User login

Verrucous Coalescing Dry Papules and Plaques on the Hip and Flank

The Diagnosis: Blaschkitis

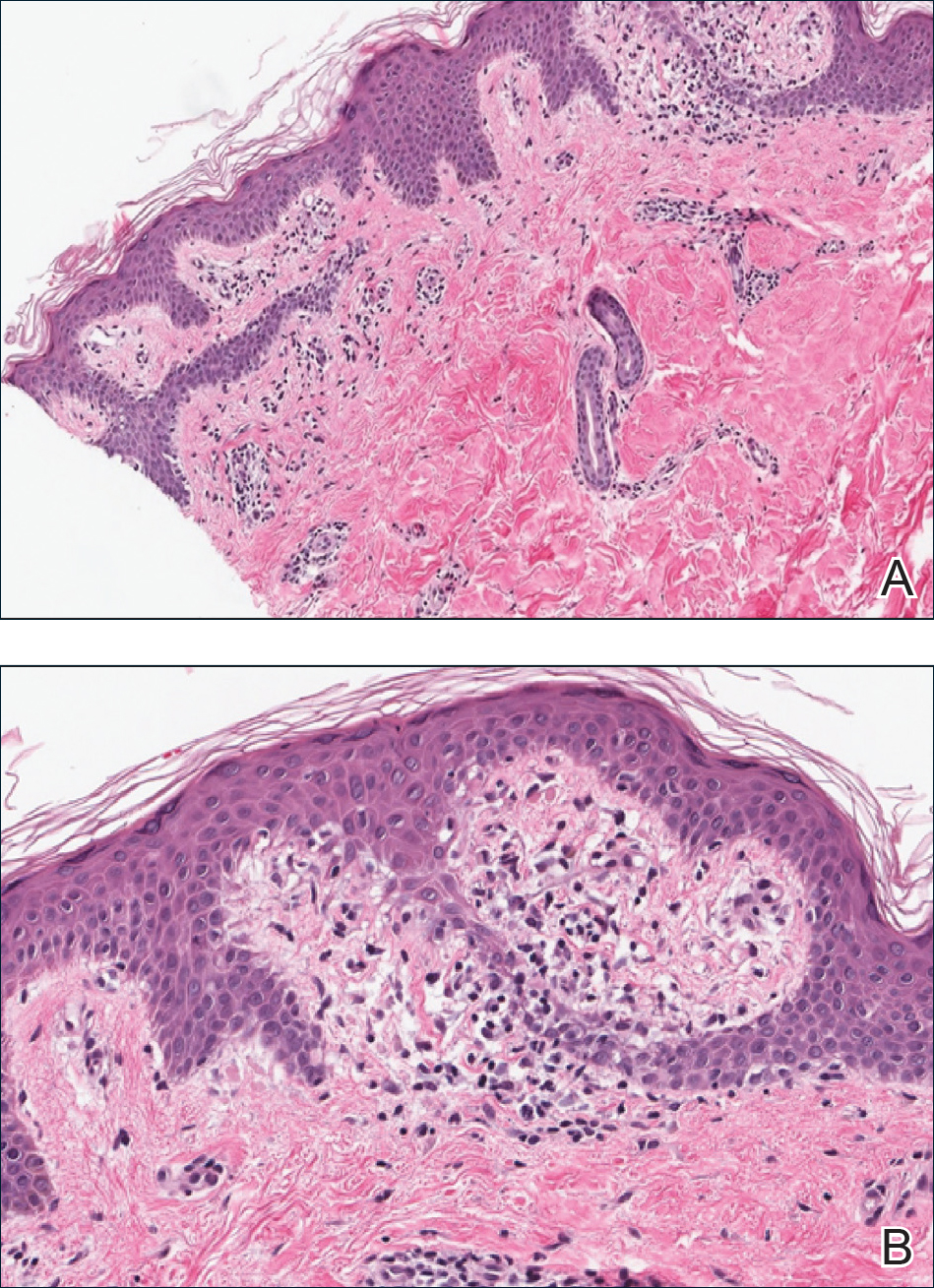

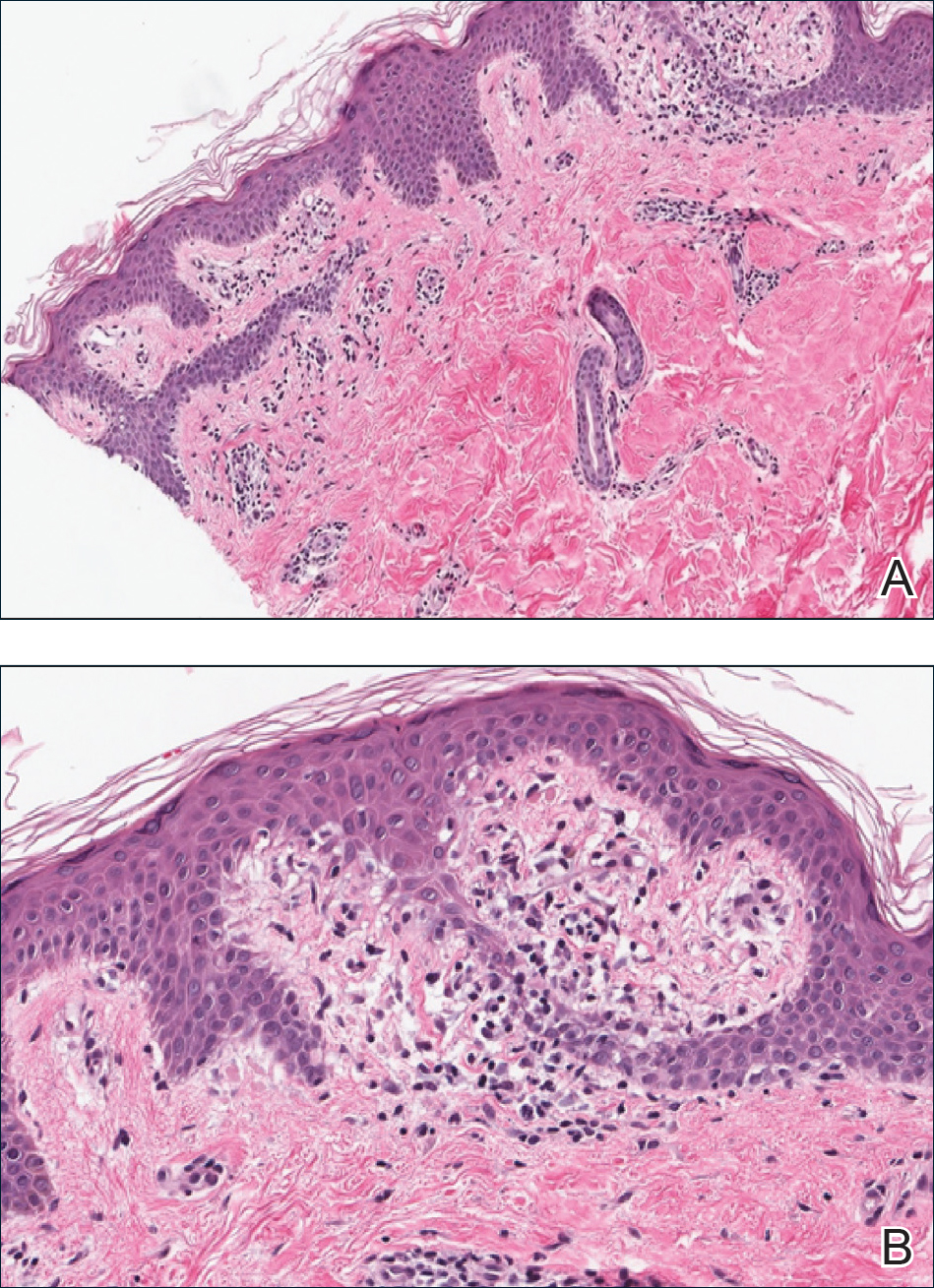

A punch biopsy from the right lateral hip was performed. Histopathologic examination revealed orthokeratosis overlying mild psoriasiform epidermal hyperplasia associated with a lichenoid infiltrate composed almost entirely of lymphocytes (Figure). The infiltrate did not entirely obscure the dermoepidermal junction and spared the adnexal structures. The clinical presentation along with histopathologic analysis confirmed a diagnosis of blaschkitis. The lesions were treated with triamcinolone ointment twice daily as needed, and the patient reported symptomatic and clinical improvement with this intervention at 4-week follow-up.

Described by Grosshans and Marot1 in 1990, blaschkitis is an acquired inflammatory dermatosis following the lines of Blaschko. It predominantly is seen on the trunk and typically presents with pruritic papules and vesicles. It frequently has a relapsing course and is more commonly found in adults. Blaschkitis is considered a form of cutaneous mosaicism representing somatic mutations affecting epidermal cell growth and migration during embryogenesis. It has been proposed that these aberrant cells are not clinically apparent at birth; however, viral infection and drug or other environmental triggers can induce antigen presentation of the clone cells activating a T cell–mediated inflammatory response.2-4

