User login

Gut Grief: The Truth About Gluten Sensitivity

IN THIS ARTICLE

• So what is gluten?

• Selected symptoms of celiac disease

• Selected foods and products containing gluten

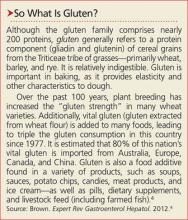

Gluten has become a dietary pariah (see “So What Is Gluten?"). The American public’s enthusiasm for a gluten-free diet has spurred a gluten-free food industry that has grown, on average, 34% per year since 2009, with annual sales predicted to reach an impressive $15.5 billion by 2016.1 This trend coincides with the national media’s intense focus on gluten sensitivity (GS), as well as best-selling books such as Wheat Belly and Grain Brain.2,3

Gluten-free food products, once relegated to boutique food shops and limited shelf space, now fill sections in large grocery and drugstore chains. Many restaurants have added gluten-free items to their menus (although gluten-free Big Macs have been available in Finland for more than 20 years).4 Only celiac disease (CD), which affects approximately 1% of the American population, requires strict gluten avoidance; yet more than 30% of US adults report having reduced their gluten intake, most claiming they did so to promote a “healthier” diet or support weight loss.1

PREVALENCE AND PATHOLOGY OF GS DISORDERS

Gluten sensitivity, once used to denote CD alone, now includes a group of gluten-intolerant conditions unrelated to CD—primarily nonceliac gluten sensitivity (NCGS) and wheat allergy (WA)—although the nomenclature is likely to change. While these disorders differ in underlying pathogenesis, each demonstrates a resolution of symptoms when the patient is placed on a gluten-free diet. Of these GS disorders, only NCGS lacks clarity with regard to incidence, diagnosis, and pathology.5

Celiac Disease

Celiac disease is an autoimmune, T-cell–activated disease that manifests in genetically susceptible individuals (with gene variants HLA-DQ2 and HLA-DQ8); it can occur at any age. The incidence of CD in the US has increased from 1 in 500 in 1974 to a current estimate of 1 in 100, although many with CD are believed to be undiagnosed.4,6

CD is the only autoimmune disease for which a trigger is known: gluten. Suspicion for CD should be heightened if the patient or a family member has a history of autoimmune disease. Nearly one-quarter of patients with CD will develop an autoimmune thyroid disorder.7

In CD, a significant enteropathy occurs in response to gluten intake, characterized by inflammation of the proximal small intestine. Individuals with CD produce tissue transglutaminase (tTG) or transglutaminase 2 (TG2) autoantibodies, resulting in gluten-specific CD4+ Th1 T-cell activation and an immune response that causes an upregulation of zonulin.8 Zonulin, a protein that modulates the permeability of the intestinal mucosal wall, is believed to play a role in “leaky gut syndrome” and autoimmune disease. The upregulation of zonulin in CD creates a disruption of the intestinal mucosal lining, causing villous mucosal atrophy and impairment of intestinal permeability and absorption.9

Nonceliac Gluten Sensitivity

NCGS is a poorly understood condition first described in the 1980s and recently “rediscovered” as a gluten-related disorder.10 Its actual prevalence is unknown because of unclear diagnostic criteria but is likely much higher than that of CD.1,4 Unlike CD, there does not appear to be a genetic predisposition for NCGS, nor is it believed to be an autoimmune disorder. However, research does suggest that NCGS may increase the risk for autoimmune diseases, such as Hashimoto thyroiditis. NCGS can occur at any age but appears more commonly in adults than children, and in women than men.4

A small but meticulous 2013 study raised doubt about NCGS as a specific gluten-related disorder.11 The results suggested that NCGS should be viewed as a variant of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), not triggered by gluten but by poorly absorbed carbohydrates found in wheat known as fructans and galactans, and perhaps by other foods containing fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides, and polyols (FODMAPS). It is believed those with diarrhea-prone IBS are particularly sensitive to gluten.11 As a result, ardent claims of NCGS and improved health with gluten-free diets in those without CD are often discounted.

More recent research findings refute this conjecture, suggesting that NCGS is likely a reaction to other proteins within the gluten family, such as beta-, gamma-, or omega-gliadin, glutenin, wheat germ agglutinin, gluteomorphin, and deamidated gliadin. Development of GS is believed to be triggered by such factors as intestinal infections, altered microbiota, or food additives.4

In any event, the pathogenesis of NCGS remains unclear, and it does not present with the diagnostic antibodies or inflammatory enteropathy seen in patients with CD. Despite this, NCGS does present with gastrointestinal (GI) and extra-intestinal symptoms similar to those of CD.

