User login

The Current State of Postgraduate Dermatology Training Programs for Advanced Practice Providers

The Current State of Postgraduate Dermatology Training Programs for Advanced Practice Providers

Nurse practitioners (NPs) and physician assistants (PAs) often help provide dermatologic care but lack the same mandatory specialized postgraduate training required of board-certified dermatologists (BCDs), which includes at least 3 years of dermatology-focused education in an accredited residency program in addition to an intern year of general medicine, pediatrics, or surgery. Dermatology residency is followed by a certification examination administered by the American Board of Dermatology (ABD) or the American Osteopathic Board of Dermatology, leading to board certification. Some physicians choose to do a fellowship, which typically involves an additional 1 to 2 years of postresidency subspeciality training.

Optional postgraduate dermatology training programs for advanced practice providers (APPs) have been offered by some academic institutions and private practice groups since at least 2003, including Lahey Hospital and Medical Center (Burlington, Massachusetts) as well as the University of Rochester Medical Center (Rochester, New York). Despite a lack of accreditation or standardization, the programs can be beneficial for NPs and PAs to expand their dermatologic knowledge and skills and help bridge the care gap within the specialty. Didactics often are conducted in parallel with the educational activities of the parent institution’s traditional dermatology residency program (eg, lectures, grand rounds). While these programs often are managed by practicing dermatology NPs and PAs, dermatologists also may be involved in their education with didactic instruction, curriculum development, and clinical preceptorship.

In this cross-sectional study, we identified and evaluated 10 postgraduate dermatology training programs for APPs across the United States. With the growing number of NPs and PAs in the dermatology workforce—both in academic and private practice—it is important for BCDs to be aware of the differences in the dermatology training received in order to ensure safe and effective care is provided through supervisory or collaborative roles (depending on state independent practice laws for APPs and to be aware of the implications these programs may have on the field of dermatology.

Methods

To identify postgraduate dermatology training programs for APPs in the United States, we conducted a cross-sectional study using data obtained via a Google search of various combinations of the following terms: nurse practitioner, NP, physician assistant, PA, advance practice provider, APP, dermatology, postgraduate training, residency, and fellowship. We excluded postgraduate dermatology training programs for APPs that required tuition and did not provide a stipend, as well as programs that lacked the formal structure and credibility needed to qualify as legitimate postgraduate training. Many of the excluded programs operate in a manner that raises ethical concerns, offering pay-to-play opportunities under the guise of education. Information collected on each program included the program name, location, parent institution, program length, class size, curriculum, and any associated salary and benefits.