The differential diagnosis includes other acquired Blaschko-linear dermatoses such as lichen striatus, inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus, unilateral lichen planus, linear lichen sclerosus, linear psoriasis, linear fixed drug reaction, lichen nitidus, and others.1,4 Given the overlap in clinical and histopathological presentations of the entities in the differential, it often is difficult to discern the etiology of the papular and vesicular eruption in question. Discrimination of one etiology from the others is further confounded by the fact that these lesions can all be pruritic and initially are treated with topical corticosteroids. A degree of clinical suspicion for blaschkitis coupled with prior understanding of lesional manifestations is helpful in this circumstance. Although classic lichen planus often affects the arms, legs, flexor surfaces, and occasionally the oral mucosa, blaschkitis generally is limited to the trunk. The lesions of lichen planus generally are violaceous, flattopped, polygonal papules that tend to coalesce. They often have a thin, transparent, and adherent scale overlying the papular lesions, and they occasionally demonstrate Wickham striae, which are faint white reticulated networks typically seen in oral mucosal lesions. In the case of lichen nitidus, lesions often follow a geometric line due to the Köbner response, whereas physical trauma from scratching or injury causes lesions to form along the line of insult. Assessing patients for any newly initiated medications can help eliminate lichenoid drug eruptions. Lichen striatus perhaps has the most overlap with blaschkitis, having been described as also following the lines of Blaschko but occurring in children rather than adults. Inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevi also can be distinguished from blaschkitis on this premise, as these lesions arise during the first 5 years of life and generally affect the lower extremities.4,5

