User login

Healthy infant with a blistering rash

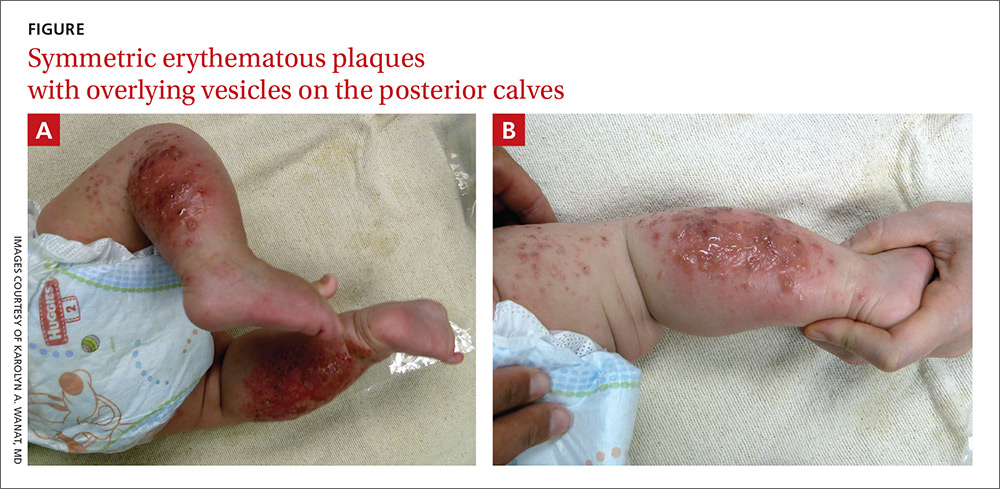

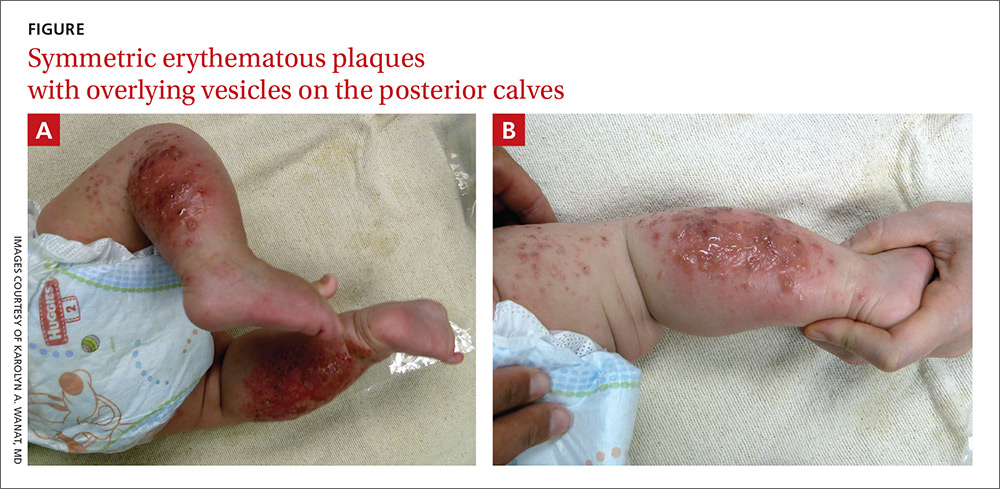

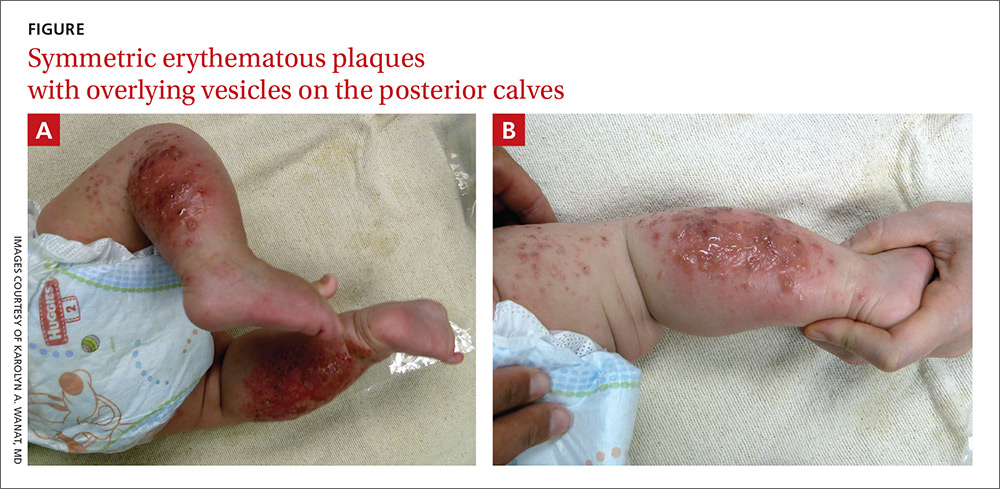

A 4-month-old girl was brought to our clinic with a 4-week history of blisters on her arms and legs. The eruption started on her right posterior and lateral calf and then appeared on her left calf and bilateral elbows. Other than the blisters, the girl appeared well and was eating and growing normally. Her parents said she had not been in contact with anyone with a similar rash or itching. They also denied recent outdoor activities, camping trips, or environmental exposures.

The child had been previously treated with topical and oral steroids and oral antibiotics by a pediatrician, but the rash barely improved. On physical examination, she was afebrile with well-demarcated erythematous papules and plaques with bullae, and erosions with honey-colored crusts. The rash was distributed symmetrically on the bilateral posterior and lateral lower legs and lateral upper arms (FIGURE).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Allergic contact dermatitis from a car seat

The appearance and distribution of the rash on the infant’s posterior and lateral lower legs and lateral upper arms prompted us to conclude that this was a case of allergic contact dermatitis from a car seat, along with secondary impetiginization.

The incidence of car seat contact dermatitis is unknown, although it is suspected to be both under-recognized and under-reported. In fact, the number of cases may be on the rise,1 given the increasing number of synthetic liners now being used in car seats, high chairs, and other infant support products.

More common in summer months. Car seat dermatitis is commonly reported in warmer months, when an infant’s skin is more likely to be in direct contact with the car seat and sweating is increased.1 In the acute setting, clinical morphology usually takes the form of inflamed papules or vesicles, while in chronic presentations, lichenified eczematous plaques may be seen. Distribution is typically symmetric and involves areas in direct contact with the car seat, such as the elbows, upper lateral or posterior thighs, lower lateral legs, and sometimes, the occipital scalp.1 The presence of a secondary infection or autoeczematization can complicate the clinical presentation.

Which car seat materials are to blame? Previous reports have described the shiny, nylon-like material overlying the car seat cushion as the cause of the contact allergy, but no specific allergens have yet been identified.1 Attempts at identifying specific allergens in car seat liners have been thwarted by the proprietary nature of manufacturers’ formulas and the unwillingness of companies to divulge the chemicals used in the manufacture of their car seats. Potential allergens include bromine, chlorine, and flame-retardants.1 These allergens differ from the usual contact allergens in children and adolescents, which include nickel sulfate, cobalt chloride, potassium dichromate, fragrance mix, thimerosal, neomycin sulfate, and para-tertiary-butylphenol formaldehyde resin.2

Differential includes other conditions with blisters, plaques

The differential diagnosis includes eczema herpeticum, bullous impetigo, and psoriasis.

