User login

James J. Stevermer is in the Department of Family and Community Medicine at the University of Missouri–Columbia.

A-fib and rate control: Don’t go too low

Aim for a heart rate of <110 beats per minute (bpm) in patients with permanent atrial fibrillation. Maintaining this rate requires less medication than more stringent rate control, resulting in fewer side effects and no increased risk of cardiovascular events.1

STRENGTH OF RECOMMENDATION

B: Based on 1 long-term randomized controlled trial (RCT).

Van Gelder IC, Groenveld HF, Crijns HJ, et al. Lenient versus strict rate control in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2010;362: 1363-1373.

Illustrative case

A 67-year-old man comes in for a follow-up visit after being hospitalized for atrial fibrillation with a rapid ventricular rate. Before being discharged, he was put on warfarin and metoprolol, and his heart rate today is 96 bpm. You consider increasing the dose of his beta-blocker. What should his target heart rate be?

Atrial fibrillation, the most common sustained arrhythmia,2 can lead to life-threatening events such as heart failure and stroke. Studies, including the Atrial Fibrillation Follow-Up Investigation of Rhythm Management (AFFIRM) and Rate Control versus Electrical Cardioversion (RACE) trials, have found no difference in morbidity or mortality between rate control and rhythm control strategies.2,3 Thus, rate control is usually preferred for patients with atrial fibrillation because of adverse effects associated with antiarrhythmic drugs.

Guidelines cite stringent targets

The American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force/European Society of Cardiology (ACC/AHA/ESC) guidelines make no definite recommendations about heart rate targets. The guidelines do indicate, however, that rate control criteria vary based on age, “but usually involve achieving ventricular rates between 60 and 80 [bpm] at rest and between 90 and 115 [bpm] during moderate exercise.”4

This guidance is based on data from epidemiologic studies suggesting that faster heart rates in sinus rhythm may increase mortality from cardiovascular causes.5 However, strict control often requires higher doses of rate-controlling medications, which can lead to adverse events such as symptomatic bradycardia, dizziness, and syncope, as well as pacemaker implantation.

Pooled data suggest a more relaxed rate is better

A retrospective analysis of pooled data from the rate-control arms of the AFFIRM and RACE trials found no difference in all-cause mortality between the more stringent rate-control group in AFFIRM and the more lenient control in RACE.6 This finding suggested that more lenient heart rate targets may be preferred to avoid the adverse effects often associated with the higher doses of rate-controlling drugs needed to achieve strict control. The Rate Control Efficacy in Permanent Atrial Fibrillation: a Comparison between Lenient versus Strict Rate Control II (RACE II) study we report on here provides strong evidence in favor of lenient rate control.

STUDY SUMMARY: Lenient control is as effective, easier to achieve

RACE II was the first RCT to directly compare lenient rate control (resting heart rate <110 bpm) with strict rate control (resting heart rate <80 bpm, and <110 bpm during moderate exercise). This prospective, multi-center study in Holland randomized patients with permanent atrial fibrillation (N=614) to either a lenient or strict rate-control group. Eligibility criteria were (1) permanent atrial fibrillation for up to 12 months; (2) ≤80 years of age (3) mean resting heart rate >80 bpm; and (4) current use of oral anticoagulation therapy (or aspirin, in the absence of risk factors for thromboembolic complications).

Patients received various doses of beta-blockers, nondihydropyridine calcium-channel blockers, or digoxin, singly or in combination as needed to reach the target heart rate. In both groups, the resting heart rate was determined by 12-lead electrocardiogram after the patient remained in a supine position for 2 to 3 minutes. In the strict-control group, heart rate was also measured during moderate exercise on a stationary bicycle after the resting rate goal had been achieved. In addition, patients in the strict-control group wore a Holter monitor for 24 hours to check for bradycardia.

Participants in both groups were seen every 2 weeks until their heart rate goals were achieved, with follow-up at 1, 2, and 3 years. The primary composite outcome included death from cardiovascular causes; hospitalization for heart failure, stroke, systemic embolism, major bleeding, or life-threatening adverse effects of rate-control drugs; arrhythmic events, including sustained ventricular tachycardia, syncope, or cardiac arrest; and implantation of a pacemaker or cardioverter-defibrillator.

At the end of 3 years, the estimated cumulative incidence of the primary outcome was 12.9% in the lenient-control group vs 14.9% in the strict-control group. The absolute difference was -2.0 (90% confidence interval [CI], -7.6 to 3.5); a 90% CI was acceptable because the study only tested whether lenient control was worse than strict control. The frequency of reported symptoms and adverse events was similar between the 2 groups, but the lenient-control group had fewer visits for rate control (75 vs 684; P<.001), required fewer medications, and took lower doses of some medications.

Heart rate targets were met in 97.7% of patients in the lenient-control group, compared with 67% in the strict-control group (P<.001). Of those not meeting the strict control targets, 25% were due to an adverse medication event. There were no differences between the 2 groups in symptoms or in New York Heart Association functional class status.

WHAT'S NEW: Now we know: It doesn’t pay to go too low

A heart rate <80 at rest and <110 during exercise is difficult to maintain. This more stringent target often requires high dosages of drugs and/or multiple medications, which may lead to adverse effects. This RCT—the first to compare outcomes in patients with lenient vs strict heart rate control—found that morbidity and mortality were similar between the 2 groups. This means that, in many cases, patients will need less medication—leading to a reduction in risk of side effects and interactions.

CAVEATS: Unblinded study excluded very old, high risk

This was not a blinded study, so both patients and providers knew the target heart rates. However, the major outcomes were determined with relative objectivity and were not different between the 2 groups, so it is unlikely that this knowledge would have a major effect on the results. Nonetheless, this is a single study, and the findings are not yet supported by other large, prospective studies.

The researchers did not enroll patients >80 years, who have a higher incidence of atrial fibrillation and are less likely than younger patients to tolerate higher doses of rate-controlling medications. Also excluded were sedentary patients and those with a history of stroke, which resulted in a lower-risk study population. However, 40% of the subjects had a CHADS score ≥2 (an indication of high risk of stroke in patients with atrial fibrillation), and subgroup analysis found that the results applied to higher-risk groups.

Finally, it is possible that it may take longer than 3 years (the duration of study follow-up) for higher ventricular rates to result in adverse cardiovascular outcomes and that there could be a benefit of strict rate control over a longer period of time.

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION: Guidelines do not reflect these findings

These findings are not yet incorporated into the ACC/AHA/ESC guidelines or those issued by other organizations. Clinical inertia may stop some physicians from reducing medications for patients with atrial fibrillation, but in general, both doctors and patients should welcome an easing of the drug burden.

Click here to view PURL METHODOLOGY

1. Van Gelder IC, Groenveld HF, Crijns HJ, et al. Lenient versus strict rate control in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1363-1373.

2. Wyse DG, Waldo AL, DiMarco JP, et al. A comparison of rate control and rhythm control in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:1825-1833.

3. Hagens VE, Ranchor AV, Van SE, et al. Effect of rate or rhythm control on quality of life in persistent atrial fibrillation. Results from the Rate Control Versus Electrical Cardioversion (RACE) Study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43:241-247.

4. Fuster V, Ryden LE, Cannom DS, et al. ACC/AHA/ESC 2006 Guidelines for the Management of Patients with Atrial Fibrillation: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and the European Society of Cardiology Committee for Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Revise the 2001 Guidelines for the Management of Patients With Atrial Fibrillation): developed in collaboration with the European Heart Rhythm Association and the Heart Rhythm Society. Circulation. 2006;114:e257-e354.

5. Dorian P. Rate control in atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1439-1441.

6. Van Gelder IC, Wyse DG, Chandler ML, et al. Does intensity of rate-control influence outcome in atrial fibrillation? An analysis of pooled data from the RACE and AFFIRM studies. Europace. 2006;8:935-942.

Aim for a heart rate of <110 beats per minute (bpm) in patients with permanent atrial fibrillation. Maintaining this rate requires less medication than more stringent rate control, resulting in fewer side effects and no increased risk of cardiovascular events.1

STRENGTH OF RECOMMENDATION

B: Based on 1 long-term randomized controlled trial (RCT).

Van Gelder IC, Groenveld HF, Crijns HJ, et al. Lenient versus strict rate control in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2010;362: 1363-1373.

