User login

Cutaneous Metastatic Breast Adenocarcinoma

To the Editor:

Cutaneous metastases occur more often in the setting of breast carcinoma than other malignancies in women.1 Although interventions are aimed at halting disease progression, cutaneous metastases indicate widespread disease and are associated with poor prognosis. We present the case of a patient with metastatic breast adenocarcinoma who developed cutaneous metastasis on the trunk after a double mastectomy. The widespread distribution and wide range of clinical manifestations are unique.

An 81-year-old woman presented to the dermatology office for evaluation of a skin eruption that started along a mastectomy scar on the left breast a few months postoperatively. She had a history of stage IV breast adenocarcinoma metastatic to the chest wall that was treated with a double mastectomy 2 years prior. The patient denied associated pain or pruritus and mainly was concerned with the cosmetic appearance. At the time of the initial diagnosis of breast adenocarcinoma, the patient was offered chemotherapy, which she did not tolerate. The patient opted against radiation therapy, as she preferred a more natural approach, such as anticancer shakes, which she was taking from a homeopathic source. She was unaware of the ingredients used in the shakes.

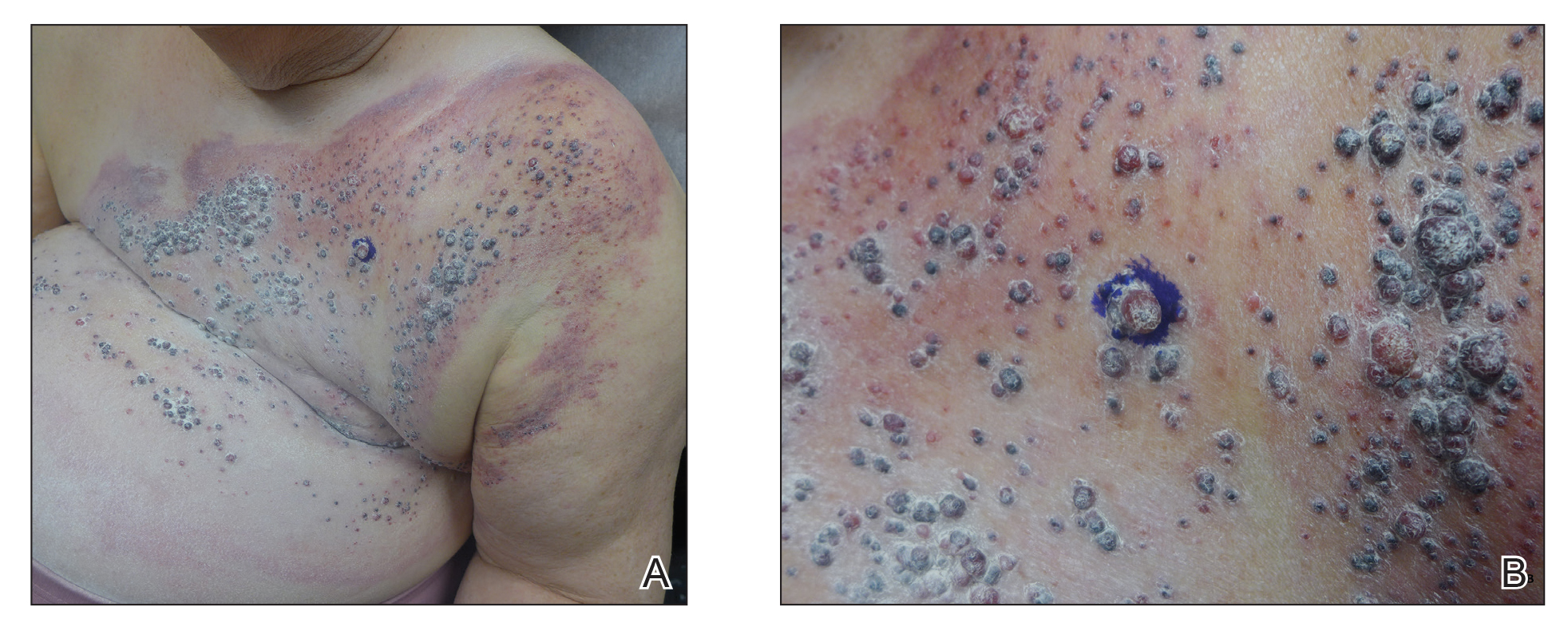

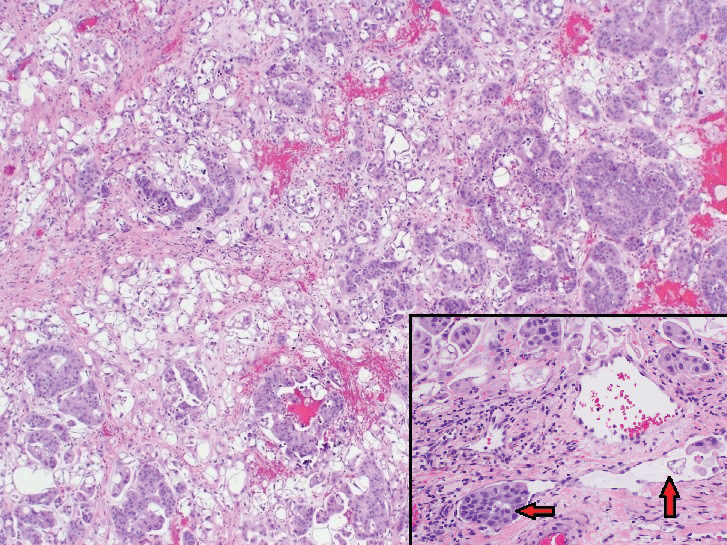

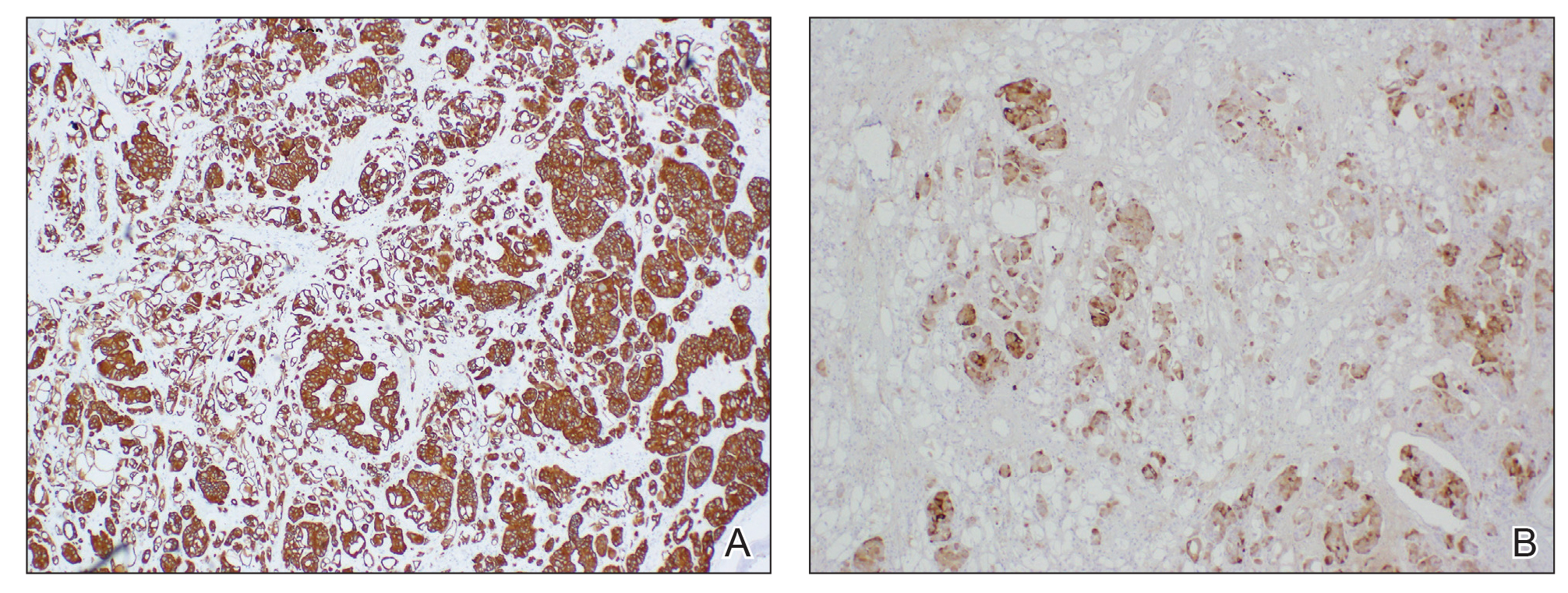

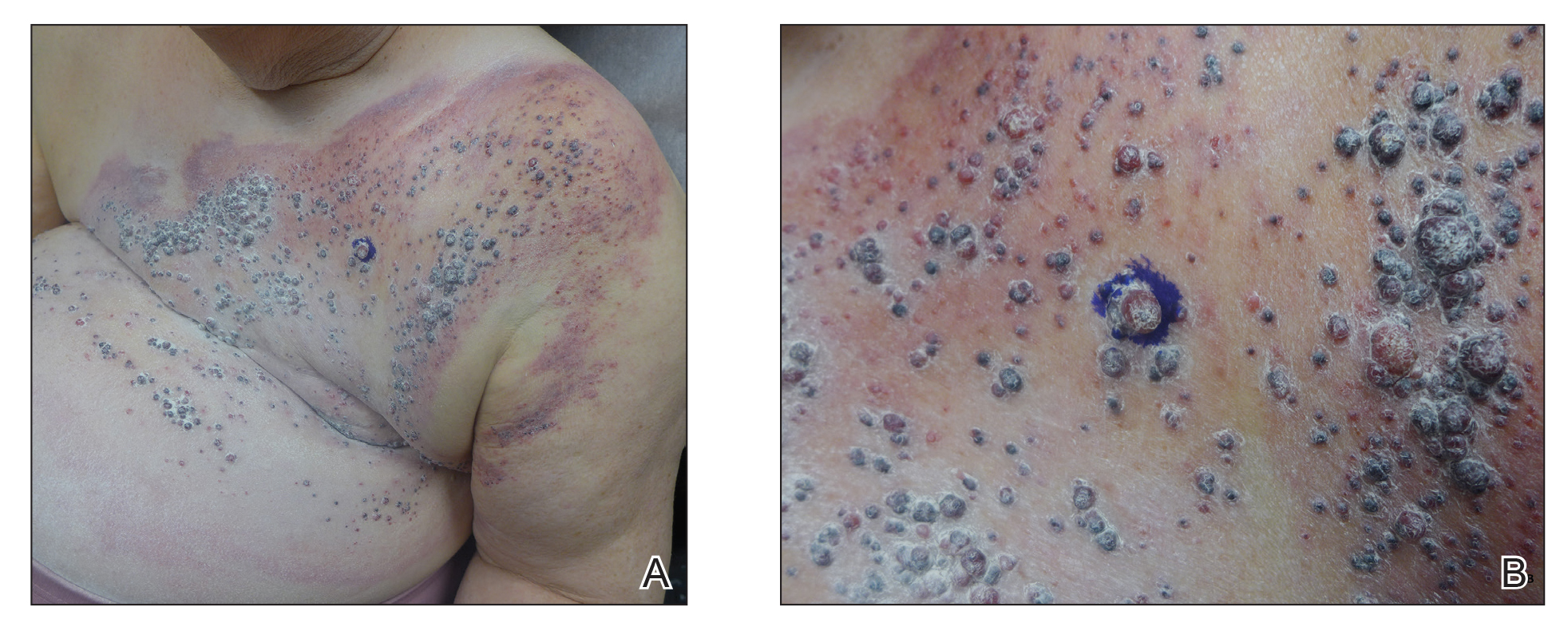

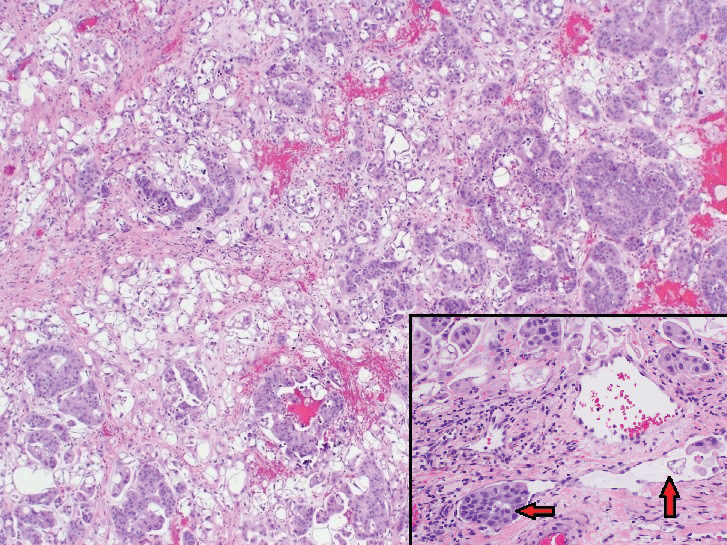

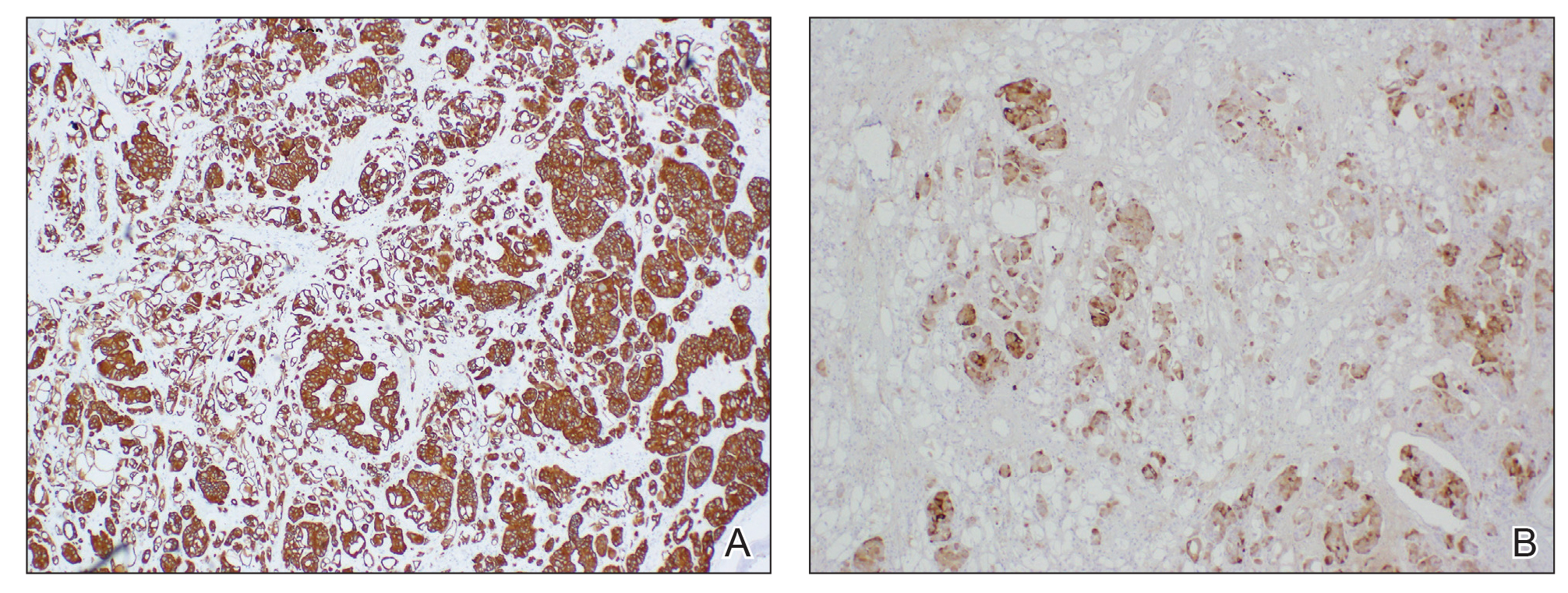

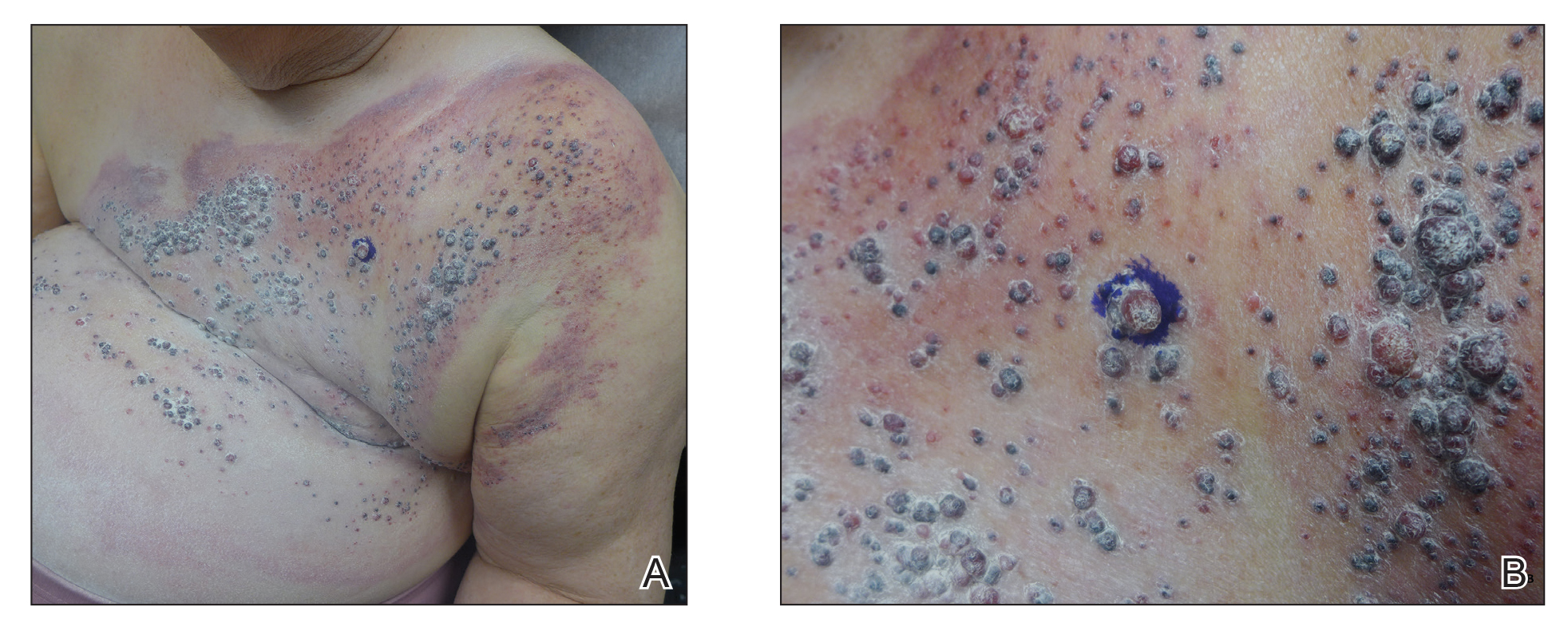

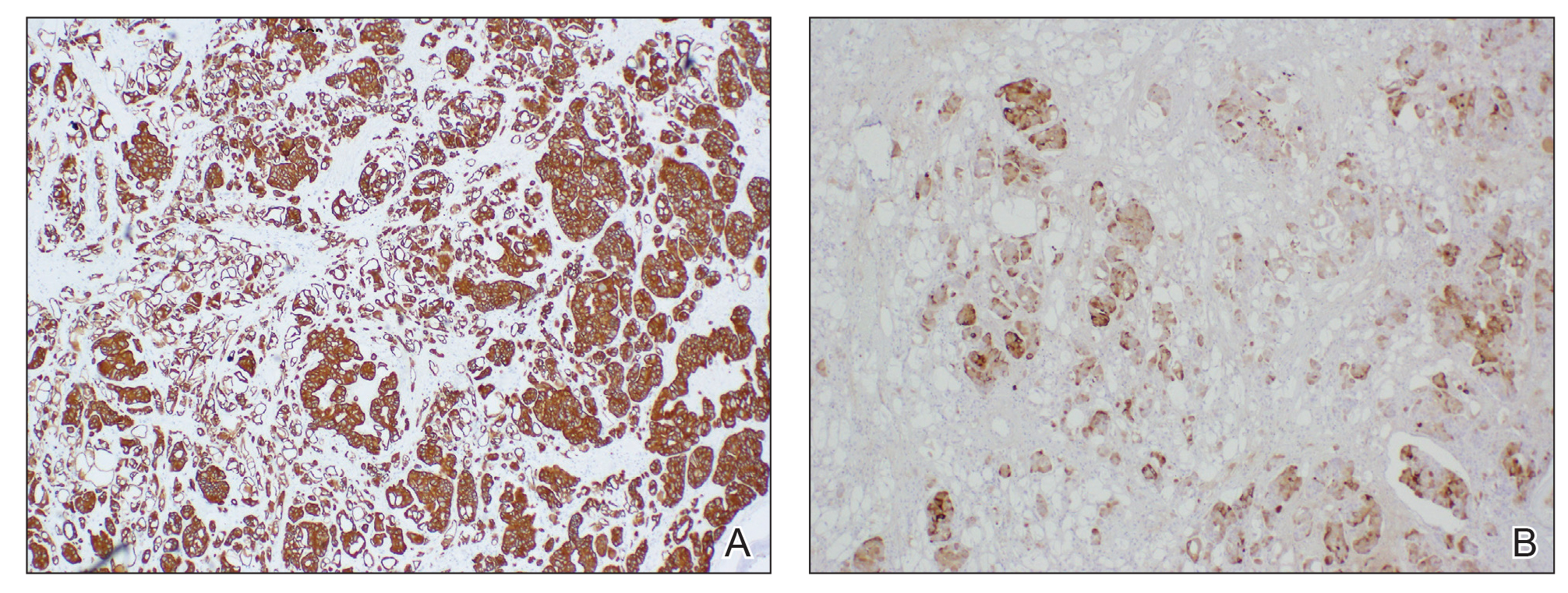

Physical examination revealed multiple grouped, firm, purpuric papules, nodules, and pseudovesicles on a background of violaceous erythema on the chest, abdomen, and flank (Figure 1). The background erythema had a mosaic pattern that extended toward the central back (Figure 2). A scoop shave biopsy of one of the purpuric nodules revealed highly atypical cells with abundant cytoplasm, large