User login

Recognizing mimics of depression: The ‘8 Ds’

Discuss this article at www.facebook.com/CurrentPsychiatry

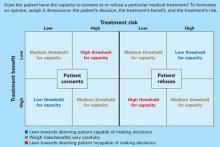

Many psychiatric and medical illnesses—as well as normal reactions to stressors—have symptoms that overlap with those of depressive disorders, including outwardly sad or dysphoric appearance, irritability, apathy or amotivation, fatigue, difficulty making decisions, social withdrawal, and sleep disturbances. This cluster of symptoms forms a readily observable behavioral phenotype that clinicians may label as depression before considering a broader differential diagnosis.

To better understand what other conditions belong in the differential diagnosis, we reviewed a sample of 100 consecutive medical/surgical inpatients referred to our consultation-liaison psychiatry practice for evaluation of “depression.” Ultimately, only 29 of these patients received a depression diagnosis. Many of the other diagnoses given in our sample required attention during inpatient medical or surgical care because they were potentially life-threatening if left unaddressed—such as delirium—or they interfered with managing the primary medical or surgical condition for which the patient was hospitalized.

Hurried or uncertain primary care clinicians frequently use “depression” as a catch-all term when requesting psychiatric consultation for patients who seem depressed. A wide range of conditions can mimic depression, and the art of psychosomatic psychiatry includes considering protean possibilities when assessing a patient. We identified 7 diagnoses that mimic major depression and developed our “8 D” differential to help clinicians properly diagnose “depressed” patients who have something other than a depressive disorder. Although our sample consisted of hospitalized patients, these mimics of depression may be found among patients referred from other clinical settings for evaluation of possible depression.

The perils of misdiagnosis

Depression is common among patients hospitalized with medical or surgical conditions. DSM-IV-TR diagnostic criteria for a major depressive episode (MDE) include the presence of low mood and/or anhedonia, plus ≥4 other depressive symptoms for ≥2 weeks.1 Growing evidence suggests that the relationship between depression and morbidity and mortality in medical illness is bidirectional, and nonpsychiatrists are becoming increasingly aware of major depression’s serious impact on their patients’ physical health.2-5

Although improving nonpsychiatrists’ recognition of depression in medically ill patients is laudable, it comes with a high false-positive rate. In a study of primary care outpatients, Berardi et al found that 45% of patients labeled “depressed” did not meet ICD-10 criteria for major depression, but >25% of those patients were prescribed an antidepressant.6 In a large retrospective study, Boland et al found that approximately 40% of patients referred to an inpatient psychiatric consultation service for depression did not meet criteria for a depressive illness, and primary medical services often confused organic syndromes such as delirium and dementia with depression.7 Similarly, Clarke et al found that 26% of medical and surgical inpatients referred to psychiatry with “depression” had another diagnosis—commonly delirium—that better accounted for their symptoms.8

What is the harm in overdiagnosing depression? Missing a serious or life-threatening diagnosis is a primary concern. For example, unrecognized delirium, which frequently was misdiagnosed as depression in the Berardi,6 Boland,7 and Clarke8 studies, is associated with myriad difficulties, including higher morbidity and mortality.9 Substance use disorders, which also commonly masquerade as depression, frequently are comorbid with medical illness. Delays in appropriate treatment of withdrawal syndromes—particularly of alcohol and sedative/hypnotic medications—are risk factors for increased mortality in these illnesses.10

Inappropriate, potentially harmful interventions are another concern. Many patients diagnosed with depression are prescribed antidepressants, but this is not always a benign intervention. Smith et al found that >10% of adult medical inpatients referred to a psychiatry consultation service who were started on an antidepressant had an adverse drug reaction severe enough to warrant discontinuing the medication.11 Antidepressant side effects relevant to medically ill patients include hyponatremia, serotonin syndrome, and exacerbation of delirium.12

Polypharmacy in medically ill patients increases the risk for serious drug-drug interactions. For example, serotonergic antidepressants can increase the risk for serotonin syndrome when combined with the analgesic tramadol, which has serotonergic activity,13 or the antibiotic linezolid, which is a reversible monoamine oxidase inhibitor.14 Many antidepressants—including paroxetine, fluoxetine, bupropion, sertraline, and duloxetine—are moderate to strong inhibitors of cytochrome P450 2D6 and therefore affect metabolism of many medications, including several beta blockers and antiarrhythmics, as well as the anti-estrogen tamoxifen. In the case of tamoxifen, which is a prodrug converted to active form by 2D6, concomitant use of a 2D6 inhibitor can substantially reduce the medication’s in vivo efficacy and lead to higher morbidity and mortality in breast cancer patients.15 As with any treatment, a decision to prescribe antidepressants needs to carefully be weighed in light of individual risks and benefits. This analysis starts by ensuring that an antidepressant is indicated.

Another concern is failing to recognize immediate human suffering for what it is. Hospitals and doctors’ offices are places of pain and loss as patients encounter morbidity and mortality in themselves and their loved ones. Rushing to pathologize the psychological or social manifestations of this pain can be invalidating to patients and may impair the doctor-patient relationship.

The 8 Ds

To determine what these “depression lookalike” syndromes could be, we identified 100 consecutive consultations to our adult inpatient psychiatry consultation-liaison team with a question of “depression.” We reviewed each patient’s chart, and recorded the diagnosis the psychiatrist gave to explain the patient’s depressed appearance. Data were recorded without patient identifiers, and the Mayo Clinic institutional review board (IRB) determined this study was exempt from IRB review.

Our sample included 45 men and 55 women with an average age of 48 (range: 18 to 91). On evaluation, 3 patients were given no psychiatric diagnosis, 29 were categorized as depressed, and 68 fell into one of 7 other “D” categories we describe below.

Depressed. These patients met criteria for a MDE in the context of major depressive disorder (MDD) or bipolar disorder, dysthymic disorder, mood disorder due to a general medical condition, substance-induced mood disorder, or depressive disorder not otherwise specified.

Demoralized. Patients who had difficulty adjusting to or coping with illness, and received a DSM-IV-TR diagnosis of adjustment disorder with the illness as the inciting stressor were placed in this category. Consistent with adjustment disorder criteria, these patients did not have depressive symptoms of sufficient intensity or duration to meet criteria for MDD or another primary mood disorder.

Difficult. For these patients, the primary issue was a breakdown in the therapeutic alliance with their treatment team. They received DSM-IV-TR diagnoses of personality disorder, noncompliance with treatment, or adult antisocial behavior.

Drugged. Patients in this category appeared depressed as a result of illicit substance use or misuse of alcohol or pharmaceuticals. DSM-IV-TR diagnoses included substance intoxication or withdrawal and substance abuse or dependence.

Delirious. This group consisted of patients with acute disruption in attention and level of consciousness that met DSM-IV-TR criteria for delirium. Patients whose delirious appearance was the result of illicit substance use or pharmaceutical misuse were categorized as “Drugged” rather than “Delirious.”

Disaffiliated. Patients in this category had dysphoria not commensurate with a full-blown mood disorder but attributable to grief from losing a major relationship to death, separation, or divorce. These patients received a DSM-IV-TR diagnosis of bereavement or a partner relational problem.

Delusional. These patients demonstrated amotivation and affective blunting as a result of a primary psychotic disorder such as schizophrenia. In preparation for emergent surgery, these patients had been prevented from taking anything orally, including antipsychotics, and their antipsychotics had not been restarted, which precipitated a gradual return of psychotic symptoms in the days after surgery.

Dulled. Two patients in our sample had irreversible cognitive deficits that explained their withdrawal and blunted affect; 1 had dementia and the other had mental retardation.

Managing the other Ds

In our sample, the most commonly misdiagnosed patients were those having difficulty adjusting to illness (Demoralized) or to other life events (Disaffiliated) (Table 1). In these cases, misdiagnosis has substantial treatment implications because these patients are better served by acute, illness-specific interventions that bolster coping skills, rather than pharmacotherapy or psychotherapy that targets entrenched depressive symptoms. For these patients, psychiatrists may “prescribe” interventions such as visits with a chaplain or other spiritual advisor, telephone calls or visits from family, friends, and other social supports, participation in physical or occupational therapy to improve adaptive functioning, or connecting with other patients in similar situations. Often, the key with these patients is to identify ways they have managed previous stressors and creatively use those resources to adapt to their new situation.

