User login

Perimenopausal depression: Covering mood and vasomotor symptoms

Symptoms of perimenopausal depression are not inherently different from those of depression diagnosed at any other time in life, but they present in a unique context:

- Hormonal fluctuations may persist for a long duration.

- Women experiencing hormonal fluctuations may be vulnerable to mood problems.

- Psychosocial/psychodynamic stressors often complicate this life transition.

Managing perimenopausal depression has become more complicated since the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) studies found fewer benefits and greater risks with hormone replacement therapy (HRT) than had been perceived. This article discusses the clinical presentation of perimenopausal depression, its risk factors, and treatment options in post-WHI psychiatric practice.

Who is at risk?

Perimenopausal depression is diagnosed when onset of major depressive disorder (MDD) is associated with menstrual cycle irregularity and/or somatic symptoms of the menopausal transition.1 Diagnosis is based on the overall clinical picture, and treatment requires a thoughtful exploration of the complex relationship between hormonal function and mood regulation.

Presentation. For many women, perimenopause is characterized by mild to severe vasomotor, cognitive, and mood symptoms (Table 1). Thus, in your workup of depression in midlife women, document somatic symptoms—such as hot flushes, vaginal dryness, and incontinence—and affective/behavioral symp toms such as mood and sleep disturbances.

Table 1

Vasomotor, cognitive, and mood symptoms of perimenopause

| Vasomotor | Cognitive and mood |

|---|---|

| Hot flushes | Decreased concentration |

| Sweating | Anxiety |

| Heart palpitations | Irritability |

| Painful intercourse | Mood lability |

| Vaginal dryness and discomfort | Memory difficulty |

| Sleep disruption | |

| Headache |

Explore psychiatric and medical histories of your patient and her close relatives. Ask about depression, dysthymia, hypomania, or mood fluctuations around hormonal events such as menses, pregnancy, postpartum, or starting/stopping oral contraceptives. In the differential diagnosis, consider:

- Is low mood temporally connected with hot flushes and disturbed sleep?

- Is low mood secondary to stressful life events?

- Does the patient have another medical illness (such as thyroid disorder) with symptoms similar to depression?

- Is low mood secondary to anxiety or another psychiatric disorder?

Screening. Menopause is considered to have been reached after 12 months of amenorrhea not due to another cause. Median ages for this transition in the United States are 47.5 for perimenopause and 51 for menopause, with an average of 8 years between regular cycles and amenorrhea.2 Therefore, begin talking with women about perimenopausal symptoms when they turn 40.

Evidence supports screening perimenopausal women for depressive symptoms even when their primary complaints are vasomotor. The Greene Climacteric Scale3 is convenient for quantifying and monitoring perimenopausal symptoms. It includes depressive symptoms plus physical and cognitive markers. The Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology—Self Report (QIDS-SR)4 questionnaire:

- takes minutes to complete

- is easy to score

- quantitates the number and severity of depressive symptoms (see Related Resources).

Psychosocial factors can predict depression at any time in life, but some are specific to the menopausal transition (Table 2).5 The “empty nest syndrome,” for example, is often used to explain depressive symptoms in midlife mothers, but no evidence links mood lability with the maturation and departure of children. What may be more stressing for women is supporting adolescents/young adults in their exit to independence while caring for aging parents.

Table 2

Risk factors for depression in women

| Predictive over lifetime | High risk during menopausal transition |

|---|---|

| History of depression | History of PMS, perinatal depression, mood symptoms associated with contraceptives |

| Family history of affective disorders | Premature or surgical menopause |

| Insomnia | Lengthy menopausal transition (≥27 months) |

| Reduced physical activities | Persistent and/or severe vasomotor symptoms |

| Weight gain | Negative attitudes toward menopause and aging |

| Less education | |

| Perceived lower economic status | |

| Perceived lower social support | |

| Perceived lower health status | |

| Smoking | |

| Stressful life events | |

| History of trauma | |

| Marital dissatisfaction | |

| PMS: Premenstrual syndrome | |

Sociocultural beliefs about sexuality and menopause may play a role in how your patient experiences and reports her symptoms. In some cultures, menopause elevates a woman’s social status and is associated with increased respect and authority. In others, such as Western societies that emphasize youth and beauty, women may view menopause and its physical changes in a negative light.6

Therefore, give careful attention to the psychosocial context of menopause to your patient and the social resources available to her. Questions to ask include:

- Has your lifestyle changed recently?

- Have your husband, family members, or close friends noticed any changes in your functioning?

- Is there anyone in your life that you feel comfortable confiding in?

Explaining the complexity of this life transition may ease her anxiety by normalizing her experience, helping her understand her symptoms, and validating her distress.

What might be the cause?

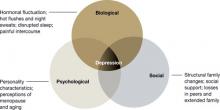

Although the exact pathophysiology of perimenopausal depression is unknown, hormonal changes,7 general health, the experience of menopause,8 and the psychosocial context2 likely work together to increase vulnerability for depressive symptoms (Figure).

Figure Biopsychosocial milieu of depression during perimenopauseHormonal fluctuation. The estrogen withdrawal theory7 explains depressive symptoms as resulting from a sustained decline in ovarian estrogen in tandem with spiking secretions of follicle-stimulating hormone by the pituitary. The finding that women with surgical menopause have a higher incidence of depressive symptoms than women with natural menopause supports this hypothesis.

Mood disorders occur across various female reproductive events, and increased risk appears to be associated with fluctuating gonadal hormones. Thus, declining estrogen may be less causative of perimenopausal depression than extreme fluctuations in estradiol activity.9,10

Estrogen interacts with dopamine, norepinephrine, beta-endorphin, and serotonin metabolism. In particular, estrogen facilitates serotonin delivery to neurons across the brain. These findings—and the success of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) in treating mood disorders—support the theory that fluctuating estrogen affects the serotonergic system and may cause depressive symptoms.

‘Domino theory.’ Others have hypothesized that depressive symptoms are the secondhand result of somatic symptoms of perimenopause. In a “domino effect,” hot flushes and night sweats disrupt women’s sleep, bringing fatigue and impaired daytime concentration, which lead to irritability and feelings of being overwhelmed.8

This theory, which incorporates perimenopausal hormone changes, is supported by elevated levels of depression in women who report frequent and intense vasomotor symptoms persisting >27 months.2

The psychosocial theory suggests that depression results from increased stress or adverse events.2 Midlife women with depressive symptoms report many possible sources of stress:

- demanding jobs

- family responsibilities

- dual demands of career and family

- little time for self

- poverty or employment stressors

- not enough sleep

- changing social relationships.

Negative interpretations of aging or the menopausal transition also have been implicated in cross-cultural studies.6 The predictive nature of psychosocial issues for depression during perimenopause supports this theory.

Evidence-based treatment

HRT. Research and clinical reports suggest that estrogen may have antidepressant effects, either alone or as an adjunct to antidepressant medication.11 Before the WHI studies, expert consensus guidelines on treating depression in women recommended HRT as first-line treatment for patients experiencing a first lifetime onset of mild to moderate depression during perimenopause.12 WHI findings since 2002 that associated HRT with increased risk of stroke, deep vein thrombosis, and pulmonary embolism—without clear protection against coronary heart disease or cognitive decline—have left HRT a controversial option for treating perimenopausal depression. In the WHI trials:

- 10,739 postmenopausal women age 50 to 79 without a uterus received unopposed conjugated equine estrogens, 0.625 mg/d, or placebo for an average 6.8 years.13

- 16,608 postmenopausal women age 50 to 79 with an intact uterus received combination HRT (conjugated equine estrogens, 0.625 mg/d, plus 2.5 mg of medroxyprogesterone), or placebo for an average 5.6 years.14

The study using combination HRT found increased risks of breast cancer, ischemic stroke, blood clots, and coronary heart disease.15 A follow-up study showed that vasomotor symptoms returned in more than one-half the women after they stopped using combination HRT.15

A companion WHI trial found that estrogen, 0.625 mg/d—given unopposed or with a progestin—did not prevent cognitive decline in women age 65 to 79 and may have been associated with a slightly greater risk of probable dementia.16,17

The FDA recommends that women who want to use HRT to control menopausal symptoms use the lowest effective dose for the shortest time necessary.18

Antidepressants. SSRIs may be more useful than estrogen for producing MDD remission in perimenopausal women.19 SSRIs and other psychotropics may reduce perimenopausal vasomotor symptoms in addition to addressing depressive symptoms (Table 3). When choosing antidepressant therapy, consider the patient’s dominant presenting perimenopausal symptoms and side effects associated with treatment.20