Results

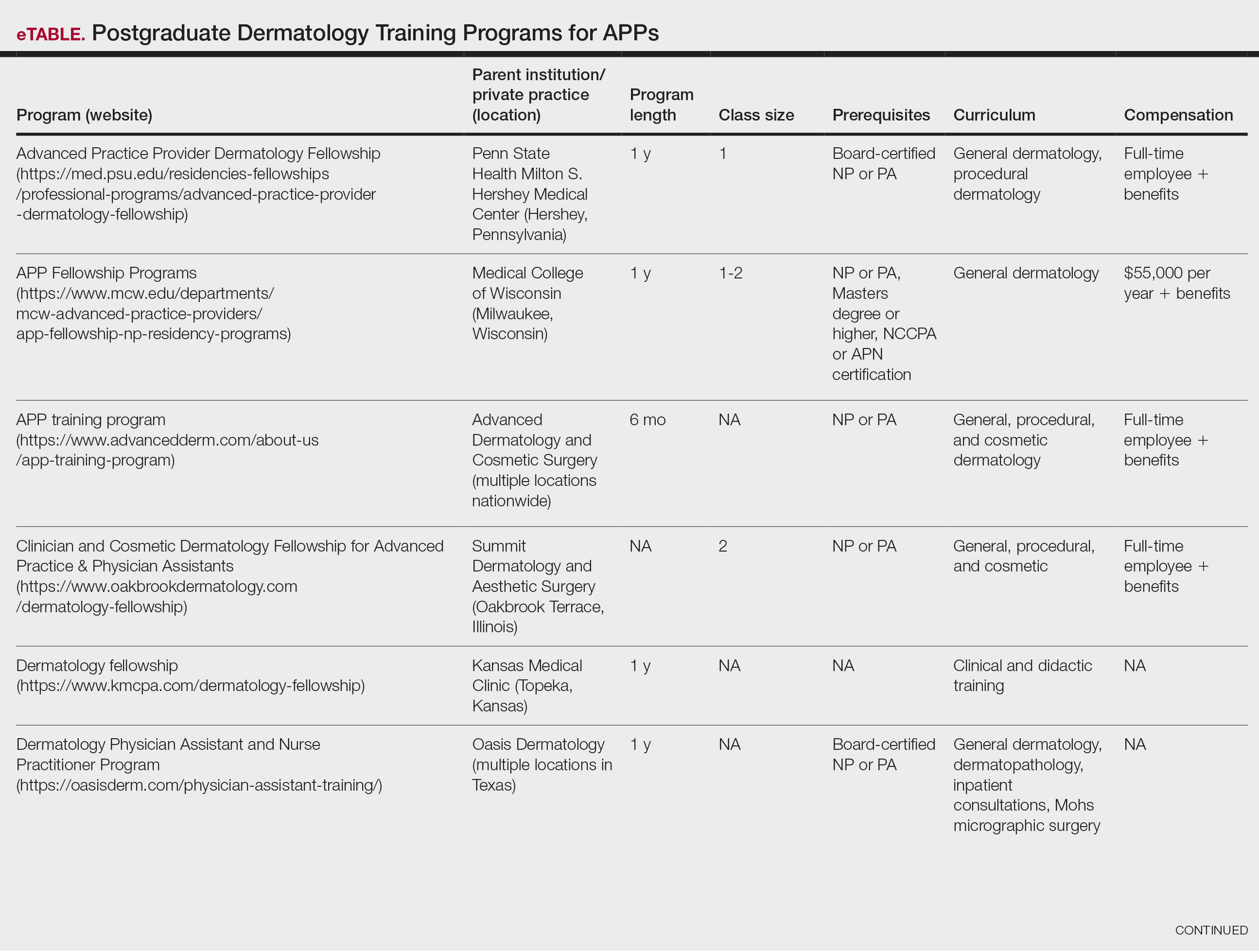

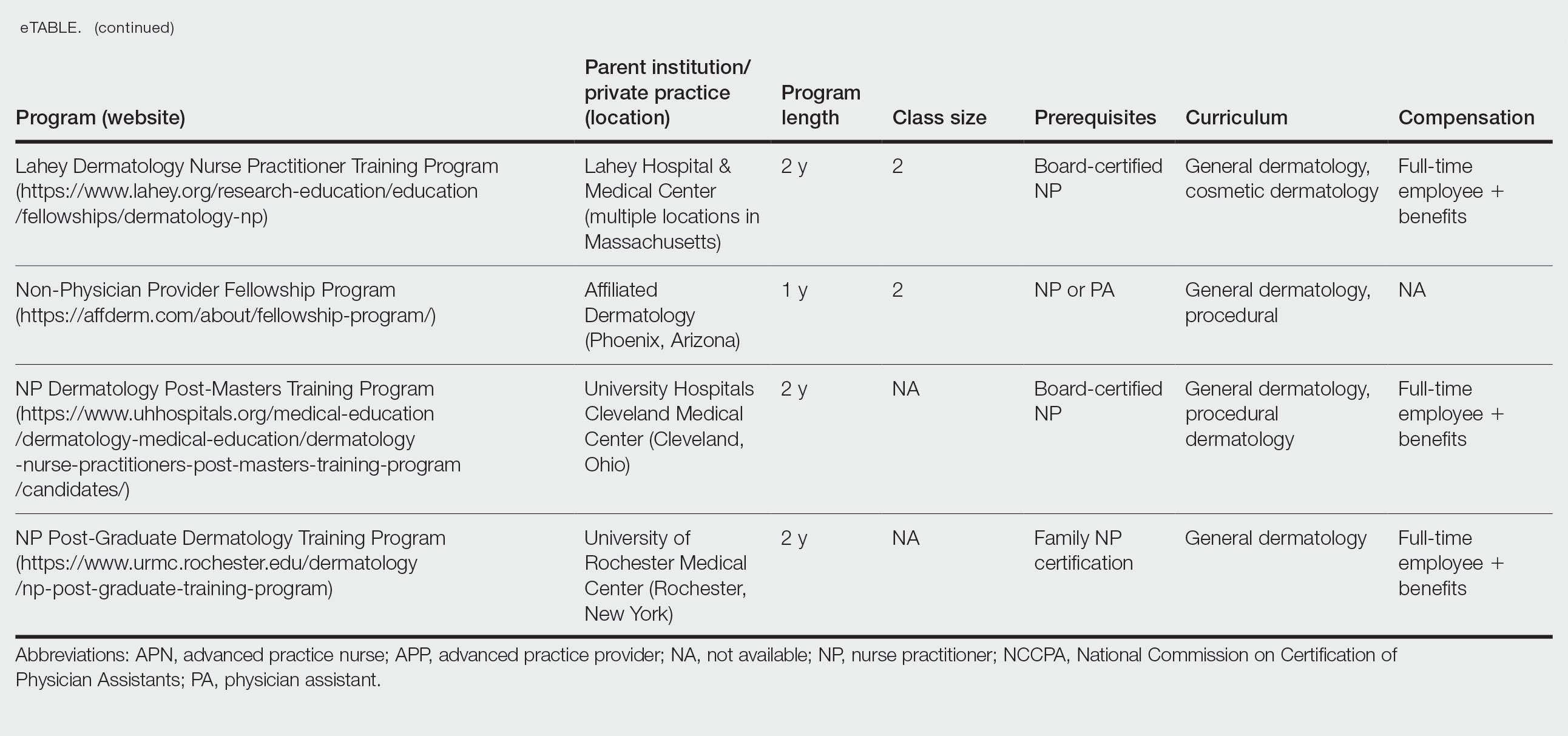

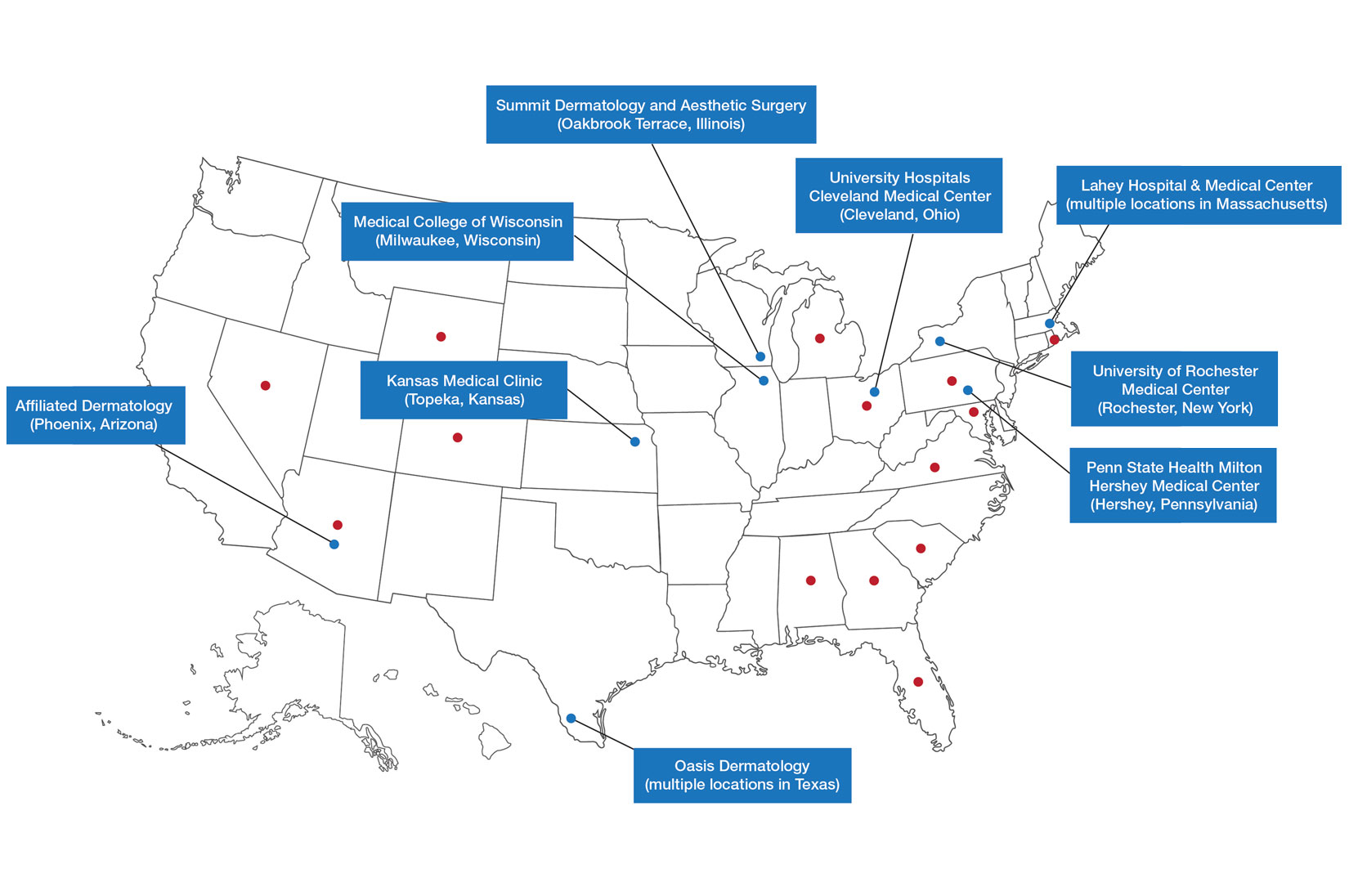

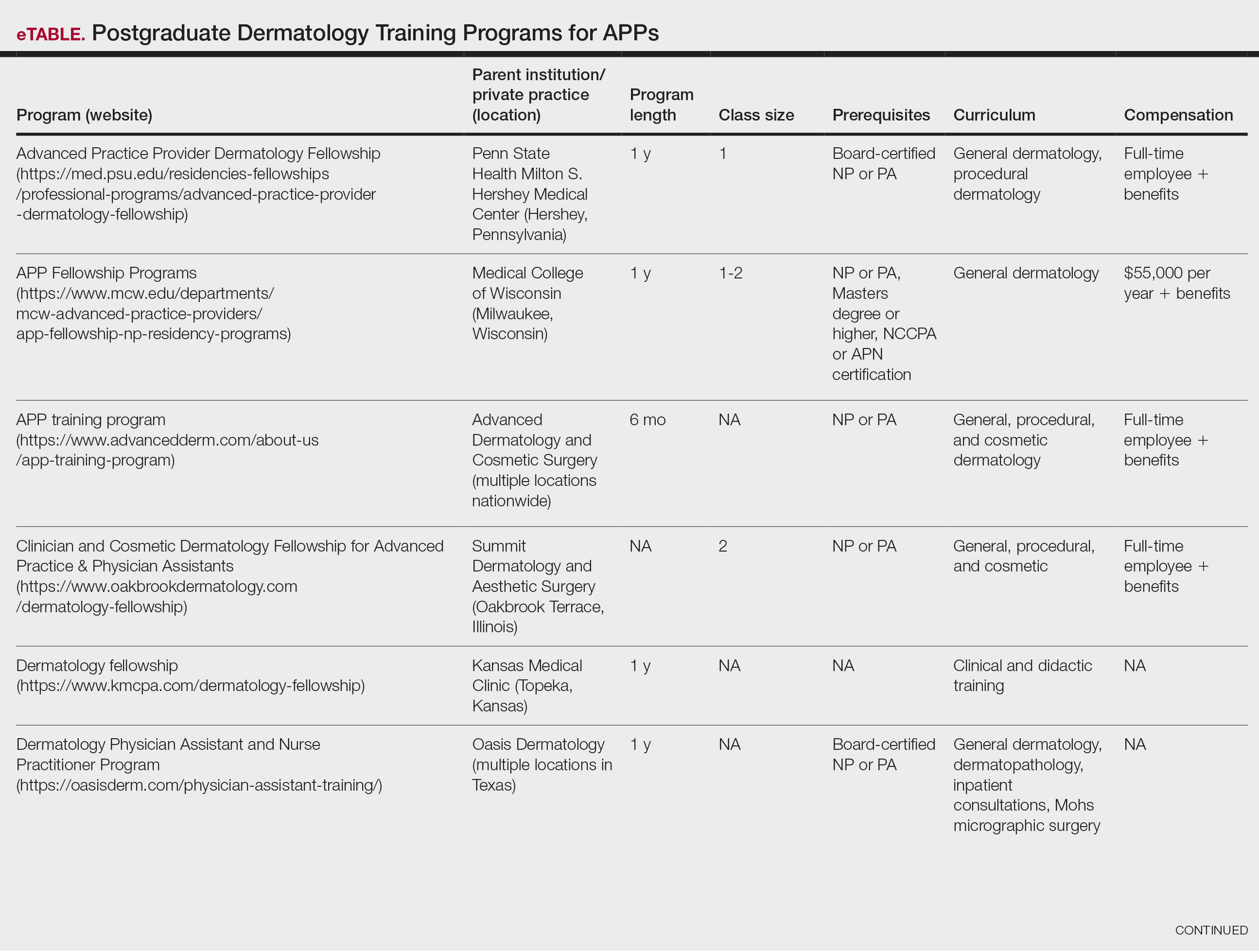

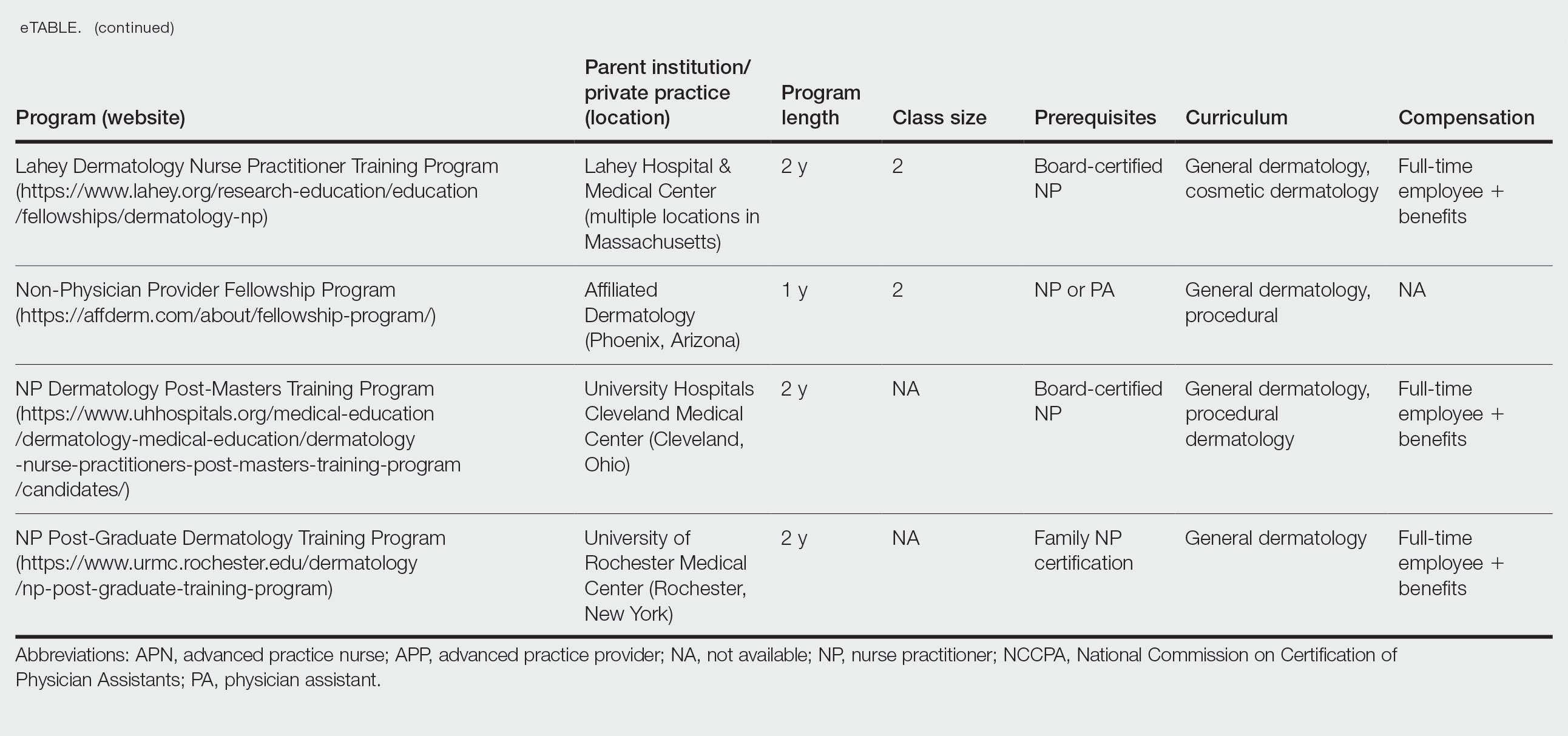

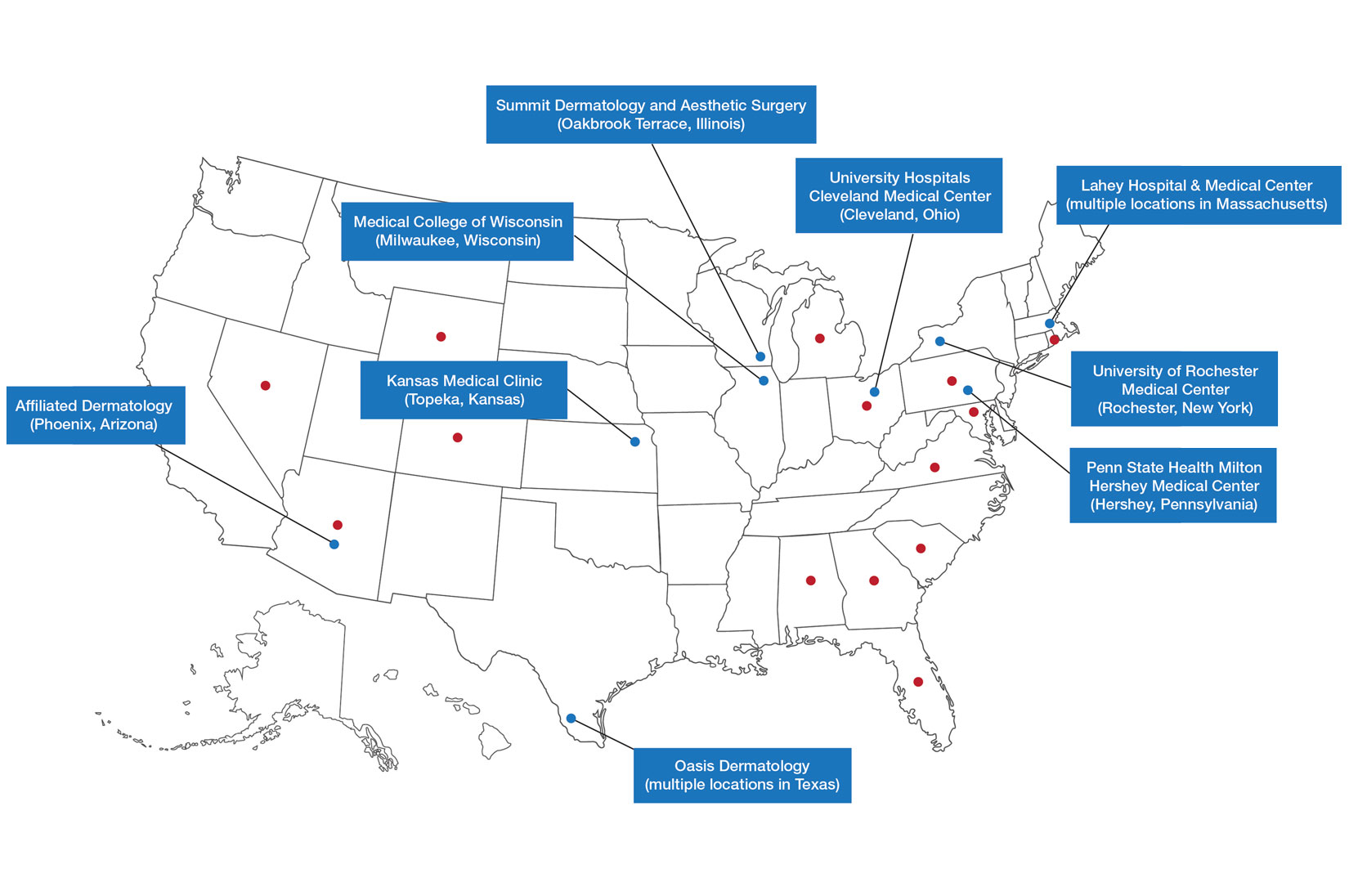

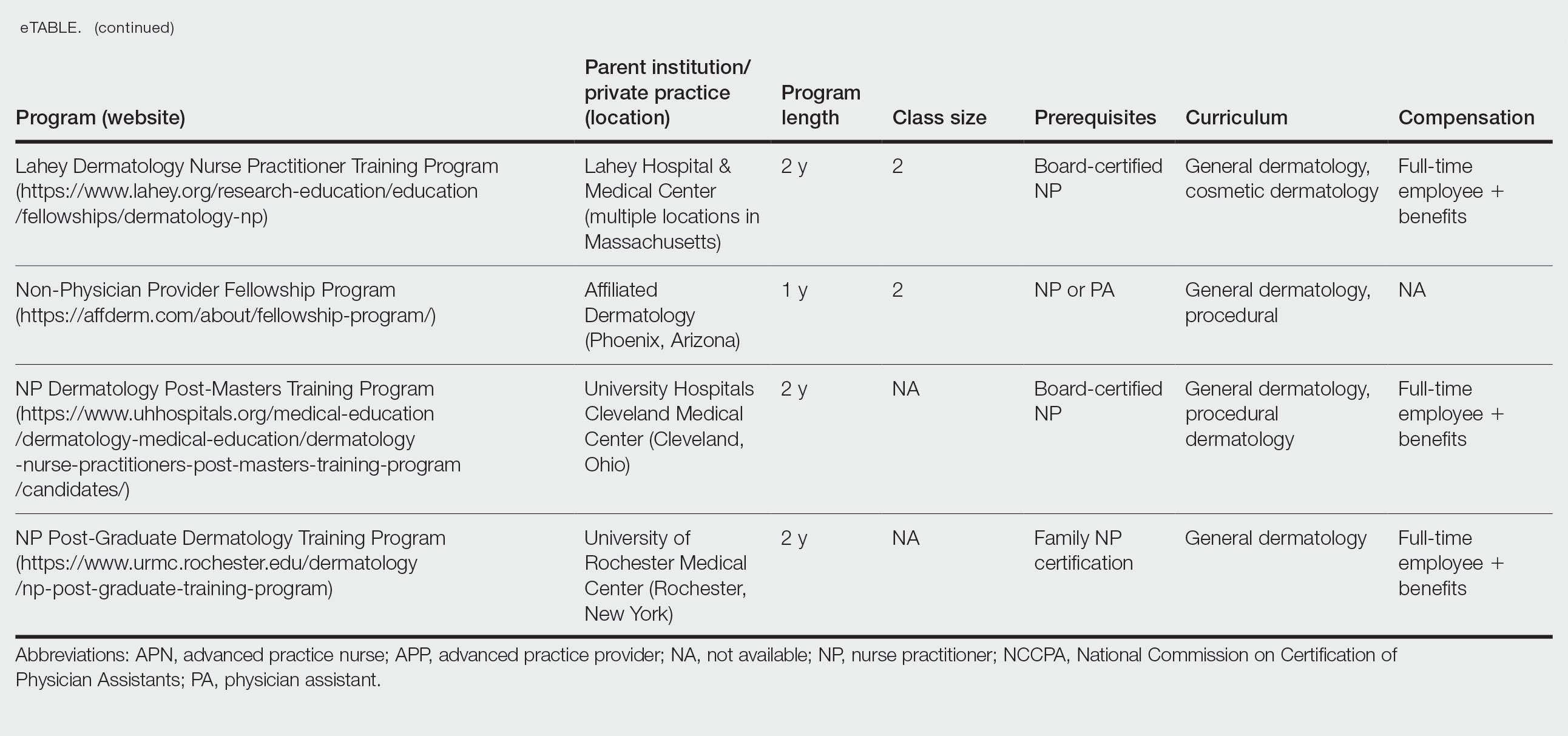

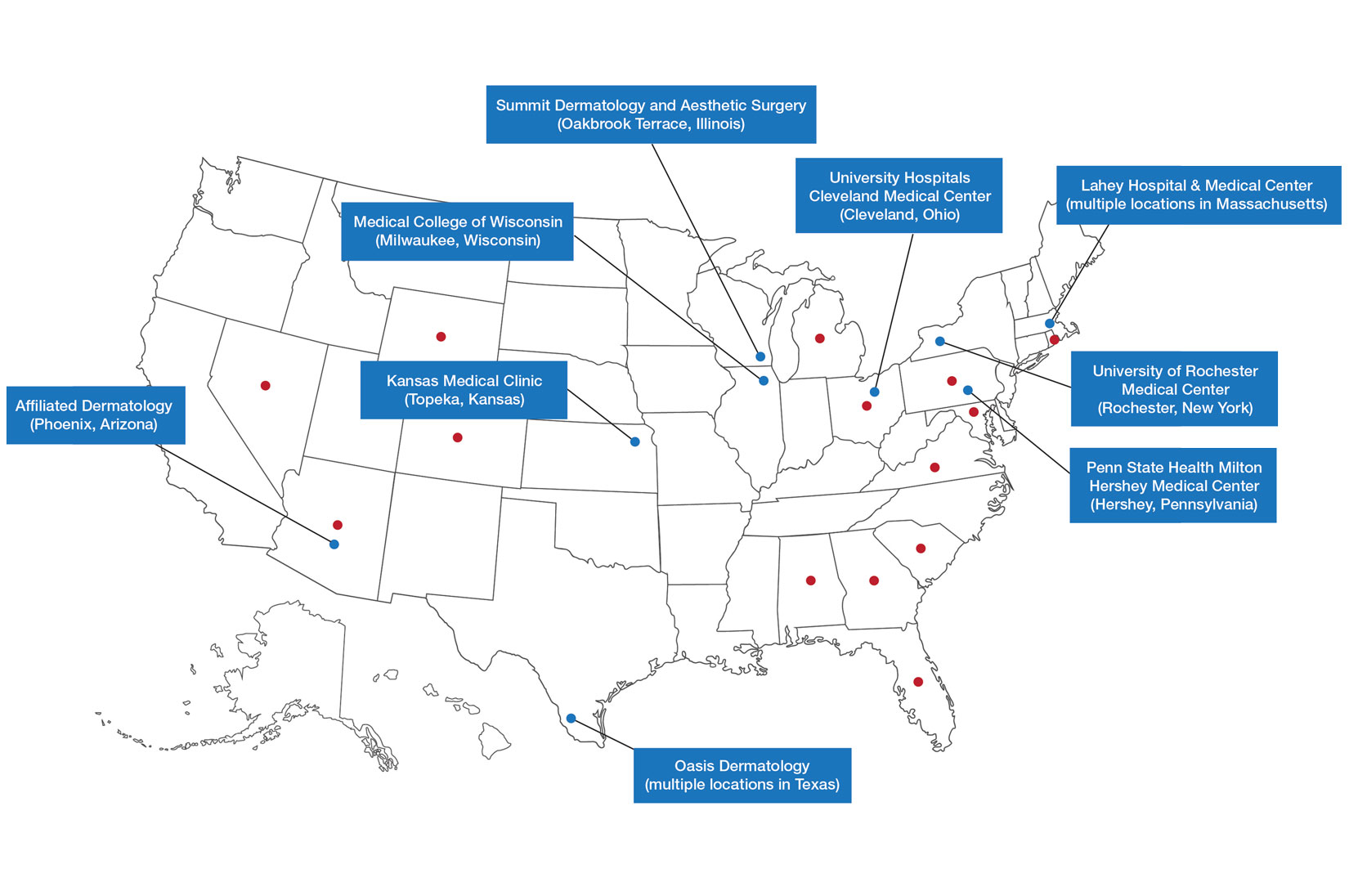

Ten academic and private practice organizations across the United States that offer postgraduate dermatologic training programs for APPs were identified (eTable). Four (40%) programs were advertised as fellowships. Six (60%) of the programs were offered at academic medical centers, and 4 (40%) were offered by private practices. Most programs were located east of the Mississippi River, and many institutions offered instruction at 1 or more locations within the same state (eFigure). The Advanced Dermatology and Cosmetic Surgery private practice group offered training opportunities in multiple states.

Six programs required APPs to become board-certified NPs or PAs prior to enrolling. Most programs enrolled both NPs and PAs, while some only enrolled NPs (eTable). Only 1 (10%) program required NPs to be board certified as a family NP, while another (10%) recommended that applicants have experience in urgent care, emergency medicine, or trauma medicine. Lahey Hospital & Medical Center required experience as an NP in a general setting for 1 to 2 years prior to applying. No program required prior experience in the field of dermatology.