Illustrative case

A 67-year-old man comes in for a follow-up visit after being hospitalized for atrial fibrillation with a rapid ventricular rate. Before being discharged, he was put on warfarin and metoprolol, and his heart rate today is 96 bpm. You consider increasing the dose of his beta-blocker. What should his target heart rate be?

Atrial fibrillation, the most common sustained arrhythmia,2 can lead to life-threatening events such as heart failure and stroke. Studies, including the Atrial Fibrillation Follow-Up Investigation of Rhythm Management (AFFIRM) and Rate Control versus Electrical Cardioversion (RACE) trials, have found no difference in morbidity or mortality between rate control and rhythm control strategies.2,3 Thus, rate control is usually preferred for patients with atrial fibrillation because of adverse effects associated with antiarrhythmic drugs.

Guidelines cite stringent targets

The American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force/European Society of Cardiology (ACC/AHA/ESC) guidelines make no definite recommendations about heart rate targets. The guidelines do indicate, however, that rate control criteria vary based on age, “but usually involve achieving ventricular rates between 60 and 80 [bpm] at rest and between 90 and 115 [bpm] during moderate exercise.”4

This guidance is based on data from epidemiologic studies suggesting that faster heart rates in sinus rhythm may increase mortality from cardiovascular causes.5 However, strict control often requires higher doses of rate-controlling medications, which can lead to adverse events such as symptomatic bradycardia, dizziness, and syncope, as well as pacemaker implantation.

Pooled data suggest a more relaxed rate is better

A retrospective analysis of pooled data from the rate-control arms of the AFFIRM and RACE trials found no difference in all-cause mortality between the more stringent rate-control group in AFFIRM and the more lenient control in RACE.6 This finding suggested that more lenient heart rate targets may be preferred to avoid the adverse effects often associated with the higher doses of rate-controlling drugs needed to achieve strict control. The Rate Control Efficacy in Permanent Atrial Fibrillation: a Comparison between Lenient versus Strict Rate Control II (RACE II) study we report on here provides strong evidence in favor of lenient rate control.

STUDY SUMMARY: Lenient control is as effective, easier to achieve

RACE II was the first RCT to directly compare lenient rate control (resting heart rate <110 bpm) with strict rate control (resting heart rate <80 bpm, and <110 bpm during moderate exercise). This prospective, multi-center study in Holland randomized patients with permanent atrial fibrillation (N=614) to either a lenient or strict rate-control group. Eligibility criteria were (1) permanent atrial fibrillation for up to 12 months; (2) ≤80 years of age (3) mean resting heart rate >80 bpm; and (4) current use of oral anticoagulation therapy (or aspirin, in the absence of risk factors for thromboembolic complications).

Patients received various doses of beta-blockers, nondihydropyridine calcium-channel blockers, or digoxin, singly or in combination as needed to reach the target heart rate. In both groups, the resting heart rate was determined by 12-lead electrocardiogram after the patient remained in a supine position for 2 to 3 minutes. In the strict-control group, heart rate was also measured during moderate exercise on a stationary bicycle after the resting rate goal had been achieved. In addition, patients in the strict-control group wore a Holter monitor for 24 hours to check for bradycardia.

Participants in both groups were seen every 2 weeks until their heart rate goals were achieved, with follow-up at 1, 2, and 3 years. The primary composite outcome included death from cardiovascular causes; hospitalization for heart failure, stroke, systemic embolism, major bleeding, or life-threatening adverse effects of rate-control drugs; arrhythmic events, including sustained ventricular tachycardia, syncope, or cardiac arrest; and implantation of a pacemaker or cardioverter-defibrillator.

At the end of 3 years, the estimated cumulative incidence of the primary outcome was 12.9% in the lenient-control group vs 14.9% in the strict-control group. The absolute difference was -2.0 (90% confidence interval [CI], -7.6 to 3.5); a 90% CI was acceptable because the study only tested whether lenient control was worse than strict control. The frequency of reported symptoms and adverse events was similar between the 2 groups, but the lenient-control group had fewer visits for rate control (75 vs 684; P<.001), required fewer medications, and took lower doses of some medications.

Heart rate targets were met in 97.7% of patients in the lenient-control group, compared with 67% in the strict-control group (P<.001). Of those not meeting the strict control targets, 25% were due to an adverse medication event. There were no differences between the 2 groups in symptoms or in New York Heart Association functional class status.

WHAT'S NEW: Now we know: It doesn’t pay to go too low

A heart rate <80 at rest and <110 during exercise is difficult to maintain. This more stringent target often requires high dosages of drugs and/or multiple medications, which may lead to adverse effects. This RCT—the first to compare outcomes in patients with lenient vs strict heart rate control—found that morbidity and mortality were similar between the 2 groups. This means that, in many cases, patients will need less medication—leading to a reduction in risk of side effects and interactions.

CAVEATS: Unblinded study excluded very old, high risk

This was not a blinded study, so both patients and providers knew the target heart rates. However, the major outcomes were determined with relative objectivity and were not different between the 2 groups, so it is unlikely that this knowledge would have a major effect on the results. Nonetheless, this is a single study, and the findings are not yet supported by other large, prospective studies.

The researchers did not enroll patients >80 years, who have a higher incidence of atrial fibrillation and are less likely than younger patients to tolerate higher doses of rate-controlling medications. Also excluded were sedentary patients and those with a history of stroke, which resulted in a lower-risk study population. However, 40% of the subjects had a CHADS score ≥2 (an indication of high risk of stroke in patients with atrial fibrillation), and subgroup analysis found that the results applied to higher-risk groups.

Finally, it is possible that it may take longer than 3 years (the duration of study follow-up) for higher ventricular rates to result in adverse cardiovascular outcomes and that there could be a benefit of strict rate control over a longer period of time.

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION: Guidelines do not reflect these findings

These findings are not yet incorporated into the ACC/AHA/ESC guidelines or those issued by other organizations. Clinical inertia may stop some physicians from reducing medications for patients with atrial fibrillation, but in general, both doctors and patients should welcome an easing of the drug burden.

Click here to view PURL METHODOLOGY

Aim for a heart rate of <110 beats per minute (bpm) in patients with permanent atrial fibrillation. Maintaining this rate requires less medication than more stringent rate control, resulting in fewer side effects and no increased risk of cardiovascular events.1

STRENGTH OF RECOMMENDATION

B: Based on 1 long-term randomized controlled trial (RCT).

Van Gelder IC, Groenveld HF, Crijns HJ, et al. Lenient versus strict rate control in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2010;362: 1363-1373.

Illustrative case

A 67-year-old man comes in for a follow-up visit after being hospitalized for atrial fibrillation with a rapid ventricular rate. Before being discharged, he was put on warfarin and metoprolol, and his heart rate today is 96 bpm. You consider increasing the dose of his beta-blocker. What should his target heart rate be?

Atrial fibrillation, the most common sustained arrhythmia,2 can lead to life-threatening events such as heart failure and stroke. Studies, including the Atrial Fibrillation Follow-Up Investigation of Rhythm Management (AFFIRM) and Rate Control versus Electrical Cardioversion (RACE) trials, have found no difference in morbidity or mortality between rate control and rhythm control strategies.2,3 Thus, rate control is usually preferred for patients with atrial fibrillation because of adverse effects associated with antiarrhythmic drugs.

Guidelines cite stringent targets

The American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force/European Society of Cardiology (ACC/AHA/ESC) guidelines make no definite recommendations about heart rate targets. The guidelines do indicate, however, that rate control criteria vary based on age, “but usually involve achieving ventricular rates between 60 and 80 [bpm] at rest and between 90 and 115 [bpm] during moderate exercise.”4

This guidance is based on data from epidemiologic studies suggesting that faster heart rates in sinus rhythm may increase mortality from cardiovascular causes.5 However, strict control often requires higher doses of rate-controlling medications, which can lead to adverse events such as symptomatic bradycardia, dizziness, and syncope, as well as pacemaker implantation.

Pooled data suggest a more relaxed rate is better

A retrospective analysis of pooled data from the rate-control arms of the AFFIRM and RACE trials found no difference in all-cause mortality between the more stringent rate-control group in AFFIRM and the more lenient control in RACE.6 This finding suggested that more lenient heart rate targets may be preferred to avoid the adverse effects often associated with the higher doses of rate-controlling drugs needed to achieve strict control. The Rate Control Efficacy in Permanent Atrial Fibrillation: a Comparison between Lenient versus Strict Rate Control II (RACE II) study we report on here provides strong evidence in favor of lenient rate control.