nuclei, and prominent nucleoli (Figure 3). Focally, the cells appeared to form glandular structures. Numerous atypical mitotic figures were present. Lymphatic invasion and microcalcifications were identified (Figure 3 [inset]). Immunohistochemical staining for cytokeratin 7 and gross cystic disease fluid protein 15 were strongly positive (Figure 4). Based on the histopathologic and immunohistochemical findings, a diagnosis of cutaneous metastatic breast adenocarcinoma was made. The patient opted to continue the homeopathic anticancer shakes and was subsequently lost to follow-up.

Cutaneous metastases of internal malignancies make up only 2% of all skin tumors,1 making them relatively uncommon in the dermatologic setting. However, cutaneous metastasis occurs in 23.9% of patients with breast carcinoma, making it the most common tumor after malignant melanoma to metastasize to the skin.2 The most common sites for breast carcinoma cutaneous metastasis (BCCM) are the chest wall and abdomen; other sites include the head/neck region and the extremities. The clinical presentation of BCCM varies depending on the mode of dissemination—lymphatic, hematogenous, contiguous growth, or iatrogenic implantation. The most common presentation is nodular carcinoma (47%–80%).2,3 Other presentations include carcinoma telangiectoides (8%–11%),2,3 alopecia neoplastica (2%–12%),2,3 and carcinoma erysipeloides (3%–6%).2,3 Carcinoma en cuirasse is rare.3

Nodular BCCM may present as firm solitary or grouped papules and nodules that are painless and range in color from flesh colored or pink to red-brown. Histologically, they are composed of atypical neoplastic cells arranged in small nests and cords, usually in a single-file line within the collagen bundles of the dermis.4 Carcinoma telangiectoides is characterized by its violaceous hue due to the dilated vascular channels. The lesions are purpuric papules and pseudovesicles appearing on an erythematous base, most commonly contiguous with the surgical scar. Histologically, collections of atypical tumor cells