User login

When worry is excessive: Easing the burden of GAD

THE CASE

Sandra H,* a 24-year-old single woman with a history of asthma, presented to our family medicine clinic as a new patient. Ms. H said she lived at home with her mother. She completed high school but never attended college due to anxiety. She had held several jobs since high school and recently decided to apply to a local college, which prompted a desire to gain control over the anxiety that had been present since middle school. She reported feeling anxious, having difficulty breathing, shaking all over, having difficulty concentrating, and experiencing numbness and tingling in her fingers. She was often irritable at home, which she attributed partly to anxiety but mostly to disrupted sleep. We administered the 7-question Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD-7) questionnaire and she scored 15 (of a possible 21) points, indicative of severe anxiety.

●

* The patient’s name has been changed to protect her identity.

Approximately 1 in 5 patients presenting to primary care clinics have at least 1 anxiety disorder and 7.6% have generalized anxiety disorder (GAD).1 Yet many go untreated. The lifetime prevalence of GAD is 3.7% worldwide and 7.8% in the United States.2 Only 5% of cases emerge by age 13,2 but incidence increases through adolescence and young adulthood, with a quarter of all cases occurring by age 25.2 GAD occurs about twice as often in women as it does in men. It is typically recurrent, and many patients require ongoing treatment.2

GAD diagnostic criteria and differential considerations

Diagnosis of GAD requires at least 6 months of excessive worry or anxiety about a variety of circumstances, occurring on most days and for more than half the day.3 The worry or anxiety in GAD is difficult to control, disrupts meaningful areas of life, and surrounds everyday concerns, such as finances, health, or family-related issues. Among adolescents with GAD, worries typically include school performance and may often present as perfectionism.4 At least 3 of the following 6 symptoms result from chronic anxiety: restlessness, fatigue, poor concentration, irritability, muscle tension, and sleep disturbance.2

Rule out other conditions. Make sure symptoms of GAD are not better explained by another medical problem, including other mental disorders or substance use disorders.3 Complaints of anxiety in the context of mania, hypomania, or withdrawal from alcohol or a sedative hypnotic suggest a different underlying cause, thereby requiring a complete history with symptom chronology and collateral information. The pattern of anxiety seen in GAD also differs from the focused sources of anxiety found in disorders such as social anxiety disorder (SAD) and post-traumatic stress disorder. For example, SAD might center on embarrassment in a social setting rather than reflect a pattern of general worry.5

Consider comorbidities. Further complicating diagnosis and treatment, GAD has been linked to higher rates of comorbidity and higher health care utilization. About 90% of GAD patients experience psychiatric comorbidity, with major depressive disorder co-occurring about 60% of the time.6 Substance use disorders co-occur with GAD more than 20% of the time.2 Despite comorbidities, it is the somatic complaints in GAD that often drive patient requests for medical care.7,8 GAD itself is an independent predictor of heart disease9 and is linked to increased risk of chronic or severe headaches10 and suicide.11,12

