User login

Guidelines for Treatment of Uncomplicated Cystitis and Pyelonephritis in Healthy, Community-Dwelling Women

Background

Uncomplicated cystitis is one of the most common indications for prescribing antimicrobial therapy to otherwise healthy women, but wide variation in prescribing practices has been described.1-2 This has prompted the need for guidelines to help providers in their selection of empiric antimicrobial regimens. Antibiotic selection should take into consideration the efficacy of individual agents, as well as their propensity for inducing resistance, altering gut flora, and increasing the risk of colonization or infection with multi-drug resistant organisms.

Guideline Update

In March 2010, the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) and the European Society for Microbiology and Infectious Diseases (ESCMID) published new guidelines for the treatment of uncomplicated cystitis and pyelonephritis in healthy, community-dwelling women.3

First-line recommended agents for empiric treatment of uncomplicated cystitis are:

- nitrofurantoin for five days;

- trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole for three days;

- fosfomycin in a single dose; or

- pivmecillinam (where available) for three to seven days.

Although highly efficacious, fluoroquinolones are not recommended as first-line treatment for acute cystitis because of their propensity for causing “collateral damage,” especially alteration of gut flora and increased risk of multi-drug resistant infection or colonization, including methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Oral beta-lactams (other than pivmecillinam) have generally demonstrated inferior efficacy and more adverse effects when compared with the above agents, and should be used only if none of the preferred agents can be used. Specifically, amoxicillin and ampicillin are not recommended as empiric therapy due to their low efficacy in unselected patients, though may be appropriate when culture data is available to guide therapy. Narrow spectrum cephalosporins are also a potential agent for use in certain clinical situations, although the guidelines do not make any recommendation for or against their use, given a lack of studies.

For the treatment of acute pyelonephritis, the guidelines emphasize that all patients should have urine culture and susceptibility testing in order to tailor empiric therapy to the specific uropathogen. A 5-7 day course of an oral fluoroquinolone is appropriate when the prevalence of resistance in community uropathogens is ≤10%. Where resistance is more common, an initial intravenous dose of ceftriaxone or an aminoglycoside can be administered prior to starting oral therapy. Other alternatives include a 14-day course of trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole or an oral beta-lactam.

Women requiring hospitalization for pyelonephritis should initially be treated with an intravenous antimicrobial regimen, the choice of which should be based on local resistance patterns. Recommended intravenous agents include fluoroquinolones, aminoglycosides (with or without ampicillin), extended-spectrum cephalosporins / penicillins, or carbapenems.

Analysis

Previous guidelines for the treatment of uncomplicated cystitis and pyelonephritis were published by the IDSA in 1999.4 The guidelines were updated based on the following factors:

- continued variability in prescribing practices;1-2

- increase in antimicrobial resistance among uropathogens;

- awareness of the unintended consequences of antimicrobial therapy, such as selection of drug-resistant organisms and colonization or infection with multi-drug resistant organisms; and

- study of newer agents and different durations of therapy.

Two important differences exist between the 1999 and 2010 guidelines:

- Nitrofurantoin has taken on more prominence in the 2010 guidelines for uncomplicated cystitis. The 1999 guidelines recommended trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole as a first-line agent and mentioned nitrofurantoin and fosfomycin as potential alternative agents, but had few studies available to inform comparative efficacy or duration of therapy.

- For the outpatient treatment of mildly-ill patients with acute pyelonephritis, the 1999 guidelines recommended 14 days of therapy regardless of the agent used; in contrast, the 2010 guidelines recommend a five- to seven-day course for oral fluoroquinolones.

The American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, American Urological Association, Association of Medical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases-Canada, and the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine have endorsed the 2010 IDSA-ESCMID guidelines. The IDSA and ESCMID plan to evaluate the need for revisions to the 2010 guidelines based on an annual review of the current literature.

HM Takeaways

The 2010 IDSA-ESCMID guidelines are a resource available to hospitalists treating acute uncomplicated cystitis and pyelonephritis. As important differences exist between the target population and the hospitalist’s patient population, there are some key points to consider for clinicians treating cystitis or pyelonephritis in hospitalized patients.

Importantly, while nitrofurantoin is favored as a first-line antimicrobial agent for cystitis in the 2010 IDSA-ESCMID guidelines, it might be problematic in hospitalized patients for several reasons:

- it is not approved or recommended for the treatment of pyelonephritis;

- it is contraindicated in patients with creatinine clearance <60 ml/min; and

- it is generally not recommended for use in patients >65 years old because of the risk of renal impairment (Beers Criteria).5

Additionally, the treatment of acute cystitis in men requires special consideration. Notably, nitrofurantoin is not recommended in men because of poor prostatic tissue penetration, and although studies are limited, some sources recommend a longer treatment duration of at least 7 days.6 Finally, hospitalized patients commonly have other conditions, such as urological abnormalities, indwelling Foley catheters, recent urinary tract instrumentation, recent use of antibiotics, risk for multi-drug resistant organisms, potential interactions with other medications, and immunosuppression. The presence of any of these factors will influence the choice of empiric therapy and may warrant treatment for complicated cystitis or pyelonephritis, which are not addressed by these guidelines.

Drs. Tarvin and Sponsler are academic hospitalists at Vanderbilt University School of Medicine in Nashville, Tenn.

References

- Huang ES, Stafford RS. National patterns in the treatment of urinary tract infections in women by ambulatory care physicians. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:635-639.

- Kahan NR, Chinitz DP, Kahan E. Longer than recommended empiric antibiotic treatment of urinary tract infection in women: an avoidable waste of money. J Clin Pharm Therap. 2004;29:59-63.

- Gupta K, Hooton TM, Naber KG, et al. International clinical practice guidelines for the treatment of acute uncomplicated cystitis and pyelonephritis in women: a 2010 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the European Society for Microbiology and Infectious Diseases. Clin Inf Dis. 2011;52(5):e103-20.

- Warren JW, Abrutyn E, Hebel JR, Schaeffer AJ, Stamm WE. Guidelines for antimicrobial treatment of acute bacterial cystitis and acute pyelonephritis in women. Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Inf Dis. 1999;29(4):745-58.

- Fick DM, Cooper JW, Wade WE, Waller JL, Maclean JR, Beers MH. Updating the Beers criteria for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults: results of a U.S. consensus panel of experts. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163(22):2716-2724.

- Mehnert-Kay SA. Diagnosis and management of uncomplicated urinary tract infections. A Fam Phys. 2005;72(3):451-456.

Background

Uncomplicated cystitis is one of the most common indications for prescribing antimicrobial therapy to otherwise healthy women, but wide variation in prescribing practices has been described.1-2 This has prompted the need for guidelines to help providers in their selection of empiric antimicrobial regimens. Antibiotic selection should take into consideration the efficacy of individual agents, as well as their propensity for inducing resistance, altering gut flora, and increasing the risk of colonization or infection with multi-drug resistant organisms.

Guideline Update

In March 2010, the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) and the European Society for Microbiology and Infectious Diseases (ESCMID) published new guidelines for the treatment of uncomplicated cystitis and pyelonephritis in healthy, community-dwelling women.3

First-line recommended agents for empiric treatment of uncomplicated cystitis are:

- nitrofurantoin for five days;

- trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole for three days;

- fosfomycin in a single dose; or

- pivmecillinam (where available) for three to seven days.

Although highly efficacious, fluoroquinolones are not recommended as first-line treatment for acute cystitis because of their propensity for causing “collateral damage,” especially alteration of gut flora and increased risk of multi-drug resistant infection or colonization, including methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Oral beta-lactams (other than pivmecillinam) have generally demonstrated inferior efficacy and more adverse effects when compared with the above agents, and should be used only if none of the preferred agents can be used. Specifically, amoxicillin and ampicillin are not recommended as empiric therapy due to their low efficacy in unselected patients, though may be appropriate when culture data is available to guide therapy. Narrow spectrum cephalosporins are also a potential agent for use in certain clinical situations, although the guidelines do not make any recommendation for or against their use, given a lack of studies.

For the treatment of acute pyelonephritis, the guidelines emphasize that all patients should have urine culture and susceptibility testing in order to tailor empiric therapy to the specific uropathogen. A 5-7 day course of an oral fluoroquinolone is appropriate when the prevalence of resistance in community uropathogens is ≤10%. Where resistance is more common, an initial intravenous dose of ceftriaxone or an aminoglycoside can be administered prior to starting oral therapy. Other alternatives include a 14-day course of trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole or an oral beta-lactam.

