User login

Differentiating bipolar disorder from depression in primary care

Rapid-cycling bipolar disorder: Which therapies are most effective?

Patients with rapid-cycling bipolar disorder (RCBD) can be frustrating to treat. Despite growing research and data, knowledge and effective therapies remain limited. How do you manage patients with rapid cycling who do not respond robustly to lithium, divalproex, or carbamazepine monotherapy? Are combination therapies likely to be more effective? Where does lamotrigine fit in? Is there a role for conventional antidepressants?

We’ll explore these and related questions—but the final answers are not yet in. Recognition of RCBD is important because it presents such difficult treatment challenges. Available evidence does suggest that rapid cycling as defined in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition (Box 1), describes a clinically specific course of illness that may require treatments different from currently used traditional drug therapies for nonrapid cycling bipolar disorder, particularly as no one agent appears to provide ideal bimodal treatment and prophylaxis of this bipolar disorder variant.

Rapid cycling is a specifier of the longitudinal course of illness presentation that is seen almost exclusively in bipolar disorder and is associated with a greater morbidity. Dunner and Fieve1 originally coined the term when evaluating clinical factors associated with lithium prophylaxis failure. Since that time the validity of rapid cycling as a distinct course modifier for bipolar disorder has been supported by multiple studies, leading to its inclusion in the fourth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of the APA (1994).

According to DSM-IV, the course specifier of rapid cycling applies to “at least 4 episodes of a mood disturbance in the previous 12 months that meet criteria for a manic episode, a hypomanic episode, or a major depressive episode.” The episodes must be demarcated by a full or partial remission lasting at least 2 months or by a switch to a mood state of opposite polarity.

Early reports noted that patients suffering from RCBD did not respond adequately when treated with lithium.1 Other observations indicated that divalproex was more effective in this patient population, particularly for the illness’ hypomanic or manic phases.2 We hope that the following evaluation of these and other drug therapies will prove helpful.

Watch out for antidepressants

Most concerning has been the frequency and severity of treatment-refractory depressive phases of RCBD that may be exacerbated by antidepressant use (cycle induction or acceleration). Indeed, the frequent recurrence of refractory depression has been described as the hallmark of this bipolar disorder variant.3

Lithium: the scale weighs against it

Although an excellent mood stabilizer for most patients with bipolar disorder, lithium monotherapy is less than ideal for patients with the rapid-cycling variant, particularly in treatment or prevention of depressive or mixed episodes. The efficacy of lithium is likely decreased by the concurrent administration of antidepressant medication and increased when administered with other mood stabilizers.

The landmark article by Dunner and Fieve,1 which described a placebo-controlled, double-blind maintenance study in a general cohort of 55 patients, tried to clarify factors associated with the failure of lithium prophylaxis in bipolar disorder. Rapid cyclers comprised 20% of the subjects and 80% were nonrapid cyclers. Rapid cyclers were disproportionately represented in the lithium failure group. Lithium failures included 82% (9 of 11) of rapid cyclers compared to 41% (18 of 44) of nonrapid cyclers. Lithium failure was defined as (1) hospitalization for, or (2) treatment of, mania or (3) depression during lithium therapy, or as mood symptoms that, as documented by rating scales, were sufficient to warrant a diagnosis of mild depression, hypomania, or mania persisting for at least 2 weeks.

Kukopulos et al4 replicated the findings of Dunner and Fieve in a study of the longitudinal clinical course of 434 bipolar patients. Of these patients, 50 were rapid cyclers and had received continuous lithium therapy for more than a year, with good to partial prophylaxis in only 28%. Maj and colleagues5 published a 5-year prospective study of lithium therapy in 402 patients with bipolar disorder and noted the absence of rapid cycling in good responders to lithium but an incidence rate of 26% in nonresponders to lithium.

Other investigators have reported better response in RCBD. In a select cohort of lithium-responsive bipolar I and II patients, Tondo et al6 concluded that lithium maintenance yields striking long-term reductions in depressive and manic morbidity, more so in rapid cycling type II patients. This study, however, was in a cohort of lithium responders and excluded patients who had been exposed to antipsychotic or antidepressant medications for more than 3 months, those on chronic anticonvulsant therapy, and those with substance abuse disorders.

Although most studies do report poor response to lithium therapy in RCBD, Wehr and colleagues7 suggest that in some patients with rapid cycling, the discontinuation of antidepressant drugs may allow lithium to act as a more effective anticycling mood-stabilizing agent.

Divalproex: effective in manic phase

In contrast to lithium, an open trial of a homogenous cohort of patients with RCBD by Calabrese and colleagues3,8 found divalproex to possess moderate to marked acute and prophylactic antimanic properties with only modest antidepressant effects (Table 1). Data from 6 open studies involving 147 patients with rapid cycling suggest that divalproex possesses moderate to marked efficacy in the manic phase, but poor to moderate efficacy in the depressed phase. Positive outcome predictors were bipolar II and mixed states, no prior lithium therapy, and a positive family history of affective disorder. Predictors of negative response included increase in frequency and severity of mania, and borderline personality disorder.

Divalproex therapy in combination with lithium may improve response rates.9 Calabrese and colleagues, however, have examined large cohorts of patients, including those comorbid with alcohol, cocaine, and/or cannabis abuse, treated with a lithium-divalproex combination over 6-month study periods. The researchers found that only 25% to 50% of patients stabilized, and that of those not exhibiting a response, the majority (75%) did not respond because of treatment-refractory depression in the context of RCBD.3

Although experts believe divalproex to be more effective than lithium in preventing episodes associated with RCBD, such a conclusion awaits confirmation with the near completion of a double-blind, 20-month maintenance trial sponsored by the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH).

Carbamazepine’s role in combination therapy

Early reports by Post and colleagues in 1987 suggested that rapid cycling predicted positive response to carbamazepine, but later findings by Okuma in 1993 refuted this. Other collective open and controlled studies suggest that this anticonvulsant possesses moderate to marked efficacy in the manic phase, and poor to moderate efficacy in the depressed phase of RCBD. Again, combination therapy with lithium may offer greater efficacy. Of significance, carbamazepine treatment outcomes have not been prospectively evaluated in a homogeneous cohort of rapid cyclers.

The limitations of carbamazepine therapy are well known and available evidence also does not seem to support monotherapy with this agent as being useful in RCBD, especially in the treatment and prophylaxis of depressive or mixed phases of the disorder. Thus, further controlled studies are needed to examine the agent’s potential role and safety in combination therapies for RCBD.

Table 1

SPECTRUM OF ACUTE AND PROPHYLACTIC EFFICACY OF DIVALPROEX IN RAPID-CYCLING BIPOLAR DISORDER

| Spectrum of marked responses to divalproex in bipolar rapid cycling | ||

|---|---|---|

| Acute | Prophylactic | |

| Dysphoric hypomania/mania | 87% | 89% |

| Elated hypomania/mania | 64% | 77% |

| Depression (n = 101, mean follow-up 15 months) | 21% | 38% |

| Adapted from Calabrese and Delucchi. Am J Psychiatry. 1990;147:431-434 and Calabrese et al. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1993;13:280-283. | ||

Lamotrigine: best hope for monotherapy

Lamotrigine monotherapy has been reported to be effective in some RCBD cases. The data suggest that it possesses both antidepressant and mood-stabilizing properties.10

An open, naturalistic study of 5 women with treatment-refractory rapid cycling by Fatemi et al11 demonstrated both mood-stabilizing and antidepressant effects from lamotrigine monotherapy or augmentation at a mean dose of 185 ±33.5 mg/d. In 14 clinical reports involving 207 patients with bipolar disorder, 66 of whom had rapid cycling, lamotrigine was observed to possess moderate to marked efficacy in depression and hypomania, but only moderate efficacy in mania.

An open, prospective study compared the efficacy of lamotrigine add-on or monotherapy in 41 rapid cyclers to 34 nonrapid cyclers across 48 weeks. Improvement from baseline to last visit was significant between both subgroups for depressive and hypomanic symptoms. Patients presenting with more severe manic symptoms did less well.13

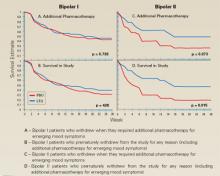

In the first double-blind, placebo-controlled study of lamotrigine in RCBD,12 182 of 324 patients with rapid cycling responded to treatment with open-label lamotrigine and were then randomized to the study’s double-blind phase. Forty-one percent of lamotrigine-treated vs. 26% of placebo-treated patients were stable without relapse during 6 months of monotherapy. Patients with rapid-cycling bipolar II disorder consistently experienced more improvement than their bipolar I counterparts (Figure 1). The results of this only prospective, placebo-controlled, acute-treatment study of rapid-cycling bipolar patients to date indicate that lamotrigine monotherapy is useful for some patients with RCBD, particularly those with bipolar II.

