User login

Genetic screening and diagnosis: Key advancements and the role of genetic counseling

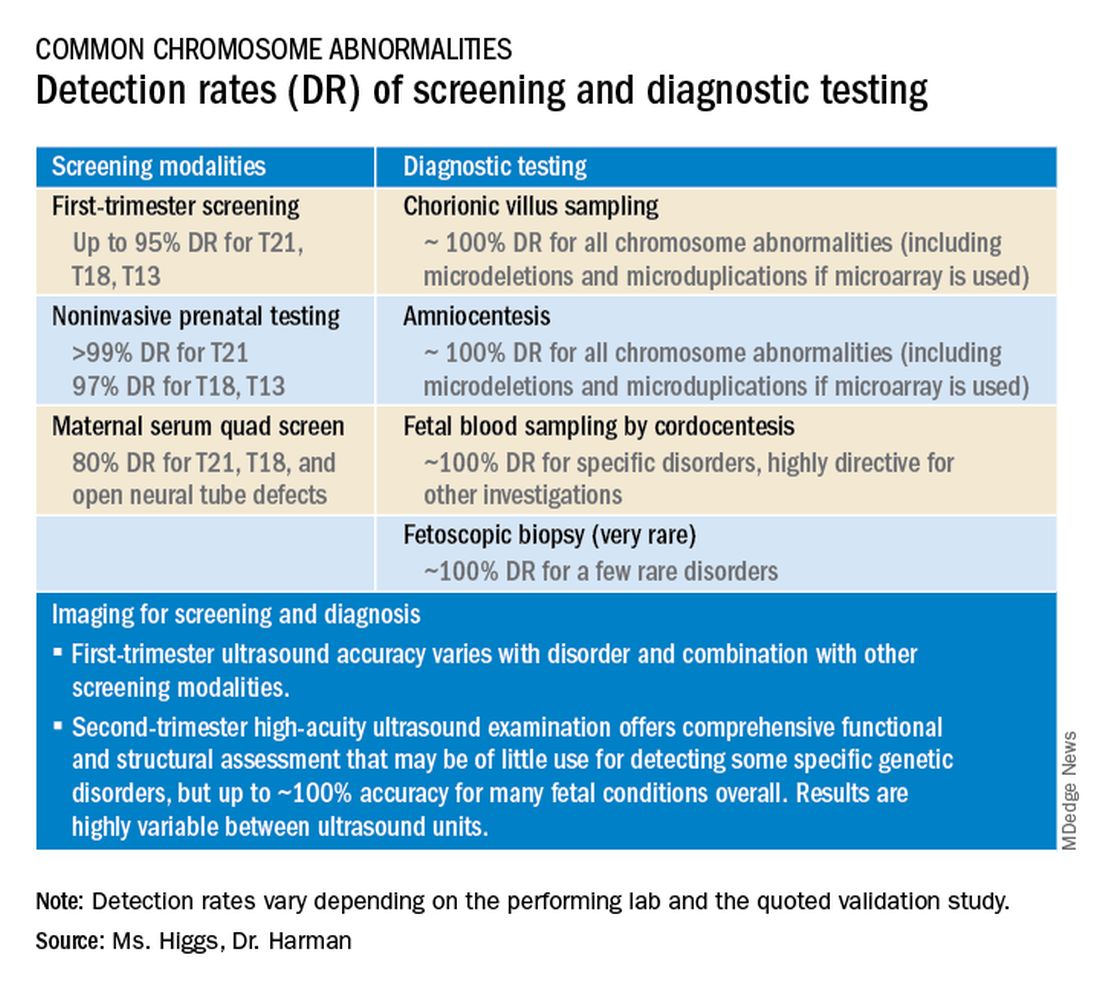

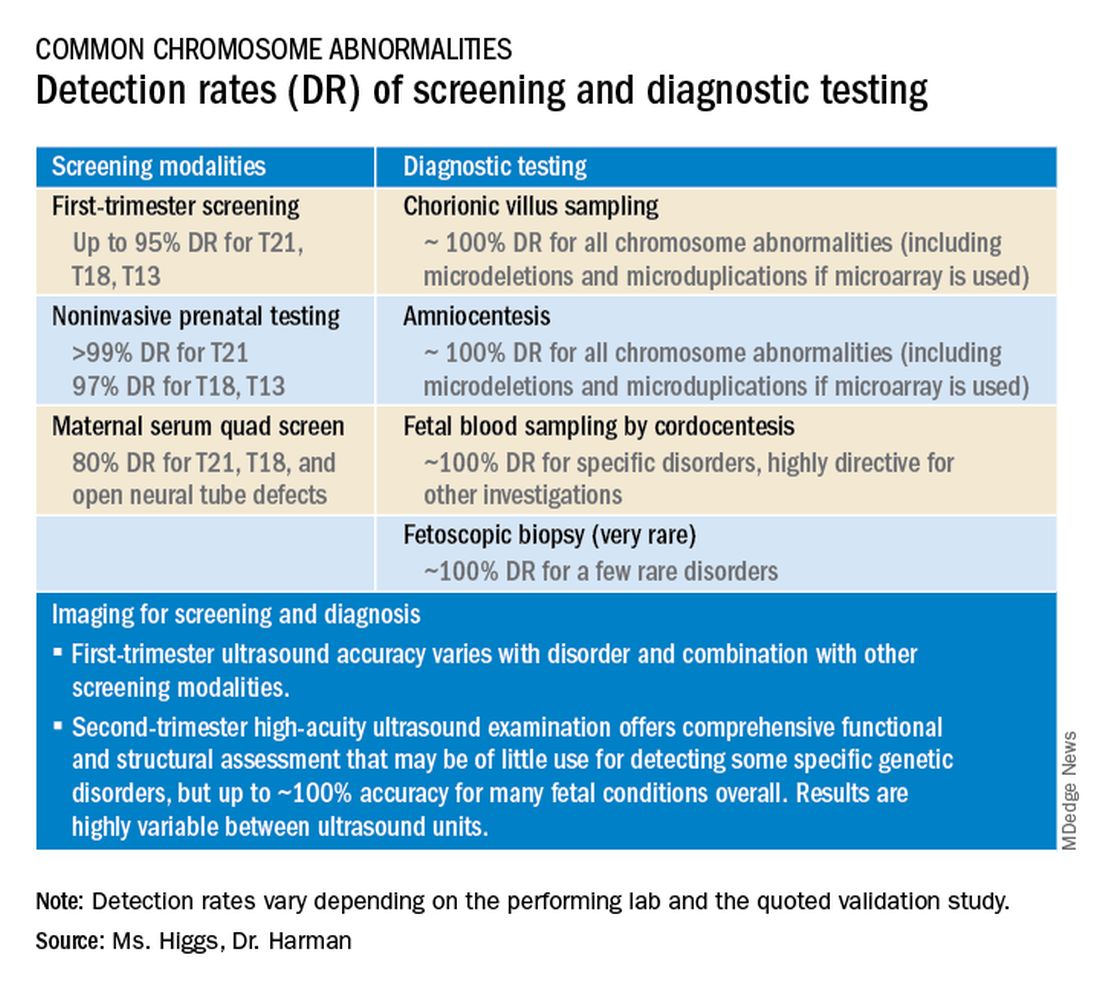

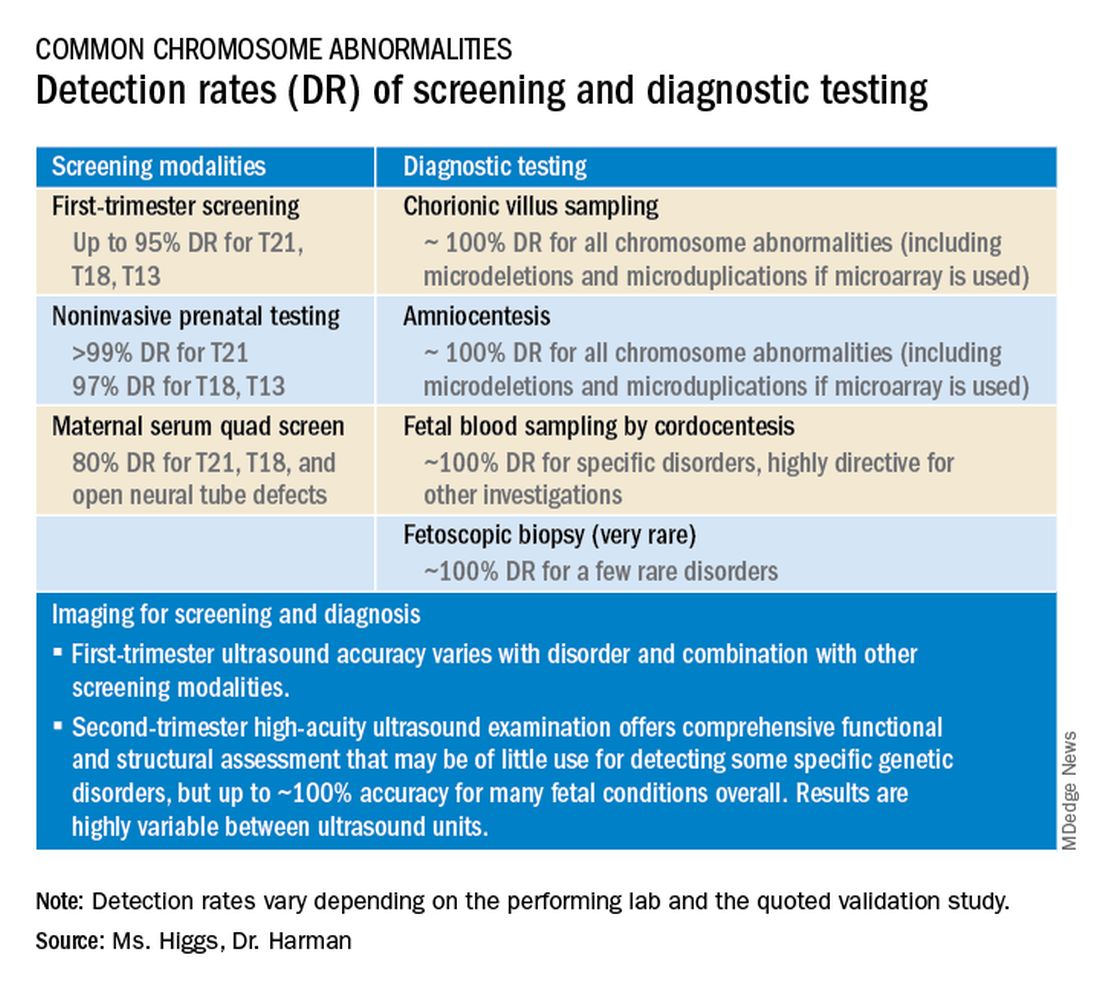

Preconception and prenatal genetic screening and diagnostic testing for genetic disorders are increasingly complex, with a burgeoning number of testing options and a shift in screening from situations identified as high-risk to more universal considerations. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists now recommends that all patients – regardless of age or risk for chromosomal abnormalities – be offered both screening and diagnostic tests and counseled about the relative benefits and limitations of available tests. These recommendations represent a sea change for obstetrics.

