User login

A 4-pronged approach to foster healthy aging in older adults

Our approach to caring for the growing number of community-dwelling US adults ages ≥ 65 years has shifted. Although we continue to manage disease and disability, there is an increasing emphasis on the promotion of healthy aging by optimizing health care needs and quality of life (QOL).

The American Geriatric Society (AGS) uses the term “healthy aging” to reflect a dedication to improving the health, independence, and QOL of older people.1 The World Health Organization (WHO) defines healthy aging as “the process of developing and maintaining the functional ability that enables well-being in older age.”2 Functional ability encompasses capabilities that align with a person’s values, including meeting basic needs; learning, growing, and making independent decisions; being mobile; building and maintaining healthy relationships; and contributing to society.2 Similarly, the US Department of Health and Human Services has adopted a multidimensional approach to support people in creating “a productive and meaningful life” as they grow older.3

Numerous theoretical models have emerged from research on aging as a multidimensional construct, as evidenced by a 2016 citation analysis that identified 1755 articles written between 1902 and 2015 relating to “successful aging.”4 The analysis revealed 609 definitions operationalized by researchers’ measurement tools (mostly focused on physical function and other health metrics) and 1146 descriptions created by older adults, many emphasizing psychosocial strategies and cultural factors as key to successful aging.4

One approach that is likely to be useful for family physicians is the Age-Friendly Health System. This is an initiative of The John A. Hartford Foundation and the Institute for Healthcare Improvement that uses a multidisciplinary approach to create environments that foster inclusivity and address the needs of older people.5 Following this guidance, primary care providers use evidence-informed strategies that promote safety and address what matters most to older adults and their family caregivers.

The Age-Friendly Health System, as well as AGS and WHO, recognize that there are multiple aspects to well-being as one grows older. By using focused, evidence-based screening, assessments, and interventions, family physicians can best support aging patients in living their most fulfilling lives.

Here we present a review of evidence-based strategies that promote safety and address what matters most to older adults and their family caregivers using a 4-pronged framework, in the style of the Age-Friendly Health System model. However, the literature on healthy aging includes important messages about patient context and lifelong health behaviors, which we capture in an expanded set of thematic guidance. As such, we encourage family physicians to approach healthy aging as follows: (1) monitor health (screening and prevention), (2) promote mobility (physical function), (3) manage mentation (emotional health and cognitive function), and (4) encourage maintenance of social connections (social networks and QOL).

Monitoring health

Leverage Medicare annual wellness visits. A systematic approach is needed to prevent frailty and functional decline, and thus increase the QOL of older adults. To do this, it is important to focus on health promotion and disease prevention, while addressing existing ailments. One method is to leverage the Medicare annual wellness visit (AWV), which provides an opportunity to assess current health status as well as discuss behavior-change and risk-reduction strategies with patients.

Continue to: Although AWVs...

Although AWVs are an opportunity to improve patient outcomes, we are not taking full advantage of them.6 While AWVs have gained traction since their introduction in 2011, usage rates among ethnoracial minority groups has lagged behind.6 A 2018 cohort study examined reasons for disparate utilization rates among individuals ages ≥ 66 years (N = 14,687).7 Researchers found that differences in utilization between ethnoracial groups were explained by socioeconomic factors. Lower education and lower income, as well as rural living, were associated with lower rates of AWV completion.7 In addition, having a usual, nonemergent place to obtain medical care served as a powerful predictor of AWV utilization for all groups.7

Strategies to increase AWV completion rates among all eligible adults include increasing staff awareness of health literacy challenges and ensuring communication strategies are inclusive by providing printed materials in multiple languages, Braille, or larger typefaces; using accessible vocabulary that does not include medical jargon; and making medical interpreters accessible. In addition, training clinicians about unconscious bias and cultural humility can help foster empathy and awareness of differences in health beliefs and behaviors within diverse patient populations.

A 2019 scoping review of 11 studies (N > 60 million) focused on outcomes from Medicare AWVs for patients ages ≥ 65 years.8 This included uptake of preventive services, such as vaccinations or cancer screenings; advice, education, or referrals offered during the AWV; medication use; and hospitalization rates. Overall findings showed that older adults who received a Medicare AWV were more likely to receive referrals for preventive screenings and follow-through on these recommendations compared with those who did not undergo an AWV.8

Completion rates for vaccines, while remaining low overall, were higher among those who completed an AWV. Additionally, these studies showed improved completion of screenings for breast cancer, bone density, and colon cancer. Several studies in the scoping review supported the use of AWVs as an effective means by which to offer health education and advice related to health promotion and risk reduction, such as diet and lifestyle modifications.8 Little evidence exists on long-term outcomes related to AWV completion.8

Utilize shared decision-making to determine whether preventive screening makes sense for your patient. Although cancer remains the second leading cause of death among Americans ages ≥ 65 years,9 clear screening guidelines for this age group remain elusive.10 Physicians and patients often are reluctant to stop cancer screening despite lower life expectancy and fewer potential benefits of diagnosis in this population.9 Some recent studies reinforce the heterogeneity of the older adult population and further underscore the importance of individual-level decision-making.11-14 It is important to let older adult patients and their caregivers know about the potential risks of screening tests, especially the possibility that incidental findings may lead to unwarranted additional care or monitoring.9

Continue to: Avoid these screening conversation missteps

Avoid these screening conversation missteps. A 2017 qualitative study asked 40 community-dwelling older adults (mean age = 76 years) about their preferences for discussing screening cessation with their physicians.13 Three themes emerged.First, they were open to stopping their screenings, especially when suggested by a trusted physician. Second, health status and physical function made sense as decision points, but life expectancy did not. Finally, lengthy discussions with expanded details about risks and benefits were not appreciated, especially if coupled with comments on the limited benefits for those nearing the end of life. When discussing life expectancy, patients preferred phrasing that focused on how the screening was unnecessary because it would not help them live longer.13

Ensure that your message is understood—and culturally relevant. Recent studies on lower health literacy among older adults15,16 and ethnic and racial minorities17-21—as revealed in the 2003 National Assessment of Adult Literacy22—might offer clues to patient receptivity to discussions about preventive screening and other health decisions.

One study found a significant correlation between higher self-rated health literacy and higher engagement in health behaviors such as mammography screening, moderate physical activity, and tobacco avoidance.16 Perceptions of personal control over health status, as well as perceived social standing, also correlated with health literacy score levels.16 Another study concluded that lower health literacy combined with lower self-efficacy, cultural beliefs about health topics (eg, diet and exercise), and distrust in the health care system contributed to lower rates of preventive care utilization among ethnocultural minority older adults in Canada, the United Kingdom, the United States, and Australia.18

Ensuring that easy-to-understand information is equitably shared with older adults of all races and ethnicities is critical. A 2018 study showed that distrust of the health system and cultural issues contributed to the lower incidence of colorectal cancer screenings in Hispanic and Asian American patients ages 50 to 75 years.21 Patients whose physicians engaged in “health literate practices” (eg, offering clear explanations of diagnostic plans and asking patients to describe what they understood) were more likely to obtain recommended breast and colorectal cancer screenings.20 In particular, researchers found that non-Hispanic Blacks were nearly twice as likely to follow through on colorectal cancer screening if their physicians engaged in health literate practices.20 In addition, receiving clear instructions from physicians increased the odds of completing breast cancer screening among Hispanic and non-Hispanic White women.20

Overall, screening information and recommendations should be standardized for all patients. This is particularly important in light of research that found that older non-Hispanic Black patients were less likely than their non-Hispanic White counterparts to receive information from their physicians about colorectal cancer screening.20

Continue to: Mobility

Mobility

Encourage physical activity. Frequent exercise and other forms of physical activity are associated with healthy aging, as shown in a 2017 systematic review and meta-analysis of 23 studies (N = 174,114).23 Despite considerable heterogeneity between studies in how researchers defined healthy aging and physical activity, they found that adults who incorporate regular movement and exercise into daily life are likely to continue to benefit from it into older age.23 In addition, a 2016 secondary analysis of data from the InCHIANTI longitudinal aging study concluded that adults ages ≥ 65 years (N = 1149) who had maintained higher physical activity levels throughout adulthood had less physical function decline and reduced rates of mobility disability and premature death compared with those who reported being less active.24

Preserve gait speed (and bolster health) with these activities. Walking speed, or gait, measured on a level surface has been used as a predictor for various aspects of well-being in older age, such as daily function, mobility, independence, falls, mortality, and hospitalization risk.25 Reduced gait speed is also one of the key indicators of functional impairment in older adults.

A 2015 systematic review sought to determine which type of exercise intervention (resistance, coordination, or multimodal training) would be most effective in preserving gait speed in healthy older adults (N = 2495; mean age = 74.2 years).25 While the 42 included studies were deemed to be fairly low quality, the review revealed (with large effect size [0.84]) that a number of exercise modalities might stave off loss of gait speed in older adults. Patients in the resistance training group had the greatest improvement in gait speed (0.11 m/s), followed by those in the coordination training group (0.09 m/s) and the multimodal training group (0.05 m/s).25

Finally, muscle mass and strength offer a measure of physical performance and functionality. A 2020 systematic review of 83 studies (N = 108,428) showed that low muscle mass and strength, reduced handgrip strength, and lower physical performance were predictive of reduced capacities in activities of daily living and instrumental activities of daily living.26 It is important to counsel adults to remain active throughout their lives and to include resistance training to maintain muscle mass and strength to preserve their motor function, mobility, independence, and QOL.

