User login

Stroke: A road map for subacute management

CASE › A 68-year-old woman with hypertension and hyperlipidemia comes into your office for evaluation of a 30-minute episode of sudden-onset right-hand weakness and difficulty speaking that occurred 4 days earlier. The patient, who is also a smoker, has come in at the insistence of her daughter. On examination, her blood pressure (BP) is 145/88 mm Hg and her heart rate is 76 beats/minute and regular. She appears well and her language function is normal. The rest of her examination is normal. How would you proceed?

Stroke—the death of nerve cells due to a lack of blood supply from either infarction or hemorrhage—strikes nearly 800,000 people in the United States every year.1,2 Of these events, 130,000 are fatal, making stroke the fifth leading cause of death.3 Effective, early evaluation and cause-specific treatment are crucial parts of stroke care.

Research has helped to clarify the critical role primary care physicians play in recognizing, triaging, and managing stroke and transient ischemic attacks (TIA). This article reviews what we know about the different ways that a stroke and a TIA can present, the appropriate diagnostic work-up for patients presenting with symptoms of either event, and management strategies for subacute care (24 hours to up to 14 days after a stroke has occurred).4,5 Unless otherwise specified, this review will focus on ischemic stroke because 87% of strokes are attributable to ischemia.1

A follow-up to this article on secondary stroke prevention will appear in the journal next month.

Look to onset more than type of symptoms for clues

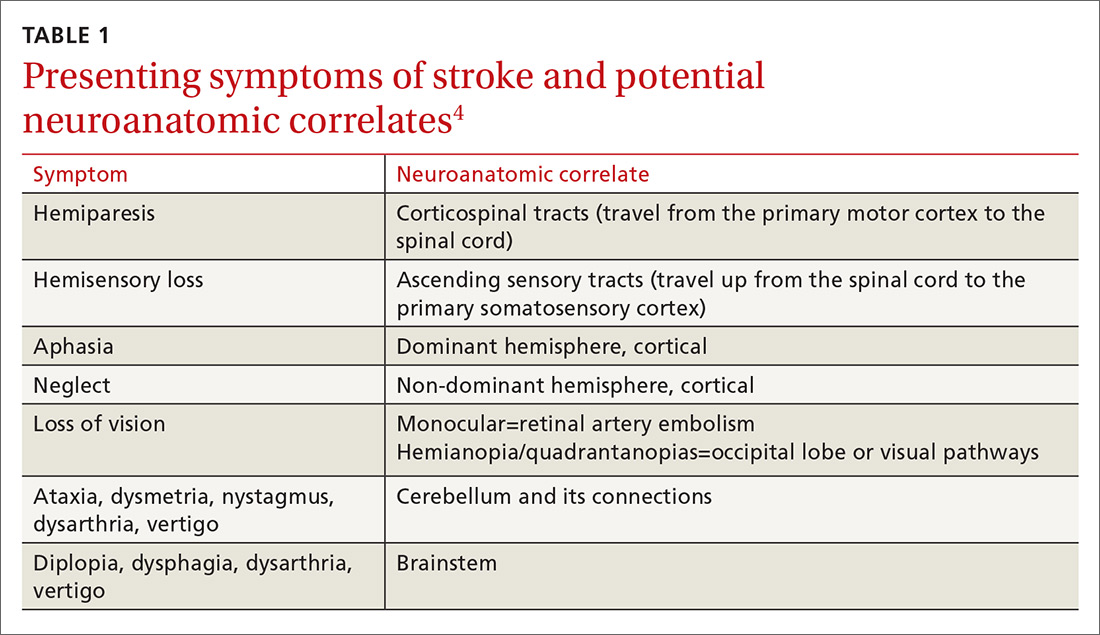

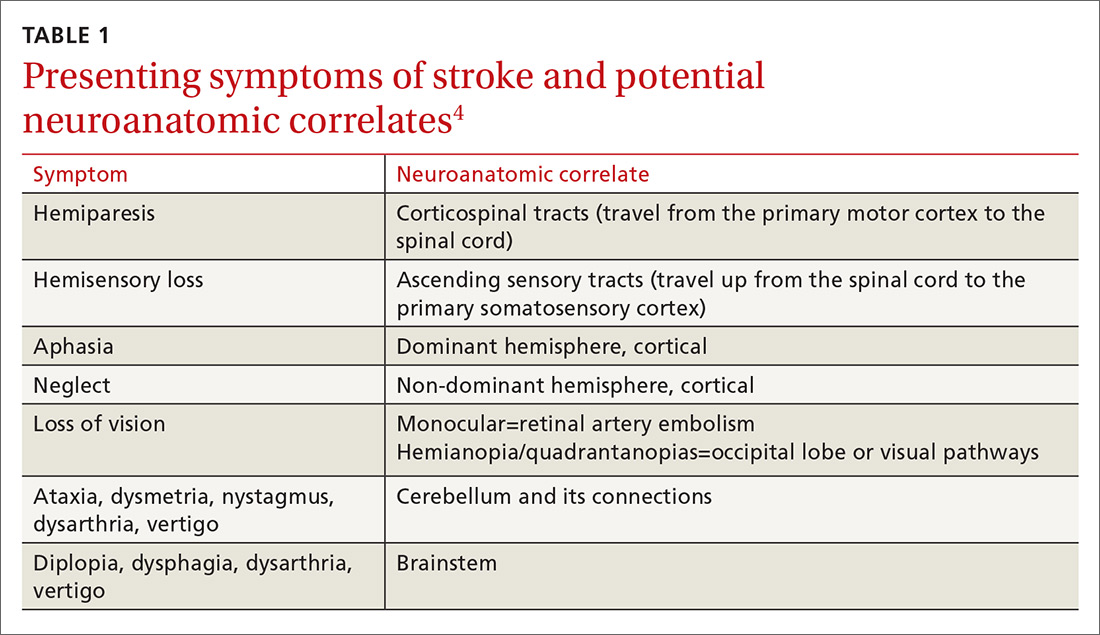

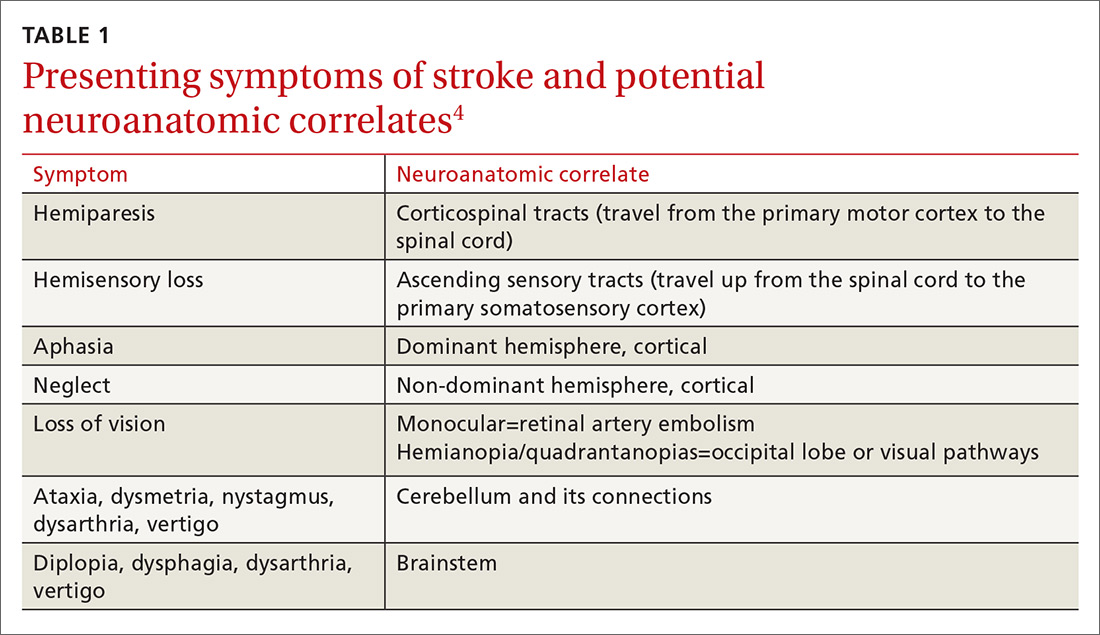

Stroke presents as a sudden onset of neurologic deficits (language, motor, sensory, cerebellar, or brainstem functions) (TABLE 14). Because presenting symptoms can vary widely, sudden onset, rather than particular symptoms, should raise a red flag for potential stroke.

The differential diagnosis includes: seizure, complex migraine, medication effect (eg, slurred speech or confusion after taking a central nervous system [CNS] depressant), toxin exposure, electrolyte abnormalities (especially hypoglycemia), concussion/trauma, infection of the CNS, peripheral vertigo, demyelination, intracranial mass, Bell’s palsy, and psychogenic disorders. The history and physical, along with laboratory findings and brain imaging (detailed later in this article), will guide the FP toward (or away from) these various etiologies.

Optimal triage is a subject of ongoing interest and research

If stroke or TIA remains a possibility after an initial assessment, it’s time to stratify patients by risk.

