User login

Robotic vesicovaginal fistula repair: A systematic, endoscopic approach

In modern times in the United States, the vesicovaginal fistula (VVF) arises chiefly as a sequela of gynecologic surgery, usually hysterectomy. The injury most likely occurs at the time of dissection of the bladder flap off of the lower uterine segment and upper vagina.1 With increasing use of endoscopy and electrosurgery at the time of hysterectomy,2 the occurrence of VVF is likely to increase. Because of this, fistulas stemming from benign gynecologic surgical activity tend to occur above the trigone near the vaginal cuff.

Current technique of fistula repair involves either a vaginal approach, with the Latsko procedure,3 or an abdominal approach, involving a laparotomy; laparoscopy also is used with increasing frequency.4

Vaginal versus endoscopic approach. The vaginal approach can be straightforward, such as in cases of vault prolapse or a distally located fistula, or more difficult if the fistula is apical in location, especially if the apex is well suspended and the vagina is of normal length. I have found the abdominal approach to be optimal if the fistula is near the cuff and the vagina is of normal length and well suspended.

Classical teaching tells us that the first repair of the VVF is likely to be the most successful, with successively lower cure rates as the number of repair attempts increases. For this reason, I advocate the abdominal approach in most cases of apically placed VVFs.

Surgical approach

Why endoscopic, why robotic? Often, repair of the VVF is complicated by:

-

the challenge of locating the defect in the bladder

-

the technical difficulty in oversewing the bladder, which often must be done on the underside of the bladder, between the vaginal and bladder walls.

To tackle these challenges, an endoscopic approach promises improved visualization, and the robotic approach allows for surgical closure with improved visibility characteristic of endoscopy, while preserving the manual dexterity characteristic of open surgery.

Timing. It is believed that, in order to improve chances of successful surgical repair, the fistula should be approached either immediately (ie, within 1 to 2 weeks of the insult) or delayed by 8 to 12 or more weeks after the causative surgery.5

Preparation. Vesicovaginal fistulas can rarely involve the ureters, and this ureteric involvement needs to be ruled out. Accordingly, the workup of the VVF should begin with a thorough cystoscopic evaluation of the bladder, with retrograde pyelography to evaluate the integrity of the ureters bilaterally.

During this procedure, the location of the fistulous tract should be meticulously mapped. Care should be taken to document the location and extent of the fistula, as well as to identify the presence of multiple or separate tracts. If these tracts are present, they also need also to be catalogued. In my practice, the cystoscopy/retrograde pyelogram is performed as a separate surgical encounter.

Surgical technique

After the fistula is mapped and ureteric integrity is confirmed, the definitive surgical repair is performed. The steps to the surgical approach are straightforward.

1. Insert stents into the fistula and bilaterally into the ureters

Stenting the fistula permits rapid identification of the fistula tract without the need to enter the bladder separately. The ureteric stents you use should be one color, and the fistula stent should be a second color. I use 5 French yellow stents to cannulate the ureters and a 6 French blue stent for the fistula itself. Insert the fistula stent from the bladder side of the fistula. It should exit through the vagina (FIGURES 1A and 1B). In addition, place a 3-way Foley catheter for drainage and irrigate the bladder when indicated.

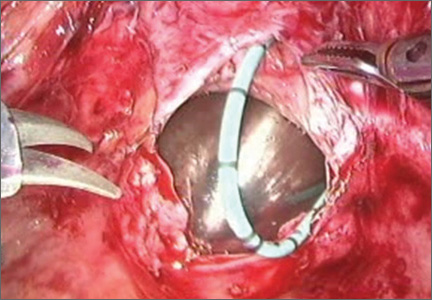

Figure 1. Stent insertion

Cystoscopically place a 6 French blue stent into the bladder side of the fistula. (A) The stent as seen from inside the bladder. (B) The stent as seen from the vaginal side.

2. Place the ports for optimal access

A 0° camera is adequate for visualization. Port placement is similar to that used for robotic sacral colpopexy; I use a supraumbilically placed camera port and three 8-mm robot ports (two on the left and one on the right of the umbilicus). Each port should be separated by about 10 cm. An assistant port is placed to the far right, for passing and retrieving sutures (FIGURE 2). An atraumatic grasper, monopolar scissors, and bipolar Maryland-type forceps are placed within the ports to begin the surgical procedure.

Figure 2. Ideal port placement

Place the camera port supraunbilically, with two 8-mm robot ports

3. Place a vaginal stent to aid dissection

The stent should be a sterile cylinder and have a diameter of 2 cm to 5 cm (to match the vaginal caliber). The tip should be rounded and flattened, with an extended handle available for manipulating the stent. The handle can be held by an assistant or attached to an external uterine positioning system (FIGURE 3); I use the Uterine Positioning SystemTM (Cooper Surgical, Trumbull, Connecticut).

4. Incise the vaginal cuff

Transversely incise the vaginal cuff with the monopolar scissors (VIDEO 1).

This allows entry into the vagina at the apex. The blue stent in the fistula should be visible at the anterior vaginal wall, as demonstrated in FIGURE 4.

5. Dissect the vaginal wall

Dissect the anterior vaginal wall down to the fistula, and dissect the bladder off of the vaginal wall for about 1.5 cm to 2 cm around the fistula tract (FIGURE 5 and VIDEO 2).

6. Cut the stent

Cut the stent passing thru the fistula, to move it out of the way.

7. Close the bladder

Stitch the bladder in a running fashion using three layers of 3-0 rapid absorbable synthetic suture (FIGURE 6 and Video 3 . I prefer polyglactin 910 (Vicryl; Ethicon, Somerville, New Jersey) because it is easier to handle.

FIGURE 6: Close the bladderStitch the bladder in a running fashion using three layers of 3-0 rapid absorbable synthetic suture. Keep the closure line free of tension.

8. Close the vaginal side of the fistula

Stitch the vaginal side of the fistula in a running fashion with 2-0 absorbable synthetic suture.

9. Verify closure

Check for watertight closure by retrofilling the bladder with 100 mL of sterile milk (obtained from the labor/delivery suite). Observe the suture line for any evidence of milk leakage. (Sterile milk does not stain the tissues, and this preserves tissue visibility. For this reason, milk is preferable to indigo carmine or methylene blue.)

10. Remove the stents from the bladder

Cystoscopically remove all stents.

11. Close the laparoscopic ports

12. Follow up to ensure surgical success

Leave the indwelling Foley catheter in place for 2 to 3 weeks. After such time, remove the catheter and perform voiding cystourethrogram to document bladder wall integrity.

Discussion

I have described a systematic approach to robotic VVF repair. The robotic portion of the procedure should require about 60 to 90 minutes in the absence of significant adhesions. The technique is amenable to a laparoscopic approach, when performed by an appropriately skilled operator.

Final takeaways. Important takeaways to this repair include:

- Stent the fistula to make it easy to find intraoperatively.

- Enter the vagina from above to rapidly locate the fistula tract.

- Use sterile milk to fill the bladder to look for leaks. This works without staining the tissues.

- Minimize tension on the bladder suture line.

In modern times in the United States, the vesicovaginal fistula (VVF) arises chiefly as a sequela of gynecologic surgery, usually hysterectomy. The injury most likely occurs at the time of dissection of the bladder flap off of the lower uterine segment and upper vagina.1 With increasing use of endoscopy and electrosurgery at the time of hysterectomy,2 the occurrence of VVF is likely to increase. Because of this, fistulas stemming from benign gynecologic surgical activity tend to occur above the trigone near the vaginal cuff.

Current technique of fistula repair involves either a vaginal approach, with the Latsko procedure,3 or an abdominal approach, involving a laparotomy; laparoscopy also is used with increasing frequency.4

Vaginal versus endoscopic approach. The vaginal approach can be straightforward, such as in cases of vault prolapse or a distally located fistula, or more difficult if the fistula is apical in location, especially if the apex is well suspended and the vagina is of normal length. I have found the abdominal approach to be optimal if the fistula is near the cuff and the vagina is of normal length and well suspended.

Classical teaching tells us that the first repair of the VVF is likely to be the most successful, with successively lower cure rates as the number of repair attempts increases. For this reason, I advocate the abdominal approach in most cases of apically placed VVFs.

Surgical approach

Why endoscopic, why robotic? Often, repair of the VVF is complicated by:

-

the challenge of locating the defect in the bladder

-

the technical difficulty in oversewing the bladder, which often must be done on the underside of the bladder, between the vaginal and bladder walls.

