User login

Reducing Inappropriate PPIs at Discharge

In 2013, there were more than 15 million Americans receiving proton pump inhibitors (PPIs),[1] with an associated drug cost of nearly $79 billion between 2007 and 2011.2 PPI use is reaching epidemic proportions, likely due to the medicalization of gastrointestinal symptoms coupled with pervasive marketing and academic detailing being performed by the pharmaceutical industry.

Although PPIs are generally considered safe, they are not as innocuous as many physicians believe. In 2011 and 2012, the US Food and Drug Administration and Health Canada, respectively, issued safety advisories regarding the use of these medications related to Clostridium difficile, fracture risk, and electrolyte derangement.[3, 4, 5, 6] There have also been numerous other harmful associations reported,[7, 8, 9, 10] suggesting it would be prudent to follow Health Canada's advice that: PPIs should be prescribed at the lowest dose and shortest duration of therapy appropriate to the condition being treated.[4] In many cases this implies stopping the PPI after an appropriate duration of therapy or attempting nonpharmacological or H2‐blocker therapy instead.

Nevertheless, despite numerous cautionary publications, PPI use for nonevidence‐based indications remains common. Because they are generally thought of as outpatient medications, PPIs are frequently continued in hospitalized patients, and inappropriate outpatient therapy is rarely addressed.[11, 12, 13] Likewise, inappropriate de novo use can also be observed during hospitalization and may continue on discharge.[13, 14, 15] Hospitalization may consequently present an opportunity to employ meaningful interventions targeting outpatient medication use.[16] We developed an opportune inpatient intervention targeting inappropriate PPI therapy.

Our study had 2 aims: first, to determine the magnitude of the problem in a contemporary Canadian medical inpatient population, and second, we sought to leverage the inpatient admission as an opportunity to promote change when the patient returned to the community through the application of an educational and web‐based quality‐improvement (QI) intervention.

METHODS

Patient Inclusion

Between January 2012 and December 2012, we included all consecutively admitted patients on our 46‐bed general medical clinical teaching unit belonging to a 417‐bed tertiary care teaching hospital in Montreal, Canada. There were no exclusion criteria. This time period was divided into 2 blocks: the preintervention control period from January 1 to June 3 and the intervention period from June 4 to December 16.

Intervention and Implementation Strategy

At the start of each academic period, we presented a 20‐minute information session on the benefits and harms of PPI use (see Supporting Information, Appendix, in the online version of this article). The unit's medical residents and faculty attended these rounds. The presentation described the project, consensus‐derived indications for PPI use, and potential adverse events attributable to PPIs (see Table 1 for indications based on internal consensus and similar studies[17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23]). All other indications were considered nonevidence based. At the end of the month, teams were given feedback on indications they provided using the Web tool and the proportion of patients they discharged on a PPI with and without indication.

|

| 1. Gastric or duodenal ulcer within the past 3 months |

| 2. Pathological hypersecretory conditions |

| 3. Gastroesophageal reflux disease with exacerbations within the last 3 months not responsive to H2 blockers and nonpharmacologic techniques |

| 4. Erosive esophagitis |

| 5. Recurring symptoms recently associated with severe indigestion within the last 3 months not responsive to H2 blocker or nonpharmacologic techniques |

| 6. Helicobacter pylori eradication |

| 7. Dual antiplatelet therapy |

| 8. Antiplatelet therapy with anticoagulants |

| 9. Antiplatelet or anticoagulant therapy with history of previous complicated ulcer |

| 10. Antiplatelet or NSAID with 2 of the following: concomitant systemic corticosteroids, age over 60 years, previous uncomplicated ulcer, concomitant NSAID, or antiplatelet/anticoagulant |

The process of evaluating and stopping PPIs was voluntary. Housestaff were encouraged to evaluate PPIs when ordering admission medications and upon preparing exit prescriptions. This was an opt‐in intervention. Once a patient on a PPI was identified, typically on admission to the unit, the indication for use could then be evaluated using the online tool, which was accessible on the internet via a link on all unit computers (see Supporting Information, Appendix, in the online version of this article).

The Web‐based tool was designed to be simple and informative. Users of the tool input anonymous data including comorbidities (check boxes provided). The tool collected the indication for PPI use, with available options including: the consensus‐derived evidence‐based indications, no identified indication, or free text. This was done purposefully to remind the teams of the consensus indications, with the goal that in choosing no identified indication the resident would consider cessation of unnecessary PPIs. The final step in the tool, discharge plan, presented the option of stopping the PPI in the absence of a satisfactory indication. We hypothesized that selecting this option would serve as an informal commitment to discontinuing the PPI during the creation of the discharge prescription; however, the tool was not automatically linked to these prescriptions.

If a home prescription was discontinued, the patient was counselled by the treating team and provided with an educational letter (see Supporting Information, Appendix, in the online version of this article), which was fastened to their discharge summary and given to the patient for delivery to all of their usual outpatient physician(s).

The design of the online tool was such that residents were to evaluate PPI use that would continue postdischarge from the hospital, rather than PPI use limited to the period of hospitalization.

Data Collection and Statistical Analysis

Data on baseline demographics and the specific indications for PPI use were collected through clinician interaction with the online tool. The proportion of patients on a PPI was ascertained through a separate data extraction of electronic discharge prescriptions. These involved medication reconciliation for all outpatient medications including whether or not they were continued, modified, or stopped. Thus, we could determine at discharge whether outpatient PPIs were continued or stopped or if a new PPI was initiated.

The proportion of patients admitted from home already receiving a PPI, those who received a new prescription for a PPI at discharge, and those whose PPI was stopped during admission were compared before and after the intervention using segmented regression analysis of an interrupted time series (see Supporting Information, Appendix, in the online version of this article).[24]

Post Hoc Power Calculations

For the pre‐post comparisons, given the preintervention number of admissions, proportions of PPI use in the community, new PPI use, and PPI discontinuation rates we would have had an 80% power to detect changes of 8.5%, 5%, and 5.5%, respectively.

Ethics

The McGill University Health Centre research ethics board approved this study. Informed consent was waived as the intervention was deemed to be best practice, and data collected were anonymous. Clinical consent was obtained by the treating team for all care decisions.

Funding

This initiative was conducted without any funding.