STUDY SUMMARY: Lenient control is as effective, easier to achieve

RACE II was the first RCT to directly compare lenient rate control (resting heart rate <110 bpm) with strict rate control (resting heart rate <80 bpm, and <110 bpm during moderate exercise). This prospective, multi-center study in Holland randomized patients with permanent atrial fibrillation (N=614) to either a lenient or strict rate-control group. Eligibility criteria were (1) permanent atrial fibrillation for up to 12 months; (2) ≤80 years of age (3) mean resting heart rate >80 bpm; and (4) current use of oral anticoagulation therapy (or aspirin, in the absence of risk factors for thromboembolic complications).

Patients received various doses of beta-blockers, nondihydropyridine calcium-channel blockers, or digoxin, singly or in combination as needed to reach the target heart rate. In both groups, the resting heart rate was determined by 12-lead electrocardiogram after the patient remained in a supine position for 2 to 3 minutes. In the strict-control group, heart rate was also measured during moderate exercise on a stationary bicycle after the resting rate goal had been achieved. In addition, patients in the strict-control group wore a Holter monitor for 24 hours to check for bradycardia.

Participants in both groups were seen every 2 weeks until their heart rate goals were achieved, with follow-up at 1, 2, and 3 years. The primary composite outcome included death from cardiovascular causes; hospitalization for heart failure, stroke, systemic embolism, major bleeding, or life-threatening adverse effects of rate-control drugs; arrhythmic events, including sustained ventricular tachycardia, syncope, or cardiac arrest; and implantation of a pacemaker or cardioverter-defibrillator.

At the end of 3 years, the estimated cumulative incidence of the primary outcome was 12.9% in the lenient-control group vs 14.9% in the strict-control group. The absolute difference was -2.0 (90% confidence interval [CI], -7.6 to 3.5); a 90% CI was acceptable because the study only tested whether lenient control was worse than strict control. The frequency of reported symptoms and adverse events was similar between the 2 groups, but the lenient-control group had fewer visits for rate control (75 vs 684; P<.001), required fewer medications, and took lower doses of some medications.

Heart rate targets were met in 97.7% of patients in the lenient-control group, compared with 67% in the strict-control group (P<.001). Of those not meeting the strict control targets, 25% were due to an adverse medication event. There were no differences between the 2 groups in symptoms or in New York Heart Association functional class status.

WHAT'S NEW: Now we know: It doesn’t pay to go too low

A heart rate <80 at rest and <110 during exercise is difficult to maintain. This more stringent target often requires high dosages of drugs and/or multiple medications, which may lead to adverse effects. This RCT—the first to compare outcomes in patients with lenient vs strict heart rate control—found that morbidity and mortality were similar between the 2 groups. This means that, in many cases, patients will need less medication—leading to a reduction in risk of side effects and interactions.

CAVEATS: Unblinded study excluded very old, high risk

This was not a blinded study, so both patients and providers knew the target heart rates. However, the major outcomes were determined with relative objectivity and were not different between the 2 groups, so it is unlikely that this knowledge would have a major effect on the results. Nonetheless, this is a single study, and the findings are not yet supported by other large, prospective studies.

The researchers did not enroll patients >80 years, who have a higher incidence of atrial fibrillation and are less likely than younger patients to tolerate higher doses of rate-controlling medications. Also excluded were sedentary patients and those with a history of stroke, which resulted in a lower-risk study population. However, 40% of the subjects had a CHADS score ≥2 (an indication of high risk of stroke in patients with atrial fibrillation), and subgroup analysis found that the results applied to higher-risk groups.

Finally, it is possible that it may take longer than 3 years (the duration of study follow-up) for higher ventricular rates to result in adverse cardiovascular outcomes and that there could be a benefit of strict rate control over a longer period of time.

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION: Guidelines do not reflect these findings

These findings are not yet incorporated into the ACC/AHA/ESC guidelines or those issued by other organizations. Clinical inertia may stop some physicians from reducing medications for patients with atrial fibrillation, but in general, both doctors and patients should welcome an easing of the drug burden.

Click here to view PURL METHODOLOGY

1. Van Gelder IC, Groenveld HF, Crijns HJ, et al. Lenient versus strict rate control in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1363-1373.

2. Wyse DG, Waldo AL, DiMarco JP, et al. A comparison of rate control and rhythm control in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:1825-1833.

3. Hagens VE, Ranchor AV, Van SE, et al. Effect of rate or rhythm control on quality of life in persistent atrial fibrillation. Results from the Rate Control Versus Electrical Cardioversion (RACE) Study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43:241-247.

4. Fuster V, Ryden LE, Cannom DS, et al. ACC/AHA/ESC 2006 Guidelines for the Management of Patients with Atrial Fibrillation: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and the European Society of Cardiology Committee for Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Revise the 2001 Guidelines for the Management of Patients With Atrial Fibrillation): developed in collaboration with the European Heart Rhythm Association and the Heart Rhythm Society. Circulation. 2006;114:e257-e354.

5. Dorian P. Rate control in atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1439-1441.

6. Van Gelder IC, Wyse DG, Chandler ML, et al. Does intensity of rate-control influence outcome in atrial fibrillation? An analysis of pooled data from the RACE and AFFIRM studies. Europace. 2006;8:935-942.

1. Van Gelder IC, Groenveld HF, Crijns HJ, et al. Lenient versus strict rate control in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1363-1373.

2. Wyse DG, Waldo AL, DiMarco JP, et al. A comparison of rate control and rhythm control in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:1825-1833.

3. Hagens VE, Ranchor AV, Van SE, et al. Effect of rate or rhythm control on quality of life in persistent atrial fibrillation. Results from the Rate Control Versus Electrical Cardioversion (RACE) Study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43:241-247.

4. Fuster V, Ryden LE, Cannom DS, et al. ACC/AHA/ESC 2006 Guidelines for the Management of Patients with Atrial Fibrillation: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and the European Society of Cardiology Committee for Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Revise the 2001 Guidelines for the Management of Patients With Atrial Fibrillation): developed in collaboration with the European Heart Rhythm Association and the Heart Rhythm Society. Circulation. 2006;114:e257-e354.

5. Dorian P. Rate control in atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1439-1441.

6. Van Gelder IC, Wyse DG, Chandler ML, et al. Does intensity of rate-control influence outcome in atrial fibrillation? An analysis of pooled data from the RACE and AFFIRM studies. Europace. 2006;8:935-942.

Copyright © 2010 The Family Physicians Inquiries Network. All rights reserved.

Fracture pain relief for kids? Ibuprofen does it better

Use ibuprofen instead of acetaminophen with codeine for pediatric arm fractures. It controls the pain at least as well and is better tolerated.1-3

Strength of Recommendation

A: Based on 1 longer-term and 2 short-term randomized controlled trials (RCTs).

1. Drendel AL, Gorelick MH, Weisman SJ, et al. A randomized clinical trial of ibuprofen versus acetaminophen with codeine for acute pediatric arm fracture pain. Ann Emerg Med. 2009;54:553-560.

2. Koller DM, Myers AB, Lorenz D, et al. Effectiveness of oxycodone, ibuprofen, or the combination in the initial management of orthopedic injury-related pain in children. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2007;23:627-633.

3. Clark E, Plint AC, Correll R, et al. A randomized controlled clinical trial of acetaminophen, ibuprofen, and codeine for acute pain relief in children with musculoskeletal trauma. Pediatrics. 2007;119:460-467.

Illustrative case

A mother brings her 6-year-old son to the emergency department (ED) for treatment of forearm pain after a bicycle accident. clinical examination reveals a swollen and tender wrist. A radiograph confirms a diagnosis of a nondisplaced distal radial fracture. After proper stabilization, the little boy is discharged home, with a visit to his primary care physician scheduled for the following week. if he were your patient, what would you prescribe for outpatient analgesia?

Musculoskeletal trauma is a common pediatric presentation, in both emergency and office settings. In fact, it is estimated that by age 15, one-half to two-thirds of children will have fractured a bone.4 Physicians commonly prescribe nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and opioids—especially acetaminophen with codeine—as analgesia for children with fractures,5 but few studies have directly compared these medications in pediatric patients.