To tackle these challenges, an endoscopic approach promises improved visualization, and the robotic approach allows for surgical closure with improved visibility characteristic of endoscopy, while preserving the manual dexterity characteristic of open surgery.

Timing. It is believed that, in order to improve chances of successful surgical repair, the fistula should be approached either immediately (ie, within 1 to 2 weeks of the insult) or delayed by 8 to 12 or more weeks after the causative surgery.5

Preparation. Vesicovaginal fistulas can rarely involve the ureters, and this ureteric involvement needs to be ruled out. Accordingly, the workup of the VVF should begin with a thorough cystoscopic evaluation of the bladder, with retrograde pyelography to evaluate the integrity of the ureters bilaterally.

During this procedure, the location of the fistulous tract should be meticulously mapped. Care should be taken to document the location and extent of the fistula, as well as to identify the presence of multiple or separate tracts. If these tracts are present, they also need also to be catalogued. In my practice, the cystoscopy/retrograde pyelogram is performed as a separate surgical encounter.

Surgical technique

After the fistula is mapped and ureteric integrity is confirmed, the definitive surgical repair is performed. The steps to the surgical approach are straightforward.

1. Insert stents into the fistula and bilaterally into the ureters

Stenting the fistula permits rapid identification of the fistula tract without the need to enter the bladder separately. The ureteric stents you use should be one color, and the fistula stent should be a second color. I use 5 French yellow stents to cannulate the ureters and a 6 French blue stent for the fistula itself. Insert the fistula stent from the bladder side of the fistula. It should exit through the vagina (FIGURES 1A and 1B). In addition, place a 3-way Foley catheter for drainage and irrigate the bladder when indicated.

Figure 1. Stent insertion

Cystoscopically place a 6 French blue stent into the bladder side of the fistula. (A) The stent as seen from inside the bladder. (B) The stent as seen from the vaginal side.

2. Place the ports for optimal access

A 0° camera is adequate for visualization. Port placement is similar to that used for robotic sacral colpopexy; I use a supraumbilically placed camera port and three 8-mm robot ports (two on the left and one on the right of the umbilicus). Each port should be separated by about 10 cm. An assistant port is placed to the far right, for passing and retrieving sutures (FIGURE 2). An atraumatic grasper, monopolar scissors, and bipolar Maryland-type forceps are placed within the ports to begin the surgical procedure.

Figure 2. Ideal port placement

Place the camera port supraunbilically, with two 8-mm robot ports

3. Place a vaginal stent to aid dissection

The stent should be a sterile cylinder and have a diameter of 2 cm to 5 cm (to match the vaginal caliber). The tip should be rounded and flattened, with an extended handle available for manipulating the stent. The handle can be held by an assistant or attached to an external uterine positioning system (FIGURE 3); I use the Uterine Positioning SystemTM (Cooper Surgical, Trumbull, Connecticut).

4. Incise the vaginal cuff

Transversely incise the vaginal cuff with the monopolar scissors (VIDEO 1).

This allows entry into the vagina at the apex. The blue stent in the fistula should be visible at the anterior vaginal wall, as demonstrated in FIGURE 4.

5. Dissect the vaginal wall

Dissect the anterior vaginal wall down to the fistula, and dissect the bladder off of the vaginal wall for about 1.5 cm to 2 cm around the fistula tract (FIGURE 5 and VIDEO 2).

6. Cut the stent

Cut the stent passing thru the fistula, to move it out of the way.

7. Close the bladder

Stitch the bladder in a running fashion using three layers of 3-0 rapid absorbable synthetic suture (FIGURE 6 and Video 3 . I prefer polyglactin 910 (Vicryl; Ethicon, Somerville, New Jersey) because it is easier to handle.

FIGURE 6: Close the bladderStitch the bladder in a running fashion using three layers of 3-0 rapid absorbable synthetic suture. Keep the closure line free of tension.

8. Close the vaginal side of the fistula

Stitch the vaginal side of the fistula in a running fashion with 2-0 absorbable synthetic suture.

9. Verify closure

Check for watertight closure by retrofilling the bladder with 100 mL of sterile milk (obtained from the labor/delivery suite). Observe the suture line for any evidence of milk leakage. (Sterile milk does not stain the tissues, and this preserves tissue visibility. For this reason, milk is preferable to indigo carmine or methylene blue.)

10. Remove the stents from the bladder

Cystoscopically remove all stents.

11. Close the laparoscopic ports

12. Follow up to ensure surgical success

Leave the indwelling Foley catheter in place for 2 to 3 weeks. After such time, remove the catheter and perform voiding cystourethrogram to document bladder wall integrity.

Discussion

I have described a systematic approach to robotic VVF repair. The robotic portion of the procedure should require about 60 to 90 minutes in the absence of significant adhesions. The technique is amenable to a laparoscopic approach, when performed by an appropriately skilled operator.

Final takeaways. Important takeaways to this repair include:

- Stent the fistula to make it easy to find intraoperatively.

- Enter the vagina from above to rapidly locate the fistula tract.

- Use sterile milk to fill the bladder to look for leaks. This works without staining the tissues.

- Minimize tension on the bladder suture line.

In modern times in the United States, the vesicovaginal fistula (VVF) arises chiefly as a sequela of gynecologic surgery, usually hysterectomy. The injury most likely occurs at the time of dissection of the bladder flap off of the lower uterine segment and upper vagina.1 With increasing use of endoscopy and electrosurgery at the time of hysterectomy,2 the occurrence of VVF is likely to increase. Because of this, fistulas stemming from benign gynecologic surgical activity tend to occur above the trigone near the vaginal cuff.

Current technique of fistula repair involves either a vaginal approach, with the Latsko procedure,3 or an abdominal approach, involving a laparotomy; laparoscopy also is used with increasing frequency.4

Vaginal versus endoscopic approach. The vaginal approach can be straightforward, such as in cases of vault prolapse or a distally located fistula, or more difficult if the fistula is apical in location, especially if the apex is well suspended and the vagina is of normal length. I have found the abdominal approach to be optimal if the fistula is near the cuff and the vagina is of normal length and well suspended.

Classical teaching tells us that the first repair of the VVF is likely to be the most successful, with successively lower cure rates as the number of repair attempts increases. For this reason, I advocate the abdominal approach in most cases of apically placed VVFs.

Surgical approach

Why endoscopic, why robotic? Often, repair of the VVF is complicated by:

-

the challenge of locating the defect in the bladder

-

the technical difficulty in oversewing the bladder, which often must be done on the underside of the bladder, between the vaginal and bladder walls.

To tackle these challenges, an endoscopic approach promises improved visualization, and the robotic approach allows for surgical closure with improved visibility characteristic of endoscopy, while preserving the manual dexterity characteristic of open surgery.

Timing. It is believed that, in order to improve chances of successful surgical repair, the fistula should be approached either immediately (ie, within 1 to 2 weeks of the insult) or delayed by 8 to 12 or more weeks after the causative surgery.5

Preparation. Vesicovaginal fistulas can rarely involve the ureters, and this ureteric involvement needs to be ruled out. Accordingly, the workup of the VVF should begin with a thorough cystoscopic evaluation of the bladder, with retrograde pyelography to evaluate the integrity of the ureters bilaterally.

During this procedure, the location of the fistulous tract should be meticulously mapped. Care should be taken to document the location and extent of the fistula, as well as to identify the presence of multiple or separate tracts. If these tracts are present, they also need also to be catalogued. In my practice, the cystoscopy/retrograde pyelogram is performed as a separate surgical encounter.

Surgical technique

After the fistula is mapped and ureteric integrity is confirmed, the definitive surgical repair is performed. The steps to the surgical approach are straightforward.

1. Insert stents into the fistula and bilaterally into the ureters

Stenting the fistula permits rapid identification of the fistula tract without the need to enter the bladder separately. The ureteric stents you use should be one color, and the fistula stent should be a second color. I use 5 French yellow stents to cannulate the ureters and a 6 French blue stent for the fistula itself. Insert the fistula stent from the bladder side of the fistula. It should exit through the vagina (FIGURES 1A and 1B). In addition, place a 3-way Foley catheter for drainage and irrigate the bladder when indicated.

Figure 1. Stent insertion

Cystoscopically place a 6 French blue stent into the bladder side of the fistula. (A) The stent as seen from inside the bladder. (B) The stent as seen from the vaginal side.

