User login

Career Choices: Addiction psychiatry

Editor’s note: Career Choices features a psychiatry resident/fellow interviewing a psychiatrist about why he or she has chosen a specific career path. The goal is to inform trainees about the various psychiatric career options, and to give them a feel for the pros and cons of the various paths.

In this Career Choices, Saeed Ahmed, MD, talked with Cornel Stanciu, MD. Dr. Stanciu is an addiction psychiatrist at Dartmouth’s Geisel School of Medicine, where he is an Assistant Professor, and serves as the Director of Addiction Services at New Hampshire Hospital. He provides support to clinicians managing patients with addictive disorders in a multitude of settings, and also assists with policy making and delivery of addiction care at the state level. He is also the author of Deciphering the Addicted Brain, a guide to help families and the general public better understand addictive disorders.

Dr. Ahmed: What attracted you to pursue subspecialty training in addictive disorders?

Dr. Stanciu: In the early stages of my training, I frequently encountered individuals with medical and mental health disorders whose treatment was impacted by underlying substance use. I soon came to realize any attempts at (for example) managing hypertension in someone with cocaine use disorder, or managing schizophrenia in someone with ongoing cannabis use, were futile. Almost all of my patients receiving treatment for mental health disorders were dependent on tobacco or other substances, and most were interested in cessation. Through mentorship from addiction-trained residency faculty members, I was able to get a taste of the neurobiologic complexities of the disease, something that left me with a desire to develop a deeper understanding of the disease process. Witnessing strikingly positive outcomes with implementation of evidence-based treatment modalities further solidified my path to subspecialty training. Even during that early phase, because I expressed interest in managing these conditions, I was immediately put in a position to share and disseminate any newly acquired knowledge to other specialties as well as the public.

Dr. Ahmed: Could one manage addictive disorders with just general psychiatry training, and what are the differences between the different paths to certification that a resident could undertake?

Dr. Stanciu: Addictive disorders fall under the general umbrella of psychiatric care. Most individuals with these disorders exhibit some degree of mental illness. Medical school curriculum offers on average 2 hours of addiction-related didactics during 4 years. General psychiatry training programs vary significantly in the type of exposure to addiction—some residencies have an affiliated addiction fellowship, others have addiction-trained psychiatrists on staff, but most have none. Ultimately, there is great variability in the degree of comfort in working with individuals with addictive disorders post-residency. Being able to prescribe medications for the treatment of addictive disorders is very different from being familiar with the latest evidence-based recommendations and guidelines; the latter is

Addiction medicine is a fairly new route initially intended to allow non-psychiatric specialties access to addictive disorders training and certification. This is offered through the American Board of Preventive Medicine. There are currently 2 routes to sitting for the exam: through completion of a 1-year addiction medicine fellowship, or through the “practice pathway” still available until 2020. To be eligible for the latter, individuals must provide documentation of clinical experience post-residency, which is quantified as number of hours spent treating patients with addictions, plus any additional courses or training, and must be endorsed by a certified addictionologist.

Continue to: What was your fellowship experience link...

Dr. Ahmed: What was your fellowship experience like, and what should one consider when choosing a program?

Dr. Stanciu: I completed my fellowship training through Dartmouth’s Geisel School of Medicine, and the experience was tremendously valuable. In evaluating programs, one of the starting points is whether you have interest in a formal research track, because several programs include an optional year for that. Most programs tend to provide exposure to the Veterans Affairs system. The 1 year should provide you with broad exposure to all possible settings, all addictive disorders and patient populations, and all treatment modalities, in addition to rigorous didactic sessions. The ideal program should include rotations through methadone treatment centers, intensive outpatient programs, pain and interdisciplinary clinics, detoxification units, and centers for treatment of adolescent and young adults, as well as general medical settings and infectious disease clinics. There should also be close collaboration with psychologists who can provide training in evidence-based therapeutic modalities. During this year, it is vital to expand your knowledge of the ethical and legal regulations of treatment programs, state and federal requirements, insurance complexities, and requirements for privacy and protection of health information. The size of these programs can vary significantly, which may limit the one-on-one time devoted to your training, which is something I personally valued. My faculty was very supportive of academic endeavors, providing guidance, funding, and encouragement for attending and presenting at conferences, publishing papers, and other academic pursuits. Additionally, faculty should be current with emerging literature and willing to develop or implement new protocols and evaluate new pharmacologic therapies.

Dr. Ahmed: What are some of the career options and work settings for addiction psychiatrists?

Dr. Stanciu: Addiction psychiatrists work in numerous settings and various capacities. They can provide subspecialty care directly by seeing patients in outpatient clinics or inpatient addiction treatment centers for detoxification or rehabilitation, or they can work with dual-diagnosis populations in inpatient units. The expansion of telemedicine also holds promise for a role through virtual services. Indirectly, they can serve as a resource for expertise in the field through consultations in medical and psychiatric settings, or through policy making by working with the legislature and public health departments. Additionally, they can help create and integrate new knowledge into practice and educate future generations of physicians and the public.

Dr. Ahmed: What are some of the prevalent disorders and reasons for consultation that you encounter in your daily practice?

Continue to: Dr. Stanciu's response...

Dr. Stanciu: This can vary significantly depending on the setting, geographical region, and demographics of the population. My main non-administrative responsibilities are primarily consultative assisting clinicians at a 200-bed psychiatric hospital to address co-occurring addictive disorders. In short-term units, I am primarily asked to provide input on issues related to various toxidromes and withdrawals and the use of relapse prevention medications for alcohol use disorders as well as the use of buprenorphine or other forms of medication-assisted treatment. I work closely with licensed drug and alcohol counselors in implementing brief interventions as well as facilitating outpatient treatment referrals. Clinicians in longer term units may consult on issues related to pain management in individuals who have addictive disorders, the use of evidence-based pharmacologic agents to address cravings, or the use of relapse prevention medications for someone close to discharge. In terms of specific drugs of abuse, although opioids have recently received a tremendous amount of attention due to the visible costs through overdose deaths, the magnitude of individuals who are losing years of quality life through the use of alcohol and tobacco is significant, and hence this is a large portion of the conditions I encounter. I have also seen an abundance of marijuana use due to decreased perception of harm and increased access.

Dr. Ahmed: What are some of the challenges in working in this field?

Dr. Stanciu: Historically, funding for services has been an issue for clinicians working primarily with addictive disorders from the standpoint of reimbursement, patient access to evidence-based pharmacotherapy, and ability to collaborate with existing levels of care. In recent years, federal funding and policies have changed this, and after numerous studies have found increased cost savings, commercial insurances are providing coverage. A significant challenge also has been public stigma and dealing with a condition that is relapsing-remitting, poorly understood by other specialties and the general public, and sometimes labeled as a defect of character. Several efforts in education have lessened this; however, the impact still takes a toll on patients, who may feel ashamed of their disorder and sometimes are hesitant to take medications because they may believe that they are not “clean” if they depend on a medication for remission. Lastly, recent changes in marijuana policies make conversations about this drug quite difficult because patients often view it as harmless, and the laws governing legality and indications for therapeutic use are slightly ahead of the evidence.

Dr. Ahmed: In what direction do you believe the subspecialty is headed?

Dr. Stanciu: Currently, there are approximately 1,000 certified addiction psychiatrists for the 45 million Americans who have addictive disorders. Smoking and other forms of tobacco use pose significant threats to the 2020 Healthy People Tobacco Use objectives. There is a significant demand for addictionologists in both public and private sectors. As with mental health, demand exceeds supply, and efforts are underway to expand downstream education and increase access to specialists. Several federal laws have been put in place to remove barriers and expand access to care and have paved the way to a brighter future. One is the Affordable Care Act, which requires all insurances including Medicaid to cover the cost of treatment. Second is the Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act, which ensures that the duration and dollar amount of coverage for substance use disorders is comparable to that of medical and surgical care.

Continue to: Another exciting possibility...

Another exciting possibility comes from the world of pharmaceuticals. Some medications have modest efficacy for addressing addictive disorders; however, historically these have been poorly utilized. Enhanced understanding of the neurobiology combined with increased insurance reimbursement should prompt research and new drug development. Some promising agents are already in the pipeline. Research into molecular and gene therapy as a way to better individualize care is also underway.

Going forward, I think we will also encounter a different landscape of drugs. Synthetic agents are emerging and increasing in popularity. Alarmingly, public perception of harm is decreasing. When it comes to cannabis use, I see a rise in pathologic use and the ramifications of this will have a drastic impact, particularly on patients with mental health conditions. We will need to undertake better efforts in monitoring, staying updated, and providing public education campaigns.