Frye et al14 conducted a double-blind, placebo-controlled study of 23 patients with rapid cycling utilizing a crossover series of three 6-week monotherapy evaluations of lamotrigine, gabapentin, and placebo. Marked antidepressant response on lamotrigine was seen in 45% of the participants compared with 19% of patients on placebo and a similar response rate among those on gabapentin.

A study evaluating the safety and efficacy of 2 dosages of lamotrigine (50 mg/d or 200 mg/d) compared with placebo in the treatment of a major depressive episode in patients with bipolar I disorder over 7 weeks demonstrated significant antidepressant efficacy.15 These bipolar outpatients displayed clinical improvement as early as the third week of treatment, and switch rates for both dosages did not exceed that of placebo. Patients with RCBD, however, were excluded from this initial trial. Subsequent studies have demonstrated similar magnitudes of efficacy in patients with RCBD, primarily in the prevention of depressive episodes, including the 6-month RCBD maintenance study10 and 2 recently completed 18-month maintenance studies of patients with bipolar I disorder, either recently manic or recently depressed.

Lamotrigine thus may have a special role in RCBD treatment. Its most significant side effect in bipolar disorder is benign rash, which has occurred in 9.0% (108 of 1,198) of patients randomized to lamotrigine vs. 7.6% (80 of 1,056) of those randomized to placebo in pivotal multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled bipolar trials.

In mood disorder trials conducted to date, the rate of serious rash, defined as requiring both drug discontinuation and hospitalization, has been 0.06% (2 of 3,153) on lamotrigine and 0.09% (1 out of 1,053) on placebo. No cases of Steven’s Johnson syndrome or toxic epidermal necrolysis were observed.16 A low starting dose and gradual titration of lamotrigine (Table 2) appear to minimize the risk of serious rash.

Levothyroxine: possible add-on therapy

Levothyroxine should be considered as add-on therapy in patients with known hypothyroidism, borderline hypothyroidism, or otherwise treatment-refractory cases.

The strategy of thyroid supplementation is derived from Gjessing’s 1936 report of success in administering hypermetabolic doses of thyroid hormone to patients with periodic catatonia. Stancer and Persad17 initially reported the potential efficacy of this therapeutic maneuver in rapid cyclers; remissions were induced by hypermetabolic thyroid doses in 5 of 7 patients with treatment-refractory bipolar disorder. No data currently support any prophylactic efficacy of thyroid supplementation monotherapy for RCBD treatment.

Bauer and Whybrow18 suggest that thyroid supplementation with T4 added to mood stabilizers augments efficacy independent of pre-existing thyroid function. The potential side effects of long-term levothryoxine administration, namely osteoporosis and cardiac arrhythmias, limit the usefulness of thyroid augmentation in RCBD.

Atypical antipsychotics: perhaps in combination

Coadministering atypical antipsychotics in other mood stabilizers may help rapid cyclers with current or past psychotic symptoms during their mood episodes, but further study is clearly needed.

Atypical antipsychotic medications may have specific mood-stabilizing properties, particularly in the management of mixed and manic states. In the first prospective trial of clozapine monotherapy in bipolar disorder, Calabrese and colleagues in 1994 reported that rapid cycling did not appear to predict nonresponse to treatment.

In the first randomized, controlled trial involving clozapine in bipolar disorder, Suppes et al19 noted significant improvement for symptoms of mania, psychosis, and global improvement. Subjects with nonpsychotic bipolar disorder showed a degree of improvement similar to that seen in the entire clozapine-treated group. These results support a mood-stabilizing role for clozapine.

Preliminary studies of risperidone and olanzapine further suggest therapeutic utility for atypical antipsychotics.

Figure 1 LAMOTRIGINE VS. PLACEBO IN RAPID-CYCLING BIPOLAR DISORDER

Table 2

DOSAGE PLAN FOR LAMOTRIGINE IN MONOTHERAPY AND COMBINATION

| Treatment period | Type of therapy | Daily dosage |

|---|---|---|

| Weeks 1-2 | Monotherapy With divalproex With carbamazepine | 25 mg 12.5 mg 50 mg |

| Weeks 3-4 | Monotherapy With divalproex With carbamazepine | 50 mg 25 mg 100 mg |

| Week 5 | Monotherapy With divalproex With carbamazepine | 100 mg 50 mg 200 mg |

| Thereafter | Monotherapy With divalproex With carbamazepine | 200 mg 100 mg 400 mg |

Topiramate: in patients with weight problems

Evidence from 12 open studies of 223 patients with bipolar disorder suggest that this anticonvulsant may possess mood-stabilizing properties while sparing patients the weight gain commonly seen with other pharmacotherapies.

Two studies of topiramate as an add-on therapy come to mind. Marcotte in 1998 retrospectively studied 44 patients with RCBD, 23 (52%) of whom demonstrated moderate or marked improvement on a mean topiramate dosage of 200 mg/d.

Sachs also reported that symptoms for some patients with a treatment-refractory bipolar disorder could be improved when topiramate was added to their medication regimen. Available data encourage further controlled studies of topiramate add-on therapy for RCBD, especially in obese patients.

Gabapentin: contradictory reports

Preliminary data from 14 open-label studies of gabapentin in 302 bipolar patients reported a response rate of around 67% when used as an add-on therapy, usually in mania or mixed states. A moderate antimanic effect was observed among a total of 23 rapid cyclers in 9 of the studies.

The reports are contradictory, however, and available data do not firmly support the agent’s efficacy in RCBD treatment.

Other potential uses for gabapentin are being investigated, such as antidepressant augmentation, anxiety, and chronic pain. Thus, patients with RCBD and a comorbid illness may benefit from add-on gabapentin.

ECT: Some limited success

Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) has been implicated less frequently than antidepressants in the induction of rapid cycling, and when this does occur it is usually in the context of combined ECT/antidepressant therapies.

Berma and Wolpert in 1987 reported a case of successful ECT treatment of rapid cycling in an adolescent who had been treated with trimipramine for depression. Vanelle et al in 1994 suggested that maintenance ECT works well in 22 treatment-resistant bipolar patients, including 4 with rapid cycling, over an 18-month treatment period.

Behavioral intervention: changing sleep routines

NIMH research of 15 rapid cyclers who were studied for 3 months looked at behavioral interventions and their effect on switching (Feldman-Naim 1997). This study suggested that patients were more likely to switch from depression into hypomania/mania during daytime hours and from mania/hypomania into depression during nighttime.

The use of light therapy or activity and exercise during depression and the use of induced sleep or exposure to darkness during mania/hypomania may be therapeutic. Wehr and colleagues supported this in a 1998 report of one patient studied over several years, comparing this rapid-cycling patient’s regular sleep routine with prolonged (10 to 14 hours per night) and enforced bed rest in the dark.7 The promotion of sleep by scheduling regular nighttime periods of enforced bed rest in the dark may help prevent mania and stabilize mood in rapid cyclers.

Other add-on possibilities

Haykal in 1990 reported bupropion to be an effective add-on treatment in 5 of 6 patients with refractory, rapid-cycling bipolar II disorder. Benefit has also been reported from clorgyline, clonidine, magnesium, primidone, and acetazolamide.

Calcium-channel blockers may also offer clinical utility, although supportive evidence is limited. Nimodipine was evaluated for efficacy in 30 patients with treatment-refractory affective illness by the NIMH and Passaglia et al in 1998. Patients who improved on this agent had ultradian rapid cycling, defined in the study as those with affective episodes lasting as short as a week.

A recommended treatment strategy

Based on the available data in bipolar I rapid cycling, we recommend initial treatment with divalproex followed by augmentation with lithium if hypomanic or manic episodes persist, lamotrigine if breakthrough episodes are predominantly depressive, and atypical antipsychotics if psychotic symptoms or true mixed states remain.

For patients presenting with bipolar II rapid cycling, we recommend starting with lamotrigine, then augmenting with divalproex or lithium for breakthrough episodes. Lamotrigine shows more promise because of its reportedly greater antidepressant properties and lack of cycle induction or switching, but offers only modest antimanic therapy.

Pending further investigations, current application of the data suggests that when treating patients with RCBD, conventional antidepressants should be avoided and, if first-line therapies are not effective, the clinician should consider moving to combination drug therapy with 2 or more agents.

Related resources

- Bauer MS, Calabrese JR, Dunner DL, et al. Multi-site data reanalysis: validity of rapid cycling as a course modifier for bipolar disorder in DSM-IV. Am J Psychiatry. 1994;151:506-515.

- Calabrese JR, Kimmel SE, Woyshville MJ, et al. Clozapine in treatment refractory mania. Am J Psychiatry. 1996;153(6):759-764.

- Calabrese JR, Bowden CL, McElroy SL, et al. Spectrum of activity of lamotrigine in treatment refractory bipolar disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156(7):1019-1023.