A second large group in our sample consisted of patients actively or passively fighting with their treatment team—the Difficult (Table 2). The treatment team or the patient’s caregivers and loved ones often are more distressed by the “difficult” patient’s symptoms than the patient, who may instead focus on his or her disappointment with caregivers who are unable to meet the patient’s unreasonable expectations. These challenges typically can be addressed by clarifying the salient issues for both the patient and team and establishing a liaison between patient and team to improve communication among all parties. Multidisciplinary care conferences can be an excellent way to ensure that the care team provides the patient with consistent communication and care.

A third group had potentially life-threatening conditions such as substance abuse/withdrawal or delirium as the cause of their “depressive” symptoms—the Drugged and the Delirious (Table 3). Recognizing an organic etiology of mood or behavioral symptoms is important because managing the underlying problem is the primary treatment strategy, not psychopharmacologic or psychotherapeutic intervention. Early identification and appropriate management of these patients could prevent further deterioration, improve medical outcomes, and shorten length of hospital stay.

A final group of patients was those whose chronic psychiatric and cognitive issues may go unrecognized or unappreciated until they interfere with the patient’s medical care—the Delusional and the Dulled (Table 2). In these cases, the correct diagnosis often hinges on obtaining a thorough history through collateral sources. The consulting psychiatrist can be crucial in co-managing these patients by establishing a liaison with outpatient providers, suggesting in-hospital management strategies such as alternate routes of administration of antipsychotics for patients with psychotic disorders, and connecting patients with outpatient supports after hospitalization. Continuity between inpatient and outpatient management is necessary to ensure a successful medical and psychiatric outcome.

Our 8 Ds are limited to the subset of patients referred by their medical teams with a question of depression. These referrals may have been motivated by a variety of patient, family, and team factors above and beyond the categories discussed in this article, and therefore may not accurately represent all patients who present with depressive symptoms in an inpatient setting. However, we hope that providing a mnemonic that suggests an extensive differential for a depressed phenotype may improve identification and management of these issues.

Table 1

Psychological crises that may look like depression

| Category | Percentage of our sample | Distinguishing features | Suggested interventions |

|---|---|---|---|

| “Depressed” patients met DSM-IV-TR criteria for a depressive disorder | 29% | Emotional symptoms: Depressed mood, anhedonia Cognitive symptoms: concentration problems, indecisiveness, negative thoughts, irrational guilt Physical symptoms: changes in sleep, appetite, energy | Initiate psychotherapy with or without antidepressants |

| “Demoralized” patients had difficulty coping with a medical illness | 23% | Close temporal association with illness. Few neurovegetative symptoms. Able to maintain future orientation/hope | Provide compassion, recognition, and normalization. Connect patients with illness-specific supports (groups, social work, chaplaincy). Implement interventions to improve functioning (eg, PT/OT). Encourage patients to engage in activities that have helped them cope in the past |

| “Disaffiliated” patients had dysphoria attributable to grief from losing a major relationship | 3% | Few neurovegetative symptoms. Able to maintain future orientation/hope. Improvement typical as time since loss increases | Encourage patients to connect with other supportive relationships. Refer patients to grief resources (eg, hospice, spiritual supports) |

| OT: occupational therapy; PT: physical therapy | |||

Table 2

Differentiating patients with social challenges from those with depression

| Category | Percentage of our sample | Distinguishing features | Suggested interventions |

|---|---|---|---|

| “Difficult” patients have a breakdown in the therapeutic alliance with their treatment team | 15% | Mood changes often intense, immediate, and reactive to situation. Frequent breakdowns in communication with care team. Care team more distressed by patient’s symptoms than the patient | Establish frequent communication among care team members. Use multidisciplinary care conferences to clarify salient issues for patients and their team. Provide patients with consistent information and expectations |

| “Delusional” patients had affective blunting as a result of a psychotic disorder | 2% | Suspicious about care team/procedures. Seems frightened or scans the room. On antipsychotics at admission. Slowly developing symptoms over several days after home medications are held | Acquire collateral history (an assigned community case manager or social worker can be an important source). Establish a plan for administering psychotropics in chronically mentally ill patients; consider IM or orally disintegrating formulations |

| “Dulled” patients had irreversible cognitive deficits | 2% | Baseline impairments in memory and/or independent functioning | Acquire collateral history. Perform a safety assessment of home environment with attention to need for additional supports |

| IM: intramuscular | |||

Table 3

Substance abuse and delirium can mimic depression

| Category | Percentage of our sample | Distinguishing features | Suggested interventions |

|---|---|---|---|

| “Drugged” patients appeared depressed as a result of substance use/ withdrawal | 12% | Acute presentation closely mimicking mood, anxiety, or psychotic disorders. Emotional symptoms present when intoxicated or withdrawing and resolved during sobriety | Implement safety interventions to prevent self-harm or aggression during acute phase. Support and monitor withdrawal as indicated. Reassess mood state and symptoms once the patient is sober. Refer for chemical dependency evaluation |

| “Delirious” patients met DSM-IV-TR criteria for delirium | 11% | Disoriented and inattentive. Onset over hours to days. Waxing and waning throughout the day. Possible hallucinations (often visual or tactile) | Identify and correct underlying medical cause(s). Restore the patient’s sleep-wake cycle. Provide frequent reorientation and reassurance |

Related Resources

- Stern TA, Fricchione GL, Cassem NH, et al, eds. Massachusetts General Hospital handbook of general hospital psychiatry, 6th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders Elsevier; 2010.

- Levenson JL, ed. The American Psychiatric Publishing textbook of psychosomatic medicine. 2nd ed. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc.; 2011.

- Academy of Psychosomatic Medicine. www.apm.org.

- Caplan JP, Stern TA. Mnemonics in a mnutshell: 32 aids to psychiatric diagnosis. Current Psychiatry. 2008;7(10):27-33.

Drug Brand Names

- Bupropion • Wellbutrin, Zyban

- Duloxetine • Cymbalta

- Fluoxetine • Prozac

- Linezolid • Zyvox

- Paroxetine • Paxil

- Sertraline • Zoloft

- Tamoxifen • Nolvadex

- Tramadol • Ultracet

Disclosures

Dr. Bostwick reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Dr. Rackley receives research/grant support from the Maternal and Child Health Bureau, Health Resources and Services Administration, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, for a Collaborative Office Rounds program with primary care pediatricians.

1. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders 4th ed, text rev. Washington DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

2. Hansen MS, Fink P, Frydenberg M, et al. Use of health services, mental illness, and self-rated disability and health in medical inpatients. Psychosom Med. 2002;64(4):668-675.

3. Hosaka T, Aoki T, Watanabe T, et al. Comorbidity of depression among physically ill patients and its effect on the length of hospital stay. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1999;53(4):491-495.

4. McCusker J, Cole M, Ciampi A, et al. Major depression in older medical inpatients predicts poor physical and mental health status over 12 months. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2007;29(4):340-348.

5. McCusker J, Cole M, Dufouil C, et al. The prevalence and correlates of major and minor depression in older medical inpatients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(8):1344-1353.

6. Berardi D, Menchetti M, Cevenini N, et al. Increased recognition of depression in primary care. Comparison between primary-care physician and ICD-10 diagnosis of depression. Psychother Psychosom. 2005;74(4):225-230.

7. Boland RJ, Diaz S, Lamdan RM, et al. Overdiagnosis of depression in the general hospital. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1996;18(1):28-35.

8. Clarke DM, McKenzie DP, Smith GC. The recognition of depression in patients referred to a consultation-liaison service. J Psychosom Res. 1995;39(3):327-334.

9. Siddiqi N, House AO, Holmes JD. Occurrence and outcome of delirium in medical in-patients: a systematic literature review. Age Ageing. 2006;35(4):350-364.

10. Franklin JE, Levenson JL, McCance-Katz EF. Substance-related disorders. In: Levenson JL, ed. The American Psychiatric Publishing textbook of psychosomatic medicine. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc.; 2005:387–420.