Women requiring hospitalization for pyelonephritis should initially be treated with an intravenous antimicrobial regimen, the choice of which should be based on local resistance patterns. Recommended intravenous agents include fluoroquinolones, aminoglycosides (with or without ampicillin), extended-spectrum cephalosporins / penicillins, or carbapenems.

Analysis

Previous guidelines for the treatment of uncomplicated cystitis and pyelonephritis were published by the IDSA in 1999.4 The guidelines were updated based on the following factors:

- continued variability in prescribing practices;1-2

- increase in antimicrobial resistance among uropathogens;

- awareness of the unintended consequences of antimicrobial therapy, such as selection of drug-resistant organisms and colonization or infection with multi-drug resistant organisms; and

- study of newer agents and different durations of therapy.

Two important differences exist between the 1999 and 2010 guidelines:

- Nitrofurantoin has taken on more prominence in the 2010 guidelines for uncomplicated cystitis. The 1999 guidelines recommended trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole as a first-line agent and mentioned nitrofurantoin and fosfomycin as potential alternative agents, but had few studies available to inform comparative efficacy or duration of therapy.

- For the outpatient treatment of mildly-ill patients with acute pyelonephritis, the 1999 guidelines recommended 14 days of therapy regardless of the agent used; in contrast, the 2010 guidelines recommend a five- to seven-day course for oral fluoroquinolones.

The American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, American Urological Association, Association of Medical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases-Canada, and the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine have endorsed the 2010 IDSA-ESCMID guidelines. The IDSA and ESCMID plan to evaluate the need for revisions to the 2010 guidelines based on an annual review of the current literature.

HM Takeaways

The 2010 IDSA-ESCMID guidelines are a resource available to hospitalists treating acute uncomplicated cystitis and pyelonephritis. As important differences exist between the target population and the hospitalist’s patient population, there are some key points to consider for clinicians treating cystitis or pyelonephritis in hospitalized patients.

Importantly, while nitrofurantoin is favored as a first-line antimicrobial agent for cystitis in the 2010 IDSA-ESCMID guidelines, it might be problematic in hospitalized patients for several reasons:

- it is not approved or recommended for the treatment of pyelonephritis;

- it is contraindicated in patients with creatinine clearance <60 ml/min; and

- it is generally not recommended for use in patients >65 years old because of the risk of renal impairment (Beers Criteria).5

Additionally, the treatment of acute cystitis in men requires special consideration. Notably, nitrofurantoin is not recommended in men because of poor prostatic tissue penetration, and although studies are limited, some sources recommend a longer treatment duration of at least 7 days.6 Finally, hospitalized patients commonly have other conditions, such as urological abnormalities, indwelling Foley catheters, recent urinary tract instrumentation, recent use of antibiotics, risk for multi-drug resistant organisms, potential interactions with other medications, and immunosuppression. The presence of any of these factors will influence the choice of empiric therapy and may warrant treatment for complicated cystitis or pyelonephritis, which are not addressed by these guidelines.

Drs. Tarvin and Sponsler are academic hospitalists at Vanderbilt University School of Medicine in Nashville, Tenn.

References

- Huang ES, Stafford RS. National patterns in the treatment of urinary tract infections in women by ambulatory care physicians. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:635-639.

- Kahan NR, Chinitz DP, Kahan E. Longer than recommended empiric antibiotic treatment of urinary tract infection in women: an avoidable waste of money. J Clin Pharm Therap. 2004;29:59-63.

- Gupta K, Hooton TM, Naber KG, et al. International clinical practice guidelines for the treatment of acute uncomplicated cystitis and pyelonephritis in women: a 2010 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the European Society for Microbiology and Infectious Diseases. Clin Inf Dis. 2011;52(5):e103-20.

- Warren JW, Abrutyn E, Hebel JR, Schaeffer AJ, Stamm WE. Guidelines for antimicrobial treatment of acute bacterial cystitis and acute pyelonephritis in women. Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Inf Dis. 1999;29(4):745-58.

- Fick DM, Cooper JW, Wade WE, Waller JL, Maclean JR, Beers MH. Updating the Beers criteria for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults: results of a U.S. consensus panel of experts. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163(22):2716-2724.

- Mehnert-Kay SA. Diagnosis and management of uncomplicated urinary tract infections. A Fam Phys. 2005;72(3):451-456.

Background

Uncomplicated cystitis is one of the most common indications for prescribing antimicrobial therapy to otherwise healthy women, but wide variation in prescribing practices has been described.1-2 This has prompted the need for guidelines to help providers in their selection of empiric antimicrobial regimens. Antibiotic selection should take into consideration the efficacy of individual agents, as well as their propensity for inducing resistance, altering gut flora, and increasing the risk of colonization or infection with multi-drug resistant organisms.

Guideline Update

In March 2010, the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) and the European Society for Microbiology and Infectious Diseases (ESCMID) published new guidelines for the treatment of uncomplicated cystitis and pyelonephritis in healthy, community-dwelling women.3

First-line recommended agents for empiric treatment of uncomplicated cystitis are:

- nitrofurantoin for five days;

- trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole for three days;

- fosfomycin in a single dose; or

- pivmecillinam (where available) for three to seven days.

Although highly efficacious, fluoroquinolones are not recommended as first-line treatment for acute cystitis because of their propensity for causing “collateral damage,” especially alteration of gut flora and increased risk of multi-drug resistant infection or colonization, including methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Oral beta-lactams (other than pivmecillinam) have generally demonstrated inferior efficacy and more adverse effects when compared with the above agents, and should be used only if none of the preferred agents can be used. Specifically, amoxicillin and ampicillin are not recommended as empiric therapy due to their low efficacy in unselected patients, though may be appropriate when culture data is available to guide therapy. Narrow spectrum cephalosporins are also a potential agent for use in certain clinical situations, although the guidelines do not make any recommendation for or against their use, given a lack of studies.

For the treatment of acute pyelonephritis, the guidelines emphasize that all patients should have urine culture and susceptibility testing in order to tailor empiric therapy to the specific uropathogen. A 5-7 day course of an oral fluoroquinolone is appropriate when the prevalence of resistance in community uropathogens is ≤10%. Where resistance is more common, an initial intravenous dose of ceftriaxone or an aminoglycoside can be administered prior to starting oral therapy. Other alternatives include a 14-day course of trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole or an oral beta-lactam.

Women requiring hospitalization for pyelonephritis should initially be treated with an intravenous antimicrobial regimen, the choice of which should be based on local resistance patterns. Recommended intravenous agents include fluoroquinolones, aminoglycosides (with or without ampicillin), extended-spectrum cephalosporins / penicillins, or carbapenems.

Analysis

Previous guidelines for the treatment of uncomplicated cystitis and pyelonephritis were published by the IDSA in 1999.4 The guidelines were updated based on the following factors:

- continued variability in prescribing practices;1-2

- increase in antimicrobial resistance among uropathogens;

- awareness of the unintended consequences of antimicrobial therapy, such as selection of drug-resistant organisms and colonization or infection with multi-drug resistant organisms; and

- study of newer agents and different durations of therapy.

Two important differences exist between the 1999 and 2010 guidelines:

- Nitrofurantoin has taken on more prominence in the 2010 guidelines for uncomplicated cystitis. The 1999 guidelines recommended trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole as a first-line agent and mentioned nitrofurantoin and fosfomycin as potential alternative agents, but had few studies available to inform comparative efficacy or duration of therapy.

- For the outpatient treatment of mildly-ill patients with acute pyelonephritis, the 1999 guidelines recommended 14 days of therapy regardless of the agent used; in contrast, the 2010 guidelines recommend a five- to seven-day course for oral fluoroquinolones.

The American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, American Urological Association, Association of Medical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases-Canada, and the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine have endorsed the 2010 IDSA-ESCMID guidelines. The IDSA and ESCMID plan to evaluate the need for revisions to the 2010 guidelines based on an annual review of the current literature.

HM Takeaways

The 2010 IDSA-ESCMID guidelines are a resource available to hospitalists treating acute uncomplicated cystitis and pyelonephritis. As important differences exist between the target population and the hospitalist’s patient population, there are some key points to consider for clinicians treating cystitis or pyelonephritis in hospitalized patients.

