User login

Survey: Steady Increase in Complementary Alternative Medicine (CAM) Offerings in U.S. Hospitals

According to a survey released last fall by the Health Forum, a subsidiary of the American Hospital Association, and the Samueli Institute of Alexandria, Va., complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) services in responding hospitals increased to 42% in 2010 from 37% in 2007.

The fourth Complementary and Alternative Medicine Survey of Hospitals is a follow-up report to the 2007 survey, which The Hospitalist featured in January 2010.

Twelve percent of 5,858 hospitals answered a 42-question instrument in 2010, according to Sita Ananth, MHA, director of knowledge services at the Samueli Institute and study report author. The results, Ananth says, showed that the hospitals most likely to offer CAM were urban and tended to be either medium-size (50-299 beds) or large (500+ beds) institutions.

What’s driving the increase? She believes that hospitals are simply responding to patients’ desire to have “the best that both conventional and alternative medicine can offer.”

—Sita Ananth, MHA, director of knowledge services at the Samueli Institute and study report author

Sixty-five percent of hospitals responding to the survey offer CAM therapies for pain management. That figure is echoed in a 2008 National Health Statistics report (PDF) published by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Back pain, neck pain, and joint pain were the three top reasons for using CAM, according to the CDC report.

“Adjacent” Treatment

Hospitalist Sanjay Reddy, MD, assistant clinical professor of medicine in the Department of Medicine at the University of California at San Francisco (UCSF), says acupuncture can be a valuable adjunct when treating patients for pain, chemotherapy-induced nausea, and insomnia. He is a trained acupuncturist and has studied complementary therapies extensively. He also is interested in exploring ways to incorporate acupuncture into the UCSF’s Osher Center for Integrative Medicine program.

David H. Gorski, MD, PhD, FACS, associate professor of surgery and director of the Breast Cancer Multidisciplinary Team at the Barbara Ann Karmanos Cancer Institute at Wayne State University School of Medicine in Detroit, strenuously objects to the incorporation of alternative therapies (often under the moniker of “integrative medicine”) in the hospital setting.

“If you accept the premise that medicine should be based in sound science and evidence, then we have an obligation not to be offering treatments that are not based in science,” he asserts. Dr. Gorski, who also blogs on such topics, finds that many of those who endorse integrative medicine have become “true believers,” and that some are mixing pseudo-science with science.

In an August 2011 post regarding the College of Physicians and Surgeons of Ontario’s draft policy on alternative treatments, Dr. Gorski wrote: “Competent adults have every right to seek out non-science-based medicine if that is what they desire. However, informed consent mandates that physicians who encounter such patients provide an honest professional assessment of such treatments based on science.”

Dr. Reddy notes that with appropriate disclosure, offering a modality such as acupuncture can be appropriate. For example, in the setting of pain relief, acupuncture offers a less sedative approach. He explains that Chinese diagnostics and treatment approaches are slightly different, so it’s difficult to study them in the context of randomized trials. (Click here to listen to more of Dr. Reddy’s discussion of appropriate indications for acupuncture.)

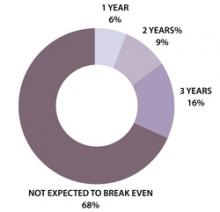

In the Health Forum/Samueli Institute survey, 57% of hospitals reported that their programs were not yet breaking even and only 16% said they'd be breaking even in three years (see Figure 1). In light of these results, Ananth says, hospitals undertaking complementary services should “start small and not have high expectations of breaking even for several years.”

Gretchen Henkel is a freelance writer in California.

Herbals another Matter

In the 2010 Health Forum/Samueli Institute survey, 82% of responding hospitals reported that they did not offer herbal supplements in their hospital pharmacies. Study author Sita Ananth surmises that most hospitals may be “playing it safe” by offering noninvasive therapies. Hospitalists are aware of the potentially dangerous interactions between herbal supplements and mainstream treatments, Dr. Reddy says.

A majority of the hospitals Ananth queried (67%) reported having existing policies regarding patients’ use of herbal and nutritional supplements during hospitalization. To avoid adverse events, “It’s really crucial that they are asking the right questions of their patients,” she says.—GH

According to a survey released last fall by the Health Forum, a subsidiary of the American Hospital Association, and the Samueli Institute of Alexandria, Va., complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) services in responding hospitals increased to 42% in 2010 from 37% in 2007.

The fourth Complementary and Alternative Medicine Survey of Hospitals is a follow-up report to the 2007 survey, which The Hospitalist featured in January 2010.

Twelve percent of 5,858 hospitals answered a 42-question instrument in 2010, according to Sita Ananth, MHA, director of knowledge services at the Samueli Institute and study report author. The results, Ananth says, showed that the hospitals most likely to offer CAM were urban and tended to be either medium-size (50-299 beds) or large (500+ beds) institutions.

What’s driving the increase? She believes that hospitals are simply responding to patients’ desire to have “the best that both conventional and alternative medicine can offer.”

—Sita Ananth, MHA, director of knowledge services at the Samueli Institute and study report author

Sixty-five percent of hospitals responding to the survey offer CAM therapies for pain management. That figure is echoed in a 2008 National Health Statistics report (PDF) published by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Back pain, neck pain, and joint pain were the three top reasons for using CAM, according to the CDC report.

“Adjacent” Treatment

Hospitalist Sanjay Reddy, MD, assistant clinical professor of medicine in the Department of Medicine at the University of California at San Francisco (UCSF), says acupuncture can be a valuable adjunct when treating patients for pain, chemotherapy-induced nausea, and insomnia. He is a trained acupuncturist and has studied complementary therapies extensively. He also is interested in exploring ways to incorporate acupuncture into the UCSF’s Osher Center for Integrative Medicine program.

David H. Gorski, MD, PhD, FACS, associate professor of surgery and director of the Breast Cancer Multidisciplinary Team at the Barbara Ann Karmanos Cancer Institute at Wayne State University School of Medicine in Detroit, strenuously objects to the incorporation of alternative therapies (often under the moniker of “integrative medicine”) in the hospital setting.

“If you accept the premise that medicine should be based in sound science and evidence, then we have an obligation not to be offering treatments that are not based in science,” he asserts. Dr. Gorski, who also blogs on such topics, finds that many of those who endorse integrative medicine have become “true believers,” and that some are mixing pseudo-science with science.

In an August 2011 post regarding the College of Physicians and Surgeons of Ontario’s draft policy on alternative treatments, Dr. Gorski wrote: “Competent adults have every right to seek out non-science-based medicine if that is what they desire. However, informed consent mandates that physicians who encounter such patients provide an honest professional assessment of such treatments based on science.”

Dr. Reddy notes that with appropriate disclosure, offering a modality such as acupuncture can be appropriate. For example, in the setting of pain relief, acupuncture offers a less sedative approach. He explains that Chinese diagnostics and treatment approaches are slightly different, so it’s difficult to study them in the context of randomized trials. (Click here to listen to more of Dr. Reddy’s discussion of appropriate indications for acupuncture.)

In the Health Forum/Samueli Institute survey, 57% of hospitals reported that their programs were not yet breaking even and only 16% said they'd be breaking even in three years (see Figure 1). In light of these results, Ananth says, hospitals undertaking complementary services should “start small and not have high expectations of breaking even for several years.”

Gretchen Henkel is a freelance writer in California.

Herbals another Matter

In the 2010 Health Forum/Samueli Institute survey, 82% of responding hospitals reported that they did not offer herbal supplements in their hospital pharmacies. Study author Sita Ananth surmises that most hospitals may be “playing it safe” by offering noninvasive therapies. Hospitalists are aware of the potentially dangerous interactions between herbal supplements and mainstream treatments, Dr. Reddy says.

A majority of the hospitals Ananth queried (67%) reported having existing policies regarding patients’ use of herbal and nutritional supplements during hospitalization. To avoid adverse events, “It’s really crucial that they are asking the right questions of their patients,” she says.—GH

According to a survey released last fall by the Health Forum, a subsidiary of the American Hospital Association, and the Samueli Institute of Alexandria, Va., complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) services in responding hospitals increased to 42% in 2010 from 37% in 2007.

