User login

My Most Unusual Case: Painful Blistering on the Dorsal Hands

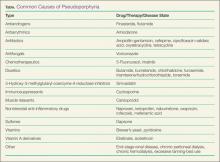

Patients with pseudoporphyria, an uncommon blistering skin disease, may initially present in the ED as the onset of this photosensitive condition can be acute—inciting patients to seek care urgently. The causes of pseudoporphyria may be drug-induced or related to hemodialysis, and it can develop even months to years after a patient with end-stage renal disease (ESRD) has been undergoing hemodialysis.1 Alternatively, patients can develop the condition weeks to months after starting certain medications (eg, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs [NSAIDs], tyrosine kinase receptor inhibitors, hormonal contraceptives, diuretics, antiandrogens, 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme-A reductase inhibitors). Recent case reports associate finasteride, torsemide, and β-lactam antibiotics with pseudoporphyria.2,3

With the increasing number of older Americans, as well as approximately one-third of seniors taking more than 5 drugs, the incidence of drug-induced pseudoporphyria is likely to increase in the near future.4 Additionally, ESRD is more common in patients older than age 70 years,5 increasing the risk of hemodialysis-related pseudoporphyria in this population.

Case

A 58-year-old black man presented to the ED with an 8-month history of nail changes and painful blisters on the dorsal hands. He stated that he initially noticed these findings after doing yardwork. Regarding history, he further noted that he smokes 3 cigarette packs daily and receives hemodialysis three times weekly for ESRD secondary to polycystic kidney disease. His medications included simvastatin, omeprazole, minoxidil, calcium, and a vitamin B complex.

On physical examination, the patient was well-appearing and in no acute distress with stable vital signs. His dermatologic examination revealed shallow, well-defined erosions, some with central crusting; and adjacent 1- to 2-mm scattered white papules on the dorsum of his hands bilaterally, with more appearing on his left hand than his right hand. The patient’s digits were tender to palpation, and symmetric tapering of the digits was present. Onycholysis and onychodystrophy were present in the majority of his nails.

The laboratory workup included a complete blood count and differential, which demonstrated a stable anemia of chronic disease when compared to prior labwork; a complete metabolic panel revealed expected elevated blood urea nitrogen and creatinine. Liver function and iron studies were normal.

Punch biopsies were performed on perilesional skin with direct immunofluorescence revealing linear granular deposits of immune complexes (IgG and C3), and direct microscopy noting fibrin at the dermoepidermal junction and perivascular location. These clinical and laboratory findings are consistent with porphyria cutanea tarda (PCT), pseudoporphyria, or variegate porphyria. However, his serum porphyrin studies were normal, thus supporting the diagnosis of pseudoporphyria.

Porphyria Cutanea Tarda

Porphyria cutanea tarda is the most common disorder of heme biosynthesis. In this condition, hepatic uroporphyrinogen decarboxylase is deficient, leading to the accumulation of porphyrins in the serum and blood.6 Patients typically present in adulthood complaining of painful blisters and milia on the dorsal hands, and usually do not recognize the component of sunlight exposure in the subsequent appearance of lesions.7 Genetic, environmental, and infectious etiologies contribute to its onset, acting singly or in concert.8-10 Up to half of patients with PCT are infected with hepatitis C; other associations include tobacco smoking, alcoholism, HIV infection, and hereditary hemochromatosis.10-12

As seen in this patient, no accumulation of photosensitive porphyrins is evident in pseudoporphyria through current laboratory testing. While the pathogenesis of pseudoporphyria is unknown, it may be linked to the generation of free radicals.

It is estimated that pseudoporphyria occurs in about 1.2% to 18% of patients undergoing hemodialysis treatment secondary to ESRD.13,14 Massone et al13 demonstrated that dialysis patients with ESRD are more susceptible to free-radical injury due to a reduction of the antioxidant glutathione in both plasma and erythrocytes. Additionally, ultraviolet (UV)-induced free radical formation in the skin has been well documented in the literature.15 This is further supported by a number of pseudoporphyria cases successfully treated with N-acetylcysteine, which replenishes glutathione. However, use of this medication in the treatment of pseudoporphyria is not common.

