User login

IBS: Mental Health Factors and Comorbidities

IBS: Mental Health Factors and Comorbidities

Click to view more from Gastroenterology Data Trends 2025.

- Staudacher HM, Black CJ, Teasdale SB, Mikocka-Walus A, Keefer L. Irritable bowel syndrome and mental health comorbidity - approach to multidisciplinary management. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023;20(9):582-596. doi:10.1038/s41575-023-00794-z

- Ballou S, Vasant DH, Guadagnoli L, et al. A primer for the gastroenterology provider on psychosocial assessment of patients with disorders of gut-brain interaction. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2024;36(12):e14894. doi:10.1111/nmo.14894

- Keefer L, Ballou SK, Drossman DA, Ringstrom G, Elsenbruch S, Ljótsson B. A Rome Working Team Report on Brain-Gut Behavior Therapies for Disorders of Gut-Brain Interaction. Gastroenterology. 2022;162(1):300-315. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2021.09.015

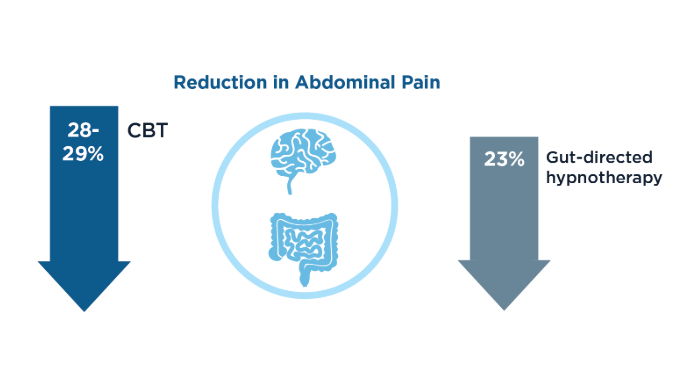

- Goodoory VC, Khasawneh M, Thakur ER, et al. Effect of Brain-Gut Behavioral Treatments on Abdominal Pain in Irritable Bowel Syndrome: Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis. Gastroenterology. 2024;167(5):934-943.e5. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2024.05.010

- Chang L, Sultan S, Lembo A, Verne GN, Smalley W, Heidelbaugh JJ. AGA Clinical Practice Guideline on the Pharmacological Management of Irritable Bowel Syndrome With Constipation. Gastroenterology. 2022;163(1):118-136. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2022.04.016

- Drossman DA, Tack J, Ford AC, Szigethy E, Törnblom H, Van Oudenhove L. Neuromodulators for Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders (Disorders of Gut-Brain Interaction): A Rome Foundation Working Team Report. Gastroenterology. 2018;154(4):1140-1171.e1. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2017.11.279

- Hasan SS, Ballou S, Keefer L, Vasant DH. Improving access to gut-directed hypnotherapy for irritable bowel syndrome in the digital therapeutics’ era: Are mobile applications a “smart” solution? Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2023;35(4):e14554. doi:10.1111/nmo.14554

- Tarar ZI, Farooq U, Zafar Y, et al. Burden of anxiety and depression among hospitalized patients with irritable bowel syndrome: a nationwide analysis. Ir J Med Sci. 2023;192(5):2159-2166. doi:10.1007/s11845-022-03258-6

- Barbara G, Aziz I, Ballou S, et al. Rome Foundation Working Team Report on overlap in disorders of gut-brain interaction. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. doi:10.1038/s41575-024-01033-9

- Thakur ER, Kunik M, Jarbrink-Sehgal ME, Lackner J, Dindo L, El-Serag H. Behavior Medicine Management of Irritable Bowel Syndrome: A Referral Toolkit for Gastroenterology Providers. 2018. Accessed February 19, 2025. https://www.mirecc.va.gov/VISN16/docs/ibs-referral-toolkit.pdf

- Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). Johns Hopkins Medicine website. Accessed February 19, 2025. https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/health/conditionsanddiseases/irritable-bowel-syndrome-ibs

- Burton-Murray H, Guadagnoli L, Kamp K, et al. Rome Foundation Working Team Report: Consensus Statement on the Design and Conduct of Behavioural Clinical Trials for Disorders of Gut-Brain Interaction. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2025;61(5):787-802. doi:10.1111/apt.18482

- Rome GastroPsych. Rome Foundation website. Accessed February 19, 2025. https://romegipsych.org/

- Scarlata K, Riehl M. Mind Your Gut: The Science-based, Whole-body Guide to Living Well with IBS. Hachette Book Group, 2025.

- IFFGD International Foundation for Gastrointestinal Disorders. IFFGD website. January 10, 2025. Accessed February 19, 2025. https://iffgd.org/

- GI Psychology: Mind Your Gut website. April 2, 2024. Accessed February 19, 2025. https://www.gipsychology.com/

- Drossman DA, Ruddy J. Gut Feelings: Disorders of the Gut-Brain Interaction (DGBI) and the Patient-Doctor Relationship. DrossmanCare Chapel Hill, 2020.

- Tuesday Night IBS website. Accessed February 19, 2025. https://www.tuesdaynightibs.com/

Click to view more from Gastroenterology Data Trends 2025.

Click to view more from Gastroenterology Data Trends 2025.

- Staudacher HM, Black CJ, Teasdale SB, Mikocka-Walus A, Keefer L. Irritable bowel syndrome and mental health comorbidity - approach to multidisciplinary management. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023;20(9):582-596. doi:10.1038/s41575-023-00794-z

- Ballou S, Vasant DH, Guadagnoli L, et al. A primer for the gastroenterology provider on psychosocial assessment of patients with disorders of gut-brain interaction. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2024;36(12):e14894. doi:10.1111/nmo.14894

- Keefer L, Ballou SK, Drossman DA, Ringstrom G, Elsenbruch S, Ljótsson B. A Rome Working Team Report on Brain-Gut Behavior Therapies for Disorders of Gut-Brain Interaction. Gastroenterology. 2022;162(1):300-315. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2021.09.015

- Goodoory VC, Khasawneh M, Thakur ER, et al. Effect of Brain-Gut Behavioral Treatments on Abdominal Pain in Irritable Bowel Syndrome: Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis. Gastroenterology. 2024;167(5):934-943.e5. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2024.05.010

- Chang L, Sultan S, Lembo A, Verne GN, Smalley W, Heidelbaugh JJ. AGA Clinical Practice Guideline on the Pharmacological Management of Irritable Bowel Syndrome With Constipation. Gastroenterology. 2022;163(1):118-136. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2022.04.016

- Drossman DA, Tack J, Ford AC, Szigethy E, Törnblom H, Van Oudenhove L. Neuromodulators for Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders (Disorders of Gut-Brain Interaction): A Rome Foundation Working Team Report. Gastroenterology. 2018;154(4):1140-1171.e1. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2017.11.279

- Hasan SS, Ballou S, Keefer L, Vasant DH. Improving access to gut-directed hypnotherapy for irritable bowel syndrome in the digital therapeutics’ era: Are mobile applications a “smart” solution? Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2023;35(4):e14554. doi:10.1111/nmo.14554

- Tarar ZI, Farooq U, Zafar Y, et al. Burden of anxiety and depression among hospitalized patients with irritable bowel syndrome: a nationwide analysis. Ir J Med Sci. 2023;192(5):2159-2166. doi:10.1007/s11845-022-03258-6