The fourth Complementary and Alternative Medicine Survey of Hospitals is a follow-up report to the 2007 survey, which The Hospitalist featured in January 2010.

Twelve percent of 5,858 hospitals answered a 42-question instrument in 2010, according to Sita Ananth, MHA, director of knowledge services at the Samueli Institute and study report author. The results, Ananth says, showed that the hospitals most likely to offer CAM were urban and tended to be either medium-size (50-299 beds) or large (500+ beds) institutions.

What’s driving the increase? She believes that hospitals are simply responding to patients’ desire to have “the best that both conventional and alternative medicine can offer.”

—Sita Ananth, MHA, director of knowledge services at the Samueli Institute and study report author

Sixty-five percent of hospitals responding to the survey offer CAM therapies for pain management. That figure is echoed in a 2008 National Health Statistics report (PDF) published by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Back pain, neck pain, and joint pain were the three top reasons for using CAM, according to the CDC report.

“Adjacent” Treatment

Hospitalist Sanjay Reddy, MD, assistant clinical professor of medicine in the Department of Medicine at the University of California at San Francisco (UCSF), says acupuncture can be a valuable adjunct when treating patients for pain, chemotherapy-induced nausea, and insomnia. He is a trained acupuncturist and has studied complementary therapies extensively. He also is interested in exploring ways to incorporate acupuncture into the UCSF’s Osher Center for Integrative Medicine program.

David H. Gorski, MD, PhD, FACS, associate professor of surgery and director of the Breast Cancer Multidisciplinary Team at the Barbara Ann Karmanos Cancer Institute at Wayne State University School of Medicine in Detroit, strenuously objects to the incorporation of alternative therapies (often under the moniker of “integrative medicine”) in the hospital setting.

“If you accept the premise that medicine should be based in sound science and evidence, then we have an obligation not to be offering treatments that are not based in science,” he asserts. Dr. Gorski, who also blogs on such topics, finds that many of those who endorse integrative medicine have become “true believers,” and that some are mixing pseudo-science with science.

In an August 2011 post regarding the College of Physicians and Surgeons of Ontario’s draft policy on alternative treatments, Dr. Gorski wrote: “Competent adults have every right to seek out non-science-based medicine if that is what they desire. However, informed consent mandates that physicians who encounter such patients provide an honest professional assessment of such treatments based on science.”

Dr. Reddy notes that with appropriate disclosure, offering a modality such as acupuncture can be appropriate. For example, in the setting of pain relief, acupuncture offers a less sedative approach. He explains that Chinese diagnostics and treatment approaches are slightly different, so it’s difficult to study them in the context of randomized trials. (Click here to listen to more of Dr. Reddy’s discussion of appropriate indications for acupuncture.)

In the Health Forum/Samueli Institute survey, 57% of hospitals reported that their programs were not yet breaking even and only 16% said they'd be breaking even in three years (see Figure 1). In light of these results, Ananth says, hospitals undertaking complementary services should “start small and not have high expectations of breaking even for several years.”

Gretchen Henkel is a freelance writer in California.

Herbals another Matter

In the 2010 Health Forum/Samueli Institute survey, 82% of responding hospitals reported that they did not offer herbal supplements in their hospital pharmacies. Study author Sita Ananth surmises that most hospitals may be “playing it safe” by offering noninvasive therapies. Hospitalists are aware of the potentially dangerous interactions between herbal supplements and mainstream treatments, Dr. Reddy says.

A majority of the hospitals Ananth queried (67%) reported having existing policies regarding patients’ use of herbal and nutritional supplements during hospitalization. To avoid adverse events, “It’s really crucial that they are asking the right questions of their patients,” she says.—GH

ONLINE EXCLUSIVE: Patient Engagement Critical

Because “med rec” is a responsibility shared by providers, patients, and families, it’s important to engage everyone in the process.

Although the patient is—and should be, if capable—the ultimate owner of the correct healthcare record, “We have a responsibility as healthcare providers to help them be successful,” says Blake Lesselroth, MD, assistant professor of medicine at Oregon Health Sciences University and director of the Portland Patient Safety Center of Inquiry at the Portland VA Medical Center. “We haven’t done that.”

Hospitals and healthcare systems use varied strategies for including and empowering patients in the med-rec process:

- The Joint Commission launched its “Speak Up” program (PDF), which gives patients tools to help avoid mistakes with their medications.

- Last year, Southern California Kaiser Permanente rolled out its “medicine in a bag” initiative, according to hospitalist David Wong, MD. Patients are instructed to bring all of their medications (in their respective containers) to the hospital when they are admitted. Then, as the med-rec process is completed, medications are placed in green (take these meds), red (stop these meds), and yellow bags (which may include herbal supplements or other questionable items). In addition, orders are written and explained in simple language: i.e., “twice per day” instead of b.i.d. When patients visit their PCP after discharge, they are instructed to bring the color-coded bags so that the PCPs can verify the coherence of the orders. Clarity reports are filed for each physician, allowing a feedback mechanism to make sure that med rec is taking place.

- Open charting at Griffin Hospital in Derby, Conn., in affiliation with the principles of the nonprofit, patient-centered Planetree organization, supplies another means of double-checking the veracity of patients’ medication lists. It also allows for meaningful patient education and dialogue about treatment and discharge plans, says Dorothea Wild, MD, Griffin Hospital’s chief hospitalist.

Gretchen Henkel is a freelance writer based in California.

Because “med rec” is a responsibility shared by providers, patients, and families, it’s important to engage everyone in the process.

Although the patient is—and should be, if capable—the ultimate owner of the correct healthcare record, “We have a responsibility as healthcare providers to help them be successful,” says Blake Lesselroth, MD, assistant professor of medicine at Oregon Health Sciences University and director of the Portland Patient Safety Center of Inquiry at the Portland VA Medical Center. “We haven’t done that.”

Hospitals and healthcare systems use varied strategies for including and empowering patients in the med-rec process:

- The Joint Commission launched its “Speak Up” program (PDF), which gives patients tools to help avoid mistakes with their medications.

- Last year, Southern California Kaiser Permanente rolled out its “medicine in a bag” initiative, according to hospitalist David Wong, MD. Patients are instructed to bring all of their medications (in their respective containers) to the hospital when they are admitted. Then, as the med-rec process is completed, medications are placed in green (take these meds), red (stop these meds), and yellow bags (which may include herbal supplements or other questionable items). In addition, orders are written and explained in simple language: i.e., “twice per day” instead of b.i.d. When patients visit their PCP after discharge, they are instructed to bring the color-coded bags so that the PCPs can verify the coherence of the orders. Clarity reports are filed for each physician, allowing a feedback mechanism to make sure that med rec is taking place.

- Open charting at Griffin Hospital in Derby, Conn., in affiliation with the principles of the nonprofit, patient-centered Planetree organization, supplies another means of double-checking the veracity of patients’ medication lists. It also allows for meaningful patient education and dialogue about treatment and discharge plans, says Dorothea Wild, MD, Griffin Hospital’s chief hospitalist.

Gretchen Henkel is a freelance writer based in California.

Because “med rec” is a responsibility shared by providers, patients, and families, it’s important to engage everyone in the process.

Although the patient is—and should be, if capable—the ultimate owner of the correct healthcare record, “We have a responsibility as healthcare providers to help them be successful,” says Blake Lesselroth, MD, assistant professor of medicine at Oregon Health Sciences University and director of the Portland Patient Safety Center of Inquiry at the Portland VA Medical Center. “We haven’t done that.”

Hospitals and healthcare systems use varied strategies for including and empowering patients in the med-rec process:

- The Joint Commission launched its “Speak Up” program (PDF), which gives patients tools to help avoid mistakes with their medications.

