User login

Face‐to‐Face Handoffs and Outcomes

Handoffs are key events in the care of hospitalized patients whereby vital information is relayed between healthcare providers. Resident duty hour restrictions and the popularity of shift‐based work schedules have increased the frequency of inpatient handoffs.[1, 2] Failures in communication at the time of patient handoff have been implicated as contributing factors to preventable adverse events.[3, 4, 5, 6] With patient safety in mind, accreditation organizations and professional societies have made the standardization of hospital handoff procedures a priority.[7, 8] A variety of strategies have been utilized to standardize handoffs. Examples include the use of mnemonics,[9] electronic resources,[10, 11, 12] preformatted handoff sheets,[13, 14, 15, 16] and optimization of the handoff environment.[17] The primary outcomes for many of these studies center on the provider by measuring their retention of patient facts[18, 19] and completion of tasks[14, 16] after handoff, for example. Few studies examined patient‐centered outcomes such as transfer to a higher level of care,[20] length of stay,[11] mortality,[21] or readmission rate.[22] A study in the pediatric population found that implementation of a handoff bundle was associated with a decrease in medical errors and preventable adverse events.[23]

The Society of Hospital Medicine recommends that patient handoffs consist of both a written and verbal component.[8] Providers in our division work on 3 shifts: day, evening, and night. In 2009, we developed a face‐to‐face morning handoff, during which night‐shift providers hand off patient care to day‐shift providers incorporating an electronically generated service information list.[17] Given that the evening shift ends well before the day shift begins, the evening‐shift providers do not participate in this face‐to‐face handoff of care for patients they admit to day providers.

We wished to compare the clinical outcomes and adverse events of patients admitted by the night‐shift providers to those admitted by the evening‐shift providers. We hypothesized that transfer of care using a face‐to‐face handoff would be associated with fewer adverse events and improved clinical outcomes.

METHODS

The study was deemed exempt by the Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board.

Study Population

Hospitalists at the study institution, a 1157‐bed academic tertiary referral hospital, admit general medical patients from the emergency department, as transfers from other institutions, and as direct admissions from outpatient offices. Patients included in the study were all adults admitted by evening‐ and night‐shift hospitalists from August 1, 2011 through August 1, 2012 between 6:45 pm and midnight. Our institution primarily uses 2 levels of care for adult inpatients on internal medicine services, including a general care floor for low‐acuity patients and an intensive care unit for high‐acuity patients. All of the patients in this study were triaged as low acuity at the time of admission and were initially admitted to general care units.