- Barbara G, Aziz I, Ballou S, et al. Rome Foundation Working Team Report on overlap in disorders of gut-brain interaction. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. doi:10.1038/s41575-024-01033-9

- Thakur ER, Kunik M, Jarbrink-Sehgal ME, Lackner J, Dindo L, El-Serag H. Behavior Medicine Management of Irritable Bowel Syndrome: A Referral Toolkit for Gastroenterology Providers. 2018. Accessed February 19, 2025. https://www.mirecc.va.gov/VISN16/docs/ibs-referral-toolkit.pdf

- Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). Johns Hopkins Medicine website. Accessed February 19, 2025. https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/health/conditionsanddiseases/irritable-bowel-syndrome-ibs

- Burton-Murray H, Guadagnoli L, Kamp K, et al. Rome Foundation Working Team Report: Consensus Statement on the Design and Conduct of Behavioural Clinical Trials for Disorders of Gut-Brain Interaction. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2025;61(5):787-802. doi:10.1111/apt.18482

- Rome GastroPsych. Rome Foundation website. Accessed February 19, 2025. https://romegipsych.org/

- Scarlata K, Riehl M. Mind Your Gut: The Science-based, Whole-body Guide to Living Well with IBS. Hachette Book Group, 2025.

- IFFGD International Foundation for Gastrointestinal Disorders. IFFGD website. January 10, 2025. Accessed February 19, 2025. https://iffgd.org/

- GI Psychology: Mind Your Gut website. April 2, 2024. Accessed February 19, 2025. https://www.gipsychology.com/

- Drossman DA, Ruddy J. Gut Feelings: Disorders of the Gut-Brain Interaction (DGBI) and the Patient-Doctor Relationship. DrossmanCare Chapel Hill, 2020.

- Tuesday Night IBS website. Accessed February 19, 2025. https://www.tuesdaynightibs.com/

- Staudacher HM, Black CJ, Teasdale SB, Mikocka-Walus A, Keefer L. Irritable bowel syndrome and mental health comorbidity - approach to multidisciplinary management. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023;20(9):582-596. doi:10.1038/s41575-023-00794-z

- Ballou S, Vasant DH, Guadagnoli L, et al. A primer for the gastroenterology provider on psychosocial assessment of patients with disorders of gut-brain interaction. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2024;36(12):e14894. doi:10.1111/nmo.14894

- Keefer L, Ballou SK, Drossman DA, Ringstrom G, Elsenbruch S, Ljótsson B. A Rome Working Team Report on Brain-Gut Behavior Therapies for Disorders of Gut-Brain Interaction. Gastroenterology. 2022;162(1):300-315. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2021.09.015

- Goodoory VC, Khasawneh M, Thakur ER, et al. Effect of Brain-Gut Behavioral Treatments on Abdominal Pain in Irritable Bowel Syndrome: Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis. Gastroenterology. 2024;167(5):934-943.e5. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2024.05.010

- Chang L, Sultan S, Lembo A, Verne GN, Smalley W, Heidelbaugh JJ. AGA Clinical Practice Guideline on the Pharmacological Management of Irritable Bowel Syndrome With Constipation. Gastroenterology. 2022;163(1):118-136. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2022.04.016

- Drossman DA, Tack J, Ford AC, Szigethy E, Törnblom H, Van Oudenhove L. Neuromodulators for Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders (Disorders of Gut-Brain Interaction): A Rome Foundation Working Team Report. Gastroenterology. 2018;154(4):1140-1171.e1. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2017.11.279

- Hasan SS, Ballou S, Keefer L, Vasant DH. Improving access to gut-directed hypnotherapy for irritable bowel syndrome in the digital therapeutics’ era: Are mobile applications a “smart” solution? Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2023;35(4):e14554. doi:10.1111/nmo.14554

- Tarar ZI, Farooq U, Zafar Y, et al. Burden of anxiety and depression among hospitalized patients with irritable bowel syndrome: a nationwide analysis. Ir J Med Sci. 2023;192(5):2159-2166. doi:10.1007/s11845-022-03258-6

- Barbara G, Aziz I, Ballou S, et al. Rome Foundation Working Team Report on overlap in disorders of gut-brain interaction. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. doi:10.1038/s41575-024-01033-9

- Thakur ER, Kunik M, Jarbrink-Sehgal ME, Lackner J, Dindo L, El-Serag H. Behavior Medicine Management of Irritable Bowel Syndrome: A Referral Toolkit for Gastroenterology Providers. 2018. Accessed February 19, 2025. https://www.mirecc.va.gov/VISN16/docs/ibs-referral-toolkit.pdf

- Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). Johns Hopkins Medicine website. Accessed February 19, 2025. https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/health/conditionsanddiseases/irritable-bowel-syndrome-ibs

- Burton-Murray H, Guadagnoli L, Kamp K, et al. Rome Foundation Working Team Report: Consensus Statement on the Design and Conduct of Behavioural Clinical Trials for Disorders of Gut-Brain Interaction. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2025;61(5):787-802. doi:10.1111/apt.18482

- Rome GastroPsych. Rome Foundation website. Accessed February 19, 2025. https://romegipsych.org/

- Scarlata K, Riehl M. Mind Your Gut: The Science-based, Whole-body Guide to Living Well with IBS. Hachette Book Group, 2025.

- IFFGD International Foundation for Gastrointestinal Disorders. IFFGD website. January 10, 2025. Accessed February 19, 2025. https://iffgd.org/

- GI Psychology: Mind Your Gut website. April 2, 2024. Accessed February 19, 2025. https://www.gipsychology.com/

- Drossman DA, Ruddy J. Gut Feelings: Disorders of the Gut-Brain Interaction (DGBI) and the Patient-Doctor Relationship. DrossmanCare Chapel Hill, 2020.

- Tuesday Night IBS website. Accessed February 19, 2025. https://www.tuesdaynightibs.com/

IBS: Mental Health Factors and Comorbidities

IBS: Mental Health Factors and Comorbidities

The differences between IBS-C and CIC

Lin Chang, MD, serves as the Co-Director of the G. Oppenheimer Center for Neurobiology of Stress and Resilience at UCLA. She is also Program Director of the UCLA Gastroenterology Fellowship Program. Dr. Chang’s expertise is in disorders of gut-brain interaction (also known as functional gastrointestinal disorders), particularly irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). She has recently served as the Clinical Research Councilor of the AGA Governing Board. She previously served as President of the American Neurogastroenterology and Motility Society (ANMS) and is a member of the Rome Foundation Board of Directors.

As a gastroenterologist focused on the pathophysiology of IBS related to stress, sex differences, and neuroendocrine alterations, and the treatment of IBS, Dr. Chang, what exactly is IBS-C and how is CIC defined differently?

Dr. Chang: IBS-C is irritable bowel syndrome with predominantly constipation which is a type of IBS. IBS is a symptom-based diagnosis for a chronic or recurrent gastrointestinal condition where patients have abdominal pain that's associated with constipation, diarrhea, or both. IBS is subtyped by bowel habit predominance into IBS with constipation, IBS with diarrhea, and IBS with mixed bowel habits. With IBS-mixed, one of the subgroups of IBS, they have diarrhea as well as constipation.

Patients will present with abdominal pain for usually one day, a week or even more. Sometimes, a little less. But when they have pain, it's associated with a change in stool frequency, a change in stool form, and/or the pain is related to defecation, meaning that when a patient has a bowel movement, they'll either have more pain or they'll have some pain relief, which is more common.