and erythrocytes are present along with dilated blood vessels in the papillary dermis.2 Alopecia neoplastica presents as singular or grouped cicatricial patches of hair loss. Lesions of carcinoma erysipeloides present as warm, erythematous, tender, well-defined patches or plaques. Carcinoma en cuirasse is characterized by an erythematous sclerodermoid plaque on the chest wall.2

Our patient’s presentation was unique due to the widespread distribution, unusual pattern, and variable clinical morphologies of the cutaneous metastases. Our patient had findings of both carcinoma telangiectoides and nodular carcinoma. The mosaic violaceous erythema extending toward the mid-back rarely is reported in the literature and indicates extensive intravascular spread of tumor cells in the dermis.

Metastatic breast cancer is associated with a poor prognosis because it typically occurs in advanced stages and often does not respond to treatment.5 Although chemotherapy, hormonal therapy, and/or radiation therapy may improve survival, the choice in regimen is guided by cancer histology as well as prior treatments. In our case, the patient chose to continue her homeopathic therapy.

- Nashan D, Meiss F, Braun-Falco M, et al. Cutaneous metastasis from internal malignancies. Dermatol Ther. 2010;23:567-580.

- De Giorgi V, Grazzini M, Alfaioli B, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of breast carcinoma. Dermatol Ther. 2010;23:581-589.

- Mordenti C, Peris K, Concetta Fargnoli M, et al. Cutaneous metastatic breast carcinoma. Acta Dermatovenerologica. 2000;9:143-148.

- Nava G, Greer K, Patterson J, et al. Metastatic cutaneous breast carcinoma: a case report and review of the literature. Can J Plast Surg. 2009;17:25-27.

- Kalmykow B, Walker S. Cutaneous metastasis in breast cancer. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2001;15:99-101.

To the Editor:

Cutaneous metastases occur more often in the setting of breast carcinoma than other malignancies in women.1 Although interventions are aimed at halting disease progression, cutaneous metastases indicate widespread disease and are associated with poor prognosis. We present the case of a patient with metastatic breast adenocarcinoma who developed cutaneous metastasis on the trunk after a double mastectomy. The widespread distribution and wide range of clinical manifestations are unique.

An 81-year-old woman presented to the dermatology office for evaluation of a skin eruption that started along a mastectomy scar on the left breast a few months postoperatively. She had a history of stage IV breast adenocarcinoma metastatic to the chest wall that was treated with a double mastectomy 2 years prior. The patient denied associated pain or pruritus and mainly was concerned with the cosmetic appearance. At the time of the initial diagnosis of breast adenocarcinoma, the patient was offered chemotherapy, which she did not tolerate. The patient opted against radiation therapy, as she preferred a more natural approach, such as anticancer shakes, which she was taking from a homeopathic source. She was unaware of the ingredients used in the shakes.

Physical examination revealed multiple grouped, firm, purpuric papules, nodules, and pseudovesicles on a background of violaceous erythema on the chest, abdomen, and flank (Figure 1). The background erythema had a mosaic pattern that extended toward the central back (Figure 2). A scoop shave biopsy of one of the purpuric nodules revealed highly atypical cells with abundant cytoplasm, large nuclei, and prominent nucleoli (Figure 3). Focally, the cells appeared to form glandular structures. Numerous atypical mitotic figures were present. Lymphatic invasion and microcalcifications were identified (Figure 3 [inset]). Immunohistochemical staining for cytokeratin 7 and gross cystic disease fluid protein 15 were strongly positive (Figure 4). Based on the histopathologic and immunohistochemical findings, a diagnosis of cutaneous metastatic breast adenocarcinoma was made. The patient opted to continue the homeopathic anticancer shakes and was subsequently lost to follow-up.

