User login

PULMONARY PERSPECTIVES®: Why are we not advocating for ambulation?

Thoracic surgeons are procedurally focused

Thoracic surgery has seen significant changes over the past decade with an ever-increasing procedural focus. As a minimally invasive thoracic surgeon, I have been part of this transformation. Minimally invasive approaches can often replace thoracotomy incisions—considerably reducing morbidity, shortening recovery, and returning patients back to productive lives faster (Villamizar et al. J Thoracic Cardiovasr Surg. 2009;138:419).

Thoracic surgery evolved this way for the primary purpose of improving care for our patients. As a surgical community, we have spent endless hours toiling to create smaller and fewer incisions, design and modify instruments, improve visualization, find unique ways to seal tissue, shorten procedural time, and make operations more cost effective. While we have made significant strides in the operative arena, the perioperative care of these patients remains much the same. Perhaps, the classical surgical focus on technique has caused us to miss the big picture.

Do what makes sense

Applying basic physiologic principles and common sense, our team believed that early postoperative ambulation would improve outcomes and was an essential part of optimal postoperative recovery (Leithauser. J International Coll Surg. 1949;12[3]:368). Anticipated benefits of early postoperative ambulation include:

1. Decrease narcotic necessity - Upright positioning places less mechanical strain on the intercostal space, thereby relaxing the intercostal muscles that have been cut during surgery (minimally invasive or open). Less pain results in less narcotic use. Limitation of narcotics allows for the avoidance of related complications.

a. Narcotics decrease respiratory drive that is inherently detrimental after operating on the lungs, as it promotes pooling of secretions, increases atelectasis, and poses an aspiration risk.

b. Narcotics diminish wakefulness, thereby limiting ambulation, promoting suboptimal patient position, increasing pain, and thereby creating the need for more narcotics.

c. Narcotics often result in constipation, significantly affecting time to full recovery and optimal patient satisfaction.

2. Decrease pneumonia risk - Ambulation facilitates mobilization of secretions and improved pulmonary toilet. This prevents pooling of secretions and superimposed bacterial proliferation.

3. Decrease deep venous thrombosis (DVT) and, therefore, pulmonary embolism (PE) risk - In thoracic surgery, while there is minimal local trauma, mobility directly combats venous stasis and malignancy becomes the only remaining risk factor from Virchow’s triad (stasis, trauma, hypercoaguable state, such as malignancy). We have observed that early postoperative ambulation is so successful that we do not routinely use any chemical DVT prophylaxis in our patients, before or after surgery.

4. Decrease atrial arrhythmias - Ambulation allows for optimal distribution of fluids, therefore, limiting peripheral edema, subsequent redistribution, atrial stretch, and the concomitant risk of atrial arrhythmias.

5. Decrease in postoperative hypotension - There is a peripheral vasodilatory effect from general anesthesia that may cause relative hypotension postoperatively. Fluid administration to combat this is detrimental in a patient who has undergone lung resection. Early ambulation improves peripheral vasomotor tone, increases venous return, and improves blood pressure, reducing the need for exogenous fluid administration.

6. Overall improved sense of well being – Patients tend to feel better walking and have a greater sense of confidence that they are recovering.

Building a pathway

When we began our multidisciplinary thoracic oncology program, we were given a mandate from administration to create metrics by which we could track our progress. Publicly reported cardiac surgery metrics, such as delivery of aspirin and beta-blockers or tracking readmission rates for CHF existed, but none existed in thoracic surgery. This represented an opportunity to create goals and then demonstrate success. We arbitrarily decided that our goal was to walk every patient 100 meters (distance from our postanesthesia care unit to the doors of the ICU and back) within 1 hour of extubation.

Overcoming obstacles

Much as is chronicled in Lillehai’s paper (J Heart Valve Dis. 1995; 4(suppl II):S106), we were at the first stage in the Evolution of an Idea - people said “it won’t work.” Therefore, our initial challenges surrounding this initiative revolved around safety and feasibility. Our nurses felt unsafe walking patients so soon after surgery because it was not what they were used to doing. Education, a small focused unit and appropriate staffing were the keys to overcoming these initial challenges. Nurses saw the benefits immediately, and the commitment propagated to the point of competition to see who could ambulate their patient farther and faster.