No consensus on analgesia for musculoskeletal pain in kids

Pain associated with an acute fracture is substantial, and most children who incur fractures are managed at home, and thus require effective and well-tolerated oral analgesia. However, prescribing practices vary widely, and there is no consensus regarding the first-line medication for kids with fracture.

A Cochrane review of adult postoperative pain concluded that NSAIDs are effective, and they are commonly prescribed to adult patients for various types of pain.6 Fewer studies of pain control in children exist. Before the 2009 study reported on here, there were just 2 RCTs that addressed pediatric musculoskeletal pain in patients presenting to the ED.

In single-dose studies, ibuprofen comes out ahead

The smaller of the 2 trials (N=66) compared ibuprofen alone vs ibuprofen plus oxycodone for suspected orthopedic injury. The researchers found that pain relief was equivalent, but the oxycodone group had more adverse effects.2 The larger trial (N=336) compared ibuprofen, acetaminophen, and codeine for acute pediatric musculoskeletal injuries. An hour after receiving their study drug, children in the ibuprofen group had significantly greater reduction in pain than those in either the acetaminophen group or the codeine group. They were also more likely to report adequate analgesia.3 Neither study followed patients after discharge from the ED.

STUDY SUMMARY: New RCT evaluates pain relief once patients go home

The Drendel study was a randomized, controlled, double-blind trial of outpatient analgesia for pediatric fractures.1 The investigators randomized 336 children ages 4 to 18 years with radiographically confirmed arm fractures to a suspension of either ibuprofen (10 mg/kg) or acetaminophen with codeine (1 mg/kg codeine component per dose), which are recommended dosages. They enrolled a convenience sample of children with nondisplaced fractures that did not require reduction in the ED.

Children were excluded if they weighed more than 60 kg, preferred tablets to liquid medication, sought care more than 12 hours after injury, or had developmental delays or contraindications to any study medication. Also excluded were children—or their parents—who did not speak English and those who were inaccessible by telephone for follow-up.

Study groups had similar baseline demographic and fracture characteristics, and similar pain scores. Patients and their parents were blinded to the assigned drug; all received the same discharge instructions and 2 doses of a rescue medication (the alternate study drug). The primary outcome was use of rescue medication due to failure of the assigned study drug. Secondary outcomes included decrease in pain score, functional outcomes (play, school, eating, sleeping), and satisfaction with the medication.

During the 72 hours after discharge from the ED, patients and parents filled out a standard diary recording pain and medication use. The diaries were returned by mail. Follow-up was good, with about 75% of diaries returned.

Ibuprofen users had fewer problems

Analysis of 244 diaries revealed that less rescue medication was used in the ibuprofen group, although the difference was not statistically significant (20.3% vs 31% [absolute risk reduction, 10.7%], 95% confidence interval, -0.2% to 21.6%). Decrease in mean pain score was the same in both groups. Functional status the day after the injury was better in the ibuprofen group compared with the acetaminophen/codeine group. In addition, 50.9% of patients in the acetaminophen/codeine group reported adverse events, vs 29.5% of those in the ibuprofen group (number needed to harm=4.7).

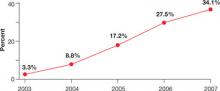

At the study’s end, children were more satisfied with ibuprofen. Only 10% of patients who took ibuprofen said they would not use it for future fractures; in comparison, 27.5% of patients in the acetaminophen/codeine group said they would not choose to use codeine again.

The authors followed participants for 1 to 4 years through orthopedic clinic records and telephone calls for any long-term adverse orthopedic outcomes. Four cases of refracture at the same site occurred (1.6%), 3 of which were in the acetaminophen/codeine group. There were no cases of nonunion.

WHAT'S NEW: Ibuprofen emerges as first-line agent for kids

Both ibuprofen and acetaminophen with codeine are commonly prescribed for outpatient pediatric analgesia, but this is the first study to compare them head-to-head for outpatient management of postfracture pain. Ibuprofen worked at least as well as acetaminophen with codeine for fracture pain control, and had fewer adverse effects. Children given ibuprofen were better able to eat and play than those given acetaminophen with codeine—an important patient-oriented functional outcome. Patients and their parents were also more satisfied when ED physicians prescribed ibuprofen. This study is consistent with short-term (single-dose) studies and confirms that ibuprofen should be the first-line agent for outpatient analgesia in this group.

CAVEATS: Study did not address NSAIDs’ effect on bone healing

In theory, ibuprofen—like other NSAIDs—can diminish the proinflammatory milieu required for bone turnover and fracture healing. Chart reviews of up to 4 years after the incident fracture found no evidence that ibuprofen delayed healing or increased rates of refracture. However, this study was neither designed nor powered to examine this outcome. Previous studies have found no conclusive evidence that short-term use of NSAIDs impairs fracture healing.7,8

Results apply only to simple fractures. Patients in this study did not require manipulation or reduction of their fracture, limiting the scope of the authors’ recommendation to simple arm fractures. More severe injury may require narcotic analgesia. One can assume, based on this and other supporting literature, that the findings extrapolate to other similarly painful pediatric musculoskeletal injuries.2

Twenty-five percent of subjects were lost to follow-up. Follow-up diaries were available from about 75% of the participants. It is possible that a clearer beneficial outcome would have been found with 1 of the analgesics studied if the response rate had been higher. Because this study is consistent with the previous ED-only studies comparing ibuprofen with acetaminophen plus codeine, however, it is unlikely that a higher response rate would find ibuprofen inferior to acetaminophen plus codeine.

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION: Parents—or patients—may expect an Rx

Prescribing an effective, common, inexpensive, and well-tolerated oral medication should have no barriers to implementation. Still, use of an over-the-counter medication, however effective, may face resistance from patients or parents who expect “something more” for fracture pain.

Acknowledgement

The PURLs Surveillance System is supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center for Research Resources; the grant is a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center for Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

Click here to view PURL METHODOLOGY

1. Drendel AL, Gorelick MH, Weisman SJ, et al. A randomized clinical trial of ibuprofen versus acetaminophen with codeine for acute pediatric arm fracture pain. Ann Emerg Med. 2009;54:553-560.

2. Koller DM, Myers AB, Lorenz D, et al. Effectiveness of oxycodone, ibuprofen, or the combination in the initial management of orthopedic injury-related pain in children. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2007;23:627-633.

3. Clark E, Plint AC, Correll R, et al. A randomized, controlled trial of acetaminophen, ibuprofen, and codeine for acute pain relief in children with musculoskeletal trauma. Pediatrics. 2007;119:460-467.

4. Lyons RA, Delahunty AM, Kraus D, et al. Children’s fractures: a population based study. Inj Prev. 1999;5:129-132.

5. Drendel AL, Lyon R, Bergholte J, et al. Outpatient pediatric pain management practices for fractures. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2006;22:94-99.

6. Derry C, Derry S, Moore RA, et al. Single dose oral ibuprofen for acute postoperative pain in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;(3):CD001548.-

7. Clarke S, Lecky F. Best evidence topic report. Do non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs cause a delay in fracture healing? Emerg Med J. 2005;22:652-653.

8. Wheeler P, Batt ME. Do non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs adversely affect stress fracture healing? A short review. Br J Sports Med. 2005;39:65-69.

Use ibuprofen instead of acetaminophen with codeine for pediatric arm fractures. It controls the pain at least as well and is better tolerated.1-3

Strength of Recommendation

A: Based on 1 longer-term and 2 short-term randomized controlled trials (RCTs).

1. Drendel AL, Gorelick MH, Weisman SJ, et al. A randomized clinical trial of ibuprofen versus acetaminophen with codeine for acute pediatric arm fracture pain. Ann Emerg Med. 2009;54:553-560.

2. Koller DM, Myers AB, Lorenz D, et al. Effectiveness of oxycodone, ibuprofen, or the combination in the initial management of orthopedic injury-related pain in children. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2007;23:627-633.

3. Clark E, Plint AC, Correll R, et al. A randomized controlled clinical trial of acetaminophen, ibuprofen, and codeine for acute pain relief in children with musculoskeletal trauma. Pediatrics. 2007;119:460-467.