Setting

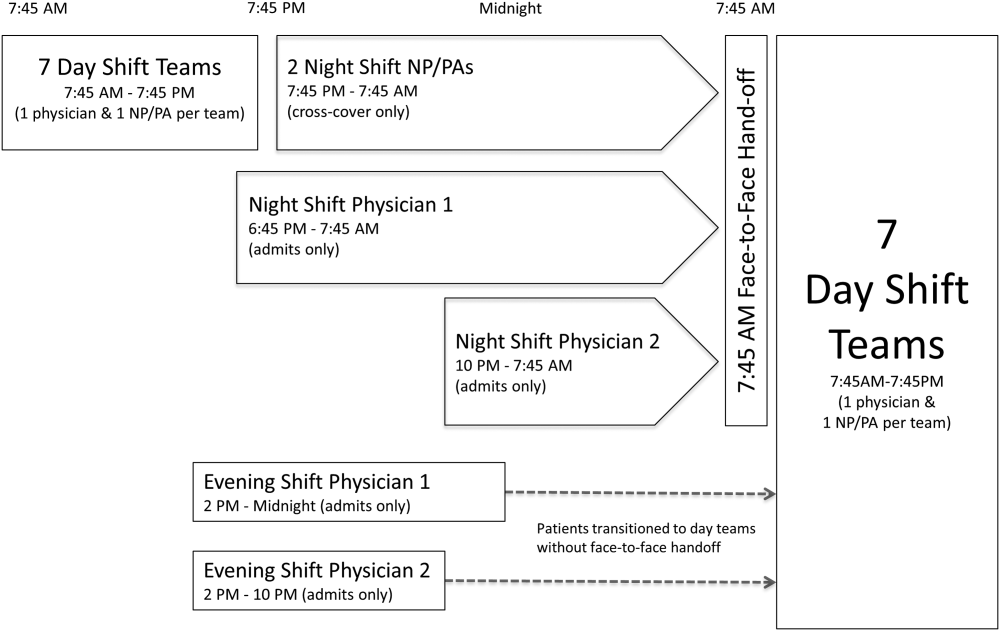

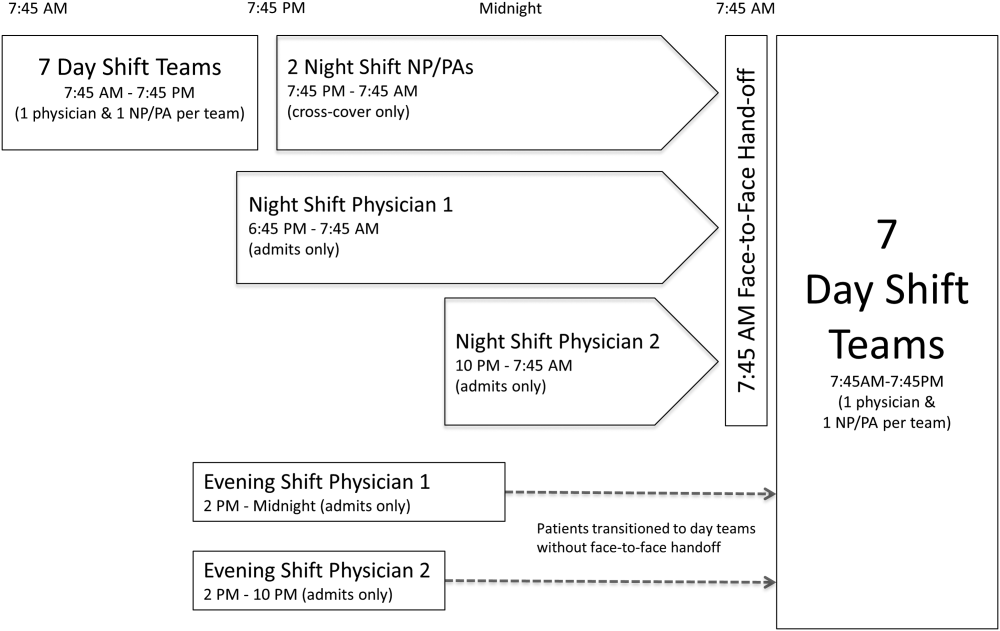

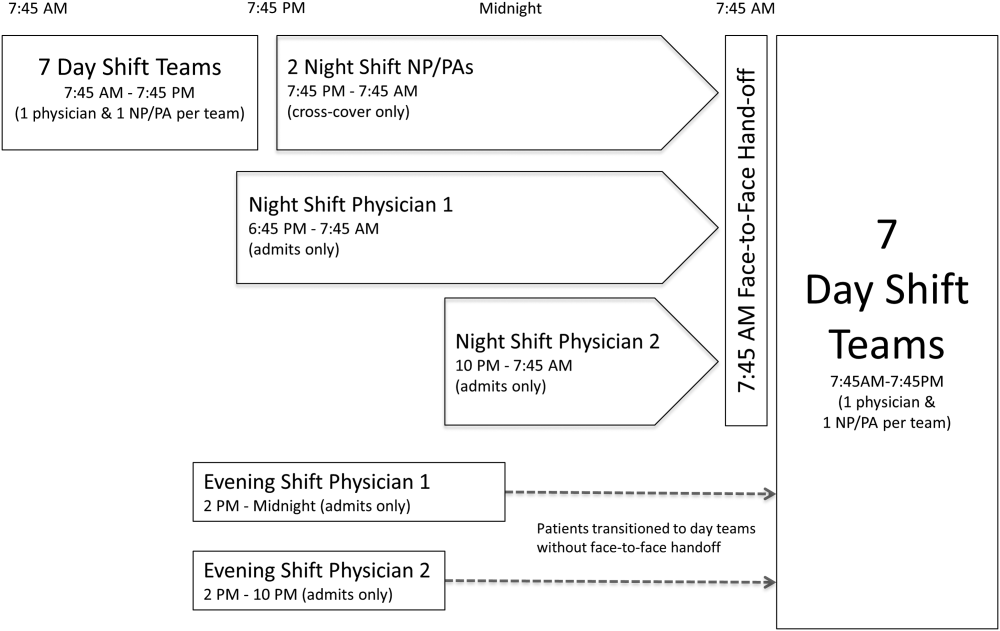

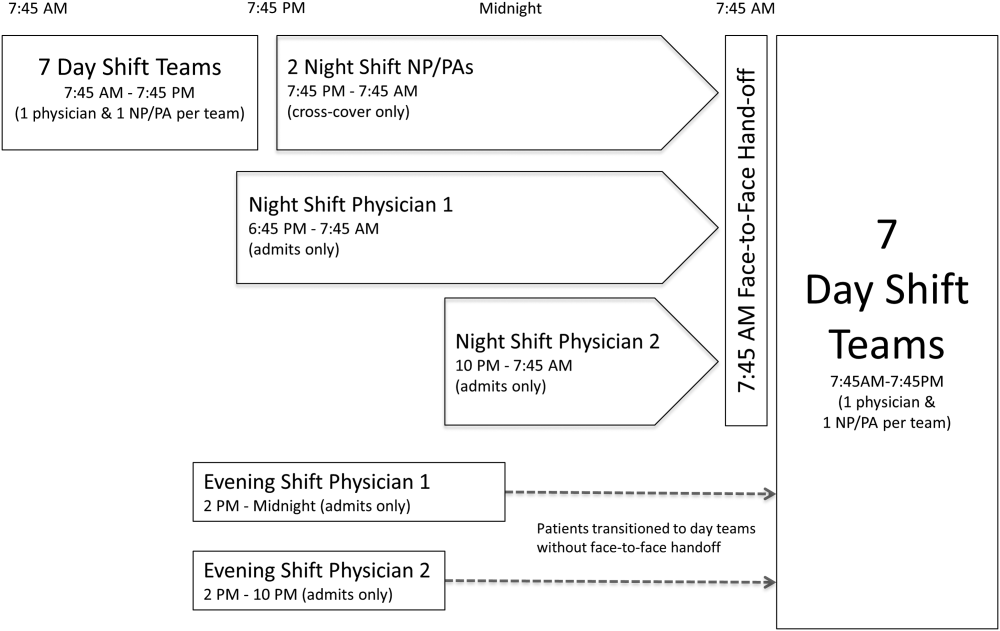

The division's shift schedule during the study period is depicted in Figure 1. Day‐shift providers included a physician and nurse practitioner (NP) or physician assistant (PA) on each of 7 teams. Each service had an average daily patient census between 10 and 15 patients with 3 to 4 new admissions every 24 hours, with 1 to 2 of these admissions occurring during the evening and night shifts, on average. The day shift started at 7:45 am and ended at 7:45 pm, at which time the day teams transitioned care of their patients to 1 of 2 overnight NP/PAs who provided cross‐cover for all teams through the night. The overnight NP/PAs then transitioned care back to the day teams at 7:45 am the following morning.

Two evening‐shift providers, both physicians, including a staff hospitalist and a hospital medicine fellowship trainee, admitted patients without any cross‐cover responsibility. Their shifts had the same start time, but staggered end times (2 pm10 pm and 2 pmmidnight). At the end of their shifts, the evening‐shift providers relayed concerns or items for follow‐up to the night cross‐cover NP/PAs; however, this handoff was nonstandardized and provider dependent. The cross‐cover providers could also choose to pass on any relevant information to day‐shift providers if thought to be necessary, but this, again, was not required or standardized. A printed electronic handoff tool (including the patient's problem list, medications, vital signs, laboratory results, and to do list as determined by the admitting provider) as well as all clinical notes generated since admission were made available to day‐shift providers who assumed care at 7:45 am; however, there was no face‐to‐face handoff between the evening‐ and day‐shift providers.

Two night‐shift physicians, including a moonlighting board‐eligible internal medicine physician and staff hospitalist, also started at staggered times, 6:45 pm and 10 pm, but their shifts both ended at 7:45 am. These physicians also admitted patients without cross‐cover responsibilities. At 7:45 am, in a face‐to‐face meeting, they transitioned care of patients admitted overnight to day‐shift providers. This handoff occurred at a predesignated place with assigned start times for each team. During the meeting, printed electronic documents, including the aforementioned electronic handoff tool as well as all clinical notes generated since admission, were made available to the oncoming day‐shift providers. The face‐to‐face interaction between night‐ and day‐shift providers lasted approximately 5 minutes and allowed for a brief presentation of the patient, review of the diagnostic testing and treatments performed so far, as well as anticipatory guidance regarding potential issues throughout the remainder of the hospitalization. Although inclusion of the above components was encouraged during the face‐to‐face handoff, the interaction was not scripted and topics discussed were at the providers' discretion.

Patients admitted during the evening and night shifts were assigned to day‐shift services primarily based on the current census of each team, so as to distribute the workload evenly.

Chart Review

Patients included in the study were admitted by evening‐ or night‐shift providers between 6:45 pm and midnight. This time period accounts for when the evening shift and night shift overlap, allowing for direct comparison of patients admitted during the same time of day, so as to avoid confounding factors. Patients were grouped by whether they were admitted by an evening‐shift provider or a night‐shift provider. Each study patient's chart was retrospectively reviewed and relevant demographic and clinical data were collected. Demographic information included age, gender, and race. Clinical information included medical comorbidities, Charlson Comorbidity Index score, rapid response team calls, code team calls, transfers to a higher level of care, death in hospital, 30‐day readmission rate, length of stay (LOS), and adverse events. The Charlson Comorbidity Index score[24] was determined from diagnoses in the institution's medical index database. The 30‐day readmission rate included observation stays and full hospital admissions that occurred at our institution in the 30 days following the patient's hospital discharge from the index admission. LOS was determined based on the time of admission and discharge, as reported in the hospital billing system, and is reported as the median and mean LOS in hours for all patients in each group.

The Global Trigger Tool (GTT) was used to identify adverse events, as defined within the GTT whitepaper to be unintended physical injury resulting from or contributed to by medical care that requires additional monitoring, treatment or hospitalization, or that results in death.[25] Developed by the Institute for Healthcare Improvement, the GTT uses triggers, clues in the medical record that suggest an adverse event may have occurred, to cue a more detailed chart review. Registered nurses trained in use of the GTT reviewed all of the included patients' electronic medical records. If a trigger was identified (such as a patient fall suffered in the hospital), further chart review was prompted to determine if patient harm occurred. If there was evidence of harm, an adverse event was determined to have occurred and was then categorized using the National Coordinating Council for Medication Error Reporting and Prevention Index for Categorizing Errors.[26] For example, in the case of a patient fall whereby the patient was determined to have fallen in the hospital and suffered a laceration requiring wound care, but the hospital stay was not prolonged, this adverse event was categorized as category E (an adverse event that caused the patient temporary harm necessitating intervention, without prolongation of the hospital stay).

Outcomes including rapid response team calls, code team calls, transfers to a higher level of care, death in the hospital, and adverse events, as identified using the GTT, were counted if they occurred between 7:45 am on the first morning of admission until 12 hours later at 7:45 pm, at the time of the first evening handoff of the admitted patients' care.

Statistical Methods

Study data were collected and managed using REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture) electronic data capture tools hosted at Mayo Clinic.[27] When comparing outcomes between the 2 groups, Fisher exact test was used for categorical variables and Student t test was used for continuous variables. Global Trigger Tool data were analyzed using the SAS GENMOD procedure, assuming a negative binomial distribution. All the above analyses were performed using SAS version 9.3 software (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). Rates of adverse events were compared using MedCalc version 13 software (MedCalc Software, Ostend, Belgium).[28] A P value <0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

Of 805 patients admitted between 6:45 pm and midnight during the study period, 305 (37.9%) patients were handed off to day‐shift providers without face‐to‐face handoff, and 500 (62.1%) patients were transferred to the care of day‐shift providers with the use of a face‐to‐face handoff.

