User login

Erythrasma

THE COMPARISON

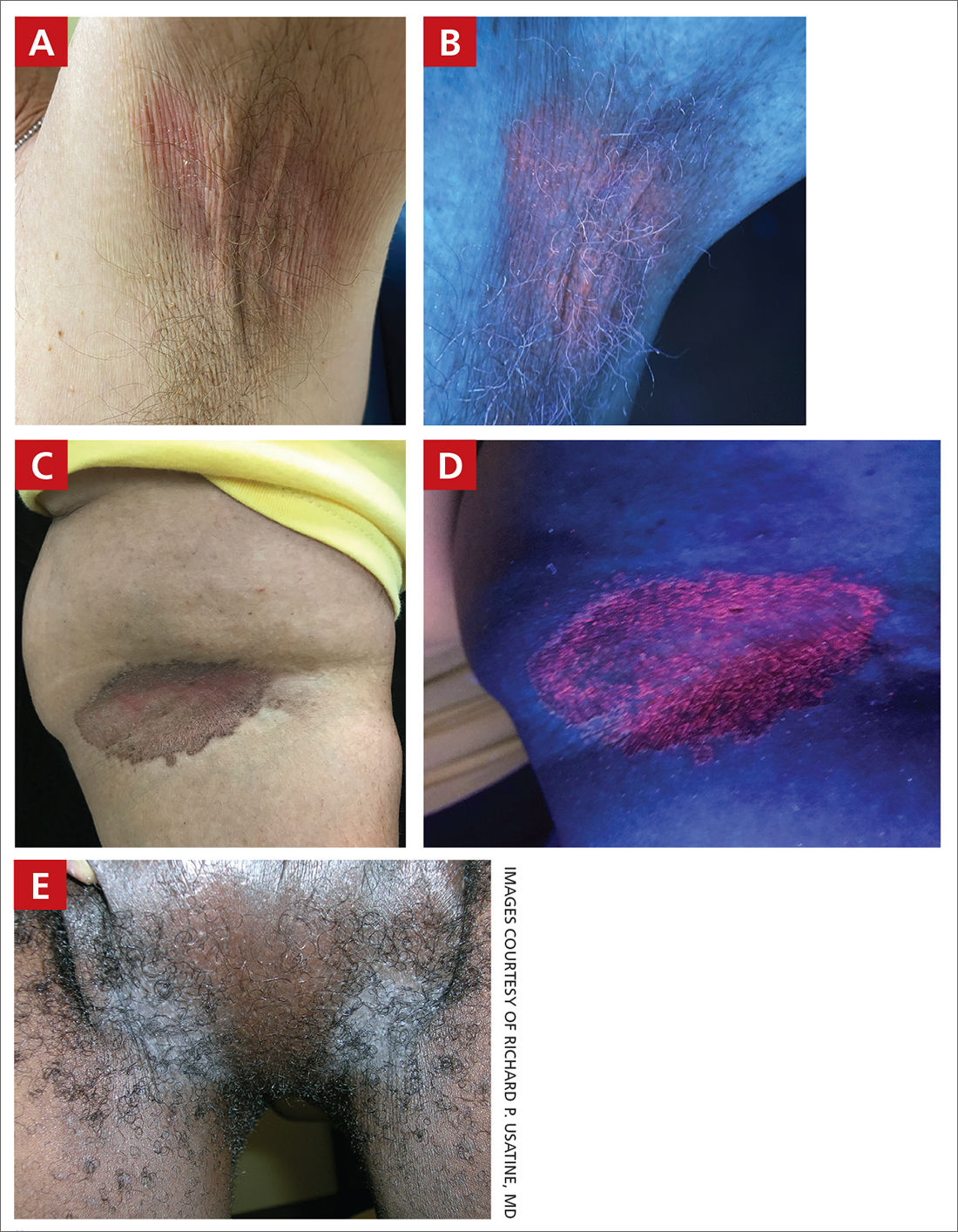

A and B Axilla of a 65-year-old White man with erythrasma showing a well-demarcated erythematous plaque with fine scale (A). Wood-lamp examination of the area showed characteristic bright coral red fluorescence (B).

C and D A well-demarcated, red-brown plaque with fine scale in the antecubital fossa of an obese Hispanic woman (C). Wood-lamp examination revealed bright coral red fluorescence (D).

E Hypopigmented patches (with pruritus) in the groin of a Black man. He also had erythrasma between the toes.

