User login

Flexible Bronchoscopic Removal of 3 Foreign Objects

Consider flexible bronchoscopy as an option to retrieve aspirated foreign bodies in the airway.

Airway foreign-body aspiration may cause no symptoms, although it can produce acute and life-threatening central airway obstruction.1 In the US, at least 2,700 people, including more than 300 children, die of foreign-body aspiration each year.2 Most foreign-body aspirations occur in children and elderly patients.3 In adults, dementia, drug intoxication, strokes, seizures, and neurologic disorders may predispose patients to aspiration.3 Some of the consequences of an aspirated object are complete or partial airway obstruction, respiratory distress and failure, pneumothorax, and hemorrhage.2 In addition, inadvertent aspiration of foreign objects in asymptomatic patients may not be evident for months, resulting in late complications as postobstructive pneumonia, bronchiectasis, or lung abscess.2

We present a case of a patient with documented schizophrenia with nonadherence to his antipsychotic medications who aspirated different objects. Flexible bronchoscopy was performed since rigid bronchoscopy is not available at our institution. Several bronchoscopy tools were required to successfully remove the objects and avoid further invasive interventions, such as cardiothoracic surgery.

Case Presentation

A 55-year-old man with schizophrenia on antipsychotics developed cough, shortness of breath, and dysphagia of 1-month of evolution. Because his symptoms worsened, his mother brought him to the emergency department. Peripheral oxygen saturation was 97% at room air. Lung auscultation was remarkable for bilateral scattered rhonchi and wheezes.

Laboratory results showed leukocytosis with neutrophilia and hypotonic hypovolemic hyponatremia.

The patient stated that he did not remember swallowing any objects, although his mother confirmed that he was not adherent with his antipsychotic medications, which could have predisposed him to aspiration secondary to possible psychotic episodes.

Piperacillin/tazobactam 4.5 g every 8 hours was started to cover anaerobic bacterial organisms causing abscess, and IV fluids were given for hypovolemia. Flexible bronchoscopy (rigid bronchoscopy is superior although not available at our institution) was planned to be performed in the operating room (OR) because we predicted a difficult and prolonged retrieval in view of multiple and different-sized objects.

A bronchoscopy was performed, showing a disk-shaped metallic foreign body at the right main stem bronchus. After multiple attempts using the tripod retrieval tool, a coin was removed (Figures 3A and 3B).

The patient was reintubated without any complications. A postprocedure chest radiograph showed the absence of foreign bodies and no pneumothorax. The patient completed IV antibiotic with piperacillin/tazobactam and supportive therapy with clinical improvement and successful extubation within 2 days. Cardiothoracic surgery was not required. Psychiatry service recommended to continue the same antipsychotic medications, administered only by his mother to assure adherence and to avoid similar future events. The patient was discharged home without any immediate complications despite having had a coin, nail, and screw aspiration (Figure 6).

Discussion

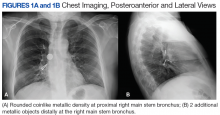

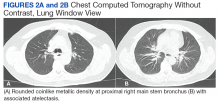

More than 50% of foreign bodies lodge at the right main stem bronchus due to the trachea’s anatomical position.2,4 In adults, foreign-body aspiration may present with nonspecific symptoms, such as cough and dyspnea.4 Other symptoms might include wheezes, chest discomfort, and sputum production. A chest radiograph is helpful as part of the initial diagnostic workup. A chest CT scan without contrast should be performed to confirm the diagnosis and to plan possible foreign-body retrieval.

Bronchoscopy is the gold standard for diagnosis and management of foreign-body aspiration.1 Rigid bronchoscopy is superior to flexible bronchoscopy in removal of large airway foreign bodies.1 The rigid bronchoscopy provides the ability to function as an endotracheal tube, thus allowing control of the airway and a conduit through which foreign bodies can be removed.1 Nonetheless, sometimes retrieval of foreign bodies deeper into the subsegmental bronchi cannot be achieved.1 Moreover, the required equipment or knowledgeable staff is not always available.1 Therefore, flexible bronchoscopy is an option to retrieve airway foreign bodies especially those located distal in the airway and for those medical centers without rigid bronchoscopy as is the case in our institution.

In our case, flexible bronchoscopy was performed in the OR because we predicted a difficult and prolonged retrieval in view of multiple and different-sized objects. Anesthesia Service assistance was requested anticipating need for patient sedation and intubation. We used the tripod and snare retrieval tools to remove 3 foreign objects located at the right main stem bronchus. Even though multiple attempts were made and endotracheal intubation was required, a successful retrieval with flexible bronchoscopy was performed. Moreover, cardiothoracic surgery was not required avoiding more invasive interventions with subsequent morbidity and mortality.