Infants with eczema herpeticum usually have eczematous plaques in locations such as the cheeks, neck, antecubital fossa, popliteal fossa, and ankles, with numerous “punched-out” shallow erosions. Children with extensive eczema herpeticum can be systemically ill.

Bullous impetigo is seen as flaccid bullae in infants, which can easily rupture and leave behind superficial erosions. These blisters tend to appear on normal skin. (This is quite different from the thick, erythematous plaques seen in contact dermatitis.) In patients with superficial erosions, a polymerase chain reaction test for the herpes virus and a bacterial culture should be obtained.

Psoriasis often presents with well-demarcated erythematous plaques with overlying silver scale. Although it can be symmetric on extensor surfaces, the weeping vesicles with acute onset that were seen in this case would be unusual.

Look for a pattern. The well-demarcated symmetric plaques corresponding directly to areas in contact with the car seat should be a strong clue for contact dermatitis. While patch testing for relevant chemicals is often indicated in patients for whom there is a clinical suspicion of a contact allergy,3,4 we did not perform such testing because the specific chemicals involved in car seat manufacturing are unknown.

Topical steroids and avoidance of the allergen help resolve the rash

The mainstay of treatment for allergic contact dermatitis is avoiding the contact allergen. In car seat contact dermatitis, parents should be counseled to avoid contact between the child’s bare skin and the car seat liner. Given that the precise allergen is unknown, it is impossible to know if a new car seat would contain the same material. Instead, we recommend covering the car seat with a cotton blanket to avoid irritation/allergens.

Depending on the extent of the rash, the patient should be treated with a mid- or high-potency topical steroid until the erythema and blistering resolve.5-8 A 3-week prednisone taper can also be considered for severe cases. For patients who have >25% of their body surface involved, oral steroids are recommended.6 Any secondary infection should be treated with topical and oral antibiotics, as appropriate.

Our patient. Due to the extent and severity of the eruption, we put the patient on a 3-week oral prednisone taper and advised the parents to apply clobetasol 0.05% ointment to the affected areas 2 times a day. We also prescribed a 7-day course of cephalexin 50 mg/kg divided in 3 doses a day and topical mupirocin ointment (to be applied 2 times a day) for the secondary impetiginization.

We advised the parents to use a cotton blanket over the baby’s car seat to prevent further outbreaks. The eruption resolved within 2 months.

CORRESPONDENCE

Karolyn A. Wanat, MD, Department of Dermatology, University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics, 200 Hawkins Drive, 40000 PFP, Iowa City, IA 52242; karolyn-wanat@uiowa.edu.

1. Ghali FE. “Car seat dermatitis”: a newly described form of contact dermatitis. Pediatr Dermatol. 2011;28:321-326.

2. Mortz CG, Andersen KE. Allergic contact dermatitis in children and adolescents. Contact Dermatitis. 1999;41:121-130.

3. van der Valk PG, Devos SA, Coenraads PJ. Evidence-based diagnosis in patch testing. Contact Dermatitis. 2003;48:121-125.

4. Krob HA, Fleischer AB Jr, D’Agostino R Jr, et al. Prevalence and relevance of contact dermatitis allergens: a meta-analysis of 15 years of published T.R.U.E. test data. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51:349-353.

5. Cohen DE, Heidary N. Treatment of irritant and allergic contact dermatitis. Dermatol Ther. 2004;17:334-340.

6. Belsito DV. The diagnostic evaluation, treatment, and prevention of allergic contact dermatitis in the new millennium. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2000;105:409-420.

7. Hachem JP, De Paepe K, Vanpée E, et al. Efficacy of topical corticosteroids in nickel-induced contact allergy. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2002;27:47-50.

8. Saary J, Qureshi R, Palda V, et al. A systematic review of contact dermatitis treatment and prevention. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:845.

A 4-month-old girl was brought to our clinic with a 4-week history of blisters on her arms and legs. The eruption started on her right posterior and lateral calf and then appeared on her left calf and bilateral elbows. Other than the blisters, the girl appeared well and was eating and growing normally. Her parents said she had not been in contact with anyone with a similar rash or itching. They also denied recent outdoor activities, camping trips, or environmental exposures.

The child had been previously treated with topical and oral steroids and oral antibiotics by a pediatrician, but the rash barely improved. On physical examination, she was afebrile with well-demarcated erythematous papules and plaques with bullae, and erosions with honey-colored crusts. The rash was distributed symmetrically on the bilateral posterior and lateral lower legs and lateral upper arms (FIGURE).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Allergic contact dermatitis from a car seat

The appearance and distribution of the rash on the infant’s posterior and lateral lower legs and lateral upper arms prompted us to conclude that this was a case of allergic contact dermatitis from a car seat, along with secondary impetiginization.

The incidence of car seat contact dermatitis is unknown, although it is suspected to be both under-recognized and under-reported. In fact, the number of cases may be on the rise,1 given the increasing number of synthetic liners now being used in car seats, high chairs, and other infant support products.

More common in summer months. Car seat dermatitis is commonly reported in warmer months, when an infant’s skin is more likely to be in direct contact with the car seat and sweating is increased.1 In the acute setting, clinical morphology usually takes the form of inflamed papules or vesicles, while in chronic presentations, lichenified eczematous plaques may be seen. Distribution is typically symmetric and involves areas in direct contact with the car seat, such as the elbows, upper lateral or posterior thighs, lower lateral legs, and sometimes, the occipital scalp.1 The presence of a secondary infection or autoeczematization can complicate the clinical presentation.

Which car seat materials are to blame? Previous reports have described the shiny, nylon-like material overlying the car seat cushion as the cause of the contact allergy, but no specific allergens have yet been identified.1 Attempts at identifying specific allergens in car seat liners have been thwarted by the proprietary nature of manufacturers’ formulas and the unwillingness of companies to divulge the chemicals used in the manufacture of their car seats. Potential allergens include bromine, chlorine, and flame-retardants.1 These allergens differ from the usual contact allergens in children and adolescents, which include nickel sulfate, cobalt chloride, potassium dichromate, fragrance mix, thimerosal, neomycin sulfate, and para-tertiary-butylphenol formaldehyde resin.2

Differential includes other conditions with blisters, plaques

The differential diagnosis includes eczema herpeticum, bullous impetigo, and psoriasis.

Infants with eczema herpeticum usually have eczematous plaques in locations such as the cheeks, neck, antecubital fossa, popliteal fossa, and ankles, with numerous “punched-out” shallow erosions. Children with extensive eczema herpeticum can be systemically ill.

Bullous impetigo is seen as flaccid bullae in infants, which can easily rupture and leave behind superficial erosions. These blisters tend to appear on normal skin. (This is quite different from the thick, erythematous plaques seen in contact dermatitis.) In patients with superficial erosions, a polymerase chain reaction test for the herpes virus and a bacterial culture should be obtained.

