User login

8 common questions about newborn circumcision

In the United States, circumcision is the fourth most common surgical procedure—behind cataract removal, cesarean delivery, and joint replacement.1 This operation, which dates to ancient times, is chosen for medical, personal, or religious reasons. It is performed on 77% of males born in the United States and on 42% of those born elsewhere who are living in this country.2 Whether it is performed depends not only on the parents’ race, ethnic background, and religion but also on region: US circumcision rates range from 74% in the Midwest to 30% in the West, and in between are the Northeast (67%) and the South (61%).3

Circumcision is not without controversy. Some claim that it is unnecessary cosmetic surgery, that it is genital mutilation, that the patient cannot choose it or object to it, or that it decreases sexual satisfaction.

In this article, I review 8 common questions about circumcision and provide data-based answers to them.

1. Should a newborn be circumcised?

For many years, the medical benefits of circumcision were scientifically ambiguous. With no clear answers, some thought that parents should base their decision for or against circumcision not on any potential medical benefit but rather on their family or religious tradition, or on a social standard, that is, what the majority of families in their community do.

Over the past 20 years, a growing body of evidence has demonstrated real medical benefits of circumcision. In 2012, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), which previously had been neutral on the subject, issued a task force report concluding that the health benefits of circumcision outweigh its risks and justify access to the procedure.3,4 However, the report stopped short of recommending circumcision.

Opponents have expressed several concerns about circumcision. First, they say, it is painful and unnecessary, and performing it when life has just begun takes the decision away from the adult-to-be, who may want to be uncircumcised as an adult but will have no recourse. Second, they say circumcision will diminish the adult’s sexual pleasure. However, there is no proof this occurs, and it is unclear how the claim could be adequately verified.5

Health benefits of circumcision3

- Prevention of phimosis and balanoposthitis (inflammation of glans and foreskin), penile retraction disorders, and penile cancer

- Fewer infant urinary tract infections

- Decreased spread of human papillomavirus–related disease, including cervical cancer and its precursors, to sexual partners

- Lower risk of acquiring, harboring, and spreading human immunodeficiency virus infection, herpes virus infection, and other sexually transmitted diseases

- Easier genital hygiene

- No need for circumcision later in life, when the procedure is more involved

2. What is the best analgesia for circumcision?

Although in decades past circumcision was often performed without any analgesia, in the United States analgesia is now standard of care. The AAP Task Force on Circumcision formalized this standard in a 2012 policy statement.4 For newborn circumcision, analgesia can be given in the form of analgesic cream, penile ring block, or dorsal nerve block.

Analgesic EMLA cream (a mixture of local anesthetics such as lidocaine 2.5%/prilocaine 2.5%) is easy to use but is minimally effective in relieving circumcision pain,6 although some investigators have reported it is efficacious compared with placebo.7 When used, the analgesic cream is applied 30 to 60 minutes before circumcision.

Both penile ring block and dorsal nerve block with 1% lidocaine are easy to administer and are very effective.8,9 They are best used with buffered lidocaine, which partially relieves the burning that occurs with injection. With both methods, the smaller the needle used (preferably 30 gauge), the better.

These 2 block methods have different injection sites. For the ring block, small amounts of lidocaine (1 to 1.5 mL) are given in a series of injections around the entire circumference of the base of the penis. The dorsal block targets the 2 dorsal nerves located at 10 o’clock and 2 o’clock at the base of the penis. Epinephrine, given its vasoconstrictive properties and the potential for necrosis, should never be used with local analgesia for penile infiltration.

Analgesia can be supplemented with comfort measures, such as a pacifier, sugar water, gentle rubbing on the forehead, and soothing speech.10

Related article:

Circumcision impedes viral disease. Will opposition fade?

3. What conditions are required for safe circumcision?

As circumcision is not medically required and need not occur in the days immediately after birth, it should be performed only when conditions are optimal:

- A pediatrician or other practitioner must first examine the newborn.

- The newborn must be full-term, healthy, and stable.

- The best time to circumcise a baby born prematurely is right before discharge from the intensive care nursery.

- The penis must be of normal size and without anatomical defect—no micropenis, hypospadias, or penoscrotal webbing.

- The lower abdominal fat pad must not be so large that it will cause the shaft’s skin to cover the exposed penile head.

- If there is a family history of a bleeding disorder, the newborn must be evaluated for the disorder before the circumcision.

- The newborn must have received his vitamin K shot.

4. What is the best circumcision method?

Circumcision can be performed with the Gomco circumcision clamp, the Mogen circumcision clamp, or the PlastiBell circumcision device. Each device works well, provides excellent results, and has its pluses and minuses. Practitioners should use the device with which they are most familiar and comfortable, which likely will be the device they used in training.

In the United States, the Gomco clamp is perhaps the most commonly used device. It provides good cosmetic results, and its metal “bell” protects the entire head of the penis. Of the 3 methods, however, it is the most difficult—the partially cut foreskin must be threaded between the bell and the clamp frame before the clamp is tightened. In many cases, too, there is bleeding at the penile frenulum.

The Mogen clamp, another commonly used device, also is used in traditional Jewish circumcisions. Of the 3 methods, it is the quickest, produces the best hemostasis, and is associated with the least discomfort.10 To those unfamiliar with the method, there may seem to be a potential for amputation of the head of the penis, but actually there virtually is no risk, as an indentation on the penile side of the clamp protects the penile head.

The PlastiBell device is very easy to use but must stay on until the foreskin becomes necrotic and the bell and foreskin fall off on their own—a process that takes 7 to 10 days. Many parents dislike this method because its final result is not immediate and they have to contend with a medical implement during their newborn’s first week home.

Electrocautery is not recommended. Some clinicians, especially urologists, use electrocautery as the cutting mechanism for circumcision. A review of the literature, however, reveals that electrocautery has not been studied head-to-head against traditional techniques, and that various significant complications—transected penile head, severe burns, meatal stenosis—have been reported.11,12 It is certainly not a mainstream procedure for neonatal circumcision.

Evaluate penile anatomy for abnormalities

Before performing any circumcision, the head of the penis should be examined to rule out hypospadias or other penile abnormalities. This is because the foreskin is utilized in certain penile repair procedures. The pediatrician should perform an initial examination of the penis at the formal newborn physical within 24 hours of delivery. The clinician performing the circumcision should re-examine the penis just before the procedure is begun—by pushing back the foreskin as much as possible—as well as during the procedure, once the foreskin is lifted off the penile head but before the foreskin is excised.

Read about how to ensure the best outcome of circumcision.

5. When is the best time to perform a circumcision?

The medical literature provides no firm answer to this question. The younger the baby, the easier it is to perform a circumcision as a simple procedure with local anesthesia. The older the baby, the larger the penis and the more aware the baby will be of his surroundings. Both these factors will make the procedure more difficult.

Most clinicians would be reluctant to perform a circumcision in the office or clinic after the baby is 6 to 8 weeks old. If a family desires their son to be circumcised after that time—or a medical condition precludes earlier circumcision—the procedure is best performed by a pediatric urologist in the operating room.

Related article:

Circumcision accident: $1.3M verdict

6. What are the potential complications of circumcision?

The rate of circumcision complications is very low: 0.2%.13 That being said, the 3 most common types of complications are postoperative bleeding, infection, and damage to the penis.

Far and away the most common complication is postoperative bleeding , usually at the frenulum of the head of the penis (the 6 o’clock position). In most cases, the bleeding is light to moderate. It is controlled with direct pressure applied for several minutes, the use of processed gelatin (Gelfoam) or cellulose (Surgicel), sparing use of silver nitrate, or placement of a polyglycolic acid (Vicryl) 5-0 suture.

Infection, an unusual occurrence, is seen within 24 to 72 hours after circumcision. It is marked by swelling, redness, and a foul-smelling mucus discharge. This discharge must be differentiated from dried fibrin, which is commonly seen on the head of the penis in the days after circumcision but has no odor or association with erythema, fever, or infant fussiness. True infection should be treated, in collaboration with the child’s pediatrician, with a staphylococcal-sensitive penicillin (such as dicloxacillin).

More serious is damage to the penis, which ranges from accidental dilation of the meatus to partial amputation of the penile glans. Any such injury should immediately prompt a consultation with a pediatric urologist.

More of a nuisance than a complication is the sliding of the penile shaft’s skin up and over the glans. This is a relatively frequent occurrence after normal, successful circumcisions. Parents of an affected newborn should be instructed to gently slide the skin back until the head of the penis is completely exposed again. After several days, the skin will adhere to its proper position on the shaft.

- Just before the procedure, have a face-to-face discussion with the parents. Confirm that they want the circumcision done, explain exactly what it entails, and let them know they will receive complete aftercare instructions.

- Make sure one of the parents signs the consent form.

- Circumcise the right baby! Check the identification bracelet and confirm that the newborn’s hospital and chart numbers match.

- Prevent excessive hip movement by securing the baby's legs. The usual solution is a specially designed plastic restraint board with Velcro straps for the legs.

- Examine the infant’s penile anatomy prior to the procedure to make certain it is normal.