Program length varied from 6 to 24 months, and cohort size typically was limited to 1 to 2 providers (eTable). Although the exact numbers could not be ascertained, most curricula focused on medical dermatology, including clinical and didactic components, but many offered electives such as cosmetic and procedural dermatology. Two institutions (20%) required independent research. Work typically was limited to 40 hours per week, and most paid a full-time employee salary and provided benefits such as health insurance, retirement, and paid leave (eTable). Kansas Medical Clinic (Topeka, Kansas) required at least 3 years of employment in an underserved community following program completion. The Oasis Dermatology private practice group in Texas required a 1-year teaching commitment after program completion. The Advanced Dermatology and Cosmetic Surgery group offered a full-time position upon program completion.

Comment

There is a large difference in the total number of training and credentialing hours when comparing graduate school training and postgraduate credentialing of medical and osteopathic physicians compared with APPs. A new graduate physician has at least twice as many clinical hours as a PA and 10 times as many clinical hours as an NP prior to starting residency. Physicians also typically complete at least 6 times the number of hours of certification examinations compared to NPs and PAs.1

Nurse practitioner students typically complete the 500 hours of prelicensure clinical training required for NP school in 2 to 4 years.2,3 The amount of time required for completion is dependent on the degree and experience of the student upon program entry (eg, bachelor of science in nursing vs master of science in nursing as a terminal degree). Physician assistant students are required to complete 2000 prelicensure clinical hours, and most PA programs are 3 years in duration.4 Many NP and PA programs require some degree of clinical experience prior to beginning graduate education.5

When comparing prelicensure examinations, questions assessing dermatologic knowledge comprise approximately 6% to 10% of the total questions on the United States Medical Licensing Examination Steps 1 and 2.6 The Comprehensive Osteopathic Medical Licensing Examination of the United States Level 1 and Level 2-Cognitive Evaluation both have at least 5% of questions dedicated to dermatology.7 Approximately 5% of the questions on the Physician Assistant National Certifying Examination are dedicated to dermatology.8 The dermatology content on either of the NP certification examinations is unclear.2,3 In the states of California, Indiana, and New York, national certification through the American Association of Nurse Practitioners or American Nurses Credentialing Center is not required for NPs to practice in their respective states.9

Regarding dermatologic board certification, a new graduate NP may obtain certification from the

Many of the programs we evaluated integrate APP trainees into resident education, allowing participation in equivalent didactic curricula, clinical rotations, and departmental academic activities. The salary and benefits associated with these programs are somewhat like those of resident physicians.15,16 While most tuition-based programs were excluded from our study due to their lack of credibility and alignment with our study criteria, we identified 2 specific programs that stood out as credible despite requiring students to pay tuition. These programs demonstrated a structured and rigorous curriculum with a clear focus on comprehensive dermatologic training, meeting our standards for inclusion. These programs offer dermatologic training for graduates of NP and PA programs at a cost to the student.15,16 The program at the Florida Atlantic University, Boca Raton, is largely online,15 and the program at the University of Miami, Florida, offers no direct clinical contact.16 These programs illustrate the variety of postgraduate dermatology curricula available nationally in comparison to resident salaries; however, they were not included in our formal analysis because they do not provide structured, in-person clinical training consistent with our inclusion criteria. Neither of these programs would enable participants to qualify for credentialing with the Dermatology Nurse Practitioner Certification Board after completion. While this study identified postgraduate training programs for APPs in dermatology advertised online, it is possible some were omitted or not advertised online.

While many of the postgraduate programs we evaluated provide unique educational opportunities for APPs, it is unknown if graduating providers are equipped to handle the care of patients with complex dermatologic needs. Regardless, the increased utilization of APPs by BCDs has been well documented over the past 2 decades.17-20 It has been suggested that a higher ratio of APPs to dermatologists can decrease the time it takes for a patient to be seen in a clinic.21-23 However, investigators have expressed concerns that APPs lack standardized surgical training and clinical hour requirements in the field of dermatology.24 Despite these concerns, Medicare claims data show that APPs are performing advanced surgical and cosmetic procedures at increasing rates.17,18 Other authors have questioned the cost-effectiveness of APPs, as multiple studies have shown that the number of biopsies needed to diagnose 1 case of skin cancer is higher for midlevel providers than for dermatologists.25-27

Conclusion

With the anticipated expansion of private equity in dermatology and the growth of our Medicare-eligible population, we are likely to see increased utilization of APPs to address the shortage of BCDs.28,29 Understanding the prelicensure and postlicensure clinical training requirements, examination hours, and extent of dermatology-focused education among APPs and BCDs can help dermatologists collaborate more effectively and ensure safe, high-quality patient care. Standardizing, improving, and providing high-quality education and promoting lifelong learning in the field of dermatology should be celebrated, and dermatologists are the skin experts best equipped to lead dermatologic education forward.

- Robeznieks A. Training gaps between physicians, nonphysicians are significant. American Medical Association. February 17, 2025. Accessed October 23, 2025. https://www.ama-assn.org/practice-management/scope-practice/training-gaps-between-physicians-nonphysicians-are-significant

- American Nurses Credentialing Center. Test content outline. Accessed October 6, 2025. https://www.nursingworld.org/globalassets/08282024-exam-24-npd-tco-website.pdf

- American Academy of Nurse Practitioners National Certification Board. AANPCB Family Nurse Practitioner Adult-Gerontology Primary Care Nurse Practitioner Psychiatric Mental Health Pratitioner: FNP, AGNP & PMHNP Certification Certification Handbook. American Academy of Nurse Practitioners Certification Board; 2023. Accessed October 6, 2025. https://www.aanpcert.org/resource/documents/AGNP%20FNP%20Candidate%20Handbook.pdf

- Society of Dermatology Physician Associates. SDPA Diplomate Fellowship. Accessed October 6, 2025. https://learning.dermpa.orgdiplomate-fellowship

- American Academy of Physician Associates. Become a PA. Accessed October 6, 2025. https://www.aapa.org/career-central/become-a-pa/

- United States Medical Licensing Examination. Prepare for your exam. Accessed October 6, 2025. https://www.usmle.org/prepare-your-exam

- National Board of Osteopathic Medical Examiners. Patient presentations related to the integumentary system. Accessed October 6, 2025. https://www.nbome.org/assessments/comlex-usa/comlex-usa-blueprint/d2-clinical-presentations/integumentary-system

- National Commission on Certification of Physician Assistants. PANCE content blueprint. Accessed October 6, 2025. https://prodcmsstoragesa.blob.core.windows.net/uploads/files/PANCEBlueprint.pdf

- American Association of Nurse Practitioners. Practice information by state. Accessed October 6, 2025. https://www.aanp.org/practice/practice-information-by-state

- Dermatology Nurse Practitioner Certification Board. Eligibility. Accessed October 6, 2025. https://www.dnpcb.org/eligibility.php

- National Board of Dermatology Physician Assistants. Certification. Accessed September 3, 2022.

- Society of Dermatology Physician Associates. SDPA statement regarding the ABDPA Board Certification Exam for derm PAs. October 8, 2019. Accessed October 6, 2025. https://www.dermpa.org/news/articles/2019-10/sdpa-statement-regarding-abdpa-board-certification-exam-derm-pas

- American Board of Dermatology. Residents and fellows. Accessed October 6, 2025. https://www.abderm.org/residents-and-fellows

- American Osteopathic Board of Dermatology. Primary certificaiton exam. Accessed October 6, 2025. https://certification.osteopathic.org/dermatology/certification-process/dermatology/written-exams/

- Florida Atlantic University. Christine E. Lynn College of Nursing. Dermatology nurse practitioner certificate program. Accessed October 6, 2025. https://www.fau.edu/nursing/academics/certificates/dermatology-program/

- Dr. Phillip Frost Department of Dermatology and Cutaneous Surgery. Advanced Practitioner Program.

- Coldiron B, Ratnarathorn M. Scope of physician procedures independently billed by mid-level providers in the office setting. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:1153-1159.

- Zhang M, Zippin J, Kaffenberger B. Trends and scope of dermatology procedures billed by advanced practice professionals from 2012 through 2015. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:1040-1044.

- Resneck J Jr, Kimball AB. The dermatology workforce shortage. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:50-54.

- Kimball AB, Resneck JS Jr. The US dermatology workforce: a specialty remains in shortage. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:741-745.

- Creadore A, Desai S, Li SJ, et al. Insurance acceptance, appointment wait time, and dermatologist access across practice types in the US. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:181-188.

- Braun RT, Bond AM, Qian Y, et al. Private equity in dermatology: effect on price, utilization, and spending. Health Aff (Millwood). 2021;40:727-735.

- Skaljic M, Lipoff JB. Association of private equity ownership with increased employment of advanced practice professionals in outpatient dermatology offices. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:1178-1180.

- Jalian HR, Avram MM. Mid-level practitioners in dermatology: a need for further study and oversight. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:1149-1151.

- Sarzynski E, Barry H. Current evidence and controversies: advanced practice providers in healthcare. Am J Manag Care. 2019;25:366-368.

- Nault A, Zhang C, Kim K, et al. Biopsy use in skin cancer diagnosis: comparing dermatology physicians and advanced practice professionals. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:899-902.

- Anderson AM, Matsumoto M, Saul MI, et al. Accuracy of skin cancer diagnosis by physician assistants compared with dermatologists in a large health care system. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:569-573.

- Sung C, Salem S, Oulee A, et al. A systematic review: landscape of private equity in dermatology from past to present. J Drugs Dermatol. 2023 Apr 1;22:404-409. doi: 10.36849/JDD.6892.

- CMS releases National Healthcare Expenditure and enrollment projections through 2031. Health Management Associates. July 13, 2023. Accessed October 23, 2025. https://www.healthmanagement.com/blog/cms-releases-national-healthcare-expenditure-and-enrollment-projections-through-2031/

Nurse practitioners (NPs) and physician assistants (PAs) often help provide dermatologic care but lack the same mandatory specialized postgraduate training required of board-certified dermatologists (BCDs), which includes at least 3 years of dermatology-focused education in an accredited residency program in addition to an intern year of general medicine, pediatrics, or surgery. Dermatology residency is followed by a certification examination administered by the American Board of Dermatology (ABD) or the American Osteopathic Board of Dermatology, leading to board certification. Some physicians choose to do a fellowship, which typically involves an additional 1 to 2 years of postresidency subspeciality training.

Optional postgraduate dermatology training programs for advanced practice providers (APPs) have been offered by some academic institutions and private practice groups since at least 2003, including Lahey Hospital and Medical Center (Burlington, Massachusetts) as well as the University of Rochester Medical Center (Rochester, New York). Despite a lack of accreditation or standardization, the programs can be beneficial for NPs and PAs to expand their dermatologic knowledge and skills and help bridge the care gap within the specialty. Didactics often are conducted in parallel with the educational activities of the parent institution’s traditional dermatology residency program (eg, lectures, grand rounds). While these programs often are managed by practicing dermatology NPs and PAs, dermatologists also may be involved in their education with didactic instruction, curriculum development, and clinical preceptorship.

