User login

A multidisciplinary approach to gyn care: A single center’s experience

In her book The Silo Effect: The Peril of Expertise and the Promise of Breaking Down Barriers, Gillian Tett wrote that “the word ‘silo’ does not just refer to a physical structure or organization (such as a department). It can also be a state of mind. Silos exist in structures. But they exist in our minds and social groups too. Silos breed tribalism. But they can also go hand in hand with tunnel vision.”

Tertiary care referral centers seem to be trending toward being more and more “un-siloed” and collaborative within their own departments and between departments in order to care for patients. The terms multidisciplinary and intradisciplinary have become popular in medicine, and teams are joining forces to create care paths for patients that are intended to improve the efficiency of and the quality of care that is rendered. There is no better example of the move to improve collaboration in medicine than the theme of the 2021 Society of Gynecologic Surgeons annual meeting, “Working Together: How Collaboration Enables Us to Better Help Our Patients.”

In this article, we provide examples of how collaborating with other specialties—within and outside of an ObGyn department—should become the standard of care. We discuss how to make this team approach easier and provide evidence that patients experience favorable outcomes. While data on combined care remain sparse, the existing literature on this topic helps us to guide and counsel patients about what to expect when a combined approach is taken.

Addressing pelvic floor disorders in women with gynecologic malignancy

In 2018, authors of a systematic review that looked at concurrent pelvic floor disorders in gynecologic oncologic survivors found that the prevalence of these disorders was high enough to warrant evaluation and management of these conditions to help improve quality of life for patients.1 Furthermore, it is possible that the prevalence of urinary incontinence is higher in patients who have undergone surgery for a gynecologic malignancy compared with controls, which has been reported in previous studies.2,3 At Cleveland Clinic, we recognize the need to evaluate our patients receiving oncologic care for urinary, fecal, and pelvic organ prolapse symptoms. Our oncologists routinely inquire about these symptoms once their patients have undergone surgery with them, and they make referrals for all their symptomatic patients. They have even learned about our own counseling, and they pre-emptively let patients know what our counseling may encompass.

For instance, many patients who received radiation therapy have stress urinary incontinence that is likely related to a hypomobile urethra, and they may benefit more from transurethral bulking than an anti-incontinence procedure in the operating room. Reassuring patients ahead of time that they do not need major interventions for their symptoms is helpful, as these patients are already experiencing tremendous burden from their oncologic conditions. We have made our referral patterns easy for these patients, and most patients are seen within days to weeks of the referral placed, depending on the urgency of the consult and the need to proceed with their oncologic treatment plan.

Gynecologic oncology patients who present with preoperative stress urinary incontinence and pelvic organ prolapse also are referred to a urogynecology specialist for concurrent care. Care paths have been created to help inform both the urogynecologists and the oncologists about options for patients depending on their respective conditions, as both their malignancy and their pelvic floor disorder(s) are considered in treatment planning. There is agreement in this planning that the oncologic surgery takes priority, and the urogynecologic approach is based on the oncologic plan.

Our urogynecologists routinely ask if future radiation is in the treatment plan, as this usually precludes us from placing a midurethral sling at the time of any surgery. Surgical approach (vaginal versus abdominal; open or minimally invasive) also is determined by the oncologic team. At the time of surgery, patient positioning is considered to optimize access for all of the surgeons. For instance, having the oncologist know that the patient needs to be far down on the bed as their steep Trendelenburg positioning during laparoscopy or robotic surgery may cause the patient to slide cephalad during the case may make a vaginal repair or sling placement at the end of the case challenging. All these small nuances are important, and a collaborative team develops the right plan for each patient in advance.

Data on the outcomes of combined surgery are sparse. In a retrospective matched cohort study, our group compared outcomes in women who underwent concurrent surgery with those who underwent urogynecologic surgery alone.4 We found that concurrent surgeries had an increased incidence of minor but not serious perioperative adverse events. Importantly, we determined that 1 in 10 planned urogynecologic procedures needed to be either modified or abandoned as a result of the oncologic plan. These data help guide our counseling, and both the oncologist and urogynecologist contributing to the combined case counsel patients according to these data.

Continue to: Concurrent colorectal and gynecologic surgery...

Concurrent colorectal and gynecologic surgery

Many women have pelvic floor disorders. As gynecologists, we often compartmentalize these conditions as gynecologic problems; frequently, however, colorectal conditions are at play as well and should be addressed concurrently. For instance, a high incidence of anorectal dysfunction occurs in women who present with pelvic organ prolapse.5 Furthermore, outlet defecation disorders are not always a result of a straightforward rectocele that can be fixed vaginally. Sometimes, a more thorough evaluation is warranted depending on the patient’s concurrent symptoms and history. Outlet symptoms may be attributed to large enteroceles, sigmoidoceles, perineal descent, rectal intussusception, and rectal prolapse.6

As a result, a combined approach to caring for patients with complex pelvic floor disorders is optimal. Several studies describe this type of combined and coordinated patient care.7,8 Ideally, patients are seen by both surgeons in the office so that the surgeons may make a combined plan for their care, especially if the decision is made to proceed with surgery. Urogynecology specialists and colorectal surgeons must decide together whether to approach combined prolapse procedures via a perineal and vaginal approach versus an abdominal approach. Several factors can determine this, including surgeon experience and preference, which is why it is important for surgeons working together to have either well-designed care paths or simply open communication and experience working together for the conditions they are treating.

In an ideal coordinated care approach, both surgeons review the patient records in advance. Any needed imaging or testing is done before the official patient consult; the patient is then seen by both clinicians in the same visit and counseled about the options. This is the most efficient and effective way to see patients, and we have had significant success using this approach.

Complications of combined surgery

The safety of combining procedures such as laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy and concurrent rectopexy has been studied, and intraoperative complications have been reported to be low.9,10 In a cohort study, Wallace and colleagues looked at postoperative outcomes and complications following combined surgery and reported that reoperation for the rectal prolapse component of the surgery was more common than the pelvic organ prolapse component, and that 1 in 5 of their patients experienced a surgical complication within 30 days of their surgery.11 This incidence is higher than that seen with isolated pelvic organ prolapse surgery. These data help us understand that a combined approach requires good patient counseling in the office about both the need for repeat surgery in certain circumstances and the increased risk of complications. Further, combined perineal and vaginal approaches have been compared with abdominal approaches and also have shown no age-adjusted differences in outcomes and complications.12

These data point to the need for surgeons to choose the approach to surgery that best fits their own experiences and to discuss this together before counseling the patient in the office, thus streamlining the effort so that the patient feels comfortable under the care of 2 surgeons.

Patients presenting with urogynecologic and gynecologic conditions also report symptomatic hemorrhoids, and colorectal referral is often made by the gynecologist. Sparse data are available regarding combined approaches to managing hemorrhoids and gynecologic conditions. Our group was the first to publish on outcomes and complications in patients undergoing concurrent hemorrhoidectomy at the time of urogynecologic surgery.13 In that retrospective cohort, we found that minor complications, such as postoperative urinary tract infection and transient voiding dysfunction, was more common in patients who underwent combined surgery. From this, we gathered that there is a need to counsel patients appropriately about the risk of combined surgery. That said, for some patients, coordinated care is desirable, and surgeons should make the effort to work together in combining their procedures.

Continue to: Integrating plastic and reconstructive surgery in gynecology...

Integrating plastic and reconstructive surgery in gynecology

Reconstructive gynecologic procedures often require a multidisciplinary approach to what can be very complex reconstructive surgery. The intended goal usually is to achieve a good cosmetic result in the genital area, as well as to restore sexual, defecatory, and/or genitourinary functionality. As a result, surgeons must work together to develop a feasible reconstructive plan for these patients.

Women experience vaginal stenosis or foreshortening for a number of reasons. Women with congenital anomalies often are cared for by specialists in pediatric and adolescent gynecology. Other women, such as those who have undergone vaginectomy and/or pelvic or vaginal radiation for cancer treatment, complications from vaginal mesh placement, and severe vaginal scarring from dermatologic conditions like lichen planus, are cared for by other gynecologic specialists, often general gynecologists or urogynecologists. In some of these cases, a gynecologic surgeon can perform vaginal adhesiolysis followed by vaginal estrogen treatment (when appropriate) and aggressive postoperative vaginal dilation with adjunctive pelvic floor physical therapy as well as sex therapy or counseling. A simple reconstructive approach may be necessary if lysis of adhesions alone is not sufficient. Sometimes, the vaginal apex must be opened vaginally or abdominally, or releasing incisions need to be made to improve the caliber of the vagina in addition to its length. Under these circumstances, the use of additional local skin grafts, local peritoneal flaps, or biologic grafts or xenografts can help achieve a satisfying result. While not all gynecologists are trained to perform these procedures, some are, and certainly gynecologic subspecialists have the skill sets to care for these patients.