Treatment

Treatment of patients with pseudoporphyria requires a multifaceted approach. Removing the causative medication when possible may resolve the eruption. Unfortunately in our patient’s case, simvastatin, a possible cause of pseudoporphyria, was withdrawn for several months without improvement. This implicates hemodialysis as the probable cause of his pseudoporphyria. In a case of hemodialysis-induced pseudoporphyria, hemodialysis is life-saving and unable to be discontinued.

It is also important to counsel patients extensively on the importance of UV avoidance, including the use of photoprotective clothing, mineral-based sunscreen creams, and avoiding outside activity during peak daylight hours (ie, between 10:00 AM and 4:00 PM). A short course (2-4 weeks) of potent topical corticosteroids such as clobetasol 0.05% ointment can be prescribed for twice daily application to active lesions on the hands. Patients should also avoid any photosensitizing medications such as NSAIDs and tetracyclines.

Case Conclusion

On follow-up visits to the dermatology clinic, this patient continued to report improvement when compliant with the prescribed treatment plan, which included avoidance of direct sunlight, use of photoprotective clothing, and avoidance of photosensitizing medications, as well as daily use of clobetasol to lesions as needed. He noted skin flares with unprotected UV exposure.

Do you have an unusual case that you would like to share with your EM colleagues? Submissions should be cases that presented at and were managed within your ED. Please limit case reports to 1,000 words with a title of no more than 100 characters. Include a brief summary or unstructured abstract before you present the case details and include no more than two tables or figures, which should be submitted as separate, high-resolution files. Please de-identify all patient information. For full author guidelines please go to “author guidelines” at emed-journal.com. You can submit your case at editorialmanager.com/emedjournal or mdales@frontlinemedcom.com.

- Cordova KB, Oberg TJ, Malik M, Robinson-Bostom L. Dermatologic conditions seen in end-stage renal disease. Semin Dial. 2009;22(1):45-55.

- Santo Domingo D, Stevenson ML, Auerbach J, Lerman J. Finasteride-induced pseudoporphyria. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147(6):747-748.

- Pérez-Bustillo A, Sánchez-Sambucety P, Suárez-Amor O, Rodríiguez-Prieto MA. Torsemide-induced pseudoporphyria. Arch Dermatol. 2008;144(6):812-813.

- Scott IA, Gray LC, Martin JH, Mitchell CA. Minimizing inappropriate medications in older populations: a 10-step conceptual framework. Am J Med. 2012;125(6):529-537.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Chronic Kidney Disease Fact Sheet, 2014. http://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/pubs/pdf/kidney_Factsheet.pdf. Accessed October 24, 2014.

- Frank J, Poblete-Gutiérrez P. Porphyria cutanea tarda—when skin meets liver. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2010;24(5):735-745.

- Poh-Fitzpatrick MB. Porphyria cutanea tarda clinical presentation. Medscape Web site. http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1103643-clinical#a0216. Updated February 24, 2014. Accessed October 24, 2014.

- Egger NG, Goeger DE, Payne DA, Miskovsky EP, Weinman SA, Anderson KE. Porphyria cutanea tarda: multiplicity of risk factors including HFE mutations, hepatitis C, and inherited uroporphyrinogen decarboxylase deficiency. Dig Dis Sci. 2002;47(2):419-426.

- Cruz-Rojo J, Fontanellas A, Morán-Jiménez MJ. Precipitating/aggravating factors of porphyria cutanea tarda in Spanish patients. Cell Mol Biol (Noisy-le-grand). 2002;48(8):845-852.

- Jalil S, Grady JJ, Lee C, Anderson KE. Associations among behavior-related susceptibility factors in porphyria cutanea tarda. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;8(3):297-302.

- Elder GH. Alcohol intake and porphyria cutanea tarda. Clin Dermatol. 1999;17(4):431-436.

- Bonkovsky HL, Poh-Fitzpatrick M, Pimstone N, et al. Porphyria cutanea tarda, hepatitis C, and HFE gene mutations in North America. Hepatology. 1998;27(6):1661-1669.

- Massone C, Ambros-Rudolph CM, et al: Successful outcome of haemodialysis-induced pseudoporphyria after short-term oral N-acetylcysteine and switch to high-flux technique dialysis. Acta Derm Venereol. 2006;86(6):538-540.

- Cooke NS, McKenna K. A case of haemodialysis-associated pseudoporphyria successfully treated with oral N-acetylcysteine. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2007;32(1):64-66.