Wheat Allergies

Wheat is frequently implicated in food allergies, especially in infants and children. The incidence of WA is not known, although up to 4% of adults and 6% of children are estimated to have food allergies. In WA, there is an IgE antibody–mediated reaction to one or more of the wheat proteins (albumin, gliadin, globulin, gluten) that occurs within minutes to hours after exposure to the offending food. Many children with IgE-mediated allergies may “outgrow” them with time.12

Continue for the clinical presentation of GS >>

CLINICAL PRESENTATION OF GS

Although CD is a disorder associated with the GI system, the “classic” GI symptoms of bloating, flatulence, diarrhea, and/or constipation are often absent (silent CD), especially in older individuals. It is for this reason that the diagnosis of CD is easily missed.

Delaying diagnosis can have serious health consequences, as CD is associated with significant morbidities, such as malnutrition (worse in children), iron-deficiency anemia, neuropsychiatric aberrations (depression, anxiety, attention-deficit, and cerebral ataxia), osteoporosis, lymphoma, and death (see Table 1).4,13 CD may also present with dermatitis herpetiformis, a chronic vesicular rash, seen most often in adult males.

The role of gluten in the development of autism spectrum disorders or schizophrenia, though not proven, remains hotly debated, especially as close biochemical links are now recognized between the gut and the brain. It is clear, however, that gluten intake in severely gluten-sensitive individuals can directly affect mood and brain function. Most CD-associated morbidities will resolve after one year of complete gluten avoidance.1,13

Prominent symptoms of NCGS occur soon after gluten ingestion and disappear within days to weeks of gluten avoidance. The classic NCGS presentation combines IBS-like symptoms, such as abdominal cramps, bloating, diarrhea, and constipation, with systemic manifestations that include “brain fog,” fatigue, headache, joint and muscle pain, peripheral numbness, skin rash, aphthous stomatitis, anemia, and depression or anxiety. As with CD, GI symptoms usually predominate in children and abate with gluten avoidance.14,15

Allergic reactions to wheat will present within minutes to two hours of wheat exposure and may manifest with pruritic rash, hives, swelling of the lips or tongue, rhinitis, abdominal cramps, vomiting, diarrhea, constipation, and/or anaphylaxis. Subtle reactions may make diagnosis difficult.12

DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES FOR GS

The effectiveness of diagnostic testing for CD has been well established. Testing for antitissue transglutaminase antibodies (tTG-IgA) is the preferred laboratory test for CD, with a sensitivity of 93%, specificity of 98%, and few false-negative results. The endomysial antibody (EMA-IgA) test, though highly specific for CD, lacks the sensitivity of tTG-IgA. Newer antibody tests, such as deamidated gliadin peptide IgA and IgG, have not proven superior in detecting CD. Genetic testing for HLA-DQ2 and HLA-DQ8 may also be performed, but many people carry the gene without ever developing CD.13

To improve the reliability of CD antibody tests, the patient should have consumed gluten regularly for at least one month prior to testing. If the patient has been on a gluten-free diet for several weeks, then a gluten challenge should be done: The patient would be instructed to consume at least 3 g/d of gluten (two slices of bread) for a minimum of two weeks (versus eight weeks in previous protocols), after which the celiac antibody tests would be repeated.16

If these antibody test results are negative but the suspicion for CD remains high, an endoscopy with a duodenal biopsy should be performed. The appearance of villous atrophy would confirm the diagnosis of CD.1,13,16

Unlike CD, there are currently no reliable diagnostic tests for NCGS, although some researchers suggest testing for IgG antigliadin antibodies (AGA); NCGS is currently a diagnosis of exclusion.7 In NCGS, celiac antibodies will be negative and the duodenal biopsy will demonstrate only mild inflammation without the mucosal atrophy of CD. As with CD, patients affected by NCGS will also test negative for the wheat allergy IgE response.

Another option is a gluten challenge. The patient is instructed to follow a gluten-free diet for six weeks and monitor for NCGS symptoms. If symptoms abate, a gluten-containing diet is then reintroduced and the patient is evaluated for the reemergence of NCGS symptoms. If symptoms are not reduced with a gluten-free diet, NCGS may be excluded. Newer GS laboratory tests will emerge that can assay more forms of gliadin antibodies, possibly aiding in NCGS diagnosis.4,14

To make a diagnosis of WA, skin prick tests and allergen-specific IgE testing are used, along with a medical history, clinical presentation, and possibly a food challenge.