Dr. Ahmed: What advice do you have for trainees contemplating subspecialty training in addiction psychiatry?

Dr. Stanciu: I cannot emphasize enough the importance of mentorship. The American Academy of Addiction Psychiatry has a robust system for connecting mentees with mentors at all stages in their careers. This can be extremely helpful, especially in situations where the residency program does not have addiction-trained faculty or rotations through treatment centers. Joining such an organization also grants you access to resources that can help further your enthusiasm. Those interested should also familiarize themselves with currently available pharmacotherapeutic treatments that have evidence supporting efficacy for various addictive disorders, and begin to incorporate these medications into general mental health practice, along with attempts at motivational interviewing. For example, begin discussing naltrexone with patients who have comorbid alcohol use disorders and are interested in reducing their drinking; and varenicline with patients who smoke and are interested in quitting. The outcomes should automatically elicit an interest in pursuing further training in the field!

Editor’s note: Career Choices features a psychiatry resident/fellow interviewing a psychiatrist about why he or she has chosen a specific career path. The goal is to inform trainees about the various psychiatric career options, and to give them a feel for the pros and cons of the various paths.

In this Career Choices, Saeed Ahmed, MD, talked with Cornel Stanciu, MD. Dr. Stanciu is an addiction psychiatrist at Dartmouth’s Geisel School of Medicine, where he is an Assistant Professor, and serves as the Director of Addiction Services at New Hampshire Hospital. He provides support to clinicians managing patients with addictive disorders in a multitude of settings, and also assists with policy making and delivery of addiction care at the state level. He is also the author of Deciphering the Addicted Brain, a guide to help families and the general public better understand addictive disorders.

Dr. Ahmed: What attracted you to pursue subspecialty training in addictive disorders?

Dr. Stanciu: In the early stages of my training, I frequently encountered individuals with medical and mental health disorders whose treatment was impacted by underlying substance use. I soon came to realize any attempts at (for example) managing hypertension in someone with cocaine use disorder, or managing schizophrenia in someone with ongoing cannabis use, were futile. Almost all of my patients receiving treatment for mental health disorders were dependent on tobacco or other substances, and most were interested in cessation. Through mentorship from addiction-trained residency faculty members, I was able to get a taste of the neurobiologic complexities of the disease, something that left me with a desire to develop a deeper understanding of the disease process. Witnessing strikingly positive outcomes with implementation of evidence-based treatment modalities further solidified my path to subspecialty training. Even during that early phase, because I expressed interest in managing these conditions, I was immediately put in a position to share and disseminate any newly acquired knowledge to other specialties as well as the public.

Dr. Ahmed: Could one manage addictive disorders with just general psychiatry training, and what are the differences between the different paths to certification that a resident could undertake?

Dr. Stanciu: Addictive disorders fall under the general umbrella of psychiatric care. Most individuals with these disorders exhibit some degree of mental illness. Medical school curriculum offers on average 2 hours of addiction-related didactics during 4 years. General psychiatry training programs vary significantly in the type of exposure to addiction—some residencies have an affiliated addiction fellowship, others have addiction-trained psychiatrists on staff, but most have none. Ultimately, there is great variability in the degree of comfort in working with individuals with addictive disorders post-residency. Being able to prescribe medications for the treatment of addictive disorders is very different from being familiar with the latest evidence-based recommendations and guidelines; the latter is

Addiction medicine is a fairly new route initially intended to allow non-psychiatric specialties access to addictive disorders training and certification. This is offered through the American Board of Preventive Medicine. There are currently 2 routes to sitting for the exam: through completion of a 1-year addiction medicine fellowship, or through the “practice pathway” still available until 2020. To be eligible for the latter, individuals must provide documentation of clinical experience post-residency, which is quantified as number of hours spent treating patients with addictions, plus any additional courses or training, and must be endorsed by a certified addictionologist.

Continue to: What was your fellowship experience link...

Dr. Ahmed: What was your fellowship experience like, and what should one consider when choosing a program?

Dr. Stanciu: I completed my fellowship training through Dartmouth’s Geisel School of Medicine, and the experience was tremendously valuable. In evaluating programs, one of the starting points is whether you have interest in a formal research track, because several programs include an optional year for that. Most programs tend to provide exposure to the Veterans Affairs system. The 1 year should provide you with broad exposure to all possible settings, all addictive disorders and patient populations, and all treatment modalities, in addition to rigorous didactic sessions. The ideal program should include rotations through methadone treatment centers, intensive outpatient programs, pain and interdisciplinary clinics, detoxification units, and centers for treatment of adolescent and young adults, as well as general medical settings and infectious disease clinics. There should also be close collaboration with psychologists who can provide training in evidence-based therapeutic modalities. During this year, it is vital to expand your knowledge of the ethical and legal regulations of treatment programs, state and federal requirements, insurance complexities, and requirements for privacy and protection of health information. The size of these programs can vary significantly, which may limit the one-on-one time devoted to your training, which is something I personally valued. My faculty was very supportive of academic endeavors, providing guidance, funding, and encouragement for attending and presenting at conferences, publishing papers, and other academic pursuits. Additionally, faculty should be current with emerging literature and willing to develop or implement new protocols and evaluate new pharmacologic therapies.

Dr. Ahmed: What are some of the career options and work settings for addiction psychiatrists?

Dr. Stanciu: Addiction psychiatrists work in numerous settings and various capacities. They can provide subspecialty care directly by seeing patients in outpatient clinics or inpatient addiction treatment centers for detoxification or rehabilitation, or they can work with dual-diagnosis populations in inpatient units. The expansion of telemedicine also holds promise for a role through virtual services. Indirectly, they can serve as a resource for expertise in the field through consultations in medical and psychiatric settings, or through policy making by working with the legislature and public health departments. Additionally, they can help create and integrate new knowledge into practice and educate future generations of physicians and the public.

Dr. Ahmed: What are some of the prevalent disorders and reasons for consultation that you encounter in your daily practice?

Continue to: Dr. Stanciu's response...

Dr. Stanciu: This can vary significantly depending on the setting, geographical region, and demographics of the population. My main non-administrative responsibilities are primarily consultative assisting clinicians at a 200-bed psychiatric hospital to address co-occurring addictive disorders. In short-term units, I am primarily asked to provide input on issues related to various toxidromes and withdrawals and the use of relapse prevention medications for alcohol use disorders as well as the use of buprenorphine or other forms of medication-assisted treatment. I work closely with licensed drug and alcohol counselors in implementing brief interventions as well as facilitating outpatient treatment referrals. Clinicians in longer term units may consult on issues related to pain management in individuals who have addictive disorders, the use of evidence-based pharmacologic agents to address cravings, or the use of relapse prevention medications for someone close to discharge. In terms of specific drugs of abuse, although opioids have recently received a tremendous amount of attention due to the visible costs through overdose deaths, the magnitude of individuals who are losing years of quality life through the use of alcohol and tobacco is significant, and hence this is a large portion of the conditions I encounter. I have also seen an abundance of marijuana use due to decreased perception of harm and increased access.

Dr. Ahmed: What are some of the challenges in working in this field?

Dr. Stanciu: Historically, funding for services has been an issue for clinicians working primarily with addictive disorders from the standpoint of reimbursement, patient access to evidence-based pharmacotherapy, and ability to collaborate with existing levels of care. In recent years, federal funding and policies have changed this, and after numerous studies have found increased cost savings, commercial insurances are providing coverage. A significant challenge also has been public stigma and dealing with a condition that is relapsing-remitting, poorly understood by other specialties and the general public, and sometimes labeled as a defect of character. Several efforts in education have lessened this; however, the impact still takes a toll on patients, who may feel ashamed of their disorder and sometimes are hesitant to take medications because they may believe that they are not “clean” if they depend on a medication for remission. Lastly, recent changes in marijuana policies make conversations about this drug quite difficult because patients often view it as harmless, and the laws governing legality and indications for therapeutic use are slightly ahead of the evidence.

Dr. Ahmed: In what direction do you believe the subspecialty is headed?

Dr. Stanciu: Currently, there are approximately 1,000 certified addiction psychiatrists for the 45 million Americans who have addictive disorders. Smoking and other forms of tobacco use pose significant threats to the 2020 Healthy People Tobacco Use objectives. There is a significant demand for addictionologists in both public and private sectors. As with mental health, demand exceeds supply, and efforts are underway to expand downstream education and increase access to specialists. Several federal laws have been put in place to remove barriers and expand access to care and have paved the way to a brighter future. One is the Affordable Care Act, which requires all insurances including Medicaid to cover the cost of treatment. Second is the Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act, which ensures that the duration and dollar amount of coverage for substance use disorders is comparable to that of medical and surgical care.

