User login

Pruritic rash and nocturnal itching

A 62-YEAR-OLD HISPANIC WOMAN with a history of well-controlled diabetes and hypertension presented with an intensely pruritic rash of 3 months’ duration. She reported poor sleep due to scratching throughout the night. She denied close contact with individuals with similar rashes or itching, new intimate partners, or recent travel. She worked in an office setting and had stable, noncrowded housing.

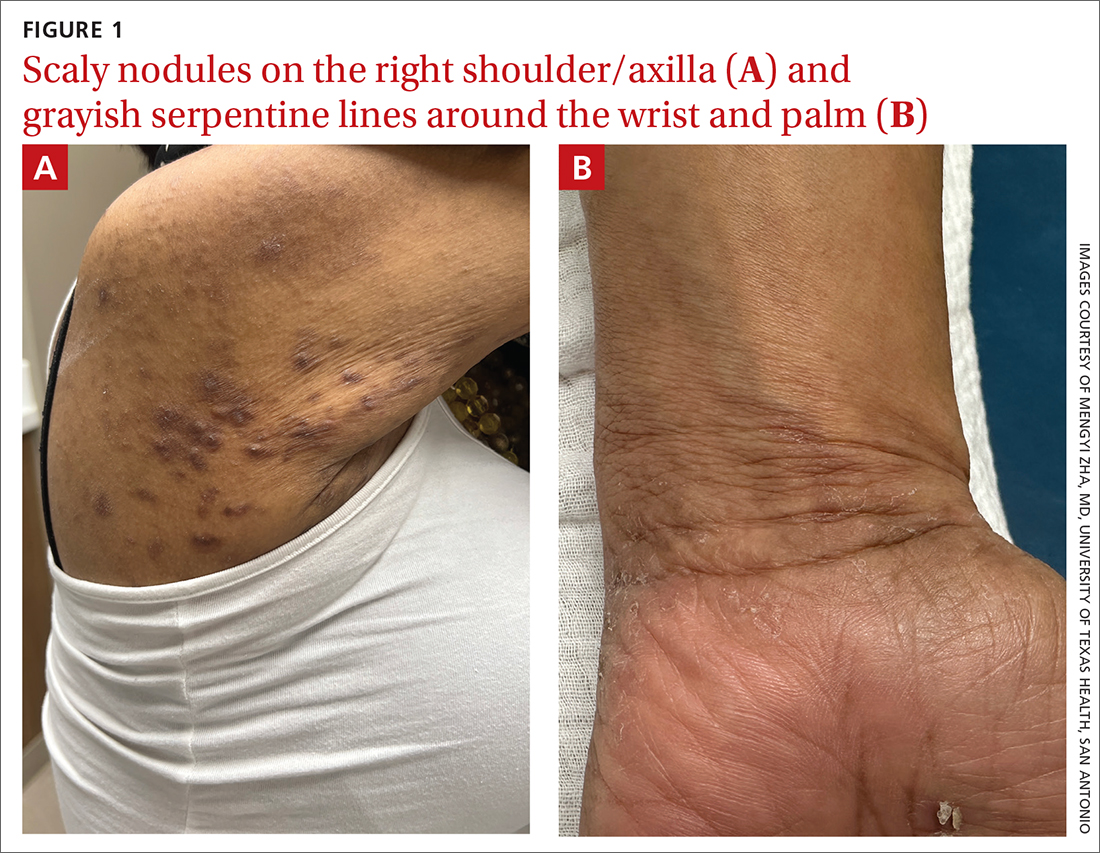

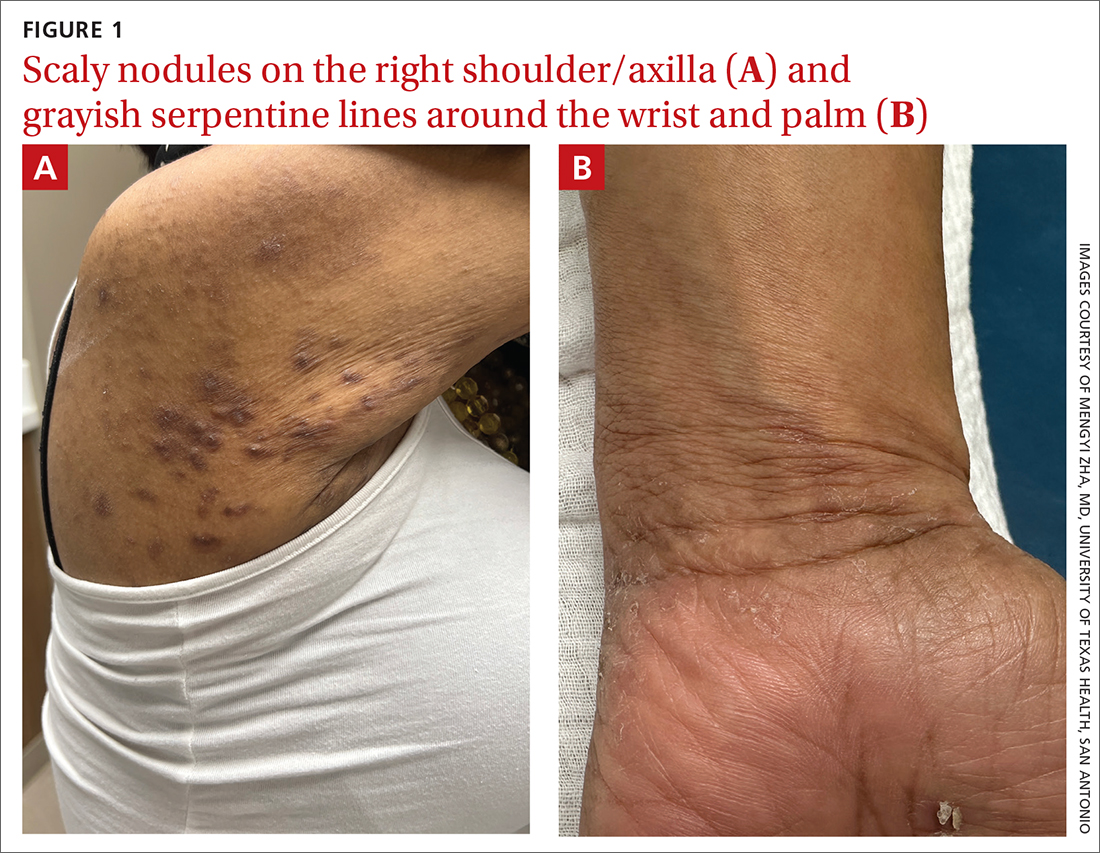

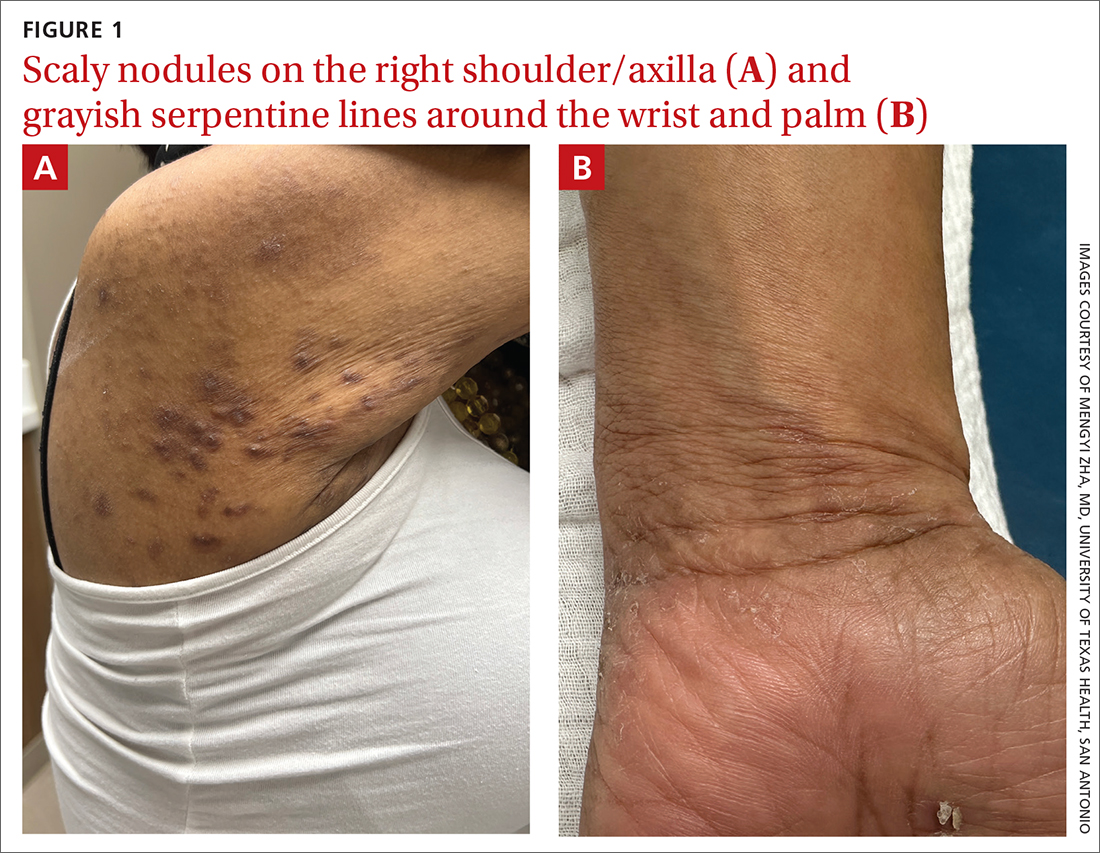

A physical exam revealed brown and purple scaly papules and many excoriation marks. The rash was concentrated along clothing lines, around intertriginous areas, and on her ankles, wrists, and the interdigital spaces (FIGURE 1A and 1B).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Scabies

Scabies is a diagnosis that should be considered in any patient with new-onset, widespread, nocturnal-dominant pruritus1 and it was suspected, in this case, after the initial history taking and physical exam. (See “Consider these diagnoses in cases of pruritic skin conditions” for more on lichen planus and prurigo nodularis, which were also included in the differential diagnosis.)

SIDEBAR

Consider these diagnoses in cases of pruritic skin conditions

Lichen planus is a chronic inflammatory condition that mostly affects the skin and mucosa. Characteristic findings are groups of shiny, flat-topped, firm papules. This patient’s widespread nodular lesions with rough scales were not typical of lichen planus, which usually manifests with flat (hence the name “planus”) and shiny lesions.

Prurigo nodularis is a chronic condition that manifests as intensely itchy, firm papules. The lesions can appear anywhere on the body, but more commonly are found on the extremities, back, and torso. The recent manifestation of the patient’s lesions and her lack of a history of chronic dermatitis argued against this diagnosis.