Under other circumstances, when the vagina is truly foreshortened, more aggressive reconstructive surgery is necessary and consultation and collaboration with plastic surgery specialists often is helpful. At our center, these patients’ care is initially managed by gynecologists and, when simple approaches to their reconstructive needs are exhausted, collaboration is warranted. As with the other team approaches discussed in this article, the recommendation is for a consistent referral team that has established care paths for patients. Not all plastic surgeons are familiar with neovaginal reconstruction and understand the functional aspects that gynecologists are hoping to achieve for their patients. Therefore, it is important to form cohesive teams that have the same goals for the patient.

The literature on neovaginal reconstruction is sparse. There are no true agreed on approaches or techniques for vaginal reconstruction because there is no “one size fits all” for these repairs. Defects also vary depending on whether they are due to resections or radiation for oncologic treatment, reconstruction as part of the repair of a genitourinary or rectovaginal fistula, or stenosis from other etiologies.

In 2002, Cordeiro and colleagues published a classification system and reconstructive algorithm for acquired vaginal defects.14 Not all reconstructive surgeons subscribe to this algorithm, but it is the only rubric that currently exists. The authors differentiate between “partial” and “circumferential” defects and recommend different types of fasciocutaneous and myocutaneous flaps for reconstruction.

In our experience at our center, we believe that the choice of flap should also depend on whether or not perineal reconstruction is needed. This decision is made by both the gynecologic specialist and the plastic surgeon. Common flap choices include the Singapore flap, a fasciocutaneous flap based on perforators from the pudendal vessels; the gracilis flap, a myocutaneous flap based off the medial circumflex femoral vessels; and the rectus abdominis flap (transverse or vertical), which is also a myocutaneous flap that relies on the blood supply from the deep inferior epigastric vessels.

One of the most important parts of the coordinated effort of neovaginal surgery is postoperative care. Plastic surgeons play a key role in ensuring that the flap survives in the immediate postoperative period. The gynecology team should be responsible for postoperative vaginal dilation teaching and follow-up to ensure that the patient dilates properly and upsizes her dilator appropriately over the postoperative period. In our practice, our advanced practice clinicians often care for these patients and are responsible for continuity and dilation teaching. Patients have easy access to these clinicians, and this enhances the postoperative experience. Referral to a pelvic floor physical therapist knowledgeable about neovaginal surgery also helps to ensure that the dilation process goes successfully. It also helps to have office days on the same days as the plastic surgery team that is following the patient. This way, the patient may be seen by both teams on the same day. This allows for good patient communication with regard to aftercare, as well as a combined approach to teaching the trainees involved in the case. Coordination with pelvic floor physical therapists on those days also enhances the patient experience and is highly recommended.

Continue to: Combining gyn and urogyn procedures with plastic surgery...

Combining gyn and urogyn procedures with plastic surgery

While there are no data on combining gynecologic and urogynecologic procedures with plastic reconstructive surgeries, a team approach to combining surgeries is possible. At our center, we have performed tubal ligation, ovarian surgery, hysterectomy, and sling and prolapse surgery in patients who were undergoing cosmetic procedures, such as breast augmentation and abdominoplasty.

Gender affirmation surgery also can be performed through a combined approach between gynecologists and plastic surgeons. Our gynecologists perform hysterectomy for transmasculine men, and this procedure is sometimes safely and effectively performed in combination with masculinizing chest surgery (mastectomy) performed by our plastic surgeons. Vaginoplasty surgery (feminizing genital surgery) also is performed by urogynecology specialists at our center, and it is sometimes done concurrently at the time of breast augmentation and/or facial feminization surgery.

Case order. Some plastic surgeons vocalize concerns about combining clean procedures with clean contaminated cases, especially in situations in which implants are being placed in the body. During these cases, communication and organization between surgeons is important. For instance, there should be a discussion about case order. In general, the clean procedures should be performed first. In addition, separate operating tables and instruments should be used. Simultaneous operating also should be avoided. Fresh incisions should be dressed and covered before subsequent procedures are performed.

Incision placement. Last, planning around incision placement should be discussed before each case. Laparoscopic and abdominal incisions may interfere with plastic surgery procedures and alter the end cosmesis. These incisions often can be incorporated into the reconstructive procedure. The most important part of the coordinated surgical effort is ensuring that both surgical teams understand each other’s respective surgeries and the approach needed to complete them. When this is achieved, the cases are usually very successful.

Creating collaboration between obstetricians and gynecologic specialists

The impacts of pregnancy and vaginal delivery on the pelvic floor are well established. Urinary and fecal incontinence, pelvic organ prolapse, perineal pain, and dyspareunia are not uncommon in the postpartum period and may persist long term. The effects of obstetric anal sphincter injury (OASI) are significant, with up to 25% of women experiencing wound complications and 17% experiencing fecal incontinence at 6 months postpartum.15,16 Care of women with peripartum pelvic floor disorders and OASIs present an ideal opportunity for collaboration between urogynecologists and obstetricians. The Cleveland Clinic has a multidisciplinary Postpartum Care Clinic (PPCC) where we provide specialized, collaborative care for women with peripartum pelvic floor disorders and complex obstetric lacerations.

Our PPCC accepts referrals up to 1 year postpartum for women who experience OASI, urinary or fecal incontinence, perineal pain or dyspareunia, voiding dysfunction or urinary retention, and wound healing complications. When a woman is diagnosed with an OASI at the time of delivery, a “best practice alert” is released in the medical record recommending a referral to the PPCC to encourage referral of all women with OASI. We strive to see all referrals within 2 weeks of delivery.

At the time of the initial consultation, we collect validated questionnaires on bowel and bladder function, assess pain and healing, and discuss future delivery planning. The success of the PPCC is rooted in communication. When the clinic first opened, we provided education to our obstetrics colleagues on the purpose of the clinic, when and how to refer, and what to expect from our consultations. Open communication between referring obstetric clinicians and the urogynecologists that run the PPCC is key in providing collaborative care where patients know that their clinicians are working as a team. All recommendations are communicated to referring clinicians, and all women are ultimately referred back to their primary clinician for long-term care. Evidence demonstrates that this type of clinic leads to high obstetric clinician satisfaction and increased awareness of OASIs and their impact on maternal health.17

Combined team approach fosters innovation in patient care

A combined approach to the care of the patient who presents with gynecologic conditions is optimal. In this article, we presented examples of care that integrates gynecology, urogynecology, gynecologic oncology, colorectal surgery, plastic surgery, and obstetrics. There are, however, many more existing examples as well as opportunities to create teams that really make a difference in the way patients receive—and perceive—their care. This is a good starting point, and we should strive to use this model to continue to innovate our approach to patient care.

- Ramaseshan AS, Felton J, Roque D, et al. Pelvic floor disorders in women with gynecologic malignancies: a systematic review. Int Urogynecol J. 2018;29:459-476.

- Nakayama N, Tsuji T, Aoyama M, et al. Quality of life and the prevalence of urinary incontinence after surgical treatment for gynecologic cancer: a questionnaire survey. BMC Womens Health. 2020;20:148-157.

- Cascales-Campos PA, Gonzalez-Gil A, Fernandez-Luna E, et al. Urinary and fecal incontinence in patients with advanced ovarian cancer treated with CRS + HIPEC. Surg Oncol. 2021;36:115-119.

- Davidson ER, Woodburn K, AlHilli M, et al. Perioperative adverse events in women undergoing concurrent urogynecologic and gynecologic oncology surgeries for suspected malignancy. Int Urogynecol J. 2019;30:1195-1201.

- Spence-Jones C, Kamm MA, Henry MM, et al. Bowel dysfunction: a pathogenic factor in uterovaginal prolapse and stress urinary incontinence. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1994;101:147-152.

- Thompson JR, Chen AH, Pettit PD, et al. Incidence of occult rectal prolapse in patients with clinical rectoceles and defecatory dysfunction. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;187:1494-1500.

- Jallad K, Gurland B. Multidisciplinary approach to the treatment of concomitant rectal and vaginal prolapse. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2016;29:101-105.

- Kapoor DS, Sultan AH, Thakar R, et al. Management of complex pelvic floor disorders in a multidisciplinary pelvic floor clinic. Colorectal Dis. 2008;10:118-123.

- Weinberg D, Qeadan F, McKee R, et al. Safety of laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy with concurrent rectopexy: peri-operative morbidity in a nationwide cohort. Int Urogynecol J. 2019;30:385-392.

- Geltzeiler CB, Birnbaum EH, Silviera ML, et al. Combined rectopexy and sacrocolpopexy is safe for correction of pelvic organ prolapse. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2018;33:1453-1459.

- Wallace SL, Syan R, Enemchukwu EA, et al. Surgical approach, complications, and reoperation rates of combined rectal and pelvic organ prolapse surgery. Int Urogynecol J. 2020;31:2101-2108.