Table 3

Nonhormone medications for perimenopausal depression: Evidence-based dosages and target symptoms

| Medication | Dosage effective for perimenopausal depression | Symptoms assessed |

|---|---|---|

| SSRIs | ||

| Citaloprama | 40 to 60 mg | Depressive and vasomotor |

| Escitalopramb,c | 5 to 20 mg | Depressive and vasomotor |

| Fluoxetined | 20 to 40 mg | Depressive and vasomotor |

| Paroxetinee,f | 12.5 or 25 mg | Depressive and vasomotor |

| Sertralineg | 100 mg | Depressive and vasomotor |

| Other antidepressants | ||

| Duloxetineh | 60 to 120 mg | Depressive and vasomotor |

| Venlafaxinei | 75 to 225 mg | Depressive and vasomotor |

| Mirtazapinej | 30 to 60 mg | Severe depressive symptoms; used as an adjunct to estrogen |

| Hypnotics | ||

| Eszopiclonek | 3 mg | Depressive and vasomotor; insomnia |

| Zolpideml | 5 to 10 mg | Insomnia |

| Anticonvulsant | ||

| Gabapentinm | 300 to 900 mg | Vasomotor |

| SSRIs: selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors | ||

| Source: Reference Citations | ||

Nonpharmacologic interventions are viable options for women who are reluctant to begin HRT or psychotropics.

Psychotherapy. Interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT) and cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) have been recommended to address psychosocial elements of perimenopausal mood lability.21 For women with climacteric depression, IPT focuses on role transitions, loss, and interpersonal support, whereas CBT focuses on identifying and altering negative thoughts and beliefs.

Although no randomized trials have examined psychotherapies for perimenopausal depression, a pilot open trial provided group CBT—psychoeducation, group discussion, and coping skills training—to 30 women with climacteric symptoms. Anxiety, depression, partnership relations, overall sexuality, hot flushes, and cardiac complaints improved significantly, based on pre- and post-intervention surveys. Sexual satisfaction and the stressfulness of menopausal symptoms did not change.22

Integrative medicine. Plant-based substances and herbal remedies such as phytoestrogens, red-clover isoflavones, black cohosh, and evening primrose oil have been included in a few research investigations, and the evidence is equivocal. Because of potential interactions between alternative therapies and medications, inquire about their use. Although a comprehensive review of integrative medicine for perimenopausal symptoms is beyond the scope of this article, see suggested readings (Box).

- Albertazzi P. Non-estrogenic approaches for the treatment of climacteric symptoms. Climacteric 2007;10(suppl 2):115-20.

- Blair YA, Gold EB, Zhang G, et al. Use of complementary and alternative medicine during the menopause transition: longitudinal results from the Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation. Menopause 2008;15:32-43.

- Freeman MP, Helgason C, Hill RA. Selected integrative medicine treatments for depression: considerations for women. J Am Med Womens Assoc 2004;59(3):216-24.

- Mischoulon D. Update and critique of natural remedies as antidepressant treatments. Psychiatr Clin North Am 2007;30:51-68.

- Thachil AF, Mohan R, Bhugra D. The evidence base of complementary and alternative therapies in depression. J Affect Disord 2007;97:23-35.

- Tremblay A, Sheeran L, Aranda SK. Psychoeducational interventions to alleviate hot flashes: a systematic review. J North Am Menopause Soc 2008;15:193-202.

Clinical recommendations

Explore options with your patient; discuss side effects, risks, and expected minimum duration of treatment. Antidepressants, hormonal therapies, psychotherapy, and complementary and alternative treatments each might have a role in managing perimenopausal depression. A patient’s preferences, psychiatric history, and depression severity help determine which options to consider and in what order. How she responded to past treatments also can help you individualize a plan.

HRT may be appropriate for women who express a preference for HRT, have responded well to past hormone therapy, and have no personal history or high-risk factors for breast cancer. Based on the WHI findings, we consider a history of breast cancer in the patient or a first- or second-degree relative a contraindication to HRT.

Estrogen can be used alone or with an antidepressant. Studies support 17β-estradiol, 0.1 to 0.3 mg/d, for 8 to 12 weeks.11,23 Concomitant progesterone may be indicated to offset the effects of unopposed estrogen in women with an intact uterus. This option calls for an informed discussion with the patient about risks and benefits.

No data support long-term use of estrogen for recurrent or chronic depression. Because HRT’s risks and benefits vary with the length of exposure, individualize the extended use of estrogen solely to augment treatment for depression. Because vasomotor symptoms may recur when HRT is discontinued,15 we recommend that women make an informed decision in consultation with a gynecologist or primary care physician.

Antidepressants that have serotonergic activity—such as SSRIs and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs)—appear most promising for treating comorbid depressive and vasomotor symptoms. If a patient has had a good response to an antidepressant in the past, consider starting with that medication.

Common antidepressant side effects are difficult to assess in perimenopausal patients with MDD because the symptoms attributed to antidepressant side effects—such as low libido, sleep disturbance, and weight changes—also can be caused by mood disorders and hormonal changes. Therefore, inquire about these symptoms when you initiate antidepressant therapy and at follow-up assessments.

Psychotherapy. We recommend that all women who present with perimenopausal depression receive information about psychotherapy. Psychotherapy alone often is adequate for mild depression, and adding psychotherapy to antidepressant treatment usually enhances recovery from moderate and severe depression episodes. In addition, patients who engage in psychotherapy for depression may have a lower rate of relapse.24

Individual psychotherapy can help patients with perimenopausal depression:

- accept this life transition

- recognize the benefits of menopause, such as no need for contraception

- develop awareness of personal potential in the years ahead.

Because depression often occurs in an interpersonal context, consider including family members in psychotherapy to improve the patient’s interpersonal support.

Integrative therapies. A full evaluation and consideration of standard treatment options is indicated for all women with MDD. Integrative medicine appeals to many patients but has not been sufficiently studied for perimenopausal depression. Supplemental omega-3 fatty acids and folate are reasonable adjuncts to the treatment of MDD25-27 and deserve study in perimenopausal MDD.

- Greene Climacteric Scale. www.menopausematters.co.uk/greenescale.php.

- Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology. www.idsqids.org.

- National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine. National Institutes of Health. http://nccam.nih.gov.

Drug brand names

- Citalopram • Celexa

- Duloxetine • Cymbalta

- Escitalopram • Lexapro

- Estradiol • various

- Eszopiclone • Lunesta

- Fluoxetine • Prozac

- Gabapentin • Neurontin

- Medroxyprogesterone • Provera

- Mirtazapine • Remeron

- Paroxetine • Paxil

- Sertraline • Zoloft

- Venlafaxine • Effexor

- Zolpidem • Ambien

Disclosures

Dr. Brandon and Dr. Shivakumar report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Dr. Freeman receives research support from GlaxoSmithKline, Forest Pharmaceuticals, and Eli Lilly and Company. She was associate professor of psychiatry at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center at Dallas when this article was written and is now on the faculty at Harvard Medical School and Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston.

1. Schmidt PJ, Rubinow DR. Reproductive ageing, sex steroids and depression. J Br Menopause Soc 2006;12(4):178-85.

2. Rasgon N, Shelton S, Halbreich U. Perimenopausal mental disorders: epidemiology and phenomenology. CNS Spectr 2005;10(6):471-8.

3. Greene JG. Constructing a standard climacteric scale. Maturitas 1998;29(1):25-31.

4. Rush AJ, Trivedi MH, Ibrahim HM, et al. The 16-Item Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology (QIDS), clinician rating (QIDS-C), and self-report (QIDS-SR): a psychometric evaluation in patients with chronic major depression. Biol Psychiatry 2003;54(5):573-83.Erratum in: Biol Psychiatry. 2003;54(5):585.

5. Feld J, Halbreich U, Karkun S. The association of perimenopausal mood disorders with other reproductive-related disorders. CNS Spectr 2005;10(6):461-70.

6. Avis NE, Stellato R, Crawford S, et al. Is there a menopausal syndrome? Menopausal status and symptoms across racial/ethnic groups. Soc Sci Med 2001;52:345-56.

7. Campbell S, Whitehead M. Oestrogen therapy and the menopause syndrome. Clin Obstet Gynecol 1977;4:31-47.

8. Schmidt PJ, Rubinow DR. Menopause-related affective disorders: a justification for further study. Am J Psychiatry 1991;48:844-52.

9. Soares CN. Menopausal transition and depression: who is at risk and how to treat it? Expert Rev Neurother 2007;7(10):1285-93.