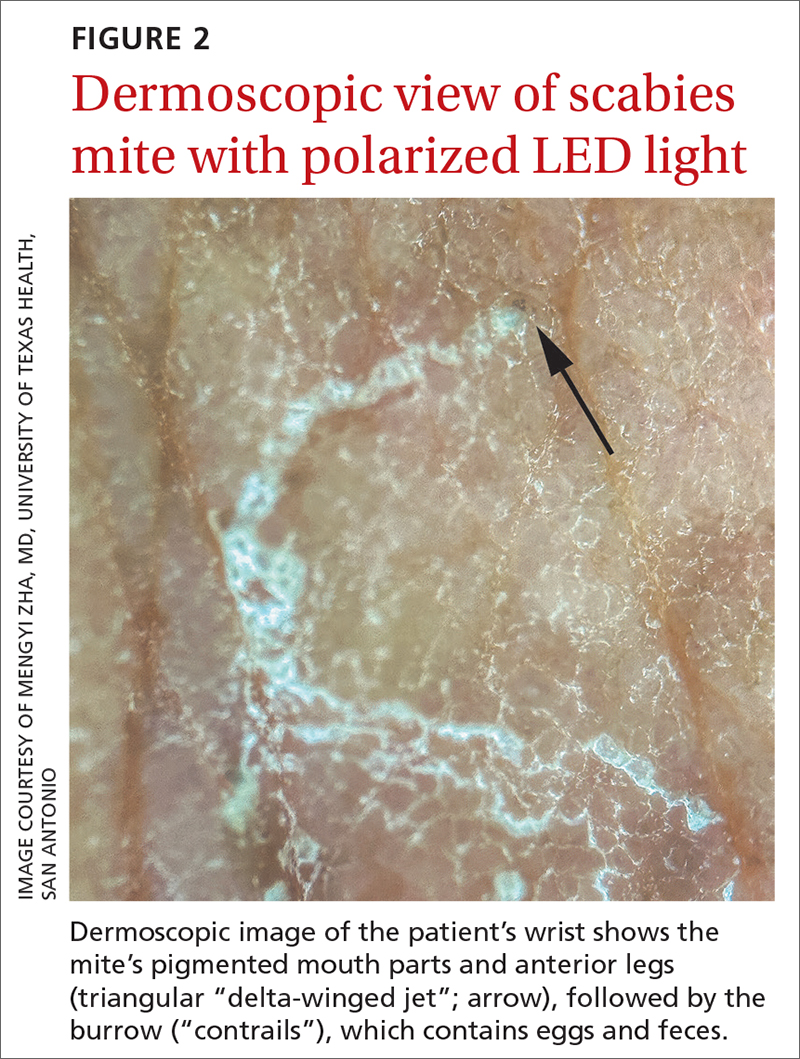

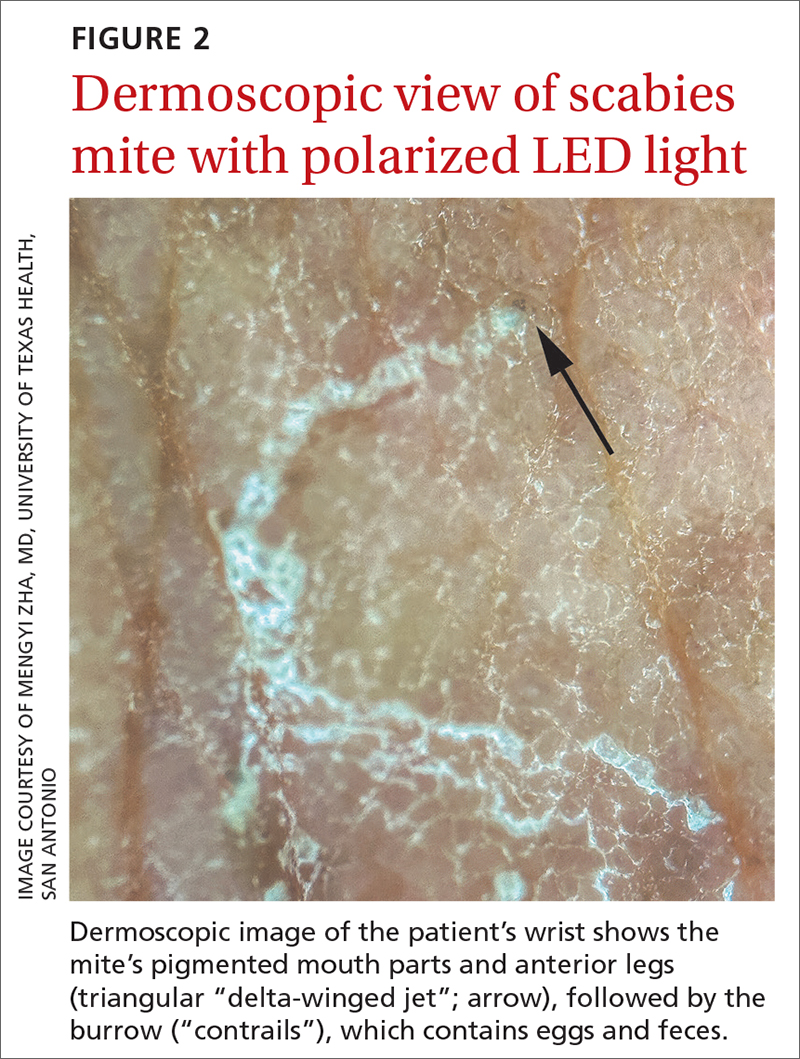

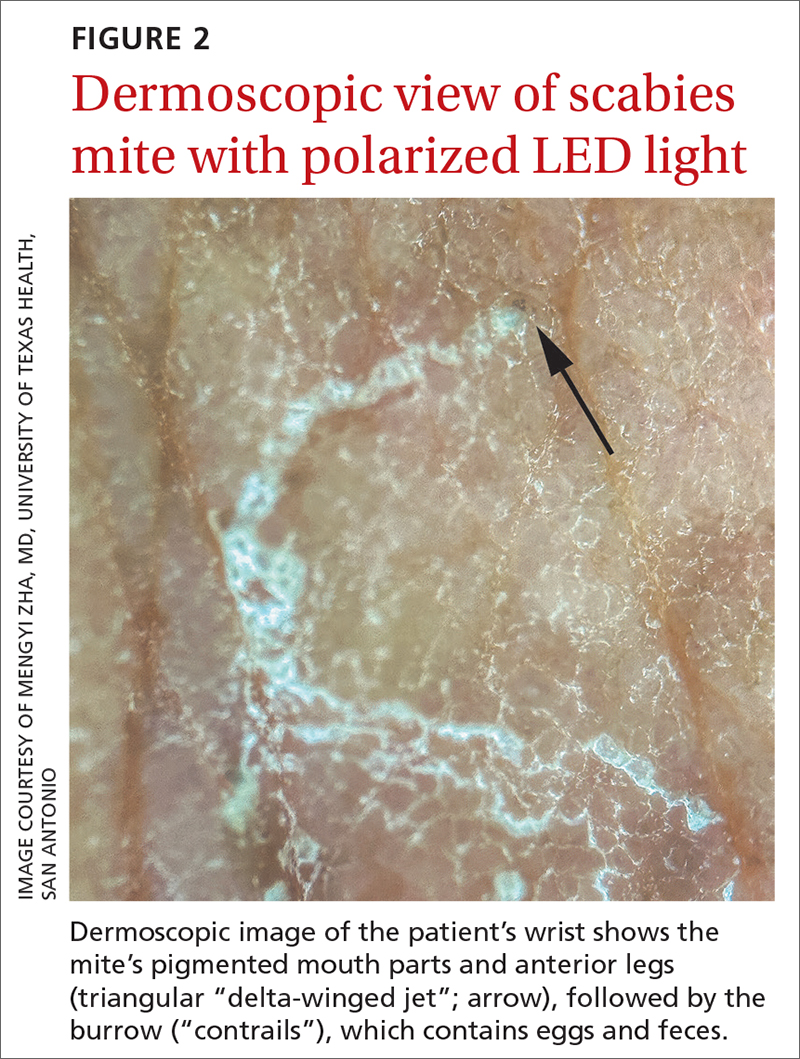

The use of a handheld dermatoscope confirmed the diagnosis by revealing white to yellow scales following the serpiginous lines. These serpiginous lines resembled scabies burrows, and at the end of some burrows, small triangular and hyperpigmented structures resembling “delta-winged jets” were seen. These “delta-winged jets” were the mite’s pigmented mouth parts and anterior legs. The burrows, which contain eggs and feces, have been described as the “contrails” behind the jets (FIGURE 2).