Conclusion

Flexible bronchoscopy is an important tool within the arsenal of the Pulmonology Service. The management of the underlying etiology also should be performed. In our case, the Psychiatry Service recommended that the patient’s medications should be administered by his mother to avoid similar events in the future. Flexible bronchoscopy can be a valuable option for foreign objects removal, especially those distally located in the lung segments as well as in those medical centers where rigid bronchoscopy is not available.

1. Mehta D, Mehta C, Bansal S, Singla S, Tangri N. Flexible bronchoscopic removal of a three piece foreign body from a child’s bronchus. Australas Med J. 2012;5(4):227-230.

2. Mercado JA, Rodríguez W. Occult aspiration of a chicken wishbone as a cause of hemoptysis. P R Health Sci J. 1999;18(1):71-73.

3. Robles-Arias CM, Campos-Santiago Z, Vega MT, Rosa-Cruz F, Rodríguez-Cintrón W. Aspiration of a dental tool during a crown placement procedure. Fed Pract. 2014;31(6):12-14.

4. Blanco-Ramos M, Botana-Rial M, García-Fontán E, Fernández-Villar A, Gallas-Torreira M. Update in the extraction of airway foreign bodies in adults. J Thorac Dis. 2016;8(11):3452-3456.

Consider flexible bronchoscopy as an option to retrieve aspirated foreign bodies in the airway.

Consider flexible bronchoscopy as an option to retrieve aspirated foreign bodies in the airway.

Airway foreign-body aspiration may cause no symptoms, although it can produce acute and life-threatening central airway obstruction.1 In the US, at least 2,700 people, including more than 300 children, die of foreign-body aspiration each year.2 Most foreign-body aspirations occur in children and elderly patients.3 In adults, dementia, drug intoxication, strokes, seizures, and neurologic disorders may predispose patients to aspiration.3 Some of the consequences of an aspirated object are complete or partial airway obstruction, respiratory distress and failure, pneumothorax, and hemorrhage.2 In addition, inadvertent aspiration of foreign objects in asymptomatic patients may not be evident for months, resulting in late complications as postobstructive pneumonia, bronchiectasis, or lung abscess.2

We present a case of a patient with documented schizophrenia with nonadherence to his antipsychotic medications who aspirated different objects. Flexible bronchoscopy was performed since rigid bronchoscopy is not available at our institution. Several bronchoscopy tools were required to successfully remove the objects and avoid further invasive interventions, such as cardiothoracic surgery.

Case Presentation

A 55-year-old man with schizophrenia on antipsychotics developed cough, shortness of breath, and dysphagia of 1-month of evolution. Because his symptoms worsened, his mother brought him to the emergency department. Peripheral oxygen saturation was 97% at room air. Lung auscultation was remarkable for bilateral scattered rhonchi and wheezes.

Laboratory results showed leukocytosis with neutrophilia and hypotonic hypovolemic hyponatremia.

The patient stated that he did not remember swallowing any objects, although his mother confirmed that he was not adherent with his antipsychotic medications, which could have predisposed him to aspiration secondary to possible psychotic episodes.

Piperacillin/tazobactam 4.5 g every 8 hours was started to cover anaerobic bacterial organisms causing abscess, and IV fluids were given for hypovolemia. Flexible bronchoscopy (rigid bronchoscopy is superior although not available at our institution) was planned to be performed in the operating room (OR) because we predicted a difficult and prolonged retrieval in view of multiple and different-sized objects.

A bronchoscopy was performed, showing a disk-shaped metallic foreign body at the right main stem bronchus. After multiple attempts using the tripod retrieval tool, a coin was removed (Figures 3A and 3B).

The patient was reintubated without any complications. A postprocedure chest radiograph showed the absence of foreign bodies and no pneumothorax. The patient completed IV antibiotic with piperacillin/tazobactam and supportive therapy with clinical improvement and successful extubation within 2 days. Cardiothoracic surgery was not required. Psychiatry service recommended to continue the same antipsychotic medications, administered only by his mother to assure adherence and to avoid similar future events. The patient was discharged home without any immediate complications despite having had a coin, nail, and screw aspiration (Figure 6).