In this cross-sectional study, we identified and evaluated 10 postgraduate dermatology training programs for APPs across the United States. With the growing number of NPs and PAs in the dermatology workforce—both in academic and private practice—it is important for BCDs to be aware of the differences in the dermatology training received in order to ensure safe and effective care is provided through supervisory or collaborative roles (depending on state independent practice laws for APPs and to be aware of the implications these programs may have on the field of dermatology.

Methods

To identify postgraduate dermatology training programs for APPs in the United States, we conducted a cross-sectional study using data obtained via a Google search of various combinations of the following terms: nurse practitioner, NP, physician assistant, PA, advance practice provider, APP, dermatology, postgraduate training, residency, and fellowship. We excluded postgraduate dermatology training programs for APPs that required tuition and did not provide a stipend, as well as programs that lacked the formal structure and credibility needed to qualify as legitimate postgraduate training. Many of the excluded programs operate in a manner that raises ethical concerns, offering pay-to-play opportunities under the guise of education. Information collected on each program included the program name, location, parent institution, program length, class size, curriculum, and any associated salary and benefits.

Results

Ten academic and private practice organizations across the United States that offer postgraduate dermatologic training programs for APPs were identified (eTable). Four (40%) programs were advertised as fellowships. Six (60%) of the programs were offered at academic medical centers, and 4 (40%) were offered by private practices. Most programs were located east of the Mississippi River, and many institutions offered instruction at 1 or more locations within the same state (eFigure). The Advanced Dermatology and Cosmetic Surgery private practice group offered training opportunities in multiple states.

Six programs required APPs to become board-certified NPs or PAs prior to enrolling. Most programs enrolled both NPs and PAs, while some only enrolled NPs (eTable). Only 1 (10%) program required NPs to be board certified as a family NP, while another (10%) recommended that applicants have experience in urgent care, emergency medicine, or trauma medicine. Lahey Hospital & Medical Center required experience as an NP in a general setting for 1 to 2 years prior to applying. No program required prior experience in the field of dermatology.

Program length varied from 6 to 24 months, and cohort size typically was limited to 1 to 2 providers (eTable). Although the exact numbers could not be ascertained, most curricula focused on medical dermatology, including clinical and didactic components, but many offered electives such as cosmetic and procedural dermatology. Two institutions (20%) required independent research. Work typically was limited to 40 hours per week, and most paid a full-time employee salary and provided benefits such as health insurance, retirement, and paid leave (eTable). Kansas Medical Clinic (Topeka, Kansas) required at least 3 years of employment in an underserved community following program completion. The Oasis Dermatology private practice group in Texas required a 1-year teaching commitment after program completion. The Advanced Dermatology and Cosmetic Surgery group offered a full-time position upon program completion.

Comment

There is a large difference in the total number of training and credentialing hours when comparing graduate school training and postgraduate credentialing of medical and osteopathic physicians compared with APPs. A new graduate physician has at least twice as many clinical hours as a PA and 10 times as many clinical hours as an NP prior to starting residency. Physicians also typically complete at least 6 times the number of hours of certification examinations compared to NPs and PAs.1

Nurse practitioner students typically complete the 500 hours of prelicensure clinical training required for NP school in 2 to 4 years.2,3 The amount of time required for completion is dependent on the degree and experience of the student upon program entry (eg, bachelor of science in nursing vs master of science in nursing as a terminal degree). Physician assistant students are required to complete 2000 prelicensure clinical hours, and most PA programs are 3 years in duration.4 Many NP and PA programs require some degree of clinical experience prior to beginning graduate education.5

When comparing prelicensure examinations, questions assessing dermatologic knowledge comprise approximately 6% to 10% of the total questions on the United States Medical Licensing Examination Steps 1 and 2.6 The Comprehensive Osteopathic Medical Licensing Examination of the United States Level 1 and Level 2-Cognitive Evaluation both have at least 5% of questions dedicated to dermatology.7 Approximately 5% of the questions on the Physician Assistant National Certifying Examination are dedicated to dermatology.8 The dermatology content on either of the NP certification examinations is unclear.2,3 In the states of California, Indiana, and New York, national certification through the American Association of Nurse Practitioners or American Nurses Credentialing Center is not required for NPs to practice in their respective states.9

Regarding dermatologic board certification, a new graduate NP may obtain certification from the

Many of the programs we evaluated integrate APP trainees into resident education, allowing participation in equivalent didactic curricula, clinical rotations, and departmental academic activities. The salary and benefits associated with these programs are somewhat like those of resident physicians.15,16 While most tuition-based programs were excluded from our study due to their lack of credibility and alignment with our study criteria, we identified 2 specific programs that stood out as credible despite requiring students to pay tuition. These programs demonstrated a structured and rigorous curriculum with a clear focus on comprehensive dermatologic training, meeting our standards for inclusion. These programs offer dermatologic training for graduates of NP and PA programs at a cost to the student.15,16 The program at the Florida Atlantic University, Boca Raton, is largely online,15 and the program at the University of Miami, Florida, offers no direct clinical contact.16 These programs illustrate the variety of postgraduate dermatology curricula available nationally in comparison to resident salaries; however, they were not included in our formal analysis because they do not provide structured, in-person clinical training consistent with our inclusion criteria. Neither of these programs would enable participants to qualify for credentialing with the Dermatology Nurse Practitioner Certification Board after completion. While this study identified postgraduate training programs for APPs in dermatology advertised online, it is possible some were omitted or not advertised online.

While many of the postgraduate programs we evaluated provide unique educational opportunities for APPs, it is unknown if graduating providers are equipped to handle the care of patients with complex dermatologic needs. Regardless, the increased utilization of APPs by BCDs has been well documented over the past 2 decades.17-20 It has been suggested that a higher ratio of APPs to dermatologists can decrease the time it takes for a patient to be seen in a clinic.21-23 However, investigators have expressed concerns that APPs lack standardized surgical training and clinical hour requirements in the field of dermatology.24 Despite these concerns, Medicare claims data show that APPs are performing advanced surgical and cosmetic procedures at increasing rates.17,18 Other authors have questioned the cost-effectiveness of APPs, as multiple studies have shown that the number of biopsies needed to diagnose 1 case of skin cancer is higher for midlevel providers than for dermatologists.25-27

Conclusion

With the anticipated expansion of private equity in dermatology and the growth of our Medicare-eligible population, we are likely to see increased utilization of APPs to address the shortage of BCDs.28,29 Understanding the prelicensure and postlicensure clinical training requirements, examination hours, and extent of dermatology-focused education among APPs and BCDs can help dermatologists collaborate more effectively and ensure safe, high-quality patient care. Standardizing, improving, and providing high-quality education and promoting lifelong learning in the field of dermatology should be celebrated, and dermatologists are the skin experts best equipped to lead dermatologic education forward.

Nurse practitioners (NPs) and physician assistants (PAs) often help provide dermatologic care but lack the same mandatory specialized postgraduate training required of board-certified dermatologists (BCDs), which includes at least 3 years of dermatology-focused education in an accredited residency program in addition to an intern year of general medicine, pediatrics, or surgery. Dermatology residency is followed by a certification examination administered by the American Board of Dermatology (ABD) or the American Osteopathic Board of Dermatology, leading to board certification. Some physicians choose to do a fellowship, which typically involves an additional 1 to 2 years of postresidency subspeciality training.

Optional postgraduate dermatology training programs for advanced practice providers (APPs) have been offered by some academic institutions and private practice groups since at least 2003, including Lahey Hospital and Medical Center (Burlington, Massachusetts) as well as the University of Rochester Medical Center (Rochester, New York). Despite a lack of accreditation or standardization, the programs can be beneficial for NPs and PAs to expand their dermatologic knowledge and skills and help bridge the care gap within the specialty. Didactics often are conducted in parallel with the educational activities of the parent institution’s traditional dermatology residency program (eg, lectures, grand rounds). While these programs often are managed by practicing dermatology NPs and PAs, dermatologists also may be involved in their education with didactic instruction, curriculum development, and clinical preceptorship.

In this cross-sectional study, we identified and evaluated 10 postgraduate dermatology training programs for APPs across the United States. With the growing number of NPs and PAs in the dermatology workforce—both in academic and private practice—it is important for BCDs to be aware of the differences in the dermatology training received in order to ensure safe and effective care is provided through supervisory or collaborative roles (depending on state independent practice laws for APPs and to be aware of the implications these programs may have on the field of dermatology.

Methods

To identify postgraduate dermatology training programs for APPs in the United States, we conducted a cross-sectional study using data obtained via a Google search of various combinations of the following terms: nurse practitioner, NP, physician assistant, PA, advance practice provider, APP, dermatology, postgraduate training, residency, and fellowship. We excluded postgraduate dermatology training programs for APPs that required tuition and did not provide a stipend, as well as programs that lacked the formal structure and credibility needed to qualify as legitimate postgraduate training. Many of the excluded programs operate in a manner that raises ethical concerns, offering pay-to-play opportunities under the guise of education. Information collected on each program included the program name, location, parent institution, program length, class size, curriculum, and any associated salary and benefits.

Results

Ten academic and private practice organizations across the United States that offer postgraduate dermatologic training programs for APPs were identified (eTable). Four (40%) programs were advertised as fellowships. Six (60%) of the programs were offered at academic medical centers, and 4 (40%) were offered by private practices. Most programs were located east of the Mississippi River, and many institutions offered instruction at 1 or more locations within the same state (eFigure). The Advanced Dermatology and Cosmetic Surgery private practice group offered training opportunities in multiple states.

Six programs required APPs to become board-certified NPs or PAs prior to enrolling. Most programs enrolled both NPs and PAs, while some only enrolled NPs (eTable). Only 1 (10%) program required NPs to be board certified as a family NP, while another (10%) recommended that applicants have experience in urgent care, emergency medicine, or trauma medicine. Lahey Hospital & Medical Center required experience as an NP in a general setting for 1 to 2 years prior to applying. No program required prior experience in the field of dermatology.

Program length varied from 6 to 24 months, and cohort size typically was limited to 1 to 2 providers (eTable). Although the exact numbers could not be ascertained, most curricula focused on medical dermatology, including clinical and didactic components, but many offered electives such as cosmetic and procedural dermatology. Two institutions (20%) required independent research. Work typically was limited to 40 hours per week, and most paid a full-time employee salary and provided benefits such as health insurance, retirement, and paid leave (eTable). Kansas Medical Clinic (Topeka, Kansas) required at least 3 years of employment in an underserved community following program completion. The Oasis Dermatology private practice group in Texas required a 1-year teaching commitment after program completion. The Advanced Dermatology and Cosmetic Surgery group offered a full-time position upon program completion.

