability, agitation, and recent self-injurious behavior; she had superficially cut her wrists. She also has a longstanding history of multiple sclerosis (MS), depression, and anxiety. She is admitted voluntarily to an inpatient psychiatric unit.

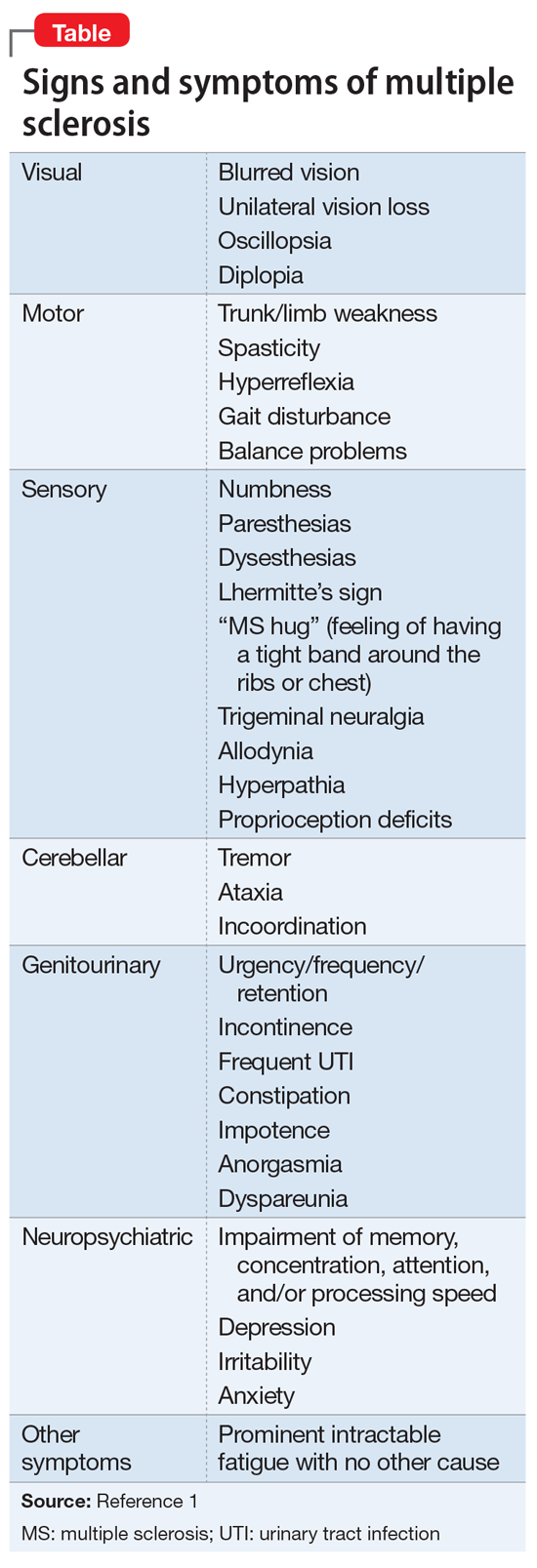

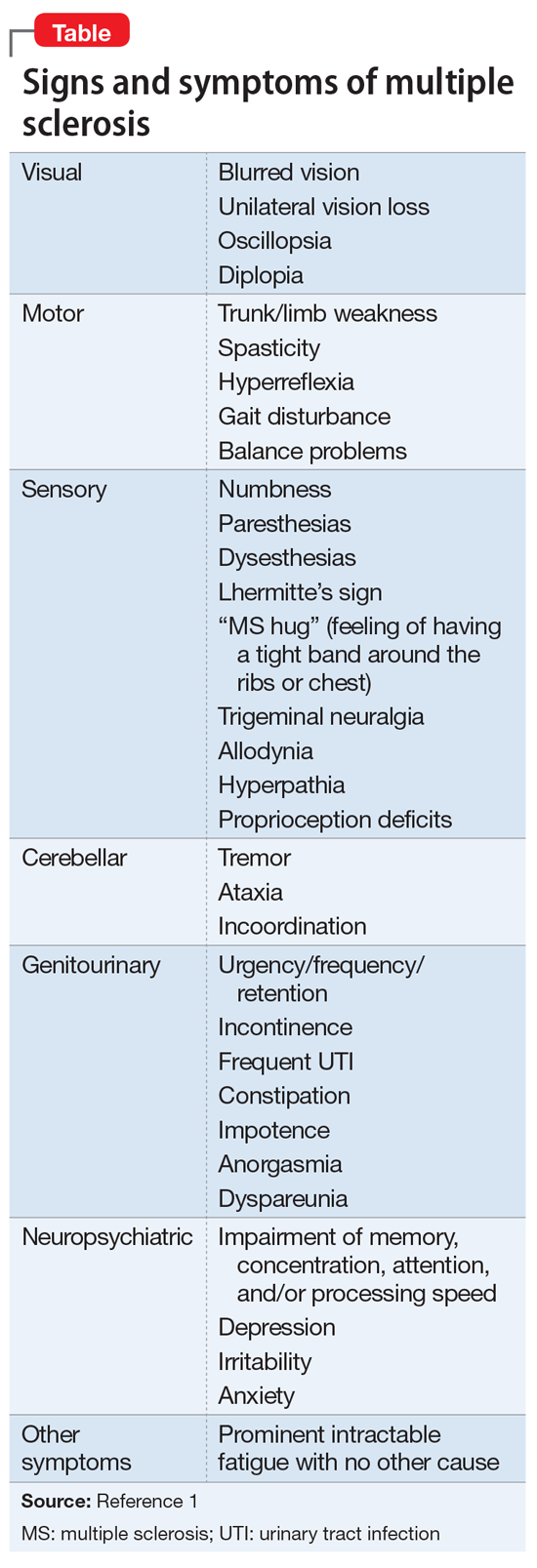

According to medical records, at age 32, Ms. A was diagnosed with relapsing-remitting MS, which initially presented with facial numbness, and later with optic neuritis with transient loss of vision. As her disease progressed to the secondary progressive type, she experienced spasticity and vertigo. In the past few years, she also had experienced cognitive difficulties, particularly with memory and focus.

Ms. A has a history of recurrent depressive symptoms that began at an unspecified time after being diagnosed with MS. In the past few years, she had greatly increased her alcohol use in response to multiple psychosocial stressors and as an attempt to self-medicate MS-related pain. Several years ago, Ms. A had been admitted to a rehabilitation facility to address her alcohol use.

In the past, Ms. A’s depressive symptoms had been treated with various antidepressants, including fluoxetine (unspecified dose), which for a time was effective. The most recently prescribed antidepressant was duloxetine, 60 mg/d, which was discontinued because Ms. A felt it activated her mood lability. A few years before this current hospitalization, Ms. A had been started on a trial of dextromethorphan/quinidine (20 mg/10 mg, twice daily), which was discontinued due to concomitant use of an unspecified serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI) and subsequent precipitation of serotonin syndrome.

At the time of this current admission to the psychiatric unit, Ms. A is being treated for MS with rituximab (10 mg/mL IV, every 6 months). Additionally, just before her admission, she was taking alprazolam (.25 mg, 3 times per day) for anxiety. She denies experiencing any spasticity or vision impairment.

[polldaddy:10175070]

The authors’ observations

We initially considered a diagnosis of MDD due to Ms. A’s past history of depressive episodes, her recent increase in tearfulness and anhedonia, and her self-injurious behaviors. However, diagnosis of a mood disorder was complicated by her complex history of longstanding MS and other psychosocial factors.

Continue to: Several factors contribute to the neuropsychiatric course of patients with MS...

Several factors contribute to the neuropsychiatric course of patients with MS, including the impact of the patient accepting a chronic and incurable diagnosis, the toll of progressive neurologic/physical disability and subsequent decline in functioning, and the availability of a support system.2 As opposed to disorders such as Parkinson’s disease, where disease progression is relatively more predictable, the culture of MS involves the obscurity of symptom fluctuation, both from the patient’s and/or clinician’s viewpoint. Psychiatric and neurologic symptoms may be difficult to predict, leading to speculation and projection as to the progression of the disease. The diagnosis of psychiatric conditions, such as depression, can be complicated by the fact that MS and psychiatric disorders share presenting symptoms; for example, disturbances in sleep and concentration may be seen in both conditions.

While studies have examined the neurobiology of MS lesions and their effects on mood symptoms, there has been no clear consensus of specific lesion distributions, although lesions in the superior frontal lobe and right temporal lobe regions have been identified in depressed MS patients.8 Lesions in the left frontal lobe may also have some contribution; studies have shown hyperintense lesion load in this area, which was found to be an independent predictor of MDD in MS.9 This, in turn, coincides with the association of left frontal cortex involvement in modulating affective depression, evidenced by studies that have associated depression severity with left frontal lobe damage in post-stroke patients10 as well as the use of transcranial magnetic stimulation of the left prefrontal cortex for treatment-resistant MDD.11 Lesions along the orbitofrontal prefrontal cortex have similarly been connected to mood lability and impulsivity, which are characteristics of bipolar disorder.8 Within the general population, bipolar disorder is associated with areas of hyperintensity on MRI, particularly in the frontal and parietal white matter, which may provide clues as to the role of MS demyelinating lesions in similar locations, although research concerning the relationship between MS and bipolar disorder remains limited.12

EVALUATION No exacerbation of MS

Upon admission, Ms. A’s lability of affect is apparent as she quickly switches from being tearful to bright depending on the topic of discussion. She smiles when talking about the hobbies she enjoys and becomes tearful when speaking of personal problems within her family. She denies suicidal ideation/intent, shows no evidence of psychosis, and denies any history of bipolar disorder or recollection of hypomanic/manic symptoms. Overall, she exhibits low energy and difficulty sleeping, and reiterates her various psychosocial stressors, including her family history of depression and ongoing marital conflicts. Ms. A denies experiencing any acute exacerbations of clinical neurologic features of MS immediately before or during her admission. Laboratory values are normal, except for an elevated thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) value of 11.136 uIU/mL, which is expected given her history of hypothyroidism. Results of the most recent brain MRI scans for Ms. A are pending.