Psoriasis often presents with well-demarcated erythematous plaques with overlying silver scale. Although it can be symmetric on extensor surfaces, the weeping vesicles with acute onset that were seen in this case would be unusual.

Look for a pattern. The well-demarcated symmetric plaques corresponding directly to areas in contact with the car seat should be a strong clue for contact dermatitis. While patch testing for relevant chemicals is often indicated in patients for whom there is a clinical suspicion of a contact allergy,3,4 we did not perform such testing because the specific chemicals involved in car seat manufacturing are unknown.

Topical steroids and avoidance of the allergen help resolve the rash

The mainstay of treatment for allergic contact dermatitis is avoiding the contact allergen. In car seat contact dermatitis, parents should be counseled to avoid contact between the child’s bare skin and the car seat liner. Given that the precise allergen is unknown, it is impossible to know if a new car seat would contain the same material. Instead, we recommend covering the car seat with a cotton blanket to avoid irritation/allergens.

Depending on the extent of the rash, the patient should be treated with a mid- or high-potency topical steroid until the erythema and blistering resolve.5-8 A 3-week prednisone taper can also be considered for severe cases. For patients who have >25% of their body surface involved, oral steroids are recommended.6 Any secondary infection should be treated with topical and oral antibiotics, as appropriate.

Our patient. Due to the extent and severity of the eruption, we put the patient on a 3-week oral prednisone taper and advised the parents to apply clobetasol 0.05% ointment to the affected areas 2 times a day. We also prescribed a 7-day course of cephalexin 50 mg/kg divided in 3 doses a day and topical mupirocin ointment (to be applied 2 times a day) for the secondary impetiginization.

We advised the parents to use a cotton blanket over the baby’s car seat to prevent further outbreaks. The eruption resolved within 2 months.

CORRESPONDENCE

Karolyn A. Wanat, MD, Department of Dermatology, University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics, 200 Hawkins Drive, 40000 PFP, Iowa City, IA 52242; karolyn-wanat@uiowa.edu.

A 4-month-old girl was brought to our clinic with a 4-week history of blisters on her arms and legs. The eruption started on her right posterior and lateral calf and then appeared on her left calf and bilateral elbows. Other than the blisters, the girl appeared well and was eating and growing normally. Her parents said she had not been in contact with anyone with a similar rash or itching. They also denied recent outdoor activities, camping trips, or environmental exposures.

The child had been previously treated with topical and oral steroids and oral antibiotics by a pediatrician, but the rash barely improved. On physical examination, she was afebrile with well-demarcated erythematous papules and plaques with bullae, and erosions with honey-colored crusts. The rash was distributed symmetrically on the bilateral posterior and lateral lower legs and lateral upper arms (FIGURE).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Allergic contact dermatitis from a car seat

The appearance and distribution of the rash on the infant’s posterior and lateral lower legs and lateral upper arms prompted us to conclude that this was a case of allergic contact dermatitis from a car seat, along with secondary impetiginization.

The incidence of car seat contact dermatitis is unknown, although it is suspected to be both under-recognized and under-reported. In fact, the number of cases may be on the rise,1 given the increasing number of synthetic liners now being used in car seats, high chairs, and other infant support products.

More common in summer months. Car seat dermatitis is commonly reported in warmer months, when an infant’s skin is more likely to be in direct contact with the car seat and sweating is increased.1 In the acute setting, clinical morphology usually takes the form of inflamed papules or vesicles, while in chronic presentations, lichenified eczematous plaques may be seen. Distribution is typically symmetric and involves areas in direct contact with the car seat, such as the elbows, upper lateral or posterior thighs, lower lateral legs, and sometimes, the occipital scalp.1 The presence of a secondary infection or autoeczematization can complicate the clinical presentation.

Which car seat materials are to blame? Previous reports have described the shiny, nylon-like material overlying the car seat cushion as the cause of the contact allergy, but no specific allergens have yet been identified.1 Attempts at identifying specific allergens in car seat liners have been thwarted by the proprietary nature of manufacturers’ formulas and the unwillingness of companies to divulge the chemicals used in the manufacture of their car seats. Potential allergens include bromine, chlorine, and flame-retardants.1 These allergens differ from the usual contact allergens in children and adolescents, which include nickel sulfate, cobalt chloride, potassium dichromate, fragrance mix, thimerosal, neomycin sulfate, and para-tertiary-butylphenol formaldehyde resin.2

Differential includes other conditions with blisters, plaques

The differential diagnosis includes eczema herpeticum, bullous impetigo, and psoriasis.

Infants with eczema herpeticum usually have eczematous plaques in locations such as the cheeks, neck, antecubital fossa, popliteal fossa, and ankles, with numerous “punched-out” shallow erosions. Children with extensive eczema herpeticum can be systemically ill.

Bullous impetigo is seen as flaccid bullae in infants, which can easily rupture and leave behind superficial erosions. These blisters tend to appear on normal skin. (This is quite different from the thick, erythematous plaques seen in contact dermatitis.) In patients with superficial erosions, a polymerase chain reaction test for the herpes virus and a bacterial culture should be obtained.

Psoriasis often presents with well-demarcated erythematous plaques with overlying silver scale. Although it can be symmetric on extensor surfaces, the weeping vesicles with acute onset that were seen in this case would be unusual.

Look for a pattern. The well-demarcated symmetric plaques corresponding directly to areas in contact with the car seat should be a strong clue for contact dermatitis. While patch testing for relevant chemicals is often indicated in patients for whom there is a clinical suspicion of a contact allergy,3,4 we did not perform such testing because the specific chemicals involved in car seat manufacturing are unknown.

Topical steroids and avoidance of the allergen help resolve the rash

The mainstay of treatment for allergic contact dermatitis is avoiding the contact allergen. In car seat contact dermatitis, parents should be counseled to avoid contact between the child’s bare skin and the car seat liner. Given that the precise allergen is unknown, it is impossible to know if a new car seat would contain the same material. Instead, we recommend covering the car seat with a cotton blanket to avoid irritation/allergens.

Depending on the extent of the rash, the patient should be treated with a mid- or high-potency topical steroid until the erythema and blistering resolve.5-8 A 3-week prednisone taper can also be considered for severe cases. For patients who have >25% of their body surface involved, oral steroids are recommended.6 Any secondary infection should be treated with topical and oral antibiotics, as appropriate.

Our patient. Due to the extent and severity of the eruption, we put the patient on a 3-week oral prednisone taper and advised the parents to apply clobetasol 0.05% ointment to the affected areas 2 times a day. We also prescribed a 7-day course of cephalexin 50 mg/kg divided in 3 doses a day and topical mupirocin ointment (to be applied 2 times a day) for the secondary impetiginization.

We advised the parents to use a cotton blanket over the baby’s car seat to prevent further outbreaks. The eruption resolved within 2 months.

CORRESPONDENCE

Karolyn A. Wanat, MD, Department of Dermatology, University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics, 200 Hawkins Drive, 40000 PFP, Iowa City, IA 52242; karolyn-wanat@uiowa.edu.