Now, CIC is Chronic Idiopathic Constipation and that's the term used for chronic constipation where abdominal pain is not a predominant symptom. The main difference between IBS-C and CIC is that abdominal pain is not a predominant or frequent symptom.

Patients with CIC can occasionally get abdominal pain, particularly if they haven't had a bowel movement for a prolonged period of time. However, in patients with IBS-C, they can have some normalization of their bowel habits or their constipation with treatment, although they can still have abdominal pain and discomfort. So, these patients have an element of visceral hypersensitivity where the gut is more sensitive than usual.

Very interesting Dr. Chang, and are the causes of IBS-C and CIC different? And then if so, in what ways?

Dr. Chang: Well, IBS is a multifactorial disorder and is known as a functional GI disorder. It has been redefined as a disorder of gut-brain interaction, which is a term people are starting to use and hear more.

There's a lot of scientific evidence that has demonstrated that IBS and other similar conditions, including chronic constipation and functional dyspepsia, where there is no structural and biochemical abnormality that you can readily determine, but there's scientific evidence to support that there’s an alteration in the brain-gut communication associated with symptoms. Altered brain-gut interactions are manifested by one or more of the following, which is visceral hypersensitivity, immune function, gut microbiota, gut motility, and central nervous system processing of visceral information. So, this really is a true brain-gut disorder.

There are multiple risk factors when it comes to IBS. It could be infection, or it could be stressful life events, in childhood and/or as an adult. Evidence shows that there can be some familial or genetic predisposition. Food and stress are the main triggers of IBS. Whereas, CIC can be considered a brain-gut disorder, but there's been more focus on gut function, including abnormal motility and defecation. There are three main subtypes of chronic idiopathic constipation.

There are six signs or symptoms that are the diagnostic criteria for CIC and the patient, or the individual, must meet two out of the six criteria, which I ask patients who report having constipation.

The subtypes of CIC are slow transit constipation where the transit time of stool through the colon is slower than normal which can be measured. Then there's normal transit constipation where the transit time of stool through the colon is normal. This group has not been studied that well and it's not completely understood why these patients have constipation, but it could be that they have a greater perception of constipation even though the transit time of stool in the colon is not slow.

And then there's the third group--defecatory disorders. The transit time of stool through the colon of stool can be normal or slow, but coexisting with that, a patient can have a defecation disorder. A common one is called dyssynergic defecation where the pelvic floor and the anal sphincter muscles don't relax appropriately when trying to evacuate stool. In this case, the rectum cannot straighten as much, the pelvic floor doesn't relax and descend, and stool is not easily evacuated.

There are also other conditions such as a significant large rectocele and rectal prolapse. Those are examples of defecatory disorders. So, when you see a patient with CIC, you want to first rule out secondary constipation where another condition or medication is causing constipation, such as hypothyroidism, diabetes, or a neurodegenerative disorder, or medications like opioids or anticholinergics.

CIC means that there isn't another cause of constipation, that is it is not a secondary condition. It's a primary chronic idiopathic constipation.

Let’s talk about the symptoms you're looking for and how they present themselves differently for IBS-C and CIC, at different times, depending on the diagnosis.

Dr. Chang: Sure! I mentioned what the symptom criteria of IBS was, which is having pain of a certain frequency that is associated with altered bowel habits. To determine the bowel habit subtype of IBS, you must assess the predominant stool form. We use the Bristol Stool Form Scale which is a validated stool form scale that's well known. It's publicly available.

The investigators did a survey years ago and they looked at the general population and found that the description of stool really could be encompassed in seven types, and those seven types of stool form correlate with transit time through the bowel. There's type 1 to type 7. Type 1 and 2 are the constipation type stool form where there's harder, drier pellet-like stools and that's associated with slower transit time through the colon. Types 3, 4 and 5 are more within the normal range. Types 6 and 7 are the loose or watery stools are suggestive of faster stool transit and considered indicative of diarrhea.

In patients with IBS-C, at least 25% of their bowel movements are the type 1 or 2, which is the harder, drier stool and less than 25% of bowel movements are loose watery. For diarrhea, it's opposite. IBS-mixed bowel habits, at least 25% of bowel movements are type 1 or 2 and at least 25% are type 6 or 7.

Now, to meet the diagnostic criteria of CIC, you must meet two out of the six criteria. All but one of the criteria must be present with at least 25% of bowel movements. There’s a straining, sensation of incomplete evacuation, use of manual maneuvers to help facilitate stool evacuation, sensation of anorectal blockage, and a Bristol Stool Form Scale of type 1 or 2. The remaining criterion is less than three bowel movements per week. If a patient reports, or endorses, at least two of those six symptoms and signs, then their symptoms meet criteria.

Both IBS-C and CIC are chronic conditions. For the diagnosis of both IBS-C and CIC, symptoms are present for at least three months and started at least six months ago.

What's interesting is that if you ask health care providers and physicians what constipation is and what symptoms define constipation, most of them will say having less than three bowel movements per week or infrequent bowel movements. But it turns out that in chronic constipation patients, they'll report decreased bowel movement frequency. About only a third of them will report that. They'll report the other symptoms of a constipation.

They could have multiple symptoms, but straining is a very common symptom as is hard stools. Even after a bowel movement, they don't feel completely evacuated. That's called sensation of incomplete evacuation. In fact, patients will present with different types of symptoms.

Constipation is often considered a symptom and a diagnosis. And it's fine to use it as a diagnosis, but you really want to delve into what symptoms of constipation they’re experiencing. Are they experiencing straining? Hard stools? Are they not having a bowel movement frequently? That's really part of the history taking so you can determine what the patient perceives as constipation and which symptom are bothersome to them.

So once diagnosed, how different are the treatments for each of the diseases?

Dr. Chang: In both IBS-C and CIC, treatments can include diet, exercise or ambulating more. Often, I will make sure they're drinking plenty of fluids. Those are dietary recommendations such as increasing fiber with foods and/or fiber supplementation. When looking at the difference between IBS-C and CIC, the one thing I should say is that they really exist along a spectrum, so we shouldn't really think of them as two separate diagnoses.

This goes back to the idea we touched on earlier that patients can move back and forth between the different diagnoses. At one point, a patient could have frequent abdominal pain and constipation and the symptoms would meet the criteria for IBS-C. But in the future, the pain gets better or resolves, but there’s still constipation. Their symptoms are more indicative of CIC. So, these conditions really exist along a spectrum.

Because both patients will have constipation symptoms, medications or treatments that help improve constipation can be used for both IBS-C and CIC. The key difference with IBS-C is that in addition to having altered gut motility where they're not moving stool effectively through the bowel, they also have visceral hypersensitivity which manifests as abdominal pain, bloating, and discomfort. Although there may be a modest correlation with bowel habits and IBS, sometimes, they don't correlate that well.

There are some treatments that help pain and constipation and those are the treatments that you want to think about in those patients with IBS-C where they're reporting both pain and constipation.

Now, it's very reasonable to use similar treatments in patients with mild symptoms, whether it's IBS or CIC. But if someone's having more severe IBS-C and they're having a fair amount of pain associated with constipation, you really want to think about treatments that can help reduce pain and constipation and not just constipation.