- For pain relief, administer enough analgesia, as either dorsal nerve block or penile ring block (the best methods). Before injection, draw the plunger of the syringe back to make certain that the needle is not in a blood vessel.

- During the procedure, make sure the entire membranous layer of foreskin covering the head of the penis is separated from the glans.

- Watch the penis for several minutes after the circumcision to make sure there is no bleeding.

7. What is a Jewish ritual circumcision?

For their newborn’s circumcision, Jewish parents may choose a bris ceremony, formally called a brit milah, in fulfillment of religious tradition. The ceremony involves a brief religious service, circumcision with the traditional Mogen clamp, a special blessing, and an official religious naming rite. The bris traditionally is performed by a mohel, a rabbi or other religious official trained in circumcision. Many parents have the bris done by a mohel who is a medical doctor. In the United States, the availability of both types of mohels varies.

8. Who should perform circumcisions—obstetricians or pediatricians?

The answer to this question depends on where you practice. In some communities or hospitals, the obstetrician performs newborn circumcision, while in other places the pediatrician does. In addition, depending on local circumstances or the specific population involved, circumcisions may be performed by a pediatric urologist, nurse practitioner, or even out of hospital by a trained religiously affiliated practitioner.

Obstetricians began doing circumcisions for 2 reasons. First, obstetricians are surgically trained whereas pediatricians are not. It was therefore thought to be more appropriate for obstetricians to do this minor surgical procedure. Second, circumcisions used to be done right in the delivery room shortly after delivery. It was thought that the crying induced by performing the circumcision helped clear the baby’s lungs and invigorated sluggish babies. Now, however, in-hospital circumcisions are usually done in the days following delivery, after the baby has had the opportunity to undergo his first physical examination to make sure that all is well and that the penile anatomy is normal.

Clinician experience, proper protocol contribute to a safe procedure

In the United States, a large percentage of male infants are circumcised. Although circumcision has known medical benefits, the procedure generally is performed for family, religious, or cultural reasons. Circumcision is a safe and straightforward procedure but has its risks and potential complications. As with most surgeries, the best outcomes are achieved by practitioners who are well trained, who perform the procedure under supervision until their experience is sufficient, and who follow correct protocol during the entire operation.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Dallas ME. The 10 most common surgeries in the US. Healthgrades website. https://www.healthgrades.com/explore/the-10-most-common-surgeries-in-the-us. Reviewed August 15, 2017. Accessed October 2, 2017.

- Laumann EO, Masi CM, Zuckerman EW. Circumcision in the United States: prevalence, prophylactic effects, and sexual practice. JAMA. 1997;277(13):1052–1057.

- American Academy of Pediatrics Task Force on Circumcision. Male circumcision. Pediatrics. 2012;130(3):e756–e785.

- American Academy of Pediatrics Task Force on Circumcision. Circumcision policy statement. Pediatrics. 2012;130(3):585–586.

- Morris BJ, Krieger JN. Does male circumcision affect sexual function, sensitivity, or satisfaction? A systematic review. J Sex Med. 2013;10(11):2644–2657.

- Howard FM, Howard CR, Fortune K, Generelli P, Zolnoun D, tenHoopen C. A randomized, placebo-controlled comparison of EMLA and dorsal penile nerve block for pain relief during neonatal circumcision. Prim Care Update Ob Gyns. 1998;5(4):196.

- Taddio A, Stevens B, Craig K, et al. Efficacy and safety of lidocaine-prilocaine cream for pain during circumcision. N Engl J Med. 1997;336(17):1197–1201.

- Lander J, Brady-Fryer B, Metcalfe JB, Nazarali S, Muttitt S. Comparison of ring block, dorsal penile nerve block, and topical anesthesia for neonatal circumcision: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 1997;278(24):2157–2162.

- Hardwick-Smith S, Mastrobattista JM, Wallace PA, Ritchey ML. Ring block for neonatal circumcision. Obstet Gynecol. 1998;91(6):930–934.

- Kaufman GE, Cimo S, Miller LW, Blass EM. An evaluation of the effects of sucrose on neonatal pain with 2 commonly used circumcision methods. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;186(3):564–568.

- Tucker SC, Cerqueiro J, Sterne GD, Bracka A. Circumcision: a refined technique and 5 year review. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2001;83(2):121–125.

- Fraser ID, Tjoe J. Circumcision using bipolar scissors can be a safe and simple operation. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2000;82(3):190–191.

- Wiswell TE, Geschke DW. Risks from circumcision during the first month of life compared with those for uncircumcised boys. Pediatrics. 1989;83(6):1011–1015.

In the United States, circumcision is the fourth most common surgical procedure—behind cataract removal, cesarean delivery, and joint replacement.1 This operation, which dates to ancient times, is chosen for medical, personal, or religious reasons. It is performed on 77% of males born in the United States and on 42% of those born elsewhere who are living in this country.2 Whether it is performed depends not only on the parents’ race, ethnic background, and religion but also on region: US circumcision rates range from 74% in the Midwest to 30% in the West, and in between are the Northeast (67%) and the South (61%).3

Circumcision is not without controversy. Some claim that it is unnecessary cosmetic surgery, that it is genital mutilation, that the patient cannot choose it or object to it, or that it decreases sexual satisfaction.

In this article, I review 8 common questions about circumcision and provide data-based answers to them.

1. Should a newborn be circumcised?

For many years, the medical benefits of circumcision were scientifically ambiguous. With no clear answers, some thought that parents should base their decision for or against circumcision not on any potential medical benefit but rather on their family or religious tradition, or on a social standard, that is, what the majority of families in their community do.

Over the past 20 years, a growing body of evidence has demonstrated real medical benefits of circumcision. In 2012, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), which previously had been neutral on the subject, issued a task force report concluding that the health benefits of circumcision outweigh its risks and justify access to the procedure.3,4 However, the report stopped short of recommending circumcision.

Opponents have expressed several concerns about circumcision. First, they say, it is painful and unnecessary, and performing it when life has just begun takes the decision away from the adult-to-be, who may want to be uncircumcised as an adult but will have no recourse. Second, they say circumcision will diminish the adult’s sexual pleasure. However, there is no proof this occurs, and it is unclear how the claim could be adequately verified.5

Health benefits of circumcision3

- Prevention of phimosis and balanoposthitis (inflammation of glans and foreskin), penile retraction disorders, and penile cancer

- Fewer infant urinary tract infections

- Decreased spread of human papillomavirus–related disease, including cervical cancer and its precursors, to sexual partners

- Lower risk of acquiring, harboring, and spreading human immunodeficiency virus infection, herpes virus infection, and other sexually transmitted diseases

- Easier genital hygiene

- No need for circumcision later in life, when the procedure is more involved

2. What is the best analgesia for circumcision?

Although in decades past circumcision was often performed without any analgesia, in the United States analgesia is now standard of care. The AAP Task Force on Circumcision formalized this standard in a 2012 policy statement.4 For newborn circumcision, analgesia can be given in the form of analgesic cream, penile ring block, or dorsal nerve block.

Analgesic EMLA cream (a mixture of local anesthetics such as lidocaine 2.5%/prilocaine 2.5%) is easy to use but is minimally effective in relieving circumcision pain,6 although some investigators have reported it is efficacious compared with placebo.7 When used, the analgesic cream is applied 30 to 60 minutes before circumcision.

Both penile ring block and dorsal nerve block with 1% lidocaine are easy to administer and are very effective.8,9 They are best used with buffered lidocaine, which partially relieves the burning that occurs with injection. With both methods, the smaller the needle used (preferably 30 gauge), the better.

These 2 block methods have different injection sites. For the ring block, small amounts of lidocaine (1 to 1.5 mL) are given in a series of injections around the entire circumference of the base of the penis. The dorsal block targets the 2 dorsal nerves located at 10 o’clock and 2 o’clock at the base of the penis. Epinephrine, given its vasoconstrictive properties and the potential for necrosis, should never be used with local analgesia for penile infiltration.

Analgesia can be supplemented with comfort measures, such as a pacifier, sugar water, gentle rubbing on the forehead, and soothing speech.10

Related article:

Circumcision impedes viral disease. Will opposition fade?

3. What conditions are required for safe circumcision?

As circumcision is not medically required and need not occur in the days immediately after birth, it should be performed only when conditions are optimal:

- A pediatrician or other practitioner must first examine the newborn.

- The newborn must be full-term, healthy, and stable.

- The best time to circumcise a baby born prematurely is right before discharge from the intensive care nursery.

- The penis must be of normal size and without anatomical defect—no micropenis, hypospadias, or penoscrotal webbing.

- The lower abdominal fat pad must not be so large that it will cause the shaft’s skin to cover the exposed penile head.

- If there is a family history of a bleeding disorder, the newborn must be evaluated for the disorder before the circumcision.

- The newborn must have received his vitamin K shot.

4. What is the best circumcision method?

Circumcision can be performed with the Gomco circumcision clamp, the Mogen circumcision clamp, or the PlastiBell circumcision device. Each device works well, provides excellent results, and has its pluses and minuses. Practitioners should use the device with which they are most familiar and comfortable, which likely will be the device they used in training.