Histopathology is somewhat variable but generally includes spongiotic dermatitis with concomitant interface

dermatitis characterized by T-cell infiltration. Spongiosis is a feature less commonly seen in lichen striatus. Lesions can progress over time from spongiotic dermatitis to spongiotic psoriasiform dermatitis and later to spongiotic psoriasiform lichenoid dermatitis.4 Treatment of blaschkitis should begin with reassurance of the benign nature of the dermatosis. Pruritic symptoms can be managed with a course of topical steroids.

Blaschkitis is a rare and self-limiting acquired dermatosis that should be incorporated into the differential diagnosis of Blaschko-linear dermatoses. Further investigation is needed to determine if blaschkitis and lichen striatus represent the ends of a disease spectrum or completely distinct entities.

- Grosshans E, Marot L. Blaschkitis in adults. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 1990;117:9-15.

- Müller CS, Schmaltz R, Vogt T, et al. Lichen striatus and blaschkitis: reappraisal of the concept of blaschkolinear dermatoses [published online November 29, 2010]. Br J Dermatol. 2011;164:257-262.

- Sun BK, Tsao H. X-chromosome inactivation and skin disease. J Invest Dermatol. 2008;128:2753-2759.

- Keegan BR, Kamino H, Fangman W, et al. “Pediatric blaschkitis”: expanding spectrum of childhood acquired Blaschko-linear dermatoses. Pediatr Dermatol. 2007;24:261-267.

- Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, Gilchrest BA, et al, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. 8th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2012.

The Diagnosis: Blaschkitis

A punch biopsy from the right lateral hip was performed. Histopathologic examination revealed orthokeratosis overlying mild psoriasiform epidermal hyperplasia associated with a lichenoid infiltrate composed almost entirely of lymphocytes (Figure). The infiltrate did not entirely obscure the dermoepidermal junction and spared the adnexal structures. The clinical presentation along with histopathologic analysis confirmed a diagnosis of blaschkitis. The lesions were treated with triamcinolone ointment twice daily as needed, and the patient reported symptomatic and clinical improvement with this intervention at 4-week follow-up.

Described by Grosshans and Marot1 in 1990, blaschkitis is an acquired inflammatory dermatosis following the lines of Blaschko. It predominantly is seen on the trunk and typically presents with pruritic papules and vesicles. It frequently has a relapsing course and is more commonly found in adults. Blaschkitis is considered a form of cutaneous mosaicism representing somatic mutations affecting epidermal cell growth and migration during embryogenesis. It has been proposed that these aberrant cells are not clinically apparent at birth; however, viral infection and drug or other environmental triggers can induce antigen presentation of the clone cells activating a T cell–mediated inflammatory response.2-4

The differential diagnosis includes other acquired Blaschko-linear dermatoses such as lichen striatus, inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus, unilateral lichen planus, linear lichen sclerosus, linear psoriasis, linear fixed drug reaction, lichen nitidus, and others.1,4 Given the overlap in clinical and histopathological presentations of the entities in the differential, it often is difficult to discern the etiology of the papular and vesicular eruption in question. Discrimination of one etiology from the others is further confounded by the fact that these lesions can all be pruritic and initially are treated with topical corticosteroids. A degree of clinical suspicion for blaschkitis coupled with prior understanding of lesional manifestations is helpful in this circumstance. Although classic lichen planus often affects the arms, legs, flexor surfaces, and occasionally the oral mucosa, blaschkitis generally is limited to the trunk. The lesions of lichen planus generally are violaceous, flattopped, polygonal papules that tend to coalesce. They often have a thin, transparent, and adherent scale overlying the papular lesions, and they occasionally demonstrate Wickham striae, which are faint white reticulated networks typically seen in oral mucosal lesions. In the case of lichen nitidus, lesions often follow a geometric line due to the Köbner response, whereas physical trauma from scratching or injury causes lesions to form along the line of insult. Assessing patients for any newly initiated medications can help eliminate lichenoid drug eruptions. Lichen striatus perhaps has the most overlap with blaschkitis, having been described as also following the lines of Blaschko but occurring in children rather than adults. Inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevi also can be distinguished from blaschkitis on this premise, as these lesions arise during the first 5 years of life and generally affect the lower extremities.4,5

Histopathology is somewhat variable but generally includes spongiotic dermatitis with concomitant interface

dermatitis characterized by T-cell infiltration. Spongiosis is a feature less commonly seen in lichen striatus. Lesions can progress over time from spongiotic dermatitis to spongiotic psoriasiform dermatitis and later to spongiotic psoriasiform lichenoid dermatitis.4 Treatment of blaschkitis should begin with reassurance of the benign nature of the dermatosis. Pruritic symptoms can be managed with a course of topical steroids.