Discussion

More than 50% of foreign bodies lodge at the right main stem bronchus due to the trachea’s anatomical position.2,4 In adults, foreign-body aspiration may present with nonspecific symptoms, such as cough and dyspnea.4 Other symptoms might include wheezes, chest discomfort, and sputum production. A chest radiograph is helpful as part of the initial diagnostic workup. A chest CT scan without contrast should be performed to confirm the diagnosis and to plan possible foreign-body retrieval.

Bronchoscopy is the gold standard for diagnosis and management of foreign-body aspiration.1 Rigid bronchoscopy is superior to flexible bronchoscopy in removal of large airway foreign bodies.1 The rigid bronchoscopy provides the ability to function as an endotracheal tube, thus allowing control of the airway and a conduit through which foreign bodies can be removed.1 Nonetheless, sometimes retrieval of foreign bodies deeper into the subsegmental bronchi cannot be achieved.1 Moreover, the required equipment or knowledgeable staff is not always available.1 Therefore, flexible bronchoscopy is an option to retrieve airway foreign bodies especially those located distal in the airway and for those medical centers without rigid bronchoscopy as is the case in our institution.

In our case, flexible bronchoscopy was performed in the OR because we predicted a difficult and prolonged retrieval in view of multiple and different-sized objects. Anesthesia Service assistance was requested anticipating need for patient sedation and intubation. We used the tripod and snare retrieval tools to remove 3 foreign objects located at the right main stem bronchus. Even though multiple attempts were made and endotracheal intubation was required, a successful retrieval with flexible bronchoscopy was performed. Moreover, cardiothoracic surgery was not required avoiding more invasive interventions with subsequent morbidity and mortality.

Conclusion

Flexible bronchoscopy is an important tool within the arsenal of the Pulmonology Service. The management of the underlying etiology also should be performed. In our case, the Psychiatry Service recommended that the patient’s medications should be administered by his mother to avoid similar events in the future. Flexible bronchoscopy can be a valuable option for foreign objects removal, especially those distally located in the lung segments as well as in those medical centers where rigid bronchoscopy is not available.

Airway foreign-body aspiration may cause no symptoms, although it can produce acute and life-threatening central airway obstruction.1 In the US, at least 2,700 people, including more than 300 children, die of foreign-body aspiration each year.2 Most foreign-body aspirations occur in children and elderly patients.3 In adults, dementia, drug intoxication, strokes, seizures, and neurologic disorders may predispose patients to aspiration.3 Some of the consequences of an aspirated object are complete or partial airway obstruction, respiratory distress and failure, pneumothorax, and hemorrhage.2 In addition, inadvertent aspiration of foreign objects in asymptomatic patients may not be evident for months, resulting in late complications as postobstructive pneumonia, bronchiectasis, or lung abscess.2

We present a case of a patient with documented schizophrenia with nonadherence to his antipsychotic medications who aspirated different objects. Flexible bronchoscopy was performed since rigid bronchoscopy is not available at our institution. Several bronchoscopy tools were required to successfully remove the objects and avoid further invasive interventions, such as cardiothoracic surgery.

Case Presentation

A 55-year-old man with schizophrenia on antipsychotics developed cough, shortness of breath, and dysphagia of 1-month of evolution. Because his symptoms worsened, his mother brought him to the emergency department. Peripheral oxygen saturation was 97% at room air. Lung auscultation was remarkable for bilateral scattered rhonchi and wheezes.

Laboratory results showed leukocytosis with neutrophilia and hypotonic hypovolemic hyponatremia.

The patient stated that he did not remember swallowing any objects, although his mother confirmed that he was not adherent with his antipsychotic medications, which could have predisposed him to aspiration secondary to possible psychotic episodes.

Piperacillin/tazobactam 4.5 g every 8 hours was started to cover anaerobic bacterial organisms causing abscess, and IV fluids were given for hypovolemia. Flexible bronchoscopy (rigid bronchoscopy is superior although not available at our institution) was planned to be performed in the operating room (OR) because we predicted a difficult and prolonged retrieval in view of multiple and different-sized objects.

A bronchoscopy was performed, showing a disk-shaped metallic foreign body at the right main stem bronchus. After multiple attempts using the tripod retrieval tool, a coin was removed (Figures 3A and 3B).

The patient was reintubated without any complications. A postprocedure chest radiograph showed the absence of foreign bodies and no pneumothorax. The patient completed IV antibiotic with piperacillin/tazobactam and supportive therapy with clinical improvement and successful extubation within 2 days. Cardiothoracic surgery was not required. Psychiatry service recommended to continue the same antipsychotic medications, administered only by his mother to assure adherence and to avoid similar future events. The patient was discharged home without any immediate complications despite having had a coin, nail, and screw aspiration (Figure 6).