Treatments can include fiber such as psyllium and osmotic laxatives like polyethylene glycol, which is called MiraLAX, and magnesium-based regimens. These help constipation symptoms, but they don't significantly relieve abdominal pain. If someone came to me with IBS-C and they said, well, I do have pain, but it is mild, maybe a 2 or 3 out of 10, I could probably give them any one of the treatments I just mentioned. But in patients who say that their pain is 8 out of 10 or that it is their predominant symptom, I wouldn't necessarily prescribe the same treatment and would more likely opt for a treatment that has been shown to effectively reduce abdominal pain and constipation.

When you’re looking at the data, are their studies that might show a focus on the treatments and how they might impact the patients differently for IBS-C compared to CIC?

Dr. Chang: Well, the primary study endpoints that are used to determine efficacy of treatment in clinical trials differ in studies of CIC and IBS-C. However, studies also assess individual gastrointestinal symptoms that can be similar in both studies.

So, I would say that treatments that have been shown to be efficacious both in IBS-C and CIC likely relieve constipation symptoms similarly in both groups assuming that the severity of symptoms is comparable. It's just that in the CIC patient population, abdominal pain is not evaluated as much as it is in IBS-C.

F. Mearin, B. E. Lacy, L. Chang, W. D. Chey, A. J. Lembo, M. Simren, et al. Gastroenterology 2016 Vol. 150 Pages 1393-1407. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27144627

D. A. Drossman. Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders: History, Pathophysiology, Clinical Features and Rome IV. Gastroenterology 2016 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27144617

Chang L. How to Approach a Patient with Difficult-to-Treat IBS. Gastroenterology 2021 Accession Number: 34331916 DOI: S0016-5085(21)03285-6 [pii]

10.1053/j.gastro.2021.07.034 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34331916

A. E. Bharucha and B. E. Lacy. Mechanisms, Evaluation, and Management of Chronic Constipation. Gastroenterology 2020 Vol. 158 Issue 5 Pages 1232-1249 e3

Accession Number: 31945360 PMCID: PMC7573977 DOI: S0016-5085(20)30080-9 [pii]10.1053/j.gastro.2019.12.034 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31945360

Lin Chang, MD, serves as the Co-Director of the G. Oppenheimer Center for Neurobiology of Stress and Resilience at UCLA. She is also Program Director of the UCLA Gastroenterology Fellowship Program. Dr. Chang’s expertise is in disorders of gut-brain interaction (also known as functional gastrointestinal disorders), particularly irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). She has recently served as the Clinical Research Councilor of the AGA Governing Board. She previously served as President of the American Neurogastroenterology and Motility Society (ANMS) and is a member of the Rome Foundation Board of Directors.

As a gastroenterologist focused on the pathophysiology of IBS related to stress, sex differences, and neuroendocrine alterations, and the treatment of IBS, Dr. Chang, what exactly is IBS-C and how is CIC defined differently?

Dr. Chang: IBS-C is irritable bowel syndrome with predominantly constipation which is a type of IBS. IBS is a symptom-based diagnosis for a chronic or recurrent gastrointestinal condition where patients have abdominal pain that's associated with constipation, diarrhea, or both. IBS is subtyped by bowel habit predominance into IBS with constipation, IBS with diarrhea, and IBS with mixed bowel habits. With IBS-mixed, one of the subgroups of IBS, they have diarrhea as well as constipation.

Patients will present with abdominal pain for usually one day, a week or even more. Sometimes, a little less. But when they have pain, it's associated with a change in stool frequency, a change in stool form, and/or the pain is related to defecation, meaning that when a patient has a bowel movement, they'll either have more pain or they'll have some pain relief, which is more common.

Now, CIC is Chronic Idiopathic Constipation and that's the term used for chronic constipation where abdominal pain is not a predominant symptom. The main difference between IBS-C and CIC is that abdominal pain is not a predominant or frequent symptom.

Patients with CIC can occasionally get abdominal pain, particularly if they haven't had a bowel movement for a prolonged period of time. However, in patients with IBS-C, they can have some normalization of their bowel habits or their constipation with treatment, although they can still have abdominal pain and discomfort. So, these patients have an element of visceral hypersensitivity where the gut is more sensitive than usual.

Very interesting Dr. Chang, and are the causes of IBS-C and CIC different? And then if so, in what ways?

Dr. Chang: Well, IBS is a multifactorial disorder and is known as a functional GI disorder. It has been redefined as a disorder of gut-brain interaction, which is a term people are starting to use and hear more.

There's a lot of scientific evidence that has demonstrated that IBS and other similar conditions, including chronic constipation and functional dyspepsia, where there is no structural and biochemical abnormality that you can readily determine, but there's scientific evidence to support that there’s an alteration in the brain-gut communication associated with symptoms. Altered brain-gut interactions are manifested by one or more of the following, which is visceral hypersensitivity, immune function, gut microbiota, gut motility, and central nervous system processing of visceral information. So, this really is a true brain-gut disorder.

There are multiple risk factors when it comes to IBS. It could be infection, or it could be stressful life events, in childhood and/or as an adult. Evidence shows that there can be some familial or genetic predisposition. Food and stress are the main triggers of IBS. Whereas, CIC can be considered a brain-gut disorder, but there's been more focus on gut function, including abnormal motility and defecation. There are three main subtypes of chronic idiopathic constipation.

There are six signs or symptoms that are the diagnostic criteria for CIC and the patient, or the individual, must meet two out of the six criteria, which I ask patients who report having constipation.

The subtypes of CIC are slow transit constipation where the transit time of stool through the colon is slower than normal which can be measured. Then there's normal transit constipation where the transit time of stool through the colon is normal. This group has not been studied that well and it's not completely understood why these patients have constipation, but it could be that they have a greater perception of constipation even though the transit time of stool in the colon is not slow.

And then there's the third group--defecatory disorders. The transit time of stool through the colon of stool can be normal or slow, but coexisting with that, a patient can have a defecation disorder. A common one is called dyssynergic defecation where the pelvic floor and the anal sphincter muscles don't relax appropriately when trying to evacuate stool. In this case, the rectum cannot straighten as much, the pelvic floor doesn't relax and descend, and stool is not easily evacuated.

There are also other conditions such as a significant large rectocele and rectal prolapse. Those are examples of defecatory disorders. So, when you see a patient with CIC, you want to first rule out secondary constipation where another condition or medication is causing constipation, such as hypothyroidism, diabetes, or a neurodegenerative disorder, or medications like opioids or anticholinergics.

CIC means that there isn't another cause of constipation, that is it is not a secondary condition. It's a primary chronic idiopathic constipation.

Let’s talk about the symptoms you're looking for and how they present themselves differently for IBS-C and CIC, at different times, depending on the diagnosis.

Dr. Chang: Sure! I mentioned what the symptom criteria of IBS was, which is having pain of a certain frequency that is associated with altered bowel habits. To determine the bowel habit subtype of IBS, you must assess the predominant stool form. We use the Bristol Stool Form Scale which is a validated stool form scale that's well known. It's publicly available.

The investigators did a survey years ago and they looked at the general population and found that the description of stool really could be encompassed in seven types, and those seven types of stool form correlate with transit time through the bowel. There's type 1 to type 7. Type 1 and 2 are the constipation type stool form where there's harder, drier pellet-like stools and that's associated with slower transit time through the colon. Types 3, 4 and 5 are more within the normal range. Types 6 and 7 are the loose or watery stools are suggestive of faster stool transit and considered indicative of diarrhea.