Illustrative case

A mother brings her 6-year-old son to the emergency department (ED) for treatment of forearm pain after a bicycle accident. clinical examination reveals a swollen and tender wrist. A radiograph confirms a diagnosis of a nondisplaced distal radial fracture. After proper stabilization, the little boy is discharged home, with a visit to his primary care physician scheduled for the following week. if he were your patient, what would you prescribe for outpatient analgesia?

Musculoskeletal trauma is a common pediatric presentation, in both emergency and office settings. In fact, it is estimated that by age 15, one-half to two-thirds of children will have fractured a bone.4 Physicians commonly prescribe nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and opioids—especially acetaminophen with codeine—as analgesia for children with fractures,5 but few studies have directly compared these medications in pediatric patients.

No consensus on analgesia for musculoskeletal pain in kids

Pain associated with an acute fracture is substantial, and most children who incur fractures are managed at home, and thus require effective and well-tolerated oral analgesia. However, prescribing practices vary widely, and there is no consensus regarding the first-line medication for kids with fracture.

A Cochrane review of adult postoperative pain concluded that NSAIDs are effective, and they are commonly prescribed to adult patients for various types of pain.6 Fewer studies of pain control in children exist. Before the 2009 study reported on here, there were just 2 RCTs that addressed pediatric musculoskeletal pain in patients presenting to the ED.

In single-dose studies, ibuprofen comes out ahead

The smaller of the 2 trials (N=66) compared ibuprofen alone vs ibuprofen plus oxycodone for suspected orthopedic injury. The researchers found that pain relief was equivalent, but the oxycodone group had more adverse effects.2 The larger trial (N=336) compared ibuprofen, acetaminophen, and codeine for acute pediatric musculoskeletal injuries. An hour after receiving their study drug, children in the ibuprofen group had significantly greater reduction in pain than those in either the acetaminophen group or the codeine group. They were also more likely to report adequate analgesia.3 Neither study followed patients after discharge from the ED.

STUDY SUMMARY: New RCT evaluates pain relief once patients go home

The Drendel study was a randomized, controlled, double-blind trial of outpatient analgesia for pediatric fractures.1 The investigators randomized 336 children ages 4 to 18 years with radiographically confirmed arm fractures to a suspension of either ibuprofen (10 mg/kg) or acetaminophen with codeine (1 mg/kg codeine component per dose), which are recommended dosages. They enrolled a convenience sample of children with nondisplaced fractures that did not require reduction in the ED.

Children were excluded if they weighed more than 60 kg, preferred tablets to liquid medication, sought care more than 12 hours after injury, or had developmental delays or contraindications to any study medication. Also excluded were children—or their parents—who did not speak English and those who were inaccessible by telephone for follow-up.

Study groups had similar baseline demographic and fracture characteristics, and similar pain scores. Patients and their parents were blinded to the assigned drug; all received the same discharge instructions and 2 doses of a rescue medication (the alternate study drug). The primary outcome was use of rescue medication due to failure of the assigned study drug. Secondary outcomes included decrease in pain score, functional outcomes (play, school, eating, sleeping), and satisfaction with the medication.

During the 72 hours after discharge from the ED, patients and parents filled out a standard diary recording pain and medication use. The diaries were returned by mail. Follow-up was good, with about 75% of diaries returned.

Ibuprofen users had fewer problems

Analysis of 244 diaries revealed that less rescue medication was used in the ibuprofen group, although the difference was not statistically significant (20.3% vs 31% [absolute risk reduction, 10.7%], 95% confidence interval, -0.2% to 21.6%). Decrease in mean pain score was the same in both groups. Functional status the day after the injury was better in the ibuprofen group compared with the acetaminophen/codeine group. In addition, 50.9% of patients in the acetaminophen/codeine group reported adverse events, vs 29.5% of those in the ibuprofen group (number needed to harm=4.7).

At the study’s end, children were more satisfied with ibuprofen. Only 10% of patients who took ibuprofen said they would not use it for future fractures; in comparison, 27.5% of patients in the acetaminophen/codeine group said they would not choose to use codeine again.

The authors followed participants for 1 to 4 years through orthopedic clinic records and telephone calls for any long-term adverse orthopedic outcomes. Four cases of refracture at the same site occurred (1.6%), 3 of which were in the acetaminophen/codeine group. There were no cases of nonunion.

WHAT'S NEW: Ibuprofen emerges as first-line agent for kids

Both ibuprofen and acetaminophen with codeine are commonly prescribed for outpatient pediatric analgesia, but this is the first study to compare them head-to-head for outpatient management of postfracture pain. Ibuprofen worked at least as well as acetaminophen with codeine for fracture pain control, and had fewer adverse effects. Children given ibuprofen were better able to eat and play than those given acetaminophen with codeine—an important patient-oriented functional outcome. Patients and their parents were also more satisfied when ED physicians prescribed ibuprofen. This study is consistent with short-term (single-dose) studies and confirms that ibuprofen should be the first-line agent for outpatient analgesia in this group.

CAVEATS: Study did not address NSAIDs’ effect on bone healing

In theory, ibuprofen—like other NSAIDs—can diminish the proinflammatory milieu required for bone turnover and fracture healing. Chart reviews of up to 4 years after the incident fracture found no evidence that ibuprofen delayed healing or increased rates of refracture. However, this study was neither designed nor powered to examine this outcome. Previous studies have found no conclusive evidence that short-term use of NSAIDs impairs fracture healing.7,8

Results apply only to simple fractures. Patients in this study did not require manipulation or reduction of their fracture, limiting the scope of the authors’ recommendation to simple arm fractures. More severe injury may require narcotic analgesia. One can assume, based on this and other supporting literature, that the findings extrapolate to other similarly painful pediatric musculoskeletal injuries.2

Twenty-five percent of subjects were lost to follow-up. Follow-up diaries were available from about 75% of the participants. It is possible that a clearer beneficial outcome would have been found with 1 of the analgesics studied if the response rate had been higher. Because this study is consistent with the previous ED-only studies comparing ibuprofen with acetaminophen plus codeine, however, it is unlikely that a higher response rate would find ibuprofen inferior to acetaminophen plus codeine.

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION: Parents—or patients—may expect an Rx

Prescribing an effective, common, inexpensive, and well-tolerated oral medication should have no barriers to implementation. Still, use of an over-the-counter medication, however effective, may face resistance from patients or parents who expect “something more” for fracture pain.

Acknowledgement

The PURLs Surveillance System is supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center for Research Resources; the grant is a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center for Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

Click here to view PURL METHODOLOGY

Use ibuprofen instead of acetaminophen with codeine for pediatric arm fractures. It controls the pain at least as well and is better tolerated.1-3

Strength of Recommendation

A: Based on 1 longer-term and 2 short-term randomized controlled trials (RCTs).

1. Drendel AL, Gorelick MH, Weisman SJ, et al. A randomized clinical trial of ibuprofen versus acetaminophen with codeine for acute pediatric arm fracture pain. Ann Emerg Med. 2009;54:553-560.

2. Koller DM, Myers AB, Lorenz D, et al. Effectiveness of oxycodone, ibuprofen, or the combination in the initial management of orthopedic injury-related pain in children. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2007;23:627-633.

3. Clark E, Plint AC, Correll R, et al. A randomized controlled clinical trial of acetaminophen, ibuprofen, and codeine for acute pain relief in children with musculoskeletal trauma. Pediatrics. 2007;119:460-467.

Illustrative case

A mother brings her 6-year-old son to the emergency department (ED) for treatment of forearm pain after a bicycle accident. clinical examination reveals a swollen and tender wrist. A radiograph confirms a diagnosis of a nondisplaced distal radial fracture. After proper stabilization, the little boy is discharged home, with a visit to his primary care physician scheduled for the following week. if he were your patient, what would you prescribe for outpatient analgesia?

Musculoskeletal trauma is a common pediatric presentation, in both emergency and office settings. In fact, it is estimated that by age 15, one-half to two-thirds of children will have fractured a bone.4 Physicians commonly prescribe nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and opioids—especially acetaminophen with codeine—as analgesia for children with fractures,5 but few studies have directly compared these medications in pediatric patients.

No consensus on analgesia for musculoskeletal pain in kids

Pain associated with an acute fracture is substantial, and most children who incur fractures are managed at home, and thus require effective and well-tolerated oral analgesia. However, prescribing practices vary widely, and there is no consensus regarding the first-line medication for kids with fracture.