Discussion

More than 50% of foreign bodies lodge at the right main stem bronchus due to the trachea’s anatomical position.2,4 In adults, foreign-body aspiration may present with nonspecific symptoms, such as cough and dyspnea.4 Other symptoms might include wheezes, chest discomfort, and sputum production. A chest radiograph is helpful as part of the initial diagnostic workup. A chest CT scan without contrast should be performed to confirm the diagnosis and to plan possible foreign-body retrieval.

Bronchoscopy is the gold standard for diagnosis and management of foreign-body aspiration.1 Rigid bronchoscopy is superior to flexible bronchoscopy in removal of large airway foreign bodies.1 The rigid bronchoscopy provides the ability to function as an endotracheal tube, thus allowing control of the airway and a conduit through which foreign bodies can be removed.1 Nonetheless, sometimes retrieval of foreign bodies deeper into the subsegmental bronchi cannot be achieved.1 Moreover, the required equipment or knowledgeable staff is not always available.1 Therefore, flexible bronchoscopy is an option to retrieve airway foreign bodies especially those located distal in the airway and for those medical centers without rigid bronchoscopy as is the case in our institution.

In our case, flexible bronchoscopy was performed in the OR because we predicted a difficult and prolonged retrieval in view of multiple and different-sized objects. Anesthesia Service assistance was requested anticipating need for patient sedation and intubation. We used the tripod and snare retrieval tools to remove 3 foreign objects located at the right main stem bronchus. Even though multiple attempts were made and endotracheal intubation was required, a successful retrieval with flexible bronchoscopy was performed. Moreover, cardiothoracic surgery was not required avoiding more invasive interventions with subsequent morbidity and mortality.

Conclusion

Flexible bronchoscopy is an important tool within the arsenal of the Pulmonology Service. The management of the underlying etiology also should be performed. In our case, the Psychiatry Service recommended that the patient’s medications should be administered by his mother to avoid similar events in the future. Flexible bronchoscopy can be a valuable option for foreign objects removal, especially those distally located in the lung segments as well as in those medical centers where rigid bronchoscopy is not available.

1. Mehta D, Mehta C, Bansal S, Singla S, Tangri N. Flexible bronchoscopic removal of a three piece foreign body from a child’s bronchus. Australas Med J. 2012;5(4):227-230.

2. Mercado JA, Rodríguez W. Occult aspiration of a chicken wishbone as a cause of hemoptysis. P R Health Sci J. 1999;18(1):71-73.

3. Robles-Arias CM, Campos-Santiago Z, Vega MT, Rosa-Cruz F, Rodríguez-Cintrón W. Aspiration of a dental tool during a crown placement procedure. Fed Pract. 2014;31(6):12-14.

4. Blanco-Ramos M, Botana-Rial M, García-Fontán E, Fernández-Villar A, Gallas-Torreira M. Update in the extraction of airway foreign bodies in adults. J Thorac Dis. 2016;8(11):3452-3456.

1. Mehta D, Mehta C, Bansal S, Singla S, Tangri N. Flexible bronchoscopic removal of a three piece foreign body from a child’s bronchus. Australas Med J. 2012;5(4):227-230.

2. Mercado JA, Rodríguez W. Occult aspiration of a chicken wishbone as a cause of hemoptysis. P R Health Sci J. 1999;18(1):71-73.

3. Robles-Arias CM, Campos-Santiago Z, Vega MT, Rosa-Cruz F, Rodríguez-Cintrón W. Aspiration of a dental tool during a crown placement procedure. Fed Pract. 2014;31(6):12-14.

4. Blanco-Ramos M, Botana-Rial M, García-Fontán E, Fernández-Villar A, Gallas-Torreira M. Update in the extraction of airway foreign bodies in adults. J Thorac Dis. 2016;8(11):3452-3456.