11. Smith GC, Clarke DM, Handrinos D, et al. Consultation-liaison psychiatrists’ use of antidepressants in the physically ill. Psychosomatics. 2002;43(3):221-227.

12. Robinson MJ, Owen JA. Psychopharmacology. In: Levenson JL, ed. The American Psychiatric Publishing textbook of psychosomatic medicine. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc.; 2005:387–420.

13. Hersh EV, Pinto A, Moore PA. Adverse drug interactions involving common prescription and over-the-counter analgesic agents. Clin Ther. 2007;29(suppl):2477-2497.

14. Sola CL, Bostwick JM, Hart DA, et al. Anticipating potential linezolid-SSRI interactions in the general hospital setting: an MAOI in disguise. Mayo Clin Proc. 2006;81(3):330-334.

15. Stearns V, Johnson MD, Rae JM, et al. Active tamoxifen metabolite plasma concentrations after coadministration of tamoxifen and the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor paroxetine. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2003;95(23):1758-1764.

Discuss this article at www.facebook.com/CurrentPsychiatry

Many psychiatric and medical illnesses—as well as normal reactions to stressors—have symptoms that overlap with those of depressive disorders, including outwardly sad or dysphoric appearance, irritability, apathy or amotivation, fatigue, difficulty making decisions, social withdrawal, and sleep disturbances. This cluster of symptoms forms a readily observable behavioral phenotype that clinicians may label as depression before considering a broader differential diagnosis.

To better understand what other conditions belong in the differential diagnosis, we reviewed a sample of 100 consecutive medical/surgical inpatients referred to our consultation-liaison psychiatry practice for evaluation of “depression.” Ultimately, only 29 of these patients received a depression diagnosis. Many of the other diagnoses given in our sample required attention during inpatient medical or surgical care because they were potentially life-threatening if left unaddressed—such as delirium—or they interfered with managing the primary medical or surgical condition for which the patient was hospitalized.

Hurried or uncertain primary care clinicians frequently use “depression” as a catch-all term when requesting psychiatric consultation for patients who seem depressed. A wide range of conditions can mimic depression, and the art of psychosomatic psychiatry includes considering protean possibilities when assessing a patient. We identified 7 diagnoses that mimic major depression and developed our “8 D” differential to help clinicians properly diagnose “depressed” patients who have something other than a depressive disorder. Although our sample consisted of hospitalized patients, these mimics of depression may be found among patients referred from other clinical settings for evaluation of possible depression.

The perils of misdiagnosis

Depression is common among patients hospitalized with medical or surgical conditions. DSM-IV-TR diagnostic criteria for a major depressive episode (MDE) include the presence of low mood and/or anhedonia, plus ≥4 other depressive symptoms for ≥2 weeks.1 Growing evidence suggests that the relationship between depression and morbidity and mortality in medical illness is bidirectional, and nonpsychiatrists are becoming increasingly aware of major depression’s serious impact on their patients’ physical health.2-5

Although improving nonpsychiatrists’ recognition of depression in medically ill patients is laudable, it comes with a high false-positive rate. In a study of primary care outpatients, Berardi et al found that 45% of patients labeled “depressed” did not meet ICD-10 criteria for major depression, but >25% of those patients were prescribed an antidepressant.6 In a large retrospective study, Boland et al found that approximately 40% of patients referred to an inpatient psychiatric consultation service for depression did not meet criteria for a depressive illness, and primary medical services often confused organic syndromes such as delirium and dementia with depression.7 Similarly, Clarke et al found that 26% of medical and surgical inpatients referred to psychiatry with “depression” had another diagnosis—commonly delirium—that better accounted for their symptoms.8

What is the harm in overdiagnosing depression? Missing a serious or life-threatening diagnosis is a primary concern. For example, unrecognized delirium, which frequently was misdiagnosed as depression in the Berardi,6 Boland,7 and Clarke8 studies, is associated with myriad difficulties, including higher morbidity and mortality.9 Substance use disorders, which also commonly masquerade as depression, frequently are comorbid with medical illness. Delays in appropriate treatment of withdrawal syndromes—particularly of alcohol and sedative/hypnotic medications—are risk factors for increased mortality in these illnesses.10

Inappropriate, potentially harmful interventions are another concern. Many patients diagnosed with depression are prescribed antidepressants, but this is not always a benign intervention. Smith et al found that >10% of adult medical inpatients referred to a psychiatry consultation service who were started on an antidepressant had an adverse drug reaction severe enough to warrant discontinuing the medication.11 Antidepressant side effects relevant to medically ill patients include hyponatremia, serotonin syndrome, and exacerbation of delirium.12

Polypharmacy in medically ill patients increases the risk for serious drug-drug interactions. For example, serotonergic antidepressants can increase the risk for serotonin syndrome when combined with the analgesic tramadol, which has serotonergic activity,13 or the antibiotic linezolid, which is a reversible monoamine oxidase inhibitor.14 Many antidepressants—including paroxetine, fluoxetine, bupropion, sertraline, and duloxetine—are moderate to strong inhibitors of cytochrome P450 2D6 and therefore affect metabolism of many medications, including several beta blockers and antiarrhythmics, as well as the anti-estrogen tamoxifen. In the case of tamoxifen, which is a prodrug converted to active form by 2D6, concomitant use of a 2D6 inhibitor can substantially reduce the medication’s in vivo efficacy and lead to higher morbidity and mortality in breast cancer patients.15 As with any treatment, a decision to prescribe antidepressants needs to carefully be weighed in light of individual risks and benefits. This analysis starts by ensuring that an antidepressant is indicated.

Another concern is failing to recognize immediate human suffering for what it is. Hospitals and doctors’ offices are places of pain and loss as patients encounter morbidity and mortality in themselves and their loved ones. Rushing to pathologize the psychological or social manifestations of this pain can be invalidating to patients and may impair the doctor-patient relationship.

The 8 Ds

To determine what these “depression lookalike” syndromes could be, we identified 100 consecutive consultations to our adult inpatient psychiatry consultation-liaison team with a question of “depression.” We reviewed each patient’s chart, and recorded the diagnosis the psychiatrist gave to explain the patient’s depressed appearance. Data were recorded without patient identifiers, and the Mayo Clinic institutional review board (IRB) determined this study was exempt from IRB review.

Our sample included 45 men and 55 women with an average age of 48 (range: 18 to 91). On evaluation, 3 patients were given no psychiatric diagnosis, 29 were categorized as depressed, and 68 fell into one of 7 other “D” categories we describe below.

Depressed. These patients met criteria for a MDE in the context of major depressive disorder (MDD) or bipolar disorder, dysthymic disorder, mood disorder due to a general medical condition, substance-induced mood disorder, or depressive disorder not otherwise specified.

Demoralized. Patients who had difficulty adjusting to or coping with illness, and received a DSM-IV-TR diagnosis of adjustment disorder with the illness as the inciting stressor were placed in this category. Consistent with adjustment disorder criteria, these patients did not have depressive symptoms of sufficient intensity or duration to meet criteria for MDD or another primary mood disorder.

Difficult. For these patients, the primary issue was a breakdown in the therapeutic alliance with their treatment team. They received DSM-IV-TR diagnoses of personality disorder, noncompliance with treatment, or adult antisocial behavior.

Drugged. Patients in this category appeared depressed as a result of illicit substance use or misuse of alcohol or pharmaceuticals. DSM-IV-TR diagnoses included substance intoxication or withdrawal and substance abuse or dependence.

Delirious. This group consisted of patients with acute disruption in attention and level of consciousness that met DSM-IV-TR criteria for delirium. Patients whose delirious appearance was the result of illicit substance use or pharmaceutical misuse were categorized as “Drugged” rather than “Delirious.”

Disaffiliated. Patients in this category had dysphoria not commensurate with a full-blown mood disorder but attributable to grief from losing a major relationship to death, separation, or divorce. These patients received a DSM-IV-TR diagnosis of bereavement or a partner relational problem.