Erythrasma is a skin condition caused by acute or chronic infection of the outermost layer of the epidermis (stratum corneum) with Corynebacterium minutissimum. It has a predilection for intertriginous regions such as the axillae, groin, and interdigital spaces of the toes. It can be associated with pruritus or can be asymptomatic.

Epidemiology

Erythrasma typically affects adults, with greater prevalence among those residing in shared living facilities, such as dormitories or nursing homes, or in humid climates.1 It is a common disorder with an estimated prevalence of 17.6% of bacterial skin infections in elderly patients and 44% of diabetic interdigital toe space infections.2,3

Key clinical features

Erythrasma can manifest as red-brown hyperpigmented plaques with fine scale and little central clearing (FIGURES A and C) or as a hypopigmented patch (FIGURE E) with a sharply marginated, hyperpigmented border in patients with skin of color. In the interdigital toe spaces, the skin often is white and macerated. These findings may appear in patients of all skin tones.

Worth noting

- C minutissimum produces coproporphyrin III, which glows fluorescent red under Wood-lamp examination (FIGURES B and D). A recent shower or bath may remove the fluorescent coproporphyrins and cause a false-negative result. The interdigital space between the fourth and fifth toes is a common location for C minutissimum; thus clinicians should consider examining these areas with a Wood lamp.

- Associated risk factors include obesity, immunosuppression, diabetes mellitus, and excessive sweating.1

- The differential diagnosis includes intertrigo, inverse psoriasis, confluent and reticulated papillomatosis (Gougerot-Carteaud syndrome), acanthosis nigricans, seborrheic dermatitis, and tinea pedis when present in the interdigital toe spaces. Plaques occurring in circular patterns may be mistaken for tinea corporis or pityriasis rotunda.

- There is a high prevalence of erythrasma in patients with inverse psoriasis, and it may exacerbate psoriatic plaques.4

- Treatment options include application of topical clindamycin or erythromycin to the affected area.1 Some patients have responded to topical mupiricin.2 For larger areas, a 1-g dose of clarithromycin5 or a 14-day course of erythromycin may be appropriate.1 Avoid prescribing clarithromycin to patients with preexisting heart disease due to its increased risk for cardiac events or death; consider other agents.

Health disparity highlight

Obesity, most prevalent in non-Hispanic Black adults (49.9%) and Hispanic adults (45.6%) followed by non-Hispanic White adults (41.4%),6 may cause velvety dark plaques on the neck called acanthosis nigricans. However, acute or chronic erythrasma also may cause hyperpigmentation of the body folds. Although the pathology of erythrasma is due to bacterial infection of the superficial layer of the stratum corneum, acanthosis nigricans is due to fibroblast proliferation and stimulation of epidermal keratinocytes, likely from increased growth factors and insulinlike growth factor.7 If erythrasma is mistaken for acanthosis nigricans, the patient may be counseled inappropriately that the hyperpigmentation is something not easily resolved and subsequently left with an active treatable condition that adversely affects their quality of life.

1. Groves JB, Nassereddin A, Freeman AM. Erythrasma. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; August 11, 2021. Accessed November 17, 2022. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK513352/

2. Forouzan P, Cohen PR. Erythrasma revisited: diagnosis, differential diagnoses, and comprehensive review of treatment. Cureus. 2020;12:E10733. doi:10.7759/cureus.10733

3. Polat M, I˙lhan MN. Dermatological complaints of the elderly attending a dermatology outpatient clinic in Turkey: a prospective study over a one-year period. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat. 2015;23:277-281.

4. Janeczek M, Kozel Z, Bhasin R, et al. High prevalence of erythrasma in patients with inverse psoriasis: a cross-sectional study. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2020;13:12-14.

5. Khan MJ. Interdigital pedal erythrasma treated with one-time dose of oral clarithromycin 1 g: two case reports. Clin Case Rep. 2020;8:672-674. doi:10.1002/ccr3.2712

6. Stierman B, Afful J, Carroll M, et al. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2017–March 2020 Prepandemic Data Files Development of Files and Prevalence Estimates for Selected Health Outcomes. National Health Statistics Reports. Published June 14, 2021. Accessed November 17, 2022. https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/106273

7. Brady MF, Rawla P. Acanthosis nigricans. In: StatPearls. Stat- Pearls Publishing; 2022. Updated October 9, 2022. Accessed November 30, 2022. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK431057