Results that speak for themselves

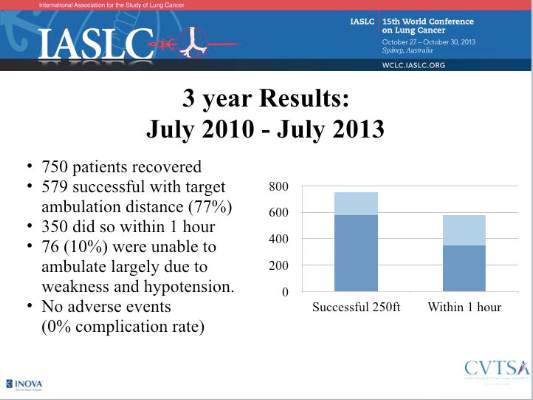

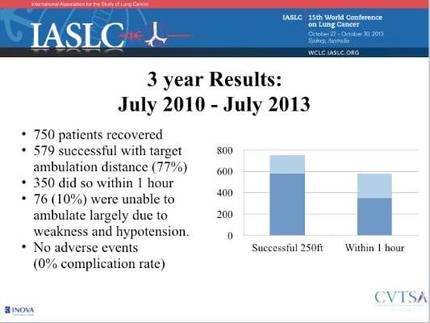

We retrospectively reviewed our 3-year experience in 2013 and presented that data at the World Conference on Lung Cancer in Sydney, Australia. Our goal was to demonstrate safety and feasibility, and we had done so in 750 patients. The response was a mixture of incredulousness and cautious optimism. We pressed on.

Validation and Retrospection

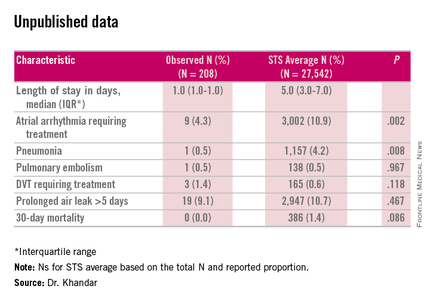

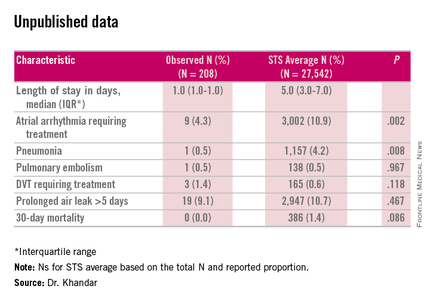

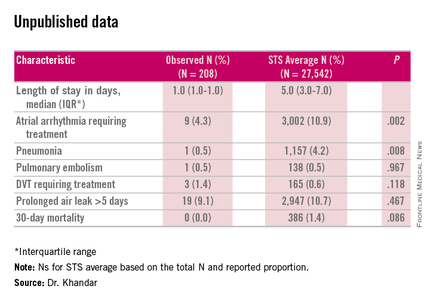

Our culture has changed. Postoperative ambulation has been effectively inculcated into our postanesthesia care unit and our inpatient unit. The expectations have been set, and they are well established. At this point, a prospective, randomized study seems unethical given the logical progression from physiologic principles and mechanistic understanding. In order to limit variability, we retrospectively analyzed 208 consecutive patients undergoing thoracoscopic lobectomy from 2010 to 2014 and compared them to the most recently available 3-year data from the Society of Thoracic Surgeons (STS) database. There were no significant differences in baseline characteristics, although it should be noted that the STS database included both open and thoracoscopic interventions, as the database is not yet further stratified. In spite of this, the differences in length of stay, atrial arrhythmias, and pneumonia rates still seem remarkable.