In the United States, the Gomco clamp is perhaps the most commonly used device. It provides good cosmetic results, and its metal “bell” protects the entire head of the penis. Of the 3 methods, however, it is the most difficult—the partially cut foreskin must be threaded between the bell and the clamp frame before the clamp is tightened. In many cases, too, there is bleeding at the penile frenulum.

The Mogen clamp, another commonly used device, also is used in traditional Jewish circumcisions. Of the 3 methods, it is the quickest, produces the best hemostasis, and is associated with the least discomfort.10 To those unfamiliar with the method, there may seem to be a potential for amputation of the head of the penis, but actually there virtually is no risk, as an indentation on the penile side of the clamp protects the penile head.

The PlastiBell device is very easy to use but must stay on until the foreskin becomes necrotic and the bell and foreskin fall off on their own—a process that takes 7 to 10 days. Many parents dislike this method because its final result is not immediate and they have to contend with a medical implement during their newborn’s first week home.

Electrocautery is not recommended. Some clinicians, especially urologists, use electrocautery as the cutting mechanism for circumcision. A review of the literature, however, reveals that electrocautery has not been studied head-to-head against traditional techniques, and that various significant complications—transected penile head, severe burns, meatal stenosis—have been reported.11,12 It is certainly not a mainstream procedure for neonatal circumcision.

Evaluate penile anatomy for abnormalities

Before performing any circumcision, the head of the penis should be examined to rule out hypospadias or other penile abnormalities. This is because the foreskin is utilized in certain penile repair procedures. The pediatrician should perform an initial examination of the penis at the formal newborn physical within 24 hours of delivery. The clinician performing the circumcision should re-examine the penis just before the procedure is begun—by pushing back the foreskin as much as possible—as well as during the procedure, once the foreskin is lifted off the penile head but before the foreskin is excised.

Read about how to ensure the best outcome of circumcision.

5. When is the best time to perform a circumcision?

The medical literature provides no firm answer to this question. The younger the baby, the easier it is to perform a circumcision as a simple procedure with local anesthesia. The older the baby, the larger the penis and the more aware the baby will be of his surroundings. Both these factors will make the procedure more difficult.

Most clinicians would be reluctant to perform a circumcision in the office or clinic after the baby is 6 to 8 weeks old. If a family desires their son to be circumcised after that time—or a medical condition precludes earlier circumcision—the procedure is best performed by a pediatric urologist in the operating room.

Related article:

Circumcision accident: $1.3M verdict

6. What are the potential complications of circumcision?

The rate of circumcision complications is very low: 0.2%.13 That being said, the 3 most common types of complications are postoperative bleeding, infection, and damage to the penis.

Far and away the most common complication is postoperative bleeding , usually at the frenulum of the head of the penis (the 6 o’clock position). In most cases, the bleeding is light to moderate. It is controlled with direct pressure applied for several minutes, the use of processed gelatin (Gelfoam) or cellulose (Surgicel), sparing use of silver nitrate, or placement of a polyglycolic acid (Vicryl) 5-0 suture.

Infection, an unusual occurrence, is seen within 24 to 72 hours after circumcision. It is marked by swelling, redness, and a foul-smelling mucus discharge. This discharge must be differentiated from dried fibrin, which is commonly seen on the head of the penis in the days after circumcision but has no odor or association with erythema, fever, or infant fussiness. True infection should be treated, in collaboration with the child’s pediatrician, with a staphylococcal-sensitive penicillin (such as dicloxacillin).

More serious is damage to the penis, which ranges from accidental dilation of the meatus to partial amputation of the penile glans. Any such injury should immediately prompt a consultation with a pediatric urologist.

More of a nuisance than a complication is the sliding of the penile shaft’s skin up and over the glans. This is a relatively frequent occurrence after normal, successful circumcisions. Parents of an affected newborn should be instructed to gently slide the skin back until the head of the penis is completely exposed again. After several days, the skin will adhere to its proper position on the shaft.

- Just before the procedure, have a face-to-face discussion with the parents. Confirm that they want the circumcision done, explain exactly what it entails, and let them know they will receive complete aftercare instructions.

- Make sure one of the parents signs the consent form.

- Circumcise the right baby! Check the identification bracelet and confirm that the newborn’s hospital and chart numbers match.

- Prevent excessive hip movement by securing the baby's legs. The usual solution is a specially designed plastic restraint board with Velcro straps for the legs.

- Examine the infant’s penile anatomy prior to the procedure to make certain it is normal.

- For pain relief, administer enough analgesia, as either dorsal nerve block or penile ring block (the best methods). Before injection, draw the plunger of the syringe back to make certain that the needle is not in a blood vessel.

- During the procedure, make sure the entire membranous layer of foreskin covering the head of the penis is separated from the glans.

- Watch the penis for several minutes after the circumcision to make sure there is no bleeding.

7. What is a Jewish ritual circumcision?

For their newborn’s circumcision, Jewish parents may choose a bris ceremony, formally called a brit milah, in fulfillment of religious tradition. The ceremony involves a brief religious service, circumcision with the traditional Mogen clamp, a special blessing, and an official religious naming rite. The bris traditionally is performed by a mohel, a rabbi or other religious official trained in circumcision. Many parents have the bris done by a mohel who is a medical doctor. In the United States, the availability of both types of mohels varies.

8. Who should perform circumcisions—obstetricians or pediatricians?

The answer to this question depends on where you practice. In some communities or hospitals, the obstetrician performs newborn circumcision, while in other places the pediatrician does. In addition, depending on local circumstances or the specific population involved, circumcisions may be performed by a pediatric urologist, nurse practitioner, or even out of hospital by a trained religiously affiliated practitioner.

Obstetricians began doing circumcisions for 2 reasons. First, obstetricians are surgically trained whereas pediatricians are not. It was therefore thought to be more appropriate for obstetricians to do this minor surgical procedure. Second, circumcisions used to be done right in the delivery room shortly after delivery. It was thought that the crying induced by performing the circumcision helped clear the baby’s lungs and invigorated sluggish babies. Now, however, in-hospital circumcisions are usually done in the days following delivery, after the baby has had the opportunity to undergo his first physical examination to make sure that all is well and that the penile anatomy is normal.

Clinician experience, proper protocol contribute to a safe procedure

In the United States, a large percentage of male infants are circumcised. Although circumcision has known medical benefits, the procedure generally is performed for family, religious, or cultural reasons. Circumcision is a safe and straightforward procedure but has its risks and potential complications. As with most surgeries, the best outcomes are achieved by practitioners who are well trained, who perform the procedure under supervision until their experience is sufficient, and who follow correct protocol during the entire operation.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

In the United States, circumcision is the fourth most common surgical procedure—behind cataract removal, cesarean delivery, and joint replacement.1 This operation, which dates to ancient times, is chosen for medical, personal, or religious reasons. It is performed on 77% of males born in the United States and on 42% of those born elsewhere who are living in this country.2 Whether it is performed depends not only on the parents’ race, ethnic background, and religion but also on region: US circumcision rates range from 74% in the Midwest to 30% in the West, and in between are the Northeast (67%) and the South (61%).3

Circumcision is not without controversy. Some claim that it is unnecessary cosmetic surgery, that it is genital mutilation, that the patient cannot choose it or object to it, or that it decreases sexual satisfaction.

In this article, I review 8 common questions about circumcision and provide data-based answers to them.

1. Should a newborn be circumcised?

For many years, the medical benefits of circumcision were scientifically ambiguous. With no clear answers, some thought that parents should base their decision for or against circumcision not on any potential medical benefit but rather on their family or religious tradition, or on a social standard, that is, what the majority of families in their community do.

Over the past 20 years, a growing body of evidence has demonstrated real medical benefits of circumcision. In 2012, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), which previously had been neutral on the subject, issued a task force report concluding that the health benefits of circumcision outweigh its risks and justify access to the procedure.3,4 However, the report stopped short of recommending circumcision.

Opponents have expressed several concerns about circumcision. First, they say, it is painful and unnecessary, and performing it when life has just begun takes the decision away from the adult-to-be, who may want to be uncircumcised as an adult but will have no recourse. Second, they say circumcision will diminish the adult’s sexual pleasure. However, there is no proof this occurs, and it is unclear how the claim could be adequately verified.5

Health benefits of circumcision3

- Prevention of phimosis and balanoposthitis (inflammation of glans and foreskin), penile retraction disorders, and penile cancer

- Fewer infant urinary tract infections

- Decreased spread of human papillomavirus–related disease, including cervical cancer and its precursors, to sexual partners

- Lower risk of acquiring, harboring, and spreading human immunodeficiency virus infection, herpes virus infection, and other sexually transmitted diseases

- Easier genital hygiene

- No need for circumcision later in life, when the procedure is more involved

2. What is the best analgesia for circumcision?

Although in decades past circumcision was often performed without any analgesia, in the United States analgesia is now standard of care. The AAP Task Force on Circumcision formalized this standard in a 2012 policy statement.4 For newborn circumcision, analgesia can be given in the form of analgesic cream, penile ring block, or dorsal nerve block.