THE COMPARISON

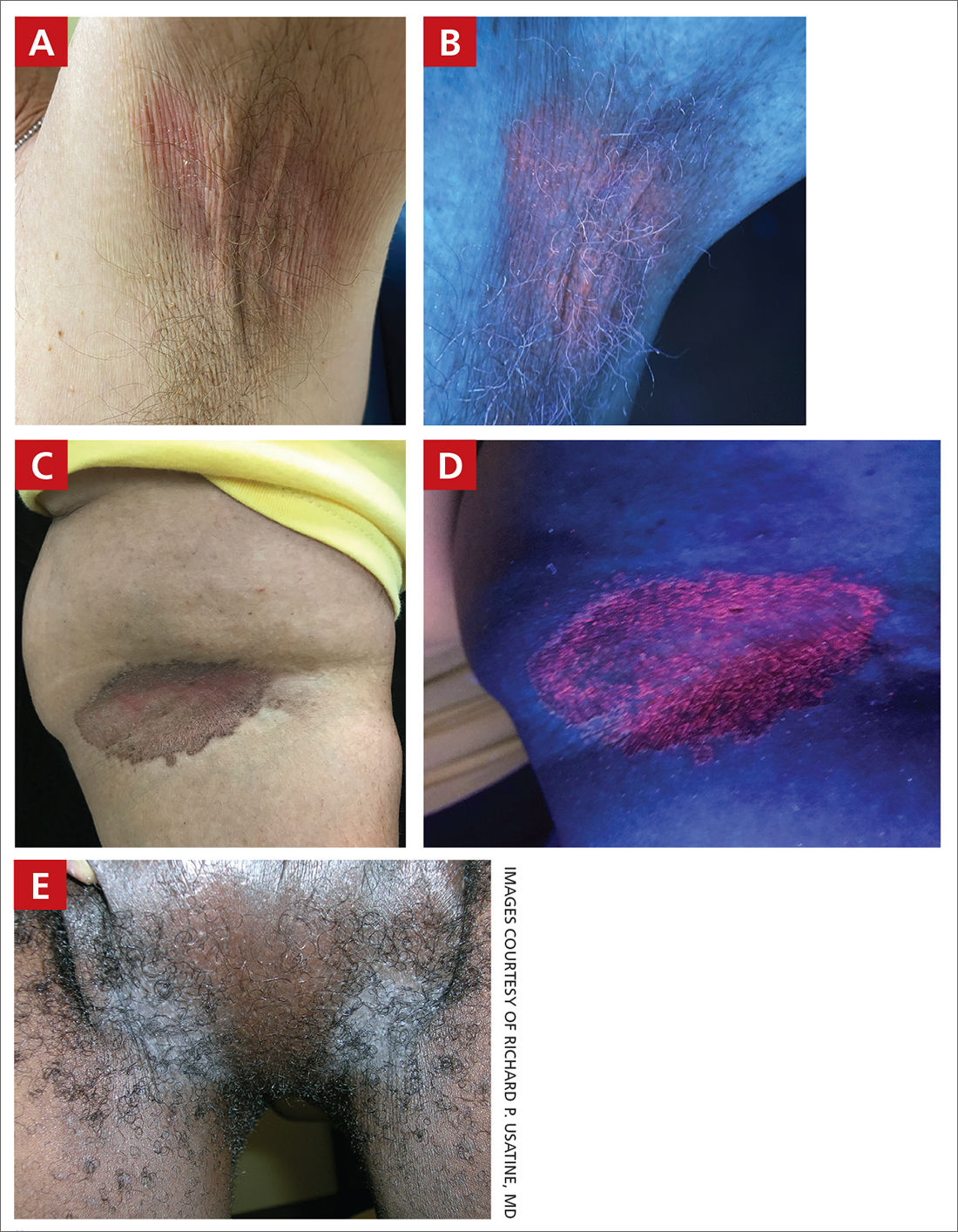

A and B Axilla of a 65-year-old White man with erythrasma showing a well-demarcated erythematous plaque with fine scale (A). Wood-lamp examination of the area showed characteristic bright coral red fluorescence (B).

C and D A well-demarcated, red-brown plaque with fine scale in the antecubital fossa of an obese Hispanic woman (C). Wood-lamp examination revealed bright coral red fluorescence (D).

E Hypopigmented patches (with pruritus) in the groin of a Black man. He also had erythrasma between the toes.