RESULTS

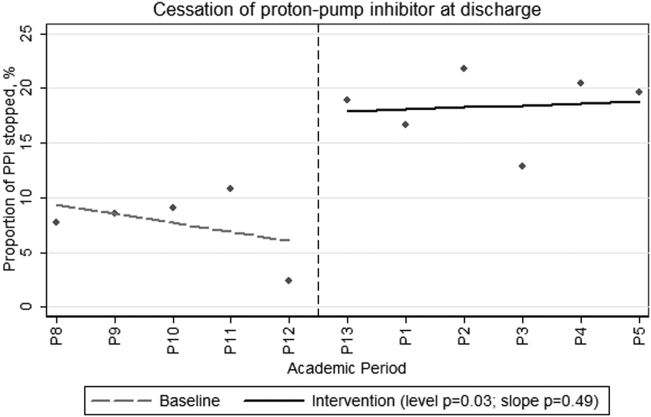

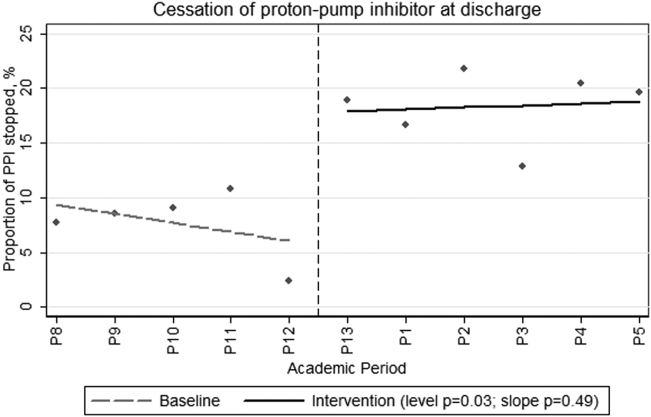

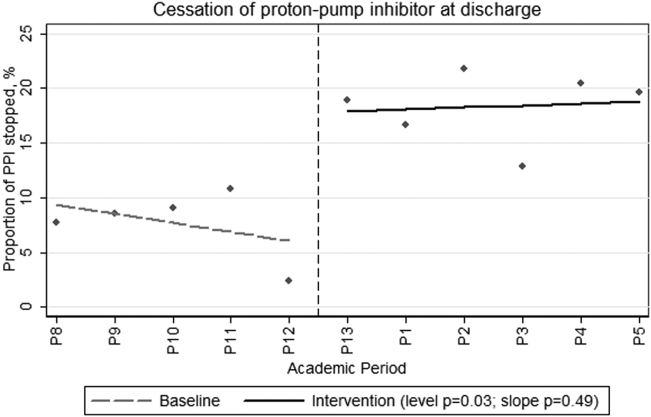

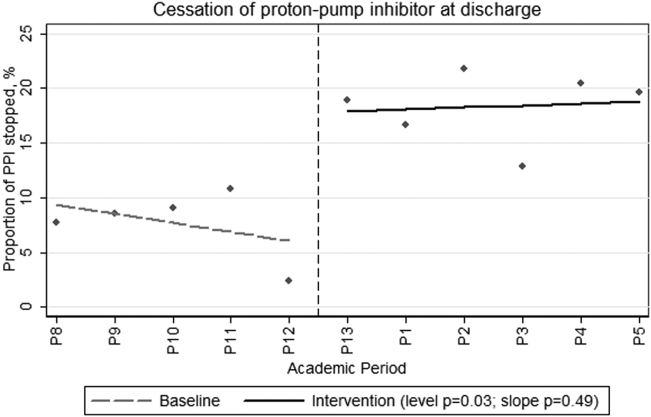

During the preintervention period, 464 patients were admitted, of whom 209 (45%) were taking a PPI prior to admission. During their hospitalization, an additional 53 patients (21% of nonusers) were newly prescribed a PPI that was continued at discharge. During the intervention period, a total of 640 patients were admitted, of whom 281 (44%) were taking a PPI prior to admission. During their hospitalization, 60 patients (17% of nonusers) were newly prescribed a PPI that was continued at discharge. Neither the monthly proportions admitted on PPIs from prior to admission (level P=0.59, slope P=0.46) or those newly initiated on a PPI (level P=0.36, slope P=0.18) were significantly different before compared to after the intervention. However, there was both a clinically and statistically significant difference in the proportion of preadmission PPIs that were discontinued at hospital discharge from a monthly mean of 7.7% (or 16/209) before intervention to 18.5% (or 52/281) afterward (Figure 1; level P=0.03, slope P=0.48).

During the intervention period, our teams prospectively captured PPI indications and patient comorbidities for 54% (152/281) of the patients admitted on a PPI using the online assessment tool. The baseline characteristics of the population in whom the online tool was applied are shown in Table 2. These patients had a mean age of 69.6 years, and 49% were male. Thirty‐two percent had diabetes, 20% had chronic renal insufficiency, and 13% had experienced a gastrointestinal hemorrhage within the 3 months prior to admission. It was frequent for PPI users to receive systemic antibiotics (44%) or to have diagnoses potentially associated with PPI use such as community‐acquired pneumonia (25%) or C difficile (11%).

| Characteristic | Value |

|---|---|

| |

| Age, y, mean (SD) | 69.615.1 |

| Male gender, N (%) | 75 (49) |

| Initiation of PPI, N (%) | |

| Prior to hospitalization | 127 (84) |

| During hospitalization | 10 (6) |

| In ICU | 7 (4) |

| In ER | 8 (5) |

| Comorbidities, N (%) | |

| Diabetes mellitus | 48 (32) |

| Chronic renal failure, GFR <45 | 29 (20) |

| GI bleed in the last 3 months | 20 (13) |

| No comorbidities | 11 (7) |

| Medications, N (%) | |

| Current antiplatelet agent | 67 (44) |

| Current corticosteroid use | 40 (26) |

| Current therapeutic anticoagulation | 35 (23) |

| Current NSAID use | 13 (8.5) |

| Current bisphosphonate | 13 (8.5) |

| Potential contraindications to PPI, N (%) | |

| Current antibiotic therapy | 67 (44) |

| Pneumonia | 38 (25) |

| Clostridium difficile infection ever | 16 (11) |

| Clostridium difficile infection on present admission | 9 (6) |

Fifty‐four percent (82/152) of patients in whom the online tool was applied had an evidence‐based indication (Table 3). The most common indication for PPI prescription was the receipt of antiplatelet/anticoagulant or nonsteroidal anti‐inflammatory drug with 2 other known risk factors for upper gastrointestinal bleeding (20%). In the remaining 46% (70/152) of patients, the prescription of a PPI was deemed nonevidence based. Of these, 34 (49%) had their PPI discontinued. When patients were approached to discontinue therapy, the rate of success was high, with only 2 refusals.

| Indications | N (%) |

|---|---|

| |

| Approved indications for therapy | |

| Antiplatelet or NSAID with 2 of the following: age >60 years, systemic corticosteroids, previous uncomplicated ulcer, NSAID, or antiplatelet/anticoagulant | 28 (20) |

| Gastric or duodenal ulcer within the past 3 months | 23 (15) |

| Antiplatelet therapy with anticoagulants | 17 (11) |

| GERD with exacerbations within the last 3 months | 17 (11) |

| Dual antiplatelet therapy | 7 (5) |

| Pathological hypersecretory conditions | 0 |

| Helicobactor pylori eradication | 0 |

| Total with consensus indications | 79 (54) |

| Other described indications for therapy | |

| No indication identified | 46 (30) |

| Othera | 22 (14) |

| Palliative patients GERD prophylaxis | 5 (3) |

| Total without consensus indications | 70 (46) |

DISCUSSION

In this prospective intervention, 44% of patients admitted to an acute‐care medical ward were prescribed a PPI prior to their admission. In the subgroup of patients for whom the indication for PPI use was recorded through our online tool, less than half had an evidence‐based indication for ongoing therapy. Our intervention was successful in increasing the proportion of patients in whom preadmission PPI prescriptions were stopped at discharge from an average of 7.7% in the preintervention phase to 18.5% during the intervention. This intervention is novel in that we were able to reduce active community prescriptions for PPIs in patients without obvious indication by nearly 50%.

Our population's rates of PPI prescription were consistent with previous reports,[11, 12, 13, 15, 25, 26, 27, 28] and it is clear that many hospitalized patients continue their PPIs at discharge without clear indications. We propose that hospitalization can serve as an opportunity to reassess the necessity of continuous PPI use. Previous systematic attempts to reduce inappropriate PPI prescriptions in hospital have met with varied success. Several of these studies were unable to achieve a demonstrable effect.[23, 29, 30, 31] In contrast, Hamzat et al.[30] described a successful educational intervention targeting inpatients on a geriatric ward. A 4‐week educational strategy was employed, and they were able to discontinue PPIs in 10 of 60 (17%) patients without indication during a limited period of study. Another successful intervention by Gupta et al.[32] involved a before‐and‐after study combining a half‐hour physician education session with the introduction of a medication reconciliation tool. They showed a decrease in inappropriate discharge prescriptions of 50%. Not only did our study demonstrate an equally sizable reduction in inappropriate discharge prescriptions, but we also employed a more methodologically sound time‐series analysis to control for unmeasured contemporaneous factors such as rotating staff practices or monthly differences in patient composition. We demonstrated an immediate and sustained improvement in performance that lasted over 6 months. Furthermore, in contrast to other interventions, which addressed inappropriate inpatient use persisting on discharge, our intervention also addressed the appropriateness of PPI use that antedated hospitalization.

There are common themes to the successful programs. The more time spent educating and reminding the prescribing physicians, the more successful the intervention. Nonetheless, we believe our intervention is not onerous or overly time consuming. We performed a short presentation each month to educate rotating physicians, and the tool took less than 1 minute to complete once the information on PPI indication was available. Frequent education sessions may be initially necessary given the comfort that many physicians have developed in prescribing PPIs. A further prerequisite for success may be a familiarity with PPI indications and potential adverse effects. Without this, the intervention may not show a demonstrable effect, as was seen in a study of pulmonologists.[23] We hypothesize that some subspecialist physicians may not have the same appreciation of the adverse effects of PPIs nor the confidence to stop them when not indicated, as compared to general internists or hospitalists.

The proportion of patients with newly initiated PPIs at discharge decreased after the intervention, but this did not reach statistical significance. Our study's power may have precluded this. However, we had also previously put in place unpublished interventions to diminish inappropriate gastric prophylaxis in the hospital, which may have diminished the effect of this intervention.