In patients with IBS-C, at least 25% of their bowel movements are the type 1 or 2, which is the harder, drier stool and less than 25% of bowel movements are loose watery. For diarrhea, it's opposite. IBS-mixed bowel habits, at least 25% of bowel movements are type 1 or 2 and at least 25% are type 6 or 7.

Now, to meet the diagnostic criteria of CIC, you must meet two out of the six criteria. All but one of the criteria must be present with at least 25% of bowel movements. There’s a straining, sensation of incomplete evacuation, use of manual maneuvers to help facilitate stool evacuation, sensation of anorectal blockage, and a Bristol Stool Form Scale of type 1 or 2. The remaining criterion is less than three bowel movements per week. If a patient reports, or endorses, at least two of those six symptoms and signs, then their symptoms meet criteria.

Both IBS-C and CIC are chronic conditions. For the diagnosis of both IBS-C and CIC, symptoms are present for at least three months and started at least six months ago.

What's interesting is that if you ask health care providers and physicians what constipation is and what symptoms define constipation, most of them will say having less than three bowel movements per week or infrequent bowel movements. But it turns out that in chronic constipation patients, they'll report decreased bowel movement frequency. About only a third of them will report that. They'll report the other symptoms of a constipation.

They could have multiple symptoms, but straining is a very common symptom as is hard stools. Even after a bowel movement, they don't feel completely evacuated. That's called sensation of incomplete evacuation. In fact, patients will present with different types of symptoms.

Constipation is often considered a symptom and a diagnosis. And it's fine to use it as a diagnosis, but you really want to delve into what symptoms of constipation they’re experiencing. Are they experiencing straining? Hard stools? Are they not having a bowel movement frequently? That's really part of the history taking so you can determine what the patient perceives as constipation and which symptom are bothersome to them.

So once diagnosed, how different are the treatments for each of the diseases?

Dr. Chang: In both IBS-C and CIC, treatments can include diet, exercise or ambulating more. Often, I will make sure they're drinking plenty of fluids. Those are dietary recommendations such as increasing fiber with foods and/or fiber supplementation. When looking at the difference between IBS-C and CIC, the one thing I should say is that they really exist along a spectrum, so we shouldn't really think of them as two separate diagnoses.

This goes back to the idea we touched on earlier that patients can move back and forth between the different diagnoses. At one point, a patient could have frequent abdominal pain and constipation and the symptoms would meet the criteria for IBS-C. But in the future, the pain gets better or resolves, but there’s still constipation. Their symptoms are more indicative of CIC. So, these conditions really exist along a spectrum.

Because both patients will have constipation symptoms, medications or treatments that help improve constipation can be used for both IBS-C and CIC. The key difference with IBS-C is that in addition to having altered gut motility where they're not moving stool effectively through the bowel, they also have visceral hypersensitivity which manifests as abdominal pain, bloating, and discomfort. Although there may be a modest correlation with bowel habits and IBS, sometimes, they don't correlate that well.

There are some treatments that help pain and constipation and those are the treatments that you want to think about in those patients with IBS-C where they're reporting both pain and constipation.

Now, it's very reasonable to use similar treatments in patients with mild symptoms, whether it's IBS or CIC. But if someone's having more severe IBS-C and they're having a fair amount of pain associated with constipation, you really want to think about treatments that can help reduce pain and constipation and not just constipation.

Treatments can include fiber such as psyllium and osmotic laxatives like polyethylene glycol, which is called MiraLAX, and magnesium-based regimens. These help constipation symptoms, but they don't significantly relieve abdominal pain. If someone came to me with IBS-C and they said, well, I do have pain, but it is mild, maybe a 2 or 3 out of 10, I could probably give them any one of the treatments I just mentioned. But in patients who say that their pain is 8 out of 10 or that it is their predominant symptom, I wouldn't necessarily prescribe the same treatment and would more likely opt for a treatment that has been shown to effectively reduce abdominal pain and constipation.

When you’re looking at the data, are their studies that might show a focus on the treatments and how they might impact the patients differently for IBS-C compared to CIC?

Dr. Chang: Well, the primary study endpoints that are used to determine efficacy of treatment in clinical trials differ in studies of CIC and IBS-C. However, studies also assess individual gastrointestinal symptoms that can be similar in both studies.

So, I would say that treatments that have been shown to be efficacious both in IBS-C and CIC likely relieve constipation symptoms similarly in both groups assuming that the severity of symptoms is comparable. It's just that in the CIC patient population, abdominal pain is not evaluated as much as it is in IBS-C.

Lin Chang, MD, serves as the Co-Director of the G. Oppenheimer Center for Neurobiology of Stress and Resilience at UCLA. She is also Program Director of the UCLA Gastroenterology Fellowship Program. Dr. Chang’s expertise is in disorders of gut-brain interaction (also known as functional gastrointestinal disorders), particularly irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). She has recently served as the Clinical Research Councilor of the AGA Governing Board. She previously served as President of the American Neurogastroenterology and Motility Society (ANMS) and is a member of the Rome Foundation Board of Directors.

As a gastroenterologist focused on the pathophysiology of IBS related to stress, sex differences, and neuroendocrine alterations, and the treatment of IBS, Dr. Chang, what exactly is IBS-C and how is CIC defined differently?

Dr. Chang: IBS-C is irritable bowel syndrome with predominantly constipation which is a type of IBS. IBS is a symptom-based diagnosis for a chronic or recurrent gastrointestinal condition where patients have abdominal pain that's associated with constipation, diarrhea, or both. IBS is subtyped by bowel habit predominance into IBS with constipation, IBS with diarrhea, and IBS with mixed bowel habits. With IBS-mixed, one of the subgroups of IBS, they have diarrhea as well as constipation.

Patients will present with abdominal pain for usually one day, a week or even more. Sometimes, a little less. But when they have pain, it's associated with a change in stool frequency, a change in stool form, and/or the pain is related to defecation, meaning that when a patient has a bowel movement, they'll either have more pain or they'll have some pain relief, which is more common.

Now, CIC is Chronic Idiopathic Constipation and that's the term used for chronic constipation where abdominal pain is not a predominant symptom. The main difference between IBS-C and CIC is that abdominal pain is not a predominant or frequent symptom.

Patients with CIC can occasionally get abdominal pain, particularly if they haven't had a bowel movement for a prolonged period of time. However, in patients with IBS-C, they can have some normalization of their bowel habits or their constipation with treatment, although they can still have abdominal pain and discomfort. So, these patients have an element of visceral hypersensitivity where the gut is more sensitive than usual.

Very interesting Dr. Chang, and are the causes of IBS-C and CIC different? And then if so, in what ways?

Dr. Chang: Well, IBS is a multifactorial disorder and is known as a functional GI disorder. It has been redefined as a disorder of gut-brain interaction, which is a term people are starting to use and hear more.

There's a lot of scientific evidence that has demonstrated that IBS and other similar conditions, including chronic constipation and functional dyspepsia, where there is no structural and biochemical abnormality that you can readily determine, but there's scientific evidence to support that there’s an alteration in the brain-gut communication associated with symptoms. Altered brain-gut interactions are manifested by one or more of the following, which is visceral hypersensitivity, immune function, gut microbiota, gut motility, and central nervous system processing of visceral information. So, this really is a true brain-gut disorder.