Erythrasma is a skin condition caused by acute or chronic infection of the outermost layer of the epidermis (stratum corneum) with Corynebacterium minutissimum. It has a predilection for intertriginous regions such as the axillae, groin, and interdigital spaces of the toes. It can be associated with pruritus or can be asymptomatic.

Epidemiology

Erythrasma typically affects adults, with greater prevalence among those residing in shared living facilities, such as dormitories or nursing homes, or in humid climates.1 It is a common disorder with an estimated prevalence of 17.6% of bacterial skin infections in elderly patients and 44% of diabetic interdigital toe space infections.2,3

Key clinical features

Erythrasma can manifest as red-brown hyperpigmented plaques with fine scale and little central clearing (FIGURES A and C) or as a hypopigmented patch (FIGURE E) with a sharply marginated, hyperpigmented border in patients with skin of color. In the interdigital toe spaces, the skin often is white and macerated. These findings may appear in patients of all skin tones.

Worth noting

- C minutissimum produces coproporphyrin III, which glows fluorescent red under Wood-lamp examination (FIGURES B and D). A recent shower or bath may remove the fluorescent coproporphyrins and cause a false-negative result. The interdigital space between the fourth and fifth toes is a common location for C minutissimum; thus clinicians should consider examining these areas with a Wood lamp.

- Associated risk factors include obesity, immunosuppression, diabetes mellitus, and excessive sweating.1

- The differential diagnosis includes intertrigo, inverse psoriasis, confluent and reticulated papillomatosis (Gougerot-Carteaud syndrome), acanthosis nigricans, seborrheic dermatitis, and tinea pedis when present in the interdigital toe spaces. Plaques occurring in circular patterns may be mistaken for tinea corporis or pityriasis rotunda.

- There is a high prevalence of erythrasma in patients with inverse psoriasis, and it may exacerbate psoriatic plaques.4

- Treatment options include application of topical clindamycin or erythromycin to the affected area.1 Some patients have responded to topical mupiricin.2 For larger areas, a 1-g dose of clarithromycin5 or a 14-day course of erythromycin may be appropriate.1 Avoid prescribing clarithromycin to patients with preexisting heart disease due to its increased risk for cardiac events or death; consider other agents.

Health disparity highlight

Obesity, most prevalent in non-Hispanic Black adults (49.9%) and Hispanic adults (45.6%) followed by non-Hispanic White adults (41.4%),6 may cause velvety dark plaques on the neck called acanthosis nigricans. However, acute or chronic erythrasma also may cause hyperpigmentation of the body folds. Although the pathology of erythrasma is due to bacterial infection of the superficial layer of the stratum corneum, acanthosis nigricans is due to fibroblast proliferation and stimulation of epidermal keratinocytes, likely from increased growth factors and insulinlike growth factor.7 If erythrasma is mistaken for acanthosis nigricans, the patient may be counseled inappropriately that the hyperpigmentation is something not easily resolved and subsequently left with an active treatable condition that adversely affects their quality of life.