The authors’ observations

Although we considered a diagnosis of bipolar disorder–mixed subtype, this was less likely to be the diagnosis considering her lack of any frank manic/hypomanic symptoms or history of such symptoms. Additionally, while we also considered a diagnosis of pseudobulbar affect due to her current mood swings and past trial of dextromethorphan/quinidine, this diagnosis was also less likely because Ms. A’s affect was not characterized by uncontrollable outbursts of emotion but was congruent with her experiences and surroundings. For example, Ms. A smiled when talking about her hobbies and became tearful when speaking of conflicts within her family.

Given Ms. A’s mood dysregulation and lability and her history of depressive episodes that began to manifest after her diagnosis of MS was established, and after ruling out other etiologic psychiatric disorders, a diagnosis of mood disorder secondary to MS was made.

[polldaddy:10175136]

Continue to: TREATMENT Mood stabilization

TREATMENT Mood stabilization

We start Ms. A on divalproex sodium, 250 mg 2 times a day, which is eventually titrated to 250 mg every morning with an additional daily 750 mg (total daily dose of 1,000 mg) for mood stabilization. Additionally, quetiapine, 50 mg nightly, is added and eventually titrated to 300 mg to augment mood stabilization and to aid sleep. Before being admitted, Ms. A had been prescribed

The authors’ observations

Definitive treatments for psychiatric conditions in patients with MS have been lacking, and current recommendations are based on regimens used to treat general psychiatric populations. For example, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors are frequently considered for treatment of MDD in patients with MS, whereas SNRIs are considered for patients with concomitant neuropathic pain.13 Similarly,

OUTCOME Improved mood, energy

After 2 weeks of inpatient treatment, Ms. A shows improvement in mood lability and energy levels, and she is able to tolerate titration of divalproex sodium and quetiapine to therapeutic levels. She is referred to an outpatient psychiatrist after discharge, as well as a follow-up appointment with her neurologist. On discharge, Ms. A expresses a commitment to treatment and hope for the future.

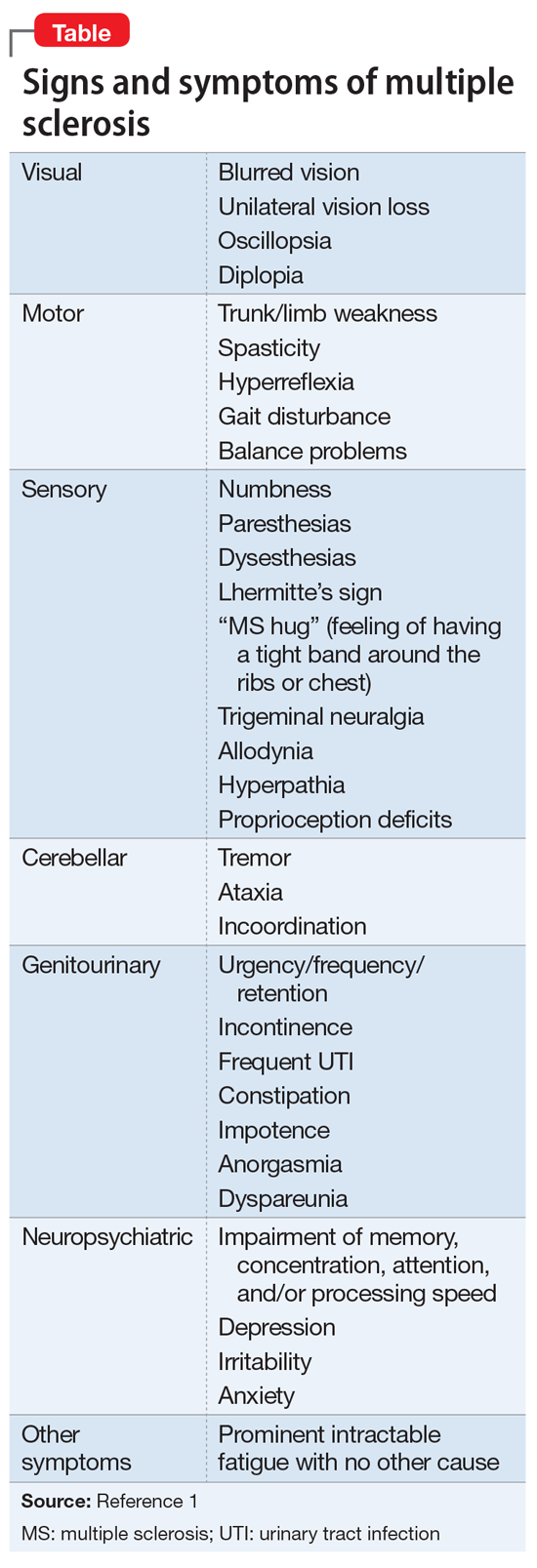

1. National Multiple Sclerosis Society. Signs and symptoms consistent with demyelinating disease (for professionals). https://www.nationalmssociety.org/For-Professionals/Clinical-Care/Diagnosing-MS/Signs-and-Symptoms-Consistent-with-Demyelinating-D. Accessed October 29, 2018.

2. Politte LC, Huffman JC, Stern TA. Neuropsychiatric manifestations of multiple sclerosis. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;10(4):318-324.

3. Siegert RJ, Abernethy D. Depression in multiple sclerosis: a review. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2005;76(4):469-475.

4. Scalfari A, Knappertz V, Cutter G, et al. Mortality in patients with multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2013;81(2):184-192.

5. Ghaffar O, Feinstein A. The neuropsychiatry of multiple sclerosis: a review of recent developments. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2007;20(3):278-285.

6. Duncan A, Malcolm-Smith S, Ameen O, et al. The incidence of euphoria in multiple sclerosis: artefact of measure. Mult Scler Int. 2016;2016:1-8.

7. Paparrigopoulos T, Ferentinos P, Kouzoupis A, et al. The neuropsychiatry of multiple sclerosis: focus on disorders of mood, affect and behaviour. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2010;22(1):14-21.

8. Bakshi R, Czarnecki D, Shaikh ZA, et al. Brain MRI lesions and atrophy are related to depression in multiple sclerosis. Neuroreport. 2000;11(6):1153-1158.

9. Feinstein A, Roy P, Lobaugh N, et al. Structural brain abnormalities in multiple sclerosis patients with major depression. Neurology. 2004;62(4):586-590.

10. Hama S, Yamashita H, Shigenobu M, et al. Post-stroke affective or apathetic depression and lesion location: left frontal lobe and bilateral basal ganglia. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2007;257(3):149-152.

11. Carpenter LL, Janicak PG, Aaronson ST, et al. Transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) for major depression: a multisite, naturalistic, observational study of acute treatment outcomes in clinical practice. Depress Anxiety. 2012;29(7):587-596.

12. Beyer JL, Young R, Kuchibhatla M, et al. Hyperintense MRI lesions in bipolar disorder: a meta-analysis and review. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2009;21(4):394-409.

13. Feinstein A. Neuropsychiatric syndromes associated with multiple sclerosis. J Neurol. 2007;254(S2):1173-1176.

14. Thomas PW, Thomas S, Hillier C, et al. Psychological interventions for multiple sclerosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;(1):CD004431. doi: 10.1002/14651858.cd004431.pub2.

CASE Depression, or something else?

Ms. A, age 56, presents to the emergency department (ED) with depressed mood, poor sleep, anhedonia, irritability, agitation, and recent self-injurious behavior; she had superficially cut her wrists. She also has a longstanding history of multiple sclerosis (MS), depression, and anxiety. She is admitted voluntarily to an inpatient psychiatric unit.

According to medical records, at age 32, Ms. A was diagnosed with relapsing-remitting MS, which initially presented with facial numbness, and later with optic neuritis with transient loss of vision. As her disease progressed to the secondary progressive type, she experienced spasticity and vertigo. In the past few years, she also had experienced cognitive difficulties, particularly with memory and focus.

Ms. A has a history of recurrent depressive symptoms that began at an unspecified time after being diagnosed with MS. In the past few years, she had greatly increased her alcohol use in response to multiple psychosocial stressors and as an attempt to self-medicate MS-related pain. Several years ago, Ms. A had been admitted to a rehabilitation facility to address her alcohol use.

In the past, Ms. A’s depressive symptoms had been treated with various antidepressants, including fluoxetine (unspecified dose), which for a time was effective. The most recently prescribed antidepressant was duloxetine, 60 mg/d, which was discontinued because Ms. A felt it activated her mood lability. A few years before this current hospitalization, Ms. A had been started on a trial of dextromethorphan/quinidine (20 mg/10 mg, twice daily), which was discontinued due to concomitant use of an unspecified serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI) and subsequent precipitation of serotonin syndrome.