2. Place the ports for optimal access

A 0° camera is adequate for visualization. Port placement is similar to that used for robotic sacral colpopexy; I use a supraumbilically placed camera port and three 8-mm robot ports (two on the left and one on the right of the umbilicus). Each port should be separated by about 10 cm. An assistant port is placed to the far right, for passing and retrieving sutures (FIGURE 2). An atraumatic grasper, monopolar scissors, and bipolar Maryland-type forceps are placed within the ports to begin the surgical procedure.

Figure 2. Ideal port placement

Place the camera port supraunbilically, with two 8-mm robot ports

3. Place a vaginal stent to aid dissection

The stent should be a sterile cylinder and have a diameter of 2 cm to 5 cm (to match the vaginal caliber). The tip should be rounded and flattened, with an extended handle available for manipulating the stent. The handle can be held by an assistant or attached to an external uterine positioning system (FIGURE 3); I use the Uterine Positioning SystemTM (Cooper Surgical, Trumbull, Connecticut).

4. Incise the vaginal cuff

Transversely incise the vaginal cuff with the monopolar scissors (VIDEO 1).

This allows entry into the vagina at the apex. The blue stent in the fistula should be visible at the anterior vaginal wall, as demonstrated in FIGURE 4.

5. Dissect the vaginal wall

Dissect the anterior vaginal wall down to the fistula, and dissect the bladder off of the vaginal wall for about 1.5 cm to 2 cm around the fistula tract (FIGURE 5 and VIDEO 2).

6. Cut the stent

Cut the stent passing thru the fistula, to move it out of the way.

7. Close the bladder

Stitch the bladder in a running fashion using three layers of 3-0 rapid absorbable synthetic suture (FIGURE 6 and Video 3 . I prefer polyglactin 910 (Vicryl; Ethicon, Somerville, New Jersey) because it is easier to handle.

FIGURE 6: Close the bladderStitch the bladder in a running fashion using three layers of 3-0 rapid absorbable synthetic suture. Keep the closure line free of tension.

8. Close the vaginal side of the fistula

Stitch the vaginal side of the fistula in a running fashion with 2-0 absorbable synthetic suture.

9. Verify closure

Check for watertight closure by retrofilling the bladder with 100 mL of sterile milk (obtained from the labor/delivery suite). Observe the suture line for any evidence of milk leakage. (Sterile milk does not stain the tissues, and this preserves tissue visibility. For this reason, milk is preferable to indigo carmine or methylene blue.)

10. Remove the stents from the bladder

Cystoscopically remove all stents.

11. Close the laparoscopic ports

12. Follow up to ensure surgical success

Leave the indwelling Foley catheter in place for 2 to 3 weeks. After such time, remove the catheter and perform voiding cystourethrogram to document bladder wall integrity.

Discussion

I have described a systematic approach to robotic VVF repair. The robotic portion of the procedure should require about 60 to 90 minutes in the absence of significant adhesions. The technique is amenable to a laparoscopic approach, when performed by an appropriately skilled operator.

Final takeaways. Important takeaways to this repair include:

- Stent the fistula to make it easy to find intraoperatively.

- Enter the vagina from above to rapidly locate the fistula tract.

- Use sterile milk to fill the bladder to look for leaks. This works without staining the tissues.

- Minimize tension on the bladder suture line.

Injury-free vaginal surgery: Case-based protective tactics

CASE 1 Gush of fluid during dissection

A 55-year-old woman with 2 prior cesarean deliveries and stage III uterovaginal prolapse (primarily apical) is now undergoing transvaginal hysterectomy and prolapse repair. During sharp dissection of the bladder off the lower uterine segment, a gush of clear fluid washes over the area of dissection.

What steps would you take to achieve the best possible clinical outcome for this woman?

If a patient sustains a urinary tract injury, she is 91 times more likely to sue her surgeon than a patient who has a different complication or problem at gynecologic surgery.1 Yet, despite a surgeon’s best efforts, injury can occur. If it does, the best approach is immediate recognition and repair.

Primary prevention—including identifying the ureters—and intraoperative repair is the easiest, most successful, least morbid approach, compared to postoperative management. And probably less likely to lead to a lawsuit.2

As always, our main goal in any preventive effort is the best possible patient care and clinical outcomes, and diligent, careful surgical technique is the best protection on all counts. Every vaginal surgeon should have a consistent strategy for preventing, indentifying and managing intraoperative injuries to the urinary tract and bowel.

This article discusses potential injuries to the lower genitourinary and gastrointestinal tracts separately.

Vulnerable anatomy is a given

The ureters are injured in up to 2.4% of vaginal surgeries,4 and gynecologic surgery accounts for as much as 52% of inadvertent ureteral injuries.5 The bladder and bowel can also sustain injuries, in up to 2.9% and 8% of cases, respectively.3,6

Mechanisms of injury can include bladder perforation7 (and, rarely, small bowel perforation8) during placement of bladder neck and midurethral slings, transection of the bladder or ureter during vaginal hysterectomy, and ureteral kinking or obstruction during vaginal hysterectomy and vault suspension.4,9

The rectum can sometimes be perforated during posterior colporrhaphy or perineorrhaphy.6

Risk factors

For intraoperative bladder injury: prior anterior colporrhaphy, cesarean delivery, or incontinence surgery.

For injury to the rectum: prior posterior vaginal wall surgery and defects in the distal rectovaginal septum.

For injury to the small bowel: enterocele.

Women with surgically induced or suspected congenital anatomic anomalies (eg, ureteral reimplantation, ectopic kidneys or ureters, suprapubic vascular bypass grafts) require evaluation to establish the location of these anatomic variants with respect to the planned area of surgical exploration.

Most gyn surgical injuries involve the urinary tract

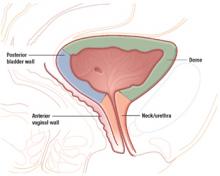

The urethra and a substantial portion of the posterior bladder rest on and are supported by the anterior vaginal wall. In women with an intact uterus, the posterior bladder wall also rests on the anterior lower uterine segment.

In women with a uterine scar, the bladder wall itself can sometimes be scarred down to the anterior lower uterine segment. This scarring occurs when the lower uterine scar becomes adherent to the posterior bladder wall during wound healing. Unrepaired or delayed repair to bladder injuries in these areas may lead to fistula formation.

Prior anterior colporrhaphy is associated with scarring between the bladder and anterior vaginal walls and can increase the risk of bladder injury during vaginal surgery.

Intraoperative injuries to the bladder dome and bladder neck are most common during urethral and bladder-neck sling procedures. During these procedures, prevent injury by keeping the passing tip of the sling-insertion device (eg, trocar or other passing instrument) clear of the urethra and bladder neck, and perform cystourethroscopy during each pass to identify any perforation of the bladder or urethra.

When perforation occurs, inspect the ureteral orifices thoroughly and document prompt efflux from both. If the orifices are freely effluxing and the remainder of the bladder mucosa is intact, withdraw the perforating instrument, pass it through again, and repeat cystoscopy to confirm that there is no new perforation.

Perforations to the bladder dome usually heal spontaneously in the postoperative period, with no need for extended bladder drainage. Perforations at the lateral or anterior bladder neck will also heal spontaneously.

Injuries to the posterior bladder wall and trigone

These injuries can occur during vaginal hysterectomy or dissection of the anterior vaginal wall (eg, anterior colporrhaphy, paravaginal defect repair). Avoid injuries by dissecting the vaginal mucosa (and lower uterine segment) carefully off the underlying endopelvic tissues.

Signs of an injury

Injury is often heralded by a gush of urine into the vaginal operative field, as in the opening case. When it occurs, determine the extent of injury from the vaginal side, and use a small Allis clamp to temporarily close the injury so that cystourethroscopy is effective. During cystoscopy, take steps to ascertain the extent of the injury and its proximity to the ureteral orifices.

Vaginal approach to intraoperative repair

Lacerations 2 cm or less in size are usually amenable to vaginal repair. In general, if the full extent of the laceration can be visually appreciated and accessed using the vaginal route, the repair can be safely attempted from the vaginal approach.

If the perforation is well away (>1 cm) from the ureteral orifices and there is free efflux from both orifices, close the defect from the vaginal side in 3 imbricating layers, being careful to keep the suture knots out of the bladder lumen.

Start by dissecting the overlying vaginal mucosa off the endopelvic fascia for 1 cm around the defect. This exposes the bladder adventitia, which can be used to reapproximate the laceration as follows:

Test the repair

Backfill the bladder transurethrally with 100 cc of sterile infant formula, and observe the result on the vaginal side. Closure should be watertight. Sterile formula does not stain the tissues and is therefore preferable to indigo carmine or methylene blue.