Screening options now include expanded carrier screening that evaluates an individual’s carrier status for multiple conditions at once, regardless of ethnicity, and cell-free DNA screening using fetal DNA found in the maternal circulation. Chromosomal microarray analysis from a chorionic villus sampling or amniocentesis specimen detects tiny copy number variants, and increasingly detailed ultrasound images illuminate anatomic and physiologic anomalies that could not be seen or interpreted as recently as 5 years ago.

These advancements are remarkable, but they require attentive, personalized pre- and posttest genetic counseling. Genetic counselors are critical to this process, helping women and families understand and select screening tools, interpret test results, select diagnostic panels, and make decisions about invasive testing.

Counseling is essential as we seek and utilize genetic information that is no longer binary. It used to be that predictions of normality and abnormality were made with little gray area in between. – and genetic diagnosis is increasingly a lattice of details, variable expression, and even effects timing.

Expanded carrier screening

Carrier screening to determine if one or both parents are carriers for an autosomal recessive condition has historically involved a limited number of conditions chosen based on ethnicity. However, research has demonstrated the unreliability of this approach in our multicultural, multiracial society, in which many of our patients have mixed or uncertain race and ethnicity.

Expanded carrier screening is nondirective and takes ethnic background out of the equation. ACOG has moved from advocating ethnic-based screening alone to advising that both ethnic and expanded carrier screening are acceptable strategies and that practices should choose a standard approach to offer and discuss with each patient. (Carrier screening for cystic fibrosis and spinal muscular atrophy are recommended for all patients regardless of ethnicity.)

In any scenario, screening is optimally performed after counseling and prior to pregnancy when patients can fully consider their reproductive options; couples identified to be at 25% risk to have a child with a genetic condition may choose to pursue in-vitro fertilization and preimplantation genetic testing of embryos.

The expanded carrier screening panels offered by laboratories include as many as several hundred conditions, so careful scrutiny of included diseases and selection of a panel is important. We currently use an expanded panel that is restricted to conditions that limit life expectancy, have no treatment, have treatment that is most beneficial when started early, or are associated with intellectual disability.

Some panels look for mutations in genes that are quite common and often benign. Such is the case with the MTHFR gene: 40% of individuals in some populations are carriers, and offspring who inherit mutations in both gene copies are unlikely to have any medical issues at all. Yet, the lay information available on this gene can be confusing and even scary.

Laboratory methodologies should similarly be well understood. Many labs look only for a handful of common mutations in a gene, while others sequence or “read” the entire gene, looking for errors. The latter is more informative, but not all labs that purport to sequence the entire gene are actually doing so.

Patients should understand that, while a negative result significantly reduces their chance of being a carrier for a condition, it does not eliminate the risk. They should also understand that, if their partner is not available for testing or is unwilling to be tested, we will not be able to refine the risk to the pregnancy in the event they are found to be a carrier.

Noninvasive prenatal screening

Cell-free DNA testing, or noninvasive prenatal testing (NIPT), is a powerful noninvasive screening technology for aneuploidy that analyzes fetal DNA floating freely in maternal blood starting at about 9-10 weeks of pregnancy. However, it is not a substitute for invasive testing and is not diagnostic.

Patients we see are commonly misinformed that a negative cell-free DNA testing result means their baby is without doubt unaffected by a chromosomal abnormality. NIPT is the most sensitive and specific screening test for the common fetal aneuploidies (trisomies 13, 18, and 21), with a significantly better positive predictive value than previous noninvasive chromosome screening. However, NIPT findings still include false-negative results and some false-positive results. Patients must be counseled that NIPT does not offer absolute findings.

Laboratories are adding screening tests for additional aneuploidies, microdeletions, and other disorders and variants. However, as ACOG and other professional colleges advise, the reliability of these tests (e.g.. their screening accuracy with respect to detection and false-positive rates) is not yet established, and these newer tests are not ready for routine adoption in practice.

Microarray analysis, variants of unknown significance (VUS)

Chromosomal microarray analysis of DNA from a chorionic villus sampling or amniocentesis specimen enables prenatal detection of exceptionally small genomic deletions and duplications – tiny chunks of DNA – that cannot be seen with standard karyotype testing.

That microdeletions and microduplications can produce abnormalities and conditions that can be significantly more severe than the absence or addition of entire chromosomes is not necessarily intuitive. It is as if the entire plot of a book is revealed in just one page.

For instance, Turner syndrome results when one of the X chromosomes is entirely missing. (Occasionally, there is a large, partial absence.) The absence can cause a variety of symptoms, including failure of the ovaries to develop and heart defects, but most affected individuals can lead healthy and independent lives with the only features being short stature and a wide neck.

Angelman syndrome, in contrast, is most often caused by a microdeletion of genetic material from chromosome 15 – a tiny snip of the chromosome – but results in ataxia, severe intellectual disability, lifelong seizures, and severe lifelong speech impairment.

In our program, we counsel patients before testing that results may come back one of three ways: completely normal, definitely abnormal, or with a VUS.

A VUS is a challenging finding because it represents a loss or gain of a small portion of a chromosome with unclear clinical significance. In some cases, the uncertainty stems from the microdeletion or duplication not having been seen before — or not seen enough to be accurately characterized as benign or pathogenic. In other cases, the uncertainty stems from an associated phenotype that is highly variable. Either way, a VUS often makes the investigation for genetic conditions and subsequent decision-making more difficult, and a genetic counselor’s expertise and guidance is needed.