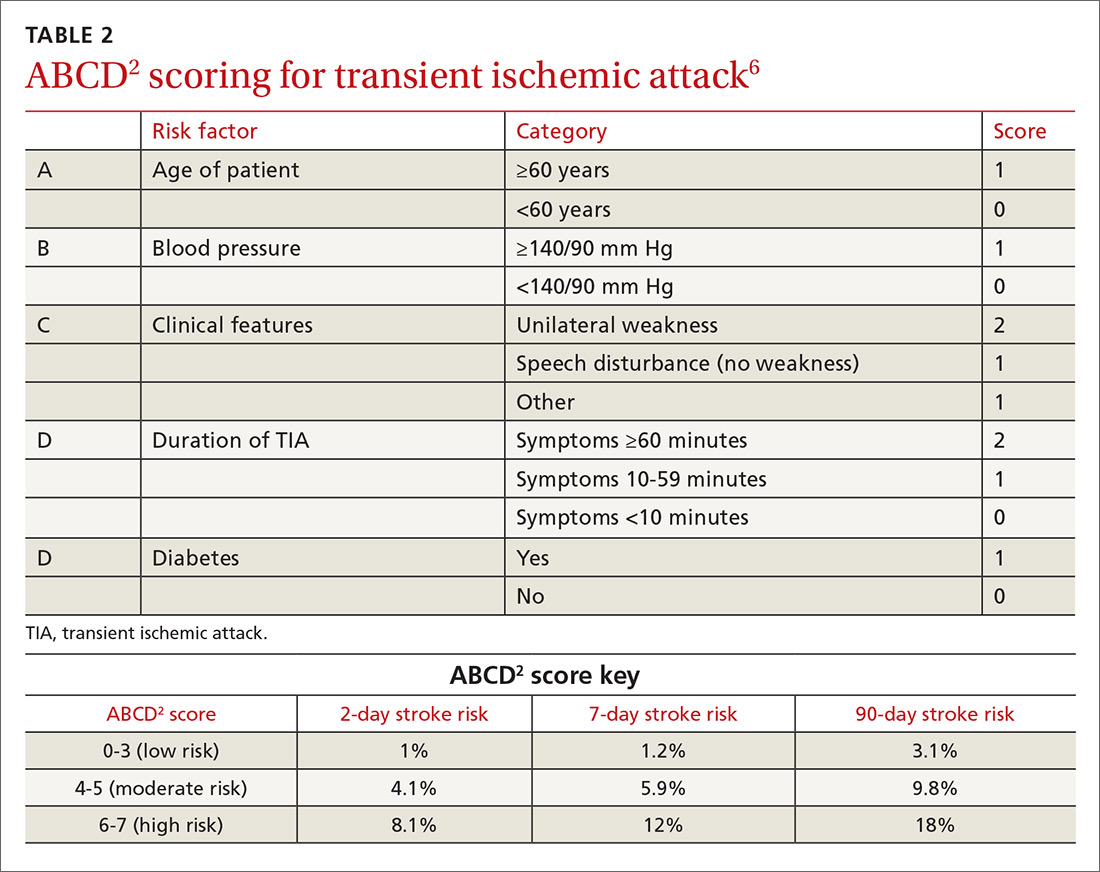

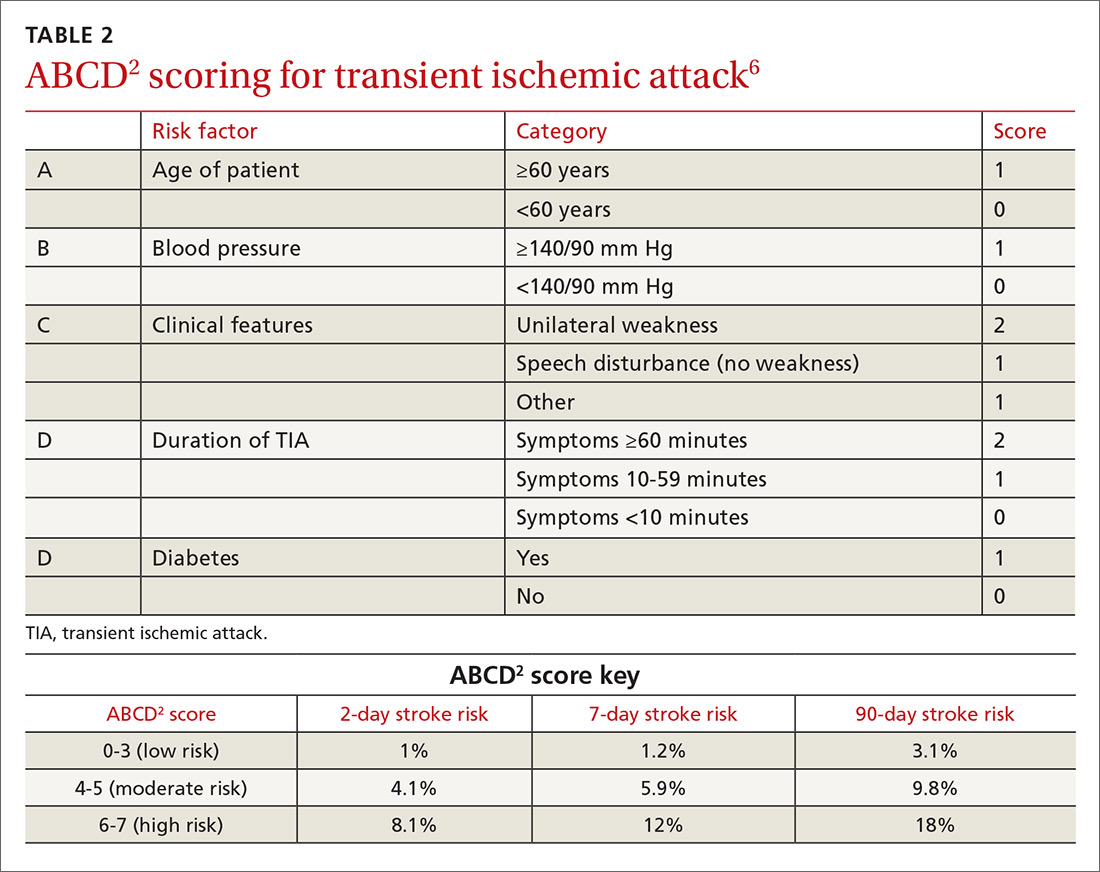

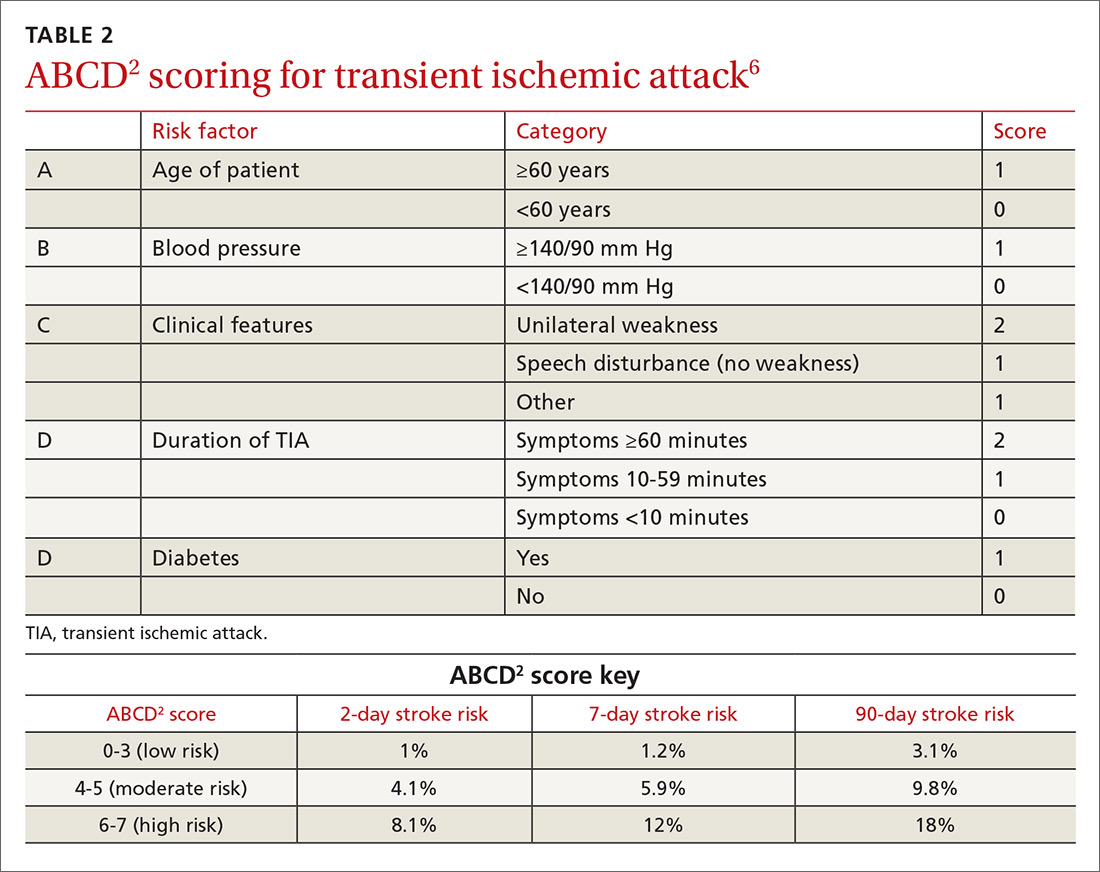

One of the most widely accepted tools is the ABCD2 score (see TABLE 26). Clinicians can employ the ABCD2 risk stratification tool when trying to determine whether it is reasonable to pursue an expedited work-up (ie, <1 day) in the outpatient setting or recommend that the patient be evaluated in an emergency department (ED). The 90-day stroke rate following a TIA ranges from 3% with an ABCD2 score of 0 to 3 to 18% with a score of 6 or 7. A score of 0 to 3 is considered relatively low risk; in the absence of other compelling factors, rapid outpatient evaluation is appropriate. For patients with an ABCD2 score ≥4, referral to the ED or direct admission to the hospital is advised.