Unfortunately, although we demonstrated a clinically significant effect on PPI exit prescription rates, we still found that nearly half of the patients who were evaluated using the online tool were discharged on PPIs despite our physicians' acknowledgment that they had no identifiable indication. It is possible that clinicians do not feel comfortable stopping these medications, owing to a fear that there is an indication that they are not aware of. In certain cases, it is possible that a reappraisal of the benefits, risks, and costs might reassure the clinician that they could safely stop the drug; however, therapeutic inertia is often hard to overcome.

Limitations

Our single‐center study occurred over a limited time period and examined a sample of patients that were assessed based on convenience. Other limitations included the uptake of the online tool, which was only 54% of patients on a PPI. In particular, few patients who were newly started on a PPI had the online tool applied. This is likely because the tool was filled out on a volunteer basis and was applied most routinely during the admission medication reconciliation process. There were a number of other reasons why the tool was underused, including having the inpatient teams responsible for the data collection despite preexisting demands on their time and the lack of data from patients who were admitted and discharged before a thorough review of the indication for PPI use could take place. However, despite the incomplete use of the online tool, the demographics of patients who were assessed are similar to our usual patient population. As such, we believe the data captured are representative. Furthermore, despite the tool being underused, there remained a clearly objectified reduction in PPI exit prescriptions that occurred immediately postintervention and persisted throughout the entire period of study. Although our teams were not universally using the Web‐tool, it was clear that they were influenced by the project and were stopping unnecessary therapy.

Additionally, the absence of postdischarge follow‐up is also an important limitation. We had originally planned to audit all patients whose PPIs were stopped at 3 months postdischarge but were not systematically able to do so. We did, however, obtain a 1‐time convenience sample interview midway through the intervention. At that time, of 18 patients interviewed, all but 1 remained off of their PPI at 3 months postdischarge. The 1 restart was for reflux symptoms without a preceding trial of lifestyle therapy or H2 blocker.

One final limitation of this study design is that the implementation portion of the intervention took place at the beginning of the academic year. Trainees at the beginning of the year might differ from trainees at the end of the year in that they are more receptive to an educational intervention and less firmly fixed in their practice patterns. If one is considering implementing a similar strategy in their academic institution, we recommend doing so at the start of the academic year to capture the interest of new trainees, maximize the intervention's effectiveness, and establish good habits early in training.

CONCLUSION

We have demonstrated that in medical inpatients, both PPI use and misuse remain common; however, with a combined educational and Web‐based QI intervention, we could successfully decrease inappropriate exit prescriptions. Hospitalization, particularly at academic centers, should serve as an important point of contact for residents in training and expert faculty physicians to reconsider and rationalize patient medications. We should take the opportunity to engender a culture of responsibility for all of the medications that we represcribe at discharge, including an appraisal of the relevant harms and benefits, particularly when a medication is potentially unnecessary. We ought to then communicate the rationale for any changes to our community partners to maintain continuity of care. In this way, hospitalists can help treat the prescription indigestion that has become a common affliction in modern medicine.

Disclosure

Nothing to report.

- IMS Institute for Healthcare Informatics. Medicine Use and Shifting Costs of Healthcare. 2014. Available at: http://www.imshealth.com/deployedfiles/imshealth/Global/Content/Corporate/IMS%20Health%20Institute/Reports/Secure/IIHI_US_Use_of_Meds_for_2013.pdf. Accessed September 26, 2014.

- , , . National use of proton pump inhibitors from 2007 to 2011. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(11):1856–1858.

- Health Canada. Proton Pump Inhibitors (antacids): Possible Risk of Clostridium difficile‐Associated Diarrhea. 2012. Available at: http://www.healthycanadians.gc.ca/recall‐alert‐rappel‐avis/hc‐sc/2012/13651a‐eng.php. Accessed February 16, 2015.

- Health Canada. Proton Pump Inhibitors: Hypomagnesemia Accompanied by Hypocalcemia and Hypokalemia. 2011. Available at: http://www.hc‐sc.gc.ca/dhp‐mps/medeff/bulletin/carn‐bcei_v21n3‐eng.php#_Proton_pump_inhibitors. Accessed February 16, 2015.

- US Food and Drug Administration. FDA Drug Safety Communication: Possible Increased Risk of Fractures of the Hip, Wrist, and Spine With the Use of Proton Pump Inhibitors. 2012. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/PostmarketDrugSafetyInformationforPatientsandProviders/ucm213206.htm. Accessed February 15, 2015.

- US Food and Drug Administration. FDA Drug Safety Communication: Clostridium difficile‐Associated Diarrhea Can Be Associated With Stomach Acid Drugs Known as Proton Pump Inhibitors (PPIs). 2012. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/drugs/drugsafety/ucm290510.htm. Accessed February 15, 2015.

- , , . Meta‐analysis: proton pump inhibitor use and the risk of community‐acquired pneumonia. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;31(11):1165–1177.

- , , , et al. Proton pump inhibitors and risk of 1‐year mortality and rehospitalization in older patients discharged from acute care hospitals. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(7):518–523.

- , , , . Acid‐suppressive medication use and the risk for hospital‐acquired pneumonia. JAMA. 2009;301(20):2120–2128.

- , , , et al. Proton pump inhibitors and functional decline in older adults discharged from acute care hospitals. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014;62(6):1110–1115.

- , , , , . Do hospitalists overuse proton pump inhibitors? Data from a contemporary cohort. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(11):731–733.

- , , , , , . Inappropriate prescribing of proton pump inhibitors in hospitalized patients. J Hosp Med. 2012;7(5):421–425.

- , , , , . Potential costs of inappropriate use of proton pump inhibitors. Am J Med Sci. 2014;347(6):446–451.

- , , , . Long‐term use of acid suppression started inappropriately during hospitalization. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;21(10):1203–1209.

- , , , , , . Continuation of proton pump inhibitors from hospital to community. Pharm World Sci. 2006;28(4):189–193.

- , , , , , . Hospitalist and primary care physician perspectives on medication management of chronic conditions for hospitalized patients. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(5):303–309.

- , , , et al. Antibacterial treatment of gastric ulcers associated with Helicobacter pylori. N Engl J Med. 1995;332(3):139–142.

- , , , et al. Effect of intravenous omeprazole on recurrent bleeding after endoscopic treatment of bleeding peptic ulcers. N Engl J Med. 2000;343(5):310–316.

- , , , et al. Lansoprazole for the prevention of recurrences of ulcer complications from long‐term low‐dose aspirin use. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(26):2033–2038.

- , . American College of Gastroenterology guideline on the management of Helicobacter pylori infection. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102(8):1808–1825.

- , , . Guidelines for prevention of NSAID‐related ulcer complications. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104(3):728–738.

- , , , Canadian consensus guidelines on long‐term nonsteroidal anti‐inflammatory drug therapy and the need for gastroprotection: benefits versus risks. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009;29(5):481–496.

- , , , et al., The effects of guideline implementation for proton pump inhibitor prescription on two pulmonary medicine wards. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009;29(2):213–221.

- , , , . Segmented regression analysis of interrupted time series studies in medication use research. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2002;27(4):299–309.

- , , . Overuse of acid‐suppressive therapy in hospitalized patients. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95(11):3118–3122.

- , , , . Proton pump inhibitors: a survey of prescribing in an Irish general hospital. Int J Clin Pract. 2005;59(1):31–34.

- , , . Overuse of proton pump inhibitors. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2000;25(5):333–340.

- , , , et al. Prevalence and appropriateness of drug prescriptions for peptic ulcer and gastro‐esophageal reflux disease in a cohort of hospitalized elderly. Eur J Intern Med. 2011;22(2):205–210.

- , , , . Inappropriate prescribing of proton pump inhibitors in primary care. Postgrad Med J. 2007;83(975):66–68.

- , , , , , . Inappropriate prescribing of proton pump inhibitors in older patients: effects of an educational strategy. Drugs Aging. 2012;29(8):681–690.

- , , , . Impact of academic detailing on proton pump inhibitor prescribing behaviour in a community hospital. Can Pharm J (Ott). 2011;144(2):66–71.

- , , , , , . Decreased acid suppression therapy overuse after education and medication reconciliation. Int J Clin Pract. 2013;67(1):60–65.

In 2013, there were more than 15 million Americans receiving proton pump inhibitors (PPIs),[1] with an associated drug cost of nearly $79 billion between 2007 and 2011.2 PPI use is reaching epidemic proportions, likely due to the medicalization of gastrointestinal symptoms coupled with pervasive marketing and academic detailing being performed by the pharmaceutical industry.

