User login

Disseminated Superficial Actinic Porokeratosis Treated With Ingenol Mebutate Gel 0.05%

Disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis (DSAP) is a chronic condition characterized by numerous atrophic papules and patches with a distinctive peripheral keratotic ridge, typically found on sun-exposed areas.1,2 Treatment of DSAP is warranted not only for cosmetic and symptomatic benefits but also to prevent malignant transformation.3,4 Successful treatment of DSAP often is difficult and frequently requires the use of multiple modalities. Ingenol mebutate gel 0.05% is a topical medication primarily used for the treatment of actinic keratosis (AK) by inducing cell death.5 We report a case of DSAP treated effectively with ingenol mebutate gel 0.05%.

Case Report

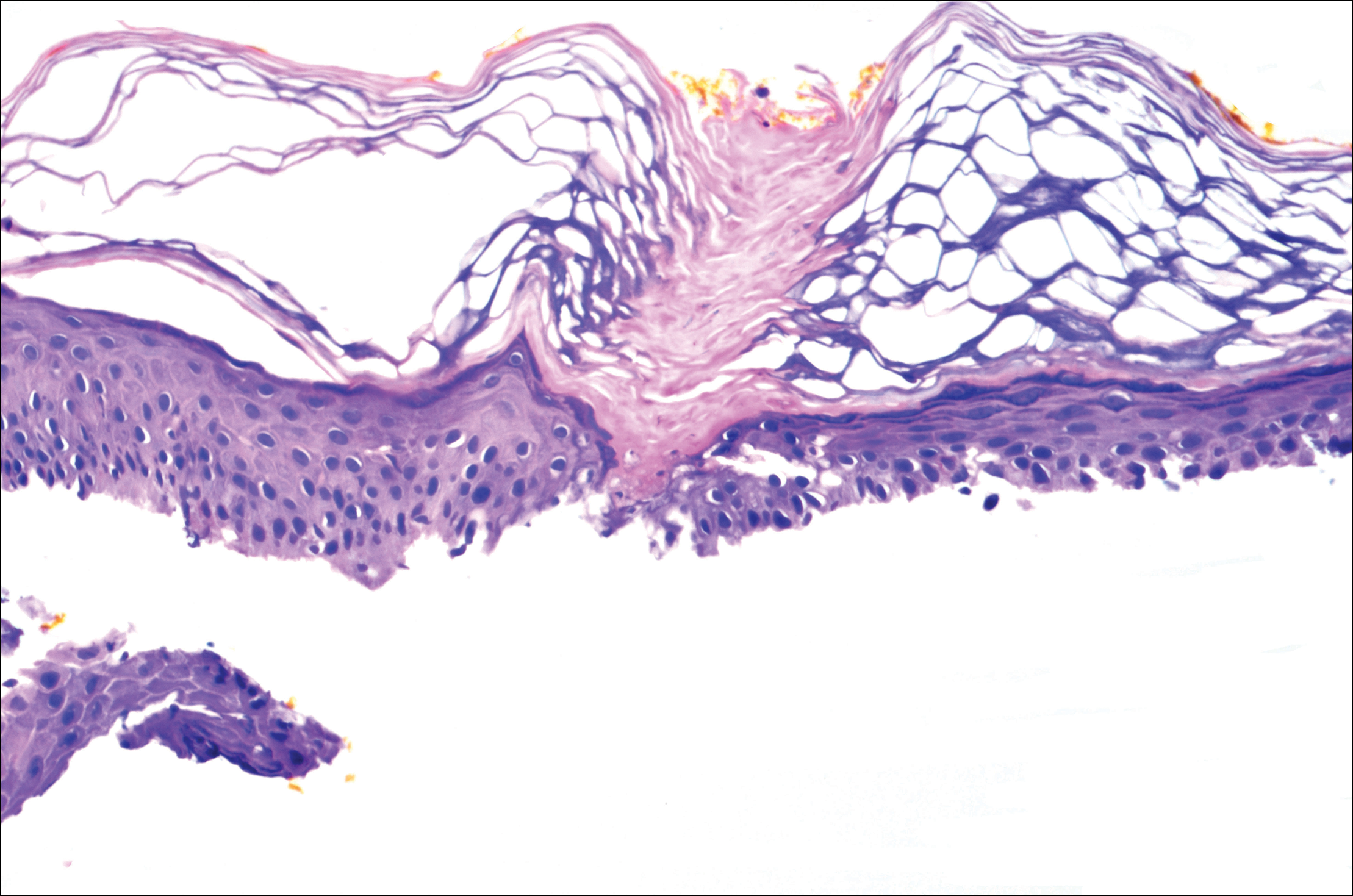

A 37-year-old woman was referred to the dermatology department for counseling for pseudoxanthoma elasticum (PXE), which had been proven on biopsy by an outside dermatologist 2 years prior. Physical examination revealed yellow papules on the neck that were characteristic of PXE, but no lesions were noted on the arms or legs. The only other cutaneous finding was a soft nodule on the right hip consistent with a lipoma. The patient returned to our institution 6 years later with lesions on both lower legs. She reported that these lesions had been present for 3 years and were exacerbated by sun exposure. On physical examination, multiple scattered, erythematous, annular, scaling papules and plaques were noted on the bilateral legs. A biopsy showed the histopathologic findings of DSAP (Figure 1). The patient had no family history of DSAP or PXE.

To determine the best treatment modality, we treated 4 test areas on both upper and lower legs: one with trichloroacetic acid (TCA), one with cryotherapy, one with imiquimod cream 5%, and one with tretinoin cream 0.1%. The patient returned 4 weeks later and showed modest response to TCA, cryotherapy, and tretinoin cream. Because cryotherapy was determined to be most effective, 20 more lesions were frozen at that visit. Over the next 2 years, the patient was treated with TCA, imiquimod cream 5%, and tretinoin cream 0.1%, but all ultimately proved ineffective for DSAP.