THE COMPARISON

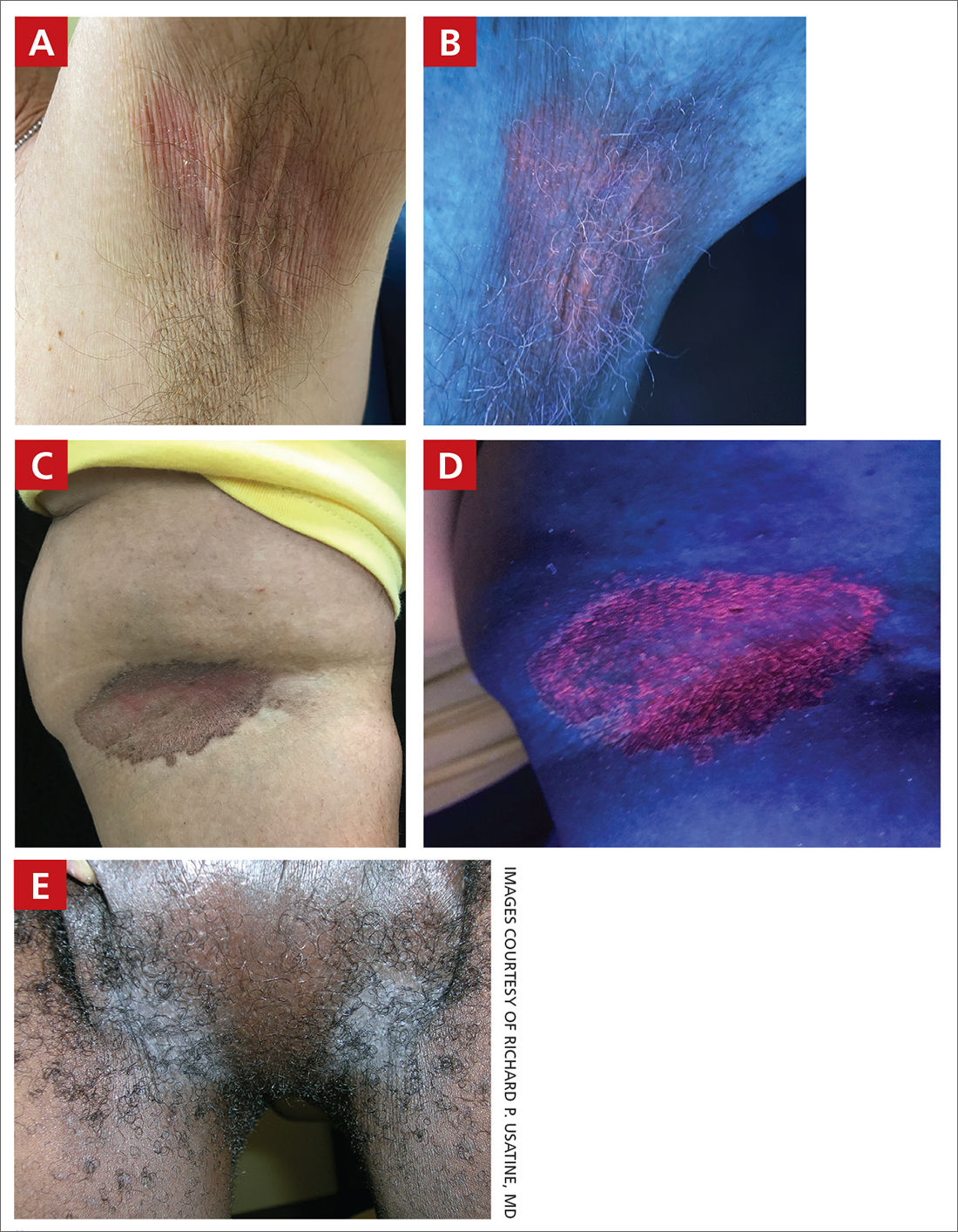

A and B Axilla of a 65-year-old White man with erythrasma showing a well-demarcated erythematous plaque with fine scale (A). Wood-lamp examination of the area showed characteristic bright coral red fluorescence (B).

C and D A well-demarcated, red-brown plaque with fine scale in the antecubital fossa of an obese Hispanic woman (C). Wood-lamp examination revealed bright coral red fluorescence (D).

E Hypopigmented patches (with pruritus) in the groin of a Black man. He also had erythrasma between the toes.

Erythrasma is a skin condition caused by acute or chronic infection of the outermost layer of the epidermis (stratum corneum) with Corynebacterium minutissimum. It has a predilection for intertriginous regions such as the axillae, groin, and interdigital spaces of the toes. It can be associated with pruritus or can be asymptomatic.

Epidemiology

Erythrasma typically affects adults, with greater prevalence among those residing in shared living facilities, such as dormitories or nursing homes, or in humid climates.1 It is a common disorder with an estimated prevalence of 17.6% of bacterial skin infections in elderly patients and 44% of diabetic interdigital toe space infections.2,3

Key clinical features

Erythrasma can manifest as red-brown hyperpigmented plaques with fine scale and little central clearing (FIGURES A and C) or as a hypopigmented patch (FIGURE E) with a sharply marginated, hyperpigmented border in patients with skin of color. In the interdigital toe spaces, the skin often is white and macerated. These findings may appear in patients of all skin tones.

Worth noting

- C minutissimum produces coproporphyrin III, which glows fluorescent red under Wood-lamp examination (FIGURES B and D). A recent shower or bath may remove the fluorescent coproporphyrins and cause a false-negative result. The interdigital space between the fourth and fifth toes is a common location for C minutissimum; thus clinicians should consider examining these areas with a Wood lamp.