Importantly, while nitrofurantoin is favored as a first-line antimicrobial agent for cystitis in the 2010 IDSA-ESCMID guidelines, it might be problematic in hospitalized patients for several reasons:

- it is not approved or recommended for the treatment of pyelonephritis;

- it is contraindicated in patients with creatinine clearance <60 ml/min; and

- it is generally not recommended for use in patients >65 years old because of the risk of renal impairment (Beers Criteria).5

Additionally, the treatment of acute cystitis in men requires special consideration. Notably, nitrofurantoin is not recommended in men because of poor prostatic tissue penetration, and although studies are limited, some sources recommend a longer treatment duration of at least 7 days.6 Finally, hospitalized patients commonly have other conditions, such as urological abnormalities, indwelling Foley catheters, recent urinary tract instrumentation, recent use of antibiotics, risk for multi-drug resistant organisms, potential interactions with other medications, and immunosuppression. The presence of any of these factors will influence the choice of empiric therapy and may warrant treatment for complicated cystitis or pyelonephritis, which are not addressed by these guidelines.

Drs. Tarvin and Sponsler are academic hospitalists at Vanderbilt University School of Medicine in Nashville, Tenn.

References

- Huang ES, Stafford RS. National patterns in the treatment of urinary tract infections in women by ambulatory care physicians. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:635-639.

- Kahan NR, Chinitz DP, Kahan E. Longer than recommended empiric antibiotic treatment of urinary tract infection in women: an avoidable waste of money. J Clin Pharm Therap. 2004;29:59-63.

- Gupta K, Hooton TM, Naber KG, et al. International clinical practice guidelines for the treatment of acute uncomplicated cystitis and pyelonephritis in women: a 2010 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the European Society for Microbiology and Infectious Diseases. Clin Inf Dis. 2011;52(5):e103-20.

- Warren JW, Abrutyn E, Hebel JR, Schaeffer AJ, Stamm WE. Guidelines for antimicrobial treatment of acute bacterial cystitis and acute pyelonephritis in women. Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Inf Dis. 1999;29(4):745-58.

- Fick DM, Cooper JW, Wade WE, Waller JL, Maclean JR, Beers MH. Updating the Beers criteria for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults: results of a U.S. consensus panel of experts. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163(22):2716-2724.

- Mehnert-Kay SA. Diagnosis and management of uncomplicated urinary tract infections. A Fam Phys. 2005;72(3):451-456.

In the Literature: Research You Need to Know

Clinical question: What is the relationship between well-being and demographic factors, educational debt, and medical knowledge in internal-medicine residents?

Background: Physician distress during training is common and can negatively impact patient care. There has never been a study of internal-medicine residents nationally that examined the patterns of distress across demographic factors or the association of these factors with medical knowledge.

Study design: Cross-sectional study.

Setting: U.S. internal-medicine residency programs.

Synopsis: Of the 21,208 U.S. internal-medicine residents who completed the 2008 in-training examination, 77.3% had both survey and demographic data available for analysis. Nearly 15% of these 16,394 residents rated quality of life “as bad as it can be” or “somewhat bad,” and 32.9% felt somewhat or very dissatisfied with work-life balance.

Overall burnout, high levels of weekly emotional exhaustion, and weekly depersonalization were reported by 51.5%, 45.8%, and 28.9% of residents, respectively. Symptoms of emotional exhaustion decreased as training increased, while depersonalization increased after the first postgraduate year. Residents reporting quality of life “as bad as it can be,” emotional exhaustion, or debt greater than $200,000 had mean exam scores 2.7, 4.2, and 5 points, respectively, lower than others surveyed.

Although unlikely given the study design, nonresponse bias could affect these results. Not all demographic variables or domains of well-being were studied, and self-reported educational debt could have been misclassified. Nonetheless, findings suggest that distress remains among residents despite the changes made to duty-hour regulations in 2003.

Bottom line: Suboptimal quality of life and burnout were common among internal-medicine residents nationally; symptoms of burnout were associated with higher debt and lower exam scores.

Citation: West CP, Shanafelt TD, Kolars JC. Quality of life, burnout, educational debt, and medical knowledge among internal medicine residents. JAMA. 2011;306:952-960.

Visit our website for more physician reviews of HM-related research.

Clinical question: What is the relationship between well-being and demographic factors, educational debt, and medical knowledge in internal-medicine residents?

Background: Physician distress during training is common and can negatively impact patient care. There has never been a study of internal-medicine residents nationally that examined the patterns of distress across demographic factors or the association of these factors with medical knowledge.

Study design: Cross-sectional study.

Setting: U.S. internal-medicine residency programs.

Synopsis: Of the 21,208 U.S. internal-medicine residents who completed the 2008 in-training examination, 77.3% had both survey and demographic data available for analysis. Nearly 15% of these 16,394 residents rated quality of life “as bad as it can be” or “somewhat bad,” and 32.9% felt somewhat or very dissatisfied with work-life balance.

Overall burnout, high levels of weekly emotional exhaustion, and weekly depersonalization were reported by 51.5%, 45.8%, and 28.9% of residents, respectively. Symptoms of emotional exhaustion decreased as training increased, while depersonalization increased after the first postgraduate year. Residents reporting quality of life “as bad as it can be,” emotional exhaustion, or debt greater than $200,000 had mean exam scores 2.7, 4.2, and 5 points, respectively, lower than others surveyed.

Although unlikely given the study design, nonresponse bias could affect these results. Not all demographic variables or domains of well-being were studied, and self-reported educational debt could have been misclassified. Nonetheless, findings suggest that distress remains among residents despite the changes made to duty-hour regulations in 2003.

Bottom line: Suboptimal quality of life and burnout were common among internal-medicine residents nationally; symptoms of burnout were associated with higher debt and lower exam scores.

Citation: West CP, Shanafelt TD, Kolars JC. Quality of life, burnout, educational debt, and medical knowledge among internal medicine residents. JAMA. 2011;306:952-960.

Visit our website for more physician reviews of HM-related research.

Clinical question: What is the relationship between well-being and demographic factors, educational debt, and medical knowledge in internal-medicine residents?

Background: Physician distress during training is common and can negatively impact patient care. There has never been a study of internal-medicine residents nationally that examined the patterns of distress across demographic factors or the association of these factors with medical knowledge.

Study design: Cross-sectional study.

Setting: U.S. internal-medicine residency programs.

Synopsis: Of the 21,208 U.S. internal-medicine residents who completed the 2008 in-training examination, 77.3% had both survey and demographic data available for analysis. Nearly 15% of these 16,394 residents rated quality of life “as bad as it can be” or “somewhat bad,” and 32.9% felt somewhat or very dissatisfied with work-life balance.

Overall burnout, high levels of weekly emotional exhaustion, and weekly depersonalization were reported by 51.5%, 45.8%, and 28.9% of residents, respectively. Symptoms of emotional exhaustion decreased as training increased, while depersonalization increased after the first postgraduate year. Residents reporting quality of life “as bad as it can be,” emotional exhaustion, or debt greater than $200,000 had mean exam scores 2.7, 4.2, and 5 points, respectively, lower than others surveyed.

Although unlikely given the study design, nonresponse bias could affect these results. Not all demographic variables or domains of well-being were studied, and self-reported educational debt could have been misclassified. Nonetheless, findings suggest that distress remains among residents despite the changes made to duty-hour regulations in 2003.

Bottom line: Suboptimal quality of life and burnout were common among internal-medicine residents nationally; symptoms of burnout were associated with higher debt and lower exam scores.

Citation: West CP, Shanafelt TD, Kolars JC. Quality of life, burnout, educational debt, and medical knowledge among internal medicine residents. JAMA. 2011;306:952-960.

Visit our website for more physician reviews of HM-related research.

What Is the Appropriate Use of Antibiotics In Acute Exacerbations of COPD?

Case

A 58-year-old male smoker with moderate chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) (FEV1 56% predicted) is admitted with an acute exacerbation of COPD for the second time this year. He presented to the ED with increased productive cough and shortness of breath, similar to prior exacerbations. He denies fevers, myalgias, or upper-respiratory symptoms. Physical exam is notable for bilateral inspiratory and expiratory wheezing. His sputum is purulent. He is given continuous nebulizer therapy and one dose of oral prednisone, but his dyspnea and wheezing persist. Chest X-ray does not reveal an infiltrate.