Comment

There is a large difference in the total number of training and credentialing hours when comparing graduate school training and postgraduate credentialing of medical and osteopathic physicians compared with APPs. A new graduate physician has at least twice as many clinical hours as a PA and 10 times as many clinical hours as an NP prior to starting residency. Physicians also typically complete at least 6 times the number of hours of certification examinations compared to NPs and PAs.1

Nurse practitioner students typically complete the 500 hours of prelicensure clinical training required for NP school in 2 to 4 years.2,3 The amount of time required for completion is dependent on the degree and experience of the student upon program entry (eg, bachelor of science in nursing vs master of science in nursing as a terminal degree). Physician assistant students are required to complete 2000 prelicensure clinical hours, and most PA programs are 3 years in duration.4 Many NP and PA programs require some degree of clinical experience prior to beginning graduate education.5

When comparing prelicensure examinations, questions assessing dermatologic knowledge comprise approximately 6% to 10% of the total questions on the United States Medical Licensing Examination Steps 1 and 2.6 The Comprehensive Osteopathic Medical Licensing Examination of the United States Level 1 and Level 2-Cognitive Evaluation both have at least 5% of questions dedicated to dermatology.7 Approximately 5% of the questions on the Physician Assistant National Certifying Examination are dedicated to dermatology.8 The dermatology content on either of the NP certification examinations is unclear.2,3 In the states of California, Indiana, and New York, national certification through the American Association of Nurse Practitioners or American Nurses Credentialing Center is not required for NPs to practice in their respective states.9

Regarding dermatologic board certification, a new graduate NP may obtain certification from the

Many of the programs we evaluated integrate APP trainees into resident education, allowing participation in equivalent didactic curricula, clinical rotations, and departmental academic activities. The salary and benefits associated with these programs are somewhat like those of resident physicians.15,16 While most tuition-based programs were excluded from our study due to their lack of credibility and alignment with our study criteria, we identified 2 specific programs that stood out as credible despite requiring students to pay tuition. These programs demonstrated a structured and rigorous curriculum with a clear focus on comprehensive dermatologic training, meeting our standards for inclusion. These programs offer dermatologic training for graduates of NP and PA programs at a cost to the student.15,16 The program at the Florida Atlantic University, Boca Raton, is largely online,15 and the program at the University of Miami, Florida, offers no direct clinical contact.16 These programs illustrate the variety of postgraduate dermatology curricula available nationally in comparison to resident salaries; however, they were not included in our formal analysis because they do not provide structured, in-person clinical training consistent with our inclusion criteria. Neither of these programs would enable participants to qualify for credentialing with the Dermatology Nurse Practitioner Certification Board after completion. While this study identified postgraduate training programs for APPs in dermatology advertised online, it is possible some were omitted or not advertised online.

While many of the postgraduate programs we evaluated provide unique educational opportunities for APPs, it is unknown if graduating providers are equipped to handle the care of patients with complex dermatologic needs. Regardless, the increased utilization of APPs by BCDs has been well documented over the past 2 decades.17-20 It has been suggested that a higher ratio of APPs to dermatologists can decrease the time it takes for a patient to be seen in a clinic.21-23 However, investigators have expressed concerns that APPs lack standardized surgical training and clinical hour requirements in the field of dermatology.24 Despite these concerns, Medicare claims data show that APPs are performing advanced surgical and cosmetic procedures at increasing rates.17,18 Other authors have questioned the cost-effectiveness of APPs, as multiple studies have shown that the number of biopsies needed to diagnose 1 case of skin cancer is higher for midlevel providers than for dermatologists.25-27

Conclusion

With the anticipated expansion of private equity in dermatology and the growth of our Medicare-eligible population, we are likely to see increased utilization of APPs to address the shortage of BCDs.28,29 Understanding the prelicensure and postlicensure clinical training requirements, examination hours, and extent of dermatology-focused education among APPs and BCDs can help dermatologists collaborate more effectively and ensure safe, high-quality patient care. Standardizing, improving, and providing high-quality education and promoting lifelong learning in the field of dermatology should be celebrated, and dermatologists are the skin experts best equipped to lead dermatologic education forward.

- Robeznieks A. Training gaps between physicians, nonphysicians are significant. American Medical Association. February 17, 2025. Accessed October 23, 2025. https://www.ama-assn.org/practice-management/scope-practice/training-gaps-between-physicians-nonphysicians-are-significant

- American Nurses Credentialing Center. Test content outline. Accessed October 6, 2025. https://www.nursingworld.org/globalassets/08282024-exam-24-npd-tco-website.pdf

- American Academy of Nurse Practitioners National Certification Board. AANPCB Family Nurse Practitioner Adult-Gerontology Primary Care Nurse Practitioner Psychiatric Mental Health Pratitioner: FNP, AGNP & PMHNP Certification Certification Handbook. American Academy of Nurse Practitioners Certification Board; 2023. Accessed October 6, 2025. https://www.aanpcert.org/resource/documents/AGNP%20FNP%20Candidate%20Handbook.pdf

- Society of Dermatology Physician Associates. SDPA Diplomate Fellowship. Accessed October 6, 2025. https://learning.dermpa.orgdiplomate-fellowship

- American Academy of Physician Associates. Become a PA. Accessed October 6, 2025. https://www.aapa.org/career-central/become-a-pa/

- United States Medical Licensing Examination. Prepare for your exam. Accessed October 6, 2025. https://www.usmle.org/prepare-your-exam

- National Board of Osteopathic Medical Examiners. Patient presentations related to the integumentary system. Accessed October 6, 2025. https://www.nbome.org/assessments/comlex-usa/comlex-usa-blueprint/d2-clinical-presentations/integumentary-system

- National Commission on Certification of Physician Assistants. PANCE content blueprint. Accessed October 6, 2025. https://prodcmsstoragesa.blob.core.windows.net/uploads/files/PANCEBlueprint.pdf

- American Association of Nurse Practitioners. Practice information by state. Accessed October 6, 2025. https://www.aanp.org/practice/practice-information-by-state

- Dermatology Nurse Practitioner Certification Board. Eligibility. Accessed October 6, 2025. https://www.dnpcb.org/eligibility.php

- National Board of Dermatology Physician Assistants. Certification. Accessed September 3, 2022.

- Society of Dermatology Physician Associates. SDPA statement regarding the ABDPA Board Certification Exam for derm PAs. October 8, 2019. Accessed October 6, 2025. https://www.dermpa.org/news/articles/2019-10/sdpa-statement-regarding-abdpa-board-certification-exam-derm-pas

- American Board of Dermatology. Residents and fellows. Accessed October 6, 2025. https://www.abderm.org/residents-and-fellows

- American Osteopathic Board of Dermatology. Primary certificaiton exam. Accessed October 6, 2025. https://certification.osteopathic.org/dermatology/certification-process/dermatology/written-exams/

- Florida Atlantic University. Christine E. Lynn College of Nursing. Dermatology nurse practitioner certificate program. Accessed October 6, 2025. https://www.fau.edu/nursing/academics/certificates/dermatology-program/

- Dr. Phillip Frost Department of Dermatology and Cutaneous Surgery. Advanced Practitioner Program.

- Coldiron B, Ratnarathorn M. Scope of physician procedures independently billed by mid-level providers in the office setting. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:1153-1159.

- Zhang M, Zippin J, Kaffenberger B. Trends and scope of dermatology procedures billed by advanced practice professionals from 2012 through 2015. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:1040-1044.

- Resneck J Jr, Kimball AB. The dermatology workforce shortage. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:50-54.

- Kimball AB, Resneck JS Jr. The US dermatology workforce: a specialty remains in shortage. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:741-745.

- Creadore A, Desai S, Li SJ, et al. Insurance acceptance, appointment wait time, and dermatologist access across practice types in the US. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:181-188.

- Braun RT, Bond AM, Qian Y, et al. Private equity in dermatology: effect on price, utilization, and spending. Health Aff (Millwood). 2021;40:727-735.

- Skaljic M, Lipoff JB. Association of private equity ownership with increased employment of advanced practice professionals in outpatient dermatology offices. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:1178-1180.

- Jalian HR, Avram MM. Mid-level practitioners in dermatology: a need for further study and oversight. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:1149-1151.

- Sarzynski E, Barry H. Current evidence and controversies: advanced practice providers in healthcare. Am J Manag Care. 2019;25:366-368.

- Nault A, Zhang C, Kim K, et al. Biopsy use in skin cancer diagnosis: comparing dermatology physicians and advanced practice professionals. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:899-902.

- Anderson AM, Matsumoto M, Saul MI, et al. Accuracy of skin cancer diagnosis by physician assistants compared with dermatologists in a large health care system. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:569-573.

- Sung C, Salem S, Oulee A, et al. A systematic review: landscape of private equity in dermatology from past to present. J Drugs Dermatol. 2023 Apr 1;22:404-409. doi: 10.36849/JDD.6892.

- CMS releases National Healthcare Expenditure and enrollment projections through 2031. Health Management Associates. July 13, 2023. Accessed October 23, 2025. https://www.healthmanagement.com/blog/cms-releases-national-healthcare-expenditure-and-enrollment-projections-through-2031/

- Robeznieks A. Training gaps between physicians, nonphysicians are significant. American Medical Association. February 17, 2025. Accessed October 23, 2025. https://www.ama-assn.org/practice-management/scope-practice/training-gaps-between-physicians-nonphysicians-are-significant

- American Nurses Credentialing Center. Test content outline. Accessed October 6, 2025. https://www.nursingworld.org/globalassets/08282024-exam-24-npd-tco-website.pdf

- American Academy of Nurse Practitioners National Certification Board. AANPCB Family Nurse Practitioner Adult-Gerontology Primary Care Nurse Practitioner Psychiatric Mental Health Pratitioner: FNP, AGNP & PMHNP Certification Certification Handbook. American Academy of Nurse Practitioners Certification Board; 2023. Accessed October 6, 2025. https://www.aanpcert.org/resource/documents/AGNP%20FNP%20Candidate%20Handbook.pdf

- Society of Dermatology Physician Associates. SDPA Diplomate Fellowship. Accessed October 6, 2025. https://learning.dermpa.orgdiplomate-fellowship

- American Academy of Physician Associates. Become a PA. Accessed October 6, 2025. https://www.aapa.org/career-central/become-a-pa/

- United States Medical Licensing Examination. Prepare for your exam. Accessed October 6, 2025. https://www.usmle.org/prepare-your-exam

- National Board of Osteopathic Medical Examiners. Patient presentations related to the integumentary system. Accessed October 6, 2025. https://www.nbome.org/assessments/comlex-usa/comlex-usa-blueprint/d2-clinical-presentations/integumentary-system

- National Commission on Certification of Physician Assistants. PANCE content blueprint. Accessed October 6, 2025. https://prodcmsstoragesa.blob.core.windows.net/uploads/files/PANCEBlueprint.pdf

- American Association of Nurse Practitioners. Practice information by state. Accessed October 6, 2025. https://www.aanp.org/practice/practice-information-by-state

- Dermatology Nurse Practitioner Certification Board. Eligibility. Accessed October 6, 2025. https://www.dnpcb.org/eligibility.php

- National Board of Dermatology Physician Assistants. Certification. Accessed September 3, 2022.

- Society of Dermatology Physician Associates. SDPA statement regarding the ABDPA Board Certification Exam for derm PAs. October 8, 2019. Accessed October 6, 2025. https://www.dermpa.org/news/articles/2019-10/sdpa-statement-regarding-abdpa-board-certification-exam-derm-pas

- American Board of Dermatology. Residents and fellows. Accessed October 6, 2025. https://www.abderm.org/residents-and-fellows

- American Osteopathic Board of Dermatology. Primary certificaiton exam. Accessed October 6, 2025. https://certification.osteopathic.org/dermatology/certification-process/dermatology/written-exams/

- Florida Atlantic University. Christine E. Lynn College of Nursing. Dermatology nurse practitioner certificate program. Accessed October 6, 2025. https://www.fau.edu/nursing/academics/certificates/dermatology-program/

- Dr. Phillip Frost Department of Dermatology and Cutaneous Surgery. Advanced Practitioner Program.