- Sachs GS. Printz DJ. Kahn DA. Carpenter D. Docherty JP. The expert consensus guideline series: medication treatment of bipolar disorder 2000. Postgraduate Medicine. April 2000; Spec No:1-104.

Drug brand names

- Buproprion • Wellbutrin

- Carbamazepine • Tegretol

- Clonidine • Catapres

- Clozapine • Clozaril

- Divalproex sodium • Depakote

- Gabapentin • Neurontin

- Lamotrigine • Lamictal

- Levothyroxine • Synthroid, Levothroid, Levoxyl

- Olanzapine • Zyprexa

- Nimodipine • Nimotop

- Primidonem • Mysoline

- Topiramate • Topamax

Disclosure

Dr. Muzina reports that he is a member of the Eli Lilly and Co. speaker’s bureau.

Dr. Calabrese reports that he receives research/grant support from Abbott Laboratories, GlaxoSmithKline, and Wyeth-Ayerst Pharmaceuticals, and serves as a consultant to Abbott Pharmaceuticals, Eli Lilly and Co., GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corp., and Parke Davis/Warner Lambert.

1. Dunner DL, Fieve RR. Clinical factors in lithium carbonate prophylaxis failure. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1974;20:229-233.

2. Calabrese JR, Delucchi GA. Spectrum of efficacy of valproate in 55 rapid-cycling manic depressives. Am J Psychiatry. 1990;147(4):431-434.

3. Calabrese JR, Shelton MD, Bowden CL, et al. Bipolar rapid cycling: Focus on depression as its hallmark. J Clin Psychiatry. 2001;62(Suppl 14):34-41.

4. Kukopulos A, Reginaldi D, Laddomada P, et al. Course of the manic depressive cycle and changes caused by treatment. Pharmacopsychiatry. 1980;13:156-167.

5. Maj M, et al. Long-term outcome of lithium prophylaxis in bipolar disorder: a 5-year prospective study of 402 patients at a lithium clinic. Am J Psychiatry. 1998;155:30-35.

6. Tondo L, Baldessarini RJ, et al. Lithium maintenance treatment of depression and mania in bipolar I and bipolar II disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 1998;155:638-645.

7. Wehr TA, Sack DA, Rosenthal NE, et al. Rapid cycling affective disorder: contributing factors and treatment responses in 51 patients. Am J Psychiatry. 1988;145:179-84.

8. Calabrese JR, Woyshville MJ, Kimmel SE. Rapport DJ: Predictors of valproate response in bipolar rapid cycling. J Clin Psychopharmacology. 1993;13(4):280-283.

9. Sharma V, Persad E, et al. Treatment of rapid cycling bipolar disorder with combination therapy of valproate and lithium. Can J Psychiatry. 1993;38:137-139.

10. Calabrese JR, Suppes T, Bowden CL, et al. for the Lamictal 614 Study Group. A double-blind, placebo-controlled, prophylaxis study of lamotrigine in rapid cycling bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2000;61(11):841-850.

11. Fatemi SH, Rapport DJ, Calabrese JR, et al. Lamotrigine in rapid cycling bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 1997;58:522-527.

12. Calabrese JR, Bowden CL, et al. for the Lamictal 602 Study Group. A double-blind placebo-controlled study of lamotrigine monotherapy in outpatients with bipolar I depression. Lamictal 602 Study Group. J Clin Psychiatry 1999;60(2):79-88.

13. Bowden CL, Calabrese JR, McElroy SL, et al. Comparison of the efficacy of lamotrigine in rapid cycling and non-rapid cycling bipolar disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 1999;45(8):953-958.

14. Frye MA, et al. A placebo-controlled study of lamotrigine and gabapentin monotherapy in refractory mood disorders. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2000;20:607-614.

15. Calabrese JR, Bowden CL, Sachs GS, et al. A double-blind placebo-controlled study of lamotrigine monotherapy in outpatients with bipolar I depression. Lamictal 602 Study Group. J Clin Psychiatry. 1999;60(2):79-88.

16. Calabrese JR, Bowden CL, DeVeaugh-Geiss J, et al. Lamotrigine demonstrates long term mood stabilization in recently manic patients. Annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association, New Orleans, 2001.

17. Stancer HC, Persad E. Treatment of intractable rapid-cycling manic-depressive disorder with levothyroxine. Clinical observations. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1982;39(3):311-312.

18. Bauer MS, Whybrow PC. Rapid cycling bipolar affective disorder. II. Treatment of refractory rapid cycling with high-dose levothyroxine: a preliminary study.. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1990;47(5):435-40.

19. Suppes T, Webb A, Paul B, Carmody T, et al:. Clinical outcome in a randomized 1-year trial of clozapine versus treatment as usual for patients with treatment-resistant illness and a history of mania. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156:1164-1169.

Patients with rapid-cycling bipolar disorder (RCBD) can be frustrating to treat. Despite growing research and data, knowledge and effective therapies remain limited. How do you manage patients with rapid cycling who do not respond robustly to lithium, divalproex, or carbamazepine monotherapy? Are combination therapies likely to be more effective? Where does lamotrigine fit in? Is there a role for conventional antidepressants?

We’ll explore these and related questions—but the final answers are not yet in. Recognition of RCBD is important because it presents such difficult treatment challenges. Available evidence does suggest that rapid cycling as defined in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition (Box 1), describes a clinically specific course of illness that may require treatments different from currently used traditional drug therapies for nonrapid cycling bipolar disorder, particularly as no one agent appears to provide ideal bimodal treatment and prophylaxis of this bipolar disorder variant.

Rapid cycling is a specifier of the longitudinal course of illness presentation that is seen almost exclusively in bipolar disorder and is associated with a greater morbidity. Dunner and Fieve1 originally coined the term when evaluating clinical factors associated with lithium prophylaxis failure. Since that time the validity of rapid cycling as a distinct course modifier for bipolar disorder has been supported by multiple studies, leading to its inclusion in the fourth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of the APA (1994).

According to DSM-IV, the course specifier of rapid cycling applies to “at least 4 episodes of a mood disturbance in the previous 12 months that meet criteria for a manic episode, a hypomanic episode, or a major depressive episode.” The episodes must be demarcated by a full or partial remission lasting at least 2 months or by a switch to a mood state of opposite polarity.

Early reports noted that patients suffering from RCBD did not respond adequately when treated with lithium.1 Other observations indicated that divalproex was more effective in this patient population, particularly for the illness’ hypomanic or manic phases.2 We hope that the following evaluation of these and other drug therapies will prove helpful.

Watch out for antidepressants

Most concerning has been the frequency and severity of treatment-refractory depressive phases of RCBD that may be exacerbated by antidepressant use (cycle induction or acceleration). Indeed, the frequent recurrence of refractory depression has been described as the hallmark of this bipolar disorder variant.3

Lithium: the scale weighs against it

Although an excellent mood stabilizer for most patients with bipolar disorder, lithium monotherapy is less than ideal for patients with the rapid-cycling variant, particularly in treatment or prevention of depressive or mixed episodes. The efficacy of lithium is likely decreased by the concurrent administration of antidepressant medication and increased when administered with other mood stabilizers.

The landmark article by Dunner and Fieve,1 which described a placebo-controlled, double-blind maintenance study in a general cohort of 55 patients, tried to clarify factors associated with the failure of lithium prophylaxis in bipolar disorder. Rapid cyclers comprised 20% of the subjects and 80% were nonrapid cyclers. Rapid cyclers were disproportionately represented in the lithium failure group. Lithium failures included 82% (9 of 11) of rapid cyclers compared to 41% (18 of 44) of nonrapid cyclers. Lithium failure was defined as (1) hospitalization for, or (2) treatment of, mania or (3) depression during lithium therapy, or as mood symptoms that, as documented by rating scales, were sufficient to warrant a diagnosis of mild depression, hypomania, or mania persisting for at least 2 weeks.

Kukopulos et al4 replicated the findings of Dunner and Fieve in a study of the longitudinal clinical course of 434 bipolar patients. Of these patients, 50 were rapid cyclers and had received continuous lithium therapy for more than a year, with good to partial prophylaxis in only 28%. Maj and colleagues5 published a 5-year prospective study of lithium therapy in 402 patients with bipolar disorder and noted the absence of rapid cycling in good responders to lithium but an incidence rate of 26% in nonresponders to lithium.

Other investigators have reported better response in RCBD. In a select cohort of lithium-responsive bipolar I and II patients, Tondo et al6 concluded that lithium maintenance yields striking long-term reductions in depressive and manic morbidity, more so in rapid cycling type II patients. This study, however, was in a cohort of lithium responders and excluded patients who had been exposed to antipsychotic or antidepressant medications for more than 3 months, those on chronic anticonvulsant therapy, and those with substance abuse disorders.

Although most studies do report poor response to lithium therapy in RCBD, Wehr and colleagues7 suggest that in some patients with rapid cycling, the discontinuation of antidepressant drugs may allow lithium to act as a more effective anticycling mood-stabilizing agent.