- Jurkiewicz BA, Buettner GR. Ultraviolet light-induced free radical formation in skin: an electron paramagnetic resonance study.

Patients with pseudoporphyria, an uncommon blistering skin disease, may initially present in the ED as the onset of this photosensitive condition can be acute—inciting patients to seek care urgently. The causes of pseudoporphyria may be drug-induced or related to hemodialysis, and it can develop even months to years after a patient with end-stage renal disease (ESRD) has been undergoing hemodialysis.1 Alternatively, patients can develop the condition weeks to months after starting certain medications (eg, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs [NSAIDs], tyrosine kinase receptor inhibitors, hormonal contraceptives, diuretics, antiandrogens, 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme-A reductase inhibitors). Recent case reports associate finasteride, torsemide, and β-lactam antibiotics with pseudoporphyria.2,3

With the increasing number of older Americans, as well as approximately one-third of seniors taking more than 5 drugs, the incidence of drug-induced pseudoporphyria is likely to increase in the near future.4 Additionally, ESRD is more common in patients older than age 70 years,5 increasing the risk of hemodialysis-related pseudoporphyria in this population.

Case

A 58-year-old black man presented to the ED with an 8-month history of nail changes and painful blisters on the dorsal hands. He stated that he initially noticed these findings after doing yardwork. Regarding history, he further noted that he smokes 3 cigarette packs daily and receives hemodialysis three times weekly for ESRD secondary to polycystic kidney disease. His medications included simvastatin, omeprazole, minoxidil, calcium, and a vitamin B complex.

On physical examination, the patient was well-appearing and in no acute distress with stable vital signs. His dermatologic examination revealed shallow, well-defined erosions, some with central crusting; and adjacent 1- to 2-mm scattered white papules on the dorsum of his hands bilaterally, with more appearing on his left hand than his right hand. The patient’s digits were tender to palpation, and symmetric tapering of the digits was present. Onycholysis and onychodystrophy were present in the majority of his nails.

The laboratory workup included a complete blood count and differential, which demonstrated a stable anemia of chronic disease when compared to prior labwork; a complete metabolic panel revealed expected elevated blood urea nitrogen and creatinine. Liver function and iron studies were normal.

Punch biopsies were performed on perilesional skin with direct immunofluorescence revealing linear granular deposits of immune complexes (IgG and C3), and direct microscopy noting fibrin at the dermoepidermal junction and perivascular location. These clinical and laboratory findings are consistent with porphyria cutanea tarda (PCT), pseudoporphyria, or variegate porphyria. However, his serum porphyrin studies were normal, thus supporting the diagnosis of pseudoporphyria.

Porphyria Cutanea Tarda

Porphyria cutanea tarda is the most common disorder of heme biosynthesis. In this condition, hepatic uroporphyrinogen decarboxylase is deficient, leading to the accumulation of porphyrins in the serum and blood.6 Patients typically present in adulthood complaining of painful blisters and milia on the dorsal hands, and usually do not recognize the component of sunlight exposure in the subsequent appearance of lesions.7 Genetic, environmental, and infectious etiologies contribute to its onset, acting singly or in concert.8-10 Up to half of patients with PCT are infected with hepatitis C; other associations include tobacco smoking, alcoholism, HIV infection, and hereditary hemochromatosis.10-12

As seen in this patient, no accumulation of photosensitive porphyrins is evident in pseudoporphyria through current laboratory testing. While the pathogenesis of pseudoporphyria is unknown, it may be linked to the generation of free radicals.

It is estimated that pseudoporphyria occurs in about 1.2% to 18% of patients undergoing hemodialysis treatment secondary to ESRD.13,14 Massone et al13 demonstrated that dialysis patients with ESRD are more susceptible to free-radical injury due to a reduction of the antioxidant glutathione in both plasma and erythrocytes. Additionally, ultraviolet (UV)-induced free radical formation in the skin has been well documented in the literature.15 This is further supported by a number of pseudoporphyria cases successfully treated with N-acetylcysteine, which replenishes glutathione. However, use of this medication in the treatment of pseudoporphyria is not common.

Treatment

Treatment of patients with pseudoporphyria requires a multifaceted approach. Removing the causative medication when possible may resolve the eruption. Unfortunately in our patient’s case, simvastatin, a possible cause of pseudoporphyria, was withdrawn for several months without improvement. This implicates hemodialysis as the probable cause of his pseudoporphyria. In a case of hemodialysis-induced pseudoporphyria, hemodialysis is life-saving and unable to be discontinued.