The validity of the ABCD2 score for risk stratification has been studied extensively with conflicting results.7-10 As with any assessment tool, it should be used as a guide, and should not supplant a full assessment of the patient or the judgment of the examining physician. In making the decision regarding inpatient or outpatient evaluation, it’s also important to consider available resources, access to specialists, and patient preference.

In a 2016 population-based study, the 30-day recurrent stroke/TIA rate for patients hospitalized for TIA was 3% compared with 10.7% for those discharged from the ED with referral to a stroke clinic and 10.6% for those discharged from the ED without a referral to a stroke clinic.11 These data suggest that only patients for whom you have a low clinical suspicion of stroke/TIA should be worked up as outpatients, and that hospital admission is advised in moderate- and high-risk cases. The findings also highlight the critical role that primary care physicians can play in triaging and managing these patients for secondary prevention.

CASE › This patient’s recent history of sudden-onset right-sided weakness and expressive language dysfunction is suspicious for left hemispheric ischemia. She has several risk factors for stroke, and her ABCD2 score is 5 (hypertension, age ≥60 years, unilateral weakness, and duration 10-59 min), which places her at moderate risk. Thus, the recommendation would be to have her go directly to an ED for rapid evaluation.

The diagnostic work-up

Even when a patient is sent to the ED, the FP plays a critical role in his or her continuing care. FPs will often coordinate with inpatient care and manage transition of care to the outpatient setting. (And in many communities, the ED or hospital physicians may themselves be family practitioners.)

In terms of care, not even an aspirin should be administered in a case like this because the patient has not yet had any neuroimaging, and differentiation of ischemic from hemorrhagic stroke cannot be made on clinical grounds alone. Once an ischemic stroke is confirmed, determining the etiology is critical given the significant management differences between the different types of stroke (atherosclerotic, cardioembolic, lacunar, or other).

Which imaging method, and when?

While a computerized tomography (CT) scan is the preferred initial imaging strategy for acute stroke to discern the ischemic type from the hemorrhagic, MRI is preferred for the evaluation of acute ischemic stroke because the method has a higher sensitivity for infarction and a greater ability to identify findings (such as demyelination) that would suggest an alternative diagnosis.

In addition to evaluating the brain parenchyma, physicians must also assess the cerebral vasculature. CT angiography (CTA) or MR angiography (MRA) of the head and neck are preferred over carotid ultrasound because they are capable of evaluating the entire cerebrovascular system12,13 and can be instrumental in identifying potential causes of stroke, as well as guiding therapeutic decisions. Carotid ultrasound is a reasonable alternative for patients presenting with symptoms indicative of anterior circulation involvement when CTA and MRA are unavailable or contraindicated, but it will not identify intracranial vascular disease, proximal common carotid disease, or vertebrobasilar disease.