Analgesic EMLA cream (a mixture of local anesthetics such as lidocaine 2.5%/prilocaine 2.5%) is easy to use but is minimally effective in relieving circumcision pain,6 although some investigators have reported it is efficacious compared with placebo.7 When used, the analgesic cream is applied 30 to 60 minutes before circumcision.

Both penile ring block and dorsal nerve block with 1% lidocaine are easy to administer and are very effective.8,9 They are best used with buffered lidocaine, which partially relieves the burning that occurs with injection. With both methods, the smaller the needle used (preferably 30 gauge), the better.

These 2 block methods have different injection sites. For the ring block, small amounts of lidocaine (1 to 1.5 mL) are given in a series of injections around the entire circumference of the base of the penis. The dorsal block targets the 2 dorsal nerves located at 10 o’clock and 2 o’clock at the base of the penis. Epinephrine, given its vasoconstrictive properties and the potential for necrosis, should never be used with local analgesia for penile infiltration.

Analgesia can be supplemented with comfort measures, such as a pacifier, sugar water, gentle rubbing on the forehead, and soothing speech.10

Related article:

Circumcision impedes viral disease. Will opposition fade?

3. What conditions are required for safe circumcision?

As circumcision is not medically required and need not occur in the days immediately after birth, it should be performed only when conditions are optimal:

- A pediatrician or other practitioner must first examine the newborn.

- The newborn must be full-term, healthy, and stable.

- The best time to circumcise a baby born prematurely is right before discharge from the intensive care nursery.

- The penis must be of normal size and without anatomical defect—no micropenis, hypospadias, or penoscrotal webbing.

- The lower abdominal fat pad must not be so large that it will cause the shaft’s skin to cover the exposed penile head.

- If there is a family history of a bleeding disorder, the newborn must be evaluated for the disorder before the circumcision.

- The newborn must have received his vitamin K shot.

4. What is the best circumcision method?

Circumcision can be performed with the Gomco circumcision clamp, the Mogen circumcision clamp, or the PlastiBell circumcision device. Each device works well, provides excellent results, and has its pluses and minuses. Practitioners should use the device with which they are most familiar and comfortable, which likely will be the device they used in training.

In the United States, the Gomco clamp is perhaps the most commonly used device. It provides good cosmetic results, and its metal “bell” protects the entire head of the penis. Of the 3 methods, however, it is the most difficult—the partially cut foreskin must be threaded between the bell and the clamp frame before the clamp is tightened. In many cases, too, there is bleeding at the penile frenulum.

The Mogen clamp, another commonly used device, also is used in traditional Jewish circumcisions. Of the 3 methods, it is the quickest, produces the best hemostasis, and is associated with the least discomfort.10 To those unfamiliar with the method, there may seem to be a potential for amputation of the head of the penis, but actually there virtually is no risk, as an indentation on the penile side of the clamp protects the penile head.

The PlastiBell device is very easy to use but must stay on until the foreskin becomes necrotic and the bell and foreskin fall off on their own—a process that takes 7 to 10 days. Many parents dislike this method because its final result is not immediate and they have to contend with a medical implement during their newborn’s first week home.

Electrocautery is not recommended. Some clinicians, especially urologists, use electrocautery as the cutting mechanism for circumcision. A review of the literature, however, reveals that electrocautery has not been studied head-to-head against traditional techniques, and that various significant complications—transected penile head, severe burns, meatal stenosis—have been reported.11,12 It is certainly not a mainstream procedure for neonatal circumcision.

Evaluate penile anatomy for abnormalities

Before performing any circumcision, the head of the penis should be examined to rule out hypospadias or other penile abnormalities. This is because the foreskin is utilized in certain penile repair procedures. The pediatrician should perform an initial examination of the penis at the formal newborn physical within 24 hours of delivery. The clinician performing the circumcision should re-examine the penis just before the procedure is begun—by pushing back the foreskin as much as possible—as well as during the procedure, once the foreskin is lifted off the penile head but before the foreskin is excised.

Read about how to ensure the best outcome of circumcision.

5. When is the best time to perform a circumcision?

The medical literature provides no firm answer to this question. The younger the baby, the easier it is to perform a circumcision as a simple procedure with local anesthesia. The older the baby, the larger the penis and the more aware the baby will be of his surroundings. Both these factors will make the procedure more difficult.

Most clinicians would be reluctant to perform a circumcision in the office or clinic after the baby is 6 to 8 weeks old. If a family desires their son to be circumcised after that time—or a medical condition precludes earlier circumcision—the procedure is best performed by a pediatric urologist in the operating room.

Related article:

Circumcision accident: $1.3M verdict

6. What are the potential complications of circumcision?

The rate of circumcision complications is very low: 0.2%.13 That being said, the 3 most common types of complications are postoperative bleeding, infection, and damage to the penis.

Far and away the most common complication is postoperative bleeding , usually at the frenulum of the head of the penis (the 6 o’clock position). In most cases, the bleeding is light to moderate. It is controlled with direct pressure applied for several minutes, the use of processed gelatin (Gelfoam) or cellulose (Surgicel), sparing use of silver nitrate, or placement of a polyglycolic acid (Vicryl) 5-0 suture.

Infection, an unusual occurrence, is seen within 24 to 72 hours after circumcision. It is marked by swelling, redness, and a foul-smelling mucus discharge. This discharge must be differentiated from dried fibrin, which is commonly seen on the head of the penis in the days after circumcision but has no odor or association with erythema, fever, or infant fussiness. True infection should be treated, in collaboration with the child’s pediatrician, with a staphylococcal-sensitive penicillin (such as dicloxacillin).

More serious is damage to the penis, which ranges from accidental dilation of the meatus to partial amputation of the penile glans. Any such injury should immediately prompt a consultation with a pediatric urologist.

More of a nuisance than a complication is the sliding of the penile shaft’s skin up and over the glans. This is a relatively frequent occurrence after normal, successful circumcisions. Parents of an affected newborn should be instructed to gently slide the skin back until the head of the penis is completely exposed again. After several days, the skin will adhere to its proper position on the shaft.

- Just before the procedure, have a face-to-face discussion with the parents. Confirm that they want the circumcision done, explain exactly what it entails, and let them know they will receive complete aftercare instructions.

- Make sure one of the parents signs the consent form.

- Circumcise the right baby! Check the identification bracelet and confirm that the newborn’s hospital and chart numbers match.

- Prevent excessive hip movement by securing the baby's legs. The usual solution is a specially designed plastic restraint board with Velcro straps for the legs.

- Examine the infant’s penile anatomy prior to the procedure to make certain it is normal.

- For pain relief, administer enough analgesia, as either dorsal nerve block or penile ring block (the best methods). Before injection, draw the plunger of the syringe back to make certain that the needle is not in a blood vessel.

- During the procedure, make sure the entire membranous layer of foreskin covering the head of the penis is separated from the glans.

- Watch the penis for several minutes after the circumcision to make sure there is no bleeding.

7. What is a Jewish ritual circumcision?

For their newborn’s circumcision, Jewish parents may choose a bris ceremony, formally called a brit milah, in fulfillment of religious tradition. The ceremony involves a brief religious service, circumcision with the traditional Mogen clamp, a special blessing, and an official religious naming rite. The bris traditionally is performed by a mohel, a rabbi or other religious official trained in circumcision. Many parents have the bris done by a mohel who is a medical doctor. In the United States, the availability of both types of mohels varies.

8. Who should perform circumcisions—obstetricians or pediatricians?

The answer to this question depends on where you practice. In some communities or hospitals, the obstetrician performs newborn circumcision, while in other places the pediatrician does. In addition, depending on local circumstances or the specific population involved, circumcisions may be performed by a pediatric urologist, nurse practitioner, or even out of hospital by a trained religiously affiliated practitioner.

Obstetricians began doing circumcisions for 2 reasons. First, obstetricians are surgically trained whereas pediatricians are not. It was therefore thought to be more appropriate for obstetricians to do this minor surgical procedure. Second, circumcisions used to be done right in the delivery room shortly after delivery. It was thought that the crying induced by performing the circumcision helped clear the baby’s lungs and invigorated sluggish babies. Now, however, in-hospital circumcisions are usually done in the days following delivery, after the baby has had the opportunity to undergo his first physical examination to make sure that all is well and that the penile anatomy is normal.

Clinician experience, proper protocol contribute to a safe procedure

In the United States, a large percentage of male infants are circumcised. Although circumcision has known medical benefits, the procedure generally is performed for family, religious, or cultural reasons. Circumcision is a safe and straightforward procedure but has its risks and potential complications. As with most surgeries, the best outcomes are achieved by practitioners who are well trained, who perform the procedure under supervision until their experience is sufficient, and who follow correct protocol during the entire operation.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Dallas ME. The 10 most common surgeries in the US. Healthgrades website. https://www.healthgrades.com/explore/the-10-most-common-surgeries-in-the-us. Reviewed August 15, 2017. Accessed October 2, 2017.

- Laumann EO, Masi CM, Zuckerman EW. Circumcision in the United States: prevalence, prophylactic effects, and sexual practice. JAMA. 1997;277(13):1052–1057.