Delusional. These patients demonstrated amotivation and affective blunting as a result of a primary psychotic disorder such as schizophrenia. In preparation for emergent surgery, these patients had been prevented from taking anything orally, including antipsychotics, and their antipsychotics had not been restarted, which precipitated a gradual return of psychotic symptoms in the days after surgery.

Dulled. Two patients in our sample had irreversible cognitive deficits that explained their withdrawal and blunted affect; 1 had dementia and the other had mental retardation.

Managing the other Ds

In our sample, the most commonly misdiagnosed patients were those having difficulty adjusting to illness (Demoralized) or to other life events (Disaffiliated) (Table 1). In these cases, misdiagnosis has substantial treatment implications because these patients are better served by acute, illness-specific interventions that bolster coping skills, rather than pharmacotherapy or psychotherapy that targets entrenched depressive symptoms. For these patients, psychiatrists may “prescribe” interventions such as visits with a chaplain or other spiritual advisor, telephone calls or visits from family, friends, and other social supports, participation in physical or occupational therapy to improve adaptive functioning, or connecting with other patients in similar situations. Often, the key with these patients is to identify ways they have managed previous stressors and creatively use those resources to adapt to their new situation.

A second large group in our sample consisted of patients actively or passively fighting with their treatment team—the Difficult (Table 2). The treatment team or the patient’s caregivers and loved ones often are more distressed by the “difficult” patient’s symptoms than the patient, who may instead focus on his or her disappointment with caregivers who are unable to meet the patient’s unreasonable expectations. These challenges typically can be addressed by clarifying the salient issues for both the patient and team and establishing a liaison between patient and team to improve communication among all parties. Multidisciplinary care conferences can be an excellent way to ensure that the care team provides the patient with consistent communication and care.

A third group had potentially life-threatening conditions such as substance abuse/withdrawal or delirium as the cause of their “depressive” symptoms—the Drugged and the Delirious (Table 3). Recognizing an organic etiology of mood or behavioral symptoms is important because managing the underlying problem is the primary treatment strategy, not psychopharmacologic or psychotherapeutic intervention. Early identification and appropriate management of these patients could prevent further deterioration, improve medical outcomes, and shorten length of hospital stay.

A final group of patients was those whose chronic psychiatric and cognitive issues may go unrecognized or unappreciated until they interfere with the patient’s medical care—the Delusional and the Dulled (Table 2). In these cases, the correct diagnosis often hinges on obtaining a thorough history through collateral sources. The consulting psychiatrist can be crucial in co-managing these patients by establishing a liaison with outpatient providers, suggesting in-hospital management strategies such as alternate routes of administration of antipsychotics for patients with psychotic disorders, and connecting patients with outpatient supports after hospitalization. Continuity between inpatient and outpatient management is necessary to ensure a successful medical and psychiatric outcome.

Our 8 Ds are limited to the subset of patients referred by their medical teams with a question of depression. These referrals may have been motivated by a variety of patient, family, and team factors above and beyond the categories discussed in this article, and therefore may not accurately represent all patients who present with depressive symptoms in an inpatient setting. However, we hope that providing a mnemonic that suggests an extensive differential for a depressed phenotype may improve identification and management of these issues.

Table 1

Psychological crises that may look like depression

| Category | Percentage of our sample | Distinguishing features | Suggested interventions |

|---|---|---|---|

| “Depressed” patients met DSM-IV-TR criteria for a depressive disorder | 29% | Emotional symptoms: Depressed mood, anhedonia Cognitive symptoms: concentration problems, indecisiveness, negative thoughts, irrational guilt Physical symptoms: changes in sleep, appetite, energy | Initiate psychotherapy with or without antidepressants |

| “Demoralized” patients had difficulty coping with a medical illness | 23% | Close temporal association with illness. Few neurovegetative symptoms. Able to maintain future orientation/hope | Provide compassion, recognition, and normalization. Connect patients with illness-specific supports (groups, social work, chaplaincy). Implement interventions to improve functioning (eg, PT/OT). Encourage patients to engage in activities that have helped them cope in the past |

| “Disaffiliated” patients had dysphoria attributable to grief from losing a major relationship | 3% | Few neurovegetative symptoms. Able to maintain future orientation/hope. Improvement typical as time since loss increases | Encourage patients to connect with other supportive relationships. Refer patients to grief resources (eg, hospice, spiritual supports) |

| OT: occupational therapy; PT: physical therapy | |||

Table 2

Differentiating patients with social challenges from those with depression

| Category | Percentage of our sample | Distinguishing features | Suggested interventions |

|---|---|---|---|

| “Difficult” patients have a breakdown in the therapeutic alliance with their treatment team | 15% | Mood changes often intense, immediate, and reactive to situation. Frequent breakdowns in communication with care team. Care team more distressed by patient’s symptoms than the patient | Establish frequent communication among care team members. Use multidisciplinary care conferences to clarify salient issues for patients and their team. Provide patients with consistent information and expectations |

| “Delusional” patients had affective blunting as a result of a psychotic disorder | 2% | Suspicious about care team/procedures. Seems frightened or scans the room. On antipsychotics at admission. Slowly developing symptoms over several days after home medications are held | Acquire collateral history (an assigned community case manager or social worker can be an important source). Establish a plan for administering psychotropics in chronically mentally ill patients; consider IM or orally disintegrating formulations |

| “Dulled” patients had irreversible cognitive deficits | 2% | Baseline impairments in memory and/or independent functioning | Acquire collateral history. Perform a safety assessment of home environment with attention to need for additional supports |

| IM: intramuscular | |||

Table 3

Substance abuse and delirium can mimic depression

| Category | Percentage of our sample | Distinguishing features | Suggested interventions |

|---|---|---|---|

| “Drugged” patients appeared depressed as a result of substance use/ withdrawal | 12% | Acute presentation closely mimicking mood, anxiety, or psychotic disorders. Emotional symptoms present when intoxicated or withdrawing and resolved during sobriety | Implement safety interventions to prevent self-harm or aggression during acute phase. Support and monitor withdrawal as indicated. Reassess mood state and symptoms once the patient is sober. Refer for chemical dependency evaluation |

| “Delirious” patients met DSM-IV-TR criteria for delirium | 11% | Disoriented and inattentive. Onset over hours to days. Waxing and waning throughout the day. Possible hallucinations (often visual or tactile) | Identify and correct underlying medical cause(s). Restore the patient’s sleep-wake cycle. Provide frequent reorientation and reassurance |

Related Resources

- Stern TA, Fricchione GL, Cassem NH, et al, eds. Massachusetts General Hospital handbook of general hospital psychiatry, 6th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders Elsevier; 2010.

- Levenson JL, ed. The American Psychiatric Publishing textbook of psychosomatic medicine. 2nd ed. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc.; 2011.

- Academy of Psychosomatic Medicine. www.apm.org.

- Caplan JP, Stern TA. Mnemonics in a mnutshell: 32 aids to psychiatric diagnosis. Current Psychiatry. 2008;7(10):27-33.

Drug Brand Names

- Bupropion • Wellbutrin, Zyban

- Duloxetine • Cymbalta

- Fluoxetine • Prozac

- Linezolid • Zyvox

- Paroxetine • Paxil

- Sertraline • Zoloft

- Tamoxifen • Nolvadex

- Tramadol • Ultracet

Disclosures

Dr. Bostwick reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Dr. Rackley receives research/grant support from the Maternal and Child Health Bureau, Health Resources and Services Administration, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, for a Collaborative Office Rounds program with primary care pediatricians.

Discuss this article at www.facebook.com/CurrentPsychiatry

Many psychiatric and medical illnesses—as well as normal reactions to stressors—have symptoms that overlap with those of depressive disorders, including outwardly sad or dysphoric appearance, irritability, apathy or amotivation, fatigue, difficulty making decisions, social withdrawal, and sleep disturbances. This cluster of symptoms forms a readily observable behavioral phenotype that clinicians may label as depression before considering a broader differential diagnosis.

To better understand what other conditions belong in the differential diagnosis, we reviewed a sample of 100 consecutive medical/surgical inpatients referred to our consultation-liaison psychiatry practice for evaluation of “depression.” Ultimately, only 29 of these patients received a depression diagnosis. Many of the other diagnoses given in our sample required attention during inpatient medical or surgical care because they were potentially life-threatening if left unaddressed—such as delirium—or they interfered with managing the primary medical or surgical condition for which the patient was hospitalized.