Although PPIs are generally considered safe, they are not as innocuous as many physicians believe. In 2011 and 2012, the US Food and Drug Administration and Health Canada, respectively, issued safety advisories regarding the use of these medications related to Clostridium difficile, fracture risk, and electrolyte derangement.[3, 4, 5, 6] There have also been numerous other harmful associations reported,[7, 8, 9, 10] suggesting it would be prudent to follow Health Canada's advice that: PPIs should be prescribed at the lowest dose and shortest duration of therapy appropriate to the condition being treated.[4] In many cases this implies stopping the PPI after an appropriate duration of therapy or attempting nonpharmacological or H2‐blocker therapy instead.

Nevertheless, despite numerous cautionary publications, PPI use for nonevidence‐based indications remains common. Because they are generally thought of as outpatient medications, PPIs are frequently continued in hospitalized patients, and inappropriate outpatient therapy is rarely addressed.[11, 12, 13] Likewise, inappropriate de novo use can also be observed during hospitalization and may continue on discharge.[13, 14, 15] Hospitalization may consequently present an opportunity to employ meaningful interventions targeting outpatient medication use.[16] We developed an opportune inpatient intervention targeting inappropriate PPI therapy.

Our study had 2 aims: first, to determine the magnitude of the problem in a contemporary Canadian medical inpatient population, and second, we sought to leverage the inpatient admission as an opportunity to promote change when the patient returned to the community through the application of an educational and web‐based quality‐improvement (QI) intervention.

METHODS

Patient Inclusion

Between January 2012 and December 2012, we included all consecutively admitted patients on our 46‐bed general medical clinical teaching unit belonging to a 417‐bed tertiary care teaching hospital in Montreal, Canada. There were no exclusion criteria. This time period was divided into 2 blocks: the preintervention control period from January 1 to June 3 and the intervention period from June 4 to December 16.

Intervention and Implementation Strategy

At the start of each academic period, we presented a 20‐minute information session on the benefits and harms of PPI use (see Supporting Information, Appendix, in the online version of this article). The unit's medical residents and faculty attended these rounds. The presentation described the project, consensus‐derived indications for PPI use, and potential adverse events attributable to PPIs (see Table 1 for indications based on internal consensus and similar studies[17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23]). All other indications were considered nonevidence based. At the end of the month, teams were given feedback on indications they provided using the Web tool and the proportion of patients they discharged on a PPI with and without indication.

|

| 1. Gastric or duodenal ulcer within the past 3 months |

| 2. Pathological hypersecretory conditions |

| 3. Gastroesophageal reflux disease with exacerbations within the last 3 months not responsive to H2 blockers and nonpharmacologic techniques |

| 4. Erosive esophagitis |

| 5. Recurring symptoms recently associated with severe indigestion within the last 3 months not responsive to H2 blocker or nonpharmacologic techniques |

| 6. Helicobacter pylori eradication |

| 7. Dual antiplatelet therapy |

| 8. Antiplatelet therapy with anticoagulants |

| 9. Antiplatelet or anticoagulant therapy with history of previous complicated ulcer |

| 10. Antiplatelet or NSAID with 2 of the following: concomitant systemic corticosteroids, age over 60 years, previous uncomplicated ulcer, concomitant NSAID, or antiplatelet/anticoagulant |

The process of evaluating and stopping PPIs was voluntary. Housestaff were encouraged to evaluate PPIs when ordering admission medications and upon preparing exit prescriptions. This was an opt‐in intervention. Once a patient on a PPI was identified, typically on admission to the unit, the indication for use could then be evaluated using the online tool, which was accessible on the internet via a link on all unit computers (see Supporting Information, Appendix, in the online version of this article).

The Web‐based tool was designed to be simple and informative. Users of the tool input anonymous data including comorbidities (check boxes provided). The tool collected the indication for PPI use, with available options including: the consensus‐derived evidence‐based indications, no identified indication, or free text. This was done purposefully to remind the teams of the consensus indications, with the goal that in choosing no identified indication the resident would consider cessation of unnecessary PPIs. The final step in the tool, discharge plan, presented the option of stopping the PPI in the absence of a satisfactory indication. We hypothesized that selecting this option would serve as an informal commitment to discontinuing the PPI during the creation of the discharge prescription; however, the tool was not automatically linked to these prescriptions.

If a home prescription was discontinued, the patient was counselled by the treating team and provided with an educational letter (see Supporting Information, Appendix, in the online version of this article), which was fastened to their discharge summary and given to the patient for delivery to all of their usual outpatient physician(s).

The design of the online tool was such that residents were to evaluate PPI use that would continue postdischarge from the hospital, rather than PPI use limited to the period of hospitalization.

Data Collection and Statistical Analysis

Data on baseline demographics and the specific indications for PPI use were collected through clinician interaction with the online tool. The proportion of patients on a PPI was ascertained through a separate data extraction of electronic discharge prescriptions. These involved medication reconciliation for all outpatient medications including whether or not they were continued, modified, or stopped. Thus, we could determine at discharge whether outpatient PPIs were continued or stopped or if a new PPI was initiated.

The proportion of patients admitted from home already receiving a PPI, those who received a new prescription for a PPI at discharge, and those whose PPI was stopped during admission were compared before and after the intervention using segmented regression analysis of an interrupted time series (see Supporting Information, Appendix, in the online version of this article).[24]

Post Hoc Power Calculations

For the pre‐post comparisons, given the preintervention number of admissions, proportions of PPI use in the community, new PPI use, and PPI discontinuation rates we would have had an 80% power to detect changes of 8.5%, 5%, and 5.5%, respectively.

Ethics

The McGill University Health Centre research ethics board approved this study. Informed consent was waived as the intervention was deemed to be best practice, and data collected were anonymous. Clinical consent was obtained by the treating team for all care decisions.

Funding

This initiative was conducted without any funding.

RESULTS

During the preintervention period, 464 patients were admitted, of whom 209 (45%) were taking a PPI prior to admission. During their hospitalization, an additional 53 patients (21% of nonusers) were newly prescribed a PPI that was continued at discharge. During the intervention period, a total of 640 patients were admitted, of whom 281 (44%) were taking a PPI prior to admission. During their hospitalization, 60 patients (17% of nonusers) were newly prescribed a PPI that was continued at discharge. Neither the monthly proportions admitted on PPIs from prior to admission (level P=0.59, slope P=0.46) or those newly initiated on a PPI (level P=0.36, slope P=0.18) were significantly different before compared to after the intervention. However, there was both a clinically and statistically significant difference in the proportion of preadmission PPIs that were discontinued at hospital discharge from a monthly mean of 7.7% (or 16/209) before intervention to 18.5% (or 52/281) afterward (Figure 1; level P=0.03, slope P=0.48).

During the intervention period, our teams prospectively captured PPI indications and patient comorbidities for 54% (152/281) of the patients admitted on a PPI using the online assessment tool. The baseline characteristics of the population in whom the online tool was applied are shown in Table 2. These patients had a mean age of 69.6 years, and 49% were male. Thirty‐two percent had diabetes, 20% had chronic renal insufficiency, and 13% had experienced a gastrointestinal hemorrhage within the 3 months prior to admission. It was frequent for PPI users to receive systemic antibiotics (44%) or to have diagnoses potentially associated with PPI use such as community‐acquired pneumonia (25%) or C difficile (11%).

| Characteristic | Value |

|---|---|

| |

| Age, y, mean (SD) | 69.615.1 |

| Male gender, N (%) | 75 (49) |

| Initiation of PPI, N (%) | |

| Prior to hospitalization | 127 (84) |

| During hospitalization | 10 (6) |

| In ICU | 7 (4) |

| In ER | 8 (5) |

| Comorbidities, N (%) | |

| Diabetes mellitus | 48 (32) |

| Chronic renal failure, GFR <45 | 29 (20) |

| GI bleed in the last 3 months | 20 (13) |

| No comorbidities | 11 (7) |

| Medications, N (%) | |

| Current antiplatelet agent | 67 (44) |

| Current corticosteroid use | 40 (26) |

| Current therapeutic anticoagulation | 35 (23) |

| Current NSAID use | 13 (8.5) |

| Current bisphosphonate | 13 (8.5) |

| Potential contraindications to PPI, N (%) | |

| Current antibiotic therapy | 67 (44) |

| Pneumonia | 38 (25) |

| Clostridium difficile infection ever | 16 (11) |

| Clostridium difficile infection on present admission | 9 (6) |

Fifty‐four percent (82/152) of patients in whom the online tool was applied had an evidence‐based indication (Table 3). The most common indication for PPI prescription was the receipt of antiplatelet/anticoagulant or nonsteroidal anti‐inflammatory drug with 2 other known risk factors for upper gastrointestinal bleeding (20%). In the remaining 46% (70/152) of patients, the prescription of a PPI was deemed nonevidence based. Of these, 34 (49%) had their PPI discontinued. When patients were approached to discontinue therapy, the rate of success was high, with only 2 refusals.