Baseline characteristics of both groups are depicted in Table 1. Demographic characteristics, including age, gender, and race, were not significantly different between groups. The mean Charlson Comorbidity Index score was not significantly different between the groups without and with a face‐to‐face handoff. In addition, the presence of medical comorbidities including type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertension, coronary artery disease, hyperlipidemia, heart failure, body mass index (BMI) <18, active cancer, and current cigarette smoking were not significantly different between the 2 groups. There was a trend to a significantly increased proportion of patients with a BMI >30 in the group without face‐to‐face handoff (P=0.05).

| Without Face‐to‐Face Handoff, N=305 | With Face‐to‐Face Handoff, N=500 | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Age, y, mean (SD) | 65.8 (19.0) | 64.2 (20.0) | 0.25 |

| Sex, n (%) | 0.69 | ||

| Female | 166 (54%) | 265 (53%) | |

| Male | 139 (46%) | 235 (47%) | |

| Race, n (%) | 0.94 | ||

| White | 287 (95%) | 466 (93%) | |

| African American | 5 (2%) | 9 (2%) | |

| Arab/Middle Eastern | 3 (1%) | 8 (2%) | |

| Asian | 1 (0%) | 3 (1%) | |

| Indian subcontinental | 1 (0%) | 1 (0%) | |

| American Indian/Alaskan | 1 (0%) | 1 (0%) | |

| Other | 3 (1%) | 8 (2%) | |

| Unknown | 1 (0%) | 4 (1%) | |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index, mean ( SD) | 2.98 ( 3.73) | 2.93 ( 3.72) | 0.85 |

| Comorbidities, n (%) | |||

| Type 2 diabetes | 82 (27%) | 143 (29%) | 0.60 |

| Hypertension | 195 (64%) | 303 (61%) | 0.34 |

| Coronary artery disease | 76 (25%) | 137 (27%) | 0.44 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 122 (40%) | 206 (41%) | 0.74 |

| Heart failure | 30 (10%) | 66 (13%) | 0.15 |

| BMI >30 | 109 (36%) | 146 (29%) | 0.05 |

| BMI <18 | 7 (2%) | 12 (2%) | 0.92 |

| Active cancer | 29 (10%) | 46 (9%) | 0.88 |

| Current smoker | 49 (16%) | 90 (18%) | 0.48 |

Results for the outcomes of this study are depicted in Table 2. The frequency of rapid response team calls, code team calls, transfers to a higher level of care, and death in the hospital in the 12 hours following the first morning handoff of the admission were not significantly different between the 2 groups. Both 30‐day readmission rate and LOS (median and mean) were not significantly different between groups.

| Without Face‐to‐Face Handoff, N=305 | With Face‐to‐Face Handoff, N=500 | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Rapid response team call, n (%) | 4 (1%) | 5 (1%) | 0.68 |

| Code team call, n (%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (0%) | 0.43 |

| Transfer to higher level of care, n (%) | 7 (2%) | 11 (2%) | 0.93 |

| Patient death, n (%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1.00 |

| 30‐day readmission, n (%) | 50 (16%) | 67 (13%) | 0.23 |

| Hospital length of stay | |||

| Median, h (IQR) | 66.5 (41.3115.6) | 70.3 (41.9131.2) | 0.30 |

| Mean, h ( SD) | 102.0 ( 110.0) | 102.9 ( 94.0) | 0.90 |

| Adverse events (Global Trigger Tool) | |||

| Temporary harm and required intervention (E) | 4 | 7 | 0.92 |

| Temporary harm and required initial or prolonged hospitalization (F) | 7 | 8 | 0.53 |

| Permanent harm (G) | 0 | 1 | 0.44 |

| Intervention required to sustain life (H) | 0 | 6 | 0.14 |

| Death (I) | 0 | 0 | 1.00 |

| Total adverse events per 100 admissions | 3.61 | 4.40 | 0.59 |

| % of admissions with an adverse event | 2.6% | 3.2% | 0.64 |

There was no significant difference between the 2 groups in the frequency of adverse events resulting in harm for any of the categories (categories EI). Total adverse events between groups were also compared. Adverse events per 100 admissions were not significantly different between the group without face‐to‐face handoff compared to the group with face‐to‐face handoff. The percentage of admissions with an adverse event was also similar between groups.

DISCUSSION

We found no significant difference in the rate of rapid response team calls, code team calls, transfers to a higher level of care, death in hospital, or adverse events when comparing patients transitioned to the care of day‐shift providers with or without a face‐to‐face handoff. We hypothesize that a reason adverse events were no different between the 2 groups may be that providers were more vigilant when they did not receive a face‐to‐face handoff from the previous provider. As a result, providers may have dedicated additional time reviewing the medical record, speaking with the patients, and communicating with other healthcare providers to ensure a safe care transition. Similarly, other studies found no significant reduction in adverse events when using a standardized handoff.[10, 13, 29] This may be because patient handoff is 1 of a multitude of factors that impact the rate of adverse events, and a handoff may play a less vital role in a system where documentation of care for a given patient is readily accessible, uniform, and detailed. A face‐to‐face interaction itself in a patient handoff may be less pertinent if key information can be communicated through other channels, such as an electronic handoff tool, email, or phone.

Another potential explanation for the lack of a significant difference in patient outcomes with and without a face‐to‐face handoff is related to the study design and inherent rate of the events measured. With the exception of 30‐day readmission rate and LOS, the outcomes of the study were recorded only if they occurred in the 12 hours following the first morning handoff of the admission. This was done in an attempt to isolate the effect of the nonface‐to‐face versus face‐to‐face handoff on the first morning of the admission, and to avoid confounding effects by subsequent transitions of care later in the hospitalization. The frequency of hospital admissions in which an adverse event occurred during this relatively short 12‐hour window was approximately 3% for all patients in the study. With 805 total patients in the study, there may have been insufficient statistical power to detect a difference in the rate of outcomes, if a difference did exist, considering the event rate for both groups and the sample size.

There are several additional limitations to our study. First, the GTT was designed to be applied across the entirety of a hospitalization. By screening for adverse events over the span of only 12 hours for each hospitalization, the sensitivity of the tool may have been diminished, with a proportion of adverse events not captured, even when the sequence of events leading to patient harm began during the 12 hours in question. Second, this is a retrospective study, and all adverse events may not be documented in the medical record. Third, although not formally structured and infrequent, some evening‐shift providers did send an email or call the oncoming day‐shift provider to discuss patients admitted. This process, however, was provider dependent, unstructured, uncommon, and erratic, and thus we were not able to capture it from medical record review. Finally, the patients in this study were deemed low acuity upon triage prior to admission. A face‐to‐face handoff may be less important in ensuring patient safety when caring for low‐acuity compared to high‐acuity patients, considering the rapidity at which the critically ill can deteriorate.

Handoffs of patient care in the hospital have certainly increased in recent years. Consequently, communication among providers is undoubtedly important, with patient safety being the primary goal. Our work suggests that a face‐to‐face component of a handoff is not vital to ensure a safe care transition. Because of the increasing frequency of handoffs, providers' ability to do so face‐to‐face will likely be challenged by time and logistical constraints. Future work is needed to delineate the most effective components of the handoff so that we can design information transfer that promotes safe and efficient care, even without a face‐to‐face interaction.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful for support from the Mayo Clinic Department of Medicine Clinical Research Office, Ms. Donna Lawson, and Mr. Stephen Cha.

Disclosures: This publication was made possible by the Mayo Clinic Center for Clinical and Translational Science through grant number UL1 TR000135 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Science, a component of the National Institutes of Health. The authors report no conflicts of interest.

- , , , et al. Effect of the 2011 vs 2003 duty hour regulation‐compliant models on sleep duration, trainee education, and continuity of patient care among internal medicine house staff: a randomized trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(8):649–655.

- . 'Shift work': 24‐hour workdays are out as residents, hospitals deal with changes, mixed feelings on restrictions. Mod Healthc. 2011;41(30):6–7, 16, 1.

- , , , , . Consequences of inadequate sign‐out for patient care. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(16):1755–1760.

- , , , , . Communication failures in patient sign‐out and suggestions for improvement: a critical incident analysis. Qual Saf Health Care. 2005;14(6):401–407.

- , , , . Medical errors involving trainees: a study of closed malpractice claims from 5 insurers. Archives of internal medicine. 2007;167(19):2030–2036.

- , , , et al. Patterns of communication breakdowns resulting in injury to surgical patients. J Am Coll Surg. 2007;204(4):533–540.

- Joint Commission International. Standard PC.02.02.01. 2013 Hospital Accreditation Standards. Oak Brook, IL: Joint Commission Resources; 2013.

- , , , , , . Hospitalist handoffs: a systematic review and task force recommendations. J Hosp Med. 2009;4(7):433–440.

- , , . Systematic review of handoff mnemonics literature. Am J Med Qual. 2009;24(3):196–204.

- , , , , . Using a computerized sign‐out program to improve continuity of inpatient care and prevent adverse events. Jt Comm J Qual Improv. 1998;24(2):77–87.

