User login

Prevention of Venous Thromboembolism

Venous thromboembolism (VTE), including deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE), is a serious and growing public health problem. In the United States an estimated 900,000 people are affected and more than 100,000 die from VTE or related complications each year. More than half of VTE events occur in association with hospitalization or major surgery; many are thought to be preventable.[1, 2, 3, 4, 5] The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ),[6, 7, 8, 9] among other organizations, have identified VTE as a potentially preventable never event. Evidence‐based guidelines and resources exist to help support hospital‐acquired venous thromboembolism (HA‐VTE) prevention.[1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10] Harborview Medical Center, a tertiary referral center with more than 17,000 patients hospitalized annually, many requiring surgery, serves one of the highest‐risk populations for HA‐VTE development. Despite high rates of VTE prophylaxis in accordance with an established institutional guideline,[11, 12] VTE remains the most common hospital‐acquired condition in our institution.

OBJECTIVES

To improve the safety and care of all patients in our medical center and eliminate preventable HA‐VTE events, we set out to: (1) incorporate evidence‐based best practices in VTE prevention and treatment into current practice in alignment with institutional guidelines, (2) standardize the review process for all HA‐VTE events to identify opportunities for improvement, (3) utilize quality improvement (QI) analytics and information technology (IT) to actively improve our processes at the point of care, and (4) share process and outcome performance relating to VTE prevention transparently across our institution

METHODS

To prevent HA‐VTE, we employ a multifactorial strategy that includes designated clinical leadership, active engagement of all care team members, decision support tools embedded in the electronic health record (EHR), QI analytics, and retrospective and prospective reporting that provides ongoing measurement and analysis of the effectiveness of implemented interventions.

Setting/Patients

Harborview Medical Center, a 413‐bed academic tertiary referral center and the only level 1 adult and pediatric trauma and burn center for a 5‐state area, also serves as the primary safety‐net provider in the region. Harborview has centers of excellence in trauma, neurosciences, orthopedic and vascular surgery and rehabilitation, and is the only certified comprehensive stroke center in 5 states. With more than 17,000 admissions annually, including over 6000 trauma cases, HA‐VTE is a disease that spans critical and acute care settings and impacts patients on all clinical services. Harborview serves a population that is at extremely high risk for VTE as well as bleeding, particularly patients who have sustained central nervous system trauma or polytrauma.

Intervention

In 2010, at the request of the Harborview Medical Executive Board and Medical Director, we formed the Harborview VTE Task Force to assess VTE prevention practices across services and identify improvement opportunities for all hospitalized patients. This multidisciplinary team, co‐chaired by a hospitalist and trauma surgeon, includes representatives from trauma/general surgery, orthopedic surgery, hospital medicine, nursing, pharmacy, and QI. Task force members represent critical and acute care as well as the ambulatory setting. Additional stakeholders and local experts including IT directors and analysts, continuity of care nurses, and other clinical service representatives participate on an ad hoc basis.

Since its inception, the VTE Task Force has met monthly to review performance data and develop improvement initiatives. Initially we collaborated with experts across our health system to update an existing institutional VTE prophylaxis guideline to reflect current evidence‐based standards.[1, 3, 4, 5, 12] We met with all clinical services to ensure that the guidelines incorporated departmental best practices. These guidelines were integrated into our Cerner‐based (Cerner Corp., North Kansas City, MO) computerized provider order entry (CPOE) system to support accurate VTE risk assessment and appropriate ordering of prophylaxis.