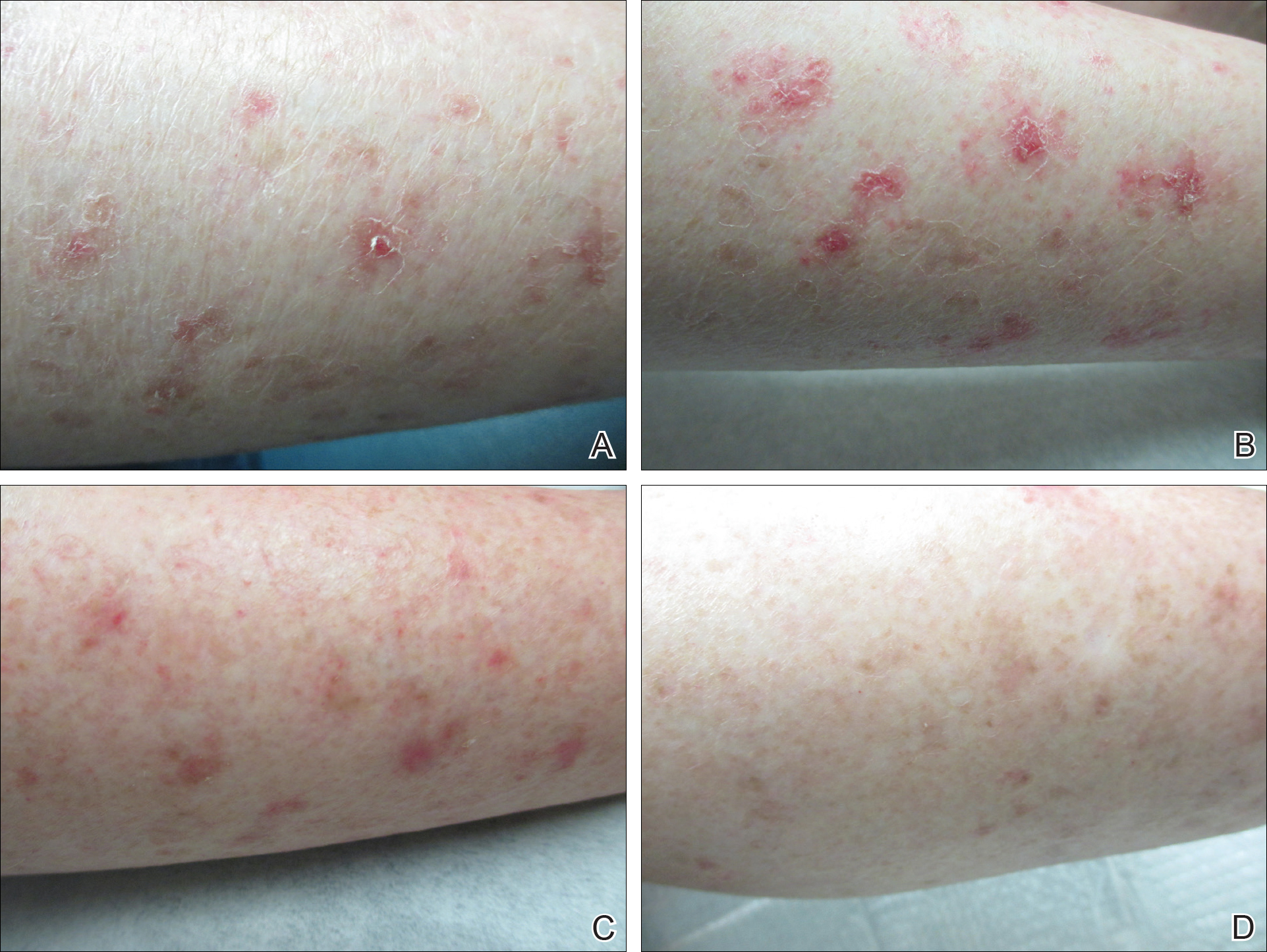

The patient returned 2 years after treatment failure (age 47 years) and was prescribed ingenol mebutate gel 0.05% for 2 days over an area of 25 cm2 on the right lower leg (Figure 2A). She returned for follow-up at days 3, 15, 30, and 60. At day 3, the patient developed an inflammatory response to the medication with moderate erythema and scaling of individual lesions. No vesiculation, pustulation, edema, or ulceration was exhibited (Figure 2B). At day 30, there was a marked reduction in scaling with some postinflammatory erythema (Figure 2C). At day 60, much of the erythema had faded and the scale remained notably reduced (Figure 2D).

Comment

Disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis is the most common subtype of porokeratosis, a keratinization disorder. There are 6 subtypes of porokeratosis identified in the literature: DSAP, disseminated superficial porokeratosis, classic porokeratosis of Mibelli, porokeratosis plantaris palmaris et disseminata, linear porokeratosis, and punctate porokeratosis.6 Disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis has a female predominance (1.8:1 ratio)7 and generally appears in the third or fourth decades of life. Clonal proliferations of atypical keratinocytes have been implicated in the etiology of DSAP; however, the exact pathogenesis is unclear. Risk factors for DSAP include genetic susceptibility (eg, autosomal-dominant inheritance pattern), exposure to UV radiation, and drug-related immunosuppression or immunodeficiency.7 Other proposed etiologic risk factors include trauma and infection.8 Clinical diagnosis of DSAP is confirmed by the histological presence of a cornoid lamella (a thin column ofparakeratotic cells), a thinning epidermis, an absent or thinned granular cell layer, and a prominent dermal lymphocytic infiltrate.9,10

Disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis clinically presents as small atrophic scaly papules and/or patches with raised peripheral ridges symmetrically dispersed on sun-exposed areas of the arms, legs, back, and shoulders. Although these lesions are extensive, they typically spare the mucous membranes, palms, and soles11; only a small percentage of cases report facial lesions,12 which often are asymptomatic but cosmetically bothersome. Additionally, approximately half of patients report symptoms of pruritus and/or stinging,13 thus treatment of DSAP is mainly indicated for symptomatic relief and cosmetic purposes. Malignant degeneration14,15 occurs in approximately 7.5% to 11% of porokeratosis cases,10,16 warranting treatment for preventative measures.

Management of DSAP is dependent on the extent of the disease and the level of concern for malignant transformation. Localized disease can be treated with cryotherapy, CO2 laser, and/or ablative techniques (eg, excision, curettage, dermabrasion) with variable degrees of success but high risk for scarring.1 More extensive disease requires treatment with topical retinoids, topical 5-fluorouracil, imiquimod cream 5%, diclofenac gel 3%, topical vitamin D3 analogues, and photodynamic therapy.1 Several other therapies have been reported in the literature with partial and/or complete success, including systemic retinoids (eg, acitretin), Q-switched ruby laser, Nd:YAG laser, fractional photothermolysis, Grenz rays, pulsed dye laser, fractional photothermolysis, topical corticosteroids, and fluor-hydroxy pulse peel.6 Although there is an extensive array of therapies for DSAP, treatment results are variable with mostly limited success. Successful treatment of DSAP is difficult and often requires the use of multiple modalities.