Divalproex: effective in manic phase

In contrast to lithium, an open trial of a homogenous cohort of patients with RCBD by Calabrese and colleagues3,8 found divalproex to possess moderate to marked acute and prophylactic antimanic properties with only modest antidepressant effects (Table 1). Data from 6 open studies involving 147 patients with rapid cycling suggest that divalproex possesses moderate to marked efficacy in the manic phase, but poor to moderate efficacy in the depressed phase. Positive outcome predictors were bipolar II and mixed states, no prior lithium therapy, and a positive family history of affective disorder. Predictors of negative response included increase in frequency and severity of mania, and borderline personality disorder.

Divalproex therapy in combination with lithium may improve response rates.9 Calabrese and colleagues, however, have examined large cohorts of patients, including those comorbid with alcohol, cocaine, and/or cannabis abuse, treated with a lithium-divalproex combination over 6-month study periods. The researchers found that only 25% to 50% of patients stabilized, and that of those not exhibiting a response, the majority (75%) did not respond because of treatment-refractory depression in the context of RCBD.3

Although experts believe divalproex to be more effective than lithium in preventing episodes associated with RCBD, such a conclusion awaits confirmation with the near completion of a double-blind, 20-month maintenance trial sponsored by the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH).

Carbamazepine’s role in combination therapy

Early reports by Post and colleagues in 1987 suggested that rapid cycling predicted positive response to carbamazepine, but later findings by Okuma in 1993 refuted this. Other collective open and controlled studies suggest that this anticonvulsant possesses moderate to marked efficacy in the manic phase, and poor to moderate efficacy in the depressed phase of RCBD. Again, combination therapy with lithium may offer greater efficacy. Of significance, carbamazepine treatment outcomes have not been prospectively evaluated in a homogeneous cohort of rapid cyclers.

The limitations of carbamazepine therapy are well known and available evidence also does not seem to support monotherapy with this agent as being useful in RCBD, especially in the treatment and prophylaxis of depressive or mixed phases of the disorder. Thus, further controlled studies are needed to examine the agent’s potential role and safety in combination therapies for RCBD.

Table 1

SPECTRUM OF ACUTE AND PROPHYLACTIC EFFICACY OF DIVALPROEX IN RAPID-CYCLING BIPOLAR DISORDER

| Spectrum of marked responses to divalproex in bipolar rapid cycling | ||

|---|---|---|

| Acute | Prophylactic | |

| Dysphoric hypomania/mania | 87% | 89% |

| Elated hypomania/mania | 64% | 77% |

| Depression (n = 101, mean follow-up 15 months) | 21% | 38% |

| Adapted from Calabrese and Delucchi. Am J Psychiatry. 1990;147:431-434 and Calabrese et al. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1993;13:280-283. | ||

Lamotrigine: best hope for monotherapy

Lamotrigine monotherapy has been reported to be effective in some RCBD cases. The data suggest that it possesses both antidepressant and mood-stabilizing properties.10

An open, naturalistic study of 5 women with treatment-refractory rapid cycling by Fatemi et al11 demonstrated both mood-stabilizing and antidepressant effects from lamotrigine monotherapy or augmentation at a mean dose of 185 ±33.5 mg/d. In 14 clinical reports involving 207 patients with bipolar disorder, 66 of whom had rapid cycling, lamotrigine was observed to possess moderate to marked efficacy in depression and hypomania, but only moderate efficacy in mania.

An open, prospective study compared the efficacy of lamotrigine add-on or monotherapy in 41 rapid cyclers to 34 nonrapid cyclers across 48 weeks. Improvement from baseline to last visit was significant between both subgroups for depressive and hypomanic symptoms. Patients presenting with more severe manic symptoms did less well.13

In the first double-blind, placebo-controlled study of lamotrigine in RCBD,12 182 of 324 patients with rapid cycling responded to treatment with open-label lamotrigine and were then randomized to the study’s double-blind phase. Forty-one percent of lamotrigine-treated vs. 26% of placebo-treated patients were stable without relapse during 6 months of monotherapy. Patients with rapid-cycling bipolar II disorder consistently experienced more improvement than their bipolar I counterparts (Figure 1). The results of this only prospective, placebo-controlled, acute-treatment study of rapid-cycling bipolar patients to date indicate that lamotrigine monotherapy is useful for some patients with RCBD, particularly those with bipolar II.

Frye et al14 conducted a double-blind, placebo-controlled study of 23 patients with rapid cycling utilizing a crossover series of three 6-week monotherapy evaluations of lamotrigine, gabapentin, and placebo. Marked antidepressant response on lamotrigine was seen in 45% of the participants compared with 19% of patients on placebo and a similar response rate among those on gabapentin.

A study evaluating the safety and efficacy of 2 dosages of lamotrigine (50 mg/d or 200 mg/d) compared with placebo in the treatment of a major depressive episode in patients with bipolar I disorder over 7 weeks demonstrated significant antidepressant efficacy.15 These bipolar outpatients displayed clinical improvement as early as the third week of treatment, and switch rates for both dosages did not exceed that of placebo. Patients with RCBD, however, were excluded from this initial trial. Subsequent studies have demonstrated similar magnitudes of efficacy in patients with RCBD, primarily in the prevention of depressive episodes, including the 6-month RCBD maintenance study10 and 2 recently completed 18-month maintenance studies of patients with bipolar I disorder, either recently manic or recently depressed.

Lamotrigine thus may have a special role in RCBD treatment. Its most significant side effect in bipolar disorder is benign rash, which has occurred in 9.0% (108 of 1,198) of patients randomized to lamotrigine vs. 7.6% (80 of 1,056) of those randomized to placebo in pivotal multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled bipolar trials.

In mood disorder trials conducted to date, the rate of serious rash, defined as requiring both drug discontinuation and hospitalization, has been 0.06% (2 of 3,153) on lamotrigine and 0.09% (1 out of 1,053) on placebo. No cases of Steven’s Johnson syndrome or toxic epidermal necrolysis were observed.16 A low starting dose and gradual titration of lamotrigine (Table 2) appear to minimize the risk of serious rash.

Levothyroxine: possible add-on therapy

Levothyroxine should be considered as add-on therapy in patients with known hypothyroidism, borderline hypothyroidism, or otherwise treatment-refractory cases.

The strategy of thyroid supplementation is derived from Gjessing’s 1936 report of success in administering hypermetabolic doses of thyroid hormone to patients with periodic catatonia. Stancer and Persad17 initially reported the potential efficacy of this therapeutic maneuver in rapid cyclers; remissions were induced by hypermetabolic thyroid doses in 5 of 7 patients with treatment-refractory bipolar disorder. No data currently support any prophylactic efficacy of thyroid supplementation monotherapy for RCBD treatment.

Bauer and Whybrow18 suggest that thyroid supplementation with T4 added to mood stabilizers augments efficacy independent of pre-existing thyroid function. The potential side effects of long-term levothryoxine administration, namely osteoporosis and cardiac arrhythmias, limit the usefulness of thyroid augmentation in RCBD.

Atypical antipsychotics: perhaps in combination

Coadministering atypical antipsychotics in other mood stabilizers may help rapid cyclers with current or past psychotic symptoms during their mood episodes, but further study is clearly needed.

Atypical antipsychotic medications may have specific mood-stabilizing properties, particularly in the management of mixed and manic states. In the first prospective trial of clozapine monotherapy in bipolar disorder, Calabrese and colleagues in 1994 reported that rapid cycling did not appear to predict nonresponse to treatment.

In the first randomized, controlled trial involving clozapine in bipolar disorder, Suppes et al19 noted significant improvement for symptoms of mania, psychosis, and global improvement. Subjects with nonpsychotic bipolar disorder showed a degree of improvement similar to that seen in the entire clozapine-treated group. These results support a mood-stabilizing role for clozapine.

Preliminary studies of risperidone and olanzapine further suggest therapeutic utility for atypical antipsychotics.

Figure 1 LAMOTRIGINE VS. PLACEBO IN RAPID-CYCLING BIPOLAR DISORDER

Table 2

DOSAGE PLAN FOR LAMOTRIGINE IN MONOTHERAPY AND COMBINATION

| Treatment period | Type of therapy | Daily dosage |

|---|---|---|

| Weeks 1-2 | Monotherapy With divalproex With carbamazepine | 25 mg 12.5 mg 50 mg |

| Weeks 3-4 | Monotherapy With divalproex With carbamazepine | 50 mg 25 mg 100 mg |

| Week 5 | Monotherapy With divalproex With carbamazepine | 100 mg 50 mg 200 mg |

| Thereafter | Monotherapy With divalproex With carbamazepine | 200 mg 100 mg 400 mg |

Topiramate: in patients with weight problems

Evidence from 12 open studies of 223 patients with bipolar disorder suggest that this anticonvulsant may possess mood-stabilizing properties while sparing patients the weight gain commonly seen with other pharmacotherapies.