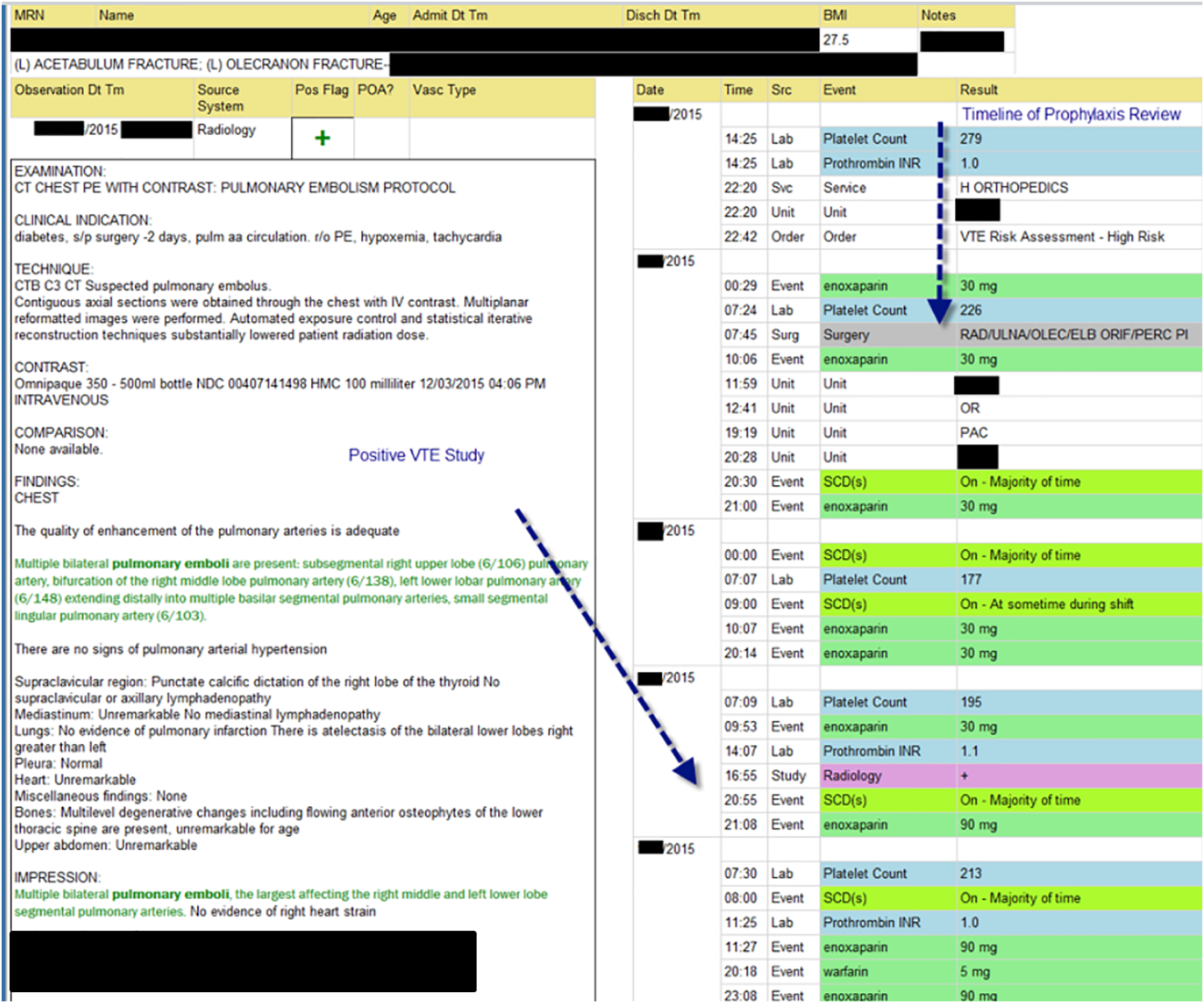

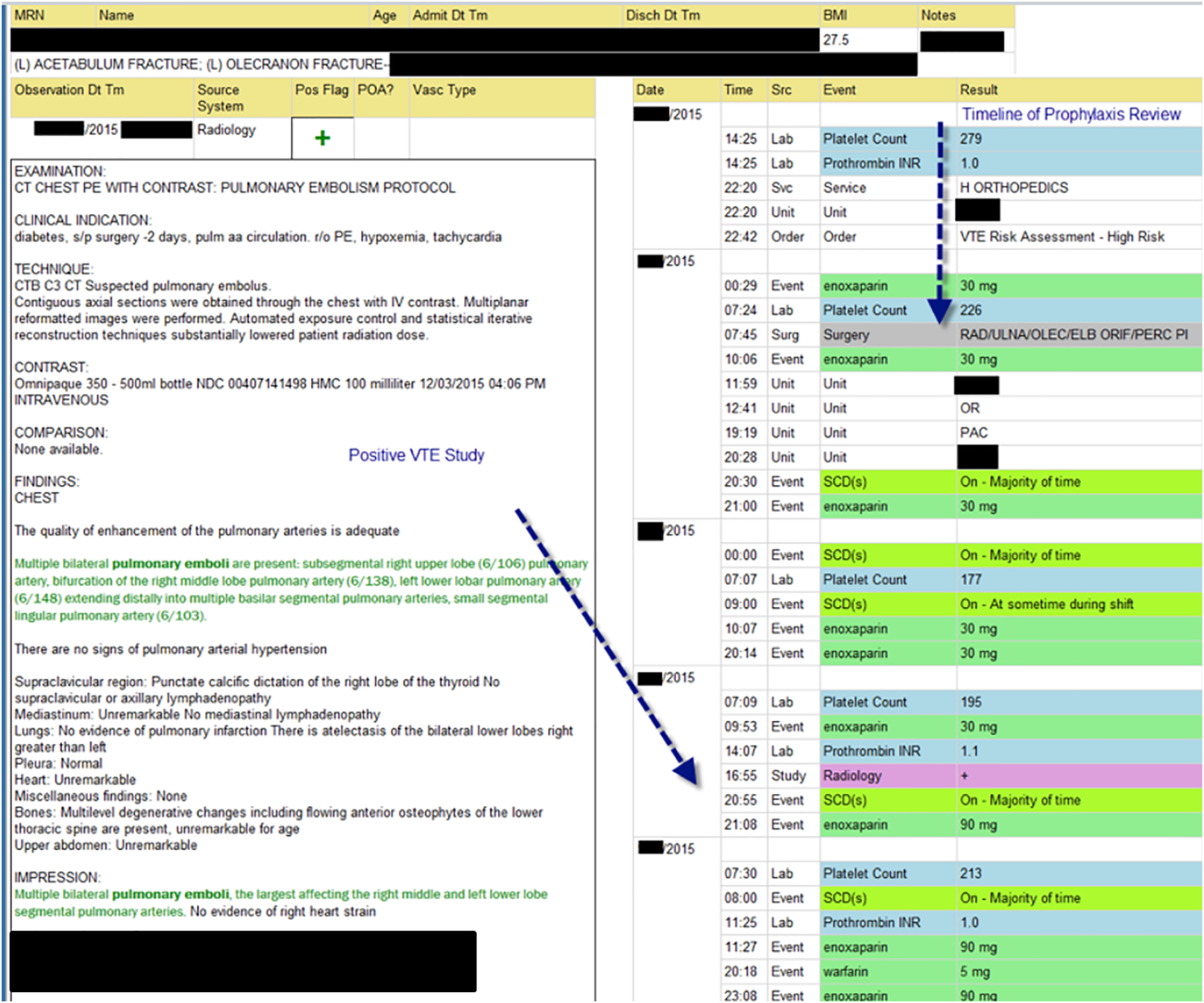

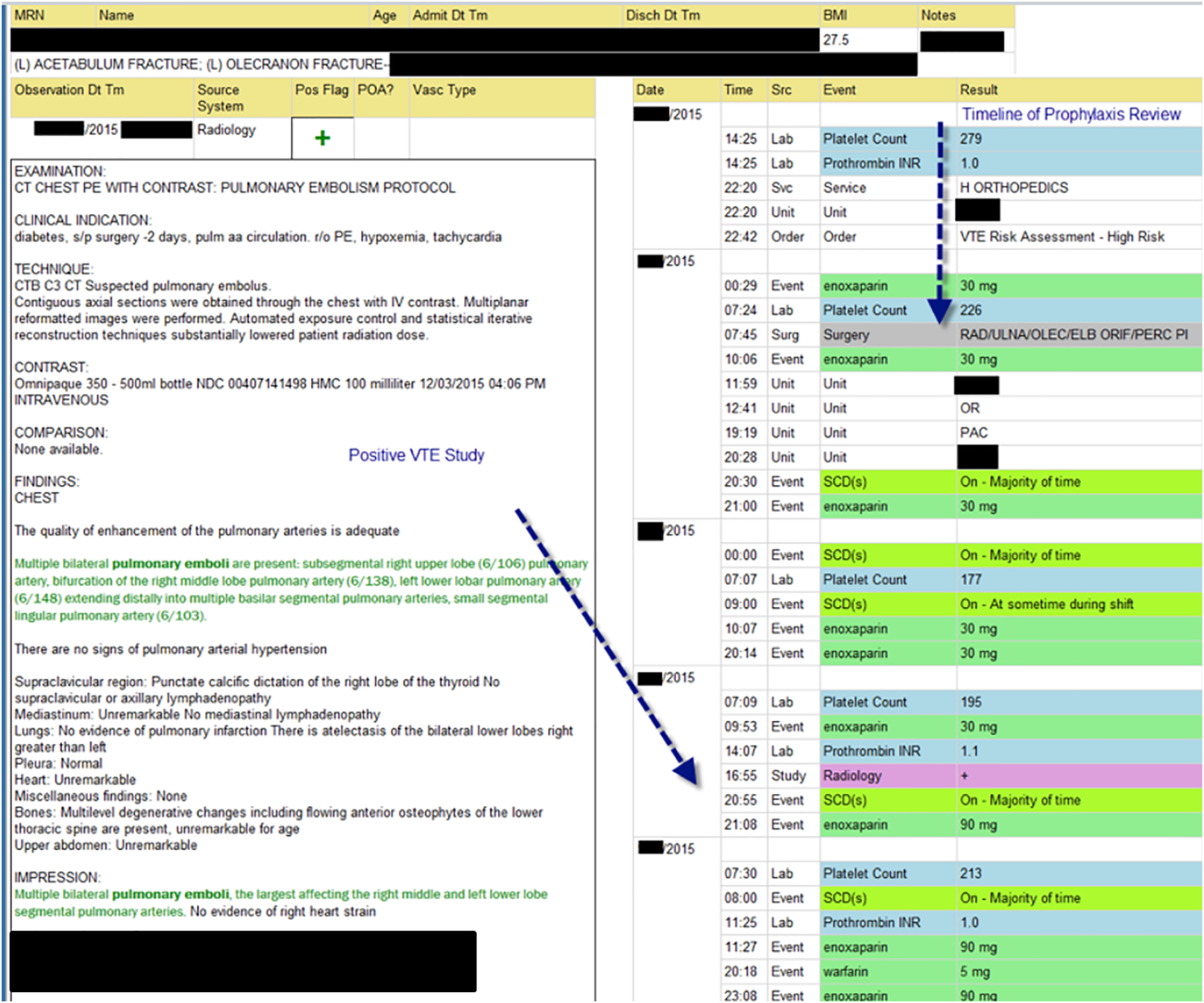

The VTE Task Force collaborated with QI programmers to develop an electronic tool, the Harborview VTE Tool (Figure 1),[13] that allows for efficient, standardized review of all HA‐VTE at monthly meetings. The tool uses word and phrase search capabilities to identify PEs and DVTs from imaging and vascular studies and links those events with pertinent demographic and clinical data from the EHR in a timeline. Information about VTE risk assigned by physicians in the CPOE system is extracted as well as specific VTE prophylaxis and treatment (drug, dose, timing of administration of medications, reason for doses being held, and orders for and application of mechanical prophylaxis). Using the VTE tool, the task force reviews each VTE event to assess the accuracy of VTE risk assignment, the appropriateness of prophylaxis received relative to guidelines, and the adequacy of VTE treatment and follow‐up. This tool has facilitated our review process, decreasing time from >30 minutes of manual chart review per event to several minutes. In recent months, a quality analyst has prescreened all VTEs prior to task force discussion to further improve efficiency. The tool allows the team to assess the case together and reach consensus regarding VTE prevention.

Prompt event reviews allow the task force to provide timely feedback about specific VTE events to physicians, nurses, and pharmacists. Cases with potential opportunities for improvement are referred to a medical center‐wide QI committee for secondary review. Areas of opportunity identified are tracked and trended to direct ongoing system improvement cycles. In 2014, as a result of reviewing patient cases with VTE diagnosed after discharge, we began a similar review process to assess current practice and standardize prophylaxis across care transitions.

