User login

Recommendations for lab monitoring of atypical antipsychotics

Mr. H, age 31, is admitted to an acute psychiatric unit with major depressive disorder, substance dependence, insomnia, and generalized anxiety. In the past, he was treated unsuccessfully with sertraline, fluoxetine, clonazepam, venlafaxine, and lithium. The treatment team starts Mr. H on quetiapine, titrated to 150 mg at bedtime, to address suspected bipolar II disorder.

At baseline, Mr. H is 68 inches tall and slightly overweight at 176 lbs (body mass index [BMI] 26.8 kg/m2). The laboratory reports his glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) at 5.4%; low-density lipoprotein (LDL), 60 mg/dL; total cholesterol, 122 mg/dL; triglycerides, 141 mg/dL; and high-density lipoprotein (HDL), 34 mg/dL.

Within 1 month, Mr. H experiences a 16% increase in body weight. HbA1c increases to 5.6%; LDL, to 93 mg/dL. These metabolic changes are not addressed, and he continues quetiapine for another 5 months. At the end of 6 months, Mr. H weighs 223.8 lbs (BMI 34 kg/m2)—a 27% increase from baseline. HbA1c is in the prediabetic range, at 5.9%, and LDL is 120 mg/dL.1 The treatment team discusses the risks of further metabolic effects, cardiovascular disease, and diabetes with Mr. H. He agrees to a change in therapy.

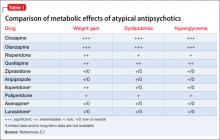

An increase in weight is thought to be associated with the actions of antipsychotics on H1and 5-HT2c receptors.7 Clozapine and olanzapine pose the highest risk of weight gain. Quetiapine and risperidone are considered of intermediate risk; aripiprazole and ziprasidone present the lowest risk(Table 1).5,7

Patients taking an atypical antipsychotic may experience an elevation of blood glucose, serum triglyceride, and LDL levels, and a decrease in the HDL level.2 These effects may be seen without an increase in BMI, and should be considered a direct effect of the antipsychotic.5 Although the mechanism by which dyslipidemia occurs is poorly understood, an increase in the blood glucose level is thought to be, in part, mediated by antagonism of M3 muscarinic receptors on pancreatic â-cells.7 Clozapine and olanzapine pose the highest risk of dyslipidemia. Quetiapine and risperidone are considered of intermediate risk; the risk associated with quetiapine is closer to that of olanzpine.8,9 Aripiprazole and ziprasidone present a lower risk of dyslipidemia and glucose elevations.5

Newer atypical antipsychotics, such as asenapine, iloperidone, paliperidone, and lurasidone, seem to have a lower metabolic risk profile, similar to those seen with aripiprazole and ziprasidone.5 Patients enrolled in initial clinical trials might not be antipsychotic naïve, however, and may have been taking a high metabolic risk antipsychotic. When these patients are switched to an antipsychotic that carries less of a metabolic risk, it might appear that they are experiencing a decrease in metabolic adverse events.

Metabolic data on newer atypical antipsychotics are limited; most have not been subject to long-term study. Routine monitoring of metabolic side effects is recommended for all atypical antipsychotics, regardless of risk profile.

Recommended monitoring

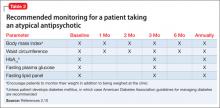

Because of the known metabolic side effects that occur in patients taking an atypical antipsychotic, baseline and periodic monitoring is recommended (Table 2).2,10 BMI and waist circumference should be recorded at baseline and tracked throughout treatment. Ideally, obtain measurements monthly for the first 3 months of therapy, or after any medication adjustments, then at 6 months, and annually thereafter. Encourage patients to track their own weight.

HbA1c and fasting plasma glucose levels should be measured at baseline and throughout the course of treatment. Obtain another set of measurements at 3 months, then annually thereafter, unless the patient develops type 2 diabetes mellitus.2

Obtaining a fasting lipid panel at baseline and periodically throughout the course of treatment is recommended. After baseline measurement, another panel should be taken at 3 months and annually thereafter. Guidelines of the American Diabetes Association recommend a fasting lipid panel every 5 years—however, good clinical practice dictates obtaining a lipid panel annually.