1. Ghali FE. “Car seat dermatitis”: a newly described form of contact dermatitis. Pediatr Dermatol. 2011;28:321-326.

2. Mortz CG, Andersen KE. Allergic contact dermatitis in children and adolescents. Contact Dermatitis. 1999;41:121-130.

3. van der Valk PG, Devos SA, Coenraads PJ. Evidence-based diagnosis in patch testing. Contact Dermatitis. 2003;48:121-125.

4. Krob HA, Fleischer AB Jr, D’Agostino R Jr, et al. Prevalence and relevance of contact dermatitis allergens: a meta-analysis of 15 years of published T.R.U.E. test data. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51:349-353.

5. Cohen DE, Heidary N. Treatment of irritant and allergic contact dermatitis. Dermatol Ther. 2004;17:334-340.

6. Belsito DV. The diagnostic evaluation, treatment, and prevention of allergic contact dermatitis in the new millennium. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2000;105:409-420.

7. Hachem JP, De Paepe K, Vanpée E, et al. Efficacy of topical corticosteroids in nickel-induced contact allergy. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2002;27:47-50.

8. Saary J, Qureshi R, Palda V, et al. A systematic review of contact dermatitis treatment and prevention. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:845.

1. Ghali FE. “Car seat dermatitis”: a newly described form of contact dermatitis. Pediatr Dermatol. 2011;28:321-326.

2. Mortz CG, Andersen KE. Allergic contact dermatitis in children and adolescents. Contact Dermatitis. 1999;41:121-130.

3. van der Valk PG, Devos SA, Coenraads PJ. Evidence-based diagnosis in patch testing. Contact Dermatitis. 2003;48:121-125.

4. Krob HA, Fleischer AB Jr, D’Agostino R Jr, et al. Prevalence and relevance of contact dermatitis allergens: a meta-analysis of 15 years of published T.R.U.E. test data. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51:349-353.

5. Cohen DE, Heidary N. Treatment of irritant and allergic contact dermatitis. Dermatol Ther. 2004;17:334-340.

6. Belsito DV. The diagnostic evaluation, treatment, and prevention of allergic contact dermatitis in the new millennium. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2000;105:409-420.

7. Hachem JP, De Paepe K, Vanpée E, et al. Efficacy of topical corticosteroids in nickel-induced contact allergy. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2002;27:47-50.

8. Saary J, Qureshi R, Palda V, et al. A systematic review of contact dermatitis treatment and prevention. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:845.

Perifollicular petechiae and easy bruising

A 45-year-old woman presented to our hospital with recurrent cirrhosis and sepsis secondary to a hepatic abscess from Pseudomonas aeromonas and Candida albicans. Ten years earlier, she had received a liver transplant due to sclerosing cholangitis. The patient had a history of nausea from her liver disease and malnutrition due to a diet that consisted predominantly of cereal with minimal fresh fruits and vegetables. Her family reported that she bruised easily and had worsening dry, flaky skin.