Cutaneous metastases of internal malignancies make up only 2% of all skin tumors,1 making them relatively uncommon in the dermatologic setting. However, cutaneous metastasis occurs in 23.9% of patients with breast carcinoma, making it the most common tumor after malignant melanoma to metastasize to the skin.2 The most common sites for breast carcinoma cutaneous metastasis (BCCM) are the chest wall and abdomen; other sites include the head/neck region and the extremities. The clinical presentation of BCCM varies depending on the mode of dissemination—lymphatic, hematogenous, contiguous growth, or iatrogenic implantation. The most common presentation is nodular carcinoma (47%–80%).2,3 Other presentations include carcinoma telangiectoides (8%–11%),2,3 alopecia neoplastica (2%–12%),2,3 and carcinoma erysipeloides (3%–6%).2,3 Carcinoma en cuirasse is rare.3

Nodular BCCM may present as firm solitary or grouped papules and nodules that are painless and range in color from flesh colored or pink to red-brown. Histologically, they are composed of atypical neoplastic cells arranged in small nests and cords, usually in a single-file line within the collagen bundles of the dermis.4 Carcinoma telangiectoides is characterized by its violaceous hue due to the dilated vascular channels. The lesions are purpuric papules and pseudovesicles appearing on an erythematous base, most commonly contiguous with the surgical scar. Histologically, collections of atypical tumor cells and erythrocytes are present along with dilated blood vessels in the papillary dermis.2 Alopecia neoplastica presents as singular or grouped cicatricial patches of hair loss. Lesions of carcinoma erysipeloides present as warm, erythematous, tender, well-defined patches or plaques. Carcinoma en cuirasse is characterized by an erythematous sclerodermoid plaque on the chest wall.2

Our patient’s presentation was unique due to the widespread distribution, unusual pattern, and variable clinical morphologies of the cutaneous metastases. Our patient had findings of both carcinoma telangiectoides and nodular carcinoma. The mosaic violaceous erythema extending toward the mid-back rarely is reported in the literature and indicates extensive intravascular spread of tumor cells in the dermis.

Metastatic breast cancer is associated with a poor prognosis because it typically occurs in advanced stages and often does not respond to treatment.5 Although chemotherapy, hormonal therapy, and/or radiation therapy may improve survival, the choice in regimen is guided by cancer histology as well as prior treatments. In our case, the patient chose to continue her homeopathic therapy.

To the Editor:

Cutaneous metastases occur more often in the setting of breast carcinoma than other malignancies in women.1 Although interventions are aimed at halting disease progression, cutaneous metastases indicate widespread disease and are associated with poor prognosis. We present the case of a patient with metastatic breast adenocarcinoma who developed cutaneous metastasis on the trunk after a double mastectomy. The widespread distribution and wide range of clinical manifestations are unique.

An 81-year-old woman presented to the dermatology office for evaluation of a skin eruption that started along a mastectomy scar on the left breast a few months postoperatively. She had a history of stage IV breast adenocarcinoma metastatic to the chest wall that was treated with a double mastectomy 2 years prior. The patient denied associated pain or pruritus and mainly was concerned with the cosmetic appearance. At the time of the initial diagnosis of breast adenocarcinoma, the patient was offered chemotherapy, which she did not tolerate. The patient opted against radiation therapy, as she preferred a more natural approach, such as anticancer shakes, which she was taking from a homeopathic source. She was unaware of the ingredients used in the shakes.

Physical examination revealed multiple grouped, firm, purpuric papules, nodules, and pseudovesicles on a background of violaceous erythema on the chest, abdomen, and flank (Figure 1). The background erythema had a mosaic pattern that extended toward the central back (Figure 2). A scoop shave biopsy of one of the purpuric nodules revealed highly atypical cells with abundant cytoplasm, large nuclei, and prominent nucleoli (Figure 3). Focally, the cells appeared to form glandular structures. Numerous atypical mitotic figures were present. Lymphatic invasion and microcalcifications were identified (Figure 3 [inset]). Immunohistochemical staining for cytokeratin 7 and gross cystic disease fluid protein 15 were strongly positive (Figure 4). Based on the histopathologic and immunohistochemical findings, a diagnosis of cutaneous metastatic breast adenocarcinoma was made. The patient opted to continue the homeopathic anticancer shakes and was subsequently lost to follow-up.

Cutaneous metastases of internal malignancies make up only 2% of all skin tumors,1 making them relatively uncommon in the dermatologic setting. However, cutaneous metastasis occurs in 23.9% of patients with breast carcinoma, making it the most common tumor after malignant melanoma to metastasize to the skin.2 The most common sites for breast carcinoma cutaneous metastasis (BCCM) are the chest wall and abdomen; other sites include the head/neck region and the extremities. The clinical presentation of BCCM varies depending on the mode of dissemination—lymphatic, hematogenous, contiguous growth, or iatrogenic implantation. The most common presentation is nodular carcinoma (47%–80%).2,3 Other presentations include carcinoma telangiectoides (8%–11%),2,3 alopecia neoplastica (2%–12%),2,3 and carcinoma erysipeloides (3%–6%).2,3 Carcinoma en cuirasse is rare.3

Nodular BCCM may present as firm solitary or grouped papules and nodules that are painless and range in color from flesh colored or pink to red-brown. Histologically, they are composed of atypical neoplastic cells arranged in small nests and cords, usually in a single-file line within the collagen bundles of the dermis.4 Carcinoma telangiectoides is characterized by its violaceous hue due to the dilated vascular channels. The lesions are purpuric papules and pseudovesicles appearing on an erythematous base, most commonly contiguous with the surgical scar. Histologically, collections of atypical tumor cells and erythrocytes are present along with dilated blood vessels in the papillary dermis.2 Alopecia neoplastica presents as singular or grouped cicatricial patches of hair loss. Lesions of carcinoma erysipeloides present as warm, erythematous, tender, well-defined patches or plaques. Carcinoma en cuirasse is characterized by an erythematous sclerodermoid plaque on the chest wall.2

Our patient’s presentation was unique due to the widespread distribution, unusual pattern, and variable clinical morphologies of the cutaneous metastases. Our patient had findings of both carcinoma telangiectoides and nodular carcinoma. The mosaic violaceous erythema extending toward the mid-back rarely is reported in the literature and indicates extensive intravascular spread of tumor cells in the dermis.

Metastatic breast cancer is associated with a poor prognosis because it typically occurs in advanced stages and often does not respond to treatment.5 Although chemotherapy, hormonal therapy, and/or radiation therapy may improve survival, the choice in regimen is guided by cancer histology as well as prior treatments. In our case, the patient chose to continue her homeopathic therapy.

- Nashan D, Meiss F, Braun-Falco M, et al. Cutaneous metastasis from internal malignancies. Dermatol Ther. 2010;23:567-580.

- De Giorgi V, Grazzini M, Alfaioli B, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of breast carcinoma. Dermatol Ther. 2010;23:581-589.