Continue to: Another exciting possibility...

Another exciting possibility comes from the world of pharmaceuticals. Some medications have modest efficacy for addressing addictive disorders; however, historically these have been poorly utilized. Enhanced understanding of the neurobiology combined with increased insurance reimbursement should prompt research and new drug development. Some promising agents are already in the pipeline. Research into molecular and gene therapy as a way to better individualize care is also underway.

Going forward, I think we will also encounter a different landscape of drugs. Synthetic agents are emerging and increasing in popularity. Alarmingly, public perception of harm is decreasing. When it comes to cannabis use, I see a rise in pathologic use and the ramifications of this will have a drastic impact, particularly on patients with mental health conditions. We will need to undertake better efforts in monitoring, staying updated, and providing public education campaigns.

Dr. Ahmed: What advice do you have for trainees contemplating subspecialty training in addiction psychiatry?

Dr. Stanciu: I cannot emphasize enough the importance of mentorship. The American Academy of Addiction Psychiatry has a robust system for connecting mentees with mentors at all stages in their careers. This can be extremely helpful, especially in situations where the residency program does not have addiction-trained faculty or rotations through treatment centers. Joining such an organization also grants you access to resources that can help further your enthusiasm. Those interested should also familiarize themselves with currently available pharmacotherapeutic treatments that have evidence supporting efficacy for various addictive disorders, and begin to incorporate these medications into general mental health practice, along with attempts at motivational interviewing. For example, begin discussing naltrexone with patients who have comorbid alcohol use disorders and are interested in reducing their drinking; and varenicline with patients who smoke and are interested in quitting. The outcomes should automatically elicit an interest in pursuing further training in the field!

Editor’s note: Career Choices features a psychiatry resident/fellow interviewing a psychiatrist about why he or she has chosen a specific career path. The goal is to inform trainees about the various psychiatric career options, and to give them a feel for the pros and cons of the various paths.

In this Career Choices, Saeed Ahmed, MD, talked with Cornel Stanciu, MD. Dr. Stanciu is an addiction psychiatrist at Dartmouth’s Geisel School of Medicine, where he is an Assistant Professor, and serves as the Director of Addiction Services at New Hampshire Hospital. He provides support to clinicians managing patients with addictive disorders in a multitude of settings, and also assists with policy making and delivery of addiction care at the state level. He is also the author of Deciphering the Addicted Brain, a guide to help families and the general public better understand addictive disorders.

Dr. Ahmed: What attracted you to pursue subspecialty training in addictive disorders?

Dr. Stanciu: In the early stages of my training, I frequently encountered individuals with medical and mental health disorders whose treatment was impacted by underlying substance use. I soon came to realize any attempts at (for example) managing hypertension in someone with cocaine use disorder, or managing schizophrenia in someone with ongoing cannabis use, were futile. Almost all of my patients receiving treatment for mental health disorders were dependent on tobacco or other substances, and most were interested in cessation. Through mentorship from addiction-trained residency faculty members, I was able to get a taste of the neurobiologic complexities of the disease, something that left me with a desire to develop a deeper understanding of the disease process. Witnessing strikingly positive outcomes with implementation of evidence-based treatment modalities further solidified my path to subspecialty training. Even during that early phase, because I expressed interest in managing these conditions, I was immediately put in a position to share and disseminate any newly acquired knowledge to other specialties as well as the public.

Dr. Ahmed: Could one manage addictive disorders with just general psychiatry training, and what are the differences between the different paths to certification that a resident could undertake?

Dr. Stanciu: Addictive disorders fall under the general umbrella of psychiatric care. Most individuals with these disorders exhibit some degree of mental illness. Medical school curriculum offers on average 2 hours of addiction-related didactics during 4 years. General psychiatry training programs vary significantly in the type of exposure to addiction—some residencies have an affiliated addiction fellowship, others have addiction-trained psychiatrists on staff, but most have none. Ultimately, there is great variability in the degree of comfort in working with individuals with addictive disorders post-residency. Being able to prescribe medications for the treatment of addictive disorders is very different from being familiar with the latest evidence-based recommendations and guidelines; the latter is

Addiction medicine is a fairly new route initially intended to allow non-psychiatric specialties access to addictive disorders training and certification. This is offered through the American Board of Preventive Medicine. There are currently 2 routes to sitting for the exam: through completion of a 1-year addiction medicine fellowship, or through the “practice pathway” still available until 2020. To be eligible for the latter, individuals must provide documentation of clinical experience post-residency, which is quantified as number of hours spent treating patients with addictions, plus any additional courses or training, and must be endorsed by a certified addictionologist.

Continue to: What was your fellowship experience link...

Dr. Ahmed: What was your fellowship experience like, and what should one consider when choosing a program?

Dr. Stanciu: I completed my fellowship training through Dartmouth’s Geisel School of Medicine, and the experience was tremendously valuable. In evaluating programs, one of the starting points is whether you have interest in a formal research track, because several programs include an optional year for that. Most programs tend to provide exposure to the Veterans Affairs system. The 1 year should provide you with broad exposure to all possible settings, all addictive disorders and patient populations, and all treatment modalities, in addition to rigorous didactic sessions. The ideal program should include rotations through methadone treatment centers, intensive outpatient programs, pain and interdisciplinary clinics, detoxification units, and centers for treatment of adolescent and young adults, as well as general medical settings and infectious disease clinics. There should also be close collaboration with psychologists who can provide training in evidence-based therapeutic modalities. During this year, it is vital to expand your knowledge of the ethical and legal regulations of treatment programs, state and federal requirements, insurance complexities, and requirements for privacy and protection of health information. The size of these programs can vary significantly, which may limit the one-on-one time devoted to your training, which is something I personally valued. My faculty was very supportive of academic endeavors, providing guidance, funding, and encouragement for attending and presenting at conferences, publishing papers, and other academic pursuits. Additionally, faculty should be current with emerging literature and willing to develop or implement new protocols and evaluate new pharmacologic therapies.

Dr. Ahmed: What are some of the career options and work settings for addiction psychiatrists?

Dr. Stanciu: Addiction psychiatrists work in numerous settings and various capacities. They can provide subspecialty care directly by seeing patients in outpatient clinics or inpatient addiction treatment centers for detoxification or rehabilitation, or they can work with dual-diagnosis populations in inpatient units. The expansion of telemedicine also holds promise for a role through virtual services. Indirectly, they can serve as a resource for expertise in the field through consultations in medical and psychiatric settings, or through policy making by working with the legislature and public health departments. Additionally, they can help create and integrate new knowledge into practice and educate future generations of physicians and the public.

Dr. Ahmed: What are some of the prevalent disorders and reasons for consultation that you encounter in your daily practice?

Continue to: Dr. Stanciu's response...

Dr. Stanciu: This can vary significantly depending on the setting, geographical region, and demographics of the population. My main non-administrative responsibilities are primarily consultative assisting clinicians at a 200-bed psychiatric hospital to address co-occurring addictive disorders. In short-term units, I am primarily asked to provide input on issues related to various toxidromes and withdrawals and the use of relapse prevention medications for alcohol use disorders as well as the use of buprenorphine or other forms of medication-assisted treatment. I work closely with licensed drug and alcohol counselors in implementing brief interventions as well as facilitating outpatient treatment referrals. Clinicians in longer term units may consult on issues related to pain management in individuals who have addictive disorders, the use of evidence-based pharmacologic agents to address cravings, or the use of relapse prevention medications for someone close to discharge. In terms of specific drugs of abuse, although opioids have recently received a tremendous amount of attention due to the visible costs through overdose deaths, the magnitude of individuals who are losing years of quality life through the use of alcohol and tobacco is significant, and hence this is a large portion of the conditions I encounter. I have also seen an abundance of marijuana use due to decreased perception of harm and increased access.

Dr. Ahmed: What are some of the challenges in working in this field?

Dr. Stanciu: Historically, funding for services has been an issue for clinicians working primarily with addictive disorders from the standpoint of reimbursement, patient access to evidence-based pharmacotherapy, and ability to collaborate with existing levels of care. In recent years, federal funding and policies have changed this, and after numerous studies have found increased cost savings, commercial insurances are providing coverage. A significant challenge also has been public stigma and dealing with a condition that is relapsing-remitting, poorly understood by other specialties and the general public, and sometimes labeled as a defect of character. Several efforts in education have lessened this; however, the impact still takes a toll on patients, who may feel ashamed of their disorder and sometimes are hesitant to take medications because they may believe that they are not “clean” if they depend on a medication for remission. Lastly, recent changes in marijuana policies make conversations about this drug quite difficult because patients often view it as harmless, and the laws governing legality and indications for therapeutic use are slightly ahead of the evidence.