Managing metabolic side effects

Assess whether the patient can benefit from a lower dosage of current medication, switching to an antipsychotic with less of a risk of metabolic disturbance, or from discontinuation of therapy. In most cases, aim to use monotherapy because polypharmacy contributes to an increased risk of side effects.10

Weight management. Recommend nutrition counseling and physical activity for all patients who are overweight. Referral to a health care professional or to a program with expertise in weight management also might be beneficial.2 Include family members and significant others in the patient’s education when possible.

Impaired fasting glucose. Encourage a low-carbohydrate, high-protein diet with high intake of vegetables. Patients should obtain at least 30 minutes of physical activity, five times a week. Referral to a diabetes self-management class also is appropriate. Consider referral to a primary care physician or a clinician with expertise in diabetes.2

Impaired fasting lipids. Encourage your patients to adhere to a heart-healthy diet that is low in saturated fats and to get adequate physical activity. Referral to a dietician and primary care provider for medical management of dyslipidemia might be appropriate.2

Related Resources

- American Diabetes Association. Guide to living with diabetes. www.diabetes.org/living-with-diabetes.

- MOVE! Weight Management Program for Veterans. www. move.va.gov.

Drug Brand Names

Aripiprazole • Abilify

Asenapine • Saphris

Clonazepam • Klonopin

Clozapine • Clozaril

Fluoxetine • Prozac

Iloperidone • Fanapt

Lithium • Eskalith, Lithobid

Lurasidone • Latuda

Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Paliperidone • Invega

Quetiapine • Seroquel

Risperidone • Risperdal

Sertraline • Zoloft

Venlafaxine • Effexor

Ziprasidone • Geodon

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationships with any of the manufacturers mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. American Diabetes Association. Executive summary: standards of medical care in diabetes—2010. Diabetes Care. 2010;33:

S4-S10.

2. American Diabetes Association, American Psychiatric Association, American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, and the North American Association for the Study of Obesity. Consensus development conference on antipsychotic drugs and obesity and diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2004;27(2):596-601.

3. Kahn RS, Fleischhacker WW, Boter H, et al; EUFEST study group. Effectiveness of antipsychotic drugs in first-episode schizophrenia and schizophreniform disorder: an open randomised clinical trial. Lancet. 2008;371(9618):1085-1097.

4. Tarricone I, Ferrari Gozzi B, Serretti A, et al. Weight gain in antipsychotic-naive patients: a review and meta-analysis. Psychol Med. 2010;40(2):187-200.

5. De Hert M, Yu W, Detraux J, et al. Body weight and metabolic adverse effects of asenapine, iloperidone, lurasidone and paliperidone in the treatment of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder: a systematic review and exploratory meta-analysis. CNS Drugs. 2012;26(9):733-759.

6. De Hert M, Dobbelaere M, Sheridan EM, et al. Metabolic and endocrine adverse effects of second-generation antipsychotics in children and adolescents: a systematic review of randomized, placebo controlled trials and guidelines for clinical practice. Eur Psychiatry. 2011;26(3):144-158.

7. Stahl SM. Stahl’s essential psychopharmacology, neuroscientific basis and practical applications. Oxford, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press; 2008.

8. Lieberman JA, Stroup TS, McEvoy JP, et al; Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness (CATIE) Investigators. Effectiveness of antipsychotic drugs in patients with chronic schizophrenia. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(12):

1209-1223.

9. Correll CU, Manu P, Olshanskiy V, et al. Cardiometabolic risk of second-generation antipsychotic medications during first-time use in children and adolescents. JAMA. 2009;302(16):1765-1773.

10. Gothefors D, Adolfsson R, Attvall S, et al; Swedish Psychiatric Association. Swedish clinical guidelines – prevention and management of metabolic risk in patients with severe psychiatric disorders. Nord J Psychiatry. 2010;64(5):294-302.