Ingenol mebutate is the active compound found in the sap of Euphorbia peplus used for the topical treatment of various skin conditions, including AKs.17 Ingenol mebutate gel 0.05% once daily for 2 days has been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the topical treatment of AKs. The mechanism of action of ingenol mebutate in AK therapy is not yet fully understood. In vivo and in vitro models have demonstrated both an induction of local lesion cell death and promotion of lesion-specific inflammatory response.18 When used in the treatment of AKs, ingenol mebutate gel 0.05% may cause a mild to moderate localized inflammatory response (eg, erythema, flaking/scaling, crusting, vesiculation/pustulation, erosion/ulceration, edema).

Our case is a rare report of successful treatment of DSAP with ingenol mebutate gel 0.05%. We found that treatment with ingenol mebutate gel 0.05% resulted in clinical improvement of DSAP lesions with minimal discomfort and good cosmetic response. This 2-day regimen is easy to use and patient friendly, improving medication compliance in such a cumbersome disease. We hope this case suggests that ingenol mebutate gel 0.05% could be a useful treatment alternative for DSAP, but future clinical studies should be conducted.

- Martin-Clavijo A, Kanelleas A, Vlachou C, et al. Porokeratoses. In: Lebwohl M, Heymann WR, Berth-Jones J, et al, eds. Treatment of Skin Disease Comprehensive Therapeutic Strategies. 3rd ed. China: Elsevier Limited; 2010:584-586.

- Rouhani P, Fischer M, Meehan S, et al. Disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis. Dermatology Online J. 2012;18:24.

- Sasson M, Krain AD. Porokeratosis and cutaneous malignancy. a review. Dermatol Surg. 1996;22:339-342.

- Lee HR, Han TY, Son SJ, et al. Squamous cell carcinoma developing within lesions of disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis. Ann Dermatol. 2011;23:536-538.

- Lebwohl M, Swanson N, Anderson LL, et al. Ingenol mebutate gel for actinic keratosis. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1010-1019.

- O’Regan GM, Irvine AD. Porokeratosis. In: Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, Gilchrest BA, et al, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. 8th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Professional; 2012:442-446.

- Sertznig P, von Felbert V, Megahed M. Porokeratosis: present concepts. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2012;26:404-412.

- Brauer JA, Mandal R, Walters R, et al. Disseminated superficial porokeratosis. Dermatology Online J. 2010;16:20.

- Tallon B. Porokeratosis pathology. DermNet New Zealand website. http://www.dermnet.org.nz/pathology/porokeratosis-path.html. Updated December 2016. Accessed January 12, 2017.

- Skupsky H, Skupsky J, Goldenberg G. Disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis: a treatment review [published online October 22, 2010]. J Dermatolog Treat. 2012;23:52-56.

- Spencer LV. Porokeratosis. UpToDate web site. https://eresources.library.mssm.edu:3285/contents/porokeratosis?source=search_result&search=porokeratosis&selectedTitle=1~22. Updated September 1, 2016. Accessed April 3, 2017.

- Sawyer R, Picou KA. Facial presentation of disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis. Ear Nose Throat J. 1989;68:57-59.

- Schwarz T, Seiser A, Gschnait F. Disseminated superficial “actinic” porokeratosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1984;11(4, pt 2):724-730.

- Maubec E, Duvillard P, Margulis A, et al. Common skin cancers in porokeratosis. Br J Dermatol. 2005;152:1389-1391.

- Lee HR, Han TY, Son SJ, et al. Squamous cell carcinoma developing within lesions of disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis [published online November 3, 2011]. Ann Dermatol. 2011;23:536-538.

- Kumari S, Mathur M. Disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis. Nepal J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2010;9:22-24.

- Lebwohl M, Shumack S, Stein Gold L, et al. Long-term follow-up study of ingenol mebutate gel for the treatment of actinic keratosis. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:666-670.

- Stahlhut M, Bertelsen M, Hoyer-Hansen M, et al. Ingenol mebutate: induced cell death patterns in normal and cancer epithelial cells. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11:1181-1192.

Disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis (DSAP) is a chronic condition characterized by numerous atrophic papules and patches with a distinctive peripheral keratotic ridge, typically found on sun-exposed areas.1,2 Treatment of DSAP is warranted not only for cosmetic and symptomatic benefits but also to prevent malignant transformation.3,4 Successful treatment of DSAP often is difficult and frequently requires the use of multiple modalities. Ingenol mebutate gel 0.05% is a topical medication primarily used for the treatment of actinic keratosis (AK) by inducing cell death.5 We report a case of DSAP treated effectively with ingenol mebutate gel 0.05%.