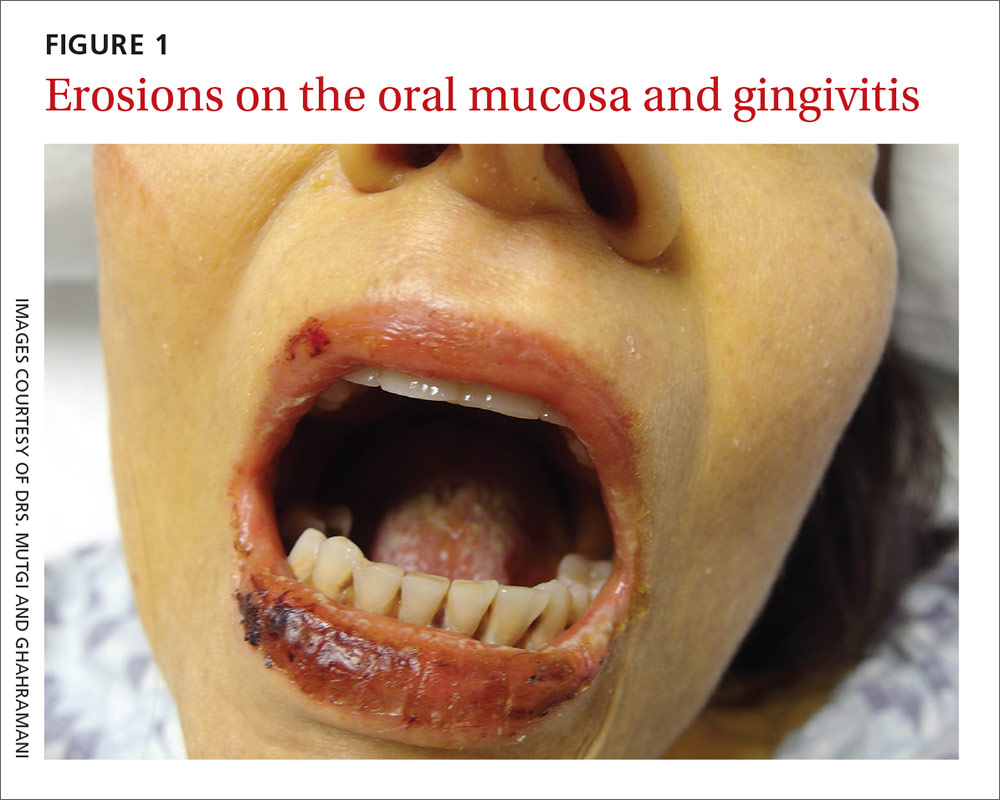

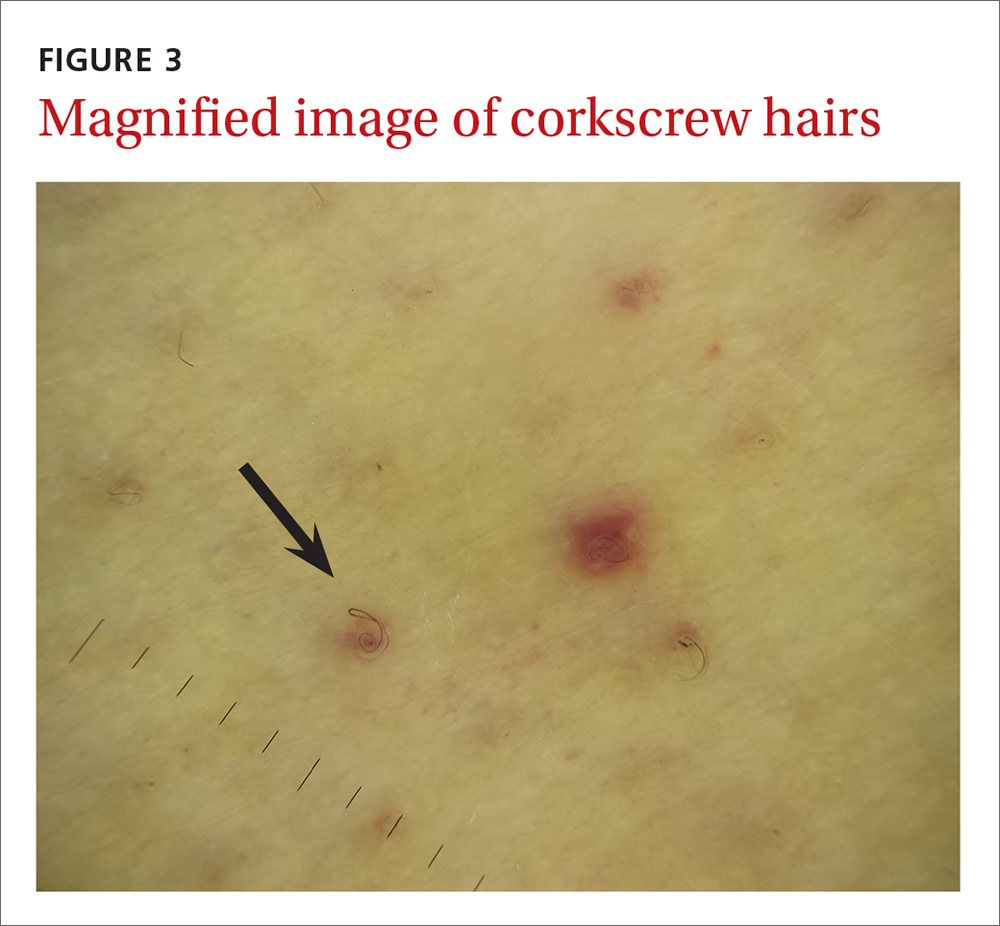

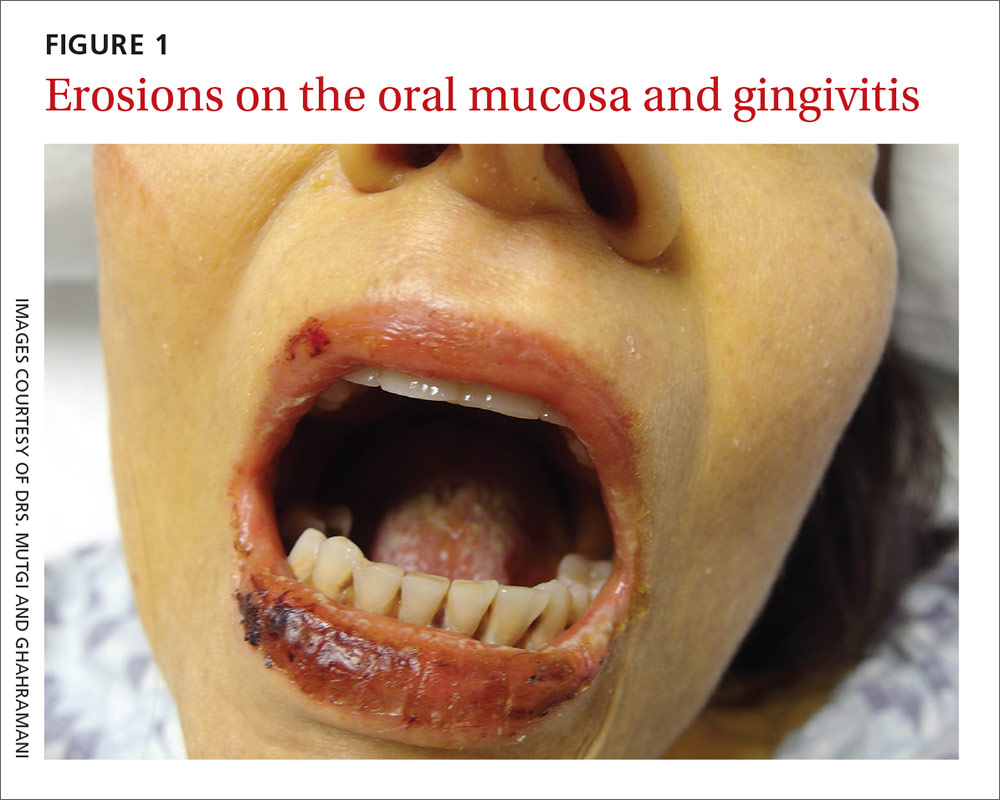

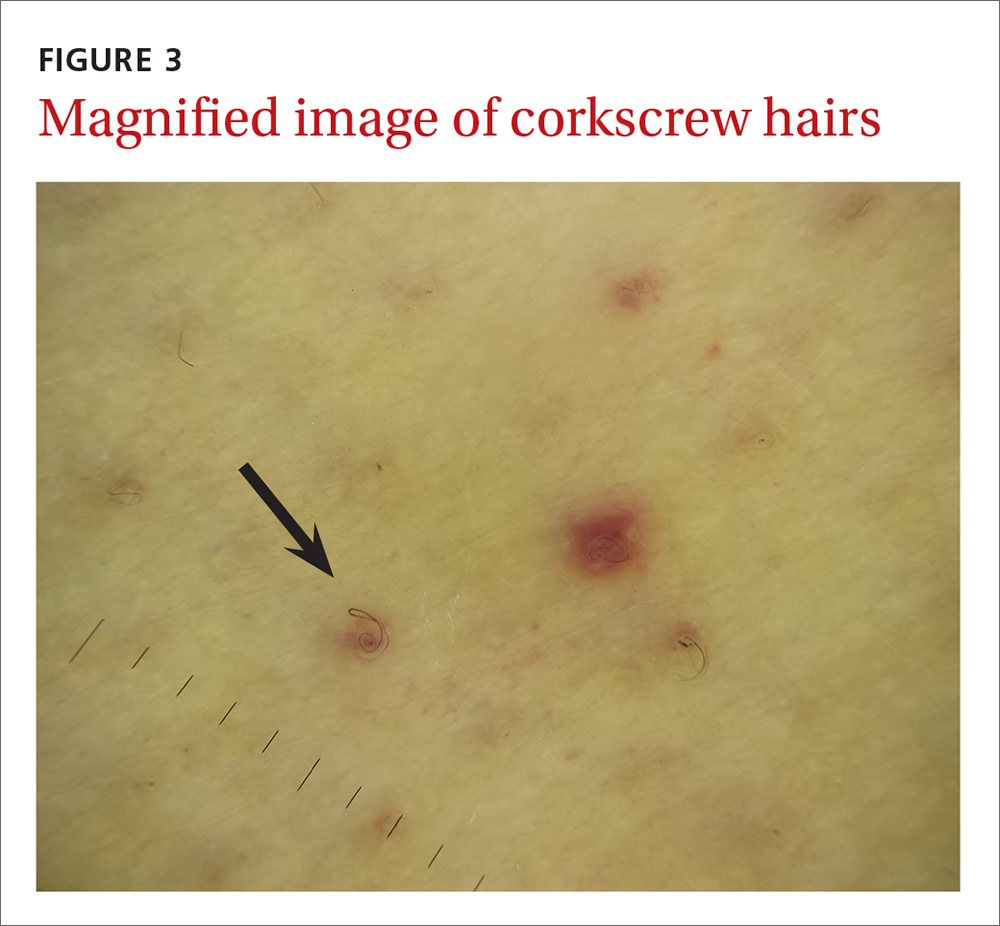

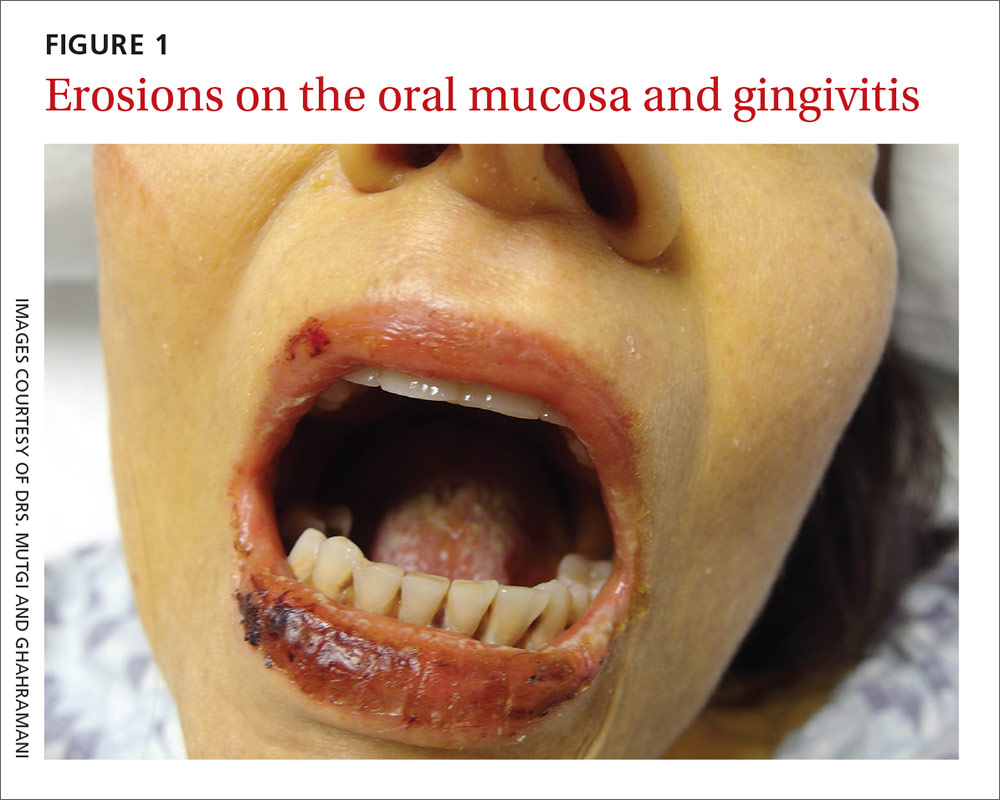

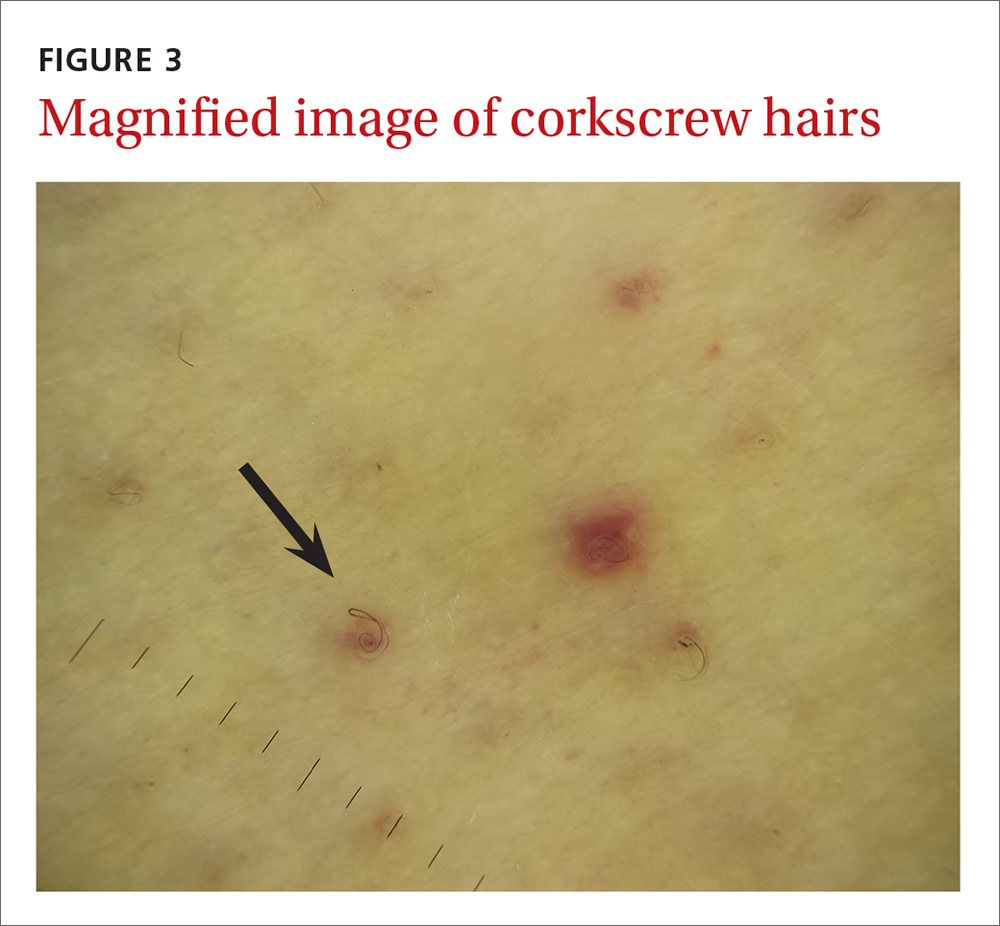

The physical examination revealed jaundice, scleral icterus, purpuric macules, superficial desquamation, gingivitis (FIGURE 1), and perifollicular hemorrhages with corkscrew hairs (FIGURES 2 and 3). The patient also had acute kidney injury, delirium, and pancytopenia. She was admitted to the hospital and was started on piperacillin-tazobactam and fluconazole for sepsis, as well as rifaximin and lactulose for hepatic encephalopathy.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Vitamin C deficiency

We diagnosed this patient with vitamin C deficiency (scurvy) based on the fact that she had perifollicular hemorrhages with corkscrew hairs, which is a pathognomonic feature of the deficiency. The diagnosis was confirmed with a blood vitamin C level of 10 mcmol/L (normal range: 11-114 mcmol/L). It’s important to note that a vitamin C level drawn after hospitalization may be falsely normal due to an improved diet during hospitalization, so a normal vitamin C level doesn’t always rule out a deficiency.

Vitamin C is absorbed from the small intestine and excreted renally. A low vitamin C level occurs in the presence of several conditions—specifically alcoholism and critical illnesses such as sepsis, trauma, major surgery, or stroke—possibly due to decreased absorption and increased oxidative stress. Vitamin C is necessary for multiple hydroxylation reactions, including hydroxylation of proline and lysine in collagen synthesis, beta-hydroxybutyric acid in carnitine synthesis, and dopamine-beta-hydroxylase in catecholamine synthesis.1

Early vitamin C deficiency presents with nonspecific symptoms, such as malaise, fatigue, and lethargy, followed by the development of anemia, myalgia, bone pain, easy bruising, edema, petechiae, perifollicular hemorrhages, corkscrew hairs, gingivitis, poor wound healing, and mood changes. If untreated, jaundice, neuropathy, hemolysis, seizures, and death can occur.2-4

Perifollicular hemorrhages with corkscrew hairs are characteristic of the Dx

The differential diagnosis of vitamin C deficiency includes vasculitis, thrombocytopenia, multiple myeloma, and folliculitis.