Advances in imaging, panel testing

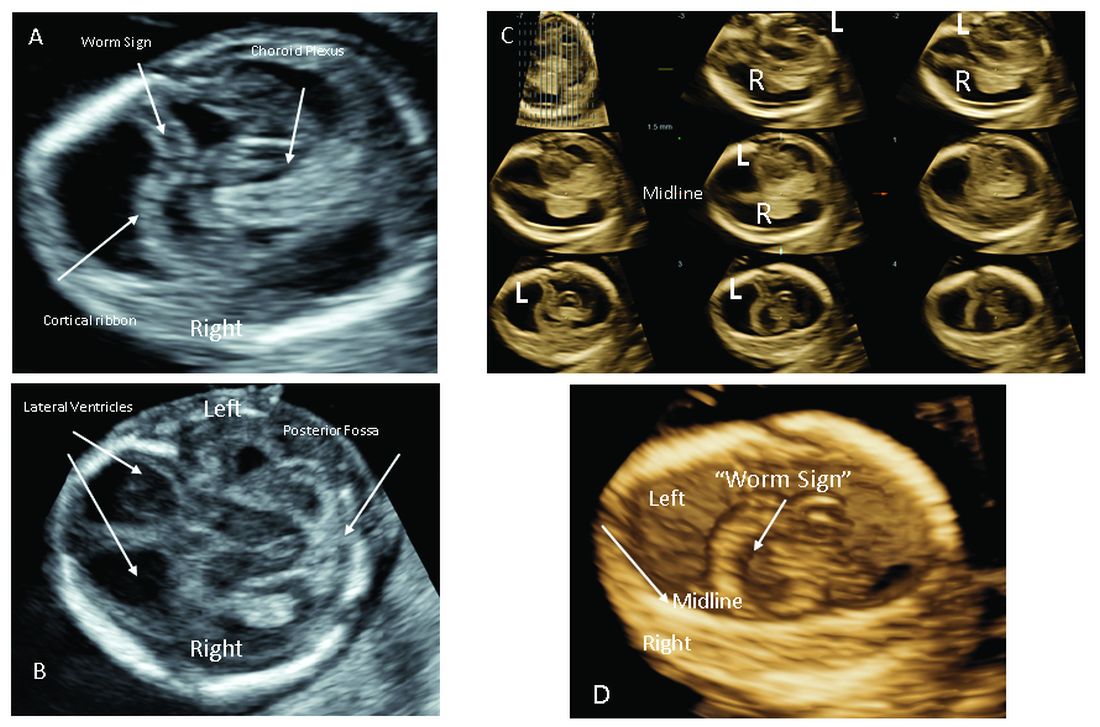

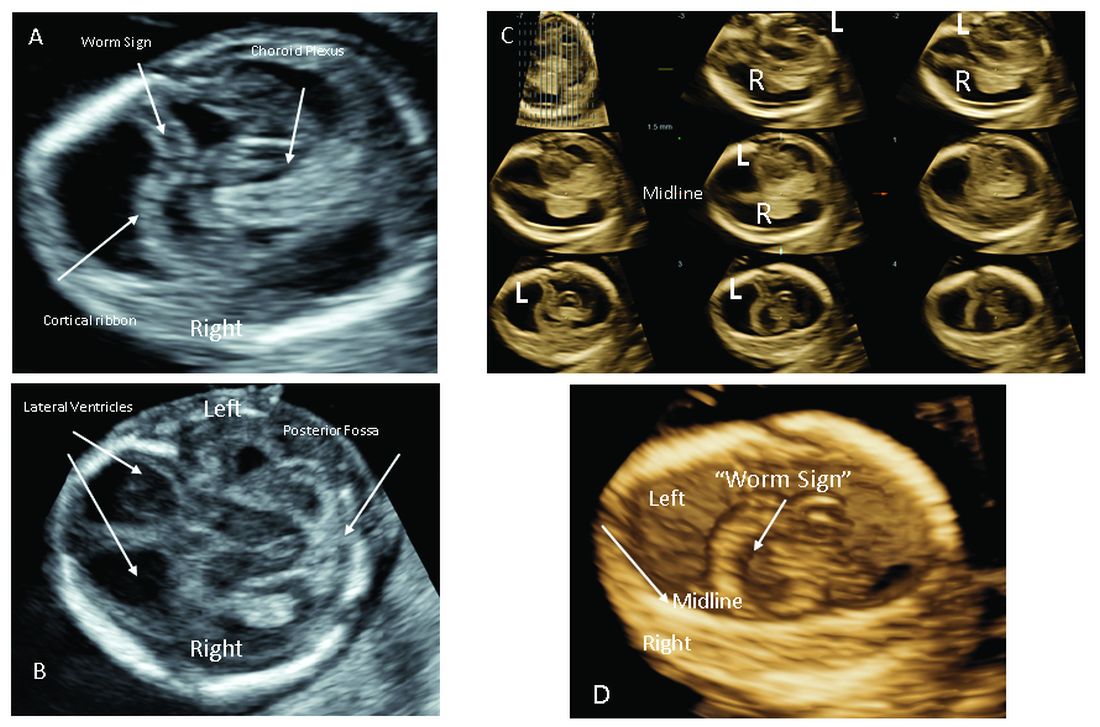

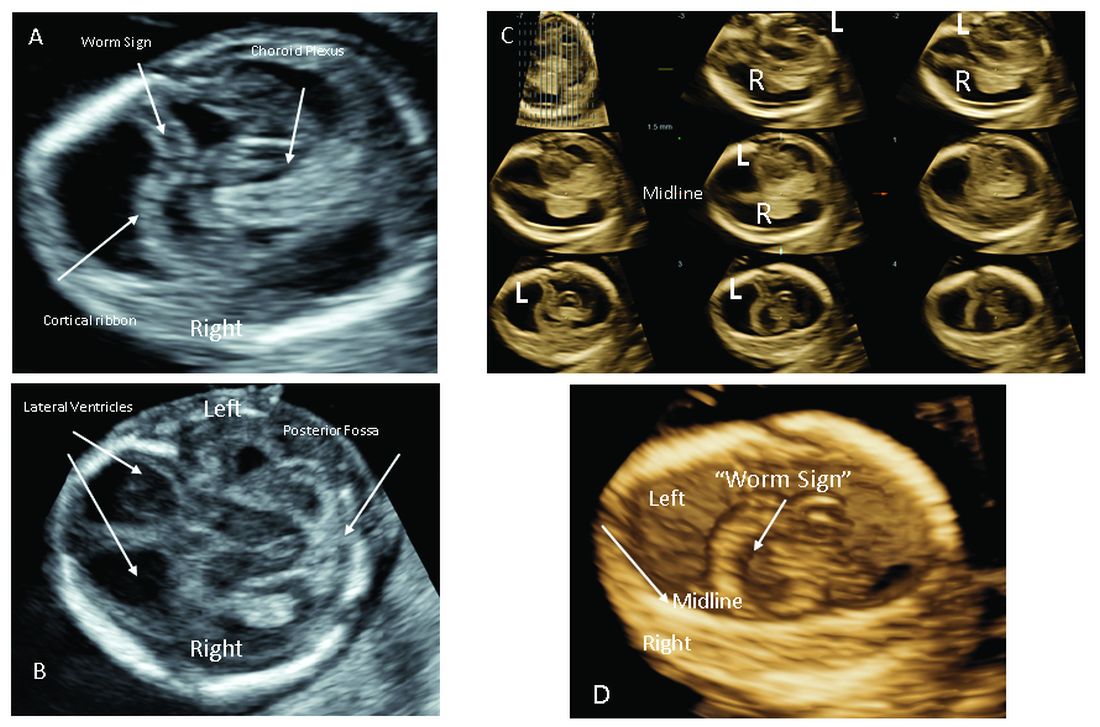

The most significant addition to the first-trimester ultrasound evaluation in recent years has been the systematic assessment of the fetal circulation and the structure of the fetal heart, with early detection of the most common forms of birth defects.

Structural assessment of the central nervous system, abdomen, and skeleton is also now possible during the first-trimester ultrasound and offers the opportunity for early genetic assessment when anomalies are detected.

Ultrasound imaging in the second and third trimesters can help refine the diagnosis of birth defects, track the evolution of suspicious findings from the first trimester, or uncover anomalies that did not present earlier. Findings may be suggestive of underlying genetic conditions and drive the use of “panel” tests, or targeted sequencing panels, to help make a diagnosis.

Features of skeletal dysplasia, for instance, would lead the genetic counselor to recommend a panel of tests that target skeletal dysplasia-associated genes, looking for genetic mutations. Similarly, holoprosencephaly detected on ultrasound could prompt use of a customized gene panel to look for mutations in a series of different genes known to cause the anomaly.

Second trimester details that may guide genetic investigation are not limited to ultrasound. In certain instances, MRI has the unique capability to diagnose particular structural defects, especially brain anomalies with developmental specificity.

Commentary by Christopher R. Harman, MD

Genetic counseling is now a mandatory part of all pregnancy evaluation programs. Counselors not only explain and interpret tests and results to families but also, increasingly, guide the efforts of the obstetrics team, including the maternal-fetal medicine specialist.