| Indications | N (%) |

|---|---|

| |

| Approved indications for therapy | |

| Antiplatelet or NSAID with 2 of the following: age >60 years, systemic corticosteroids, previous uncomplicated ulcer, NSAID, or antiplatelet/anticoagulant | 28 (20) |

| Gastric or duodenal ulcer within the past 3 months | 23 (15) |

| Antiplatelet therapy with anticoagulants | 17 (11) |

| GERD with exacerbations within the last 3 months | 17 (11) |

| Dual antiplatelet therapy | 7 (5) |

| Pathological hypersecretory conditions | 0 |

| Helicobactor pylori eradication | 0 |

| Total with consensus indications | 79 (54) |

| Other described indications for therapy | |

| No indication identified | 46 (30) |

| Othera | 22 (14) |

| Palliative patients GERD prophylaxis | 5 (3) |

| Total without consensus indications | 70 (46) |

DISCUSSION

In this prospective intervention, 44% of patients admitted to an acute‐care medical ward were prescribed a PPI prior to their admission. In the subgroup of patients for whom the indication for PPI use was recorded through our online tool, less than half had an evidence‐based indication for ongoing therapy. Our intervention was successful in increasing the proportion of patients in whom preadmission PPI prescriptions were stopped at discharge from an average of 7.7% in the preintervention phase to 18.5% during the intervention. This intervention is novel in that we were able to reduce active community prescriptions for PPIs in patients without obvious indication by nearly 50%.

Our population's rates of PPI prescription were consistent with previous reports,[11, 12, 13, 15, 25, 26, 27, 28] and it is clear that many hospitalized patients continue their PPIs at discharge without clear indications. We propose that hospitalization can serve as an opportunity to reassess the necessity of continuous PPI use. Previous systematic attempts to reduce inappropriate PPI prescriptions in hospital have met with varied success. Several of these studies were unable to achieve a demonstrable effect.[23, 29, 30, 31] In contrast, Hamzat et al.[30] described a successful educational intervention targeting inpatients on a geriatric ward. A 4‐week educational strategy was employed, and they were able to discontinue PPIs in 10 of 60 (17%) patients without indication during a limited period of study. Another successful intervention by Gupta et al.[32] involved a before‐and‐after study combining a half‐hour physician education session with the introduction of a medication reconciliation tool. They showed a decrease in inappropriate discharge prescriptions of 50%. Not only did our study demonstrate an equally sizable reduction in inappropriate discharge prescriptions, but we also employed a more methodologically sound time‐series analysis to control for unmeasured contemporaneous factors such as rotating staff practices or monthly differences in patient composition. We demonstrated an immediate and sustained improvement in performance that lasted over 6 months. Furthermore, in contrast to other interventions, which addressed inappropriate inpatient use persisting on discharge, our intervention also addressed the appropriateness of PPI use that antedated hospitalization.

There are common themes to the successful programs. The more time spent educating and reminding the prescribing physicians, the more successful the intervention. Nonetheless, we believe our intervention is not onerous or overly time consuming. We performed a short presentation each month to educate rotating physicians, and the tool took less than 1 minute to complete once the information on PPI indication was available. Frequent education sessions may be initially necessary given the comfort that many physicians have developed in prescribing PPIs. A further prerequisite for success may be a familiarity with PPI indications and potential adverse effects. Without this, the intervention may not show a demonstrable effect, as was seen in a study of pulmonologists.[23] We hypothesize that some subspecialist physicians may not have the same appreciation of the adverse effects of PPIs nor the confidence to stop them when not indicated, as compared to general internists or hospitalists.

The proportion of patients with newly initiated PPIs at discharge decreased after the intervention, but this did not reach statistical significance. Our study's power may have precluded this. However, we had also previously put in place unpublished interventions to diminish inappropriate gastric prophylaxis in the hospital, which may have diminished the effect of this intervention.

Unfortunately, although we demonstrated a clinically significant effect on PPI exit prescription rates, we still found that nearly half of the patients who were evaluated using the online tool were discharged on PPIs despite our physicians' acknowledgment that they had no identifiable indication. It is possible that clinicians do not feel comfortable stopping these medications, owing to a fear that there is an indication that they are not aware of. In certain cases, it is possible that a reappraisal of the benefits, risks, and costs might reassure the clinician that they could safely stop the drug; however, therapeutic inertia is often hard to overcome.

Limitations

Our single‐center study occurred over a limited time period and examined a sample of patients that were assessed based on convenience. Other limitations included the uptake of the online tool, which was only 54% of patients on a PPI. In particular, few patients who were newly started on a PPI had the online tool applied. This is likely because the tool was filled out on a volunteer basis and was applied most routinely during the admission medication reconciliation process. There were a number of other reasons why the tool was underused, including having the inpatient teams responsible for the data collection despite preexisting demands on their time and the lack of data from patients who were admitted and discharged before a thorough review of the indication for PPI use could take place. However, despite the incomplete use of the online tool, the demographics of patients who were assessed are similar to our usual patient population. As such, we believe the data captured are representative. Furthermore, despite the tool being underused, there remained a clearly objectified reduction in PPI exit prescriptions that occurred immediately postintervention and persisted throughout the entire period of study. Although our teams were not universally using the Web‐tool, it was clear that they were influenced by the project and were stopping unnecessary therapy.

Additionally, the absence of postdischarge follow‐up is also an important limitation. We had originally planned to audit all patients whose PPIs were stopped at 3 months postdischarge but were not systematically able to do so. We did, however, obtain a 1‐time convenience sample interview midway through the intervention. At that time, of 18 patients interviewed, all but 1 remained off of their PPI at 3 months postdischarge. The 1 restart was for reflux symptoms without a preceding trial of lifestyle therapy or H2 blocker.

One final limitation of this study design is that the implementation portion of the intervention took place at the beginning of the academic year. Trainees at the beginning of the year might differ from trainees at the end of the year in that they are more receptive to an educational intervention and less firmly fixed in their practice patterns. If one is considering implementing a similar strategy in their academic institution, we recommend doing so at the start of the academic year to capture the interest of new trainees, maximize the intervention's effectiveness, and establish good habits early in training.

CONCLUSION

We have demonstrated that in medical inpatients, both PPI use and misuse remain common; however, with a combined educational and Web‐based QI intervention, we could successfully decrease inappropriate exit prescriptions. Hospitalization, particularly at academic centers, should serve as an important point of contact for residents in training and expert faculty physicians to reconsider and rationalize patient medications. We should take the opportunity to engender a culture of responsibility for all of the medications that we represcribe at discharge, including an appraisal of the relevant harms and benefits, particularly when a medication is potentially unnecessary. We ought to then communicate the rationale for any changes to our community partners to maintain continuity of care. In this way, hospitalists can help treat the prescription indigestion that has become a common affliction in modern medicine.

Disclosure

Nothing to report.

In 2013, there were more than 15 million Americans receiving proton pump inhibitors (PPIs),[1] with an associated drug cost of nearly $79 billion between 2007 and 2011.2 PPI use is reaching epidemic proportions, likely due to the medicalization of gastrointestinal symptoms coupled with pervasive marketing and academic detailing being performed by the pharmaceutical industry.

Although PPIs are generally considered safe, they are not as innocuous as many physicians believe. In 2011 and 2012, the US Food and Drug Administration and Health Canada, respectively, issued safety advisories regarding the use of these medications related to Clostridium difficile, fracture risk, and electrolyte derangement.[3, 4, 5, 6] There have also been numerous other harmful associations reported,[7, 8, 9, 10] suggesting it would be prudent to follow Health Canada's advice that: PPIs should be prescribed at the lowest dose and shortest duration of therapy appropriate to the condition being treated.[4] In many cases this implies stopping the PPI after an appropriate duration of therapy or attempting nonpharmacological or H2‐blocker therapy instead.