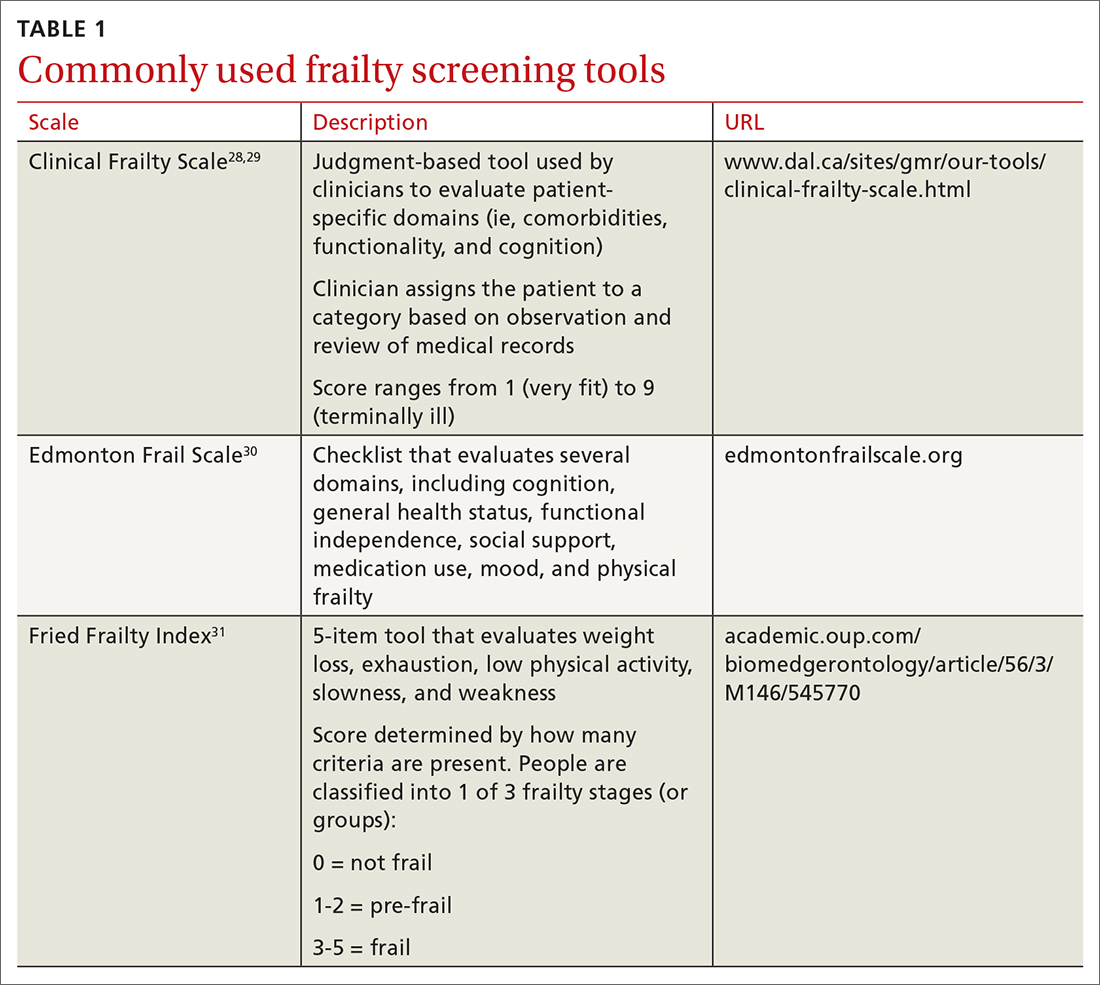

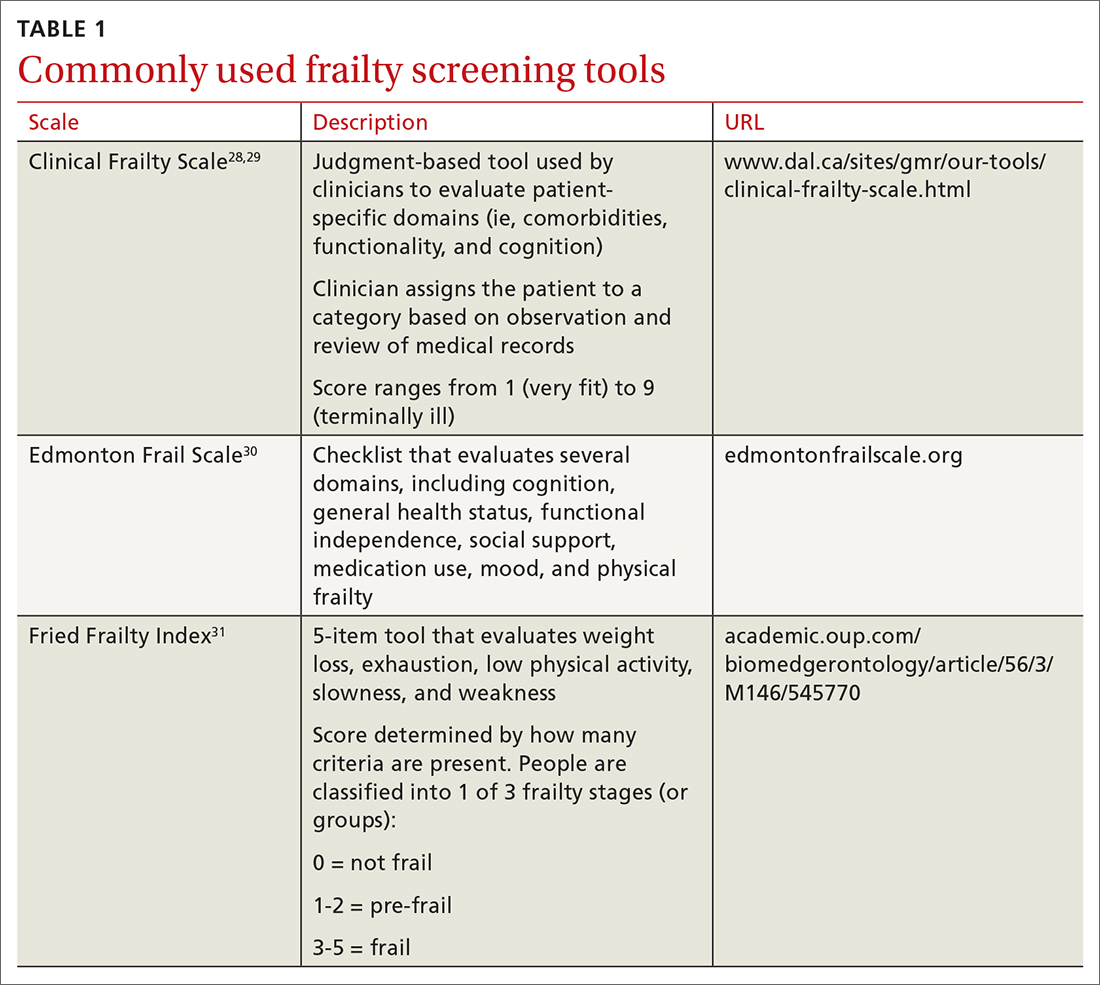

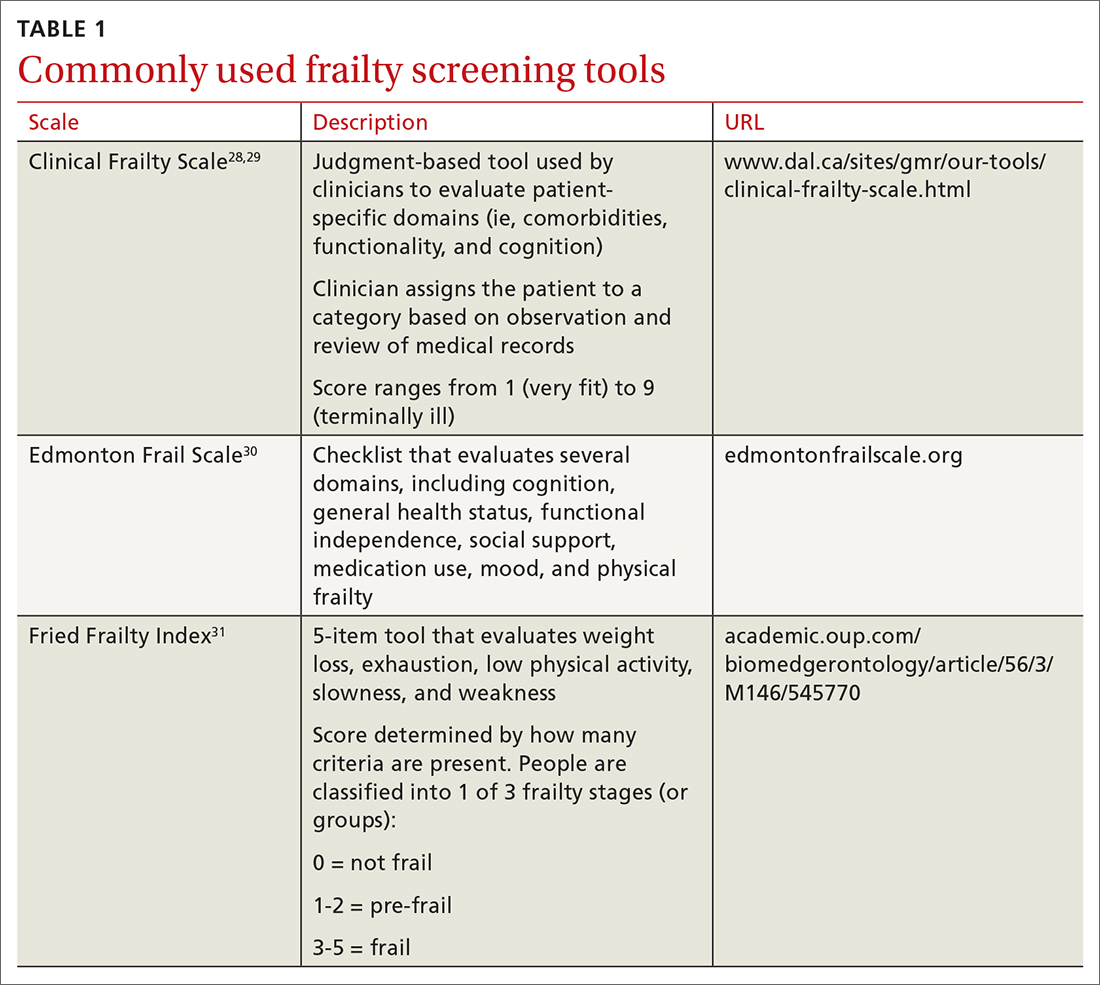

Use 1 of these scales to identify frailty. Frailty is a distinct clinical syndrome, in which an individual has low reserves and is highly vulnerable to internal and external stressors. It affects many community-dwelling older adults. Within the literature, there has been ongoing discussion regarding the definition of frailty27 (TABLE 128-31).