The genetic counselor helps design screening for the whole patient population and focuses diagnostic testing in specific cases of screening concerns, family history, chromosomal abnormalities in prior pregnancies, and fetal abnormalities detected through ultrasonography or other prenatal surveillance. They also serve as a crucial link between the physician and the family.

The counselor also has a key role in the case of a stillbirth or other adverse pregnancy outcome in investigating possible genetic elements and working with the family on evaluation of recurrence risk and prevention of a similar outcome in future pregnancies. The details of poor outcomes hold the potential for making the next pregnancy successful.

Commentary by Amanda S. Higgs, MGC

Even in 2021, there is no “perfect baby test.” Patients can have expanded carrier screening, cell-free DNA testing, invasive testing with microarray, and all of the available imaging, with normal results, and still have a baby with a genetic disorder. Understanding the concept of residual risk is important. So is appreciation for the possibility that incidental findings – information not sought – can occur even with specific genetic testing.

Genetic counselors are there to help patients understand and assimilate information, usher them through the screening and testing process, and facilitate informed decision-making. We are nondirective in our counseling. We try to assess their values, their support systems, and their experience with disability and help them to make the best decisions for themselves regarding testing and further evaluation, as well as other reproductive decisions.

obnews@mdedge.com

Preconception and prenatal genetic screening and diagnostic testing for genetic disorders are increasingly complex, with a burgeoning number of testing options and a shift in screening from situations identified as high-risk to more universal considerations. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists now recommends that all patients – regardless of age or risk for chromosomal abnormalities – be offered both screening and diagnostic tests and counseled about the relative benefits and limitations of available tests. These recommendations represent a sea change for obstetrics.