Reapproximate the vaginal mucosa using 2-0 Monocryl suture in a running, “nonlocked” fashion. Repeat cystoscopy after the closure to ensure prompt, free efflux from both ureteral orifices.

In nonradiated, well-perfused tissues, an interposing fat pad (eg, Martius or omental) is usually not required.

Foley catheter drainage is recommended to allow about 3 weeks of healing time for the closure.

If the laceration is less than 1 cm from a ureteral orifice

Assess the integrity of the affected ureter using a retrograde ureterogram performed under fluoroscopy. If ureteral integrity is confirmed, the affected ureter may be stented prior to repair of the laceration (as discussed above). Any stents may be left in place until the repair is judged to be sufficiently healed.

If the laceration is not fully visible or accessible vaginally

Use an abdominal approach—either open or laparoscopic—after assessing ureteral integrity. Focus on developing a suitable plane between the bladder and vaginal walls around the defect, followed by reapproximation of the bladder in 3 imbricating running layers of absorbable monofilament suture, as described above.

If the injury occurs during vaginal hysterectomy

In this situation, bladder closure can be deferred until the uterus and ovaries (if planned) have been removed.

For other procedures, such as anterior colporrhaphy, finish the procedure after the bladder is successfully closed. If the perforation is near or involves either ureteral orifice, it should be addressed in the manner of a ureteral injury (see below).

After fistula repairs

My patients undergo fluoroscopic evaluation of bladder filling and emptying at the 3-week mark, prior to Foley removal, to document functional closure. Then the Foley catheter and any indwelling stents are removed.

I counsel patients about the need to empty the bladder frequently, and how to recognize and avoid urinary retention.

Injuries to the ureters

The pelvic aspect of the ureters is also of interest to the gynecologic surgeon because these structures are at risk for obstruction or transection.

Vaginal procedures that can put the ureters at risk include vaginal vault (apical) suspensions and paravaginal defect repairs. Always include cystourethroscopy at the end of these procedures to document prompt and free efflux from both ureteral orifices.

3 “risky” regions

Because of its proximity to the vagina and uterus, the bladder is sometimes injured during vaginal surgery. Three areas are vulnerable: the dome and bladder neck/urethra, at risk during sling procedures, and the posterior bladder wall, vulnerable during dissection of the anterior vaginal wall.

If cystoscopy fails to confirm definitive bilateral efflux

Infuse intravenous indigo carmine and inspect the ureteral orifices again, in this situation. If bilateral efflux is not forthcoming, consider removing any intrapelvic packing, and take the patient out of the Trendelenburg position so that she can be observed for 20 minutes.

If there is still no efflux after that interval, a ureter may be obstructed.

If you suspect ureteral kinking or obstruction

Consider removing any suspensory sutures near the obstructed (noneffluxing) ureter. This maneuver usually results in vigorous efflux from the affected orifice.10 In the case of apical suspension sutures, remove the most lateral suture first and perform cystoscopy after each (more medial) suture is removed.4,9

If suture removal fails to bring about ureteral efflux, evaluate the ureters further by using intraoperative retrograde ureterogram (pyelogram) under fluoroscopy or by placing ureteral stents under cystoscopic guidance. Either method will localize the obstruction or kink and allow for targeted exploration and release of the stricture.

Extended bladder drainage is usually not required after intraoperative release of a partially or completely obstructed ureter.

In my practice, I remove any permanent suture I suspect is kinking or partially kinking a ureter. If the suture causing the problem is an absorbable one (eg, as in the use of Vicryl suture at colpocleisis), I may choose to follow the patient or to place a stent, and I reassure the woman that the offending suture will dissolve over time, thus relieving the partial obstruction.

If blue dye enters the field from inside the pelvis

The problem may be partial or complete ureteral transection. In this case, bladder perforation must first be ruled out cystoscopically. Then perform retrograde ureterogram under fluoroscopy to look for the possible point of leakage.

If ureteral transection is confirmed, plan for thorough surgical exploration (usually via the abdominal route) to locate and repair the injury.

For many generalists, this may require an intraoperative consult from a surgical service comfortable with the repair and/or reimplantation of the ureters.

CASE 1 OUTCOME

The bladder laceration was repaired after completion of the vaginal hysterectomy in the manner described above. There were no further sequelae.

It pays to refamiliarize yourself with the particular “landscape” of the lower urinary tract, so that sutures or scalpels don’t inadvertently block or injure structures.

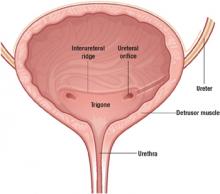

The smooth muscle of the bladder (detrusor) is lined with transitional mucosal epithelium and opens into the urethra at the bladder neck.

The ureters enter into the lateral aspects of the midposterior bladder and tunnel medially through the detrusor muscle before entering the bladder lumen at the level of the interureteral ridge. These entry points are known as the ureteral orifices.

The trigone is an area of the posterior bladder wall bounded by the bladder neck inferiorly and by the 2 ureteral orifices in the posterior midbladder.

Rectal injuries are usually easy to identify

As far as vaginal surgery is concerned, the lower GI tract consists of the rectum and external and internal anal sphincters. The distal rectum and posterior vaginal wall are usually closely applied to each other, separated by the rectovaginal septum (also called Denonvilliers fascia).

Risk factors

In women who have undergone posterior colporrhaphy or repair of a 4th degree tear, the posterior vaginal wall can be densely adherent to the rectum, putting the rectum at risk for injury during posterior vaginal wall dissection.

Most injuries to the rectum occur during dissection of the posterior vaginal wall. Fortunately, these injuries are readily recognized and easily repaired. If a rectal injury is suspected during or after dissection, a thorough intraoperative digital exam will help confirm or rule it out.

Repair of a rectal injury

Once an injury is identified, reapproximate the rectal mucosal edges with an imbricating closure using 3-0 Monocryl or other absorbable monofilament suture. A second imbricating layer should bring the rectal muscularis together, and the rectovaginal septum can then be closed over this layer in side-to-side or transverse fashion. Finally, close the vaginal mucosa after appropriate posterior colporrhaphy trimming. Such repairs heal well over time, without any long-term effects for the patient.

Prescribe a stool softener for the first 3 postoperative months to reduce the patient’s need to strain.

No bowel prep needed because injuries are rare

In my practice, the vast majority of vaginal surgical cases are accomplished without the need for preoperative bowel preparation. In the occasional patient known to have dense small-bowel adhesions involving the uterus, adnexae, or vaginal cuff, bowel prep may be appropriate if substantial dissection of the bowel is anticipated as part of the procedure.

CASE 2 Small bowel laceration

A 45-year-old woman with 4 prior vaginal deliveries, a 4th-degree obstetric rectovaginal laceration, and a history of laparoscopically assisted vaginal hysterectomy presents with stage III pelvic organ prolapse, primarily involving the posterior vaginal wall. An examination reveals a defect in the upper aspect of the posterior wall (an apical defect).

Intraoperatively, during sharp dissection to lift the posterior vaginal wall off the rectovaginal septum, a loop of small bowel descends into the field, and a 1-cm laceration occurs, exposing the lumen of the bowel.

How do you proceed?

On very rare occasions, a patient with an enterocele may sustain a small bowel injury during vaginal surgery. Such injury can usually be avoided by packing the small bowel away from the area of dissection and closely observing the dissection field.

Transvaginal repair

If the small bowel is cut during dissection, inspect the adjacent small bowel thoroughly to ascertain the extent of the injury. Transvaginal repair is recommended if the laceration and adjacent mesentery can be completely visualized and accessed through the vagina.

Small lacerations require a simple closure

If the laceration is small (1–2 cm) and does not involve the mesentery, irrigate it thoroughly and close it using a running imbricating 2-0 braided suture (eg, Vicryl or silk), with the suture line perpendicular to the long axis of the small bowel to decrease the risk of stricture. Inspect the suture line to ensure that it completely seals the laceration. Suture bites should incorporate the serosa and muscularis without transgressing the mucosa. Use a noncutting needle to place these sutures.

If the mesentery is involved in the laceration, make sure there are no bleeding vessels, and ligate any bleeding ones.

Large lacerations may necessitate abdominal surgery

An abdominal or laparoscopic procedure may be necessary to repair larger lacerations to the small bowel. If the surgeon is uncomfortable with bowel repair, it may be appropriate to obtain an intraoperative consult from a surgical service.