- Smith PE, Hade EM, Pandya LK, et al. Perioperative outcomes for combined ventral rectopexy with sacrocolpopexy compared to perineal rectopexy with vaginal apical suspension. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2020;26:376-381.

- Casas-Puig V, Bretschneider CE, Ferrando CA. Perioperative adverse events in women undergoing concurrent hemorrhoidectomy at the time of urogynecologic surgery. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2019;25:88-92.

- Cordeiro PG, Pusic AL, Disa JJ. A classification system and reconstructive algorithm for acquired vaginal defects. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2002;110:1058-1065.

- Lewicky-Gaupp C, Leader-Cramer A, Johnson LL, et al. Wound complications after obstetric anal sphincter injuries. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125:1088-1093.

- Borello-France D, Burgio KL, Richter HE, et al; Pelvic Floor Disorders Network. Fecal and urinary incontinence in primiparous women. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108:863-872.

- Propst K, Hickman LC. Peripartum pelvic floor disorder clinics inform obstetric provider practices. Int Urogynecol J. 2021;32:1793-1799.

In her book The Silo Effect: The Peril of Expertise and the Promise of Breaking Down Barriers, Gillian Tett wrote that “the word ‘silo’ does not just refer to a physical structure or organization (such as a department). It can also be a state of mind. Silos exist in structures. But they exist in our minds and social groups too. Silos breed tribalism. But they can also go hand in hand with tunnel vision.”

Tertiary care referral centers seem to be trending toward being more and more “un-siloed” and collaborative within their own departments and between departments in order to care for patients. The terms multidisciplinary and intradisciplinary have become popular in medicine, and teams are joining forces to create care paths for patients that are intended to improve the efficiency of and the quality of care that is rendered. There is no better example of the move to improve collaboration in medicine than the theme of the 2021 Society of Gynecologic Surgeons annual meeting, “Working Together: How Collaboration Enables Us to Better Help Our Patients.”

In this article, we provide examples of how collaborating with other specialties—within and outside of an ObGyn department—should become the standard of care. We discuss how to make this team approach easier and provide evidence that patients experience favorable outcomes. While data on combined care remain sparse, the existing literature on this topic helps us to guide and counsel patients about what to expect when a combined approach is taken.

Addressing pelvic floor disorders in women with gynecologic malignancy

In 2018, authors of a systematic review that looked at concurrent pelvic floor disorders in gynecologic oncologic survivors found that the prevalence of these disorders was high enough to warrant evaluation and management of these conditions to help improve quality of life for patients.1 Furthermore, it is possible that the prevalence of urinary incontinence is higher in patients who have undergone surgery for a gynecologic malignancy compared with controls, which has been reported in previous studies.2,3 At Cleveland Clinic, we recognize the need to evaluate our patients receiving oncologic care for urinary, fecal, and pelvic organ prolapse symptoms. Our oncologists routinely inquire about these symptoms once their patients have undergone surgery with them, and they make referrals for all their symptomatic patients. They have even learned about our own counseling, and they pre-emptively let patients know what our counseling may encompass.

For instance, many patients who received radiation therapy have stress urinary incontinence that is likely related to a hypomobile urethra, and they may benefit more from transurethral bulking than an anti-incontinence procedure in the operating room. Reassuring patients ahead of time that they do not need major interventions for their symptoms is helpful, as these patients are already experiencing tremendous burden from their oncologic conditions. We have made our referral patterns easy for these patients, and most patients are seen within days to weeks of the referral placed, depending on the urgency of the consult and the need to proceed with their oncologic treatment plan.

Gynecologic oncology patients who present with preoperative stress urinary incontinence and pelvic organ prolapse also are referred to a urogynecology specialist for concurrent care. Care paths have been created to help inform both the urogynecologists and the oncologists about options for patients depending on their respective conditions, as both their malignancy and their pelvic floor disorder(s) are considered in treatment planning. There is agreement in this planning that the oncologic surgery takes priority, and the urogynecologic approach is based on the oncologic plan.

Our urogynecologists routinely ask if future radiation is in the treatment plan, as this usually precludes us from placing a midurethral sling at the time of any surgery. Surgical approach (vaginal versus abdominal; open or minimally invasive) also is determined by the oncologic team. At the time of surgery, patient positioning is considered to optimize access for all of the surgeons. For instance, having the oncologist know that the patient needs to be far down on the bed as their steep Trendelenburg positioning during laparoscopy or robotic surgery may cause the patient to slide cephalad during the case may make a vaginal repair or sling placement at the end of the case challenging. All these small nuances are important, and a collaborative team develops the right plan for each patient in advance.

Data on the outcomes of combined surgery are sparse. In a retrospective matched cohort study, our group compared outcomes in women who underwent concurrent surgery with those who underwent urogynecologic surgery alone.4 We found that concurrent surgeries had an increased incidence of minor but not serious perioperative adverse events. Importantly, we determined that 1 in 10 planned urogynecologic procedures needed to be either modified or abandoned as a result of the oncologic plan. These data help guide our counseling, and both the oncologist and urogynecologist contributing to the combined case counsel patients according to these data.

Continue to: Concurrent colorectal and gynecologic surgery...

Concurrent colorectal and gynecologic surgery

Many women have pelvic floor disorders. As gynecologists, we often compartmentalize these conditions as gynecologic problems; frequently, however, colorectal conditions are at play as well and should be addressed concurrently. For instance, a high incidence of anorectal dysfunction occurs in women who present with pelvic organ prolapse.5 Furthermore, outlet defecation disorders are not always a result of a straightforward rectocele that can be fixed vaginally. Sometimes, a more thorough evaluation is warranted depending on the patient’s concurrent symptoms and history. Outlet symptoms may be attributed to large enteroceles, sigmoidoceles, perineal descent, rectal intussusception, and rectal prolapse.6

As a result, a combined approach to caring for patients with complex pelvic floor disorders is optimal. Several studies describe this type of combined and coordinated patient care.7,8 Ideally, patients are seen by both surgeons in the office so that the surgeons may make a combined plan for their care, especially if the decision is made to proceed with surgery. Urogynecology specialists and colorectal surgeons must decide together whether to approach combined prolapse procedures via a perineal and vaginal approach versus an abdominal approach. Several factors can determine this, including surgeon experience and preference, which is why it is important for surgeons working together to have either well-designed care paths or simply open communication and experience working together for the conditions they are treating.

In an ideal coordinated care approach, both surgeons review the patient records in advance. Any needed imaging or testing is done before the official patient consult; the patient is then seen by both clinicians in the same visit and counseled about the options. This is the most efficient and effective way to see patients, and we have had significant success using this approach.

Complications of combined surgery

The safety of combining procedures such as laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy and concurrent rectopexy has been studied, and intraoperative complications have been reported to be low.9,10 In a cohort study, Wallace and colleagues looked at postoperative outcomes and complications following combined surgery and reported that reoperation for the rectal prolapse component of the surgery was more common than the pelvic organ prolapse component, and that 1 in 5 of their patients experienced a surgical complication within 30 days of their surgery.11 This incidence is higher than that seen with isolated pelvic organ prolapse surgery. These data help us understand that a combined approach requires good patient counseling in the office about both the need for repeat surgery in certain circumstances and the increased risk of complications. Further, combined perineal and vaginal approaches have been compared with abdominal approaches and also have shown no age-adjusted differences in outcomes and complications.12

These data point to the need for surgeons to choose the approach to surgery that best fits their own experiences and to discuss this together before counseling the patient in the office, thus streamlining the effort so that the patient feels comfortable under the care of 2 surgeons.

Patients presenting with urogynecologic and gynecologic conditions also report symptomatic hemorrhoids, and colorectal referral is often made by the gynecologist. Sparse data are available regarding combined approaches to managing hemorrhoids and gynecologic conditions. Our group was the first to publish on outcomes and complications in patients undergoing concurrent hemorrhoidectomy at the time of urogynecologic surgery.13 In that retrospective cohort, we found that minor complications, such as postoperative urinary tract infection and transient voiding dysfunction, was more common in patients who underwent combined surgery. From this, we gathered that there is a need to counsel patients appropriately about the risk of combined surgery. That said, for some patients, coordinated care is desirable, and surgeons should make the effort to work together in combining their procedures.

Continue to: Integrating plastic and reconstructive surgery in gynecology...

Integrating plastic and reconstructive surgery in gynecology

Reconstructive gynecologic procedures often require a multidisciplinary approach to what can be very complex reconstructive surgery. The intended goal usually is to achieve a good cosmetic result in the genital area, as well as to restore sexual, defecatory, and/or genitourinary functionality. As a result, surgeons must work together to develop a feasible reconstructive plan for these patients.