Dr. Ahmed: In what direction do you believe the subspecialty is headed?

Dr. Stanciu: Currently, there are approximately 1,000 certified addiction psychiatrists for the 45 million Americans who have addictive disorders. Smoking and other forms of tobacco use pose significant threats to the 2020 Healthy People Tobacco Use objectives. There is a significant demand for addictionologists in both public and private sectors. As with mental health, demand exceeds supply, and efforts are underway to expand downstream education and increase access to specialists. Several federal laws have been put in place to remove barriers and expand access to care and have paved the way to a brighter future. One is the Affordable Care Act, which requires all insurances including Medicaid to cover the cost of treatment. Second is the Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act, which ensures that the duration and dollar amount of coverage for substance use disorders is comparable to that of medical and surgical care.

Continue to: Another exciting possibility...

Another exciting possibility comes from the world of pharmaceuticals. Some medications have modest efficacy for addressing addictive disorders; however, historically these have been poorly utilized. Enhanced understanding of the neurobiology combined with increased insurance reimbursement should prompt research and new drug development. Some promising agents are already in the pipeline. Research into molecular and gene therapy as a way to better individualize care is also underway.

Going forward, I think we will also encounter a different landscape of drugs. Synthetic agents are emerging and increasing in popularity. Alarmingly, public perception of harm is decreasing. When it comes to cannabis use, I see a rise in pathologic use and the ramifications of this will have a drastic impact, particularly on patients with mental health conditions. We will need to undertake better efforts in monitoring, staying updated, and providing public education campaigns.

Dr. Ahmed: What advice do you have for trainees contemplating subspecialty training in addiction psychiatry?

Dr. Stanciu: I cannot emphasize enough the importance of mentorship. The American Academy of Addiction Psychiatry has a robust system for connecting mentees with mentors at all stages in their careers. This can be extremely helpful, especially in situations where the residency program does not have addiction-trained faculty or rotations through treatment centers. Joining such an organization also grants you access to resources that can help further your enthusiasm. Those interested should also familiarize themselves with currently available pharmacotherapeutic treatments that have evidence supporting efficacy for various addictive disorders, and begin to incorporate these medications into general mental health practice, along with attempts at motivational interviewing. For example, begin discussing naltrexone with patients who have comorbid alcohol use disorders and are interested in reducing their drinking; and varenicline with patients who smoke and are interested in quitting. The outcomes should automatically elicit an interest in pursuing further training in the field!

Injectable extended-release naltrexone for opioid dependence: 3 studies

Death by drug overdose is the number one cause of death in Americans 50 years of age and younger.1 In 2016, there were 63,632 drug overdose deaths in the United States2 Opioids were involved in 42,249 of these deaths, which represents 66.4% of all drug overdose deaths.2 From 2015 to 2016, the age-adjusted rate of overdose deaths increased significantly by 21.5% from 16.3 per 100,000 to 19.8 per 100,000.2 This means that every day, more than 115 people in the United States die after overdosing on opioids. The misuse of and addiction to opioids—including prescription pain relievers, heroin, and synthetic opioids such as fentanyl—is a serious national crisis that affects public health as well as social and economic welfare.

The gold standard treatment is medication-assisted treatment (MAT)—the use of FDA-approved medications, in combination with counseling and behavioral therapies, to provide a “whole-patient” approach.3 When it comes to MAT options for opioid use disorder (OUD), there are 3 medications, each with its own caveats.

Methadone is an opioid mu-receptor full agonist that prevents withdrawal but does not block other narcotics. It requires daily dosing as a liquid formulation that is dispensed only in regulated clinics.

Buprenorphine is a mu-receptor high affinity partial agonist/antagonist that blocks the majority of other narcotics while reducing withdrawal risk. It requires daily dosing as either a dissolving tablet or cheek film. Recently it has also become available as a 6-month implant as well as a 1-month subcutaneous injection. Buprenorphine is also available as a combined medication with naloxone; naloxone is an opioid antagonist

Naltrexone is a mu-receptor antagonist that blocks the effects of most narcotics. It does not lead to dependence, and is administered daily as a pill or monthly as a deep IM injection of its extended-release formulation.

The first 2 medications are tightly regulated options that are not available in many areas of the United States. Naltrexone, when provided as a daily pill, has adherence issues. As with any illness, lack of adherence to treatment is problematic; in the case of patients with OUD, this includes a high risk of overdose and death.

The use of injectable extended-release naltrexone (XR-NTX) may be a way to address nonadherence and thus prevent relapse. One of the challenges limiting naltrexone’s applicability has been the length of time required for an “opioid washout” of the mu receptors prior to administering naltrexone, which is a mu blocker. The washout can take as long as 7 to 10 days. This interval is not feasible for patients receiving inpatient treatment, and patients receiving treatment as outpatients are vulnerable to relapse during this time. Recently, there have been several attempts to shorten this gap through various experimental protocols based on incremental doses of NTX to facilitate withdrawal while managing symptoms.

Continue to: When selecting appropriate candidates for NTX treatment...

When selecting appropriate candidates for NTX treatment, clinicians should consider individuals who are:

- not interested in or able to receive agonist maintenance treatment (ie, patients who do not have access to an appropriate clinic in their area, or who are restricted to agonist treatment by probation/parole)

- highly abstinence-oriented (eg, active in a 12-step program)

- in professions where agonists are controversial (eg, healthcare and airlines)

- detoxified and abstinent but at risk for relapse.

Individuals who have failed agonist treatment (eg, who experience cravings for opioids and use opioids while receiving it, or are nonadherent or diverting/misusing the medication), who have a less severe form of OUD (short history and low level of use), or who use sporadically are also optimal candidates for NTX. Aside from the relapse-vulnerable washout gap prior to induction, one of the concerns with antagonist treatments is treatment retention; anecdotal clinical reports suggest that individuals often discontinue antagonists in favor of agonists.

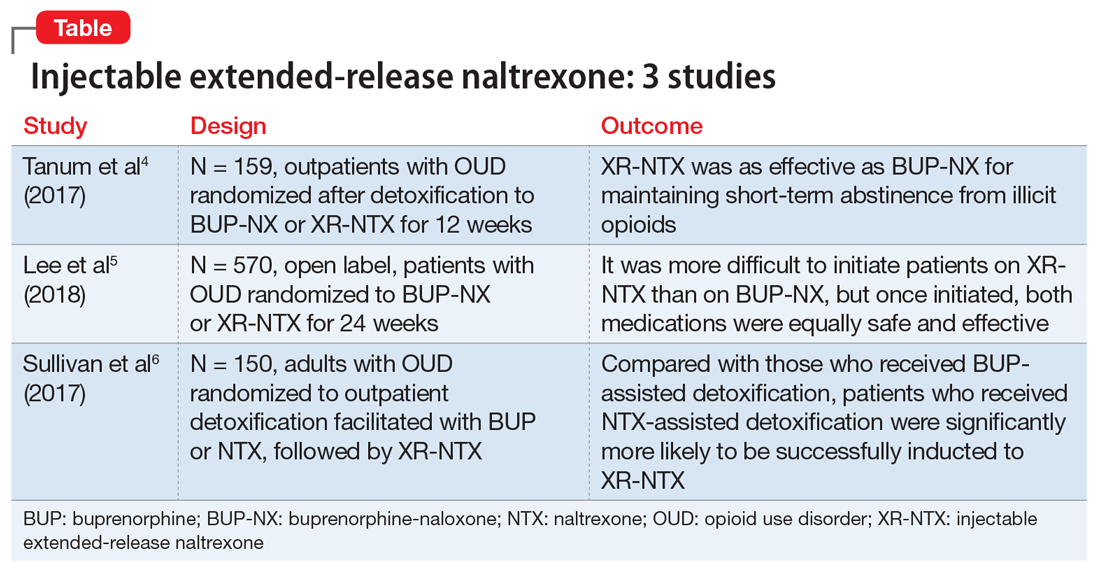

Several studies have investigated this by comparing XR-NTX with buprenorphine-naloxone (BUP-NX). Here we summarize 3 studies4-6 to describe which patients might be optimal candidates for XR-NTX, its success in comparison with BUP-NX, and challenges in induction of NTX, with a focus on emerging protocols (Table).

1. Tanum l, Solli KK, Latif ZH, et al. Effectiveness of injectable extended-release naltrexone vs daily buprenorphine-naloxone for opioid dependence: a randomized clinical noninferiority trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74(12):1197-1205.

This study aimed to determine whether XR-NTX was not inferior to BUP-NX in the treatment of OUD.