Continue to: The Fried Frailty Index...

The Fried Frailty Index defines frailty as a purely physical condition; patients need to exhibit 3 of 5 components (ie, weight loss, exhaustion, weakness, slowness, and low physical activity) to be deemed frail.31 The Edmonton Frail Scale is commonly used in geriatric assessments and counts impairments across several domains including physical activity, mood, cognition, and incontinence.30,32,33 Physicians need to complete a training course prior to its use. Finally, the definition of frailty used by Rockwood et al28, 29 was used to develop the Clinical Frailty Scale, which relies on broader criteria that include social and psychological elements in addition to physical elements.The Clinical Frailty Scale uses clinician judgment to evaluate patient-specific domains (eg, comorbidities, functionality, and cognition) and to generate a score ranging from 1 (very fit) to 9 (terminally ill).29 This scale is accessible and easy to implement. As a result, use of this scale has increased during the COVID-19 pandemic. All definitions include a pre-frail state, indicating the dynamic nature of frailty over time.

It is important to identify pre-frail and frail older adults using 1 of these screening tools. Interventions to reverse frailty that can be initiated in the primary care setting include identifying treatable medical conditions, assessing medication appropriateness, providing nutritional advice, and developing an exercise plan.34

Conduct a nutritional assessment; consider this diet. Studies show that nutritional status can predict physical function and frailty risk in older adults. A 2017 systematic review of 19 studies (N = 22,270) of frail adults ages ≥ 65 years found associations related to specific dietary constructs (ie, micronutrients, macronutrients, antioxidants, overall diet quality, and timing of consumption).35 Plant-based diets with higher levels of micronutrients, such as vitamins C and E and beta-carotene, or diets with more protein or macronutrients, regardless of source foods, all resulted in inverse associations with frailty syndrome.35

A 2017 study showed that physical exercise and maintaining good nutritional status may be effective for preventing frailty in community-dwelling pre-frail older individuals.36 A 2019 study showed that a combination of muscle strength training and protein supplementation was the most effective intervention to delay or reverse frailty and was easiest to implement in primary care.37 A 2020 meta-analysis of 31 studies (N = 4794) addressing frailty among primary care patients > 60 years showed that interventions using predominantly resistance-based exercise and nutrition supplementation improved frailty status over the control.38 Researchers also found that a comprehensive geriatric assessment or exercise—alone or in combination with nutrition education—reduced physical frailty.

Mentation

Screen and treat cognitive impairments. Cognitive function and autonomy in decision-making are important factors in healthy aging. Aspects of mental health (eg, depression and anxiety), sensory impairment (eg, visual and auditory impairment), and mentation issues (eg, delirium, dementia, and related conditions), as well as diet, physical exercise, and mobility, can all impede cognitive functionality. The long-term effects of depression, anxiety,39 sensory deficits,40 mobility,41 diet,42 and, ultimately, aging may impact Alzheimer disease (AD). The risk of an AD diagnosis increases with age.39

Continue to: A 2018 prospective cohort study...

A 2018 prospective cohort study using data from the National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center followed individuals (N = 12,053) who were cognitively asymptomatic at their initial visits to determine who developed clinical signs of AD.39 Survival analysis showed several psychosocial factors—anxiety, sleep disturbances, and depressive episodes of any type (occurring within the past 2 years, clinician verified, lifetime report)—were significantly associated with an eventual AD diagnosis and increased the risk of AD.39 More research is needed to verify the impact of early intervention for these conditions on neurodegenerative disease; however, screening and treating psychosocial factors such as anxiety and depression should be maintained.

Researchers evaluated the impact of a dual sensory impairment (DSI) on dementia risk using data from 2051 participants in the Ginkgo Evaluation of Memory Study.40 Hearing and visual impairments (defined as DSI when these conditions coexist) or visual impairment alone were significantly associated with increased risk of dementia in older adults. The researchers reported that DSI was significantly associated with a higher risk of all-cause dementia (hazard ratio [HR] = 1.86; 95% CI, 1.25-2.76) and AD (HR = 2.12; 95% CI, 1.34-3.36).40 Visual impairment alone was associated with an increased risk of all-cause dementia (HR = 1.32; 95% CI, 1.02-1.71).40 These results suggest that screening of DSI or visual impairment earlier in the patient’s lifespan may identify those at high risk of dementia in older adulthood.

The American Academy of Ophthalmology recommends patients with healthy eyes be screened once during their 20s and twice in their 30s; a full examination is recommended by age 40. For patients ages ≥ 65 years, it is recommended that eye examinations occur every 1 to 2 years.43

Diet and mobility play a big role in cognition. Diet43 and exercise41,42,44 are believed to have an impact on mentation, and recent studies show memory and global cognition could be malleable later in life. A 2015 meta-analysis of 490 treatment arms of 24 randomized controlled studies showed improvement in global cognition with consumption of a Mediterranean diet plus olive oil (effect size [ES] standardized mean difference [SMD] = 0.22; 95% CI, 0.16-0.27) and tai chi exercises (ES SMD = 0.18; 95% CI, 0.06-0.29).42 The analysis also found improved memory among participants who consumed the Mediterranean diet/olive oil combination (ES SMD = 0.22; 95% CI, 0.12-0.32) and soy isoflavone supplements (ES SMD = 0.11; 95% CI, 0.04-0.17). Although the ESs are small, they are significant and offer promising evidence that individual choices related to nutrition or exercise may influence cognition and memory.

A 2018 systematic review found that all domains of cognition showed improvement with 45 to 60 minutes of moderate-to-vigorous physical exercise.44 Attention, executive function, memory, and working memory showed significant increases, whereas global cognition improvements were not statistically significant.44 A 2016 meta-analysis of 26 studies (N = 26,355) found a positive association between an objective mobility measure (gait, lower-extremity function, and balance) and cognitive function (global, executive function, memory, and processing speed) in older adults.41 These results highlight that diet, mobility, and physical exercise impact cognitive functioning.

Continue to: Maintaining social connections

Maintaining social connections

Social isolation and loneliness—compounded by a pandemic. The US Department of Health and Human Services notes that “community connections” are among the key factors required for healthy aging.3 Similarly, the WHO definition of healthy aging considers whether individuals can build and sustain relationships with other people and find ways to engender their personal values through these connections.2

As people age, their social connections often decrease due to the death of friends and family, shifts in living arrangements, loss of mobility or eyesight (and thus self-transport), and the onset or increased acuity of illness or chronic conditions.45 This has been exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic, which has spurred shelter-in-place and stay-at-home orders along with recommendations for physical distancing (also known as social distancing), especially for older adults who are at higher risk.46 Smith et al47 calls this the COVID-19 Social Connectivity Paradox, in which older adults limit their interactions with others to protect their physical health and reduce their risk of contracting the virus, but as a result they may undermine their psychosocial health by placing themselves at risk of social isolation and loneliness.47

The double threat. Social isolation and loneliness have been shown to negatively impact physical health and well-being, resulting in an increased risk of early death48-50; higher likelihood of specific diagnoses, including dementia and cardiovascular conditions48,50; and more frequent use of health care services.50 These concepts, while related, represent different mechanisms for negative health outcomes. Social isolation is an objective condition when one has a lack of opportunities for interaction with other people; loneliness refers to the emotional disconnect one feels when separated from others. Few studies have compared outcomes between these concepts, but in those that have, social isolation appears to be more strongly associated with early death.48-50

A 2013 observational study using data from the English Longitudinal Study on Aging found that both social isolation and loneliness were associated with increased mortality among men and women ages ≥ 52 years (N = 6500).48 However, when studied independently, loneliness was not found to be a significant risk factor. In contrast, social isolation significantly impacted mortality risk, even after adjusting for demographic factors and baseline health status.48 These findings are supported by a 2018 cohort study of individuals (N = 479,054) with a history of an acute cardiovascular event that concluded social isolation was a predictor of mortality, whereas loneliness was not.50

A large 2015 meta-analysis (70 studies, N = 3,407,134) of mortality causes among community-dwelling older adults (average age, 66) confirmed that both objective measures of isolation, as well as subjective measures (such as feelings of loneliness or living alone), have a significant predictive effect in longer-term studies. Each measure shows an approximately 30% increase in the likelihood of death after an average of 7 years.49

Continue to: Health care remains a connection point

Health care remains a connection point. Even when life course events and conditions (eg, death of loved ones, loss of transportation or financial resources, or disengagement from community activities) reduce social connections, most older adults engage in some way with the health care system. A 2020 consensus report by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine suggests health care professionals capitalize on these connection points with adults ages ≥ 50 years by periodically screening for social isolation and loneliness, documenting social status updates in medical records, and piloting and evaluating interventions in the clinical setting.51

The report offered information about potential avenues for intervention by primary care professionals beyond screening, such as participating in research studies that investigate screening tools and multisystem interventions; social prescribing (linking patients to embedded social work services or community-based organizations); referring patients to support groups; initiating cognitive-based therapy or other behavioral health interventions; or recommending mindfulness practices.51 However, most of the cited intervention studies were not specific to primary care settings and contained poor-quality evidence related to efficacy.

Isolation creates a greater reliance on health services due to a lack of a social support system, while a feeling of emotional disconnection (loneliness) seems to be a barrier to accessing care. A 2017 cohort study linking data from the Health and Retirement Study and Medicare claims revealed that social isolation predicts higher annual health expenditures (> $1600 per beneficiary) driven by hospitalization and skilled nursing facility usage, along with greater mortality, whereas individuals who are lonely result in reduced costs (a reduction of $770 annually) due to lower usage of inpatient and outpatient services.52 Prioritizing interventions that identify and connect isolated older adults to social support, therefore, may increase survivability by ensuring they have access to resources and health care interventions when needed.