- , , , , . Impact of a new electronic handover system in surgery. Int J Surg. 2011;9(3):217–220.

- , , , . Organizing the transfer of patient care information: the development of a computerized resident sign‐out system. Surgery. 2004;136(1):5–13.

- , , , . Handover after pediatric heart surgery: a simple tool improves information exchange. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2011;12(3):309–313.

- , , , et al. Simple standardized patient handoff system that increases accuracy and completeness. J Surg Educ. 2008;65(6):476–485.

- , , , et al. Enhancing patient safety in the trauma/surgical intensive care unit. J Trauma. 2009;67(3):430–433; discussion 433–435.

- , , . Standardized sign‐out reduces intern perception of medical errors on the general internal medicine ward. Teach Learn Med. 2009;21(2):121–126.

- , , , , . Gaining efficiency and satisfaction in the handoff process. J Hosp Med. 2010;5(9):547–552.

- , , . Identification of patient information corruption in the intensive care unit: using a scoring tool to direct quality improvements in handover. Crit Care Med. 2009;37(11):2905–2912.

- . Examining the effects that manipulating information given in the change of shift report has on nurses' care planning ability. J Adv Nurs. 2001;33(6):836–846.

- , , , et al. Evaluation of an asynchronous physician voicemail sign‐out for emergency department admissions. Ann Emerg Med. 2009;54(3):368–378.

- , , , et al. Surgical team behaviors and patient outcomes. Am J Surg. 2009;197(5):678–685.

- , , , , , . The value of adding a verbal report to written handoffs on early readmission following prolonged respiratory failure. Chest. 2010;138(6):1475–1479.

- , , , et al. Rates of medical errors and preventable adverse events among hospitalized children following implementation of a resident handoff bundle. JAMA. 2013;310(21):2262–2270.

- , , , . A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(5):373–383.

- , . IHI Global Trigger Tool for measuring adverse events (second edition). IHI Innovation Series white paper. Cambridge, MA: Institute for Healthcare Improvement; 2009. Available at: http://www.ihi.org/resources/Pages/IHIWhitePapers/IHIGlobalTriggerToolWhitePaper.aspx. www.IHI.org). Accessed June 1, 2014.

- National Coordinating Council for Medication Error Reporting and Prevention (NCC MERP) index for categorizing errors. Available at: http://www.nccmerp.org/medErrorCatIndex.html. Accessed June 1, 2014.

- , , , , , . Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—a metadata‐driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377–381.

- , . Statistics in Epidemiology: Methods, Techniques, and Applications. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 1996.

- , , , , , . Safety of using a computerized rounding and sign‐out system to reduce resident duty hours. Acad Med. 2010;85(7):1189–1195.

Handoffs are key events in the care of hospitalized patients whereby vital information is relayed between healthcare providers. Resident duty hour restrictions and the popularity of shift‐based work schedules have increased the frequency of inpatient handoffs.[1, 2] Failures in communication at the time of patient handoff have been implicated as contributing factors to preventable adverse events.[3, 4, 5, 6] With patient safety in mind, accreditation organizations and professional societies have made the standardization of hospital handoff procedures a priority.[7, 8] A variety of strategies have been utilized to standardize handoffs. Examples include the use of mnemonics,[9] electronic resources,[10, 11, 12] preformatted handoff sheets,[13, 14, 15, 16] and optimization of the handoff environment.[17] The primary outcomes for many of these studies center on the provider by measuring their retention of patient facts[18, 19] and completion of tasks[14, 16] after handoff, for example. Few studies examined patient‐centered outcomes such as transfer to a higher level of care,[20] length of stay,[11] mortality,[21] or readmission rate.[22] A study in the pediatric population found that implementation of a handoff bundle was associated with a decrease in medical errors and preventable adverse events.[23]

The Society of Hospital Medicine recommends that patient handoffs consist of both a written and verbal component.[8] Providers in our division work on 3 shifts: day, evening, and night. In 2009, we developed a face‐to‐face morning handoff, during which night‐shift providers hand off patient care to day‐shift providers incorporating an electronically generated service information list.[17] Given that the evening shift ends well before the day shift begins, the evening‐shift providers do not participate in this face‐to‐face handoff of care for patients they admit to day providers.

We wished to compare the clinical outcomes and adverse events of patients admitted by the night‐shift providers to those admitted by the evening‐shift providers. We hypothesized that transfer of care using a face‐to‐face handoff would be associated with fewer adverse events and improved clinical outcomes.

METHODS

The study was deemed exempt by the Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board.

Study Population

Hospitalists at the study institution, a 1157‐bed academic tertiary referral hospital, admit general medical patients from the emergency department, as transfers from other institutions, and as direct admissions from outpatient offices. Patients included in the study were all adults admitted by evening‐ and night‐shift hospitalists from August 1, 2011 through August 1, 2012 between 6:45 pm and midnight. Our institution primarily uses 2 levels of care for adult inpatients on internal medicine services, including a general care floor for low‐acuity patients and an intensive care unit for high‐acuity patients. All of the patients in this study were triaged as low acuity at the time of admission and were initially admitted to general care units.

Setting

The division's shift schedule during the study period is depicted in Figure 1. Day‐shift providers included a physician and nurse practitioner (NP) or physician assistant (PA) on each of 7 teams. Each service had an average daily patient census between 10 and 15 patients with 3 to 4 new admissions every 24 hours, with 1 to 2 of these admissions occurring during the evening and night shifts, on average. The day shift started at 7:45 am and ended at 7:45 pm, at which time the day teams transitioned care of their patients to 1 of 2 overnight NP/PAs who provided cross‐cover for all teams through the night. The overnight NP/PAs then transitioned care back to the day teams at 7:45 am the following morning.

Two evening‐shift providers, both physicians, including a staff hospitalist and a hospital medicine fellowship trainee, admitted patients without any cross‐cover responsibility. Their shifts had the same start time, but staggered end times (2 pm10 pm and 2 pmmidnight). At the end of their shifts, the evening‐shift providers relayed concerns or items for follow‐up to the night cross‐cover NP/PAs; however, this handoff was nonstandardized and provider dependent. The cross‐cover providers could also choose to pass on any relevant information to day‐shift providers if thought to be necessary, but this, again, was not required or standardized. A printed electronic handoff tool (including the patient's problem list, medications, vital signs, laboratory results, and to do list as determined by the admitting provider) as well as all clinical notes generated since admission were made available to day‐shift providers who assumed care at 7:45 am; however, there was no face‐to‐face handoff between the evening‐ and day‐shift providers.

Two night‐shift physicians, including a moonlighting board‐eligible internal medicine physician and staff hospitalist, also started at staggered times, 6:45 pm and 10 pm, but their shifts both ended at 7:45 am. These physicians also admitted patients without cross‐cover responsibilities. At 7:45 am, in a face‐to‐face meeting, they transitioned care of patients admitted overnight to day‐shift providers. This handoff occurred at a predesignated place with assigned start times for each team. During the meeting, printed electronic documents, including the aforementioned electronic handoff tool as well as all clinical notes generated since admission, were made available to the oncoming day‐shift providers. The face‐to‐face interaction between night‐ and day‐shift providers lasted approximately 5 minutes and allowed for a brief presentation of the patient, review of the diagnostic testing and treatments performed so far, as well as anticipatory guidance regarding potential issues throughout the remainder of the hospitalization. Although inclusion of the above components was encouraged during the face‐to‐face handoff, the interaction was not scripted and topics discussed were at the providers' discretion.

Patients admitted during the evening and night shifts were assigned to day‐shift services primarily based on the current census of each team, so as to distribute the workload evenly.

Chart Review

Patients included in the study were admitted by evening‐ or night‐shift providers between 6:45 pm and midnight. This time period accounts for when the evening shift and night shift overlap, allowing for direct comparison of patients admitted during the same time of day, so as to avoid confounding factors. Patients were grouped by whether they were admitted by an evening‐shift provider or a night‐shift provider. Each study patient's chart was retrospectively reviewed and relevant demographic and clinical data were collected. Demographic information included age, gender, and race. Clinical information included medical comorbidities, Charlson Comorbidity Index score, rapid response team calls, code team calls, transfers to a higher level of care, death in hospital, 30‐day readmission rate, length of stay (LOS), and adverse events. The Charlson Comorbidity Index score[24] was determined from diagnoses in the institution's medical index database. The 30‐day readmission rate included observation stays and full hospital admissions that occurred at our institution in the 30 days following the patient's hospital discharge from the index admission. LOS was determined based on the time of admission and discharge, as reported in the hospital billing system, and is reported as the median and mean LOS in hours for all patients in each group.