Women experience vaginal stenosis or foreshortening for a number of reasons. Women with congenital anomalies often are cared for by specialists in pediatric and adolescent gynecology. Other women, such as those who have undergone vaginectomy and/or pelvic or vaginal radiation for cancer treatment, complications from vaginal mesh placement, and severe vaginal scarring from dermatologic conditions like lichen planus, are cared for by other gynecologic specialists, often general gynecologists or urogynecologists. In some of these cases, a gynecologic surgeon can perform vaginal adhesiolysis followed by vaginal estrogen treatment (when appropriate) and aggressive postoperative vaginal dilation with adjunctive pelvic floor physical therapy as well as sex therapy or counseling. A simple reconstructive approach may be necessary if lysis of adhesions alone is not sufficient. Sometimes, the vaginal apex must be opened vaginally or abdominally, or releasing incisions need to be made to improve the caliber of the vagina in addition to its length. Under these circumstances, the use of additional local skin grafts, local peritoneal flaps, or biologic grafts or xenografts can help achieve a satisfying result. While not all gynecologists are trained to perform these procedures, some are, and certainly gynecologic subspecialists have the skill sets to care for these patients.

Under other circumstances, when the vagina is truly foreshortened, more aggressive reconstructive surgery is necessary and consultation and collaboration with plastic surgery specialists often is helpful. At our center, these patients’ care is initially managed by gynecologists and, when simple approaches to their reconstructive needs are exhausted, collaboration is warranted. As with the other team approaches discussed in this article, the recommendation is for a consistent referral team that has established care paths for patients. Not all plastic surgeons are familiar with neovaginal reconstruction and understand the functional aspects that gynecologists are hoping to achieve for their patients. Therefore, it is important to form cohesive teams that have the same goals for the patient.

The literature on neovaginal reconstruction is sparse. There are no true agreed on approaches or techniques for vaginal reconstruction because there is no “one size fits all” for these repairs. Defects also vary depending on whether they are due to resections or radiation for oncologic treatment, reconstruction as part of the repair of a genitourinary or rectovaginal fistula, or stenosis from other etiologies.

In 2002, Cordeiro and colleagues published a classification system and reconstructive algorithm for acquired vaginal defects.14 Not all reconstructive surgeons subscribe to this algorithm, but it is the only rubric that currently exists. The authors differentiate between “partial” and “circumferential” defects and recommend different types of fasciocutaneous and myocutaneous flaps for reconstruction.

In our experience at our center, we believe that the choice of flap should also depend on whether or not perineal reconstruction is needed. This decision is made by both the gynecologic specialist and the plastic surgeon. Common flap choices include the Singapore flap, a fasciocutaneous flap based on perforators from the pudendal vessels; the gracilis flap, a myocutaneous flap based off the medial circumflex femoral vessels; and the rectus abdominis flap (transverse or vertical), which is also a myocutaneous flap that relies on the blood supply from the deep inferior epigastric vessels.

One of the most important parts of the coordinated effort of neovaginal surgery is postoperative care. Plastic surgeons play a key role in ensuring that the flap survives in the immediate postoperative period. The gynecology team should be responsible for postoperative vaginal dilation teaching and follow-up to ensure that the patient dilates properly and upsizes her dilator appropriately over the postoperative period. In our practice, our advanced practice clinicians often care for these patients and are responsible for continuity and dilation teaching. Patients have easy access to these clinicians, and this enhances the postoperative experience. Referral to a pelvic floor physical therapist knowledgeable about neovaginal surgery also helps to ensure that the dilation process goes successfully. It also helps to have office days on the same days as the plastic surgery team that is following the patient. This way, the patient may be seen by both teams on the same day. This allows for good patient communication with regard to aftercare, as well as a combined approach to teaching the trainees involved in the case. Coordination with pelvic floor physical therapists on those days also enhances the patient experience and is highly recommended.

Continue to: Combining gyn and urogyn procedures with plastic surgery...

Combining gyn and urogyn procedures with plastic surgery

While there are no data on combining gynecologic and urogynecologic procedures with plastic reconstructive surgeries, a team approach to combining surgeries is possible. At our center, we have performed tubal ligation, ovarian surgery, hysterectomy, and sling and prolapse surgery in patients who were undergoing cosmetic procedures, such as breast augmentation and abdominoplasty.

Gender affirmation surgery also can be performed through a combined approach between gynecologists and plastic surgeons. Our gynecologists perform hysterectomy for transmasculine men, and this procedure is sometimes safely and effectively performed in combination with masculinizing chest surgery (mastectomy) performed by our plastic surgeons. Vaginoplasty surgery (feminizing genital surgery) also is performed by urogynecology specialists at our center, and it is sometimes done concurrently at the time of breast augmentation and/or facial feminization surgery.

Case order. Some plastic surgeons vocalize concerns about combining clean procedures with clean contaminated cases, especially in situations in which implants are being placed in the body. During these cases, communication and organization between surgeons is important. For instance, there should be a discussion about case order. In general, the clean procedures should be performed first. In addition, separate operating tables and instruments should be used. Simultaneous operating also should be avoided. Fresh incisions should be dressed and covered before subsequent procedures are performed.

Incision placement. Last, planning around incision placement should be discussed before each case. Laparoscopic and abdominal incisions may interfere with plastic surgery procedures and alter the end cosmesis. These incisions often can be incorporated into the reconstructive procedure. The most important part of the coordinated surgical effort is ensuring that both surgical teams understand each other’s respective surgeries and the approach needed to complete them. When this is achieved, the cases are usually very successful.

Creating collaboration between obstetricians and gynecologic specialists

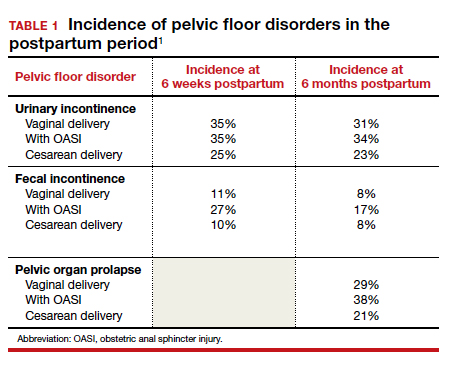

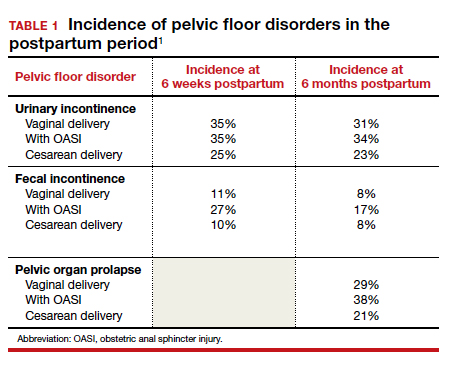

The impacts of pregnancy and vaginal delivery on the pelvic floor are well established. Urinary and fecal incontinence, pelvic organ prolapse, perineal pain, and dyspareunia are not uncommon in the postpartum period and may persist long term. The effects of obstetric anal sphincter injury (OASI) are significant, with up to 25% of women experiencing wound complications and 17% experiencing fecal incontinence at 6 months postpartum.15,16 Care of women with peripartum pelvic floor disorders and OASIs present an ideal opportunity for collaboration between urogynecologists and obstetricians. The Cleveland Clinic has a multidisciplinary Postpartum Care Clinic (PPCC) where we provide specialized, collaborative care for women with peripartum pelvic floor disorders and complex obstetric lacerations.

Our PPCC accepts referrals up to 1 year postpartum for women who experience OASI, urinary or fecal incontinence, perineal pain or dyspareunia, voiding dysfunction or urinary retention, and wound healing complications. When a woman is diagnosed with an OASI at the time of delivery, a “best practice alert” is released in the medical record recommending a referral to the PPCC to encourage referral of all women with OASI. We strive to see all referrals within 2 weeks of delivery.

At the time of the initial consultation, we collect validated questionnaires on bowel and bladder function, assess pain and healing, and discuss future delivery planning. The success of the PPCC is rooted in communication. When the clinic first opened, we provided education to our obstetrics colleagues on the purpose of the clinic, when and how to refer, and what to expect from our consultations. Open communication between referring obstetric clinicians and the urogynecologists that run the PPCC is key in providing collaborative care where patients know that their clinicians are working as a team. All recommendations are communicated to referring clinicians, and all women are ultimately referred back to their primary clinician for long-term care. Evidence demonstrates that this type of clinic leads to high obstetric clinician satisfaction and increased awareness of OASIs and their impact on maternal health.17

Combined team approach fosters innovation in patient care

A combined approach to the care of the patient who presents with gynecologic conditions is optimal. In this article, we presented examples of care that integrates gynecology, urogynecology, gynecologic oncology, colorectal surgery, plastic surgery, and obstetrics. There are, however, many more existing examples as well as opportunities to create teams that really make a difference in the way patients receive—and perceive—their care. This is a good starting point, and we should strive to use this model to continue to innovate our approach to patient care.