Blaschkitis is a rare and self-limiting acquired dermatosis that should be incorporated into the differential diagnosis of Blaschko-linear dermatoses. Further investigation is needed to determine if blaschkitis and lichen striatus represent the ends of a disease spectrum or completely distinct entities.

The Diagnosis: Blaschkitis

A punch biopsy from the right lateral hip was performed. Histopathologic examination revealed orthokeratosis overlying mild psoriasiform epidermal hyperplasia associated with a lichenoid infiltrate composed almost entirely of lymphocytes (Figure). The infiltrate did not entirely obscure the dermoepidermal junction and spared the adnexal structures. The clinical presentation along with histopathologic analysis confirmed a diagnosis of blaschkitis. The lesions were treated with triamcinolone ointment twice daily as needed, and the patient reported symptomatic and clinical improvement with this intervention at 4-week follow-up.

Described by Grosshans and Marot1 in 1990, blaschkitis is an acquired inflammatory dermatosis following the lines of Blaschko. It predominantly is seen on the trunk and typically presents with pruritic papules and vesicles. It frequently has a relapsing course and is more commonly found in adults. Blaschkitis is considered a form of cutaneous mosaicism representing somatic mutations affecting epidermal cell growth and migration during embryogenesis. It has been proposed that these aberrant cells are not clinically apparent at birth; however, viral infection and drug or other environmental triggers can induce antigen presentation of the clone cells activating a T cell–mediated inflammatory response.2-4

The differential diagnosis includes other acquired Blaschko-linear dermatoses such as lichen striatus, inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus, unilateral lichen planus, linear lichen sclerosus, linear psoriasis, linear fixed drug reaction, lichen nitidus, and others.1,4 Given the overlap in clinical and histopathological presentations of the entities in the differential, it often is difficult to discern the etiology of the papular and vesicular eruption in question. Discrimination of one etiology from the others is further confounded by the fact that these lesions can all be pruritic and initially are treated with topical corticosteroids. A degree of clinical suspicion for blaschkitis coupled with prior understanding of lesional manifestations is helpful in this circumstance. Although classic lichen planus often affects the arms, legs, flexor surfaces, and occasionally the oral mucosa, blaschkitis generally is limited to the trunk. The lesions of lichen planus generally are violaceous, flattopped, polygonal papules that tend to coalesce. They often have a thin, transparent, and adherent scale overlying the papular lesions, and they occasionally demonstrate Wickham striae, which are faint white reticulated networks typically seen in oral mucosal lesions. In the case of lichen nitidus, lesions often follow a geometric line due to the Köbner response, whereas physical trauma from scratching or injury causes lesions to form along the line of insult. Assessing patients for any newly initiated medications can help eliminate lichenoid drug eruptions. Lichen striatus perhaps has the most overlap with blaschkitis, having been described as also following the lines of Blaschko but occurring in children rather than adults. Inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevi also can be distinguished from blaschkitis on this premise, as these lesions arise during the first 5 years of life and generally affect the lower extremities.4,5

Histopathology is somewhat variable but generally includes spongiotic dermatitis with concomitant interface

dermatitis characterized by T-cell infiltration. Spongiosis is a feature less commonly seen in lichen striatus. Lesions can progress over time from spongiotic dermatitis to spongiotic psoriasiform dermatitis and later to spongiotic psoriasiform lichenoid dermatitis.4 Treatment of blaschkitis should begin with reassurance of the benign nature of the dermatosis. Pruritic symptoms can be managed with a course of topical steroids.

Blaschkitis is a rare and self-limiting acquired dermatosis that should be incorporated into the differential diagnosis of Blaschko-linear dermatoses. Further investigation is needed to determine if blaschkitis and lichen striatus represent the ends of a disease spectrum or completely distinct entities.

- Grosshans E, Marot L. Blaschkitis in adults. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 1990;117:9-15.

- Müller CS, Schmaltz R, Vogt T, et al. Lichen striatus and blaschkitis: reappraisal of the concept of blaschkolinear dermatoses [published online November 29, 2010]. Br J Dermatol. 2011;164:257-262.

- Sun BK, Tsao H. X-chromosome inactivation and skin disease. J Invest Dermatol. 2008;128:2753-2759.

- Keegan BR, Kamino H, Fangman W, et al. “Pediatric blaschkitis”: expanding spectrum of childhood acquired Blaschko-linear dermatoses. Pediatr Dermatol. 2007;24:261-267.

- Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, Gilchrest BA, et al, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. 8th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2012.

- Grosshans E, Marot L. Blaschkitis in adults. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 1990;117:9-15.