Case Report

A 37-year-old woman was referred to the dermatology department for counseling for pseudoxanthoma elasticum (PXE), which had been proven on biopsy by an outside dermatologist 2 years prior. Physical examination revealed yellow papules on the neck that were characteristic of PXE, but no lesions were noted on the arms or legs. The only other cutaneous finding was a soft nodule on the right hip consistent with a lipoma. The patient returned to our institution 6 years later with lesions on both lower legs. She reported that these lesions had been present for 3 years and were exacerbated by sun exposure. On physical examination, multiple scattered, erythematous, annular, scaling papules and plaques were noted on the bilateral legs. A biopsy showed the histopathologic findings of DSAP (Figure 1). The patient had no family history of DSAP or PXE.

To determine the best treatment modality, we treated 4 test areas on both upper and lower legs: one with trichloroacetic acid (TCA), one with cryotherapy, one with imiquimod cream 5%, and one with tretinoin cream 0.1%. The patient returned 4 weeks later and showed modest response to TCA, cryotherapy, and tretinoin cream. Because cryotherapy was determined to be most effective, 20 more lesions were frozen at that visit. Over the next 2 years, the patient was treated with TCA, imiquimod cream 5%, and tretinoin cream 0.1%, but all ultimately proved ineffective for DSAP.

The patient returned 2 years after treatment failure (age 47 years) and was prescribed ingenol mebutate gel 0.05% for 2 days over an area of 25 cm2 on the right lower leg (Figure 2A). She returned for follow-up at days 3, 15, 30, and 60. At day 3, the patient developed an inflammatory response to the medication with moderate erythema and scaling of individual lesions. No vesiculation, pustulation, edema, or ulceration was exhibited (Figure 2B). At day 30, there was a marked reduction in scaling with some postinflammatory erythema (Figure 2C). At day 60, much of the erythema had faded and the scale remained notably reduced (Figure 2D).

Comment

Disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis is the most common subtype of porokeratosis, a keratinization disorder. There are 6 subtypes of porokeratosis identified in the literature: DSAP, disseminated superficial porokeratosis, classic porokeratosis of Mibelli, porokeratosis plantaris palmaris et disseminata, linear porokeratosis, and punctate porokeratosis.6 Disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis has a female predominance (1.8:1 ratio)7 and generally appears in the third or fourth decades of life. Clonal proliferations of atypical keratinocytes have been implicated in the etiology of DSAP; however, the exact pathogenesis is unclear. Risk factors for DSAP include genetic susceptibility (eg, autosomal-dominant inheritance pattern), exposure to UV radiation, and drug-related immunosuppression or immunodeficiency.7 Other proposed etiologic risk factors include trauma and infection.8 Clinical diagnosis of DSAP is confirmed by the histological presence of a cornoid lamella (a thin column ofparakeratotic cells), a thinning epidermis, an absent or thinned granular cell layer, and a prominent dermal lymphocytic infiltrate.9,10

Disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis clinically presents as small atrophic scaly papules and/or patches with raised peripheral ridges symmetrically dispersed on sun-exposed areas of the arms, legs, back, and shoulders. Although these lesions are extensive, they typically spare the mucous membranes, palms, and soles11; only a small percentage of cases report facial lesions,12 which often are asymptomatic but cosmetically bothersome. Additionally, approximately half of patients report symptoms of pruritus and/or stinging,13 thus treatment of DSAP is mainly indicated for symptomatic relief and cosmetic purposes. Malignant degeneration14,15 occurs in approximately 7.5% to 11% of porokeratosis cases,10,16 warranting treatment for preventative measures.

Management of DSAP is dependent on the extent of the disease and the level of concern for malignant transformation. Localized disease can be treated with cryotherapy, CO2 laser, and/or ablative techniques (eg, excision, curettage, dermabrasion) with variable degrees of success but high risk for scarring.1 More extensive disease requires treatment with topical retinoids, topical 5-fluorouracil, imiquimod cream 5%, diclofenac gel 3%, topical vitamin D3 analogues, and photodynamic therapy.1 Several other therapies have been reported in the literature with partial and/or complete success, including systemic retinoids (eg, acitretin), Q-switched ruby laser, Nd:YAG laser, fractional photothermolysis, Grenz rays, pulsed dye laser, fractional photothermolysis, topical corticosteroids, and fluor-hydroxy pulse peel.6 Although there is an extensive array of therapies for DSAP, treatment results are variable with mostly limited success. Successful treatment of DSAP is difficult and often requires the use of multiple modalities.

