User login

Pruritic Papules on the Trunk, Extremities, and Face

The Diagnosis: Gamasoidosis

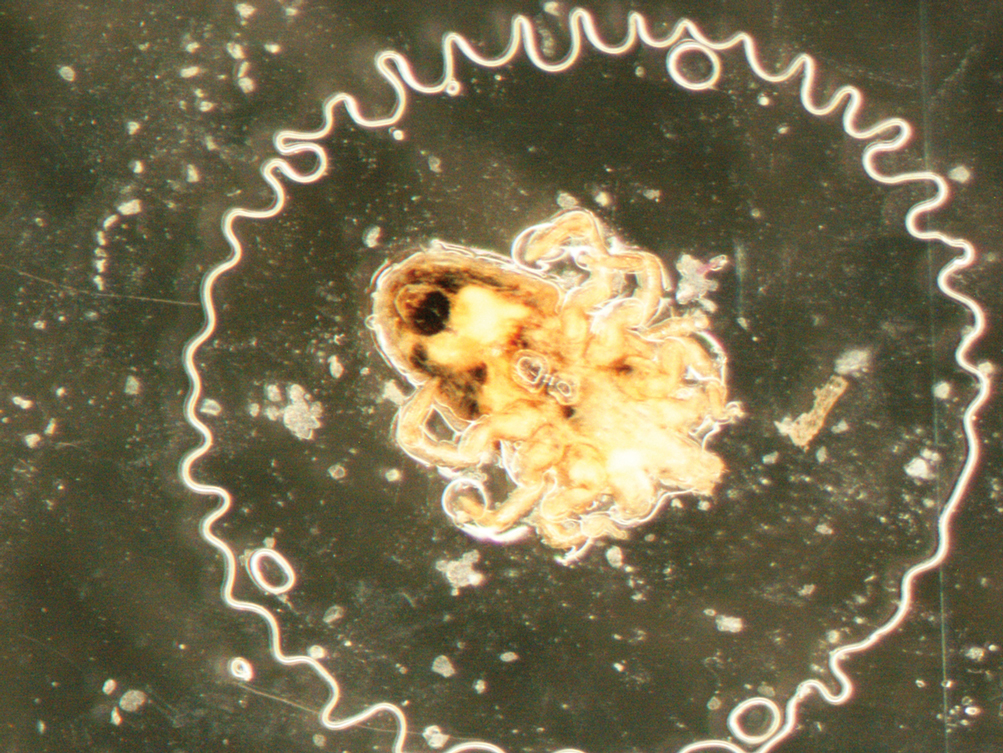

An entomologist confirmed the specimen as an avian mite in either the Dermanyssus or Ornithonyssus genera (quiz image [bottom]). The patient was asked whether any bird had nested around her bedroom, and she affirmed that a woodpecker had nested outside her bedroom closet that spring. She subsequently discovered it had burrowed a hole into her closet wall. She and her husband removed the nest, and within 4 weeks, the eruption permanently cleared.

Gamasoidosis, or avian mite dermatitis, often is an overlooked, difficult-to-make diagnosis that is increasing in prevalence.1 Bird mites are ectoparasitic arthropods that are 0.3 to 1 mm in length. They have egg-shaped bodies with 4 pairs of legs; they are a translucent brown color before feeding and red after feeding.2 Although most avian mites cannot subsist off human blood, if the mites are without an avian host, such as after affected birds abandon their nests, the mites will bite humans.3 Studies have discovered the presence of mammalian erythrocytes in the digestive tracts of one species of bird mite, Dermanyssus gallinae, suggesting that at least one form of avian mite may feed off humans but typically cannot reproduce without an avian blood meal.4 Individuals with gamasoidosis often are exposed to avian mites by owning birds as pets, rearing chickens or messenger pigeons, or having bird’s nests around their bedrooms or air conditioning units.1