Getting to the cause of suspected stroke: Labs and other diagnostic tests

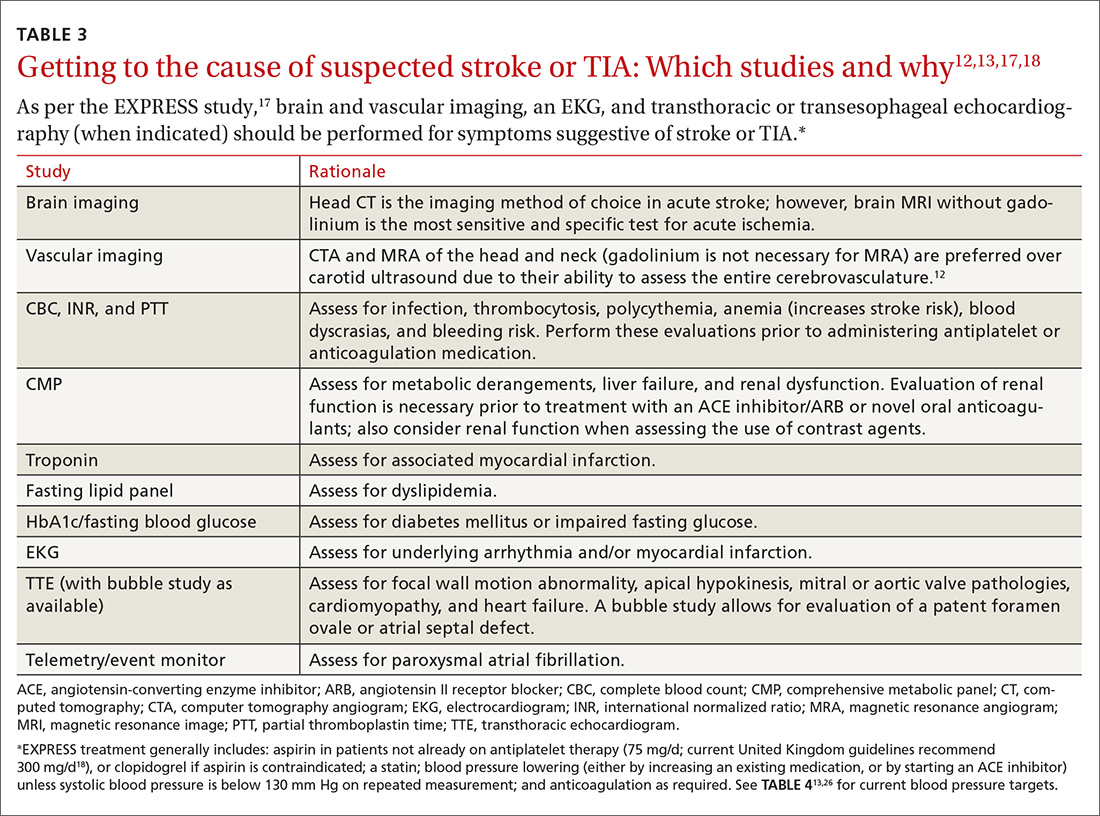

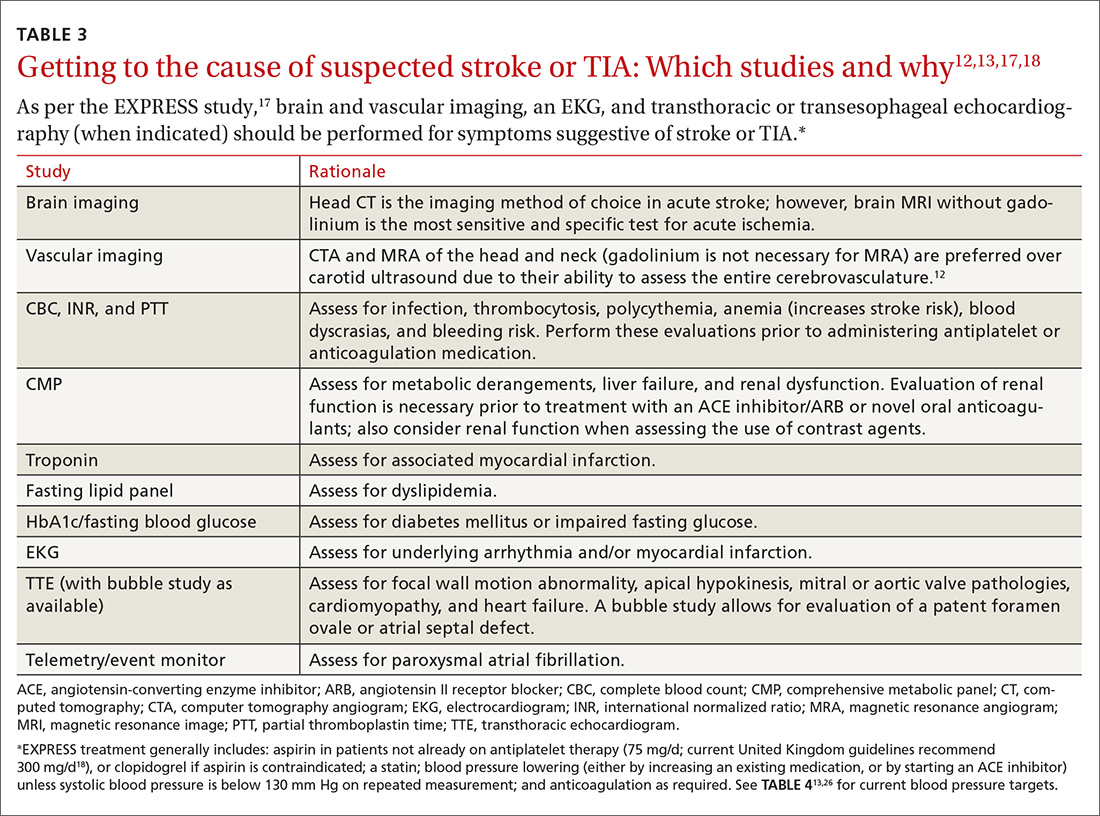

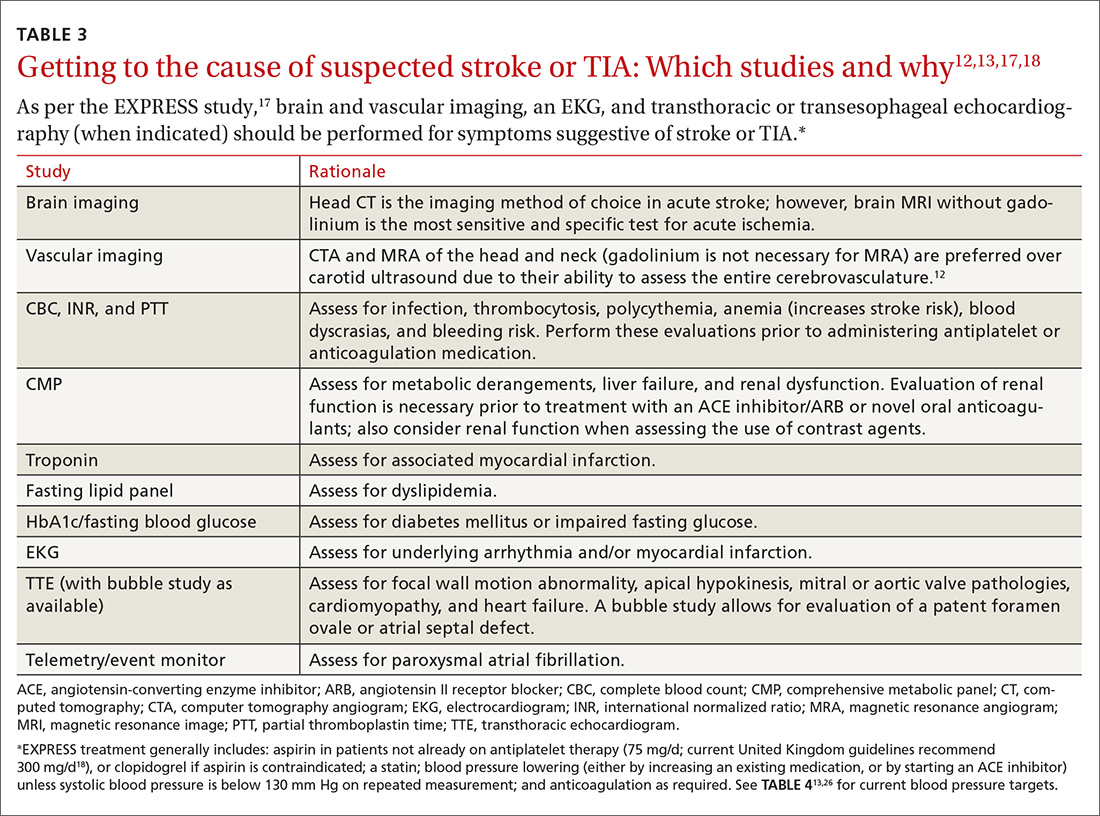

A routine work-up includes BP checks, routine labs (complete blood count, complete metabolic panel, coagulation profile, and troponin), an electrocardiogram (EKG), a transthoracic echocardiogram (TTE) with bubble study if possible, and a minimum of 24 to 48 hours of cardiac rhythm monitoring. Cardiac rhythm monitoring should be extended in the setting of clinical concern for unidentified paroxysmal atrial fibrillation, such as an embolism without a proximal vascular source, multiple embolic infarcts in different vascular territories, a dilated left atrium, or other risk factors for atrial fibrillation that include smoking, systolic hypertension, diabetes, and heart failure (see TABLE 312,13,17,18).14-16 This standard diagnostic work-up will identify the cause of stroke in 70% to 80% of patients.19

Additional investigations to consider if the etiology is not yet elucidated include a transesophageal echocardiogram (TEE), cerebral angiography, a coagulopathy evaluation, a lumbar puncture, and a vasculitis work-up. If available, consultation with a neurologist is appropriate for any patient who has had a stroke or TIA. Patients with unclear etiologies or for whom there are questions concerning strategies for preventing secondary stroke should be referred to Neurology and preferably a stroke specialist.

Timing matters, even when symptoms have resolved (ie, TIA).11,20 The EXPRESS trial17 (the Early use of eXisting PREventive Strategies for Stroke) looked at the effect of urgent assessment and treatment (≤1 day) of patients presenting with a TIA or minor stroke on the risk of recurrent stroke within 90 days. The diagnostic work-up included brain and vascular imaging together with an EKG. This intensive approach led to an absolute risk reduction of 8.2% (from 10.3% to 2.1%) in the risk of recurrent stroke at 90 days (number needed to treat [NNT]=12).17

Expedited work-up and treatment was also recently evaluated in a non-trial, real-world setting and was associated with reducing recurrent stroke by more than half the rate reported in older studies.20 Overall, the data suggest that evaluation within 24 hours confers substantial benefit, and that this evaluation can happen in an outpatient setting.21-23

Acute management: Use of tPA

Once imaging rules out intracranial hemorrhage, patients should be treated with tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) or an endovascular intervention as per guidelines.24 For patients with ischemic stroke ineligible for tPA or endovascular treatments, the initial focus is to determine the etiology of the symptoms so that the best strategies for prevention of secondary stroke may be employed.

Aspirin should be provided within 24 to 48 hours to all patients after intracranial hemorrhage is ruled out. Aspirin should be delayed for 24 hours in those given thrombolytics. The initial recommended dose of aspirin is 325 mg with continued low-dose (81 mg) aspirin daily.13 The addition of clopidogrel to aspirin within 24 hours of an event and continued for 21 days, followed by aspirin alone, was shown to be beneficial in a Chinese population with high-risk TIA (ABCD2 score ≥4) or minor stroke (National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale [NIHSS] ≤3).25 Anticoagulation with heparin, warfarin, or a novel oral anticoagulant is generally not indicated in the acute setting due to the risk of hemorrhagic transformation.