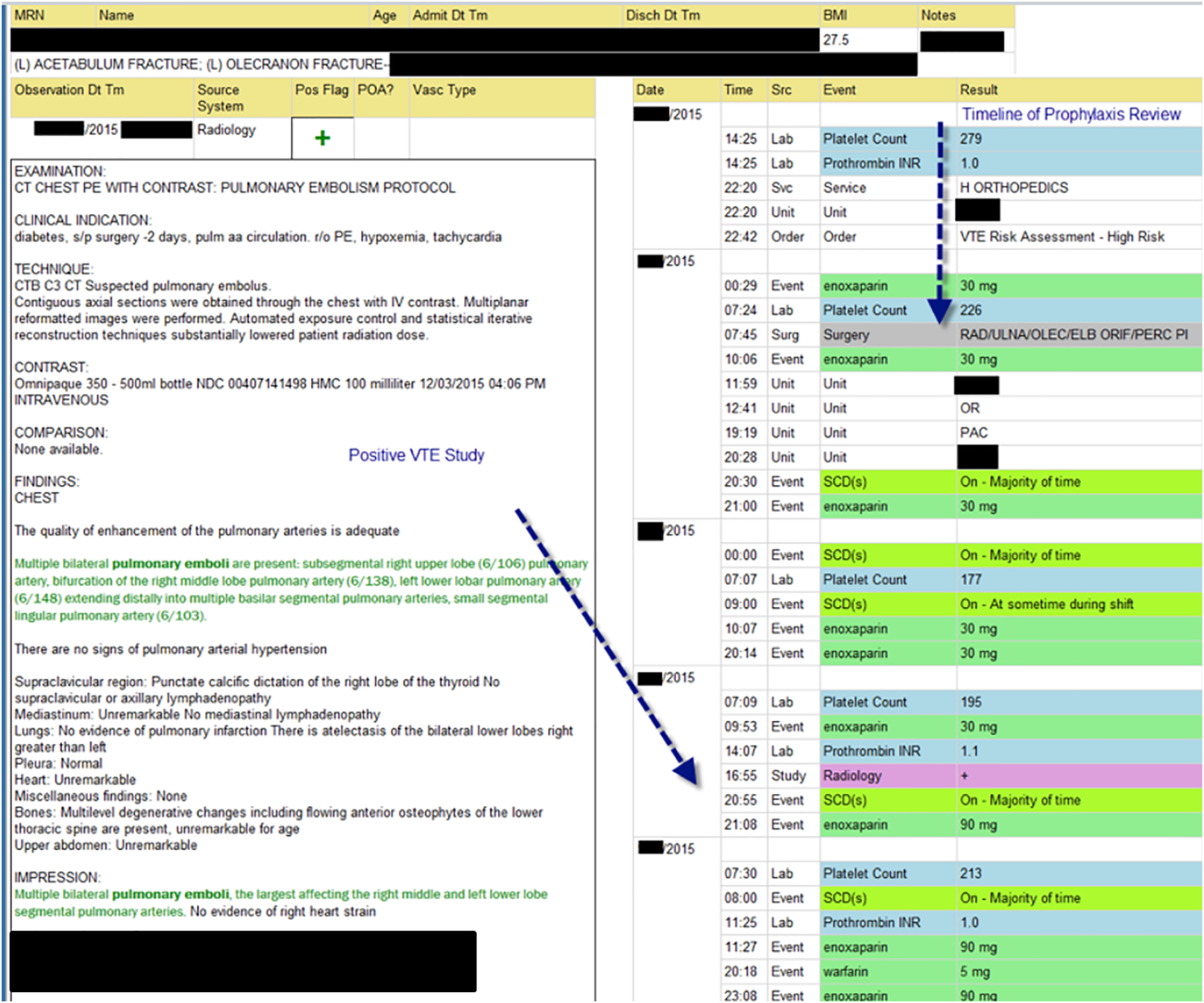

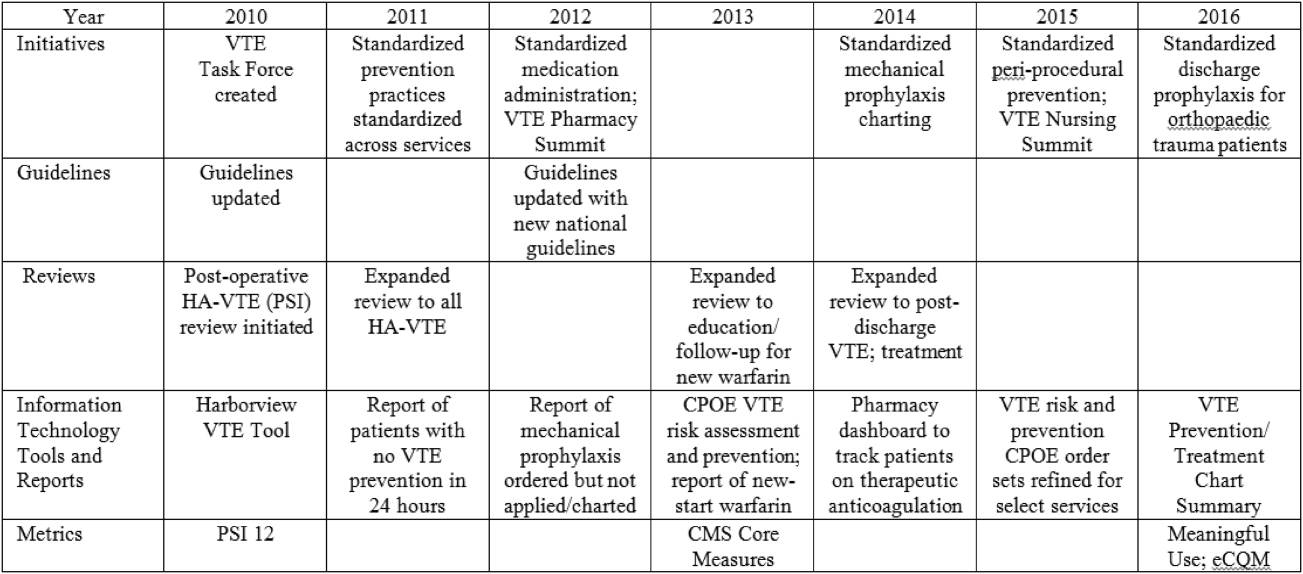

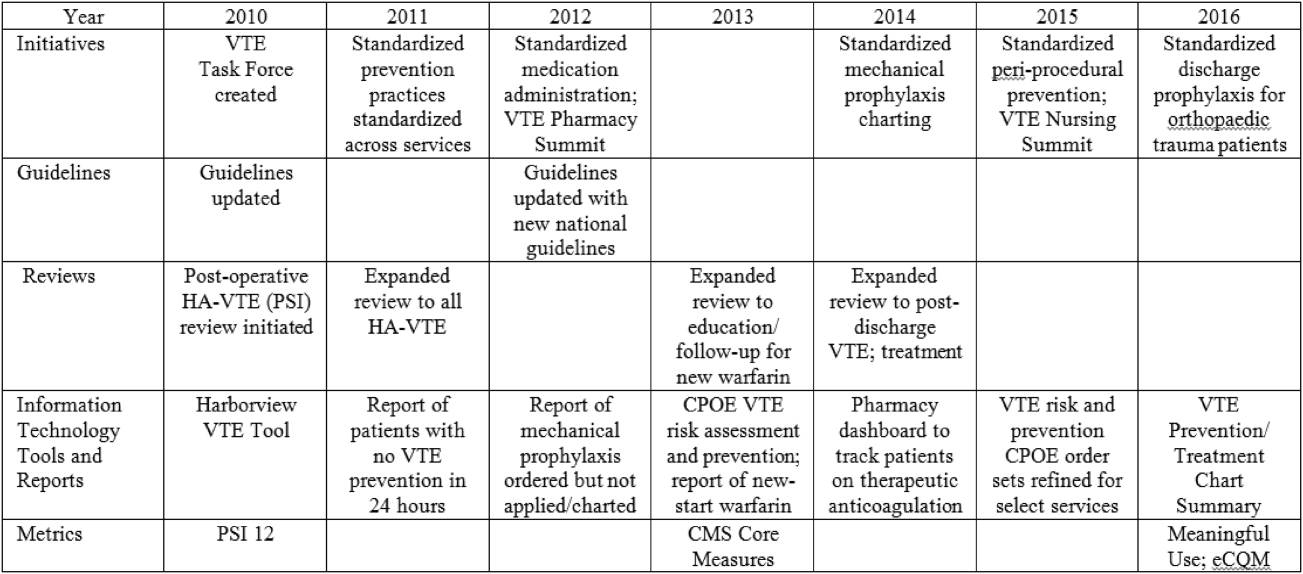

In response to opportunities identified from reviews, the VTE Task Force developed multiple reporting tools that provide real‐time, actionable information to clinicians at the bedside. Daily electronic lists highlight patients who have not received chemical or mechanical prophylaxis in 24 hours and are utilized by nursing, pharmacy, and physician groups. Patients receiving new start vitamin K antagonists or direct oral anticoagulants are identified for pharmacists and discharge care coordinators to support early patient/family education and ensure appropriate follow‐up. Based on input from frontline providers, tools are continually refined to improve their clinical utility. A timeline of initiatives that the Harborview VTE Task Force has championed is outlined in Figure 2.

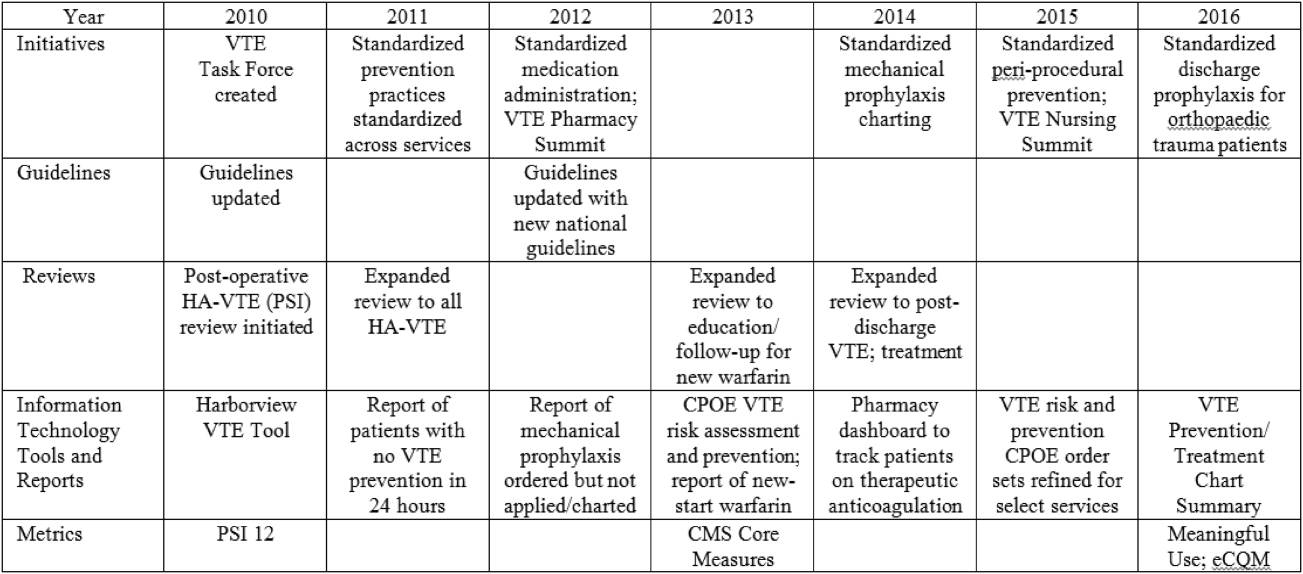

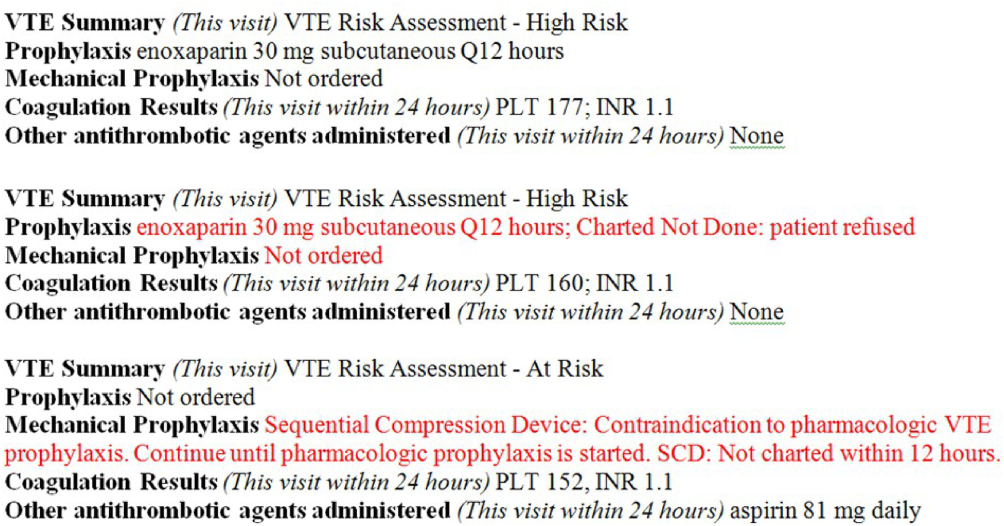

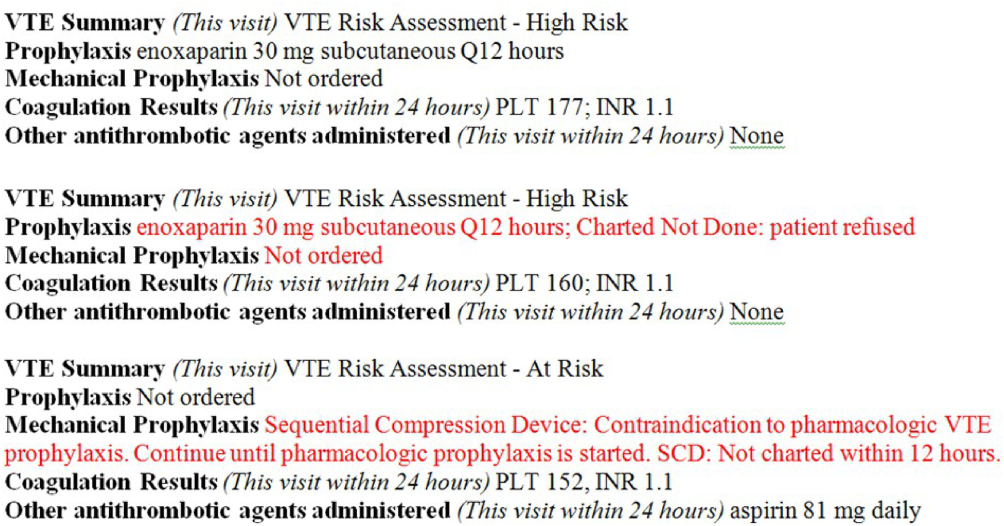

To bring HA‐VTE prevention information to the point of care, we developed a VTE Prevention/Treatment Summary within the EHR (Figure 3). Information about VTE risk assigned by the physician based on guidelines, current prophylaxis orders (pharmacologic/nonpharmacologic) and administration status, therapeutic anticoagulation and pertinent laboratory values are imported into a summary snapshot that can be accessed on demand by any member of the care team from within the patient's chart. The same data elements are being imbedded in resident physician and nursing handoff tools to highlight VTE prevention for all hospitalized patients and ensure optimal prophylaxis at transitions of care.

To emphasize Harborview's commitment to VTE prevention and ensure that care providers across the institution are aware of and engaged in this effort, we utilize our intranet to disseminate information in a fully transparent manner. Both process and outcome measures are available to all physicians and staff at service and unit levels on a Web‐based institutional dashboard. Data are updated monthly by QI analysts and improvement opportunities are highlighted in multiple fora. Descriptions of the quality metrics that are tracked are summarized in Table 1.

| Quality Metric | Description |

|---|---|

| |

| AHRQ PSI 12 | Cases of VTE not present on admission per 1000 surgical discharges with select operating room procedures |

| CMS Core Measure VTE‐1 | Percent of patients without VTE who received VTE prophylaxis on day of or day after arrival to an acute care area, random sample |

| CMS Core Measure VTE‐2 | Percent of patients without VTE who received VTE prophylaxis on day of or day after arrival to an intensive care unit or surgery date, random sample |

| CMS Core Measure VTE 5 | Percent of patients with hospital acquired VTE discharged to home on warfarin who received education and written discharge instructions |

| CMS Core Measure VTE‐6 | Percent of patients with hospital‐acquired VTE who received VTE prophylaxis prior to the event diagnosis |

MEASUREMENTS

Outcomes

Harborview benchmarks performance against hospitals nationally using the CMS Hospital Compare data and with peer academic institutions through Vizient data (Vizient, Irving, TX). To measure the impact of our initiatives, the task force began tracking postoperative VTE rates based on the AHRQ Patient Safety Indicator (PSI) 12 and expanded to include HA‐VTE rates for all hospitalized patients. We also report performance on Core Measure VTE‐6: incidence of potentially preventable VTE.