At the time of this current admission to the psychiatric unit, Ms. A is being treated for MS with rituximab (10 mg/mL IV, every 6 months). Additionally, just before her admission, she was taking alprazolam (.25 mg, 3 times per day) for anxiety. She denies experiencing any spasticity or vision impairment.

[polldaddy:10175070]

The authors’ observations

We initially considered a diagnosis of MDD due to Ms. A’s past history of depressive episodes, her recent increase in tearfulness and anhedonia, and her self-injurious behaviors. However, diagnosis of a mood disorder was complicated by her complex history of longstanding MS and other psychosocial factors.

Continue to: Several factors contribute to the neuropsychiatric course of patients with MS...

Several factors contribute to the neuropsychiatric course of patients with MS, including the impact of the patient accepting a chronic and incurable diagnosis, the toll of progressive neurologic/physical disability and subsequent decline in functioning, and the availability of a support system.2 As opposed to disorders such as Parkinson’s disease, where disease progression is relatively more predictable, the culture of MS involves the obscurity of symptom fluctuation, both from the patient’s and/or clinician’s viewpoint. Psychiatric and neurologic symptoms may be difficult to predict, leading to speculation and projection as to the progression of the disease. The diagnosis of psychiatric conditions, such as depression, can be complicated by the fact that MS and psychiatric disorders share presenting symptoms; for example, disturbances in sleep and concentration may be seen in both conditions.

While studies have examined the neurobiology of MS lesions and their effects on mood symptoms, there has been no clear consensus of specific lesion distributions, although lesions in the superior frontal lobe and right temporal lobe regions have been identified in depressed MS patients.8 Lesions in the left frontal lobe may also have some contribution; studies have shown hyperintense lesion load in this area, which was found to be an independent predictor of MDD in MS.9 This, in turn, coincides with the association of left frontal cortex involvement in modulating affective depression, evidenced by studies that have associated depression severity with left frontal lobe damage in post-stroke patients10 as well as the use of transcranial magnetic stimulation of the left prefrontal cortex for treatment-resistant MDD.11 Lesions along the orbitofrontal prefrontal cortex have similarly been connected to mood lability and impulsivity, which are characteristics of bipolar disorder.8 Within the general population, bipolar disorder is associated with areas of hyperintensity on MRI, particularly in the frontal and parietal white matter, which may provide clues as to the role of MS demyelinating lesions in similar locations, although research concerning the relationship between MS and bipolar disorder remains limited.12

EVALUATION No exacerbation of MS

Upon admission, Ms. A’s lability of affect is apparent as she quickly switches from being tearful to bright depending on the topic of discussion. She smiles when talking about the hobbies she enjoys and becomes tearful when speaking of personal problems within her family. She denies suicidal ideation/intent, shows no evidence of psychosis, and denies any history of bipolar disorder or recollection of hypomanic/manic symptoms. Overall, she exhibits low energy and difficulty sleeping, and reiterates her various psychosocial stressors, including her family history of depression and ongoing marital conflicts. Ms. A denies experiencing any acute exacerbations of clinical neurologic features of MS immediately before or during her admission. Laboratory values are normal, except for an elevated thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) value of 11.136 uIU/mL, which is expected given her history of hypothyroidism. Results of the most recent brain MRI scans for Ms. A are pending.

The authors’ observations

Although we considered a diagnosis of bipolar disorder–mixed subtype, this was less likely to be the diagnosis considering her lack of any frank manic/hypomanic symptoms or history of such symptoms. Additionally, while we also considered a diagnosis of pseudobulbar affect due to her current mood swings and past trial of dextromethorphan/quinidine, this diagnosis was also less likely because Ms. A’s affect was not characterized by uncontrollable outbursts of emotion but was congruent with her experiences and surroundings. For example, Ms. A smiled when talking about her hobbies and became tearful when speaking of conflicts within her family.

Given Ms. A’s mood dysregulation and lability and her history of depressive episodes that began to manifest after her diagnosis of MS was established, and after ruling out other etiologic psychiatric disorders, a diagnosis of mood disorder secondary to MS was made.

[polldaddy:10175136]

Continue to: TREATMENT Mood stabilization

TREATMENT Mood stabilization

We start Ms. A on divalproex sodium, 250 mg 2 times a day, which is eventually titrated to 250 mg every morning with an additional daily 750 mg (total daily dose of 1,000 mg) for mood stabilization. Additionally, quetiapine, 50 mg nightly, is added and eventually titrated to 300 mg to augment mood stabilization and to aid sleep. Before being admitted, Ms. A had been prescribed

The authors’ observations

Definitive treatments for psychiatric conditions in patients with MS have been lacking, and current recommendations are based on regimens used to treat general psychiatric populations. For example, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors are frequently considered for treatment of MDD in patients with MS, whereas SNRIs are considered for patients with concomitant neuropathic pain.13 Similarly,

OUTCOME Improved mood, energy

After 2 weeks of inpatient treatment, Ms. A shows improvement in mood lability and energy levels, and she is able to tolerate titration of divalproex sodium and quetiapine to therapeutic levels. She is referred to an outpatient psychiatrist after discharge, as well as a follow-up appointment with her neurologist. On discharge, Ms. A expresses a commitment to treatment and hope for the future.

CASE Depression, or something else?

Ms. A, age 56, presents to the emergency department (ED) with depressed mood, poor sleep, anhedonia, irritability, agitation, and recent self-injurious behavior; she had superficially cut her wrists. She also has a longstanding history of multiple sclerosis (MS), depression, and anxiety. She is admitted voluntarily to an inpatient psychiatric unit.

According to medical records, at age 32, Ms. A was diagnosed with relapsing-remitting MS, which initially presented with facial numbness, and later with optic neuritis with transient loss of vision. As her disease progressed to the secondary progressive type, she experienced spasticity and vertigo. In the past few years, she also had experienced cognitive difficulties, particularly with memory and focus.

Ms. A has a history of recurrent depressive symptoms that began at an unspecified time after being diagnosed with MS. In the past few years, she had greatly increased her alcohol use in response to multiple psychosocial stressors and as an attempt to self-medicate MS-related pain. Several years ago, Ms. A had been admitted to a rehabilitation facility to address her alcohol use.

In the past, Ms. A’s depressive symptoms had been treated with various antidepressants, including fluoxetine (unspecified dose), which for a time was effective. The most recently prescribed antidepressant was duloxetine, 60 mg/d, which was discontinued because Ms. A felt it activated her mood lability. A few years before this current hospitalization, Ms. A had been started on a trial of dextromethorphan/quinidine (20 mg/10 mg, twice daily), which was discontinued due to concomitant use of an unspecified serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI) and subsequent precipitation of serotonin syndrome.

At the time of this current admission to the psychiatric unit, Ms. A is being treated for MS with rituximab (10 mg/mL IV, every 6 months). Additionally, just before her admission, she was taking alprazolam (.25 mg, 3 times per day) for anxiety. She denies experiencing any spasticity or vision impairment.

[polldaddy:10175070]

The authors’ observations

We initially considered a diagnosis of MDD due to Ms. A’s past history of depressive episodes, her recent increase in tearfulness and anhedonia, and her self-injurious behaviors. However, diagnosis of a mood disorder was complicated by her complex history of longstanding MS and other psychosocial factors.

Continue to: Several factors contribute to the neuropsychiatric course of patients with MS...

Several factors contribute to the neuropsychiatric course of patients with MS, including the impact of the patient accepting a chronic and incurable diagnosis, the toll of progressive neurologic/physical disability and subsequent decline in functioning, and the availability of a support system.2 As opposed to disorders such as Parkinson’s disease, where disease progression is relatively more predictable, the culture of MS involves the obscurity of symptom fluctuation, both from the patient’s and/or clinician’s viewpoint. Psychiatric and neurologic symptoms may be difficult to predict, leading to speculation and projection as to the progression of the disease. The diagnosis of psychiatric conditions, such as depression, can be complicated by the fact that MS and psychiatric disorders share presenting symptoms; for example, disturbances in sleep and concentration may be seen in both conditions.

While studies have examined the neurobiology of MS lesions and their effects on mood symptoms, there has been no clear consensus of specific lesion distributions, although lesions in the superior frontal lobe and right temporal lobe regions have been identified in depressed MS patients.8 Lesions in the left frontal lobe may also have some contribution; studies have shown hyperintense lesion load in this area, which was found to be an independent predictor of MDD in MS.9 This, in turn, coincides with the association of left frontal cortex involvement in modulating affective depression, evidenced by studies that have associated depression severity with left frontal lobe damage in post-stroke patients10 as well as the use of transcranial magnetic stimulation of the left prefrontal cortex for treatment-resistant MDD.11 Lesions along the orbitofrontal prefrontal cortex have similarly been connected to mood lability and impulsivity, which are characteristics of bipolar disorder.8 Within the general population, bipolar disorder is associated with areas of hyperintensity on MRI, particularly in the frontal and parietal white matter, which may provide clues as to the role of MS demyelinating lesions in similar locations, although research concerning the relationship between MS and bipolar disorder remains limited.12

EVALUATION No exacerbation of MS

Upon admission, Ms. A’s lability of affect is apparent as she quickly switches from being tearful to bright depending on the topic of discussion. She smiles when talking about the hobbies she enjoys and becomes tearful when speaking of personal problems within her family. She denies suicidal ideation/intent, shows no evidence of psychosis, and denies any history of bipolar disorder or recollection of hypomanic/manic symptoms. Overall, she exhibits low energy and difficulty sleeping, and reiterates her various psychosocial stressors, including her family history of depression and ongoing marital conflicts. Ms. A denies experiencing any acute exacerbations of clinical neurologic features of MS immediately before or during her admission. Laboratory values are normal, except for an elevated thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) value of 11.136 uIU/mL, which is expected given her history of hypothyroidism. Results of the most recent brain MRI scans for Ms. A are pending.