- American Academy of Pediatrics Task Force on Circumcision. Male circumcision. Pediatrics. 2012;130(3):e756–e785.

- American Academy of Pediatrics Task Force on Circumcision. Circumcision policy statement. Pediatrics. 2012;130(3):585–586.

- Morris BJ, Krieger JN. Does male circumcision affect sexual function, sensitivity, or satisfaction? A systematic review. J Sex Med. 2013;10(11):2644–2657.

- Howard FM, Howard CR, Fortune K, Generelli P, Zolnoun D, tenHoopen C. A randomized, placebo-controlled comparison of EMLA and dorsal penile nerve block for pain relief during neonatal circumcision. Prim Care Update Ob Gyns. 1998;5(4):196.

- Taddio A, Stevens B, Craig K, et al. Efficacy and safety of lidocaine-prilocaine cream for pain during circumcision. N Engl J Med. 1997;336(17):1197–1201.

- Lander J, Brady-Fryer B, Metcalfe JB, Nazarali S, Muttitt S. Comparison of ring block, dorsal penile nerve block, and topical anesthesia for neonatal circumcision: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 1997;278(24):2157–2162.

- Hardwick-Smith S, Mastrobattista JM, Wallace PA, Ritchey ML. Ring block for neonatal circumcision. Obstet Gynecol. 1998;91(6):930–934.

- Kaufman GE, Cimo S, Miller LW, Blass EM. An evaluation of the effects of sucrose on neonatal pain with 2 commonly used circumcision methods. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;186(3):564–568.

- Tucker SC, Cerqueiro J, Sterne GD, Bracka A. Circumcision: a refined technique and 5 year review. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2001;83(2):121–125.

- Fraser ID, Tjoe J. Circumcision using bipolar scissors can be a safe and simple operation. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2000;82(3):190–191.

- Wiswell TE, Geschke DW. Risks from circumcision during the first month of life compared with those for uncircumcised boys. Pediatrics. 1989;83(6):1011–1015.

- Dallas ME. The 10 most common surgeries in the US. Healthgrades website. https://www.healthgrades.com/explore/the-10-most-common-surgeries-in-the-us. Reviewed August 15, 2017. Accessed October 2, 2017.

- Laumann EO, Masi CM, Zuckerman EW. Circumcision in the United States: prevalence, prophylactic effects, and sexual practice. JAMA. 1997;277(13):1052–1057.

- American Academy of Pediatrics Task Force on Circumcision. Male circumcision. Pediatrics. 2012;130(3):e756–e785.

- American Academy of Pediatrics Task Force on Circumcision. Circumcision policy statement. Pediatrics. 2012;130(3):585–586.

- Morris BJ, Krieger JN. Does male circumcision affect sexual function, sensitivity, or satisfaction? A systematic review. J Sex Med. 2013;10(11):2644–2657.

- Howard FM, Howard CR, Fortune K, Generelli P, Zolnoun D, tenHoopen C. A randomized, placebo-controlled comparison of EMLA and dorsal penile nerve block for pain relief during neonatal circumcision. Prim Care Update Ob Gyns. 1998;5(4):196.

- Taddio A, Stevens B, Craig K, et al. Efficacy and safety of lidocaine-prilocaine cream for pain during circumcision. N Engl J Med. 1997;336(17):1197–1201.

- Lander J, Brady-Fryer B, Metcalfe JB, Nazarali S, Muttitt S. Comparison of ring block, dorsal penile nerve block, and topical anesthesia for neonatal circumcision: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 1997;278(24):2157–2162.

- Hardwick-Smith S, Mastrobattista JM, Wallace PA, Ritchey ML. Ring block for neonatal circumcision. Obstet Gynecol. 1998;91(6):930–934.

- Kaufman GE, Cimo S, Miller LW, Blass EM. An evaluation of the effects of sucrose on neonatal pain with 2 commonly used circumcision methods. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;186(3):564–568.

- Tucker SC, Cerqueiro J, Sterne GD, Bracka A. Circumcision: a refined technique and 5 year review. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2001;83(2):121–125.

- Fraser ID, Tjoe J. Circumcision using bipolar scissors can be a safe and simple operation. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2000;82(3):190–191.

- Wiswell TE, Geschke DW. Risks from circumcision during the first month of life compared with those for uncircumcised boys. Pediatrics. 1989;83(6):1011–1015.

External cephalic version: How to increase the chances for success

About 3% to 4% of all fetuses at term are in breech presentation. Since 2000, when Hannah and colleagues reported finding that vaginal delivery of breech-presenting babies was riskier than cesarean delivery,1 most breech-presenting neonates in the United States have been delivered abdominally2—despite subsequent questioning of some of that study’s conclusions.