Conclusions

Early postoperative ambulation should be considered in any thoracic surgical setting. The benefits to the patient and the program are far reaching and result in better outcomes, higher patient satisfaction, and more nursing integration and foster a collaborative relationship between medical personnel and administration (Schatz. AORN Journal. 2015;102:482).

Dr. Khandhar is Medical Director and Chief, Thoracic Surgery, Inova Fairfax Hospital; Director, Thoracic Oncology Program, Inova Health System; and Clinical Assistant Professor, Virginia Commonwealth University and Inova Fairfax Residency Program, Falls Church, Virginia.

Thoracic surgeons are procedurally focused

Thoracic surgery has seen significant changes over the past decade with an ever-increasing procedural focus. As a minimally invasive thoracic surgeon, I have been part of this transformation. Minimally invasive approaches can often replace thoracotomy incisions—considerably reducing morbidity, shortening recovery, and returning patients back to productive lives faster (Villamizar et al. J Thoracic Cardiovasr Surg. 2009;138:419).

Thoracic surgery evolved this way for the primary purpose of improving care for our patients. As a surgical community, we have spent endless hours toiling to create smaller and fewer incisions, design and modify instruments, improve visualization, find unique ways to seal tissue, shorten procedural time, and make operations more cost effective. While we have made significant strides in the operative arena, the perioperative care of these patients remains much the same. Perhaps, the classical surgical focus on technique has caused us to miss the big picture.

Do what makes sense

Applying basic physiologic principles and common sense, our team believed that early postoperative ambulation would improve outcomes and was an essential part of optimal postoperative recovery (Leithauser. J International Coll Surg. 1949;12[3]:368). Anticipated benefits of early postoperative ambulation include:

1. Decrease narcotic necessity - Upright positioning places less mechanical strain on the intercostal space, thereby relaxing the intercostal muscles that have been cut during surgery (minimally invasive or open). Less pain results in less narcotic use. Limitation of narcotics allows for the avoidance of related complications.

a. Narcotics decrease respiratory drive that is inherently detrimental after operating on the lungs, as it promotes pooling of secretions, increases atelectasis, and poses an aspiration risk.

b. Narcotics diminish wakefulness, thereby limiting ambulation, promoting suboptimal patient position, increasing pain, and thereby creating the need for more narcotics.

c. Narcotics often result in constipation, significantly affecting time to full recovery and optimal patient satisfaction.

2. Decrease pneumonia risk - Ambulation facilitates mobilization of secretions and improved pulmonary toilet. This prevents pooling of secretions and superimposed bacterial proliferation.

3. Decrease deep venous thrombosis (DVT) and, therefore, pulmonary embolism (PE) risk - In thoracic surgery, while there is minimal local trauma, mobility directly combats venous stasis and malignancy becomes the only remaining risk factor from Virchow’s triad (stasis, trauma, hypercoaguable state, such as malignancy). We have observed that early postoperative ambulation is so successful that we do not routinely use any chemical DVT prophylaxis in our patients, before or after surgery.

4. Decrease atrial arrhythmias - Ambulation allows for optimal distribution of fluids, therefore, limiting peripheral edema, subsequent redistribution, atrial stretch, and the concomitant risk of atrial arrhythmias.

5. Decrease in postoperative hypotension - There is a peripheral vasodilatory effect from general anesthesia that may cause relative hypotension postoperatively. Fluid administration to combat this is detrimental in a patient who has undergone lung resection. Early ambulation improves peripheral vasomotor tone, increases venous return, and improves blood pressure, reducing the need for exogenous fluid administration.

6. Overall improved sense of well being – Patients tend to feel better walking and have a greater sense of confidence that they are recovering.

Building a pathway

When we began our multidisciplinary thoracic oncology program, we were given a mandate from administration to create metrics by which we could track our progress. Publicly reported cardiac surgery metrics, such as delivery of aspirin and beta-blockers or tracking readmission rates for CHF existed, but none existed in thoracic surgery. This represented an opportunity to create goals and then demonstrate success. We arbitrarily decided that our goal was to walk every patient 100 meters (distance from our postanesthesia care unit to the doors of the ICU and back) within 1 hour of extubation.