Two studies of topiramate as an add-on therapy come to mind. Marcotte in 1998 retrospectively studied 44 patients with RCBD, 23 (52%) of whom demonstrated moderate or marked improvement on a mean topiramate dosage of 200 mg/d.

Sachs also reported that symptoms for some patients with a treatment-refractory bipolar disorder could be improved when topiramate was added to their medication regimen. Available data encourage further controlled studies of topiramate add-on therapy for RCBD, especially in obese patients.

Gabapentin: contradictory reports

Preliminary data from 14 open-label studies of gabapentin in 302 bipolar patients reported a response rate of around 67% when used as an add-on therapy, usually in mania or mixed states. A moderate antimanic effect was observed among a total of 23 rapid cyclers in 9 of the studies.

The reports are contradictory, however, and available data do not firmly support the agent’s efficacy in RCBD treatment.

Other potential uses for gabapentin are being investigated, such as antidepressant augmentation, anxiety, and chronic pain. Thus, patients with RCBD and a comorbid illness may benefit from add-on gabapentin.

ECT: Some limited success

Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) has been implicated less frequently than antidepressants in the induction of rapid cycling, and when this does occur it is usually in the context of combined ECT/antidepressant therapies.

Berma and Wolpert in 1987 reported a case of successful ECT treatment of rapid cycling in an adolescent who had been treated with trimipramine for depression. Vanelle et al in 1994 suggested that maintenance ECT works well in 22 treatment-resistant bipolar patients, including 4 with rapid cycling, over an 18-month treatment period.

Behavioral intervention: changing sleep routines

NIMH research of 15 rapid cyclers who were studied for 3 months looked at behavioral interventions and their effect on switching (Feldman-Naim 1997). This study suggested that patients were more likely to switch from depression into hypomania/mania during daytime hours and from mania/hypomania into depression during nighttime.

The use of light therapy or activity and exercise during depression and the use of induced sleep or exposure to darkness during mania/hypomania may be therapeutic. Wehr and colleagues supported this in a 1998 report of one patient studied over several years, comparing this rapid-cycling patient’s regular sleep routine with prolonged (10 to 14 hours per night) and enforced bed rest in the dark.7 The promotion of sleep by scheduling regular nighttime periods of enforced bed rest in the dark may help prevent mania and stabilize mood in rapid cyclers.

Other add-on possibilities

Haykal in 1990 reported bupropion to be an effective add-on treatment in 5 of 6 patients with refractory, rapid-cycling bipolar II disorder. Benefit has also been reported from clorgyline, clonidine, magnesium, primidone, and acetazolamide.

Calcium-channel blockers may also offer clinical utility, although supportive evidence is limited. Nimodipine was evaluated for efficacy in 30 patients with treatment-refractory affective illness by the NIMH and Passaglia et al in 1998. Patients who improved on this agent had ultradian rapid cycling, defined in the study as those with affective episodes lasting as short as a week.

A recommended treatment strategy

Based on the available data in bipolar I rapid cycling, we recommend initial treatment with divalproex followed by augmentation with lithium if hypomanic or manic episodes persist, lamotrigine if breakthrough episodes are predominantly depressive, and atypical antipsychotics if psychotic symptoms or true mixed states remain.

For patients presenting with bipolar II rapid cycling, we recommend starting with lamotrigine, then augmenting with divalproex or lithium for breakthrough episodes. Lamotrigine shows more promise because of its reportedly greater antidepressant properties and lack of cycle induction or switching, but offers only modest antimanic therapy.

Pending further investigations, current application of the data suggests that when treating patients with RCBD, conventional antidepressants should be avoided and, if first-line therapies are not effective, the clinician should consider moving to combination drug therapy with 2 or more agents.

Related resources

- Bauer MS, Calabrese JR, Dunner DL, et al. Multi-site data reanalysis: validity of rapid cycling as a course modifier for bipolar disorder in DSM-IV. Am J Psychiatry. 1994;151:506-515.

- Calabrese JR, Kimmel SE, Woyshville MJ, et al. Clozapine in treatment refractory mania. Am J Psychiatry. 1996;153(6):759-764.

- Calabrese JR, Bowden CL, McElroy SL, et al. Spectrum of activity of lamotrigine in treatment refractory bipolar disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156(7):1019-1023.

- Sachs GS. Printz DJ. Kahn DA. Carpenter D. Docherty JP. The expert consensus guideline series: medication treatment of bipolar disorder 2000. Postgraduate Medicine. April 2000; Spec No:1-104.

Drug brand names

- Buproprion • Wellbutrin

- Carbamazepine • Tegretol

- Clonidine • Catapres

- Clozapine • Clozaril

- Divalproex sodium • Depakote

- Gabapentin • Neurontin

- Lamotrigine • Lamictal

- Levothyroxine • Synthroid, Levothroid, Levoxyl

- Olanzapine • Zyprexa

- Nimodipine • Nimotop

- Primidonem • Mysoline

- Topiramate • Topamax

Disclosure

Dr. Muzina reports that he is a member of the Eli Lilly and Co. speaker’s bureau.

Dr. Calabrese reports that he receives research/grant support from Abbott Laboratories, GlaxoSmithKline, and Wyeth-Ayerst Pharmaceuticals, and serves as a consultant to Abbott Pharmaceuticals, Eli Lilly and Co., GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corp., and Parke Davis/Warner Lambert.

Patients with rapid-cycling bipolar disorder (RCBD) can be frustrating to treat. Despite growing research and data, knowledge and effective therapies remain limited. How do you manage patients with rapid cycling who do not respond robustly to lithium, divalproex, or carbamazepine monotherapy? Are combination therapies likely to be more effective? Where does lamotrigine fit in? Is there a role for conventional antidepressants?

We’ll explore these and related questions—but the final answers are not yet in. Recognition of RCBD is important because it presents such difficult treatment challenges. Available evidence does suggest that rapid cycling as defined in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition (Box 1), describes a clinically specific course of illness that may require treatments different from currently used traditional drug therapies for nonrapid cycling bipolar disorder, particularly as no one agent appears to provide ideal bimodal treatment and prophylaxis of this bipolar disorder variant.

Rapid cycling is a specifier of the longitudinal course of illness presentation that is seen almost exclusively in bipolar disorder and is associated with a greater morbidity. Dunner and Fieve1 originally coined the term when evaluating clinical factors associated with lithium prophylaxis failure. Since that time the validity of rapid cycling as a distinct course modifier for bipolar disorder has been supported by multiple studies, leading to its inclusion in the fourth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of the APA (1994).

According to DSM-IV, the course specifier of rapid cycling applies to “at least 4 episodes of a mood disturbance in the previous 12 months that meet criteria for a manic episode, a hypomanic episode, or a major depressive episode.” The episodes must be demarcated by a full or partial remission lasting at least 2 months or by a switch to a mood state of opposite polarity.

Early reports noted that patients suffering from RCBD did not respond adequately when treated with lithium.1 Other observations indicated that divalproex was more effective in this patient population, particularly for the illness’ hypomanic or manic phases.2 We hope that the following evaluation of these and other drug therapies will prove helpful.

Watch out for antidepressants

Most concerning has been the frequency and severity of treatment-refractory depressive phases of RCBD that may be exacerbated by antidepressant use (cycle induction or acceleration). Indeed, the frequent recurrence of refractory depression has been described as the hallmark of this bipolar disorder variant.3

Lithium: the scale weighs against it

Although an excellent mood stabilizer for most patients with bipolar disorder, lithium monotherapy is less than ideal for patients with the rapid-cycling variant, particularly in treatment or prevention of depressive or mixed episodes. The efficacy of lithium is likely decreased by the concurrent administration of antidepressant medication and increased when administered with other mood stabilizers.

The landmark article by Dunner and Fieve,1 which described a placebo-controlled, double-blind maintenance study in a general cohort of 55 patients, tried to clarify factors associated with the failure of lithium prophylaxis in bipolar disorder. Rapid cyclers comprised 20% of the subjects and 80% were nonrapid cyclers. Rapid cyclers were disproportionately represented in the lithium failure group. Lithium failures included 82% (9 of 11) of rapid cyclers compared to 41% (18 of 44) of nonrapid cyclers. Lithium failure was defined as (1) hospitalization for, or (2) treatment of, mania or (3) depression during lithium therapy, or as mood symptoms that, as documented by rating scales, were sufficient to warrant a diagnosis of mild depression, hypomania, or mania persisting for at least 2 weeks.

Kukopulos et al4 replicated the findings of Dunner and Fieve in a study of the longitudinal clinical course of 434 bipolar patients. Of these patients, 50 were rapid cyclers and had received continuous lithium therapy for more than a year, with good to partial prophylaxis in only 28%. Maj and colleagues5 published a 5-year prospective study of lithium therapy in 402 patients with bipolar disorder and noted the absence of rapid cycling in good responders to lithium but an incidence rate of 26% in nonresponders to lithium.