Most people who develop avian mite dermatitis are the only affected member of the family to develop pruritus and papules since the reaction requires both bites and hypersensitivity to them; however, there are cases of nuclear families all reacting to avian mite bites.2,4 As in this case, hypersensitivity to avian mite bites causes exquisitely pruritic 2- to 5-mm papules, vesicles, or urticarial lesions that may be diagnosed as papular urticaria or misdiagnosed as scabies. Although bird mites may carry bacteria such as Salmonella, Spirochaete, Rickettsia, and Pasteurella, they have not demonstrated an ability to pass these on to human vectors.5,6

Bird mites will spend most of their lives on avian hosts but can spread to humans through direct contact or through air.7 Mites can go through floors, walls, ceilings, or most commonly through ventilation or air conditioning units. Increasing urbanization, especially in warmer climates where avian mites thrive, has increased the prevalence of gamasoidosis.1

Avian mite dermatitis commonly can be mistaken for scabies, but the mites can be seen with the naked eye and cannot form burrows, unlike scabies.4,8 Avian mites usually are not found on human skin since they leave the host after feeding and move with surprising speed.8 Pediculosis corporis (body lice) results from an infestation of Pediculus humanus corporis. At 2- to 4-mm long, this louse is much larger than a bird mite. Body lice rarely are found on the skin but rather live and lay eggs on clothing, particularly along the seams. The body louse has an elongated body with 3 segments and short antennae. Pthirus pubis (pubic lice) measure 1.5 to 2.0 mm in adulthood and have wider, more crablike bodies compared to body or hair lice or avian mites. Lice, being insects, have 6 legs as opposed to mites, being arachnids, having 8 legs. Cheyletiella are 0.5-mm long, nonburrowing mites commonly found on cats, dogs, and rabbits. Cheyletiella blakei affects cats. They look somewhat similar to bird mites but have hooklike palps extending from their heads instead of antennae.

Antihistamines and topical corticosteroids may reduce discomfort from avian bites but are not curative.2,9 The most efficient way to treat gamasoidosis is to remove any affected birds or nearby bird’s nests, as the mites cannot survive more than a few weeks to months without feeding on an avian host.8 It also may be necessary to fumigate infested rooms.10

The diagnosis of avian mite dermatitis often is missed to the frustration of the patient and clinician alike. Becoming familiar with this bite reaction will help clinicians diagnose this dermatologic conundrum.

- Wambier CG, de Farias Wambier SP. Gamasoidosis illustrated— from the nest to dermoscopy. An Bras Dermatol. 2012;87:926-927. doi:10.1590/s0365-05962012000600021

- Collgros H, Iglesias-Sancho M, Aldunce MJ, et al. Dermanyssus gallinae (chicken mite): an underdiagnosed environmental infestation. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2013;38:374-377.

- Akdemir C, Gülcan E, Tanritanir P. Case report: Dermanyssus gallinae in a patient with pruritus and skin lesions. Turkiye Parazitol Derg. 2009;33:242-244.

- Williams RW. An infestation of a human habitation by Dermanyssus gallinae (de Geer, 1778)(Acarina: Dermanyssidae) in New York resulting in sanguisugent attacks upon the occupants. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1958;7:627-629.

- Walker A. The Arthropods of Humans and Domestic Animals. A Guide to Preliminary Identification. Chapman and Hall; 1994.

- Vaiente MC, Chauve C, Zenner L. Experimental infection of Salmonella enteritidis by the poultry red mite, Dermanyssus gallinae. Vet Parasitol. 2007;146:329-336.

- Regan AM, Metersky ML, Craven DE. Nosocomial dermatitis and pruritus caused by pigeon mite infestation. Arch Intern Med. 1987;147:2185-2187.

- Orton DI, Warren LJ, Wilkinson JD. Avian mite dermatitis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2000;25:129-131.

- Bassini-Silva R, de Castro Jacinavicius F, Akashi Hernandes F, et al. Dermatitis in humans caused by Ornithonyssus bursa (Berlese 1888) (Mesostigmata: Macronyssidae) and new records from Brazil. Rev Bras Parasitol Vet. 2019;28:134-139.

- Watson CR. Human infestation with bird mites in Wollongong. Commun Dis Intell Q Rep. 2003;27:259-261.