There are multiple risk factors when it comes to IBS. It could be infection, or it could be stressful life events, in childhood and/or as an adult. Evidence shows that there can be some familial or genetic predisposition. Food and stress are the main triggers of IBS. Whereas, CIC can be considered a brain-gut disorder, but there's been more focus on gut function, including abnormal motility and defecation. There are three main subtypes of chronic idiopathic constipation.

There are six signs or symptoms that are the diagnostic criteria for CIC and the patient, or the individual, must meet two out of the six criteria, which I ask patients who report having constipation.

The subtypes of CIC are slow transit constipation where the transit time of stool through the colon is slower than normal which can be measured. Then there's normal transit constipation where the transit time of stool through the colon is normal. This group has not been studied that well and it's not completely understood why these patients have constipation, but it could be that they have a greater perception of constipation even though the transit time of stool in the colon is not slow.

And then there's the third group--defecatory disorders. The transit time of stool through the colon of stool can be normal or slow, but coexisting with that, a patient can have a defecation disorder. A common one is called dyssynergic defecation where the pelvic floor and the anal sphincter muscles don't relax appropriately when trying to evacuate stool. In this case, the rectum cannot straighten as much, the pelvic floor doesn't relax and descend, and stool is not easily evacuated.

There are also other conditions such as a significant large rectocele and rectal prolapse. Those are examples of defecatory disorders. So, when you see a patient with CIC, you want to first rule out secondary constipation where another condition or medication is causing constipation, such as hypothyroidism, diabetes, or a neurodegenerative disorder, or medications like opioids or anticholinergics.

CIC means that there isn't another cause of constipation, that is it is not a secondary condition. It's a primary chronic idiopathic constipation.

Let’s talk about the symptoms you're looking for and how they present themselves differently for IBS-C and CIC, at different times, depending on the diagnosis.

Dr. Chang: Sure! I mentioned what the symptom criteria of IBS was, which is having pain of a certain frequency that is associated with altered bowel habits. To determine the bowel habit subtype of IBS, you must assess the predominant stool form. We use the Bristol Stool Form Scale which is a validated stool form scale that's well known. It's publicly available.

The investigators did a survey years ago and they looked at the general population and found that the description of stool really could be encompassed in seven types, and those seven types of stool form correlate with transit time through the bowel. There's type 1 to type 7. Type 1 and 2 are the constipation type stool form where there's harder, drier pellet-like stools and that's associated with slower transit time through the colon. Types 3, 4 and 5 are more within the normal range. Types 6 and 7 are the loose or watery stools are suggestive of faster stool transit and considered indicative of diarrhea.

In patients with IBS-C, at least 25% of their bowel movements are the type 1 or 2, which is the harder, drier stool and less than 25% of bowel movements are loose watery. For diarrhea, it's opposite. IBS-mixed bowel habits, at least 25% of bowel movements are type 1 or 2 and at least 25% are type 6 or 7.

Now, to meet the diagnostic criteria of CIC, you must meet two out of the six criteria. All but one of the criteria must be present with at least 25% of bowel movements. There’s a straining, sensation of incomplete evacuation, use of manual maneuvers to help facilitate stool evacuation, sensation of anorectal blockage, and a Bristol Stool Form Scale of type 1 or 2. The remaining criterion is less than three bowel movements per week. If a patient reports, or endorses, at least two of those six symptoms and signs, then their symptoms meet criteria.

Both IBS-C and CIC are chronic conditions. For the diagnosis of both IBS-C and CIC, symptoms are present for at least three months and started at least six months ago.

What's interesting is that if you ask health care providers and physicians what constipation is and what symptoms define constipation, most of them will say having less than three bowel movements per week or infrequent bowel movements. But it turns out that in chronic constipation patients, they'll report decreased bowel movement frequency. About only a third of them will report that. They'll report the other symptoms of a constipation.

They could have multiple symptoms, but straining is a very common symptom as is hard stools. Even after a bowel movement, they don't feel completely evacuated. That's called sensation of incomplete evacuation. In fact, patients will present with different types of symptoms.

Constipation is often considered a symptom and a diagnosis. And it's fine to use it as a diagnosis, but you really want to delve into what symptoms of constipation they’re experiencing. Are they experiencing straining? Hard stools? Are they not having a bowel movement frequently? That's really part of the history taking so you can determine what the patient perceives as constipation and which symptom are bothersome to them.

So once diagnosed, how different are the treatments for each of the diseases?

Dr. Chang: In both IBS-C and CIC, treatments can include diet, exercise or ambulating more. Often, I will make sure they're drinking plenty of fluids. Those are dietary recommendations such as increasing fiber with foods and/or fiber supplementation. When looking at the difference between IBS-C and CIC, the one thing I should say is that they really exist along a spectrum, so we shouldn't really think of them as two separate diagnoses.

This goes back to the idea we touched on earlier that patients can move back and forth between the different diagnoses. At one point, a patient could have frequent abdominal pain and constipation and the symptoms would meet the criteria for IBS-C. But in the future, the pain gets better or resolves, but there’s still constipation. Their symptoms are more indicative of CIC. So, these conditions really exist along a spectrum.

Because both patients will have constipation symptoms, medications or treatments that help improve constipation can be used for both IBS-C and CIC. The key difference with IBS-C is that in addition to having altered gut motility where they're not moving stool effectively through the bowel, they also have visceral hypersensitivity which manifests as abdominal pain, bloating, and discomfort. Although there may be a modest correlation with bowel habits and IBS, sometimes, they don't correlate that well.

There are some treatments that help pain and constipation and those are the treatments that you want to think about in those patients with IBS-C where they're reporting both pain and constipation.

Now, it's very reasonable to use similar treatments in patients with mild symptoms, whether it's IBS or CIC. But if someone's having more severe IBS-C and they're having a fair amount of pain associated with constipation, you really want to think about treatments that can help reduce pain and constipation and not just constipation.

Treatments can include fiber such as psyllium and osmotic laxatives like polyethylene glycol, which is called MiraLAX, and magnesium-based regimens. These help constipation symptoms, but they don't significantly relieve abdominal pain. If someone came to me with IBS-C and they said, well, I do have pain, but it is mild, maybe a 2 or 3 out of 10, I could probably give them any one of the treatments I just mentioned. But in patients who say that their pain is 8 out of 10 or that it is their predominant symptom, I wouldn't necessarily prescribe the same treatment and would more likely opt for a treatment that has been shown to effectively reduce abdominal pain and constipation.

When you’re looking at the data, are their studies that might show a focus on the treatments and how they might impact the patients differently for IBS-C compared to CIC?

Dr. Chang: Well, the primary study endpoints that are used to determine efficacy of treatment in clinical trials differ in studies of CIC and IBS-C. However, studies also assess individual gastrointestinal symptoms that can be similar in both studies.

So, I would say that treatments that have been shown to be efficacious both in IBS-C and CIC likely relieve constipation symptoms similarly in both groups assuming that the severity of symptoms is comparable. It's just that in the CIC patient population, abdominal pain is not evaluated as much as it is in IBS-C.