Screening options now include expanded carrier screening that evaluates an individual’s carrier status for multiple conditions at once, regardless of ethnicity, and cell-free DNA screening using fetal DNA found in the maternal circulation. Chromosomal microarray analysis from a chorionic villus sampling or amniocentesis specimen detects tiny copy number variants, and increasingly detailed ultrasound images illuminate anatomic and physiologic anomalies that could not be seen or interpreted as recently as 5 years ago.

These advancements are remarkable, but they require attentive, personalized pre- and posttest genetic counseling. Genetic counselors are critical to this process, helping women and families understand and select screening tools, interpret test results, select diagnostic panels, and make decisions about invasive testing.

Counseling is essential as we seek and utilize genetic information that is no longer binary. It used to be that predictions of normality and abnormality were made with little gray area in between. – and genetic diagnosis is increasingly a lattice of details, variable expression, and even effects timing.

Expanded carrier screening

Carrier screening to determine if one or both parents are carriers for an autosomal recessive condition has historically involved a limited number of conditions chosen based on ethnicity. However, research has demonstrated the unreliability of this approach in our multicultural, multiracial society, in which many of our patients have mixed or uncertain race and ethnicity.

Expanded carrier screening is nondirective and takes ethnic background out of the equation. ACOG has moved from advocating ethnic-based screening alone to advising that both ethnic and expanded carrier screening are acceptable strategies and that practices should choose a standard approach to offer and discuss with each patient. (Carrier screening for cystic fibrosis and spinal muscular atrophy are recommended for all patients regardless of ethnicity.)

In any scenario, screening is optimally performed after counseling and prior to pregnancy when patients can fully consider their reproductive options; couples identified to be at 25% risk to have a child with a genetic condition may choose to pursue in-vitro fertilization and preimplantation genetic testing of embryos.

The expanded carrier screening panels offered by laboratories include as many as several hundred conditions, so careful scrutiny of included diseases and selection of a panel is important. We currently use an expanded panel that is restricted to conditions that limit life expectancy, have no treatment, have treatment that is most beneficial when started early, or are associated with intellectual disability.

Some panels look for mutations in genes that are quite common and often benign. Such is the case with the MTHFR gene: 40% of individuals in some populations are carriers, and offspring who inherit mutations in both gene copies are unlikely to have any medical issues at all. Yet, the lay information available on this gene can be confusing and even scary.

Laboratory methodologies should similarly be well understood. Many labs look only for a handful of common mutations in a gene, while others sequence or “read” the entire gene, looking for errors. The latter is more informative, but not all labs that purport to sequence the entire gene are actually doing so.

Patients should understand that, while a negative result significantly reduces their chance of being a carrier for a condition, it does not eliminate the risk. They should also understand that, if their partner is not available for testing or is unwilling to be tested, we will not be able to refine the risk to the pregnancy in the event they are found to be a carrier.

Noninvasive prenatal screening

Cell-free DNA testing, or noninvasive prenatal testing (NIPT), is a powerful noninvasive screening technology for aneuploidy that analyzes fetal DNA floating freely in maternal blood starting at about 9-10 weeks of pregnancy. However, it is not a substitute for invasive testing and is not diagnostic.

Patients we see are commonly misinformed that a negative cell-free DNA testing result means their baby is without doubt unaffected by a chromosomal abnormality. NIPT is the most sensitive and specific screening test for the common fetal aneuploidies (trisomies 13, 18, and 21), with a significantly better positive predictive value than previous noninvasive chromosome screening. However, NIPT findings still include false-negative results and some false-positive results. Patients must be counseled that NIPT does not offer absolute findings.

Laboratories are adding screening tests for additional aneuploidies, microdeletions, and other disorders and variants. However, as ACOG and other professional colleges advise, the reliability of these tests (e.g.. their screening accuracy with respect to detection and false-positive rates) is not yet established, and these newer tests are not ready for routine adoption in practice.

Microarray analysis, variants of unknown significance (VUS)

Chromosomal microarray analysis of DNA from a chorionic villus sampling or amniocentesis specimen enables prenatal detection of exceptionally small genomic deletions and duplications – tiny chunks of DNA – that cannot be seen with standard karyotype testing.

That microdeletions and microduplications can produce abnormalities and conditions that can be significantly more severe than the absence or addition of entire chromosomes is not necessarily intuitive. It is as if the entire plot of a book is revealed in just one page.

For instance, Turner syndrome results when one of the X chromosomes is entirely missing. (Occasionally, there is a large, partial absence.) The absence can cause a variety of symptoms, including failure of the ovaries to develop and heart defects, but most affected individuals can lead healthy and independent lives with the only features being short stature and a wide neck.

Angelman syndrome, in contrast, is most often caused by a microdeletion of genetic material from chromosome 15 – a tiny snip of the chromosome – but results in ataxia, severe intellectual disability, lifelong seizures, and severe lifelong speech impairment.

In our program, we counsel patients before testing that results may come back one of three ways: completely normal, definitely abnormal, or with a VUS.

A VUS is a challenging finding because it represents a loss or gain of a small portion of a chromosome with unclear clinical significance. In some cases, the uncertainty stems from the microdeletion or duplication not having been seen before — or not seen enough to be accurately characterized as benign or pathogenic. In other cases, the uncertainty stems from an associated phenotype that is highly variable. Either way, a VUS often makes the investigation for genetic conditions and subsequent decision-making more difficult, and a genetic counselor’s expertise and guidance is needed.

Advances in imaging, panel testing

The most significant addition to the first-trimester ultrasound evaluation in recent years has been the systematic assessment of the fetal circulation and the structure of the fetal heart, with early detection of the most common forms of birth defects.