The Diagnosis: Gamasoidosis

An entomologist confirmed the specimen as an avian mite in either the Dermanyssus or Ornithonyssus genera (quiz image [bottom]). The patient was asked whether any bird had nested around her bedroom, and she affirmed that a woodpecker had nested outside her bedroom closet that spring. She subsequently discovered it had burrowed a hole into her closet wall. She and her husband removed the nest, and within 4 weeks, the eruption permanently cleared.

Gamasoidosis, or avian mite dermatitis, often is an overlooked, difficult-to-make diagnosis that is increasing in prevalence.1 Bird mites are ectoparasitic arthropods that are 0.3 to 1 mm in length. They have egg-shaped bodies with 4 pairs of legs; they are a translucent brown color before feeding and red after feeding.2 Although most avian mites cannot subsist off human blood, if the mites are without an avian host, such as after affected birds abandon their nests, the mites will bite humans.3 Studies have discovered the presence of mammalian erythrocytes in the digestive tracts of one species of bird mite, Dermanyssus gallinae, suggesting that at least one form of avian mite may feed off humans but typically cannot reproduce without an avian blood meal.4 Individuals with gamasoidosis often are exposed to avian mites by owning birds as pets, rearing chickens or messenger pigeons, or having bird’s nests around their bedrooms or air conditioning units.1

Most people who develop avian mite dermatitis are the only affected member of the family to develop pruritus and papules since the reaction requires both bites and hypersensitivity to them; however, there are cases of nuclear families all reacting to avian mite bites.2,4 As in this case, hypersensitivity to avian mite bites causes exquisitely pruritic 2- to 5-mm papules, vesicles, or urticarial lesions that may be diagnosed as papular urticaria or misdiagnosed as scabies. Although bird mites may carry bacteria such as Salmonella, Spirochaete, Rickettsia, and Pasteurella, they have not demonstrated an ability to pass these on to human vectors.5,6

Bird mites will spend most of their lives on avian hosts but can spread to humans through direct contact or through air.7 Mites can go through floors, walls, ceilings, or most commonly through ventilation or air conditioning units. Increasing urbanization, especially in warmer climates where avian mites thrive, has increased the prevalence of gamasoidosis.1

Avian mite dermatitis commonly can be mistaken for scabies, but the mites can be seen with the naked eye and cannot form burrows, unlike scabies.4,8 Avian mites usually are not found on human skin since they leave the host after feeding and move with surprising speed.8 Pediculosis corporis (body lice) results from an infestation of Pediculus humanus corporis. At 2- to 4-mm long, this louse is much larger than a bird mite. Body lice rarely are found on the skin but rather live and lay eggs on clothing, particularly along the seams. The body louse has an elongated body with 3 segments and short antennae. Pthirus pubis (pubic lice) measure 1.5 to 2.0 mm in adulthood and have wider, more crablike bodies compared to body or hair lice or avian mites. Lice, being insects, have 6 legs as opposed to mites, being arachnids, having 8 legs. Cheyletiella are 0.5-mm long, nonburrowing mites commonly found on cats, dogs, and rabbits. Cheyletiella blakei affects cats. They look somewhat similar to bird mites but have hooklike palps extending from their heads instead of antennae.

Antihistamines and topical corticosteroids may reduce discomfort from avian bites but are not curative.2,9 The most efficient way to treat gamasoidosis is to remove any affected birds or nearby bird’s nests, as the mites cannot survive more than a few weeks to months without feeding on an avian host.8 It also may be necessary to fumigate infested rooms.10

The diagnosis of avian mite dermatitis often is missed to the frustration of the patient and clinician alike. Becoming familiar with this bite reaction will help clinicians diagnose this dermatologic conundrum.

The Diagnosis: Gamasoidosis

An entomologist confirmed the specimen as an avian mite in either the Dermanyssus or Ornithonyssus genera (quiz image [bottom]). The patient was asked whether any bird had nested around her bedroom, and she affirmed that a woodpecker had nested outside her bedroom closet that spring. She subsequently discovered it had burrowed a hole into her closet wall. She and her husband removed the nest, and within 4 weeks, the eruption permanently cleared.