Process

We monitor VTE prophylaxis compliance based on the CMS Core Measures VTE‐1 and 2, random samples of acute and critical care patients without VTE. Internally, we measure compliance with guideline‐directed therapy for all HA‐VTE cases reviewed by the task force. With the upcoming retirement of the CMS chart‐abstracted measures, we are developing methods to track appropriate VTE prophylaxis provided to all eligible patients and will replace the sampled populations with this more expansive dataset. This approach will provide information for further improvements in VTE prophylaxis and act as an important step for success with the Electronic Clinical Quality Measures under the Meaningful Use program.

RESULTS

Our VTE prevention initiatives have resulted in improved compliance with our institutional guideline‐directed VTE prophylaxis and a decrease in HA‐VTE at our institution.

VTE Core Measures

Since the inception of VTE Core Measures in 2013, our annual performance on VTE‐1: prophylaxis for acute care patients has been above 95% and VTE‐2: prophylaxis for critical care patients has been above 98%. This performance has been consistently above the national mean for both measures (VTE‐1: 91% among Washington state hospitals and 93% nationally; VTE‐2: 95% among Washington state hospitals and 97% nationally). The CMS Hospital Compare current public reporting period is based on information collected from July 2014 through June 2015. Our internal performance for calendar year 2015 was 96% (289 of 302) for VTE‐1 and 98% (235 of 241) for VTE‐2.

Harborview has had zero potentially preventable VTE events (VTE‐6) compared with a reported national average of 4% since the inception of these measures in January 2013.

Guideline‐Directed VTE Prevention: Patients Diagnosed With HA‐VTE

The task force reviews each case to determine if the patient received guideline‐adherent prophylaxis on every day prior to the event. Patients with active bleeding or those with high bleeding risk should have mechanical prophylaxis ordered and applied until pharmacologic prophylaxis is appropriate. Any missed single dose of pharmacologic prophylaxis or missed day of applied mechanical prophylaxis is considered a possible opportunity for improvement, and the case is referred to the appropriate clinical service for additional review.

Since task force launch, the percent of all patients diagnosed with HA‐VTE who received guideline‐directed prophylaxis increased 7% from 86% (105 of 122) in 2012 to 92% (80 of 87) in the first 9 months of 2015. Of events with possible opportunities, most were deemed not to have been preventable. Some trauma patients were ineligible for pharmacologic and mechanical prophylaxis, some were prophylaxed according to the best available evidence, and some had risk factors (for example, active malignancy) only identified after the VTE event. The few remaining events highlighted opportunities regarding standardization of pharmacologic prophylaxis periprocedurally, documentation of application of mechanical prophylaxis, and communication of patient refusal of doses, all ongoing focus areas for improvement.

Reduction in HA‐VTE

Improved VTE prophylaxis has contributed to a 15% reduction in HA‐VTE in all hospitalized patients over 5 years from a rate of 7.5 events/1000 inpatients in 2011 to 6.4/1000 inpatients for the first 9 months of 2015. Among postoperative patients (AHRQ PSI 12), the rate of VTE decreased 21% from 11.7/1000 patients in 2011 to 9.3/1000 patients in the first 9 months of 2015.

Patient/Family Engagement

We further improved our processes to ensure that patients with HA‐VTE who discharge to home receive written discharge instructions for warfarin use (VTE‐5). In 2014, performance on this measure was 91% (51 of 56 eligible patients) and in 2015 performance improved to 96% (78 of 81 eligible patients) compared with a reported national average of 91%. Additionally, 97% (79 of 81) of patients who discharged home on warfarin after HA‐VTE now have outpatient anticoagulation follow‐up arranged prior to hospital discharge. We are developing new initiatives for patient and family education regarding direct oral anticoagulants.

Discussion/Conclusions

With interdisciplinary teamwork and use of QI analytics to drive transparency, we have improved VTE prevention and reduced rates of HA‐VTE. Harborview's HA‐VTE prevention initiative can be duplicated by other organizations given the structured nature of the intervention. The multidisciplinary approach, clinical presence of task force members, and support and engagement of senior clinical leadership have been key elements to our program's success. The existence of a standard institutional guideline based on evidence‐based national guidelines and incorporation of these standards into the EHR is vital. The VTE task force has consistently used QI analytics both for retrospective review and real‐time data feedback. Complete and easy accessibility and transparency of performance at the service and unit level supports accountability. Integration of the task force work into existing institutional QI structures has further led to improvements in patient safety.

Ongoing task force collaboration and communication with frontline providers and clinical departments has been critical to engagement and sustained improvements in VTE prevention and treatment. The work of the VTE task force represents the steadfast commitment of Harborview and our clinical staff to prevent preventable harm. This multidisciplinary effort has served as a model for other QI initiatives across our institution and health system.

Disclosure

Nothing to report.

- , , , et al. Executive Summary: Antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence‐based Clinical Guidelines. Chest. 2012;141(2 suppl):7S–47S.

- , , , . Venous thromboembolism: a public health concern. Am J Prev Med. 2010;38(4 suppl):S495–S501.

- , , , et al. Prevention of VTE in orthopedic surgery patients. Antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence‐based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest. 2012;141(2 suppl):e278S–e325S.

- , , , et al. Prevention of VTE in nonsurgical patients. Antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence‐based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest. 2012;141(2 suppl):e195S–e226S.

- , , , et al; American College of Chest Physicians. Prevention of VTE in nonorthopedic surgical patients. Antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence‐Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest. 2012;141(2 suppl):e227S–e277S.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Core measures. Available at: https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality‐Initiatives‐Patient‐Assessment‐Instruments/QualityMeasures/Core‐Measures.html. Accessed September 1, 2016.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Venous thromboembolism. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/dvt/index.html. Accessed September 1, 2016.

- . Preventing hospital‐associated venous thromboembolism: a guide for effective quality improvement, 2nd ed. AHRQ Publication No. 16‐0001‐EF. Rockville MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2016.

- . Preventing hospital‐associated venous thromboembolism: a guide for effective quality improvement. Available at: http://www.ahrq.gov/professionals/quality‐patient‐safety/patient‐safety‐resources/resources/vtguide/index.html. Accessed September 1, 2016.

- , . Preventing hospital‐acquired venous‐thromboembolism, a guide for effective quality improvement. Version 3.3. Venous Thromboembolism Quality Improvement Implementation Toolkit. Society of Hospital Medicine website. Available at: http://www.hospitalmedicine.org. Accessed September 1, 2016.

- , , , , . Adherence to guideline‐directed venous thromboembolism prophylaxis among medical and surgical inpatients at 33 academic medical centers in the United States. Am J Med Qual. 2010;26(3):174–180.

- UW Medicine guidelines for prevention of venous thromboembolism (VTE) in hospitalized patients. Available at: https://depts.washington.edu/anticoag/home. Accessed June 13, 2016.

- , , , , , . Upper extremity deep vein thrombosis in hospitalized patients: a descriptive study. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(1):48–53.

Venous thromboembolism (VTE), including deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE), is a serious and growing public health problem. In the United States an estimated 900,000 people are affected and more than 100,000 die from VTE or related complications each year. More than half of VTE events occur in association with hospitalization or major surgery; many are thought to be preventable.[1, 2, 3, 4, 5] The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ),[6, 7, 8, 9] among other organizations, have identified VTE as a potentially preventable never event. Evidence‐based guidelines and resources exist to help support hospital‐acquired venous thromboembolism (HA‐VTE) prevention.[1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10] Harborview Medical Center, a tertiary referral center with more than 17,000 patients hospitalized annually, many requiring surgery, serves one of the highest‐risk populations for HA‐VTE development. Despite high rates of VTE prophylaxis in accordance with an established institutional guideline,[11, 12] VTE remains the most common hospital‐acquired condition in our institution.

OBJECTIVES

To improve the safety and care of all patients in our medical center and eliminate preventable HA‐VTE events, we set out to: (1) incorporate evidence‐based best practices in VTE prevention and treatment into current practice in alignment with institutional guidelines, (2) standardize the review process for all HA‐VTE events to identify opportunities for improvement, (3) utilize quality improvement (QI) analytics and information technology (IT) to actively improve our processes at the point of care, and (4) share process and outcome performance relating to VTE prevention transparently across our institution

METHODS

To prevent HA‐VTE, we employ a multifactorial strategy that includes designated clinical leadership, active engagement of all care team members, decision support tools embedded in the electronic health record (EHR), QI analytics, and retrospective and prospective reporting that provides ongoing measurement and analysis of the effectiveness of implemented interventions.

Setting/Patients

Harborview Medical Center, a 413‐bed academic tertiary referral center and the only level 1 adult and pediatric trauma and burn center for a 5‐state area, also serves as the primary safety‐net provider in the region. Harborview has centers of excellence in trauma, neurosciences, orthopedic and vascular surgery and rehabilitation, and is the only certified comprehensive stroke center in 5 states. With more than 17,000 admissions annually, including over 6000 trauma cases, HA‐VTE is a disease that spans critical and acute care settings and impacts patients on all clinical services. Harborview serves a population that is at extremely high risk for VTE as well as bleeding, particularly patients who have sustained central nervous system trauma or polytrauma.

Intervention

In 2010, at the request of the Harborview Medical Executive Board and Medical Director, we formed the Harborview VTE Task Force to assess VTE prevention practices across services and identify improvement opportunities for all hospitalized patients. This multidisciplinary team, co‐chaired by a hospitalist and trauma surgeon, includes representatives from trauma/general surgery, orthopedic surgery, hospital medicine, nursing, pharmacy, and QI. Task force members represent critical and acute care as well as the ambulatory setting. Additional stakeholders and local experts including IT directors and analysts, continuity of care nurses, and other clinical service representatives participate on an ad hoc basis.

Since its inception, the VTE Task Force has met monthly to review performance data and develop improvement initiatives. Initially we collaborated with experts across our health system to update an existing institutional VTE prophylaxis guideline to reflect current evidence‐based standards.[1, 3, 4, 5, 12] We met with all clinical services to ensure that the guidelines incorporated departmental best practices. These guidelines were integrated into our Cerner‐based (Cerner Corp., North Kansas City, MO) computerized provider order entry (CPOE) system to support accurate VTE risk assessment and appropriate ordering of prophylaxis.

The VTE Task Force collaborated with QI programmers to develop an electronic tool, the Harborview VTE Tool (Figure 1),[13] that allows for efficient, standardized review of all HA‐VTE at monthly meetings. The tool uses word and phrase search capabilities to identify PEs and DVTs from imaging and vascular studies and links those events with pertinent demographic and clinical data from the EHR in a timeline. Information about VTE risk assigned by physicians in the CPOE system is extracted as well as specific VTE prophylaxis and treatment (drug, dose, timing of administration of medications, reason for doses being held, and orders for and application of mechanical prophylaxis). Using the VTE tool, the task force reviews each VTE event to assess the accuracy of VTE risk assignment, the appropriateness of prophylaxis received relative to guidelines, and the adequacy of VTE treatment and follow‐up. This tool has facilitated our review process, decreasing time from >30 minutes of manual chart review per event to several minutes. In recent months, a quality analyst has prescreened all VTEs prior to task force discussion to further improve efficiency. The tool allows the team to assess the case together and reach consensus regarding VTE prevention.