Vasculitis typically presents with palpable purpura and is not exclusively perifollicular.5 Thrombocytopenia may present with petechiae, but the petechiae are generally not perifollicular and hair shaft abnormalities are generally absent. Multiple myeloma may present with purpura with minimal trauma and larger ecchymosis that isn’t petechial in appearance. Folliculitis typically presents with folliculocentric pustules that have surrounding erythema, but no hemorrhaging.

Suspect vitamin C deficiency in patients with alcoholism, a poor diet, and those who are critically ill.6 During the physical exam, look for ecchymosis, edema, gingivitis, impaired wound healing, jaundice, and the tell-tale sign of perifollicular hemorrhages with corkscrew hairs.7

If lab values and/or circumstances leave doubt as to whether a true vitamin C deficiency exists, a punch biopsy of an area of perifollicular hemorrhage may be performed. The punch biopsy should demonstrate follicular hyperkeratosis overlying multiple fragmented hair shafts that are surrounded by a perifollicular lymphohistiocytic infiltrate with extravasated red blood cells.4

Treat with vitamin C

Vitamin C can be replaced via the oral or intravenous (IV) route. There is currently no consensus on a single best replacement regimen, but several effective regimens have been reported in the literature.8,9

We started our patient on IV vitamin C 1 g/d, which improved her cutaneous lesions. Unfortunately, though, she succumbed to complications of her liver disease shortly after starting the therapy.

CORRESPONDENCE

Krishna AJ Mutgi, MD, Nationwide Children’s Hospital, 555 S. 18th Street, Columbus, OH 43205; Krishna.Mutgi@nationwidechildrens.org.

1. Chambial S, Dwivedi S, Shukla KK, et al. Vitamin C in disease prevention and cure: an overview. Indian J Clin Biochem. 2013;28:314-328.

2. Touyz LZ. Oral scurvy and periodontal disease. J Can Dent Assoc. 1997;63:837-845.

3. Singh S, Richards SJ, Lykins M, et al. An underdiagnosed ailment: scurvy in a tertiary care academic center. Am J Med Sci. 2015;349:372-373.

4. Al-Dabagh A, Milliron BJ, Strowd L, et al. A disease of the present: scurvy in “well-nourished” patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:e246-e247.

5. Francescone MA, Levitt J. Scurvy masquerading as leukocytoclastic vasculitis: a case report and review of the literature. Cutis. 2005;76:261-266.

6. Holley AD, Osland E, Barnes J, et al. Scurvy: historically a plague of the sailor that remains a consideration in the modern intensive care unit. Intern Med J. 2011;41:283-285.

7. Cinotti E, Perrot JL, Labeille B, et al. A dermoscopic clue for scurvy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:S37-S38.

8. De Luna RH, Colley BJ 3rd, Smith K, et al. Scurvy: an often forgotten cause of bleeding. Am J Hematol. 2003;74:85-87.

9. Stephen R, Utecht T. Scurvy identified in the emergency department: a case report. J Emerg Med. 2001;21:235-237.

A 45-year-old woman presented to our hospital with recurrent cirrhosis and sepsis secondary to a hepatic abscess from Pseudomonas aeromonas and Candida albicans. Ten years earlier, she had received a liver transplant due to sclerosing cholangitis. The patient had a history of nausea from her liver disease and malnutrition due to a diet that consisted predominantly of cereal with minimal fresh fruits and vegetables. Her family reported that she bruised easily and had worsening dry, flaky skin.

The physical examination revealed jaundice, scleral icterus, purpuric macules, superficial desquamation, gingivitis (FIGURE 1), and perifollicular hemorrhages with corkscrew hairs (FIGURES 2 and 3). The patient also had acute kidney injury, delirium, and pancytopenia. She was admitted to the hospital and was started on piperacillin-tazobactam and fluconazole for sepsis, as well as rifaximin and lactulose for hepatic encephalopathy.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Vitamin C deficiency

We diagnosed this patient with vitamin C deficiency (scurvy) based on the fact that she had perifollicular hemorrhages with corkscrew hairs, which is a pathognomonic feature of the deficiency. The diagnosis was confirmed with a blood vitamin C level of 10 mcmol/L (normal range: 11-114 mcmol/L). It’s important to note that a vitamin C level drawn after hospitalization may be falsely normal due to an improved diet during hospitalization, so a normal vitamin C level doesn’t always rule out a deficiency.

Vitamin C is absorbed from the small intestine and excreted renally. A low vitamin C level occurs in the presence of several conditions—specifically alcoholism and critical illnesses such as sepsis, trauma, major surgery, or stroke—possibly due to decreased absorption and increased oxidative stress. Vitamin C is necessary for multiple hydroxylation reactions, including hydroxylation of proline and lysine in collagen synthesis, beta-hydroxybutyric acid in carnitine synthesis, and dopamine-beta-hydroxylase in catecholamine synthesis.1

Early vitamin C deficiency presents with nonspecific symptoms, such as malaise, fatigue, and lethargy, followed by the development of anemia, myalgia, bone pain, easy bruising, edema, petechiae, perifollicular hemorrhages, corkscrew hairs, gingivitis, poor wound healing, and mood changes. If untreated, jaundice, neuropathy, hemolysis, seizures, and death can occur.2-4

Perifollicular hemorrhages with corkscrew hairs are characteristic of the Dx

The differential diagnosis of vitamin C deficiency includes vasculitis, thrombocytopenia, multiple myeloma, and folliculitis.

Vasculitis typically presents with palpable purpura and is not exclusively perifollicular.5 Thrombocytopenia may present with petechiae, but the petechiae are generally not perifollicular and hair shaft abnormalities are generally absent. Multiple myeloma may present with purpura with minimal trauma and larger ecchymosis that isn’t petechial in appearance. Folliculitis typically presents with folliculocentric pustules that have surrounding erythema, but no hemorrhaging.

Suspect vitamin C deficiency in patients with alcoholism, a poor diet, and those who are critically ill.6 During the physical exam, look for ecchymosis, edema, gingivitis, impaired wound healing, jaundice, and the tell-tale sign of perifollicular hemorrhages with corkscrew hairs.7

If lab values and/or circumstances leave doubt as to whether a true vitamin C deficiency exists, a punch biopsy of an area of perifollicular hemorrhage may be performed. The punch biopsy should demonstrate follicular hyperkeratosis overlying multiple fragmented hair shafts that are surrounded by a perifollicular lymphohistiocytic infiltrate with extravasated red blood cells.4

Treat with vitamin C

Vitamin C can be replaced via the oral or intravenous (IV) route. There is currently no consensus on a single best replacement regimen, but several effective regimens have been reported in the literature.8,9

We started our patient on IV vitamin C 1 g/d, which improved her cutaneous lesions. Unfortunately, though, she succumbed to complications of her liver disease shortly after starting the therapy.