Continue for management of GS >>

MANAGEMENT OF GS

The hallmark treatment for GS, regardless of its causative factor, is a strict gluten-free diet (GFD). For patients with CD, a 100% GFD is recommended for life. It is not yet known whether this lifelong duration is necessary for those with NCGS and WA, or if there is a safe threshold in these patients for gluten consumption. It is helpful for patients to keep a food diary, noting what they eat and how that affects the appearance or attenuation of symptoms.

Transitioning to a gluten-free lifestyle can be confusing, frustrating, and expensive for patients. Removing gluten from the diet is also challenging, as wheat is the predominant grain consumed in this country. Barley and rye (less so oats) also contain gluten, leaving limited alternatives, like amaranth, corn, quinoa, rice, and tapioca. Unlike CD and NCGS, WA requires only elimination of wheat-containing products; thus, it may not be necessary for affected patients to avoid barley and rye.1,4

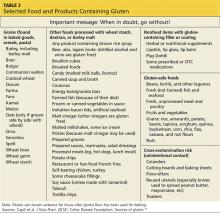

Extensive patient education is important for success. Referral to a knowledgeable nutritionist is ideal but not always practical. Lists of foods to avoid on a gluten-free diet are readily available, but important points should be stressed, including how to read food labels. For example, the term wheat-free does not mean gluten-free (see Table 2).1,17 As of August 2014, the food industry, by law, can only claim a product is “gluten-free” if it contains no more than 20 parts per million (ppm) of gluten.1

Due to malabsorption issues, it is recommended that patients with CD be monitored for micronutrient deficiencies (ie, iron, B1, B6, B12, and zinc), and osteopenia/osteoporosis (dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry [DEXA] at the time of diagnosis) and be offered fertility counseling. What patients with GS need most of all are informed, caring providers to help guide them through diagnosis and treatment.6,13

Continue for the conclusion >>

CONCLUSION

Gluten-free diets are increasing in popularity, and many people who do not have CD claim improved health and vitality when they avoid gluten. Much is known about the incidence and pathogenesis of the gluten-associated disorders of CD and WA. Far less is known about the controversial disorder of NCGS. The symptoms and morbidities associated with NCGS have been well documented and present a curious mix of CD and IBS, yet neither condition fully accounts for the pathogenesis of NCGS. While CD is linked to more serious morbidities (including death if the disease is not readily diagnosed), NCGS and WA do produce significant manifestations and risks.

Research into NCGS remains limited and conflicting, and biomarkers for the disorder are not yet known. Unsupported or not, many patients attribute mood disorders, pain, and chronic ills to gluten intake and seek input from their health care providers. Rather than dismiss their claims, clinicians can provide pertinent instructions on a gluten-free lifestyle and healthy diet, and encourage the use of food diaries to document food-symptom associations. Gluten sensitivities are not benign and “going gluten-free” may be of great benefit for many patients with GS. That’s a fact.

REFERENCES

1. Capili B, Chang M, Anastasi JK. Nonceliac gluten sensitivity—is it really the gluten? J Nurs Pract. 2014;10(9):666-673.

2. Davis W. Wheat Belly: Lose the Wheat, Lose the Weight, and Find Your Path Back to Health. Emmaus, PA: Rodale Books; 2011.

3. Perlmutter D. Grain Brain: The Surprising Truth about Wheat, Carbs, and Sugar—Your Brain’s Silent Killers. New York, NY: Little, Brown and Company; 2013.

4. Brown AC. Gluten sensitivity: problems of an emerging condition separate from celiac disease. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;6(1): 43-55.

5. Sapone A, Bai JC, Ciacci C, et al. Spectrum of gluten-related disorders: consensus on new nomenclature and classification. BMC Med. 2012 Feb 7;10:13.

6. Rubio-Tapia A, Hill ID, Kelly CP, et al; American College of Gastroenterology. ACG clinical guidelines: diagnosis and management of celiac disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108(5):656-676.

7. Mansueto P, Seidita A, D’Alcamo A, Carroccio A. Non-celiac gluten sensitivity: literature review. J Am Coll Nutr. 2014;33(1):39-54.

8. Boettcher E, Crowe SE. Dietary proteins and functional gastrointestinal disorders. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108(5):728-736.

9. Fasano A, Sapone A, Zevallos V, Schuppan D. Nonceliac gluten sensitivity. Gastroenterology. 2015;148(6):1195-1204.

10. Catassi C, Bai JC, Bonaz B, Boouma G. Non-celiac gluten sensitivity: the new frontier of gluten related disorders. Nutrients. 2013;5(10):3839-3853.