Prompt event reviews allow the task force to provide timely feedback about specific VTE events to physicians, nurses, and pharmacists. Cases with potential opportunities for improvement are referred to a medical center‐wide QI committee for secondary review. Areas of opportunity identified are tracked and trended to direct ongoing system improvement cycles. In 2014, as a result of reviewing patient cases with VTE diagnosed after discharge, we began a similar review process to assess current practice and standardize prophylaxis across care transitions.

In response to opportunities identified from reviews, the VTE Task Force developed multiple reporting tools that provide real‐time, actionable information to clinicians at the bedside. Daily electronic lists highlight patients who have not received chemical or mechanical prophylaxis in 24 hours and are utilized by nursing, pharmacy, and physician groups. Patients receiving new start vitamin K antagonists or direct oral anticoagulants are identified for pharmacists and discharge care coordinators to support early patient/family education and ensure appropriate follow‐up. Based on input from frontline providers, tools are continually refined to improve their clinical utility. A timeline of initiatives that the Harborview VTE Task Force has championed is outlined in Figure 2.

To bring HA‐VTE prevention information to the point of care, we developed a VTE Prevention/Treatment Summary within the EHR (Figure 3). Information about VTE risk assigned by the physician based on guidelines, current prophylaxis orders (pharmacologic/nonpharmacologic) and administration status, therapeutic anticoagulation and pertinent laboratory values are imported into a summary snapshot that can be accessed on demand by any member of the care team from within the patient's chart. The same data elements are being imbedded in resident physician and nursing handoff tools to highlight VTE prevention for all hospitalized patients and ensure optimal prophylaxis at transitions of care.

To emphasize Harborview's commitment to VTE prevention and ensure that care providers across the institution are aware of and engaged in this effort, we utilize our intranet to disseminate information in a fully transparent manner. Both process and outcome measures are available to all physicians and staff at service and unit levels on a Web‐based institutional dashboard. Data are updated monthly by QI analysts and improvement opportunities are highlighted in multiple fora. Descriptions of the quality metrics that are tracked are summarized in Table 1.

| Quality Metric | Description |

|---|---|

| |

| AHRQ PSI 12 | Cases of VTE not present on admission per 1000 surgical discharges with select operating room procedures |

| CMS Core Measure VTE‐1 | Percent of patients without VTE who received VTE prophylaxis on day of or day after arrival to an acute care area, random sample |

| CMS Core Measure VTE‐2 | Percent of patients without VTE who received VTE prophylaxis on day of or day after arrival to an intensive care unit or surgery date, random sample |

| CMS Core Measure VTE 5 | Percent of patients with hospital acquired VTE discharged to home on warfarin who received education and written discharge instructions |

| CMS Core Measure VTE‐6 | Percent of patients with hospital‐acquired VTE who received VTE prophylaxis prior to the event diagnosis |

MEASUREMENTS

Outcomes

Harborview benchmarks performance against hospitals nationally using the CMS Hospital Compare data and with peer academic institutions through Vizient data (Vizient, Irving, TX). To measure the impact of our initiatives, the task force began tracking postoperative VTE rates based on the AHRQ Patient Safety Indicator (PSI) 12 and expanded to include HA‐VTE rates for all hospitalized patients. We also report performance on Core Measure VTE‐6: incidence of potentially preventable VTE.

Process

We monitor VTE prophylaxis compliance based on the CMS Core Measures VTE‐1 and 2, random samples of acute and critical care patients without VTE. Internally, we measure compliance with guideline‐directed therapy for all HA‐VTE cases reviewed by the task force. With the upcoming retirement of the CMS chart‐abstracted measures, we are developing methods to track appropriate VTE prophylaxis provided to all eligible patients and will replace the sampled populations with this more expansive dataset. This approach will provide information for further improvements in VTE prophylaxis and act as an important step for success with the Electronic Clinical Quality Measures under the Meaningful Use program.

RESULTS

Our VTE prevention initiatives have resulted in improved compliance with our institutional guideline‐directed VTE prophylaxis and a decrease in HA‐VTE at our institution.

VTE Core Measures

Since the inception of VTE Core Measures in 2013, our annual performance on VTE‐1: prophylaxis for acute care patients has been above 95% and VTE‐2: prophylaxis for critical care patients has been above 98%. This performance has been consistently above the national mean for both measures (VTE‐1: 91% among Washington state hospitals and 93% nationally; VTE‐2: 95% among Washington state hospitals and 97% nationally). The CMS Hospital Compare current public reporting period is based on information collected from July 2014 through June 2015. Our internal performance for calendar year 2015 was 96% (289 of 302) for VTE‐1 and 98% (235 of 241) for VTE‐2.

Harborview has had zero potentially preventable VTE events (VTE‐6) compared with a reported national average of 4% since the inception of these measures in January 2013.

Guideline‐Directed VTE Prevention: Patients Diagnosed With HA‐VTE

The task force reviews each case to determine if the patient received guideline‐adherent prophylaxis on every day prior to the event. Patients with active bleeding or those with high bleeding risk should have mechanical prophylaxis ordered and applied until pharmacologic prophylaxis is appropriate. Any missed single dose of pharmacologic prophylaxis or missed day of applied mechanical prophylaxis is considered a possible opportunity for improvement, and the case is referred to the appropriate clinical service for additional review.

Since task force launch, the percent of all patients diagnosed with HA‐VTE who received guideline‐directed prophylaxis increased 7% from 86% (105 of 122) in 2012 to 92% (80 of 87) in the first 9 months of 2015. Of events with possible opportunities, most were deemed not to have been preventable. Some trauma patients were ineligible for pharmacologic and mechanical prophylaxis, some were prophylaxed according to the best available evidence, and some had risk factors (for example, active malignancy) only identified after the VTE event. The few remaining events highlighted opportunities regarding standardization of pharmacologic prophylaxis periprocedurally, documentation of application of mechanical prophylaxis, and communication of patient refusal of doses, all ongoing focus areas for improvement.

Reduction in HA‐VTE

Improved VTE prophylaxis has contributed to a 15% reduction in HA‐VTE in all hospitalized patients over 5 years from a rate of 7.5 events/1000 inpatients in 2011 to 6.4/1000 inpatients for the first 9 months of 2015. Among postoperative patients (AHRQ PSI 12), the rate of VTE decreased 21% from 11.7/1000 patients in 2011 to 9.3/1000 patients in the first 9 months of 2015.

Patient/Family Engagement

We further improved our processes to ensure that patients with HA‐VTE who discharge to home receive written discharge instructions for warfarin use (VTE‐5). In 2014, performance on this measure was 91% (51 of 56 eligible patients) and in 2015 performance improved to 96% (78 of 81 eligible patients) compared with a reported national average of 91%. Additionally, 97% (79 of 81) of patients who discharged home on warfarin after HA‐VTE now have outpatient anticoagulation follow‐up arranged prior to hospital discharge. We are developing new initiatives for patient and family education regarding direct oral anticoagulants.

Discussion/Conclusions

With interdisciplinary teamwork and use of QI analytics to drive transparency, we have improved VTE prevention and reduced rates of HA‐VTE. Harborview's HA‐VTE prevention initiative can be duplicated by other organizations given the structured nature of the intervention. The multidisciplinary approach, clinical presence of task force members, and support and engagement of senior clinical leadership have been key elements to our program's success. The existence of a standard institutional guideline based on evidence‐based national guidelines and incorporation of these standards into the EHR is vital. The VTE task force has consistently used QI analytics both for retrospective review and real‐time data feedback. Complete and easy accessibility and transparency of performance at the service and unit level supports accountability. Integration of the task force work into existing institutional QI structures has further led to improvements in patient safety.

Ongoing task force collaboration and communication with frontline providers and clinical departments has been critical to engagement and sustained improvements in VTE prevention and treatment. The work of the VTE task force represents the steadfast commitment of Harborview and our clinical staff to prevent preventable harm. This multidisciplinary effort has served as a model for other QI initiatives across our institution and health system.

Disclosure

Nothing to report.

Venous thromboembolism (VTE), including deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE), is a serious and growing public health problem. In the United States an estimated 900,000 people are affected and more than 100,000 die from VTE or related complications each year. More than half of VTE events occur in association with hospitalization or major surgery; many are thought to be preventable.[1, 2, 3, 4, 5] The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ),[6, 7, 8, 9] among other organizations, have identified VTE as a potentially preventable never event. Evidence‐based guidelines and resources exist to help support hospital‐acquired venous thromboembolism (HA‐VTE) prevention.[1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10] Harborview Medical Center, a tertiary referral center with more than 17,000 patients hospitalized annually, many requiring surgery, serves one of the highest‐risk populations for HA‐VTE development. Despite high rates of VTE prophylaxis in accordance with an established institutional guideline,[11, 12] VTE remains the most common hospital‐acquired condition in our institution.

OBJECTIVES

To improve the safety and care of all patients in our medical center and eliminate preventable HA‐VTE events, we set out to: (1) incorporate evidence‐based best practices in VTE prevention and treatment into current practice in alignment with institutional guidelines, (2) standardize the review process for all HA‐VTE events to identify opportunities for improvement, (3) utilize quality improvement (QI) analytics and information technology (IT) to actively improve our processes at the point of care, and (4) share process and outcome performance relating to VTE prevention transparently across our institution

METHODS

To prevent HA‐VTE, we employ a multifactorial strategy that includes designated clinical leadership, active engagement of all care team members, decision support tools embedded in the electronic health record (EHR), QI analytics, and retrospective and prospective reporting that provides ongoing measurement and analysis of the effectiveness of implemented interventions.

Setting/Patients

Harborview Medical Center, a 413‐bed academic tertiary referral center and the only level 1 adult and pediatric trauma and burn center for a 5‐state area, also serves as the primary safety‐net provider in the region. Harborview has centers of excellence in trauma, neurosciences, orthopedic and vascular surgery and rehabilitation, and is the only certified comprehensive stroke center in 5 states. With more than 17,000 admissions annually, including over 6000 trauma cases, HA‐VTE is a disease that spans critical and acute care settings and impacts patients on all clinical services. Harborview serves a population that is at extremely high risk for VTE as well as bleeding, particularly patients who have sustained central nervous system trauma or polytrauma.

Intervention

In 2010, at the request of the Harborview Medical Executive Board and Medical Director, we formed the Harborview VTE Task Force to assess VTE prevention practices across services and identify improvement opportunities for all hospitalized patients. This multidisciplinary team, co‐chaired by a hospitalist and trauma surgeon, includes representatives from trauma/general surgery, orthopedic surgery, hospital medicine, nursing, pharmacy, and QI. Task force members represent critical and acute care as well as the ambulatory setting. Additional stakeholders and local experts including IT directors and analysts, continuity of care nurses, and other clinical service representatives participate on an ad hoc basis.