Ingenol mebutate is the active compound found in the sap of Euphorbia peplus used for the topical treatment of various skin conditions, including AKs.17 Ingenol mebutate gel 0.05% once daily for 2 days has been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the topical treatment of AKs. The mechanism of action of ingenol mebutate in AK therapy is not yet fully understood. In vivo and in vitro models have demonstrated both an induction of local lesion cell death and promotion of lesion-specific inflammatory response.18 When used in the treatment of AKs, ingenol mebutate gel 0.05% may cause a mild to moderate localized inflammatory response (eg, erythema, flaking/scaling, crusting, vesiculation/pustulation, erosion/ulceration, edema).

Our case is a rare report of successful treatment of DSAP with ingenol mebutate gel 0.05%. We found that treatment with ingenol mebutate gel 0.05% resulted in clinical improvement of DSAP lesions with minimal discomfort and good cosmetic response. This 2-day regimen is easy to use and patient friendly, improving medication compliance in such a cumbersome disease. We hope this case suggests that ingenol mebutate gel 0.05% could be a useful treatment alternative for DSAP, but future clinical studies should be conducted.

Disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis (DSAP) is a chronic condition characterized by numerous atrophic papules and patches with a distinctive peripheral keratotic ridge, typically found on sun-exposed areas.1,2 Treatment of DSAP is warranted not only for cosmetic and symptomatic benefits but also to prevent malignant transformation.3,4 Successful treatment of DSAP often is difficult and frequently requires the use of multiple modalities. Ingenol mebutate gel 0.05% is a topical medication primarily used for the treatment of actinic keratosis (AK) by inducing cell death.5 We report a case of DSAP treated effectively with ingenol mebutate gel 0.05%.

Case Report

A 37-year-old woman was referred to the dermatology department for counseling for pseudoxanthoma elasticum (PXE), which had been proven on biopsy by an outside dermatologist 2 years prior. Physical examination revealed yellow papules on the neck that were characteristic of PXE, but no lesions were noted on the arms or legs. The only other cutaneous finding was a soft nodule on the right hip consistent with a lipoma. The patient returned to our institution 6 years later with lesions on both lower legs. She reported that these lesions had been present for 3 years and were exacerbated by sun exposure. On physical examination, multiple scattered, erythematous, annular, scaling papules and plaques were noted on the bilateral legs. A biopsy showed the histopathologic findings of DSAP (Figure 1). The patient had no family history of DSAP or PXE.

To determine the best treatment modality, we treated 4 test areas on both upper and lower legs: one with trichloroacetic acid (TCA), one with cryotherapy, one with imiquimod cream 5%, and one with tretinoin cream 0.1%. The patient returned 4 weeks later and showed modest response to TCA, cryotherapy, and tretinoin cream. Because cryotherapy was determined to be most effective, 20 more lesions were frozen at that visit. Over the next 2 years, the patient was treated with TCA, imiquimod cream 5%, and tretinoin cream 0.1%, but all ultimately proved ineffective for DSAP.

The patient returned 2 years after treatment failure (age 47 years) and was prescribed ingenol mebutate gel 0.05% for 2 days over an area of 25 cm2 on the right lower leg (Figure 2A). She returned for follow-up at days 3, 15, 30, and 60. At day 3, the patient developed an inflammatory response to the medication with moderate erythema and scaling of individual lesions. No vesiculation, pustulation, edema, or ulceration was exhibited (Figure 2B). At day 30, there was a marked reduction in scaling with some postinflammatory erythema (Figure 2C). At day 60, much of the erythema had faded and the scale remained notably reduced (Figure 2D).

Comment

Disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis is the most common subtype of porokeratosis, a keratinization disorder. There are 6 subtypes of porokeratosis identified in the literature: DSAP, disseminated superficial porokeratosis, classic porokeratosis of Mibelli, porokeratosis plantaris palmaris et disseminata, linear porokeratosis, and punctate porokeratosis.6 Disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis has a female predominance (1.8:1 ratio)7 and generally appears in the third or fourth decades of life. Clonal proliferations of atypical keratinocytes have been implicated in the etiology of DSAP; however, the exact pathogenesis is unclear. Risk factors for DSAP include genetic susceptibility (eg, autosomal-dominant inheritance pattern), exposure to UV radiation, and drug-related immunosuppression or immunodeficiency.7 Other proposed etiologic risk factors include trauma and infection.8 Clinical diagnosis of DSAP is confirmed by the histological presence of a cornoid lamella (a thin column ofparakeratotic cells), a thinning epidermis, an absent or thinned granular cell layer, and a prominent dermal lymphocytic infiltrate.9,10

Disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis clinically presents as small atrophic scaly papules and/or patches with raised peripheral ridges symmetrically dispersed on sun-exposed areas of the arms, legs, back, and shoulders. Although these lesions are extensive, they typically spare the mucous membranes, palms, and soles11; only a small percentage of cases report facial lesions,12 which often are asymptomatic but cosmetically bothersome. Additionally, approximately half of patients report symptoms of pruritus and/or stinging,13 thus treatment of DSAP is mainly indicated for symptomatic relief and cosmetic purposes. Malignant degeneration14,15 occurs in approximately 7.5% to 11% of porokeratosis cases,10,16 warranting treatment for preventative measures.

Management of DSAP is dependent on the extent of the disease and the level of concern for malignant transformation. Localized disease can be treated with cryotherapy, CO2 laser, and/or ablative techniques (eg, excision, curettage, dermabrasion) with variable degrees of success but high risk for scarring.1 More extensive disease requires treatment with topical retinoids, topical 5-fluorouracil, imiquimod cream 5%, diclofenac gel 3%, topical vitamin D3 analogues, and photodynamic therapy.1 Several other therapies have been reported in the literature with partial and/or complete success, including systemic retinoids (eg, acitretin), Q-switched ruby laser, Nd:YAG laser, fractional photothermolysis, Grenz rays, pulsed dye laser, fractional photothermolysis, topical corticosteroids, and fluor-hydroxy pulse peel.6 Although there is an extensive array of therapies for DSAP, treatment results are variable with mostly limited success. Successful treatment of DSAP is difficult and often requires the use of multiple modalities.

Ingenol mebutate is the active compound found in the sap of Euphorbia peplus used for the topical treatment of various skin conditions, including AKs.17 Ingenol mebutate gel 0.05% once daily for 2 days has been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the topical treatment of AKs. The mechanism of action of ingenol mebutate in AK therapy is not yet fully understood. In vivo and in vitro models have demonstrated both an induction of local lesion cell death and promotion of lesion-specific inflammatory response.18 When used in the treatment of AKs, ingenol mebutate gel 0.05% may cause a mild to moderate localized inflammatory response (eg, erythema, flaking/scaling, crusting, vesiculation/pustulation, erosion/ulceration, edema).

Our case is a rare report of successful treatment of DSAP with ingenol mebutate gel 0.05%. We found that treatment with ingenol mebutate gel 0.05% resulted in clinical improvement of DSAP lesions with minimal discomfort and good cosmetic response. This 2-day regimen is easy to use and patient friendly, improving medication compliance in such a cumbersome disease. We hope this case suggests that ingenol mebutate gel 0.05% could be a useful treatment alternative for DSAP, but future clinical studies should be conducted.

- Martin-Clavijo A, Kanelleas A, Vlachou C, et al. Porokeratoses. In: Lebwohl M, Heymann WR, Berth-Jones J, et al, eds. Treatment of Skin Disease Comprehensive Therapeutic Strategies. 3rd ed. China: Elsevier Limited; 2010:584-586.

- Rouhani P, Fischer M, Meehan S, et al. Disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis. Dermatology Online J. 2012;18:24.

- Sasson M, Krain AD. Porokeratosis and cutaneous malignancy. a review. Dermatol Surg. 1996;22:339-342.

- Lee HR, Han TY, Son SJ, et al. Squamous cell carcinoma developing within lesions of disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis. Ann Dermatol. 2011;23:536-538.

- Lebwohl M, Swanson N, Anderson LL, et al. Ingenol mebutate gel for actinic keratosis. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1010-1019.

- O’Regan GM, Irvine AD. Porokeratosis. In: Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, Gilchrest BA, et al, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. 8th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Professional; 2012:442-446.

- Sertznig P, von Felbert V, Megahed M. Porokeratosis: present concepts. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2012;26:404-412.

- Brauer JA, Mandal R, Walters R, et al. Disseminated superficial porokeratosis. Dermatology Online J. 2010;16:20.

- Tallon B. Porokeratosis pathology. DermNet New Zealand website. http://www.dermnet.org.nz/pathology/porokeratosis-path.html. Updated December 2016. Accessed January 12, 2017.

- Skupsky H, Skupsky J, Goldenberg G. Disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis: a treatment review [published online October 22, 2010]. J Dermatolog Treat. 2012;23:52-56.