- Last year, Southern California Kaiser Permanente rolled out its “medicine in a bag” initiative, according to hospitalist David Wong, MD. Patients are instructed to bring all of their medications (in their respective containers) to the hospital when they are admitted. Then, as the med-rec process is completed, medications are placed in green (take these meds), red (stop these meds), and yellow bags (which may include herbal supplements or other questionable items). In addition, orders are written and explained in simple language: i.e., “twice per day” instead of b.i.d. When patients visit their PCP after discharge, they are instructed to bring the color-coded bags so that the PCPs can verify the coherence of the orders. Clarity reports are filed for each physician, allowing a feedback mechanism to make sure that med rec is taking place.

- Open charting at Griffin Hospital in Derby, Conn., in affiliation with the principles of the nonprofit, patient-centered Planetree organization, supplies another means of double-checking the veracity of patients’ medication lists. It also allows for meaningful patient education and dialogue about treatment and discharge plans, says Dorothea Wild, MD, Griffin Hospital’s chief hospitalist.

Gretchen Henkel is a freelance writer based in California.

ONLINE EXCLUSIVE: Med-Rec Experts Discuss Prevention Strategies

Click here to listen to Dr. Tsomides

Click here to listen to Dr. Lesselroth

Click here to listen to Dr. Tsomides

Click here to listen to Dr. Lesselroth

Click here to listen to Dr. Tsomides

Click here to listen to Dr. Lesselroth

Put Medical School Debt in Perspective As You Enter Job Market

According to the Association of American Medical Colleges, the average debt for a young physician graduating from medical school in 2010 was $158,000. How do you keep that debt in perspective as you plot your career path?

Look at the Bigger Picture

Making plans for repaying medical school debt should start before your job search, says Danielle Salovich, president of the American Medical Student Association in Sterling, Va. “Part of your medical school exit interview should include campus financial advisors who give you options for loan repayment,” she says.

—Danielle Salovich, president, American Medical Student Association, Sterling, Va.

Consider what payment schedule will work best with your projected budget. Many medical students do not have financial or business backgrounds, so she advises enlisting the services of a trusted financial advisor.

Variety of Options

Recruitment packages for early-career hospitalists vary from region to region, based on an area’s appeal and marketplace pressures, says Kent McMackin, senior vice president of Physician Services for Cogent HMG in Brentwood, Tenn. Hospitals are looking to control costs in the wake of regulatory and reimbursement pressures. One alternative is to investigate loan repayment and scholarship programs.

Bonuses and Benefits

Many young physicians are especially interested in the size of signing bonuses, which can be a plus, Salovich says, if they’re planning on making a down payment on a house or taking a chunk out of their school loan principal. Joel Greenwald, MD, CFP, partner at Sterling Retirement Resources in St. Louis Park, Minn., cautions against the “lure” of a big signing bonus. More important, he says, is the total compensation and benefits package. Comprehensive disability insurance should be at the top of the list, he says, since your ability to work is your most important asset.

Another factor to consider, McMackin says, is the type of mentoring available when you start that first job.

“Physicians work so hard in medical school, where they are not taught about how to develop and understand the inter-relationships between executives in the C-suite, X-ray, dietary, and other services in the hospital,” he says. “We need to make sure that physicians have access to national networks of mentors and to best practices and information-sharing.”

Those principles—taught at Cogent HMG Academy, SHM’s Leadership Academy, and others—help build career sustainability, he says.

Above all, keep your individual goals in mind and make a decision that works best with your particular situation. “I still believe,” Salovich says, “that a medical education is a wise investment.”

Gretchen Henkel is a freelance writer based in California.

Know What You Owe

Debt management “starts with getting a handle on your loan obligations,” Dr. Greenwald says. Start with a spreadsheet listing all your lenders, principal balances, and interest rates. Then arrange those obligations in descending order, with the highest-interest balances at the top. It’s more important to chisel down the high-interest loans first (e.g. credit-card debt) and to keep paying the minimum amounts on the lower ones. In addition, some interest is tax-deductible, so it is not as toxic as a high-interest credit card balance.

Here are some resources to help:

- Loan Repayment and Scholarship Program Resources.

- The National Health Service Corps offers student loan assistance for providers serving in communities with limited access to healthcare.

- AMSA offers a variety of information and tools to help organize a student-loan payoff plan.

According to the Association of American Medical Colleges, the average debt for a young physician graduating from medical school in 2010 was $158,000. How do you keep that debt in perspective as you plot your career path?

Look at the Bigger Picture

Making plans for repaying medical school debt should start before your job search, says Danielle Salovich, president of the American Medical Student Association in Sterling, Va. “Part of your medical school exit interview should include campus financial advisors who give you options for loan repayment,” she says.

—Danielle Salovich, president, American Medical Student Association, Sterling, Va.

Consider what payment schedule will work best with your projected budget. Many medical students do not have financial or business backgrounds, so she advises enlisting the services of a trusted financial advisor.

Variety of Options

Recruitment packages for early-career hospitalists vary from region to region, based on an area’s appeal and marketplace pressures, says Kent McMackin, senior vice president of Physician Services for Cogent HMG in Brentwood, Tenn. Hospitals are looking to control costs in the wake of regulatory and reimbursement pressures. One alternative is to investigate loan repayment and scholarship programs.

Bonuses and Benefits

Many young physicians are especially interested in the size of signing bonuses, which can be a plus, Salovich says, if they’re planning on making a down payment on a house or taking a chunk out of their school loan principal. Joel Greenwald, MD, CFP, partner at Sterling Retirement Resources in St. Louis Park, Minn., cautions against the “lure” of a big signing bonus. More important, he says, is the total compensation and benefits package. Comprehensive disability insurance should be at the top of the list, he says, since your ability to work is your most important asset.

Another factor to consider, McMackin says, is the type of mentoring available when you start that first job.

“Physicians work so hard in medical school, where they are not taught about how to develop and understand the inter-relationships between executives in the C-suite, X-ray, dietary, and other services in the hospital,” he says. “We need to make sure that physicians have access to national networks of mentors and to best practices and information-sharing.”

Those principles—taught at Cogent HMG Academy, SHM’s Leadership Academy, and others—help build career sustainability, he says.

Above all, keep your individual goals in mind and make a decision that works best with your particular situation. “I still believe,” Salovich says, “that a medical education is a wise investment.”

Gretchen Henkel is a freelance writer based in California.

Know What You Owe

Debt management “starts with getting a handle on your loan obligations,” Dr. Greenwald says. Start with a spreadsheet listing all your lenders, principal balances, and interest rates. Then arrange those obligations in descending order, with the highest-interest balances at the top. It’s more important to chisel down the high-interest loans first (e.g. credit-card debt) and to keep paying the minimum amounts on the lower ones. In addition, some interest is tax-deductible, so it is not as toxic as a high-interest credit card balance.

Here are some resources to help:

- Loan Repayment and Scholarship Program Resources.

- The National Health Service Corps offers student loan assistance for providers serving in communities with limited access to healthcare.

- AMSA offers a variety of information and tools to help organize a student-loan payoff plan.

According to the Association of American Medical Colleges, the average debt for a young physician graduating from medical school in 2010 was $158,000. How do you keep that debt in perspective as you plot your career path?

Look at the Bigger Picture

Making plans for repaying medical school debt should start before your job search, says Danielle Salovich, president of the American Medical Student Association in Sterling, Va. “Part of your medical school exit interview should include campus financial advisors who give you options for loan repayment,” she says.

—Danielle Salovich, president, American Medical Student Association, Sterling, Va.

Consider what payment schedule will work best with your projected budget. Many medical students do not have financial or business backgrounds, so she advises enlisting the services of a trusted financial advisor.

Variety of Options

Recruitment packages for early-career hospitalists vary from region to region, based on an area’s appeal and marketplace pressures, says Kent McMackin, senior vice president of Physician Services for Cogent HMG in Brentwood, Tenn. Hospitals are looking to control costs in the wake of regulatory and reimbursement pressures. One alternative is to investigate loan repayment and scholarship programs.

Bonuses and Benefits

Many young physicians are especially interested in the size of signing bonuses, which can be a plus, Salovich says, if they’re planning on making a down payment on a house or taking a chunk out of their school loan principal. Joel Greenwald, MD, CFP, partner at Sterling Retirement Resources in St. Louis Park, Minn., cautions against the “lure” of a big signing bonus. More important, he says, is the total compensation and benefits package. Comprehensive disability insurance should be at the top of the list, he says, since your ability to work is your most important asset.