11. Schneiderhan ME, Batscha CL, Rosen C. Assessment of a point-of-care metabolic risk screening program in outpatients receiving antipsychotic agents. Pharmacotherapy. 2009;29(8): 975-987.

Mr. H, age 31, is admitted to an acute psychiatric unit with major depressive disorder, substance dependence, insomnia, and generalized anxiety. In the past, he was treated unsuccessfully with sertraline, fluoxetine, clonazepam, venlafaxine, and lithium. The treatment team starts Mr. H on quetiapine, titrated to 150 mg at bedtime, to address suspected bipolar II disorder.

At baseline, Mr. H is 68 inches tall and slightly overweight at 176 lbs (body mass index [BMI] 26.8 kg/m2). The laboratory reports his glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) at 5.4%; low-density lipoprotein (LDL), 60 mg/dL; total cholesterol, 122 mg/dL; triglycerides, 141 mg/dL; and high-density lipoprotein (HDL), 34 mg/dL.

Within 1 month, Mr. H experiences a 16% increase in body weight. HbA1c increases to 5.6%; LDL, to 93 mg/dL. These metabolic changes are not addressed, and he continues quetiapine for another 5 months. At the end of 6 months, Mr. H weighs 223.8 lbs (BMI 34 kg/m2)—a 27% increase from baseline. HbA1c is in the prediabetic range, at 5.9%, and LDL is 120 mg/dL.1 The treatment team discusses the risks of further metabolic effects, cardiovascular disease, and diabetes with Mr. H. He agrees to a change in therapy.

An increase in weight is thought to be associated with the actions of antipsychotics on H1and 5-HT2c receptors.7 Clozapine and olanzapine pose the highest risk of weight gain. Quetiapine and risperidone are considered of intermediate risk; aripiprazole and ziprasidone present the lowest risk(Table 1).5,7

Patients taking an atypical antipsychotic may experience an elevation of blood glucose, serum triglyceride, and LDL levels, and a decrease in the HDL level.2 These effects may be seen without an increase in BMI, and should be considered a direct effect of the antipsychotic.5 Although the mechanism by which dyslipidemia occurs is poorly understood, an increase in the blood glucose level is thought to be, in part, mediated by antagonism of M3 muscarinic receptors on pancreatic â-cells.7 Clozapine and olanzapine pose the highest risk of dyslipidemia. Quetiapine and risperidone are considered of intermediate risk; the risk associated with quetiapine is closer to that of olanzpine.8,9 Aripiprazole and ziprasidone present a lower risk of dyslipidemia and glucose elevations.5

Newer atypical antipsychotics, such as asenapine, iloperidone, paliperidone, and lurasidone, seem to have a lower metabolic risk profile, similar to those seen with aripiprazole and ziprasidone.5 Patients enrolled in initial clinical trials might not be antipsychotic naïve, however, and may have been taking a high metabolic risk antipsychotic. When these patients are switched to an antipsychotic that carries less of a metabolic risk, it might appear that they are experiencing a decrease in metabolic adverse events.

Metabolic data on newer atypical antipsychotics are limited; most have not been subject to long-term study. Routine monitoring of metabolic side effects is recommended for all atypical antipsychotics, regardless of risk profile.

Recommended monitoring

Because of the known metabolic side effects that occur in patients taking an atypical antipsychotic, baseline and periodic monitoring is recommended (Table 2).2,10 BMI and waist circumference should be recorded at baseline and tracked throughout treatment. Ideally, obtain measurements monthly for the first 3 months of therapy, or after any medication adjustments, then at 6 months, and annually thereafter. Encourage patients to track their own weight.

HbA1c and fasting plasma glucose levels should be measured at baseline and throughout the course of treatment. Obtain another set of measurements at 3 months, then annually thereafter, unless the patient develops type 2 diabetes mellitus.2

Obtaining a fasting lipid panel at baseline and periodically throughout the course of treatment is recommended. After baseline measurement, another panel should be taken at 3 months and annually thereafter. Guidelines of the American Diabetes Association recommend a fasting lipid panel every 5 years—however, good clinical practice dictates obtaining a lipid panel annually.