Postoperative monitoring

Watch for signs of ileus, which should be managed with bowel rest and nasogastric suction, as indicated.

CASE 2 OUTCOME

The small laceration was repaired with 2-0 Vicryl suture in the manner described above. The patient’s diet was advanced when bowel sounds returned. There were no further sequelae.

Generalists can manage most injuries

Incidental intraoperative injuries to the lower urinary and gastrointestinal tracts are relatively rare complications of vaginal surgery—but we must make every effort to anticipate, prevent, and promptly recognize such injuries.

If they do occur, pursue a course to thoroughly evaluate, repair, test, and provide appropriate followup for the patient. If promptly identified and addressed, these injuries can be made to resolve with minimal long-term sequelae. Appropriately timed intraoperative cystoscopy is a useful method for prompt intraoperative identification of bladder and ureteric injuries. Injuries identified intraoperatively can usually be repaired using simple techniques available to the general gynecologist.

The author reports no financial relationships relevant to this article

1. Gilmour DT, Baskett TF. Disability and litigation from urinary tract injuries at benign gynecologic surgery in Canada. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105:109-114.

2. Pettit PD, Petrou SP. The value of cystoscopy in major vaginal surgery. Obstet Gynecol. 1994;84:318-320.

3. Gilmour DT, Dwyer PL, Carey MP. Lower urinary tract injury during gynecologic surgery and its detection by intraoperative cystoscopy. Obstet Gynecol. 1999;94:883-889.

4. Karram M, Goldwasser S, Kleeman S, et al. High uterosacral vaginal vault suspension with fascial reconstruction for vaginal repair of enterocele and vaginal vault prolapse. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;185:1339-1342discussion 1342-1343.

5. Dowling RA, Corriere JN, Jr, Sandler CM. Iatrogenic ureteral injury. J Urol. 1986;135:912-915.

6. Mercer-Jones MA, Sprowson A, Varma JS. Outcome after transperineal mesh repair of rectocele: a case series. Dis Colon Rectum. 2004;47:864-868.

7. McLennan MT, Melick CF. Bladder perforation during tension-free vaginal tape procedures: analysis of learning curve and risk factors. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;106:1000-1004.

8. Leboeuf L, Tellez CA, Ead D, Gousse AE. Complication of bowel perforation during insertion of tension-free vaginal tape. J Urol. 2003;170:1310-discussion 1310-1311.

9. Shull BL, Bachofen C, Coates KW, Kuehl TJ. A transvaginal approach to repair of apical and other associated sites of pelvic organ prolapse with uterosacral ligaments. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;183:1365-1373discussion 1373-1374.

10. Harris RL, Cundiff GW, Theofrastous JP, et al. The value of intraoperative cystoscopy in urogynecologic and reconstructive pelvic surgery. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1997;177:1367-1369discussion 1369-1371.

CASE 1 Gush of fluid during dissection

A 55-year-old woman with 2 prior cesarean deliveries and stage III uterovaginal prolapse (primarily apical) is now undergoing transvaginal hysterectomy and prolapse repair. During sharp dissection of the bladder off the lower uterine segment, a gush of clear fluid washes over the area of dissection.

What steps would you take to achieve the best possible clinical outcome for this woman?

If a patient sustains a urinary tract injury, she is 91 times more likely to sue her surgeon than a patient who has a different complication or problem at gynecologic surgery.1 Yet, despite a surgeon’s best efforts, injury can occur. If it does, the best approach is immediate recognition and repair.

Primary prevention—including identifying the ureters—and intraoperative repair is the easiest, most successful, least morbid approach, compared to postoperative management. And probably less likely to lead to a lawsuit.2

As always, our main goal in any preventive effort is the best possible patient care and clinical outcomes, and diligent, careful surgical technique is the best protection on all counts. Every vaginal surgeon should have a consistent strategy for preventing, indentifying and managing intraoperative injuries to the urinary tract and bowel.

This article discusses potential injuries to the lower genitourinary and gastrointestinal tracts separately.

Vulnerable anatomy is a given

The ureters are injured in up to 2.4% of vaginal surgeries,4 and gynecologic surgery accounts for as much as 52% of inadvertent ureteral injuries.5 The bladder and bowel can also sustain injuries, in up to 2.9% and 8% of cases, respectively.3,6

Mechanisms of injury can include bladder perforation7 (and, rarely, small bowel perforation8) during placement of bladder neck and midurethral slings, transection of the bladder or ureter during vaginal hysterectomy, and ureteral kinking or obstruction during vaginal hysterectomy and vault suspension.4,9

The rectum can sometimes be perforated during posterior colporrhaphy or perineorrhaphy.6

Risk factors

For intraoperative bladder injury: prior anterior colporrhaphy, cesarean delivery, or incontinence surgery.

For injury to the rectum: prior posterior vaginal wall surgery and defects in the distal rectovaginal septum.

For injury to the small bowel: enterocele.

Women with surgically induced or suspected congenital anatomic anomalies (eg, ureteral reimplantation, ectopic kidneys or ureters, suprapubic vascular bypass grafts) require evaluation to establish the location of these anatomic variants with respect to the planned area of surgical exploration.

Most gyn surgical injuries involve the urinary tract

The urethra and a substantial portion of the posterior bladder rest on and are supported by the anterior vaginal wall. In women with an intact uterus, the posterior bladder wall also rests on the anterior lower uterine segment.

In women with a uterine scar, the bladder wall itself can sometimes be scarred down to the anterior lower uterine segment. This scarring occurs when the lower uterine scar becomes adherent to the posterior bladder wall during wound healing. Unrepaired or delayed repair to bladder injuries in these areas may lead to fistula formation.

Prior anterior colporrhaphy is associated with scarring between the bladder and anterior vaginal walls and can increase the risk of bladder injury during vaginal surgery.

Intraoperative injuries to the bladder dome and bladder neck are most common during urethral and bladder-neck sling procedures. During these procedures, prevent injury by keeping the passing tip of the sling-insertion device (eg, trocar or other passing instrument) clear of the urethra and bladder neck, and perform cystourethroscopy during each pass to identify any perforation of the bladder or urethra.

When perforation occurs, inspect the ureteral orifices thoroughly and document prompt efflux from both. If the orifices are freely effluxing and the remainder of the bladder mucosa is intact, withdraw the perforating instrument, pass it through again, and repeat cystoscopy to confirm that there is no new perforation.

Perforations to the bladder dome usually heal spontaneously in the postoperative period, with no need for extended bladder drainage. Perforations at the lateral or anterior bladder neck will also heal spontaneously.

Injuries to the posterior bladder wall and trigone

These injuries can occur during vaginal hysterectomy or dissection of the anterior vaginal wall (eg, anterior colporrhaphy, paravaginal defect repair). Avoid injuries by dissecting the vaginal mucosa (and lower uterine segment) carefully off the underlying endopelvic tissues.

Signs of an injury

Injury is often heralded by a gush of urine into the vaginal operative field, as in the opening case. When it occurs, determine the extent of injury from the vaginal side, and use a small Allis clamp to temporarily close the injury so that cystourethroscopy is effective. During cystoscopy, take steps to ascertain the extent of the injury and its proximity to the ureteral orifices.

Vaginal approach to intraoperative repair

Lacerations 2 cm or less in size are usually amenable to vaginal repair. In general, if the full extent of the laceration can be visually appreciated and accessed using the vaginal route, the repair can be safely attempted from the vaginal approach.

If the perforation is well away (>1 cm) from the ureteral orifices and there is free efflux from both orifices, close the defect from the vaginal side in 3 imbricating layers, being careful to keep the suture knots out of the bladder lumen.

Start by dissecting the overlying vaginal mucosa off the endopelvic fascia for 1 cm around the defect. This exposes the bladder adventitia, which can be used to reapproximate the laceration as follows:

Test the repair

Backfill the bladder transurethrally with 100 cc of sterile infant formula, and observe the result on the vaginal side. Closure should be watertight. Sterile formula does not stain the tissues and is therefore preferable to indigo carmine or methylene blue.

Reapproximate the vaginal mucosa using 2-0 Monocryl suture in a running, “nonlocked” fashion. Repeat cystoscopy after the closure to ensure prompt, free efflux from both ureteral orifices.

In nonradiated, well-perfused tissues, an interposing fat pad (eg, Martius or omental) is usually not required.

Foley catheter drainage is recommended to allow about 3 weeks of healing time for the closure.