A Cochrane review of adult postoperative pain concluded that NSAIDs are effective, and they are commonly prescribed to adult patients for various types of pain.6 Fewer studies of pain control in children exist. Before the 2009 study reported on here, there were just 2 RCTs that addressed pediatric musculoskeletal pain in patients presenting to the ED.

In single-dose studies, ibuprofen comes out ahead

The smaller of the 2 trials (N=66) compared ibuprofen alone vs ibuprofen plus oxycodone for suspected orthopedic injury. The researchers found that pain relief was equivalent, but the oxycodone group had more adverse effects.2 The larger trial (N=336) compared ibuprofen, acetaminophen, and codeine for acute pediatric musculoskeletal injuries. An hour after receiving their study drug, children in the ibuprofen group had significantly greater reduction in pain than those in either the acetaminophen group or the codeine group. They were also more likely to report adequate analgesia.3 Neither study followed patients after discharge from the ED.

STUDY SUMMARY: New RCT evaluates pain relief once patients go home

The Drendel study was a randomized, controlled, double-blind trial of outpatient analgesia for pediatric fractures.1 The investigators randomized 336 children ages 4 to 18 years with radiographically confirmed arm fractures to a suspension of either ibuprofen (10 mg/kg) or acetaminophen with codeine (1 mg/kg codeine component per dose), which are recommended dosages. They enrolled a convenience sample of children with nondisplaced fractures that did not require reduction in the ED.

Children were excluded if they weighed more than 60 kg, preferred tablets to liquid medication, sought care more than 12 hours after injury, or had developmental delays or contraindications to any study medication. Also excluded were children—or their parents—who did not speak English and those who were inaccessible by telephone for follow-up.

Study groups had similar baseline demographic and fracture characteristics, and similar pain scores. Patients and their parents were blinded to the assigned drug; all received the same discharge instructions and 2 doses of a rescue medication (the alternate study drug). The primary outcome was use of rescue medication due to failure of the assigned study drug. Secondary outcomes included decrease in pain score, functional outcomes (play, school, eating, sleeping), and satisfaction with the medication.

During the 72 hours after discharge from the ED, patients and parents filled out a standard diary recording pain and medication use. The diaries were returned by mail. Follow-up was good, with about 75% of diaries returned.

Ibuprofen users had fewer problems

Analysis of 244 diaries revealed that less rescue medication was used in the ibuprofen group, although the difference was not statistically significant (20.3% vs 31% [absolute risk reduction, 10.7%], 95% confidence interval, -0.2% to 21.6%). Decrease in mean pain score was the same in both groups. Functional status the day after the injury was better in the ibuprofen group compared with the acetaminophen/codeine group. In addition, 50.9% of patients in the acetaminophen/codeine group reported adverse events, vs 29.5% of those in the ibuprofen group (number needed to harm=4.7).

At the study’s end, children were more satisfied with ibuprofen. Only 10% of patients who took ibuprofen said they would not use it for future fractures; in comparison, 27.5% of patients in the acetaminophen/codeine group said they would not choose to use codeine again.

The authors followed participants for 1 to 4 years through orthopedic clinic records and telephone calls for any long-term adverse orthopedic outcomes. Four cases of refracture at the same site occurred (1.6%), 3 of which were in the acetaminophen/codeine group. There were no cases of nonunion.

WHAT'S NEW: Ibuprofen emerges as first-line agent for kids

Both ibuprofen and acetaminophen with codeine are commonly prescribed for outpatient pediatric analgesia, but this is the first study to compare them head-to-head for outpatient management of postfracture pain. Ibuprofen worked at least as well as acetaminophen with codeine for fracture pain control, and had fewer adverse effects. Children given ibuprofen were better able to eat and play than those given acetaminophen with codeine—an important patient-oriented functional outcome. Patients and their parents were also more satisfied when ED physicians prescribed ibuprofen. This study is consistent with short-term (single-dose) studies and confirms that ibuprofen should be the first-line agent for outpatient analgesia in this group.

CAVEATS: Study did not address NSAIDs’ effect on bone healing

In theory, ibuprofen—like other NSAIDs—can diminish the proinflammatory milieu required for bone turnover and fracture healing. Chart reviews of up to 4 years after the incident fracture found no evidence that ibuprofen delayed healing or increased rates of refracture. However, this study was neither designed nor powered to examine this outcome. Previous studies have found no conclusive evidence that short-term use of NSAIDs impairs fracture healing.7,8

Results apply only to simple fractures. Patients in this study did not require manipulation or reduction of their fracture, limiting the scope of the authors’ recommendation to simple arm fractures. More severe injury may require narcotic analgesia. One can assume, based on this and other supporting literature, that the findings extrapolate to other similarly painful pediatric musculoskeletal injuries.2

Twenty-five percent of subjects were lost to follow-up. Follow-up diaries were available from about 75% of the participants. It is possible that a clearer beneficial outcome would have been found with 1 of the analgesics studied if the response rate had been higher. Because this study is consistent with the previous ED-only studies comparing ibuprofen with acetaminophen plus codeine, however, it is unlikely that a higher response rate would find ibuprofen inferior to acetaminophen plus codeine.

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION: Parents—or patients—may expect an Rx

Prescribing an effective, common, inexpensive, and well-tolerated oral medication should have no barriers to implementation. Still, use of an over-the-counter medication, however effective, may face resistance from patients or parents who expect “something more” for fracture pain.

Acknowledgement

The PURLs Surveillance System is supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center for Research Resources; the grant is a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center for Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

Click here to view PURL METHODOLOGY

1. Drendel AL, Gorelick MH, Weisman SJ, et al. A randomized clinical trial of ibuprofen versus acetaminophen with codeine for acute pediatric arm fracture pain. Ann Emerg Med. 2009;54:553-560.

2. Koller DM, Myers AB, Lorenz D, et al. Effectiveness of oxycodone, ibuprofen, or the combination in the initial management of orthopedic injury-related pain in children. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2007;23:627-633.

3. Clark E, Plint AC, Correll R, et al. A randomized, controlled trial of acetaminophen, ibuprofen, and codeine for acute pain relief in children with musculoskeletal trauma. Pediatrics. 2007;119:460-467.

4. Lyons RA, Delahunty AM, Kraus D, et al. Children’s fractures: a population based study. Inj Prev. 1999;5:129-132.

5. Drendel AL, Lyon R, Bergholte J, et al. Outpatient pediatric pain management practices for fractures. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2006;22:94-99.

6. Derry C, Derry S, Moore RA, et al. Single dose oral ibuprofen for acute postoperative pain in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;(3):CD001548.-

7. Clarke S, Lecky F. Best evidence topic report. Do non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs cause a delay in fracture healing? Emerg Med J. 2005;22:652-653.

8. Wheeler P, Batt ME. Do non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs adversely affect stress fracture healing? A short review. Br J Sports Med. 2005;39:65-69.

1. Drendel AL, Gorelick MH, Weisman SJ, et al. A randomized clinical trial of ibuprofen versus acetaminophen with codeine for acute pediatric arm fracture pain. Ann Emerg Med. 2009;54:553-560.

2. Koller DM, Myers AB, Lorenz D, et al. Effectiveness of oxycodone, ibuprofen, or the combination in the initial management of orthopedic injury-related pain in children. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2007;23:627-633.

3. Clark E, Plint AC, Correll R, et al. A randomized, controlled trial of acetaminophen, ibuprofen, and codeine for acute pain relief in children with musculoskeletal trauma. Pediatrics. 2007;119:460-467.

4. Lyons RA, Delahunty AM, Kraus D, et al. Children’s fractures: a population based study. Inj Prev. 1999;5:129-132.

5. Drendel AL, Lyon R, Bergholte J, et al. Outpatient pediatric pain management practices for fractures. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2006;22:94-99.

6. Derry C, Derry S, Moore RA, et al. Single dose oral ibuprofen for acute postoperative pain in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;(3):CD001548.-

7. Clarke S, Lecky F. Best evidence topic report. Do non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs cause a delay in fracture healing? Emerg Med J. 2005;22:652-653.

8. Wheeler P, Batt ME. Do non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs adversely affect stress fracture healing? A short review. Br J Sports Med. 2005;39:65-69.

Copyright © 2010 The Family Physicians Inquiries Network.