- Müller CS, Schmaltz R, Vogt T, et al. Lichen striatus and blaschkitis: reappraisal of the concept of blaschkolinear dermatoses [published online November 29, 2010]. Br J Dermatol. 2011;164:257-262.

- Sun BK, Tsao H. X-chromosome inactivation and skin disease. J Invest Dermatol. 2008;128:2753-2759.

- Keegan BR, Kamino H, Fangman W, et al. “Pediatric blaschkitis”: expanding spectrum of childhood acquired Blaschko-linear dermatoses. Pediatr Dermatol. 2007;24:261-267.

- Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, Gilchrest BA, et al, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. 8th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2012.

A 31-year-old man presented with a recurring pruritic rash on the right lateral flank and hip of 2 years’ duration. Physical examination revealed erythematous, verrucous, dry papules and plaques coalescing into larger plaques on the right flank and hip in dermatomal distributions involving the T10 and T11 dermatomes. A few papules were scattered in a linear eruption along the right flank and right upper thigh. Some postinflammatory changes were noted. No rash was noted over any other area of the body. Physical examination was otherwise unremarkable.

Allergic Contact Dermatitis From Ketoconazole

Case Report

A 65-year-old man presented to the dermatology department for treatment of a scaly rash on the face and scalp. A diagnosis of seborrheic dermatitis was made, and he was prescribed ketoconazole cream 2% and shampoo 2%. Two days later, the patient presented to the emergency department for facial swelling and pruritus, which began 1 day after he began using the ketoconazole cream and shampoo. He reported itching and burning on the face that began within several hours of application followed by progressive facial edema. The patient denied shortness of breath or swelling of the tongue. Physical examination revealed mild facial induration with erythematous plaques on the bilateral cheeks, forehead, and eyelids. The patient was instructed to stop using the ketoconazole cream and shampoo. Within several days of discontinuing use of the ketoconazole products, the dermatitis resolved following treatment with oral diphenhydramine and topical desonide.

Review of the patient’s medical record revealed several likely relevant incidences of undiagnosed recurrent dermatitis. Approximately 2 years earlier, the patient had called his primary care provider to report pain, burning, redness, and itching in the right buttock area following use of ketoconazole cream that the physician had prescribed. Allergic contact dermatitis also had been documented in the patient’s dermatology problem list approximately 1.5 years prior to the current presentation, though a likely causative agent was not listed. Approximately 3 months prior to the current presentation, the patient presented with lower leg rash and edema with documentation of possible allergic reaction to ketoconazole cream.