Nevertheless, despite numerous cautionary publications, PPI use for nonevidence‐based indications remains common. Because they are generally thought of as outpatient medications, PPIs are frequently continued in hospitalized patients, and inappropriate outpatient therapy is rarely addressed.[11, 12, 13] Likewise, inappropriate de novo use can also be observed during hospitalization and may continue on discharge.[13, 14, 15] Hospitalization may consequently present an opportunity to employ meaningful interventions targeting outpatient medication use.[16] We developed an opportune inpatient intervention targeting inappropriate PPI therapy.

Our study had 2 aims: first, to determine the magnitude of the problem in a contemporary Canadian medical inpatient population, and second, we sought to leverage the inpatient admission as an opportunity to promote change when the patient returned to the community through the application of an educational and web‐based quality‐improvement (QI) intervention.

METHODS

Patient Inclusion

Between January 2012 and December 2012, we included all consecutively admitted patients on our 46‐bed general medical clinical teaching unit belonging to a 417‐bed tertiary care teaching hospital in Montreal, Canada. There were no exclusion criteria. This time period was divided into 2 blocks: the preintervention control period from January 1 to June 3 and the intervention period from June 4 to December 16.

Intervention and Implementation Strategy

At the start of each academic period, we presented a 20‐minute information session on the benefits and harms of PPI use (see Supporting Information, Appendix, in the online version of this article). The unit's medical residents and faculty attended these rounds. The presentation described the project, consensus‐derived indications for PPI use, and potential adverse events attributable to PPIs (see Table 1 for indications based on internal consensus and similar studies[17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23]). All other indications were considered nonevidence based. At the end of the month, teams were given feedback on indications they provided using the Web tool and the proportion of patients they discharged on a PPI with and without indication.

|

| 1. Gastric or duodenal ulcer within the past 3 months |

| 2. Pathological hypersecretory conditions |

| 3. Gastroesophageal reflux disease with exacerbations within the last 3 months not responsive to H2 blockers and nonpharmacologic techniques |

| 4. Erosive esophagitis |

| 5. Recurring symptoms recently associated with severe indigestion within the last 3 months not responsive to H2 blocker or nonpharmacologic techniques |

| 6. Helicobacter pylori eradication |

| 7. Dual antiplatelet therapy |

| 8. Antiplatelet therapy with anticoagulants |

| 9. Antiplatelet or anticoagulant therapy with history of previous complicated ulcer |

| 10. Antiplatelet or NSAID with 2 of the following: concomitant systemic corticosteroids, age over 60 years, previous uncomplicated ulcer, concomitant NSAID, or antiplatelet/anticoagulant |

The process of evaluating and stopping PPIs was voluntary. Housestaff were encouraged to evaluate PPIs when ordering admission medications and upon preparing exit prescriptions. This was an opt‐in intervention. Once a patient on a PPI was identified, typically on admission to the unit, the indication for use could then be evaluated using the online tool, which was accessible on the internet via a link on all unit computers (see Supporting Information, Appendix, in the online version of this article).

The Web‐based tool was designed to be simple and informative. Users of the tool input anonymous data including comorbidities (check boxes provided). The tool collected the indication for PPI use, with available options including: the consensus‐derived evidence‐based indications, no identified indication, or free text. This was done purposefully to remind the teams of the consensus indications, with the goal that in choosing no identified indication the resident would consider cessation of unnecessary PPIs. The final step in the tool, discharge plan, presented the option of stopping the PPI in the absence of a satisfactory indication. We hypothesized that selecting this option would serve as an informal commitment to discontinuing the PPI during the creation of the discharge prescription; however, the tool was not automatically linked to these prescriptions.

If a home prescription was discontinued, the patient was counselled by the treating team and provided with an educational letter (see Supporting Information, Appendix, in the online version of this article), which was fastened to their discharge summary and given to the patient for delivery to all of their usual outpatient physician(s).

The design of the online tool was such that residents were to evaluate PPI use that would continue postdischarge from the hospital, rather than PPI use limited to the period of hospitalization.

Data Collection and Statistical Analysis

Data on baseline demographics and the specific indications for PPI use were collected through clinician interaction with the online tool. The proportion of patients on a PPI was ascertained through a separate data extraction of electronic discharge prescriptions. These involved medication reconciliation for all outpatient medications including whether or not they were continued, modified, or stopped. Thus, we could determine at discharge whether outpatient PPIs were continued or stopped or if a new PPI was initiated.

The proportion of patients admitted from home already receiving a PPI, those who received a new prescription for a PPI at discharge, and those whose PPI was stopped during admission were compared before and after the intervention using segmented regression analysis of an interrupted time series (see Supporting Information, Appendix, in the online version of this article).[24]

Post Hoc Power Calculations

For the pre‐post comparisons, given the preintervention number of admissions, proportions of PPI use in the community, new PPI use, and PPI discontinuation rates we would have had an 80% power to detect changes of 8.5%, 5%, and 5.5%, respectively.

Ethics

The McGill University Health Centre research ethics board approved this study. Informed consent was waived as the intervention was deemed to be best practice, and data collected were anonymous. Clinical consent was obtained by the treating team for all care decisions.

Funding

This initiative was conducted without any funding.

RESULTS

During the preintervention period, 464 patients were admitted, of whom 209 (45%) were taking a PPI prior to admission. During their hospitalization, an additional 53 patients (21% of nonusers) were newly prescribed a PPI that was continued at discharge. During the intervention period, a total of 640 patients were admitted, of whom 281 (44%) were taking a PPI prior to admission. During their hospitalization, 60 patients (17% of nonusers) were newly prescribed a PPI that was continued at discharge. Neither the monthly proportions admitted on PPIs from prior to admission (level P=0.59, slope P=0.46) or those newly initiated on a PPI (level P=0.36, slope P=0.18) were significantly different before compared to after the intervention. However, there was both a clinically and statistically significant difference in the proportion of preadmission PPIs that were discontinued at hospital discharge from a monthly mean of 7.7% (or 16/209) before intervention to 18.5% (or 52/281) afterward (Figure 1; level P=0.03, slope P=0.48).

During the intervention period, our teams prospectively captured PPI indications and patient comorbidities for 54% (152/281) of the patients admitted on a PPI using the online assessment tool. The baseline characteristics of the population in whom the online tool was applied are shown in Table 2. These patients had a mean age of 69.6 years, and 49% were male. Thirty‐two percent had diabetes, 20% had chronic renal insufficiency, and 13% had experienced a gastrointestinal hemorrhage within the 3 months prior to admission. It was frequent for PPI users to receive systemic antibiotics (44%) or to have diagnoses potentially associated with PPI use such as community‐acquired pneumonia (25%) or C difficile (11%).

| Characteristic | Value |

|---|---|

| |

| Age, y, mean (SD) | 69.615.1 |

| Male gender, N (%) | 75 (49) |

| Initiation of PPI, N (%) | |

| Prior to hospitalization | 127 (84) |

| During hospitalization | 10 (6) |

| In ICU | 7 (4) |

| In ER | 8 (5) |

| Comorbidities, N (%) | |

| Diabetes mellitus | 48 (32) |

| Chronic renal failure, GFR <45 | 29 (20) |

| GI bleed in the last 3 months | 20 (13) |

| No comorbidities | 11 (7) |

| Medications, N (%) | |

| Current antiplatelet agent | 67 (44) |

| Current corticosteroid use | 40 (26) |

| Current therapeutic anticoagulation | 35 (23) |

| Current NSAID use | 13 (8.5) |

| Current bisphosphonate | 13 (8.5) |

| Potential contraindications to PPI, N (%) | |

| Current antibiotic therapy | 67 (44) |

| Pneumonia | 38 (25) |

| Clostridium difficile infection ever | 16 (11) |

| Clostridium difficile infection on present admission | 9 (6) |

Fifty‐four percent (82/152) of patients in whom the online tool was applied had an evidence‐based indication (Table 3). The most common indication for PPI prescription was the receipt of antiplatelet/anticoagulant or nonsteroidal anti‐inflammatory drug with 2 other known risk factors for upper gastrointestinal bleeding (20%). In the remaining 46% (70/152) of patients, the prescription of a PPI was deemed nonevidence based. Of these, 34 (49%) had their PPI discontinued. When patients were approached to discontinue therapy, the rate of success was high, with only 2 refusals.

| Indications | N (%) |

|---|---|

| |

| Approved indications for therapy | |

| Antiplatelet or NSAID with 2 of the following: age >60 years, systemic corticosteroids, previous uncomplicated ulcer, NSAID, or antiplatelet/anticoagulant | 28 (20) |

| Gastric or duodenal ulcer within the past 3 months | 23 (15) |

| Antiplatelet therapy with anticoagulants | 17 (11) |

| GERD with exacerbations within the last 3 months | 17 (11) |

| Dual antiplatelet therapy | 7 (5) |

| Pathological hypersecretory conditions | 0 |

| Helicobactor pylori eradication | 0 |

| Total with consensus indications | 79 (54) |

| Other described indications for therapy | |

| No indication identified | 46 (30) |

| Othera | 22 (14) |

| Palliative patients GERD prophylaxis | 5 (3) |

| Total without consensus indications | 70 (46) |

DISCUSSION

In this prospective intervention, 44% of patients admitted to an acute‐care medical ward were prescribed a PPI prior to their admission. In the subgroup of patients for whom the indication for PPI use was recorded through our online tool, less than half had an evidence‐based indication for ongoing therapy. Our intervention was successful in increasing the proportion of patients in whom preadmission PPI prescriptions were stopped at discharge from an average of 7.7% in the preintervention phase to 18.5% during the intervention. This intervention is novel in that we were able to reduce active community prescriptions for PPIs in patients without obvious indication by nearly 50%.