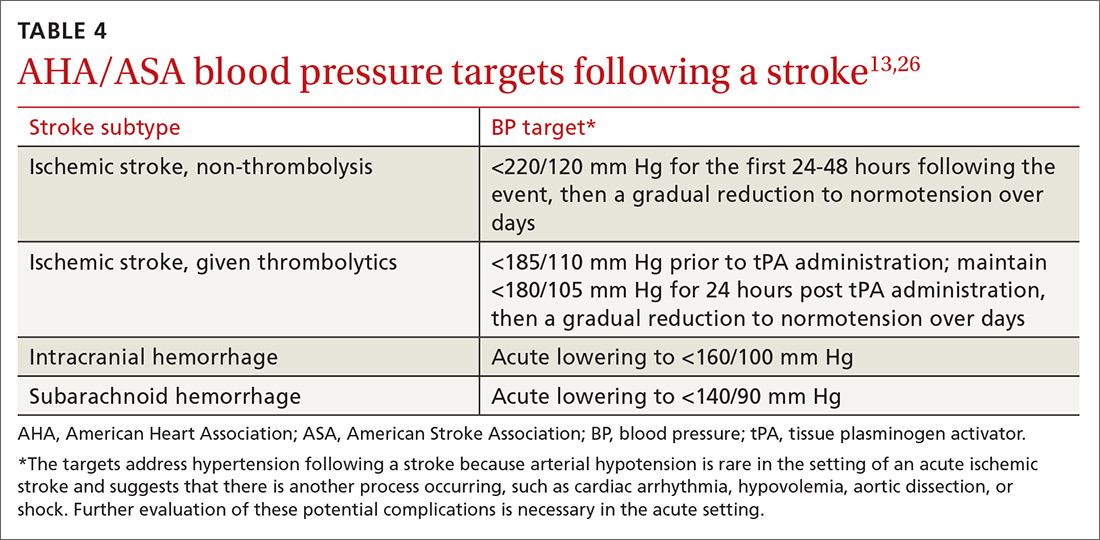

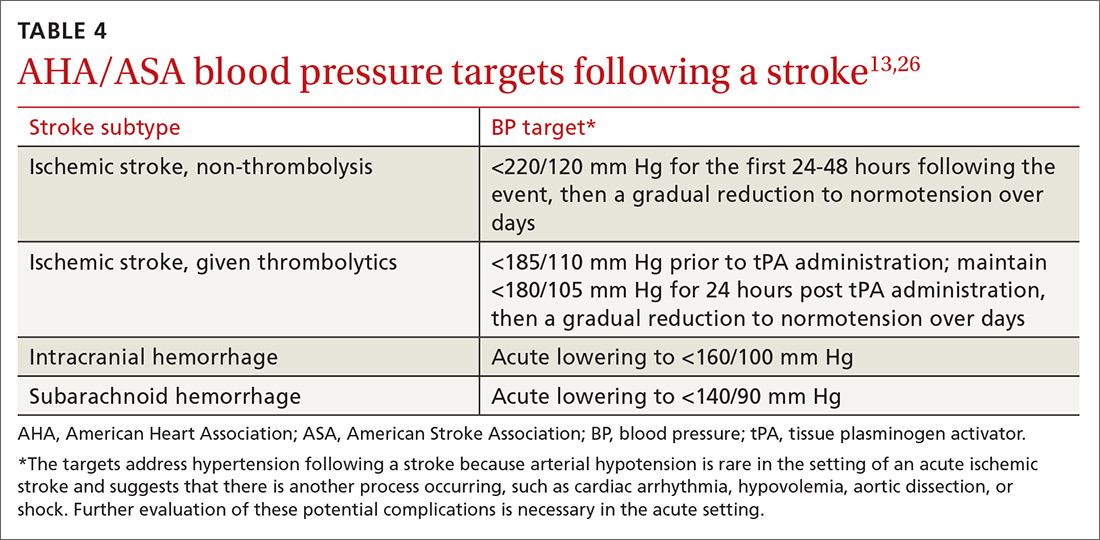

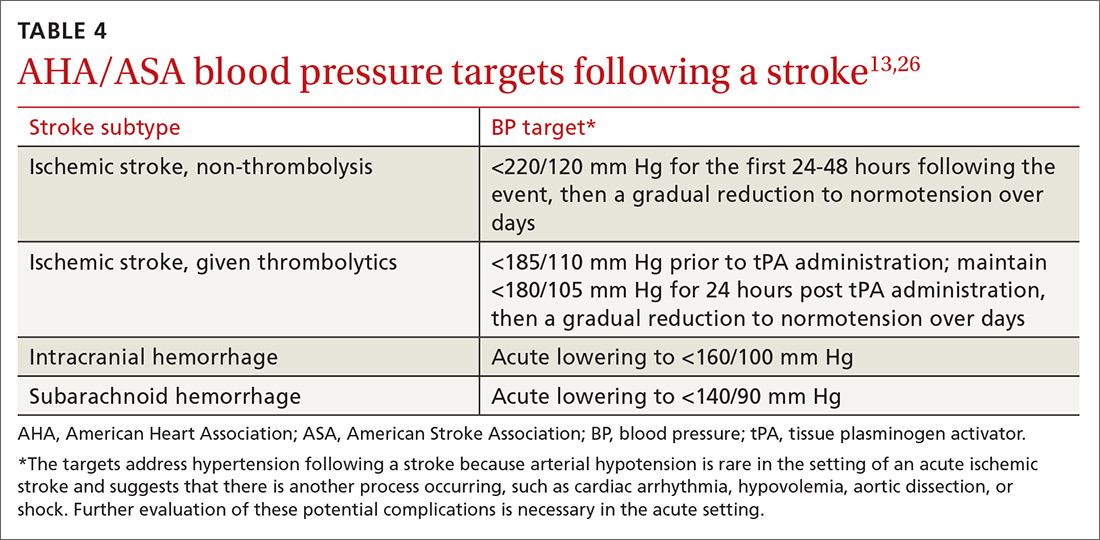

Acute BP management depends upon the type of stroke (ischemic or hemorrhagic), eligibility for thrombolytics, timing of presentation, and possible comorbidities such as myocardial infarction or aortic dissection (see TABLE 413,26). In the absence of contraindications, high-intensity statins should be initiated in all patients able to take oral medications.

CASE › You appropriately referred your patient to the local ED. A head CT with head and neck CTA was performed. While the head CT did not show any abnormalities, the CTA demonstrated high-grade left internal carotid artery stenosis. The patient was given an initial dose of aspirin 325 mg and a high-intensity statin and admitted for further management. An MRI revealed a small shower of emboli in the left hemisphere, confirming the diagnosis of stroke over TIA. Labs were marginally remarkable with a low-density lipoprotein level of 115 mg/dL and an HbA1c of 6.2. Telemetry monitoring did not reveal any arrhythmias, and TTE was normal. BP remained in the high-normal to low-hypertensive range.

A Vascular Surgery consultation was obtained and the patient underwent a left carotid endarterectomy the following day. She did well without surgical complications. Her BP medications were adjusted; a combination of an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor and a thiazide diuretic achieved a goal BP <140/90 mm Hg.

Permissive hypertension was not indicated due to her presentation >48 hours beyond the acute event. Low-dose aspirin and a high-intensity statin were continued, for secondary stroke prevention in the setting of atherosclerotic disease. She received smoking cessation counseling, which will continue.

CORRESPONDENCE

Stephen A. Martin, MD, EdM, Barre Family Health Center, 151 Worcester Road, Barre, MA 01005; stmartin@gmail.com.

1. Benjamin EJ, Blaha MJ, Chiuve SE, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics-2017 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2017;135:e146-e603.

2. Sacco RL, Kasner SE, Broderick JP, et al. An updated definition of stroke for the 21st century: a statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2013;44:2064-2089.

3. Kochanek KD, Murphy SL, Xu J, et al. Mortality in the United States, 2013. NCHS Data Brief. 2014:1-8. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db178.pdf. Accessed June 5, 2016.

4. Flossmann E, Redgrave JN, Briley D, et al. Reliability of clinical diagnosis of the symptomatic vascular territory in patients with recent transient ischemic attack or minor stroke. Stroke. 2008;39:2457-2460.

5. Josephson SA, Sidney S, Pham TN, et al. Higher ABCD2 score predicts patients most likely to have true transient ischemic attack. Stroke. 2008;39:3096-3098. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18688003. Accessed June 5, 2016.

6. Hankey GJ. The ABCD, California, and unified ABCD2 risk scores predicted stroke within 2, 7, and 90 days after TIA. Evid Based Med. 2007;12:88.

7. Sheehan OC, Kyne L, Kelly LA, et al. Population-based study of ABCD2 score, carotid stenosis, and atrial fibrillation for early stroke prediction after transient ischemic attack: the North Dublin TIA study. Stroke. 2010;41:844-850.

8. Rothwell PM, Giles MF, Flossmann E, et al. A simple score (ABCD) to identify individuals at high early risk of stroke after transient ischaemic attack. Lancet. 2005; 366:29-36.

9. Tsivgoulis G, Spengos K, Manta P, et al. Validation of the ABCD score in identifying individuals at high early risk of stroke after a transient ischemic attack: a hospital-based case series study. Stroke. 2006;37:2892-2897.

10. Kiyohara T, Kamouchi M, Kumai Y, et al. ABCD3 and ABCD3-I scores are superior to ABCD2 score in the prediction of short- and long-term risks of stroke after transient ischemic attack. Stroke. 2014;45:418-425.

11. Sacco RL, Rundek T. The value of urgent specialized care for TIA and minor stroke. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:1577-1579.

12. Demchuk AM, Menon BK, Goyal M. Comparing vessel imaging: noncontrast computed tomography/computed tomographic angiography should be the new minimum standard in acute disabling stroke. Stroke. 2016;47:273-281.

13. Jauch EC, Saver JL, Adams HP, et al. Guidelines for the early management of patients with acute ischemic stroke: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2013;44:870-947.

14. Gladstone DJ, Spring M, Dorian P, et al. Atrial fibrillation in patients with cryptogenic stroke. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:2467-2477.

15. Sanna T, Diener HC, Passman RS, et al. Cryptogenic stroke and underlying atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:2478-2486.

16. Christophersen IE, Yin X, Larson MG, et al. A comparison of the CHARGE-AF and the CHA2DS2-VASc risk scores for prediction of atrial fibrillation ni the Framingham Heart Study. Am Heart J. 2016;178:45-54.

17. Rothwell PM, Giles MF, Chandratheva A, et al. Effect of urgent treatment of transient ischaemic attack and minor stroke on early recurrent stroke (EXPRESS study): a prospective population-based sequential comparison. Lancet. 2007;370:1432-1442.

18. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Stroke and transient ischaemic attack in over 16s: diagnosis and initial management. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg68. Published 2008. Accessed February 5, 2017.

19. Hart RG, Diener HC, Coutts SB, et al. Embolic strokes of undetermined source: the case for a new clinical construct. Lancet Neurol. 2014;13:429-438.

20. Amarenco P, Lavallée PC, Labreuche J, et al. One-year risk of stroke after transient ischemic attack or minor stroke. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:1533-1542.

21. Joshi JK, Ouyang B, Prabhakaran S. Should TIA patients be hospitalized or referred to a same-day clinic? A decision analysis. Neurology. 2011;77:2082-2088.

22. Mijalski C, Silver B. TIA management: should TIA patients be admitted? should TIA patients get combination antiplatelet therapy? The Neurohospitalist. 2015;5:151-160.

23. Silver B, Adeoye O. Management of patients with transient ischemic attack in the emergency department. Neurology. 2016;86:1568-1569.

24. Demaerschalk BM, Kleindorfer DO, Adeoye OM, et al. Scientific rationale for the inclusion and exclusion criteria for intravenous alteplase in acute ischemic stroke: a statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2016;47:581-641.

25. Wang Y, Wang Y, Zhao X, et al. Clopidogrel with aspirin in acute minor stroke or transient ischemic attack. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:11-19.

26. Hemphill JC, Greenberg SM, Anderson CS, et al. Guidelines for the management of spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke. 2015;46:2032-2060.

CASE › A 68-year-old woman with hypertension and hyperlipidemia comes into your office for evaluation of a 30-minute episode of sudden-onset right-hand weakness and difficulty speaking that occurred 4 days earlier. The patient, who is also a smoker, has come in at the insistence of her daughter. On examination, her blood pressure (BP) is 145/88 mm Hg and her heart rate is 76 beats/minute and regular. She appears well and her language function is normal. The rest of her examination is normal. How would you proceed?

Stroke—the death of nerve cells due to a lack of blood supply from either infarction or hemorrhage—strikes nearly 800,000 people in the United States every year.1,2 Of these events, 130,000 are fatal, making stroke the fifth leading cause of death.3 Effective, early evaluation and cause-specific treatment are crucial parts of stroke care.

Research has helped to clarify the critical role primary care physicians play in recognizing, triaging, and managing stroke and transient ischemic attacks (TIA). This article reviews what we know about the different ways that a stroke and a TIA can present, the appropriate diagnostic work-up for patients presenting with symptoms of either event, and management strategies for subacute care (24 hours to up to 14 days after a stroke has occurred).4,5 Unless otherwise specified, this review will focus on ischemic stroke because 87% of strokes are attributable to ischemia.1

A follow-up to this article on secondary stroke prevention will appear in the journal next month.

Look to onset more than type of symptoms for clues

Stroke presents as a sudden onset of neurologic deficits (language, motor, sensory, cerebellar, or brainstem functions) (TABLE 14). Because presenting symptoms can vary widely, sudden onset, rather than particular symptoms, should raise a red flag for potential stroke.