The Global Trigger Tool (GTT) was used to identify adverse events, as defined within the GTT whitepaper to be unintended physical injury resulting from or contributed to by medical care that requires additional monitoring, treatment or hospitalization, or that results in death.[25] Developed by the Institute for Healthcare Improvement, the GTT uses triggers, clues in the medical record that suggest an adverse event may have occurred, to cue a more detailed chart review. Registered nurses trained in use of the GTT reviewed all of the included patients' electronic medical records. If a trigger was identified (such as a patient fall suffered in the hospital), further chart review was prompted to determine if patient harm occurred. If there was evidence of harm, an adverse event was determined to have occurred and was then categorized using the National Coordinating Council for Medication Error Reporting and Prevention Index for Categorizing Errors.[26] For example, in the case of a patient fall whereby the patient was determined to have fallen in the hospital and suffered a laceration requiring wound care, but the hospital stay was not prolonged, this adverse event was categorized as category E (an adverse event that caused the patient temporary harm necessitating intervention, without prolongation of the hospital stay).

Outcomes including rapid response team calls, code team calls, transfers to a higher level of care, death in the hospital, and adverse events, as identified using the GTT, were counted if they occurred between 7:45 am on the first morning of admission until 12 hours later at 7:45 pm, at the time of the first evening handoff of the admitted patients' care.

Statistical Methods

Study data were collected and managed using REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture) electronic data capture tools hosted at Mayo Clinic.[27] When comparing outcomes between the 2 groups, Fisher exact test was used for categorical variables and Student t test was used for continuous variables. Global Trigger Tool data were analyzed using the SAS GENMOD procedure, assuming a negative binomial distribution. All the above analyses were performed using SAS version 9.3 software (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). Rates of adverse events were compared using MedCalc version 13 software (MedCalc Software, Ostend, Belgium).[28] A P value <0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

Of 805 patients admitted between 6:45 pm and midnight during the study period, 305 (37.9%) patients were handed off to day‐shift providers without face‐to‐face handoff, and 500 (62.1%) patients were transferred to the care of day‐shift providers with the use of a face‐to‐face handoff.

Baseline characteristics of both groups are depicted in Table 1. Demographic characteristics, including age, gender, and race, were not significantly different between groups. The mean Charlson Comorbidity Index score was not significantly different between the groups without and with a face‐to‐face handoff. In addition, the presence of medical comorbidities including type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertension, coronary artery disease, hyperlipidemia, heart failure, body mass index (BMI) <18, active cancer, and current cigarette smoking were not significantly different between the 2 groups. There was a trend to a significantly increased proportion of patients with a BMI >30 in the group without face‐to‐face handoff (P=0.05).

| Without Face‐to‐Face Handoff, N=305 | With Face‐to‐Face Handoff, N=500 | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Age, y, mean (SD) | 65.8 (19.0) | 64.2 (20.0) | 0.25 |

| Sex, n (%) | 0.69 | ||

| Female | 166 (54%) | 265 (53%) | |

| Male | 139 (46%) | 235 (47%) | |

| Race, n (%) | 0.94 | ||

| White | 287 (95%) | 466 (93%) | |

| African American | 5 (2%) | 9 (2%) | |

| Arab/Middle Eastern | 3 (1%) | 8 (2%) | |

| Asian | 1 (0%) | 3 (1%) | |

| Indian subcontinental | 1 (0%) | 1 (0%) | |

| American Indian/Alaskan | 1 (0%) | 1 (0%) | |

| Other | 3 (1%) | 8 (2%) | |

| Unknown | 1 (0%) | 4 (1%) | |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index, mean ( SD) | 2.98 ( 3.73) | 2.93 ( 3.72) | 0.85 |

| Comorbidities, n (%) | |||

| Type 2 diabetes | 82 (27%) | 143 (29%) | 0.60 |

| Hypertension | 195 (64%) | 303 (61%) | 0.34 |

| Coronary artery disease | 76 (25%) | 137 (27%) | 0.44 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 122 (40%) | 206 (41%) | 0.74 |

| Heart failure | 30 (10%) | 66 (13%) | 0.15 |

| BMI >30 | 109 (36%) | 146 (29%) | 0.05 |

| BMI <18 | 7 (2%) | 12 (2%) | 0.92 |

| Active cancer | 29 (10%) | 46 (9%) | 0.88 |

| Current smoker | 49 (16%) | 90 (18%) | 0.48 |

Results for the outcomes of this study are depicted in Table 2. The frequency of rapid response team calls, code team calls, transfers to a higher level of care, and death in the hospital in the 12 hours following the first morning handoff of the admission were not significantly different between the 2 groups. Both 30‐day readmission rate and LOS (median and mean) were not significantly different between groups.

| Without Face‐to‐Face Handoff, N=305 | With Face‐to‐Face Handoff, N=500 | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Rapid response team call, n (%) | 4 (1%) | 5 (1%) | 0.68 |

| Code team call, n (%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (0%) | 0.43 |

| Transfer to higher level of care, n (%) | 7 (2%) | 11 (2%) | 0.93 |

| Patient death, n (%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1.00 |

| 30‐day readmission, n (%) | 50 (16%) | 67 (13%) | 0.23 |

| Hospital length of stay | |||

| Median, h (IQR) | 66.5 (41.3115.6) | 70.3 (41.9131.2) | 0.30 |

| Mean, h ( SD) | 102.0 ( 110.0) | 102.9 ( 94.0) | 0.90 |

| Adverse events (Global Trigger Tool) | |||

| Temporary harm and required intervention (E) | 4 | 7 | 0.92 |

| Temporary harm and required initial or prolonged hospitalization (F) | 7 | 8 | 0.53 |

| Permanent harm (G) | 0 | 1 | 0.44 |

| Intervention required to sustain life (H) | 0 | 6 | 0.14 |

| Death (I) | 0 | 0 | 1.00 |

| Total adverse events per 100 admissions | 3.61 | 4.40 | 0.59 |

| % of admissions with an adverse event | 2.6% | 3.2% | 0.64 |

There was no significant difference between the 2 groups in the frequency of adverse events resulting in harm for any of the categories (categories EI). Total adverse events between groups were also compared. Adverse events per 100 admissions were not significantly different between the group without face‐to‐face handoff compared to the group with face‐to‐face handoff. The percentage of admissions with an adverse event was also similar between groups.

DISCUSSION

We found no significant difference in the rate of rapid response team calls, code team calls, transfers to a higher level of care, death in hospital, or adverse events when comparing patients transitioned to the care of day‐shift providers with or without a face‐to‐face handoff. We hypothesize that a reason adverse events were no different between the 2 groups may be that providers were more vigilant when they did not receive a face‐to‐face handoff from the previous provider. As a result, providers may have dedicated additional time reviewing the medical record, speaking with the patients, and communicating with other healthcare providers to ensure a safe care transition. Similarly, other studies found no significant reduction in adverse events when using a standardized handoff.[10, 13, 29] This may be because patient handoff is 1 of a multitude of factors that impact the rate of adverse events, and a handoff may play a less vital role in a system where documentation of care for a given patient is readily accessible, uniform, and detailed. A face‐to‐face interaction itself in a patient handoff may be less pertinent if key information can be communicated through other channels, such as an electronic handoff tool, email, or phone.

Another potential explanation for the lack of a significant difference in patient outcomes with and without a face‐to‐face handoff is related to the study design and inherent rate of the events measured. With the exception of 30‐day readmission rate and LOS, the outcomes of the study were recorded only if they occurred in the 12 hours following the first morning handoff of the admission. This was done in an attempt to isolate the effect of the nonface‐to‐face versus face‐to‐face handoff on the first morning of the admission, and to avoid confounding effects by subsequent transitions of care later in the hospitalization. The frequency of hospital admissions in which an adverse event occurred during this relatively short 12‐hour window was approximately 3% for all patients in the study. With 805 total patients in the study, there may have been insufficient statistical power to detect a difference in the rate of outcomes, if a difference did exist, considering the event rate for both groups and the sample size.