Should this patient be treated with antibiotics and, if so, what regimen is most appropriate?

Overview

Acute exacerbations of COPD (AECOPD) present a major health burden, accounting for more than 2.4% of all hospital admissions and causing significant morbidity, mortality, and costs.1 During 2006 and 2007, COPD mortality in the United States topped 39 deaths per 100,000 people, and more recently, hospital costs related to COPD were expected to exceed $13 billion annually.2 Patients with AECOPD also experience decreased quality of life and faster decline in pulmonary function, further highlighting the need for timely and appropriate treatment.1

Several guidelines have proposed treatment strategies now considered standard of care in AECOPD management.3,4,5,6 These include the use of corticosteroids, bronchodilator agents, and, in select cases, antibiotics. While there is well-established evidence for the use of steroids and bronchodilators in AECOPD, the debate continues over the appropriate use of antibiotics in the treatment of acute exacerbations. There are multiple potential factors leading to AECOPD, including viruses, bacteria, and common pollutants; as such, antibiotic treatment may not be indicated for all patients presenting with exacerbations. Further, the risks of antibiotic treatment—including adverse drug events, selection for drug-resistant bacteria, and associated costs—are not insignificant.

However, bacterial infections do play a role in approximately 50% of patients with AECOPD and, for this population, use of antibiotics may confer important benefits.7

Interestingly, a retrospective cohort study of 84,621 patients admitted for AECOPD demonstrated that 85% of patients received antibiotics at some point during hospitalization.8

Support for Antibiotics

Several randomized trials have compared clinical outcomes in patients with AECOPD who have received antibiotics versus those who received placebos. Most of these had small sample sizes and studied only ββ-lactam and tetracycline antibiotics in an outpatient setting; there are limited data involving inpatients and newer drugs. Nevertheless, antibiotic treatment has been associated with decreased risk of adverse outcomes in AECOPD.

One meta-analysis demonstrated that antibiotics reduced treatment failures by 66% and in-hospital mortality by 78% in the subset of trials involving hospitalized patients.8 Similarly, analysis of a large retrospective cohort of patients hospitalized for AECOPD found a significantly lower risk of treatment failure in antibiotic-treated versus untreated patients.9 Specifically, treated patients had lower rates of in-hospital mortality and readmission for AECOPD and a lower likelihood of requiring subsequent mechanical ventilation during the index hospitalization.

Data also suggest that antibiotic treatment during exacerbations might favorably impact subsequent exacerbations.10 A retrospective study of 18,928 Dutch patients with AECOPD compared outcomes among patients who had received antibiotics (most frequently doxycycline or a penicillin) as part of their therapy to those who did not. The authors demonstrated that the median time to the next exacerbation was significantly longer in the patients receiving antibiotics.10 Further, both mortality and overall risk of developing a subsequent exacerbation were significantly decreased in the antibiotic group, with median follow-up of approximately two years.

Indications for Antibiotics

Clinical symptoms. A landmark study by Anthonisen and colleagues set forth three clinical criteria that have formed the basis for treating AECOPD with antibiotics in subsequent studies and in clinical practice.11 Often referred to as the “cardinal symptoms” of AECOPD, these include increased dyspnea, sputum volume, and sputum purulence. In this study, 173 outpatients with COPD were randomized to a 10-day course of antibiotics or placebo at onset of an exacerbation and followed clinically. The authors found that antibiotic-treated patients were significantly more likely than the placebo group to achieve treatment success, defined as resolution of all exacerbated symptoms within 21 days (68.1% vs. 55.0%, P<0.01).

Importantly, treated patients were also significantly less likely to experience clinical deterioration after 72 hours (9.9% vs. 18.9%, P<0.05). Patients with Type I exacerbations, characterized by all three cardinal symptoms, were most likely to benefit from antibiotic therapy, followed by patients with Type II exacerbations, in whom only two of the symptoms were present. Subsequent studies have suggested that sputum purulence correlates well with the presence of acute bacterial infection and therefore may be a reliable clinical indicator of patients who are likely to benefit from antibiotic therapy.12

Laboratory data. While sputum purulence is associated with bacterial infection, sputum culture is less reliable, as pathogenic bacteria are commonly isolated from patients with both AECOPD and stable COPD. In fact, the prevalence of bacterial colonization in moderate to severe COPD might be as high as 50%.13 Therefore, a positive bacterial sputum culture, in the absence of purulence or other signs of infection, is not recommended as the sole basis for which to prescribe antibiotics.

Serum biomarkers, most notably C-reactive protein (CRP) and procalcitonin, have been studied as a newer approach to identify patients who might benefit from antibiotic therapy for AECOPD. Studies have demonstrated increased CRP levels during AECOPD, particularly in patients with purulent sputum and positive bacterial sputum cultures.12 Procalcitonin is preferentially elevated in bacterial infections.

One randomized, placebo-controlled trial in hospitalized patients with AECOPD demonstrated a significant reduction in antibiotic usage based on low procalcitonin levels, without negatively impacting clinical success rate, hospital mortality, subsequent antibiotic needs, or time to next exacerbation.14 However, due to inconsistent evidence, use of these markers to guide antibiotic administration in AECOPD has not yet been definitively established.14,15 Additionally, these laboratory results are often not available at the point of care, potentially limiting their utility in the decision to initiate antibiotics.

Severity of illness. Severity of illness is an important factor in the decision to treat AECOPD with antibiotics. Patients with advanced, underlying airway obstruction, as measured by FEV1, are more likely to have a bacterial cause of AECOPD.16 Additionally, baseline clinical characteristics including advanced age and comorbid conditions, particularly cardiovascular disease and diabetes, increase the risk of severe exacerbations.17

One meta-analysis of placebo-controlled trials found that patients with severe exacerbations were likely to benefit from antibiotic therapy, while patients with mild or moderate exacerbations had no reduction in treatment failure or mortality rates.18 Patients presenting with acute respiratory failure necessitating intensive care and/or ventilator support (noninvasive or invasive) have also been shown to benefit from antibiotics.19

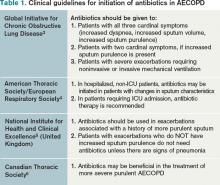

Current clinical guidelines vary slightly in their recommendations regarding when to give antibiotics in AECOPD (see Table 1). However, existing evidence favors antibiotic treatment for those patients presenting with two or three cardinal symptoms, specifically those with increased sputum purulence, and those with severe disease (i.e. pre-existing advanced airflow obstruction and/or exacerbations requiring mechanical ventilation). Conversely, studies have shown that many patients, particularly those with milder exacerbations, experience resolution of symptoms without antibiotic treatment.11,18

Antibiotic Choice in AECOPD

Risk stratification. In patients likely to benefit from antibiotic therapy, an understanding of the relationship between severity of COPD, host risk factors for poor outcomes, and microbiology is paramount to guide clinical decision-making. Historically, such bacteria as Haemophilus influenzae, Streptococcus pneumoniae, and Moraxella catarrhalis have been implicated in the pathogenesis of AECOPD.3,7 In patients with simple exacerbations, antibiotics that target these pathogens should be used (see Table 2).

However, patients with more severe underlying airway obstruction (i.e. FEV1<50%) and risk factors for poor outcomes, specifically recent hospitalization (≥2 days during the previous 90 days), frequent antibiotics (>3 courses during the previous year), and severe exacerbations are more likely to be infected with resistant strains or gram-negative organisms.3,7 Pseudomonas aeruginosa, in particular, is of increasing concern in this population. In patients with complicated exacerbations, more broad-coverage, empiric antibiotics should be initiated (see Table 2).

With this in mind, patients meeting criteria for treatment must first be stratified according to the severity of COPD and risk factors for poor outcomes before a decision regarding a specific antibiotic is reached. Figure 1 outlines a recommended approach for antibiotic administration in AECOPD. The optimal choice of antibiotics must consider cost-effectiveness, local patterns of antibiotic resistance, tissue penetration, patient adherence, and risk of such adverse drug events as diarrhea.