- Mordenti C, Peris K, Concetta Fargnoli M, et al. Cutaneous metastatic breast carcinoma. Acta Dermatovenerologica. 2000;9:143-148.

- Nava G, Greer K, Patterson J, et al. Metastatic cutaneous breast carcinoma: a case report and review of the literature. Can J Plast Surg. 2009;17:25-27.

- Kalmykow B, Walker S. Cutaneous metastasis in breast cancer. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2001;15:99-101.

- Nashan D, Meiss F, Braun-Falco M, et al. Cutaneous metastasis from internal malignancies. Dermatol Ther. 2010;23:567-580.

- De Giorgi V, Grazzini M, Alfaioli B, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of breast carcinoma. Dermatol Ther. 2010;23:581-589.

- Mordenti C, Peris K, Concetta Fargnoli M, et al. Cutaneous metastatic breast carcinoma. Acta Dermatovenerologica. 2000;9:143-148.

- Nava G, Greer K, Patterson J, et al. Metastatic cutaneous breast carcinoma: a case report and review of the literature. Can J Plast Surg. 2009;17:25-27.

- Kalmykow B, Walker S. Cutaneous metastasis in breast cancer. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2001;15:99-101.

Practice Points

- Breast carcinoma is one of the most common malignancies to metastasize to the skin in women.

- Although interventions are aimed at halting disease progression, cutaneous metastases indicate widespread disease and are associated with a poor prognosis.