The authors’ observations

Although we considered a diagnosis of bipolar disorder–mixed subtype, this was less likely to be the diagnosis considering her lack of any frank manic/hypomanic symptoms or history of such symptoms. Additionally, while we also considered a diagnosis of pseudobulbar affect due to her current mood swings and past trial of dextromethorphan/quinidine, this diagnosis was also less likely because Ms. A’s affect was not characterized by uncontrollable outbursts of emotion but was congruent with her experiences and surroundings. For example, Ms. A smiled when talking about her hobbies and became tearful when speaking of conflicts within her family.

Given Ms. A’s mood dysregulation and lability and her history of depressive episodes that began to manifest after her diagnosis of MS was established, and after ruling out other etiologic psychiatric disorders, a diagnosis of mood disorder secondary to MS was made.

[polldaddy:10175136]

Continue to: TREATMENT Mood stabilization

TREATMENT Mood stabilization

We start Ms. A on divalproex sodium, 250 mg 2 times a day, which is eventually titrated to 250 mg every morning with an additional daily 750 mg (total daily dose of 1,000 mg) for mood stabilization. Additionally, quetiapine, 50 mg nightly, is added and eventually titrated to 300 mg to augment mood stabilization and to aid sleep. Before being admitted, Ms. A had been prescribed

The authors’ observations

Definitive treatments for psychiatric conditions in patients with MS have been lacking, and current recommendations are based on regimens used to treat general psychiatric populations. For example, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors are frequently considered for treatment of MDD in patients with MS, whereas SNRIs are considered for patients with concomitant neuropathic pain.13 Similarly,

OUTCOME Improved mood, energy

After 2 weeks of inpatient treatment, Ms. A shows improvement in mood lability and energy levels, and she is able to tolerate titration of divalproex sodium and quetiapine to therapeutic levels. She is referred to an outpatient psychiatrist after discharge, as well as a follow-up appointment with her neurologist. On discharge, Ms. A expresses a commitment to treatment and hope for the future.

1. National Multiple Sclerosis Society. Signs and symptoms consistent with demyelinating disease (for professionals). https://www.nationalmssociety.org/For-Professionals/Clinical-Care/Diagnosing-MS/Signs-and-Symptoms-Consistent-with-Demyelinating-D. Accessed October 29, 2018.

2. Politte LC, Huffman JC, Stern TA. Neuropsychiatric manifestations of multiple sclerosis. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;10(4):318-324.

3. Siegert RJ, Abernethy D. Depression in multiple sclerosis: a review. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2005;76(4):469-475.

4. Scalfari A, Knappertz V, Cutter G, et al. Mortality in patients with multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2013;81(2):184-192.

5. Ghaffar O, Feinstein A. The neuropsychiatry of multiple sclerosis: a review of recent developments. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2007;20(3):278-285.

6. Duncan A, Malcolm-Smith S, Ameen O, et al. The incidence of euphoria in multiple sclerosis: artefact of measure. Mult Scler Int. 2016;2016:1-8.

7. Paparrigopoulos T, Ferentinos P, Kouzoupis A, et al. The neuropsychiatry of multiple sclerosis: focus on disorders of mood, affect and behaviour. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2010;22(1):14-21.

8. Bakshi R, Czarnecki D, Shaikh ZA, et al. Brain MRI lesions and atrophy are related to depression in multiple sclerosis. Neuroreport. 2000;11(6):1153-1158.

9. Feinstein A, Roy P, Lobaugh N, et al. Structural brain abnormalities in multiple sclerosis patients with major depression. Neurology. 2004;62(4):586-590.

10. Hama S, Yamashita H, Shigenobu M, et al. Post-stroke affective or apathetic depression and lesion location: left frontal lobe and bilateral basal ganglia. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2007;257(3):149-152.

11. Carpenter LL, Janicak PG, Aaronson ST, et al. Transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) for major depression: a multisite, naturalistic, observational study of acute treatment outcomes in clinical practice. Depress Anxiety. 2012;29(7):587-596.

12. Beyer JL, Young R, Kuchibhatla M, et al. Hyperintense MRI lesions in bipolar disorder: a meta-analysis and review. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2009;21(4):394-409.

13. Feinstein A. Neuropsychiatric syndromes associated with multiple sclerosis. J Neurol. 2007;254(S2):1173-1176.

14. Thomas PW, Thomas S, Hillier C, et al. Psychological interventions for multiple sclerosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;(1):CD004431. doi: 10.1002/14651858.cd004431.pub2.

1. National Multiple Sclerosis Society. Signs and symptoms consistent with demyelinating disease (for professionals). https://www.nationalmssociety.org/For-Professionals/Clinical-Care/Diagnosing-MS/Signs-and-Symptoms-Consistent-with-Demyelinating-D. Accessed October 29, 2018.

2. Politte LC, Huffman JC, Stern TA. Neuropsychiatric manifestations of multiple sclerosis. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;10(4):318-324.

3. Siegert RJ, Abernethy D. Depression in multiple sclerosis: a review. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2005;76(4):469-475.

4. Scalfari A, Knappertz V, Cutter G, et al. Mortality in patients with multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2013;81(2):184-192.

5. Ghaffar O, Feinstein A. The neuropsychiatry of multiple sclerosis: a review of recent developments. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2007;20(3):278-285.

6. Duncan A, Malcolm-Smith S, Ameen O, et al. The incidence of euphoria in multiple sclerosis: artefact of measure. Mult Scler Int. 2016;2016:1-8.

7. Paparrigopoulos T, Ferentinos P, Kouzoupis A, et al. The neuropsychiatry of multiple sclerosis: focus on disorders of mood, affect and behaviour. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2010;22(1):14-21.

8. Bakshi R, Czarnecki D, Shaikh ZA, et al. Brain MRI lesions and atrophy are related to depression in multiple sclerosis. Neuroreport. 2000;11(6):1153-1158.

9. Feinstein A, Roy P, Lobaugh N, et al. Structural brain abnormalities in multiple sclerosis patients with major depression. Neurology. 2004;62(4):586-590.

10. Hama S, Yamashita H, Shigenobu M, et al. Post-stroke affective or apathetic depression and lesion location: left frontal lobe and bilateral basal ganglia. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2007;257(3):149-152.

11. Carpenter LL, Janicak PG, Aaronson ST, et al. Transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) for major depression: a multisite, naturalistic, observational study of acute treatment outcomes in clinical practice. Depress Anxiety. 2012;29(7):587-596.

12. Beyer JL, Young R, Kuchibhatla M, et al. Hyperintense MRI lesions in bipolar disorder: a meta-analysis and review. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2009;21(4):394-409.

13. Feinstein A. Neuropsychiatric syndromes associated with multiple sclerosis. J Neurol. 2007;254(S2):1173-1176.

14. Thomas PW, Thomas S, Hillier C, et al. Psychological interventions for multiple sclerosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;(1):CD004431. doi: 10.1002/14651858.cd004431.pub2.

Depression in older adults: How to treat its distinct clinical manifestations

Discuss this article at http://currentpsychiatry.blogspot.com/2010/08/depression-in-older-adults.html#comments

Depression in older adults (age ≥65) can devastate their quality of life and increase the likelihood of institutionalization because of behavioral problems.1 Depression is a primary risk factor for suicide, and suicide rates are highest among those age ≥65, especially among white males.2 The burden of geriatric depression can extend to caregivers.1 Prompt recognition and treatment of depression could help minimize morbidity and reduce suffering in older adults and their caregivers.

Although geriatric depression varies in severity and presentation, common categories include:

- major depressive disorder (MDD)

- vascular depression

- dysthymia

- depression in the context of dementias, psychosis, bipolar disorder, and executive dysfunction.

Diagnoses in this population generally correspond with DSM-IV-TR criteria, but geriatric depression has distinct clinical manifestations.1,2 Compared with younger depressed patients, older adults are less likely to endorse depressed mood and more likely to report a lack of emotions.1,2 Older patients report feelings of irritability and fearfulness more often than sadness.1,2 Mood symptoms tend to be transient, reoccur frequently, and display either a diurnal pattern or multiple fluctuations in a single day.1,2 Other common presentations include loss of interest in usual activities, lack of motivation, social withdrawal, and decline in activities of daily living.1,2

Summary of recommendations

Age-specific recommendations for assessing and treating geriatric depression can be generated in part from evidence-based reviews, meta-analyses,3 and geriatric expert consensus guidelines.4 Such guidelines and recommendations often do not take into account the marked heterogeneity of medical, cognitive, and overall functioning in patients age ≥65, however, because they are based on studies of younger populations and patients with complicated issues often are excluded from studies. The recommendations in this article are based largely on findings from a National Institutes of Health (NIH)-sponsored project by Alexopoulos et al to develop consensus guidelines for managing geriatric depression and expert opinion from clinicians who treat geriatric patients.4

During your initial clinical evaluation, confirm the diagnosis and type, duration, and severity of depression. Seek to understand the biopsychosocial context of each patient’s presentation. Carefully consider your patient’s suicide risk. Hospitalization may be required if he or she is at high risk for suicide or has complex medical and social circumstances that cannot be managed adequately in an outpatient setting.5