In her book The Silo Effect: The Peril of Expertise and the Promise of Breaking Down Barriers, Gillian Tett wrote that “the word ‘silo’ does not just refer to a physical structure or organization (such as a department). It can also be a state of mind. Silos exist in structures. But they exist in our minds and social groups too. Silos breed tribalism. But they can also go hand in hand with tunnel vision.”

Tertiary care referral centers seem to be trending toward being more and more “un-siloed” and collaborative within their own departments and between departments in order to care for patients. The terms multidisciplinary and intradisciplinary have become popular in medicine, and teams are joining forces to create care paths for patients that are intended to improve the efficiency of and the quality of care that is rendered. There is no better example of the move to improve collaboration in medicine than the theme of the 2021 Society of Gynecologic Surgeons annual meeting, “Working Together: How Collaboration Enables Us to Better Help Our Patients.”

In this article, we provide examples of how collaborating with other specialties—within and outside of an ObGyn department—should become the standard of care. We discuss how to make this team approach easier and provide evidence that patients experience favorable outcomes. While data on combined care remain sparse, the existing literature on this topic helps us to guide and counsel patients about what to expect when a combined approach is taken.

Addressing pelvic floor disorders in women with gynecologic malignancy

In 2018, authors of a systematic review that looked at concurrent pelvic floor disorders in gynecologic oncologic survivors found that the prevalence of these disorders was high enough to warrant evaluation and management of these conditions to help improve quality of life for patients.1 Furthermore, it is possible that the prevalence of urinary incontinence is higher in patients who have undergone surgery for a gynecologic malignancy compared with controls, which has been reported in previous studies.2,3 At Cleveland Clinic, we recognize the need to evaluate our patients receiving oncologic care for urinary, fecal, and pelvic organ prolapse symptoms. Our oncologists routinely inquire about these symptoms once their patients have undergone surgery with them, and they make referrals for all their symptomatic patients. They have even learned about our own counseling, and they pre-emptively let patients know what our counseling may encompass.

For instance, many patients who received radiation therapy have stress urinary incontinence that is likely related to a hypomobile urethra, and they may benefit more from transurethral bulking than an anti-incontinence procedure in the operating room. Reassuring patients ahead of time that they do not need major interventions for their symptoms is helpful, as these patients are already experiencing tremendous burden from their oncologic conditions. We have made our referral patterns easy for these patients, and most patients are seen within days to weeks of the referral placed, depending on the urgency of the consult and the need to proceed with their oncologic treatment plan.

Gynecologic oncology patients who present with preoperative stress urinary incontinence and pelvic organ prolapse also are referred to a urogynecology specialist for concurrent care. Care paths have been created to help inform both the urogynecologists and the oncologists about options for patients depending on their respective conditions, as both their malignancy and their pelvic floor disorder(s) are considered in treatment planning. There is agreement in this planning that the oncologic surgery takes priority, and the urogynecologic approach is based on the oncologic plan.

Our urogynecologists routinely ask if future radiation is in the treatment plan, as this usually precludes us from placing a midurethral sling at the time of any surgery. Surgical approach (vaginal versus abdominal; open or minimally invasive) also is determined by the oncologic team. At the time of surgery, patient positioning is considered to optimize access for all of the surgeons. For instance, having the oncologist know that the patient needs to be far down on the bed as their steep Trendelenburg positioning during laparoscopy or robotic surgery may cause the patient to slide cephalad during the case may make a vaginal repair or sling placement at the end of the case challenging. All these small nuances are important, and a collaborative team develops the right plan for each patient in advance.

Data on the outcomes of combined surgery are sparse. In a retrospective matched cohort study, our group compared outcomes in women who underwent concurrent surgery with those who underwent urogynecologic surgery alone.4 We found that concurrent surgeries had an increased incidence of minor but not serious perioperative adverse events. Importantly, we determined that 1 in 10 planned urogynecologic procedures needed to be either modified or abandoned as a result of the oncologic plan. These data help guide our counseling, and both the oncologist and urogynecologist contributing to the combined case counsel patients according to these data.

Continue to: Concurrent colorectal and gynecologic surgery...

Concurrent colorectal and gynecologic surgery

Many women have pelvic floor disorders. As gynecologists, we often compartmentalize these conditions as gynecologic problems; frequently, however, colorectal conditions are at play as well and should be addressed concurrently. For instance, a high incidence of anorectal dysfunction occurs in women who present with pelvic organ prolapse.5 Furthermore, outlet defecation disorders are not always a result of a straightforward rectocele that can be fixed vaginally. Sometimes, a more thorough evaluation is warranted depending on the patient’s concurrent symptoms and history. Outlet symptoms may be attributed to large enteroceles, sigmoidoceles, perineal descent, rectal intussusception, and rectal prolapse.6

As a result, a combined approach to caring for patients with complex pelvic floor disorders is optimal. Several studies describe this type of combined and coordinated patient care.7,8 Ideally, patients are seen by both surgeons in the office so that the surgeons may make a combined plan for their care, especially if the decision is made to proceed with surgery. Urogynecology specialists and colorectal surgeons must decide together whether to approach combined prolapse procedures via a perineal and vaginal approach versus an abdominal approach. Several factors can determine this, including surgeon experience and preference, which is why it is important for surgeons working together to have either well-designed care paths or simply open communication and experience working together for the conditions they are treating.

In an ideal coordinated care approach, both surgeons review the patient records in advance. Any needed imaging or testing is done before the official patient consult; the patient is then seen by both clinicians in the same visit and counseled about the options. This is the most efficient and effective way to see patients, and we have had significant success using this approach.

Complications of combined surgery

The safety of combining procedures such as laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy and concurrent rectopexy has been studied, and intraoperative complications have been reported to be low.9,10 In a cohort study, Wallace and colleagues looked at postoperative outcomes and complications following combined surgery and reported that reoperation for the rectal prolapse component of the surgery was more common than the pelvic organ prolapse component, and that 1 in 5 of their patients experienced a surgical complication within 30 days of their surgery.11 This incidence is higher than that seen with isolated pelvic organ prolapse surgery. These data help us understand that a combined approach requires good patient counseling in the office about both the need for repeat surgery in certain circumstances and the increased risk of complications. Further, combined perineal and vaginal approaches have been compared with abdominal approaches and also have shown no age-adjusted differences in outcomes and complications.12

These data point to the need for surgeons to choose the approach to surgery that best fits their own experiences and to discuss this together before counseling the patient in the office, thus streamlining the effort so that the patient feels comfortable under the care of 2 surgeons.

Patients presenting with urogynecologic and gynecologic conditions also report symptomatic hemorrhoids, and colorectal referral is often made by the gynecologist. Sparse data are available regarding combined approaches to managing hemorrhoids and gynecologic conditions. Our group was the first to publish on outcomes and complications in patients undergoing concurrent hemorrhoidectomy at the time of urogynecologic surgery.13 In that retrospective cohort, we found that minor complications, such as postoperative urinary tract infection and transient voiding dysfunction, was more common in patients who underwent combined surgery. From this, we gathered that there is a need to counsel patients appropriately about the risk of combined surgery. That said, for some patients, coordinated care is desirable, and surgeons should make the effort to work together in combining their procedures.

Continue to: Integrating plastic and reconstructive surgery in gynecology...

Integrating plastic and reconstructive surgery in gynecology

Reconstructive gynecologic procedures often require a multidisciplinary approach to what can be very complex reconstructive surgery. The intended goal usually is to achieve a good cosmetic result in the genital area, as well as to restore sexual, defecatory, and/or genitourinary functionality. As a result, surgeons must work together to develop a feasible reconstructive plan for these patients.

Women experience vaginal stenosis or foreshortening for a number of reasons. Women with congenital anomalies often are cared for by specialists in pediatric and adolescent gynecology. Other women, such as those who have undergone vaginectomy and/or pelvic or vaginal radiation for cancer treatment, complications from vaginal mesh placement, and severe vaginal scarring from dermatologic conditions like lichen planus, are cared for by other gynecologic specialists, often general gynecologists or urogynecologists. In some of these cases, a gynecologic surgeon can perform vaginal adhesiolysis followed by vaginal estrogen treatment (when appropriate) and aggressive postoperative vaginal dilation with adjunctive pelvic floor physical therapy as well as sex therapy or counseling. A simple reconstructive approach may be necessary if lysis of adhesions alone is not sufficient. Sometimes, the vaginal apex must be opened vaginally or abdominally, or releasing incisions need to be made to improve the caliber of the vagina in addition to its length. Under these circumstances, the use of additional local skin grafts, local peritoneal flaps, or biologic grafts or xenografts can help achieve a satisfying result. While not all gynecologists are trained to perform these procedures, some are, and certainly gynecologic subspecialists have the skill sets to care for these patients.