Painless Telangiectatic Lesion on the Wrist

The Diagnosis: Merkel Cell Carcinoma

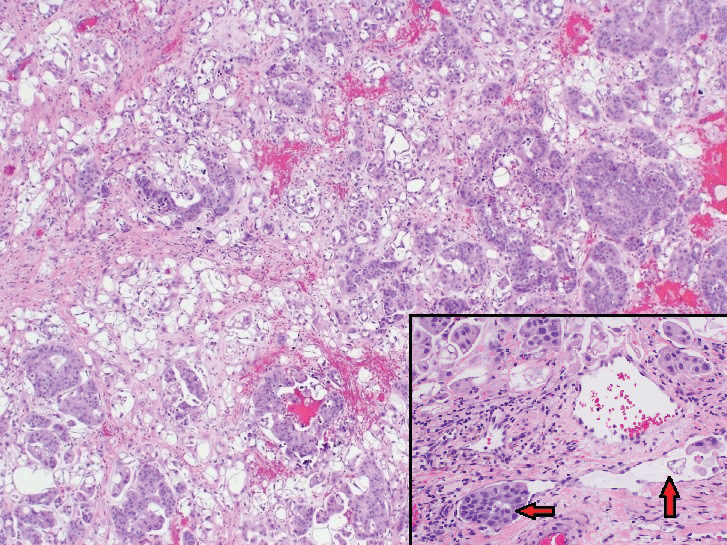

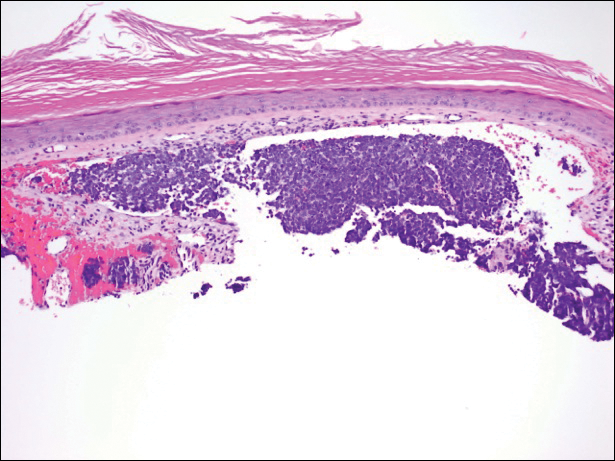

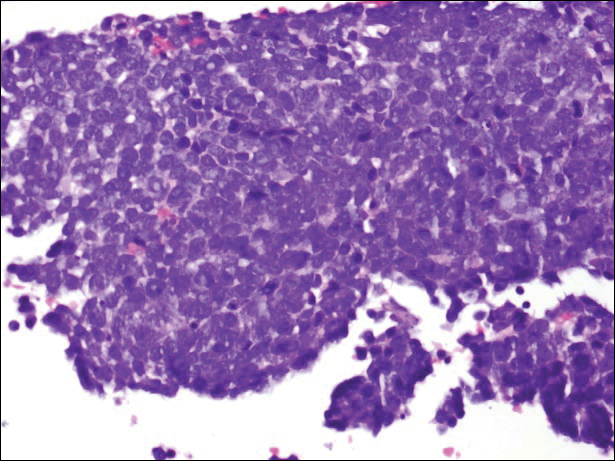

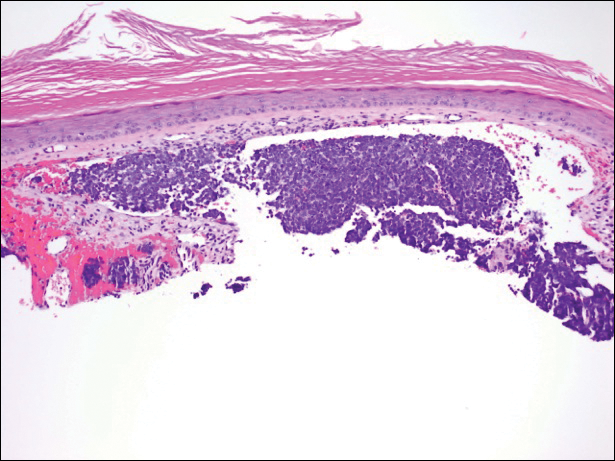

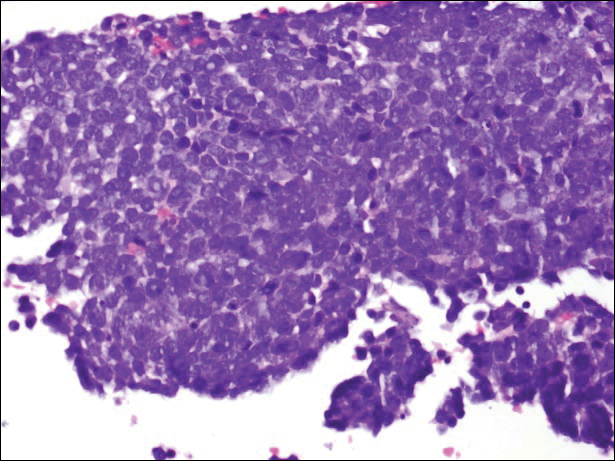

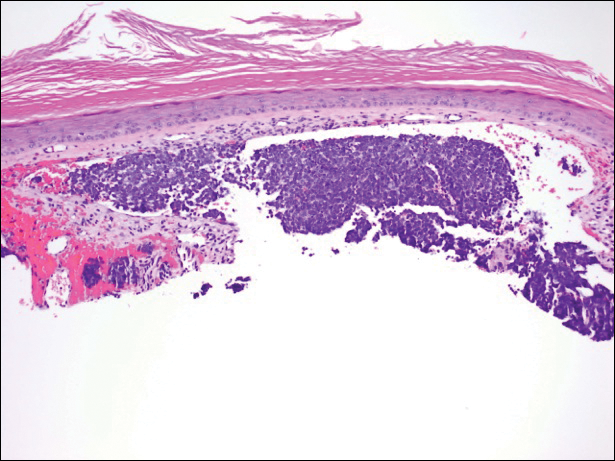

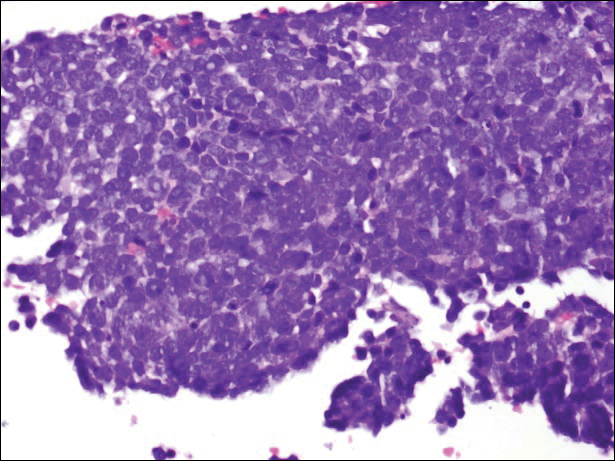

A partial biopsy was performed during the dermatology examination. Histopathology demonstrated a dense dermal infiltrate of small, dark blue, pleomorphic cells (Figure 1). On high power, the individual cells were noted to have vesicular nuclei with finely granular and dusty chromatin (Figure 2). Numerous mitotic figures were present. Immunohistochemical stains were performed and revealed positive staining for cytokeratin 20 (with a perinuclear dot pattern), synaptophysin, and chromogranin.

Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC) is an uncommon carcinoma of the epidermal neuroendocrine cells with approximately 1500 cases a year in the United States.1 Merkel cell carcinoma has a poor prognosis with approximately one-third of cases resulting in death within 5 years and with a survival rate strongly dependent on the stage of disease at presentation.2 A complete surgical excision with histologically verified clear margins is the main form of treatment of the primary cancer.3 Although the effectiveness of adjuvant therapy for MCC has been debated,4 retrospective analysis has shown that the high local recurrence rate of the primary tumor can be reduced by combining surgical excision with a form of radiation therapy.5

A systematic cohort study of 195 patients diagnosed with MCC summarized its most clinical factors with the acronym AEIOU: asymptomatic, expanding rapidly, immunosuppression, older than 50 years of age, and UV-exposed site on a fair-skinned individual.6 The role of immune function in MCC was highlighted by a 16-fold overrepresentation of immunosuppressed patients in the studied cohort as compared to the general US population. The immunosuppressed patients included individuals with human immunodeficiency virus, chronic lymphocytic leukemia, and iatrogenic suppression secondary to solid organ transplantation.6

In 2008, Merkel cell polyomavirus (MCPyV) was found in 80% (8/10) of MCC tumors tested.7 Since then, many different studies have suggested that MCPyV is an etiologic agent of MCC.8-10 A natural component of skin flora, MCPyV only becomes tumorigenic after integration into the host DNA and with mutations to the viral genome.11 Although there currently is no difference in treatment of MCPyV-positive and MCPyV-negative MCC,12 research is being done to determine how the discovery of the MCPyV could impact the treatment of MCC.

- Albores-Saavedra J, Batich K, Chable-Montero F, et al. Merkel cell carcinoma demographics, morphology, and survival based on 3870 cases: a population based study. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;37:20-27.

- Allen PJ, Bowne WB, Jaques DP, et al. Merkel cell carcinoma: prognosis and treatment of patients from a single institution. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:2300-2309.

- Eng TY, Boersma MG, Fuller CD, et al. A comprehensive review of the treatment of Merkel cell carcinoma. Am J Clin Oncol. 2007;30:624-636.

- Beenken SW, Urist MM. Treatment options for Merkel cell carcinoma. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2004;2:89-92.

- Decker RH, Wilson LD. Role of radiotherapy in the management of Merkel cell carcinoma of the skin. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2006;4:713-718.

- Heath M, Jaimes N, Lemos B, et al. Clinical characteristics of Merkel cell carcinoma at diagnosis in 195 patients: the "AEIOU" features. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:375-381.

- Feng H, Shuda M, Chang Y, et al. Clonal integration of a polyomavirus in human Merkel cell carcinoma. Science. 2008;319:1096-1100.

- Duncavage EJ, Zehnbauer BA, Pfeifer JD. Prevalence of Merkel cell polyomavirus in Merkel cell carcinoma. Mod Pathol. 2009;22:516-521.

- Sastre-Garau X, Peter M, Avril MF, et al. Merkel cell carcinoma of the skin: pathological and molecular evidence for a causative role of MCV in oncogenesis. J Pathol. 2009;218:48-56.

- Varga E, Kiss M, Szabó K, et al. Detection of Merkel cell polyomavirus DNA in Merkel cell carcinomas. Br J Dermatol. 2009;161:930-932.

- Wendzicki JA, Moore PS, Chang Y. Large T and small T antigens of Merkel cell carcinoma. Curr Opin Virol. 2015;11:38-43.

- Duprat JP, Landman G, Salvajoli JV, et al. A review of the epidemiology and treatment of Merkel cell carcinoma. Clinics (Sao Paulo). 2011;66:1817-1823.

The Diagnosis: Merkel Cell Carcinoma

A partial biopsy was performed during the dermatology examination. Histopathology demonstrated a dense dermal infiltrate of small, dark blue, pleomorphic cells (Figure 1). On high power, the individual cells were noted to have vesicular nuclei with finely granular and dusty chromatin (Figure 2). Numerous mitotic figures were present. Immunohistochemical stains were performed and revealed positive staining for cytokeratin 20 (with a perinuclear dot pattern), synaptophysin, and chromogranin.

Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC) is an uncommon carcinoma of the epidermal neuroendocrine cells with approximately 1500 cases a year in the United States.1 Merkel cell carcinoma has a poor prognosis with approximately one-third of cases resulting in death within 5 years and with a survival rate strongly dependent on the stage of disease at presentation.2 A complete surgical excision with histologically verified clear margins is the main form of treatment of the primary cancer.3 Although the effectiveness of adjuvant therapy for MCC has been debated,4 retrospective analysis has shown that the high local recurrence rate of the primary tumor can be reduced by combining surgical excision with a form of radiation therapy.5

A systematic cohort study of 195 patients diagnosed with MCC summarized its most clinical factors with the acronym AEIOU: asymptomatic, expanding rapidly, immunosuppression, older than 50 years of age, and UV-exposed site on a fair-skinned individual.6 The role of immune function in MCC was highlighted by a 16-fold overrepresentation of immunosuppressed patients in the studied cohort as compared to the general US population. The immunosuppressed patients included individuals with human immunodeficiency virus, chronic lymphocytic leukemia, and iatrogenic suppression secondary to solid organ transplantation.6

In 2008, Merkel cell polyomavirus (MCPyV) was found in 80% (8/10) of MCC tumors tested.7 Since then, many different studies have suggested that MCPyV is an etiologic agent of MCC.8-10 A natural component of skin flora, MCPyV only becomes tumorigenic after integration into the host DNA and with mutations to the viral genome.11 Although there currently is no difference in treatment of MCPyV-positive and MCPyV-negative MCC,12 research is being done to determine how the discovery of the MCPyV could impact the treatment of MCC.