Comparative effectiveness. Current treatment guidelines do not favor the use of any particular antibiotic in simple AECOPD.3,4,5,6 However, as selective pressure has led to in vitro resistance to antibiotics traditionally considered first-line (e.g. doxycycline, trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole, amoxicillin), the use of second-line antibiotics (e.g. fluoroquinolones, macrolides, cephalosporins, β-lactam/ β-lactamase inhibitors) has increased. Consequently, several studies have compared the effectiveness of different antimicrobial regimens.

One meta-analysis found that second-line antibiotics, when compared with first-line agents, provided greater clinical improvement to patients with AECOPD, without significant differences in mortality, microbiologic eradication, or incidence of adverse drug events.20 Among the subgroup of trials enrolling hospitalized patients, the clinical effectiveness of second-line agents remained significantly greater than that of first-line agents.

Another meta-analysis compared trials that studied only macrolides, quinolones, and amoxicillin-clavulanate and found no difference in terms of short-term clinical effectiveness; however, there was weak evidence to suggest that quinolones were associated with better microbiological success and fewer recurrences of AECOPD.21 Fluoroquinolones are preferred in complicated cases of AECOPD in which there is a greater risk for enterobacteriaceae and Pseudomonas species.3,7

Antibiotic Duration

The duration of antibiotic therapy in AECOPD has been studied extensively, with randomized controlled trials consistently demonstrating no additional benefit to courses extending beyond five days. One meta-analysis of 21 studies found similar clinical and microbiologic cure rates among patients randomized to antibiotic treatment for ≤5 days versus >5 days.22 A subgroup analysis of the trials evaluating different durations of the same antibiotic also demonstrated no difference in clinical effectiveness, and this finding was confirmed in a separate meta-analysis.22,23

Advantages to shorter antibiotic courses include improved compliance and decreased rates of resistance. The usual duration of antibiotic therapy is three to seven days, depending upon the response to therapy.3

Back to the Case

As the patient has no significant comorbidities or risk factors, and meets criteria for a simple Anthonisen Type I exacerbation (increased dyspnea, sputum, and sputum purulence), antibiotic therapy with trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole is initiated on admission, in addition to the previously started steroid and bronchodilator treatments. The patient’s clinical status improves, and he is discharged on hospital Day 3 with a prescription to complete a five-day course of antibiotics.

Bottom Line

Antibiotic therapy is effective in select AECOPD patients, with maximal benefits obtained when the decision to treat is based on careful consideration of characteristic clinical symptoms and severity of illness. Choice and duration of antibiotics should follow likely bacterial causes and current guidelines.

Dr. Cunningham is an assistant professor of internal medicine and academic hospitalist in the section of hospital medicine at Vanderbilt University School of Medicine in Nashville, Tenn. Dr. LaBrin is assistant professor of internal medicine and pediatrics and an academic hospitalist at Vanderbilt. Dr. Markley is a clinical instructor and academic hospitalist at Vanderbilt.

References

- Donaldson GC, Wedzicha JA. COPD exacerbations: 1. Epidemiology. Thorax. 2006;61:164-168.

- National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. 2009 NHLBI Morbidity and Mortality Chartbook. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute website. Available at: http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/resources/docs/cht-book.htm Accessed Oct. 10, 2011.

- Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD). Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management and Prevention of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) website. Available at: www.goldcopd.org/guidelines-resources.html Accessed Oct. 10, 2011.

- Celli BR, MacNee W, Agusti A, et al. Standards for the diagnosis and treatment of patients with COPD: a summary of the ATS/ERS position paper. Eur Resp J. 2004;23:932-946.

- National Clinical Guideline Centre. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in adults in primary and secondary care. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence website. Available at: http://guidance.nice.org.uk/CG101/Guidance/pdf/English. Accessed Oct. 10, 2011.

- O’Donnell DE, Aaron S, Bourbeau J, et al. Canadian Thoracic Society recommendations for management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease—2007 update. Can Respir J. 2007;14(Suppl B):5B-32B.

- Sethi S, Murphy TF. Infection in the pathogenesis and course of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:2355-2565.

- Quon BS, Qi Gan W, Sin DD. Contemporary management of acute exacerbations of COPD: a systematic review and metaanalysis. Chest. 2008;133:756-766.

- Rothberg MB, Pekow PS, Lahti M, Brody O, Skiest DJ, Lindenauer PK. Antibiotic therapy and treatment failure in patients hospitalized for acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. JAMA. 2010;303:2035-2042.

- Roede BM, Bresser P, Bindels PJE, et al. Antibiotic treatment is associated with reduced risk of subsequent exacerbation in obstructive lung disease: a historical population based cohort study. Thorax. 2008;63:968-973.

- Anthonisen NR, Manfreda J, Warren CP, Hershfield ES, Harding GKM, Nelson NA. Antibiotic therapy in exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Ann Intern Med. 1987;106:196-204.

- Stockley RA, O’Brien C, Pye A, Hill SL. Relationship of sputum color to nature and outpatient management of acute exacerbations of COPD. Chest. 2000;117:1638-1645.

- Rosell A, Monso E, Soler N, et al. Microbiologic determinants of exacerbation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Arch Intern Med. 2005; 165:891-897.

- Stolz D, Christ-Crain M, Bingisser R, et al. Antibiotic treatment of exacerbations of COPD: a randomized, controlled trial comparing procalcitonin-guidance with standard therapy. Chest. 2007;131:9-19.

- Daniels JMA, Schoorl M, Snijders D, et al. Procalcitonin vs C-reactive protein as predictive markers of response to antibiotic therapy in acute exacerbations of COPD. Chest. 2010;138:1108-1015.

- Miravitlles M, Espinosa C, Fernandez-Laso E, Martos JA, Maldonado JA, Gallego M. Relationship between bacterial flora in sputum and functional impairment in patients with acute exacerbations of COPD. Chest. 1999;116:40-46.

- Patil SP, Krishnan JA, Lechtzin N, Diette GB. In-hospital mortality following acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:1180-1186.

- Puhan MA, Vollenweider D, Latshang T, Steurer J, Steurer-Stey C. Exacerbations of chronic obstructive lung disease: when are antibiotics indicated? A systematic review. Resp Res. 2007;8:30-40.

- Nouira S, Marghli S, Belghith M, Besbes L, Elatrous S, Abroug F. Once daily ofloxacin in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbation requiring mechanical ventilation: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2001;358:2020-2025.

- Dimopoulos G, Siempos II, Korbila IP, Manta KG, Falagas ME. Comparison of first-line with second-line antibiotics for acute exacerbations of chronic bronchitis: a metaanalysis of randomized controlled trials. Chest. 2007;132:447-455.

- Siempos II, Dimopoulos G, Korbila IP, Manta KG, Falagas ME. Macrolides, quinolones and amoxicillin/clavulanate for chronic bronchitis: a meta-analysis. Eur Resp J. 2007;29:1127-1137.

- El-Moussaoui, Roede BM, Speelman P, Bresser P, Prins JM, Bossuyt PMM. Short-course antibiotic treatment in acute exacerbations of chronic bronchitis and COPD: a meta-analysis of double-blind studies. Thorax. 2008;63:415-422.

- Falagas ME, Avgeri SG, Matthaiou DK, Dimopoulos G, Siempos II. Short- versus long-duration antimicrobial treatment for exacerbations of chronic bronchitis: a meta-analysis. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2008;62:442-450.

Case

A 58-year-old male smoker with moderate chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) (FEV1 56% predicted) is admitted with an acute exacerbation of COPD for the second time this year. He presented to the ED with increased productive cough and shortness of breath, similar to prior exacerbations. He denies fevers, myalgias, or upper-respiratory symptoms. Physical exam is notable for bilateral inspiratory and expiratory wheezing. His sputum is purulent. He is given continuous nebulizer therapy and one dose of oral prednisone, but his dyspnea and wheezing persist. Chest X-ray does not reveal an infiltrate.

Should this patient be treated with antibiotics and, if so, what regimen is most appropriate?