Continue to: Work with patients and family toward a diagnosis

Work with patients and family toward a diagnosis

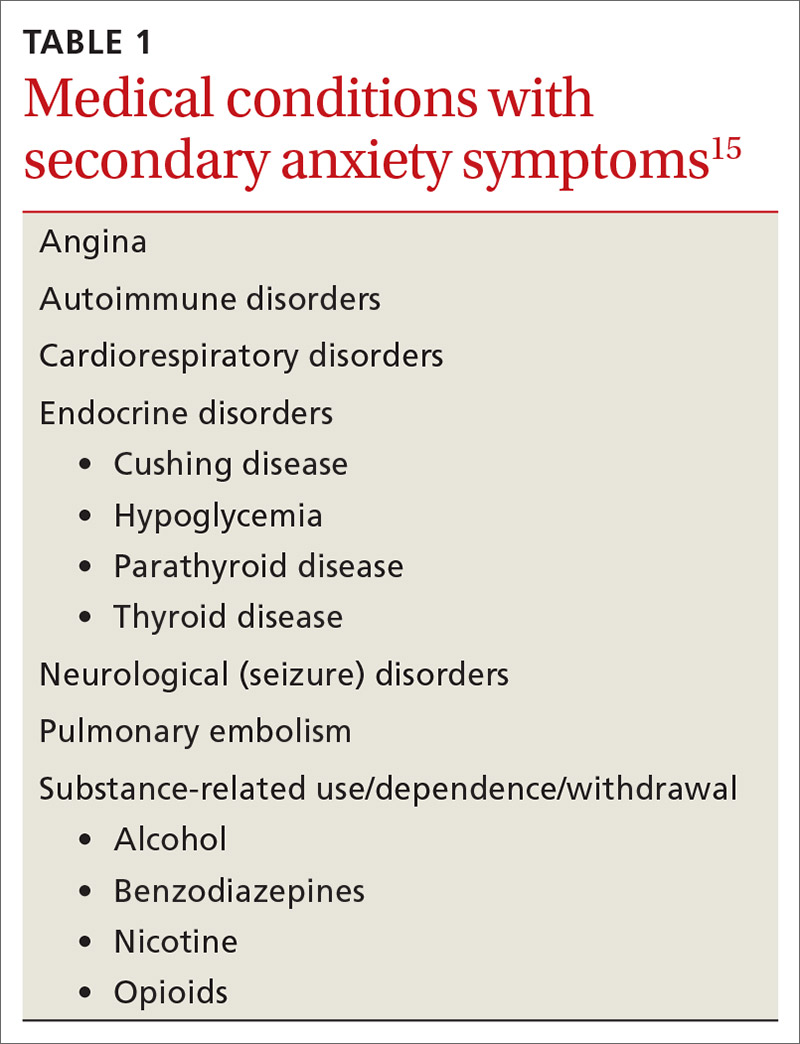

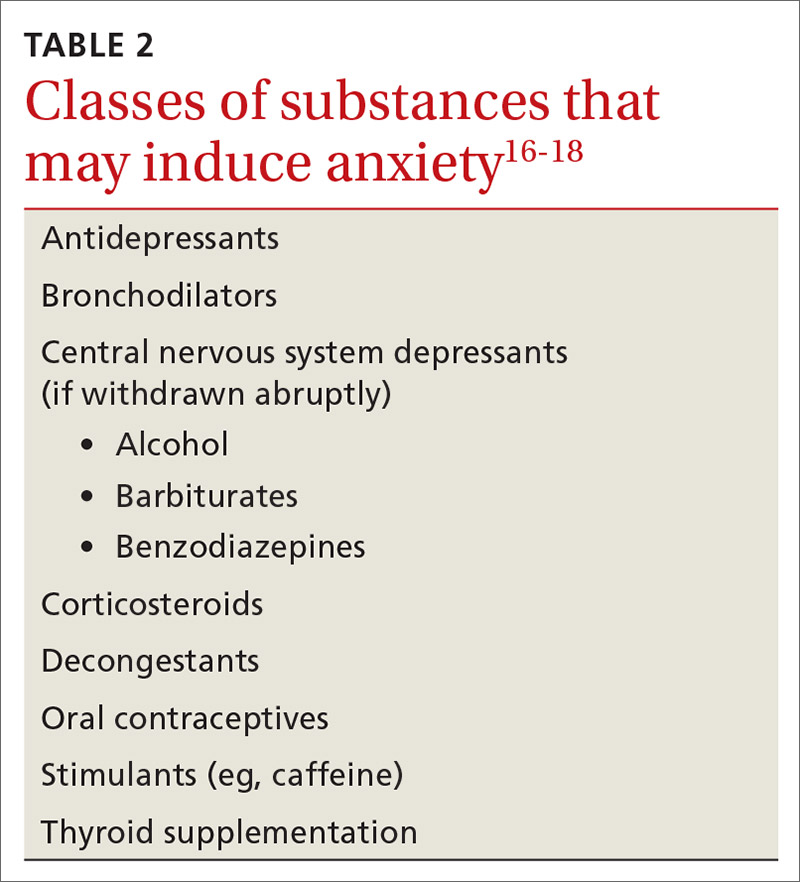

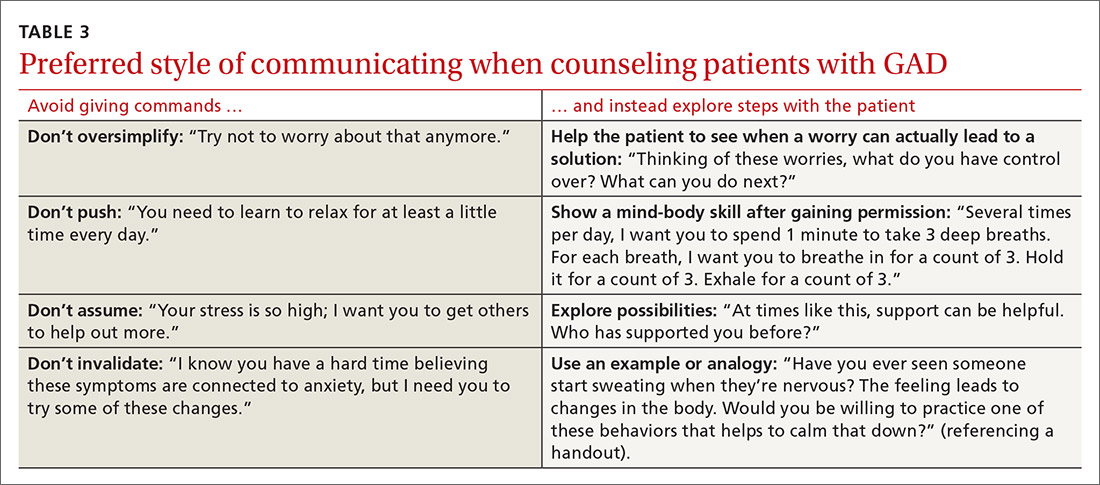

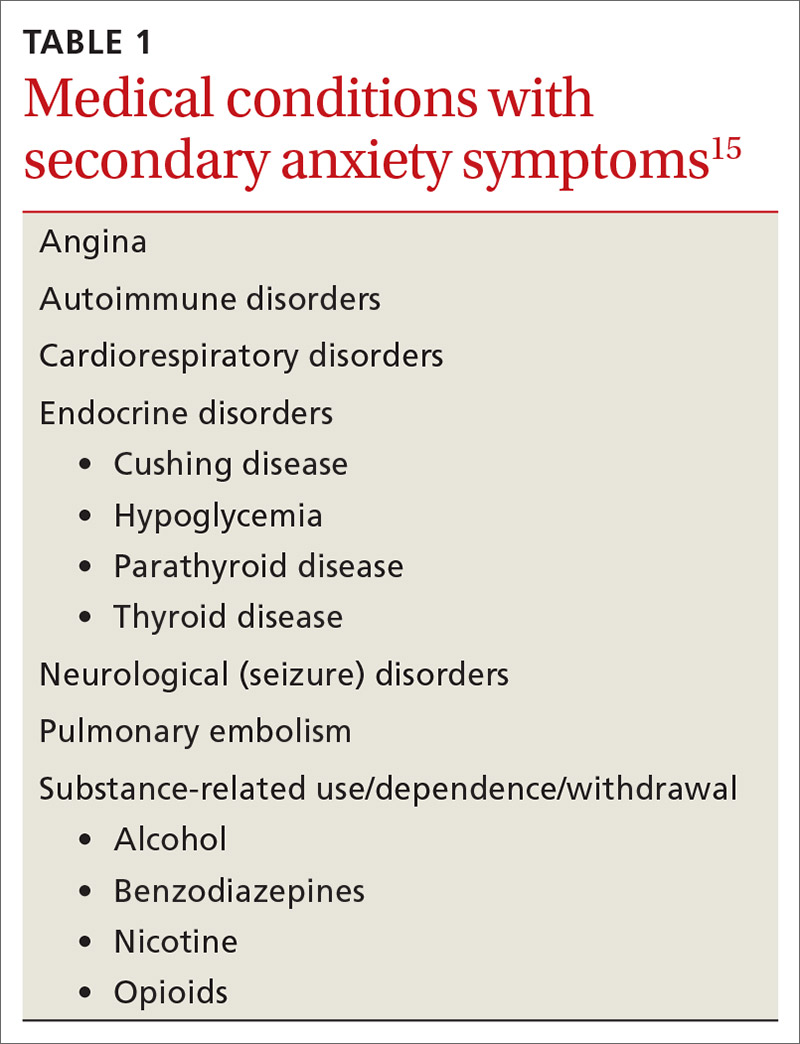

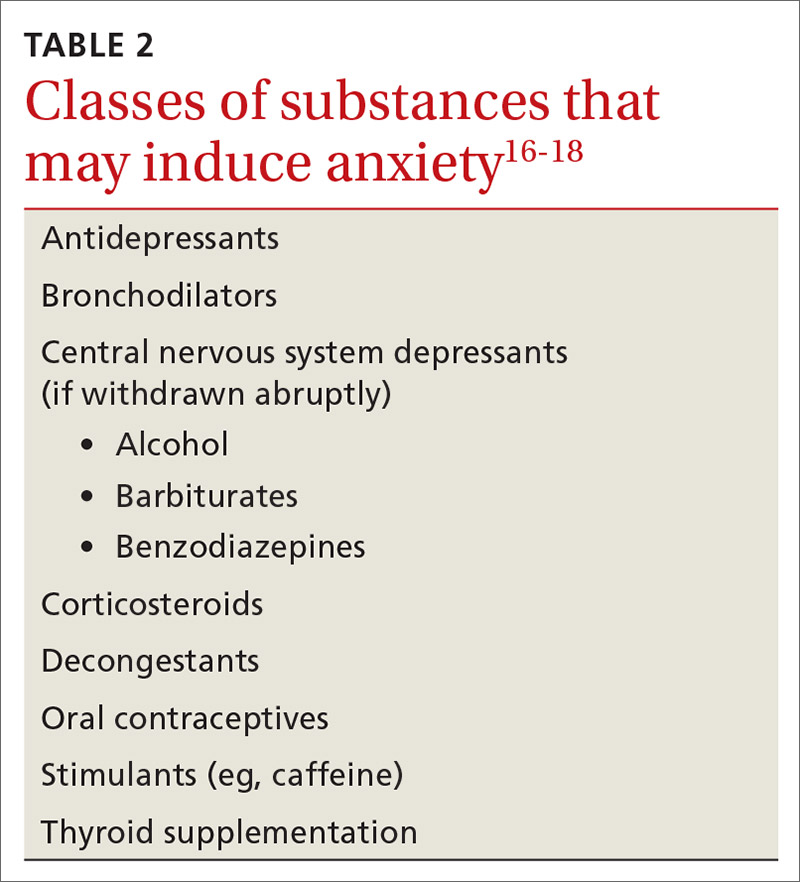

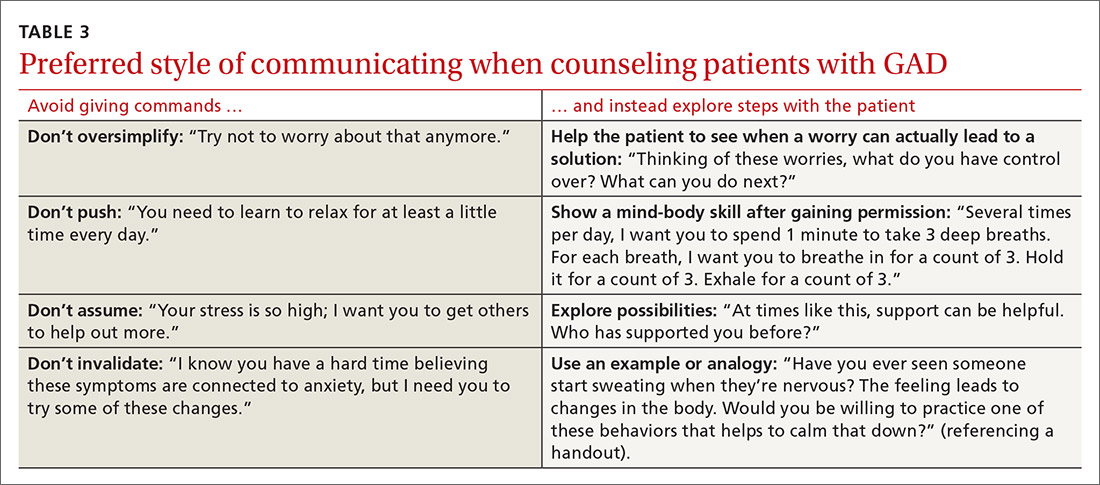

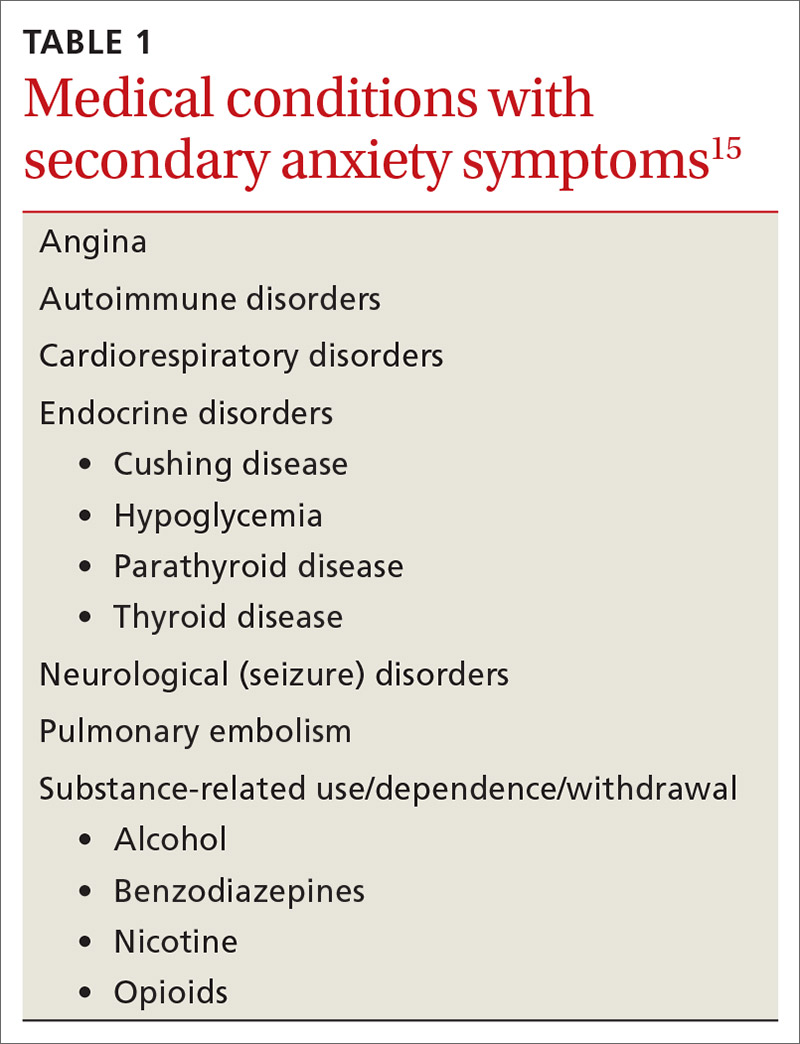

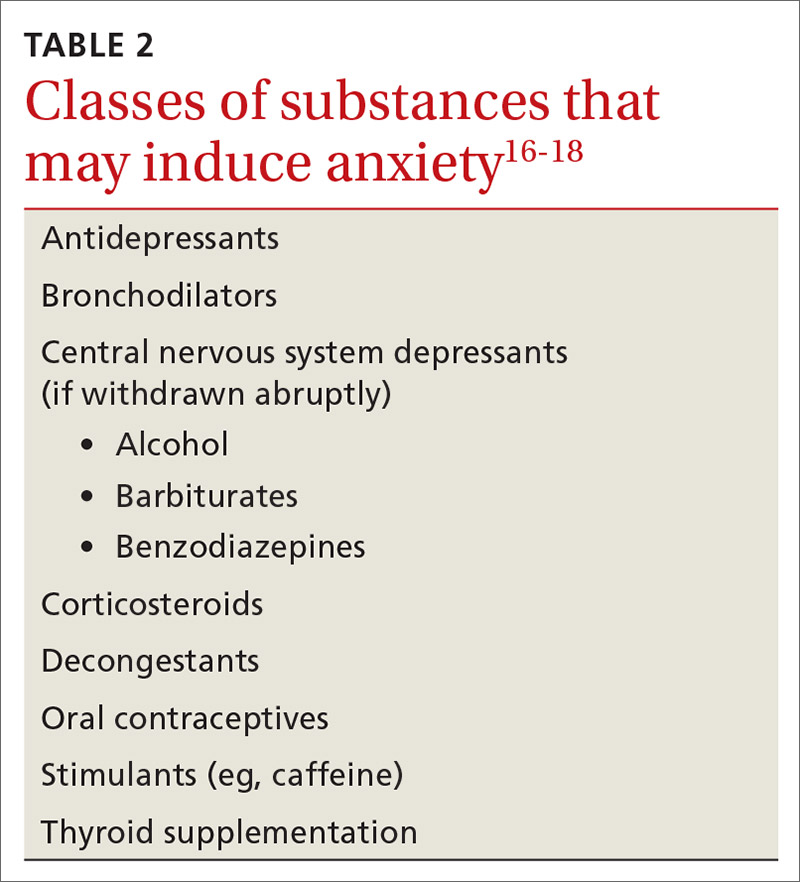

Despite the potential benefits of early identification and treatment of GAD,13 the average elapsed time from symptom onset to initial medication treatment is 7 years.14 Multiple factors likely account for this delay. Clinical presentations can be highly variable,6 with 1 patient presenting primarily with sleep complaints and another with gastrointestinal symptoms. Some medical conditions (TABLE 1)15 and substances (TABLE 2)16-18 can cause secondary anxiety symptoms, and their presence should prompt a thorough evaluation.

Address the mind-body connection. Because uncertainty and ambiguity surrounding a diagnosis often drive worry,19 anxious patients or their family members commonly seek additional medical visits and tests in search of answers. In such instances, it helps to explain the physiologic connection between somatic complaints and anxiety.8 Describe how areas of the brain that manage fear and stress can also cause muscle tension, gastrointestinal complaints, hyperarousal, or sleep disturbance.

Empathy and early psychoeducation on the reason anxiety is being considered can decrease stigma and enable appropriate follow-up and treatment. You might introduce the connection between health complaints and GAD specifically by exploring the amount of worry surrounding the presenting symptoms, followed by a question such as, “Sometimes your worry will fit the situation and sometimes it’ll be too much. Has anyone ever told you that you worry too much?” The patient’s response to such a question could signal a need to use the GAD-7 screening tool1 as an aid to diagnosis and as a baseline measure for monitoring subsequent treatment progress.