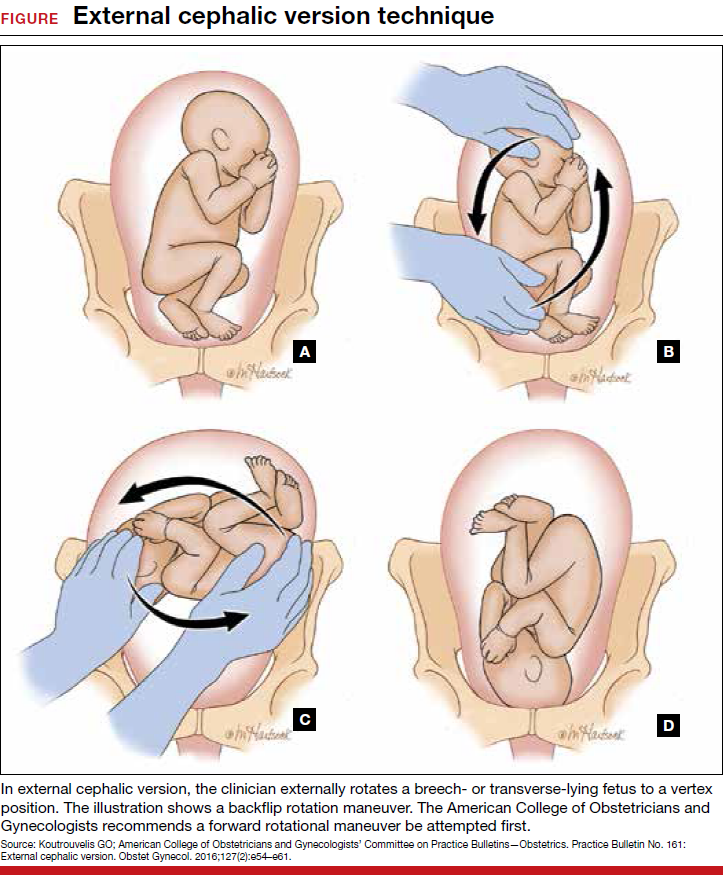

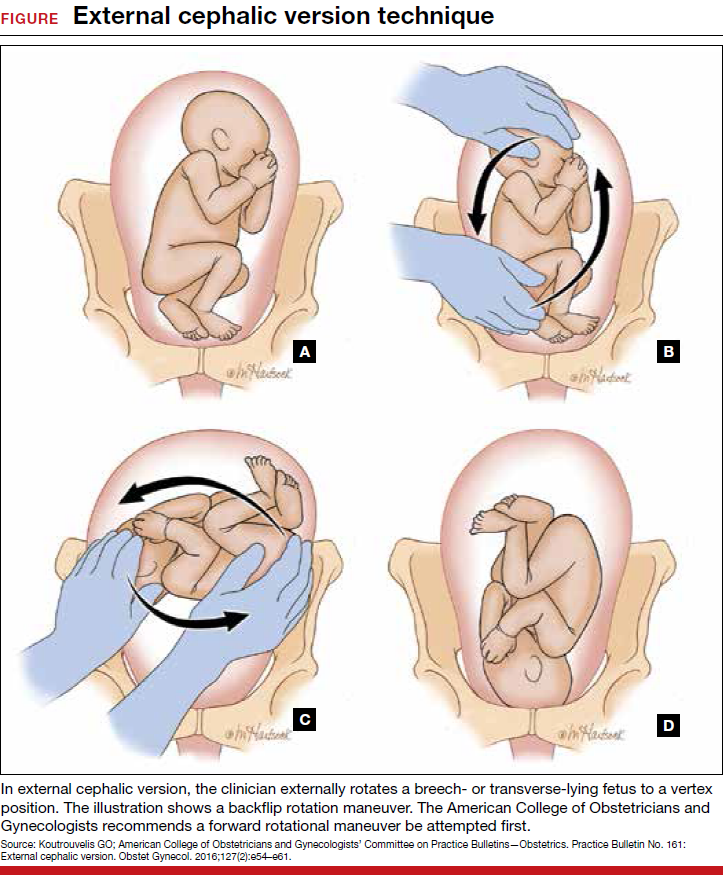

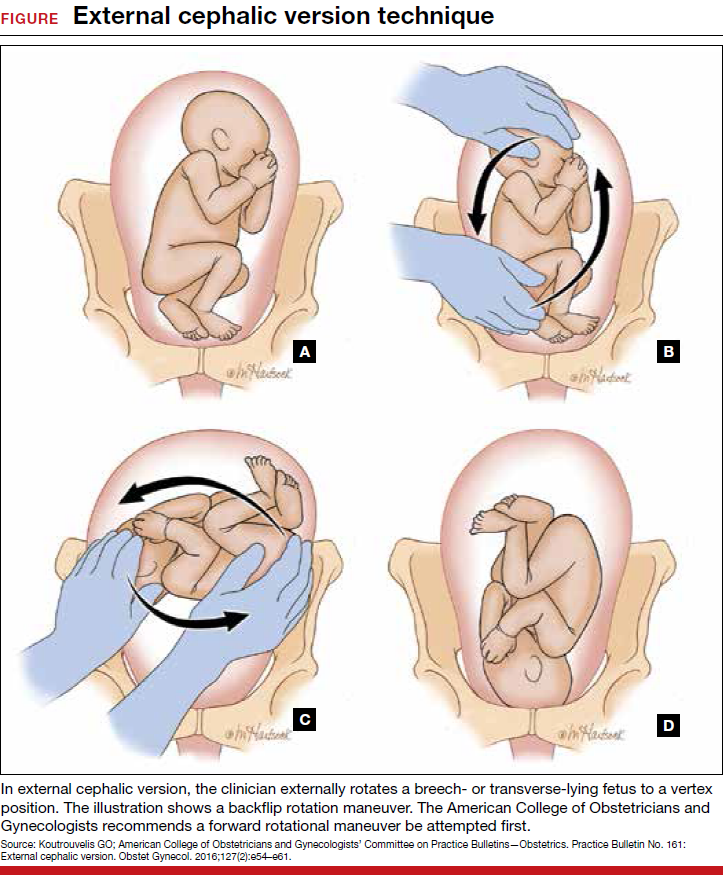

Each year in the United States, approximately 4 million babies are born, and fetal malpresentation accounts for 110,000 to 150,000 cesarean deliveries. In fact, about 15% of all cesarean deliveries in the United States are for breech presentation or transverse lie; in England the percentage is 10%.3 Fortunately, the repopularized technique of external cephalic version (ECV), in which the clinician externally rotates a breech- or transverse-lying fetus to a vertex position (FIGURE), along with the facilitating tools of tocolysis and neuraxial analgesia/anesthesia, is helping to reduce the number of breech presentations in fetuses at term and thus the number of cesarean deliveries and their sequelae—placenta accreta, prolonged recovery, and cesarean deliveries in subsequent pregnancies.

Reluctance to perform ECV is unfounded

In the United States, the practice of offering ECV to women who present with their fetus in breech presentation at term varies tremendously. It is routine at some institutions but not even offered at others.

Many ObGyns are reluctant to perform ECV. Cited reasons include the potential for injury to the fetus and mother (and related liability concerns), the ease of elective cesarean delivery, the variable success rate of ECV (35% to 86%),4 and the pain that women often have with the procedure. According to the literature, however, these concerns either are unfounded or can be mitigated with use of current techniques. Multiple studies have found that the risk of ECV to the fetus and mother is minimal, and that tocolysis and neuraxial anesthesia can facilitate the success of ECV and relieve the pain associated with the procedure.

Related article:

2017 Update on obstetrics

Indications for ECV

The indications for ECV include breech, oblique, or transverse lie presentation after 36 weeks’ gestation and the mother’s desire to avoid cesarean delivery. A clinician skilled in ECV and a facility where emergency cesarean delivery is possible are essential.

There are several instances in which ECV should not be attempted.

Contraindications include:

- concerns about fetal status, including nonreactive nonstress test, biophysical profile score <6/8, severe intrauterine growth restriction, decreased end-diastolic umbilical blood flow

- placenta previa

- multifetal gestation before delivery of first twin

- severe oligohydramnios

- severe preeclampsia

- significant fetal anomaly

- known malformation of uterus

- breech with hyperextended head or arms above shoulders, as seen on ultrasonography.

More controversial contraindications include prior uterine incision, maternal obesity (body mass index >40 kg/m2), ruptured membranes, and fetal macrosomia.

Read about timing, success rates, risk factors, alternate approaches for ECV

Optimal timing for the ECV procedure

Current practice is to wait until 36 to 37 weeks to perform ECV, as most fetuses spontaneously move into vertex presentation by 36 weeks’ gestation. This time frame has several advantages: Many unnecessary attempts at ECV are avoided; only 8% of fetuses in breech presentation after 36 weeks spontaneously change to vertex5; many fetuses revert to breech if ECV is performed too early; and prematurity generally is not an issue in the rare case that immediate delivery is required during or just after attempted ECV.

ECV during labor. Performing ECV during labor appears to pose no increased risk to mother or fetus if membranes are intact and there are no other contraindications to the procedure. Some clinicians perform ECV only during labor. The advantages are that the fetus has had every chance to move into vertex presentation on its own, the equipment used to continuously monitor the fetus during ECV is in place, and cesarean delivery and anesthesia are immediately available in the event ECV is unsuccessful.

The major disadvantage of waiting until labor is that the increased size of the fetus makes ECV more difficult. In addition, the membranes may have already ruptured, and the breech may have descended deeply into the pelvis.

Related article:

For the management of labor, patience is a virtue

Success rates in breech-to-vertex conversions

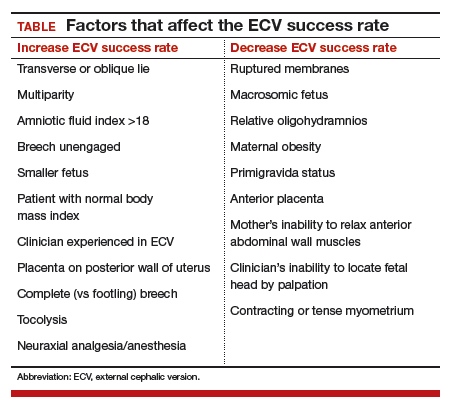

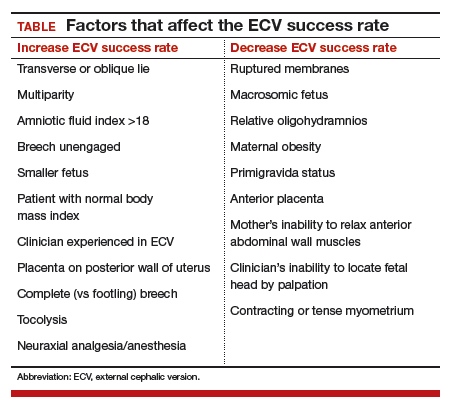

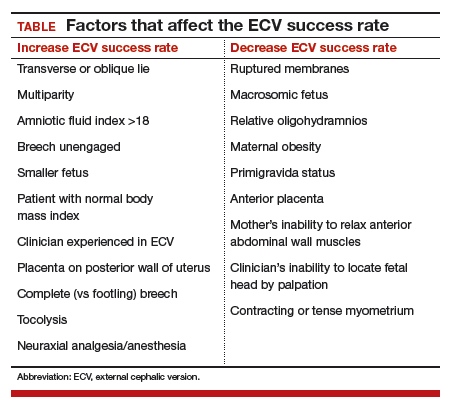

In 2016, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) reported an average ECV success rate of 58% (range, 16% to 100%).6 ACOG noted that, with transverse lie, the success rate was significantly higher. Other studies have found a wide range of rates: 58% in 1,308 patients in a Cochrane review by Hofmeyr and colleagues7; 47% in a study by Beuckens and colleagues8; and 63.1% for primiparas and 82.7% for multiparas in a study by Tong Leung and colleagues.9 These rates were affected by whether ECV was performed with or without tocolysis, with or without intravenous analgesia, and with or without neuraxial analgesia/anesthesia (TABLE).

Likelihood of vaginal delivery after successful ECV

The rate of vaginal delivery after successful ECV is roughly half that of fetuses that were never in breech presentation.10 In successful ECV cases, dystocia and nonreassuring fetal heart rate patterns are the major indications for cesarean delivery. Some experts have speculated that the factors leading to near-term breech presentation—such as an unengaged presenting part or a mother’s smaller pelvis—also may be risk factors for dystocia in labor. Despite this, the rate of vaginal delivery of successfully verted babies has been reported to be as high as 80%.10

As might be expected, post-ECV vaginal deliveries are more common in multiparous than in primiparous women.

Although multiple problems may occur with ECV, generally they are rare and reversible. For instance, Grootscholten and colleagues found a stillbirth and placental abruption rate of only 0.25% in a large group of patients who underwent ECV.11 Similarly, the rate of emergency cesarean delivery was 0.35%. In addition, Hofmeyr and Kulier, in their Cochrane Data Review of 2015, found no significant differences in the Apgar scores and pH’s of babies in the ECV group compared with babies in breech presentation whose mothers did not undergo ECV.7 Results of other studies have confirmed the safety of ECV.12,13

One significant risk of ECV attempts is fetal-to-maternal blood transfer. Boucher and colleagues found that 2.4% of 1,244 women who underwent ECV had a positive Kleihauer-Betke test result, and, in one-third of the positive cases, more than 1 mL of fetal blood was found in maternal circulation.14 This risk can be minimized by administering Rho (D) immune globulin to all Rh-negative mothers after the procedure.