Overview

Acute exacerbations of COPD (AECOPD) present a major health burden, accounting for more than 2.4% of all hospital admissions and causing significant morbidity, mortality, and costs.1 During 2006 and 2007, COPD mortality in the United States topped 39 deaths per 100,000 people, and more recently, hospital costs related to COPD were expected to exceed $13 billion annually.2 Patients with AECOPD also experience decreased quality of life and faster decline in pulmonary function, further highlighting the need for timely and appropriate treatment.1

Several guidelines have proposed treatment strategies now considered standard of care in AECOPD management.3,4,5,6 These include the use of corticosteroids, bronchodilator agents, and, in select cases, antibiotics. While there is well-established evidence for the use of steroids and bronchodilators in AECOPD, the debate continues over the appropriate use of antibiotics in the treatment of acute exacerbations. There are multiple potential factors leading to AECOPD, including viruses, bacteria, and common pollutants; as such, antibiotic treatment may not be indicated for all patients presenting with exacerbations. Further, the risks of antibiotic treatment—including adverse drug events, selection for drug-resistant bacteria, and associated costs—are not insignificant.

However, bacterial infections do play a role in approximately 50% of patients with AECOPD and, for this population, use of antibiotics may confer important benefits.7

Interestingly, a retrospective cohort study of 84,621 patients admitted for AECOPD demonstrated that 85% of patients received antibiotics at some point during hospitalization.8

Support for Antibiotics

Several randomized trials have compared clinical outcomes in patients with AECOPD who have received antibiotics versus those who received placebos. Most of these had small sample sizes and studied only ββ-lactam and tetracycline antibiotics in an outpatient setting; there are limited data involving inpatients and newer drugs. Nevertheless, antibiotic treatment has been associated with decreased risk of adverse outcomes in AECOPD.

One meta-analysis demonstrated that antibiotics reduced treatment failures by 66% and in-hospital mortality by 78% in the subset of trials involving hospitalized patients.8 Similarly, analysis of a large retrospective cohort of patients hospitalized for AECOPD found a significantly lower risk of treatment failure in antibiotic-treated versus untreated patients.9 Specifically, treated patients had lower rates of in-hospital mortality and readmission for AECOPD and a lower likelihood of requiring subsequent mechanical ventilation during the index hospitalization.

Data also suggest that antibiotic treatment during exacerbations might favorably impact subsequent exacerbations.10 A retrospective study of 18,928 Dutch patients with AECOPD compared outcomes among patients who had received antibiotics (most frequently doxycycline or a penicillin) as part of their therapy to those who did not. The authors demonstrated that the median time to the next exacerbation was significantly longer in the patients receiving antibiotics.10 Further, both mortality and overall risk of developing a subsequent exacerbation were significantly decreased in the antibiotic group, with median follow-up of approximately two years.

Indications for Antibiotics

Clinical symptoms. A landmark study by Anthonisen and colleagues set forth three clinical criteria that have formed the basis for treating AECOPD with antibiotics in subsequent studies and in clinical practice.11 Often referred to as the “cardinal symptoms” of AECOPD, these include increased dyspnea, sputum volume, and sputum purulence. In this study, 173 outpatients with COPD were randomized to a 10-day course of antibiotics or placebo at onset of an exacerbation and followed clinically. The authors found that antibiotic-treated patients were significantly more likely than the placebo group to achieve treatment success, defined as resolution of all exacerbated symptoms within 21 days (68.1% vs. 55.0%, P<0.01).

Importantly, treated patients were also significantly less likely to experience clinical deterioration after 72 hours (9.9% vs. 18.9%, P<0.05). Patients with Type I exacerbations, characterized by all three cardinal symptoms, were most likely to benefit from antibiotic therapy, followed by patients with Type II exacerbations, in whom only two of the symptoms were present. Subsequent studies have suggested that sputum purulence correlates well with the presence of acute bacterial infection and therefore may be a reliable clinical indicator of patients who are likely to benefit from antibiotic therapy.12

Laboratory data. While sputum purulence is associated with bacterial infection, sputum culture is less reliable, as pathogenic bacteria are commonly isolated from patients with both AECOPD and stable COPD. In fact, the prevalence of bacterial colonization in moderate to severe COPD might be as high as 50%.13 Therefore, a positive bacterial sputum culture, in the absence of purulence or other signs of infection, is not recommended as the sole basis for which to prescribe antibiotics.

Serum biomarkers, most notably C-reactive protein (CRP) and procalcitonin, have been studied as a newer approach to identify patients who might benefit from antibiotic therapy for AECOPD. Studies have demonstrated increased CRP levels during AECOPD, particularly in patients with purulent sputum and positive bacterial sputum cultures.12 Procalcitonin is preferentially elevated in bacterial infections.

One randomized, placebo-controlled trial in hospitalized patients with AECOPD demonstrated a significant reduction in antibiotic usage based on low procalcitonin levels, without negatively impacting clinical success rate, hospital mortality, subsequent antibiotic needs, or time to next exacerbation.14 However, due to inconsistent evidence, use of these markers to guide antibiotic administration in AECOPD has not yet been definitively established.14,15 Additionally, these laboratory results are often not available at the point of care, potentially limiting their utility in the decision to initiate antibiotics.

Severity of illness. Severity of illness is an important factor in the decision to treat AECOPD with antibiotics. Patients with advanced, underlying airway obstruction, as measured by FEV1, are more likely to have a bacterial cause of AECOPD.16 Additionally, baseline clinical characteristics including advanced age and comorbid conditions, particularly cardiovascular disease and diabetes, increase the risk of severe exacerbations.17

One meta-analysis of placebo-controlled trials found that patients with severe exacerbations were likely to benefit from antibiotic therapy, while patients with mild or moderate exacerbations had no reduction in treatment failure or mortality rates.18 Patients presenting with acute respiratory failure necessitating intensive care and/or ventilator support (noninvasive or invasive) have also been shown to benefit from antibiotics.19

Current clinical guidelines vary slightly in their recommendations regarding when to give antibiotics in AECOPD (see Table 1). However, existing evidence favors antibiotic treatment for those patients presenting with two or three cardinal symptoms, specifically those with increased sputum purulence, and those with severe disease (i.e. pre-existing advanced airflow obstruction and/or exacerbations requiring mechanical ventilation). Conversely, studies have shown that many patients, particularly those with milder exacerbations, experience resolution of symptoms without antibiotic treatment.11,18

Antibiotic Choice in AECOPD

Risk stratification. In patients likely to benefit from antibiotic therapy, an understanding of the relationship between severity of COPD, host risk factors for poor outcomes, and microbiology is paramount to guide clinical decision-making. Historically, such bacteria as Haemophilus influenzae, Streptococcus pneumoniae, and Moraxella catarrhalis have been implicated in the pathogenesis of AECOPD.3,7 In patients with simple exacerbations, antibiotics that target these pathogens should be used (see Table 2).

However, patients with more severe underlying airway obstruction (i.e. FEV1<50%) and risk factors for poor outcomes, specifically recent hospitalization (≥2 days during the previous 90 days), frequent antibiotics (>3 courses during the previous year), and severe exacerbations are more likely to be infected with resistant strains or gram-negative organisms.3,7 Pseudomonas aeruginosa, in particular, is of increasing concern in this population. In patients with complicated exacerbations, more broad-coverage, empiric antibiotics should be initiated (see Table 2).

With this in mind, patients meeting criteria for treatment must first be stratified according to the severity of COPD and risk factors for poor outcomes before a decision regarding a specific antibiotic is reached. Figure 1 outlines a recommended approach for antibiotic administration in AECOPD. The optimal choice of antibiotics must consider cost-effectiveness, local patterns of antibiotic resistance, tissue penetration, patient adherence, and risk of such adverse drug events as diarrhea.

Comparative effectiveness. Current treatment guidelines do not favor the use of any particular antibiotic in simple AECOPD.3,4,5,6 However, as selective pressure has led to in vitro resistance to antibiotics traditionally considered first-line (e.g. doxycycline, trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole, amoxicillin), the use of second-line antibiotics (e.g. fluoroquinolones, macrolides, cephalosporins, β-lactam/ β-lactamase inhibitors) has increased. Consequently, several studies have compared the effectiveness of different antimicrobial regimens.

One meta-analysis found that second-line antibiotics, when compared with first-line agents, provided greater clinical improvement to patients with AECOPD, without significant differences in mortality, microbiologic eradication, or incidence of adverse drug events.20 Among the subgroup of trials enrolling hospitalized patients, the clinical effectiveness of second-line agents remained significantly greater than that of first-line agents.