Another factor to consider, McMackin says, is the type of mentoring available when you start that first job.

“Physicians work so hard in medical school, where they are not taught about how to develop and understand the inter-relationships between executives in the C-suite, X-ray, dietary, and other services in the hospital,” he says. “We need to make sure that physicians have access to national networks of mentors and to best practices and information-sharing.”

Those principles—taught at Cogent HMG Academy, SHM’s Leadership Academy, and others—help build career sustainability, he says.

Above all, keep your individual goals in mind and make a decision that works best with your particular situation. “I still believe,” Salovich says, “that a medical education is a wise investment.”

Gretchen Henkel is a freelance writer based in California.

Know What You Owe

Debt management “starts with getting a handle on your loan obligations,” Dr. Greenwald says. Start with a spreadsheet listing all your lenders, principal balances, and interest rates. Then arrange those obligations in descending order, with the highest-interest balances at the top. It’s more important to chisel down the high-interest loans first (e.g. credit-card debt) and to keep paying the minimum amounts on the lower ones. In addition, some interest is tax-deductible, so it is not as toxic as a high-interest credit card balance.

Here are some resources to help:

- Loan Repayment and Scholarship Program Resources.

- The National Health Service Corps offers student loan assistance for providers serving in communities with limited access to healthcare.

- AMSA offers a variety of information and tools to help organize a student-loan payoff plan.

Reconciliation Act

Pharmacist Kristine M. Gleason, RPh, got the chance to personally test her ability to help ED providers with medication reconciliation—known by most in healthcare as “med rec”—when she broke her leg a couple of years ago. No problem, she thought: “I’ve been involved in med-rec efforts for eight-plus years.”

But when asked to provide her current medications, Gleason, who is the clinical quality leader in the department of clinical quality and analytics at Northwestern Memorial Hospital in Chicago, says she was in pain and overwhelmed. “I couldn’t even remember my children’s names, let alone the names and dosages of my aspirin and my thyroid medication,” she says. Moreover, she didn’t carry a list in her wallet because “I’m a pharmacist and I do med rec,” she says.

Gleason’s experience highlights why, six years after The Joint Commission introduced medication reconciliation as National Patient Safety Goal (NPSG) No. 8, hospitals and providers still struggle with the process.1 As a younger patient, Gleason took few medications. But for the majority of elderly inpatients with comorbid conditions, just establishing the patient’s medication list can bring the whole process to a halt; without that foundational list, reconciling other medications becomes problematic.

Although the commission has taken the goals under review and has, since July 1, required compliance with the revised NPSG 03.06.01 (see “Additional Resources,”), hospitalization-associated adverse drug events continue to mount. A recent Canadian study caused a ripple this summer with its findings that patients discharged from acute-care hospitals were at higher risk for unintentional discontinuation of their medications prescribed for chronic diseases than control groups, and those who had an ICU stay are at even higher risk.2

There’s been no shortage of med-rec initiatives in recent years. Medication reconciliation was at the top of the list for ways to prevent errors when the Institute for Healthcare Improvement launched its “5 Million Lives Campaign” in December 2006. SHM weighed in on the issue in 2010 with a consensus statement on key principles and necessary first steps in med rec.3

“This isn’t a new problem,” Gleason says. “Med rec has become more heightened because we have many more medications and complex therapies, more care providers, more specialists—more players, if you will.”

The March launch of the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program, part of the Centers for Medicaid & Medicare Services’ (CMS) Inpatient Prospective Payment System, will again shine the spotlight on med rec’s role in the prevention of 30-day readmissions. The Hospitalist talked with researchers, pharmacists, and hospitalists about the reasons behind medication discrepancies, and their strategies for addressing mismatches.

Why So Difficult?

The goal of medication reconciliation is to generate and maintain an accurate and coherent record of patients’ medications across all transitions of care, which sounds straightforward enough. But the process involves much more than just checking items off a list, says Jeffrey Schnipper, MD, MPH, FHM, currently the principal investigator for the $1.5 million study funded by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) to research and implement best practices in med rec, dubbed MARQUIS (Multicenter Medication Reconciliation Quality Improvement Study). Those immersed in med rec know that it’s nonlinear, multilayered, and surprisingly complex, requiring partnerships among diverse providers across many domains of care.

“Medication reconciliation gets right at all the weaknesses of our healthcare system,” says Dr. Schnipper, a hospitalist and director of clinical research for the HM service at Brigham and Women’s Hospital (BWH) and assistant professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, both in Boston. “We have an excellent healthcare system in so many ways, but what we do not do such a good job of is coordination of care across settings, easy transfer of information, and having one person who is responsible for the accuracy of a patient’s health information.”

Dr. Schnipper’s studies attest to the common occurrence of unintentional medical discrepancies, pointing to the need for accurate medication histories, identifying high-risk patients for intensive interventions, and careful med rec at time of discharge.4

Other factors might come into play, says Ted Tsomides, MD, PhD, an attending physician on the HM service at WakeMed Hospital and assistant professor of medicine at the University of North Carolina’s School of Medicine in Raleigh, N.C. For example, he surmises that a “fatigue factor” sets in for some providers. “After five years of working on any initiative, people get worn out and push it to the back burner, unless they are really incentivized to stay on it,” he says.

List Capture

Medication reconciliation is a multifaceted process, and the first step is to gather the history of medications the patient has been taking. Hospitalist Blake J. Lesselroth, MD, MBI, assistant professor of medicine and medical informatics and director of the Portland Patient Safety Center of Inquiry at the Portland VA Medical Center in Oregon, points out that “the initial exposure to the patient is like a pencil sketch. You start to realize that med rec involves iterative loops of communication between you, the patient, and other knowledge resources (see Figure 1). As you start to pull in more information, you begin to complete your narrative. At the end of hospitalization, you’ve got a vibrant portrait with much more nuance to it. So it can’t be a linear process.”

—Kristine M. Gleason, RPh, clinical quality leader, department of clinical quality and analytics, Northwestern Memorial Hospital, Chicago

The list is dynamic, especially in the ICU setting, says Gleason, where it represents only one point in time.

In a closed system, such as the Veterans Administration or Kaiser Permanente, it’s often easier to establish a patient’s ongoing medications. With an integrated electronic health record (EHR), providers can call up the patient’s list of medications during admittance to the hospital. Verifying those medications remains critical: The health record lists patients’ prescriptions, but that doesn’t always mean they have actually filled or are taking those medications.

At the Kaiser Permanente Southern California site in Santa Clarita, Calif., where hospitalist David W. Wong, MD, works, pharmacists review their medications with patients when they are admitted, provide any needed consultation, then repeat the process at discharge. “So far,” Dr. Wong says, “this has resulted in the best medication reconciliation that we’ve seen.”

Pharmacy Is Key

In 2006, Kenneth Boockvar, MD, of the James J. Peters VA Medical Center in Bronx, N.Y., found in a pre- and post-intervention study that using pharmacists to ferret out and communicate prescribing discrepancies to physicians resulted in lower risk of adverse drug events (ADEs) for patients transferred between the hospital and the nursing home.5 Likewise, Dr. Schnipper and his colleagues found that using pharmacists to conduct medication reviews, counsel patients at discharge, and make follow-up telephone calls to patients was associated with a lower rate of preventable ADEs 30 days after hospital discharge.6

At United Hospital System’s (UHS) Kenosha Medical Center campus in Kenosha, Wis., pharmacists play a key role in generating medication lists for incoming patients. Hospitalist Corey Black, MD, regional medical director for Cogent HMG, says many patients do not recall their medications or the dosages, so UHS utilizes a team approach: If patients come in during evenings or weekends, pharmacists start calling local pharmacies to track down patients’ medication lists. “We also try to have family members bring in any medication containers they can find,” he adds. Due to a Wisconsin state law mandating nursing homes to send medication lists along with patients, generating a list is much easier.