11. Biesiekierski JR, Peters SL, Newnham ED, et al. No effects of gluten in patients with self-reported non-celiac gluten sensitivity after dietary reduction of fermentable, poorly absorbed, short-chain carbohydrates. Gastroenterology. 2013;145(2):320-328.

12. Guandalini S, Newland C. Differentiating food allergies from food intolerances. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2011;13(5):426-434.

13. Scanlon SA, Murray JA. Update on celiac disease—etiology, differential diagnosis, drug targets, and management devices. Clin Exp Gastroenterol. 2011;4:297-311.

14. Catassi C, Elli L, Bonaz B, et al. Diagnosis of non-celiac gluten sensitivity (NCGS): the Salerno Experts’ Criteria. Nutrients. 2015;7(6):4966-4977.

15. Peters SL, Biesiekierski JR, Yelland GW,et al. Randomised clinical trial: gluten may cause depression in subjects with non-coeliac gluten sensitivity—an exploratory clinical study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014:39(10): 1104–1112.

16. Leffler D, Schuppen D, Pallav K, et al. Kinetics of the histological, serological and symptomatic responses to gluten challenge in adults with coeliac disease. Gut. 2013;62(7):996-1004.

17. Celiac Disease Foundation. Sources of gluten (2015). https://celiac.org/live-gluten-free/glutenfreediet/sources-of-gluten. Accessed November 24, 2015.

IN THIS ARTICLE

• So what is gluten?

• Selected symptoms of celiac disease

• Selected foods and products containing gluten

Gluten has become a dietary pariah (see “So What Is Gluten?"). The American public’s enthusiasm for a gluten-free diet has spurred a gluten-free food industry that has grown, on average, 34% per year since 2009, with annual sales predicted to reach an impressive $15.5 billion by 2016.1 This trend coincides with the national media’s intense focus on gluten sensitivity (GS), as well as best-selling books such as Wheat Belly and Grain Brain.2,3

Gluten-free food products, once relegated to boutique food shops and limited shelf space, now fill sections in large grocery and drugstore chains. Many restaurants have added gluten-free items to their menus (although gluten-free Big Macs have been available in Finland for more than 20 years).4 Only celiac disease (CD), which affects approximately 1% of the American population, requires strict gluten avoidance; yet more than 30% of US adults report having reduced their gluten intake, most claiming they did so to promote a “healthier” diet or support weight loss.1

PREVALENCE AND PATHOLOGY OF GS DISORDERS

Gluten sensitivity, once used to denote CD alone, now includes a group of gluten-intolerant conditions unrelated to CD—primarily nonceliac gluten sensitivity (NCGS) and wheat allergy (WA)—although the nomenclature is likely to change. While these disorders differ in underlying pathogenesis, each demonstrates a resolution of symptoms when the patient is placed on a gluten-free diet. Of these GS disorders, only NCGS lacks clarity with regard to incidence, diagnosis, and pathology.5

Celiac Disease

Celiac disease is an autoimmune, T-cell–activated disease that manifests in genetically susceptible individuals (with gene variants HLA-DQ2 and HLA-DQ8); it can occur at any age. The incidence of CD in the US has increased from 1 in 500 in 1974 to a current estimate of 1 in 100, although many with CD are believed to be undiagnosed.4,6

CD is the only autoimmune disease for which a trigger is known: gluten. Suspicion for CD should be heightened if the patient or a family member has a history of autoimmune disease. Nearly one-quarter of patients with CD will develop an autoimmune thyroid disorder.7

In CD, a significant enteropathy occurs in response to gluten intake, characterized by inflammation of the proximal small intestine. Individuals with CD produce tissue transglutaminase (tTG) or transglutaminase 2 (TG2) autoantibodies, resulting in gluten-specific CD4+ Th1 T-cell activation and an immune response that causes an upregulation of zonulin.8 Zonulin, a protein that modulates the permeability of the intestinal mucosal wall, is believed to play a role in “leaky gut syndrome” and autoimmune disease. The upregulation of zonulin in CD creates a disruption of the intestinal mucosal lining, causing villous mucosal atrophy and impairment of intestinal permeability and absorption.9