10. Prior JC. The complex endocrinology of menopausal transition. Endocrinol Rev 1998;19:397-428.

11. Rasgon N, Altshuler LL, Fairbanks LA, et al. Estrogen replacement therapy in the treatment of major depressive disorder in perimenopausal women. J Clin Psychiatry 2002;63(suppl):45-8.

12. Altshuler LL, Cohen LS, Moline ML, et al. The Expert Consensus Guideline Series. Treatment of depression in women. Postgrad Med 2001 Mar;(Spec No):1-107.

13. The Women’s Health Initiative Steering Committee. Effects of conjugated equine estrogen in postmenopausal women with hysterectomy: The Women’s Health Initiative randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2004;291:1701-12.

14. Writing Group for the Women’s Health Initiative Investigators. Risks and benefits of estrogen plus progestin in healthy postmenopausal women: principal results from the Women’s Health Initiative randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2002;288:321-33.

15. Ockene JK, Barad DH, Cochrane BB, et al. Symptom experience after discontinuing use of estrogen plus progestin. JAMA 2005;294:183-93.

16. Shumaker SA, Legault C, Kuller L, et al. Conjugated equine estrogens and incidence of probable dementia and mild cognitive impairment in postmenopausal women: Women’s Health Initiative Memory Study. JAMA 2004;291:2947-58.

17. Shumaker SA, Legault C, Rapp SR. Estrogen plus progestin and the incidence of dementia and mild cognitive impairment in postmenopausal women. The Women’s Health Initiative Memory Study: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2003;289:2651-62.

18. FDA approves new labeling and provides new advice to postmenopausal women who use or who are considering using estrogen and estrogen with progestin [FDA Fact Sheet January 8, 2003]. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/oc/factsheets/WHI.html. Accessed September 11, 2008.

19. Soares CN, Arsenio H, Joffe H, et al. Escitalopram versus ethinyl estradiol and norethindrone acetate for symptomatic peri- and postmenopausal women: impact on depression, vasomotor symptoms, sleep, and quality of life. Menopause 2006;13(5):780-6.

20. Cohen LS, Soares CN, Joffe H. Diagnosis and management of mood disorders during the menopausal transition. Am J Med 2005;118(suppl 12B):93-7.

21. Kahn DA, Moline ML, Ross RW, et al. Depression during the transition to menopause: a guide for patients and families. Postgrad Med 2001 Mar;(Spec No):110-1.

22. Alder J, Besken KE, Armbruster U, et al. Cognitive-behavioural group intervention for climacteric syndrome. Psychother Psychosom 2006;75(5):298-303.

23. Soares CN, Almeida OP, Joffe H, Cohen LS. Efficacy of estradiol for the treatment of depressive disorders in perimenopausal women: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2001;58(6):529-34.

24. Otto MW, Smits JA, Reese HE. Combined psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy for mood and anxiety disorders in adults: review and analysis. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice 2005;12:72-86.

25. Coppen A, Bailey J. Enhancement of the antidepressant action of fluoxetine by folic acid: a randomized, placebo controlled trial. J Affect Disord 2000;60:121-30.

26. Freeman MP, Hibbeln JR, Wisner KL, et al. Omega-3 fatty acids: evidence basis for treatment and future research in psychiatry [American Psychiatric Association subcommittee report]. J Clin Psychiatry 2006;67:1954-67.

27. Otto MW, Church TS, Craft LL, et al. Exercise for mood and anxiety disorders. J Clin Psychiatry 2007;68:669-76.

Symptoms of perimenopausal depression are not inherently different from those of depression diagnosed at any other time in life, but they present in a unique context:

- Hormonal fluctuations may persist for a long duration.

- Women experiencing hormonal fluctuations may be vulnerable to mood problems.

- Psychosocial/psychodynamic stressors often complicate this life transition.

Managing perimenopausal depression has become more complicated since the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) studies found fewer benefits and greater risks with hormone replacement therapy (HRT) than had been perceived. This article discusses the clinical presentation of perimenopausal depression, its risk factors, and treatment options in post-WHI psychiatric practice.

Who is at risk?

Perimenopausal depression is diagnosed when onset of major depressive disorder (MDD) is associated with menstrual cycle irregularity and/or somatic symptoms of the menopausal transition.1 Diagnosis is based on the overall clinical picture, and treatment requires a thoughtful exploration of the complex relationship between hormonal function and mood regulation.

Presentation. For many women, perimenopause is characterized by mild to severe vasomotor, cognitive, and mood symptoms (Table 1). Thus, in your workup of depression in midlife women, document somatic symptoms—such as hot flushes, vaginal dryness, and incontinence—and affective/behavioral symp toms such as mood and sleep disturbances.

Table 1

Vasomotor, cognitive, and mood symptoms of perimenopause

| Vasomotor | Cognitive and mood |

|---|---|

| Hot flushes | Decreased concentration |

| Sweating | Anxiety |

| Heart palpitations | Irritability |

| Painful intercourse | Mood lability |

| Vaginal dryness and discomfort | Memory difficulty |

| Sleep disruption | |

| Headache |

Explore psychiatric and medical histories of your patient and her close relatives. Ask about depression, dysthymia, hypomania, or mood fluctuations around hormonal events such as menses, pregnancy, postpartum, or starting/stopping oral contraceptives. In the differential diagnosis, consider:

- Is low mood temporally connected with hot flushes and disturbed sleep?

- Is low mood secondary to stressful life events?

- Does the patient have another medical illness (such as thyroid disorder) with symptoms similar to depression?

- Is low mood secondary to anxiety or another psychiatric disorder?

Screening. Menopause is considered to have been reached after 12 months of amenorrhea not due to another cause. Median ages for this transition in the United States are 47.5 for perimenopause and 51 for menopause, with an average of 8 years between regular cycles and amenorrhea.2 Therefore, begin talking with women about perimenopausal symptoms when they turn 40.

Evidence supports screening perimenopausal women for depressive symptoms even when their primary complaints are vasomotor. The Greene Climacteric Scale3 is convenient for quantifying and monitoring perimenopausal symptoms. It includes depressive symptoms plus physical and cognitive markers. The Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology—Self Report (QIDS-SR)4 questionnaire:

- takes minutes to complete

- is easy to score

- quantitates the number and severity of depressive symptoms (see Related Resources).

Psychosocial factors can predict depression at any time in life, but some are specific to the menopausal transition (Table 2).5 The “empty nest syndrome,” for example, is often used to explain depressive symptoms in midlife mothers, but no evidence links mood lability with the maturation and departure of children. What may be more stressing for women is supporting adolescents/young adults in their exit to independence while caring for aging parents.

Table 2

Risk factors for depression in women

| Predictive over lifetime | High risk during menopausal transition |

|---|---|

| History of depression | History of PMS, perinatal depression, mood symptoms associated with contraceptives |

| Family history of affective disorders | Premature or surgical menopause |

| Insomnia | Lengthy menopausal transition (≥27 months) |

| Reduced physical activities | Persistent and/or severe vasomotor symptoms |

| Weight gain | Negative attitudes toward menopause and aging |

| Less education | |

| Perceived lower economic status | |

| Perceived lower social support | |

| Perceived lower health status | |

| Smoking | |

| Stressful life events | |

| History of trauma | |

| Marital dissatisfaction | |

| PMS: Premenstrual syndrome | |

Sociocultural beliefs about sexuality and menopause may play a role in how your patient experiences and reports her symptoms. In some cultures, menopause elevates a woman’s social status and is associated with increased respect and authority. In others, such as Western societies that emphasize youth and beauty, women may view menopause and its physical changes in a negative light.6

Therefore, give careful attention to the psychosocial context of menopause to your patient and the social resources available to her. Questions to ask include:

- Has your lifestyle changed recently?

- Have your husband, family members, or close friends noticed any changes in your functioning?

- Is there anyone in your life that you feel comfortable confiding in?

Explaining the complexity of this life transition may ease her anxiety by normalizing her experience, helping her understand her symptoms, and validating her distress.

What might be the cause?

Although the exact pathophysiology of perimenopausal depression is unknown, hormonal changes,7 general health, the experience of menopause,8 and the psychosocial context2 likely work together to increase vulnerability for depressive symptoms (Figure).

Figure Biopsychosocial milieu of depression during perimenopauseHormonal fluctuation. The estrogen withdrawal theory7 explains depressive symptoms as resulting from a sustained decline in ovarian estrogen in tandem with spiking secretions of follicle-stimulating hormone by the pituitary. The finding that women with surgical menopause have a higher incidence of depressive symptoms than women with natural menopause supports this hypothesis.