It is also important to counsel patients extensively on the importance of UV avoidance, including the use of photoprotective clothing, mineral-based sunscreen creams, and avoiding outside activity during peak daylight hours (ie, between 10:00 AM and 4:00 PM). A short course (2-4 weeks) of potent topical corticosteroids such as clobetasol 0.05% ointment can be prescribed for twice daily application to active lesions on the hands. Patients should also avoid any photosensitizing medications such as NSAIDs and tetracyclines.

Case Conclusion

On follow-up visits to the dermatology clinic, this patient continued to report improvement when compliant with the prescribed treatment plan, which included avoidance of direct sunlight, use of photoprotective clothing, and avoidance of photosensitizing medications, as well as daily use of clobetasol to lesions as needed. He noted skin flares with unprotected UV exposure.

Do you have an unusual case that you would like to share with your EM colleagues? Submissions should be cases that presented at and were managed within your ED. Please limit case reports to 1,000 words with a title of no more than 100 characters. Include a brief summary or unstructured abstract before you present the case details and include no more than two tables or figures, which should be submitted as separate, high-resolution files. Please de-identify all patient information. For full author guidelines please go to “author guidelines” at emed-journal.com. You can submit your case at editorialmanager.com/emedjournal or mdales@frontlinemedcom.com.

Patients with pseudoporphyria, an uncommon blistering skin disease, may initially present in the ED as the onset of this photosensitive condition can be acute—inciting patients to seek care urgently. The causes of pseudoporphyria may be drug-induced or related to hemodialysis, and it can develop even months to years after a patient with end-stage renal disease (ESRD) has been undergoing hemodialysis.1 Alternatively, patients can develop the condition weeks to months after starting certain medications (eg, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs [NSAIDs], tyrosine kinase receptor inhibitors, hormonal contraceptives, diuretics, antiandrogens, 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme-A reductase inhibitors). Recent case reports associate finasteride, torsemide, and β-lactam antibiotics with pseudoporphyria.2,3

With the increasing number of older Americans, as well as approximately one-third of seniors taking more than 5 drugs, the incidence of drug-induced pseudoporphyria is likely to increase in the near future.4 Additionally, ESRD is more common in patients older than age 70 years,5 increasing the risk of hemodialysis-related pseudoporphyria in this population.

Case

A 58-year-old black man presented to the ED with an 8-month history of nail changes and painful blisters on the dorsal hands. He stated that he initially noticed these findings after doing yardwork. Regarding history, he further noted that he smokes 3 cigarette packs daily and receives hemodialysis three times weekly for ESRD secondary to polycystic kidney disease. His medications included simvastatin, omeprazole, minoxidil, calcium, and a vitamin B complex.

On physical examination, the patient was well-appearing and in no acute distress with stable vital signs. His dermatologic examination revealed shallow, well-defined erosions, some with central crusting; and adjacent 1- to 2-mm scattered white papules on the dorsum of his hands bilaterally, with more appearing on his left hand than his right hand. The patient’s digits were tender to palpation, and symmetric tapering of the digits was present. Onycholysis and onychodystrophy were present in the majority of his nails.

The laboratory workup included a complete blood count and differential, which demonstrated a stable anemia of chronic disease when compared to prior labwork; a complete metabolic panel revealed expected elevated blood urea nitrogen and creatinine. Liver function and iron studies were normal.

Punch biopsies were performed on perilesional skin with direct immunofluorescence revealing linear granular deposits of immune complexes (IgG and C3), and direct microscopy noting fibrin at the dermoepidermal junction and perivascular location. These clinical and laboratory findings are consistent with porphyria cutanea tarda (PCT), pseudoporphyria, or variegate porphyria. However, his serum porphyrin studies were normal, thus supporting the diagnosis of pseudoporphyria.