Psycho- and pharmacotherapy aspects of management

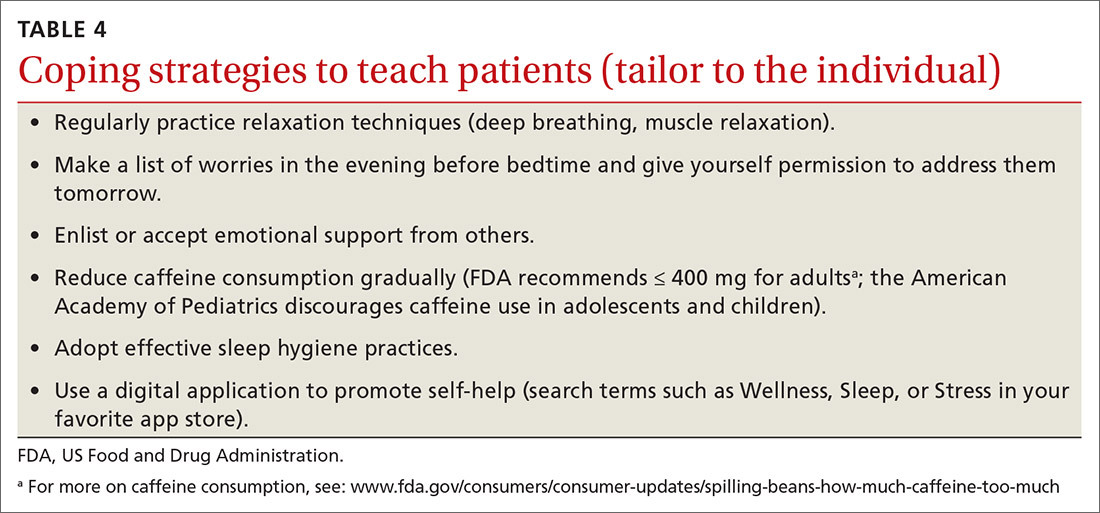

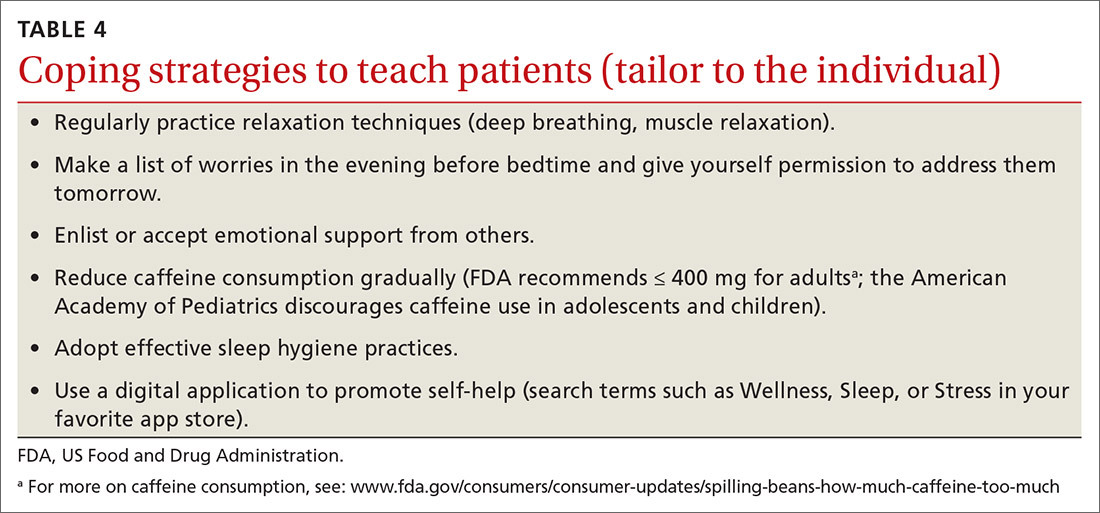

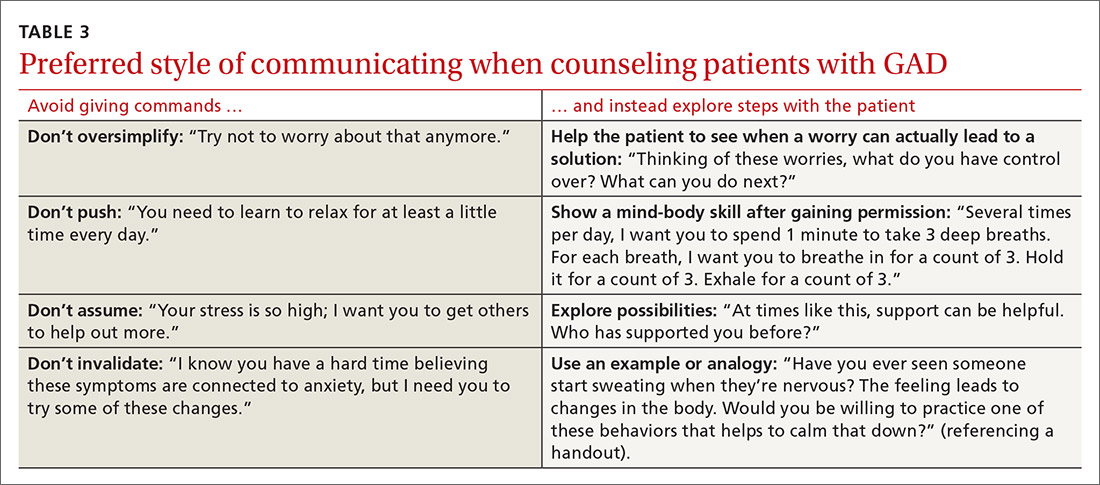

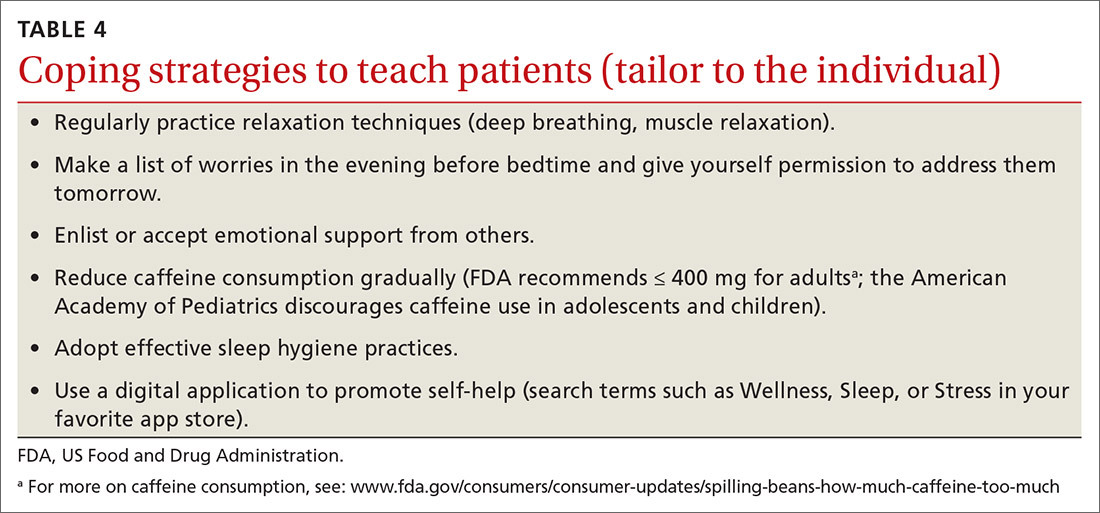

Let patients choose from among various coping strategies. Be prepared to offer patients user-friendly handouts, reading material, or links to educational Web sites. Many patients are interested in using smartphone applications to learn and practice coping strategies. Although these apps can encourage the regular practice of coping skills, caution teens and parents about privacy issues and the lack of evidence supporting this approach as stand-alone therapy.21 Offering several choices (TABLE 4)

Continue to: For patients who remain focused...

For patients who remain focused on somatic complaints and resist adopting coping skills or treatment, pushing certain recommendations can actually increase resistance to proper treatment.22 Instead, explore their ambivalence, offer facts, express concern about the current course of the illness, and emphasize the need to revisit the discussion at a future appointment. Offer follow-up monitoring to assess the course of the illness and readiness for GAD treatment.

Initiate treatment in a stepwise manner13 for the patient who is ready for GAD treatment. This approach includes education and monitoring; low-intensity interventions (eg, treatment workbooks or group sessions); medication and/or referral for psychotherapy; referral for outpatient psychiatric care; and hospitalization for patients who pose a danger to self or others.13 Studies suggest that patients receiving both psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy benefit from the complementary targeting of symptoms, exhibit increased adherence, and report fewer adverse effects.23

Patients are most likely to benefit from therapy when they have the capacity for introspection and forming friendships (ie, can form a therapeutic alliance). With such patients who have mild or moderate symptoms of GAD, offer cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) or applied relaxation training. Consider a trial of medication when symptoms are severe, when psychotherapy is not a good option, or when response to psychotherapy is inadequate.13 Medications work by targeting primitive parts of the brain such as the amygdala (bottom up), while psychotherapy targets the cortex or more evolved part of the brain, teaching it to modulate the lower or more primitive structures (top down).24

Medication considerations. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are considered first-line pharmacotherapy for adult and adolescent patients with GAD.20 However, in adolescents, no SSRIs are approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to treat anxiety disorders unassociated with obsessive-compulsive disorder. Use caution if prescribing an SSRI for off-label treatment in an adolescent; talk with the patient and family about the FDA’s black-box warning regarding the potential for suicidality in adolescents.

For adults, selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) are also considered a first-line treatment option.23 SSRIs and SNRIs are well-studied, effective, safe, and better tolerated than earlier antidepressants. However, be aware that both SSRIs and SNRIs are often associated with headache, nausea, and sexual dysfunction. They are dosed once daily and have not been shown to cause dependence. Inform patients that onset of action is often delayed 4 to 8 weeks23 and that there is a risk for anxiety-producing effects early in treatment. To minimize these effects, consider starting treatment at a lower dose and titrate upward more gradually than when treating depression.

Continue to: Continue treatment for 12 months...

Continue treatment for 12 months to reduce the risk of recurrence.23 If response to treatment is insufficient after 2 adequate trials of an SSRI or SNRI, consider second-line agents such as azapirones or benzodiazepines for adults, keeping in mind the risk for dependence with benzodiazepines.13

Evidence supports GABAergic drugs such as gabapentin and pregabalin as off-label treatments for GAD in refractory adult cases.25 In the European Union, pregabalin is approved for use in GAD. Caution is recommended with both drugs due to abuse potential. Next steps for an inadequate response should include referral to Psychiatry or for inpatient care when risk of harm to self or others is high.