- Coldiron B, Ratnarathorn M. Scope of physician procedures independently billed by mid-level providers in the office setting. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:1153-1159.

- Zhang M, Zippin J, Kaffenberger B. Trends and scope of dermatology procedures billed by advanced practice professionals from 2012 through 2015. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:1040-1044.

- Resneck J Jr, Kimball AB. The dermatology workforce shortage. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:50-54.

- Kimball AB, Resneck JS Jr. The US dermatology workforce: a specialty remains in shortage. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:741-745.

- Creadore A, Desai S, Li SJ, et al. Insurance acceptance, appointment wait time, and dermatologist access across practice types in the US. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:181-188.

- Braun RT, Bond AM, Qian Y, et al. Private equity in dermatology: effect on price, utilization, and spending. Health Aff (Millwood). 2021;40:727-735.

- Skaljic M, Lipoff JB. Association of private equity ownership with increased employment of advanced practice professionals in outpatient dermatology offices. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:1178-1180.

- Jalian HR, Avram MM. Mid-level practitioners in dermatology: a need for further study and oversight. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:1149-1151.

- Sarzynski E, Barry H. Current evidence and controversies: advanced practice providers in healthcare. Am J Manag Care. 2019;25:366-368.

- Nault A, Zhang C, Kim K, et al. Biopsy use in skin cancer diagnosis: comparing dermatology physicians and advanced practice professionals. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:899-902.

- Anderson AM, Matsumoto M, Saul MI, et al. Accuracy of skin cancer diagnosis by physician assistants compared with dermatologists in a large health care system. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:569-573.

- Sung C, Salem S, Oulee A, et al. A systematic review: landscape of private equity in dermatology from past to present. J Drugs Dermatol. 2023 Apr 1;22:404-409. doi: 10.36849/JDD.6892.

- CMS releases National Healthcare Expenditure and enrollment projections through 2031. Health Management Associates. July 13, 2023. Accessed October 23, 2025. https://www.healthmanagement.com/blog/cms-releases-national-healthcare-expenditure-and-enrollment-projections-through-2031/

The Current State of Postgraduate Dermatology Training Programs for Advanced Practice Providers

The Current State of Postgraduate Dermatology Training Programs for Advanced Practice Providers

Practice Points

- Postgraduate dermatology training programs are available for advanced practice providers (APPs), but they are optional and lack a formal accreditation process.

- Awareness of these programs and the differences between APPs and physician training may help dermatologists provide safe and effective care in collaborative or supervisory roles.

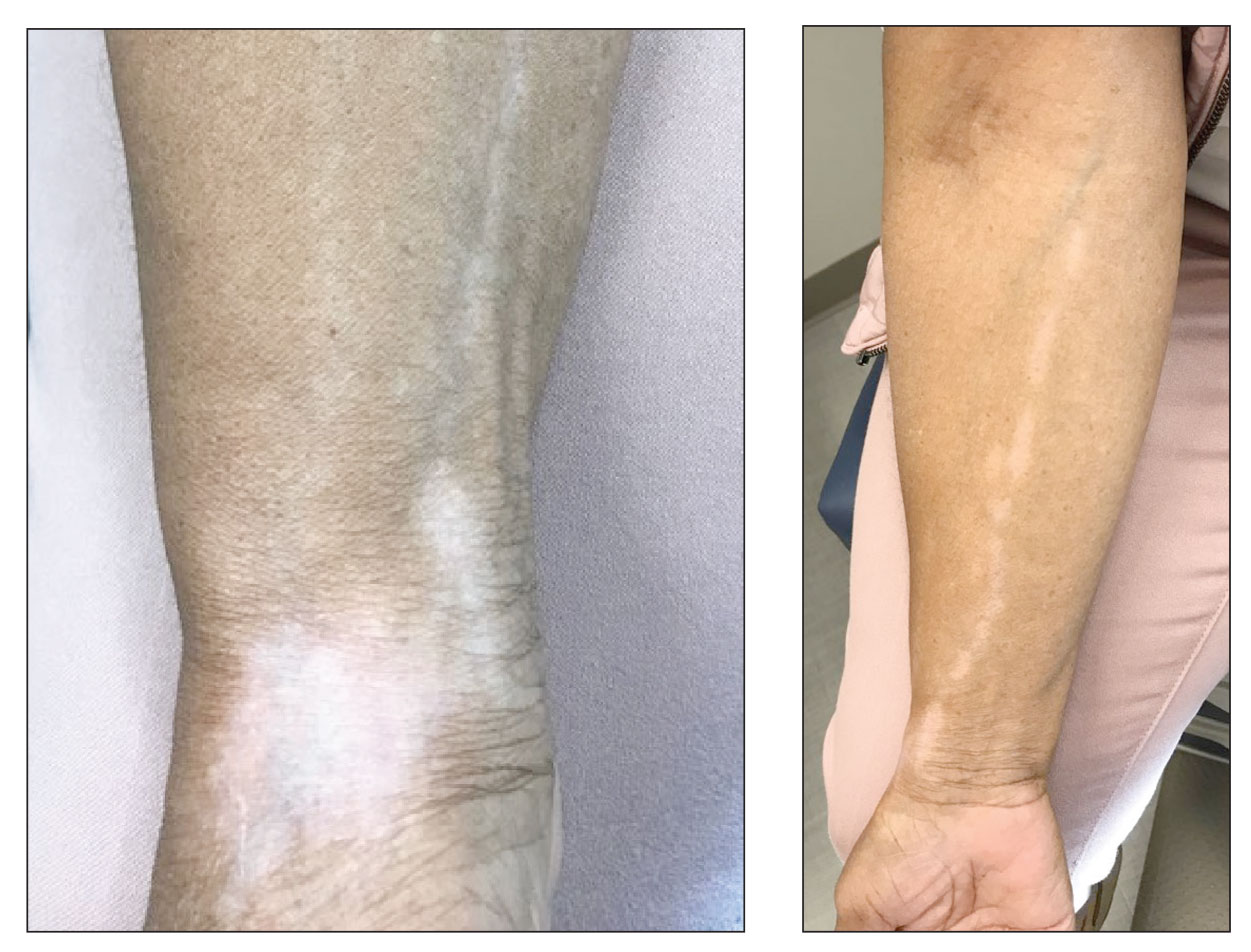

Linear Hypopigmentation on the Right Arm

The Diagnosis: Chemical Leukoderma

A clinical diagnosis of chemical leukoderma was made. In our patient, the observed linear hypopigmentation likely resulted from the prior treatment for De Quervain tenosynovitis in which an intralesional corticosteroid entered the lymphatic channel causing a linear distribution of chemical leukoderma. The hypopigmentation self-resolved at 6-month follow-up, and the patient was counseled to continue steroid injections if indicated.

Chemical leukoderma is an acquired depigmenting dermatosis that displays vitiligolike patterning. Detailed personal and family history in addition to complete physical examination are crucial given the inability to distinguish chemical leukoderma from vitiligo on histopathology. A set of clinical criteria proposed by Ghosh and Mukhopadhyay1 includes the presence of acquired depigmented macules and patches resembling vitiligo, history of repeat exposure to certain chemical substances, hypopigmentation at the site of exposure, and/ or confettilike white macules. Three of these 4 clinical findings must be present to establish a diagnosis of chemical leukoderma. The extent of disease involvement may be graded as follows: Stage I is defined as leukoderma only at the site of contact to the offending agent. Stage II involvement is characterized by local spread beyond the exposure site via the lymphatic system. Stages IIIA and IIIB leukoderma entail hematogenous spread distant to the site of chemical exposure. Although stage IIIA leukoderma is limited to cutaneous involvement, stage IIIB findings are marked by systemic organ involvement. Stage IV disease is defined by the distant spread of hypopigmented macules and patches that continues following 1 year of strict avoidance of the causative agent.1

The pathogenesis behind chemical leukoderma is not completely understood. Studies have suggested that individuals with certain genetic susceptibilities are predisposed to developing the condition after being exposed to chemicals with melanocytotoxic properties.2,3 It has been proposed that the chemicals accelerate pre-existing cellular stress cascades within melanocytes to levels higher than what healthy cells can tolerate. Genetic factors can increase an individual’s total melanocytic stress or establish a lower cellular threshold for stress than what the immune system can manage.4 These influences culminate in an inflammatory response that results in melanocytic destruction and subsequent cutaneous hypopigmentation.

The most well-known offending chemical agents are phenol and catechol derivatives, such as hydroquinone, which is used in topical bleaching agents to treat diseases of hyperpigmentation, including melasma.2 Potent topical or intralesional corticosteroids also may precipitate chemical leukoderma, most notably in individuals with darker skin tones. Hypomelanosis induced by intralesional steroids frequently occurs weeks to months after administration and commonly is observed in a stellate or linear pattern with an irregular outline.5 Other offending chemical agents include sulfhydryls, mercurials, arsenic, benzoyl peroxide, azelaic acid, imiquimod, chloroquine, and tyrosine kinase inhibitors.2,5

Segmental vitiligo is characterized by unilateral hypopigmentation in a linear or blocklike distribution that does not cross the midline. However, onset of segmental vitiligo classically occurs prior to 30 years of age and frequently is related with early leukotrichia.6 Additionally, the hypomelanosis associated with segmental vitiligo more often presents as broad bands or patches that occasionally have a blaschkoid distribution and most commonly appear on the face.5 Lichen striatus is a lichenoid dermatosis that presents as asymptomatic pink or hypopigmented papules that follow the Blaschko lines, often favoring the extremities. Postinflammatory hypopigmentation also may occur as an associated sequela of resolved lichen striatus. Although the disease onset of lichen striatus may occur in adulthood, it typically appears in childhood and is triggered by factors such as trauma, hypersensitivity reactions, viral infections, and medications. Physical injuries such as trauma following surgical procedures also can lead to hypomelanosis; however, our patient denied any relevant surgical history. Progressive macular hypomelanosis is a skin condition presenting as ill-defined, nummular, hypopigmented macules or patches that commonly affects women with darker skin tones with an ethnic background from a tropical location or residing in a tropical environment.5 Lesions frequently appear on the trunk and rarely progress to the proximal extremities, making it an unlikely diagnosis for our patient.

In most cases of chemical leukoderma, spontaneous repigmentation often occurs within 12 months after the elimination of the offending substance; however, hypopigmented lesions may persist or continue to develop at sites distant from the initial site despite discontinuing the causative agent.1 Therapies for vitiligo, such as topical corticosteroids, topical immunosuppressants, narrowband UVB phototherapy, and psoralen plus UVA photochemotherapy, may be utilized for chemical leukoderma that does not self-resolve.

- Ghosh S, Mukhopadhyay S. Chemical leucoderma: a clinicoaetiological study of 864 cases in the perspective of a developing country [published online September 6, 2008]. Br J Dermatol. 2009;160:40-47.

- Ghosh S. Chemical leukoderma: what’s new on etiopathological and clinical aspects? Indian J Dermatol. 2010;55:255.

- Boissy RE, Manga P. On the etiology of contact/occupational vitiligo. Pigment Cell Res. 2004;17:208-214.