Mood disorders occur across various female reproductive events, and increased risk appears to be associated with fluctuating gonadal hormones. Thus, declining estrogen may be less causative of perimenopausal depression than extreme fluctuations in estradiol activity.9,10

Estrogen interacts with dopamine, norepinephrine, beta-endorphin, and serotonin metabolism. In particular, estrogen facilitates serotonin delivery to neurons across the brain. These findings—and the success of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) in treating mood disorders—support the theory that fluctuating estrogen affects the serotonergic system and may cause depressive symptoms.

‘Domino theory.’ Others have hypothesized that depressive symptoms are the secondhand result of somatic symptoms of perimenopause. In a “domino effect,” hot flushes and night sweats disrupt women’s sleep, bringing fatigue and impaired daytime concentration, which lead to irritability and feelings of being overwhelmed.8

This theory, which incorporates perimenopausal hormone changes, is supported by elevated levels of depression in women who report frequent and intense vasomotor symptoms persisting >27 months.2

The psychosocial theory suggests that depression results from increased stress or adverse events.2 Midlife women with depressive symptoms report many possible sources of stress:

- demanding jobs

- family responsibilities

- dual demands of career and family

- little time for self

- poverty or employment stressors

- not enough sleep

- changing social relationships.

Negative interpretations of aging or the menopausal transition also have been implicated in cross-cultural studies.6 The predictive nature of psychosocial issues for depression during perimenopause supports this theory.

Evidence-based treatment

HRT. Research and clinical reports suggest that estrogen may have antidepressant effects, either alone or as an adjunct to antidepressant medication.11 Before the WHI studies, expert consensus guidelines on treating depression in women recommended HRT as first-line treatment for patients experiencing a first lifetime onset of mild to moderate depression during perimenopause.12 WHI findings since 2002 that associated HRT with increased risk of stroke, deep vein thrombosis, and pulmonary embolism—without clear protection against coronary heart disease or cognitive decline—have left HRT a controversial option for treating perimenopausal depression. In the WHI trials:

- 10,739 postmenopausal women age 50 to 79 without a uterus received unopposed conjugated equine estrogens, 0.625 mg/d, or placebo for an average 6.8 years.13

- 16,608 postmenopausal women age 50 to 79 with an intact uterus received combination HRT (conjugated equine estrogens, 0.625 mg/d, plus 2.5 mg of medroxyprogesterone), or placebo for an average 5.6 years.14

The study using combination HRT found increased risks of breast cancer, ischemic stroke, blood clots, and coronary heart disease.15 A follow-up study showed that vasomotor symptoms returned in more than one-half the women after they stopped using combination HRT.15

A companion WHI trial found that estrogen, 0.625 mg/d—given unopposed or with a progestin—did not prevent cognitive decline in women age 65 to 79 and may have been associated with a slightly greater risk of probable dementia.16,17

The FDA recommends that women who want to use HRT to control menopausal symptoms use the lowest effective dose for the shortest time necessary.18

Antidepressants. SSRIs may be more useful than estrogen for producing MDD remission in perimenopausal women.19 SSRIs and other psychotropics may reduce perimenopausal vasomotor symptoms in addition to addressing depressive symptoms (Table 3). When choosing antidepressant therapy, consider the patient’s dominant presenting perimenopausal symptoms and side effects associated with treatment.20

Table 3

Nonhormone medications for perimenopausal depression: Evidence-based dosages and target symptoms

| Medication | Dosage effective for perimenopausal depression | Symptoms assessed |

|---|---|---|

| SSRIs | ||

| Citaloprama | 40 to 60 mg | Depressive and vasomotor |

| Escitalopramb,c | 5 to 20 mg | Depressive and vasomotor |

| Fluoxetined | 20 to 40 mg | Depressive and vasomotor |

| Paroxetinee,f | 12.5 or 25 mg | Depressive and vasomotor |

| Sertralineg | 100 mg | Depressive and vasomotor |

| Other antidepressants | ||

| Duloxetineh | 60 to 120 mg | Depressive and vasomotor |

| Venlafaxinei | 75 to 225 mg | Depressive and vasomotor |

| Mirtazapinej | 30 to 60 mg | Severe depressive symptoms; used as an adjunct to estrogen |

| Hypnotics | ||

| Eszopiclonek | 3 mg | Depressive and vasomotor; insomnia |

| Zolpideml | 5 to 10 mg | Insomnia |

| Anticonvulsant | ||

| Gabapentinm | 300 to 900 mg | Vasomotor |

| SSRIs: selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors | ||

| Source: Reference Citations | ||

Nonpharmacologic interventions are viable options for women who are reluctant to begin HRT or psychotropics.

Psychotherapy. Interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT) and cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) have been recommended to address psychosocial elements of perimenopausal mood lability.21 For women with climacteric depression, IPT focuses on role transitions, loss, and interpersonal support, whereas CBT focuses on identifying and altering negative thoughts and beliefs.

Although no randomized trials have examined psychotherapies for perimenopausal depression, a pilot open trial provided group CBT—psychoeducation, group discussion, and coping skills training—to 30 women with climacteric symptoms. Anxiety, depression, partnership relations, overall sexuality, hot flushes, and cardiac complaints improved significantly, based on pre- and post-intervention surveys. Sexual satisfaction and the stressfulness of menopausal symptoms did not change.22

Integrative medicine. Plant-based substances and herbal remedies such as phytoestrogens, red-clover isoflavones, black cohosh, and evening primrose oil have been included in a few research investigations, and the evidence is equivocal. Because of potential interactions between alternative therapies and medications, inquire about their use. Although a comprehensive review of integrative medicine for perimenopausal symptoms is beyond the scope of this article, see suggested readings (Box).

- Albertazzi P. Non-estrogenic approaches for the treatment of climacteric symptoms. Climacteric 2007;10(suppl 2):115-20.

- Blair YA, Gold EB, Zhang G, et al. Use of complementary and alternative medicine during the menopause transition: longitudinal results from the Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation. Menopause 2008;15:32-43.

- Freeman MP, Helgason C, Hill RA. Selected integrative medicine treatments for depression: considerations for women. J Am Med Womens Assoc 2004;59(3):216-24.

- Mischoulon D. Update and critique of natural remedies as antidepressant treatments. Psychiatr Clin North Am 2007;30:51-68.

- Thachil AF, Mohan R, Bhugra D. The evidence base of complementary and alternative therapies in depression. J Affect Disord 2007;97:23-35.

- Tremblay A, Sheeran L, Aranda SK. Psychoeducational interventions to alleviate hot flashes: a systematic review. J North Am Menopause Soc 2008;15:193-202.

Clinical recommendations

Explore options with your patient; discuss side effects, risks, and expected minimum duration of treatment. Antidepressants, hormonal therapies, psychotherapy, and complementary and alternative treatments each might have a role in managing perimenopausal depression. A patient’s preferences, psychiatric history, and depression severity help determine which options to consider and in what order. How she responded to past treatments also can help you individualize a plan.

HRT may be appropriate for women who express a preference for HRT, have responded well to past hormone therapy, and have no personal history or high-risk factors for breast cancer. Based on the WHI findings, we consider a history of breast cancer in the patient or a first- or second-degree relative a contraindication to HRT.

Estrogen can be used alone or with an antidepressant. Studies support 17β-estradiol, 0.1 to 0.3 mg/d, for 8 to 12 weeks.11,23 Concomitant progesterone may be indicated to offset the effects of unopposed estrogen in women with an intact uterus. This option calls for an informed discussion with the patient about risks and benefits.

No data support long-term use of estrogen for recurrent or chronic depression. Because HRT’s risks and benefits vary with the length of exposure, individualize the extended use of estrogen solely to augment treatment for depression. Because vasomotor symptoms may recur when HRT is discontinued,15 we recommend that women make an informed decision in consultation with a gynecologist or primary care physician.

Antidepressants that have serotonergic activity—such as SSRIs and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs)—appear most promising for treating comorbid depressive and vasomotor symptoms. If a patient has had a good response to an antidepressant in the past, consider starting with that medication.

Common antidepressant side effects are difficult to assess in perimenopausal patients with MDD because the symptoms attributed to antidepressant side effects—such as low libido, sleep disturbance, and weight changes—also can be caused by mood disorders and hormonal changes. Therefore, inquire about these symptoms when you initiate antidepressant therapy and at follow-up assessments.