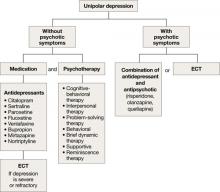

Unipolar major depression

For unipolar, nonpsychotic geriatric depression, the NIH-Alexopoulos et al guidelines emphasize a combination of antidepressants and psychotherapy (Algorithm 1).4 Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and venlafaxine are first-line options.4,6,7 Tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), bupropion, and mirtazapine are alternatives.4 Among SSRIs, citalopram, escitalopram, and sertraline are preferred initial antidepressants. Fluoxetine is used less frequently.4 Paroxetine also is less commonly used because of its anticholinergic effects and because the drug inhibits cytochrome P4502D6,2 which metabolizes several medications commonly prescribed for older adults. Among TCAs, nortriptyline is preferred.4 Studies have shown that duloxetine improves depression and is safe and well-tolerated in older adults with recurrent MDD.8 Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) is an option for treating severe or treatment-resistant unipolar major depression.9

For unipolar depression with psychotic symptoms, guidelines recommend a combination of an antidepressant and an antipsychotic or ECT.4 Atypical antipsychotics are preferred over typical antipsychotics4; risperidone, olanzapine, and quetiapine are most frequently used.4 Clinical data on aripiprazole and ziprasidone in older adults are limited. Many geriatric experts recommend continuing an antipsychotic for 6 months after symptom remission, then gradually tapering the dose.4

During acute illness, administer an anti-depressant for 6 to 12 weeks at the individually determined dose required to achieve symptom remission.6 For an older adult experiencing a first lifetime episode of major depression, continue antidepressant treatment for 1 year after remission.4 If your patient has had 2 lifetime episodes of major depression, continue the antidepressant at the same dose used to achieve remission for at least 3 years. For patients who have had ≥3 episodes of depression or whose index episode was particularly severe or involved significant suicidal thoughts or behaviors, continue maintenance treatment indefinitely.

Algorithm 1: Treatment for unipolar depression in geriatric patients

ECT: electroconvulsive therapy

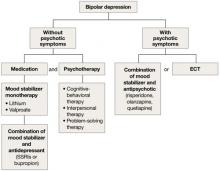

Bipolar depression

Mood stabilizers such as lithium or valproate—as monotherapy or in combination with an antidepressant—are recommended to treat bipolar depression without psychotic symptoms in older adults (Algorithm 2).10 For bipolar depression with psychotic symptoms, a combination of a mood stabilizer and an atypical antipsychotic or ECT is recommended.10

Older adults’ increased sensitivity to side effects and reduced ability to tolerate lithium may limit its use and may prompt you to consider atypical antipsychotics as alternatives to other mood stabilizers. Although quetiapine and fluoxetineolanzapine combination are well studied in younger patients,11,12 there is a lack of data to support their clinical effectiveness and tolerability in older adults. Among antidepressants, SSRIs or bupropion are preferred over TCAs to prevent a switch to mania.10 Lamotrigine is an effective maintenance treatment for bipolar depressive episodes in older adults.13

Although optimal mood stabilizer and antidepressant dosing for this population has not been adequately assessed, pharmacotherapy that has been effective generally should be continued without modification for at least 6 to 12 months.10 After the patient achieves remission, gradually discontinue antidepressants while maintaining the mood stabilizer.10

Algorithm 2: Bipolar depression: Options for combination therapy

ECT: electroconvulsive therapy; SSRIs: selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors

Depression in dementia

Managing depression in dementia patients is similar to treatment in older adults without dementia,5,14 although pharmacologic agents must be carefully selected because of increased risk of side effects (Algorithm 3). American Psychiatric Association practice guidelines recommend considering antidepressants for depressed patients with dementia even if their mood disturbances do not meet DSM-IV-TR criteria for MDD.5

SSRIs’ lower side effect profile make them the preferred treatment; the selective serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI) venlafaxine is a second-line option.4,14 Avoid TCAs and other agents with anticholinergic side effects because of potential cardiovascular complications and cognitive side effects, unless SSRIs or SNRIs are ineffective or contraindicated.14 Recently clinicians have been reluctant to use antipsychotics in patients with dementia, because of the FDA’s “black-box” warning regarding the increased mortality risk associated with their use in this population.

When using ECT to treat depression in patients with dementia, the treatment protocol often is modified to twice-a-week, unilateral stimulus because of these patients’ increased risk of delirium.14 The safety of ECT to treat depression in patients with dementia has not been adequately assessed.14

Algorithm 3: Treating comorbid depression and dementia

ECT: electroconvulsive therapy; SNRI: selective serotoninnorepinephrine reuptake inhibitor; SSRI: selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor

Vascular depression

The “vascular depression hypothesis” proposes that accumulation of subcortical white matter hyperintensities can disrupt frontostriatal pathways, resulting in depressive symptoms.15 This hypothesis is supported by the confluence of depression and vascular risk factors.15 Sertraline, citalopram, nortriptyline,16 and trazodone15 have been shown to reduce depressive symptoms after a stroke.

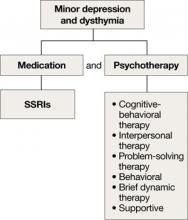

Minor depression and dysthymia

Although the efficacy of antidepressants in minor depression—depression that does not meet criteria for MDD—is not well established, expert consensus guidelines recommend SSRIs and psychotherapy, separately or in combination, for minor depression and dysthymia in older adults (Algorithm 4).4 Depression in executive dysfunction responds poorly to SSRI treatment2; however, behaviorally oriented psychotherapeutic interventions such as problem-solving therapy (PST) show promise.2

Algorithm 4: Minor depression: SSRIs plus psychotherapy

SSRIs: selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors

Comorbid medical conditions

When an older adult has a medical problem that likely contributes to depression—such as hypothyroidism—treat the condition and prescribe antidepressants simultaneously.2 However, if the medical problem likely causes depression—such as substance withdrawal—treat the condition first and prescribe antidepressants only if mood symptoms persist.2

Refractory depression

If your patient does not respond to an antidepressant trial of adequate dosage and duration, first make sure he or she is taking it correctly (Algorithm 5). After ruling out poor adherence, screen for comorbid psychiatric or medical conditions or psychosocial stressors and reassess the principal diagnosis.5

If these steps don’t address your patient’s depressive symptoms, expert consensus guidelines suggest switching to a different antidepressant:4

- If you first prescribed an SSRI, consider venlafaxine XR or bupropion SR.4,17

- If your patient initially received a TCA or bupropion, an SSRI or venlafaxine XR would be appropriate.4

- If venlafaxine XR was the first antidepressant, a SSRI is recommended.4

If your patient experienced a partial response but not full remission with the initial antidepressant, consider adding a second antidepressant or an augmenting agent:4

- If your patient first received an SSRI, adding bupropion, lithium, or nortriptyline is recommended.

- If the initial antidepressant was a TCA or bupropion, consider adding lithium or an SSRI.

- Augmenting venlafaxine XR with lithium is recommended.4

The National Institutes of Mental Health-sponsored Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression (STAR*D) study of treatment-resistant depression in mixed-age groups reported that patients who do not attain remission with an initial SSRI may respond to switching to bupropion SR or venlafaxine XR.17 Augmenting an SSRI with bupropion SR has been shown to be effective.18 In addition, consider mirtazapine augmentation,19 especially if your patient experiences insomnia or anorexia. A combination of mirtazapine and venlafaxine have better efficacy and tolerability compared with the monoamine oxidase inhibitor tranylcypromine.19 Some studies have shown augmenting SSRIs with buspirone in patients with severe depression is efficacious and safe in younger adults,20 but this practice is not well studied in older patients.

Algorithm 5: Treatment-resistant geriatric depression: Partial vs no response

SNRI: selective serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor; SSRI: selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor; TCA: tricyclic antidepressant

Nonpharmacologic treatments

ECT is an important therapeutic intervention because of its safety, efficacy, and faster clinical response.6,7,9,21 Consider ECT for older adults with severe or psychotic major depression, acute suicidality, catatonia, or severe malnutrition caused by refusal to eat. Patients who remain significantly symptomatic after multiple medication trials, do not tolerate medications well, or have comorbid medical conditions that preclude antidepressant use also are potential candidates for ECT.5,22

ECT can be administered to many older depressed adults with relatively low complication rates. Pretreatment clinical and laboratory evaluations and consultation with medical colleagues may minimize the risk of adverse effects, including cardiovascular instability, delirium, and falls.9 Anterograde memory loss—a common concern for clinicians and patients—usually is temporary and can be reduced by modifying the ECT administration parameters, such as switching from bilateral to unilateral stimulus and spacing treatments.9 Use caution when considering ECT for patients with cardiovascular or neurologic conditions—such as myocardial infarction or cerebrovascular accident within 6 months of treatment—that may increase the risk of adverse effects. Some pharmacologic agents, such as benzodiazepines and anticonvulsant mood stabilizers, may decrease ECT’s efficacy by inhibiting seizure.22

Depressive relapse after ECT is a major clinical concern.21 Continuation ECT— within the first 6 months of remission— aims to prevent relapse of the same episode, whereas maintenance ECT—beyond the first 6 months—helps avert occurrence of new episodes.4,21 Relapse and recurrence also can be prevented with continuation or maintenance pharmacotherapy,4,21 which should be initiated immediately after the index course of ECT.21 Typically, ECT continuation/maintenance treatments are provided weekly, then gradually spaced out to once a month based on the minimum frequency that is effective for an individual patient.21