CASE

Considering Ms. H’s ability to work and complete daily activities, we talked to her about CBT as a first step and referred her to a therapist in the community. One month after her initial visit with us, Ms. H returned for a follow-up visit and scored a 17 on her GAD-7, still in the severe range. After one CBT session, she had cancelled her second and third appointments due to work conflicts. She had missed some work from oversleeping after worried sleepless nights. Her worries concerned friendships, paying bills, physical appearance, not being able to exercise and therefore gaining weight, and troubles at work and with her mother. She also described several episodes of nightmares after breaking up with a boyfriend.

She agreed to try an SSRI, and we started her on fluoxetine 10 mg/d. We counseled her on SSRI risks and benefits, including the potential for increased suicidal ideation and how to respond if such thoughts developed. Three weeks after starting fluoxetine, Ms. H reported improvement with no adverse effects from the medication, except for decreased appetite and some weight loss, which she welcomed. She had registered for college courses, and her third score on the GAD-7 was an 8.

We increased her fluoxetine dose to 20 mg/d for maintenance. We encouraged her to return to her therapist for CBT and she scheduled that appointment. Therapy records noted a GAD-7 score of 5 at follow-up 8 weeks later. Ms. H reported improved sleep, reduced irritability at home, and better relationships with her mother and friends. She had begun college classes and was writing about her thoughts and worries as part of her CBT homework. She continued follow-up appointments with both her family physician and her therapist.

CORRESPONDENCE

Christopher A. Ebberwein, PhD, Wesley Family Medicine Residency, 850 North Hillside, Wichita, KS 67214; chris. ebberwein@wesleymc.com.

1. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, et al. Anxiety disorders in primary care: prevalence, impairment, comorbidity, and detection. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146:317-325.

2. Ruscio AM, Hallion LS, Lim CCW, et al. Cross-sectional comparison of the epidemiology of DSM-5 generalized anxiety disorder across the globe. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74:465-475.

3. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition (DSM-5). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013.

4. Fernandez S. Anxiety disorders in childhood and adolescence: a primary care approach. Pediatr Ann. 2017;46:e213-e216.

5. Connolly SD, Bernstein GA. Practice parameter for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with anxiety disorders. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2007;46:267-283.

6. Reinhold JA, Rickels K. Pharmacological treatments for generalized anxiety disorder in adults: an update. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2015;16:1669-1681.

7. Kujanpää TS, Jokelainen J, Auvinen JP, et al. The association of generalized anxiety disorder and somatic symptoms with frequent attendance to healthcare services: a cross-sectional study from the Northern Finland Birth Cohort 1966. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2017:52:147-159.

8. Ramsawh HJ, Chavira DA, Stein MB. Burden of anxiety disorders in pediatric medical settings: prevalence, phenomenology, and a research agenda. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2010;164:965-972. doi:10.1001/archpediatrics.2010.170.

9. Barger SD, Sydeman SJ. Does generalized anxiety disorder predict coronary heart disease risk factors independently of major depressive disorder? J Affect Disord. 2005;88:87-91.

10. Bruffaerts R, Demyttenaere K, Kessler RC, et al. The associations between preexisting mental disorders and subsequent onset of chronic headaches: a worldwide epidemiologic perspective. J Pain. 2015;16:42-52.

11. Husky MM, Olfson M, He J, et al. Twelve-month suicidal symptoms and use of services among adolescents: results from the National Comorbidity Survey. Psychiatr Serv. 2012;63:989-996.

12. Nepon J, Belik S, Bolton J, et al. The relationship between anxiety disorders and suicide attempts: findings from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Depress Anxiety. 2010;27:791–798.

13. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Generalised anxiety disorder and panic disorder adults: management. nice.org.uk/guidance/cg113. Accessed August 20, 2020.

14. Dell’Osso B, Camuri G, Benatti B, et al. Differences in latency to first pharmacological treatment (duration of untreated illness) in anxiety disorders: a study on patients with panic disorder, generalized anxiety disorder and obsessive-compulsive disorder. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2013;7:374-380.

15. Hales RE, Yudofsky SC, Roberts LW, eds. Textbook of Psychiatry, 6th ed. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing: 2014:391-430.

16. Fernandez F, Levy JK, Lachar BL, et al. The management of depression and anxiety in the elderly. J Clin Psychiatry. 1995;56(suppl 2):20-29.

17. Kirkwood CK, Hayes PE. Anxiety disorders. In: DiPiro JT, Talbert RL, Yee GC, et al, eds. Pharmacotherapy: A Pathophysiologic Approach, 3rd ed. Stamford, Conn: Appleton & Lange;1997:1443-1462.

18. Culpepper L. Generalized anxiety disorder and medical illness. J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;70(suppl 2):20-24.

19. Anderson KG, Dugas MJ, Koerner N, et al. Interpretive style and intolerance of uncertainty in individuals with anxiety disorders: a focus on generalized anxiety disorder. J Anxiety Disord. 2012;26:823-832.

20. Satterfield JM, Feldman MD. Anxiety. In Feldman MD, Christensen JF, Satterfield JM, eds. Behavioral Medicine: A Guide for Clinical Practice. New York: McGraw Hill; 2014:271-282.

21. Grist R, Porter J, Stallard P. Mental health mobile apps for preadolescents and adolescents: A systematic review. J Med Internet Res. 2017;19:e176.

22. Rollnick S, Miller W, Butler C. Motivational Interviewing in Health Care: Helping Patients Change Behavior. 1st ed. New York: The Guilford Press; 2008:34-35.

23. Strawn JR, Geriacioti L, Rajdev N, et al. Pharmacotherapy for generalized anxiety disorder in adult and pediatric patients: an evidence-based review. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2018;19:1057-1070.

24. Ehmke CJ, Nemeroff CB. Paroxetine. In Schatzberg AF, Nemeroff CB, eds. Textbook of Psychopharmacology, 4th ed. Washington, D.C.: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc.; 2009:321-352.

25. Huh J, Goebert D, Takeshita J, et al. Treatment of generalized anxiety disorder: a comprehensive review of the literature for psychopharmacologic alternatives to newer antidepressants and benzodiazepines. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2011;13: doi:10.4088/PCC.08r00709blu.

THE CASE

Sandra H,* a 24-year-old single woman with a history of asthma, presented to our family medicine clinic as a new patient. Ms. H said she lived at home with her mother. She completed high school but never attended college due to anxiety. She had held several jobs since high school and recently decided to apply to a local college, which prompted a desire to gain control over the anxiety that had been present since middle school. She reported feeling anxious, having difficulty breathing, shaking all over, having difficulty concentrating, and experiencing numbness and tingling in her fingers. She was often irritable at home, which she attributed partly to anxiety but mostly to disrupted sleep. We administered the 7-question Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD-7) questionnaire and she scored 15 (of a possible 21) points, indicative of severe anxiety.

●

* The patient’s name has been changed to protect her identity.

Approximately 1 in 5 patients presenting to primary care clinics have at least 1 anxiety disorder and 7.6% have generalized anxiety disorder (GAD).1 Yet many go untreated. The lifetime prevalence of GAD is 3.7% worldwide and 7.8% in the United States.2 Only 5% of cases emerge by age 13,2 but incidence increases through adolescence and young adulthood, with a quarter of all cases occurring by age 25.2 GAD occurs about twice as often in women as it does in men. It is typically recurrent, and many patients require ongoing treatment.2

GAD diagnostic criteria and differential considerations

Diagnosis of GAD requires at least 6 months of excessive worry or anxiety about a variety of circumstances, occurring on most days and for more than half the day.3 The worry or anxiety in GAD is difficult to control, disrupts meaningful areas of life, and surrounds everyday concerns, such as finances, health, or family-related issues. Among adolescents with GAD, worries typically include school performance and may often present as perfectionism.4 At least 3 of the following 6 symptoms result from chronic anxiety: restlessness, fatigue, poor concentration, irritability, muscle tension, and sleep disturbance.2

Rule out other conditions. Make sure symptoms of GAD are not better explained by another medical problem, including other mental disorders or substance use disorders.3 Complaints of anxiety in the context of mania, hypomania, or withdrawal from alcohol or a sedative hypnotic suggest a different underlying cause, thereby requiring a complete history with symptom chronology and collateral information. The pattern of anxiety seen in GAD also differs from the focused sources of anxiety found in disorders such as social anxiety disorder (SAD) and post-traumatic stress disorder. For example, SAD might center on embarrassment in a social setting rather than reflect a pattern of general worry.5

Consider comorbidities. Further complicating diagnosis and treatment, GAD has been linked to higher rates of comorbidity and higher health care utilization. About 90% of GAD patients experience psychiatric comorbidity, with major depressive disorder co-occurring about 60% of the time.6 Substance use disorders co-occur with GAD more than 20% of the time.2 Despite comorbidities, it is the somatic complaints in GAD that often drive patient requests for medical care.7,8 GAD itself is an independent predictor of heart disease9 and is linked to increased risk of chronic or severe headaches10 and suicide.11,12

Continue to: Work with patients and family toward a diagnosis

Work with patients and family toward a diagnosis

Despite the potential benefits of early identification and treatment of GAD,13 the average elapsed time from symptom onset to initial medication treatment is 7 years.14 Multiple factors likely account for this delay. Clinical presentations can be highly variable,6 with 1 patient presenting primarily with sleep complaints and another with gastrointestinal symptoms. Some medical conditions (TABLE 1)15 and substances (TABLE 2)16-18 can cause secondary anxiety symptoms, and their presence should prompt a thorough evaluation.