Psychotherapy. We recommend that all women who present with perimenopausal depression receive information about psychotherapy. Psychotherapy alone often is adequate for mild depression, and adding psychotherapy to antidepressant treatment usually enhances recovery from moderate and severe depression episodes. In addition, patients who engage in psychotherapy for depression may have a lower rate of relapse.24

Individual psychotherapy can help patients with perimenopausal depression:

- accept this life transition

- recognize the benefits of menopause, such as no need for contraception

- develop awareness of personal potential in the years ahead.

Because depression often occurs in an interpersonal context, consider including family members in psychotherapy to improve the patient’s interpersonal support.

Integrative therapies. A full evaluation and consideration of standard treatment options is indicated for all women with MDD. Integrative medicine appeals to many patients but has not been sufficiently studied for perimenopausal depression. Supplemental omega-3 fatty acids and folate are reasonable adjuncts to the treatment of MDD25-27 and deserve study in perimenopausal MDD.

- Greene Climacteric Scale. www.menopausematters.co.uk/greenescale.php.

- Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology. www.idsqids.org.

- National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine. National Institutes of Health. http://nccam.nih.gov.

Drug brand names

- Citalopram • Celexa

- Duloxetine • Cymbalta

- Escitalopram • Lexapro

- Estradiol • various

- Eszopiclone • Lunesta

- Fluoxetine • Prozac

- Gabapentin • Neurontin

- Medroxyprogesterone • Provera

- Mirtazapine • Remeron

- Paroxetine • Paxil

- Sertraline • Zoloft

- Venlafaxine • Effexor

- Zolpidem • Ambien

Disclosures

Dr. Brandon and Dr. Shivakumar report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Dr. Freeman receives research support from GlaxoSmithKline, Forest Pharmaceuticals, and Eli Lilly and Company. She was associate professor of psychiatry at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center at Dallas when this article was written and is now on the faculty at Harvard Medical School and Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston.

Symptoms of perimenopausal depression are not inherently different from those of depression diagnosed at any other time in life, but they present in a unique context:

- Hormonal fluctuations may persist for a long duration.

- Women experiencing hormonal fluctuations may be vulnerable to mood problems.

- Psychosocial/psychodynamic stressors often complicate this life transition.

Managing perimenopausal depression has become more complicated since the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) studies found fewer benefits and greater risks with hormone replacement therapy (HRT) than had been perceived. This article discusses the clinical presentation of perimenopausal depression, its risk factors, and treatment options in post-WHI psychiatric practice.

Who is at risk?

Perimenopausal depression is diagnosed when onset of major depressive disorder (MDD) is associated with menstrual cycle irregularity and/or somatic symptoms of the menopausal transition.1 Diagnosis is based on the overall clinical picture, and treatment requires a thoughtful exploration of the complex relationship between hormonal function and mood regulation.

Presentation. For many women, perimenopause is characterized by mild to severe vasomotor, cognitive, and mood symptoms (Table 1). Thus, in your workup of depression in midlife women, document somatic symptoms—such as hot flushes, vaginal dryness, and incontinence—and affective/behavioral symp toms such as mood and sleep disturbances.

Table 1

Vasomotor, cognitive, and mood symptoms of perimenopause

| Vasomotor | Cognitive and mood |

|---|---|

| Hot flushes | Decreased concentration |

| Sweating | Anxiety |

| Heart palpitations | Irritability |

| Painful intercourse | Mood lability |

| Vaginal dryness and discomfort | Memory difficulty |

| Sleep disruption | |

| Headache |

Explore psychiatric and medical histories of your patient and her close relatives. Ask about depression, dysthymia, hypomania, or mood fluctuations around hormonal events such as menses, pregnancy, postpartum, or starting/stopping oral contraceptives. In the differential diagnosis, consider:

- Is low mood temporally connected with hot flushes and disturbed sleep?

- Is low mood secondary to stressful life events?

- Does the patient have another medical illness (such as thyroid disorder) with symptoms similar to depression?

- Is low mood secondary to anxiety or another psychiatric disorder?

Screening. Menopause is considered to have been reached after 12 months of amenorrhea not due to another cause. Median ages for this transition in the United States are 47.5 for perimenopause and 51 for menopause, with an average of 8 years between regular cycles and amenorrhea.2 Therefore, begin talking with women about perimenopausal symptoms when they turn 40.

Evidence supports screening perimenopausal women for depressive symptoms even when their primary complaints are vasomotor. The Greene Climacteric Scale3 is convenient for quantifying and monitoring perimenopausal symptoms. It includes depressive symptoms plus physical and cognitive markers. The Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology—Self Report (QIDS-SR)4 questionnaire:

- takes minutes to complete

- is easy to score

- quantitates the number and severity of depressive symptoms (see Related Resources).

Psychosocial factors can predict depression at any time in life, but some are specific to the menopausal transition (Table 2).5 The “empty nest syndrome,” for example, is often used to explain depressive symptoms in midlife mothers, but no evidence links mood lability with the maturation and departure of children. What may be more stressing for women is supporting adolescents/young adults in their exit to independence while caring for aging parents.

Table 2

Risk factors for depression in women

| Predictive over lifetime | High risk during menopausal transition |

|---|---|

| History of depression | History of PMS, perinatal depression, mood symptoms associated with contraceptives |

| Family history of affective disorders | Premature or surgical menopause |

| Insomnia | Lengthy menopausal transition (≥27 months) |

| Reduced physical activities | Persistent and/or severe vasomotor symptoms |

| Weight gain | Negative attitudes toward menopause and aging |

| Less education | |

| Perceived lower economic status | |

| Perceived lower social support | |

| Perceived lower health status | |

| Smoking | |

| Stressful life events | |

| History of trauma | |

| Marital dissatisfaction | |

| PMS: Premenstrual syndrome | |

Sociocultural beliefs about sexuality and menopause may play a role in how your patient experiences and reports her symptoms. In some cultures, menopause elevates a woman’s social status and is associated with increased respect and authority. In others, such as Western societies that emphasize youth and beauty, women may view menopause and its physical changes in a negative light.6

Therefore, give careful attention to the psychosocial context of menopause to your patient and the social resources available to her. Questions to ask include:

- Has your lifestyle changed recently?

- Have your husband, family members, or close friends noticed any changes in your functioning?

- Is there anyone in your life that you feel comfortable confiding in?

Explaining the complexity of this life transition may ease her anxiety by normalizing her experience, helping her understand her symptoms, and validating her distress.

What might be the cause?

Although the exact pathophysiology of perimenopausal depression is unknown, hormonal changes,7 general health, the experience of menopause,8 and the psychosocial context2 likely work together to increase vulnerability for depressive symptoms (Figure).

Figure Biopsychosocial milieu of depression during perimenopauseHormonal fluctuation. The estrogen withdrawal theory7 explains depressive symptoms as resulting from a sustained decline in ovarian estrogen in tandem with spiking secretions of follicle-stimulating hormone by the pituitary. The finding that women with surgical menopause have a higher incidence of depressive symptoms than women with natural menopause supports this hypothesis.

Mood disorders occur across various female reproductive events, and increased risk appears to be associated with fluctuating gonadal hormones. Thus, declining estrogen may be less causative of perimenopausal depression than extreme fluctuations in estradiol activity.9,10

Estrogen interacts with dopamine, norepinephrine, beta-endorphin, and serotonin metabolism. In particular, estrogen facilitates serotonin delivery to neurons across the brain. These findings—and the success of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) in treating mood disorders—support the theory that fluctuating estrogen affects the serotonergic system and may cause depressive symptoms.

‘Domino theory.’ Others have hypothesized that depressive symptoms are the secondhand result of somatic symptoms of perimenopause. In a “domino effect,” hot flushes and night sweats disrupt women’s sleep, bringing fatigue and impaired daytime concentration, which lead to irritability and feelings of being overwhelmed.8

This theory, which incorporates perimenopausal hormone changes, is supported by elevated levels of depression in women who report frequent and intense vasomotor symptoms persisting >27 months.2

The psychosocial theory suggests that depression results from increased stress or adverse events.2 Midlife women with depressive symptoms report many possible sources of stress:

- demanding jobs

- family responsibilities

- dual demands of career and family

- little time for self

- poverty or employment stressors

- not enough sleep

- changing social relationships.

Negative interpretations of aging or the menopausal transition also have been implicated in cross-cultural studies.6 The predictive nature of psychosocial issues for depression during perimenopause supports this theory.