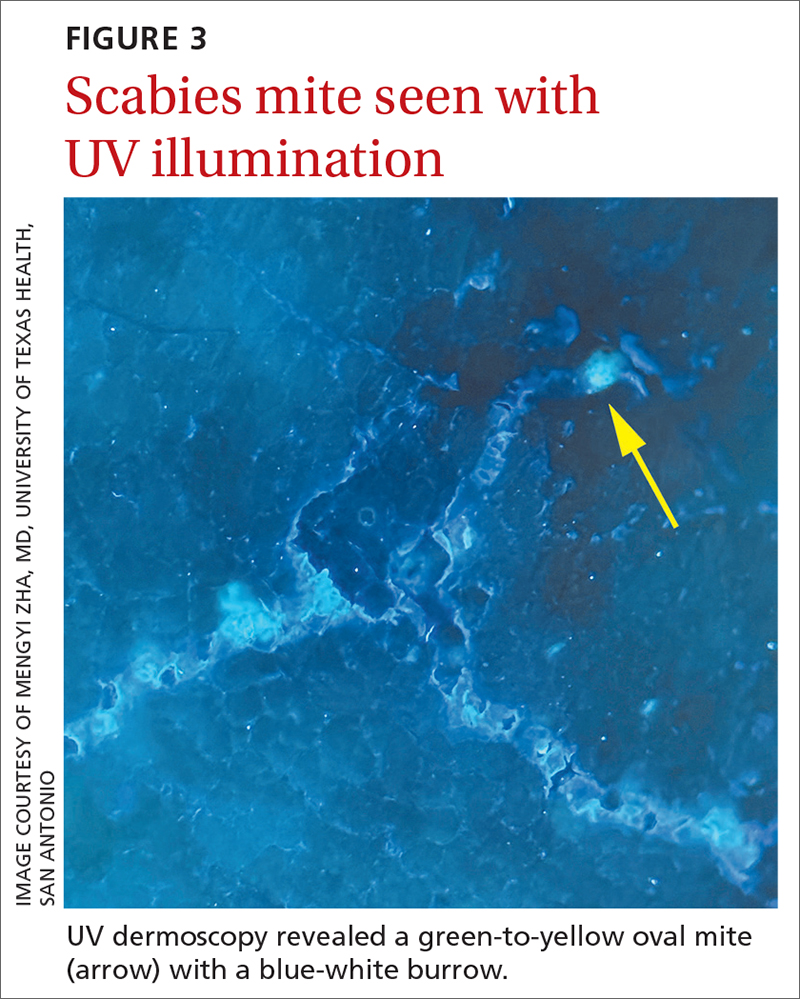

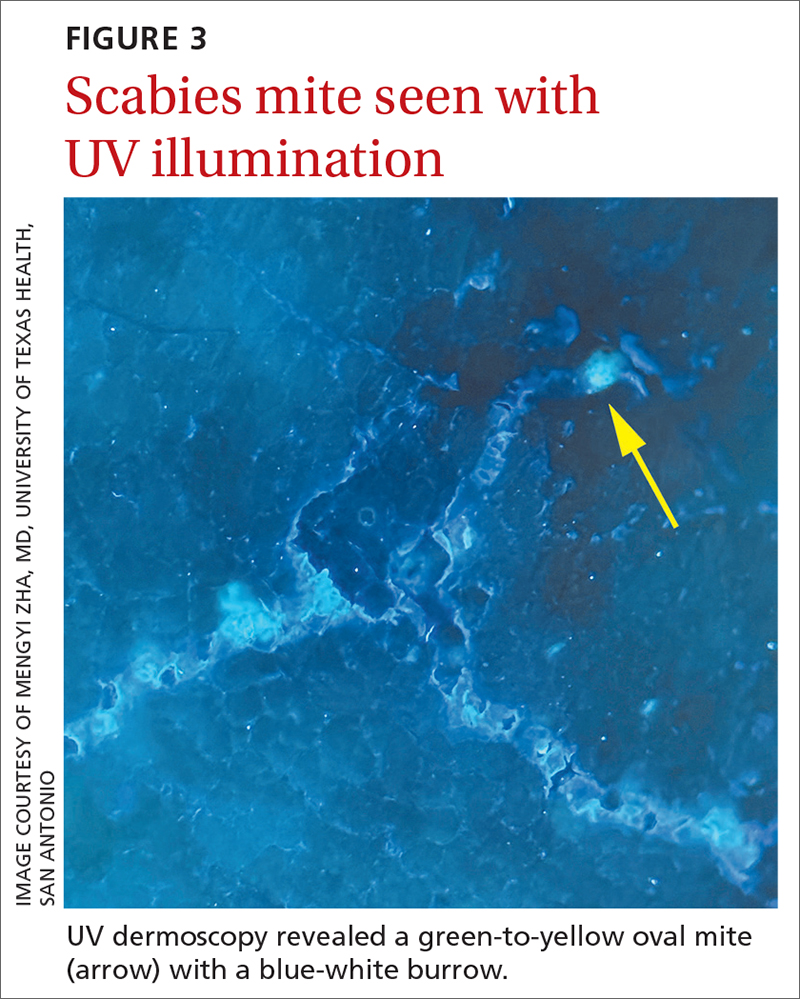

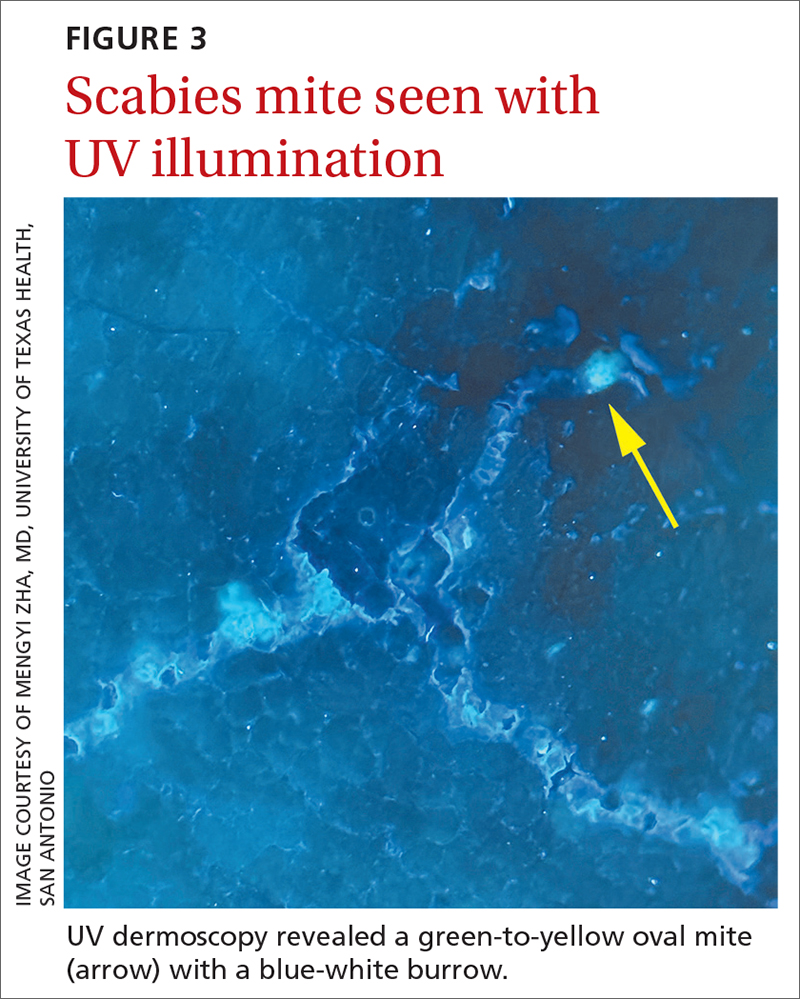

The use of a new UV illumination feature on our dermatoscope (which we’ll describe shortly) made for an even more dramatic diagnostic visual. With the click of a button, the mites fluoresced green to yellow and the burrows fluoresced white to blue (FIGURE 3).

Meeting the criteria. The clinical and dermoscopic findings met the 2020 International Alliance for the Control of Scabies (IACS) Consensus Criteria for the Diagnosis of Scabies,2 confirming the diagnosis in this patient. Scabies infestation poses a significant public health burden globally, with an estimated incidence of more than 454 million in 2016.3

Visualization is key to the diagnosis

Traditionally, the diagnosis of scabies infestation is made by direct visualization of mites via microscopy of skin scrapings.4 However, this approach is seldom feasible in a family medicine office. Fortunately, the 2020 IACS criteria included dermoscopy as a Level A diagnostic method for confirmed scabies.

Continue to: The pros and cons of dermoscopy

The pros and cons of dermoscopy. A handheld dermatoscope is an accessible, convenient tool for any clinician who treats the skin. It has been demonstrated that, in the hands of experts and novices alike, dermoscopy has a sensitivity of 91% and specificity of 86% for the diagnosis of scabies.5

However, accurate identification of the dermoscopic findings can depend on the operator and can be harder to achieve in patients who have skin of color.2 This is largely because the mite’s brown-to-black triangular head is small (sometimes hidden under skin scales) and easy to miss, especially against darker skin.