Dr. Tsomides is a physician sponsor of a new med-rec initiative at WakeMed. With a steering committee that includes representatives from stakeholder services (medicine, nursing, pharmacy, administration, etc.), the group plans to hire and train pharmacy techs who will take home medication lists in the ED, lifting that responsibility from physicians’ task lists.

Is IT the Answer?

Would many of the barriers to med rec go away with universal EHR? So far, the literature has not borne out the superiority of using EHR to facilitate better med rec.

Peter Kaboli and colleagues found that the computerized medication record reflected what patients were actually taking for only 5.3% of the 493 VA patients enrolled in a study at the Iowa City VA.7 Kenneth Boockvar and colleagues at the Bronx VA found no difference in the overall incidence of ADEs caused by medication discrepancies between VA patients with an EHR and non-VA patients without an EHR.8 A group of researchers with Partners HealthCare in Boston evaluated a secure, Web-based patient portal to produce more accurate medication lists. The patients using this system had just as many discrepancies between medication lists and self-reporting as those who did not.9

Dr. Lesselroth, who has devised a patient kiosk touch-screen tool for reconciling patients’ medication lists and has faced barriers when implementing said technology, says med rec is much more “organic” than strictly mechanical. “It invokes theories of learning from the cognitive sciences,” he says. “We haven’t actually built tools that help people with their problem representation, with understanding not just how medications reconcile with the prior setting of care, but whether they make clinical sense within the new context of care. That requires a quantum leap in thinking.”

Re-Brand the Message

Drs. Schnipper and Tsomides believe that when The Joint Committee first coined the term “medication reconciliation” and advanced it as a mandate, most providers associated it with a regulatory requirement, and understandably so. Dr. Schnipper says med rec could be improved if providers think about it in the context of accurate orders that translate to greater patient safety. “After all,” he says, “hospitalists are ultimately responsible for the medication orders written for their patients.

“This is not about regulatory requirements,” he continues. “This is about medication safety and transitions of care. You can spend an hour on deciding what dose of Lasix you want to send this patient home on, but if the patient then takes the wrong dose of Lasix because they don’t know what they were supposed to be taking, then all that good medical care is undone.”

The med rec conversation has come full circle, then, as being truly an issue of delivering patient-centered care. (For more on this topic, visit the-hospitalist.org to read “Patient Engagement Critical.”) Rather than focusing on the sometimes-befuddling term of medication reconciliation, providers should see med rec as part of an integrated medication management process that aims to take better care of patients through prevention and treatment, Gleason says.

The med rec issue is about effective communication at every transition of care. And that’s why, says Dr. Schnipper, “Hospitalists should own this process. We don’t have to do the process entirely by ourselves—and shouldn’t. But we are responsible for errors that happen during transitions in care and we should own these initiatives.”

He notes that all six hospitals enrolled in the MARQUIS study have hospitalists at the forefront of their quality-improvement (QI) efforts.

“Medication reconciliation is potentially a high-risk process, and there are no silver bullets” for globally addressing the process, says Dorothea Wild, MD, chief hospitalist at Griffin Hospital, a 160-bed acute care hospital in Derby, Conn.

—Jeffrey Schnipper, MD, MPH, FHM, hospitalist and director of clinical research, Brigham and Women’s Hospital Hospitalist Service, assistant professor of medicine, Harvard Medical School, Boston

Dr. Wild draws a parallel between med rec and blood transfusions. Just as with correct transfusing procedures, “we envision a process where at least two people independently verify what patients’ medications are,” she says. The meds list is started in the ED by nursing staff, is verified by the ED attending, verified again by the admitting team, and triple-checked by the admitting attending. Thus, says Dr. Wild, med rec becomes a shared responsibility.

Dr. Lesselroth wholeheartedly agrees with the approach.

“This is everybody’s job,” he says. “In a larger world view, med rec is all about trying to find a medication regimen that harmonizes with what the patient can do, that improves their probability of adherence, and that also helps us gather information when the patient returns and we re-embrace them in the care model. Theoretically, then, everybody [interfacing with a patient] becomes a clutch player.”

Gretchen Henkel is a freelance writer in California.

References

- Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations. 2005 Hospital Accreditation Standards. JCO website. Available at: http://www.jointcommissioninternational.org/ JCI-Accredited-Organizations/. Accessed Dec. 7, 2011.

- Bell CM, Brener SS, Gunraj N, et al. Association of ICU or hospital admission with unintentional discontinuation of medications for chronic diseases. JAMA. 2011;306:840-847.

- Greenwald JL, Halasyamani L, Green J, et al. Making inpatient medication patient centered, clinically relevant and implementable: a consensus statement on key principles and necessary first steps. J Hosp Med. 2010;5:477-485.

- Pippins JR, Gandhi TK, Hamann C, et al. Classifying and predicting errors of inpatient medication reconciliation. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23:1414-1422.

- Boockvar KS, Carlson HL, Giambanco V, et al. Medication reconciliation for reducing drug-discrepancy adverse events. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother. 2006;4:236-243.

- Schnipper JL, Kirwin JL, Cotugno MC, et al. Role of pharmacist counseling in preventing adverse drug events after hospitalization. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:565-571.

- Kaboli PJ, McClimon JB, Hoth AB, et al. Assessing the accuracy of computerized medication histories. Am J Manag Care. 2004;10(11 Pt 2):872-877.

- Boockvar KS, Livote EE, Goldstein N, et al. Electronic health records and adverse drug events after patient transfer. Qual Saf Health Care. 2010;5:Epub(Aug 19).

- Staroselsky M, Volk LA, Tsurikova R, et al. An effort to improve electronic health record medication list accuracy between visits: patients’ and physicians’ responses. Int J Med Inform. 2008;77:153-160.

- Gleason KM, McDaniel MR, Feinglass J, et al. Results of the Medications at Transitions and Clinical Handoffs (MATCH) study: an analysis of medication reconciliation errors and risk factors at hospital admission. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25:441-447.

Pharmacist Kristine M. Gleason, RPh, got the chance to personally test her ability to help ED providers with medication reconciliation—known by most in healthcare as “med rec”—when she broke her leg a couple of years ago. No problem, she thought: “I’ve been involved in med-rec efforts for eight-plus years.”

But when asked to provide her current medications, Gleason, who is the clinical quality leader in the department of clinical quality and analytics at Northwestern Memorial Hospital in Chicago, says she was in pain and overwhelmed. “I couldn’t even remember my children’s names, let alone the names and dosages of my aspirin and my thyroid medication,” she says. Moreover, she didn’t carry a list in her wallet because “I’m a pharmacist and I do med rec,” she says.

Gleason’s experience highlights why, six years after The Joint Commission introduced medication reconciliation as National Patient Safety Goal (NPSG) No. 8, hospitals and providers still struggle with the process.1 As a younger patient, Gleason took few medications. But for the majority of elderly inpatients with comorbid conditions, just establishing the patient’s medication list can bring the whole process to a halt; without that foundational list, reconciling other medications becomes problematic.

Although the commission has taken the goals under review and has, since July 1, required compliance with the revised NPSG 03.06.01 (see “Additional Resources,”), hospitalization-associated adverse drug events continue to mount. A recent Canadian study caused a ripple this summer with its findings that patients discharged from acute-care hospitals were at higher risk for unintentional discontinuation of their medications prescribed for chronic diseases than control groups, and those who had an ICU stay are at even higher risk.2

There’s been no shortage of med-rec initiatives in recent years. Medication reconciliation was at the top of the list for ways to prevent errors when the Institute for Healthcare Improvement launched its “5 Million Lives Campaign” in December 2006. SHM weighed in on the issue in 2010 with a consensus statement on key principles and necessary first steps in med rec.3

“This isn’t a new problem,” Gleason says. “Med rec has become more heightened because we have many more medications and complex therapies, more care providers, more specialists—more players, if you will.”

The March launch of the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program, part of the Centers for Medicaid & Medicare Services’ (CMS) Inpatient Prospective Payment System, will again shine the spotlight on med rec’s role in the prevention of 30-day readmissions. The Hospitalist talked with researchers, pharmacists, and hospitalists about the reasons behind medication discrepancies, and their strategies for addressing mismatches.