The differential diagnosis includes: seizure, complex migraine, medication effect (eg, slurred speech or confusion after taking a central nervous system [CNS] depressant), toxin exposure, electrolyte abnormalities (especially hypoglycemia), concussion/trauma, infection of the CNS, peripheral vertigo, demyelination, intracranial mass, Bell’s palsy, and psychogenic disorders. The history and physical, along with laboratory findings and brain imaging (detailed later in this article), will guide the FP toward (or away from) these various etiologies.

Optimal triage is a subject of ongoing interest and research

If stroke or TIA remains a possibility after an initial assessment, it’s time to stratify patients by risk.

One of the most widely accepted tools is the ABCD2 score (see TABLE 26). Clinicians can employ the ABCD2 risk stratification tool when trying to determine whether it is reasonable to pursue an expedited work-up (ie, <1 day) in the outpatient setting or recommend that the patient be evaluated in an emergency department (ED). The 90-day stroke rate following a TIA ranges from 3% with an ABCD2 score of 0 to 3 to 18% with a score of 6 or 7. A score of 0 to 3 is considered relatively low risk; in the absence of other compelling factors, rapid outpatient evaluation is appropriate. For patients with an ABCD2 score ≥4, referral to the ED or direct admission to the hospital is advised.

The validity of the ABCD2 score for risk stratification has been studied extensively with conflicting results.7-10 As with any assessment tool, it should be used as a guide, and should not supplant a full assessment of the patient or the judgment of the examining physician. In making the decision regarding inpatient or outpatient evaluation, it’s also important to consider available resources, access to specialists, and patient preference.

In a 2016 population-based study, the 30-day recurrent stroke/TIA rate for patients hospitalized for TIA was 3% compared with 10.7% for those discharged from the ED with referral to a stroke clinic and 10.6% for those discharged from the ED without a referral to a stroke clinic.11 These data suggest that only patients for whom you have a low clinical suspicion of stroke/TIA should be worked up as outpatients, and that hospital admission is advised in moderate- and high-risk cases. The findings also highlight the critical role that primary care physicians can play in triaging and managing these patients for secondary prevention.

CASE › This patient’s recent history of sudden-onset right-sided weakness and expressive language dysfunction is suspicious for left hemispheric ischemia. She has several risk factors for stroke, and her ABCD2 score is 5 (hypertension, age ≥60 years, unilateral weakness, and duration 10-59 min), which places her at moderate risk. Thus, the recommendation would be to have her go directly to an ED for rapid evaluation.

The diagnostic work-up

Even when a patient is sent to the ED, the FP plays a critical role in his or her continuing care. FPs will often coordinate with inpatient care and manage transition of care to the outpatient setting. (And in many communities, the ED or hospital physicians may themselves be family practitioners.)

In terms of care, not even an aspirin should be administered in a case like this because the patient has not yet had any neuroimaging, and differentiation of ischemic from hemorrhagic stroke cannot be made on clinical grounds alone. Once an ischemic stroke is confirmed, determining the etiology is critical given the significant management differences between the different types of stroke (atherosclerotic, cardioembolic, lacunar, or other).

Which imaging method, and when?

While a computerized tomography (CT) scan is the preferred initial imaging strategy for acute stroke to discern the ischemic type from the hemorrhagic, MRI is preferred for the evaluation of acute ischemic stroke because the method has a higher sensitivity for infarction and a greater ability to identify findings (such as demyelination) that would suggest an alternative diagnosis.

In addition to evaluating the brain parenchyma, physicians must also assess the cerebral vasculature. CT angiography (CTA) or MR angiography (MRA) of the head and neck are preferred over carotid ultrasound because they are capable of evaluating the entire cerebrovascular system12,13 and can be instrumental in identifying potential causes of stroke, as well as guiding therapeutic decisions. Carotid ultrasound is a reasonable alternative for patients presenting with symptoms indicative of anterior circulation involvement when CTA and MRA are unavailable or contraindicated, but it will not identify intracranial vascular disease, proximal common carotid disease, or vertebrobasilar disease.

Getting to the cause of suspected stroke: Labs and other diagnostic tests

A routine work-up includes BP checks, routine labs (complete blood count, complete metabolic panel, coagulation profile, and troponin), an electrocardiogram (EKG), a transthoracic echocardiogram (TTE) with bubble study if possible, and a minimum of 24 to 48 hours of cardiac rhythm monitoring. Cardiac rhythm monitoring should be extended in the setting of clinical concern for unidentified paroxysmal atrial fibrillation, such as an embolism without a proximal vascular source, multiple embolic infarcts in different vascular territories, a dilated left atrium, or other risk factors for atrial fibrillation that include smoking, systolic hypertension, diabetes, and heart failure (see TABLE 312,13,17,18).14-16 This standard diagnostic work-up will identify the cause of stroke in 70% to 80% of patients.19

Additional investigations to consider if the etiology is not yet elucidated include a transesophageal echocardiogram (TEE), cerebral angiography, a coagulopathy evaluation, a lumbar puncture, and a vasculitis work-up. If available, consultation with a neurologist is appropriate for any patient who has had a stroke or TIA. Patients with unclear etiologies or for whom there are questions concerning strategies for preventing secondary stroke should be referred to Neurology and preferably a stroke specialist.

Timing matters, even when symptoms have resolved (ie, TIA).11,20 The EXPRESS trial17 (the Early use of eXisting PREventive Strategies for Stroke) looked at the effect of urgent assessment and treatment (≤1 day) of patients presenting with a TIA or minor stroke on the risk of recurrent stroke within 90 days. The diagnostic work-up included brain and vascular imaging together with an EKG. This intensive approach led to an absolute risk reduction of 8.2% (from 10.3% to 2.1%) in the risk of recurrent stroke at 90 days (number needed to treat [NNT]=12).17

Expedited work-up and treatment was also recently evaluated in a non-trial, real-world setting and was associated with reducing recurrent stroke by more than half the rate reported in older studies.20 Overall, the data suggest that evaluation within 24 hours confers substantial benefit, and that this evaluation can happen in an outpatient setting.21-23

Acute management: Use of tPA

Once imaging rules out intracranial hemorrhage, patients should be treated with tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) or an endovascular intervention as per guidelines.24 For patients with ischemic stroke ineligible for tPA or endovascular treatments, the initial focus is to determine the etiology of the symptoms so that the best strategies for prevention of secondary stroke may be employed.

Aspirin should be provided within 24 to 48 hours to all patients after intracranial hemorrhage is ruled out. Aspirin should be delayed for 24 hours in those given thrombolytics. The initial recommended dose of aspirin is 325 mg with continued low-dose (81 mg) aspirin daily.13 The addition of clopidogrel to aspirin within 24 hours of an event and continued for 21 days, followed by aspirin alone, was shown to be beneficial in a Chinese population with high-risk TIA (ABCD2 score ≥4) or minor stroke (National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale [NIHSS] ≤3).25 Anticoagulation with heparin, warfarin, or a novel oral anticoagulant is generally not indicated in the acute setting due to the risk of hemorrhagic transformation.

Acute BP management depends upon the type of stroke (ischemic or hemorrhagic), eligibility for thrombolytics, timing of presentation, and possible comorbidities such as myocardial infarction or aortic dissection (see TABLE 413,26). In the absence of contraindications, high-intensity statins should be initiated in all patients able to take oral medications.

CASE › You appropriately referred your patient to the local ED. A head CT with head and neck CTA was performed. While the head CT did not show any abnormalities, the CTA demonstrated high-grade left internal carotid artery stenosis. The patient was given an initial dose of aspirin 325 mg and a high-intensity statin and admitted for further management. An MRI revealed a small shower of emboli in the left hemisphere, confirming the diagnosis of stroke over TIA. Labs were marginally remarkable with a low-density lipoprotein level of 115 mg/dL and an HbA1c of 6.2. Telemetry monitoring did not reveal any arrhythmias, and TTE was normal. BP remained in the high-normal to low-hypertensive range.

A Vascular Surgery consultation was obtained and the patient underwent a left carotid endarterectomy the following day. She did well without surgical complications. Her BP medications were adjusted; a combination of an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor and a thiazide diuretic achieved a goal BP <140/90 mm Hg.

Permissive hypertension was not indicated due to her presentation >48 hours beyond the acute event. Low-dose aspirin and a high-intensity statin were continued, for secondary stroke prevention in the setting of atherosclerotic disease. She received smoking cessation counseling, which will continue.

CORRESPONDENCE

Stephen A. Martin, MD, EdM, Barre Family Health Center, 151 Worcester Road, Barre, MA 01005; stmartin@gmail.com.

CASE › A 68-year-old woman with hypertension and hyperlipidemia comes into your office for evaluation of a 30-minute episode of sudden-onset right-hand weakness and difficulty speaking that occurred 4 days earlier. The patient, who is also a smoker, has come in at the insistence of her daughter. On examination, her blood pressure (BP) is 145/88 mm Hg and her heart rate is 76 beats/minute and regular. She appears well and her language function is normal. The rest of her examination is normal. How would you proceed?

Stroke—the death of nerve cells due to a lack of blood supply from either infarction or hemorrhage—strikes nearly 800,000 people in the United States every year.1,2 Of these events, 130,000 are fatal, making stroke the fifth leading cause of death.3 Effective, early evaluation and cause-specific treatment are crucial parts of stroke care.