Under other circumstances, when the vagina is truly foreshortened, more aggressive reconstructive surgery is necessary and consultation and collaboration with plastic surgery specialists often is helpful. At our center, these patients’ care is initially managed by gynecologists and, when simple approaches to their reconstructive needs are exhausted, collaboration is warranted. As with the other team approaches discussed in this article, the recommendation is for a consistent referral team that has established care paths for patients. Not all plastic surgeons are familiar with neovaginal reconstruction and understand the functional aspects that gynecologists are hoping to achieve for their patients. Therefore, it is important to form cohesive teams that have the same goals for the patient.

The literature on neovaginal reconstruction is sparse. There are no true agreed on approaches or techniques for vaginal reconstruction because there is no “one size fits all” for these repairs. Defects also vary depending on whether they are due to resections or radiation for oncologic treatment, reconstruction as part of the repair of a genitourinary or rectovaginal fistula, or stenosis from other etiologies.

In 2002, Cordeiro and colleagues published a classification system and reconstructive algorithm for acquired vaginal defects.14 Not all reconstructive surgeons subscribe to this algorithm, but it is the only rubric that currently exists. The authors differentiate between “partial” and “circumferential” defects and recommend different types of fasciocutaneous and myocutaneous flaps for reconstruction.

In our experience at our center, we believe that the choice of flap should also depend on whether or not perineal reconstruction is needed. This decision is made by both the gynecologic specialist and the plastic surgeon. Common flap choices include the Singapore flap, a fasciocutaneous flap based on perforators from the pudendal vessels; the gracilis flap, a myocutaneous flap based off the medial circumflex femoral vessels; and the rectus abdominis flap (transverse or vertical), which is also a myocutaneous flap that relies on the blood supply from the deep inferior epigastric vessels.

One of the most important parts of the coordinated effort of neovaginal surgery is postoperative care. Plastic surgeons play a key role in ensuring that the flap survives in the immediate postoperative period. The gynecology team should be responsible for postoperative vaginal dilation teaching and follow-up to ensure that the patient dilates properly and upsizes her dilator appropriately over the postoperative period. In our practice, our advanced practice clinicians often care for these patients and are responsible for continuity and dilation teaching. Patients have easy access to these clinicians, and this enhances the postoperative experience. Referral to a pelvic floor physical therapist knowledgeable about neovaginal surgery also helps to ensure that the dilation process goes successfully. It also helps to have office days on the same days as the plastic surgery team that is following the patient. This way, the patient may be seen by both teams on the same day. This allows for good patient communication with regard to aftercare, as well as a combined approach to teaching the trainees involved in the case. Coordination with pelvic floor physical therapists on those days also enhances the patient experience and is highly recommended.

Continue to: Combining gyn and urogyn procedures with plastic surgery...

Combining gyn and urogyn procedures with plastic surgery

While there are no data on combining gynecologic and urogynecologic procedures with plastic reconstructive surgeries, a team approach to combining surgeries is possible. At our center, we have performed tubal ligation, ovarian surgery, hysterectomy, and sling and prolapse surgery in patients who were undergoing cosmetic procedures, such as breast augmentation and abdominoplasty.

Gender affirmation surgery also can be performed through a combined approach between gynecologists and plastic surgeons. Our gynecologists perform hysterectomy for transmasculine men, and this procedure is sometimes safely and effectively performed in combination with masculinizing chest surgery (mastectomy) performed by our plastic surgeons. Vaginoplasty surgery (feminizing genital surgery) also is performed by urogynecology specialists at our center, and it is sometimes done concurrently at the time of breast augmentation and/or facial feminization surgery.

Case order. Some plastic surgeons vocalize concerns about combining clean procedures with clean contaminated cases, especially in situations in which implants are being placed in the body. During these cases, communication and organization between surgeons is important. For instance, there should be a discussion about case order. In general, the clean procedures should be performed first. In addition, separate operating tables and instruments should be used. Simultaneous operating also should be avoided. Fresh incisions should be dressed and covered before subsequent procedures are performed.

Incision placement. Last, planning around incision placement should be discussed before each case. Laparoscopic and abdominal incisions may interfere with plastic surgery procedures and alter the end cosmesis. These incisions often can be incorporated into the reconstructive procedure. The most important part of the coordinated surgical effort is ensuring that both surgical teams understand each other’s respective surgeries and the approach needed to complete them. When this is achieved, the cases are usually very successful.

Creating collaboration between obstetricians and gynecologic specialists

The impacts of pregnancy and vaginal delivery on the pelvic floor are well established. Urinary and fecal incontinence, pelvic organ prolapse, perineal pain, and dyspareunia are not uncommon in the postpartum period and may persist long term. The effects of obstetric anal sphincter injury (OASI) are significant, with up to 25% of women experiencing wound complications and 17% experiencing fecal incontinence at 6 months postpartum.15,16 Care of women with peripartum pelvic floor disorders and OASIs present an ideal opportunity for collaboration between urogynecologists and obstetricians. The Cleveland Clinic has a multidisciplinary Postpartum Care Clinic (PPCC) where we provide specialized, collaborative care for women with peripartum pelvic floor disorders and complex obstetric lacerations.

Our PPCC accepts referrals up to 1 year postpartum for women who experience OASI, urinary or fecal incontinence, perineal pain or dyspareunia, voiding dysfunction or urinary retention, and wound healing complications. When a woman is diagnosed with an OASI at the time of delivery, a “best practice alert” is released in the medical record recommending a referral to the PPCC to encourage referral of all women with OASI. We strive to see all referrals within 2 weeks of delivery.

At the time of the initial consultation, we collect validated questionnaires on bowel and bladder function, assess pain and healing, and discuss future delivery planning. The success of the PPCC is rooted in communication. When the clinic first opened, we provided education to our obstetrics colleagues on the purpose of the clinic, when and how to refer, and what to expect from our consultations. Open communication between referring obstetric clinicians and the urogynecologists that run the PPCC is key in providing collaborative care where patients know that their clinicians are working as a team. All recommendations are communicated to referring clinicians, and all women are ultimately referred back to their primary clinician for long-term care. Evidence demonstrates that this type of clinic leads to high obstetric clinician satisfaction and increased awareness of OASIs and their impact on maternal health.17

Combined team approach fosters innovation in patient care

A combined approach to the care of the patient who presents with gynecologic conditions is optimal. In this article, we presented examples of care that integrates gynecology, urogynecology, gynecologic oncology, colorectal surgery, plastic surgery, and obstetrics. There are, however, many more existing examples as well as opportunities to create teams that really make a difference in the way patients receive—and perceive—their care. This is a good starting point, and we should strive to use this model to continue to innovate our approach to patient care.

- Ramaseshan AS, Felton J, Roque D, et al. Pelvic floor disorders in women with gynecologic malignancies: a systematic review. Int Urogynecol J. 2018;29:459-476.

- Nakayama N, Tsuji T, Aoyama M, et al. Quality of life and the prevalence of urinary incontinence after surgical treatment for gynecologic cancer: a questionnaire survey. BMC Womens Health. 2020;20:148-157.

- Cascales-Campos PA, Gonzalez-Gil A, Fernandez-Luna E, et al. Urinary and fecal incontinence in patients with advanced ovarian cancer treated with CRS + HIPEC. Surg Oncol. 2021;36:115-119.

- Davidson ER, Woodburn K, AlHilli M, et al. Perioperative adverse events in women undergoing concurrent urogynecologic and gynecologic oncology surgeries for suspected malignancy. Int Urogynecol J. 2019;30:1195-1201.

- Spence-Jones C, Kamm MA, Henry MM, et al. Bowel dysfunction: a pathogenic factor in uterovaginal prolapse and stress urinary incontinence. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1994;101:147-152.

- Thompson JR, Chen AH, Pettit PD, et al. Incidence of occult rectal prolapse in patients with clinical rectoceles and defecatory dysfunction. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;187:1494-1500.

- Jallad K, Gurland B. Multidisciplinary approach to the treatment of concomitant rectal and vaginal prolapse. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2016;29:101-105.

- Kapoor DS, Sultan AH, Thakar R, et al. Management of complex pelvic floor disorders in a multidisciplinary pelvic floor clinic. Colorectal Dis. 2008;10:118-123.

- Weinberg D, Qeadan F, McKee R, et al. Safety of laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy with concurrent rectopexy: peri-operative morbidity in a nationwide cohort. Int Urogynecol J. 2019;30:385-392.

- Geltzeiler CB, Birnbaum EH, Silviera ML, et al. Combined rectopexy and sacrocolpopexy is safe for correction of pelvic organ prolapse. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2018;33:1453-1459.

- Wallace SL, Syan R, Enemchukwu EA, et al. Surgical approach, complications, and reoperation rates of combined rectal and pelvic organ prolapse surgery. Int Urogynecol J. 2020;31:2101-2108.

- Smith PE, Hade EM, Pandya LK, et al. Perioperative outcomes for combined ventral rectopexy with sacrocolpopexy compared to perineal rectopexy with vaginal apical suspension. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2020;26:376-381.