All rights reserved.

Start a statin prior to vascular surgery

HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors (statins), initiated 30 days before noncardiac vascular surgery, reduce the incidence of postoperative cardiac complications, including fatal myocardial infarction.1,2

STRENGTH OF RECOMMENDATION

A: 1 new randomized controlled trial (RCT), and 1 smaller, older RCT.

Schouten O, Boersma E, Hoeks S, et al. Fluvastatin and perioperative events in patients undergoing vascular surgery. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:980-989.

Durazzo AE, Machado FS, Ikeoka DT, et al. Reduction in cardiovascular events after vascular surgery with atorvastatin: a randomized trial. J Vasc Surg. 2004;39:967-975.

ILLUSTRATIVE CASE

A 67-year-old man with recurrent transient ischemic attacks comes in for a preoperative evaluation for carotid endarterectomy. The patient’s total cholesterol is 207 mg/dL and his low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) is 109 mg/dL. He takes metoprolol and lisinopril for hypertension.

Should you start him on a statin before surgery?

Nearly 25% of patients with peripheral vascular disease suffer from a cardiac event within 72 hours of elective, noncardiac vascular surgery.3 While most of these “complications” have minimal clinical impact and are detected by biochemical markers alone, some patients experience serious cardiac complications—including fatal myocardial infarction (MI).

That’s not surprising, given that most patients who require noncardiac vascular surgery suffer from severe coronary vascular disease.4 What is surprising is that most candidates for noncardiac vascular surgery are not put on statins prior to undergoing surgery.1,2,5

Statins were thought to increase—not prevent—complications

Until recently, taking statins during the perioperative period was believed to increase complications, including statin-associated myopathy. Indeed, guidelines from the American Heart Association (AHA), American College of Cardiology (ACC), and National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI) suggest that it is prudent to withhold statins during hospitalization for major surgery.6

1 small study hinted at value of perioperative statins

A small Brazilian trial conducted in 2004 called the AHA/ACC/NHLBI guidelines into question. the researchers studied 100 patients slated for noncardiac vascular surgery who were randomized to receive either 20 mg atorvastatin (Lipitor) or placebo preoperatively —and monitored them for cardiac events 6 months postoperatively. They found that the incidence of cardiac events (cardiac death, nonfatal MI, stroke, or unstable angina) was more than 3 times higher in the placebo group compared with patients receiving atorvastatin (26% vs 8%, number needed to treat [NNT]=5.6; P=.031).2

The results of this small single study, although suggestive, were not sufficiently convincing to change recommendations about the preoperative use of statins, however. A more comprehensive study was needed to alter standard practice, and the Schouten study that we report on below fits the bill.1

STUDY SUMMARY: Preoperative statin use cuts risk in half

Schouten et al followed 500 patients, who were randomized to receive either 80 mg extended-release fluvastatin (Lescol XL) or placebo for a median of 37 days prior to surgery.1 All enrollees were older than 40 years of age and were scheduled for noncardiac vascular surgery. the reasons for the surgery were abdominal aortic aneurysm repair (47.5%), lower limb arterial reconstruction (38.6%), or carotid artery endarterectomy (13.9%). Patients who were taking long-term beta-blocker therapy were continued on it; otherwise, bisoprolol 2.5 mg was initiated at the screening visit. Patients who were already taking statins (<50% of potential subjects) were excluded. Other exclusions were a contraindication to statin therapy; emergent surgery; and a repeat procedure within the last 29 days. Patients with unstable coronary artery disease or extensive stress-induced ischemia consistent with left main artery disease (or its equivalent) were also excluded.

The primary study outcome was myocardial ischemia, determined by continuous electrocardiogram (EKG) monitoring in the first 48 hours postsurgery and by 12-lead EKG recordings on days 3, 7, and 30. Troponin T levels were measured on postoperative days 1, 3, 7, and 30, as well. the principal secondary end point was either death from cardiovascular causes or nonfatal MI. MI was diagnosed by characteristic ischemic symptoms, with EKG evidence of ischemia or positive troponin T with characteristic rising and falling values.

To gauge fluvastatin’s effect on biomarkers, lipids, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein, and interleukin-6 were measured upon initiation of the medication and on the day of admission for surgery. Serum creatine kinase, alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels, clinical myopathy, and rhabdomyolysis were monitored as safety measures, with levels measured prior to randomization, on the day of admission, and on postoperative days 1, 3, 7, and 30.

Both groups were similar in age (mean of 66 years), total serum cholesterol levels, risk factors for cardiac events, and medication use. About 75% of the enrollees were men. At baseline, 51% of the participants had a total cholesterol <213 mg/dL, and 39% had an LDL-C <116 mg/dL. Within 30 days after surgery, 27 (10.8%) of those in the fluvastatin group and 47 (19%) of patients in the placebo group had evidence of myocardial ischemia (hazard ratio=0.55; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.34-0.88; P=.01). the NNT to prevent 1 patient from experiencing myocardial ischemia was 12.

Statin users had fewer MIs. A total of 6 patients receiving fluvastatin died, with 4 deaths attributed to cardiovascular causes. In the placebo group, 12 patients died, 8 of which were ascribed to cardiovascular causes. Eight patients in the fluvastatin group experienced nonfatal MIs, compared with 17 patients in the placebo group (NNT=19 to prevent 1 nonfatal MI or cardiac death (hazard ratio= 0.47; 95% CI, 0.24-0.94; P=.03).

Effects of statins were evident preoperatively. At the time of surgery, patients in the fluvastatin group had, on average, a 20% reduction in their total cholesterol and a 24% reduction in LDL-C; in the placebo group, total cholesterol had fallen by 4% and LDL-C, by 3%.

Patients receiving fluvastatin had an average 21% decrease in C-reactive protein, compared with a 3% increase for the placebo group. Interleukin-6 levels also were reduced far more in the fluvastatin group (33% vs a 4% reduction in the placebo group [P<.001]).

The medication was well tolerated. Overall, 6.8% of participants discontinued the study because of side effects, including 16 (6.4%) patients in the fluvastatin group and 18 (7.3%) in the placebo group. (After surgery, 115 [23.1%] of patients in the statin group temporarily discontinued the drug because of an inability to take oral medications for a median of 2 days.)

Rates of increase in creatine kinase of >10× the upper limit of normal (ULN) were similar between the fluvastatin and placebo groups (4% vs 3.2%, respectively). Increases in ALT to >3× ULN were more frequent in the placebo group compared with the fluvastatin group (5.3%, placebo; 3.2%, fluvastatin). No cases of myopathy or rhabdomyolysis were observed in either group.

WHAT’S NEW: Preop statins can be a lifesaver

The initiation of fluvastatin prior to vascular surgery reduced the incidence of cardiovascular events by 50%—a remarkable result. While patients at the highest risk were excluded from the study, those with lower cardiac risk nonetheless benefi ted from statin therapy. Experts have not typically recommended statins in the perioperative period for this patient population. the results of this study make it clear that they should.

CAVEATS: Extended-release formulation may have affected outcome

The statin used in this study was a longacting formulation, which may have protected patients who were unable to take oral medicines postoperatively. While we don’t know if the extended-release formulation made a difference in this study, we do know that atorvastatin was effective in the Brazilian study discussed earlier.

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION: Preop statins may be overlooked

Not all patients see a primary care physician prior to undergoing vascular surgery. This means that it will sometimes be left to surgeons or other specialists to initiate statin therapy prior to surgery, and they may or may not do so.

Optimal timing is unknown. It is not clear how little time a patient scheduled for vascular surgery could spend on a statin and still reap these benefits. Nor do we know if the benefits would extend to patients undergoing other types of surgery; in a large study of patients undergoing all kinds of major noncardiac surgery, no benefits of perioperative statins were found.7

Adherence to the medication regimen presents another challenge, at least for some patients. In this case, however, we think the prospect of preventing major cardiac events postoperatively simply by taking statins for a month should be compelling enough to convince patients to take their medicine.

Acknowledgement

The PURLs Surveillance System is supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center for Research Resources; the grant is a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the ofcial views of either the National Center for Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

Click here to view PURL METHODOLOGY

1. Schouten O, Boersma E, Hoeks SE, et al. Fluvastatin and perioperative events in patients undergoing vascular surgery. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:980-989.