Evidence-based treatment

HRT. Research and clinical reports suggest that estrogen may have antidepressant effects, either alone or as an adjunct to antidepressant medication.11 Before the WHI studies, expert consensus guidelines on treating depression in women recommended HRT as first-line treatment for patients experiencing a first lifetime onset of mild to moderate depression during perimenopause.12 WHI findings since 2002 that associated HRT with increased risk of stroke, deep vein thrombosis, and pulmonary embolism—without clear protection against coronary heart disease or cognitive decline—have left HRT a controversial option for treating perimenopausal depression. In the WHI trials:

- 10,739 postmenopausal women age 50 to 79 without a uterus received unopposed conjugated equine estrogens, 0.625 mg/d, or placebo for an average 6.8 years.13

- 16,608 postmenopausal women age 50 to 79 with an intact uterus received combination HRT (conjugated equine estrogens, 0.625 mg/d, plus 2.5 mg of medroxyprogesterone), or placebo for an average 5.6 years.14

The study using combination HRT found increased risks of breast cancer, ischemic stroke, blood clots, and coronary heart disease.15 A follow-up study showed that vasomotor symptoms returned in more than one-half the women after they stopped using combination HRT.15

A companion WHI trial found that estrogen, 0.625 mg/d—given unopposed or with a progestin—did not prevent cognitive decline in women age 65 to 79 and may have been associated with a slightly greater risk of probable dementia.16,17

The FDA recommends that women who want to use HRT to control menopausal symptoms use the lowest effective dose for the shortest time necessary.18

Antidepressants. SSRIs may be more useful than estrogen for producing MDD remission in perimenopausal women.19 SSRIs and other psychotropics may reduce perimenopausal vasomotor symptoms in addition to addressing depressive symptoms (Table 3). When choosing antidepressant therapy, consider the patient’s dominant presenting perimenopausal symptoms and side effects associated with treatment.20

Table 3

Nonhormone medications for perimenopausal depression: Evidence-based dosages and target symptoms

| Medication | Dosage effective for perimenopausal depression | Symptoms assessed |

|---|---|---|

| SSRIs | ||

| Citaloprama | 40 to 60 mg | Depressive and vasomotor |

| Escitalopramb,c | 5 to 20 mg | Depressive and vasomotor |

| Fluoxetined | 20 to 40 mg | Depressive and vasomotor |

| Paroxetinee,f | 12.5 or 25 mg | Depressive and vasomotor |

| Sertralineg | 100 mg | Depressive and vasomotor |

| Other antidepressants | ||

| Duloxetineh | 60 to 120 mg | Depressive and vasomotor |

| Venlafaxinei | 75 to 225 mg | Depressive and vasomotor |

| Mirtazapinej | 30 to 60 mg | Severe depressive symptoms; used as an adjunct to estrogen |

| Hypnotics | ||

| Eszopiclonek | 3 mg | Depressive and vasomotor; insomnia |

| Zolpideml | 5 to 10 mg | Insomnia |

| Anticonvulsant | ||

| Gabapentinm | 300 to 900 mg | Vasomotor |

| SSRIs: selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors | ||

| Source: Reference Citations | ||

Nonpharmacologic interventions are viable options for women who are reluctant to begin HRT or psychotropics.

Psychotherapy. Interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT) and cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) have been recommended to address psychosocial elements of perimenopausal mood lability.21 For women with climacteric depression, IPT focuses on role transitions, loss, and interpersonal support, whereas CBT focuses on identifying and altering negative thoughts and beliefs.

Although no randomized trials have examined psychotherapies for perimenopausal depression, a pilot open trial provided group CBT—psychoeducation, group discussion, and coping skills training—to 30 women with climacteric symptoms. Anxiety, depression, partnership relations, overall sexuality, hot flushes, and cardiac complaints improved significantly, based on pre- and post-intervention surveys. Sexual satisfaction and the stressfulness of menopausal symptoms did not change.22

Integrative medicine. Plant-based substances and herbal remedies such as phytoestrogens, red-clover isoflavones, black cohosh, and evening primrose oil have been included in a few research investigations, and the evidence is equivocal. Because of potential interactions between alternative therapies and medications, inquire about their use. Although a comprehensive review of integrative medicine for perimenopausal symptoms is beyond the scope of this article, see suggested readings (Box).

- Albertazzi P. Non-estrogenic approaches for the treatment of climacteric symptoms. Climacteric 2007;10(suppl 2):115-20.

- Blair YA, Gold EB, Zhang G, et al. Use of complementary and alternative medicine during the menopause transition: longitudinal results from the Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation. Menopause 2008;15:32-43.

- Freeman MP, Helgason C, Hill RA. Selected integrative medicine treatments for depression: considerations for women. J Am Med Womens Assoc 2004;59(3):216-24.

- Mischoulon D. Update and critique of natural remedies as antidepressant treatments. Psychiatr Clin North Am 2007;30:51-68.

- Thachil AF, Mohan R, Bhugra D. The evidence base of complementary and alternative therapies in depression. J Affect Disord 2007;97:23-35.

- Tremblay A, Sheeran L, Aranda SK. Psychoeducational interventions to alleviate hot flashes: a systematic review. J North Am Menopause Soc 2008;15:193-202.

Clinical recommendations

Explore options with your patient; discuss side effects, risks, and expected minimum duration of treatment. Antidepressants, hormonal therapies, psychotherapy, and complementary and alternative treatments each might have a role in managing perimenopausal depression. A patient’s preferences, psychiatric history, and depression severity help determine which options to consider and in what order. How she responded to past treatments also can help you individualize a plan.

HRT may be appropriate for women who express a preference for HRT, have responded well to past hormone therapy, and have no personal history or high-risk factors for breast cancer. Based on the WHI findings, we consider a history of breast cancer in the patient or a first- or second-degree relative a contraindication to HRT.

Estrogen can be used alone or with an antidepressant. Studies support 17β-estradiol, 0.1 to 0.3 mg/d, for 8 to 12 weeks.11,23 Concomitant progesterone may be indicated to offset the effects of unopposed estrogen in women with an intact uterus. This option calls for an informed discussion with the patient about risks and benefits.

No data support long-term use of estrogen for recurrent or chronic depression. Because HRT’s risks and benefits vary with the length of exposure, individualize the extended use of estrogen solely to augment treatment for depression. Because vasomotor symptoms may recur when HRT is discontinued,15 we recommend that women make an informed decision in consultation with a gynecologist or primary care physician.

Antidepressants that have serotonergic activity—such as SSRIs and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs)—appear most promising for treating comorbid depressive and vasomotor symptoms. If a patient has had a good response to an antidepressant in the past, consider starting with that medication.

Common antidepressant side effects are difficult to assess in perimenopausal patients with MDD because the symptoms attributed to antidepressant side effects—such as low libido, sleep disturbance, and weight changes—also can be caused by mood disorders and hormonal changes. Therefore, inquire about these symptoms when you initiate antidepressant therapy and at follow-up assessments.

Psychotherapy. We recommend that all women who present with perimenopausal depression receive information about psychotherapy. Psychotherapy alone often is adequate for mild depression, and adding psychotherapy to antidepressant treatment usually enhances recovery from moderate and severe depression episodes. In addition, patients who engage in psychotherapy for depression may have a lower rate of relapse.24

Individual psychotherapy can help patients with perimenopausal depression:

- accept this life transition

- recognize the benefits of menopause, such as no need for contraception

- develop awareness of personal potential in the years ahead.

Because depression often occurs in an interpersonal context, consider including family members in psychotherapy to improve the patient’s interpersonal support.

Integrative therapies. A full evaluation and consideration of standard treatment options is indicated for all women with MDD. Integrative medicine appeals to many patients but has not been sufficiently studied for perimenopausal depression. Supplemental omega-3 fatty acids and folate are reasonable adjuncts to the treatment of MDD25-27 and deserve study in perimenopausal MDD.

- Greene Climacteric Scale. www.menopausematters.co.uk/greenescale.php.

- Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology. www.idsqids.org.

- National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine. National Institutes of Health. http://nccam.nih.gov.

Drug brand names

- Citalopram • Celexa

- Duloxetine • Cymbalta

- Escitalopram • Lexapro

- Estradiol • various

- Eszopiclone • Lunesta

- Fluoxetine • Prozac

- Gabapentin • Neurontin

- Medroxyprogesterone • Provera

- Mirtazapine • Remeron

- Paroxetine • Paxil

- Sertraline • Zoloft

- Venlafaxine • Effexor

- Zolpidem • Ambien

Disclosures

Dr. Brandon and Dr. Shivakumar report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Dr. Freeman receives research support from GlaxoSmithKline, Forest Pharmaceuticals, and Eli Lilly and Company. She was associate professor of psychiatry at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center at Dallas when this article was written and is now on the faculty at Harvard Medical School and Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston.