Overcoming obstacles

Much as is chronicled in Lillehai’s paper (J Heart Valve Dis. 1995; 4(suppl II):S106), we were at the first stage in the Evolution of an Idea - people said “it won’t work.” Therefore, our initial challenges surrounding this initiative revolved around safety and feasibility. Our nurses felt unsafe walking patients so soon after surgery because it was not what they were used to doing. Education, a small focused unit and appropriate staffing were the keys to overcoming these initial challenges. Nurses saw the benefits immediately, and the commitment propagated to the point of competition to see who could ambulate their patient farther and faster.

Results that speak for themselves

We retrospectively reviewed our 3-year experience in 2013 and presented that data at the World Conference on Lung Cancer in Sydney, Australia. Our goal was to demonstrate safety and feasibility, and we had done so in 750 patients. The response was a mixture of incredulousness and cautious optimism. We pressed on.

Validation and Retrospection

Our culture has changed. Postoperative ambulation has been effectively inculcated into our postanesthesia care unit and our inpatient unit. The expectations have been set, and they are well established. At this point, a prospective, randomized study seems unethical given the logical progression from physiologic principles and mechanistic understanding. In order to limit variability, we retrospectively analyzed 208 consecutive patients undergoing thoracoscopic lobectomy from 2010 to 2014 and compared them to the most recently available 3-year data from the Society of Thoracic Surgeons (STS) database. There were no significant differences in baseline characteristics, although it should be noted that the STS database included both open and thoracoscopic interventions, as the database is not yet further stratified. In spite of this, the differences in length of stay, atrial arrhythmias, and pneumonia rates still seem remarkable.

Conclusions

Early postoperative ambulation should be considered in any thoracic surgical setting. The benefits to the patient and the program are far reaching and result in better outcomes, higher patient satisfaction, and more nursing integration and foster a collaborative relationship between medical personnel and administration (Schatz. AORN Journal. 2015;102:482).

Dr. Khandhar is Medical Director and Chief, Thoracic Surgery, Inova Fairfax Hospital; Director, Thoracic Oncology Program, Inova Health System; and Clinical Assistant Professor, Virginia Commonwealth University and Inova Fairfax Residency Program, Falls Church, Virginia.

Thoracic surgeons are procedurally focused

Thoracic surgery has seen significant changes over the past decade with an ever-increasing procedural focus. As a minimally invasive thoracic surgeon, I have been part of this transformation. Minimally invasive approaches can often replace thoracotomy incisions—considerably reducing morbidity, shortening recovery, and returning patients back to productive lives faster (Villamizar et al. J Thoracic Cardiovasr Surg. 2009;138:419).

Thoracic surgery evolved this way for the primary purpose of improving care for our patients. As a surgical community, we have spent endless hours toiling to create smaller and fewer incisions, design and modify instruments, improve visualization, find unique ways to seal tissue, shorten procedural time, and make operations more cost effective. While we have made significant strides in the operative arena, the perioperative care of these patients remains much the same. Perhaps, the classical surgical focus on technique has caused us to miss the big picture.

Do what makes sense

Applying basic physiologic principles and common sense, our team believed that early postoperative ambulation would improve outcomes and was an essential part of optimal postoperative recovery (Leithauser. J International Coll Surg. 1949;12[3]:368). Anticipated benefits of early postoperative ambulation include:

1. Decrease narcotic necessity - Upright positioning places less mechanical strain on the intercostal space, thereby relaxing the intercostal muscles that have been cut during surgery (minimally invasive or open). Less pain results in less narcotic use. Limitation of narcotics allows for the avoidance of related complications.

a. Narcotics decrease respiratory drive that is inherently detrimental after operating on the lungs, as it promotes pooling of secretions, increases atelectasis, and poses an aspiration risk.

b. Narcotics diminish wakefulness, thereby limiting ambulation, promoting suboptimal patient position, increasing pain, and thereby creating the need for more narcotics.

c. Narcotics often result in constipation, significantly affecting time to full recovery and optimal patient satisfaction.