Study design

- N = 159, multicenter, randomized, 12-week outpatient study in Norway

- After detoxification, participants were randomized to receive BUP-NX, 4 to 24 mg/d, or XR-NTX, 380 mg/month.

Continue to: Outcomes

Outcomes

- Comparable treatment retention between groups

- Comparable opioid-negative urine drug screens (UDS)

- Significantly lower opioid use in the XR-NTX group.

Conclusion

- XR-NTX was as effective as BUP-NX in maintaining short-term abstinence from heroin and other illicit opioids, and thus should be considered as a treatment option for opioid-dependent individuals.

While this study showed similar efficacy for XR-NTX and BUP-NX, it is important to note that the randomization occurred after patients were detoxified. As a full opioid antagonist, XR-NTX can precipitate severe withdrawal, so patients need to be completely detoxified before starting XR-NTX, in contrast to BUP-NX, which patients can start even while still in mild withdrawal. Additional studies are needed in which individuals are randomized before detoxification, which would make it possible to measure the success of induction.

2. Lee JD, Nunes, EV, Novo P, et al. Comparative effectiveness of extended-release naltrexone versus buprenorphine-naloxone for opioid relapse prevention (X:BOT): a multicentre, open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2018;391(10118):309-318.

This study evaluated XR-NTX vs BUP-NX among adults with OUD who were actively using heroin at baseline and were admitted to community detoxification and treatment programs. Although the study began on inpatient units, it aimed to replicate usual community outpatient conditions across a 24-week outpatient treatment phase of this open-label, comparative effectiveness trial. Researchers assessed the effects on relapse-free survival, opioid use rates, and overdose events.

Study design

- N = 570, multicenter, randomized, 24-week study in the United States

- Detoxification methods: no opioids (clonidine or adjunctive medications), 3- to 5-day methadone taper, and 3- to 14-day BUP taper

- Protocol requirement: opioid-negative UDS before XR-NTX induction

- XR-NTX induction success ranged from 50% at a short-methadone-taper unit to 95% at an extended-opioid-free inpatient program. Nearly all induction failures quickly relapsed

- More participants inducted on BUP-NX group than XR-NTX group (94% vs 72%, respectively).

Continue to: Outcomes

Outcomes (once successfully inducted to treatment [n = 474])

- Comparable relapse events

- Comparable opioid-negative urine drug screens and opioid-abstinent days

- Opioid craving initially less with XR-NTX.

Conclusion

- It was more difficult to initiate patients on XR-NTX than BUP-NX, which negatively affected overall relapse rates. However, once initiated, both medications were equally safe and effective. Future work should focus on facilitating induction to XR-NTX and on improving treatment retention for both medications.

Regarding induction on NTX, patients must be detoxified and opioid-free for at least 7 days. If this medication is given to patients who are physically dependent and/or have opioids in their system, NTX will displace opioids off the receptor and precipitate a severe withdrawal (rather than a slow and gradual spontaneous withdrawal).

Several studies have examined the severity of opioid withdrawal (using Self Opioid Withdrawal Scale scoring) of patients undergoing detoxification with symptomatic management (eg, clonidine, loperamide, etc.), agonist-managed (eg, with a BUP taper), and without any assistance. As expected, the latter yielded the highest scoring and most uncomfortable experiences. Using scores from the first 2 groups, a threshold of symptom tolerability was established where patients remained somewhat comfortable during the process. During detoxification from heroin, administering any dose of NTX during the first 48 to 72 hours after the last use placed patients in a withdrawal of a magnitude above the limit of tolerability. At 48 to 72 hours, however, a very low NTX dose (3 to 6 mg) was found to be well tolerated, and withdrawal symptoms were easily managed supportively to accelerate the detoxification process. Several studies have attempted to devise protocols based on these findings in order to facilitate rapid induction onto NTX. The following study offers encouragement:

Continue to: 3. Sullivan M, Bisaga A, Pavlicova M...

3. Sullivan M, Bisaga A, Pavlicova M, et al. Long-acting injectable naltrexone induction: a randomized trial of outpatient opioid detoxification with naltrexone versus buprenorphine. Am J Psychiatry. 2017;174:459-467.

Study design

- N = 150 adults with OUD, randomized to outpatient opioid detoxification

- Patients were randomized to BUP- or NTX-facilitated detoxification, followed by XR-NTX

- BUP detoxification group underwent a 7-day BUP taper followed by a opioid-free week

- NTX group received a 1-day BUP dose followed by 6 days of ascending doses of oral NTX, along with clonidine and other adjunctive medications.

Outcomes

- NTX-assisted detoxification was significantly more successful for XR-NTX induction (56.1% vs 32.7%).

Conclusion

- Compared with the BUP-assisted detoxification group, NTX-assisted detoxification appears to make it significantly more likely for patients to be successfully inducted to XR-NTX.

The evidence discussed here holds promise in addressing some of the major issues surrounding MAT. For suitable candidates, XR-NTX seems to be as efficacious an option as agonist (BUP) MAT, and its induction limitations could be overcome by using NTX-facilitated detoxification protocols.

1. Rudd RA, Seth P, David F, et al. Increases in drug and opioid-involved overdose deaths - United States, 2010-2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65(50-51):1445-1452.

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Drug overdose death data. https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/data/statedeaths.html. Updated December 19, 2017. Accessed October 24, 2018.

3. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Medication-assisted treatment (MAT). https://www.samhsa.gov/medication-assisted-treatment. Updated February 7, 2018. Accessed October 23, 2018.

4. Tanum L, Solli KK, Latif ZH, et al. Effectiveness of injectable extended-release naltrexone vs daily buprenorphine-naloxone for opioid dependence: A randomized clinical noninferiority trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74(12):1197-1205.

5. Lee JD, Nunes, EV, Novo P, et al. Comparative effectiveness of extended-release naltrexone versus buprenorphine-naloxone for opioid relapse prevention (X:BOT): a multicentre, open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2018;391(10118):309-318.

6. Sullivan M, Bisaga A, Pavlicova M, et al. Long-acting injectable naltrexone induction: a randomized trial of outpatient opioid detoxification with naltrexone versus buprenorphine. Am J Psychiatry. 2017;174:459-467.

Death by drug overdose is the number one cause of death in Americans 50 years of age and younger.1 In 2016, there were 63,632 drug overdose deaths in the United States2 Opioids were involved in 42,249 of these deaths, which represents 66.4% of all drug overdose deaths.2 From 2015 to 2016, the age-adjusted rate of overdose deaths increased significantly by 21.5% from 16.3 per 100,000 to 19.8 per 100,000.2 This means that every day, more than 115 people in the United States die after overdosing on opioids. The misuse of and addiction to opioids—including prescription pain relievers, heroin, and synthetic opioids such as fentanyl—is a serious national crisis that affects public health as well as social and economic welfare.

The gold standard treatment is medication-assisted treatment (MAT)—the use of FDA-approved medications, in combination with counseling and behavioral therapies, to provide a “whole-patient” approach.3 When it comes to MAT options for opioid use disorder (OUD), there are 3 medications, each with its own caveats.

Methadone is an opioid mu-receptor full agonist that prevents withdrawal but does not block other narcotics. It requires daily dosing as a liquid formulation that is dispensed only in regulated clinics.

Buprenorphine is a mu-receptor high affinity partial agonist/antagonist that blocks the majority of other narcotics while reducing withdrawal risk. It requires daily dosing as either a dissolving tablet or cheek film. Recently it has also become available as a 6-month implant as well as a 1-month subcutaneous injection. Buprenorphine is also available as a combined medication with naloxone; naloxone is an opioid antagonist

Naltrexone is a mu-receptor antagonist that blocks the effects of most narcotics. It does not lead to dependence, and is administered daily as a pill or monthly as a deep IM injection of its extended-release formulation.

The first 2 medications are tightly regulated options that are not available in many areas of the United States. Naltrexone, when provided as a daily pill, has adherence issues. As with any illness, lack of adherence to treatment is problematic; in the case of patients with OUD, this includes a high risk of overdose and death.

The use of injectable extended-release naltrexone (XR-NTX) may be a way to address nonadherence and thus prevent relapse. One of the challenges limiting naltrexone’s applicability has been the length of time required for an “opioid washout” of the mu receptors prior to administering naltrexone, which is a mu blocker. The washout can take as long as 7 to 10 days. This interval is not feasible for patients receiving inpatient treatment, and patients receiving treatment as outpatients are vulnerable to relapse during this time. Recently, there have been several attempts to shorten this gap through various experimental protocols based on incremental doses of NTX to facilitate withdrawal while managing symptoms.