1. Schmidt PJ, Rubinow DR. Reproductive ageing, sex steroids and depression. J Br Menopause Soc 2006;12(4):178-85.

2. Rasgon N, Shelton S, Halbreich U. Perimenopausal mental disorders: epidemiology and phenomenology. CNS Spectr 2005;10(6):471-8.

3. Greene JG. Constructing a standard climacteric scale. Maturitas 1998;29(1):25-31.

4. Rush AJ, Trivedi MH, Ibrahim HM, et al. The 16-Item Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology (QIDS), clinician rating (QIDS-C), and self-report (QIDS-SR): a psychometric evaluation in patients with chronic major depression. Biol Psychiatry 2003;54(5):573-83.Erratum in: Biol Psychiatry. 2003;54(5):585.

5. Feld J, Halbreich U, Karkun S. The association of perimenopausal mood disorders with other reproductive-related disorders. CNS Spectr 2005;10(6):461-70.

6. Avis NE, Stellato R, Crawford S, et al. Is there a menopausal syndrome? Menopausal status and symptoms across racial/ethnic groups. Soc Sci Med 2001;52:345-56.

7. Campbell S, Whitehead M. Oestrogen therapy and the menopause syndrome. Clin Obstet Gynecol 1977;4:31-47.

8. Schmidt PJ, Rubinow DR. Menopause-related affective disorders: a justification for further study. Am J Psychiatry 1991;48:844-52.

9. Soares CN. Menopausal transition and depression: who is at risk and how to treat it? Expert Rev Neurother 2007;7(10):1285-93.

10. Prior JC. The complex endocrinology of menopausal transition. Endocrinol Rev 1998;19:397-428.

11. Rasgon N, Altshuler LL, Fairbanks LA, et al. Estrogen replacement therapy in the treatment of major depressive disorder in perimenopausal women. J Clin Psychiatry 2002;63(suppl):45-8.

12. Altshuler LL, Cohen LS, Moline ML, et al. The Expert Consensus Guideline Series. Treatment of depression in women. Postgrad Med 2001 Mar;(Spec No):1-107.

13. The Women’s Health Initiative Steering Committee. Effects of conjugated equine estrogen in postmenopausal women with hysterectomy: The Women’s Health Initiative randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2004;291:1701-12.

14. Writing Group for the Women’s Health Initiative Investigators. Risks and benefits of estrogen plus progestin in healthy postmenopausal women: principal results from the Women’s Health Initiative randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2002;288:321-33.

15. Ockene JK, Barad DH, Cochrane BB, et al. Symptom experience after discontinuing use of estrogen plus progestin. JAMA 2005;294:183-93.

16. Shumaker SA, Legault C, Kuller L, et al. Conjugated equine estrogens and incidence of probable dementia and mild cognitive impairment in postmenopausal women: Women’s Health Initiative Memory Study. JAMA 2004;291:2947-58.

17. Shumaker SA, Legault C, Rapp SR. Estrogen plus progestin and the incidence of dementia and mild cognitive impairment in postmenopausal women. The Women’s Health Initiative Memory Study: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2003;289:2651-62.

18. FDA approves new labeling and provides new advice to postmenopausal women who use or who are considering using estrogen and estrogen with progestin [FDA Fact Sheet January 8, 2003]. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/oc/factsheets/WHI.html. Accessed September 11, 2008.

19. Soares CN, Arsenio H, Joffe H, et al. Escitalopram versus ethinyl estradiol and norethindrone acetate for symptomatic peri- and postmenopausal women: impact on depression, vasomotor symptoms, sleep, and quality of life. Menopause 2006;13(5):780-6.

20. Cohen LS, Soares CN, Joffe H. Diagnosis and management of mood disorders during the menopausal transition. Am J Med 2005;118(suppl 12B):93-7.

21. Kahn DA, Moline ML, Ross RW, et al. Depression during the transition to menopause: a guide for patients and families. Postgrad Med 2001 Mar;(Spec No):110-1.

22. Alder J, Besken KE, Armbruster U, et al. Cognitive-behavioural group intervention for climacteric syndrome. Psychother Psychosom 2006;75(5):298-303.

23. Soares CN, Almeida OP, Joffe H, Cohen LS. Efficacy of estradiol for the treatment of depressive disorders in perimenopausal women: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2001;58(6):529-34.

24. Otto MW, Smits JA, Reese HE. Combined psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy for mood and anxiety disorders in adults: review and analysis. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice 2005;12:72-86.

25. Coppen A, Bailey J. Enhancement of the antidepressant action of fluoxetine by folic acid: a randomized, placebo controlled trial. J Affect Disord 2000;60:121-30.

26. Freeman MP, Hibbeln JR, Wisner KL, et al. Omega-3 fatty acids: evidence basis for treatment and future research in psychiatry [American Psychiatric Association subcommittee report]. J Clin Psychiatry 2006;67:1954-67.

27. Otto MW, Church TS, Craft LL, et al. Exercise for mood and anxiety disorders. J Clin Psychiatry 2007;68:669-76.

1. Schmidt PJ, Rubinow DR. Reproductive ageing, sex steroids and depression. J Br Menopause Soc 2006;12(4):178-85.

2. Rasgon N, Shelton S, Halbreich U. Perimenopausal mental disorders: epidemiology and phenomenology. CNS Spectr 2005;10(6):471-8.

3. Greene JG. Constructing a standard climacteric scale. Maturitas 1998;29(1):25-31.

4. Rush AJ, Trivedi MH, Ibrahim HM, et al. The 16-Item Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology (QIDS), clinician rating (QIDS-C), and self-report (QIDS-SR): a psychometric evaluation in patients with chronic major depression. Biol Psychiatry 2003;54(5):573-83.Erratum in: Biol Psychiatry. 2003;54(5):585.

5. Feld J, Halbreich U, Karkun S. The association of perimenopausal mood disorders with other reproductive-related disorders. CNS Spectr 2005;10(6):461-70.

6. Avis NE, Stellato R, Crawford S, et al. Is there a menopausal syndrome? Menopausal status and symptoms across racial/ethnic groups. Soc Sci Med 2001;52:345-56.

7. Campbell S, Whitehead M. Oestrogen therapy and the menopause syndrome. Clin Obstet Gynecol 1977;4:31-47.

8. Schmidt PJ, Rubinow DR. Menopause-related affective disorders: a justification for further study. Am J Psychiatry 1991;48:844-52.

9. Soares CN. Menopausal transition and depression: who is at risk and how to treat it? Expert Rev Neurother 2007;7(10):1285-93.

10. Prior JC. The complex endocrinology of menopausal transition. Endocrinol Rev 1998;19:397-428.

11. Rasgon N, Altshuler LL, Fairbanks LA, et al. Estrogen replacement therapy in the treatment of major depressive disorder in perimenopausal women. J Clin Psychiatry 2002;63(suppl):45-8.

12. Altshuler LL, Cohen LS, Moline ML, et al. The Expert Consensus Guideline Series. Treatment of depression in women. Postgrad Med 2001 Mar;(Spec No):1-107.

13. The Women’s Health Initiative Steering Committee. Effects of conjugated equine estrogen in postmenopausal women with hysterectomy: The Women’s Health Initiative randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2004;291:1701-12.

14. Writing Group for the Women’s Health Initiative Investigators. Risks and benefits of estrogen plus progestin in healthy postmenopausal women: principal results from the Women’s Health Initiative randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2002;288:321-33.

15. Ockene JK, Barad DH, Cochrane BB, et al. Symptom experience after discontinuing use of estrogen plus progestin. JAMA 2005;294:183-93.

16. Shumaker SA, Legault C, Kuller L, et al. Conjugated equine estrogens and incidence of probable dementia and mild cognitive impairment in postmenopausal women: Women’s Health Initiative Memory Study. JAMA 2004;291:2947-58.

17. Shumaker SA, Legault C, Rapp SR. Estrogen plus progestin and the incidence of dementia and mild cognitive impairment in postmenopausal women. The Women’s Health Initiative Memory Study: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2003;289:2651-62.

18. FDA approves new labeling and provides new advice to postmenopausal women who use or who are considering using estrogen and estrogen with progestin [FDA Fact Sheet January 8, 2003]. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/oc/factsheets/WHI.html. Accessed September 11, 2008.

19. Soares CN, Arsenio H, Joffe H, et al. Escitalopram versus ethinyl estradiol and norethindrone acetate for symptomatic peri- and postmenopausal women: impact on depression, vasomotor symptoms, sleep, and quality of life. Menopause 2006;13(5):780-6.

20. Cohen LS, Soares CN, Joffe H. Diagnosis and management of mood disorders during the menopausal transition. Am J Med 2005;118(suppl 12B):93-7.