2. Durazzo AE, Machado FS, Ikeoka DT, et al. Reduction in cardiovascular events after vascular surgery with atorvastatin: a randomized trial. J Vasc Surg. 2004;39:967-975.

3. Pasternak RC, Smith SC, Jr, Bairey-Merz CN, et al. ACC/AHA/ NHLBI Clinical advisory on the use and safety of statins. Circulation. 2002;106:1024-1028.

4. Landesberg G, Shatz V, Akopnik I, et al. Association of cardiac troponin, CK-MB, and postoperative myocardial ischemia with long-term survival after major vascular surgery. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;42:1547-1554.

5. Hertzer NR, Beven EG, Young JR, et al. Coronary artery disease in peripheral vascular patients. A classification of 1000 coronary angiograms and results of surgical management. Ann Surg. 1984;199:223-233.

6. Brady AR, Gibbs JS, Greenhalgh RM, et al. Perioperative betablockade (POBBLE) for patients undergoing infrarenal vascular surgery: results of a randomized double-blind controlled trial. J Vasc Surg. 2005;41:602-609.

7. Dunkelgrun M, Boersma E, Schouten O, et al. Bisoprolol and fluvastatin for the reduction of perioperative cardiac mortality and myocardial infarction in intermediate-risk patients undergoing noncardiovascular surgery: a randomized controlled trial (DECREASE-IV). Ann Surg. 2009;249:921-926.

HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors (statins), initiated 30 days before noncardiac vascular surgery, reduce the incidence of postoperative cardiac complications, including fatal myocardial infarction.1,2

STRENGTH OF RECOMMENDATION

A: 1 new randomized controlled trial (RCT), and 1 smaller, older RCT.

Schouten O, Boersma E, Hoeks S, et al. Fluvastatin and perioperative events in patients undergoing vascular surgery. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:980-989.

Durazzo AE, Machado FS, Ikeoka DT, et al. Reduction in cardiovascular events after vascular surgery with atorvastatin: a randomized trial. J Vasc Surg. 2004;39:967-975.

ILLUSTRATIVE CASE

A 67-year-old man with recurrent transient ischemic attacks comes in for a preoperative evaluation for carotid endarterectomy. The patient’s total cholesterol is 207 mg/dL and his low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) is 109 mg/dL. He takes metoprolol and lisinopril for hypertension.

Should you start him on a statin before surgery?

Nearly 25% of patients with peripheral vascular disease suffer from a cardiac event within 72 hours of elective, noncardiac vascular surgery.3 While most of these “complications” have minimal clinical impact and are detected by biochemical markers alone, some patients experience serious cardiac complications—including fatal myocardial infarction (MI).

That’s not surprising, given that most patients who require noncardiac vascular surgery suffer from severe coronary vascular disease.4 What is surprising is that most candidates for noncardiac vascular surgery are not put on statins prior to undergoing surgery.1,2,5

Statins were thought to increase—not prevent—complications

Until recently, taking statins during the perioperative period was believed to increase complications, including statin-associated myopathy. Indeed, guidelines from the American Heart Association (AHA), American College of Cardiology (ACC), and National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI) suggest that it is prudent to withhold statins during hospitalization for major surgery.6

1 small study hinted at value of perioperative statins

A small Brazilian trial conducted in 2004 called the AHA/ACC/NHLBI guidelines into question. the researchers studied 100 patients slated for noncardiac vascular surgery who were randomized to receive either 20 mg atorvastatin (Lipitor) or placebo preoperatively —and monitored them for cardiac events 6 months postoperatively. They found that the incidence of cardiac events (cardiac death, nonfatal MI, stroke, or unstable angina) was more than 3 times higher in the placebo group compared with patients receiving atorvastatin (26% vs 8%, number needed to treat [NNT]=5.6; P=.031).2

The results of this small single study, although suggestive, were not sufficiently convincing to change recommendations about the preoperative use of statins, however. A more comprehensive study was needed to alter standard practice, and the Schouten study that we report on below fits the bill.1

STUDY SUMMARY: Preoperative statin use cuts risk in half

Schouten et al followed 500 patients, who were randomized to receive either 80 mg extended-release fluvastatin (Lescol XL) or placebo for a median of 37 days prior to surgery.1 All enrollees were older than 40 years of age and were scheduled for noncardiac vascular surgery. the reasons for the surgery were abdominal aortic aneurysm repair (47.5%), lower limb arterial reconstruction (38.6%), or carotid artery endarterectomy (13.9%). Patients who were taking long-term beta-blocker therapy were continued on it; otherwise, bisoprolol 2.5 mg was initiated at the screening visit. Patients who were already taking statins (<50% of potential subjects) were excluded. Other exclusions were a contraindication to statin therapy; emergent surgery; and a repeat procedure within the last 29 days. Patients with unstable coronary artery disease or extensive stress-induced ischemia consistent with left main artery disease (or its equivalent) were also excluded.

The primary study outcome was myocardial ischemia, determined by continuous electrocardiogram (EKG) monitoring in the first 48 hours postsurgery and by 12-lead EKG recordings on days 3, 7, and 30. Troponin T levels were measured on postoperative days 1, 3, 7, and 30, as well. the principal secondary end point was either death from cardiovascular causes or nonfatal MI. MI was diagnosed by characteristic ischemic symptoms, with EKG evidence of ischemia or positive troponin T with characteristic rising and falling values.

To gauge fluvastatin’s effect on biomarkers, lipids, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein, and interleukin-6 were measured upon initiation of the medication and on the day of admission for surgery. Serum creatine kinase, alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels, clinical myopathy, and rhabdomyolysis were monitored as safety measures, with levels measured prior to randomization, on the day of admission, and on postoperative days 1, 3, 7, and 30.

Both groups were similar in age (mean of 66 years), total serum cholesterol levels, risk factors for cardiac events, and medication use. About 75% of the enrollees were men. At baseline, 51% of the participants had a total cholesterol <213 mg/dL, and 39% had an LDL-C <116 mg/dL. Within 30 days after surgery, 27 (10.8%) of those in the fluvastatin group and 47 (19%) of patients in the placebo group had evidence of myocardial ischemia (hazard ratio=0.55; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.34-0.88; P=.01). the NNT to prevent 1 patient from experiencing myocardial ischemia was 12.

Statin users had fewer MIs. A total of 6 patients receiving fluvastatin died, with 4 deaths attributed to cardiovascular causes. In the placebo group, 12 patients died, 8 of which were ascribed to cardiovascular causes. Eight patients in the fluvastatin group experienced nonfatal MIs, compared with 17 patients in the placebo group (NNT=19 to prevent 1 nonfatal MI or cardiac death (hazard ratio= 0.47; 95% CI, 0.24-0.94; P=.03).

Effects of statins were evident preoperatively. At the time of surgery, patients in the fluvastatin group had, on average, a 20% reduction in their total cholesterol and a 24% reduction in LDL-C; in the placebo group, total cholesterol had fallen by 4% and LDL-C, by 3%.

Patients receiving fluvastatin had an average 21% decrease in C-reactive protein, compared with a 3% increase for the placebo group. Interleukin-6 levels also were reduced far more in the fluvastatin group (33% vs a 4% reduction in the placebo group [P<.001]).

The medication was well tolerated. Overall, 6.8% of participants discontinued the study because of side effects, including 16 (6.4%) patients in the fluvastatin group and 18 (7.3%) in the placebo group. (After surgery, 115 [23.1%] of patients in the statin group temporarily discontinued the drug because of an inability to take oral medications for a median of 2 days.)

Rates of increase in creatine kinase of >10× the upper limit of normal (ULN) were similar between the fluvastatin and placebo groups (4% vs 3.2%, respectively). Increases in ALT to >3× ULN were more frequent in the placebo group compared with the fluvastatin group (5.3%, placebo; 3.2%, fluvastatin). No cases of myopathy or rhabdomyolysis were observed in either group.

WHAT’S NEW: Preop statins can be a lifesaver

The initiation of fluvastatin prior to vascular surgery reduced the incidence of cardiovascular events by 50%—a remarkable result. While patients at the highest risk were excluded from the study, those with lower cardiac risk nonetheless benefi ted from statin therapy. Experts have not typically recommended statins in the perioperative period for this patient population. the results of this study make it clear that they should.

CAVEATS: Extended-release formulation may have affected outcome