F. Mearin, B. E. Lacy, L. Chang, W. D. Chey, A. J. Lembo, M. Simren, et al. Gastroenterology 2016 Vol. 150 Pages 1393-1407. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27144627

D. A. Drossman. Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders: History, Pathophysiology, Clinical Features and Rome IV. Gastroenterology 2016 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27144617

Chang L. How to Approach a Patient with Difficult-to-Treat IBS. Gastroenterology 2021 Accession Number: 34331916 DOI: S0016-5085(21)03285-6 [pii]

10.1053/j.gastro.2021.07.034 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34331916

A. E. Bharucha and B. E. Lacy. Mechanisms, Evaluation, and Management of Chronic Constipation. Gastroenterology 2020 Vol. 158 Issue 5 Pages 1232-1249 e3

Accession Number: 31945360 PMCID: PMC7573977 DOI: S0016-5085(20)30080-9 [pii]10.1053/j.gastro.2019.12.034 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31945360

F. Mearin, B. E. Lacy, L. Chang, W. D. Chey, A. J. Lembo, M. Simren, et al. Gastroenterology 2016 Vol. 150 Pages 1393-1407. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27144627

D. A. Drossman. Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders: History, Pathophysiology, Clinical Features and Rome IV. Gastroenterology 2016 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27144617

Chang L. How to Approach a Patient with Difficult-to-Treat IBS. Gastroenterology 2021 Accession Number: 34331916 DOI: S0016-5085(21)03285-6 [pii]

10.1053/j.gastro.2021.07.034 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34331916

A. E. Bharucha and B. E. Lacy. Mechanisms, Evaluation, and Management of Chronic Constipation. Gastroenterology 2020 Vol. 158 Issue 5 Pages 1232-1249 e3

Accession Number: 31945360 PMCID: PMC7573977 DOI: S0016-5085(20)30080-9 [pii]10.1053/j.gastro.2019.12.034 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31945360

IBS and low-FODMAP diets

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is a common gastrointestinal disorder that is manifested by abdominal pain and altered bowel habits. Many IBS patients report meal-related exacerbations in symptoms, which may be due to true food intolerances but can be also due to visceral hypersensitivity or changes in gut microbiota. Gut microbiota can be significantly altered by changing the intake of fiber and fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides and polyols, referred to by the acronym FODMAPs. High-FODMAP foods include those with excess fructose (e.g., honey, peaches, dried fruits), fructans (e.g., wheat, rye, onions), sorbitol (e.g., apricots, prunes, sweeteners), and raffinose (e.g., lentils, cabbage, legumes).

A high-FODMAP diet can result in increased gas and colonic distension from bacterial fermentation, and increased water in the small bowel due to the high osmotic load. In one study, a high-FODMAP diet was associated with higher levels of breath hydrogen compared with a low-FODMAP diet in both IBS patients and healthy controls, but it only induced GI symptoms and lethargy in IBS patients (J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2010;25:1366-73). Dr. Murray and colleagues (Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2014;109:110-9) measured breath hydrogen as well as small bowel water content and colonic gas and distension using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans of the abdomen in healthy volunteers. Intake of fructose, which has a high osmotic load, was associated with increased small bowel water content compared with glucose and inulin (osmotically inactive fructan). However, inulin increased breath hydrogen and colonic gas to a greater extent than fructose and glucose.

Studies have demonstrated a beneficial effect of a low-FODMAP diet in IBS patients. In one study, IBS patients who followed a low-FODMAP diet reported a better overall and individual symptom response (i.e., bloating, abdominal pain, and flatulence) compared with patients on a standard diet (J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2011;5:487-95). A recent crossover trial conducted in Australia compared a low-FODMAP diet to a typical Australian diet, which included high-FODMAP foods, for 21 days each (Gastroenterology 2014;146:67-75). Patients with IBS (n = 30) had lower GI symptom scores on a low-FODMAP diet compared with the Australian diet. Seventy-five percent of the IBS patients had evidence of fructose malabsorption but this did not have an effect on their response to a low-FODMAP diet.

A beneficial response to a low-FODMAP diet has been speculated to be primarily due to avoiding gluten, however this has not been supported by studies. Some IBS patients have reported significant improvement in GI and non-GI (e.g., tiredness) while on a gluten free diet. Dr. Biesikierski and colleagues (Gastroenterology 2013;145:320-8) conducted a double-blind crossover study in 37 IBS patients with nonceliac gluten sensitivity who were placed on a 2-week trial on a low-FODMAP diet and then randomly assigned to a high-gluten, low-gluten, or control (whey protein) diet for 1 week each. GI symptoms improved in all subjects while on a low-FODMAP diet. Symptoms worsened to a similar degree when the gluten or whey was added to their diets but there was no difference between these groups. The study found that there were no specific or dose-dependent effects of gluten in IBS patients who experienced symptom improvement on a low-FODMAP diet. At the recent Digestive Disease Week meeting, a study by Dr. Piacentino et al. (Gastroenterology suppl 2014;146:S-82) addressed this issue further by comparing GI symptoms (i.e., bloating, abdominal distension and abdominal pain) in IBS patients on a: 1) low-FODMAP, gluten-free diet, 2) a low-FODMAP and normal gluten diet, and 3) a normal-FODMAP and gluten-free diet (n = 20 in each group). A low-FODMAP diet with or without gluten was associated with a significant improvement in bloating, abdominal distension, and abdominal pain, compared to a normal FODMAP and gluten diet. There were no significant differences between the two low-FODMAP diets. The authors concluded that gluten avoidance did not add significant benefit to the low-FODMAP diet.

In summary, limited data, which is mainly comprised of studies with relatively small sample sizes, support IBS symptom improvement with a low-FODMAP diet. Fructose and fructans may have different mechanisms by which they cause symptoms in IBS. The beneficial effect of a low-FODMAP diet does not appear to be predominantly based on gluten avoidance. Lastly, there are no definite biomarkers as of now that are associated with symptom response.

Dr. Chang is professor of digestive diseases/gastroenterology, director of the Digestive Health and Nutrition Clinic and the University of California, Los Angeles, GI Fellowship Training Program, and co-director of the Center for Neurobiology of Stress, all at UCLA. Her comments were made at the annual Digestive Disease Week during the ASGE and AGA joint Presidential Plenary.

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is a common gastrointestinal disorder that is manifested by abdominal pain and altered bowel habits. Many IBS patients report meal-related exacerbations in symptoms, which may be due to true food intolerances but can be also due to visceral hypersensitivity or changes in gut microbiota. Gut microbiota can be significantly altered by changing the intake of fiber and fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides and polyols, referred to by the acronym FODMAPs. High-FODMAP foods include those with excess fructose (e.g., honey, peaches, dried fruits), fructans (e.g., wheat, rye, onions), sorbitol (e.g., apricots, prunes, sweeteners), and raffinose (e.g., lentils, cabbage, legumes).

A high-FODMAP diet can result in increased gas and colonic distension from bacterial fermentation, and increased water in the small bowel due to the high osmotic load. In one study, a high-FODMAP diet was associated with higher levels of breath hydrogen compared with a low-FODMAP diet in both IBS patients and healthy controls, but it only induced GI symptoms and lethargy in IBS patients (J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2010;25:1366-73). Dr. Murray and colleagues (Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2014;109:110-9) measured breath hydrogen as well as small bowel water content and colonic gas and distension using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans of the abdomen in healthy volunteers. Intake of fructose, which has a high osmotic load, was associated with increased small bowel water content compared with glucose and inulin (osmotically inactive fructan). However, inulin increased breath hydrogen and colonic gas to a greater extent than fructose and glucose.