2. Decrease pneumonia risk - Ambulation facilitates mobilization of secretions and improved pulmonary toilet. This prevents pooling of secretions and superimposed bacterial proliferation.

3. Decrease deep venous thrombosis (DVT) and, therefore, pulmonary embolism (PE) risk - In thoracic surgery, while there is minimal local trauma, mobility directly combats venous stasis and malignancy becomes the only remaining risk factor from Virchow’s triad (stasis, trauma, hypercoaguable state, such as malignancy). We have observed that early postoperative ambulation is so successful that we do not routinely use any chemical DVT prophylaxis in our patients, before or after surgery.

4. Decrease atrial arrhythmias - Ambulation allows for optimal distribution of fluids, therefore, limiting peripheral edema, subsequent redistribution, atrial stretch, and the concomitant risk of atrial arrhythmias.

5. Decrease in postoperative hypotension - There is a peripheral vasodilatory effect from general anesthesia that may cause relative hypotension postoperatively. Fluid administration to combat this is detrimental in a patient who has undergone lung resection. Early ambulation improves peripheral vasomotor tone, increases venous return, and improves blood pressure, reducing the need for exogenous fluid administration.

6. Overall improved sense of well being – Patients tend to feel better walking and have a greater sense of confidence that they are recovering.

Building a pathway

When we began our multidisciplinary thoracic oncology program, we were given a mandate from administration to create metrics by which we could track our progress. Publicly reported cardiac surgery metrics, such as delivery of aspirin and beta-blockers or tracking readmission rates for CHF existed, but none existed in thoracic surgery. This represented an opportunity to create goals and then demonstrate success. We arbitrarily decided that our goal was to walk every patient 100 meters (distance from our postanesthesia care unit to the doors of the ICU and back) within 1 hour of extubation.

Overcoming obstacles

Much as is chronicled in Lillehai’s paper (J Heart Valve Dis. 1995; 4(suppl II):S106), we were at the first stage in the Evolution of an Idea - people said “it won’t work.” Therefore, our initial challenges surrounding this initiative revolved around safety and feasibility. Our nurses felt unsafe walking patients so soon after surgery because it was not what they were used to doing. Education, a small focused unit and appropriate staffing were the keys to overcoming these initial challenges. Nurses saw the benefits immediately, and the commitment propagated to the point of competition to see who could ambulate their patient farther and faster.

Results that speak for themselves

We retrospectively reviewed our 3-year experience in 2013 and presented that data at the World Conference on Lung Cancer in Sydney, Australia. Our goal was to demonstrate safety and feasibility, and we had done so in 750 patients. The response was a mixture of incredulousness and cautious optimism. We pressed on.

Validation and Retrospection

Our culture has changed. Postoperative ambulation has been effectively inculcated into our postanesthesia care unit and our inpatient unit. The expectations have been set, and they are well established. At this point, a prospective, randomized study seems unethical given the logical progression from physiologic principles and mechanistic understanding. In order to limit variability, we retrospectively analyzed 208 consecutive patients undergoing thoracoscopic lobectomy from 2010 to 2014 and compared them to the most recently available 3-year data from the Society of Thoracic Surgeons (STS) database. There were no significant differences in baseline characteristics, although it should be noted that the STS database included both open and thoracoscopic interventions, as the database is not yet further stratified. In spite of this, the differences in length of stay, atrial arrhythmias, and pneumonia rates still seem remarkable.

Conclusions

Early postoperative ambulation should be considered in any thoracic surgical setting. The benefits to the patient and the program are far reaching and result in better outcomes, higher patient satisfaction, and more nursing integration and foster a collaborative relationship between medical personnel and administration (Schatz. AORN Journal. 2015;102:482).

Dr. Khandhar is Medical Director and Chief, Thoracic Surgery, Inova Fairfax Hospital; Director, Thoracic Oncology Program, Inova Health System; and Clinical Assistant Professor, Virginia Commonwealth University and Inova Fairfax Residency Program, Falls Church, Virginia.