Hurried or uncertain primary care clinicians frequently use “depression” as a catch-all term when requesting psychiatric consultation for patients who seem depressed. A wide range of conditions can mimic depression, and the art of psychosomatic psychiatry includes considering protean possibilities when assessing a patient. We identified 7 diagnoses that mimic major depression and developed our “8 D” differential to help clinicians properly diagnose “depressed” patients who have something other than a depressive disorder. Although our sample consisted of hospitalized patients, these mimics of depression may be found among patients referred from other clinical settings for evaluation of possible depression.

The perils of misdiagnosis

Depression is common among patients hospitalized with medical or surgical conditions. DSM-IV-TR diagnostic criteria for a major depressive episode (MDE) include the presence of low mood and/or anhedonia, plus ≥4 other depressive symptoms for ≥2 weeks.1 Growing evidence suggests that the relationship between depression and morbidity and mortality in medical illness is bidirectional, and nonpsychiatrists are becoming increasingly aware of major depression’s serious impact on their patients’ physical health.2-5

Although improving nonpsychiatrists’ recognition of depression in medically ill patients is laudable, it comes with a high false-positive rate. In a study of primary care outpatients, Berardi et al found that 45% of patients labeled “depressed” did not meet ICD-10 criteria for major depression, but >25% of those patients were prescribed an antidepressant.6 In a large retrospective study, Boland et al found that approximately 40% of patients referred to an inpatient psychiatric consultation service for depression did not meet criteria for a depressive illness, and primary medical services often confused organic syndromes such as delirium and dementia with depression.7 Similarly, Clarke et al found that 26% of medical and surgical inpatients referred to psychiatry with “depression” had another diagnosis—commonly delirium—that better accounted for their symptoms.8

What is the harm in overdiagnosing depression? Missing a serious or life-threatening diagnosis is a primary concern. For example, unrecognized delirium, which frequently was misdiagnosed as depression in the Berardi,6 Boland,7 and Clarke8 studies, is associated with myriad difficulties, including higher morbidity and mortality.9 Substance use disorders, which also commonly masquerade as depression, frequently are comorbid with medical illness. Delays in appropriate treatment of withdrawal syndromes—particularly of alcohol and sedative/hypnotic medications—are risk factors for increased mortality in these illnesses.10

Inappropriate, potentially harmful interventions are another concern. Many patients diagnosed with depression are prescribed antidepressants, but this is not always a benign intervention. Smith et al found that >10% of adult medical inpatients referred to a psychiatry consultation service who were started on an antidepressant had an adverse drug reaction severe enough to warrant discontinuing the medication.11 Antidepressant side effects relevant to medically ill patients include hyponatremia, serotonin syndrome, and exacerbation of delirium.12

Polypharmacy in medically ill patients increases the risk for serious drug-drug interactions. For example, serotonergic antidepressants can increase the risk for serotonin syndrome when combined with the analgesic tramadol, which has serotonergic activity,13 or the antibiotic linezolid, which is a reversible monoamine oxidase inhibitor.14 Many antidepressants—including paroxetine, fluoxetine, bupropion, sertraline, and duloxetine—are moderate to strong inhibitors of cytochrome P450 2D6 and therefore affect metabolism of many medications, including several beta blockers and antiarrhythmics, as well as the anti-estrogen tamoxifen. In the case of tamoxifen, which is a prodrug converted to active form by 2D6, concomitant use of a 2D6 inhibitor can substantially reduce the medication’s in vivo efficacy and lead to higher morbidity and mortality in breast cancer patients.15 As with any treatment, a decision to prescribe antidepressants needs to carefully be weighed in light of individual risks and benefits. This analysis starts by ensuring that an antidepressant is indicated.

Another concern is failing to recognize immediate human suffering for what it is. Hospitals and doctors’ offices are places of pain and loss as patients encounter morbidity and mortality in themselves and their loved ones. Rushing to pathologize the psychological or social manifestations of this pain can be invalidating to patients and may impair the doctor-patient relationship.

The 8 Ds

To determine what these “depression lookalike” syndromes could be, we identified 100 consecutive consultations to our adult inpatient psychiatry consultation-liaison team with a question of “depression.” We reviewed each patient’s chart, and recorded the diagnosis the psychiatrist gave to explain the patient’s depressed appearance. Data were recorded without patient identifiers, and the Mayo Clinic institutional review board (IRB) determined this study was exempt from IRB review.

Our sample included 45 men and 55 women with an average age of 48 (range: 18 to 91). On evaluation, 3 patients were given no psychiatric diagnosis, 29 were categorized as depressed, and 68 fell into one of 7 other “D” categories we describe below.

Depressed. These patients met criteria for a MDE in the context of major depressive disorder (MDD) or bipolar disorder, dysthymic disorder, mood disorder due to a general medical condition, substance-induced mood disorder, or depressive disorder not otherwise specified.

Demoralized. Patients who had difficulty adjusting to or coping with illness, and received a DSM-IV-TR diagnosis of adjustment disorder with the illness as the inciting stressor were placed in this category. Consistent with adjustment disorder criteria, these patients did not have depressive symptoms of sufficient intensity or duration to meet criteria for MDD or another primary mood disorder.

Difficult. For these patients, the primary issue was a breakdown in the therapeutic alliance with their treatment team. They received DSM-IV-TR diagnoses of personality disorder, noncompliance with treatment, or adult antisocial behavior.

Drugged. Patients in this category appeared depressed as a result of illicit substance use or misuse of alcohol or pharmaceuticals. DSM-IV-TR diagnoses included substance intoxication or withdrawal and substance abuse or dependence.

Delirious. This group consisted of patients with acute disruption in attention and level of consciousness that met DSM-IV-TR criteria for delirium. Patients whose delirious appearance was the result of illicit substance use or pharmaceutical misuse were categorized as “Drugged” rather than “Delirious.”

Disaffiliated. Patients in this category had dysphoria not commensurate with a full-blown mood disorder but attributable to grief from losing a major relationship to death, separation, or divorce. These patients received a DSM-IV-TR diagnosis of bereavement or a partner relational problem.

Delusional. These patients demonstrated amotivation and affective blunting as a result of a primary psychotic disorder such as schizophrenia. In preparation for emergent surgery, these patients had been prevented from taking anything orally, including antipsychotics, and their antipsychotics had not been restarted, which precipitated a gradual return of psychotic symptoms in the days after surgery.

Dulled. Two patients in our sample had irreversible cognitive deficits that explained their withdrawal and blunted affect; 1 had dementia and the other had mental retardation.

Managing the other Ds

In our sample, the most commonly misdiagnosed patients were those having difficulty adjusting to illness (Demoralized) or to other life events (Disaffiliated) (Table 1). In these cases, misdiagnosis has substantial treatment implications because these patients are better served by acute, illness-specific interventions that bolster coping skills, rather than pharmacotherapy or psychotherapy that targets entrenched depressive symptoms. For these patients, psychiatrists may “prescribe” interventions such as visits with a chaplain or other spiritual advisor, telephone calls or visits from family, friends, and other social supports, participation in physical or occupational therapy to improve adaptive functioning, or connecting with other patients in similar situations. Often, the key with these patients is to identify ways they have managed previous stressors and creatively use those resources to adapt to their new situation.

A second large group in our sample consisted of patients actively or passively fighting with their treatment team—the Difficult (Table 2). The treatment team or the patient’s caregivers and loved ones often are more distressed by the “difficult” patient’s symptoms than the patient, who may instead focus on his or her disappointment with caregivers who are unable to meet the patient’s unreasonable expectations. These challenges typically can be addressed by clarifying the salient issues for both the patient and team and establishing a liaison between patient and team to improve communication among all parties. Multidisciplinary care conferences can be an excellent way to ensure that the care team provides the patient with consistent communication and care.