Another meta-analysis compared trials that studied only macrolides, quinolones, and amoxicillin-clavulanate and found no difference in terms of short-term clinical effectiveness; however, there was weak evidence to suggest that quinolones were associated with better microbiological success and fewer recurrences of AECOPD.21 Fluoroquinolones are preferred in complicated cases of AECOPD in which there is a greater risk for enterobacteriaceae and Pseudomonas species.3,7

Antibiotic Duration

The duration of antibiotic therapy in AECOPD has been studied extensively, with randomized controlled trials consistently demonstrating no additional benefit to courses extending beyond five days. One meta-analysis of 21 studies found similar clinical and microbiologic cure rates among patients randomized to antibiotic treatment for ≤5 days versus >5 days.22 A subgroup analysis of the trials evaluating different durations of the same antibiotic also demonstrated no difference in clinical effectiveness, and this finding was confirmed in a separate meta-analysis.22,23

Advantages to shorter antibiotic courses include improved compliance and decreased rates of resistance. The usual duration of antibiotic therapy is three to seven days, depending upon the response to therapy.3

Back to the Case

As the patient has no significant comorbidities or risk factors, and meets criteria for a simple Anthonisen Type I exacerbation (increased dyspnea, sputum, and sputum purulence), antibiotic therapy with trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole is initiated on admission, in addition to the previously started steroid and bronchodilator treatments. The patient’s clinical status improves, and he is discharged on hospital Day 3 with a prescription to complete a five-day course of antibiotics.

Bottom Line

Antibiotic therapy is effective in select AECOPD patients, with maximal benefits obtained when the decision to treat is based on careful consideration of characteristic clinical symptoms and severity of illness. Choice and duration of antibiotics should follow likely bacterial causes and current guidelines.

Dr. Cunningham is an assistant professor of internal medicine and academic hospitalist in the section of hospital medicine at Vanderbilt University School of Medicine in Nashville, Tenn. Dr. LaBrin is assistant professor of internal medicine and pediatrics and an academic hospitalist at Vanderbilt. Dr. Markley is a clinical instructor and academic hospitalist at Vanderbilt.

References

- Donaldson GC, Wedzicha JA. COPD exacerbations: 1. Epidemiology. Thorax. 2006;61:164-168.

- National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. 2009 NHLBI Morbidity and Mortality Chartbook. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute website. Available at: http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/resources/docs/cht-book.htm Accessed Oct. 10, 2011.

- Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD). Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management and Prevention of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) website. Available at: www.goldcopd.org/guidelines-resources.html Accessed Oct. 10, 2011.

- Celli BR, MacNee W, Agusti A, et al. Standards for the diagnosis and treatment of patients with COPD: a summary of the ATS/ERS position paper. Eur Resp J. 2004;23:932-946.

- National Clinical Guideline Centre. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in adults in primary and secondary care. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence website. Available at: http://guidance.nice.org.uk/CG101/Guidance/pdf/English. Accessed Oct. 10, 2011.

- O’Donnell DE, Aaron S, Bourbeau J, et al. Canadian Thoracic Society recommendations for management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease—2007 update. Can Respir J. 2007;14(Suppl B):5B-32B.

- Sethi S, Murphy TF. Infection in the pathogenesis and course of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:2355-2565.

- Quon BS, Qi Gan W, Sin DD. Contemporary management of acute exacerbations of COPD: a systematic review and metaanalysis. Chest. 2008;133:756-766.

- Rothberg MB, Pekow PS, Lahti M, Brody O, Skiest DJ, Lindenauer PK. Antibiotic therapy and treatment failure in patients hospitalized for acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. JAMA. 2010;303:2035-2042.

- Roede BM, Bresser P, Bindels PJE, et al. Antibiotic treatment is associated with reduced risk of subsequent exacerbation in obstructive lung disease: a historical population based cohort study. Thorax. 2008;63:968-973.

- Anthonisen NR, Manfreda J, Warren CP, Hershfield ES, Harding GKM, Nelson NA. Antibiotic therapy in exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Ann Intern Med. 1987;106:196-204.

- Stockley RA, O’Brien C, Pye A, Hill SL. Relationship of sputum color to nature and outpatient management of acute exacerbations of COPD. Chest. 2000;117:1638-1645.

- Rosell A, Monso E, Soler N, et al. Microbiologic determinants of exacerbation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Arch Intern Med. 2005; 165:891-897.

- Stolz D, Christ-Crain M, Bingisser R, et al. Antibiotic treatment of exacerbations of COPD: a randomized, controlled trial comparing procalcitonin-guidance with standard therapy. Chest. 2007;131:9-19.

- Daniels JMA, Schoorl M, Snijders D, et al. Procalcitonin vs C-reactive protein as predictive markers of response to antibiotic therapy in acute exacerbations of COPD. Chest. 2010;138:1108-1015.

- Miravitlles M, Espinosa C, Fernandez-Laso E, Martos JA, Maldonado JA, Gallego M. Relationship between bacterial flora in sputum and functional impairment in patients with acute exacerbations of COPD. Chest. 1999;116:40-46.

- Patil SP, Krishnan JA, Lechtzin N, Diette GB. In-hospital mortality following acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:1180-1186.

- Puhan MA, Vollenweider D, Latshang T, Steurer J, Steurer-Stey C. Exacerbations of chronic obstructive lung disease: when are antibiotics indicated? A systematic review. Resp Res. 2007;8:30-40.

- Nouira S, Marghli S, Belghith M, Besbes L, Elatrous S, Abroug F. Once daily ofloxacin in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbation requiring mechanical ventilation: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2001;358:2020-2025.

- Dimopoulos G, Siempos II, Korbila IP, Manta KG, Falagas ME. Comparison of first-line with second-line antibiotics for acute exacerbations of chronic bronchitis: a metaanalysis of randomized controlled trials. Chest. 2007;132:447-455.

- Siempos II, Dimopoulos G, Korbila IP, Manta KG, Falagas ME. Macrolides, quinolones and amoxicillin/clavulanate for chronic bronchitis: a meta-analysis. Eur Resp J. 2007;29:1127-1137.

- El-Moussaoui, Roede BM, Speelman P, Bresser P, Prins JM, Bossuyt PMM. Short-course antibiotic treatment in acute exacerbations of chronic bronchitis and COPD: a meta-analysis of double-blind studies. Thorax. 2008;63:415-422.

- Falagas ME, Avgeri SG, Matthaiou DK, Dimopoulos G, Siempos II. Short- versus long-duration antimicrobial treatment for exacerbations of chronic bronchitis: a meta-analysis. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2008;62:442-450.

Case

A 58-year-old male smoker with moderate chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) (FEV1 56% predicted) is admitted with an acute exacerbation of COPD for the second time this year. He presented to the ED with increased productive cough and shortness of breath, similar to prior exacerbations. He denies fevers, myalgias, or upper-respiratory symptoms. Physical exam is notable for bilateral inspiratory and expiratory wheezing. His sputum is purulent. He is given continuous nebulizer therapy and one dose of oral prednisone, but his dyspnea and wheezing persist. Chest X-ray does not reveal an infiltrate.

Should this patient be treated with antibiotics and, if so, what regimen is most appropriate?

Overview

Acute exacerbations of COPD (AECOPD) present a major health burden, accounting for more than 2.4% of all hospital admissions and causing significant morbidity, mortality, and costs.1 During 2006 and 2007, COPD mortality in the United States topped 39 deaths per 100,000 people, and more recently, hospital costs related to COPD were expected to exceed $13 billion annually.2 Patients with AECOPD also experience decreased quality of life and faster decline in pulmonary function, further highlighting the need for timely and appropriate treatment.1

Several guidelines have proposed treatment strategies now considered standard of care in AECOPD management.3,4,5,6 These include the use of corticosteroids, bronchodilator agents, and, in select cases, antibiotics. While there is well-established evidence for the use of steroids and bronchodilators in AECOPD, the debate continues over the appropriate use of antibiotics in the treatment of acute exacerbations. There are multiple potential factors leading to AECOPD, including viruses, bacteria, and common pollutants; as such, antibiotic treatment may not be indicated for all patients presenting with exacerbations. Further, the risks of antibiotic treatment—including adverse drug events, selection for drug-resistant bacteria, and associated costs—are not insignificant.