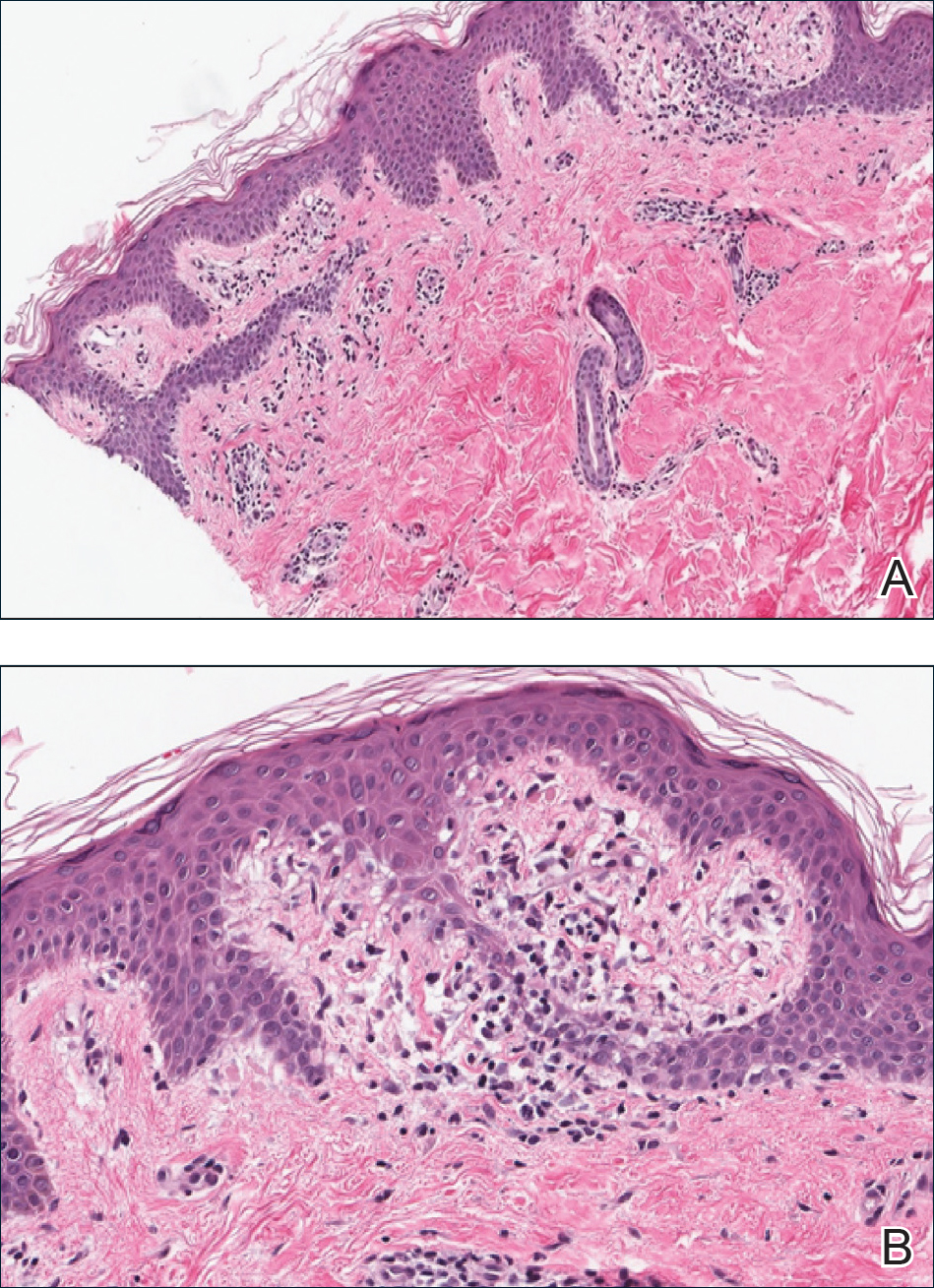

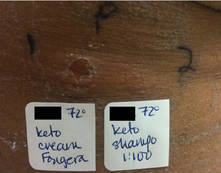

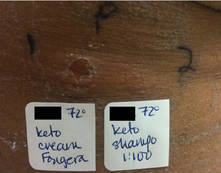

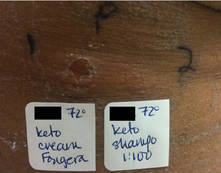

The patient was patch tested several weeks after discontinuation of the ketoconazole products using the 2012 North American Contact Dermatitis Group series (70 allergens), a supplemental series (36 allergens), an antifungal series (10 allergens), and personal products including ketoconazole cream and shampoo (diluted 1:100). Clinically relevant reactions at 72 hours included an extreme reaction (+++) to the patient’s personal ketoconazole cream 2% (E. Fougera & Co)(Figure 1), and strong reactions (++) to purified ketoconazole 5% in petrolatum and ketoconazole cream 2% (E. Fougera & Co) in an antifungal series (Figure 2). A doubtful reaction to methyl methacrylate was not deemed clinically relevant. No reactions were noted to terbinafine cream 1%, clotrimazole cream 1%, nystatin cream, nystatin ointment, econazole nitrate cream 1%, miconazole nitrate cream 2%, tolnaftate cream 1%, or purified clotrimazole 1% in petrolatum.

|

Figure 1. Reading at 72 hours of patient’s personal products (ketoconazole cream 2% and ketoconazole shampoo 2%). |

|

Figure 2. Reading at 72 hours of an antifungal series (ketoconazole cream 2% and purified ketocona-zole 5% in petrolatum). |

Comment

Ketoconazole is a widely used antifungal but rarely is reported as a cause of allergic contact dermatitis. Allergies to inactive ingredients, especially vehicles and preservatives, are more common than allergies to ketoconazole itself. In our patient, allergy to inactive ingredients was ruled out by negative reactions to individual constituents and/or negative reactions to other products containing those ingredients. A literature review via Ovid using the search terms ketoconazole, allergic contact dermatitis, and allergy found 4 reports involving 9 documented patients with type IV hypersensitivity to ketoconazole,1-4 and 1 report of 2 patients who developed anaphylaxis from oral ketoconazole.1 Of the 9 dermatitis cases, 3 patients had positive patch tests to only ketoconazole with no reactions to other imidazoles.2,3 Monoallergy to clotrimazole also has been reported.5 A study by Dooms-Goossens et al4 showed that ketoconazole ranked seventh of 11 imidazole derivatives in its frequency to cause allergic contact dermatitis and did not demonstrate statistically significant cross-reactivity with other imidazoles; cross-reactivity usually occurred with miconazole and sulconazole.

Conclusion

This case of contact dermatitis to ketoconazole demonstrates the importance of patch testing with personal products as well as the unpredictability of cross-reactions within the imidazole class of antifungals.

Acknowledgment

This material is the result of work supported with resources and the use of facilities at the Minneapolis Veterans Affairs Health Care System.

1. Garcia-Bravo B, Mazuecos J, Rodriguez-Pichardo A, et al. Hypersensitivity to ketoconazole preparations: study of 4 cases. Contact Dermatitis. 1989;21:346-348.

2. Valsecchi R, Pansera B, di Landro A, et al. Contact dermatitis from ketoconazole. Contact Dermatitis. 1993;29:162.

3. Santucci B, Cannistraci C, Cristaudo A, et al. Contact dermatitis from ketoconazole cream. Contact Dermatitis. 1992;27:274-275.