Research has helped to clarify the critical role primary care physicians play in recognizing, triaging, and managing stroke and transient ischemic attacks (TIA). This article reviews what we know about the different ways that a stroke and a TIA can present, the appropriate diagnostic work-up for patients presenting with symptoms of either event, and management strategies for subacute care (24 hours to up to 14 days after a stroke has occurred).4,5 Unless otherwise specified, this review will focus on ischemic stroke because 87% of strokes are attributable to ischemia.1

A follow-up to this article on secondary stroke prevention will appear in the journal next month.

Look to onset more than type of symptoms for clues

Stroke presents as a sudden onset of neurologic deficits (language, motor, sensory, cerebellar, or brainstem functions) (TABLE 14). Because presenting symptoms can vary widely, sudden onset, rather than particular symptoms, should raise a red flag for potential stroke.

The differential diagnosis includes: seizure, complex migraine, medication effect (eg, slurred speech or confusion after taking a central nervous system [CNS] depressant), toxin exposure, electrolyte abnormalities (especially hypoglycemia), concussion/trauma, infection of the CNS, peripheral vertigo, demyelination, intracranial mass, Bell’s palsy, and psychogenic disorders. The history and physical, along with laboratory findings and brain imaging (detailed later in this article), will guide the FP toward (or away from) these various etiologies.

Optimal triage is a subject of ongoing interest and research

If stroke or TIA remains a possibility after an initial assessment, it’s time to stratify patients by risk.

One of the most widely accepted tools is the ABCD2 score (see TABLE 26). Clinicians can employ the ABCD2 risk stratification tool when trying to determine whether it is reasonable to pursue an expedited work-up (ie, <1 day) in the outpatient setting or recommend that the patient be evaluated in an emergency department (ED). The 90-day stroke rate following a TIA ranges from 3% with an ABCD2 score of 0 to 3 to 18% with a score of 6 or 7. A score of 0 to 3 is considered relatively low risk; in the absence of other compelling factors, rapid outpatient evaluation is appropriate. For patients with an ABCD2 score ≥4, referral to the ED or direct admission to the hospital is advised.

The validity of the ABCD2 score for risk stratification has been studied extensively with conflicting results.7-10 As with any assessment tool, it should be used as a guide, and should not supplant a full assessment of the patient or the judgment of the examining physician. In making the decision regarding inpatient or outpatient evaluation, it’s also important to consider available resources, access to specialists, and patient preference.

In a 2016 population-based study, the 30-day recurrent stroke/TIA rate for patients hospitalized for TIA was 3% compared with 10.7% for those discharged from the ED with referral to a stroke clinic and 10.6% for those discharged from the ED without a referral to a stroke clinic.11 These data suggest that only patients for whom you have a low clinical suspicion of stroke/TIA should be worked up as outpatients, and that hospital admission is advised in moderate- and high-risk cases. The findings also highlight the critical role that primary care physicians can play in triaging and managing these patients for secondary prevention.

CASE › This patient’s recent history of sudden-onset right-sided weakness and expressive language dysfunction is suspicious for left hemispheric ischemia. She has several risk factors for stroke, and her ABCD2 score is 5 (hypertension, age ≥60 years, unilateral weakness, and duration 10-59 min), which places her at moderate risk. Thus, the recommendation would be to have her go directly to an ED for rapid evaluation.

The diagnostic work-up

Even when a patient is sent to the ED, the FP plays a critical role in his or her continuing care. FPs will often coordinate with inpatient care and manage transition of care to the outpatient setting. (And in many communities, the ED or hospital physicians may themselves be family practitioners.)

In terms of care, not even an aspirin should be administered in a case like this because the patient has not yet had any neuroimaging, and differentiation of ischemic from hemorrhagic stroke cannot be made on clinical grounds alone. Once an ischemic stroke is confirmed, determining the etiology is critical given the significant management differences between the different types of stroke (atherosclerotic, cardioembolic, lacunar, or other).

Which imaging method, and when?

While a computerized tomography (CT) scan is the preferred initial imaging strategy for acute stroke to discern the ischemic type from the hemorrhagic, MRI is preferred for the evaluation of acute ischemic stroke because the method has a higher sensitivity for infarction and a greater ability to identify findings (such as demyelination) that would suggest an alternative diagnosis.

In addition to evaluating the brain parenchyma, physicians must also assess the cerebral vasculature. CT angiography (CTA) or MR angiography (MRA) of the head and neck are preferred over carotid ultrasound because they are capable of evaluating the entire cerebrovascular system12,13 and can be instrumental in identifying potential causes of stroke, as well as guiding therapeutic decisions. Carotid ultrasound is a reasonable alternative for patients presenting with symptoms indicative of anterior circulation involvement when CTA and MRA are unavailable or contraindicated, but it will not identify intracranial vascular disease, proximal common carotid disease, or vertebrobasilar disease.

Getting to the cause of suspected stroke: Labs and other diagnostic tests

A routine work-up includes BP checks, routine labs (complete blood count, complete metabolic panel, coagulation profile, and troponin), an electrocardiogram (EKG), a transthoracic echocardiogram (TTE) with bubble study if possible, and a minimum of 24 to 48 hours of cardiac rhythm monitoring. Cardiac rhythm monitoring should be extended in the setting of clinical concern for unidentified paroxysmal atrial fibrillation, such as an embolism without a proximal vascular source, multiple embolic infarcts in different vascular territories, a dilated left atrium, or other risk factors for atrial fibrillation that include smoking, systolic hypertension, diabetes, and heart failure (see TABLE 312,13,17,18).14-16 This standard diagnostic work-up will identify the cause of stroke in 70% to 80% of patients.19

Additional investigations to consider if the etiology is not yet elucidated include a transesophageal echocardiogram (TEE), cerebral angiography, a coagulopathy evaluation, a lumbar puncture, and a vasculitis work-up. If available, consultation with a neurologist is appropriate for any patient who has had a stroke or TIA. Patients with unclear etiologies or for whom there are questions concerning strategies for preventing secondary stroke should be referred to Neurology and preferably a stroke specialist.

Timing matters, even when symptoms have resolved (ie, TIA).11,20 The EXPRESS trial17 (the Early use of eXisting PREventive Strategies for Stroke) looked at the effect of urgent assessment and treatment (≤1 day) of patients presenting with a TIA or minor stroke on the risk of recurrent stroke within 90 days. The diagnostic work-up included brain and vascular imaging together with an EKG. This intensive approach led to an absolute risk reduction of 8.2% (from 10.3% to 2.1%) in the risk of recurrent stroke at 90 days (number needed to treat [NNT]=12).17

Expedited work-up and treatment was also recently evaluated in a non-trial, real-world setting and was associated with reducing recurrent stroke by more than half the rate reported in older studies.20 Overall, the data suggest that evaluation within 24 hours confers substantial benefit, and that this evaluation can happen in an outpatient setting.21-23

Acute management: Use of tPA

Once imaging rules out intracranial hemorrhage, patients should be treated with tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) or an endovascular intervention as per guidelines.24 For patients with ischemic stroke ineligible for tPA or endovascular treatments, the initial focus is to determine the etiology of the symptoms so that the best strategies for prevention of secondary stroke may be employed.

Aspirin should be provided within 24 to 48 hours to all patients after intracranial hemorrhage is ruled out. Aspirin should be delayed for 24 hours in those given thrombolytics. The initial recommended dose of aspirin is 325 mg with continued low-dose (81 mg) aspirin daily.13 The addition of clopidogrel to aspirin within 24 hours of an event and continued for 21 days, followed by aspirin alone, was shown to be beneficial in a Chinese population with high-risk TIA (ABCD2 score ≥4) or minor stroke (National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale [NIHSS] ≤3).25 Anticoagulation with heparin, warfarin, or a novel oral anticoagulant is generally not indicated in the acute setting due to the risk of hemorrhagic transformation.

Acute BP management depends upon the type of stroke (ischemic or hemorrhagic), eligibility for thrombolytics, timing of presentation, and possible comorbidities such as myocardial infarction or aortic dissection (see TABLE 413,26). In the absence of contraindications, high-intensity statins should be initiated in all patients able to take oral medications.

CASE › You appropriately referred your patient to the local ED. A head CT with head and neck CTA was performed. While the head CT did not show any abnormalities, the CTA demonstrated high-grade left internal carotid artery stenosis. The patient was given an initial dose of aspirin 325 mg and a high-intensity statin and admitted for further management. An MRI revealed a small shower of emboli in the left hemisphere, confirming the diagnosis of stroke over TIA. Labs were marginally remarkable with a low-density lipoprotein level of 115 mg/dL and an HbA1c of 6.2. Telemetry monitoring did not reveal any arrhythmias, and TTE was normal. BP remained in the high-normal to low-hypertensive range.

A Vascular Surgery consultation was obtained and the patient underwent a left carotid endarterectomy the following day. She did well without surgical complications. Her BP medications were adjusted; a combination of an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor and a thiazide diuretic achieved a goal BP <140/90 mm Hg.

Permissive hypertension was not indicated due to her presentation >48 hours beyond the acute event. Low-dose aspirin and a high-intensity statin were continued, for secondary stroke prevention in the setting of atherosclerotic disease. She received smoking cessation counseling, which will continue.

CORRESPONDENCE

Stephen A. Martin, MD, EdM, Barre Family Health Center, 151 Worcester Road, Barre, MA 01005; stmartin@gmail.com.

1. Benjamin EJ, Blaha MJ, Chiuve SE, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics-2017 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2017;135:e146-e603.