Address the mind-body connection. Because uncertainty and ambiguity surrounding a diagnosis often drive worry,19 anxious patients or their family members commonly seek additional medical visits and tests in search of answers. In such instances, it helps to explain the physiologic connection between somatic complaints and anxiety.8 Describe how areas of the brain that manage fear and stress can also cause muscle tension, gastrointestinal complaints, hyperarousal, or sleep disturbance.

Empathy and early psychoeducation on the reason anxiety is being considered can decrease stigma and enable appropriate follow-up and treatment. You might introduce the connection between health complaints and GAD specifically by exploring the amount of worry surrounding the presenting symptoms, followed by a question such as, “Sometimes your worry will fit the situation and sometimes it’ll be too much. Has anyone ever told you that you worry too much?” The patient’s response to such a question could signal a need to use the GAD-7 screening tool1 as an aid to diagnosis and as a baseline measure for monitoring subsequent treatment progress.

Psycho- and pharmacotherapy aspects of management

Let patients choose from among various coping strategies. Be prepared to offer patients user-friendly handouts, reading material, or links to educational Web sites. Many patients are interested in using smartphone applications to learn and practice coping strategies. Although these apps can encourage the regular practice of coping skills, caution teens and parents about privacy issues and the lack of evidence supporting this approach as stand-alone therapy.21 Offering several choices (TABLE 4)

Continue to: For patients who remain focused...

For patients who remain focused on somatic complaints and resist adopting coping skills or treatment, pushing certain recommendations can actually increase resistance to proper treatment.22 Instead, explore their ambivalence, offer facts, express concern about the current course of the illness, and emphasize the need to revisit the discussion at a future appointment. Offer follow-up monitoring to assess the course of the illness and readiness for GAD treatment.

Initiate treatment in a stepwise manner13 for the patient who is ready for GAD treatment. This approach includes education and monitoring; low-intensity interventions (eg, treatment workbooks or group sessions); medication and/or referral for psychotherapy; referral for outpatient psychiatric care; and hospitalization for patients who pose a danger to self or others.13 Studies suggest that patients receiving both psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy benefit from the complementary targeting of symptoms, exhibit increased adherence, and report fewer adverse effects.23

Patients are most likely to benefit from therapy when they have the capacity for introspection and forming friendships (ie, can form a therapeutic alliance). With such patients who have mild or moderate symptoms of GAD, offer cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) or applied relaxation training. Consider a trial of medication when symptoms are severe, when psychotherapy is not a good option, or when response to psychotherapy is inadequate.13 Medications work by targeting primitive parts of the brain such as the amygdala (bottom up), while psychotherapy targets the cortex or more evolved part of the brain, teaching it to modulate the lower or more primitive structures (top down).24

Medication considerations. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are considered first-line pharmacotherapy for adult and adolescent patients with GAD.20 However, in adolescents, no SSRIs are approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to treat anxiety disorders unassociated with obsessive-compulsive disorder. Use caution if prescribing an SSRI for off-label treatment in an adolescent; talk with the patient and family about the FDA’s black-box warning regarding the potential for suicidality in adolescents.

For adults, selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) are also considered a first-line treatment option.23 SSRIs and SNRIs are well-studied, effective, safe, and better tolerated than earlier antidepressants. However, be aware that both SSRIs and SNRIs are often associated with headache, nausea, and sexual dysfunction. They are dosed once daily and have not been shown to cause dependence. Inform patients that onset of action is often delayed 4 to 8 weeks23 and that there is a risk for anxiety-producing effects early in treatment. To minimize these effects, consider starting treatment at a lower dose and titrate upward more gradually than when treating depression.

Continue to: Continue treatment for 12 months...

Continue treatment for 12 months to reduce the risk of recurrence.23 If response to treatment is insufficient after 2 adequate trials of an SSRI or SNRI, consider second-line agents such as azapirones or benzodiazepines for adults, keeping in mind the risk for dependence with benzodiazepines.13

Evidence supports GABAergic drugs such as gabapentin and pregabalin as off-label treatments for GAD in refractory adult cases.25 In the European Union, pregabalin is approved for use in GAD. Caution is recommended with both drugs due to abuse potential. Next steps for an inadequate response should include referral to Psychiatry or for inpatient care when risk of harm to self or others is high.

CASE

Considering Ms. H’s ability to work and complete daily activities, we talked to her about CBT as a first step and referred her to a therapist in the community. One month after her initial visit with us, Ms. H returned for a follow-up visit and scored a 17 on her GAD-7, still in the severe range. After one CBT session, she had cancelled her second and third appointments due to work conflicts. She had missed some work from oversleeping after worried sleepless nights. Her worries concerned friendships, paying bills, physical appearance, not being able to exercise and therefore gaining weight, and troubles at work and with her mother. She also described several episodes of nightmares after breaking up with a boyfriend.

She agreed to try an SSRI, and we started her on fluoxetine 10 mg/d. We counseled her on SSRI risks and benefits, including the potential for increased suicidal ideation and how to respond if such thoughts developed. Three weeks after starting fluoxetine, Ms. H reported improvement with no adverse effects from the medication, except for decreased appetite and some weight loss, which she welcomed. She had registered for college courses, and her third score on the GAD-7 was an 8.

We increased her fluoxetine dose to 20 mg/d for maintenance. We encouraged her to return to her therapist for CBT and she scheduled that appointment. Therapy records noted a GAD-7 score of 5 at follow-up 8 weeks later. Ms. H reported improved sleep, reduced irritability at home, and better relationships with her mother and friends. She had begun college classes and was writing about her thoughts and worries as part of her CBT homework. She continued follow-up appointments with both her family physician and her therapist.

CORRESPONDENCE

Christopher A. Ebberwein, PhD, Wesley Family Medicine Residency, 850 North Hillside, Wichita, KS 67214; chris. ebberwein@wesleymc.com.

THE CASE

Sandra H,* a 24-year-old single woman with a history of asthma, presented to our family medicine clinic as a new patient. Ms. H said she lived at home with her mother. She completed high school but never attended college due to anxiety. She had held several jobs since high school and recently decided to apply to a local college, which prompted a desire to gain control over the anxiety that had been present since middle school. She reported feeling anxious, having difficulty breathing, shaking all over, having difficulty concentrating, and experiencing numbness and tingling in her fingers. She was often irritable at home, which she attributed partly to anxiety but mostly to disrupted sleep. We administered the 7-question Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD-7) questionnaire and she scored 15 (of a possible 21) points, indicative of severe anxiety.

●

* The patient’s name has been changed to protect her identity.