Even these small risks, however, should not be considered in isolation. The infrequent complications of ECV must be compared with what can occur with breech-presenting fetuses during labor or cesarean delivery: complications of breech vaginal delivery, cord prolapse, difficulties with cesarean delivery, and maternal operative complications related to present and future cesarean deliveries.

Alternative approaches to converting breech presentation of unproven efficacy

Over the years, attempts have been made to address breech presentations with measures short of ECV. There is little evidence that these measures work, or work consistently.

- Observation. After 36 weeks’ gestation, only 8% of fetuses in breech presentationspontaneously move into vertex presentation.5

- Maternal positioning. There is no good evidence that such maneuvers are effective in changing fetal presentation.15

- Moxibustion and acupuncture. Moxibustion is inhalation of smoke from burning herbal compounds. In formal studies using controls, these techniques did not consistently increase the rate of movement from breech to vertex presentation.16–18 Likewise, studies with the use of acupuncture have not shown consistent success in changing fetal presentation.19

Read about various methods to facilitate ECV success

Methods to facilitate ECV success

Two techniques that can facilitate ECV success are tocolysis, which relaxes the uterus, and neuraxial analgesia/anesthesia, which relaxes anterior abdominal wall muscles and reduces or relieves ECV-associated pain.

Tocolysis

In tocolysis, a medication is administered to reduce myometrial activity and to relax the uterine muscle so that it stretches more easily around the fetus during repositioning. Tocolytic medications originally were studied for their use in decreasing myometrial tone during preterm labor.

Tocolysis clearly is effective in increasing ECV success rates. Reviewing the results of 4 randomized trials, Cluver showed a 1.38 risk ratio for successful ECV when terbutaline was used versus when there was no tocolysis. The risk ratio for cesarean delivery was 0.82.20 Fernandez, in a study of 103 women divided into terbutaline versus placebo groups, had a 52% success rate for ECV with the terbutaline group versus only a 27% success rate with the placebo group.21

Tocolytic medications include terbutaline, nifedipine, and nitroglycerin.

Tocolysis most often involves the use of β2-adrenergic receptor agonists, particularly terbutaline (despite the boxed safety warning in its prescribing information). A 0.25-mg dose of terbutaline is given subcutaneously 15 to 30 minutes before ECV. Clinicians have successfully used β2-adrenergic receptor agonists in the treatment of patients in preterm labor, and there are more data on this class of medications than on other agents used to facilitate ECV.

Although nifedipine is as effective as terbutaline in the temporary treatment of preterm uterine contractions, several studies have found this calcium channel blocker less effective than terbutaline in facilitating ECV.22,23

The uterus-relaxing effect of nitroglycerin was once thought to make this medication appropriate for facilitating ECV, but multiple studies have found success rates unimproved. In some cases, the drug performed more poorly than placebo.24 Moreover, nitroglycerin is associated with a fairly high rate of adverse effects, such as headaches and blood pressure changes.

Neuraxial analgesia/anesthesia

Over the past 2 decades, there has been a resurgence in the use of neuraxial analgesia/anesthesia in ECV. This technique is more effective than others in improving ECV success rates, it reduces maternal discomfort, and it is very safe. Specifically, it relaxes the maternal abdominal wall muscles and thereby facilitates ECV. Another benefit is that the anesthesia is in place and available for use should emergency cesarean delivery be needed during or after attempted ECV. Neuraxial anesthesia, which includes spinal, epidural, and combined spinal-epidural techniques, is almost always used with tocolysis.

The major complications of neuraxial analgesia/anesthesia are maternal hypotension and fetal bradycardia. Each is dose related and usually transient.

In the past, there was concern that using regional anesthesia to control pain would reduce a patient’s natural warning symptoms and result in a clinician applying excessive force, thus increasing the chances of fetal and maternal injury and even fetal death. However, multiple studies have found that ECV complication rates are not increased with use of neuraxial methods.

Higher doses of neuraxial anesthesia produce higher ECV success rates. This dose-dependent relationship is almost surely attributable to the fact that, although lower dose neuraxial analgesia can relieve the pain associated with ECV, an anesthetic dose is needed to relax the abdominal wall muscles and facilitate fetus repositioning.

The literature is clear: ECV success rates are significantly increased with the use of neuraxial techniques, with anesthesia having higher success rates than analgesia. Reviewing the results of 6 controlled trials in which a total of 508 patients underwent ECV with tocolysis, Goetzinger and colleagues found that the chance of ECV success was almost 60% higher in the 253 patients who received regional anesthesia than in the 255 patients who received intravenous or no analgesia.25 Moreover, only 48.4% of the regional anesthesia patients as compared with 59.3% of patients who did not have regional anesthesia underwent cesarean delivery, roughly a 20% decrease. Pain scores were consistently lower in the regional anesthesia group. Multiple other studies have reported similar results.

Although the use of neuraxial anesthesia increases the ECV success rate, and decreases the cesarean delivery rate for breech presentation by 5% to 15%,25 some groups of obstetrics professionals, noting that the decreased cesarean delivery rate does not meet the formal criterion for statistical significance, have expressed reservations about recommending regional anesthesia for ECV. Thus, despite the positive results obtained with neuraxial anesthesia, neither the literature nor authoritative professional organizations definitively recommend the use of neuraxial anesthesia in facilitating ECV.

This lack of official recommendation, however, overlooks an important point: While the cesarean delivery percentage decrease that occurs with the use of neuraxial anesthesia may not be statistically significant, the promise of a pain-free procedure will encourage more women to undergo ECV. If the procedure population increases, then the average ECV success rate of roughly 60%6 applies to a larger base of patients, reducing the total number of cesarean deliveries for breech presentation. As only a small percentage of the 110,000 to 150,000 women with breech presentation at 36 weeks currently elects to undergo ECV, any increase in the number of women who proceed with attempts at fetal repositioning once procedural pain is no longer an issue will accordingly reduce the number of cesarean deliveries for the indication of malpresentation.

Related article:

Nitrous oxide for labor pain

Overarching goal: Reduce cesarean delivery rate and associated risks

In the United States, increasing the use of ECV in cases of breech-presenting fetuses would reduce the cesarean delivery rate by about 10%, thereby reducing recovery time for cesarean deliveries, minimizing the risks associated with these deliveries (current and future), and providing the health care system with a major cost savings.

Tocolysis and the use of neuraxial anesthesia each increases the ECV success rate and each is remarkably safe within the context of a well-defined protocol. Reducing the pain associated with ECV by administering neuraxial anesthesia will increase the number of women electing to undergo the procedure and ultimately will reduce the number of cesarean deliveries performed for the indication of breech presentation.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Hannah ME, Hannah WJ, Hewson SA, Hodnett ED, Saigal S, Willan AR. Planned cesarean section versus planned vaginal birth for breech presentation at term: a randomised multicentre trial. Term Breech Trial Collaborative Group. Lancet. 2000;356(9239):1375–1383.

- Weiniger CF, Lyell DJ, Tsen LC, et al. Maternal outcomes of term breech presentation delivery: impact of successful external cephalic version in a nationwide sample of delivery admissions in the United States. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2016;16(1):150.

- Eller DP, Van Dorsten JP. Breech presentation. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol.1993;5(5)664–668.

- Cunningham FG, Leveno KJ, Bloom SL, et al. Williams Obstetrics. 24th ed. New York, NY: McGraw Hill; 2014:570.

- Westgren M, Edvall H, Nordstrom L, Svalenius E, Ranstam J. Spontaneous cephalic version of breech presentation in the last trimester. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1985;92(1):19–22.

- External cephalic version. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 161. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Washington, DC: ACOG; 2016.

- Hofmeyr GJ, Kulier R, West HM. External cephalic version for breech presentation at term. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;(4):CD000083.

- Beuckens A, Rijnders M, Verburgt-Doeleman GH, Rijninks-van Driel GC, Thorpe J, Hutton EK. An observational study of the success and complications of 2546 external cephalic versions in low-risk pregnant women performed by trained midwives. BJOG. 2016;123(3):415–423.

- Tong Leung VK, Suen SS, Singh Sahota D, Lau TK, Yeung Leung T. External cephalic version does not increase the risk of intra-uterine death: a 17-year experience and literature review. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2012;25(9):1774–1778.

- de Hundt M, Velzel J, de Groot CJ, Mol BW, Kok M. Mode of delivery after successful external cephalic version: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123(6):1327–1334.

- Grootscholten K, Kok M, Oei SG, Mol BW, van der Post JA. External cephalic version–related risks: a meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112(5):1143–1151.

- Collaris RJ, Oei SG. External cephalic version: a safe procedure? A systematic review of version-related risk. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2004;83(6):511–518.

- Khaw KS, Lee SW, Ngan Kee WD, et al. Randomized trial of anesthetic interventions in external cephalic version for breech presentation. Br J Anaesth. 2015;114(6):944–950.

- Boucher M, Marquette GP, Varin J, Champagne J, Bujold E. Fetomaternal hemorrhage during external cephalic version. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112(1):79–84.