Gamasoidosis, or avian mite dermatitis, often is an overlooked, difficult-to-make diagnosis that is increasing in prevalence.1 Bird mites are ectoparasitic arthropods that are 0.3 to 1 mm in length. They have egg-shaped bodies with 4 pairs of legs; they are a translucent brown color before feeding and red after feeding.2 Although most avian mites cannot subsist off human blood, if the mites are without an avian host, such as after affected birds abandon their nests, the mites will bite humans.3 Studies have discovered the presence of mammalian erythrocytes in the digestive tracts of one species of bird mite, Dermanyssus gallinae, suggesting that at least one form of avian mite may feed off humans but typically cannot reproduce without an avian blood meal.4 Individuals with gamasoidosis often are exposed to avian mites by owning birds as pets, rearing chickens or messenger pigeons, or having bird’s nests around their bedrooms or air conditioning units.1

Most people who develop avian mite dermatitis are the only affected member of the family to develop pruritus and papules since the reaction requires both bites and hypersensitivity to them; however, there are cases of nuclear families all reacting to avian mite bites.2,4 As in this case, hypersensitivity to avian mite bites causes exquisitely pruritic 2- to 5-mm papules, vesicles, or urticarial lesions that may be diagnosed as papular urticaria or misdiagnosed as scabies. Although bird mites may carry bacteria such as Salmonella, Spirochaete, Rickettsia, and Pasteurella, they have not demonstrated an ability to pass these on to human vectors.5,6

Bird mites will spend most of their lives on avian hosts but can spread to humans through direct contact or through air.7 Mites can go through floors, walls, ceilings, or most commonly through ventilation or air conditioning units. Increasing urbanization, especially in warmer climates where avian mites thrive, has increased the prevalence of gamasoidosis.1

Avian mite dermatitis commonly can be mistaken for scabies, but the mites can be seen with the naked eye and cannot form burrows, unlike scabies.4,8 Avian mites usually are not found on human skin since they leave the host after feeding and move with surprising speed.8 Pediculosis corporis (body lice) results from an infestation of Pediculus humanus corporis. At 2- to 4-mm long, this louse is much larger than a bird mite. Body lice rarely are found on the skin but rather live and lay eggs on clothing, particularly along the seams. The body louse has an elongated body with 3 segments and short antennae. Pthirus pubis (pubic lice) measure 1.5 to 2.0 mm in adulthood and have wider, more crablike bodies compared to body or hair lice or avian mites. Lice, being insects, have 6 legs as opposed to mites, being arachnids, having 8 legs. Cheyletiella are 0.5-mm long, nonburrowing mites commonly found on cats, dogs, and rabbits. Cheyletiella blakei affects cats. They look somewhat similar to bird mites but have hooklike palps extending from their heads instead of antennae.

Antihistamines and topical corticosteroids may reduce discomfort from avian bites but are not curative.2,9 The most efficient way to treat gamasoidosis is to remove any affected birds or nearby bird’s nests, as the mites cannot survive more than a few weeks to months without feeding on an avian host.8 It also may be necessary to fumigate infested rooms.10

The diagnosis of avian mite dermatitis often is missed to the frustration of the patient and clinician alike. Becoming familiar with this bite reaction will help clinicians diagnose this dermatologic conundrum.

- Wambier CG, de Farias Wambier SP. Gamasoidosis illustrated— from the nest to dermoscopy. An Bras Dermatol. 2012;87:926-927. doi:10.1590/s0365-05962012000600021

- Collgros H, Iglesias-Sancho M, Aldunce MJ, et al. Dermanyssus gallinae (chicken mite): an underdiagnosed environmental infestation. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2013;38:374-377.

- Akdemir C, Gülcan E, Tanritanir P. Case report: Dermanyssus gallinae in a patient with pruritus and skin lesions. Turkiye Parazitol Derg. 2009;33:242-244.