A third group had potentially life-threatening conditions such as substance abuse/withdrawal or delirium as the cause of their “depressive” symptoms—the Drugged and the Delirious (Table 3). Recognizing an organic etiology of mood or behavioral symptoms is important because managing the underlying problem is the primary treatment strategy, not psychopharmacologic or psychotherapeutic intervention. Early identification and appropriate management of these patients could prevent further deterioration, improve medical outcomes, and shorten length of hospital stay.

A final group of patients was those whose chronic psychiatric and cognitive issues may go unrecognized or unappreciated until they interfere with the patient’s medical care—the Delusional and the Dulled (Table 2). In these cases, the correct diagnosis often hinges on obtaining a thorough history through collateral sources. The consulting psychiatrist can be crucial in co-managing these patients by establishing a liaison with outpatient providers, suggesting in-hospital management strategies such as alternate routes of administration of antipsychotics for patients with psychotic disorders, and connecting patients with outpatient supports after hospitalization. Continuity between inpatient and outpatient management is necessary to ensure a successful medical and psychiatric outcome.

Our 8 Ds are limited to the subset of patients referred by their medical teams with a question of depression. These referrals may have been motivated by a variety of patient, family, and team factors above and beyond the categories discussed in this article, and therefore may not accurately represent all patients who present with depressive symptoms in an inpatient setting. However, we hope that providing a mnemonic that suggests an extensive differential for a depressed phenotype may improve identification and management of these issues.

Table 1

Psychological crises that may look like depression

| Category | Percentage of our sample | Distinguishing features | Suggested interventions |

|---|---|---|---|

| “Depressed” patients met DSM-IV-TR criteria for a depressive disorder | 29% | Emotional symptoms: Depressed mood, anhedonia Cognitive symptoms: concentration problems, indecisiveness, negative thoughts, irrational guilt Physical symptoms: changes in sleep, appetite, energy | Initiate psychotherapy with or without antidepressants |

| “Demoralized” patients had difficulty coping with a medical illness | 23% | Close temporal association with illness. Few neurovegetative symptoms. Able to maintain future orientation/hope | Provide compassion, recognition, and normalization. Connect patients with illness-specific supports (groups, social work, chaplaincy). Implement interventions to improve functioning (eg, PT/OT). Encourage patients to engage in activities that have helped them cope in the past |

| “Disaffiliated” patients had dysphoria attributable to grief from losing a major relationship | 3% | Few neurovegetative symptoms. Able to maintain future orientation/hope. Improvement typical as time since loss increases | Encourage patients to connect with other supportive relationships. Refer patients to grief resources (eg, hospice, spiritual supports) |

| OT: occupational therapy; PT: physical therapy | |||

Table 2

Differentiating patients with social challenges from those with depression

| Category | Percentage of our sample | Distinguishing features | Suggested interventions |

|---|---|---|---|

| “Difficult” patients have a breakdown in the therapeutic alliance with their treatment team | 15% | Mood changes often intense, immediate, and reactive to situation. Frequent breakdowns in communication with care team. Care team more distressed by patient’s symptoms than the patient | Establish frequent communication among care team members. Use multidisciplinary care conferences to clarify salient issues for patients and their team. Provide patients with consistent information and expectations |

| “Delusional” patients had affective blunting as a result of a psychotic disorder | 2% | Suspicious about care team/procedures. Seems frightened or scans the room. On antipsychotics at admission. Slowly developing symptoms over several days after home medications are held | Acquire collateral history (an assigned community case manager or social worker can be an important source). Establish a plan for administering psychotropics in chronically mentally ill patients; consider IM or orally disintegrating formulations |

| “Dulled” patients had irreversible cognitive deficits | 2% | Baseline impairments in memory and/or independent functioning | Acquire collateral history. Perform a safety assessment of home environment with attention to need for additional supports |

| IM: intramuscular | |||

Table 3

Substance abuse and delirium can mimic depression

| Category | Percentage of our sample | Distinguishing features | Suggested interventions |

|---|---|---|---|

| “Drugged” patients appeared depressed as a result of substance use/ withdrawal | 12% | Acute presentation closely mimicking mood, anxiety, or psychotic disorders. Emotional symptoms present when intoxicated or withdrawing and resolved during sobriety | Implement safety interventions to prevent self-harm or aggression during acute phase. Support and monitor withdrawal as indicated. Reassess mood state and symptoms once the patient is sober. Refer for chemical dependency evaluation |

| “Delirious” patients met DSM-IV-TR criteria for delirium | 11% | Disoriented and inattentive. Onset over hours to days. Waxing and waning throughout the day. Possible hallucinations (often visual or tactile) | Identify and correct underlying medical cause(s). Restore the patient’s sleep-wake cycle. Provide frequent reorientation and reassurance |

Related Resources

- Stern TA, Fricchione GL, Cassem NH, et al, eds. Massachusetts General Hospital handbook of general hospital psychiatry, 6th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders Elsevier; 2010.

- Levenson JL, ed. The American Psychiatric Publishing textbook of psychosomatic medicine. 2nd ed. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc.; 2011.

- Academy of Psychosomatic Medicine. www.apm.org.

- Caplan JP, Stern TA. Mnemonics in a mnutshell: 32 aids to psychiatric diagnosis. Current Psychiatry. 2008;7(10):27-33.

Drug Brand Names

- Bupropion • Wellbutrin, Zyban

- Duloxetine • Cymbalta

- Fluoxetine • Prozac

- Linezolid • Zyvox

- Paroxetine • Paxil

- Sertraline • Zoloft

- Tamoxifen • Nolvadex

- Tramadol • Ultracet

Disclosures

Dr. Bostwick reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Dr. Rackley receives research/grant support from the Maternal and Child Health Bureau, Health Resources and Services Administration, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, for a Collaborative Office Rounds program with primary care pediatricians.

1. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders 4th ed, text rev. Washington DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

2. Hansen MS, Fink P, Frydenberg M, et al. Use of health services, mental illness, and self-rated disability and health in medical inpatients. Psychosom Med. 2002;64(4):668-675.

3. Hosaka T, Aoki T, Watanabe T, et al. Comorbidity of depression among physically ill patients and its effect on the length of hospital stay. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1999;53(4):491-495.

4. McCusker J, Cole M, Ciampi A, et al. Major depression in older medical inpatients predicts poor physical and mental health status over 12 months. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2007;29(4):340-348.

5. McCusker J, Cole M, Dufouil C, et al. The prevalence and correlates of major and minor depression in older medical inpatients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(8):1344-1353.

6. Berardi D, Menchetti M, Cevenini N, et al. Increased recognition of depression in primary care. Comparison between primary-care physician and ICD-10 diagnosis of depression. Psychother Psychosom. 2005;74(4):225-230.

7. Boland RJ, Diaz S, Lamdan RM, et al. Overdiagnosis of depression in the general hospital. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1996;18(1):28-35.

8. Clarke DM, McKenzie DP, Smith GC. The recognition of depression in patients referred to a consultation-liaison service. J Psychosom Res. 1995;39(3):327-334.

9. Siddiqi N, House AO, Holmes JD. Occurrence and outcome of delirium in medical in-patients: a systematic literature review. Age Ageing. 2006;35(4):350-364.

10. Franklin JE, Levenson JL, McCance-Katz EF. Substance-related disorders. In: Levenson JL, ed. The American Psychiatric Publishing textbook of psychosomatic medicine. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc.; 2005:387–420.

11. Smith GC, Clarke DM, Handrinos D, et al. Consultation-liaison psychiatrists’ use of antidepressants in the physically ill. Psychosomatics. 2002;43(3):221-227.

12. Robinson MJ, Owen JA. Psychopharmacology. In: Levenson JL, ed. The American Psychiatric Publishing textbook of psychosomatic medicine. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc.; 2005:387–420.

13. Hersh EV, Pinto A, Moore PA. Adverse drug interactions involving common prescription and over-the-counter analgesic agents. Clin Ther. 2007;29(suppl):2477-2497.

14. Sola CL, Bostwick JM, Hart DA, et al. Anticipating potential linezolid-SSRI interactions in the general hospital setting: an MAOI in disguise. Mayo Clin Proc. 2006;81(3):330-334.