- Hofmeyr GJ, Kulier R. Cephalic version by postural management for breech presentation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;(10):CD00051.

- Coulon C, Poleszczuk M, Paty-Montaigne MH, et al. Version of breech fetuses by moxibustion with acupuncture: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;124(1):32–39.

- Bue L, Lauszus FF. Moxibustion did not have an effect in a randomised clinical trial for version of breech position. Dan Med J. 2016;63(2):pii:A5199.

- Coyle ME, Smith CA, Peat B. Cephalic version by moxibustion for breech presentation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;(5):CD003928.

- Sananes N, Roth GE, Aissi GA, et al. Acupuncture version of breech presentation: a randomized sham-controlled single-blinded trial. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2016;204:24–30.

- Cluver C, Gyte GM, Sinclair M, Dowswell T, Hofmeyr G. Interventions for helping to turn breech babies to head first presentation when using external cephalic version. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;(2):CD000184.

- Fernandez CO, Bloom SL, Smulian JC, Ananth CV, Wendel GD Jr. A randomized placebo-controlled evaluation of terbutaline for external cephalic version. Obstet Gynecol. 1997;90(5):775–779.

- Mohamed Ismail NA, Ibrahim M, Mohd Naim N, Mahdy ZA, Jamil MA, Mohd Razi ZR. Nifedipine versus terbutaline for tocolysis in external cephalic version. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2008;102(3):263–266.

- Kok M, Bais J, van Lith J, et al. Nifedipine as a uterine relaxant for external cephalic version: a meta-analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112(2 pt 1):271–276.

- Bujold E, Boucher M, Rinfred D, Berman S, Ferreira E, Marquette GP. Sublingual nitroglycerin versus placebo as a tocolytic for external cephalic version: a randomized controlled trial in parous women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;189(4):1070–1073.

- Goetzinger KR, Harper LM, Tuuli MG, Macones GA, Colditz GA. Effect of regional anesthesia on the success of external cephalic version: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118(5):1137–1144.

About 3% to 4% of all fetuses at term are in breech presentation. Since 2000, when Hannah and colleagues reported finding that vaginal delivery of breech-presenting babies was riskier than cesarean delivery,1 most breech-presenting neonates in the United States have been delivered abdominally2—despite subsequent questioning of some of that study’s conclusions.

Each year in the United States, approximately 4 million babies are born, and fetal malpresentation accounts for 110,000 to 150,000 cesarean deliveries. In fact, about 15% of all cesarean deliveries in the United States are for breech presentation or transverse lie; in England the percentage is 10%.3 Fortunately, the repopularized technique of external cephalic version (ECV), in which the clinician externally rotates a breech- or transverse-lying fetus to a vertex position (FIGURE), along with the facilitating tools of tocolysis and neuraxial analgesia/anesthesia, is helping to reduce the number of breech presentations in fetuses at term and thus the number of cesarean deliveries and their sequelae—placenta accreta, prolonged recovery, and cesarean deliveries in subsequent pregnancies.

Reluctance to perform ECV is unfounded

In the United States, the practice of offering ECV to women who present with their fetus in breech presentation at term varies tremendously. It is routine at some institutions but not even offered at others.

Many ObGyns are reluctant to perform ECV. Cited reasons include the potential for injury to the fetus and mother (and related liability concerns), the ease of elective cesarean delivery, the variable success rate of ECV (35% to 86%),4 and the pain that women often have with the procedure. According to the literature, however, these concerns either are unfounded or can be mitigated with use of current techniques. Multiple studies have found that the risk of ECV to the fetus and mother is minimal, and that tocolysis and neuraxial anesthesia can facilitate the success of ECV and relieve the pain associated with the procedure.

Related article:

2017 Update on obstetrics

Indications for ECV

The indications for ECV include breech, oblique, or transverse lie presentation after 36 weeks’ gestation and the mother’s desire to avoid cesarean delivery. A clinician skilled in ECV and a facility where emergency cesarean delivery is possible are essential.

There are several instances in which ECV should not be attempted.

Contraindications include:

- concerns about fetal status, including nonreactive nonstress test, biophysical profile score <6/8, severe intrauterine growth restriction, decreased end-diastolic umbilical blood flow

- placenta previa

- multifetal gestation before delivery of first twin

- severe oligohydramnios

- severe preeclampsia

- significant fetal anomaly

- known malformation of uterus

- breech with hyperextended head or arms above shoulders, as seen on ultrasonography.

More controversial contraindications include prior uterine incision, maternal obesity (body mass index >40 kg/m2), ruptured membranes, and fetal macrosomia.

Read about timing, success rates, risk factors, alternate approaches for ECV

Optimal timing for the ECV procedure

Current practice is to wait until 36 to 37 weeks to perform ECV, as most fetuses spontaneously move into vertex presentation by 36 weeks’ gestation. This time frame has several advantages: Many unnecessary attempts at ECV are avoided; only 8% of fetuses in breech presentation after 36 weeks spontaneously change to vertex5; many fetuses revert to breech if ECV is performed too early; and prematurity generally is not an issue in the rare case that immediate delivery is required during or just after attempted ECV.

ECV during labor. Performing ECV during labor appears to pose no increased risk to mother or fetus if membranes are intact and there are no other contraindications to the procedure. Some clinicians perform ECV only during labor. The advantages are that the fetus has had every chance to move into vertex presentation on its own, the equipment used to continuously monitor the fetus during ECV is in place, and cesarean delivery and anesthesia are immediately available in the event ECV is unsuccessful.

The major disadvantage of waiting until labor is that the increased size of the fetus makes ECV more difficult. In addition, the membranes may have already ruptured, and the breech may have descended deeply into the pelvis.

Related article:

For the management of labor, patience is a virtue

Success rates in breech-to-vertex conversions

In 2016, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) reported an average ECV success rate of 58% (range, 16% to 100%).6 ACOG noted that, with transverse lie, the success rate was significantly higher. Other studies have found a wide range of rates: 58% in 1,308 patients in a Cochrane review by Hofmeyr and colleagues7; 47% in a study by Beuckens and colleagues8; and 63.1% for primiparas and 82.7% for multiparas in a study by Tong Leung and colleagues.9 These rates were affected by whether ECV was performed with or without tocolysis, with or without intravenous analgesia, and with or without neuraxial analgesia/anesthesia (TABLE).

Likelihood of vaginal delivery after successful ECV

The rate of vaginal delivery after successful ECV is roughly half that of fetuses that were never in breech presentation.10 In successful ECV cases, dystocia and nonreassuring fetal heart rate patterns are the major indications for cesarean delivery. Some experts have speculated that the factors leading to near-term breech presentation—such as an unengaged presenting part or a mother’s smaller pelvis—also may be risk factors for dystocia in labor. Despite this, the rate of vaginal delivery of successfully verted babies has been reported to be as high as 80%.10

As might be expected, post-ECV vaginal deliveries are more common in multiparous than in primiparous women.

Although multiple problems may occur with ECV, generally they are rare and reversible. For instance, Grootscholten and colleagues found a stillbirth and placental abruption rate of only 0.25% in a large group of patients who underwent ECV.11 Similarly, the rate of emergency cesarean delivery was 0.35%. In addition, Hofmeyr and Kulier, in their Cochrane Data Review of 2015, found no significant differences in the Apgar scores and pH’s of babies in the ECV group compared with babies in breech presentation whose mothers did not undergo ECV.7 Results of other studies have confirmed the safety of ECV.12,13

One significant risk of ECV attempts is fetal-to-maternal blood transfer. Boucher and colleagues found that 2.4% of 1,244 women who underwent ECV had a positive Kleihauer-Betke test result, and, in one-third of the positive cases, more than 1 mL of fetal blood was found in maternal circulation.14 This risk can be minimized by administering Rho (D) immune globulin to all Rh-negative mothers after the procedure.

Even these small risks, however, should not be considered in isolation. The infrequent complications of ECV must be compared with what can occur with breech-presenting fetuses during labor or cesarean delivery: complications of breech vaginal delivery, cord prolapse, difficulties with cesarean delivery, and maternal operative complications related to present and future cesarean deliveries.

Alternative approaches to converting breech presentation of unproven efficacy

Over the years, attempts have been made to address breech presentations with measures short of ECV. There is little evidence that these measures work, or work consistently.

- Observation. After 36 weeks’ gestation, only 8% of fetuses in breech presentationspontaneously move into vertex presentation.5

- Maternal positioning. There is no good evidence that such maneuvers are effective in changing fetal presentation.15

- Moxibustion and acupuncture. Moxibustion is inhalation of smoke from burning herbal compounds. In formal studies using controls, these techniques did not consistently increase the rate of movement from breech to vertex presentation.16–18 Likewise, studies with the use of acupuncture have not shown consistent success in changing fetal presentation.19

Read about various methods to facilitate ECV success

Methods to facilitate ECV success

Two techniques that can facilitate ECV success are tocolysis, which relaxes the uterus, and neuraxial analgesia/anesthesia, which relaxes anterior abdominal wall muscles and reduces or relieves ECV-associated pain.

Tocolysis