- Williams RW. An infestation of a human habitation by Dermanyssus gallinae (de Geer, 1778)(Acarina: Dermanyssidae) in New York resulting in sanguisugent attacks upon the occupants. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1958;7:627-629.

- Walker A. The Arthropods of Humans and Domestic Animals. A Guide to Preliminary Identification. Chapman and Hall; 1994.

- Vaiente MC, Chauve C, Zenner L. Experimental infection of Salmonella enteritidis by the poultry red mite, Dermanyssus gallinae. Vet Parasitol. 2007;146:329-336.

- Regan AM, Metersky ML, Craven DE. Nosocomial dermatitis and pruritus caused by pigeon mite infestation. Arch Intern Med. 1987;147:2185-2187.

- Orton DI, Warren LJ, Wilkinson JD. Avian mite dermatitis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2000;25:129-131.

- Bassini-Silva R, de Castro Jacinavicius F, Akashi Hernandes F, et al. Dermatitis in humans caused by Ornithonyssus bursa (Berlese 1888) (Mesostigmata: Macronyssidae) and new records from Brazil. Rev Bras Parasitol Vet. 2019;28:134-139.

- Watson CR. Human infestation with bird mites in Wollongong. Commun Dis Intell Q Rep. 2003;27:259-261.

- Wambier CG, de Farias Wambier SP. Gamasoidosis illustrated— from the nest to dermoscopy. An Bras Dermatol. 2012;87:926-927. doi:10.1590/s0365-05962012000600021

- Collgros H, Iglesias-Sancho M, Aldunce MJ, et al. Dermanyssus gallinae (chicken mite): an underdiagnosed environmental infestation. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2013;38:374-377.

- Akdemir C, Gülcan E, Tanritanir P. Case report: Dermanyssus gallinae in a patient with pruritus and skin lesions. Turkiye Parazitol Derg. 2009;33:242-244.

- Williams RW. An infestation of a human habitation by Dermanyssus gallinae (de Geer, 1778)(Acarina: Dermanyssidae) in New York resulting in sanguisugent attacks upon the occupants. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1958;7:627-629.

- Walker A. The Arthropods of Humans and Domestic Animals. A Guide to Preliminary Identification. Chapman and Hall; 1994.

- Vaiente MC, Chauve C, Zenner L. Experimental infection of Salmonella enteritidis by the poultry red mite, Dermanyssus gallinae. Vet Parasitol. 2007;146:329-336.

- Regan AM, Metersky ML, Craven DE. Nosocomial dermatitis and pruritus caused by pigeon mite infestation. Arch Intern Med. 1987;147:2185-2187.

- Orton DI, Warren LJ, Wilkinson JD. Avian mite dermatitis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2000;25:129-131.

- Bassini-Silva R, de Castro Jacinavicius F, Akashi Hernandes F, et al. Dermatitis in humans caused by Ornithonyssus bursa (Berlese 1888) (Mesostigmata: Macronyssidae) and new records from Brazil. Rev Bras Parasitol Vet. 2019;28:134-139.

- Watson CR. Human infestation with bird mites in Wollongong. Commun Dis Intell Q Rep. 2003;27:259-261.

A 69-year-old woman presented in early summer in southeastern Michigan with several itchy bumps (top) of 4 to 5 weeks’ duration that erupted and remitted over the trunk, extremities, and face. She had taken no new medications. She had an asymptomatic cat and no exposure to anyone else who had been itching. Physical examination revealed approximately a dozen 2- to 5-mm edematous papules on the trunk, arms, shins, thighs, and left cheek, as well as one 3-mm vesicle on the forearm. No burrows could be identified on physical examination. Lesions treated with betamethasone dipropionate cream 0.05% improved, but new lesions continued to arise. An exterminator was contacted but found no signs of bedbugs or other infestations. Later, the patient reported seeing 3 tiny black dots crawl across the screen of her cell phone as she read in bed. She was able to capture them on tape and bring them to her appointment. The specimens were approximately 1 mm in length (bottom).