Managing metabolic side effects

Assess whether the patient can benefit from a lower dosage of current medication, switching to an antipsychotic with less of a risk of metabolic disturbance, or from discontinuation of therapy. In most cases, aim to use monotherapy because polypharmacy contributes to an increased risk of side effects.10

Weight management. Recommend nutrition counseling and physical activity for all patients who are overweight. Referral to a health care professional or to a program with expertise in weight management also might be beneficial.2 Include family members and significant others in the patient’s education when possible.

Impaired fasting glucose. Encourage a low-carbohydrate, high-protein diet with high intake of vegetables. Patients should obtain at least 30 minutes of physical activity, five times a week. Referral to a diabetes self-management class also is appropriate. Consider referral to a primary care physician or a clinician with expertise in diabetes.2

Impaired fasting lipids. Encourage your patients to adhere to a heart-healthy diet that is low in saturated fats and to get adequate physical activity. Referral to a dietician and primary care provider for medical management of dyslipidemia might be appropriate.2

Related Resources

- American Diabetes Association. Guide to living with diabetes. www.diabetes.org/living-with-diabetes.

- MOVE! Weight Management Program for Veterans. www. move.va.gov.

Drug Brand Names

Aripiprazole • Abilify

Asenapine • Saphris

Clonazepam • Klonopin

Clozapine • Clozaril

Fluoxetine • Prozac

Iloperidone • Fanapt

Lithium • Eskalith, Lithobid

Lurasidone • Latuda

Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Paliperidone • Invega

Quetiapine • Seroquel

Risperidone • Risperdal

Sertraline • Zoloft

Venlafaxine • Effexor

Ziprasidone • Geodon

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationships with any of the manufacturers mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Mr. H, age 31, is admitted to an acute psychiatric unit with major depressive disorder, substance dependence, insomnia, and generalized anxiety. In the past, he was treated unsuccessfully with sertraline, fluoxetine, clonazepam, venlafaxine, and lithium. The treatment team starts Mr. H on quetiapine, titrated to 150 mg at bedtime, to address suspected bipolar II disorder.

At baseline, Mr. H is 68 inches tall and slightly overweight at 176 lbs (body mass index [BMI] 26.8 kg/m2). The laboratory reports his glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) at 5.4%; low-density lipoprotein (LDL), 60 mg/dL; total cholesterol, 122 mg/dL; triglycerides, 141 mg/dL; and high-density lipoprotein (HDL), 34 mg/dL.

Within 1 month, Mr. H experiences a 16% increase in body weight. HbA1c increases to 5.6%; LDL, to 93 mg/dL. These metabolic changes are not addressed, and he continues quetiapine for another 5 months. At the end of 6 months, Mr. H weighs 223.8 lbs (BMI 34 kg/m2)—a 27% increase from baseline. HbA1c is in the prediabetic range, at 5.9%, and LDL is 120 mg/dL.1 The treatment team discusses the risks of further metabolic effects, cardiovascular disease, and diabetes with Mr. H. He agrees to a change in therapy.

An increase in weight is thought to be associated with the actions of antipsychotics on H1and 5-HT2c receptors.7 Clozapine and olanzapine pose the highest risk of weight gain. Quetiapine and risperidone are considered of intermediate risk; aripiprazole and ziprasidone present the lowest risk(Table 1).5,7

Patients taking an atypical antipsychotic may experience an elevation of blood glucose, serum triglyceride, and LDL levels, and a decrease in the HDL level.2 These effects may be seen without an increase in BMI, and should be considered a direct effect of the antipsychotic.5 Although the mechanism by which dyslipidemia occurs is poorly understood, an increase in the blood glucose level is thought to be, in part, mediated by antagonism of M3 muscarinic receptors on pancreatic â-cells.7 Clozapine and olanzapine pose the highest risk of dyslipidemia. Quetiapine and risperidone are considered of intermediate risk; the risk associated with quetiapine is closer to that of olanzpine.8,9 Aripiprazole and ziprasidone present a lower risk of dyslipidemia and glucose elevations.5

Newer atypical antipsychotics, such as asenapine, iloperidone, paliperidone, and lurasidone, seem to have a lower metabolic risk profile, similar to those seen with aripiprazole and ziprasidone.5 Patients enrolled in initial clinical trials might not be antipsychotic naïve, however, and may have been taking a high metabolic risk antipsychotic. When these patients are switched to an antipsychotic that carries less of a metabolic risk, it might appear that they are experiencing a decrease in metabolic adverse events.