Continue to: When selecting appropriate candidates for NTX treatment...

When selecting appropriate candidates for NTX treatment, clinicians should consider individuals who are:

- not interested in or able to receive agonist maintenance treatment (ie, patients who do not have access to an appropriate clinic in their area, or who are restricted to agonist treatment by probation/parole)

- highly abstinence-oriented (eg, active in a 12-step program)

- in professions where agonists are controversial (eg, healthcare and airlines)

- detoxified and abstinent but at risk for relapse.

Individuals who have failed agonist treatment (eg, who experience cravings for opioids and use opioids while receiving it, or are nonadherent or diverting/misusing the medication), who have a less severe form of OUD (short history and low level of use), or who use sporadically are also optimal candidates for NTX. Aside from the relapse-vulnerable washout gap prior to induction, one of the concerns with antagonist treatments is treatment retention; anecdotal clinical reports suggest that individuals often discontinue antagonists in favor of agonists.

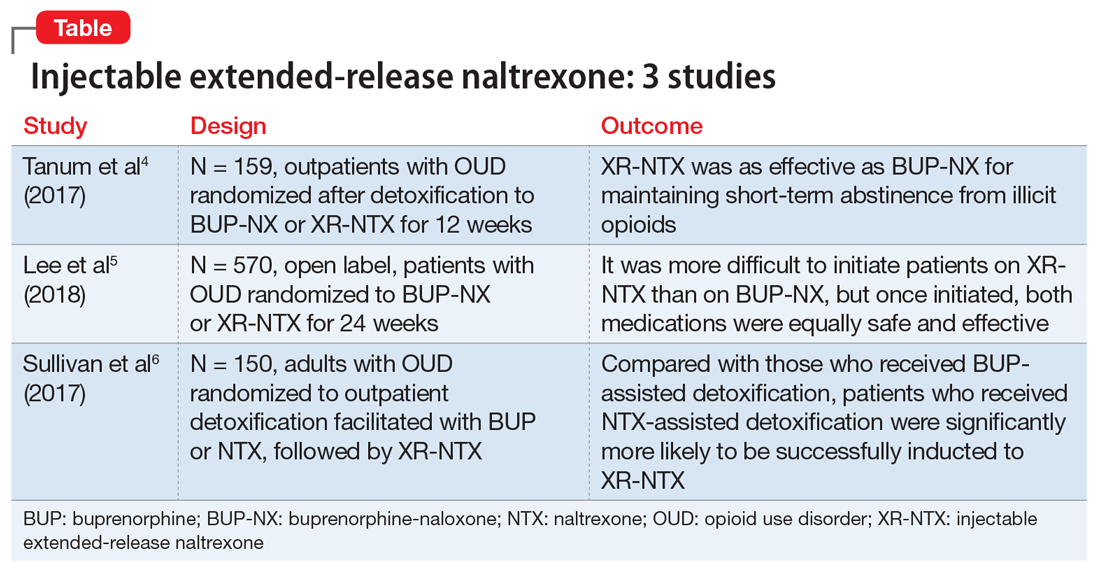

Several studies have investigated this by comparing XR-NTX with buprenorphine-naloxone (BUP-NX). Here we summarize 3 studies4-6 to describe which patients might be optimal candidates for XR-NTX, its success in comparison with BUP-NX, and challenges in induction of NTX, with a focus on emerging protocols (Table).

1. Tanum l, Solli KK, Latif ZH, et al. Effectiveness of injectable extended-release naltrexone vs daily buprenorphine-naloxone for opioid dependence: a randomized clinical noninferiority trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74(12):1197-1205.

This study aimed to determine whether XR-NTX was not inferior to BUP-NX in the treatment of OUD.

Study design

- N = 159, multicenter, randomized, 12-week outpatient study in Norway

- After detoxification, participants were randomized to receive BUP-NX, 4 to 24 mg/d, or XR-NTX, 380 mg/month.

Continue to: Outcomes

Outcomes

- Comparable treatment retention between groups

- Comparable opioid-negative urine drug screens (UDS)

- Significantly lower opioid use in the XR-NTX group.

Conclusion

- XR-NTX was as effective as BUP-NX in maintaining short-term abstinence from heroin and other illicit opioids, and thus should be considered as a treatment option for opioid-dependent individuals.

While this study showed similar efficacy for XR-NTX and BUP-NX, it is important to note that the randomization occurred after patients were detoxified. As a full opioid antagonist, XR-NTX can precipitate severe withdrawal, so patients need to be completely detoxified before starting XR-NTX, in contrast to BUP-NX, which patients can start even while still in mild withdrawal. Additional studies are needed in which individuals are randomized before detoxification, which would make it possible to measure the success of induction.

2. Lee JD, Nunes, EV, Novo P, et al. Comparative effectiveness of extended-release naltrexone versus buprenorphine-naloxone for opioid relapse prevention (X:BOT): a multicentre, open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2018;391(10118):309-318.

This study evaluated XR-NTX vs BUP-NX among adults with OUD who were actively using heroin at baseline and were admitted to community detoxification and treatment programs. Although the study began on inpatient units, it aimed to replicate usual community outpatient conditions across a 24-week outpatient treatment phase of this open-label, comparative effectiveness trial. Researchers assessed the effects on relapse-free survival, opioid use rates, and overdose events.

Study design

- N = 570, multicenter, randomized, 24-week study in the United States

- Detoxification methods: no opioids (clonidine or adjunctive medications), 3- to 5-day methadone taper, and 3- to 14-day BUP taper

- Protocol requirement: opioid-negative UDS before XR-NTX induction

- XR-NTX induction success ranged from 50% at a short-methadone-taper unit to 95% at an extended-opioid-free inpatient program. Nearly all induction failures quickly relapsed

- More participants inducted on BUP-NX group than XR-NTX group (94% vs 72%, respectively).

Continue to: Outcomes

Outcomes (once successfully inducted to treatment [n = 474])

- Comparable relapse events

- Comparable opioid-negative urine drug screens and opioid-abstinent days

- Opioid craving initially less with XR-NTX.

Conclusion

- It was more difficult to initiate patients on XR-NTX than BUP-NX, which negatively affected overall relapse rates. However, once initiated, both medications were equally safe and effective. Future work should focus on facilitating induction to XR-NTX and on improving treatment retention for both medications.

Regarding induction on NTX, patients must be detoxified and opioid-free for at least 7 days. If this medication is given to patients who are physically dependent and/or have opioids in their system, NTX will displace opioids off the receptor and precipitate a severe withdrawal (rather than a slow and gradual spontaneous withdrawal).

Several studies have examined the severity of opioid withdrawal (using Self Opioid Withdrawal Scale scoring) of patients undergoing detoxification with symptomatic management (eg, clonidine, loperamide, etc.), agonist-managed (eg, with a BUP taper), and without any assistance. As expected, the latter yielded the highest scoring and most uncomfortable experiences. Using scores from the first 2 groups, a threshold of symptom tolerability was established where patients remained somewhat comfortable during the process. During detoxification from heroin, administering any dose of NTX during the first 48 to 72 hours after the last use placed patients in a withdrawal of a magnitude above the limit of tolerability. At 48 to 72 hours, however, a very low NTX dose (3 to 6 mg) was found to be well tolerated, and withdrawal symptoms were easily managed supportively to accelerate the detoxification process. Several studies have attempted to devise protocols based on these findings in order to facilitate rapid induction onto NTX. The following study offers encouragement:

Continue to: 3. Sullivan M, Bisaga A, Pavlicova M...

3. Sullivan M, Bisaga A, Pavlicova M, et al. Long-acting injectable naltrexone induction: a randomized trial of outpatient opioid detoxification with naltrexone versus buprenorphine. Am J Psychiatry. 2017;174:459-467.

Study design

- N = 150 adults with OUD, randomized to outpatient opioid detoxification

- Patients were randomized to BUP- or NTX-facilitated detoxification, followed by XR-NTX

- BUP detoxification group underwent a 7-day BUP taper followed by a opioid-free week

- NTX group received a 1-day BUP dose followed by 6 days of ascending doses of oral NTX, along with clonidine and other adjunctive medications.

Outcomes

- NTX-assisted detoxification was significantly more successful for XR-NTX induction (56.1% vs 32.7%).

Conclusion

- Compared with the BUP-assisted detoxification group, NTX-assisted detoxification appears to make it significantly more likely for patients to be successfully inducted to XR-NTX.

The evidence discussed here holds promise in addressing some of the major issues surrounding MAT. For suitable candidates, XR-NTX seems to be as efficacious an option as agonist (BUP) MAT, and its induction limitations could be overcome by using NTX-facilitated detoxification protocols.