There are several additional limitations to our study. First, the GTT was designed to be applied across the entirety of a hospitalization. By screening for adverse events over the span of only 12 hours for each hospitalization, the sensitivity of the tool may have been diminished, with a proportion of adverse events not captured, even when the sequence of events leading to patient harm began during the 12 hours in question. Second, this is a retrospective study, and all adverse events may not be documented in the medical record. Third, although not formally structured and infrequent, some evening‐shift providers did send an email or call the oncoming day‐shift provider to discuss patients admitted. This process, however, was provider dependent, unstructured, uncommon, and erratic, and thus we were not able to capture it from medical record review. Finally, the patients in this study were deemed low acuity upon triage prior to admission. A face‐to‐face handoff may be less important in ensuring patient safety when caring for low‐acuity compared to high‐acuity patients, considering the rapidity at which the critically ill can deteriorate.

Handoffs of patient care in the hospital have certainly increased in recent years. Consequently, communication among providers is undoubtedly important, with patient safety being the primary goal. Our work suggests that a face‐to‐face component of a handoff is not vital to ensure a safe care transition. Because of the increasing frequency of handoffs, providers' ability to do so face‐to‐face will likely be challenged by time and logistical constraints. Future work is needed to delineate the most effective components of the handoff so that we can design information transfer that promotes safe and efficient care, even without a face‐to‐face interaction.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful for support from the Mayo Clinic Department of Medicine Clinical Research Office, Ms. Donna Lawson, and Mr. Stephen Cha.

Disclosures: This publication was made possible by the Mayo Clinic Center for Clinical and Translational Science through grant number UL1 TR000135 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Science, a component of the National Institutes of Health. The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Handoffs are key events in the care of hospitalized patients whereby vital information is relayed between healthcare providers. Resident duty hour restrictions and the popularity of shift‐based work schedules have increased the frequency of inpatient handoffs.[1, 2] Failures in communication at the time of patient handoff have been implicated as contributing factors to preventable adverse events.[3, 4, 5, 6] With patient safety in mind, accreditation organizations and professional societies have made the standardization of hospital handoff procedures a priority.[7, 8] A variety of strategies have been utilized to standardize handoffs. Examples include the use of mnemonics,[9] electronic resources,[10, 11, 12] preformatted handoff sheets,[13, 14, 15, 16] and optimization of the handoff environment.[17] The primary outcomes for many of these studies center on the provider by measuring their retention of patient facts[18, 19] and completion of tasks[14, 16] after handoff, for example. Few studies examined patient‐centered outcomes such as transfer to a higher level of care,[20] length of stay,[11] mortality,[21] or readmission rate.[22] A study in the pediatric population found that implementation of a handoff bundle was associated with a decrease in medical errors and preventable adverse events.[23]

The Society of Hospital Medicine recommends that patient handoffs consist of both a written and verbal component.[8] Providers in our division work on 3 shifts: day, evening, and night. In 2009, we developed a face‐to‐face morning handoff, during which night‐shift providers hand off patient care to day‐shift providers incorporating an electronically generated service information list.[17] Given that the evening shift ends well before the day shift begins, the evening‐shift providers do not participate in this face‐to‐face handoff of care for patients they admit to day providers.

We wished to compare the clinical outcomes and adverse events of patients admitted by the night‐shift providers to those admitted by the evening‐shift providers. We hypothesized that transfer of care using a face‐to‐face handoff would be associated with fewer adverse events and improved clinical outcomes.

METHODS

The study was deemed exempt by the Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board.

Study Population

Hospitalists at the study institution, a 1157‐bed academic tertiary referral hospital, admit general medical patients from the emergency department, as transfers from other institutions, and as direct admissions from outpatient offices. Patients included in the study were all adults admitted by evening‐ and night‐shift hospitalists from August 1, 2011 through August 1, 2012 between 6:45 pm and midnight. Our institution primarily uses 2 levels of care for adult inpatients on internal medicine services, including a general care floor for low‐acuity patients and an intensive care unit for high‐acuity patients. All of the patients in this study were triaged as low acuity at the time of admission and were initially admitted to general care units.

Setting

The division's shift schedule during the study period is depicted in Figure 1. Day‐shift providers included a physician and nurse practitioner (NP) or physician assistant (PA) on each of 7 teams. Each service had an average daily patient census between 10 and 15 patients with 3 to 4 new admissions every 24 hours, with 1 to 2 of these admissions occurring during the evening and night shifts, on average. The day shift started at 7:45 am and ended at 7:45 pm, at which time the day teams transitioned care of their patients to 1 of 2 overnight NP/PAs who provided cross‐cover for all teams through the night. The overnight NP/PAs then transitioned care back to the day teams at 7:45 am the following morning.

Two evening‐shift providers, both physicians, including a staff hospitalist and a hospital medicine fellowship trainee, admitted patients without any cross‐cover responsibility. Their shifts had the same start time, but staggered end times (2 pm10 pm and 2 pmmidnight). At the end of their shifts, the evening‐shift providers relayed concerns or items for follow‐up to the night cross‐cover NP/PAs; however, this handoff was nonstandardized and provider dependent. The cross‐cover providers could also choose to pass on any relevant information to day‐shift providers if thought to be necessary, but this, again, was not required or standardized. A printed electronic handoff tool (including the patient's problem list, medications, vital signs, laboratory results, and to do list as determined by the admitting provider) as well as all clinical notes generated since admission were made available to day‐shift providers who assumed care at 7:45 am; however, there was no face‐to‐face handoff between the evening‐ and day‐shift providers.

Two night‐shift physicians, including a moonlighting board‐eligible internal medicine physician and staff hospitalist, also started at staggered times, 6:45 pm and 10 pm, but their shifts both ended at 7:45 am. These physicians also admitted patients without cross‐cover responsibilities. At 7:45 am, in a face‐to‐face meeting, they transitioned care of patients admitted overnight to day‐shift providers. This handoff occurred at a predesignated place with assigned start times for each team. During the meeting, printed electronic documents, including the aforementioned electronic handoff tool as well as all clinical notes generated since admission, were made available to the oncoming day‐shift providers. The face‐to‐face interaction between night‐ and day‐shift providers lasted approximately 5 minutes and allowed for a brief presentation of the patient, review of the diagnostic testing and treatments performed so far, as well as anticipatory guidance regarding potential issues throughout the remainder of the hospitalization. Although inclusion of the above components was encouraged during the face‐to‐face handoff, the interaction was not scripted and topics discussed were at the providers' discretion.

Patients admitted during the evening and night shifts were assigned to day‐shift services primarily based on the current census of each team, so as to distribute the workload evenly.

Chart Review

Patients included in the study were admitted by evening‐ or night‐shift providers between 6:45 pm and midnight. This time period accounts for when the evening shift and night shift overlap, allowing for direct comparison of patients admitted during the same time of day, so as to avoid confounding factors. Patients were grouped by whether they were admitted by an evening‐shift provider or a night‐shift provider. Each study patient's chart was retrospectively reviewed and relevant demographic and clinical data were collected. Demographic information included age, gender, and race. Clinical information included medical comorbidities, Charlson Comorbidity Index score, rapid response team calls, code team calls, transfers to a higher level of care, death in hospital, 30‐day readmission rate, length of stay (LOS), and adverse events. The Charlson Comorbidity Index score[24] was determined from diagnoses in the institution's medical index database. The 30‐day readmission rate included observation stays and full hospital admissions that occurred at our institution in the 30 days following the patient's hospital discharge from the index admission. LOS was determined based on the time of admission and discharge, as reported in the hospital billing system, and is reported as the median and mean LOS in hours for all patients in each group.

The Global Trigger Tool (GTT) was used to identify adverse events, as defined within the GTT whitepaper to be unintended physical injury resulting from or contributed to by medical care that requires additional monitoring, treatment or hospitalization, or that results in death.[25] Developed by the Institute for Healthcare Improvement, the GTT uses triggers, clues in the medical record that suggest an adverse event may have occurred, to cue a more detailed chart review. Registered nurses trained in use of the GTT reviewed all of the included patients' electronic medical records. If a trigger was identified (such as a patient fall suffered in the hospital), further chart review was prompted to determine if patient harm occurred. If there was evidence of harm, an adverse event was determined to have occurred and was then categorized using the National Coordinating Council for Medication Error Reporting and Prevention Index for Categorizing Errors.[26] For example, in the case of a patient fall whereby the patient was determined to have fallen in the hospital and suffered a laceration requiring wound care, but the hospital stay was not prolonged, this adverse event was categorized as category E (an adverse event that caused the patient temporary harm necessitating intervention, without prolongation of the hospital stay).