If the laceration is less than 1 cm from a ureteral orifice

Assess the integrity of the affected ureter using a retrograde ureterogram performed under fluoroscopy. If ureteral integrity is confirmed, the affected ureter may be stented prior to repair of the laceration (as discussed above). Any stents may be left in place until the repair is judged to be sufficiently healed.

If the laceration is not fully visible or accessible vaginally

Use an abdominal approach—either open or laparoscopic—after assessing ureteral integrity. Focus on developing a suitable plane between the bladder and vaginal walls around the defect, followed by reapproximation of the bladder in 3 imbricating running layers of absorbable monofilament suture, as described above.

If the injury occurs during vaginal hysterectomy

In this situation, bladder closure can be deferred until the uterus and ovaries (if planned) have been removed.

For other procedures, such as anterior colporrhaphy, finish the procedure after the bladder is successfully closed. If the perforation is near or involves either ureteral orifice, it should be addressed in the manner of a ureteral injury (see below).

After fistula repairs

My patients undergo fluoroscopic evaluation of bladder filling and emptying at the 3-week mark, prior to Foley removal, to document functional closure. Then the Foley catheter and any indwelling stents are removed.

I counsel patients about the need to empty the bladder frequently, and how to recognize and avoid urinary retention.

Injuries to the ureters

The pelvic aspect of the ureters is also of interest to the gynecologic surgeon because these structures are at risk for obstruction or transection.

Vaginal procedures that can put the ureters at risk include vaginal vault (apical) suspensions and paravaginal defect repairs. Always include cystourethroscopy at the end of these procedures to document prompt and free efflux from both ureteral orifices.

3 “risky” regions

Because of its proximity to the vagina and uterus, the bladder is sometimes injured during vaginal surgery. Three areas are vulnerable: the dome and bladder neck/urethra, at risk during sling procedures, and the posterior bladder wall, vulnerable during dissection of the anterior vaginal wall.

If cystoscopy fails to confirm definitive bilateral efflux

Infuse intravenous indigo carmine and inspect the ureteral orifices again, in this situation. If bilateral efflux is not forthcoming, consider removing any intrapelvic packing, and take the patient out of the Trendelenburg position so that she can be observed for 20 minutes.

If there is still no efflux after that interval, a ureter may be obstructed.

If you suspect ureteral kinking or obstruction

Consider removing any suspensory sutures near the obstructed (noneffluxing) ureter. This maneuver usually results in vigorous efflux from the affected orifice.10 In the case of apical suspension sutures, remove the most lateral suture first and perform cystoscopy after each (more medial) suture is removed.4,9

If suture removal fails to bring about ureteral efflux, evaluate the ureters further by using intraoperative retrograde ureterogram (pyelogram) under fluoroscopy or by placing ureteral stents under cystoscopic guidance. Either method will localize the obstruction or kink and allow for targeted exploration and release of the stricture.

Extended bladder drainage is usually not required after intraoperative release of a partially or completely obstructed ureter.

In my practice, I remove any permanent suture I suspect is kinking or partially kinking a ureter. If the suture causing the problem is an absorbable one (eg, as in the use of Vicryl suture at colpocleisis), I may choose to follow the patient or to place a stent, and I reassure the woman that the offending suture will dissolve over time, thus relieving the partial obstruction.

If blue dye enters the field from inside the pelvis

The problem may be partial or complete ureteral transection. In this case, bladder perforation must first be ruled out cystoscopically. Then perform retrograde ureterogram under fluoroscopy to look for the possible point of leakage.

If ureteral transection is confirmed, plan for thorough surgical exploration (usually via the abdominal route) to locate and repair the injury.

For many generalists, this may require an intraoperative consult from a surgical service comfortable with the repair and/or reimplantation of the ureters.

CASE 1 OUTCOME

The bladder laceration was repaired after completion of the vaginal hysterectomy in the manner described above. There were no further sequelae.

It pays to refamiliarize yourself with the particular “landscape” of the lower urinary tract, so that sutures or scalpels don’t inadvertently block or injure structures.

The smooth muscle of the bladder (detrusor) is lined with transitional mucosal epithelium and opens into the urethra at the bladder neck.

The ureters enter into the lateral aspects of the midposterior bladder and tunnel medially through the detrusor muscle before entering the bladder lumen at the level of the interureteral ridge. These entry points are known as the ureteral orifices.

The trigone is an area of the posterior bladder wall bounded by the bladder neck inferiorly and by the 2 ureteral orifices in the posterior midbladder.

Rectal injuries are usually easy to identify

As far as vaginal surgery is concerned, the lower GI tract consists of the rectum and external and internal anal sphincters. The distal rectum and posterior vaginal wall are usually closely applied to each other, separated by the rectovaginal septum (also called Denonvilliers fascia).

Risk factors

In women who have undergone posterior colporrhaphy or repair of a 4th degree tear, the posterior vaginal wall can be densely adherent to the rectum, putting the rectum at risk for injury during posterior vaginal wall dissection.

Most injuries to the rectum occur during dissection of the posterior vaginal wall. Fortunately, these injuries are readily recognized and easily repaired. If a rectal injury is suspected during or after dissection, a thorough intraoperative digital exam will help confirm or rule it out.

Repair of a rectal injury

Once an injury is identified, reapproximate the rectal mucosal edges with an imbricating closure using 3-0 Monocryl or other absorbable monofilament suture. A second imbricating layer should bring the rectal muscularis together, and the rectovaginal septum can then be closed over this layer in side-to-side or transverse fashion. Finally, close the vaginal mucosa after appropriate posterior colporrhaphy trimming. Such repairs heal well over time, without any long-term effects for the patient.

Prescribe a stool softener for the first 3 postoperative months to reduce the patient’s need to strain.

No bowel prep needed because injuries are rare

In my practice, the vast majority of vaginal surgical cases are accomplished without the need for preoperative bowel preparation. In the occasional patient known to have dense small-bowel adhesions involving the uterus, adnexae, or vaginal cuff, bowel prep may be appropriate if substantial dissection of the bowel is anticipated as part of the procedure.

CASE 2 Small bowel laceration

A 45-year-old woman with 4 prior vaginal deliveries, a 4th-degree obstetric rectovaginal laceration, and a history of laparoscopically assisted vaginal hysterectomy presents with stage III pelvic organ prolapse, primarily involving the posterior vaginal wall. An examination reveals a defect in the upper aspect of the posterior wall (an apical defect).

Intraoperatively, during sharp dissection to lift the posterior vaginal wall off the rectovaginal septum, a loop of small bowel descends into the field, and a 1-cm laceration occurs, exposing the lumen of the bowel.

How do you proceed?

On very rare occasions, a patient with an enterocele may sustain a small bowel injury during vaginal surgery. Such injury can usually be avoided by packing the small bowel away from the area of dissection and closely observing the dissection field.

Transvaginal repair

If the small bowel is cut during dissection, inspect the adjacent small bowel thoroughly to ascertain the extent of the injury. Transvaginal repair is recommended if the laceration and adjacent mesentery can be completely visualized and accessed through the vagina.

Small lacerations require a simple closure

If the laceration is small (1–2 cm) and does not involve the mesentery, irrigate it thoroughly and close it using a running imbricating 2-0 braided suture (eg, Vicryl or silk), with the suture line perpendicular to the long axis of the small bowel to decrease the risk of stricture. Inspect the suture line to ensure that it completely seals the laceration. Suture bites should incorporate the serosa and muscularis without transgressing the mucosa. Use a noncutting needle to place these sutures.

If the mesentery is involved in the laceration, make sure there are no bleeding vessels, and ligate any bleeding ones.

Large lacerations may necessitate abdominal surgery

An abdominal or laparoscopic procedure may be necessary to repair larger lacerations to the small bowel. If the surgeon is uncomfortable with bowel repair, it may be appropriate to obtain an intraoperative consult from a surgical service.

Postoperative monitoring

Watch for signs of ileus, which should be managed with bowel rest and nasogastric suction, as indicated.

CASE 2 OUTCOME

The small laceration was repaired with 2-0 Vicryl suture in the manner described above. The patient’s diet was advanced when bowel sounds returned. There were no further sequelae.

Generalists can manage most injuries

Incidental intraoperative injuries to the lower urinary and gastrointestinal tracts are relatively rare complications of vaginal surgery—but we must make every effort to anticipate, prevent, and promptly recognize such injuries.

If they do occur, pursue a course to thoroughly evaluate, repair, test, and provide appropriate followup for the patient. If promptly identified and addressed, these injuries can be made to resolve with minimal long-term sequelae. Appropriately timed intraoperative cystoscopy is a useful method for prompt intraoperative identification of bladder and ureteric injuries. Injuries identified intraoperatively can usually be repaired using simple techniques available to the general gynecologist.