Since its inception, the VTE Task Force has met monthly to review performance data and develop improvement initiatives. Initially we collaborated with experts across our health system to update an existing institutional VTE prophylaxis guideline to reflect current evidence‐based standards.[1, 3, 4, 5, 12] We met with all clinical services to ensure that the guidelines incorporated departmental best practices. These guidelines were integrated into our Cerner‐based (Cerner Corp., North Kansas City, MO) computerized provider order entry (CPOE) system to support accurate VTE risk assessment and appropriate ordering of prophylaxis.

The VTE Task Force collaborated with QI programmers to develop an electronic tool, the Harborview VTE Tool (Figure 1),[13] that allows for efficient, standardized review of all HA‐VTE at monthly meetings. The tool uses word and phrase search capabilities to identify PEs and DVTs from imaging and vascular studies and links those events with pertinent demographic and clinical data from the EHR in a timeline. Information about VTE risk assigned by physicians in the CPOE system is extracted as well as specific VTE prophylaxis and treatment (drug, dose, timing of administration of medications, reason for doses being held, and orders for and application of mechanical prophylaxis). Using the VTE tool, the task force reviews each VTE event to assess the accuracy of VTE risk assignment, the appropriateness of prophylaxis received relative to guidelines, and the adequacy of VTE treatment and follow‐up. This tool has facilitated our review process, decreasing time from >30 minutes of manual chart review per event to several minutes. In recent months, a quality analyst has prescreened all VTEs prior to task force discussion to further improve efficiency. The tool allows the team to assess the case together and reach consensus regarding VTE prevention.

Prompt event reviews allow the task force to provide timely feedback about specific VTE events to physicians, nurses, and pharmacists. Cases with potential opportunities for improvement are referred to a medical center‐wide QI committee for secondary review. Areas of opportunity identified are tracked and trended to direct ongoing system improvement cycles. In 2014, as a result of reviewing patient cases with VTE diagnosed after discharge, we began a similar review process to assess current practice and standardize prophylaxis across care transitions.

In response to opportunities identified from reviews, the VTE Task Force developed multiple reporting tools that provide real‐time, actionable information to clinicians at the bedside. Daily electronic lists highlight patients who have not received chemical or mechanical prophylaxis in 24 hours and are utilized by nursing, pharmacy, and physician groups. Patients receiving new start vitamin K antagonists or direct oral anticoagulants are identified for pharmacists and discharge care coordinators to support early patient/family education and ensure appropriate follow‐up. Based on input from frontline providers, tools are continually refined to improve their clinical utility. A timeline of initiatives that the Harborview VTE Task Force has championed is outlined in Figure 2.

To bring HA‐VTE prevention information to the point of care, we developed a VTE Prevention/Treatment Summary within the EHR (Figure 3). Information about VTE risk assigned by the physician based on guidelines, current prophylaxis orders (pharmacologic/nonpharmacologic) and administration status, therapeutic anticoagulation and pertinent laboratory values are imported into a summary snapshot that can be accessed on demand by any member of the care team from within the patient's chart. The same data elements are being imbedded in resident physician and nursing handoff tools to highlight VTE prevention for all hospitalized patients and ensure optimal prophylaxis at transitions of care.

To emphasize Harborview's commitment to VTE prevention and ensure that care providers across the institution are aware of and engaged in this effort, we utilize our intranet to disseminate information in a fully transparent manner. Both process and outcome measures are available to all physicians and staff at service and unit levels on a Web‐based institutional dashboard. Data are updated monthly by QI analysts and improvement opportunities are highlighted in multiple fora. Descriptions of the quality metrics that are tracked are summarized in Table 1.

| Quality Metric | Description |

|---|---|

| |

| AHRQ PSI 12 | Cases of VTE not present on admission per 1000 surgical discharges with select operating room procedures |

| CMS Core Measure VTE‐1 | Percent of patients without VTE who received VTE prophylaxis on day of or day after arrival to an acute care area, random sample |

| CMS Core Measure VTE‐2 | Percent of patients without VTE who received VTE prophylaxis on day of or day after arrival to an intensive care unit or surgery date, random sample |

| CMS Core Measure VTE 5 | Percent of patients with hospital acquired VTE discharged to home on warfarin who received education and written discharge instructions |

| CMS Core Measure VTE‐6 | Percent of patients with hospital‐acquired VTE who received VTE prophylaxis prior to the event diagnosis |

MEASUREMENTS

Outcomes

Harborview benchmarks performance against hospitals nationally using the CMS Hospital Compare data and with peer academic institutions through Vizient data (Vizient, Irving, TX). To measure the impact of our initiatives, the task force began tracking postoperative VTE rates based on the AHRQ Patient Safety Indicator (PSI) 12 and expanded to include HA‐VTE rates for all hospitalized patients. We also report performance on Core Measure VTE‐6: incidence of potentially preventable VTE.

Process

We monitor VTE prophylaxis compliance based on the CMS Core Measures VTE‐1 and 2, random samples of acute and critical care patients without VTE. Internally, we measure compliance with guideline‐directed therapy for all HA‐VTE cases reviewed by the task force. With the upcoming retirement of the CMS chart‐abstracted measures, we are developing methods to track appropriate VTE prophylaxis provided to all eligible patients and will replace the sampled populations with this more expansive dataset. This approach will provide information for further improvements in VTE prophylaxis and act as an important step for success with the Electronic Clinical Quality Measures under the Meaningful Use program.

RESULTS

Our VTE prevention initiatives have resulted in improved compliance with our institutional guideline‐directed VTE prophylaxis and a decrease in HA‐VTE at our institution.

VTE Core Measures

Since the inception of VTE Core Measures in 2013, our annual performance on VTE‐1: prophylaxis for acute care patients has been above 95% and VTE‐2: prophylaxis for critical care patients has been above 98%. This performance has been consistently above the national mean for both measures (VTE‐1: 91% among Washington state hospitals and 93% nationally; VTE‐2: 95% among Washington state hospitals and 97% nationally). The CMS Hospital Compare current public reporting period is based on information collected from July 2014 through June 2015. Our internal performance for calendar year 2015 was 96% (289 of 302) for VTE‐1 and 98% (235 of 241) for VTE‐2.

Harborview has had zero potentially preventable VTE events (VTE‐6) compared with a reported national average of 4% since the inception of these measures in January 2013.

Guideline‐Directed VTE Prevention: Patients Diagnosed With HA‐VTE

The task force reviews each case to determine if the patient received guideline‐adherent prophylaxis on every day prior to the event. Patients with active bleeding or those with high bleeding risk should have mechanical prophylaxis ordered and applied until pharmacologic prophylaxis is appropriate. Any missed single dose of pharmacologic prophylaxis or missed day of applied mechanical prophylaxis is considered a possible opportunity for improvement, and the case is referred to the appropriate clinical service for additional review.

Since task force launch, the percent of all patients diagnosed with HA‐VTE who received guideline‐directed prophylaxis increased 7% from 86% (105 of 122) in 2012 to 92% (80 of 87) in the first 9 months of 2015. Of events with possible opportunities, most were deemed not to have been preventable. Some trauma patients were ineligible for pharmacologic and mechanical prophylaxis, some were prophylaxed according to the best available evidence, and some had risk factors (for example, active malignancy) only identified after the VTE event. The few remaining events highlighted opportunities regarding standardization of pharmacologic prophylaxis periprocedurally, documentation of application of mechanical prophylaxis, and communication of patient refusal of doses, all ongoing focus areas for improvement.

Reduction in HA‐VTE

Improved VTE prophylaxis has contributed to a 15% reduction in HA‐VTE in all hospitalized patients over 5 years from a rate of 7.5 events/1000 inpatients in 2011 to 6.4/1000 inpatients for the first 9 months of 2015. Among postoperative patients (AHRQ PSI 12), the rate of VTE decreased 21% from 11.7/1000 patients in 2011 to 9.3/1000 patients in the first 9 months of 2015.

Patient/Family Engagement

We further improved our processes to ensure that patients with HA‐VTE who discharge to home receive written discharge instructions for warfarin use (VTE‐5). In 2014, performance on this measure was 91% (51 of 56 eligible patients) and in 2015 performance improved to 96% (78 of 81 eligible patients) compared with a reported national average of 91%. Additionally, 97% (79 of 81) of patients who discharged home on warfarin after HA‐VTE now have outpatient anticoagulation follow‐up arranged prior to hospital discharge. We are developing new initiatives for patient and family education regarding direct oral anticoagulants.

Discussion/Conclusions

With interdisciplinary teamwork and use of QI analytics to drive transparency, we have improved VTE prevention and reduced rates of HA‐VTE. Harborview's HA‐VTE prevention initiative can be duplicated by other organizations given the structured nature of the intervention. The multidisciplinary approach, clinical presence of task force members, and support and engagement of senior clinical leadership have been key elements to our program's success. The existence of a standard institutional guideline based on evidence‐based national guidelines and incorporation of these standards into the EHR is vital. The VTE task force has consistently used QI analytics both for retrospective review and real‐time data feedback. Complete and easy accessibility and transparency of performance at the service and unit level supports accountability. Integration of the task force work into existing institutional QI structures has further led to improvements in patient safety.

Ongoing task force collaboration and communication with frontline providers and clinical departments has been critical to engagement and sustained improvements in VTE prevention and treatment. The work of the VTE task force represents the steadfast commitment of Harborview and our clinical staff to prevent preventable harm. This multidisciplinary effort has served as a model for other QI initiatives across our institution and health system.

Disclosure

Nothing to report.

- , , , et al. Executive Summary: Antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence‐based Clinical Guidelines. Chest. 2012;141(2 suppl):7S–47S.

- , , , . Venous thromboembolism: a public health concern. Am J Prev Med. 2010;38(4 suppl):S495–S501.

- , , , et al. Prevention of VTE in orthopedic surgery patients. Antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence‐based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest. 2012;141(2 suppl):e278S–e325S.

- , , , et al. Prevention of VTE in nonsurgical patients. Antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence‐based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest. 2012;141(2 suppl):e195S–e226S.

- , , , et al; American College of Chest Physicians. Prevention of VTE in nonorthopedic surgical patients. Antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence‐Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest. 2012;141(2 suppl):e227S–e277S.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Core measures. Available at: https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality‐Initiatives‐Patient‐Assessment‐Instruments/QualityMeasures/Core‐Measures.html. Accessed September 1, 2016.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Venous thromboembolism. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/dvt/index.html. Accessed September 1, 2016.

- . Preventing hospital‐associated venous thromboembolism: a guide for effective quality improvement, 2nd ed. AHRQ Publication No. 16‐0001‐EF. Rockville MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2016.

- . Preventing hospital‐associated venous thromboembolism: a guide for effective quality improvement. Available at: http://www.ahrq.gov/professionals/quality‐patient‐safety/patient‐safety‐resources/resources/vtguide/index.html. Accessed September 1, 2016.

- , . Preventing hospital‐acquired venous‐thromboembolism, a guide for effective quality improvement. Version 3.3. Venous Thromboembolism Quality Improvement Implementation Toolkit. Society of Hospital Medicine website. Available at: http://www.hospitalmedicine.org. Accessed September 1, 2016.

- , , , , . Adherence to guideline‐directed venous thromboembolism prophylaxis among medical and surgical inpatients at 33 academic medical centers in the United States. Am J Med Qual. 2010;26(3):174–180.