Metabolic data on newer atypical antipsychotics are limited; most have not been subject to long-term study. Routine monitoring of metabolic side effects is recommended for all atypical antipsychotics, regardless of risk profile.

Recommended monitoring

Because of the known metabolic side effects that occur in patients taking an atypical antipsychotic, baseline and periodic monitoring is recommended (Table 2).2,10 BMI and waist circumference should be recorded at baseline and tracked throughout treatment. Ideally, obtain measurements monthly for the first 3 months of therapy, or after any medication adjustments, then at 6 months, and annually thereafter. Encourage patients to track their own weight.

HbA1c and fasting plasma glucose levels should be measured at baseline and throughout the course of treatment. Obtain another set of measurements at 3 months, then annually thereafter, unless the patient develops type 2 diabetes mellitus.2

Obtaining a fasting lipid panel at baseline and periodically throughout the course of treatment is recommended. After baseline measurement, another panel should be taken at 3 months and annually thereafter. Guidelines of the American Diabetes Association recommend a fasting lipid panel every 5 years—however, good clinical practice dictates obtaining a lipid panel annually.

Managing metabolic side effects

Assess whether the patient can benefit from a lower dosage of current medication, switching to an antipsychotic with less of a risk of metabolic disturbance, or from discontinuation of therapy. In most cases, aim to use monotherapy because polypharmacy contributes to an increased risk of side effects.10

Weight management. Recommend nutrition counseling and physical activity for all patients who are overweight. Referral to a health care professional or to a program with expertise in weight management also might be beneficial.2 Include family members and significant others in the patient’s education when possible.

Impaired fasting glucose. Encourage a low-carbohydrate, high-protein diet with high intake of vegetables. Patients should obtain at least 30 minutes of physical activity, five times a week. Referral to a diabetes self-management class also is appropriate. Consider referral to a primary care physician or a clinician with expertise in diabetes.2

Impaired fasting lipids. Encourage your patients to adhere to a heart-healthy diet that is low in saturated fats and to get adequate physical activity. Referral to a dietician and primary care provider for medical management of dyslipidemia might be appropriate.2

Related Resources

- American Diabetes Association. Guide to living with diabetes. www.diabetes.org/living-with-diabetes.

- MOVE! Weight Management Program for Veterans. www. move.va.gov.

Drug Brand Names

Aripiprazole • Abilify

Asenapine • Saphris

Clonazepam • Klonopin

Clozapine • Clozaril

Fluoxetine • Prozac

Iloperidone • Fanapt

Lithium • Eskalith, Lithobid

Lurasidone • Latuda

Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Paliperidone • Invega

Quetiapine • Seroquel

Risperidone • Risperdal

Sertraline • Zoloft

Venlafaxine • Effexor

Ziprasidone • Geodon

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationships with any of the manufacturers mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. American Diabetes Association. Executive summary: standards of medical care in diabetes—2010. Diabetes Care. 2010;33:

S4-S10.

2. American Diabetes Association, American Psychiatric Association, American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, and the North American Association for the Study of Obesity. Consensus development conference on antipsychotic drugs and obesity and diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2004;27(2):596-601.

3. Kahn RS, Fleischhacker WW, Boter H, et al; EUFEST study group. Effectiveness of antipsychotic drugs in first-episode schizophrenia and schizophreniform disorder: an open randomised clinical trial. Lancet. 2008;371(9618):1085-1097.

4. Tarricone I, Ferrari Gozzi B, Serretti A, et al. Weight gain in antipsychotic-naive patients: a review and meta-analysis. Psychol Med. 2010;40(2):187-200.