Other investigators have reported better response in RCBD. In a select cohort of lithium-responsive bipolar I and II patients, Tondo et al6 concluded that lithium maintenance yields striking long-term reductions in depressive and manic morbidity, more so in rapid cycling type II patients. This study, however, was in a cohort of lithium responders and excluded patients who had been exposed to antipsychotic or antidepressant medications for more than 3 months, those on chronic anticonvulsant therapy, and those with substance abuse disorders.

Although most studies do report poor response to lithium therapy in RCBD, Wehr and colleagues7 suggest that in some patients with rapid cycling, the discontinuation of antidepressant drugs may allow lithium to act as a more effective anticycling mood-stabilizing agent.

Divalproex: effective in manic phase

In contrast to lithium, an open trial of a homogenous cohort of patients with RCBD by Calabrese and colleagues3,8 found divalproex to possess moderate to marked acute and prophylactic antimanic properties with only modest antidepressant effects (Table 1). Data from 6 open studies involving 147 patients with rapid cycling suggest that divalproex possesses moderate to marked efficacy in the manic phase, but poor to moderate efficacy in the depressed phase. Positive outcome predictors were bipolar II and mixed states, no prior lithium therapy, and a positive family history of affective disorder. Predictors of negative response included increase in frequency and severity of mania, and borderline personality disorder.

Divalproex therapy in combination with lithium may improve response rates.9 Calabrese and colleagues, however, have examined large cohorts of patients, including those comorbid with alcohol, cocaine, and/or cannabis abuse, treated with a lithium-divalproex combination over 6-month study periods. The researchers found that only 25% to 50% of patients stabilized, and that of those not exhibiting a response, the majority (75%) did not respond because of treatment-refractory depression in the context of RCBD.3

Although experts believe divalproex to be more effective than lithium in preventing episodes associated with RCBD, such a conclusion awaits confirmation with the near completion of a double-blind, 20-month maintenance trial sponsored by the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH).

Carbamazepine’s role in combination therapy

Early reports by Post and colleagues in 1987 suggested that rapid cycling predicted positive response to carbamazepine, but later findings by Okuma in 1993 refuted this. Other collective open and controlled studies suggest that this anticonvulsant possesses moderate to marked efficacy in the manic phase, and poor to moderate efficacy in the depressed phase of RCBD. Again, combination therapy with lithium may offer greater efficacy. Of significance, carbamazepine treatment outcomes have not been prospectively evaluated in a homogeneous cohort of rapid cyclers.

The limitations of carbamazepine therapy are well known and available evidence also does not seem to support monotherapy with this agent as being useful in RCBD, especially in the treatment and prophylaxis of depressive or mixed phases of the disorder. Thus, further controlled studies are needed to examine the agent’s potential role and safety in combination therapies for RCBD.

Table 1

SPECTRUM OF ACUTE AND PROPHYLACTIC EFFICACY OF DIVALPROEX IN RAPID-CYCLING BIPOLAR DISORDER

| Spectrum of marked responses to divalproex in bipolar rapid cycling | ||

|---|---|---|

| Acute | Prophylactic | |

| Dysphoric hypomania/mania | 87% | 89% |

| Elated hypomania/mania | 64% | 77% |

| Depression (n = 101, mean follow-up 15 months) | 21% | 38% |

| Adapted from Calabrese and Delucchi. Am J Psychiatry. 1990;147:431-434 and Calabrese et al. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1993;13:280-283. | ||

Lamotrigine: best hope for monotherapy

Lamotrigine monotherapy has been reported to be effective in some RCBD cases. The data suggest that it possesses both antidepressant and mood-stabilizing properties.10

An open, naturalistic study of 5 women with treatment-refractory rapid cycling by Fatemi et al11 demonstrated both mood-stabilizing and antidepressant effects from lamotrigine monotherapy or augmentation at a mean dose of 185 ±33.5 mg/d. In 14 clinical reports involving 207 patients with bipolar disorder, 66 of whom had rapid cycling, lamotrigine was observed to possess moderate to marked efficacy in depression and hypomania, but only moderate efficacy in mania.

An open, prospective study compared the efficacy of lamotrigine add-on or monotherapy in 41 rapid cyclers to 34 nonrapid cyclers across 48 weeks. Improvement from baseline to last visit was significant between both subgroups for depressive and hypomanic symptoms. Patients presenting with more severe manic symptoms did less well.13

In the first double-blind, placebo-controlled study of lamotrigine in RCBD,12 182 of 324 patients with rapid cycling responded to treatment with open-label lamotrigine and were then randomized to the study’s double-blind phase. Forty-one percent of lamotrigine-treated vs. 26% of placebo-treated patients were stable without relapse during 6 months of monotherapy. Patients with rapid-cycling bipolar II disorder consistently experienced more improvement than their bipolar I counterparts (Figure 1). The results of this only prospective, placebo-controlled, acute-treatment study of rapid-cycling bipolar patients to date indicate that lamotrigine monotherapy is useful for some patients with RCBD, particularly those with bipolar II.

Frye et al14 conducted a double-blind, placebo-controlled study of 23 patients with rapid cycling utilizing a crossover series of three 6-week monotherapy evaluations of lamotrigine, gabapentin, and placebo. Marked antidepressant response on lamotrigine was seen in 45% of the participants compared with 19% of patients on placebo and a similar response rate among those on gabapentin.

A study evaluating the safety and efficacy of 2 dosages of lamotrigine (50 mg/d or 200 mg/d) compared with placebo in the treatment of a major depressive episode in patients with bipolar I disorder over 7 weeks demonstrated significant antidepressant efficacy.15 These bipolar outpatients displayed clinical improvement as early as the third week of treatment, and switch rates for both dosages did not exceed that of placebo. Patients with RCBD, however, were excluded from this initial trial. Subsequent studies have demonstrated similar magnitudes of efficacy in patients with RCBD, primarily in the prevention of depressive episodes, including the 6-month RCBD maintenance study10 and 2 recently completed 18-month maintenance studies of patients with bipolar I disorder, either recently manic or recently depressed.

Lamotrigine thus may have a special role in RCBD treatment. Its most significant side effect in bipolar disorder is benign rash, which has occurred in 9.0% (108 of 1,198) of patients randomized to lamotrigine vs. 7.6% (80 of 1,056) of those randomized to placebo in pivotal multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled bipolar trials.

In mood disorder trials conducted to date, the rate of serious rash, defined as requiring both drug discontinuation and hospitalization, has been 0.06% (2 of 3,153) on lamotrigine and 0.09% (1 out of 1,053) on placebo. No cases of Steven’s Johnson syndrome or toxic epidermal necrolysis were observed.16 A low starting dose and gradual titration of lamotrigine (Table 2) appear to minimize the risk of serious rash.

Levothyroxine: possible add-on therapy

Levothyroxine should be considered as add-on therapy in patients with known hypothyroidism, borderline hypothyroidism, or otherwise treatment-refractory cases.

The strategy of thyroid supplementation is derived from Gjessing’s 1936 report of success in administering hypermetabolic doses of thyroid hormone to patients with periodic catatonia. Stancer and Persad17 initially reported the potential efficacy of this therapeutic maneuver in rapid cyclers; remissions were induced by hypermetabolic thyroid doses in 5 of 7 patients with treatment-refractory bipolar disorder. No data currently support any prophylactic efficacy of thyroid supplementation monotherapy for RCBD treatment.

Bauer and Whybrow18 suggest that thyroid supplementation with T4 added to mood stabilizers augments efficacy independent of pre-existing thyroid function. The potential side effects of long-term levothryoxine administration, namely osteoporosis and cardiac arrhythmias, limit the usefulness of thyroid augmentation in RCBD.

Atypical antipsychotics: perhaps in combination

Coadministering atypical antipsychotics in other mood stabilizers may help rapid cyclers with current or past psychotic symptoms during their mood episodes, but further study is clearly needed.

Atypical antipsychotic medications may have specific mood-stabilizing properties, particularly in the management of mixed and manic states. In the first prospective trial of clozapine monotherapy in bipolar disorder, Calabrese and colleagues in 1994 reported that rapid cycling did not appear to predict nonresponse to treatment.

In the first randomized, controlled trial involving clozapine in bipolar disorder, Suppes et al19 noted significant improvement for symptoms of mania, psychosis, and global improvement. Subjects with nonpsychotic bipolar disorder showed a degree of improvement similar to that seen in the entire clozapine-treated group. These results support a mood-stabilizing role for clozapine.

Preliminary studies of risperidone and olanzapine further suggest therapeutic utility for atypical antipsychotics.