- UW Medicine guidelines for prevention of venous thromboembolism (VTE) in hospitalized patients. Available at: https://depts.washington.edu/anticoag/home. Accessed June 13, 2016.

- , , , , , . Upper extremity deep vein thrombosis in hospitalized patients: a descriptive study. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(1):48–53.

- , , , et al. Executive Summary: Antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence‐based Clinical Guidelines. Chest. 2012;141(2 suppl):7S–47S.

- , , , . Venous thromboembolism: a public health concern. Am J Prev Med. 2010;38(4 suppl):S495–S501.

- , , , et al. Prevention of VTE in orthopedic surgery patients. Antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence‐based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest. 2012;141(2 suppl):e278S–e325S.

- , , , et al. Prevention of VTE in nonsurgical patients. Antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence‐based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest. 2012;141(2 suppl):e195S–e226S.

- , , , et al; American College of Chest Physicians. Prevention of VTE in nonorthopedic surgical patients. Antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence‐Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest. 2012;141(2 suppl):e227S–e277S.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Core measures. Available at: https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality‐Initiatives‐Patient‐Assessment‐Instruments/QualityMeasures/Core‐Measures.html. Accessed September 1, 2016.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Venous thromboembolism. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/dvt/index.html. Accessed September 1, 2016.

- . Preventing hospital‐associated venous thromboembolism: a guide for effective quality improvement, 2nd ed. AHRQ Publication No. 16‐0001‐EF. Rockville MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2016.

- . Preventing hospital‐associated venous thromboembolism: a guide for effective quality improvement. Available at: http://www.ahrq.gov/professionals/quality‐patient‐safety/patient‐safety‐resources/resources/vtguide/index.html. Accessed September 1, 2016.

- , . Preventing hospital‐acquired venous‐thromboembolism, a guide for effective quality improvement. Version 3.3. Venous Thromboembolism Quality Improvement Implementation Toolkit. Society of Hospital Medicine website. Available at: http://www.hospitalmedicine.org. Accessed September 1, 2016.

- , , , , . Adherence to guideline‐directed venous thromboembolism prophylaxis among medical and surgical inpatients at 33 academic medical centers in the United States. Am J Med Qual. 2010;26(3):174–180.

- UW Medicine guidelines for prevention of venous thromboembolism (VTE) in hospitalized patients. Available at: https://depts.washington.edu/anticoag/home. Accessed June 13, 2016.

- , , , , , . Upper extremity deep vein thrombosis in hospitalized patients: a descriptive study. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(1):48–53.

© 2016 Society of Hospital Medicine

End‐of‐Life Discussions

Most patients prefer to die at home, pain free and without the use of life‐sustaining treatments[1, 2] yet the majority of patients with serious illness die in the hospital.[3, 4, 5] When hospitalized patient die, the care is frequently focused on life‐sustaining treatments[6]; pain, dyspnea, and agitation levels are higher when compared with patients who die in non‐hospital settings.[7, 8, 9] End‐of‐life discussions and their products (ie, advanced directives) can clarify treatment options with patients and family,[10] and help ensure that patients receive care consistent with their beliefs.[11, 12, 13] End‐of‐life discussions are associated with a decrease use of life‐sustaining treatments, improved quality of life, and reduced costs of care.[14, 15] For the majority of patients dying of cancer, the first end‐of‐life discussion takes place in the hospital setting.[16]

Conducting end‐of‐life conversations in the hospital setting can be challenging. Patients are acutely ill and nearly 40% are incapable of making their own medical decisions.[17] In order to participate in an end‐of‐life discussion, a physician must determine that a patient meets the 4 criteria of decisional capacity as outlined by Appelbaum and Grisso:[18] Does the patient (1) communicate a clear and consistent choice; (2) understand the relevant information surrounding that decision; (3) appreciate the consequences of that decision; and (4) communicate reasoning for that decision?[19] In practice, however, clinicians inaccurately assign capacity up to 25% of the time.[17] When a physician determines, accurately or inaccurately, that the patient does not meet this standard for decisional capacity, discussions must be held instead with a surrogate decision‐maker. Surrogate decision‐making can make communication with the physician more difficult,[20] delay important medical decisions,[21] and be stressful on the decision‐maker.[22] To our knowledge, no studies have examined patient and surrogate participation in end‐of‐life discussions at the time of terminal hospitalization and its association with end‐of‐life treatments received.

Our goals were to examine physician assessment of decisional capacity and the prevalence of end‐of‐life discussions during the terminal hospitalization of patients with advanced cancer. Our research questions were: (1) What proportion of patients were assessed to have decisional capacity by the clinical team at the time of their terminal hospital admission? (2) What proportion of these patients had a documented discussion about end‐of‐life care with the clinical team, and for what proportion was the conversation held instead by the patient's surrogate decision‐maker because the patient was considered to have lost decisional capacity? (3) Was patient participation in a discussion about end‐of‐life care associated with life‐sustaining and palliative treatments received?

METHODS

Design

This is a retrospective cohort study of consecutive adult patients with advanced cancer who died at the University of Michigan Hospital, Ann Arbor, MI, from January 1, 2004 through December 31, 2007. This study was exempted from review by the University of Michigan (UM) Institutional Review Board because decedent data were used.

Sample

The UM Cancer Registry is a database of all cancer patients treated at the UM Comprehensive Cancer Center. We used the Registry to identify patients who met the following criteria: (1) age 18 years at time of cancer diagnosis; (2) estimated probability of 5‐year survival 20% at time of diagnosis, as predicted by the SEER Cancer Statistics Review[23]; (3) the entirety of cancer treatment was received at University of Michigan Health System (UMHS); and (4) the patient died while admitted to the University Hospital between January 1, 2004 and December 31, 2007.

UMHS is a healthcare system and academic medical center consisting of hospitals, health centers, and clinics, including the University of Michigan Hospital and Comprehensive Cancer Center. Over 4000 cancer patients are admitted to University Hospital and 80,000 outpatient visits occur to the Cancer Center every year. It serves as a major cancer referral center for the patients of Michigan and the greater Midwest. The University of Michigan implemented a palliative care consult service that was started in 2005, during the time period of our study.

Data Collection

Data were abstracted by review of the medical record by an internist (M.Z.) using a comprehensive chart abstraction instrument based on a previously validated tool.[24] Demographic data abstracted from the medical record included age, religious affiliation, race, ethnicity, and marital status. The original abstraction tool, which included 83 items, was reduced to include 47 items focusing on information related to advanced care planning, hospital course, and end‐of‐life discussions. Specific items included: reasons for admission, primary hospital service, occurrence and timing of end‐of‐life decision‐making, whether patient or family preferences were elicited through an end‐of‐life discussion, clinician's assessment of patient's decisional capacity at time of admission and end‐of‐life conversations, whether a comfort care plan was made, and whether palliative morphine was used.

The chart abstraction tool was pilot tested on the medical records of 10 patients, who were not included in the study, and refined to improve completeness of data collection. A copy of the abstraction tool is available upon request.

Definition of Key Variables

Decisional Capacity Assessment

Decisional capacity assessment is a reflection of the clinical team's assessment of the patient's decisional capacity on admission, and was determined through examination of the medical record in the first 24 hours of admission. Positive decision‐making capacity assessment was assumed if the clinician assessment of decisional capacity was documented in the mental status exam, or if the clinician documented conversations between clinician and patient in the history that suggested intact decision‐making capacity (ie, clinician documented terms such as patient stated or patient described and then described a coherent or sensible statement which implied patient capacity and intact mental status), or if the clinician's documentation of the assessment and plan stated or suggested decisions were being made by the patient. Other supportive information from the record was used to corroborate the evidence used to determine the clinician's assessment of the patient's decisional capacity, including whether the patient signed consent forms.

End‐of‐Life Discussions

The presence of an end‐of‐life discussion was presumed when the clinician documented a discussion with the patient, discussion with family, or family meeting concerning treatment preferences, or when the clinician quoted the patient's preferences in a fashion that documents a face‐to‐face discussion or directly described the elicitation of preferences from the patient or family.

Living Will

A living will was identified as present if the document was scanned into the patient's medical record, or if the chart indicated that the patient or family stated that the patient had completed a living will.

Health Care Proxy

Health Care Proxy or Durable Power of Attorney for Healthcare was identified as present if the document was scanned into the patient's medical record, or if the chart indicated that the patient or family stated that the patient had completed such a document.

Do Not Resuscitate (DNR) on Admission

DNR status was identified as present if the patient had documents with established DNR orders, or if a physician explicitly documented code status as DNR in the admission note or other documents placed in the record within the first 24 hours of admission.

Intensive Care Unit (ICU)Treatment

Patients were defined as having received ICU treatment if they were admitted directly or subsequently transferred to the ICU during the hospital course.

Comfort Care

Comfort care was defined as present only if the phrases comfort care, palliative care, or supportive care, were documented.

Palliative Opioid Therapy

Treatments with morphine or other opioids were recorded as palliative only if it was explicitly stated that these medications were used in the context of palliative or end‐of‐life care.

Data Analysis

We report the proportion of patients who were documented to lack decisional capacity at the time of hospital admission. We compared patient characteristics for those with and without documentation of decisional capacity on admission, and patients with decisional capacity on admission who did and did not participate in discussions about end‐of‐life care using chi‐square tests for categorical data, t tests for normally distributed continuous variables, and MannWhitney U tests for non‐normally distributed continuous variables. We examined whether documentation of a discussion about end‐of‐life care was associated with life‐sustaining and palliative treatments received using chi‐square for categorical treatments, and MannWhitney U tests for days from admission to initiation of comfort care. We used P < 0.05 to signify statistical significance.

RESULTS

Characteristics of Population and Decisional Capacity on Admission

The characteristics of the 145 patients who met entry criteria are summarized in Table 1. The most common types of cancers were lung cancer and leukemia/lymphoma. Of the 145 patients, the medical team's assessment of the patient's decisional capacity on admission could be established for 142 patients. As documented within the first 24 hours of admission, 27 patients (19%) were considered not to have decisional capacity, and 115 patients (79%) were considered to have decisional capacity. Both of these groups had similar age and gender distributions. There were no significant differences in the distribution of cancer type between those with and without decisional capacity. In both groups, the majority of the cancer diagnoses were made prior to admission. There was no difference in DNR orders established prior to or on admission between the groups (Table 1).

| Decision‐Making Capacity on Admissiona | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| No (N = 27) | Yes (N = 115) | ||

| N (%) | N (%) | P Value | |

| |||

| Age >65 | 15 (55.6) | 60 (52.2) | 0.75 |

| Gender (male) | 14 (51.9) | 68 (59.1) | 0.46 |

| Cancer type | |||

| Lung | 12 (44.4) | 42 (36.5) | 0.67 |

| Bone marrow | 5 (18.5) | 35 (30.4) | |

| Liver | 3 (11.1) | 6 (5.2) | |

| Pancreas | 3 (11.1) | 7 (6.10) | |

| Esophagus | 1 (3.7) | 8 (7.0) | |

| Colon | 1 (3.7) | 6 (5.2) | |

| Otherb | 2 (7.4) | 11 (9.6) | |

| Prior to admission | |||

| Cancer diagnosis known | 23 (85.2) | 91 (79.1) | 0.48 |

| Living will completed | 6 (22.2) | 26 (22.6 | 0.97 |

| Health care proxy established | 3 (11.1) | 26 (22.6) | 0.18 |

| DNR established | 8 (29.6) | 27 (23.5) | 0.79 |

End‐of‐Life Discussion in Patients With Decisional Capacity on Admission

Of the 115 patients assessed to have intact decisional capacity on admission, 56 (48.7%) participated in an end‐of‐life discussion with the medical team during their terminal hospitalization. For the remaining 59 patients who did not participate in an end‐of‐life discussion during the terminal hospital course, 46 (40.0%) had documentation suggesting they lost decisional capacity prior to a conversation and that the end‐of‐life discussions were held instead with the patient's surrogate decision‐maker, and 13 (11.3%) had no evidence of any end‐of‐life discussion (with the patient or surrogate).