Nonceliac Gluten Sensitivity

NCGS is a poorly understood condition first described in the 1980s and recently “rediscovered” as a gluten-related disorder.10 Its actual prevalence is unknown because of unclear diagnostic criteria but is likely much higher than that of CD.1,4 Unlike CD, there does not appear to be a genetic predisposition for NCGS, nor is it believed to be an autoimmune disorder. However, research does suggest that NCGS may increase the risk for autoimmune diseases, such as Hashimoto thyroiditis. NCGS can occur at any age but appears more commonly in adults than children, and in women than men.4

A small but meticulous 2013 study raised doubt about NCGS as a specific gluten-related disorder.11 The results suggested that NCGS should be viewed as a variant of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), not triggered by gluten but by poorly absorbed carbohydrates found in wheat known as fructans and galactans, and perhaps by other foods containing fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides, and polyols (FODMAPS). It is believed those with diarrhea-prone IBS are particularly sensitive to gluten.11 As a result, ardent claims of NCGS and improved health with gluten-free diets in those without CD are often discounted.

More recent research findings refute this conjecture, suggesting that NCGS is likely a reaction to other proteins within the gluten family, such as beta-, gamma-, or omega-gliadin, glutenin, wheat germ agglutinin, gluteomorphin, and deamidated gliadin. Development of GS is believed to be triggered by such factors as intestinal infections, altered microbiota, or food additives.4

In any event, the pathogenesis of NCGS remains unclear, and it does not present with the diagnostic antibodies or inflammatory enteropathy seen in patients with CD. Despite this, NCGS does present with gastrointestinal (GI) and extra-intestinal symptoms similar to those of CD.

Wheat Allergies

Wheat is frequently implicated in food allergies, especially in infants and children. The incidence of WA is not known, although up to 4% of adults and 6% of children are estimated to have food allergies. In WA, there is an IgE antibody–mediated reaction to one or more of the wheat proteins (albumin, gliadin, globulin, gluten) that occurs within minutes to hours after exposure to the offending food. Many children with IgE-mediated allergies may “outgrow” them with time.12

Continue for the clinical presentation of GS >>

CLINICAL PRESENTATION OF GS

Although CD is a disorder associated with the GI system, the “classic” GI symptoms of bloating, flatulence, diarrhea, and/or constipation are often absent (silent CD), especially in older individuals. It is for this reason that the diagnosis of CD is easily missed.

Delaying diagnosis can have serious health consequences, as CD is associated with significant morbidities, such as malnutrition (worse in children), iron-deficiency anemia, neuropsychiatric aberrations (depression, anxiety, attention-deficit, and cerebral ataxia), osteoporosis, lymphoma, and death (see Table 1).4,13 CD may also present with dermatitis herpetiformis, a chronic vesicular rash, seen most often in adult males.

The role of gluten in the development of autism spectrum disorders or schizophrenia, though not proven, remains hotly debated, especially as close biochemical links are now recognized between the gut and the brain. It is clear, however, that gluten intake in severely gluten-sensitive individuals can directly affect mood and brain function. Most CD-associated morbidities will resolve after one year of complete gluten avoidance.1,13

Prominent symptoms of NCGS occur soon after gluten ingestion and disappear within days to weeks of gluten avoidance. The classic NCGS presentation combines IBS-like symptoms, such as abdominal cramps, bloating, diarrhea, and constipation, with systemic manifestations that include “brain fog,” fatigue, headache, joint and muscle pain, peripheral numbness, skin rash, aphthous stomatitis, anemia, and depression or anxiety. As with CD, GI symptoms usually predominate in children and abate with gluten avoidance.14,15

Allergic reactions to wheat will present within minutes to two hours of wheat exposure and may manifest with pruritic rash, hives, swelling of the lips or tongue, rhinitis, abdominal cramps, vomiting, diarrhea, constipation, and/or anaphylaxis. Subtle reactions may make diagnosis difficult.12

DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES FOR GS

The effectiveness of diagnostic testing for CD has been well established. Testing for antitissue transglutaminase antibodies (tTG-IgA) is the preferred laboratory test for CD, with a sensitivity of 93%, specificity of 98%, and few false-negative results. The endomysial antibody (EMA-IgA) test, though highly specific for CD, lacks the sensitivity of tTG-IgA. Newer antibody tests, such as deamidated gliadin peptide IgA and IgG, have not proven superior in detecting CD. Genetic testing for HLA-DQ2 and HLA-DQ8 may also be performed, but many people carry the gene without ever developing CD.13

To improve the reliability of CD antibody tests, the patient should have consumed gluten regularly for at least one month prior to testing. If the patient has been on a gluten-free diet for several weeks, then a gluten challenge should be done: The patient would be instructed to consume at least 3 g/d of gluten (two slices of bread) for a minimum of two weeks (versus eight weeks in previous protocols), after which the celiac antibody tests would be repeated.16