Death by drug overdose is the number one cause of death in Americans 50 years of age and younger.1 In 2016, there were 63,632 drug overdose deaths in the United States2 Opioids were involved in 42,249 of these deaths, which represents 66.4% of all drug overdose deaths.2 From 2015 to 2016, the age-adjusted rate of overdose deaths increased significantly by 21.5% from 16.3 per 100,000 to 19.8 per 100,000.2 This means that every day, more than 115 people in the United States die after overdosing on opioids. The misuse of and addiction to opioids—including prescription pain relievers, heroin, and synthetic opioids such as fentanyl—is a serious national crisis that affects public health as well as social and economic welfare.

The gold standard treatment is medication-assisted treatment (MAT)—the use of FDA-approved medications, in combination with counseling and behavioral therapies, to provide a “whole-patient” approach.3 When it comes to MAT options for opioid use disorder (OUD), there are 3 medications, each with its own caveats.

Methadone is an opioid mu-receptor full agonist that prevents withdrawal but does not block other narcotics. It requires daily dosing as a liquid formulation that is dispensed only in regulated clinics.

Buprenorphine is a mu-receptor high affinity partial agonist/antagonist that blocks the majority of other narcotics while reducing withdrawal risk. It requires daily dosing as either a dissolving tablet or cheek film. Recently it has also become available as a 6-month implant as well as a 1-month subcutaneous injection. Buprenorphine is also available as a combined medication with naloxone; naloxone is an opioid antagonist

Naltrexone is a mu-receptor antagonist that blocks the effects of most narcotics. It does not lead to dependence, and is administered daily as a pill or monthly as a deep IM injection of its extended-release formulation.

The first 2 medications are tightly regulated options that are not available in many areas of the United States. Naltrexone, when provided as a daily pill, has adherence issues. As with any illness, lack of adherence to treatment is problematic; in the case of patients with OUD, this includes a high risk of overdose and death.

The use of injectable extended-release naltrexone (XR-NTX) may be a way to address nonadherence and thus prevent relapse. One of the challenges limiting naltrexone’s applicability has been the length of time required for an “opioid washout” of the mu receptors prior to administering naltrexone, which is a mu blocker. The washout can take as long as 7 to 10 days. This interval is not feasible for patients receiving inpatient treatment, and patients receiving treatment as outpatients are vulnerable to relapse during this time. Recently, there have been several attempts to shorten this gap through various experimental protocols based on incremental doses of NTX to facilitate withdrawal while managing symptoms.

Continue to: When selecting appropriate candidates for NTX treatment...

When selecting appropriate candidates for NTX treatment, clinicians should consider individuals who are:

- not interested in or able to receive agonist maintenance treatment (ie, patients who do not have access to an appropriate clinic in their area, or who are restricted to agonist treatment by probation/parole)

- highly abstinence-oriented (eg, active in a 12-step program)

- in professions where agonists are controversial (eg, healthcare and airlines)

- detoxified and abstinent but at risk for relapse.

Individuals who have failed agonist treatment (eg, who experience cravings for opioids and use opioids while receiving it, or are nonadherent or diverting/misusing the medication), who have a less severe form of OUD (short history and low level of use), or who use sporadically are also optimal candidates for NTX. Aside from the relapse-vulnerable washout gap prior to induction, one of the concerns with antagonist treatments is treatment retention; anecdotal clinical reports suggest that individuals often discontinue antagonists in favor of agonists.

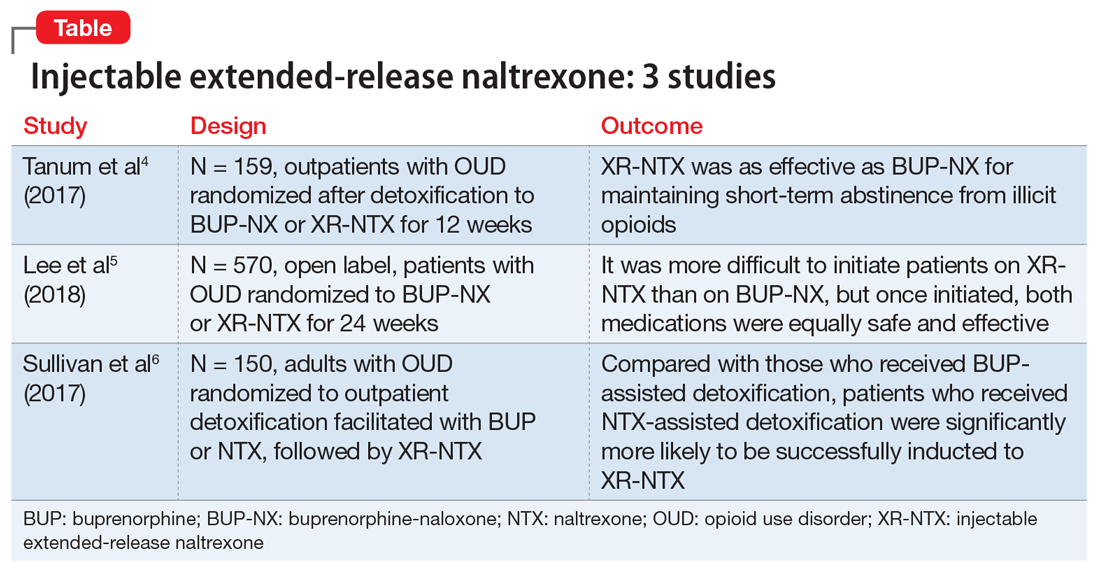

Several studies have investigated this by comparing XR-NTX with buprenorphine-naloxone (BUP-NX). Here we summarize 3 studies4-6 to describe which patients might be optimal candidates for XR-NTX, its success in comparison with BUP-NX, and challenges in induction of NTX, with a focus on emerging protocols (Table).

1. Tanum l, Solli KK, Latif ZH, et al. Effectiveness of injectable extended-release naltrexone vs daily buprenorphine-naloxone for opioid dependence: a randomized clinical noninferiority trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74(12):1197-1205.

This study aimed to determine whether XR-NTX was not inferior to BUP-NX in the treatment of OUD.

Study design

- N = 159, multicenter, randomized, 12-week outpatient study in Norway

- After detoxification, participants were randomized to receive BUP-NX, 4 to 24 mg/d, or XR-NTX, 380 mg/month.

Continue to: Outcomes

Outcomes

- Comparable treatment retention between groups

- Comparable opioid-negative urine drug screens (UDS)

- Significantly lower opioid use in the XR-NTX group.

Conclusion

- XR-NTX was as effective as BUP-NX in maintaining short-term abstinence from heroin and other illicit opioids, and thus should be considered as a treatment option for opioid-dependent individuals.

While this study showed similar efficacy for XR-NTX and BUP-NX, it is important to note that the randomization occurred after patients were detoxified. As a full opioid antagonist, XR-NTX can precipitate severe withdrawal, so patients need to be completely detoxified before starting XR-NTX, in contrast to BUP-NX, which patients can start even while still in mild withdrawal. Additional studies are needed in which individuals are randomized before detoxification, which would make it possible to measure the success of induction.

2. Lee JD, Nunes, EV, Novo P, et al. Comparative effectiveness of extended-release naltrexone versus buprenorphine-naloxone for opioid relapse prevention (X:BOT): a multicentre, open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2018;391(10118):309-318.

This study evaluated XR-NTX vs BUP-NX among adults with OUD who were actively using heroin at baseline and were admitted to community detoxification and treatment programs. Although the study began on inpatient units, it aimed to replicate usual community outpatient conditions across a 24-week outpatient treatment phase of this open-label, comparative effectiveness trial. Researchers assessed the effects on relapse-free survival, opioid use rates, and overdose events.

Study design

- N = 570, multicenter, randomized, 24-week study in the United States

- Detoxification methods: no opioids (clonidine or adjunctive medications), 3- to 5-day methadone taper, and 3- to 14-day BUP taper

- Protocol requirement: opioid-negative UDS before XR-NTX induction

- XR-NTX induction success ranged from 50% at a short-methadone-taper unit to 95% at an extended-opioid-free inpatient program. Nearly all induction failures quickly relapsed

- More participants inducted on BUP-NX group than XR-NTX group (94% vs 72%, respectively).

Continue to: Outcomes

Outcomes (once successfully inducted to treatment [n = 474])

- Comparable relapse events

- Comparable opioid-negative urine drug screens and opioid-abstinent days

- Opioid craving initially less with XR-NTX.