Why So Difficult?

The goal of medication reconciliation is to generate and maintain an accurate and coherent record of patients’ medications across all transitions of care, which sounds straightforward enough. But the process involves much more than just checking items off a list, says Jeffrey Schnipper, MD, MPH, FHM, currently the principal investigator for the $1.5 million study funded by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) to research and implement best practices in med rec, dubbed MARQUIS (Multicenter Medication Reconciliation Quality Improvement Study). Those immersed in med rec know that it’s nonlinear, multilayered, and surprisingly complex, requiring partnerships among diverse providers across many domains of care.

“Medication reconciliation gets right at all the weaknesses of our healthcare system,” says Dr. Schnipper, a hospitalist and director of clinical research for the HM service at Brigham and Women’s Hospital (BWH) and assistant professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, both in Boston. “We have an excellent healthcare system in so many ways, but what we do not do such a good job of is coordination of care across settings, easy transfer of information, and having one person who is responsible for the accuracy of a patient’s health information.”

Dr. Schnipper’s studies attest to the common occurrence of unintentional medical discrepancies, pointing to the need for accurate medication histories, identifying high-risk patients for intensive interventions, and careful med rec at time of discharge.4

Other factors might come into play, says Ted Tsomides, MD, PhD, an attending physician on the HM service at WakeMed Hospital and assistant professor of medicine at the University of North Carolina’s School of Medicine in Raleigh, N.C. For example, he surmises that a “fatigue factor” sets in for some providers. “After five years of working on any initiative, people get worn out and push it to the back burner, unless they are really incentivized to stay on it,” he says.

List Capture

Medication reconciliation is a multifaceted process, and the first step is to gather the history of medications the patient has been taking. Hospitalist Blake J. Lesselroth, MD, MBI, assistant professor of medicine and medical informatics and director of the Portland Patient Safety Center of Inquiry at the Portland VA Medical Center in Oregon, points out that “the initial exposure to the patient is like a pencil sketch. You start to realize that med rec involves iterative loops of communication between you, the patient, and other knowledge resources (see Figure 1). As you start to pull in more information, you begin to complete your narrative. At the end of hospitalization, you’ve got a vibrant portrait with much more nuance to it. So it can’t be a linear process.”

—Kristine M. Gleason, RPh, clinical quality leader, department of clinical quality and analytics, Northwestern Memorial Hospital, Chicago

The list is dynamic, especially in the ICU setting, says Gleason, where it represents only one point in time.

In a closed system, such as the Veterans Administration or Kaiser Permanente, it’s often easier to establish a patient’s ongoing medications. With an integrated electronic health record (EHR), providers can call up the patient’s list of medications during admittance to the hospital. Verifying those medications remains critical: The health record lists patients’ prescriptions, but that doesn’t always mean they have actually filled or are taking those medications.

At the Kaiser Permanente Southern California site in Santa Clarita, Calif., where hospitalist David W. Wong, MD, works, pharmacists review their medications with patients when they are admitted, provide any needed consultation, then repeat the process at discharge. “So far,” Dr. Wong says, “this has resulted in the best medication reconciliation that we’ve seen.”

Pharmacy Is Key

In 2006, Kenneth Boockvar, MD, of the James J. Peters VA Medical Center in Bronx, N.Y., found in a pre- and post-intervention study that using pharmacists to ferret out and communicate prescribing discrepancies to physicians resulted in lower risk of adverse drug events (ADEs) for patients transferred between the hospital and the nursing home.5 Likewise, Dr. Schnipper and his colleagues found that using pharmacists to conduct medication reviews, counsel patients at discharge, and make follow-up telephone calls to patients was associated with a lower rate of preventable ADEs 30 days after hospital discharge.6

At United Hospital System’s (UHS) Kenosha Medical Center campus in Kenosha, Wis., pharmacists play a key role in generating medication lists for incoming patients. Hospitalist Corey Black, MD, regional medical director for Cogent HMG, says many patients do not recall their medications or the dosages, so UHS utilizes a team approach: If patients come in during evenings or weekends, pharmacists start calling local pharmacies to track down patients’ medication lists. “We also try to have family members bring in any medication containers they can find,” he adds. Due to a Wisconsin state law mandating nursing homes to send medication lists along with patients, generating a list is much easier.

Dr. Tsomides is a physician sponsor of a new med-rec initiative at WakeMed. With a steering committee that includes representatives from stakeholder services (medicine, nursing, pharmacy, administration, etc.), the group plans to hire and train pharmacy techs who will take home medication lists in the ED, lifting that responsibility from physicians’ task lists.

Is IT the Answer?

Would many of the barriers to med rec go away with universal EHR? So far, the literature has not borne out the superiority of using EHR to facilitate better med rec.

Peter Kaboli and colleagues found that the computerized medication record reflected what patients were actually taking for only 5.3% of the 493 VA patients enrolled in a study at the Iowa City VA.7 Kenneth Boockvar and colleagues at the Bronx VA found no difference in the overall incidence of ADEs caused by medication discrepancies between VA patients with an EHR and non-VA patients without an EHR.8 A group of researchers with Partners HealthCare in Boston evaluated a secure, Web-based patient portal to produce more accurate medication lists. The patients using this system had just as many discrepancies between medication lists and self-reporting as those who did not.9

Dr. Lesselroth, who has devised a patient kiosk touch-screen tool for reconciling patients’ medication lists and has faced barriers when implementing said technology, says med rec is much more “organic” than strictly mechanical. “It invokes theories of learning from the cognitive sciences,” he says. “We haven’t actually built tools that help people with their problem representation, with understanding not just how medications reconcile with the prior setting of care, but whether they make clinical sense within the new context of care. That requires a quantum leap in thinking.”

Re-Brand the Message

Drs. Schnipper and Tsomides believe that when The Joint Committee first coined the term “medication reconciliation” and advanced it as a mandate, most providers associated it with a regulatory requirement, and understandably so. Dr. Schnipper says med rec could be improved if providers think about it in the context of accurate orders that translate to greater patient safety. “After all,” he says, “hospitalists are ultimately responsible for the medication orders written for their patients.

“This is not about regulatory requirements,” he continues. “This is about medication safety and transitions of care. You can spend an hour on deciding what dose of Lasix you want to send this patient home on, but if the patient then takes the wrong dose of Lasix because they don’t know what they were supposed to be taking, then all that good medical care is undone.”

The med rec conversation has come full circle, then, as being truly an issue of delivering patient-centered care. (For more on this topic, visit the-hospitalist.org to read “Patient Engagement Critical.”) Rather than focusing on the sometimes-befuddling term of medication reconciliation, providers should see med rec as part of an integrated medication management process that aims to take better care of patients through prevention and treatment, Gleason says.

The med rec issue is about effective communication at every transition of care. And that’s why, says Dr. Schnipper, “Hospitalists should own this process. We don’t have to do the process entirely by ourselves—and shouldn’t. But we are responsible for errors that happen during transitions in care and we should own these initiatives.”

He notes that all six hospitals enrolled in the MARQUIS study have hospitalists at the forefront of their quality-improvement (QI) efforts.

“Medication reconciliation is potentially a high-risk process, and there are no silver bullets” for globally addressing the process, says Dorothea Wild, MD, chief hospitalist at Griffin Hospital, a 160-bed acute care hospital in Derby, Conn.

—Jeffrey Schnipper, MD, MPH, FHM, hospitalist and director of clinical research, Brigham and Women’s Hospital Hospitalist Service, assistant professor of medicine, Harvard Medical School, Boston

Dr. Wild draws a parallel between med rec and blood transfusions. Just as with correct transfusing procedures, “we envision a process where at least two people independently verify what patients’ medications are,” she says. The meds list is started in the ED by nursing staff, is verified by the ED attending, verified again by the admitting team, and triple-checked by the admitting attending. Thus, says Dr. Wild, med rec becomes a shared responsibility.

Dr. Lesselroth wholeheartedly agrees with the approach.