Psychotherapy for geriatric depression generally is effective.23 One-half of older patients prefer psychotherapy over pharmacotherapy.24 Efficacious psychotherapies include behavioral therapy, cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), PST, brief dynamic therapy, interpersonal therapy, supportive therapy, and reminiscence therapy.23 CBT has the most empiric support for treating geriatric depression.5,6

Psychotherapy alone is appropriate for mild-to-moderate depression, although severe depression requires adding medication.25 The combination of pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy appears to be more effective than either intervention alone in preventing recurrent major depression, especially when a specific psychosocial stressor has been identified.5,6 CBT, interpersonal therapy, and family-focused therapy enhance pharmacotherapy outcomes in bipolar disorder.13

The Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program for Bipolar Disorder (STEP-BD) study found that in mixed-age patients, pharmacotherapy plus psychotherapy is more beneficial than medication alone in stabilizing bipolar depression.26 For older adults with executive dysfunction, research suggests that PST is more effective than other psychotherapies.27 Psychosocial interventions—such as psychoeducation for the family and caregivers, family counseling, and participation in senior citizen centers and services—are strongly recommended for many patients.4

Related Resources

- Blazer DG, Steffens DC, Koenig HG. Mood disorders. In: Blazer DG, Steffens DC, eds. The American Psychiatric Publishing textbook of geriatric psychiatry. 4th ed. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc.; 2009:275-300.

- American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry. www.aagponline.org.

Drug Brand Names

- Aripiprazole • Abilify

- Bupropion • Wellbutrin, Zyban

- Buspirone • Buspar

- Citalopram • Celexa

- Duloxetine • Cymbalta

- Escitalopram • Lexapro

- Fluoxetine • Prozac

- Fluoxetine-olanzapine • Symbyax

- Lamotrigine • Lamictal

- Lithium • Eskalith, Lithobid

- Mirtazapine • Remeron

- Nortriptyline • Aventyl, Pamelor

- Olanzapine • Zyprexa

- Paroxetine • Paxil

- Quetiapine • Seroquel

- Risperidone • Risperdal

- Sertraline • Zoloft

- Tranylcypromine • Parnate

- Trazodone • Desyrel

- Valproate • Depakote

- Venlafaxine • Effexor

- Ziprasidone • Geodon

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationship with the manufacturer of any product mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Lyketsos CG, Lee HB. Diagnosis and treatment of depression in Alzheimer’s disease. A practical update for the clinician. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2004;17(1-2):55-64.

2. Alexopoulos G. Late-life mood disorders. In: Sadavoy J, Jarvik LF, Grossberg GT, et al, eds. Comprehensive textbook of geriatric psychiatry. 3rd ed. New York, NY: W.W. Norton and Company; 2004:609-653.

3. Shanmugham B, Karp J, Drayer R, et al. Evidence-based pharmacologic interventions of geriatric depression. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2005;28(4):821-835,viii.

4. Alexopoulos GS, Katz IR, Reynolds CF, III, et al. The expert consensus guidelines series. Pharmacotherapy of depressive disorders in older patients. Postgrad Med. 2001; Spect No Pharmacolotherapy:1–86.

5. American Psychiatric Association practice guidelines for the treatment of psychiatric disorders. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association; 2006:793–794.

6. Bartels SJ, Dums AR, Oxman TE, et al. Evidence-based practice in geriatric mental health care. Psychiatr Serv. 2002;53(11):1419-1431.

7. Bartels SJ, Dums AR, Oxman TE, et al. Evidence-based practices in geriatric mental health care: an overview of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2003;26(4):971-990,x–xi.

8. Raskin J, Wiltse CG, Siegal A, et al. Efficacy of duloxetine on cognition, depression, and pain in elderly patients with major depressive disorder: an 8-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164(6):900-909.

9. Alexopoulos GS, Young RC, Abrams RC. ECT in the high-risk geriatric patient. Convuls Ther. 1989;5(1):75-87.

10. Young RC, Gyulai L, Mulsant BH, et al. Pharmacotherapy of bipolar disorder in old age: review and recommendations. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2004;12:342-357.

11. Vieta E, Calabrese JR, Goikolea JM, et al. Quetiapine monotherapy in the treatment of patients with bipolar I or II depression and a rapid-cycling disease course: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Bipolar Disord. 2007;9(4):413-425.

12. Corya SA, Perlis RH, Keck PE, Jr, et al. A 24-week open-label extension study of olanzapine-fluoxetine combination and olanzapine monotherapy in the treatment of bipolar depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67(5):798-806.

13. Sajatovic M, Gyulai L, Calabrese JR, et al. Maintenance treatment outcomes in older patients with bipolar I disorder. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2005;13(4):305-311.

14. Lyketsos CG, Olin J. Depression in Alzheimer’s disease: overview and treatment. Biol Psychiatry. 2002;52(3):243-252.

15. Alexopoulos GS, Meyers BS, Young RC, et al. ‘Vascular depression’ hypothesis. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1997;54(10):915-922.

16. Starkstein SE, Mizrahi R, Power BD. Antidepressant therapy in post-stroke depression. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2008;9(8):1291-1298.

17. Rush AJ, Trivedi MH, Wisniewski SR, et al. and STAR*D Study Team. Bupropion-SR, sertraline, or venlafaxine-XR after failure of SSRIs for depression. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(12):1231-1242.

18. Trivedi MH, Fava M, Wisniewski SR, et al. and the STAR*D Study Team. Medication augmentation after the failure of SSRIs for depression. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(12):1243-1252.

19. McGrath PJ, Stewart JW, Fava M, et al. Tranylcypromine versus venlafaxine plus mirtazapine following three failed antidepressant medication trials for depression: a STAR*D report. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(9):1531-1541.

20. Appelberg BG, Syvälahti EK, Koskinen TE, et al. Patients with severe depression may benefit from buspirone augmentation of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors: results from a placebo-controlled, randomized, double-blind, placebo wash-in study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2001;62(6):448-452.

21. Greenberg RM, Kellner CH. Electroconvulsive therapy: a selected review. Am J Geriatric Psychiatry. 2005;13(4):268-281.

22. Kaplan HI, Sadock BJ. Electroconvulsive therapy. In: Kaplan and Sadock’s synopsis of psychiatry. 8th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 1998:1138–1143.

23. Gum A, Areán P. Current status of psychotherapy for mental disorders in the elderly. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2004;6:32-38.

24. Unützer J, Katon W, Callahan CM, et al. Collaborative care management of late-life depression in primary care settings: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2002;288:2836-2845.

25. Niederehe G, Schneider LS. Treatments for depression and anxiety in the aged. In: Nathan PE, Gorman JM, eds. A guide to treatments that work. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 1998:270–287.

26. Miklowitz DJ, Otto MW, Frank E, et al. Psychosocial treatments for bipolar depression: a 1-year randomized trial from the Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64:419-426.

27. Alexopoulos GS, Raue P, Areán P. Problem-solving therapy versus supportive therapy in geriatric major depression with executive dysfunction. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2003;11:46-52.

Discuss this article at http://currentpsychiatry.blogspot.com/2010/08/depression-in-older-adults.html#comments

Depression in older adults (age ≥65) can devastate their quality of life and increase the likelihood of institutionalization because of behavioral problems.1 Depression is a primary risk factor for suicide, and suicide rates are highest among those age ≥65, especially among white males.2 The burden of geriatric depression can extend to caregivers.1 Prompt recognition and treatment of depression could help minimize morbidity and reduce suffering in older adults and their caregivers.

Although geriatric depression varies in severity and presentation, common categories include:

- major depressive disorder (MDD)

- vascular depression

- dysthymia

- depression in the context of dementias, psychosis, bipolar disorder, and executive dysfunction.

Diagnoses in this population generally correspond with DSM-IV-TR criteria, but geriatric depression has distinct clinical manifestations.1,2 Compared with younger depressed patients, older adults are less likely to endorse depressed mood and more likely to report a lack of emotions.1,2 Older patients report feelings of irritability and fearfulness more often than sadness.1,2 Mood symptoms tend to be transient, reoccur frequently, and display either a diurnal pattern or multiple fluctuations in a single day.1,2 Other common presentations include loss of interest in usual activities, lack of motivation, social withdrawal, and decline in activities of daily living.1,2

Summary of recommendations

Age-specific recommendations for assessing and treating geriatric depression can be generated in part from evidence-based reviews, meta-analyses,3 and geriatric expert consensus guidelines.4 Such guidelines and recommendations often do not take into account the marked heterogeneity of medical, cognitive, and overall functioning in patients age ≥65, however, because they are based on studies of younger populations and patients with complicated issues often are excluded from studies. The recommendations in this article are based largely on findings from a National Institutes of Health (NIH)-sponsored project by Alexopoulos et al to develop consensus guidelines for managing geriatric depression and expert opinion from clinicians who treat geriatric patients.4

During your initial clinical evaluation, confirm the diagnosis and type, duration, and severity of depression. Seek to understand the biopsychosocial context of each patient’s presentation. Carefully consider your patient’s suicide risk. Hospitalization may be required if he or she is at high risk for suicide or has complex medical and social circumstances that cannot be managed adequately in an outpatient setting.5