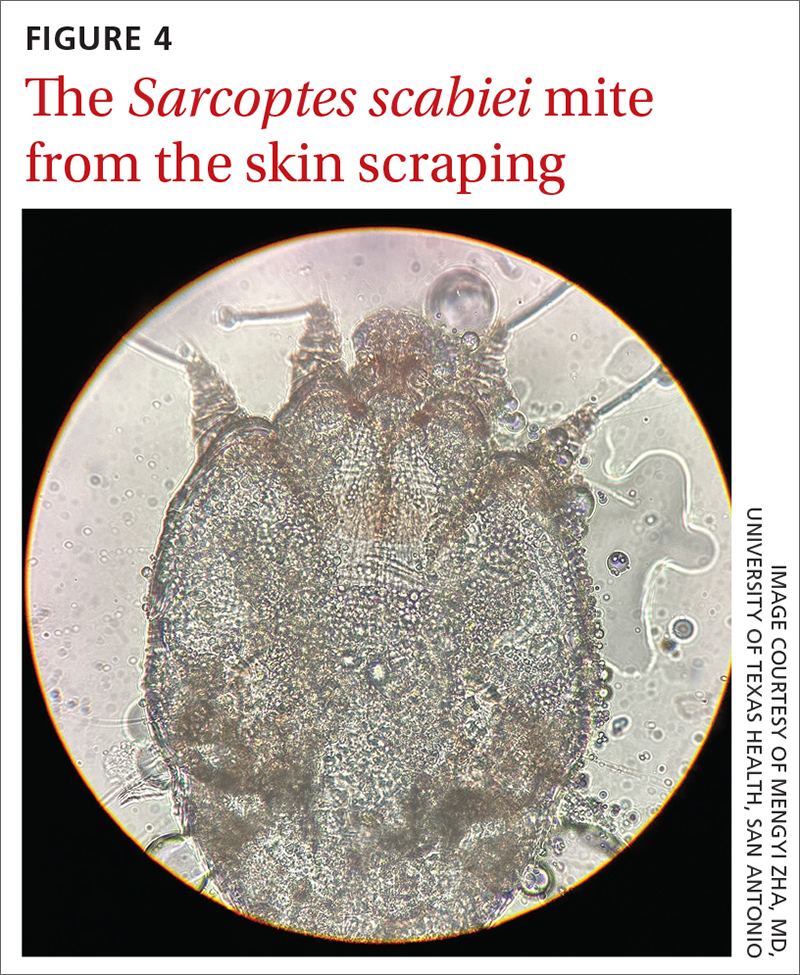

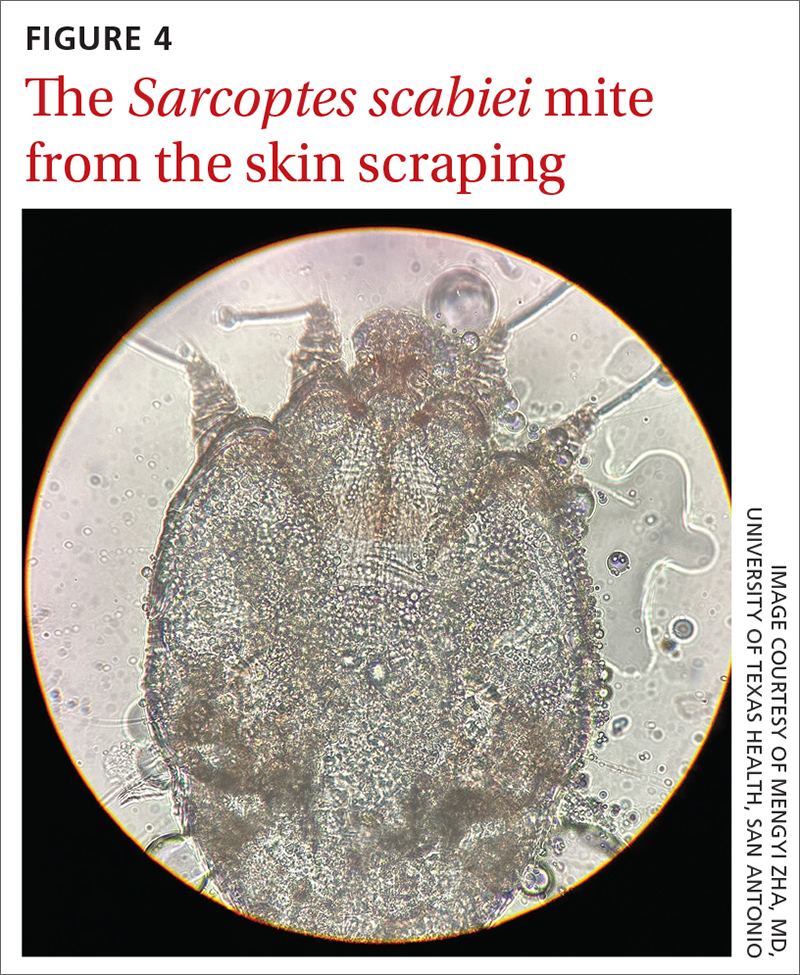

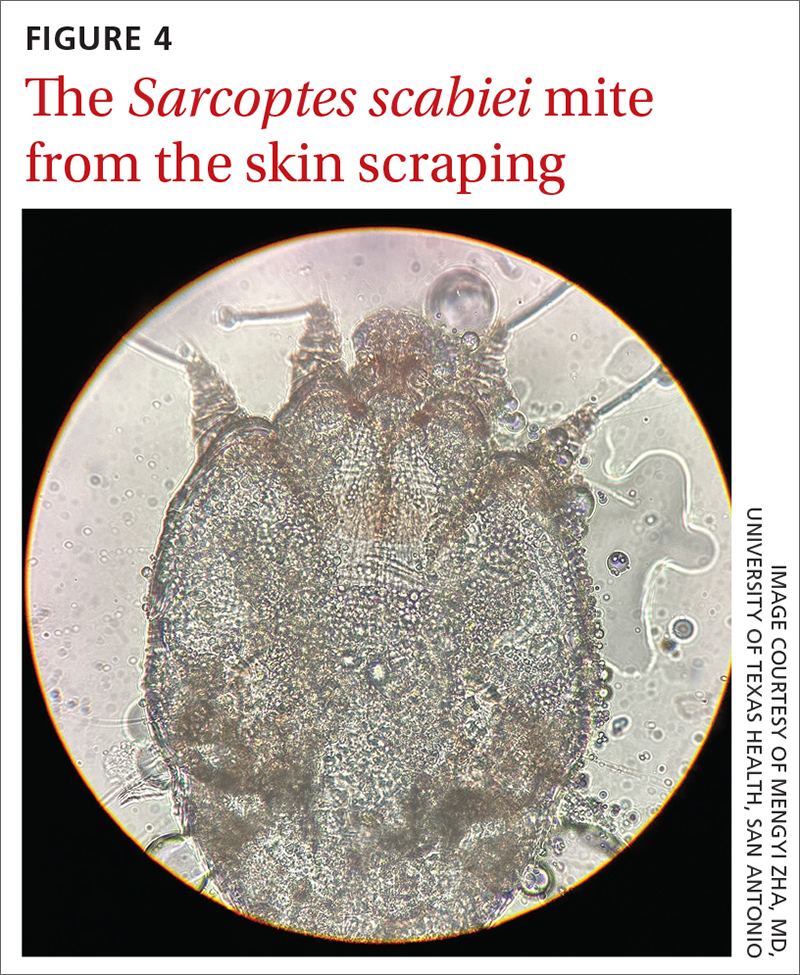

A new technologic feature helps. In this case, we used the built-in 365-nm UV illumination feature of our handheld dermatoscope (Dermlite-5) and both mites and burrows fluoresced intensely (FIGURE 3). A skin scraping at the location of the fluorescent body under microscopic examination confirmed that the organism was a Sarcoptes scabiei mite (FIGURE 4).