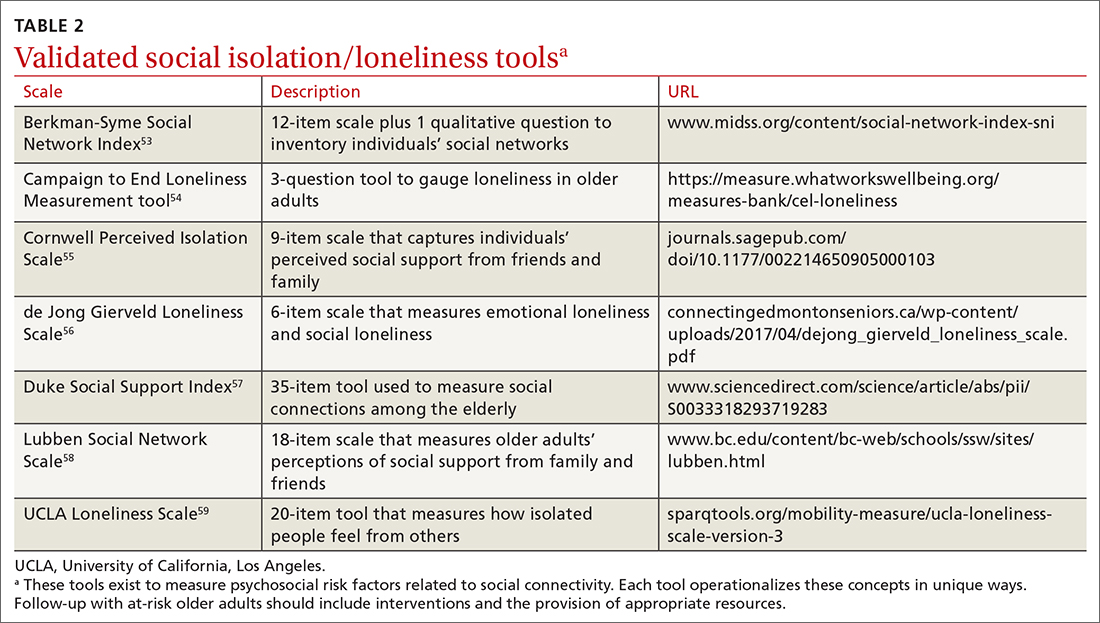

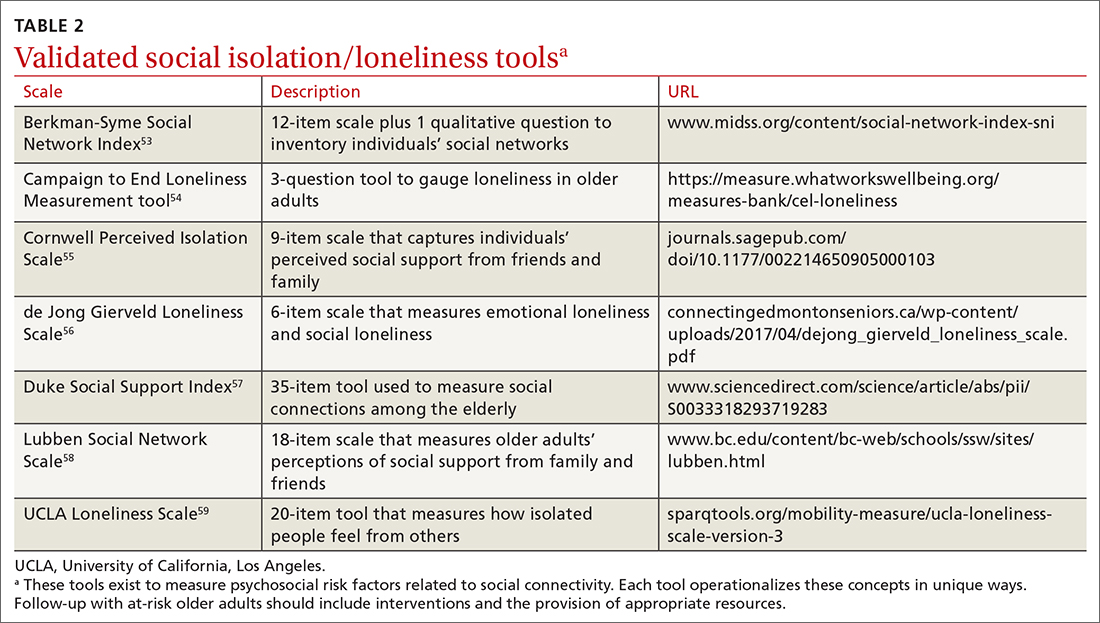

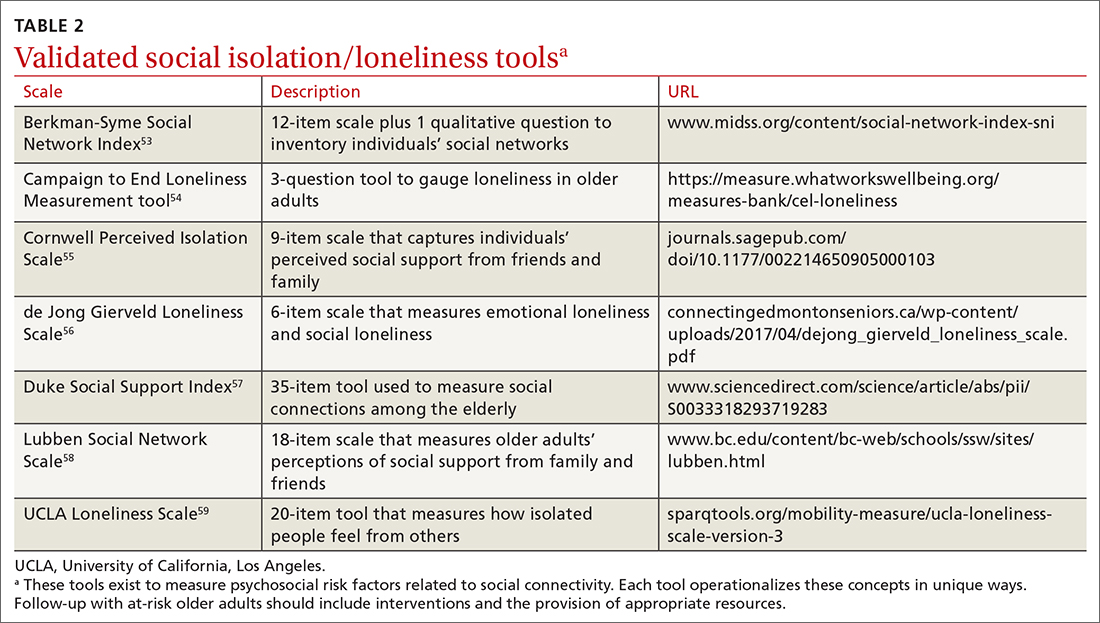

In addition, these findings underscore the importance of looking at quality—not just quantity—of older adults’ social connections. A number of validated screening tools exist for social isolation and loneliness (TABLE 253-59); however, concerns exist about assessing risk using a unidimensional tool for a complex concern,47 as well as identifying a problem without having evidence-based interventions to offer as solutions.47,51 Until future studies resolve these concerns, leveraging the physician-patient relationship to broach these difficult subjects may help normalize the issues and create safe spaces to identify individuals who are at risk.

QOL is key to healthy aging. As Kusumastuti et al4 state, “successful ageing lies in the eyes of the beholder.” A 2019 systematic review of 48 qualitative studies revealed that community-dwelling older adults ages ≥ 50 years in 11 countries (N > 4175) perceive well-being by considering QOL within 9 domains: health perception, autonomy, role and activity, relationships, emotional comfort, attitude and adaptation, spirituality, financial security, and home and neighborhood.60 Researchers found that as engagement in any one of these domains declines, older adults may shift their definition of health toward their remaining abilities.60 This offers an explanation as to why patients might rate their health status much higher than their physicians do: older adults tend to have a more holistic concept of health.

Continue to: Take a multidimensional approach to healthy aging

Take a multidimensional approach to healthy aging

Although we have separately examined each of the 4 components of managing healthy aging in a community-dwelling adult, applying a multidimensional approach is most effective. Increasing use of the Medicare AWV provides an opportunity to assess patient health status, determine care preferences, and improve follow-through on preventive screening. It is also important to encourage older adults to engage in regular physical activity—especially muscle-strengthening exercises—and to discuss nutrition and caloric intake to prevent frailty and functional decline.

Assessing and treating vision and hearing impairments and mental health issues, including anxiety and depression, may guard against losses in cognition. When speaking with older adult patients about their social connections, consider asking not only about frequency of contact and access to resources such as food and transportation, but also about whether they are finding ways to bring their own values into those relationships to bolster their QOL. This guidance also may be useful for primary care practices and health care networks when planning future quality-improvement initiatives.

Additional research is needed to support the evidence base for aligning older adult preferences in health care interventions, such as preventive screenings. Also, clinical decision-making requires more clarity about the efficacy of specific diet and exercise interventions for older adults; the impact of early intervention for depression, anxiety, and sleep disorders on neurodegenerative disease; whether loneliness predicts mortality; and how health care delivery systems can be effective at building social connectivity.