Outcomes including rapid response team calls, code team calls, transfers to a higher level of care, death in the hospital, and adverse events, as identified using the GTT, were counted if they occurred between 7:45 am on the first morning of admission until 12 hours later at 7:45 pm, at the time of the first evening handoff of the admitted patients' care.

Statistical Methods

Study data were collected and managed using REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture) electronic data capture tools hosted at Mayo Clinic.[27] When comparing outcomes between the 2 groups, Fisher exact test was used for categorical variables and Student t test was used for continuous variables. Global Trigger Tool data were analyzed using the SAS GENMOD procedure, assuming a negative binomial distribution. All the above analyses were performed using SAS version 9.3 software (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). Rates of adverse events were compared using MedCalc version 13 software (MedCalc Software, Ostend, Belgium).[28] A P value <0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

Of 805 patients admitted between 6:45 pm and midnight during the study period, 305 (37.9%) patients were handed off to day‐shift providers without face‐to‐face handoff, and 500 (62.1%) patients were transferred to the care of day‐shift providers with the use of a face‐to‐face handoff.

Baseline characteristics of both groups are depicted in Table 1. Demographic characteristics, including age, gender, and race, were not significantly different between groups. The mean Charlson Comorbidity Index score was not significantly different between the groups without and with a face‐to‐face handoff. In addition, the presence of medical comorbidities including type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertension, coronary artery disease, hyperlipidemia, heart failure, body mass index (BMI) <18, active cancer, and current cigarette smoking were not significantly different between the 2 groups. There was a trend to a significantly increased proportion of patients with a BMI >30 in the group without face‐to‐face handoff (P=0.05).

| Without Face‐to‐Face Handoff, N=305 | With Face‐to‐Face Handoff, N=500 | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Age, y, mean (SD) | 65.8 (19.0) | 64.2 (20.0) | 0.25 |

| Sex, n (%) | 0.69 | ||

| Female | 166 (54%) | 265 (53%) | |

| Male | 139 (46%) | 235 (47%) | |

| Race, n (%) | 0.94 | ||

| White | 287 (95%) | 466 (93%) | |

| African American | 5 (2%) | 9 (2%) | |

| Arab/Middle Eastern | 3 (1%) | 8 (2%) | |

| Asian | 1 (0%) | 3 (1%) | |

| Indian subcontinental | 1 (0%) | 1 (0%) | |

| American Indian/Alaskan | 1 (0%) | 1 (0%) | |

| Other | 3 (1%) | 8 (2%) | |

| Unknown | 1 (0%) | 4 (1%) | |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index, mean ( SD) | 2.98 ( 3.73) | 2.93 ( 3.72) | 0.85 |

| Comorbidities, n (%) | |||

| Type 2 diabetes | 82 (27%) | 143 (29%) | 0.60 |

| Hypertension | 195 (64%) | 303 (61%) | 0.34 |

| Coronary artery disease | 76 (25%) | 137 (27%) | 0.44 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 122 (40%) | 206 (41%) | 0.74 |

| Heart failure | 30 (10%) | 66 (13%) | 0.15 |

| BMI >30 | 109 (36%) | 146 (29%) | 0.05 |

| BMI <18 | 7 (2%) | 12 (2%) | 0.92 |

| Active cancer | 29 (10%) | 46 (9%) | 0.88 |

| Current smoker | 49 (16%) | 90 (18%) | 0.48 |

Results for the outcomes of this study are depicted in Table 2. The frequency of rapid response team calls, code team calls, transfers to a higher level of care, and death in the hospital in the 12 hours following the first morning handoff of the admission were not significantly different between the 2 groups. Both 30‐day readmission rate and LOS (median and mean) were not significantly different between groups.

| Without Face‐to‐Face Handoff, N=305 | With Face‐to‐Face Handoff, N=500 | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Rapid response team call, n (%) | 4 (1%) | 5 (1%) | 0.68 |

| Code team call, n (%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (0%) | 0.43 |

| Transfer to higher level of care, n (%) | 7 (2%) | 11 (2%) | 0.93 |

| Patient death, n (%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1.00 |

| 30‐day readmission, n (%) | 50 (16%) | 67 (13%) | 0.23 |

| Hospital length of stay | |||

| Median, h (IQR) | 66.5 (41.3115.6) | 70.3 (41.9131.2) | 0.30 |

| Mean, h ( SD) | 102.0 ( 110.0) | 102.9 ( 94.0) | 0.90 |

| Adverse events (Global Trigger Tool) | |||

| Temporary harm and required intervention (E) | 4 | 7 | 0.92 |

| Temporary harm and required initial or prolonged hospitalization (F) | 7 | 8 | 0.53 |

| Permanent harm (G) | 0 | 1 | 0.44 |

| Intervention required to sustain life (H) | 0 | 6 | 0.14 |

| Death (I) | 0 | 0 | 1.00 |

| Total adverse events per 100 admissions | 3.61 | 4.40 | 0.59 |

| % of admissions with an adverse event | 2.6% | 3.2% | 0.64 |

There was no significant difference between the 2 groups in the frequency of adverse events resulting in harm for any of the categories (categories EI). Total adverse events between groups were also compared. Adverse events per 100 admissions were not significantly different between the group without face‐to‐face handoff compared to the group with face‐to‐face handoff. The percentage of admissions with an adverse event was also similar between groups.

DISCUSSION

We found no significant difference in the rate of rapid response team calls, code team calls, transfers to a higher level of care, death in hospital, or adverse events when comparing patients transitioned to the care of day‐shift providers with or without a face‐to‐face handoff. We hypothesize that a reason adverse events were no different between the 2 groups may be that providers were more vigilant when they did not receive a face‐to‐face handoff from the previous provider. As a result, providers may have dedicated additional time reviewing the medical record, speaking with the patients, and communicating with other healthcare providers to ensure a safe care transition. Similarly, other studies found no significant reduction in adverse events when using a standardized handoff.[10, 13, 29] This may be because patient handoff is 1 of a multitude of factors that impact the rate of adverse events, and a handoff may play a less vital role in a system where documentation of care for a given patient is readily accessible, uniform, and detailed. A face‐to‐face interaction itself in a patient handoff may be less pertinent if key information can be communicated through other channels, such as an electronic handoff tool, email, or phone.

Another potential explanation for the lack of a significant difference in patient outcomes with and without a face‐to‐face handoff is related to the study design and inherent rate of the events measured. With the exception of 30‐day readmission rate and LOS, the outcomes of the study were recorded only if they occurred in the 12 hours following the first morning handoff of the admission. This was done in an attempt to isolate the effect of the nonface‐to‐face versus face‐to‐face handoff on the first morning of the admission, and to avoid confounding effects by subsequent transitions of care later in the hospitalization. The frequency of hospital admissions in which an adverse event occurred during this relatively short 12‐hour window was approximately 3% for all patients in the study. With 805 total patients in the study, there may have been insufficient statistical power to detect a difference in the rate of outcomes, if a difference did exist, considering the event rate for both groups and the sample size.

There are several additional limitations to our study. First, the GTT was designed to be applied across the entirety of a hospitalization. By screening for adverse events over the span of only 12 hours for each hospitalization, the sensitivity of the tool may have been diminished, with a proportion of adverse events not captured, even when the sequence of events leading to patient harm began during the 12 hours in question. Second, this is a retrospective study, and all adverse events may not be documented in the medical record. Third, although not formally structured and infrequent, some evening‐shift providers did send an email or call the oncoming day‐shift provider to discuss patients admitted. This process, however, was provider dependent, unstructured, uncommon, and erratic, and thus we were not able to capture it from medical record review. Finally, the patients in this study were deemed low acuity upon triage prior to admission. A face‐to‐face handoff may be less important in ensuring patient safety when caring for low‐acuity compared to high‐acuity patients, considering the rapidity at which the critically ill can deteriorate.

Handoffs of patient care in the hospital have certainly increased in recent years. Consequently, communication among providers is undoubtedly important, with patient safety being the primary goal. Our work suggests that a face‐to‐face component of a handoff is not vital to ensure a safe care transition. Because of the increasing frequency of handoffs, providers' ability to do so face‐to‐face will likely be challenged by time and logistical constraints. Future work is needed to delineate the most effective components of the handoff so that we can design information transfer that promotes safe and efficient care, even without a face‐to‐face interaction.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful for support from the Mayo Clinic Department of Medicine Clinical Research Office, Ms. Donna Lawson, and Mr. Stephen Cha.