15. Stearns V, Johnson MD, Rae JM, et al. Active tamoxifen metabolite plasma concentrations after coadministration of tamoxifen and the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor paroxetine. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2003;95(23):1758-1764.

1. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders 4th ed, text rev. Washington DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

2. Hansen MS, Fink P, Frydenberg M, et al. Use of health services, mental illness, and self-rated disability and health in medical inpatients. Psychosom Med. 2002;64(4):668-675.

3. Hosaka T, Aoki T, Watanabe T, et al. Comorbidity of depression among physically ill patients and its effect on the length of hospital stay. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1999;53(4):491-495.

4. McCusker J, Cole M, Ciampi A, et al. Major depression in older medical inpatients predicts poor physical and mental health status over 12 months. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2007;29(4):340-348.

5. McCusker J, Cole M, Dufouil C, et al. The prevalence and correlates of major and minor depression in older medical inpatients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(8):1344-1353.

6. Berardi D, Menchetti M, Cevenini N, et al. Increased recognition of depression in primary care. Comparison between primary-care physician and ICD-10 diagnosis of depression. Psychother Psychosom. 2005;74(4):225-230.

7. Boland RJ, Diaz S, Lamdan RM, et al. Overdiagnosis of depression in the general hospital. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1996;18(1):28-35.

8. Clarke DM, McKenzie DP, Smith GC. The recognition of depression in patients referred to a consultation-liaison service. J Psychosom Res. 1995;39(3):327-334.

9. Siddiqi N, House AO, Holmes JD. Occurrence and outcome of delirium in medical in-patients: a systematic literature review. Age Ageing. 2006;35(4):350-364.

10. Franklin JE, Levenson JL, McCance-Katz EF. Substance-related disorders. In: Levenson JL, ed. The American Psychiatric Publishing textbook of psychosomatic medicine. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc.; 2005:387–420.

11. Smith GC, Clarke DM, Handrinos D, et al. Consultation-liaison psychiatrists’ use of antidepressants in the physically ill. Psychosomatics. 2002;43(3):221-227.

12. Robinson MJ, Owen JA. Psychopharmacology. In: Levenson JL, ed. The American Psychiatric Publishing textbook of psychosomatic medicine. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc.; 2005:387–420.

13. Hersh EV, Pinto A, Moore PA. Adverse drug interactions involving common prescription and over-the-counter analgesic agents. Clin Ther. 2007;29(suppl):2477-2497.

14. Sola CL, Bostwick JM, Hart DA, et al. Anticipating potential linezolid-SSRI interactions in the general hospital setting: an MAOI in disguise. Mayo Clin Proc. 2006;81(3):330-334.

15. Stearns V, Johnson MD, Rae JM, et al. Active tamoxifen metabolite plasma concentrations after coadministration of tamoxifen and the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor paroxetine. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2003;95(23):1758-1764.

Life after near death: What interventions work for a suicide survivor?

Completed suicide provokes a multitude of questions: What motivated it? What interventions could have diverted it? Could anyone or anything have prevented it? The question of who dies by suicide often overshadows the question of what lessons suicide attempt (SA) survivors can teach us. Their story does not end with the attempt episode. For these patients, we have ongoing opportunities for interventions to make a difference.

A history of SA strongly predicts eventual completion, so we must try to identify which survivors will reattempt and complete suicide. This article addresses what is known about the psychiatry of suicide survivors—suicide motives and methods, clinical management, and short- and long-term outcomes—from the perspective that suicidality in this population may be a trait, with SA or deliberate self-harm (DSH) as its state-driven manifestations. When viewed in this manner, it is not just a question of who survives a suicide attempt, but who survives suicidality.

CASE REPORT: End of the game

Ms. T, age 39, was admitted to the intensive care unit after an aspirin overdose. She had been living with a man in a southern state for 8 years since the demise of her first marriage, but kept deferring remarriage. She returned to Minnesota with her teenage daughter to visit her family and stayed 6 months. Her partner phoned Ms. T every day, telling her he wanted her to come back. One day he tired of the game and said, “Fine, don’t come back.” She immediately overdosed, then called him to tell him what she’d done. He called her daughter, telling her to go check on her mother and to call 911. When later asked why she did it, Ms. T said, “So he would know how much he loved me.”

Motive for self-harm

Ms. T’s suicide attempt was nonlethal, and she reported it immediately—characteristics of parasuicidal gesturing as a motive. A useful categorization of suicidal behavior divides it into discrete categories or narratives. Gardner and Cowdry describe 4: true suicidal acts, parasuicidal gesturing, self-mutilation, and retributive rage.1 We modify this schema with 4 additional categories: altruism, acute shame, command hallucinations, and panic ( Table 1 ).1-3 Categories are differentiated by affective state, motivation, and goal of behavior, but all involve situations in which the individual feels a lack of other options and resorts to maladaptive strategies.

Although this classification scheme helps clinicians understand a patient’s mindset, the specific motive underpinning DSH or SA is not consistently linked to its lethality. True suicidal acts frequently are marked by careful planning and high-lethality methods that increase the risk of completed suicide, but any motive can lead to a lethal act, whether or not death was intended.2,3

Factors that increase the risk of SA and completed suicide include male gender, age (adolescent or age >60), low socioeconomic status, and alcohol or drug abuse.4 An underlying mood disorder accounts for 73% of attributable risk of suicide or medically serious SA in older adults.5 This connection between mood and suicidality highlights the concept that emotional pain can cause so much suffering that patients seek release from distress by ending their lives.

A useful model by Shneidman6 casts psychological pain as 1 dimension in a 3-dimensional system that includes press and perturbation. In this model:

- Pain refers to psychological pain (from little or no pain to intolerable agony).

- Press means actual or imagined events in the inner or outer world that cause a person to react. It ranges from positive press (good fortune, happy events, protective factors) to negative press (stressors, failures, losses, persecution), which in turn decrease or increase the likelihood of suicide.

- Perturbation refers to the state of being disturbed or upset.

Certain risk factors make SA simultaneously more likely to occur but less likely to be lethal. For example, parental discord, nonheterosexual orientation, and female gender have been found to increase non-fatal attempts among adolescents.7 Borderline personality disorder increases the reattempt rate out of proportion to completion among adults.8 One might interpret a pattern of repeated nonlethal attempts to mean the patient has no real intent to die, but this is not always the case.

8

Table 1

8 categories or narratives of suicidal behavior

| Motive | Characteristics |

|---|---|

| True suicidal act | Release from intense baseline despair/hopelessness; self-nihilism as a permanent end to internal pain (entails highest intent to die and highest risk of completed suicide) |

| Self-mutilation | Relieving dysphoria or dissociation/depersonalization; acts of DSH designed to self-regulate or distract from emotional pain or other overwhelming affects |

| Retributive rage | Revenge; impulsiveness, vengefulness, and reduced capacity to conceive of other immediate options |

| Parasuicidal gesturing | Communication designed to extract a response from a significant other; often repetitive acts of DSH, strong dependency needs |

| Acute shame | Penance designed to escape from or to atone for a shameful act; often occurs within a short time after act is committed |

| Altruism | Relief of real or imagined burden on others; often occurs in setting of medical illness or substantial financial concerns |

| Command hallucinations | Acting in compliance with a command hallucination; often in setting of schizophrenia or depression with psychotic features |

| Panic | Driven by agitation, psychic anxiety, and/or panic attack; action intended as escape from real or imagined factor provoking agitation |

| DSH: deliberate self-harm | |

| Source: References 1-3 | |

CASE REPORT: Caught in the act

Mrs. L, age 35, works at a nail salon and took $12 from the cash register to buy gas so she could visit her husband in the next town. She’d never done anything like that before. She planned to return the money the next day, but her act was captured by a security camera and reported before she had a chance. Her boss said she had to go to the police.

Mrs. L was so ashamed that she decided she wanted to die. She drove her car to a remote hunting area where she tried to shoot herself in the head. The gun bucked, however, and shot her in the shoulder instead. She climbed into the front seat and drove herself to the hospital.

Method of self-harm

Survival of a suicide attempt depends in part on the lethality of the suicide method. Although she survived, Mrs. L’s attempt was intended to be quite lethal and illustrates shame as a motive.