“This is everybody’s job,” he says. “In a larger world view, med rec is all about trying to find a medication regimen that harmonizes with what the patient can do, that improves their probability of adherence, and that also helps us gather information when the patient returns and we re-embrace them in the care model. Theoretically, then, everybody [interfacing with a patient] becomes a clutch player.”

Gretchen Henkel is a freelance writer in California.

References

- Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations. 2005 Hospital Accreditation Standards. JCO website. Available at: http://www.jointcommissioninternational.org/ JCI-Accredited-Organizations/. Accessed Dec. 7, 2011.

- Bell CM, Brener SS, Gunraj N, et al. Association of ICU or hospital admission with unintentional discontinuation of medications for chronic diseases. JAMA. 2011;306:840-847.

- Greenwald JL, Halasyamani L, Green J, et al. Making inpatient medication patient centered, clinically relevant and implementable: a consensus statement on key principles and necessary first steps. J Hosp Med. 2010;5:477-485.

- Pippins JR, Gandhi TK, Hamann C, et al. Classifying and predicting errors of inpatient medication reconciliation. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23:1414-1422.

- Boockvar KS, Carlson HL, Giambanco V, et al. Medication reconciliation for reducing drug-discrepancy adverse events. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother. 2006;4:236-243.

- Schnipper JL, Kirwin JL, Cotugno MC, et al. Role of pharmacist counseling in preventing adverse drug events after hospitalization. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:565-571.

- Kaboli PJ, McClimon JB, Hoth AB, et al. Assessing the accuracy of computerized medication histories. Am J Manag Care. 2004;10(11 Pt 2):872-877.

- Boockvar KS, Livote EE, Goldstein N, et al. Electronic health records and adverse drug events after patient transfer. Qual Saf Health Care. 2010;5:Epub(Aug 19).

- Staroselsky M, Volk LA, Tsurikova R, et al. An effort to improve electronic health record medication list accuracy between visits: patients’ and physicians’ responses. Int J Med Inform. 2008;77:153-160.

- Gleason KM, McDaniel MR, Feinglass J, et al. Results of the Medications at Transitions and Clinical Handoffs (MATCH) study: an analysis of medication reconciliation errors and risk factors at hospital admission. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25:441-447.

Pharmacist Kristine M. Gleason, RPh, got the chance to personally test her ability to help ED providers with medication reconciliation—known by most in healthcare as “med rec”—when she broke her leg a couple of years ago. No problem, she thought: “I’ve been involved in med-rec efforts for eight-plus years.”

But when asked to provide her current medications, Gleason, who is the clinical quality leader in the department of clinical quality and analytics at Northwestern Memorial Hospital in Chicago, says she was in pain and overwhelmed. “I couldn’t even remember my children’s names, let alone the names and dosages of my aspirin and my thyroid medication,” she says. Moreover, she didn’t carry a list in her wallet because “I’m a pharmacist and I do med rec,” she says.

Gleason’s experience highlights why, six years after The Joint Commission introduced medication reconciliation as National Patient Safety Goal (NPSG) No. 8, hospitals and providers still struggle with the process.1 As a younger patient, Gleason took few medications. But for the majority of elderly inpatients with comorbid conditions, just establishing the patient’s medication list can bring the whole process to a halt; without that foundational list, reconciling other medications becomes problematic.

Although the commission has taken the goals under review and has, since July 1, required compliance with the revised NPSG 03.06.01 (see “Additional Resources,”), hospitalization-associated adverse drug events continue to mount. A recent Canadian study caused a ripple this summer with its findings that patients discharged from acute-care hospitals were at higher risk for unintentional discontinuation of their medications prescribed for chronic diseases than control groups, and those who had an ICU stay are at even higher risk.2

There’s been no shortage of med-rec initiatives in recent years. Medication reconciliation was at the top of the list for ways to prevent errors when the Institute for Healthcare Improvement launched its “5 Million Lives Campaign” in December 2006. SHM weighed in on the issue in 2010 with a consensus statement on key principles and necessary first steps in med rec.3

“This isn’t a new problem,” Gleason says. “Med rec has become more heightened because we have many more medications and complex therapies, more care providers, more specialists—more players, if you will.”

The March launch of the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program, part of the Centers for Medicaid & Medicare Services’ (CMS) Inpatient Prospective Payment System, will again shine the spotlight on med rec’s role in the prevention of 30-day readmissions. The Hospitalist talked with researchers, pharmacists, and hospitalists about the reasons behind medication discrepancies, and their strategies for addressing mismatches.

Why So Difficult?

The goal of medication reconciliation is to generate and maintain an accurate and coherent record of patients’ medications across all transitions of care, which sounds straightforward enough. But the process involves much more than just checking items off a list, says Jeffrey Schnipper, MD, MPH, FHM, currently the principal investigator for the $1.5 million study funded by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) to research and implement best practices in med rec, dubbed MARQUIS (Multicenter Medication Reconciliation Quality Improvement Study). Those immersed in med rec know that it’s nonlinear, multilayered, and surprisingly complex, requiring partnerships among diverse providers across many domains of care.

“Medication reconciliation gets right at all the weaknesses of our healthcare system,” says Dr. Schnipper, a hospitalist and director of clinical research for the HM service at Brigham and Women’s Hospital (BWH) and assistant professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, both in Boston. “We have an excellent healthcare system in so many ways, but what we do not do such a good job of is coordination of care across settings, easy transfer of information, and having one person who is responsible for the accuracy of a patient’s health information.”

Dr. Schnipper’s studies attest to the common occurrence of unintentional medical discrepancies, pointing to the need for accurate medication histories, identifying high-risk patients for intensive interventions, and careful med rec at time of discharge.4

Other factors might come into play, says Ted Tsomides, MD, PhD, an attending physician on the HM service at WakeMed Hospital and assistant professor of medicine at the University of North Carolina’s School of Medicine in Raleigh, N.C. For example, he surmises that a “fatigue factor” sets in for some providers. “After five years of working on any initiative, people get worn out and push it to the back burner, unless they are really incentivized to stay on it,” he says.

List Capture

Medication reconciliation is a multifaceted process, and the first step is to gather the history of medications the patient has been taking. Hospitalist Blake J. Lesselroth, MD, MBI, assistant professor of medicine and medical informatics and director of the Portland Patient Safety Center of Inquiry at the Portland VA Medical Center in Oregon, points out that “the initial exposure to the patient is like a pencil sketch. You start to realize that med rec involves iterative loops of communication between you, the patient, and other knowledge resources (see Figure 1). As you start to pull in more information, you begin to complete your narrative. At the end of hospitalization, you’ve got a vibrant portrait with much more nuance to it. So it can’t be a linear process.”

—Kristine M. Gleason, RPh, clinical quality leader, department of clinical quality and analytics, Northwestern Memorial Hospital, Chicago

The list is dynamic, especially in the ICU setting, says Gleason, where it represents only one point in time.

In a closed system, such as the Veterans Administration or Kaiser Permanente, it’s often easier to establish a patient’s ongoing medications. With an integrated electronic health record (EHR), providers can call up the patient’s list of medications during admittance to the hospital. Verifying those medications remains critical: The health record lists patients’ prescriptions, but that doesn’t always mean they have actually filled or are taking those medications.

At the Kaiser Permanente Southern California site in Santa Clarita, Calif., where hospitalist David W. Wong, MD, works, pharmacists review their medications with patients when they are admitted, provide any needed consultation, then repeat the process at discharge. “So far,” Dr. Wong says, “this has resulted in the best medication reconciliation that we’ve seen.”