Structural assessment of the central nervous system, abdomen, and skeleton is also now possible during the first-trimester ultrasound and offers the opportunity for early genetic assessment when anomalies are detected.

Ultrasound imaging in the second and third trimesters can help refine the diagnosis of birth defects, track the evolution of suspicious findings from the first trimester, or uncover anomalies that did not present earlier. Findings may be suggestive of underlying genetic conditions and drive the use of “panel” tests, or targeted sequencing panels, to help make a diagnosis.

Features of skeletal dysplasia, for instance, would lead the genetic counselor to recommend a panel of tests that target skeletal dysplasia-associated genes, looking for genetic mutations. Similarly, holoprosencephaly detected on ultrasound could prompt use of a customized gene panel to look for mutations in a series of different genes known to cause the anomaly.

Second trimester details that may guide genetic investigation are not limited to ultrasound. In certain instances, MRI has the unique capability to diagnose particular structural defects, especially brain anomalies with developmental specificity.

Commentary by Christopher R. Harman, MD

Genetic counseling is now a mandatory part of all pregnancy evaluation programs. Counselors not only explain and interpret tests and results to families but also, increasingly, guide the efforts of the obstetrics team, including the maternal-fetal medicine specialist.

The genetic counselor helps design screening for the whole patient population and focuses diagnostic testing in specific cases of screening concerns, family history, chromosomal abnormalities in prior pregnancies, and fetal abnormalities detected through ultrasonography or other prenatal surveillance. They also serve as a crucial link between the physician and the family.

The counselor also has a key role in the case of a stillbirth or other adverse pregnancy outcome in investigating possible genetic elements and working with the family on evaluation of recurrence risk and prevention of a similar outcome in future pregnancies. The details of poor outcomes hold the potential for making the next pregnancy successful.

Commentary by Amanda S. Higgs, MGC

Even in 2021, there is no “perfect baby test.” Patients can have expanded carrier screening, cell-free DNA testing, invasive testing with microarray, and all of the available imaging, with normal results, and still have a baby with a genetic disorder. Understanding the concept of residual risk is important. So is appreciation for the possibility that incidental findings – information not sought – can occur even with specific genetic testing.

Genetic counselors are there to help patients understand and assimilate information, usher them through the screening and testing process, and facilitate informed decision-making. We are nondirective in our counseling. We try to assess their values, their support systems, and their experience with disability and help them to make the best decisions for themselves regarding testing and further evaluation, as well as other reproductive decisions.

obnews@mdedge.com

Preconception and prenatal genetic screening and diagnostic testing for genetic disorders are increasingly complex, with a burgeoning number of testing options and a shift in screening from situations identified as high-risk to more universal considerations. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists now recommends that all patients – regardless of age or risk for chromosomal abnormalities – be offered both screening and diagnostic tests and counseled about the relative benefits and limitations of available tests. These recommendations represent a sea change for obstetrics.

Screening options now include expanded carrier screening that evaluates an individual’s carrier status for multiple conditions at once, regardless of ethnicity, and cell-free DNA screening using fetal DNA found in the maternal circulation. Chromosomal microarray analysis from a chorionic villus sampling or amniocentesis specimen detects tiny copy number variants, and increasingly detailed ultrasound images illuminate anatomic and physiologic anomalies that could not be seen or interpreted as recently as 5 years ago.

These advancements are remarkable, but they require attentive, personalized pre- and posttest genetic counseling. Genetic counselors are critical to this process, helping women and families understand and select screening tools, interpret test results, select diagnostic panels, and make decisions about invasive testing.

Counseling is essential as we seek and utilize genetic information that is no longer binary. It used to be that predictions of normality and abnormality were made with little gray area in between. – and genetic diagnosis is increasingly a lattice of details, variable expression, and even effects timing.

Expanded carrier screening

Carrier screening to determine if one or both parents are carriers for an autosomal recessive condition has historically involved a limited number of conditions chosen based on ethnicity. However, research has demonstrated the unreliability of this approach in our multicultural, multiracial society, in which many of our patients have mixed or uncertain race and ethnicity.

Expanded carrier screening is nondirective and takes ethnic background out of the equation. ACOG has moved from advocating ethnic-based screening alone to advising that both ethnic and expanded carrier screening are acceptable strategies and that practices should choose a standard approach to offer and discuss with each patient. (Carrier screening for cystic fibrosis and spinal muscular atrophy are recommended for all patients regardless of ethnicity.)

In any scenario, screening is optimally performed after counseling and prior to pregnancy when patients can fully consider their reproductive options; couples identified to be at 25% risk to have a child with a genetic condition may choose to pursue in-vitro fertilization and preimplantation genetic testing of embryos.

The expanded carrier screening panels offered by laboratories include as many as several hundred conditions, so careful scrutiny of included diseases and selection of a panel is important. We currently use an expanded panel that is restricted to conditions that limit life expectancy, have no treatment, have treatment that is most beneficial when started early, or are associated with intellectual disability.

Some panels look for mutations in genes that are quite common and often benign. Such is the case with the MTHFR gene: 40% of individuals in some populations are carriers, and offspring who inherit mutations in both gene copies are unlikely to have any medical issues at all. Yet, the lay information available on this gene can be confusing and even scary.

Laboratory methodologies should similarly be well understood. Many labs look only for a handful of common mutations in a gene, while others sequence or “read” the entire gene, looking for errors. The latter is more informative, but not all labs that purport to sequence the entire gene are actually doing so.