Misleading Diagnosis of Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis: A Clinical Concern

Sjogren syndrome (SS) is a chronic inflammatory autoimmune disorder characterized by lymphocytic infiltration of lacrimal and salivary glands causing sicca syndrome.¹ The disease can extend beyond the exocrine glands, and systemic manifestations, including vasculitis, lung, renal or neurologic involvement, can occur.² Lung disease associated with SS is more commonly seen in women aged ≥ 60 years. The most common symptoms include dry cough, chest pain, and dyspnea on exertion. Sjogren syndrome also may produce several respiratory complications, including bronchial hyperresponsiveness, bronchiolitis, bronchiectasis, pulmonary infections, pulmonary amyloidosis, pulmonary embolism, pulmonary hypertension, lymphomas, and interstitial lung diseases (ILD).² Although ILD typically occurs 5 to 10 years after the onset of SS, lung disease can precede SS.

Pulmonary involvement is associated with systemic manifestations, hypergammaglobulinemia, and anti-SSA and anti-SSB antibodies.² Laboratory tests that confirm a diagnosis of SS include antinuclear antibody (ANA), anti-Ro/SSA, and anti-La/SSB antibodies.² Pulmonary function test (PFT) results appear to reflect impairment of either the lung (restrictive syndrome) or airways (obstructive syndrome).² Imaging abnormalities may include ground-glass attenuation, subpleural small nodules, nonseptal linear opacities, interlobular septal thickening, bronchiectasis, and cysts.³ Therefore, many ILD cases show similar imaging and pathologic findings; nevertheless, they have identifiable etiology that are not idiopathic.

Case Presentation

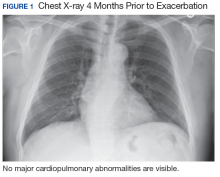

A 67-year-old man with a medical history of hypertension, peripheral vascular disease, and keratoconjunctivitis sicca (treated with eye drops) developed progressive shortness of breath, dyspnea on exertion, and weight loss (40 pounds) over the course of 6 months. A pulmonary function test showed a restrictive abnormality with decreased diffusing capacity of the lungs for carbon monoxide (eFigure available online at www.fedprac.com). A chest computed tomography (CT) scan showed the presence of significant thickening of the interlobular septi that was more pronounced in the subpleural regions of the lungs and lower lobes, which was consistent with usual interstitial pneumonia. A chest X-ray conducted 4 months prior showed no significant acute cardiopulmonary abnormalities (Figure 1). An open lung wedge biopsy revealed chronic organizing pneumonia with mild interstitial chronic inflammation, smooth muscle hypertrophy, and honeycomb changes consistent with usual interstitial pneumonia.

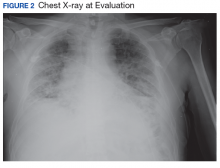

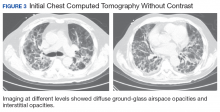

The patient had been diagnosed with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) by a private physician and started pirfenidone and oxygen therapy. Three months later the patient presented to the VA Caribbean Healthcare System in San Juan Puerto Rico when he developed an exacerbation of IPF. The patient reported having fever, chills, dry cough, night sweats, and marked shortness of breath. He was found hypoxemic (partial pressure of O2 was 50 mm Hg) and required a venturi mask set to 50% fractioned of inspired O2 to maintain a peripheral oxygen saturation around 90%. A chest X-ray showed decreased lung volume with bilateral interstitial and alveolar disease (Figure 2). Leukocytosis was present at 17×10-3/µl. The chest CT scan showed interval worsening of diffuse ground-glass airspace opacities and worsening of interstitial opacities; there

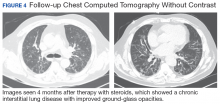

After careful clinical assessment (+ dry eyes) and radiographic pattern evaluation (diffuse bilateral interstitial and ground-glass opacities), the clinical diagnosis of IPF was queried after the patient’s rheumatologic workup came back positive for ANA and anti-Ro/SSA tests. Since the etiology of ILD was secondary to SS, pirfenidone was discontinued, and the patient was started on steroid therapy with subsequent marked clinical improvement. Parotid biopsy revealed the presence of inflammatory cells supporting the diagnosis of ILD associated to SS. The patient was discharged home on a tapering dose of steroids. Four months after therapy with steroids, a follow-up chest CT scan without contrast showed a chronic ILD with improved ground-glass opacities (Figure 4). The patient currently is in good health without oxygen supplementation.

Discussion

Diagnosis of SS is challenging, since it may mimic other conditions such as IPF. The most common type of SS-associated ILD is nonspecific interstitial pneumonia (NSIP), although usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP) can be visualized, as in this case study. Usual interstitial pneumonia

Diagnosing IPF cannot be solely based on a lung biopsy consistent with UIP. Appropriate diagnosis should consider the clinical presentation; PFT, laboratory findings (including rheumatologic workup), imaging (especially radiographic patterns), and biopsies. Moreover, the pathologic characteristic of IPF, which is UIP, can be found with other diseases, such as SS. Thus, it is important to make an accurate diagnosis to provide the appropriate treatment available. Patients with ILD associated with SS who have worsening symptoms, PFT, and radiographic abnormalities may be treated with oral prednisone (daily dose: 1 mg/kg).