- Spencer LV. Porokeratosis. UpToDate web site. https://eresources.library.mssm.edu:3285/contents/porokeratosis?source=search_result&search=porokeratosis&selectedTitle=1~22. Updated September 1, 2016. Accessed April 3, 2017.

- Sawyer R, Picou KA. Facial presentation of disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis. Ear Nose Throat J. 1989;68:57-59.

- Schwarz T, Seiser A, Gschnait F. Disseminated superficial “actinic” porokeratosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1984;11(4, pt 2):724-730.

- Maubec E, Duvillard P, Margulis A, et al. Common skin cancers in porokeratosis. Br J Dermatol. 2005;152:1389-1391.

- Lee HR, Han TY, Son SJ, et al. Squamous cell carcinoma developing within lesions of disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis [published online November 3, 2011]. Ann Dermatol. 2011;23:536-538.

- Kumari S, Mathur M. Disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis. Nepal J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2010;9:22-24.

- Lebwohl M, Shumack S, Stein Gold L, et al. Long-term follow-up study of ingenol mebutate gel for the treatment of actinic keratosis. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:666-670.

- Stahlhut M, Bertelsen M, Hoyer-Hansen M, et al. Ingenol mebutate: induced cell death patterns in normal and cancer epithelial cells. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11:1181-1192.

- Martin-Clavijo A, Kanelleas A, Vlachou C, et al. Porokeratoses. In: Lebwohl M, Heymann WR, Berth-Jones J, et al, eds. Treatment of Skin Disease Comprehensive Therapeutic Strategies. 3rd ed. China: Elsevier Limited; 2010:584-586.

- Rouhani P, Fischer M, Meehan S, et al. Disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis. Dermatology Online J. 2012;18:24.

- Sasson M, Krain AD. Porokeratosis and cutaneous malignancy. a review. Dermatol Surg. 1996;22:339-342.

- Lee HR, Han TY, Son SJ, et al. Squamous cell carcinoma developing within lesions of disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis. Ann Dermatol. 2011;23:536-538.

- Lebwohl M, Swanson N, Anderson LL, et al. Ingenol mebutate gel for actinic keratosis. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1010-1019.

- O’Regan GM, Irvine AD. Porokeratosis. In: Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, Gilchrest BA, et al, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. 8th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Professional; 2012:442-446.

- Sertznig P, von Felbert V, Megahed M. Porokeratosis: present concepts. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2012;26:404-412.

- Brauer JA, Mandal R, Walters R, et al. Disseminated superficial porokeratosis. Dermatology Online J. 2010;16:20.

- Tallon B. Porokeratosis pathology. DermNet New Zealand website. http://www.dermnet.org.nz/pathology/porokeratosis-path.html. Updated December 2016. Accessed January 12, 2017.

- Skupsky H, Skupsky J, Goldenberg G. Disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis: a treatment review [published online October 22, 2010]. J Dermatolog Treat. 2012;23:52-56.

- Spencer LV. Porokeratosis. UpToDate web site. https://eresources.library.mssm.edu:3285/contents/porokeratosis?source=search_result&search=porokeratosis&selectedTitle=1~22. Updated September 1, 2016. Accessed April 3, 2017.

- Sawyer R, Picou KA. Facial presentation of disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis. Ear Nose Throat J. 1989;68:57-59.

- Schwarz T, Seiser A, Gschnait F. Disseminated superficial “actinic” porokeratosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1984;11(4, pt 2):724-730.

- Maubec E, Duvillard P, Margulis A, et al. Common skin cancers in porokeratosis. Br J Dermatol. 2005;152:1389-1391.

- Lee HR, Han TY, Son SJ, et al. Squamous cell carcinoma developing within lesions of disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis [published online November 3, 2011]. Ann Dermatol. 2011;23:536-538.

- Kumari S, Mathur M. Disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis. Nepal J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2010;9:22-24.

- Lebwohl M, Shumack S, Stein Gold L, et al. Long-term follow-up study of ingenol mebutate gel for the treatment of actinic keratosis. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:666-670.

- Stahlhut M, Bertelsen M, Hoyer-Hansen M, et al. Ingenol mebutate: induced cell death patterns in normal and cancer epithelial cells. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11:1181-1192.

Practice Points

- Disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis (DSAP) is an uncommon skin condition consisting of multiple annular hyperkeratotic lesions on sun-exposed areas.

- Treatment of DSAP is necessary due to its potential for progression to malignancy.

- Consider ingenol mebutate gel 0.05% for the treatment of DSAP on the arms and legs.