Figure 1 LAMOTRIGINE VS. PLACEBO IN RAPID-CYCLING BIPOLAR DISORDER

Table 2

DOSAGE PLAN FOR LAMOTRIGINE IN MONOTHERAPY AND COMBINATION

| Treatment period | Type of therapy | Daily dosage |

|---|---|---|

| Weeks 1-2 | Monotherapy With divalproex With carbamazepine | 25 mg 12.5 mg 50 mg |

| Weeks 3-4 | Monotherapy With divalproex With carbamazepine | 50 mg 25 mg 100 mg |

| Week 5 | Monotherapy With divalproex With carbamazepine | 100 mg 50 mg 200 mg |

| Thereafter | Monotherapy With divalproex With carbamazepine | 200 mg 100 mg 400 mg |

Topiramate: in patients with weight problems

Evidence from 12 open studies of 223 patients with bipolar disorder suggest that this anticonvulsant may possess mood-stabilizing properties while sparing patients the weight gain commonly seen with other pharmacotherapies.

Two studies of topiramate as an add-on therapy come to mind. Marcotte in 1998 retrospectively studied 44 patients with RCBD, 23 (52%) of whom demonstrated moderate or marked improvement on a mean topiramate dosage of 200 mg/d.

Sachs also reported that symptoms for some patients with a treatment-refractory bipolar disorder could be improved when topiramate was added to their medication regimen. Available data encourage further controlled studies of topiramate add-on therapy for RCBD, especially in obese patients.

Gabapentin: contradictory reports

Preliminary data from 14 open-label studies of gabapentin in 302 bipolar patients reported a response rate of around 67% when used as an add-on therapy, usually in mania or mixed states. A moderate antimanic effect was observed among a total of 23 rapid cyclers in 9 of the studies.

The reports are contradictory, however, and available data do not firmly support the agent’s efficacy in RCBD treatment.

Other potential uses for gabapentin are being investigated, such as antidepressant augmentation, anxiety, and chronic pain. Thus, patients with RCBD and a comorbid illness may benefit from add-on gabapentin.

ECT: Some limited success

Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) has been implicated less frequently than antidepressants in the induction of rapid cycling, and when this does occur it is usually in the context of combined ECT/antidepressant therapies.

Berma and Wolpert in 1987 reported a case of successful ECT treatment of rapid cycling in an adolescent who had been treated with trimipramine for depression. Vanelle et al in 1994 suggested that maintenance ECT works well in 22 treatment-resistant bipolar patients, including 4 with rapid cycling, over an 18-month treatment period.

Behavioral intervention: changing sleep routines

NIMH research of 15 rapid cyclers who were studied for 3 months looked at behavioral interventions and their effect on switching (Feldman-Naim 1997). This study suggested that patients were more likely to switch from depression into hypomania/mania during daytime hours and from mania/hypomania into depression during nighttime.

The use of light therapy or activity and exercise during depression and the use of induced sleep or exposure to darkness during mania/hypomania may be therapeutic. Wehr and colleagues supported this in a 1998 report of one patient studied over several years, comparing this rapid-cycling patient’s regular sleep routine with prolonged (10 to 14 hours per night) and enforced bed rest in the dark.7 The promotion of sleep by scheduling regular nighttime periods of enforced bed rest in the dark may help prevent mania and stabilize mood in rapid cyclers.

Other add-on possibilities

Haykal in 1990 reported bupropion to be an effective add-on treatment in 5 of 6 patients with refractory, rapid-cycling bipolar II disorder. Benefit has also been reported from clorgyline, clonidine, magnesium, primidone, and acetazolamide.

Calcium-channel blockers may also offer clinical utility, although supportive evidence is limited. Nimodipine was evaluated for efficacy in 30 patients with treatment-refractory affective illness by the NIMH and Passaglia et al in 1998. Patients who improved on this agent had ultradian rapid cycling, defined in the study as those with affective episodes lasting as short as a week.

A recommended treatment strategy

Based on the available data in bipolar I rapid cycling, we recommend initial treatment with divalproex followed by augmentation with lithium if hypomanic or manic episodes persist, lamotrigine if breakthrough episodes are predominantly depressive, and atypical antipsychotics if psychotic symptoms or true mixed states remain.

For patients presenting with bipolar II rapid cycling, we recommend starting with lamotrigine, then augmenting with divalproex or lithium for breakthrough episodes. Lamotrigine shows more promise because of its reportedly greater antidepressant properties and lack of cycle induction or switching, but offers only modest antimanic therapy.

Pending further investigations, current application of the data suggests that when treating patients with RCBD, conventional antidepressants should be avoided and, if first-line therapies are not effective, the clinician should consider moving to combination drug therapy with 2 or more agents.

Related resources

- Bauer MS, Calabrese JR, Dunner DL, et al. Multi-site data reanalysis: validity of rapid cycling as a course modifier for bipolar disorder in DSM-IV. Am J Psychiatry. 1994;151:506-515.

- Calabrese JR, Kimmel SE, Woyshville MJ, et al. Clozapine in treatment refractory mania. Am J Psychiatry. 1996;153(6):759-764.

- Calabrese JR, Bowden CL, McElroy SL, et al. Spectrum of activity of lamotrigine in treatment refractory bipolar disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156(7):1019-1023.

- Sachs GS. Printz DJ. Kahn DA. Carpenter D. Docherty JP. The expert consensus guideline series: medication treatment of bipolar disorder 2000. Postgraduate Medicine. April 2000; Spec No:1-104.

Drug brand names

- Buproprion • Wellbutrin

- Carbamazepine • Tegretol

- Clonidine • Catapres

- Clozapine • Clozaril

- Divalproex sodium • Depakote

- Gabapentin • Neurontin

- Lamotrigine • Lamictal

- Levothyroxine • Synthroid, Levothroid, Levoxyl

- Olanzapine • Zyprexa

- Nimodipine • Nimotop

- Primidonem • Mysoline

- Topiramate • Topamax

Disclosure

Dr. Muzina reports that he is a member of the Eli Lilly and Co. speaker’s bureau.

Dr. Calabrese reports that he receives research/grant support from Abbott Laboratories, GlaxoSmithKline, and Wyeth-Ayerst Pharmaceuticals, and serves as a consultant to Abbott Pharmaceuticals, Eli Lilly and Co., GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corp., and Parke Davis/Warner Lambert.

1. Dunner DL, Fieve RR. Clinical factors in lithium carbonate prophylaxis failure. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1974;20:229-233.

2. Calabrese JR, Delucchi GA. Spectrum of efficacy of valproate in 55 rapid-cycling manic depressives. Am J Psychiatry. 1990;147(4):431-434.

3. Calabrese JR, Shelton MD, Bowden CL, et al. Bipolar rapid cycling: Focus on depression as its hallmark. J Clin Psychiatry. 2001;62(Suppl 14):34-41.

4. Kukopulos A, Reginaldi D, Laddomada P, et al. Course of the manic depressive cycle and changes caused by treatment. Pharmacopsychiatry. 1980;13:156-167.

5. Maj M, et al. Long-term outcome of lithium prophylaxis in bipolar disorder: a 5-year prospective study of 402 patients at a lithium clinic. Am J Psychiatry. 1998;155:30-35.

6. Tondo L, Baldessarini RJ, et al. Lithium maintenance treatment of depression and mania in bipolar I and bipolar II disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 1998;155:638-645.

7. Wehr TA, Sack DA, Rosenthal NE, et al. Rapid cycling affective disorder: contributing factors and treatment responses in 51 patients. Am J Psychiatry. 1988;145:179-84.

8. Calabrese JR, Woyshville MJ, Kimmel SE. Rapport DJ: Predictors of valproate response in bipolar rapid cycling. J Clin Psychopharmacology. 1993;13(4):280-283.

9. Sharma V, Persad E, et al. Treatment of rapid cycling bipolar disorder with combination therapy of valproate and lithium. Can J Psychiatry. 1993;38:137-139.

10. Calabrese JR, Suppes T, Bowden CL, et al. for the Lamictal 614 Study Group. A double-blind, placebo-controlled, prophylaxis study of lamotrigine in rapid cycling bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2000;61(11):841-850.

11. Fatemi SH, Rapport DJ, Calabrese JR, et al. Lamotrigine in rapid cycling bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 1997;58:522-527.

12. Calabrese JR, Bowden CL, et al. for the Lamictal 602 Study Group. A double-blind placebo-controlled study of lamotrigine monotherapy in outpatients with bipolar I depression. Lamictal 602 Study Group. J Clin Psychiatry 1999;60(2):79-88.

13. Bowden CL, Calabrese JR, McElroy SL, et al. Comparison of the efficacy of lamotrigine in rapid cycling and non-rapid cycling bipolar disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 1999;45(8):953-958.

14. Frye MA, et al. A placebo-controlled study of lamotrigine and gabapentin monotherapy in refractory mood disorders. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2000;20:607-614.

15. Calabrese JR, Bowden CL, Sachs GS, et al. A double-blind placebo-controlled study of lamotrigine monotherapy in outpatients with bipolar I depression. Lamictal 602 Study Group. J Clin Psychiatry. 1999;60(2):79-88.