The author reports no financial relationships relevant to this article

CASE 1 Gush of fluid during dissection

A 55-year-old woman with 2 prior cesarean deliveries and stage III uterovaginal prolapse (primarily apical) is now undergoing transvaginal hysterectomy and prolapse repair. During sharp dissection of the bladder off the lower uterine segment, a gush of clear fluid washes over the area of dissection.

What steps would you take to achieve the best possible clinical outcome for this woman?

If a patient sustains a urinary tract injury, she is 91 times more likely to sue her surgeon than a patient who has a different complication or problem at gynecologic surgery.1 Yet, despite a surgeon’s best efforts, injury can occur. If it does, the best approach is immediate recognition and repair.

Primary prevention—including identifying the ureters—and intraoperative repair is the easiest, most successful, least morbid approach, compared to postoperative management. And probably less likely to lead to a lawsuit.2

As always, our main goal in any preventive effort is the best possible patient care and clinical outcomes, and diligent, careful surgical technique is the best protection on all counts. Every vaginal surgeon should have a consistent strategy for preventing, indentifying and managing intraoperative injuries to the urinary tract and bowel.

This article discusses potential injuries to the lower genitourinary and gastrointestinal tracts separately.

Vulnerable anatomy is a given

The ureters are injured in up to 2.4% of vaginal surgeries,4 and gynecologic surgery accounts for as much as 52% of inadvertent ureteral injuries.5 The bladder and bowel can also sustain injuries, in up to 2.9% and 8% of cases, respectively.3,6

Mechanisms of injury can include bladder perforation7 (and, rarely, small bowel perforation8) during placement of bladder neck and midurethral slings, transection of the bladder or ureter during vaginal hysterectomy, and ureteral kinking or obstruction during vaginal hysterectomy and vault suspension.4,9

The rectum can sometimes be perforated during posterior colporrhaphy or perineorrhaphy.6

Risk factors

For intraoperative bladder injury: prior anterior colporrhaphy, cesarean delivery, or incontinence surgery.

For injury to the rectum: prior posterior vaginal wall surgery and defects in the distal rectovaginal septum.

For injury to the small bowel: enterocele.

Women with surgically induced or suspected congenital anatomic anomalies (eg, ureteral reimplantation, ectopic kidneys or ureters, suprapubic vascular bypass grafts) require evaluation to establish the location of these anatomic variants with respect to the planned area of surgical exploration.

Most gyn surgical injuries involve the urinary tract

The urethra and a substantial portion of the posterior bladder rest on and are supported by the anterior vaginal wall. In women with an intact uterus, the posterior bladder wall also rests on the anterior lower uterine segment.

In women with a uterine scar, the bladder wall itself can sometimes be scarred down to the anterior lower uterine segment. This scarring occurs when the lower uterine scar becomes adherent to the posterior bladder wall during wound healing. Unrepaired or delayed repair to bladder injuries in these areas may lead to fistula formation.

Prior anterior colporrhaphy is associated with scarring between the bladder and anterior vaginal walls and can increase the risk of bladder injury during vaginal surgery.

Intraoperative injuries to the bladder dome and bladder neck are most common during urethral and bladder-neck sling procedures. During these procedures, prevent injury by keeping the passing tip of the sling-insertion device (eg, trocar or other passing instrument) clear of the urethra and bladder neck, and perform cystourethroscopy during each pass to identify any perforation of the bladder or urethra.

When perforation occurs, inspect the ureteral orifices thoroughly and document prompt efflux from both. If the orifices are freely effluxing and the remainder of the bladder mucosa is intact, withdraw the perforating instrument, pass it through again, and repeat cystoscopy to confirm that there is no new perforation.

Perforations to the bladder dome usually heal spontaneously in the postoperative period, with no need for extended bladder drainage. Perforations at the lateral or anterior bladder neck will also heal spontaneously.

Injuries to the posterior bladder wall and trigone

These injuries can occur during vaginal hysterectomy or dissection of the anterior vaginal wall (eg, anterior colporrhaphy, paravaginal defect repair). Avoid injuries by dissecting the vaginal mucosa (and lower uterine segment) carefully off the underlying endopelvic tissues.

Signs of an injury

Injury is often heralded by a gush of urine into the vaginal operative field, as in the opening case. When it occurs, determine the extent of injury from the vaginal side, and use a small Allis clamp to temporarily close the injury so that cystourethroscopy is effective. During cystoscopy, take steps to ascertain the extent of the injury and its proximity to the ureteral orifices.

Vaginal approach to intraoperative repair

Lacerations 2 cm or less in size are usually amenable to vaginal repair. In general, if the full extent of the laceration can be visually appreciated and accessed using the vaginal route, the repair can be safely attempted from the vaginal approach.

If the perforation is well away (>1 cm) from the ureteral orifices and there is free efflux from both orifices, close the defect from the vaginal side in 3 imbricating layers, being careful to keep the suture knots out of the bladder lumen.

Start by dissecting the overlying vaginal mucosa off the endopelvic fascia for 1 cm around the defect. This exposes the bladder adventitia, which can be used to reapproximate the laceration as follows:

Test the repair

Backfill the bladder transurethrally with 100 cc of sterile infant formula, and observe the result on the vaginal side. Closure should be watertight. Sterile formula does not stain the tissues and is therefore preferable to indigo carmine or methylene blue.

Reapproximate the vaginal mucosa using 2-0 Monocryl suture in a running, “nonlocked” fashion. Repeat cystoscopy after the closure to ensure prompt, free efflux from both ureteral orifices.

In nonradiated, well-perfused tissues, an interposing fat pad (eg, Martius or omental) is usually not required.

Foley catheter drainage is recommended to allow about 3 weeks of healing time for the closure.

If the laceration is less than 1 cm from a ureteral orifice

Assess the integrity of the affected ureter using a retrograde ureterogram performed under fluoroscopy. If ureteral integrity is confirmed, the affected ureter may be stented prior to repair of the laceration (as discussed above). Any stents may be left in place until the repair is judged to be sufficiently healed.

If the laceration is not fully visible or accessible vaginally

Use an abdominal approach—either open or laparoscopic—after assessing ureteral integrity. Focus on developing a suitable plane between the bladder and vaginal walls around the defect, followed by reapproximation of the bladder in 3 imbricating running layers of absorbable monofilament suture, as described above.

If the injury occurs during vaginal hysterectomy

In this situation, bladder closure can be deferred until the uterus and ovaries (if planned) have been removed.

For other procedures, such as anterior colporrhaphy, finish the procedure after the bladder is successfully closed. If the perforation is near or involves either ureteral orifice, it should be addressed in the manner of a ureteral injury (see below).

After fistula repairs

My patients undergo fluoroscopic evaluation of bladder filling and emptying at the 3-week mark, prior to Foley removal, to document functional closure. Then the Foley catheter and any indwelling stents are removed.

I counsel patients about the need to empty the bladder frequently, and how to recognize and avoid urinary retention.

Injuries to the ureters

The pelvic aspect of the ureters is also of interest to the gynecologic surgeon because these structures are at risk for obstruction or transection.

Vaginal procedures that can put the ureters at risk include vaginal vault (apical) suspensions and paravaginal defect repairs. Always include cystourethroscopy at the end of these procedures to document prompt and free efflux from both ureteral orifices.

3 “risky” regions

Because of its proximity to the vagina and uterus, the bladder is sometimes injured during vaginal surgery. Three areas are vulnerable: the dome and bladder neck/urethra, at risk during sling procedures, and the posterior bladder wall, vulnerable during dissection of the anterior vaginal wall.

If cystoscopy fails to confirm definitive bilateral efflux

Infuse intravenous indigo carmine and inspect the ureteral orifices again, in this situation. If bilateral efflux is not forthcoming, consider removing any intrapelvic packing, and take the patient out of the Trendelenburg position so that she can be observed for 20 minutes.

If there is still no efflux after that interval, a ureter may be obstructed.

If you suspect ureteral kinking or obstruction

Consider removing any suspensory sutures near the obstructed (noneffluxing) ureter. This maneuver usually results in vigorous efflux from the affected orifice.10 In the case of apical suspension sutures, remove the most lateral suture first and perform cystoscopy after each (more medial) suture is removed.4,9

If suture removal fails to bring about ureteral efflux, evaluate the ureters further by using intraoperative retrograde ureterogram (pyelogram) under fluoroscopy or by placing ureteral stents under cystoscopic guidance. Either method will localize the obstruction or kink and allow for targeted exploration and release of the stricture.