When comparing those patients who participated in an end‐of‐life discussion with those patients whose surrogate participated in the discussion, there were no significant differences in gender and age distributions (Table 2). There was a significant difference in the type of cancers between the 2 groups. Among patients who participated in their end‐of‐life discussions, bone marrow cancer was proportionately more prevalent (17.9% vs 2.2%; P <0.01) and lung cancer was less prevalent (16.1% vs 41.3%; P <0.01), when compared to those who required surrogate participation. Timing of cancer diagnosis and prevalence of advance directives were similar between the 2 groups. The proportion of patients who had an established DNR order prior to admission was higher among those who did participate in end‐of‐life discussions when compared to those who had surrogate participation in these discussions (30.4% vs 17.4%; P < 0.04).

| Patients With Documented Decision‐Making Capacity on Admission (N = 115) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N =13 | N = 102 | |||

| End‐of‐Life discussion not documented | End‐of‐Life discussion with surrogate (N = 46) | End‐of‐Life discussion with patient (N = 56) | ||

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | P Value | |

| ||||

| Age 65 | 9 (69.2) | 18 (39.1) | 27 (48.2) | 0.36 |

| Gender (male) | 10 (76.9) | 27 (60.0) | 31 (55.4) | 0.64 |

| Cancer type | ||||

| Lung | 3 (23.1) | 19 (41.3) | 9 (16.1) | |

| Bone marrow | 7 (53.9) | 1 (2.2) | 10 (17.9) | |

| Liver | 1 (7.7) | 3 (6.5) | 2 (3.6) | |

| Pancreas | 1 (7.7) | 2 (4.4) | 4 (7.1) | <0.01 |

| Esophagus | 0 | 6 (13.0) | 2 (3.6) | |

| Colon | 1 (7.7) | 1 (2.2) | 3 (5.4) | |

| Othera | 0 | 1 (2.2) | 10 (17.9) | |

| Prior to Admission | ||||

| Cancer diagnosis known | 10 (76.9) | 37 (80.4) | 43 (76.8) | 0.66 |

| Living will completed | 4 (30.8) | 10 (21.7) | 12 (21.4) | 0.97 |

| Health care proxy established | ||||

| 3 (23.1) | 13 (28.3) | 10 (17.9) | 0.21 | |

| DNR established | 2 (15.4) | 8 (17.4) | 17 (30.4) | 0.04 |

Life‐Prolonging and Palliative Care Treatments Received and Participation in End‐of‐Life Discussions

Life‐prolonging treatments were more likely to be used for patients whose end‐of‐life discussions were held by patient's surrogate decision‐maker, in comparison to those patients who participated in the discussions themselves. Patients who had conversations held by surrogates were more likely to receive ventilator support (56.5% vs 23.2%, P < 0.01), chemotherapy (39.1% vs 5.4%, P < 0.01), artificial nutrition or hydration (45.7% vs 25.0%, P = 0.03), and antibiotics (97.8% vs 78.6%, P < 0.01), when compared to patients who participated in their own end‐of‐life discussion. Intensive care treatment rates also differed significantly between the 2 groups; 56.5% of those who did not participate in end‐of‐life discussions, and only 23.2% of those patients who did participate, were admitted or transferred to the intensive care unit (P < 0.01). There was no significant difference in the proportion of patients who received cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) (15.2% vs 7.1%, P = 0.56) (Table 3). Patients who lost decisional capacity and required a surrogate decision‐maker to participate in their end‐of‐life discussions had longer length of stay (15.8 vs 10.3 days, P = 0.03) and length of time to end‐of‐life discussions (14.0 vs 6.1 days, P < 0.01) (Table 3).

| Patients With Documented Decision‐Making Capacity on Admission (N = 115) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| End‐of‐Life Discussion With Surrogate (N =46) | End‐of‐Life Discussion With Patient (N = 56) | ||

| N (%) | N (%) | P Value | |

| |||

| Life‐Prolonging Treatment | |||

| Ventilatory support | 26 (56.5) | 13 (23.2) | <0.01 |

| Chemotherapy | 18 (39.1) | 3 (5.4) | <0.01 |

| Artificial nutrition or hydration | 21 (45.7) | 14 (25.0) | 0.03 |

| Antibiotics | 45 (97.8) | 44 (78.6) | <0.01 |

| Cardiopulmonary resuscitation | 7 (15.2) | 4 (7.1) | 0.19 |

| ICU treatment (admit or transfer) | 26 (56.5) | 13 (23.2) | <0.01 |

| Palliative Treatments | |||

| Comfort care | 39 (84.8) | 45 (80.4) | 0.56 |

| Palliative morphine drip | 24 (52.2) | 33 (57.1) | 0.62 |

| Mean (95% CI) [Range] | Mean (95% CI) [Range] | ||

| Timing of Advanced Care Planning | |||

| Length of hospitalization | 15.8 d (11.420.2) [157] | 10.3 d (146) [146] | 0.03 |

| Time to end‐of‐life discussion | 14.0 d (9.918.1) [055] | 6.1 d (3.88.4) [046] | <0.01 |

| Time to comfort care | 23.5 d (4.342.8) [1374] | 9.2 d (6.312.1) [046] | 0.12 |

A comparison of the proportion of patients receiving palliative treatments, such as palliative comfort care orders and morphine infusions, revealed no significant differences between those with and without a discussion about end‐of‐life care (Table 3). Furthermore, while the time interval from hospital admission to initiation of comfort care was shorter for those who did participate in end‐of‐life discussions compared with those had surrogate participation (9.3 vs 23.5 days, P = 0.13 for equality), this difference was not statistically significant (Table 3).

Since a higher proportion of those who participated in end‐of‐life discussions during the hospitalization were admitted with a DNR order established prior to or on admission, we also examined the use of life‐prolonging treatments in the subgroup of patients who did not have a DNR order prior to admission. The difference in life‐prolonging treatments between those who did and did not participate in end‐of‐life discussions was preserved among those patients who did not have DNR status on admission (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

In this retrospective study of 145 terminal cancer patients who died in the hospital, we found that half of the patients had documentation suggesting that they lost decisional capacity during hospitalization and did not participate in end‐of‐life discussion with their healthcare providers. Among cancer patients in our study, 19% were determined not to have decisional capacity on admission, and another 32% were determined to lose decisional capacity during the hospital course. When patients did participate in documented discussions about end‐of‐life care, they were less likely to receive intensive life‐sustaining treatments, less likely to be admitted or transferred to the ICU, and more likely to avoid prolonged hospitalization. The finding that the majority of cancer patients are assessed to have intact decisional capacity upon admission to their terminal hospitalization, but less than half of them participate in their own end‐of‐life conversation, suggests that there is an important lost opportunity to provide quality advanced care planning to hospitalized patients.

Advanced care planning is the act of defining a competent patient's wishes regarding their future healthcare in the event of loss of decisional capacity. For many of the patients who were determined to lose decisional capacity during their hospitalization in our study, a surrogate decision‐maker was involved in a subsequent end‐of‐life discussion. This represents a missed opportunity in 2 ways. First, because surrogates may incorrectly predict patients' end‐of‐life treatment preferences in approximately one‐third of the cases,[25] patients may receive care that is inconsistent with their beliefs. Second, reliance on surrogate decision‐making may result in a greater burden on family members. Surrogate decision‐making places a large burden on surrogates, and can lead to emotional and psychological stress that can last well beyond the death of the loved one.[16, 26]

Our results reinforce the growing body of evidence suggesting that communication with the dying patient, both before and during the terminal hospitalization, promotes end‐of‐life care that involves less invasive life‐prolonging treatments,[10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15] which is a consistently stated goal of most patients at the end of life.[1, 2] Our findings are consistent with a recent randomized trial of hospitalized patients over the age of 80 which showed that advance care planning discussions were associated with decreased use of intensive life‐sustaining treatments, increased patient and family satisfaction with care, as well as decreased psychological symptoms among family members.[27] In addition, studies examining patients with advanced cancer have shown that discussions about end‐of‐life care in the outpatient setting resulted in less intensive life‐sustaining treatments.[14, 15] Nearly 20% of our cohort was determined by the clinical team to lack decisional capacity at the time of their terminal hospitalization, highlighting the importance of end‐of‐life discussion prior to hospitalization. Our results also extend these recent findings to the inpatient setting. Seventy‐nine percent of patients in our study were determined to have decisional capacity at the time of their terminal hospitalization, and end‐of‐life discussion conducted with these patients was associated with decreased use of life‐sustaining treatments.

Seriously ill patients, particularly in hospital settings, have high symptom burden and subsequent poor quality of life.[6] These patients and families often report inadequate pain and symptom relief.[8, 28, 29] It is therefore reassuring that we found no difference in the proportion of patients who received comfort care and palliative morphine infusions according to whether they or a surrogate participated in the end‐of‐life discussions. In fact, the majority of patients were made DNR and received some form of comfort measure prior to death, although these comfort measures were frequently initiated only hours prior to death.

While our findings are consistent with research that has demonstrated that end‐of‐life discussions with patients are associated with a decrease in life‐prolonging treatments, it is important to note that our observational study cannot establish a causal relationship between the end‐of‐life discussion and the subsequent use of life‐sustaining treatments. It is possible that patients who have discussions about end‐of‐life care inherently prefer to have less intensive life‐sustaining treatment at the end of life. Physicians may be more apt to engage in these types of discussions with patients who express interest in limited intervention. Interestingly, patients with a DNR order at the time of admission were more likely to participate in end‐of‐life care with their provider during their terminal hospitalization, which supports this alternate explanation. However, when we excluded all patients with a DNR on admission, our findings persisted. Regardless of the explanation for the association between end‐of‐life discussions and life‐sustaining treatments, our study identifies a cohort of hospitalized patients who could benefit from improved end‐of‐life communication, and a clinical setting where opportunities remain to improve the quality of advanced care planning.

Discussions about end‐of‐life care with patients result in earlier transition to care focused on palliation.[14] Although we examined the timing to initiation of comfort care between those who participated and those who did not participate in end‐of‐life discussions, we were not able to demonstrate a statistically significant difference. However, our cohort may not be suitable for an examination of this type of intervention, as early discussions about end‐of‐life care may have lead to early referral to hospice, and therefore death outside the hospital setting, making the patients ineligible for our study.