The Diagnosis: Merkel Cell Carcinoma

A partial biopsy was performed during the dermatology examination. Histopathology demonstrated a dense dermal infiltrate of small, dark blue, pleomorphic cells (Figure 1). On high power, the individual cells were noted to have vesicular nuclei with finely granular and dusty chromatin (Figure 2). Numerous mitotic figures were present. Immunohistochemical stains were performed and revealed positive staining for cytokeratin 20 (with a perinuclear dot pattern), synaptophysin, and chromogranin.

Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC) is an uncommon carcinoma of the epidermal neuroendocrine cells with approximately 1500 cases a year in the United States.1 Merkel cell carcinoma has a poor prognosis with approximately one-third of cases resulting in death within 5 years and with a survival rate strongly dependent on the stage of disease at presentation.2 A complete surgical excision with histologically verified clear margins is the main form of treatment of the primary cancer.3 Although the effectiveness of adjuvant therapy for MCC has been debated,4 retrospective analysis has shown that the high local recurrence rate of the primary tumor can be reduced by combining surgical excision with a form of radiation therapy.5

A systematic cohort study of 195 patients diagnosed with MCC summarized its most clinical factors with the acronym AEIOU: asymptomatic, expanding rapidly, immunosuppression, older than 50 years of age, and UV-exposed site on a fair-skinned individual.6 The role of immune function in MCC was highlighted by a 16-fold overrepresentation of immunosuppressed patients in the studied cohort as compared to the general US population. The immunosuppressed patients included individuals with human immunodeficiency virus, chronic lymphocytic leukemia, and iatrogenic suppression secondary to solid organ transplantation.6

In 2008, Merkel cell polyomavirus (MCPyV) was found in 80% (8/10) of MCC tumors tested.7 Since then, many different studies have suggested that MCPyV is an etiologic agent of MCC.8-10 A natural component of skin flora, MCPyV only becomes tumorigenic after integration into the host DNA and with mutations to the viral genome.11 Although there currently is no difference in treatment of MCPyV-positive and MCPyV-negative MCC,12 research is being done to determine how the discovery of the MCPyV could impact the treatment of MCC.

- Albores-Saavedra J, Batich K, Chable-Montero F, et al. Merkel cell carcinoma demographics, morphology, and survival based on 3870 cases: a population based study. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;37:20-27.

- Allen PJ, Bowne WB, Jaques DP, et al. Merkel cell carcinoma: prognosis and treatment of patients from a single institution. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:2300-2309.

- Eng TY, Boersma MG, Fuller CD, et al. A comprehensive review of the treatment of Merkel cell carcinoma. Am J Clin Oncol. 2007;30:624-636.

- Beenken SW, Urist MM. Treatment options for Merkel cell carcinoma. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2004;2:89-92.

- Decker RH, Wilson LD. Role of radiotherapy in the management of Merkel cell carcinoma of the skin. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2006;4:713-718.

- Heath M, Jaimes N, Lemos B, et al. Clinical characteristics of Merkel cell carcinoma at diagnosis in 195 patients: the "AEIOU" features. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:375-381.

- Feng H, Shuda M, Chang Y, et al. Clonal integration of a polyomavirus in human Merkel cell carcinoma. Science. 2008;319:1096-1100.

- Duncavage EJ, Zehnbauer BA, Pfeifer JD. Prevalence of Merkel cell polyomavirus in Merkel cell carcinoma. Mod Pathol. 2009;22:516-521.

- Sastre-Garau X, Peter M, Avril MF, et al. Merkel cell carcinoma of the skin: pathological and molecular evidence for a causative role of MCV in oncogenesis. J Pathol. 2009;218:48-56.

- Varga E, Kiss M, Szabó K, et al. Detection of Merkel cell polyomavirus DNA in Merkel cell carcinomas. Br J Dermatol. 2009;161:930-932.

- Wendzicki JA, Moore PS, Chang Y. Large T and small T antigens of Merkel cell carcinoma. Curr Opin Virol. 2015;11:38-43.

- Duprat JP, Landman G, Salvajoli JV, et al. A review of the epidemiology and treatment of Merkel cell carcinoma. Clinics (Sao Paulo). 2011;66:1817-1823.

- Albores-Saavedra J, Batich K, Chable-Montero F, et al. Merkel cell carcinoma demographics, morphology, and survival based on 3870 cases: a population based study. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;37:20-27.

- Allen PJ, Bowne WB, Jaques DP, et al. Merkel cell carcinoma: prognosis and treatment of patients from a single institution. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:2300-2309.

- Eng TY, Boersma MG, Fuller CD, et al. A comprehensive review of the treatment of Merkel cell carcinoma. Am J Clin Oncol. 2007;30:624-636.

- Beenken SW, Urist MM. Treatment options for Merkel cell carcinoma. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2004;2:89-92.

- Decker RH, Wilson LD. Role of radiotherapy in the management of Merkel cell carcinoma of the skin. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2006;4:713-718.

- Heath M, Jaimes N, Lemos B, et al. Clinical characteristics of Merkel cell carcinoma at diagnosis in 195 patients: the "AEIOU" features. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:375-381.

- Feng H, Shuda M, Chang Y, et al. Clonal integration of a polyomavirus in human Merkel cell carcinoma. Science. 2008;319:1096-1100.

- Duncavage EJ, Zehnbauer BA, Pfeifer JD. Prevalence of Merkel cell polyomavirus in Merkel cell carcinoma. Mod Pathol. 2009;22:516-521.

- Sastre-Garau X, Peter M, Avril MF, et al. Merkel cell carcinoma of the skin: pathological and molecular evidence for a causative role of MCV in oncogenesis. J Pathol. 2009;218:48-56.

- Varga E, Kiss M, Szabó K, et al. Detection of Merkel cell polyomavirus DNA in Merkel cell carcinomas. Br J Dermatol. 2009;161:930-932.

- Wendzicki JA, Moore PS, Chang Y. Large T and small T antigens of Merkel cell carcinoma. Curr Opin Virol. 2015;11:38-43.

- Duprat JP, Landman G, Salvajoli JV, et al. A review of the epidemiology and treatment of Merkel cell carcinoma. Clinics (Sao Paulo). 2011;66:1817-1823.

A 91-year-old white man with a history of atrial fibrillation, benign prostatic hyperplasia, dysphagia, gastroesophageal reflux disease, hypertension, hypothyroidism, osteoarthritis, and laryngeal cancer presented with an 8-mm firm, painless, pink lesion with telangiectasia on the left wrist. The lesion had been present for an unknown period of time and was asymptomatic at presentation.