Studies have demonstrated a beneficial effect of a low-FODMAP diet in IBS patients. In one study, IBS patients who followed a low-FODMAP diet reported a better overall and individual symptom response (i.e., bloating, abdominal pain, and flatulence) compared with patients on a standard diet (J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2011;5:487-95). A recent crossover trial conducted in Australia compared a low-FODMAP diet to a typical Australian diet, which included high-FODMAP foods, for 21 days each (Gastroenterology 2014;146:67-75). Patients with IBS (n = 30) had lower GI symptom scores on a low-FODMAP diet compared with the Australian diet. Seventy-five percent of the IBS patients had evidence of fructose malabsorption but this did not have an effect on their response to a low-FODMAP diet.

A beneficial response to a low-FODMAP diet has been speculated to be primarily due to avoiding gluten, however this has not been supported by studies. Some IBS patients have reported significant improvement in GI and non-GI (e.g., tiredness) while on a gluten free diet. Dr. Biesikierski and colleagues (Gastroenterology 2013;145:320-8) conducted a double-blind crossover study in 37 IBS patients with nonceliac gluten sensitivity who were placed on a 2-week trial on a low-FODMAP diet and then randomly assigned to a high-gluten, low-gluten, or control (whey protein) diet for 1 week each. GI symptoms improved in all subjects while on a low-FODMAP diet. Symptoms worsened to a similar degree when the gluten or whey was added to their diets but there was no difference between these groups. The study found that there were no specific or dose-dependent effects of gluten in IBS patients who experienced symptom improvement on a low-FODMAP diet. At the recent Digestive Disease Week meeting, a study by Dr. Piacentino et al. (Gastroenterology suppl 2014;146:S-82) addressed this issue further by comparing GI symptoms (i.e., bloating, abdominal distension and abdominal pain) in IBS patients on a: 1) low-FODMAP, gluten-free diet, 2) a low-FODMAP and normal gluten diet, and 3) a normal-FODMAP and gluten-free diet (n = 20 in each group). A low-FODMAP diet with or without gluten was associated with a significant improvement in bloating, abdominal distension, and abdominal pain, compared to a normal FODMAP and gluten diet. There were no significant differences between the two low-FODMAP diets. The authors concluded that gluten avoidance did not add significant benefit to the low-FODMAP diet.

In summary, limited data, which is mainly comprised of studies with relatively small sample sizes, support IBS symptom improvement with a low-FODMAP diet. Fructose and fructans may have different mechanisms by which they cause symptoms in IBS. The beneficial effect of a low-FODMAP diet does not appear to be predominantly based on gluten avoidance. Lastly, there are no definite biomarkers as of now that are associated with symptom response.

Dr. Chang is professor of digestive diseases/gastroenterology, director of the Digestive Health and Nutrition Clinic and the University of California, Los Angeles, GI Fellowship Training Program, and co-director of the Center for Neurobiology of Stress, all at UCLA. Her comments were made at the annual Digestive Disease Week during the ASGE and AGA joint Presidential Plenary.

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is a common gastrointestinal disorder that is manifested by abdominal pain and altered bowel habits. Many IBS patients report meal-related exacerbations in symptoms, which may be due to true food intolerances but can be also due to visceral hypersensitivity or changes in gut microbiota. Gut microbiota can be significantly altered by changing the intake of fiber and fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides and polyols, referred to by the acronym FODMAPs. High-FODMAP foods include those with excess fructose (e.g., honey, peaches, dried fruits), fructans (e.g., wheat, rye, onions), sorbitol (e.g., apricots, prunes, sweeteners), and raffinose (e.g., lentils, cabbage, legumes).

A high-FODMAP diet can result in increased gas and colonic distension from bacterial fermentation, and increased water in the small bowel due to the high osmotic load. In one study, a high-FODMAP diet was associated with higher levels of breath hydrogen compared with a low-FODMAP diet in both IBS patients and healthy controls, but it only induced GI symptoms and lethargy in IBS patients (J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2010;25:1366-73). Dr. Murray and colleagues (Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2014;109:110-9) measured breath hydrogen as well as small bowel water content and colonic gas and distension using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans of the abdomen in healthy volunteers. Intake of fructose, which has a high osmotic load, was associated with increased small bowel water content compared with glucose and inulin (osmotically inactive fructan). However, inulin increased breath hydrogen and colonic gas to a greater extent than fructose and glucose.

Studies have demonstrated a beneficial effect of a low-FODMAP diet in IBS patients. In one study, IBS patients who followed a low-FODMAP diet reported a better overall and individual symptom response (i.e., bloating, abdominal pain, and flatulence) compared with patients on a standard diet (J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2011;5:487-95). A recent crossover trial conducted in Australia compared a low-FODMAP diet to a typical Australian diet, which included high-FODMAP foods, for 21 days each (Gastroenterology 2014;146:67-75). Patients with IBS (n = 30) had lower GI symptom scores on a low-FODMAP diet compared with the Australian diet. Seventy-five percent of the IBS patients had evidence of fructose malabsorption but this did not have an effect on their response to a low-FODMAP diet.

A beneficial response to a low-FODMAP diet has been speculated to be primarily due to avoiding gluten, however this has not been supported by studies. Some IBS patients have reported significant improvement in GI and non-GI (e.g., tiredness) while on a gluten free diet. Dr. Biesikierski and colleagues (Gastroenterology 2013;145:320-8) conducted a double-blind crossover study in 37 IBS patients with nonceliac gluten sensitivity who were placed on a 2-week trial on a low-FODMAP diet and then randomly assigned to a high-gluten, low-gluten, or control (whey protein) diet for 1 week each. GI symptoms improved in all subjects while on a low-FODMAP diet. Symptoms worsened to a similar degree when the gluten or whey was added to their diets but there was no difference between these groups. The study found that there were no specific or dose-dependent effects of gluten in IBS patients who experienced symptom improvement on a low-FODMAP diet. At the recent Digestive Disease Week meeting, a study by Dr. Piacentino et al. (Gastroenterology suppl 2014;146:S-82) addressed this issue further by comparing GI symptoms (i.e., bloating, abdominal distension and abdominal pain) in IBS patients on a: 1) low-FODMAP, gluten-free diet, 2) a low-FODMAP and normal gluten diet, and 3) a normal-FODMAP and gluten-free diet (n = 20 in each group). A low-FODMAP diet with or without gluten was associated with a significant improvement in bloating, abdominal distension, and abdominal pain, compared to a normal FODMAP and gluten diet. There were no significant differences between the two low-FODMAP diets. The authors concluded that gluten avoidance did not add significant benefit to the low-FODMAP diet.

In summary, limited data, which is mainly comprised of studies with relatively small sample sizes, support IBS symptom improvement with a low-FODMAP diet. Fructose and fructans may have different mechanisms by which they cause symptoms in IBS. The beneficial effect of a low-FODMAP diet does not appear to be predominantly based on gluten avoidance. Lastly, there are no definite biomarkers as of now that are associated with symptom response.

Dr. Chang is professor of digestive diseases/gastroenterology, director of the Digestive Health and Nutrition Clinic and the University of California, Los Angeles, GI Fellowship Training Program, and co-director of the Center for Neurobiology of Stress, all at UCLA. Her comments were made at the annual Digestive Disease Week during the ASGE and AGA joint Presidential Plenary.