For now, it is essential to recognize that initiating health education, screening, and prevention throughout the patient’s lifespan can promote healthy aging outcomes. As family physicians, it is important to capitalize on longitudinal relationships with patients and begin educating younger patients using this multidimensional framework to promote living “a productive and meaningful life”at any age.3

Lynn M. Wilson, DO, 707 Hamilton Street, 8th floor, Department of Family Medicine, Lehigh Valley Health Network, Allentown, PA 18101; lynn_m.wilson@lvhn.org

1. Friedman S, Mulhausen P, Cleveland M, et al. Healthy aging: American Geriatrics Society white paper executive summary. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2018;67:17-20. doi: 10.1111/jgs.15644

2. World Health Organization. World report on ageing and health. 2015. Accessed June 29, 2020. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/186463/9789240694811_eng.pdf?sequence=1

3. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. Healthy aging. Accessed June 29, 2020. www.hhs.gov/aging/healthy-aging

4. Kusumastuti S, Derks MGM, Tellier S, et al. Successful ageing: a study of the literature using citation network analysis. Maturitas. 2016;93:4-12. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2016.04.010

5. Institute for Healthcare Improvement. Age-friendly health systems: guide to using the 4Ms in the care of older adults [white paper]. 2020. Accessed June 29, 2020. www.ihi.org/Engage/Initiatives/Age-Friendly-Health-systems/Documents/IHIAgeFriendlyHealthSystems_GuidetoUsing4MsCare.pdf

6. Lind KE, Hildreth KL, Perraillon MC. Persistent disparities in Medicare’s annual wellness visit utilization. Med Care. 2019;57:984-989. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000001229

7. Lind KE, Hildreth K, Lindrooth R, et al. Ethnoracial disparities in Medicare annual wellness visit utilization: evidence from a nationally representative database. Med Care. 2018;56:761-766. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000962

8. Simpson VL, Kovich M. Outcomes of primary care-based Medicare annual wellness visits with older adults: a scoping review. Geriatr Nurs. 2019;40:590-596. doi: 10.1016/j.gerinurse.2019.06.001

9. Heron M. Deaths: leading causes for 2017. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2019;68:1-77.

10. Salzman B, Beldowski K, de la Paz A. Cancer screening in older patients. Am Fam Physician. 2016;93:659-667.

11. Kinsinger LS, Anderson C, Kim J, et al. Implementation of lung cancer screening in the Veterans Health Administration. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177:399-406. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.9022

12. Walter LC, Schonberg MA. Screening mammography in older women: a review. JAMA. 2014;311:1336-1347. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.2834

13. Schoenborn NL, Lee K, Pollack CE, et al. Older adults’ views and communication preferences about cancer screening cessation. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177:1121-1128. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.1778

14. Butterworth JE, Hays R, McDonagh ST, et al. Interventions for involving older patients with multi-morbidity in decision-making during primary care consultations. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;10:CD013124. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD013124.pub2

15. Bostock S, Steptoe A. Association between low functional health literacy and mortality in older adults: longitudinal cohort study. BMJ. 2012;344:e1602. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e1602

16. Fernandez DM, Larson JL, Zikmund-Fisher BJ. Associations between health literacy and preventive health behaviors among older adults: findings from the health and retirement study. BMC Public Health. 2016;16:596. doi: 10.1186/s12889-016-3267-7

17. Weekes CV. African Americans and health literacy: a systematic review. ABNF J. 2012;23:76-80.

18. Mantwill S, Monestel-Umaña S, Schulz PJ. The relationship between health literacy and health disparities: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0145455. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0145455

19. Khan MM, Kobayashi K. Optimizing health promotion among ethnocultural minority older adults (EMOA). Int J Migration Health Soc Care. 2015;11:268-281. doi: 10.1108/IJMHSC-12-2014-0047

20. Kindratt TB, Dallo FJ, Allicock M, et al. The influence of patient-provider communication on cancer screenings differs among racial and ethnic groups. Prev Med Rep. 2020;18:101086. doi: 10.1016/j.pmedr.2020.101086

21. Hong Y-R, Tauscher J, Cardel M. Distrust in health care and cultural factors are associated with uptake of colorectal cancer screening in Hispanic and Asian Americans. Cancer. 2018;124:335-345. doi: 10.1002/cncr.31052

22. Kutner M, Greenberg E, Jin Y, et al. Literacy in everyday life: results from the 2003 National Assessment of Adult Literacy. NCES 2007-480. U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics. April 2007. Accessed August 27, 2021. http://nces.ed.gov/Pubs2007/2007480_1.pdf

23. Daskalopoulou C, Stubbs B, Kralj C, et al. Physical activity and healthy ageing: a systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal cohort studies. Ageing Res Rev. 2017;38:6-17. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2017.06.003

24. Stenholm S, Koster A, Valkeinen H, et al. Association of physical activity history with physical function and mortality in old age. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2016;71:496-501. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glv111

25. Hortobágyi T, Lesinski M, Gäbler M, et al. Effects of three types of exercise interventions on healthy old adults’ gait speed: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Med. 2015;45:1627‐1643. Published correction appears in Sports Med. 2016;46:453. doi: 10.1007/s40279-015-0371-2

26. Wang DXM, Yao J, Zirek Y, et al. Muscle mass, strength, and physical performance predicting activities of daily living: a meta-analysis. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2020;11:3‐25. doi: 10.1002/jcsm.12502

27. Sternberg SA, Wershof Schwartz A, Karunananthan S, et al. The identification of frailty: a systematic literature review. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59:2129-2138. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03597.x

28. Rockwood K, Song X, MacKnight C, et al. A global clinical measure of fitness and frailty in elderly people. CMAJ. 2005;173:489-495. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.050051

29. Church S, Rogers E, Rockwood K, et al. A scoping review of the Clinical Frailty Scale. BMC Geriatr. 2020;20:393. doi: 10.1186/s12877-020-01801-7

30. Rolfson DB, Majumdar SR, Tsuyuki RT, et al. Validity and reliability of the Edmonton Frail Scale. Age Ageing. 2006;35:526-529. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afl041

31. Fried LP, Tangen CM, Walston J, et al. Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2001;56:M146-M156. doi: 10.1093/gerona/56.3.m146

32. Dent E, Kowal P, Hoogendijk EO. Frailty measurement in research and clinical practice: a review. Euro J Intern Med. 2016;31:3-10. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2016.03.007

33. Perna S, Francis MD, Bologna C, et al. Performance of Edmonton Frail Scale on frailty assessment: its association with multi-dimensional geriatric conditions assessed with specific screening tools. BMC Geriatr. 2017;17:2. doi: 10.1186/s12877-016-0382-3

34. Chen CY, Gan P, How CH. Approach to frailty in the elderly in primary care and the community. Singapore Med J. 2018;59:338. doi: 10.11622/smedj.2018052

35. Lorenzo-López L, Maseda A, de Labra C, et al. Nutritional determinants of frailty in older adults: a systematic review. BMC Geriatr. 2017;17:108. doi: 10.1186/s12877-017-0496-2

36. Serra-Prat M, Sist X, Domenich R, et al. Effectiveness of an intervention to prevent frailty in pre-frail community-dwelling older people consulting in primary care: a randomised controlled trial. Age Ageing. 2017;46:401-407. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afw242

37. Travers J, Romero-Ortuno R, Bailey J, et al. Delaying and reversing frailty: a systematic review of primary care interventions. Br J Gen Pract. 2019;69:e61-e69. doi: 10.3399/bjgp18X700241

38. Macdonald SHF, Travers J, Shé ÉN, et al. Primary care interventions to address physical frailty among community-dwelling adults aged 60 years or older: a meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2020;15:e0228821. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0228821

39. Burke SL, Cadet T, Alcide A, et al. Psychosocial risk factors and Alzheimer’s disease: the associative effect of depression, sleep disturbance, and anxiety. Aging Ment Health. 2018;22:1577-1584. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2017.1387760

40. Hwang PH, Longstreth WT Jr, Brenowitz WD, et al. Dual sensory impairment in older adults and risk of dementia from the GEM Study. Alzheimers Dement (Amst). 2020;12:e12054. doi: 10.1002/dad2.12054

41. Demnitz N, Esser P, Dawes H, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of cross-sectional studies examining the relationship between mobility and cognition in healthy older adults. Gait Posture. 2016;50:164‐174. doi: 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2016.08.028

42. Lehert P, Villaseca P, Hogervorst E, et al. Individually modifiable risk factors to ameliorate cognitive aging: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Climacteric. 2015;18:678-689. doi: 10.3109/13697137.2015.1078106

43. Turbert D. Eye exam and vision testing basics. American Academy of Ophthalmology Web site. January 14, 2021. Accessed March 5, 2021. www.aao.org/eye-health/tips-prevention/eye-exams-101

44. Northey JM, Cherbuin N, Pumpa KL, et al. Exercise interventions for cognitive function in adults older than 50: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med. 2018;52:154-160. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2016-096587

45. CDC. Percent of U.S. adults 55 and over with chronic conditions. November 6, 2015. Accessed April 29, 2021. www.cdc.gov/nchs/health_policy/adult_chronic_conditions.htm

46. National Council on Aging. COVID-driven isolation can be dangerous for older adults. March 31, 2021. Accessed April 29, 2021. www.ncoa.org/article/covid-driven-isolation-can-be-dangerous-for-older-adults

47. Smith ML, Steinman LE, Casey EA. Combatting social isolation among older adults in a time of physical distancing: the COVID-19 social connectivity paradox. Front Public Health. 2020;8:403. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2020.00403

48. Steptoe A, Shankar A, Demakakos P, et al. Social isolation, loneliness, and all-cause mortality in older men and women. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:5797-5801. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1219686110

49. Holt-Lunstad J, Smith TB, Baker M, et al. Loneliness and social isolation as risk factors for mortality: a meta-analytic review. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2015;10:227-237. doi: 10.1177/1745691614568352

50. Hakulinen C, Pulkki-Råback L, Virtanen M, et al. Social isolation and loneliness as risk factors for myocardial infarction, stroke and mortality: UK Biobank cohort study of 479 054 men and women. Heart. 2018;104:1536-1542. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2017-312663

51. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Social Isolation and Loneliness in Older Adults: Opportunities for the Health Care System. The National Academies Press; 2020. doi: 10.17226/25663

52. Shaw JG, Farid M, Noel-Miller C, et al. Social isolation and Medicare spending: among older adults, objective isolation increases expenditures while loneliness does not. J Aging Health. 2017;29:1119-1143. doi: 10.1177/0898264317703559

53. Berkman LF, Syme SL. Social networks, host resistance, and mortality: a nine-year follow-up study of Alameda County residents. Am J Epidemiol. 1979;109:186-204. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a112674