Conclusion

This case highlights the importance of making an adequate diagnosis of ILD considering that available treatments differ for all possible etiologies other than IPF. This is a true clinical concern taking into account that many patients might be receiving inappropriate therapy for IPF diagnosis, as illustrated in the case study.

1. Ito I, Nagai S, Kitaichi M, et al. Pulmonary manifestations of primary Sjogren’s syndrome: a clinical, radiologic, and pathologic study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;171(6):632-638.

2. Flament T, Bigot A, Chaigne B, Henique H, Diot E, Marchand-Adam S. Pulmonary manifestations of Sjögren’s syndrome. Eur Respir Rev. 2016;25(140):110-123.

3. Koyama M, Johkoh T, Honda O, et al. Pulmonary involvement in primary Sjögren’s syndrome: spectrum of pulmonary abnormalities and computed tomography findings in 60 patients. J Thorac Imaging. 2001;16(4):290-296.

4. Wuyts WA, Cavazza A, Rossi G, Bonella F, Sverzellati N, Spagnolo P. Differential diagnosis of usual interstitial pneumonia: when is it truly idiopathic? Eur Respir Rev. 2014;23(133):308-319.

Sjogren syndrome (SS) is a chronic inflammatory autoimmune disorder characterized by lymphocytic infiltration of lacrimal and salivary glands causing sicca syndrome.¹ The disease can extend beyond the exocrine glands, and systemic manifestations, including vasculitis, lung, renal or neurologic involvement, can occur.² Lung disease associated with SS is more commonly seen in women aged ≥ 60 years. The most common symptoms include dry cough, chest pain, and dyspnea on exertion. Sjogren syndrome also may produce several respiratory complications, including bronchial hyperresponsiveness, bronchiolitis, bronchiectasis, pulmonary infections, pulmonary amyloidosis, pulmonary embolism, pulmonary hypertension, lymphomas, and interstitial lung diseases (ILD).² Although ILD typically occurs 5 to 10 years after the onset of SS, lung disease can precede SS.

Pulmonary involvement is associated with systemic manifestations, hypergammaglobulinemia, and anti-SSA and anti-SSB antibodies.² Laboratory tests that confirm a diagnosis of SS include antinuclear antibody (ANA), anti-Ro/SSA, and anti-La/SSB antibodies.² Pulmonary function test (PFT) results appear to reflect impairment of either the lung (restrictive syndrome) or airways (obstructive syndrome).² Imaging abnormalities may include ground-glass attenuation, subpleural small nodules, nonseptal linear opacities, interlobular septal thickening, bronchiectasis, and cysts.³ Therefore, many ILD cases show similar imaging and pathologic findings; nevertheless, they have identifiable etiology that are not idiopathic.

Case Presentation

A 67-year-old man with a medical history of hypertension, peripheral vascular disease, and keratoconjunctivitis sicca (treated with eye drops) developed progressive shortness of breath, dyspnea on exertion, and weight loss (40 pounds) over the course of 6 months. A pulmonary function test showed a restrictive abnormality with decreased diffusing capacity of the lungs for carbon monoxide (eFigure available online at www.fedprac.com). A chest computed tomography (CT) scan showed the presence of significant thickening of the interlobular septi that was more pronounced in the subpleural regions of the lungs and lower lobes, which was consistent with usual interstitial pneumonia. A chest X-ray conducted 4 months prior showed no significant acute cardiopulmonary abnormalities (Figure 1). An open lung wedge biopsy revealed chronic organizing pneumonia with mild interstitial chronic inflammation, smooth muscle hypertrophy, and honeycomb changes consistent with usual interstitial pneumonia.