Pharmacy Is Key

In 2006, Kenneth Boockvar, MD, of the James J. Peters VA Medical Center in Bronx, N.Y., found in a pre- and post-intervention study that using pharmacists to ferret out and communicate prescribing discrepancies to physicians resulted in lower risk of adverse drug events (ADEs) for patients transferred between the hospital and the nursing home.5 Likewise, Dr. Schnipper and his colleagues found that using pharmacists to conduct medication reviews, counsel patients at discharge, and make follow-up telephone calls to patients was associated with a lower rate of preventable ADEs 30 days after hospital discharge.6

At United Hospital System’s (UHS) Kenosha Medical Center campus in Kenosha, Wis., pharmacists play a key role in generating medication lists for incoming patients. Hospitalist Corey Black, MD, regional medical director for Cogent HMG, says many patients do not recall their medications or the dosages, so UHS utilizes a team approach: If patients come in during evenings or weekends, pharmacists start calling local pharmacies to track down patients’ medication lists. “We also try to have family members bring in any medication containers they can find,” he adds. Due to a Wisconsin state law mandating nursing homes to send medication lists along with patients, generating a list is much easier.

Dr. Tsomides is a physician sponsor of a new med-rec initiative at WakeMed. With a steering committee that includes representatives from stakeholder services (medicine, nursing, pharmacy, administration, etc.), the group plans to hire and train pharmacy techs who will take home medication lists in the ED, lifting that responsibility from physicians’ task lists.

Is IT the Answer?

Would many of the barriers to med rec go away with universal EHR? So far, the literature has not borne out the superiority of using EHR to facilitate better med rec.

Peter Kaboli and colleagues found that the computerized medication record reflected what patients were actually taking for only 5.3% of the 493 VA patients enrolled in a study at the Iowa City VA.7 Kenneth Boockvar and colleagues at the Bronx VA found no difference in the overall incidence of ADEs caused by medication discrepancies between VA patients with an EHR and non-VA patients without an EHR.8 A group of researchers with Partners HealthCare in Boston evaluated a secure, Web-based patient portal to produce more accurate medication lists. The patients using this system had just as many discrepancies between medication lists and self-reporting as those who did not.9

Dr. Lesselroth, who has devised a patient kiosk touch-screen tool for reconciling patients’ medication lists and has faced barriers when implementing said technology, says med rec is much more “organic” than strictly mechanical. “It invokes theories of learning from the cognitive sciences,” he says. “We haven’t actually built tools that help people with their problem representation, with understanding not just how medications reconcile with the prior setting of care, but whether they make clinical sense within the new context of care. That requires a quantum leap in thinking.”

Re-Brand the Message

Drs. Schnipper and Tsomides believe that when The Joint Committee first coined the term “medication reconciliation” and advanced it as a mandate, most providers associated it with a regulatory requirement, and understandably so. Dr. Schnipper says med rec could be improved if providers think about it in the context of accurate orders that translate to greater patient safety. “After all,” he says, “hospitalists are ultimately responsible for the medication orders written for their patients.

“This is not about regulatory requirements,” he continues. “This is about medication safety and transitions of care. You can spend an hour on deciding what dose of Lasix you want to send this patient home on, but if the patient then takes the wrong dose of Lasix because they don’t know what they were supposed to be taking, then all that good medical care is undone.”

The med rec conversation has come full circle, then, as being truly an issue of delivering patient-centered care. (For more on this topic, visit the-hospitalist.org to read “Patient Engagement Critical.”) Rather than focusing on the sometimes-befuddling term of medication reconciliation, providers should see med rec as part of an integrated medication management process that aims to take better care of patients through prevention and treatment, Gleason says.

The med rec issue is about effective communication at every transition of care. And that’s why, says Dr. Schnipper, “Hospitalists should own this process. We don’t have to do the process entirely by ourselves—and shouldn’t. But we are responsible for errors that happen during transitions in care and we should own these initiatives.”

He notes that all six hospitals enrolled in the MARQUIS study have hospitalists at the forefront of their quality-improvement (QI) efforts.

“Medication reconciliation is potentially a high-risk process, and there are no silver bullets” for globally addressing the process, says Dorothea Wild, MD, chief hospitalist at Griffin Hospital, a 160-bed acute care hospital in Derby, Conn.

—Jeffrey Schnipper, MD, MPH, FHM, hospitalist and director of clinical research, Brigham and Women’s Hospital Hospitalist Service, assistant professor of medicine, Harvard Medical School, Boston

Dr. Wild draws a parallel between med rec and blood transfusions. Just as with correct transfusing procedures, “we envision a process where at least two people independently verify what patients’ medications are,” she says. The meds list is started in the ED by nursing staff, is verified by the ED attending, verified again by the admitting team, and triple-checked by the admitting attending. Thus, says Dr. Wild, med rec becomes a shared responsibility.

Dr. Lesselroth wholeheartedly agrees with the approach.

“This is everybody’s job,” he says. “In a larger world view, med rec is all about trying to find a medication regimen that harmonizes with what the patient can do, that improves their probability of adherence, and that also helps us gather information when the patient returns and we re-embrace them in the care model. Theoretically, then, everybody [interfacing with a patient] becomes a clutch player.”

Gretchen Henkel is a freelance writer in California.

References

- Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations. 2005 Hospital Accreditation Standards. JCO website. Available at: http://www.jointcommissioninternational.org/ JCI-Accredited-Organizations/. Accessed Dec. 7, 2011.

- Bell CM, Brener SS, Gunraj N, et al. Association of ICU or hospital admission with unintentional discontinuation of medications for chronic diseases. JAMA. 2011;306:840-847.

- Greenwald JL, Halasyamani L, Green J, et al. Making inpatient medication patient centered, clinically relevant and implementable: a consensus statement on key principles and necessary first steps. J Hosp Med. 2010;5:477-485.

- Pippins JR, Gandhi TK, Hamann C, et al. Classifying and predicting errors of inpatient medication reconciliation. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23:1414-1422.

- Boockvar KS, Carlson HL, Giambanco V, et al. Medication reconciliation for reducing drug-discrepancy adverse events. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother. 2006;4:236-243.

- Schnipper JL, Kirwin JL, Cotugno MC, et al. Role of pharmacist counseling in preventing adverse drug events after hospitalization. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:565-571.

- Kaboli PJ, McClimon JB, Hoth AB, et al. Assessing the accuracy of computerized medication histories. Am J Manag Care. 2004;10(11 Pt 2):872-877.

- Boockvar KS, Livote EE, Goldstein N, et al. Electronic health records and adverse drug events after patient transfer. Qual Saf Health Care. 2010;5:Epub(Aug 19).

- Staroselsky M, Volk LA, Tsurikova R, et al. An effort to improve electronic health record medication list accuracy between visits: patients’ and physicians’ responses. Int J Med Inform. 2008;77:153-160.

- Gleason KM, McDaniel MR, Feinglass J, et al. Results of the Medications at Transitions and Clinical Handoffs (MATCH) study: an analysis of medication reconciliation errors and risk factors at hospital admission. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25:441-447.

AMA Policy Opposes Switch to ICD-10

On Nov. 10, the American Medical Association’s House of Delegates approved a policy opposing implementation of the International Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 10th Revision (ICD-10-CM) at a policy meeting in New Orleans. Following the vote, Robert M. Wah, MD, AMA board chair, stated, “The AMA will work vigorously to stop implementation of ICD-10, which will create a significant burden on the practice of medicine with no direct benefit to individual patients’ care.”

Organizations tied to hospitals, however, are fully supportive of the switch.

“We strongly support ICD-10 and the enhancements it will bring to the care that’s provided in hospitals,” says Don May, the American Hospital Association’s (AHA) vice president for policy. “The current coding system has really run its course in its ability to keep up with modern medicine.”

SHM has taken a “neutral” stance on this issue, for the time being, says SHM’s AMA delegate Bradley E. Flansbaum, DO, MPH, SFHM, director of hospitalist services at Lenox Hill Hospital in New York City. “But [SHM is] cautiously optimistic as the inpatient ecosystem evolves, hopefully, for the better.”

History of Opposition

In 2003, the AMA wrote to the National Committee on Vital and Health Statistics regarding plans to adopt ICD-10. The 55 signees of the letter (including the American College of Surgeons and other specialty societies) urged the committee to “confine your recommendation [to HHS] to the uses of ICD-10-PCS [the procedural codes portion] as a coding system for inpatient hospital services.” Another letter in 2006 to Bill Frist, then the U.S. Senate majority leader, expressed concern over a “rapid transition” from ICD-9 to ICD-10.