Unipolar major depression

For unipolar, nonpsychotic geriatric depression, the NIH-Alexopoulos et al guidelines emphasize a combination of antidepressants and psychotherapy (Algorithm 1).4 Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and venlafaxine are first-line options.4,6,7 Tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), bupropion, and mirtazapine are alternatives.4 Among SSRIs, citalopram, escitalopram, and sertraline are preferred initial antidepressants. Fluoxetine is used less frequently.4 Paroxetine also is less commonly used because of its anticholinergic effects and because the drug inhibits cytochrome P4502D6,2 which metabolizes several medications commonly prescribed for older adults. Among TCAs, nortriptyline is preferred.4 Studies have shown that duloxetine improves depression and is safe and well-tolerated in older adults with recurrent MDD.8 Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) is an option for treating severe or treatment-resistant unipolar major depression.9

For unipolar depression with psychotic symptoms, guidelines recommend a combination of an antidepressant and an antipsychotic or ECT.4 Atypical antipsychotics are preferred over typical antipsychotics4; risperidone, olanzapine, and quetiapine are most frequently used.4 Clinical data on aripiprazole and ziprasidone in older adults are limited. Many geriatric experts recommend continuing an antipsychotic for 6 months after symptom remission, then gradually tapering the dose.4

During acute illness, administer an anti-depressant for 6 to 12 weeks at the individually determined dose required to achieve symptom remission.6 For an older adult experiencing a first lifetime episode of major depression, continue antidepressant treatment for 1 year after remission.4 If your patient has had 2 lifetime episodes of major depression, continue the antidepressant at the same dose used to achieve remission for at least 3 years. For patients who have had ≥3 episodes of depression or whose index episode was particularly severe or involved significant suicidal thoughts or behaviors, continue maintenance treatment indefinitely.

Algorithm 1: Treatment for unipolar depression in geriatric patients

ECT: electroconvulsive therapy

Bipolar depression

Mood stabilizers such as lithium or valproate—as monotherapy or in combination with an antidepressant—are recommended to treat bipolar depression without psychotic symptoms in older adults (Algorithm 2).10 For bipolar depression with psychotic symptoms, a combination of a mood stabilizer and an atypical antipsychotic or ECT is recommended.10

Older adults’ increased sensitivity to side effects and reduced ability to tolerate lithium may limit its use and may prompt you to consider atypical antipsychotics as alternatives to other mood stabilizers. Although quetiapine and fluoxetineolanzapine combination are well studied in younger patients,11,12 there is a lack of data to support their clinical effectiveness and tolerability in older adults. Among antidepressants, SSRIs or bupropion are preferred over TCAs to prevent a switch to mania.10 Lamotrigine is an effective maintenance treatment for bipolar depressive episodes in older adults.13

Although optimal mood stabilizer and antidepressant dosing for this population has not been adequately assessed, pharmacotherapy that has been effective generally should be continued without modification for at least 6 to 12 months.10 After the patient achieves remission, gradually discontinue antidepressants while maintaining the mood stabilizer.10

Algorithm 2: Bipolar depression: Options for combination therapy

ECT: electroconvulsive therapy; SSRIs: selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors

Depression in dementia

Managing depression in dementia patients is similar to treatment in older adults without dementia,5,14 although pharmacologic agents must be carefully selected because of increased risk of side effects (Algorithm 3). American Psychiatric Association practice guidelines recommend considering antidepressants for depressed patients with dementia even if their mood disturbances do not meet DSM-IV-TR criteria for MDD.5

SSRIs’ lower side effect profile make them the preferred treatment; the selective serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI) venlafaxine is a second-line option.4,14 Avoid TCAs and other agents with anticholinergic side effects because of potential cardiovascular complications and cognitive side effects, unless SSRIs or SNRIs are ineffective or contraindicated.14 Recently clinicians have been reluctant to use antipsychotics in patients with dementia, because of the FDA’s “black-box” warning regarding the increased mortality risk associated with their use in this population.

When using ECT to treat depression in patients with dementia, the treatment protocol often is modified to twice-a-week, unilateral stimulus because of these patients’ increased risk of delirium.14 The safety of ECT to treat depression in patients with dementia has not been adequately assessed.14

Algorithm 3: Treating comorbid depression and dementia

ECT: electroconvulsive therapy; SNRI: selective serotoninnorepinephrine reuptake inhibitor; SSRI: selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor

Vascular depression

The “vascular depression hypothesis” proposes that accumulation of subcortical white matter hyperintensities can disrupt frontostriatal pathways, resulting in depressive symptoms.15 This hypothesis is supported by the confluence of depression and vascular risk factors.15 Sertraline, citalopram, nortriptyline,16 and trazodone15 have been shown to reduce depressive symptoms after a stroke.

Minor depression and dysthymia

Although the efficacy of antidepressants in minor depression—depression that does not meet criteria for MDD—is not well established, expert consensus guidelines recommend SSRIs and psychotherapy, separately or in combination, for minor depression and dysthymia in older adults (Algorithm 4).4 Depression in executive dysfunction responds poorly to SSRI treatment2; however, behaviorally oriented psychotherapeutic interventions such as problem-solving therapy (PST) show promise.2

Algorithm 4: Minor depression: SSRIs plus psychotherapy

SSRIs: selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors

Comorbid medical conditions

When an older adult has a medical problem that likely contributes to depression—such as hypothyroidism—treat the condition and prescribe antidepressants simultaneously.2 However, if the medical problem likely causes depression—such as substance withdrawal—treat the condition first and prescribe antidepressants only if mood symptoms persist.2

Refractory depression

If your patient does not respond to an antidepressant trial of adequate dosage and duration, first make sure he or she is taking it correctly (Algorithm 5). After ruling out poor adherence, screen for comorbid psychiatric or medical conditions or psychosocial stressors and reassess the principal diagnosis.5

If these steps don’t address your patient’s depressive symptoms, expert consensus guidelines suggest switching to a different antidepressant:4

- If you first prescribed an SSRI, consider venlafaxine XR or bupropion SR.4,17

- If your patient initially received a TCA or bupropion, an SSRI or venlafaxine XR would be appropriate.4

- If venlafaxine XR was the first antidepressant, a SSRI is recommended.4

If your patient experienced a partial response but not full remission with the initial antidepressant, consider adding a second antidepressant or an augmenting agent:4

- If your patient first received an SSRI, adding bupropion, lithium, or nortriptyline is recommended.

- If the initial antidepressant was a TCA or bupropion, consider adding lithium or an SSRI.

- Augmenting venlafaxine XR with lithium is recommended.4

The National Institutes of Mental Health-sponsored Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression (STAR*D) study of treatment-resistant depression in mixed-age groups reported that patients who do not attain remission with an initial SSRI may respond to switching to bupropion SR or venlafaxine XR.17 Augmenting an SSRI with bupropion SR has been shown to be effective.18 In addition, consider mirtazapine augmentation,19 especially if your patient experiences insomnia or anorexia. A combination of mirtazapine and venlafaxine have better efficacy and tolerability compared with the monoamine oxidase inhibitor tranylcypromine.19 Some studies have shown augmenting SSRIs with buspirone in patients with severe depression is efficacious and safe in younger adults,20 but this practice is not well studied in older patients.

Algorithm 5: Treatment-resistant geriatric depression: Partial vs no response

SNRI: selective serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor; SSRI: selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor; TCA: tricyclic antidepressant

Nonpharmacologic treatments

ECT is an important therapeutic intervention because of its safety, efficacy, and faster clinical response.6,7,9,21 Consider ECT for older adults with severe or psychotic major depression, acute suicidality, catatonia, or severe malnutrition caused by refusal to eat. Patients who remain significantly symptomatic after multiple medication trials, do not tolerate medications well, or have comorbid medical conditions that preclude antidepressant use also are potential candidates for ECT.5,22

ECT can be administered to many older depressed adults with relatively low complication rates. Pretreatment clinical and laboratory evaluations and consultation with medical colleagues may minimize the risk of adverse effects, including cardiovascular instability, delirium, and falls.9 Anterograde memory loss—a common concern for clinicians and patients—usually is temporary and can be reduced by modifying the ECT administration parameters, such as switching from bilateral to unilateral stimulus and spacing treatments.9 Use caution when considering ECT for patients with cardiovascular or neurologic conditions—such as myocardial infarction or cerebrovascular accident within 6 months of treatment—that may increase the risk of adverse effects. Some pharmacologic agents, such as benzodiazepines and anticonvulsant mood stabilizers, may decrease ECT’s efficacy by inhibiting seizure.22

Depressive relapse after ECT is a major clinical concern.21 Continuation ECT— within the first 6 months of remission— aims to prevent relapse of the same episode, whereas maintenance ECT—beyond the first 6 months—helps avert occurrence of new episodes.4,21 Relapse and recurrence also can be prevented with continuation or maintenance pharmacotherapy,4,21 which should be initiated immediately after the index course of ECT.21 Typically, ECT continuation/maintenance treatments are provided weekly, then gradually spaced out to once a month based on the minimum frequency that is effective for an individual patient.21

Psychotherapy for geriatric depression generally is effective.23 One-half of older patients prefer psychotherapy over pharmacotherapy.24 Efficacious psychotherapies include behavioral therapy, cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), PST, brief dynamic therapy, interpersonal therapy, supportive therapy, and reminiscence therapy.23 CBT has the most empiric support for treating geriatric depression.5,6

Psychotherapy alone is appropriate for mild-to-moderate depression, although severe depression requires adding medication.25 The combination of pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy appears to be more effective than either intervention alone in preventing recurrent major depression, especially when a specific psychosocial stressor has been identified.5,6 CBT, interpersonal therapy, and family-focused therapy enhance pharmacotherapy outcomes in bipolar disorder.13

The Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program for Bipolar Disorder (STEP-BD) study found that in mixed-age patients, pharmacotherapy plus psychotherapy is more beneficial than medication alone in stabilizing bipolar depression.26 For older adults with executive dysfunction, research suggests that PST is more effective than other psychotherapies.27 Psychosocial interventions—such as psychoeducation for the family and caregivers, family counseling, and participation in senior citizen centers and services—are strongly recommended for many patients.4

Related Resources

- Blazer DG, Steffens DC, Koenig HG. Mood disorders. In: Blazer DG, Steffens DC, eds. The American Psychiatric Publishing textbook of geriatric psychiatry. 4th ed. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc.; 2009:275-300.