Our population's rates of PPI prescription were consistent with previous reports,[11, 12, 13, 15, 25, 26, 27, 28] and it is clear that many hospitalized patients continue their PPIs at discharge without clear indications. We propose that hospitalization can serve as an opportunity to reassess the necessity of continuous PPI use. Previous systematic attempts to reduce inappropriate PPI prescriptions in hospital have met with varied success. Several of these studies were unable to achieve a demonstrable effect.[23, 29, 30, 31] In contrast, Hamzat et al.[30] described a successful educational intervention targeting inpatients on a geriatric ward. A 4‐week educational strategy was employed, and they were able to discontinue PPIs in 10 of 60 (17%) patients without indication during a limited period of study. Another successful intervention by Gupta et al.[32] involved a before‐and‐after study combining a half‐hour physician education session with the introduction of a medication reconciliation tool. They showed a decrease in inappropriate discharge prescriptions of 50%. Not only did our study demonstrate an equally sizable reduction in inappropriate discharge prescriptions, but we also employed a more methodologically sound time‐series analysis to control for unmeasured contemporaneous factors such as rotating staff practices or monthly differences in patient composition. We demonstrated an immediate and sustained improvement in performance that lasted over 6 months. Furthermore, in contrast to other interventions, which addressed inappropriate inpatient use persisting on discharge, our intervention also addressed the appropriateness of PPI use that antedated hospitalization.

There are common themes to the successful programs. The more time spent educating and reminding the prescribing physicians, the more successful the intervention. Nonetheless, we believe our intervention is not onerous or overly time consuming. We performed a short presentation each month to educate rotating physicians, and the tool took less than 1 minute to complete once the information on PPI indication was available. Frequent education sessions may be initially necessary given the comfort that many physicians have developed in prescribing PPIs. A further prerequisite for success may be a familiarity with PPI indications and potential adverse effects. Without this, the intervention may not show a demonstrable effect, as was seen in a study of pulmonologists.[23] We hypothesize that some subspecialist physicians may not have the same appreciation of the adverse effects of PPIs nor the confidence to stop them when not indicated, as compared to general internists or hospitalists.

The proportion of patients with newly initiated PPIs at discharge decreased after the intervention, but this did not reach statistical significance. Our study's power may have precluded this. However, we had also previously put in place unpublished interventions to diminish inappropriate gastric prophylaxis in the hospital, which may have diminished the effect of this intervention.

Unfortunately, although we demonstrated a clinically significant effect on PPI exit prescription rates, we still found that nearly half of the patients who were evaluated using the online tool were discharged on PPIs despite our physicians' acknowledgment that they had no identifiable indication. It is possible that clinicians do not feel comfortable stopping these medications, owing to a fear that there is an indication that they are not aware of. In certain cases, it is possible that a reappraisal of the benefits, risks, and costs might reassure the clinician that they could safely stop the drug; however, therapeutic inertia is often hard to overcome.

Limitations

Our single‐center study occurred over a limited time period and examined a sample of patients that were assessed based on convenience. Other limitations included the uptake of the online tool, which was only 54% of patients on a PPI. In particular, few patients who were newly started on a PPI had the online tool applied. This is likely because the tool was filled out on a volunteer basis and was applied most routinely during the admission medication reconciliation process. There were a number of other reasons why the tool was underused, including having the inpatient teams responsible for the data collection despite preexisting demands on their time and the lack of data from patients who were admitted and discharged before a thorough review of the indication for PPI use could take place. However, despite the incomplete use of the online tool, the demographics of patients who were assessed are similar to our usual patient population. As such, we believe the data captured are representative. Furthermore, despite the tool being underused, there remained a clearly objectified reduction in PPI exit prescriptions that occurred immediately postintervention and persisted throughout the entire period of study. Although our teams were not universally using the Web‐tool, it was clear that they were influenced by the project and were stopping unnecessary therapy.

Additionally, the absence of postdischarge follow‐up is also an important limitation. We had originally planned to audit all patients whose PPIs were stopped at 3 months postdischarge but were not systematically able to do so. We did, however, obtain a 1‐time convenience sample interview midway through the intervention. At that time, of 18 patients interviewed, all but 1 remained off of their PPI at 3 months postdischarge. The 1 restart was for reflux symptoms without a preceding trial of lifestyle therapy or H2 blocker.

One final limitation of this study design is that the implementation portion of the intervention took place at the beginning of the academic year. Trainees at the beginning of the year might differ from trainees at the end of the year in that they are more receptive to an educational intervention and less firmly fixed in their practice patterns. If one is considering implementing a similar strategy in their academic institution, we recommend doing so at the start of the academic year to capture the interest of new trainees, maximize the intervention's effectiveness, and establish good habits early in training.

CONCLUSION

We have demonstrated that in medical inpatients, both PPI use and misuse remain common; however, with a combined educational and Web‐based QI intervention, we could successfully decrease inappropriate exit prescriptions. Hospitalization, particularly at academic centers, should serve as an important point of contact for residents in training and expert faculty physicians to reconsider and rationalize patient medications. We should take the opportunity to engender a culture of responsibility for all of the medications that we represcribe at discharge, including an appraisal of the relevant harms and benefits, particularly when a medication is potentially unnecessary. We ought to then communicate the rationale for any changes to our community partners to maintain continuity of care. In this way, hospitalists can help treat the prescription indigestion that has become a common affliction in modern medicine.

Disclosure

Nothing to report.

- IMS Institute for Healthcare Informatics. Medicine Use and Shifting Costs of Healthcare. 2014. Available at: http://www.imshealth.com/deployedfiles/imshealth/Global/Content/Corporate/IMS%20Health%20Institute/Reports/Secure/IIHI_US_Use_of_Meds_for_2013.pdf. Accessed September 26, 2014.

- , , . National use of proton pump inhibitors from 2007 to 2011. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(11):1856–1858.

- Health Canada. Proton Pump Inhibitors (antacids): Possible Risk of Clostridium difficile‐Associated Diarrhea. 2012. Available at: http://www.healthycanadians.gc.ca/recall‐alert‐rappel‐avis/hc‐sc/2012/13651a‐eng.php. Accessed February 16, 2015.

- Health Canada. Proton Pump Inhibitors: Hypomagnesemia Accompanied by Hypocalcemia and Hypokalemia. 2011. Available at: http://www.hc‐sc.gc.ca/dhp‐mps/medeff/bulletin/carn‐bcei_v21n3‐eng.php#_Proton_pump_inhibitors. Accessed February 16, 2015.

- US Food and Drug Administration. FDA Drug Safety Communication: Possible Increased Risk of Fractures of the Hip, Wrist, and Spine With the Use of Proton Pump Inhibitors. 2012. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/PostmarketDrugSafetyInformationforPatientsandProviders/ucm213206.htm. Accessed February 15, 2015.

- US Food and Drug Administration. FDA Drug Safety Communication: Clostridium difficile‐Associated Diarrhea Can Be Associated With Stomach Acid Drugs Known as Proton Pump Inhibitors (PPIs). 2012. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/drugs/drugsafety/ucm290510.htm. Accessed February 15, 2015.

- , , . Meta‐analysis: proton pump inhibitor use and the risk of community‐acquired pneumonia. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;31(11):1165–1177.

- , , , et al. Proton pump inhibitors and risk of 1‐year mortality and rehospitalization in older patients discharged from acute care hospitals. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(7):518–523.