- Casas-Puig V, Bretschneider CE, Ferrando CA. Perioperative adverse events in women undergoing concurrent hemorrhoidectomy at the time of urogynecologic surgery. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2019;25:88-92.

- Cordeiro PG, Pusic AL, Disa JJ. A classification system and reconstructive algorithm for acquired vaginal defects. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2002;110:1058-1065.

- Lewicky-Gaupp C, Leader-Cramer A, Johnson LL, et al. Wound complications after obstetric anal sphincter injuries. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125:1088-1093.

- Borello-France D, Burgio KL, Richter HE, et al; Pelvic Floor Disorders Network. Fecal and urinary incontinence in primiparous women. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108:863-872.

- Propst K, Hickman LC. Peripartum pelvic floor disorder clinics inform obstetric provider practices. Int Urogynecol J. 2021;32:1793-1799.

- Ramaseshan AS, Felton J, Roque D, et al. Pelvic floor disorders in women with gynecologic malignancies: a systematic review. Int Urogynecol J. 2018;29:459-476.

- Nakayama N, Tsuji T, Aoyama M, et al. Quality of life and the prevalence of urinary incontinence after surgical treatment for gynecologic cancer: a questionnaire survey. BMC Womens Health. 2020;20:148-157.

- Cascales-Campos PA, Gonzalez-Gil A, Fernandez-Luna E, et al. Urinary and fecal incontinence in patients with advanced ovarian cancer treated with CRS + HIPEC. Surg Oncol. 2021;36:115-119.

- Davidson ER, Woodburn K, AlHilli M, et al. Perioperative adverse events in women undergoing concurrent urogynecologic and gynecologic oncology surgeries for suspected malignancy. Int Urogynecol J. 2019;30:1195-1201.

- Spence-Jones C, Kamm MA, Henry MM, et al. Bowel dysfunction: a pathogenic factor in uterovaginal prolapse and stress urinary incontinence. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1994;101:147-152.

- Thompson JR, Chen AH, Pettit PD, et al. Incidence of occult rectal prolapse in patients with clinical rectoceles and defecatory dysfunction. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;187:1494-1500.

- Jallad K, Gurland B. Multidisciplinary approach to the treatment of concomitant rectal and vaginal prolapse. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2016;29:101-105.

- Kapoor DS, Sultan AH, Thakar R, et al. Management of complex pelvic floor disorders in a multidisciplinary pelvic floor clinic. Colorectal Dis. 2008;10:118-123.

- Weinberg D, Qeadan F, McKee R, et al. Safety of laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy with concurrent rectopexy: peri-operative morbidity in a nationwide cohort. Int Urogynecol J. 2019;30:385-392.

- Geltzeiler CB, Birnbaum EH, Silviera ML, et al. Combined rectopexy and sacrocolpopexy is safe for correction of pelvic organ prolapse. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2018;33:1453-1459.

- Wallace SL, Syan R, Enemchukwu EA, et al. Surgical approach, complications, and reoperation rates of combined rectal and pelvic organ prolapse surgery. Int Urogynecol J. 2020;31:2101-2108.

- Smith PE, Hade EM, Pandya LK, et al. Perioperative outcomes for combined ventral rectopexy with sacrocolpopexy compared to perineal rectopexy with vaginal apical suspension. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2020;26:376-381.

- Casas-Puig V, Bretschneider CE, Ferrando CA. Perioperative adverse events in women undergoing concurrent hemorrhoidectomy at the time of urogynecologic surgery. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2019;25:88-92.

- Cordeiro PG, Pusic AL, Disa JJ. A classification system and reconstructive algorithm for acquired vaginal defects. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2002;110:1058-1065.

- Lewicky-Gaupp C, Leader-Cramer A, Johnson LL, et al. Wound complications after obstetric anal sphincter injuries. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125:1088-1093.

- Borello-France D, Burgio KL, Richter HE, et al; Pelvic Floor Disorders Network. Fecal and urinary incontinence in primiparous women. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108:863-872.

- Propst K, Hickman LC. Peripartum pelvic floor disorder clinics inform obstetric provider practices. Int Urogynecol J. 2021;32:1793-1799.

Caring for women with pelvic floor disorders during pregnancy and postpartum: Expert guidance

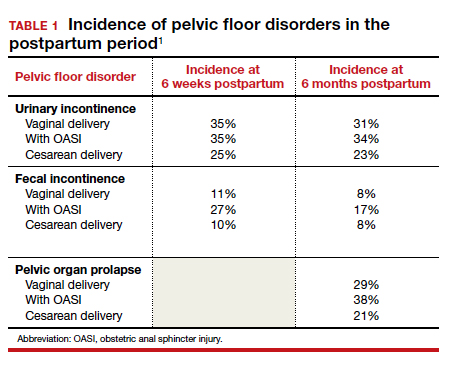

Pelvic floor disorders (PFDs) affect many pregnant and newly postpartum women. These conditions, including urinary incontinence, anal incontinence, and pelvic organ prolapse (POP), can be overshadowed by common pregnancy and postpartum concerns (TABLE 1).1 With the use of a few quick screening questions, however, PFDs easily can be identified in this at-risk population. Active management need not be delayed until after delivery for women experiencing bother, as options exist for women with PFDs during pregnancy as well as postpartum.

In this article, we discuss the common PFDs that obstetric clinicians face in the context of case scenarios and review how you can be better equipped to care for affected individuals.

CASE 1 Screening

A 30-year-old woman (G1P1) presents for her routine postpartum visit after an operative vaginal delivery with a second-degree laceration.

How would you screen this patient for PFDs?

Why screening for PFDs matters

While there are no validated PFD screening tools for this patient population, clinicians can ask a series of brief open-ended questions as part of the review of systems to efficiently evaluate for the common PFDs in peripartum patients (see “Screening questions to evaluate patients for peripartum pelvic floor disorders” below).

Pelvic floor disorders in the peripartum period can have a significant negative impact. In pregnancy, nearly half of women report psychological strain due to the presence of bowel, bladder, prolapse, or sexual dysfunction symptoms.2 Postpartum, PFDs have negative effects on overall health, well-being, and self-esteem, with significantly increased rates of postpartum depression in women who experience urinary incontinence.3,4 Proactively inquiring about PFD symptoms, providing anticipatory guidance, and recommending treatment options can positively impact a patient in multiple domains.

Sometimes during pregnancy or after having a baby, a woman experiences pelvic floor symptoms. Do you have any of the following?

- leakage with coughing, laughing, sneezing, or physical activity

- urgency to urinate or leakage due to urgency

- bulging or pressure within the vagina

- pain with intercourse

- accidental bowel leakage of stool or flatus

CASE 2 Stress urinary incontinence

A 27-year-old woman (G1P1) presents 2 months following spontaneous vaginal delivery with symptoms of urine leakage with laughing and running. Her urinary incontinence has been improving since delivery, but it continues to be bothersome.

What would you recommend for this patient?

Conservative SUI management strategies in pregnancy

Urinary tract symptoms are common in pregnancy, with up to 41.8% of women reporting urinary symptom distress in the third trimester.5 During pregnancy, estrogen and progesterone decrease urethral pressure that, together with increased intra-abdominal pressure from the gravid uterus, can cause or worsen stress urinary incontinence (SUI).6

During pregnancy, women should be offered conservative therapies for SUI. For women who can perform a pelvic floor contraction (a Kegel exercise), self-guided pelvic floor muscle exercises (PFMEs) may be helpful (see “Pelvic floor muscle exercises” below). We recommend that women start with 1 to 2 sets of 10 Kegel exercises per day and that they hold the squeeze for 2 to 3 seconds, working up to holding for 10 seconds. The goal is to strengthen and improve muscle control so that the Kegel squeeze can be paired with activities that cause SUI.

For women who are unable to perform a Kegel exercise or are not improving with a home PFME regimen, referral to pelvic floor physical therapy (PFPT) can be considered. While data support the efficacy of PFPT for SUI treatment in nonpregnant women,7 data are lacking on PFME in pregnancy.

In women without urinary incontinence, PFME in early pregnancy can prevent the onset of incontinence in late pregnancy and the postpartum period.8 By contrast, the same 2020 Cochrane Review found no evidence that antenatal pelvic floor muscle therapy in incontinent women decreases incontinence in mid- or late-pregnancy or in the postpartum period.8 As the quality of this evidence is very low and there is no evidence of harm with PFME, we continue to recommend it for women with bothersome SUI.

Incontinence pessaries or vaginal inserts (such as Poise Impressa bladder supports) can be helpful for SUI treatment. An incontinence pessary can be fitted in the office, and fitting kits are available for both. Pessaries can safely be used in pregnancy, but there are no data on the efficacy of pessaries for treating SUI in pregnancy. In nonpregnant women, evidence demonstrates 63% satisfaction 3 months post–pessary placement for SUI.7

We do not recommend invasive procedures for the treatment of SUI during pregnancy or in the first 6 months following delivery. There is no evidence that elective cesarean delivery prevents persistent SUI postpartum.9

To identify and engage the proper pelvic floor muscles:

- Insert a finger in the vagina and squeeze the vaginal muscles around your finger.