CORRESPONDENCE

Krishna AJ Mutgi, MD, Nationwide Children’s Hospital, 555 S. 18th Street, Columbus, OH 43205; Krishna.Mutgi@nationwidechildrens.org.

A 45-year-old woman presented to our hospital with recurrent cirrhosis and sepsis secondary to a hepatic abscess from Pseudomonas aeromonas and Candida albicans. Ten years earlier, she had received a liver transplant due to sclerosing cholangitis. The patient had a history of nausea from her liver disease and malnutrition due to a diet that consisted predominantly of cereal with minimal fresh fruits and vegetables. Her family reported that she bruised easily and had worsening dry, flaky skin.

The physical examination revealed jaundice, scleral icterus, purpuric macules, superficial desquamation, gingivitis (FIGURE 1), and perifollicular hemorrhages with corkscrew hairs (FIGURES 2 and 3). The patient also had acute kidney injury, delirium, and pancytopenia. She was admitted to the hospital and was started on piperacillin-tazobactam and fluconazole for sepsis, as well as rifaximin and lactulose for hepatic encephalopathy.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Vitamin C deficiency

We diagnosed this patient with vitamin C deficiency (scurvy) based on the fact that she had perifollicular hemorrhages with corkscrew hairs, which is a pathognomonic feature of the deficiency. The diagnosis was confirmed with a blood vitamin C level of 10 mcmol/L (normal range: 11-114 mcmol/L). It’s important to note that a vitamin C level drawn after hospitalization may be falsely normal due to an improved diet during hospitalization, so a normal vitamin C level doesn’t always rule out a deficiency.

Vitamin C is absorbed from the small intestine and excreted renally. A low vitamin C level occurs in the presence of several conditions—specifically alcoholism and critical illnesses such as sepsis, trauma, major surgery, or stroke—possibly due to decreased absorption and increased oxidative stress. Vitamin C is necessary for multiple hydroxylation reactions, including hydroxylation of proline and lysine in collagen synthesis, beta-hydroxybutyric acid in carnitine synthesis, and dopamine-beta-hydroxylase in catecholamine synthesis.1

Early vitamin C deficiency presents with nonspecific symptoms, such as malaise, fatigue, and lethargy, followed by the development of anemia, myalgia, bone pain, easy bruising, edema, petechiae, perifollicular hemorrhages, corkscrew hairs, gingivitis, poor wound healing, and mood changes. If untreated, jaundice, neuropathy, hemolysis, seizures, and death can occur.2-4

Perifollicular hemorrhages with corkscrew hairs are characteristic of the Dx

The differential diagnosis of vitamin C deficiency includes vasculitis, thrombocytopenia, multiple myeloma, and folliculitis.

Vasculitis typically presents with palpable purpura and is not exclusively perifollicular.5 Thrombocytopenia may present with petechiae, but the petechiae are generally not perifollicular and hair shaft abnormalities are generally absent. Multiple myeloma may present with purpura with minimal trauma and larger ecchymosis that isn’t petechial in appearance. Folliculitis typically presents with folliculocentric pustules that have surrounding erythema, but no hemorrhaging.

Suspect vitamin C deficiency in patients with alcoholism, a poor diet, and those who are critically ill.6 During the physical exam, look for ecchymosis, edema, gingivitis, impaired wound healing, jaundice, and the tell-tale sign of perifollicular hemorrhages with corkscrew hairs.7

If lab values and/or circumstances leave doubt as to whether a true vitamin C deficiency exists, a punch biopsy of an area of perifollicular hemorrhage may be performed. The punch biopsy should demonstrate follicular hyperkeratosis overlying multiple fragmented hair shafts that are surrounded by a perifollicular lymphohistiocytic infiltrate with extravasated red blood cells.4

Treat with vitamin C

Vitamin C can be replaced via the oral or intravenous (IV) route. There is currently no consensus on a single best replacement regimen, but several effective regimens have been reported in the literature.8,9

We started our patient on IV vitamin C 1 g/d, which improved her cutaneous lesions. Unfortunately, though, she succumbed to complications of her liver disease shortly after starting the therapy.

CORRESPONDENCE

Krishna AJ Mutgi, MD, Nationwide Children’s Hospital, 555 S. 18th Street, Columbus, OH 43205; Krishna.Mutgi@nationwidechildrens.org.

1. Chambial S, Dwivedi S, Shukla KK, et al. Vitamin C in disease prevention and cure: an overview. Indian J Clin Biochem. 2013;28:314-328.

2. Touyz LZ. Oral scurvy and periodontal disease. J Can Dent Assoc. 1997;63:837-845.

3. Singh S, Richards SJ, Lykins M, et al. An underdiagnosed ailment: scurvy in a tertiary care academic center. Am J Med Sci. 2015;349:372-373.

4. Al-Dabagh A, Milliron BJ, Strowd L, et al. A disease of the present: scurvy in “well-nourished” patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:e246-e247.

5. Francescone MA, Levitt J. Scurvy masquerading as leukocytoclastic vasculitis: a case report and review of the literature. Cutis. 2005;76:261-266.

6. Holley AD, Osland E, Barnes J, et al. Scurvy: historically a plague of the sailor that remains a consideration in the modern intensive care unit. Intern Med J. 2011;41:283-285.

7. Cinotti E, Perrot JL, Labeille B, et al. A dermoscopic clue for scurvy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:S37-S38.

8. De Luna RH, Colley BJ 3rd, Smith K, et al. Scurvy: an often forgotten cause of bleeding. Am J Hematol. 2003;74:85-87.

9. Stephen R, Utecht T. Scurvy identified in the emergency department: a case report. J Emerg Med. 2001;21:235-237.

1. Chambial S, Dwivedi S, Shukla KK, et al. Vitamin C in disease prevention and cure: an overview. Indian J Clin Biochem. 2013;28:314-328.

2. Touyz LZ. Oral scurvy and periodontal disease. J Can Dent Assoc. 1997;63:837-845.

3. Singh S, Richards SJ, Lykins M, et al. An underdiagnosed ailment: scurvy in a tertiary care academic center. Am J Med Sci. 2015;349:372-373.

4. Al-Dabagh A, Milliron BJ, Strowd L, et al. A disease of the present: scurvy in “well-nourished” patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:e246-e247.

5. Francescone MA, Levitt J. Scurvy masquerading as leukocytoclastic vasculitis: a case report and review of the literature. Cutis. 2005;76:261-266.

6. Holley AD, Osland E, Barnes J, et al. Scurvy: historically a plague of the sailor that remains a consideration in the modern intensive care unit. Intern Med J. 2011;41:283-285.

7. Cinotti E, Perrot JL, Labeille B, et al. A dermoscopic clue for scurvy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:S37-S38.

8. De Luna RH, Colley BJ 3rd, Smith K, et al. Scurvy: an often forgotten cause of bleeding. Am J Hematol. 2003;74:85-87.

9. Stephen R, Utecht T. Scurvy identified in the emergency department: a case report. J Emerg Med. 2001;21:235-237.