- American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry. www.aagponline.org.

Drug Brand Names

- Aripiprazole • Abilify

- Bupropion • Wellbutrin, Zyban

- Buspirone • Buspar

- Citalopram • Celexa

- Duloxetine • Cymbalta

- Escitalopram • Lexapro

- Fluoxetine • Prozac

- Fluoxetine-olanzapine • Symbyax

- Lamotrigine • Lamictal

- Lithium • Eskalith, Lithobid

- Mirtazapine • Remeron

- Nortriptyline • Aventyl, Pamelor

- Olanzapine • Zyprexa

- Paroxetine • Paxil

- Quetiapine • Seroquel

- Risperidone • Risperdal

- Sertraline • Zoloft

- Tranylcypromine • Parnate

- Trazodone • Desyrel

- Valproate • Depakote

- Venlafaxine • Effexor

- Ziprasidone • Geodon

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationship with the manufacturer of any product mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Discuss this article at http://currentpsychiatry.blogspot.com/2010/08/depression-in-older-adults.html#comments

Depression in older adults (age ≥65) can devastate their quality of life and increase the likelihood of institutionalization because of behavioral problems.1 Depression is a primary risk factor for suicide, and suicide rates are highest among those age ≥65, especially among white males.2 The burden of geriatric depression can extend to caregivers.1 Prompt recognition and treatment of depression could help minimize morbidity and reduce suffering in older adults and their caregivers.

Although geriatric depression varies in severity and presentation, common categories include:

- major depressive disorder (MDD)

- vascular depression

- dysthymia

- depression in the context of dementias, psychosis, bipolar disorder, and executive dysfunction.

Diagnoses in this population generally correspond with DSM-IV-TR criteria, but geriatric depression has distinct clinical manifestations.1,2 Compared with younger depressed patients, older adults are less likely to endorse depressed mood and more likely to report a lack of emotions.1,2 Older patients report feelings of irritability and fearfulness more often than sadness.1,2 Mood symptoms tend to be transient, reoccur frequently, and display either a diurnal pattern or multiple fluctuations in a single day.1,2 Other common presentations include loss of interest in usual activities, lack of motivation, social withdrawal, and decline in activities of daily living.1,2

Summary of recommendations

Age-specific recommendations for assessing and treating geriatric depression can be generated in part from evidence-based reviews, meta-analyses,3 and geriatric expert consensus guidelines.4 Such guidelines and recommendations often do not take into account the marked heterogeneity of medical, cognitive, and overall functioning in patients age ≥65, however, because they are based on studies of younger populations and patients with complicated issues often are excluded from studies. The recommendations in this article are based largely on findings from a National Institutes of Health (NIH)-sponsored project by Alexopoulos et al to develop consensus guidelines for managing geriatric depression and expert opinion from clinicians who treat geriatric patients.4

During your initial clinical evaluation, confirm the diagnosis and type, duration, and severity of depression. Seek to understand the biopsychosocial context of each patient’s presentation. Carefully consider your patient’s suicide risk. Hospitalization may be required if he or she is at high risk for suicide or has complex medical and social circumstances that cannot be managed adequately in an outpatient setting.5

Unipolar major depression

For unipolar, nonpsychotic geriatric depression, the NIH-Alexopoulos et al guidelines emphasize a combination of antidepressants and psychotherapy (Algorithm 1).4 Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and venlafaxine are first-line options.4,6,7 Tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), bupropion, and mirtazapine are alternatives.4 Among SSRIs, citalopram, escitalopram, and sertraline are preferred initial antidepressants. Fluoxetine is used less frequently.4 Paroxetine also is less commonly used because of its anticholinergic effects and because the drug inhibits cytochrome P4502D6,2 which metabolizes several medications commonly prescribed for older adults. Among TCAs, nortriptyline is preferred.4 Studies have shown that duloxetine improves depression and is safe and well-tolerated in older adults with recurrent MDD.8 Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) is an option for treating severe or treatment-resistant unipolar major depression.9

For unipolar depression with psychotic symptoms, guidelines recommend a combination of an antidepressant and an antipsychotic or ECT.4 Atypical antipsychotics are preferred over typical antipsychotics4; risperidone, olanzapine, and quetiapine are most frequently used.4 Clinical data on aripiprazole and ziprasidone in older adults are limited. Many geriatric experts recommend continuing an antipsychotic for 6 months after symptom remission, then gradually tapering the dose.4

During acute illness, administer an anti-depressant for 6 to 12 weeks at the individually determined dose required to achieve symptom remission.6 For an older adult experiencing a first lifetime episode of major depression, continue antidepressant treatment for 1 year after remission.4 If your patient has had 2 lifetime episodes of major depression, continue the antidepressant at the same dose used to achieve remission for at least 3 years. For patients who have had ≥3 episodes of depression or whose index episode was particularly severe or involved significant suicidal thoughts or behaviors, continue maintenance treatment indefinitely.

Algorithm 1: Treatment for unipolar depression in geriatric patients

ECT: electroconvulsive therapy

Bipolar depression

Mood stabilizers such as lithium or valproate—as monotherapy or in combination with an antidepressant—are recommended to treat bipolar depression without psychotic symptoms in older adults (Algorithm 2).10 For bipolar depression with psychotic symptoms, a combination of a mood stabilizer and an atypical antipsychotic or ECT is recommended.10

Older adults’ increased sensitivity to side effects and reduced ability to tolerate lithium may limit its use and may prompt you to consider atypical antipsychotics as alternatives to other mood stabilizers. Although quetiapine and fluoxetineolanzapine combination are well studied in younger patients,11,12 there is a lack of data to support their clinical effectiveness and tolerability in older adults. Among antidepressants, SSRIs or bupropion are preferred over TCAs to prevent a switch to mania.10 Lamotrigine is an effective maintenance treatment for bipolar depressive episodes in older adults.13

Although optimal mood stabilizer and antidepressant dosing for this population has not been adequately assessed, pharmacotherapy that has been effective generally should be continued without modification for at least 6 to 12 months.10 After the patient achieves remission, gradually discontinue antidepressants while maintaining the mood stabilizer.10

Algorithm 2: Bipolar depression: Options for combination therapy

ECT: electroconvulsive therapy; SSRIs: selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors

Depression in dementia

Managing depression in dementia patients is similar to treatment in older adults without dementia,5,14 although pharmacologic agents must be carefully selected because of increased risk of side effects (Algorithm 3). American Psychiatric Association practice guidelines recommend considering antidepressants for depressed patients with dementia even if their mood disturbances do not meet DSM-IV-TR criteria for MDD.5

SSRIs’ lower side effect profile make them the preferred treatment; the selective serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI) venlafaxine is a second-line option.4,14 Avoid TCAs and other agents with anticholinergic side effects because of potential cardiovascular complications and cognitive side effects, unless SSRIs or SNRIs are ineffective or contraindicated.14 Recently clinicians have been reluctant to use antipsychotics in patients with dementia, because of the FDA’s “black-box” warning regarding the increased mortality risk associated with their use in this population.

When using ECT to treat depression in patients with dementia, the treatment protocol often is modified to twice-a-week, unilateral stimulus because of these patients’ increased risk of delirium.14 The safety of ECT to treat depression in patients with dementia has not been adequately assessed.14

Algorithm 3: Treating comorbid depression and dementia

ECT: electroconvulsive therapy; SNRI: selective serotoninnorepinephrine reuptake inhibitor; SSRI: selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor

Vascular depression

The “vascular depression hypothesis” proposes that accumulation of subcortical white matter hyperintensities can disrupt frontostriatal pathways, resulting in depressive symptoms.15 This hypothesis is supported by the confluence of depression and vascular risk factors.15 Sertraline, citalopram, nortriptyline,16 and trazodone15 have been shown to reduce depressive symptoms after a stroke.

Minor depression and dysthymia

Although the efficacy of antidepressants in minor depression—depression that does not meet criteria for MDD—is not well established, expert consensus guidelines recommend SSRIs and psychotherapy, separately or in combination, for minor depression and dysthymia in older adults (Algorithm 4).4 Depression in executive dysfunction responds poorly to SSRI treatment2; however, behaviorally oriented psychotherapeutic interventions such as problem-solving therapy (PST) show promise.2

Algorithm 4: Minor depression: SSRIs plus psychotherapy

SSRIs: selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors

Comorbid medical conditions

When an older adult has a medical problem that likely contributes to depression—such as hypothyroidism—treat the condition and prescribe antidepressants simultaneously.2 However, if the medical problem likely causes depression—such as substance withdrawal—treat the condition first and prescribe antidepressants only if mood symptoms persist.2

Refractory depression