The patient had been diagnosed with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) by a private physician and started pirfenidone and oxygen therapy. Three months later the patient presented to the VA Caribbean Healthcare System in San Juan Puerto Rico when he developed an exacerbation of IPF. The patient reported having fever, chills, dry cough, night sweats, and marked shortness of breath. He was found hypoxemic (partial pressure of O2 was 50 mm Hg) and required a venturi mask set to 50% fractioned of inspired O2 to maintain a peripheral oxygen saturation around 90%. A chest X-ray showed decreased lung volume with bilateral interstitial and alveolar disease (Figure 2). Leukocytosis was present at 17×10-3/µl. The chest CT scan showed interval worsening of diffuse ground-glass airspace opacities and worsening of interstitial opacities; there

After careful clinical assessment (+ dry eyes) and radiographic pattern evaluation (diffuse bilateral interstitial and ground-glass opacities), the clinical diagnosis of IPF was queried after the patient’s rheumatologic workup came back positive for ANA and anti-Ro/SSA tests. Since the etiology of ILD was secondary to SS, pirfenidone was discontinued, and the patient was started on steroid therapy with subsequent marked clinical improvement. Parotid biopsy revealed the presence of inflammatory cells supporting the diagnosis of ILD associated to SS. The patient was discharged home on a tapering dose of steroids. Four months after therapy with steroids, a follow-up chest CT scan without contrast showed a chronic ILD with improved ground-glass opacities (Figure 4). The patient currently is in good health without oxygen supplementation.

Discussion

Diagnosis of SS is challenging, since it may mimic other conditions such as IPF. The most common type of SS-associated ILD is nonspecific interstitial pneumonia (NSIP), although usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP) can be visualized, as in this case study. Usual interstitial pneumonia

Diagnosing IPF cannot be solely based on a lung biopsy consistent with UIP. Appropriate diagnosis should consider the clinical presentation; PFT, laboratory findings (including rheumatologic workup), imaging (especially radiographic patterns), and biopsies. Moreover, the pathologic characteristic of IPF, which is UIP, can be found with other diseases, such as SS. Thus, it is important to make an accurate diagnosis to provide the appropriate treatment available. Patients with ILD associated with SS who have worsening symptoms, PFT, and radiographic abnormalities may be treated with oral prednisone (daily dose: 1 mg/kg).

Conclusion

This case highlights the importance of making an adequate diagnosis of ILD considering that available treatments differ for all possible etiologies other than IPF. This is a true clinical concern taking into account that many patients might be receiving inappropriate therapy for IPF diagnosis, as illustrated in the case study.

Sjogren syndrome (SS) is a chronic inflammatory autoimmune disorder characterized by lymphocytic infiltration of lacrimal and salivary glands causing sicca syndrome.¹ The disease can extend beyond the exocrine glands, and systemic manifestations, including vasculitis, lung, renal or neurologic involvement, can occur.² Lung disease associated with SS is more commonly seen in women aged ≥ 60 years. The most common symptoms include dry cough, chest pain, and dyspnea on exertion. Sjogren syndrome also may produce several respiratory complications, including bronchial hyperresponsiveness, bronchiolitis, bronchiectasis, pulmonary infections, pulmonary amyloidosis, pulmonary embolism, pulmonary hypertension, lymphomas, and interstitial lung diseases (ILD).² Although ILD typically occurs 5 to 10 years after the onset of SS, lung disease can precede SS.

Pulmonary involvement is associated with systemic manifestations, hypergammaglobulinemia, and anti-SSA and anti-SSB antibodies.² Laboratory tests that confirm a diagnosis of SS include antinuclear antibody (ANA), anti-Ro/SSA, and anti-La/SSB antibodies.² Pulmonary function test (PFT) results appear to reflect impairment of either the lung (restrictive syndrome) or airways (obstructive syndrome).² Imaging abnormalities may include ground-glass attenuation, subpleural small nodules, nonseptal linear opacities, interlobular septal thickening, bronchiectasis, and cysts.³ Therefore, many ILD cases show similar imaging and pathologic findings; nevertheless, they have identifiable etiology that are not idiopathic.

Case Presentation

A 67-year-old man with a medical history of hypertension, peripheral vascular disease, and keratoconjunctivitis sicca (treated with eye drops) developed progressive shortness of breath, dyspnea on exertion, and weight loss (40 pounds) over the course of 6 months. A pulmonary function test showed a restrictive abnormality with decreased diffusing capacity of the lungs for carbon monoxide (eFigure available online at www.fedprac.com). A chest computed tomography (CT) scan showed the presence of significant thickening of the interlobular septi that was more pronounced in the subpleural regions of the lungs and lower lobes, which was consistent with usual interstitial pneumonia. A chest X-ray conducted 4 months prior showed no significant acute cardiopulmonary abnormalities (Figure 1). An open lung wedge biopsy revealed chronic organizing pneumonia with mild interstitial chronic inflammation, smooth muscle hypertrophy, and honeycomb changes consistent with usual interstitial pneumonia.