Extended bladder drainage is usually not required after intraoperative release of a partially or completely obstructed ureter.

In my practice, I remove any permanent suture I suspect is kinking or partially kinking a ureter. If the suture causing the problem is an absorbable one (eg, as in the use of Vicryl suture at colpocleisis), I may choose to follow the patient or to place a stent, and I reassure the woman that the offending suture will dissolve over time, thus relieving the partial obstruction.

If blue dye enters the field from inside the pelvis

The problem may be partial or complete ureteral transection. In this case, bladder perforation must first be ruled out cystoscopically. Then perform retrograde ureterogram under fluoroscopy to look for the possible point of leakage.

If ureteral transection is confirmed, plan for thorough surgical exploration (usually via the abdominal route) to locate and repair the injury.

For many generalists, this may require an intraoperative consult from a surgical service comfortable with the repair and/or reimplantation of the ureters.

CASE 1 OUTCOME

The bladder laceration was repaired after completion of the vaginal hysterectomy in the manner described above. There were no further sequelae.

It pays to refamiliarize yourself with the particular “landscape” of the lower urinary tract, so that sutures or scalpels don’t inadvertently block or injure structures.

The smooth muscle of the bladder (detrusor) is lined with transitional mucosal epithelium and opens into the urethra at the bladder neck.

The ureters enter into the lateral aspects of the midposterior bladder and tunnel medially through the detrusor muscle before entering the bladder lumen at the level of the interureteral ridge. These entry points are known as the ureteral orifices.

The trigone is an area of the posterior bladder wall bounded by the bladder neck inferiorly and by the 2 ureteral orifices in the posterior midbladder.

Rectal injuries are usually easy to identify

As far as vaginal surgery is concerned, the lower GI tract consists of the rectum and external and internal anal sphincters. The distal rectum and posterior vaginal wall are usually closely applied to each other, separated by the rectovaginal septum (also called Denonvilliers fascia).

Risk factors

In women who have undergone posterior colporrhaphy or repair of a 4th degree tear, the posterior vaginal wall can be densely adherent to the rectum, putting the rectum at risk for injury during posterior vaginal wall dissection.

Most injuries to the rectum occur during dissection of the posterior vaginal wall. Fortunately, these injuries are readily recognized and easily repaired. If a rectal injury is suspected during or after dissection, a thorough intraoperative digital exam will help confirm or rule it out.

Repair of a rectal injury

Once an injury is identified, reapproximate the rectal mucosal edges with an imbricating closure using 3-0 Monocryl or other absorbable monofilament suture. A second imbricating layer should bring the rectal muscularis together, and the rectovaginal septum can then be closed over this layer in side-to-side or transverse fashion. Finally, close the vaginal mucosa after appropriate posterior colporrhaphy trimming. Such repairs heal well over time, without any long-term effects for the patient.

Prescribe a stool softener for the first 3 postoperative months to reduce the patient’s need to strain.

No bowel prep needed because injuries are rare

In my practice, the vast majority of vaginal surgical cases are accomplished without the need for preoperative bowel preparation. In the occasional patient known to have dense small-bowel adhesions involving the uterus, adnexae, or vaginal cuff, bowel prep may be appropriate if substantial dissection of the bowel is anticipated as part of the procedure.

CASE 2 Small bowel laceration

A 45-year-old woman with 4 prior vaginal deliveries, a 4th-degree obstetric rectovaginal laceration, and a history of laparoscopically assisted vaginal hysterectomy presents with stage III pelvic organ prolapse, primarily involving the posterior vaginal wall. An examination reveals a defect in the upper aspect of the posterior wall (an apical defect).

Intraoperatively, during sharp dissection to lift the posterior vaginal wall off the rectovaginal septum, a loop of small bowel descends into the field, and a 1-cm laceration occurs, exposing the lumen of the bowel.

How do you proceed?

On very rare occasions, a patient with an enterocele may sustain a small bowel injury during vaginal surgery. Such injury can usually be avoided by packing the small bowel away from the area of dissection and closely observing the dissection field.

Transvaginal repair

If the small bowel is cut during dissection, inspect the adjacent small bowel thoroughly to ascertain the extent of the injury. Transvaginal repair is recommended if the laceration and adjacent mesentery can be completely visualized and accessed through the vagina.

Small lacerations require a simple closure

If the laceration is small (1–2 cm) and does not involve the mesentery, irrigate it thoroughly and close it using a running imbricating 2-0 braided suture (eg, Vicryl or silk), with the suture line perpendicular to the long axis of the small bowel to decrease the risk of stricture. Inspect the suture line to ensure that it completely seals the laceration. Suture bites should incorporate the serosa and muscularis without transgressing the mucosa. Use a noncutting needle to place these sutures.

If the mesentery is involved in the laceration, make sure there are no bleeding vessels, and ligate any bleeding ones.

Large lacerations may necessitate abdominal surgery

An abdominal or laparoscopic procedure may be necessary to repair larger lacerations to the small bowel. If the surgeon is uncomfortable with bowel repair, it may be appropriate to obtain an intraoperative consult from a surgical service.

Postoperative monitoring

Watch for signs of ileus, which should be managed with bowel rest and nasogastric suction, as indicated.

CASE 2 OUTCOME

The small laceration was repaired with 2-0 Vicryl suture in the manner described above. The patient’s diet was advanced when bowel sounds returned. There were no further sequelae.

Generalists can manage most injuries

Incidental intraoperative injuries to the lower urinary and gastrointestinal tracts are relatively rare complications of vaginal surgery—but we must make every effort to anticipate, prevent, and promptly recognize such injuries.

If they do occur, pursue a course to thoroughly evaluate, repair, test, and provide appropriate followup for the patient. If promptly identified and addressed, these injuries can be made to resolve with minimal long-term sequelae. Appropriately timed intraoperative cystoscopy is a useful method for prompt intraoperative identification of bladder and ureteric injuries. Injuries identified intraoperatively can usually be repaired using simple techniques available to the general gynecologist.

The author reports no financial relationships relevant to this article

1. Gilmour DT, Baskett TF. Disability and litigation from urinary tract injuries at benign gynecologic surgery in Canada. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105:109-114.

2. Pettit PD, Petrou SP. The value of cystoscopy in major vaginal surgery. Obstet Gynecol. 1994;84:318-320.

3. Gilmour DT, Dwyer PL, Carey MP. Lower urinary tract injury during gynecologic surgery and its detection by intraoperative cystoscopy. Obstet Gynecol. 1999;94:883-889.

4. Karram M, Goldwasser S, Kleeman S, et al. High uterosacral vaginal vault suspension with fascial reconstruction for vaginal repair of enterocele and vaginal vault prolapse. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;185:1339-1342discussion 1342-1343.

5. Dowling RA, Corriere JN, Jr, Sandler CM. Iatrogenic ureteral injury. J Urol. 1986;135:912-915.

6. Mercer-Jones MA, Sprowson A, Varma JS. Outcome after transperineal mesh repair of rectocele: a case series. Dis Colon Rectum. 2004;47:864-868.

7. McLennan MT, Melick CF. Bladder perforation during tension-free vaginal tape procedures: analysis of learning curve and risk factors. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;106:1000-1004.

8. Leboeuf L, Tellez CA, Ead D, Gousse AE. Complication of bowel perforation during insertion of tension-free vaginal tape. J Urol. 2003;170:1310-discussion 1310-1311.

9. Shull BL, Bachofen C, Coates KW, Kuehl TJ. A transvaginal approach to repair of apical and other associated sites of pelvic organ prolapse with uterosacral ligaments. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;183:1365-1373discussion 1373-1374.

10. Harris RL, Cundiff GW, Theofrastous JP, et al. The value of intraoperative cystoscopy in urogynecologic and reconstructive pelvic surgery. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1997;177:1367-1369discussion 1369-1371.

1. Gilmour DT, Baskett TF. Disability and litigation from urinary tract injuries at benign gynecologic surgery in Canada. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105:109-114.

2. Pettit PD, Petrou SP. The value of cystoscopy in major vaginal surgery. Obstet Gynecol. 1994;84:318-320.

3. Gilmour DT, Dwyer PL, Carey MP. Lower urinary tract injury during gynecologic surgery and its detection by intraoperative cystoscopy. Obstet Gynecol. 1999;94:883-889.