- Harris J. Chemical-induced vitiligo. Dermatol Clin. 2017; 35:151-161.

- Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, et al. Vitiligo and other disorders of hypopigmentation. In: Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Mosby/Elsevier; 2018:1087-1114.

- Rodrigues M, Ezzedine K, Hamzavi I, et al. New discoveries in the pathogenesis and classification of vitiligo. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:1-13.

The Diagnosis: Chemical Leukoderma

A clinical diagnosis of chemical leukoderma was made. In our patient, the observed linear hypopigmentation likely resulted from the prior treatment for De Quervain tenosynovitis in which an intralesional corticosteroid entered the lymphatic channel causing a linear distribution of chemical leukoderma. The hypopigmentation self-resolved at 6-month follow-up, and the patient was counseled to continue steroid injections if indicated.

Chemical leukoderma is an acquired depigmenting dermatosis that displays vitiligolike patterning. Detailed personal and family history in addition to complete physical examination are crucial given the inability to distinguish chemical leukoderma from vitiligo on histopathology. A set of clinical criteria proposed by Ghosh and Mukhopadhyay1 includes the presence of acquired depigmented macules and patches resembling vitiligo, history of repeat exposure to certain chemical substances, hypopigmentation at the site of exposure, and/ or confettilike white macules. Three of these 4 clinical findings must be present to establish a diagnosis of chemical leukoderma. The extent of disease involvement may be graded as follows: Stage I is defined as leukoderma only at the site of contact to the offending agent. Stage II involvement is characterized by local spread beyond the exposure site via the lymphatic system. Stages IIIA and IIIB leukoderma entail hematogenous spread distant to the site of chemical exposure. Although stage IIIA leukoderma is limited to cutaneous involvement, stage IIIB findings are marked by systemic organ involvement. Stage IV disease is defined by the distant spread of hypopigmented macules and patches that continues following 1 year of strict avoidance of the causative agent.1

The pathogenesis behind chemical leukoderma is not completely understood. Studies have suggested that individuals with certain genetic susceptibilities are predisposed to developing the condition after being exposed to chemicals with melanocytotoxic properties.2,3 It has been proposed that the chemicals accelerate pre-existing cellular stress cascades within melanocytes to levels higher than what healthy cells can tolerate. Genetic factors can increase an individual’s total melanocytic stress or establish a lower cellular threshold for stress than what the immune system can manage.4 These influences culminate in an inflammatory response that results in melanocytic destruction and subsequent cutaneous hypopigmentation.

The most well-known offending chemical agents are phenol and catechol derivatives, such as hydroquinone, which is used in topical bleaching agents to treat diseases of hyperpigmentation, including melasma.2 Potent topical or intralesional corticosteroids also may precipitate chemical leukoderma, most notably in individuals with darker skin tones. Hypomelanosis induced by intralesional steroids frequently occurs weeks to months after administration and commonly is observed in a stellate or linear pattern with an irregular outline.5 Other offending chemical agents include sulfhydryls, mercurials, arsenic, benzoyl peroxide, azelaic acid, imiquimod, chloroquine, and tyrosine kinase inhibitors.2,5

Segmental vitiligo is characterized by unilateral hypopigmentation in a linear or blocklike distribution that does not cross the midline. However, onset of segmental vitiligo classically occurs prior to 30 years of age and frequently is related with early leukotrichia.6 Additionally, the hypomelanosis associated with segmental vitiligo more often presents as broad bands or patches that occasionally have a blaschkoid distribution and most commonly appear on the face.5 Lichen striatus is a lichenoid dermatosis that presents as asymptomatic pink or hypopigmented papules that follow the Blaschko lines, often favoring the extremities. Postinflammatory hypopigmentation also may occur as an associated sequela of resolved lichen striatus. Although the disease onset of lichen striatus may occur in adulthood, it typically appears in childhood and is triggered by factors such as trauma, hypersensitivity reactions, viral infections, and medications. Physical injuries such as trauma following surgical procedures also can lead to hypomelanosis; however, our patient denied any relevant surgical history. Progressive macular hypomelanosis is a skin condition presenting as ill-defined, nummular, hypopigmented macules or patches that commonly affects women with darker skin tones with an ethnic background from a tropical location or residing in a tropical environment.5 Lesions frequently appear on the trunk and rarely progress to the proximal extremities, making it an unlikely diagnosis for our patient.

In most cases of chemical leukoderma, spontaneous repigmentation often occurs within 12 months after the elimination of the offending substance; however, hypopigmented lesions may persist or continue to develop at sites distant from the initial site despite discontinuing the causative agent.1 Therapies for vitiligo, such as topical corticosteroids, topical immunosuppressants, narrowband UVB phototherapy, and psoralen plus UVA photochemotherapy, may be utilized for chemical leukoderma that does not self-resolve.

The Diagnosis: Chemical Leukoderma

A clinical diagnosis of chemical leukoderma was made. In our patient, the observed linear hypopigmentation likely resulted from the prior treatment for De Quervain tenosynovitis in which an intralesional corticosteroid entered the lymphatic channel causing a linear distribution of chemical leukoderma. The hypopigmentation self-resolved at 6-month follow-up, and the patient was counseled to continue steroid injections if indicated.

Chemical leukoderma is an acquired depigmenting dermatosis that displays vitiligolike patterning. Detailed personal and family history in addition to complete physical examination are crucial given the inability to distinguish chemical leukoderma from vitiligo on histopathology. A set of clinical criteria proposed by Ghosh and Mukhopadhyay1 includes the presence of acquired depigmented macules and patches resembling vitiligo, history of repeat exposure to certain chemical substances, hypopigmentation at the site of exposure, and/ or confettilike white macules. Three of these 4 clinical findings must be present to establish a diagnosis of chemical leukoderma. The extent of disease involvement may be graded as follows: Stage I is defined as leukoderma only at the site of contact to the offending agent. Stage II involvement is characterized by local spread beyond the exposure site via the lymphatic system. Stages IIIA and IIIB leukoderma entail hematogenous spread distant to the site of chemical exposure. Although stage IIIA leukoderma is limited to cutaneous involvement, stage IIIB findings are marked by systemic organ involvement. Stage IV disease is defined by the distant spread of hypopigmented macules and patches that continues following 1 year of strict avoidance of the causative agent.1

The pathogenesis behind chemical leukoderma is not completely understood. Studies have suggested that individuals with certain genetic susceptibilities are predisposed to developing the condition after being exposed to chemicals with melanocytotoxic properties.2,3 It has been proposed that the chemicals accelerate pre-existing cellular stress cascades within melanocytes to levels higher than what healthy cells can tolerate. Genetic factors can increase an individual’s total melanocytic stress or establish a lower cellular threshold for stress than what the immune system can manage.4 These influences culminate in an inflammatory response that results in melanocytic destruction and subsequent cutaneous hypopigmentation.

The most well-known offending chemical agents are phenol and catechol derivatives, such as hydroquinone, which is used in topical bleaching agents to treat diseases of hyperpigmentation, including melasma.2 Potent topical or intralesional corticosteroids also may precipitate chemical leukoderma, most notably in individuals with darker skin tones. Hypomelanosis induced by intralesional steroids frequently occurs weeks to months after administration and commonly is observed in a stellate or linear pattern with an irregular outline.5 Other offending chemical agents include sulfhydryls, mercurials, arsenic, benzoyl peroxide, azelaic acid, imiquimod, chloroquine, and tyrosine kinase inhibitors.2,5

Segmental vitiligo is characterized by unilateral hypopigmentation in a linear or blocklike distribution that does not cross the midline. However, onset of segmental vitiligo classically occurs prior to 30 years of age and frequently is related with early leukotrichia.6 Additionally, the hypomelanosis associated with segmental vitiligo more often presents as broad bands or patches that occasionally have a blaschkoid distribution and most commonly appear on the face.5 Lichen striatus is a lichenoid dermatosis that presents as asymptomatic pink or hypopigmented papules that follow the Blaschko lines, often favoring the extremities. Postinflammatory hypopigmentation also may occur as an associated sequela of resolved lichen striatus. Although the disease onset of lichen striatus may occur in adulthood, it typically appears in childhood and is triggered by factors such as trauma, hypersensitivity reactions, viral infections, and medications. Physical injuries such as trauma following surgical procedures also can lead to hypomelanosis; however, our patient denied any relevant surgical history. Progressive macular hypomelanosis is a skin condition presenting as ill-defined, nummular, hypopigmented macules or patches that commonly affects women with darker skin tones with an ethnic background from a tropical location or residing in a tropical environment.5 Lesions frequently appear on the trunk and rarely progress to the proximal extremities, making it an unlikely diagnosis for our patient.

In most cases of chemical leukoderma, spontaneous repigmentation often occurs within 12 months after the elimination of the offending substance; however, hypopigmented lesions may persist or continue to develop at sites distant from the initial site despite discontinuing the causative agent.1 Therapies for vitiligo, such as topical corticosteroids, topical immunosuppressants, narrowband UVB phototherapy, and psoralen plus UVA photochemotherapy, may be utilized for chemical leukoderma that does not self-resolve.

- Ghosh S, Mukhopadhyay S. Chemical leucoderma: a clinicoaetiological study of 864 cases in the perspective of a developing country [published online September 6, 2008]. Br J Dermatol. 2009;160:40-47.

- Ghosh S. Chemical leukoderma: what’s new on etiopathological and clinical aspects? Indian J Dermatol. 2010;55:255.

- Boissy RE, Manga P. On the etiology of contact/occupational vitiligo. Pigment Cell Res. 2004;17:208-214.

- Harris J. Chemical-induced vitiligo. Dermatol Clin. 2017; 35:151-161.

- Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, et al. Vitiligo and other disorders of hypopigmentation. In: Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Mosby/Elsevier; 2018:1087-1114.

- Rodrigues M, Ezzedine K, Hamzavi I, et al. New discoveries in the pathogenesis and classification of vitiligo. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:1-13.

- Ghosh S, Mukhopadhyay S. Chemical leucoderma: a clinicoaetiological study of 864 cases in the perspective of a developing country [published online September 6, 2008]. Br J Dermatol. 2009;160:40-47.

- Ghosh S. Chemical leukoderma: what’s new on etiopathological and clinical aspects? Indian J Dermatol. 2010;55:255.

- Boissy RE, Manga P. On the etiology of contact/occupational vitiligo. Pigment Cell Res. 2004;17:208-214.

- Harris J. Chemical-induced vitiligo. Dermatol Clin. 2017; 35:151-161.

- Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, et al. Vitiligo and other disorders of hypopigmentation. In: Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Mosby/Elsevier; 2018:1087-1114.

- Rodrigues M, Ezzedine K, Hamzavi I, et al. New discoveries in the pathogenesis and classification of vitiligo. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:1-13.

A 73-year-old woman presented to the dermatology clinic with hypopigmentation along the right arm. Her medical history was notable for prior treatment with intralesional triamcinolone injections for De Quervain tenosynovitis. Two months after receiving the steroid injections she noted progressive spreading of an asymptomatic white discoloration originating on the right wrist. Physical examination revealed a hypopigmented atrophic patch on the medial aspect of the right wrist (left) with linear hypopigmented patches extending proximally up the forearm (right).