5. De Hert M, Yu W, Detraux J, et al. Body weight and metabolic adverse effects of asenapine, iloperidone, lurasidone and paliperidone in the treatment of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder: a systematic review and exploratory meta-analysis. CNS Drugs. 2012;26(9):733-759.

6. De Hert M, Dobbelaere M, Sheridan EM, et al. Metabolic and endocrine adverse effects of second-generation antipsychotics in children and adolescents: a systematic review of randomized, placebo controlled trials and guidelines for clinical practice. Eur Psychiatry. 2011;26(3):144-158.

7. Stahl SM. Stahl’s essential psychopharmacology, neuroscientific basis and practical applications. Oxford, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press; 2008.

8. Lieberman JA, Stroup TS, McEvoy JP, et al; Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness (CATIE) Investigators. Effectiveness of antipsychotic drugs in patients with chronic schizophrenia. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(12):

1209-1223.

9. Correll CU, Manu P, Olshanskiy V, et al. Cardiometabolic risk of second-generation antipsychotic medications during first-time use in children and adolescents. JAMA. 2009;302(16):1765-1773.

10. Gothefors D, Adolfsson R, Attvall S, et al; Swedish Psychiatric Association. Swedish clinical guidelines – prevention and management of metabolic risk in patients with severe psychiatric disorders. Nord J Psychiatry. 2010;64(5):294-302.

11. Schneiderhan ME, Batscha CL, Rosen C. Assessment of a point-of-care metabolic risk screening program in outpatients receiving antipsychotic agents. Pharmacotherapy. 2009;29(8): 975-987.

1. American Diabetes Association. Executive summary: standards of medical care in diabetes—2010. Diabetes Care. 2010;33:

S4-S10.

2. American Diabetes Association, American Psychiatric Association, American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, and the North American Association for the Study of Obesity. Consensus development conference on antipsychotic drugs and obesity and diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2004;27(2):596-601.

3. Kahn RS, Fleischhacker WW, Boter H, et al; EUFEST study group. Effectiveness of antipsychotic drugs in first-episode schizophrenia and schizophreniform disorder: an open randomised clinical trial. Lancet. 2008;371(9618):1085-1097.

4. Tarricone I, Ferrari Gozzi B, Serretti A, et al. Weight gain in antipsychotic-naive patients: a review and meta-analysis. Psychol Med. 2010;40(2):187-200.

5. De Hert M, Yu W, Detraux J, et al. Body weight and metabolic adverse effects of asenapine, iloperidone, lurasidone and paliperidone in the treatment of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder: a systematic review and exploratory meta-analysis. CNS Drugs. 2012;26(9):733-759.

6. De Hert M, Dobbelaere M, Sheridan EM, et al. Metabolic and endocrine adverse effects of second-generation antipsychotics in children and adolescents: a systematic review of randomized, placebo controlled trials and guidelines for clinical practice. Eur Psychiatry. 2011;26(3):144-158.

7. Stahl SM. Stahl’s essential psychopharmacology, neuroscientific basis and practical applications. Oxford, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press; 2008.

8. Lieberman JA, Stroup TS, McEvoy JP, et al; Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness (CATIE) Investigators. Effectiveness of antipsychotic drugs in patients with chronic schizophrenia. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(12):

1209-1223.

9. Correll CU, Manu P, Olshanskiy V, et al. Cardiometabolic risk of second-generation antipsychotic medications during first-time use in children and adolescents. JAMA. 2009;302(16):1765-1773.

10. Gothefors D, Adolfsson R, Attvall S, et al; Swedish Psychiatric Association. Swedish clinical guidelines – prevention and management of metabolic risk in patients with severe psychiatric disorders. Nord J Psychiatry. 2010;64(5):294-302.

11. Schneiderhan ME, Batscha CL, Rosen C. Assessment of a point-of-care metabolic risk screening program in outpatients receiving antipsychotic agents. Pharmacotherapy. 2009;29(8): 975-987.