Porphyria Cutanea Tarda

Porphyria cutanea tarda is the most common disorder of heme biosynthesis. In this condition, hepatic uroporphyrinogen decarboxylase is deficient, leading to the accumulation of porphyrins in the serum and blood.6 Patients typically present in adulthood complaining of painful blisters and milia on the dorsal hands, and usually do not recognize the component of sunlight exposure in the subsequent appearance of lesions.7 Genetic, environmental, and infectious etiologies contribute to its onset, acting singly or in concert.8-10 Up to half of patients with PCT are infected with hepatitis C; other associations include tobacco smoking, alcoholism, HIV infection, and hereditary hemochromatosis.10-12

As seen in this patient, no accumulation of photosensitive porphyrins is evident in pseudoporphyria through current laboratory testing. While the pathogenesis of pseudoporphyria is unknown, it may be linked to the generation of free radicals.

It is estimated that pseudoporphyria occurs in about 1.2% to 18% of patients undergoing hemodialysis treatment secondary to ESRD.13,14 Massone et al13 demonstrated that dialysis patients with ESRD are more susceptible to free-radical injury due to a reduction of the antioxidant glutathione in both plasma and erythrocytes. Additionally, ultraviolet (UV)-induced free radical formation in the skin has been well documented in the literature.15 This is further supported by a number of pseudoporphyria cases successfully treated with N-acetylcysteine, which replenishes glutathione. However, use of this medication in the treatment of pseudoporphyria is not common.

Treatment

Treatment of patients with pseudoporphyria requires a multifaceted approach. Removing the causative medication when possible may resolve the eruption. Unfortunately in our patient’s case, simvastatin, a possible cause of pseudoporphyria, was withdrawn for several months without improvement. This implicates hemodialysis as the probable cause of his pseudoporphyria. In a case of hemodialysis-induced pseudoporphyria, hemodialysis is life-saving and unable to be discontinued.

It is also important to counsel patients extensively on the importance of UV avoidance, including the use of photoprotective clothing, mineral-based sunscreen creams, and avoiding outside activity during peak daylight hours (ie, between 10:00 AM and 4:00 PM). A short course (2-4 weeks) of potent topical corticosteroids such as clobetasol 0.05% ointment can be prescribed for twice daily application to active lesions on the hands. Patients should also avoid any photosensitizing medications such as NSAIDs and tetracyclines.

Case Conclusion

On follow-up visits to the dermatology clinic, this patient continued to report improvement when compliant with the prescribed treatment plan, which included avoidance of direct sunlight, use of photoprotective clothing, and avoidance of photosensitizing medications, as well as daily use of clobetasol to lesions as needed. He noted skin flares with unprotected UV exposure.

Do you have an unusual case that you would like to share with your EM colleagues? Submissions should be cases that presented at and were managed within your ED. Please limit case reports to 1,000 words with a title of no more than 100 characters. Include a brief summary or unstructured abstract before you present the case details and include no more than two tables or figures, which should be submitted as separate, high-resolution files. Please de-identify all patient information. For full author guidelines please go to “author guidelines” at emed-journal.com. You can submit your case at editorialmanager.com/emedjournal or mdales@frontlinemedcom.com.

- Cordova KB, Oberg TJ, Malik M, Robinson-Bostom L. Dermatologic conditions seen in end-stage renal disease. Semin Dial. 2009;22(1):45-55.

- Santo Domingo D, Stevenson ML, Auerbach J, Lerman J. Finasteride-induced pseudoporphyria. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147(6):747-748.

- Pérez-Bustillo A, Sánchez-Sambucety P, Suárez-Amor O, Rodríiguez-Prieto MA. Torsemide-induced pseudoporphyria. Arch Dermatol. 2008;144(6):812-813.

- Scott IA, Gray LC, Martin JH, Mitchell CA. Minimizing inappropriate medications in older populations: a 10-step conceptual framework. Am J Med. 2012;125(6):529-537.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Chronic Kidney Disease Fact Sheet, 2014. http://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/pubs/pdf/kidney_Factsheet.pdf. Accessed October 24, 2014.

- Frank J, Poblete-Gutiérrez P. Porphyria cutanea tarda—when skin meets liver. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2010;24(5):735-745.

- Poh-Fitzpatrick MB. Porphyria cutanea tarda clinical presentation. Medscape Web site. http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1103643-clinical#a0216. Updated February 24, 2014. Accessed October 24, 2014.

- Egger NG, Goeger DE, Payne DA, Miskovsky EP, Weinman SA, Anderson KE. Porphyria cutanea tarda: multiplicity of risk factors including HFE mutations, hepatitis C, and inherited uroporphyrinogen decarboxylase deficiency. Dig Dis Sci. 2002;47(2):419-426.