4. Dooms-Goossens A, Matura M, Drieghe J, et al. Contact allergy to imidazoles used as antimycotic agents. Contact Dermatitis. 1995;33:73-77.

5. Pullen SK, Warshaw EM. Vulvar allergic contact dermatitis from clotrimazole. Dermatitis. 2010;21:59-60.

Case Report

A 65-year-old man presented to the dermatology department for treatment of a scaly rash on the face and scalp. A diagnosis of seborrheic dermatitis was made, and he was prescribed ketoconazole cream 2% and shampoo 2%. Two days later, the patient presented to the emergency department for facial swelling and pruritus, which began 1 day after he began using the ketoconazole cream and shampoo. He reported itching and burning on the face that began within several hours of application followed by progressive facial edema. The patient denied shortness of breath or swelling of the tongue. Physical examination revealed mild facial induration with erythematous plaques on the bilateral cheeks, forehead, and eyelids. The patient was instructed to stop using the ketoconazole cream and shampoo. Within several days of discontinuing use of the ketoconazole products, the dermatitis resolved following treatment with oral diphenhydramine and topical desonide.

Review of the patient’s medical record revealed several likely relevant incidences of undiagnosed recurrent dermatitis. Approximately 2 years earlier, the patient had called his primary care provider to report pain, burning, redness, and itching in the right buttock area following use of ketoconazole cream that the physician had prescribed. Allergic contact dermatitis also had been documented in the patient’s dermatology problem list approximately 1.5 years prior to the current presentation, though a likely causative agent was not listed. Approximately 3 months prior to the current presentation, the patient presented with lower leg rash and edema with documentation of possible allergic reaction to ketoconazole cream.

The patient was patch tested several weeks after discontinuation of the ketoconazole products using the 2012 North American Contact Dermatitis Group series (70 allergens), a supplemental series (36 allergens), an antifungal series (10 allergens), and personal products including ketoconazole cream and shampoo (diluted 1:100). Clinically relevant reactions at 72 hours included an extreme reaction (+++) to the patient’s personal ketoconazole cream 2% (E. Fougera & Co)(Figure 1), and strong reactions (++) to purified ketoconazole 5% in petrolatum and ketoconazole cream 2% (E. Fougera & Co) in an antifungal series (Figure 2). A doubtful reaction to methyl methacrylate was not deemed clinically relevant. No reactions were noted to terbinafine cream 1%, clotrimazole cream 1%, nystatin cream, nystatin ointment, econazole nitrate cream 1%, miconazole nitrate cream 2%, tolnaftate cream 1%, or purified clotrimazole 1% in petrolatum.

|

Figure 1. Reading at 72 hours of patient’s personal products (ketoconazole cream 2% and ketoconazole shampoo 2%). |

|

Figure 2. Reading at 72 hours of an antifungal series (ketoconazole cream 2% and purified ketocona-zole 5% in petrolatum). |

Comment

Ketoconazole is a widely used antifungal but rarely is reported as a cause of allergic contact dermatitis. Allergies to inactive ingredients, especially vehicles and preservatives, are more common than allergies to ketoconazole itself. In our patient, allergy to inactive ingredients was ruled out by negative reactions to individual constituents and/or negative reactions to other products containing those ingredients. A literature review via Ovid using the search terms ketoconazole, allergic contact dermatitis, and allergy found 4 reports involving 9 documented patients with type IV hypersensitivity to ketoconazole,1-4 and 1 report of 2 patients who developed anaphylaxis from oral ketoconazole.1 Of the 9 dermatitis cases, 3 patients had positive patch tests to only ketoconazole with no reactions to other imidazoles.2,3 Monoallergy to clotrimazole also has been reported.5 A study by Dooms-Goossens et al4 showed that ketoconazole ranked seventh of 11 imidazole derivatives in its frequency to cause allergic contact dermatitis and did not demonstrate statistically significant cross-reactivity with other imidazoles; cross-reactivity usually occurred with miconazole and sulconazole.

Conclusion

This case of contact dermatitis to ketoconazole demonstrates the importance of patch testing with personal products as well as the unpredictability of cross-reactions within the imidazole class of antifungals.

Acknowledgment

This material is the result of work supported with resources and the use of facilities at the Minneapolis Veterans Affairs Health Care System.

Case Report

A 65-year-old man presented to the dermatology department for treatment of a scaly rash on the face and scalp. A diagnosis of seborrheic dermatitis was made, and he was prescribed ketoconazole cream 2% and shampoo 2%. Two days later, the patient presented to the emergency department for facial swelling and pruritus, which began 1 day after he began using the ketoconazole cream and shampoo. He reported itching and burning on the face that began within several hours of application followed by progressive facial edema. The patient denied shortness of breath or swelling of the tongue. Physical examination revealed mild facial induration with erythematous plaques on the bilateral cheeks, forehead, and eyelids. The patient was instructed to stop using the ketoconazole cream and shampoo. Within several days of discontinuing use of the ketoconazole products, the dermatitis resolved following treatment with oral diphenhydramine and topical desonide.