54. Campaign to End Loneliness. Measuring your impact on loneliness in later life. Accessed April 29, 2021. www.campaigntoendloneliness.org/wp-content/uploads/Loneliness-Measurement-Guidance1-1.pdf

55. Cornwell EY, Waite LJ. Social disconnectedness, perceived isolation, and health among older adults. J Health Soc Behav. 2009;50:31-48. doi: 10.1177/002214650905000103

56. Gierveld JDJ, Van Tilburg T. A 6-item scale for overall, emotional, and social loneliness: confirmatory tests on survey data. Res Aging. 2006;28:582-598. doi: 10.1177/0164027506289723

57. Koenig HG, Westlund RE, George LK, et al. Abbreviating the Duke Social Support Index for use in chronically ill elderly individuals. Psychosomatics. 1993;34:61-69. doi: 10.1016/S0033-3182(93)71928-3

58. Lubben J, Blozik E, Gillmann G, et al. Performance of an abbreviated version of the Lubben Social Network Scale among three European community-dwelling older adult populations. Gerontologist. 2006;46:503-513. doi: 10.1093/geront/46.4.503

59. Russell DW. UCLA Loneliness Scale (version 3): reliability, validity, factor structure. J Pers Assess. 1996;66:20-40. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa6601_2

60. van Leeuwen KM, van Loon MS, van Nes FA, et al. What does quality of life mean to older adults? A thematic synthesis. PLoS One. 2019;14:e0213263. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0213263

Our approach to caring for the growing number of community-dwelling US adults ages ≥ 65 years has shifted. Although we continue to manage disease and disability, there is an increasing emphasis on the promotion of healthy aging by optimizing health care needs and quality of life (QOL).

The American Geriatric Society (AGS) uses the term “healthy aging” to reflect a dedication to improving the health, independence, and QOL of older people.1 The World Health Organization (WHO) defines healthy aging as “the process of developing and maintaining the functional ability that enables well-being in older age.”2 Functional ability encompasses capabilities that align with a person’s values, including meeting basic needs; learning, growing, and making independent decisions; being mobile; building and maintaining healthy relationships; and contributing to society.2 Similarly, the US Department of Health and Human Services has adopted a multidimensional approach to support people in creating “a productive and meaningful life” as they grow older.3

Numerous theoretical models have emerged from research on aging as a multidimensional construct, as evidenced by a 2016 citation analysis that identified 1755 articles written between 1902 and 2015 relating to “successful aging.”4 The analysis revealed 609 definitions operationalized by researchers’ measurement tools (mostly focused on physical function and other health metrics) and 1146 descriptions created by older adults, many emphasizing psychosocial strategies and cultural factors as key to successful aging.4

One approach that is likely to be useful for family physicians is the Age-Friendly Health System. This is an initiative of The John A. Hartford Foundation and the Institute for Healthcare Improvement that uses a multidisciplinary approach to create environments that foster inclusivity and address the needs of older people.5 Following this guidance, primary care providers use evidence-informed strategies that promote safety and address what matters most to older adults and their family caregivers.

The Age-Friendly Health System, as well as AGS and WHO, recognize that there are multiple aspects to well-being as one grows older. By using focused, evidence-based screening, assessments, and interventions, family physicians can best support aging patients in living their most fulfilling lives.

Here we present a review of evidence-based strategies that promote safety and address what matters most to older adults and their family caregivers using a 4-pronged framework, in the style of the Age-Friendly Health System model. However, the literature on healthy aging includes important messages about patient context and lifelong health behaviors, which we capture in an expanded set of thematic guidance. As such, we encourage family physicians to approach healthy aging as follows: (1) monitor health (screening and prevention), (2) promote mobility (physical function), (3) manage mentation (emotional health and cognitive function), and (4) encourage maintenance of social connections (social networks and QOL).

Monitoring health

Leverage Medicare annual wellness visits. A systematic approach is needed to prevent frailty and functional decline, and thus increase the QOL of older adults. To do this, it is important to focus on health promotion and disease prevention, while addressing existing ailments. One method is to leverage the Medicare annual wellness visit (AWV), which provides an opportunity to assess current health status as well as discuss behavior-change and risk-reduction strategies with patients.

Continue to: Although AWVs...

Although AWVs are an opportunity to improve patient outcomes, we are not taking full advantage of them.6 While AWVs have gained traction since their introduction in 2011, usage rates among ethnoracial minority groups has lagged behind.6 A 2018 cohort study examined reasons for disparate utilization rates among individuals ages ≥ 66 years (N = 14,687).7 Researchers found that differences in utilization between ethnoracial groups were explained by socioeconomic factors. Lower education and lower income, as well as rural living, were associated with lower rates of AWV completion.7 In addition, having a usual, nonemergent place to obtain medical care served as a powerful predictor of AWV utilization for all groups.7

Strategies to increase AWV completion rates among all eligible adults include increasing staff awareness of health literacy challenges and ensuring communication strategies are inclusive by providing printed materials in multiple languages, Braille, or larger typefaces; using accessible vocabulary that does not include medical jargon; and making medical interpreters accessible. In addition, training clinicians about unconscious bias and cultural humility can help foster empathy and awareness of differences in health beliefs and behaviors within diverse patient populations.

A 2019 scoping review of 11 studies (N > 60 million) focused on outcomes from Medicare AWVs for patients ages ≥ 65 years.8 This included uptake of preventive services, such as vaccinations or cancer screenings; advice, education, or referrals offered during the AWV; medication use; and hospitalization rates. Overall findings showed that older adults who received a Medicare AWV were more likely to receive referrals for preventive screenings and follow-through on these recommendations compared with those who did not undergo an AWV.8

Completion rates for vaccines, while remaining low overall, were higher among those who completed an AWV. Additionally, these studies showed improved completion of screenings for breast cancer, bone density, and colon cancer. Several studies in the scoping review supported the use of AWVs as an effective means by which to offer health education and advice related to health promotion and risk reduction, such as diet and lifestyle modifications.8 Little evidence exists on long-term outcomes related to AWV completion.8

Utilize shared decision-making to determine whether preventive screening makes sense for your patient. Although cancer remains the second leading cause of death among Americans ages ≥ 65 years,9 clear screening guidelines for this age group remain elusive.10 Physicians and patients often are reluctant to stop cancer screening despite lower life expectancy and fewer potential benefits of diagnosis in this population.9 Some recent studies reinforce the heterogeneity of the older adult population and further underscore the importance of individual-level decision-making.11-14 It is important to let older adult patients and their caregivers know about the potential risks of screening tests, especially the possibility that incidental findings may lead to unwarranted additional care or monitoring.9

Continue to: Avoid these screening conversation missteps

Avoid these screening conversation missteps. A 2017 qualitative study asked 40 community-dwelling older adults (mean age = 76 years) about their preferences for discussing screening cessation with their physicians.13 Three themes emerged.First, they were open to stopping their screenings, especially when suggested by a trusted physician. Second, health status and physical function made sense as decision points, but life expectancy did not. Finally, lengthy discussions with expanded details about risks and benefits were not appreciated, especially if coupled with comments on the limited benefits for those nearing the end of life. When discussing life expectancy, patients preferred phrasing that focused on how the screening was unnecessary because it would not help them live longer.13

Ensure that your message is understood—and culturally relevant. Recent studies on lower health literacy among older adults15,16 and ethnic and racial minorities17-21—as revealed in the 2003 National Assessment of Adult Literacy22—might offer clues to patient receptivity to discussions about preventive screening and other health decisions.

One study found a significant correlation between higher self-rated health literacy and higher engagement in health behaviors such as mammography screening, moderate physical activity, and tobacco avoidance.16 Perceptions of personal control over health status, as well as perceived social standing, also correlated with health literacy score levels.16 Another study concluded that lower health literacy combined with lower self-efficacy, cultural beliefs about health topics (eg, diet and exercise), and distrust in the health care system contributed to lower rates of preventive care utilization among ethnocultural minority older adults in Canada, the United Kingdom, the United States, and Australia.18

Ensuring that easy-to-understand information is equitably shared with older adults of all races and ethnicities is critical. A 2018 study showed that distrust of the health system and cultural issues contributed to the lower incidence of colorectal cancer screenings in Hispanic and Asian American patients ages 50 to 75 years.21 Patients whose physicians engaged in “health literate practices” (eg, offering clear explanations of diagnostic plans and asking patients to describe what they understood) were more likely to obtain recommended breast and colorectal cancer screenings.20 In particular, researchers found that non-Hispanic Blacks were nearly twice as likely to follow through on colorectal cancer screening if their physicians engaged in health literate practices.20 In addition, receiving clear instructions from physicians increased the odds of completing breast cancer screening among Hispanic and non-Hispanic White women.20

Overall, screening information and recommendations should be standardized for all patients. This is particularly important in light of research that found that older non-Hispanic Black patients were less likely than their non-Hispanic White counterparts to receive information from their physicians about colorectal cancer screening.20

Continue to: Mobility

Mobility

Encourage physical activity. Frequent exercise and other forms of physical activity are associated with healthy aging, as shown in a 2017 systematic review and meta-analysis of 23 studies (N = 174,114).23 Despite considerable heterogeneity between studies in how researchers defined healthy aging and physical activity, they found that adults who incorporate regular movement and exercise into daily life are likely to continue to benefit from it into older age.23 In addition, a 2016 secondary analysis of data from the InCHIANTI longitudinal aging study concluded that adults ages ≥ 65 years (N = 1149) who had maintained higher physical activity levels throughout adulthood had less physical function decline and reduced rates of mobility disability and premature death compared with those who reported being less active.24

Preserve gait speed (and bolster health) with these activities. Walking speed, or gait, measured on a level surface has been used as a predictor for various aspects of well-being in older age, such as daily function, mobility, independence, falls, mortality, and hospitalization risk.25 Reduced gait speed is also one of the key indicators of functional impairment in older adults.