However, bacterial infections do play a role in approximately 50% of patients with AECOPD and, for this population, use of antibiotics may confer important benefits.7

Interestingly, a retrospective cohort study of 84,621 patients admitted for AECOPD demonstrated that 85% of patients received antibiotics at some point during hospitalization.8

Support for Antibiotics

Several randomized trials have compared clinical outcomes in patients with AECOPD who have received antibiotics versus those who received placebos. Most of these had small sample sizes and studied only ββ-lactam and tetracycline antibiotics in an outpatient setting; there are limited data involving inpatients and newer drugs. Nevertheless, antibiotic treatment has been associated with decreased risk of adverse outcomes in AECOPD.

One meta-analysis demonstrated that antibiotics reduced treatment failures by 66% and in-hospital mortality by 78% in the subset of trials involving hospitalized patients.8 Similarly, analysis of a large retrospective cohort of patients hospitalized for AECOPD found a significantly lower risk of treatment failure in antibiotic-treated versus untreated patients.9 Specifically, treated patients had lower rates of in-hospital mortality and readmission for AECOPD and a lower likelihood of requiring subsequent mechanical ventilation during the index hospitalization.

Data also suggest that antibiotic treatment during exacerbations might favorably impact subsequent exacerbations.10 A retrospective study of 18,928 Dutch patients with AECOPD compared outcomes among patients who had received antibiotics (most frequently doxycycline or a penicillin) as part of their therapy to those who did not. The authors demonstrated that the median time to the next exacerbation was significantly longer in the patients receiving antibiotics.10 Further, both mortality and overall risk of developing a subsequent exacerbation were significantly decreased in the antibiotic group, with median follow-up of approximately two years.

Indications for Antibiotics

Clinical symptoms. A landmark study by Anthonisen and colleagues set forth three clinical criteria that have formed the basis for treating AECOPD with antibiotics in subsequent studies and in clinical practice.11 Often referred to as the “cardinal symptoms” of AECOPD, these include increased dyspnea, sputum volume, and sputum purulence. In this study, 173 outpatients with COPD were randomized to a 10-day course of antibiotics or placebo at onset of an exacerbation and followed clinically. The authors found that antibiotic-treated patients were significantly more likely than the placebo group to achieve treatment success, defined as resolution of all exacerbated symptoms within 21 days (68.1% vs. 55.0%, P<0.01).

Importantly, treated patients were also significantly less likely to experience clinical deterioration after 72 hours (9.9% vs. 18.9%, P<0.05). Patients with Type I exacerbations, characterized by all three cardinal symptoms, were most likely to benefit from antibiotic therapy, followed by patients with Type II exacerbations, in whom only two of the symptoms were present. Subsequent studies have suggested that sputum purulence correlates well with the presence of acute bacterial infection and therefore may be a reliable clinical indicator of patients who are likely to benefit from antibiotic therapy.12

Laboratory data. While sputum purulence is associated with bacterial infection, sputum culture is less reliable, as pathogenic bacteria are commonly isolated from patients with both AECOPD and stable COPD. In fact, the prevalence of bacterial colonization in moderate to severe COPD might be as high as 50%.13 Therefore, a positive bacterial sputum culture, in the absence of purulence or other signs of infection, is not recommended as the sole basis for which to prescribe antibiotics.

Serum biomarkers, most notably C-reactive protein (CRP) and procalcitonin, have been studied as a newer approach to identify patients who might benefit from antibiotic therapy for AECOPD. Studies have demonstrated increased CRP levels during AECOPD, particularly in patients with purulent sputum and positive bacterial sputum cultures.12 Procalcitonin is preferentially elevated in bacterial infections.

One randomized, placebo-controlled trial in hospitalized patients with AECOPD demonstrated a significant reduction in antibiotic usage based on low procalcitonin levels, without negatively impacting clinical success rate, hospital mortality, subsequent antibiotic needs, or time to next exacerbation.14 However, due to inconsistent evidence, use of these markers to guide antibiotic administration in AECOPD has not yet been definitively established.14,15 Additionally, these laboratory results are often not available at the point of care, potentially limiting their utility in the decision to initiate antibiotics.

Severity of illness. Severity of illness is an important factor in the decision to treat AECOPD with antibiotics. Patients with advanced, underlying airway obstruction, as measured by FEV1, are more likely to have a bacterial cause of AECOPD.16 Additionally, baseline clinical characteristics including advanced age and comorbid conditions, particularly cardiovascular disease and diabetes, increase the risk of severe exacerbations.17

One meta-analysis of placebo-controlled trials found that patients with severe exacerbations were likely to benefit from antibiotic therapy, while patients with mild or moderate exacerbations had no reduction in treatment failure or mortality rates.18 Patients presenting with acute respiratory failure necessitating intensive care and/or ventilator support (noninvasive or invasive) have also been shown to benefit from antibiotics.19

Current clinical guidelines vary slightly in their recommendations regarding when to give antibiotics in AECOPD (see Table 1). However, existing evidence favors antibiotic treatment for those patients presenting with two or three cardinal symptoms, specifically those with increased sputum purulence, and those with severe disease (i.e. pre-existing advanced airflow obstruction and/or exacerbations requiring mechanical ventilation). Conversely, studies have shown that many patients, particularly those with milder exacerbations, experience resolution of symptoms without antibiotic treatment.11,18

Antibiotic Choice in AECOPD

Risk stratification. In patients likely to benefit from antibiotic therapy, an understanding of the relationship between severity of COPD, host risk factors for poor outcomes, and microbiology is paramount to guide clinical decision-making. Historically, such bacteria as Haemophilus influenzae, Streptococcus pneumoniae, and Moraxella catarrhalis have been implicated in the pathogenesis of AECOPD.3,7 In patients with simple exacerbations, antibiotics that target these pathogens should be used (see Table 2).

However, patients with more severe underlying airway obstruction (i.e. FEV1<50%) and risk factors for poor outcomes, specifically recent hospitalization (≥2 days during the previous 90 days), frequent antibiotics (>3 courses during the previous year), and severe exacerbations are more likely to be infected with resistant strains or gram-negative organisms.3,7 Pseudomonas aeruginosa, in particular, is of increasing concern in this population. In patients with complicated exacerbations, more broad-coverage, empiric antibiotics should be initiated (see Table 2).

With this in mind, patients meeting criteria for treatment must first be stratified according to the severity of COPD and risk factors for poor outcomes before a decision regarding a specific antibiotic is reached. Figure 1 outlines a recommended approach for antibiotic administration in AECOPD. The optimal choice of antibiotics must consider cost-effectiveness, local patterns of antibiotic resistance, tissue penetration, patient adherence, and risk of such adverse drug events as diarrhea.

Comparative effectiveness. Current treatment guidelines do not favor the use of any particular antibiotic in simple AECOPD.3,4,5,6 However, as selective pressure has led to in vitro resistance to antibiotics traditionally considered first-line (e.g. doxycycline, trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole, amoxicillin), the use of second-line antibiotics (e.g. fluoroquinolones, macrolides, cephalosporins, β-lactam/ β-lactamase inhibitors) has increased. Consequently, several studies have compared the effectiveness of different antimicrobial regimens.

One meta-analysis found that second-line antibiotics, when compared with first-line agents, provided greater clinical improvement to patients with AECOPD, without significant differences in mortality, microbiologic eradication, or incidence of adverse drug events.20 Among the subgroup of trials enrolling hospitalized patients, the clinical effectiveness of second-line agents remained significantly greater than that of first-line agents.

Another meta-analysis compared trials that studied only macrolides, quinolones, and amoxicillin-clavulanate and found no difference in terms of short-term clinical effectiveness; however, there was weak evidence to suggest that quinolones were associated with better microbiological success and fewer recurrences of AECOPD.21 Fluoroquinolones are preferred in complicated cases of AECOPD in which there is a greater risk for enterobacteriaceae and Pseudomonas species.3,7

Antibiotic Duration

The duration of antibiotic therapy in AECOPD has been studied extensively, with randomized controlled trials consistently demonstrating no additional benefit to courses extending beyond five days. One meta-analysis of 21 studies found similar clinical and microbiologic cure rates among patients randomized to antibiotic treatment for ≤5 days versus >5 days.22 A subgroup analysis of the trials evaluating different durations of the same antibiotic also demonstrated no difference in clinical effectiveness, and this finding was confirmed in a separate meta-analysis.22,23

Advantages to shorter antibiotic courses include improved compliance and decreased rates of resistance. The usual duration of antibiotic therapy is three to seven days, depending upon the response to therapy.3

Back to the Case