The method’s lethality does not always correlate with the intent to die.9 Attempters with the highest suicidal intent do not reliably choose the most lethal method, either because they overestimate the lethality of methods such as cutting or overdose or because less lethal methods were most accessible.

Firearms, which are both accessible and lethal, remain the most common and deadly method in the United States, with more suicides from gunshot than all other methods combined.13 Cultural factors also are involved, such as in India where poisoning (especially with readily available organophosphates) is more common than gunshot.14 Suicidality screening in psychiatric practice and in the emergency department should always include questioning about convenient access to lethal means, especially those commonly used among the local population.

Clinical management

Treatment goals for patients who have demonstrated suicidal behavior may include decreasing the occurrence of suicidal thoughts, plans, gestures, or attempts. At a population level, accepted management strategies include:

- psychotherapy (cognitive-behavioral therapy [CBT], dialectical behavioral therapy)

- contracts for safety (widely employed but lacking evidence of efficacy)

- medications that target underlying disorders (antidepressants, mood stabilizers, antipsychotics).

Ineffective interventions? A study examining suicide trends since 1990 in the United States18 found disheartening evidence that although treatment dramatically increased, the incidence of suicidal thoughts, plans, gestures, or attempts did not significantly decrease ( Box 1 ).18–26 Based on a systematic review of 15 randomized controlled trials, Arensman et al19 offered 2 explanations for why studies of various psychosocial and pharmacologic interventions showed no significant effect on suicidality compared with usual care:

- the intervention had a negligible effect on patient outcomes

- the sample size was too small to detect clinically important differences in reattempt rates.

Suicide research deploys a single intervention for a diverse group of subjects rather than tailoring the approach to each particular case. A certain intervention may be highly effective for 1 patient because it is well matched to the specific blend of issues driving that patient’s suicidality, yet ineffective for another because it fails to address that individual’s underlying issues. Thus, a single treatment program standardized for research can be simultaneously a success and a failure, depending on which patient is assessed. The overall outcome is statistical insignificance because success is lost in the noise of failure.

Treating the individual. To individualize your treatment approach, it may be useful to recast the case and treatment strategy into Shneidman’s cubic model.6 Identifying the uniquely personal drivers behind a patient’s thoughts and actions helps point toward the most effective management approach. Tailored pharmacologic treatments and psychotherapy can be used to help guide the patient away from maximum suicide risk.

Table 2

Symptom-targeted pharmacologic treatment of suicidal patients

| Drug class | Impulsive-behavioral dyscontrol | Affective dysregulation | Psychotic features |

|---|---|---|---|

| SSRIs | Self-damaging behavior, impulsivity | Mood lability/mood crashes; anger; temper outbursts | |

| Antipsychotics | Anger, temper outbursts | Cognitive symptoms; perceptual symptoms | |

| Mood stabilizers (lithium, carbamazepine, valproic acid) | Self-damaging behavior, impulsivity | Mood lability/mood crashes, anger, temper outbursts | |

| SSRI: selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor | |||

| Source: References 16,17 | |||

Treatment of suicide attempt survivors has dramatically increased in the United States since 1990, but the incidence of suicidal thoughts, plans, gestures, or attempts has not significantly decreased.18 A systematic review of 15 randomized controlled trials using the search methods published by Arensman et al19 reveals very little difference in the suicide reattempt rate, despite extra treatment beyond the “usual standard of care.”

Intervention strategies shown to significantly decrease the rate of self-harm include home visits, behavioral therapy, and a “green card” strategy (patients were issued a card at the time of discharge explaining that a doctor was always available for them and how that doctor could be contacted).20-23

No significant difference in reattempt rate was found with other strategies, although benefits such as lower rates of depression and suicidal ideation or higher outpatient visit attendance were observed in some trials.24-26 Click here for a summary of the studies’ methodologies and results.

Outcomes of self-harm

When considering outcomes of SA, it is important to separate the short-term outcome of a single SA from the long-term outcome of suicidality. Short-term outcome depends on the characteristics and management of the acute episode, whereas long-term encompasses ongoing management of suicidality as a trait.

In the short term, surviving a SA depends heavily on the lethality of method and access to acute treatment. It also depends on medical fitness to withstand injury, which may help account for the higher death rate among elderly suicide attempters. A frail or medically ill person is less likely to survive the bodily insult of a SA.

Long-term outcomes are harder to predict. Some patients’ index attempts result from a transient state—an isolated incident that never will be repeated. In others, suicidality is a trait—a chronic maladaptive pattern that is potentially lethal. After an index attempt, the most reliable predictors for eventual death by suicide are:

- diagnosed mental illness

- high-lethality method on the index SA

- number of reattempts.4

Mood disorders impact long-term outcome, yet only a limited number of studies have found a reduction in suicide rates in response to mood disorder treatment. In a 44-year follow-up study, long-term treatment of depression and bipolar disorder with lithium significantly reduced the suicide rate.30 A meta-analysis of recurrent major affective disorder studies found that subjects on lithium maintenance treatment were 15 times less likely to commit suicidal acts, compared with those not on lithium.31

An important confounding factor in these findings is that effective lithium treatment requires long-term adherence, which implies a long-term doctor-patient relationship. As Cipriani et al32 noted, patients who can maintain an ongoing therapeutic relationship may be “less disturbed” than those who cannot, making them less likely to kill themselves regardless of pharmacologic treatment. Furthermore, patient interviews reveal that the therapeutic alliance created by a continuous relationship can be a protective support against further SA.33

Clinical implications

Suicide survivors often continue to struggle with suicidality well beyond the index attempt. This suicidality is a maladaptive problem-solving method that functions as a chronic morbid illness. As such, it is not enough to analyze the phenomenon of surviving an SA; one must examine the ongoing process of surviving suicidality.

Consider 3 factors. Consider all 3 factors— motive, method, and management—when addressing suicide survivorship.

Method lethality significantly influences survival likelihood. In clinical practice, we have observed that the index attempt is a learning experience for some patients that will inform their choice of method on the next attempt. When interacting with a suicide survivor, carefully assess the reasoning behind their initial choice of method and whether it has evolved toward higher lethality since the index attempt.

Management recommendations after SA continue to evolve. Risk factor management—such as treating underlying mood disorders, home visits to reduce social isolation, and prioritized “green card” contact with psychiatrists—has been shown to decrease reattempt rates, but many other interventions have not shown the expected benefit. Increased intervention rates have not yielded proportional decreases in suicidal ideation, attempts, or completion.

Suicide survivors often continue to struggle with suicidality well beyond the index attempt

Consider the SA motive and method when planning how to manage the survivor

Method lethality significantly influences survival likelihood (firearms are the most common and deadly method in the United States)

In many clinical trials, the incidence of suicidal thoughts, plans, gestures, or attempts has not significantly decreased when SA survivors received extra treatment

Management recommendations after SA continue to evolve; effective techniques appear to be keeping lines of communication open and providing individualized treatment

Individualize pharmacologic treatments and psychotherapy to help guide the patient away from maximum suicide risk

SA: suicide attempt

- American Association of Suicidology. www.suicidology.org.

- American Foundation for Suicide Prevention. www.afsp.org.

- Mayo Clinic Patient/Family Education. Suicide: What to do when someone is suicidal. www.mayoclinic.com/health/suicide/MH00058.

- Carbamazepine • Carbatrol

- Lithium • Eskalith, Lithobid

- Valproic acid • Depakene, Depakote

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Gardner DL, Cowdry RW. Suicidal and parasuicidal behavior in borderline personality disorder. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 1985;8(2):389-403.

2. Bostwick J, Levenson J. Suicidality. In: Levenson J, ed. The American Psychiatric Publishing textbook of psychosomatic medicine. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc; 2004:219-234.

3. Bostwick JM, Cohen LM. Differentiating suicide from life-ending acts and end-of-life decisions: a model based on chronic kidney disease and dialysis. Psychosomatics. 2009;50(1):1-7.

4. Jeglic EL. Will my patient attempt suicide again? Current Psychiatry. 2008;7(11):19-28.

5. Beautrais A. A case control study of suicide and attempted suicide. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2002;32(1):1-9.