Patients should understand that, while a negative result significantly reduces their chance of being a carrier for a condition, it does not eliminate the risk. They should also understand that, if their partner is not available for testing or is unwilling to be tested, we will not be able to refine the risk to the pregnancy in the event they are found to be a carrier.

Noninvasive prenatal screening

Cell-free DNA testing, or noninvasive prenatal testing (NIPT), is a powerful noninvasive screening technology for aneuploidy that analyzes fetal DNA floating freely in maternal blood starting at about 9-10 weeks of pregnancy. However, it is not a substitute for invasive testing and is not diagnostic.

Patients we see are commonly misinformed that a negative cell-free DNA testing result means their baby is without doubt unaffected by a chromosomal abnormality. NIPT is the most sensitive and specific screening test for the common fetal aneuploidies (trisomies 13, 18, and 21), with a significantly better positive predictive value than previous noninvasive chromosome screening. However, NIPT findings still include false-negative results and some false-positive results. Patients must be counseled that NIPT does not offer absolute findings.

Laboratories are adding screening tests for additional aneuploidies, microdeletions, and other disorders and variants. However, as ACOG and other professional colleges advise, the reliability of these tests (e.g.. their screening accuracy with respect to detection and false-positive rates) is not yet established, and these newer tests are not ready for routine adoption in practice.

Microarray analysis, variants of unknown significance (VUS)

Chromosomal microarray analysis of DNA from a chorionic villus sampling or amniocentesis specimen enables prenatal detection of exceptionally small genomic deletions and duplications – tiny chunks of DNA – that cannot be seen with standard karyotype testing.

That microdeletions and microduplications can produce abnormalities and conditions that can be significantly more severe than the absence or addition of entire chromosomes is not necessarily intuitive. It is as if the entire plot of a book is revealed in just one page.

For instance, Turner syndrome results when one of the X chromosomes is entirely missing. (Occasionally, there is a large, partial absence.) The absence can cause a variety of symptoms, including failure of the ovaries to develop and heart defects, but most affected individuals can lead healthy and independent lives with the only features being short stature and a wide neck.

Angelman syndrome, in contrast, is most often caused by a microdeletion of genetic material from chromosome 15 – a tiny snip of the chromosome – but results in ataxia, severe intellectual disability, lifelong seizures, and severe lifelong speech impairment.

In our program, we counsel patients before testing that results may come back one of three ways: completely normal, definitely abnormal, or with a VUS.

A VUS is a challenging finding because it represents a loss or gain of a small portion of a chromosome with unclear clinical significance. In some cases, the uncertainty stems from the microdeletion or duplication not having been seen before — or not seen enough to be accurately characterized as benign or pathogenic. In other cases, the uncertainty stems from an associated phenotype that is highly variable. Either way, a VUS often makes the investigation for genetic conditions and subsequent decision-making more difficult, and a genetic counselor’s expertise and guidance is needed.

Advances in imaging, panel testing

The most significant addition to the first-trimester ultrasound evaluation in recent years has been the systematic assessment of the fetal circulation and the structure of the fetal heart, with early detection of the most common forms of birth defects.

Structural assessment of the central nervous system, abdomen, and skeleton is also now possible during the first-trimester ultrasound and offers the opportunity for early genetic assessment when anomalies are detected.

Ultrasound imaging in the second and third trimesters can help refine the diagnosis of birth defects, track the evolution of suspicious findings from the first trimester, or uncover anomalies that did not present earlier. Findings may be suggestive of underlying genetic conditions and drive the use of “panel” tests, or targeted sequencing panels, to help make a diagnosis.

Features of skeletal dysplasia, for instance, would lead the genetic counselor to recommend a panel of tests that target skeletal dysplasia-associated genes, looking for genetic mutations. Similarly, holoprosencephaly detected on ultrasound could prompt use of a customized gene panel to look for mutations in a series of different genes known to cause the anomaly.

Second trimester details that may guide genetic investigation are not limited to ultrasound. In certain instances, MRI has the unique capability to diagnose particular structural defects, especially brain anomalies with developmental specificity.

Commentary by Christopher R. Harman, MD

Genetic counseling is now a mandatory part of all pregnancy evaluation programs. Counselors not only explain and interpret tests and results to families but also, increasingly, guide the efforts of the obstetrics team, including the maternal-fetal medicine specialist.

The genetic counselor helps design screening for the whole patient population and focuses diagnostic testing in specific cases of screening concerns, family history, chromosomal abnormalities in prior pregnancies, and fetal abnormalities detected through ultrasonography or other prenatal surveillance. They also serve as a crucial link between the physician and the family.

The counselor also has a key role in the case of a stillbirth or other adverse pregnancy outcome in investigating possible genetic elements and working with the family on evaluation of recurrence risk and prevention of a similar outcome in future pregnancies. The details of poor outcomes hold the potential for making the next pregnancy successful.

Commentary by Amanda S. Higgs, MGC

Even in 2021, there is no “perfect baby test.” Patients can have expanded carrier screening, cell-free DNA testing, invasive testing with microarray, and all of the available imaging, with normal results, and still have a baby with a genetic disorder. Understanding the concept of residual risk is important. So is appreciation for the possibility that incidental findings – information not sought – can occur even with specific genetic testing.

Genetic counselors are there to help patients understand and assimilate information, usher them through the screening and testing process, and facilitate informed decision-making. We are nondirective in our counseling. We try to assess their values, their support systems, and their experience with disability and help them to make the best decisions for themselves regarding testing and further evaluation, as well as other reproductive decisions.

obnews@mdedge.com