UV light dermoscopy can decrease operator error and ameliorate the challenge of diagnosing scabies in skin of color. Specifically, when using UV dermoscopy it’s easier to:

- locate mites, regardless of the patient’s skin color

- see the mite’s entire body, rather than just a small portion (thus increasing diagnostic certainty).

New diagnostic feature, classic treatment

Due to the severity of the patient’s scabies, she was prescribed both permethrin 5% cream and oral ivermectin 200 mcg/kg, both to be used immediately and repeated in 1 week. Notably, a systematic review indicated that topical permethrin is a superior treatment to oral ivermectin.6 However, in cases of widespread scabies and crusted scabies, it is standard of care to treat with both medications.

The patient’s pruritus was treated with cetirizine as needed. She was told that the itching might persist for a few weeks after treatment was completed.

Reinfestation was a concern with this patient because she was unable to identify a source for the mites. To minimize the likelihood of reinfestation, we advised her to decontaminate her bedding, clothing, and towels by washing them in hot water (≥ 122° F) or placing in a sealed plastic bag for at least 1 week.1 For crusted scabies cases, thorough vacuuming of a patient’s furniture and carpets is recommended.

1. Gunning K, Kiraly B, Pippitt K. Lice and scabies: treatment update. Am Fam Physician. 2019;99:635-642.

2. Engelman D, Yoshizumi J, Hay RJ, et al. The 2020 International Alliance for the Control of Scabies Consensus Criteria for the Diagnosis of Scabies. Br J Dermatol. 2020;183:808-820. doi: 10.1111/bjd.18943

A 62-YEAR-OLD HISPANIC WOMAN with a history of well-controlled diabetes and hypertension presented with an intensely pruritic rash of 3 months’ duration. She reported poor sleep due to scratching throughout the night. She denied close contact with individuals with similar rashes or itching, new intimate partners, or recent travel. She worked in an office setting and had stable, noncrowded housing.

A physical exam revealed brown and purple scaly papules and many excoriation marks. The rash was concentrated along clothing lines, around intertriginous areas, and on her ankles, wrists, and the interdigital spaces (FIGURE 1A and 1B).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Scabies

Scabies is a diagnosis that should be considered in any patient with new-onset, widespread, nocturnal-dominant pruritus1 and it was suspected, in this case, after the initial history taking and physical exam. (See “Consider these diagnoses in cases of pruritic skin conditions” for more on lichen planus and prurigo nodularis, which were also included in the differential diagnosis.)

SIDEBAR

Consider these diagnoses in cases of pruritic skin conditions

Lichen planus is a chronic inflammatory condition that mostly affects the skin and mucosa. Characteristic findings are groups of shiny, flat-topped, firm papules. This patient’s widespread nodular lesions with rough scales were not typical of lichen planus, which usually manifests with flat (hence the name “planus”) and shiny lesions.

Prurigo nodularis is a chronic condition that manifests as intensely itchy, firm papules. The lesions can appear anywhere on the body, but more commonly are found on the extremities, back, and torso. The recent manifestation of the patient’s lesions and her lack of a history of chronic dermatitis argued against this diagnosis.

The use of a handheld dermatoscope confirmed the diagnosis by revealing white to yellow scales following the serpiginous lines. These serpiginous lines resembled scabies burrows, and at the end of some burrows, small triangular and hyperpigmented structures resembling “delta-winged jets” were seen. These “delta-winged jets” were the mite’s pigmented mouth parts and anterior legs. The burrows, which contain eggs and feces, have been described as the “contrails” behind the jets (FIGURE 2).

The use of a new UV illumination feature on our dermatoscope (which we’ll describe shortly) made for an even more dramatic diagnostic visual. With the click of a button, the mites fluoresced green to yellow and the burrows fluoresced white to blue (FIGURE 3).

Meeting the criteria. The clinical and dermoscopic findings met the 2020 International Alliance for the Control of Scabies (IACS) Consensus Criteria for the Diagnosis of Scabies,2 confirming the diagnosis in this patient. Scabies infestation poses a significant public health burden globally, with an estimated incidence of more than 454 million in 2016.3

Visualization is key to the diagnosis

Traditionally, the diagnosis of scabies infestation is made by direct visualization of mites via microscopy of skin scrapings.4 However, this approach is seldom feasible in a family medicine office. Fortunately, the 2020 IACS criteria included dermoscopy as a Level A diagnostic method for confirmed scabies.

Continue to: The pros and cons of dermoscopy

The pros and cons of dermoscopy. A handheld dermatoscope is an accessible, convenient tool for any clinician who treats the skin. It has been demonstrated that, in the hands of experts and novices alike, dermoscopy has a sensitivity of 91% and specificity of 86% for the diagnosis of scabies.5

However, accurate identification of the dermoscopic findings can depend on the operator and can be harder to achieve in patients who have skin of color.2 This is largely because the mite’s brown-to-black triangular head is small (sometimes hidden under skin scales) and easy to miss, especially against darker skin.

A new technologic feature helps. In this case, we used the built-in 365-nm UV illumination feature of our handheld dermatoscope (Dermlite-5) and both mites and burrows fluoresced intensely (FIGURE 3). A skin scraping at the location of the fluorescent body under microscopic examination confirmed that the organism was a Sarcoptes scabiei mite (FIGURE 4).

UV light dermoscopy can decrease operator error and ameliorate the challenge of diagnosing scabies in skin of color. Specifically, when using UV dermoscopy it’s easier to:

- locate mites, regardless of the patient’s skin color

- see the mite’s entire body, rather than just a small portion (thus increasing diagnostic certainty).

New diagnostic feature, classic treatment

Due to the severity of the patient’s scabies, she was prescribed both permethrin 5% cream and oral ivermectin 200 mcg/kg, both to be used immediately and repeated in 1 week. Notably, a systematic review indicated that topical permethrin is a superior treatment to oral ivermectin.6 However, in cases of widespread scabies and crusted scabies, it is standard of care to treat with both medications.