A 2015 systematic review sought to determine which type of exercise intervention (resistance, coordination, or multimodal training) would be most effective in preserving gait speed in healthy older adults (N = 2495; mean age = 74.2 years).25 While the 42 included studies were deemed to be fairly low quality, the review revealed (with large effect size [0.84]) that a number of exercise modalities might stave off loss of gait speed in older adults. Patients in the resistance training group had the greatest improvement in gait speed (0.11 m/s), followed by those in the coordination training group (0.09 m/s) and the multimodal training group (0.05 m/s).25

Finally, muscle mass and strength offer a measure of physical performance and functionality. A 2020 systematic review of 83 studies (N = 108,428) showed that low muscle mass and strength, reduced handgrip strength, and lower physical performance were predictive of reduced capacities in activities of daily living and instrumental activities of daily living.26 It is important to counsel adults to remain active throughout their lives and to include resistance training to maintain muscle mass and strength to preserve their motor function, mobility, independence, and QOL.

Use 1 of these scales to identify frailty. Frailty is a distinct clinical syndrome, in which an individual has low reserves and is highly vulnerable to internal and external stressors. It affects many community-dwelling older adults. Within the literature, there has been ongoing discussion regarding the definition of frailty27 (TABLE 128-31).

Continue to: The Fried Frailty Index...

The Fried Frailty Index defines frailty as a purely physical condition; patients need to exhibit 3 of 5 components (ie, weight loss, exhaustion, weakness, slowness, and low physical activity) to be deemed frail.31 The Edmonton Frail Scale is commonly used in geriatric assessments and counts impairments across several domains including physical activity, mood, cognition, and incontinence.30,32,33 Physicians need to complete a training course prior to its use. Finally, the definition of frailty used by Rockwood et al28, 29 was used to develop the Clinical Frailty Scale, which relies on broader criteria that include social and psychological elements in addition to physical elements.The Clinical Frailty Scale uses clinician judgment to evaluate patient-specific domains (eg, comorbidities, functionality, and cognition) and to generate a score ranging from 1 (very fit) to 9 (terminally ill).29 This scale is accessible and easy to implement. As a result, use of this scale has increased during the COVID-19 pandemic. All definitions include a pre-frail state, indicating the dynamic nature of frailty over time.

It is important to identify pre-frail and frail older adults using 1 of these screening tools. Interventions to reverse frailty that can be initiated in the primary care setting include identifying treatable medical conditions, assessing medication appropriateness, providing nutritional advice, and developing an exercise plan.34

Conduct a nutritional assessment; consider this diet. Studies show that nutritional status can predict physical function and frailty risk in older adults. A 2017 systematic review of 19 studies (N = 22,270) of frail adults ages ≥ 65 years found associations related to specific dietary constructs (ie, micronutrients, macronutrients, antioxidants, overall diet quality, and timing of consumption).35 Plant-based diets with higher levels of micronutrients, such as vitamins C and E and beta-carotene, or diets with more protein or macronutrients, regardless of source foods, all resulted in inverse associations with frailty syndrome.35

A 2017 study showed that physical exercise and maintaining good nutritional status may be effective for preventing frailty in community-dwelling pre-frail older individuals.36 A 2019 study showed that a combination of muscle strength training and protein supplementation was the most effective intervention to delay or reverse frailty and was easiest to implement in primary care.37 A 2020 meta-analysis of 31 studies (N = 4794) addressing frailty among primary care patients > 60 years showed that interventions using predominantly resistance-based exercise and nutrition supplementation improved frailty status over the control.38 Researchers also found that a comprehensive geriatric assessment or exercise—alone or in combination with nutrition education—reduced physical frailty.

Mentation

Screen and treat cognitive impairments. Cognitive function and autonomy in decision-making are important factors in healthy aging. Aspects of mental health (eg, depression and anxiety), sensory impairment (eg, visual and auditory impairment), and mentation issues (eg, delirium, dementia, and related conditions), as well as diet, physical exercise, and mobility, can all impede cognitive functionality. The long-term effects of depression, anxiety,39 sensory deficits,40 mobility,41 diet,42 and, ultimately, aging may impact Alzheimer disease (AD). The risk of an AD diagnosis increases with age.39

Continue to: A 2018 prospective cohort study...

A 2018 prospective cohort study using data from the National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center followed individuals (N = 12,053) who were cognitively asymptomatic at their initial visits to determine who developed clinical signs of AD.39 Survival analysis showed several psychosocial factors—anxiety, sleep disturbances, and depressive episodes of any type (occurring within the past 2 years, clinician verified, lifetime report)—were significantly associated with an eventual AD diagnosis and increased the risk of AD.39 More research is needed to verify the impact of early intervention for these conditions on neurodegenerative disease; however, screening and treating psychosocial factors such as anxiety and depression should be maintained.

Researchers evaluated the impact of a dual sensory impairment (DSI) on dementia risk using data from 2051 participants in the Ginkgo Evaluation of Memory Study.40 Hearing and visual impairments (defined as DSI when these conditions coexist) or visual impairment alone were significantly associated with increased risk of dementia in older adults. The researchers reported that DSI was significantly associated with a higher risk of all-cause dementia (hazard ratio [HR] = 1.86; 95% CI, 1.25-2.76) and AD (HR = 2.12; 95% CI, 1.34-3.36).40 Visual impairment alone was associated with an increased risk of all-cause dementia (HR = 1.32; 95% CI, 1.02-1.71).40 These results suggest that screening of DSI or visual impairment earlier in the patient’s lifespan may identify those at high risk of dementia in older adulthood.

The American Academy of Ophthalmology recommends patients with healthy eyes be screened once during their 20s and twice in their 30s; a full examination is recommended by age 40. For patients ages ≥ 65 years, it is recommended that eye examinations occur every 1 to 2 years.43

Diet and mobility play a big role in cognition. Diet43 and exercise41,42,44 are believed to have an impact on mentation, and recent studies show memory and global cognition could be malleable later in life. A 2015 meta-analysis of 490 treatment arms of 24 randomized controlled studies showed improvement in global cognition with consumption of a Mediterranean diet plus olive oil (effect size [ES] standardized mean difference [SMD] = 0.22; 95% CI, 0.16-0.27) and tai chi exercises (ES SMD = 0.18; 95% CI, 0.06-0.29).42 The analysis also found improved memory among participants who consumed the Mediterranean diet/olive oil combination (ES SMD = 0.22; 95% CI, 0.12-0.32) and soy isoflavone supplements (ES SMD = 0.11; 95% CI, 0.04-0.17). Although the ESs are small, they are significant and offer promising evidence that individual choices related to nutrition or exercise may influence cognition and memory.

A 2018 systematic review found that all domains of cognition showed improvement with 45 to 60 minutes of moderate-to-vigorous physical exercise.44 Attention, executive function, memory, and working memory showed significant increases, whereas global cognition improvements were not statistically significant.44 A 2016 meta-analysis of 26 studies (N = 26,355) found a positive association between an objective mobility measure (gait, lower-extremity function, and balance) and cognitive function (global, executive function, memory, and processing speed) in older adults.41 These results highlight that diet, mobility, and physical exercise impact cognitive functioning.

Continue to: Maintaining social connections

Maintaining social connections

Social isolation and loneliness—compounded by a pandemic. The US Department of Health and Human Services notes that “community connections” are among the key factors required for healthy aging.3 Similarly, the WHO definition of healthy aging considers whether individuals can build and sustain relationships with other people and find ways to engender their personal values through these connections.2

As people age, their social connections often decrease due to the death of friends and family, shifts in living arrangements, loss of mobility or eyesight (and thus self-transport), and the onset or increased acuity of illness or chronic conditions.45 This has been exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic, which has spurred shelter-in-place and stay-at-home orders along with recommendations for physical distancing (also known as social distancing), especially for older adults who are at higher risk.46 Smith et al47 calls this the COVID-19 Social Connectivity Paradox, in which older adults limit their interactions with others to protect their physical health and reduce their risk of contracting the virus, but as a result they may undermine their psychosocial health by placing themselves at risk of social isolation and loneliness.47

The double threat. Social isolation and loneliness have been shown to negatively impact physical health and well-being, resulting in an increased risk of early death48-50; higher likelihood of specific diagnoses, including dementia and cardiovascular conditions48,50; and more frequent use of health care services.50 These concepts, while related, represent different mechanisms for negative health outcomes. Social isolation is an objective condition when one has a lack of opportunities for interaction with other people; loneliness refers to the emotional disconnect one feels when separated from others. Few studies have compared outcomes between these concepts, but in those that have, social isolation appears to be more strongly associated with early death.48-50

A 2013 observational study using data from the English Longitudinal Study on Aging found that both social isolation and loneliness were associated with increased mortality among men and women ages ≥ 52 years (N = 6500).48 However, when studied independently, loneliness was not found to be a significant risk factor. In contrast, social isolation significantly impacted mortality risk, even after adjusting for demographic factors and baseline health status.48 These findings are supported by a 2018 cohort study of individuals (N = 479,054) with a history of an acute cardiovascular event that concluded social isolation was a predictor of mortality, whereas loneliness was not.50

A large 2015 meta-analysis (70 studies, N = 3,407,134) of mortality causes among community-dwelling older adults (average age, 66) confirmed that both objective measures of isolation, as well as subjective measures (such as feelings of loneliness or living alone), have a significant predictive effect in longer-term studies. Each measure shows an approximately 30% increase in the likelihood of death after an average of 7 years.49

Continue to: Health care remains a connection point

Health care remains a connection point. Even when life course events and conditions (eg, death of loved ones, loss of transportation or financial resources, or disengagement from community activities) reduce social connections, most older adults engage in some way with the health care system. A 2020 consensus report by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine suggests health care professionals capitalize on these connection points with adults ages ≥ 50 years by periodically screening for social isolation and loneliness, documenting social status updates in medical records, and piloting and evaluating interventions in the clinical setting.51

The report offered information about potential avenues for intervention by primary care professionals beyond screening, such as participating in research studies that investigate screening tools and multisystem interventions; social prescribing (linking patients to embedded social work services or community-based organizations); referring patients to support groups; initiating cognitive-based therapy or other behavioral health interventions; or recommending mindfulness practices.51 However, most of the cited intervention studies were not specific to primary care settings and contained poor-quality evidence related to efficacy.