Conclusion

- It was more difficult to initiate patients on XR-NTX than BUP-NX, which negatively affected overall relapse rates. However, once initiated, both medications were equally safe and effective. Future work should focus on facilitating induction to XR-NTX and on improving treatment retention for both medications.

Regarding induction on NTX, patients must be detoxified and opioid-free for at least 7 days. If this medication is given to patients who are physically dependent and/or have opioids in their system, NTX will displace opioids off the receptor and precipitate a severe withdrawal (rather than a slow and gradual spontaneous withdrawal).

Several studies have examined the severity of opioid withdrawal (using Self Opioid Withdrawal Scale scoring) of patients undergoing detoxification with symptomatic management (eg, clonidine, loperamide, etc.), agonist-managed (eg, with a BUP taper), and without any assistance. As expected, the latter yielded the highest scoring and most uncomfortable experiences. Using scores from the first 2 groups, a threshold of symptom tolerability was established where patients remained somewhat comfortable during the process. During detoxification from heroin, administering any dose of NTX during the first 48 to 72 hours after the last use placed patients in a withdrawal of a magnitude above the limit of tolerability. At 48 to 72 hours, however, a very low NTX dose (3 to 6 mg) was found to be well tolerated, and withdrawal symptoms were easily managed supportively to accelerate the detoxification process. Several studies have attempted to devise protocols based on these findings in order to facilitate rapid induction onto NTX. The following study offers encouragement:

Continue to: 3. Sullivan M, Bisaga A, Pavlicova M...

3. Sullivan M, Bisaga A, Pavlicova M, et al. Long-acting injectable naltrexone induction: a randomized trial of outpatient opioid detoxification with naltrexone versus buprenorphine. Am J Psychiatry. 2017;174:459-467.

Study design

- N = 150 adults with OUD, randomized to outpatient opioid detoxification

- Patients were randomized to BUP- or NTX-facilitated detoxification, followed by XR-NTX

- BUP detoxification group underwent a 7-day BUP taper followed by a opioid-free week

- NTX group received a 1-day BUP dose followed by 6 days of ascending doses of oral NTX, along with clonidine and other adjunctive medications.

Outcomes

- NTX-assisted detoxification was significantly more successful for XR-NTX induction (56.1% vs 32.7%).

Conclusion

- Compared with the BUP-assisted detoxification group, NTX-assisted detoxification appears to make it significantly more likely for patients to be successfully inducted to XR-NTX.

The evidence discussed here holds promise in addressing some of the major issues surrounding MAT. For suitable candidates, XR-NTX seems to be as efficacious an option as agonist (BUP) MAT, and its induction limitations could be overcome by using NTX-facilitated detoxification protocols.

1. Rudd RA, Seth P, David F, et al. Increases in drug and opioid-involved overdose deaths - United States, 2010-2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65(50-51):1445-1452.

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Drug overdose death data. https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/data/statedeaths.html. Updated December 19, 2017. Accessed October 24, 2018.

3. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Medication-assisted treatment (MAT). https://www.samhsa.gov/medication-assisted-treatment. Updated February 7, 2018. Accessed October 23, 2018.

4. Tanum L, Solli KK, Latif ZH, et al. Effectiveness of injectable extended-release naltrexone vs daily buprenorphine-naloxone for opioid dependence: A randomized clinical noninferiority trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74(12):1197-1205.

5. Lee JD, Nunes, EV, Novo P, et al. Comparative effectiveness of extended-release naltrexone versus buprenorphine-naloxone for opioid relapse prevention (X:BOT): a multicentre, open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2018;391(10118):309-318.

6. Sullivan M, Bisaga A, Pavlicova M, et al. Long-acting injectable naltrexone induction: a randomized trial of outpatient opioid detoxification with naltrexone versus buprenorphine. Am J Psychiatry. 2017;174:459-467.

1. Rudd RA, Seth P, David F, et al. Increases in drug and opioid-involved overdose deaths - United States, 2010-2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65(50-51):1445-1452.

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Drug overdose death data. https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/data/statedeaths.html. Updated December 19, 2017. Accessed October 24, 2018.

3. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Medication-assisted treatment (MAT). https://www.samhsa.gov/medication-assisted-treatment. Updated February 7, 2018. Accessed October 23, 2018.

4. Tanum L, Solli KK, Latif ZH, et al. Effectiveness of injectable extended-release naltrexone vs daily buprenorphine-naloxone for opioid dependence: A randomized clinical noninferiority trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74(12):1197-1205.

5. Lee JD, Nunes, EV, Novo P, et al. Comparative effectiveness of extended-release naltrexone versus buprenorphine-naloxone for opioid relapse prevention (X:BOT): a multicentre, open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2018;391(10118):309-318.

6. Sullivan M, Bisaga A, Pavlicova M, et al. Long-acting injectable naltrexone induction: a randomized trial of outpatient opioid detoxification with naltrexone versus buprenorphine. Am J Psychiatry. 2017;174:459-467.

Career Choices: Directorship/leadership

Editor’s note: Career Choices features a psychiatry resident/fellow interviewing a psychiatrist about why he or she has chosen a specific career path. The goal is to inform trainees about the various psychiatric career options, and to give them a feel for the pros and cons of the various paths.

In this Career Choices, Cornel Stanciu, MD, talked with Thomas Penders, MS, MD. For most of his career, Dr. Penders has practiced in directorship roles. He currently serves as the leader of an addiction consultation service at the Walter B. Jones Center in Greenville, North Carolina, as well as working at the state level with federally qualified health centers to develop collaborative care models.

Dr. Stanciu: What led you to decide to pursue a director role?

Dr. Penders: Early in my career, I was offered opportunities to provide leadership for an organization in its efforts to assure quality and availability of appropriate medical and psychiatric care.

Dr. Stanciu: How has the director role evolved over the years?

Dr. Penders: Thirty years ago, when I got started, hospital administrations depended heavily on medical directors to provide advice on new service initiates. Medical directors were frequently provided with support by health care organizations when recommendations were made based on patient and community need as perceived by medical staff providers. There has been a dramatic shift in the relationship and role of medical directorship, particularly over the past decade. Budgetary constraints have influenced planning and operational decisions to the extent that these decisions are much more likely to be made based on financial analyses rather than on clinical needs identified by physicians. As a result, medical directors are encouraged to be mindful of the effect of their suggestions on the bottom line of the organization. This has resulted in a very significant shift away from programs that are needed but not funded, and toward programs that are revenue-positive or at least neutral.

Medical directors who do not conform in this way are unlikely to be part of the administration for very long in the present environment.

Continue to: What training qualifications are required or desirable to assume a medical leadership role (post residency fellowship, MBA, etc.)?

Dr. Stanciu: What training qualifications are required or desirable to assume a medical leadership role (post-residency fellowship, MBA, etc.)?

Dr. Penders: In addition to a foundation in evidence-based practices and knowledge of regulatory requirements, general leadership skills are probably the most important qualities for medical leadership. Hospitals are complex organizations with confusing reporting relationships. Negotiation skills and communication skills are critical to success. Because most modern health care organizations are well staffed with administrative personnel trained in business and finance, I would not suggest that an MBA is necessary or even important to a medical director’s success. Having said that, there are an increasing number of physicians assuming the role of chief executive officer in complex health care systems. In this case, MBA training will likely be advantageous.

I would suggest that the focus of training that occurs in MPH programs would provide more relevant tools for those in positions of medical leadership. Skills such as biostatistics and epidemiology provide those in such positions with the perspective required to understand the effectiveness of health care systems, and to relate to changes that might be beneficial to the populations they serve. A firm foundation in information systems and data analysis is becoming increasingly important as the payment system moves toward one that is value-based. Increasingly, health care systems decisions will be guided by the analysis of aggregated information gathered from electronic medical records.

Dr. Stanciu: What personal qualities makes a psychiatric physician well-suited for the role of a medical director?

Dr. Penders: Medical directors will confront a variety of difficult situations with colleagues, administrative staff, patients, and family members. A calm demeanor with an ability to reflect rather than react is important. As I previously mentioned, an ability to communicate, including strength as a listener, is another personality trait valued in this position.

Continue to: What are some of the challenges you face on a daily basis?

Dr. Stanciu: What are some of the challenges you face on a daily basis?

Dr. Penders: There are challenges in multiple areas. First and foremost, medical leadership is responsible for maintaining and improving the quality of patient care and experience. One can expect frequent conflicts to arise when providers vary from established standards or disagree with established policies.

Additionally, there appears to be an increasing lack of a distinct line between administrative and patient care decisions. It is often a challenge to manage the conflicting incentives involved when cost containment and quality care are seen to diverge.

Dr. Stanciu: What are the metrics that measure success by a medical administrator?