- Associated risk factors include obesity, immunosuppression, diabetes mellitus, and excessive sweating.1

- The differential diagnosis includes intertrigo, inverse psoriasis, confluent and reticulated papillomatosis (Gougerot-Carteaud syndrome), acanthosis nigricans, seborrheic dermatitis, and tinea pedis when present in the interdigital toe spaces. Plaques occurring in circular patterns may be mistaken for tinea corporis or pityriasis rotunda.

- There is a high prevalence of erythrasma in patients with inverse psoriasis, and it may exacerbate psoriatic plaques.4

- Treatment options include application of topical clindamycin or erythromycin to the affected area.1 Some patients have responded to topical mupiricin.2 For larger areas, a 1-g dose of clarithromycin5 or a 14-day course of erythromycin may be appropriate.1 Avoid prescribing clarithromycin to patients with preexisting heart disease due to its increased risk for cardiac events or death; consider other agents.

Health disparity highlight

Obesity, most prevalent in non-Hispanic Black adults (49.9%) and Hispanic adults (45.6%) followed by non-Hispanic White adults (41.4%),6 may cause velvety dark plaques on the neck called acanthosis nigricans. However, acute or chronic erythrasma also may cause hyperpigmentation of the body folds. Although the pathology of erythrasma is due to bacterial infection of the superficial layer of the stratum corneum, acanthosis nigricans is due to fibroblast proliferation and stimulation of epidermal keratinocytes, likely from increased growth factors and insulinlike growth factor.7 If erythrasma is mistaken for acanthosis nigricans, the patient may be counseled inappropriately that the hyperpigmentation is something not easily resolved and subsequently left with an active treatable condition that adversely affects their quality of life.

1. Groves JB, Nassereddin A, Freeman AM. Erythrasma. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; August 11, 2021. Accessed November 17, 2022. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK513352/

2. Forouzan P, Cohen PR. Erythrasma revisited: diagnosis, differential diagnoses, and comprehensive review of treatment. Cureus. 2020;12:E10733. doi:10.7759/cureus.10733

3. Polat M, I˙lhan MN. Dermatological complaints of the elderly attending a dermatology outpatient clinic in Turkey: a prospective study over a one-year period. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat. 2015;23:277-281.

4. Janeczek M, Kozel Z, Bhasin R, et al. High prevalence of erythrasma in patients with inverse psoriasis: a cross-sectional study. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2020;13:12-14.

5. Khan MJ. Interdigital pedal erythrasma treated with one-time dose of oral clarithromycin 1 g: two case reports. Clin Case Rep. 2020;8:672-674. doi:10.1002/ccr3.2712

6. Stierman B, Afful J, Carroll M, et al. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2017–March 2020 Prepandemic Data Files Development of Files and Prevalence Estimates for Selected Health Outcomes. National Health Statistics Reports. Published June 14, 2021. Accessed November 17, 2022. https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/106273

7. Brady MF, Rawla P. Acanthosis nigricans. In: StatPearls. Stat- Pearls Publishing; 2022. Updated October 9, 2022. Accessed November 30, 2022. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK431057

1. Groves JB, Nassereddin A, Freeman AM. Erythrasma. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; August 11, 2021. Accessed November 17, 2022. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK513352/

2. Forouzan P, Cohen PR. Erythrasma revisited: diagnosis, differential diagnoses, and comprehensive review of treatment. Cureus. 2020;12:E10733. doi:10.7759/cureus.10733

3. Polat M, I˙lhan MN. Dermatological complaints of the elderly attending a dermatology outpatient clinic in Turkey: a prospective study over a one-year period. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat. 2015;23:277-281.

4. Janeczek M, Kozel Z, Bhasin R, et al. High prevalence of erythrasma in patients with inverse psoriasis: a cross-sectional study. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2020;13:12-14.

5. Khan MJ. Interdigital pedal erythrasma treated with one-time dose of oral clarithromycin 1 g: two case reports. Clin Case Rep. 2020;8:672-674. doi:10.1002/ccr3.2712

6. Stierman B, Afful J, Carroll M, et al. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2017–March 2020 Prepandemic Data Files Development of Files and Prevalence Estimates for Selected Health Outcomes. National Health Statistics Reports. Published June 14, 2021. Accessed November 17, 2022. https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/106273

7. Brady MF, Rawla P. Acanthosis nigricans. In: StatPearls. Stat- Pearls Publishing; 2022. Updated October 9, 2022. Accessed November 30, 2022. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK431057