Review of the patient’s medical record revealed several likely relevant incidences of undiagnosed recurrent dermatitis. Approximately 2 years earlier, the patient had called his primary care provider to report pain, burning, redness, and itching in the right buttock area following use of ketoconazole cream that the physician had prescribed. Allergic contact dermatitis also had been documented in the patient’s dermatology problem list approximately 1.5 years prior to the current presentation, though a likely causative agent was not listed. Approximately 3 months prior to the current presentation, the patient presented with lower leg rash and edema with documentation of possible allergic reaction to ketoconazole cream.

The patient was patch tested several weeks after discontinuation of the ketoconazole products using the 2012 North American Contact Dermatitis Group series (70 allergens), a supplemental series (36 allergens), an antifungal series (10 allergens), and personal products including ketoconazole cream and shampoo (diluted 1:100). Clinically relevant reactions at 72 hours included an extreme reaction (+++) to the patient’s personal ketoconazole cream 2% (E. Fougera & Co)(Figure 1), and strong reactions (++) to purified ketoconazole 5% in petrolatum and ketoconazole cream 2% (E. Fougera & Co) in an antifungal series (Figure 2). A doubtful reaction to methyl methacrylate was not deemed clinically relevant. No reactions were noted to terbinafine cream 1%, clotrimazole cream 1%, nystatin cream, nystatin ointment, econazole nitrate cream 1%, miconazole nitrate cream 2%, tolnaftate cream 1%, or purified clotrimazole 1% in petrolatum.

|

Figure 1. Reading at 72 hours of patient’s personal products (ketoconazole cream 2% and ketoconazole shampoo 2%). |

|

Figure 2. Reading at 72 hours of an antifungal series (ketoconazole cream 2% and purified ketocona-zole 5% in petrolatum). |

Comment

Ketoconazole is a widely used antifungal but rarely is reported as a cause of allergic contact dermatitis. Allergies to inactive ingredients, especially vehicles and preservatives, are more common than allergies to ketoconazole itself. In our patient, allergy to inactive ingredients was ruled out by negative reactions to individual constituents and/or negative reactions to other products containing those ingredients. A literature review via Ovid using the search terms ketoconazole, allergic contact dermatitis, and allergy found 4 reports involving 9 documented patients with type IV hypersensitivity to ketoconazole,1-4 and 1 report of 2 patients who developed anaphylaxis from oral ketoconazole.1 Of the 9 dermatitis cases, 3 patients had positive patch tests to only ketoconazole with no reactions to other imidazoles.2,3 Monoallergy to clotrimazole also has been reported.5 A study by Dooms-Goossens et al4 showed that ketoconazole ranked seventh of 11 imidazole derivatives in its frequency to cause allergic contact dermatitis and did not demonstrate statistically significant cross-reactivity with other imidazoles; cross-reactivity usually occurred with miconazole and sulconazole.

Conclusion

This case of contact dermatitis to ketoconazole demonstrates the importance of patch testing with personal products as well as the unpredictability of cross-reactions within the imidazole class of antifungals.

Acknowledgment

This material is the result of work supported with resources and the use of facilities at the Minneapolis Veterans Affairs Health Care System.

1. Garcia-Bravo B, Mazuecos J, Rodriguez-Pichardo A, et al. Hypersensitivity to ketoconazole preparations: study of 4 cases. Contact Dermatitis. 1989;21:346-348.

2. Valsecchi R, Pansera B, di Landro A, et al. Contact dermatitis from ketoconazole. Contact Dermatitis. 1993;29:162.

3. Santucci B, Cannistraci C, Cristaudo A, et al. Contact dermatitis from ketoconazole cream. Contact Dermatitis. 1992;27:274-275.

4. Dooms-Goossens A, Matura M, Drieghe J, et al. Contact allergy to imidazoles used as antimycotic agents. Contact Dermatitis. 1995;33:73-77.

5. Pullen SK, Warshaw EM. Vulvar allergic contact dermatitis from clotrimazole. Dermatitis. 2010;21:59-60.

1. Garcia-Bravo B, Mazuecos J, Rodriguez-Pichardo A, et al. Hypersensitivity to ketoconazole preparations: study of 4 cases. Contact Dermatitis. 1989;21:346-348.

2. Valsecchi R, Pansera B, di Landro A, et al. Contact dermatitis from ketoconazole. Contact Dermatitis. 1993;29:162.

3. Santucci B, Cannistraci C, Cristaudo A, et al. Contact dermatitis from ketoconazole cream. Contact Dermatitis. 1992;27:274-275.

4. Dooms-Goossens A, Matura M, Drieghe J, et al. Contact allergy to imidazoles used as antimycotic agents. Contact Dermatitis. 1995;33:73-77.

5. Pullen SK, Warshaw EM. Vulvar allergic contact dermatitis from clotrimazole. Dermatitis. 2010;21:59-60.

- Contact allergy to topical ketoconazole is rare and its cross-reactivity with other imidazole antifungals is unpredictable.

- Patch testing to personal products often is important for detecting rare allergies.