16. Calabrese JR, Bowden CL, DeVeaugh-Geiss J, et al. Lamotrigine demonstrates long term mood stabilization in recently manic patients. Annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association, New Orleans, 2001.

17. Stancer HC, Persad E. Treatment of intractable rapid-cycling manic-depressive disorder with levothyroxine. Clinical observations. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1982;39(3):311-312.

18. Bauer MS, Whybrow PC. Rapid cycling bipolar affective disorder. II. Treatment of refractory rapid cycling with high-dose levothyroxine: a preliminary study.. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1990;47(5):435-40.

19. Suppes T, Webb A, Paul B, Carmody T, et al:. Clinical outcome in a randomized 1-year trial of clozapine versus treatment as usual for patients with treatment-resistant illness and a history of mania. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156:1164-1169.

1. Dunner DL, Fieve RR. Clinical factors in lithium carbonate prophylaxis failure. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1974;20:229-233.

2. Calabrese JR, Delucchi GA. Spectrum of efficacy of valproate in 55 rapid-cycling manic depressives. Am J Psychiatry. 1990;147(4):431-434.

3. Calabrese JR, Shelton MD, Bowden CL, et al. Bipolar rapid cycling: Focus on depression as its hallmark. J Clin Psychiatry. 2001;62(Suppl 14):34-41.

4. Kukopulos A, Reginaldi D, Laddomada P, et al. Course of the manic depressive cycle and changes caused by treatment. Pharmacopsychiatry. 1980;13:156-167.

5. Maj M, et al. Long-term outcome of lithium prophylaxis in bipolar disorder: a 5-year prospective study of 402 patients at a lithium clinic. Am J Psychiatry. 1998;155:30-35.

6. Tondo L, Baldessarini RJ, et al. Lithium maintenance treatment of depression and mania in bipolar I and bipolar II disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 1998;155:638-645.

7. Wehr TA, Sack DA, Rosenthal NE, et al. Rapid cycling affective disorder: contributing factors and treatment responses in 51 patients. Am J Psychiatry. 1988;145:179-84.

8. Calabrese JR, Woyshville MJ, Kimmel SE. Rapport DJ: Predictors of valproate response in bipolar rapid cycling. J Clin Psychopharmacology. 1993;13(4):280-283.

9. Sharma V, Persad E, et al. Treatment of rapid cycling bipolar disorder with combination therapy of valproate and lithium. Can J Psychiatry. 1993;38:137-139.

10. Calabrese JR, Suppes T, Bowden CL, et al. for the Lamictal 614 Study Group. A double-blind, placebo-controlled, prophylaxis study of lamotrigine in rapid cycling bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2000;61(11):841-850.

11. Fatemi SH, Rapport DJ, Calabrese JR, et al. Lamotrigine in rapid cycling bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 1997;58:522-527.

12. Calabrese JR, Bowden CL, et al. for the Lamictal 602 Study Group. A double-blind placebo-controlled study of lamotrigine monotherapy in outpatients with bipolar I depression. Lamictal 602 Study Group. J Clin Psychiatry 1999;60(2):79-88.

13. Bowden CL, Calabrese JR, McElroy SL, et al. Comparison of the efficacy of lamotrigine in rapid cycling and non-rapid cycling bipolar disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 1999;45(8):953-958.

14. Frye MA, et al. A placebo-controlled study of lamotrigine and gabapentin monotherapy in refractory mood disorders. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2000;20:607-614.

15. Calabrese JR, Bowden CL, Sachs GS, et al. A double-blind placebo-controlled study of lamotrigine monotherapy in outpatients with bipolar I depression. Lamictal 602 Study Group. J Clin Psychiatry. 1999;60(2):79-88.

16. Calabrese JR, Bowden CL, DeVeaugh-Geiss J, et al. Lamotrigine demonstrates long term mood stabilization in recently manic patients. Annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association, New Orleans, 2001.

17. Stancer HC, Persad E. Treatment of intractable rapid-cycling manic-depressive disorder with levothyroxine. Clinical observations. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1982;39(3):311-312.

18. Bauer MS, Whybrow PC. Rapid cycling bipolar affective disorder. II. Treatment of refractory rapid cycling with high-dose levothyroxine: a preliminary study.. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1990;47(5):435-40.

19. Suppes T, Webb A, Paul B, Carmody T, et al:. Clinical outcome in a randomized 1-year trial of clozapine versus treatment as usual for patients with treatment-resistant illness and a history of mania. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156:1164-1169.

Rapid-cycling bipolar disorder: Which therapies are most effective?

Patients with rapid-cycling bipolar disorder (RCBD) can be frustrating to treat. Despite growing research and data, knowledge and effective therapies remain limited. How do you manage patients with rapid cycling who do not respond robustly to lithium, divalproex, or carbamazepine monotherapy? Are combination therapies likely to be more effective? Where does lamotrigine fit in? Is there a role for conventional antidepressants?

We’ll explore these and related questions—but the final answers are not yet in. Recognition of RCBD is important because it presents such difficult treatment challenges. Available evidence does suggest that rapid cycling as defined in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition (Box 1), describes a clinically specific course of illness that may require treatments different from currently used traditional drug therapies for nonrapid cycling bipolar disorder, particularly as no one agent appears to provide ideal bimodal treatment and prophylaxis of this bipolar disorder variant.

Rapid cycling is a specifier of the longitudinal course of illness presentation that is seen almost exclusively in bipolar disorder and is associated with a greater morbidity. Dunner and Fieve1 originally coined the term when evaluating clinical factors associated with lithium prophylaxis failure. Since that time the validity of rapid cycling as a distinct course modifier for bipolar disorder has been supported by multiple studies, leading to its inclusion in the fourth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of the APA (1994).

According to DSM-IV, the course specifier of rapid cycling applies to “at least 4 episodes of a mood disturbance in the previous 12 months that meet criteria for a manic episode, a hypomanic episode, or a major depressive episode.” The episodes must be demarcated by a full or partial remission lasting at least 2 months or by a switch to a mood state of opposite polarity.

Early reports noted that patients suffering from RCBD did not respond adequately when treated with lithium.1 Other observations indicated that divalproex was more effective in this patient population, particularly for the illness’ hypomanic or manic phases.2 We hope that the following evaluation of these and other drug therapies will prove helpful.

Watch out for antidepressants

Most concerning has been the frequency and severity of treatment-refractory depressive phases of RCBD that may be exacerbated by antidepressant use (cycle induction or acceleration). Indeed, the frequent recurrence of refractory depression has been described as the hallmark of this bipolar disorder variant.3

Lithium: the scale weighs against it

Although an excellent mood stabilizer for most patients with bipolar disorder, lithium monotherapy is less than ideal for patients with the rapid-cycling variant, particularly in treatment or prevention of depressive or mixed episodes. The efficacy of lithium is likely decreased by the concurrent administration of antidepressant medication and increased when administered with other mood stabilizers.

The landmark article by Dunner and Fieve,1 which described a placebo-controlled, double-blind maintenance study in a general cohort of 55 patients, tried to clarify factors associated with the failure of lithium prophylaxis in bipolar disorder. Rapid cyclers comprised 20% of the subjects and 80% were nonrapid cyclers. Rapid cyclers were disproportionately represented in the lithium failure group. Lithium failures included 82% (9 of 11) of rapid cyclers compared to 41% (18 of 44) of nonrapid cyclers. Lithium failure was defined as (1) hospitalization for, or (2) treatment of, mania or (3) depression during lithium therapy, or as mood symptoms that, as documented by rating scales, were sufficient to warrant a diagnosis of mild depression, hypomania, or mania persisting for at least 2 weeks.

Kukopulos et al4 replicated the findings of Dunner and Fieve in a study of the longitudinal clinical course of 434 bipolar patients. Of these patients, 50 were rapid cyclers and had received continuous lithium therapy for more than a year, with good to partial prophylaxis in only 28%. Maj and colleagues5 published a 5-year prospective study of lithium therapy in 402 patients with bipolar disorder and noted the absence of rapid cycling in good responders to lithium but an incidence rate of 26% in nonresponders to lithium.

Other investigators have reported better response in RCBD. In a select cohort of lithium-responsive bipolar I and II patients, Tondo et al6 concluded that lithium maintenance yields striking long-term reductions in depressive and manic morbidity, more so in rapid cycling type II patients. This study, however, was in a cohort of lithium responders and excluded patients who had been exposed to antipsychotic or antidepressant medications for more than 3 months, those on chronic anticonvulsant therapy, and those with substance abuse disorders.

Although most studies do report poor response to lithium therapy in RCBD, Wehr and colleagues7 suggest that in some patients with rapid cycling, the discontinuation of antidepressant drugs may allow lithium to act as a more effective anticycling mood-stabilizing agent.

Divalproex: effective in manic phase