21. Kahn DA, Moline ML, Ross RW, et al. Depression during the transition to menopause: a guide for patients and families. Postgrad Med 2001 Mar;(Spec No):110-1.

22. Alder J, Besken KE, Armbruster U, et al. Cognitive-behavioural group intervention for climacteric syndrome. Psychother Psychosom 2006;75(5):298-303.

23. Soares CN, Almeida OP, Joffe H, Cohen LS. Efficacy of estradiol for the treatment of depressive disorders in perimenopausal women: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2001;58(6):529-34.

24. Otto MW, Smits JA, Reese HE. Combined psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy for mood and anxiety disorders in adults: review and analysis. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice 2005;12:72-86.

25. Coppen A, Bailey J. Enhancement of the antidepressant action of fluoxetine by folic acid: a randomized, placebo controlled trial. J Affect Disord 2000;60:121-30.

26. Freeman MP, Hibbeln JR, Wisner KL, et al. Omega-3 fatty acids: evidence basis for treatment and future research in psychiatry [American Psychiatric Association subcommittee report]. J Clin Psychiatry 2006;67:1954-67.

27. Otto MW, Church TS, Craft LL, et al. Exercise for mood and anxiety disorders. J Clin Psychiatry 2007;68:669-76.

Bipolar treatment update: Evidence is driving change in mania, depression algorithms

Many well-controlled trials in the past 4 years have evaluated new medications for treating bipolar disorder. It’s time to build a consensus on how this data may apply to clinical practice.

This year, our group will re-examine the Texas Medication Algorithm Project (TMAP) treatment algorithms for bipolar I disorder.

What makes TMAP unique? It is the first project to evaluate treatment algorithm use in community mental health settings for patients with a history of mania (see Box).1-5 Severely, persistently ill outpatients such as these are seldom included in research but are frequently seen in clinical practice.

To preview for psychiatrists the changes expected in 2004, this article describes the goals of TMAP and the controlled study on which the medication algorithms are based. We review the medication algorithms of 2000 as a starting point and present the evidence that is changing clinical practice.

Guiding principles of TMAP

A treatment algorithm is no substitute for clinical judgment; rather, medication guidelines and algorithms are guideposts to help the clinician and patient collaboratively develop the most effective medication strategy with the fewest side effects.

The Texas Medication Algorithm Project (TMAP)1-3 is a public and academic collaboration started in 1996 to develop evidence- and consensus-based medication treatment algorithms for schizophrenia, major depressive disorder, and bipolar disorder.

TMAP’s goal is to establish “best practices” to encourage uniformity of care, achieve the best possible patient outcomes, and use mental health care dollars most efficiently. The project includes four phases, in which the treatment algorithms were developed, compared with treatment-as-usual, put into practice, and will undergo periodic updates.4 The next update begins this year.

The comparison of algorithms for treating bipolar mania/hypomania and depression included 409 patients (mean age 38 to 40) with bipolar I disorder or schizoaffective disorder, bipolar type. These patients were severely and persistently mentally ill, from a diverse ethnic population, and significantly impaired in functioning.

During 12 months of treatment, psychiatric symptoms diminished more rapidly in patients in the algorithm group—as measured by the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS-24)—compared with those receiving usual treatment. After the first 3 months, the usual-treatment patients also showed diminished symptoms. At study’s end, symptom severity between the groups was not significantly different; both groups showed improvement.

Manic and psychotic symptoms—measured by Clinician-Administered Rating Scale subscales (CARS-M)5—improved significantly more in the algorithm group in the first 3 months, and this gap between the two groups was sustained for 12 months. Depressive symptoms declined, but no overall differences were noted between the two groups. Side effect rates and functioning were also similar.

TMAP’s treatment manual (see Related resources) describes clinicians’ preferred tactics and decision points, which we summarize here. The guidelines are an ongoing effort to apply evidence-based medicine to everyday practice and are meant to be adapted to patient needs.

Treatment goals that guided TMAP algorithm development are:

- symptomatic remission

- full return of psychosocial functioning

- prevention of relapse and recurrence.

Suggestions came from controlled clinical trials, open trials, retrospective data analyses, expert clinical consensus, and input from consumers.

Treatment selection. Initial algorithm stages recommend simple treatments (in terms of safety, tolerability, and side effects), whereas later stages recommend more-complicated regimens. A patient’s symptoms, comorbid conditions, and treatment history guide treatment selection. Patients may enter an algorithm at any stage, depending on their clinical presentation and medication history.

The clinician may consider patient preference when deciding among equivalent medications. The algorithm strongly encourages patients and families to participate, such as by keeping daily mood charts and completing symptom and side-effect checklists. When clinicians face a choice among medication brands, generics, or forms (such as immediate- versus slow-release), agents with greater tolerability are preferred.

Patient management. When patients enter the algorithm, clinic visits are frequent (such as every 2 weeks). Follow-up appointments address medication adherence, dosage adjustments, and side effects or adverse reactions.

If a patient’s symptoms show no change after two treatment stages, re-evaluate the diagnosis and consider mitigating factors such as substance abuse. Patients who complete acute treatment should receive continuation treatment.

Documentation. Clinicians are advised to document decision points and the rationale for treatment choices made outside the algorithm package.

Treating mania or hypomania

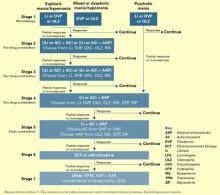

After clinical evaluation confirms the diagnosis of bipolar illness,4 the TMAP mania/hypomania algorithm (Algorithm 1) splits into three treatment pathways:

- euphoric mania/hypomania

- mixed or dysphoric mania/hypomania

- psychotic mania.

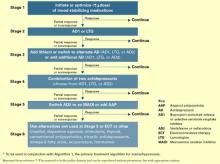

These pathways recognize the need for differing approaches to initial monotherapy and later two-drug combinations. If a patient develops persistent or severe depressive symptoms, the bipolar algorithm for a major depressive episode (Algorithm 2) is used during depressive periods with the primary mania algorithm.

Treatment recommendations. The key to using mood stabilizers is to achieve the optimum response—assuming good tolerability—before switching to another agent. Adjust medication dosages one at a time to allow adequate response and assessment.

When switching medications, use an overlap-and-taper strategy, assuming there is no medical necessity to stop a drug abruptly. Add the new medication, then gradually taper the one that is being discontinued. Monitor serum levels.

Discontinue antidepressants when appropriate in patients with hypomania/mania or rapid cycling, and continually evaluate suicide and homicide potential of patients in mixed or depressive states.

Stage 1: Monotherapy. First medication choices are lithium, divalproex, or olanzapine. For mixed or dysphoric mania, the algorithm recommends divalproex (preferred over valproic acid because of tolerability and side effects) or olanzapine.6 Data suggest dysphoric manic patients are less likely to respond to lithium.7 A Consensus Panel minority expressed concern about using olanzapine as first-line monotherapy for acute mania because of limited data on the drug’s long-term safety. Patients with partial response or residual symptoms may move to stage 2 or switch to other medication options within stage 1.

Patients with psychotic mania move directly to stage 4 for a broader range of combination therapy.

Stage 2: Combination therapy. Combination therapy has become the standard of care in treating most patients with bipolar disorder. The algorithm recommends using two agents:

- lithium or an anticonvulsant plus another anticonvulsant ([Li or AC]+AC)

- or lithium or an anticonvulsant plus an atypical antipsychotic ([Li or AC]+AAP).8

Recommended agents include lithium, divalproex, oxcarbazepine, olanzapine, or risperidone. The experts recommended oxcarbazepine as first choice because it is better tolerated and interacts with fewer drugs than carbamazepine and does not require serum level monitoring.9

A Consensus Panel minority expressed concern that few studies had examined using oxcarbazepine in bipolar disorder. Carbamazepine was also considered an option.

Stages 3 and 4: Other two-drug combinations. Other two-drug combinations are tried at these stages, drawing from the same pool of medication classes described in stage 2.

Stage 4 broadens the choice of atypical antipsychotic by adding quetiapine10 and ziprasidone11 to the recommended stage-2 agents olanzapine and risperidone. When the 2000 algorithm was developed, limited data were available on using some newer atypicals in patients with bipolar mania. Based on recent, high-quality studies of mono- and combination therapy—including quetiapine,10 ziprasidone,11 risperidone,12,13 and aripiprazole14 —the 2004 algorithm update panel will likely recommend using atypicals earlier, including at stage 1.

Algorithm 1 Treating mania/hypomania in patients with bipolar I disorder