- Cruz-Rojo J, Fontanellas A, Morán-Jiménez MJ. Precipitating/aggravating factors of porphyria cutanea tarda in Spanish patients. Cell Mol Biol (Noisy-le-grand). 2002;48(8):845-852.

- Jalil S, Grady JJ, Lee C, Anderson KE. Associations among behavior-related susceptibility factors in porphyria cutanea tarda. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;8(3):297-302.

- Elder GH. Alcohol intake and porphyria cutanea tarda. Clin Dermatol. 1999;17(4):431-436.

- Bonkovsky HL, Poh-Fitzpatrick M, Pimstone N, et al. Porphyria cutanea tarda, hepatitis C, and HFE gene mutations in North America. Hepatology. 1998;27(6):1661-1669.

- Massone C, Ambros-Rudolph CM, et al: Successful outcome of haemodialysis-induced pseudoporphyria after short-term oral N-acetylcysteine and switch to high-flux technique dialysis. Acta Derm Venereol. 2006;86(6):538-540.

- Cooke NS, McKenna K. A case of haemodialysis-associated pseudoporphyria successfully treated with oral N-acetylcysteine. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2007;32(1):64-66.

- Jurkiewicz BA, Buettner GR. Ultraviolet light-induced free radical formation in skin: an electron paramagnetic resonance study.

- Cordova KB, Oberg TJ, Malik M, Robinson-Bostom L. Dermatologic conditions seen in end-stage renal disease. Semin Dial. 2009;22(1):45-55.

- Santo Domingo D, Stevenson ML, Auerbach J, Lerman J. Finasteride-induced pseudoporphyria. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147(6):747-748.

- Pérez-Bustillo A, Sánchez-Sambucety P, Suárez-Amor O, Rodríiguez-Prieto MA. Torsemide-induced pseudoporphyria. Arch Dermatol. 2008;144(6):812-813.

- Scott IA, Gray LC, Martin JH, Mitchell CA. Minimizing inappropriate medications in older populations: a 10-step conceptual framework. Am J Med. 2012;125(6):529-537.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Chronic Kidney Disease Fact Sheet, 2014. http://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/pubs/pdf/kidney_Factsheet.pdf. Accessed October 24, 2014.

- Frank J, Poblete-Gutiérrez P. Porphyria cutanea tarda—when skin meets liver. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2010;24(5):735-745.

- Poh-Fitzpatrick MB. Porphyria cutanea tarda clinical presentation. Medscape Web site. http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1103643-clinical#a0216. Updated February 24, 2014. Accessed October 24, 2014.

- Egger NG, Goeger DE, Payne DA, Miskovsky EP, Weinman SA, Anderson KE. Porphyria cutanea tarda: multiplicity of risk factors including HFE mutations, hepatitis C, and inherited uroporphyrinogen decarboxylase deficiency. Dig Dis Sci. 2002;47(2):419-426.

- Cruz-Rojo J, Fontanellas A, Morán-Jiménez MJ. Precipitating/aggravating factors of porphyria cutanea tarda in Spanish patients. Cell Mol Biol (Noisy-le-grand). 2002;48(8):845-852.

- Jalil S, Grady JJ, Lee C, Anderson KE. Associations among behavior-related susceptibility factors in porphyria cutanea tarda. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;8(3):297-302.

- Elder GH. Alcohol intake and porphyria cutanea tarda. Clin Dermatol. 1999;17(4):431-436.

- Bonkovsky HL, Poh-Fitzpatrick M, Pimstone N, et al. Porphyria cutanea tarda, hepatitis C, and HFE gene mutations in North America. Hepatology. 1998;27(6):1661-1669.

- Massone C, Ambros-Rudolph CM, et al: Successful outcome of haemodialysis-induced pseudoporphyria after short-term oral N-acetylcysteine and switch to high-flux technique dialysis. Acta Derm Venereol. 2006;86(6):538-540.

- Cooke NS, McKenna K. A case of haemodialysis-associated pseudoporphyria successfully treated with oral N-acetylcysteine. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2007;32(1):64-66.

- Jurkiewicz BA, Buettner GR. Ultraviolet light-induced free radical formation in skin: an electron paramagnetic resonance study.