Approximately 1 in 5 patients presenting to primary care clinics have at least 1 anxiety disorder and 7.6% have generalized anxiety disorder (GAD).1 Yet many go untreated. The lifetime prevalence of GAD is 3.7% worldwide and 7.8% in the United States.2 Only 5% of cases emerge by age 13,2 but incidence increases through adolescence and young adulthood, with a quarter of all cases occurring by age 25.2 GAD occurs about twice as often in women as it does in men. It is typically recurrent, and many patients require ongoing treatment.2

GAD diagnostic criteria and differential considerations

Diagnosis of GAD requires at least 6 months of excessive worry or anxiety about a variety of circumstances, occurring on most days and for more than half the day.3 The worry or anxiety in GAD is difficult to control, disrupts meaningful areas of life, and surrounds everyday concerns, such as finances, health, or family-related issues. Among adolescents with GAD, worries typically include school performance and may often present as perfectionism.4 At least 3 of the following 6 symptoms result from chronic anxiety: restlessness, fatigue, poor concentration, irritability, muscle tension, and sleep disturbance.2

Rule out other conditions. Make sure symptoms of GAD are not better explained by another medical problem, including other mental disorders or substance use disorders.3 Complaints of anxiety in the context of mania, hypomania, or withdrawal from alcohol or a sedative hypnotic suggest a different underlying cause, thereby requiring a complete history with symptom chronology and collateral information. The pattern of anxiety seen in GAD also differs from the focused sources of anxiety found in disorders such as social anxiety disorder (SAD) and post-traumatic stress disorder. For example, SAD might center on embarrassment in a social setting rather than reflect a pattern of general worry.5

Consider comorbidities. Further complicating diagnosis and treatment, GAD has been linked to higher rates of comorbidity and higher health care utilization. About 90% of GAD patients experience psychiatric comorbidity, with major depressive disorder co-occurring about 60% of the time.6 Substance use disorders co-occur with GAD more than 20% of the time.2 Despite comorbidities, it is the somatic complaints in GAD that often drive patient requests for medical care.7,8 GAD itself is an independent predictor of heart disease9 and is linked to increased risk of chronic or severe headaches10 and suicide.11,12

Continue to: Work with patients and family toward a diagnosis

Work with patients and family toward a diagnosis

Despite the potential benefits of early identification and treatment of GAD,13 the average elapsed time from symptom onset to initial medication treatment is 7 years.14 Multiple factors likely account for this delay. Clinical presentations can be highly variable,6 with 1 patient presenting primarily with sleep complaints and another with gastrointestinal symptoms. Some medical conditions (TABLE 1)15 and substances (TABLE 2)16-18 can cause secondary anxiety symptoms, and their presence should prompt a thorough evaluation.

Address the mind-body connection. Because uncertainty and ambiguity surrounding a diagnosis often drive worry,19 anxious patients or their family members commonly seek additional medical visits and tests in search of answers. In such instances, it helps to explain the physiologic connection between somatic complaints and anxiety.8 Describe how areas of the brain that manage fear and stress can also cause muscle tension, gastrointestinal complaints, hyperarousal, or sleep disturbance.

Empathy and early psychoeducation on the reason anxiety is being considered can decrease stigma and enable appropriate follow-up and treatment. You might introduce the connection between health complaints and GAD specifically by exploring the amount of worry surrounding the presenting symptoms, followed by a question such as, “Sometimes your worry will fit the situation and sometimes it’ll be too much. Has anyone ever told you that you worry too much?” The patient’s response to such a question could signal a need to use the GAD-7 screening tool1 as an aid to diagnosis and as a baseline measure for monitoring subsequent treatment progress.

Psycho- and pharmacotherapy aspects of management

Let patients choose from among various coping strategies. Be prepared to offer patients user-friendly handouts, reading material, or links to educational Web sites. Many patients are interested in using smartphone applications to learn and practice coping strategies. Although these apps can encourage the regular practice of coping skills, caution teens and parents about privacy issues and the lack of evidence supporting this approach as stand-alone therapy.21 Offering several choices (TABLE 4)

Continue to: For patients who remain focused...

For patients who remain focused on somatic complaints and resist adopting coping skills or treatment, pushing certain recommendations can actually increase resistance to proper treatment.22 Instead, explore their ambivalence, offer facts, express concern about the current course of the illness, and emphasize the need to revisit the discussion at a future appointment. Offer follow-up monitoring to assess the course of the illness and readiness for GAD treatment.

Initiate treatment in a stepwise manner13 for the patient who is ready for GAD treatment. This approach includes education and monitoring; low-intensity interventions (eg, treatment workbooks or group sessions); medication and/or referral for psychotherapy; referral for outpatient psychiatric care; and hospitalization for patients who pose a danger to self or others.13 Studies suggest that patients receiving both psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy benefit from the complementary targeting of symptoms, exhibit increased adherence, and report fewer adverse effects.23

Patients are most likely to benefit from therapy when they have the capacity for introspection and forming friendships (ie, can form a therapeutic alliance). With such patients who have mild or moderate symptoms of GAD, offer cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) or applied relaxation training. Consider a trial of medication when symptoms are severe, when psychotherapy is not a good option, or when response to psychotherapy is inadequate.13 Medications work by targeting primitive parts of the brain such as the amygdala (bottom up), while psychotherapy targets the cortex or more evolved part of the brain, teaching it to modulate the lower or more primitive structures (top down).24

Medication considerations. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are considered first-line pharmacotherapy for adult and adolescent patients with GAD.20 However, in adolescents, no SSRIs are approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to treat anxiety disorders unassociated with obsessive-compulsive disorder. Use caution if prescribing an SSRI for off-label treatment in an adolescent; talk with the patient and family about the FDA’s black-box warning regarding the potential for suicidality in adolescents.

For adults, selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) are also considered a first-line treatment option.23 SSRIs and SNRIs are well-studied, effective, safe, and better tolerated than earlier antidepressants. However, be aware that both SSRIs and SNRIs are often associated with headache, nausea, and sexual dysfunction. They are dosed once daily and have not been shown to cause dependence. Inform patients that onset of action is often delayed 4 to 8 weeks23 and that there is a risk for anxiety-producing effects early in treatment. To minimize these effects, consider starting treatment at a lower dose and titrate upward more gradually than when treating depression.

Continue to: Continue treatment for 12 months...

Continue treatment for 12 months to reduce the risk of recurrence.23 If response to treatment is insufficient after 2 adequate trials of an SSRI or SNRI, consider second-line agents such as azapirones or benzodiazepines for adults, keeping in mind the risk for dependence with benzodiazepines.13

Evidence supports GABAergic drugs such as gabapentin and pregabalin as off-label treatments for GAD in refractory adult cases.25 In the European Union, pregabalin is approved for use in GAD. Caution is recommended with both drugs due to abuse potential. Next steps for an inadequate response should include referral to Psychiatry or for inpatient care when risk of harm to self or others is high.

CASE

Considering Ms. H’s ability to work and complete daily activities, we talked to her about CBT as a first step and referred her to a therapist in the community. One month after her initial visit with us, Ms. H returned for a follow-up visit and scored a 17 on her GAD-7, still in the severe range. After one CBT session, she had cancelled her second and third appointments due to work conflicts. She had missed some work from oversleeping after worried sleepless nights. Her worries concerned friendships, paying bills, physical appearance, not being able to exercise and therefore gaining weight, and troubles at work and with her mother. She also described several episodes of nightmares after breaking up with a boyfriend.

She agreed to try an SSRI, and we started her on fluoxetine 10 mg/d. We counseled her on SSRI risks and benefits, including the potential for increased suicidal ideation and how to respond if such thoughts developed. Three weeks after starting fluoxetine, Ms. H reported improvement with no adverse effects from the medication, except for decreased appetite and some weight loss, which she welcomed. She had registered for college courses, and her third score on the GAD-7 was an 8.

We increased her fluoxetine dose to 20 mg/d for maintenance. We encouraged her to return to her therapist for CBT and she scheduled that appointment. Therapy records noted a GAD-7 score of 5 at follow-up 8 weeks later. Ms. H reported improved sleep, reduced irritability at home, and better relationships with her mother and friends. She had begun college classes and was writing about her thoughts and worries as part of her CBT homework. She continued follow-up appointments with both her family physician and her therapist.

CORRESPONDENCE

Christopher A. Ebberwein, PhD, Wesley Family Medicine Residency, 850 North Hillside, Wichita, KS 67214; chris. ebberwein@wesleymc.com.

1. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, et al. Anxiety disorders in primary care: prevalence, impairment, comorbidity, and detection. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146:317-325.

2. Ruscio AM, Hallion LS, Lim CCW, et al. Cross-sectional comparison of the epidemiology of DSM-5 generalized anxiety disorder across the globe. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74:465-475.

3. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition (DSM-5). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013.

4. Fernandez S. Anxiety disorders in childhood and adolescence: a primary care approach. Pediatr Ann. 2017;46:e213-e216.

5. Connolly SD, Bernstein GA. Practice parameter for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with anxiety disorders. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2007;46:267-283.

6. Reinhold JA, Rickels K. Pharmacological treatments for generalized anxiety disorder in adults: an update. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2015;16:1669-1681.