The patient’s pruritus was treated with cetirizine as needed. She was told that the itching might persist for a few weeks after treatment was completed.

Reinfestation was a concern with this patient because she was unable to identify a source for the mites. To minimize the likelihood of reinfestation, we advised her to decontaminate her bedding, clothing, and towels by washing them in hot water (≥ 122° F) or placing in a sealed plastic bag for at least 1 week.1 For crusted scabies cases, thorough vacuuming of a patient’s furniture and carpets is recommended.

A 62-YEAR-OLD HISPANIC WOMAN with a history of well-controlled diabetes and hypertension presented with an intensely pruritic rash of 3 months’ duration. She reported poor sleep due to scratching throughout the night. She denied close contact with individuals with similar rashes or itching, new intimate partners, or recent travel. She worked in an office setting and had stable, noncrowded housing.

A physical exam revealed brown and purple scaly papules and many excoriation marks. The rash was concentrated along clothing lines, around intertriginous areas, and on her ankles, wrists, and the interdigital spaces (FIGURE 1A and 1B).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Scabies

Scabies is a diagnosis that should be considered in any patient with new-onset, widespread, nocturnal-dominant pruritus1 and it was suspected, in this case, after the initial history taking and physical exam. (See “Consider these diagnoses in cases of pruritic skin conditions” for more on lichen planus and prurigo nodularis, which were also included in the differential diagnosis.)

SIDEBAR

Consider these diagnoses in cases of pruritic skin conditions

Lichen planus is a chronic inflammatory condition that mostly affects the skin and mucosa. Characteristic findings are groups of shiny, flat-topped, firm papules. This patient’s widespread nodular lesions with rough scales were not typical of lichen planus, which usually manifests with flat (hence the name “planus”) and shiny lesions.

Prurigo nodularis is a chronic condition that manifests as intensely itchy, firm papules. The lesions can appear anywhere on the body, but more commonly are found on the extremities, back, and torso. The recent manifestation of the patient’s lesions and her lack of a history of chronic dermatitis argued against this diagnosis.

The use of a handheld dermatoscope confirmed the diagnosis by revealing white to yellow scales following the serpiginous lines. These serpiginous lines resembled scabies burrows, and at the end of some burrows, small triangular and hyperpigmented structures resembling “delta-winged jets” were seen. These “delta-winged jets” were the mite’s pigmented mouth parts and anterior legs. The burrows, which contain eggs and feces, have been described as the “contrails” behind the jets (FIGURE 2).

The use of a new UV illumination feature on our dermatoscope (which we’ll describe shortly) made for an even more dramatic diagnostic visual. With the click of a button, the mites fluoresced green to yellow and the burrows fluoresced white to blue (FIGURE 3).

Meeting the criteria. The clinical and dermoscopic findings met the 2020 International Alliance for the Control of Scabies (IACS) Consensus Criteria for the Diagnosis of Scabies,2 confirming the diagnosis in this patient. Scabies infestation poses a significant public health burden globally, with an estimated incidence of more than 454 million in 2016.3

Visualization is key to the diagnosis

Traditionally, the diagnosis of scabies infestation is made by direct visualization of mites via microscopy of skin scrapings.4 However, this approach is seldom feasible in a family medicine office. Fortunately, the 2020 IACS criteria included dermoscopy as a Level A diagnostic method for confirmed scabies.

Continue to: The pros and cons of dermoscopy

The pros and cons of dermoscopy. A handheld dermatoscope is an accessible, convenient tool for any clinician who treats the skin. It has been demonstrated that, in the hands of experts and novices alike, dermoscopy has a sensitivity of 91% and specificity of 86% for the diagnosis of scabies.5

However, accurate identification of the dermoscopic findings can depend on the operator and can be harder to achieve in patients who have skin of color.2 This is largely because the mite’s brown-to-black triangular head is small (sometimes hidden under skin scales) and easy to miss, especially against darker skin.

A new technologic feature helps. In this case, we used the built-in 365-nm UV illumination feature of our handheld dermatoscope (Dermlite-5) and both mites and burrows fluoresced intensely (FIGURE 3). A skin scraping at the location of the fluorescent body under microscopic examination confirmed that the organism was a Sarcoptes scabiei mite (FIGURE 4).

UV light dermoscopy can decrease operator error and ameliorate the challenge of diagnosing scabies in skin of color. Specifically, when using UV dermoscopy it’s easier to:

- locate mites, regardless of the patient’s skin color

- see the mite’s entire body, rather than just a small portion (thus increasing diagnostic certainty).

New diagnostic feature, classic treatment

Due to the severity of the patient’s scabies, she was prescribed both permethrin 5% cream and oral ivermectin 200 mcg/kg, both to be used immediately and repeated in 1 week. Notably, a systematic review indicated that topical permethrin is a superior treatment to oral ivermectin.6 However, in cases of widespread scabies and crusted scabies, it is standard of care to treat with both medications.

The patient’s pruritus was treated with cetirizine as needed. She was told that the itching might persist for a few weeks after treatment was completed.

Reinfestation was a concern with this patient because she was unable to identify a source for the mites. To minimize the likelihood of reinfestation, we advised her to decontaminate her bedding, clothing, and towels by washing them in hot water (≥ 122° F) or placing in a sealed plastic bag for at least 1 week.1 For crusted scabies cases, thorough vacuuming of a patient’s furniture and carpets is recommended.

1. Gunning K, Kiraly B, Pippitt K. Lice and scabies: treatment update. Am Fam Physician. 2019;99:635-642.

2. Engelman D, Yoshizumi J, Hay RJ, et al. The 2020 International Alliance for the Control of Scabies Consensus Criteria for the Diagnosis of Scabies. Br J Dermatol. 2020;183:808-820. doi: 10.1111/bjd.18943

1. Gunning K, Kiraly B, Pippitt K. Lice and scabies: treatment update. Am Fam Physician. 2019;99:635-642.

2. Engelman D, Yoshizumi J, Hay RJ, et al. The 2020 International Alliance for the Control of Scabies Consensus Criteria for the Diagnosis of Scabies. Br J Dermatol. 2020;183:808-820. doi: 10.1111/bjd.18943