- , , , . Acid‐suppressive medication use and the risk for hospital‐acquired pneumonia. JAMA. 2009;301(20):2120–2128.

- , , , et al. Proton pump inhibitors and functional decline in older adults discharged from acute care hospitals. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014;62(6):1110–1115.

- , , , , . Do hospitalists overuse proton pump inhibitors? Data from a contemporary cohort. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(11):731–733.

- , , , , , . Inappropriate prescribing of proton pump inhibitors in hospitalized patients. J Hosp Med. 2012;7(5):421–425.

- , , , , . Potential costs of inappropriate use of proton pump inhibitors. Am J Med Sci. 2014;347(6):446–451.

- , , , . Long‐term use of acid suppression started inappropriately during hospitalization. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;21(10):1203–1209.

- , , , , , . Continuation of proton pump inhibitors from hospital to community. Pharm World Sci. 2006;28(4):189–193.

- , , , , , . Hospitalist and primary care physician perspectives on medication management of chronic conditions for hospitalized patients. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(5):303–309.

- , , , et al. Antibacterial treatment of gastric ulcers associated with Helicobacter pylori. N Engl J Med. 1995;332(3):139–142.

- , , , et al. Effect of intravenous omeprazole on recurrent bleeding after endoscopic treatment of bleeding peptic ulcers. N Engl J Med. 2000;343(5):310–316.

- , , , et al. Lansoprazole for the prevention of recurrences of ulcer complications from long‐term low‐dose aspirin use. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(26):2033–2038.

- , . American College of Gastroenterology guideline on the management of Helicobacter pylori infection. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102(8):1808–1825.

- , , . Guidelines for prevention of NSAID‐related ulcer complications. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104(3):728–738.

- , , , Canadian consensus guidelines on long‐term nonsteroidal anti‐inflammatory drug therapy and the need for gastroprotection: benefits versus risks. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009;29(5):481–496.

- , , , et al., The effects of guideline implementation for proton pump inhibitor prescription on two pulmonary medicine wards. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009;29(2):213–221.

- , , , . Segmented regression analysis of interrupted time series studies in medication use research. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2002;27(4):299–309.

- , , . Overuse of acid‐suppressive therapy in hospitalized patients. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95(11):3118–3122.

- , , , . Proton pump inhibitors: a survey of prescribing in an Irish general hospital. Int J Clin Pract. 2005;59(1):31–34.

- , , . Overuse of proton pump inhibitors. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2000;25(5):333–340.

- , , , et al. Prevalence and appropriateness of drug prescriptions for peptic ulcer and gastro‐esophageal reflux disease in a cohort of hospitalized elderly. Eur J Intern Med. 2011;22(2):205–210.

- , , , . Inappropriate prescribing of proton pump inhibitors in primary care. Postgrad Med J. 2007;83(975):66–68.

- , , , , , . Inappropriate prescribing of proton pump inhibitors in older patients: effects of an educational strategy. Drugs Aging. 2012;29(8):681–690.

- , , , . Impact of academic detailing on proton pump inhibitor prescribing behaviour in a community hospital. Can Pharm J (Ott). 2011;144(2):66–71.

- , , , , , . Decreased acid suppression therapy overuse after education and medication reconciliation. Int J Clin Pract. 2013;67(1):60–65.

- IMS Institute for Healthcare Informatics. Medicine Use and Shifting Costs of Healthcare. 2014. Available at: http://www.imshealth.com/deployedfiles/imshealth/Global/Content/Corporate/IMS%20Health%20Institute/Reports/Secure/IIHI_US_Use_of_Meds_for_2013.pdf. Accessed September 26, 2014.

- , , . National use of proton pump inhibitors from 2007 to 2011. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(11):1856–1858.

- Health Canada. Proton Pump Inhibitors (antacids): Possible Risk of Clostridium difficile‐Associated Diarrhea. 2012. Available at: http://www.healthycanadians.gc.ca/recall‐alert‐rappel‐avis/hc‐sc/2012/13651a‐eng.php. Accessed February 16, 2015.

- Health Canada. Proton Pump Inhibitors: Hypomagnesemia Accompanied by Hypocalcemia and Hypokalemia. 2011. Available at: http://www.hc‐sc.gc.ca/dhp‐mps/medeff/bulletin/carn‐bcei_v21n3‐eng.php#_Proton_pump_inhibitors. Accessed February 16, 2015.

- US Food and Drug Administration. FDA Drug Safety Communication: Possible Increased Risk of Fractures of the Hip, Wrist, and Spine With the Use of Proton Pump Inhibitors. 2012. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/PostmarketDrugSafetyInformationforPatientsandProviders/ucm213206.htm. Accessed February 15, 2015.

- US Food and Drug Administration. FDA Drug Safety Communication: Clostridium difficile‐Associated Diarrhea Can Be Associated With Stomach Acid Drugs Known as Proton Pump Inhibitors (PPIs). 2012. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/drugs/drugsafety/ucm290510.htm. Accessed February 15, 2015.

- , , . Meta‐analysis: proton pump inhibitor use and the risk of community‐acquired pneumonia. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;31(11):1165–1177.

- , , , et al. Proton pump inhibitors and risk of 1‐year mortality and rehospitalization in older patients discharged from acute care hospitals. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(7):518–523.

- , , , . Acid‐suppressive medication use and the risk for hospital‐acquired pneumonia. JAMA. 2009;301(20):2120–2128.

- , , , et al. Proton pump inhibitors and functional decline in older adults discharged from acute care hospitals. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014;62(6):1110–1115.

- , , , , . Do hospitalists overuse proton pump inhibitors? Data from a contemporary cohort. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(11):731–733.

- , , , , , . Inappropriate prescribing of proton pump inhibitors in hospitalized patients. J Hosp Med. 2012;7(5):421–425.

- , , , , . Potential costs of inappropriate use of proton pump inhibitors. Am J Med Sci. 2014;347(6):446–451.

- , , , . Long‐term use of acid suppression started inappropriately during hospitalization. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;21(10):1203–1209.

- , , , , , . Continuation of proton pump inhibitors from hospital to community. Pharm World Sci. 2006;28(4):189–193.

- , , , , , . Hospitalist and primary care physician perspectives on medication management of chronic conditions for hospitalized patients. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(5):303–309.

- , , , et al. Antibacterial treatment of gastric ulcers associated with Helicobacter pylori. N Engl J Med. 1995;332(3):139–142.

- , , , et al. Effect of intravenous omeprazole on recurrent bleeding after endoscopic treatment of bleeding peptic ulcers. N Engl J Med. 2000;343(5):310–316.

- , , , et al. Lansoprazole for the prevention of recurrences of ulcer complications from long‐term low‐dose aspirin use. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(26):2033–2038.

- , . American College of Gastroenterology guideline on the management of Helicobacter pylori infection. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102(8):1808–1825.

- , , . Guidelines for prevention of NSAID‐related ulcer complications. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104(3):728–738.

- , , , Canadian consensus guidelines on long‐term nonsteroidal anti‐inflammatory drug therapy and the need for gastroprotection: benefits versus risks. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009;29(5):481–496.

- , , , et al., The effects of guideline implementation for proton pump inhibitor prescription on two pulmonary medicine wards. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009;29(2):213–221.

- , , , . Segmented regression analysis of interrupted time series studies in medication use research. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2002;27(4):299–309.

- , , . Overuse of acid‐suppressive therapy in hospitalized patients. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95(11):3118–3122.

- , , , . Proton pump inhibitors: a survey of prescribing in an Irish general hospital. Int J Clin Pract. 2005;59(1):31–34.

- , , . Overuse of proton pump inhibitors. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2000;25(5):333–340.

- , , , et al. Prevalence and appropriateness of drug prescriptions for peptic ulcer and gastro‐esophageal reflux disease in a cohort of hospitalized elderly. Eur J Intern Med. 2011;22(2):205–210.

- , , , . Inappropriate prescribing of proton pump inhibitors in primary care. Postgrad Med J. 2007;83(975):66–68.

- , , , , , . Inappropriate prescribing of proton pump inhibitors in older patients: effects of an educational strategy. Drugs Aging. 2012;29(8):681–690.

- , , , . Impact of academic detailing on proton pump inhibitor prescribing behaviour in a community hospital. Can Pharm J (Ott). 2011;144(2):66–71.

- , , , , , . Decreased acid suppression therapy overuse after education and medication reconciliation. Int J Clin Pract. 2013;67(1):60–65.

© 2015 Society of Hospital Medicine