7. Kujanpää TS, Jokelainen J, Auvinen JP, et al. The association of generalized anxiety disorder and somatic symptoms with frequent attendance to healthcare services: a cross-sectional study from the Northern Finland Birth Cohort 1966. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2017:52:147-159.

8. Ramsawh HJ, Chavira DA, Stein MB. Burden of anxiety disorders in pediatric medical settings: prevalence, phenomenology, and a research agenda. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2010;164:965-972. doi:10.1001/archpediatrics.2010.170.

9. Barger SD, Sydeman SJ. Does generalized anxiety disorder predict coronary heart disease risk factors independently of major depressive disorder? J Affect Disord. 2005;88:87-91.

10. Bruffaerts R, Demyttenaere K, Kessler RC, et al. The associations between preexisting mental disorders and subsequent onset of chronic headaches: a worldwide epidemiologic perspective. J Pain. 2015;16:42-52.

11. Husky MM, Olfson M, He J, et al. Twelve-month suicidal symptoms and use of services among adolescents: results from the National Comorbidity Survey. Psychiatr Serv. 2012;63:989-996.

12. Nepon J, Belik S, Bolton J, et al. The relationship between anxiety disorders and suicide attempts: findings from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Depress Anxiety. 2010;27:791–798.

13. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Generalised anxiety disorder and panic disorder adults: management. nice.org.uk/guidance/cg113. Accessed August 20, 2020.

14. Dell’Osso B, Camuri G, Benatti B, et al. Differences in latency to first pharmacological treatment (duration of untreated illness) in anxiety disorders: a study on patients with panic disorder, generalized anxiety disorder and obsessive-compulsive disorder. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2013;7:374-380.

15. Hales RE, Yudofsky SC, Roberts LW, eds. Textbook of Psychiatry, 6th ed. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing: 2014:391-430.

16. Fernandez F, Levy JK, Lachar BL, et al. The management of depression and anxiety in the elderly. J Clin Psychiatry. 1995;56(suppl 2):20-29.

17. Kirkwood CK, Hayes PE. Anxiety disorders. In: DiPiro JT, Talbert RL, Yee GC, et al, eds. Pharmacotherapy: A Pathophysiologic Approach, 3rd ed. Stamford, Conn: Appleton & Lange;1997:1443-1462.

18. Culpepper L. Generalized anxiety disorder and medical illness. J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;70(suppl 2):20-24.

19. Anderson KG, Dugas MJ, Koerner N, et al. Interpretive style and intolerance of uncertainty in individuals with anxiety disorders: a focus on generalized anxiety disorder. J Anxiety Disord. 2012;26:823-832.

20. Satterfield JM, Feldman MD. Anxiety. In Feldman MD, Christensen JF, Satterfield JM, eds. Behavioral Medicine: A Guide for Clinical Practice. New York: McGraw Hill; 2014:271-282.

21. Grist R, Porter J, Stallard P. Mental health mobile apps for preadolescents and adolescents: A systematic review. J Med Internet Res. 2017;19:e176.

22. Rollnick S, Miller W, Butler C. Motivational Interviewing in Health Care: Helping Patients Change Behavior. 1st ed. New York: The Guilford Press; 2008:34-35.

23. Strawn JR, Geriacioti L, Rajdev N, et al. Pharmacotherapy for generalized anxiety disorder in adult and pediatric patients: an evidence-based review. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2018;19:1057-1070.

24. Ehmke CJ, Nemeroff CB. Paroxetine. In Schatzberg AF, Nemeroff CB, eds. Textbook of Psychopharmacology, 4th ed. Washington, D.C.: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc.; 2009:321-352.

25. Huh J, Goebert D, Takeshita J, et al. Treatment of generalized anxiety disorder: a comprehensive review of the literature for psychopharmacologic alternatives to newer antidepressants and benzodiazepines. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2011;13: doi:10.4088/PCC.08r00709blu.

1. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, et al. Anxiety disorders in primary care: prevalence, impairment, comorbidity, and detection. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146:317-325.

2. Ruscio AM, Hallion LS, Lim CCW, et al. Cross-sectional comparison of the epidemiology of DSM-5 generalized anxiety disorder across the globe. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74:465-475.

3. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition (DSM-5). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013.

4. Fernandez S. Anxiety disorders in childhood and adolescence: a primary care approach. Pediatr Ann. 2017;46:e213-e216.

5. Connolly SD, Bernstein GA. Practice parameter for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with anxiety disorders. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2007;46:267-283.

6. Reinhold JA, Rickels K. Pharmacological treatments for generalized anxiety disorder in adults: an update. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2015;16:1669-1681.

7. Kujanpää TS, Jokelainen J, Auvinen JP, et al. The association of generalized anxiety disorder and somatic symptoms with frequent attendance to healthcare services: a cross-sectional study from the Northern Finland Birth Cohort 1966. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2017:52:147-159.

8. Ramsawh HJ, Chavira DA, Stein MB. Burden of anxiety disorders in pediatric medical settings: prevalence, phenomenology, and a research agenda. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2010;164:965-972. doi:10.1001/archpediatrics.2010.170.

9. Barger SD, Sydeman SJ. Does generalized anxiety disorder predict coronary heart disease risk factors independently of major depressive disorder? J Affect Disord. 2005;88:87-91.

10. Bruffaerts R, Demyttenaere K, Kessler RC, et al. The associations between preexisting mental disorders and subsequent onset of chronic headaches: a worldwide epidemiologic perspective. J Pain. 2015;16:42-52.

11. Husky MM, Olfson M, He J, et al. Twelve-month suicidal symptoms and use of services among adolescents: results from the National Comorbidity Survey. Psychiatr Serv. 2012;63:989-996.

12. Nepon J, Belik S, Bolton J, et al. The relationship between anxiety disorders and suicide attempts: findings from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Depress Anxiety. 2010;27:791–798.

13. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Generalised anxiety disorder and panic disorder adults: management. nice.org.uk/guidance/cg113. Accessed August 20, 2020.

14. Dell’Osso B, Camuri G, Benatti B, et al. Differences in latency to first pharmacological treatment (duration of untreated illness) in anxiety disorders: a study on patients with panic disorder, generalized anxiety disorder and obsessive-compulsive disorder. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2013;7:374-380.

15. Hales RE, Yudofsky SC, Roberts LW, eds. Textbook of Psychiatry, 6th ed. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing: 2014:391-430.

16. Fernandez F, Levy JK, Lachar BL, et al. The management of depression and anxiety in the elderly. J Clin Psychiatry. 1995;56(suppl 2):20-29.

17. Kirkwood CK, Hayes PE. Anxiety disorders. In: DiPiro JT, Talbert RL, Yee GC, et al, eds. Pharmacotherapy: A Pathophysiologic Approach, 3rd ed. Stamford, Conn: Appleton & Lange;1997:1443-1462.

18. Culpepper L. Generalized anxiety disorder and medical illness. J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;70(suppl 2):20-24.

19. Anderson KG, Dugas MJ, Koerner N, et al. Interpretive style and intolerance of uncertainty in individuals with anxiety disorders: a focus on generalized anxiety disorder. J Anxiety Disord. 2012;26:823-832.

20. Satterfield JM, Feldman MD. Anxiety. In Feldman MD, Christensen JF, Satterfield JM, eds. Behavioral Medicine: A Guide for Clinical Practice. New York: McGraw Hill; 2014:271-282.

21. Grist R, Porter J, Stallard P. Mental health mobile apps for preadolescents and adolescents: A systematic review. J Med Internet Res. 2017;19:e176.

22. Rollnick S, Miller W, Butler C. Motivational Interviewing in Health Care: Helping Patients Change Behavior. 1st ed. New York: The Guilford Press; 2008:34-35.

23. Strawn JR, Geriacioti L, Rajdev N, et al. Pharmacotherapy for generalized anxiety disorder in adult and pediatric patients: an evidence-based review. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2018;19:1057-1070.

24. Ehmke CJ, Nemeroff CB. Paroxetine. In Schatzberg AF, Nemeroff CB, eds. Textbook of Psychopharmacology, 4th ed. Washington, D.C.: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc.; 2009:321-352.

25. Huh J, Goebert D, Takeshita J, et al. Treatment of generalized anxiety disorder: a comprehensive review of the literature for psychopharmacologic alternatives to newer antidepressants and benzodiazepines. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2011;13: doi:10.4088/PCC.08r00709blu.