Disclosures: This publication was made possible by the Mayo Clinic Center for Clinical and Translational Science through grant number UL1 TR000135 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Science, a component of the National Institutes of Health. The authors report no conflicts of interest.

- , , , et al. Effect of the 2011 vs 2003 duty hour regulation‐compliant models on sleep duration, trainee education, and continuity of patient care among internal medicine house staff: a randomized trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(8):649–655.

- . 'Shift work': 24‐hour workdays are out as residents, hospitals deal with changes, mixed feelings on restrictions. Mod Healthc. 2011;41(30):6–7, 16, 1.

- , , , , . Consequences of inadequate sign‐out for patient care. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(16):1755–1760.

- , , , , . Communication failures in patient sign‐out and suggestions for improvement: a critical incident analysis. Qual Saf Health Care. 2005;14(6):401–407.

- , , , . Medical errors involving trainees: a study of closed malpractice claims from 5 insurers. Archives of internal medicine. 2007;167(19):2030–2036.

- , , , et al. Patterns of communication breakdowns resulting in injury to surgical patients. J Am Coll Surg. 2007;204(4):533–540.

- Joint Commission International. Standard PC.02.02.01. 2013 Hospital Accreditation Standards. Oak Brook, IL: Joint Commission Resources; 2013.

- , , , , , . Hospitalist handoffs: a systematic review and task force recommendations. J Hosp Med. 2009;4(7):433–440.

- , , . Systematic review of handoff mnemonics literature. Am J Med Qual. 2009;24(3):196–204.

- , , , , . Using a computerized sign‐out program to improve continuity of inpatient care and prevent adverse events. Jt Comm J Qual Improv. 1998;24(2):77–87.

- , , , , . Impact of a new electronic handover system in surgery. Int J Surg. 2011;9(3):217–220.

- , , , . Organizing the transfer of patient care information: the development of a computerized resident sign‐out system. Surgery. 2004;136(1):5–13.

- , , , . Handover after pediatric heart surgery: a simple tool improves information exchange. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2011;12(3):309–313.

- , , , et al. Simple standardized patient handoff system that increases accuracy and completeness. J Surg Educ. 2008;65(6):476–485.

- , , , et al. Enhancing patient safety in the trauma/surgical intensive care unit. J Trauma. 2009;67(3):430–433; discussion 433–435.

- , , . Standardized sign‐out reduces intern perception of medical errors on the general internal medicine ward. Teach Learn Med. 2009;21(2):121–126.

- , , , , . Gaining efficiency and satisfaction in the handoff process. J Hosp Med. 2010;5(9):547–552.

- , , . Identification of patient information corruption in the intensive care unit: using a scoring tool to direct quality improvements in handover. Crit Care Med. 2009;37(11):2905–2912.

- . Examining the effects that manipulating information given in the change of shift report has on nurses' care planning ability. J Adv Nurs. 2001;33(6):836–846.

- , , , et al. Evaluation of an asynchronous physician voicemail sign‐out for emergency department admissions. Ann Emerg Med. 2009;54(3):368–378.

- , , , et al. Surgical team behaviors and patient outcomes. Am J Surg. 2009;197(5):678–685.

- , , , , , . The value of adding a verbal report to written handoffs on early readmission following prolonged respiratory failure. Chest. 2010;138(6):1475–1479.

- , , , et al. Rates of medical errors and preventable adverse events among hospitalized children following implementation of a resident handoff bundle. JAMA. 2013;310(21):2262–2270.

- , , , . A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(5):373–383.

- , . IHI Global Trigger Tool for measuring adverse events (second edition). IHI Innovation Series white paper. Cambridge, MA: Institute for Healthcare Improvement; 2009. Available at: http://www.ihi.org/resources/Pages/IHIWhitePapers/IHIGlobalTriggerToolWhitePaper.aspx. www.IHI.org). Accessed June 1, 2014.

- National Coordinating Council for Medication Error Reporting and Prevention (NCC MERP) index for categorizing errors. Available at: http://www.nccmerp.org/medErrorCatIndex.html. Accessed June 1, 2014.

- , , , , , . Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—a metadata‐driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377–381.

- , . Statistics in Epidemiology: Methods, Techniques, and Applications. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 1996.

- , , , , , . Safety of using a computerized rounding and sign‐out system to reduce resident duty hours. Acad Med. 2010;85(7):1189–1195.

- , , , et al. Effect of the 2011 vs 2003 duty hour regulation‐compliant models on sleep duration, trainee education, and continuity of patient care among internal medicine house staff: a randomized trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(8):649–655.

- . 'Shift work': 24‐hour workdays are out as residents, hospitals deal with changes, mixed feelings on restrictions. Mod Healthc. 2011;41(30):6–7, 16, 1.

- , , , , . Consequences of inadequate sign‐out for patient care. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(16):1755–1760.

- , , , , . Communication failures in patient sign‐out and suggestions for improvement: a critical incident analysis. Qual Saf Health Care. 2005;14(6):401–407.

- , , , . Medical errors involving trainees: a study of closed malpractice claims from 5 insurers. Archives of internal medicine. 2007;167(19):2030–2036.

- , , , et al. Patterns of communication breakdowns resulting in injury to surgical patients. J Am Coll Surg. 2007;204(4):533–540.

- Joint Commission International. Standard PC.02.02.01. 2013 Hospital Accreditation Standards. Oak Brook, IL: Joint Commission Resources; 2013.

- , , , , , . Hospitalist handoffs: a systematic review and task force recommendations. J Hosp Med. 2009;4(7):433–440.

- , , . Systematic review of handoff mnemonics literature. Am J Med Qual. 2009;24(3):196–204.

- , , , , . Using a computerized sign‐out program to improve continuity of inpatient care and prevent adverse events. Jt Comm J Qual Improv. 1998;24(2):77–87.

- , , , , . Impact of a new electronic handover system in surgery. Int J Surg. 2011;9(3):217–220.

- , , , . Organizing the transfer of patient care information: the development of a computerized resident sign‐out system. Surgery. 2004;136(1):5–13.

- , , , . Handover after pediatric heart surgery: a simple tool improves information exchange. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2011;12(3):309–313.

- , , , et al. Simple standardized patient handoff system that increases accuracy and completeness. J Surg Educ. 2008;65(6):476–485.

- , , , et al. Enhancing patient safety in the trauma/surgical intensive care unit. J Trauma. 2009;67(3):430–433; discussion 433–435.

- , , . Standardized sign‐out reduces intern perception of medical errors on the general internal medicine ward. Teach Learn Med. 2009;21(2):121–126.

- , , , , . Gaining efficiency and satisfaction in the handoff process. J Hosp Med. 2010;5(9):547–552.

- , , . Identification of patient information corruption in the intensive care unit: using a scoring tool to direct quality improvements in handover. Crit Care Med. 2009;37(11):2905–2912.

- . Examining the effects that manipulating information given in the change of shift report has on nurses' care planning ability. J Adv Nurs. 2001;33(6):836–846.

- , , , et al. Evaluation of an asynchronous physician voicemail sign‐out for emergency department admissions. Ann Emerg Med. 2009;54(3):368–378.

- , , , et al. Surgical team behaviors and patient outcomes. Am J Surg. 2009;197(5):678–685.

- , , , , , . The value of adding a verbal report to written handoffs on early readmission following prolonged respiratory failure. Chest. 2010;138(6):1475–1479.

- , , , et al. Rates of medical errors and preventable adverse events among hospitalized children following implementation of a resident handoff bundle. JAMA. 2013;310(21):2262–2270.

- , , , . A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(5):373–383.

- , . IHI Global Trigger Tool for measuring adverse events (second edition). IHI Innovation Series white paper. Cambridge, MA: Institute for Healthcare Improvement; 2009. Available at: http://www.ihi.org/resources/Pages/IHIWhitePapers/IHIGlobalTriggerToolWhitePaper.aspx. www.IHI.org). Accessed June 1, 2014.

- National Coordinating Council for Medication Error Reporting and Prevention (NCC MERP) index for categorizing errors. Available at: http://www.nccmerp.org/medErrorCatIndex.html. Accessed June 1, 2014.

- , , , , , . Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—a metadata‐driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377–381.

- , . Statistics in Epidemiology: Methods, Techniques, and Applications. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 1996.

- , , , , , . Safety of using a computerized rounding and sign‐out system to reduce resident duty hours. Acad Med. 2010;85(7):1189–1195.

© 2015 Society of Hospital Medicine