2. Sacco RL, Kasner SE, Broderick JP, et al. An updated definition of stroke for the 21st century: a statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2013;44:2064-2089.

3. Kochanek KD, Murphy SL, Xu J, et al. Mortality in the United States, 2013. NCHS Data Brief. 2014:1-8. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db178.pdf. Accessed June 5, 2016.

4. Flossmann E, Redgrave JN, Briley D, et al. Reliability of clinical diagnosis of the symptomatic vascular territory in patients with recent transient ischemic attack or minor stroke. Stroke. 2008;39:2457-2460.

5. Josephson SA, Sidney S, Pham TN, et al. Higher ABCD2 score predicts patients most likely to have true transient ischemic attack. Stroke. 2008;39:3096-3098. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18688003. Accessed June 5, 2016.

6. Hankey GJ. The ABCD, California, and unified ABCD2 risk scores predicted stroke within 2, 7, and 90 days after TIA. Evid Based Med. 2007;12:88.

7. Sheehan OC, Kyne L, Kelly LA, et al. Population-based study of ABCD2 score, carotid stenosis, and atrial fibrillation for early stroke prediction after transient ischemic attack: the North Dublin TIA study. Stroke. 2010;41:844-850.

8. Rothwell PM, Giles MF, Flossmann E, et al. A simple score (ABCD) to identify individuals at high early risk of stroke after transient ischaemic attack. Lancet. 2005; 366:29-36.

9. Tsivgoulis G, Spengos K, Manta P, et al. Validation of the ABCD score in identifying individuals at high early risk of stroke after a transient ischemic attack: a hospital-based case series study. Stroke. 2006;37:2892-2897.

10. Kiyohara T, Kamouchi M, Kumai Y, et al. ABCD3 and ABCD3-I scores are superior to ABCD2 score in the prediction of short- and long-term risks of stroke after transient ischemic attack. Stroke. 2014;45:418-425.

11. Sacco RL, Rundek T. The value of urgent specialized care for TIA and minor stroke. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:1577-1579.

12. Demchuk AM, Menon BK, Goyal M. Comparing vessel imaging: noncontrast computed tomography/computed tomographic angiography should be the new minimum standard in acute disabling stroke. Stroke. 2016;47:273-281.

13. Jauch EC, Saver JL, Adams HP, et al. Guidelines for the early management of patients with acute ischemic stroke: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2013;44:870-947.

14. Gladstone DJ, Spring M, Dorian P, et al. Atrial fibrillation in patients with cryptogenic stroke. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:2467-2477.

15. Sanna T, Diener HC, Passman RS, et al. Cryptogenic stroke and underlying atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:2478-2486.

16. Christophersen IE, Yin X, Larson MG, et al. A comparison of the CHARGE-AF and the CHA2DS2-VASc risk scores for prediction of atrial fibrillation ni the Framingham Heart Study. Am Heart J. 2016;178:45-54.

17. Rothwell PM, Giles MF, Chandratheva A, et al. Effect of urgent treatment of transient ischaemic attack and minor stroke on early recurrent stroke (EXPRESS study): a prospective population-based sequential comparison. Lancet. 2007;370:1432-1442.

18. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Stroke and transient ischaemic attack in over 16s: diagnosis and initial management. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg68. Published 2008. Accessed February 5, 2017.

19. Hart RG, Diener HC, Coutts SB, et al. Embolic strokes of undetermined source: the case for a new clinical construct. Lancet Neurol. 2014;13:429-438.

20. Amarenco P, Lavallée PC, Labreuche J, et al. One-year risk of stroke after transient ischemic attack or minor stroke. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:1533-1542.

21. Joshi JK, Ouyang B, Prabhakaran S. Should TIA patients be hospitalized or referred to a same-day clinic? A decision analysis. Neurology. 2011;77:2082-2088.

22. Mijalski C, Silver B. TIA management: should TIA patients be admitted? should TIA patients get combination antiplatelet therapy? The Neurohospitalist. 2015;5:151-160.

23. Silver B, Adeoye O. Management of patients with transient ischemic attack in the emergency department. Neurology. 2016;86:1568-1569.

24. Demaerschalk BM, Kleindorfer DO, Adeoye OM, et al. Scientific rationale for the inclusion and exclusion criteria for intravenous alteplase in acute ischemic stroke: a statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2016;47:581-641.

25. Wang Y, Wang Y, Zhao X, et al. Clopidogrel with aspirin in acute minor stroke or transient ischemic attack. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:11-19.

26. Hemphill JC, Greenberg SM, Anderson CS, et al. Guidelines for the management of spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke. 2015;46:2032-2060.

1. Benjamin EJ, Blaha MJ, Chiuve SE, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics-2017 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2017;135:e146-e603.

2. Sacco RL, Kasner SE, Broderick JP, et al. An updated definition of stroke for the 21st century: a statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2013;44:2064-2089.

3. Kochanek KD, Murphy SL, Xu J, et al. Mortality in the United States, 2013. NCHS Data Brief. 2014:1-8. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db178.pdf. Accessed June 5, 2016.

4. Flossmann E, Redgrave JN, Briley D, et al. Reliability of clinical diagnosis of the symptomatic vascular territory in patients with recent transient ischemic attack or minor stroke. Stroke. 2008;39:2457-2460.

5. Josephson SA, Sidney S, Pham TN, et al. Higher ABCD2 score predicts patients most likely to have true transient ischemic attack. Stroke. 2008;39:3096-3098. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18688003. Accessed June 5, 2016.

6. Hankey GJ. The ABCD, California, and unified ABCD2 risk scores predicted stroke within 2, 7, and 90 days after TIA. Evid Based Med. 2007;12:88.

7. Sheehan OC, Kyne L, Kelly LA, et al. Population-based study of ABCD2 score, carotid stenosis, and atrial fibrillation for early stroke prediction after transient ischemic attack: the North Dublin TIA study. Stroke. 2010;41:844-850.

8. Rothwell PM, Giles MF, Flossmann E, et al. A simple score (ABCD) to identify individuals at high early risk of stroke after transient ischaemic attack. Lancet. 2005; 366:29-36.

9. Tsivgoulis G, Spengos K, Manta P, et al. Validation of the ABCD score in identifying individuals at high early risk of stroke after a transient ischemic attack: a hospital-based case series study. Stroke. 2006;37:2892-2897.

10. Kiyohara T, Kamouchi M, Kumai Y, et al. ABCD3 and ABCD3-I scores are superior to ABCD2 score in the prediction of short- and long-term risks of stroke after transient ischemic attack. Stroke. 2014;45:418-425.

11. Sacco RL, Rundek T. The value of urgent specialized care for TIA and minor stroke. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:1577-1579.

12. Demchuk AM, Menon BK, Goyal M. Comparing vessel imaging: noncontrast computed tomography/computed tomographic angiography should be the new minimum standard in acute disabling stroke. Stroke. 2016;47:273-281.

13. Jauch EC, Saver JL, Adams HP, et al. Guidelines for the early management of patients with acute ischemic stroke: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2013;44:870-947.

14. Gladstone DJ, Spring M, Dorian P, et al. Atrial fibrillation in patients with cryptogenic stroke. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:2467-2477.

15. Sanna T, Diener HC, Passman RS, et al. Cryptogenic stroke and underlying atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:2478-2486.

16. Christophersen IE, Yin X, Larson MG, et al. A comparison of the CHARGE-AF and the CHA2DS2-VASc risk scores for prediction of atrial fibrillation ni the Framingham Heart Study. Am Heart J. 2016;178:45-54.

17. Rothwell PM, Giles MF, Chandratheva A, et al. Effect of urgent treatment of transient ischaemic attack and minor stroke on early recurrent stroke (EXPRESS study): a prospective population-based sequential comparison. Lancet. 2007;370:1432-1442.

18. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Stroke and transient ischaemic attack in over 16s: diagnosis and initial management. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg68. Published 2008. Accessed February 5, 2017.

19. Hart RG, Diener HC, Coutts SB, et al. Embolic strokes of undetermined source: the case for a new clinical construct. Lancet Neurol. 2014;13:429-438.

20. Amarenco P, Lavallée PC, Labreuche J, et al. One-year risk of stroke after transient ischemic attack or minor stroke. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:1533-1542.

21. Joshi JK, Ouyang B, Prabhakaran S. Should TIA patients be hospitalized or referred to a same-day clinic? A decision analysis. Neurology. 2011;77:2082-2088.

22. Mijalski C, Silver B. TIA management: should TIA patients be admitted? should TIA patients get combination antiplatelet therapy? The Neurohospitalist. 2015;5:151-160.

23. Silver B, Adeoye O. Management of patients with transient ischemic attack in the emergency department. Neurology. 2016;86:1568-1569.

24. Demaerschalk BM, Kleindorfer DO, Adeoye OM, et al. Scientific rationale for the inclusion and exclusion criteria for intravenous alteplase in acute ischemic stroke: a statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2016;47:581-641.

25. Wang Y, Wang Y, Zhao X, et al. Clopidogrel with aspirin in acute minor stroke or transient ischemic attack. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:11-19.

26. Hemphill JC, Greenberg SM, Anderson CS, et al. Guidelines for the management of spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke. 2015;46:2032-2060.

PRACTICE RECOMMENDATIONS

› Perform an urgent work-up on patients presenting with symptoms of a transient ischemic attack or stroke. A

› Employ the ABCD2 risk stratification tool when determining whether it is reasonable to pursue an expedited work-up in the outpatient setting or recommend that a patient be evaluated in an emergency department. B

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series