The patient had been diagnosed with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) by a private physician and started pirfenidone and oxygen therapy. Three months later the patient presented to the VA Caribbean Healthcare System in San Juan Puerto Rico when he developed an exacerbation of IPF. The patient reported having fever, chills, dry cough, night sweats, and marked shortness of breath. He was found hypoxemic (partial pressure of O2 was 50 mm Hg) and required a venturi mask set to 50% fractioned of inspired O2 to maintain a peripheral oxygen saturation around 90%. A chest X-ray showed decreased lung volume with bilateral interstitial and alveolar disease (Figure 2). Leukocytosis was present at 17×10-3/µl. The chest CT scan showed interval worsening of diffuse ground-glass airspace opacities and worsening of interstitial opacities; there

After careful clinical assessment (+ dry eyes) and radiographic pattern evaluation (diffuse bilateral interstitial and ground-glass opacities), the clinical diagnosis of IPF was queried after the patient’s rheumatologic workup came back positive for ANA and anti-Ro/SSA tests. Since the etiology of ILD was secondary to SS, pirfenidone was discontinued, and the patient was started on steroid therapy with subsequent marked clinical improvement. Parotid biopsy revealed the presence of inflammatory cells supporting the diagnosis of ILD associated to SS. The patient was discharged home on a tapering dose of steroids. Four months after therapy with steroids, a follow-up chest CT scan without contrast showed a chronic ILD with improved ground-glass opacities (Figure 4). The patient currently is in good health without oxygen supplementation.

Discussion

Diagnosis of SS is challenging, since it may mimic other conditions such as IPF. The most common type of SS-associated ILD is nonspecific interstitial pneumonia (NSIP), although usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP) can be visualized, as in this case study. Usual interstitial pneumonia

Diagnosing IPF cannot be solely based on a lung biopsy consistent with UIP. Appropriate diagnosis should consider the clinical presentation; PFT, laboratory findings (including rheumatologic workup), imaging (especially radiographic patterns), and biopsies. Moreover, the pathologic characteristic of IPF, which is UIP, can be found with other diseases, such as SS. Thus, it is important to make an accurate diagnosis to provide the appropriate treatment available. Patients with ILD associated with SS who have worsening symptoms, PFT, and radiographic abnormalities may be treated with oral prednisone (daily dose: 1 mg/kg).

Conclusion

This case highlights the importance of making an adequate diagnosis of ILD considering that available treatments differ for all possible etiologies other than IPF. This is a true clinical concern taking into account that many patients might be receiving inappropriate therapy for IPF diagnosis, as illustrated in the case study.

1. Ito I, Nagai S, Kitaichi M, et al. Pulmonary manifestations of primary Sjogren’s syndrome: a clinical, radiologic, and pathologic study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;171(6):632-638.

2. Flament T, Bigot A, Chaigne B, Henique H, Diot E, Marchand-Adam S. Pulmonary manifestations of Sjögren’s syndrome. Eur Respir Rev. 2016;25(140):110-123.

3. Koyama M, Johkoh T, Honda O, et al. Pulmonary involvement in primary Sjögren’s syndrome: spectrum of pulmonary abnormalities and computed tomography findings in 60 patients. J Thorac Imaging. 2001;16(4):290-296.

4. Wuyts WA, Cavazza A, Rossi G, Bonella F, Sverzellati N, Spagnolo P. Differential diagnosis of usual interstitial pneumonia: when is it truly idiopathic? Eur Respir Rev. 2014;23(133):308-319.

1. Ito I, Nagai S, Kitaichi M, et al. Pulmonary manifestations of primary Sjogren’s syndrome: a clinical, radiologic, and pathologic study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;171(6):632-638.

2. Flament T, Bigot A, Chaigne B, Henique H, Diot E, Marchand-Adam S. Pulmonary manifestations of Sjögren’s syndrome. Eur Respir Rev. 2016;25(140):110-123.

3. Koyama M, Johkoh T, Honda O, et al. Pulmonary involvement in primary Sjögren’s syndrome: spectrum of pulmonary abnormalities and computed tomography findings in 60 patients. J Thorac Imaging. 2001;16(4):290-296.

4. Wuyts WA, Cavazza A, Rossi G, Bonella F, Sverzellati N, Spagnolo P. Differential diagnosis of usual interstitial pneumonia: when is it truly idiopathic? Eur Respir Rev. 2014;23(133):308-319.