Isolation creates a greater reliance on health services due to a lack of a social support system, while a feeling of emotional disconnection (loneliness) seems to be a barrier to accessing care. A 2017 cohort study linking data from the Health and Retirement Study and Medicare claims revealed that social isolation predicts higher annual health expenditures (> $1600 per beneficiary) driven by hospitalization and skilled nursing facility usage, along with greater mortality, whereas individuals who are lonely result in reduced costs (a reduction of $770 annually) due to lower usage of inpatient and outpatient services.52 Prioritizing interventions that identify and connect isolated older adults to social support, therefore, may increase survivability by ensuring they have access to resources and health care interventions when needed.

In addition, these findings underscore the importance of looking at quality—not just quantity—of older adults’ social connections. A number of validated screening tools exist for social isolation and loneliness (TABLE 253-59); however, concerns exist about assessing risk using a unidimensional tool for a complex concern,47 as well as identifying a problem without having evidence-based interventions to offer as solutions.47,51 Until future studies resolve these concerns, leveraging the physician-patient relationship to broach these difficult subjects may help normalize the issues and create safe spaces to identify individuals who are at risk.

QOL is key to healthy aging. As Kusumastuti et al4 state, “successful ageing lies in the eyes of the beholder.” A 2019 systematic review of 48 qualitative studies revealed that community-dwelling older adults ages ≥ 50 years in 11 countries (N > 4175) perceive well-being by considering QOL within 9 domains: health perception, autonomy, role and activity, relationships, emotional comfort, attitude and adaptation, spirituality, financial security, and home and neighborhood.60 Researchers found that as engagement in any one of these domains declines, older adults may shift their definition of health toward their remaining abilities.60 This offers an explanation as to why patients might rate their health status much higher than their physicians do: older adults tend to have a more holistic concept of health.

Continue to: Take a multidimensional approach to healthy aging

Take a multidimensional approach to healthy aging

Although we have separately examined each of the 4 components of managing healthy aging in a community-dwelling adult, applying a multidimensional approach is most effective. Increasing use of the Medicare AWV provides an opportunity to assess patient health status, determine care preferences, and improve follow-through on preventive screening. It is also important to encourage older adults to engage in regular physical activity—especially muscle-strengthening exercises—and to discuss nutrition and caloric intake to prevent frailty and functional decline.

Assessing and treating vision and hearing impairments and mental health issues, including anxiety and depression, may guard against losses in cognition. When speaking with older adult patients about their social connections, consider asking not only about frequency of contact and access to resources such as food and transportation, but also about whether they are finding ways to bring their own values into those relationships to bolster their QOL. This guidance also may be useful for primary care practices and health care networks when planning future quality-improvement initiatives.

Additional research is needed to support the evidence base for aligning older adult preferences in health care interventions, such as preventive screenings. Also, clinical decision-making requires more clarity about the efficacy of specific diet and exercise interventions for older adults; the impact of early intervention for depression, anxiety, and sleep disorders on neurodegenerative disease; whether loneliness predicts mortality; and how health care delivery systems can be effective at building social connectivity.

For now, it is essential to recognize that initiating health education, screening, and prevention throughout the patient’s lifespan can promote healthy aging outcomes. As family physicians, it is important to capitalize on longitudinal relationships with patients and begin educating younger patients using this multidimensional framework to promote living “a productive and meaningful life”at any age.3

Lynn M. Wilson, DO, 707 Hamilton Street, 8th floor, Department of Family Medicine, Lehigh Valley Health Network, Allentown, PA 18101; lynn_m.wilson@lvhn.org

Our approach to caring for the growing number of community-dwelling US adults ages ≥ 65 years has shifted. Although we continue to manage disease and disability, there is an increasing emphasis on the promotion of healthy aging by optimizing health care needs and quality of life (QOL).

The American Geriatric Society (AGS) uses the term “healthy aging” to reflect a dedication to improving the health, independence, and QOL of older people.1 The World Health Organization (WHO) defines healthy aging as “the process of developing and maintaining the functional ability that enables well-being in older age.”2 Functional ability encompasses capabilities that align with a person’s values, including meeting basic needs; learning, growing, and making independent decisions; being mobile; building and maintaining healthy relationships; and contributing to society.2 Similarly, the US Department of Health and Human Services has adopted a multidimensional approach to support people in creating “a productive and meaningful life” as they grow older.3

Numerous theoretical models have emerged from research on aging as a multidimensional construct, as evidenced by a 2016 citation analysis that identified 1755 articles written between 1902 and 2015 relating to “successful aging.”4 The analysis revealed 609 definitions operationalized by researchers’ measurement tools (mostly focused on physical function and other health metrics) and 1146 descriptions created by older adults, many emphasizing psychosocial strategies and cultural factors as key to successful aging.4

One approach that is likely to be useful for family physicians is the Age-Friendly Health System. This is an initiative of The John A. Hartford Foundation and the Institute for Healthcare Improvement that uses a multidisciplinary approach to create environments that foster inclusivity and address the needs of older people.5 Following this guidance, primary care providers use evidence-informed strategies that promote safety and address what matters most to older adults and their family caregivers.

The Age-Friendly Health System, as well as AGS and WHO, recognize that there are multiple aspects to well-being as one grows older. By using focused, evidence-based screening, assessments, and interventions, family physicians can best support aging patients in living their most fulfilling lives.

Here we present a review of evidence-based strategies that promote safety and address what matters most to older adults and their family caregivers using a 4-pronged framework, in the style of the Age-Friendly Health System model. However, the literature on healthy aging includes important messages about patient context and lifelong health behaviors, which we capture in an expanded set of thematic guidance. As such, we encourage family physicians to approach healthy aging as follows: (1) monitor health (screening and prevention), (2) promote mobility (physical function), (3) manage mentation (emotional health and cognitive function), and (4) encourage maintenance of social connections (social networks and QOL).

Monitoring health

Leverage Medicare annual wellness visits. A systematic approach is needed to prevent frailty and functional decline, and thus increase the QOL of older adults. To do this, it is important to focus on health promotion and disease prevention, while addressing existing ailments. One method is to leverage the Medicare annual wellness visit (AWV), which provides an opportunity to assess current health status as well as discuss behavior-change and risk-reduction strategies with patients.

Continue to: Although AWVs...

Although AWVs are an opportunity to improve patient outcomes, we are not taking full advantage of them.6 While AWVs have gained traction since their introduction in 2011, usage rates among ethnoracial minority groups has lagged behind.6 A 2018 cohort study examined reasons for disparate utilization rates among individuals ages ≥ 66 years (N = 14,687).7 Researchers found that differences in utilization between ethnoracial groups were explained by socioeconomic factors. Lower education and lower income, as well as rural living, were associated with lower rates of AWV completion.7 In addition, having a usual, nonemergent place to obtain medical care served as a powerful predictor of AWV utilization for all groups.7

Strategies to increase AWV completion rates among all eligible adults include increasing staff awareness of health literacy challenges and ensuring communication strategies are inclusive by providing printed materials in multiple languages, Braille, or larger typefaces; using accessible vocabulary that does not include medical jargon; and making medical interpreters accessible. In addition, training clinicians about unconscious bias and cultural humility can help foster empathy and awareness of differences in health beliefs and behaviors within diverse patient populations.

A 2019 scoping review of 11 studies (N > 60 million) focused on outcomes from Medicare AWVs for patients ages ≥ 65 years.8 This included uptake of preventive services, such as vaccinations or cancer screenings; advice, education, or referrals offered during the AWV; medication use; and hospitalization rates. Overall findings showed that older adults who received a Medicare AWV were more likely to receive referrals for preventive screenings and follow-through on these recommendations compared with those who did not undergo an AWV.8

Completion rates for vaccines, while remaining low overall, were higher among those who completed an AWV. Additionally, these studies showed improved completion of screenings for breast cancer, bone density, and colon cancer. Several studies in the scoping review supported the use of AWVs as an effective means by which to offer health education and advice related to health promotion and risk reduction, such as diet and lifestyle modifications.8 Little evidence exists on long-term outcomes related to AWV completion.8

Utilize shared decision-making to determine whether preventive screening makes sense for your patient. Although cancer remains the second leading cause of death among Americans ages ≥ 65 years,9 clear screening guidelines for this age group remain elusive.10 Physicians and patients often are reluctant to stop cancer screening despite lower life expectancy and fewer potential benefits of diagnosis in this population.9 Some recent studies reinforce the heterogeneity of the older adult population and further underscore the importance of individual-level decision-making.11-14 It is important to let older adult patients and their caregivers know about the potential risks of screening tests, especially the possibility that incidental findings may lead to unwarranted additional care or monitoring.9

Continue to: Avoid these screening conversation missteps

Avoid these screening conversation missteps. A 2017 qualitative study asked 40 community-dwelling older adults (mean age = 76 years) about their preferences for discussing screening cessation with their physicians.13 Three themes emerged.First, they were open to stopping their screenings, especially when suggested by a trusted physician. Second, health status and physical function made sense as decision points, but life expectancy did not. Finally, lengthy discussions with expanded details about risks and benefits were not appreciated, especially if coupled with comments on the limited benefits for those nearing the end of life. When discussing life expectancy, patients preferred phrasing that focused on how the screening was unnecessary because it would not help them live longer.13

Ensure that your message is understood—and culturally relevant. Recent studies on lower health literacy among older adults15,16 and ethnic and racial minorities17-21—as revealed in the 2003 National Assessment of Adult Literacy22—might offer clues to patient receptivity to discussions about preventive screening and other health decisions.

One study found a significant correlation between higher self-rated health literacy and higher engagement in health behaviors such as mammography screening, moderate physical activity, and tobacco avoidance.16 Perceptions of personal control over health status, as well as perceived social standing, also correlated with health literacy score levels.16 Another study concluded that lower health literacy combined with lower self-efficacy, cultural beliefs about health topics (eg, diet and exercise), and distrust in the health care system contributed to lower rates of preventive care utilization among ethnocultural minority older adults in Canada, the United Kingdom, the United States, and Australia.18