- Imagine you are sitting on a marble and have to pick it up with the vaginal muscles.

- Squeeze the muscles you would use to stop the flow of urine or hold back flatulence.

Perform sets of 10, 2 to 3 times per day as follows:

- Squeeze: Engage the pelvic floor muscles as described above; avoid performing Kegels while voiding.

- Hold: For 2 to 10 seconds; increase the duration to 10 seconds as able.

- Relax: Completely relax muscles before initating the next squeeze.

Reference

1. UpToDate. Patient education: pelvic muscle (Kegel) exercises (the basics). 2018. https://uptodatefree.ir/topic.htm?path=pelvic-muscle-kegel-exercises-the-basics. Accessed February 24, 2021.

Continue to: Managing SUI in the postpartum period...

Managing SUI in the postpartum period

After the first 6 months postpartum and exhaustion of conservative measures, we offer surgical interventions for women with persistent, bothersome incontinence. Surgery for SUI typically is not recommended until childbearing is complete, but it can be considered if the patient’s bother is significant.

For women with bothersome SUI who still desire future pregnancy, management options include periurethral bulking, a retropubic urethropexy (Burch procedure), or a midurethral sling procedure. Women who undergo an anti-incontinence procedure have an increased risk for urinary retention during a subsequent pregnancy.10 Most women with a midurethral sling will continue to be continent following an obstetric delivery.

Anticipatory guidance

At 3 months postpartum, the incidence of urinary incontinence is 6% to 40%, depending on parity and delivery type. Postpartum urinary incontinence is most common after instrumented vaginal delivery (32%) followed by spontaneous vaginal delivery (28%) and cesarean delivery (15%). The mean prevalence of any type of urinary incontinence is 33% at 3 months postpartum, and only small changes in the rate of urinary incontinence occur over the first postpartum year.11 While urinary incontinence is common postpartum, it should not be considered normal. We counsel that symptoms may improve spontaneously, but treatment can be initiated if the patient experiences significant bother.

A longitudinal cohort study that followed women from 3 months to 12 years postpartum found that, of women with urinary incontinence at 3 months postpartum, 76% continued to report incontinence at 12 years postpartum.12 We recommend that women be counseled that, even when symptoms resolve, they remain at increased risk for urinary incontinence in the future. Invasive therapies should be used to treat bothersome urinary incontinence, not to prevent future incontinence.

CASE 3 Fecal incontinence

A 24-year-old woman (G1P1) presents 3 weeks postpartum following a forceps-assisted vaginal delivery complicated by a 3c laceration. She reports fecal urgency, inability to control flatus, and once-daily fecal incontinence.

How would you evaluate these symptoms?

Steps in evaluation

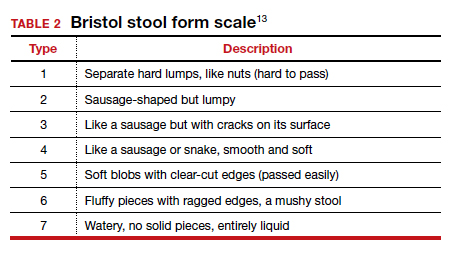

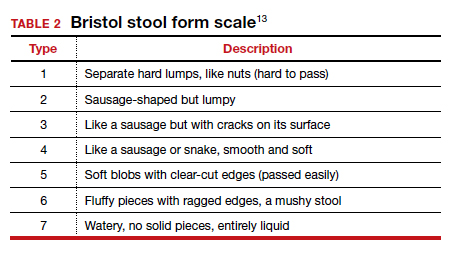

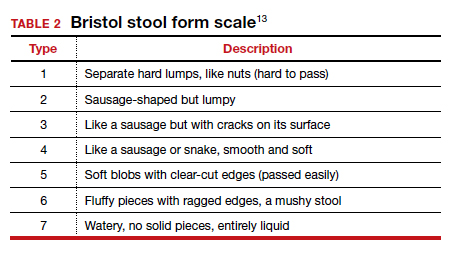

The initial evaluation should include an inquiry regarding the patient’s stool consistency and bowel regimen. The Bristol stool form scale can be used to help patients describe their typical bowel movements (TABLE 2).13 During healing, the goal is to achieve a Bristol type 4 stool, both to avoid straining and to improve continence, as loose stool is the most difficult to control.

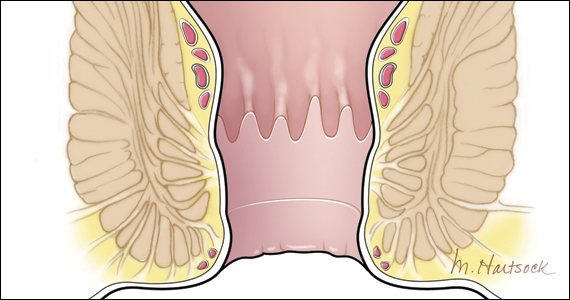

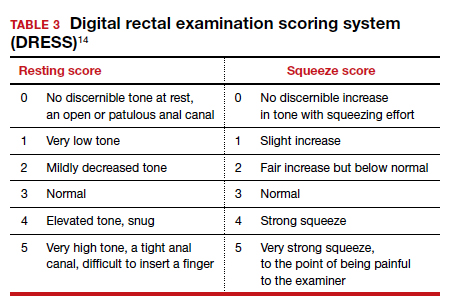

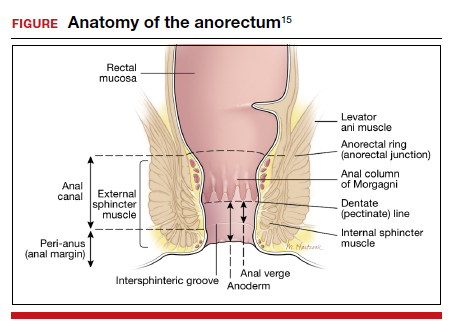

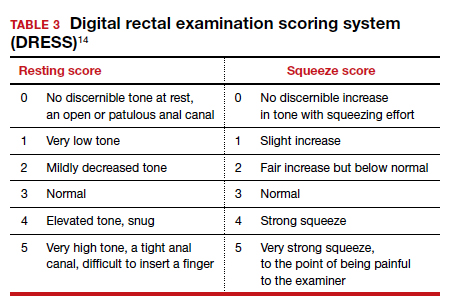

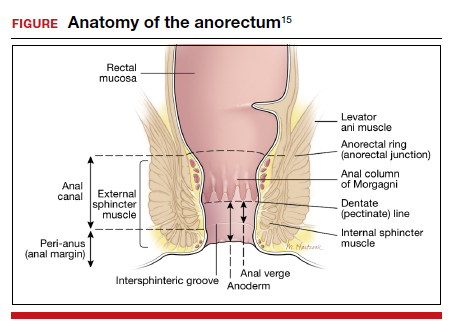

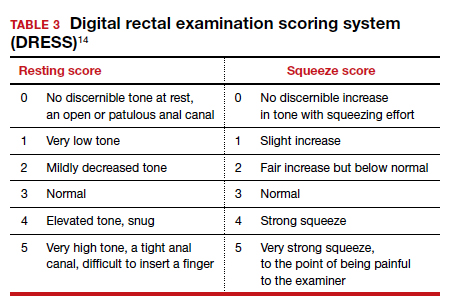

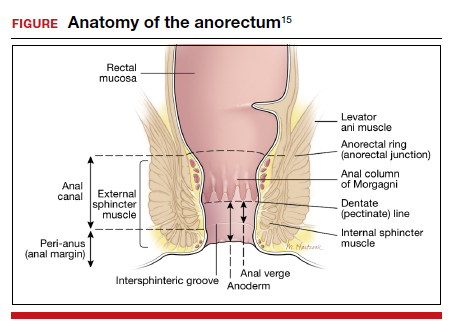

A physical examination can evaluate healing and sphincter integrity; it should include inspection of the distal vagina and perineal body and a digital rectal exam. Anal canal resting tone and squeeze strength should be evaluated, and the digital rectal examination scoring system (DRESS) can be useful for quantification (TABLE 3).14 Lack of tone at rest in the anterolateral portion of the sphincter complex can indicate an internal anal sphincter defect, as 80% of the resting tone comes from this muscle (FIGURE).15

The rectovaginal septum should be assessed given the increased risk of rectovaginal fistula in women with obstetric anal sphincter injury (OASI). The patient should be instructed to contract the anal sphincter, allowing evaluation of muscular contraction. Lack of contraction anteriolaterally may indicate external anal sphincter separation.

Continue to: Conservative options for improving fecal incontinence symptoms...