If these antibody test results are negative but the suspicion for CD remains high, an endoscopy with a duodenal biopsy should be performed. The appearance of villous atrophy would confirm the diagnosis of CD.1,13,16

Unlike CD, there are currently no reliable diagnostic tests for NCGS, although some researchers suggest testing for IgG antigliadin antibodies (AGA); NCGS is currently a diagnosis of exclusion.7 In NCGS, celiac antibodies will be negative and the duodenal biopsy will demonstrate only mild inflammation without the mucosal atrophy of CD. As with CD, patients affected by NCGS will also test negative for the wheat allergy IgE response.

Another option is a gluten challenge. The patient is instructed to follow a gluten-free diet for six weeks and monitor for NCGS symptoms. If symptoms abate, a gluten-containing diet is then reintroduced and the patient is evaluated for the reemergence of NCGS symptoms. If symptoms are not reduced with a gluten-free diet, NCGS may be excluded. Newer GS laboratory tests will emerge that can assay more forms of gliadin antibodies, possibly aiding in NCGS diagnosis.4,14

To make a diagnosis of WA, skin prick tests and allergen-specific IgE testing are used, along with a medical history, clinical presentation, and possibly a food challenge.

Continue for management of GS >>

MANAGEMENT OF GS

The hallmark treatment for GS, regardless of its causative factor, is a strict gluten-free diet (GFD). For patients with CD, a 100% GFD is recommended for life. It is not yet known whether this lifelong duration is necessary for those with NCGS and WA, or if there is a safe threshold in these patients for gluten consumption. It is helpful for patients to keep a food diary, noting what they eat and how that affects the appearance or attenuation of symptoms.

Transitioning to a gluten-free lifestyle can be confusing, frustrating, and expensive for patients. Removing gluten from the diet is also challenging, as wheat is the predominant grain consumed in this country. Barley and rye (less so oats) also contain gluten, leaving limited alternatives, like amaranth, corn, quinoa, rice, and tapioca. Unlike CD and NCGS, WA requires only elimination of wheat-containing products; thus, it may not be necessary for affected patients to avoid barley and rye.1,4

Extensive patient education is important for success. Referral to a knowledgeable nutritionist is ideal but not always practical. Lists of foods to avoid on a gluten-free diet are readily available, but important points should be stressed, including how to read food labels. For example, the term wheat-free does not mean gluten-free (see Table 2).1,17 As of August 2014, the food industry, by law, can only claim a product is “gluten-free” if it contains no more than 20 parts per million (ppm) of gluten.1

Due to malabsorption issues, it is recommended that patients with CD be monitored for micronutrient deficiencies (ie, iron, B1, B6, B12, and zinc), and osteopenia/osteoporosis (dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry [DEXA] at the time of diagnosis) and be offered fertility counseling. What patients with GS need most of all are informed, caring providers to help guide them through diagnosis and treatment.6,13

Continue for the conclusion >>

CONCLUSION

Gluten-free diets are increasing in popularity, and many people who do not have CD claim improved health and vitality when they avoid gluten. Much is known about the incidence and pathogenesis of the gluten-associated disorders of CD and WA. Far less is known about the controversial disorder of NCGS. The symptoms and morbidities associated with NCGS have been well documented and present a curious mix of CD and IBS, yet neither condition fully accounts for the pathogenesis of NCGS. While CD is linked to more serious morbidities (including death if the disease is not readily diagnosed), NCGS and WA do produce significant manifestations and risks.

Research into NCGS remains limited and conflicting, and biomarkers for the disorder are not yet known. Unsupported or not, many patients attribute mood disorders, pain, and chronic ills to gluten intake and seek input from their health care providers. Rather than dismiss their claims, clinicians can provide pertinent instructions on a gluten-free lifestyle and healthy diet, and encourage the use of food diaries to document food-symptom associations. Gluten sensitivities are not benign and “going gluten-free” may be of great benefit for many patients with GS. That’s a fact.

REFERENCES

1. Capili B, Chang M, Anastasi JK. Nonceliac gluten sensitivity—is it really the gluten? J Nurs Pract. 2014;10(9):666-673.

2. Davis W. Wheat Belly: Lose the Wheat, Lose the Weight, and Find Your Path Back to Health. Emmaus, PA: Rodale Books; 2011.

3. Perlmutter D. Grain Brain: The Surprising Truth about Wheat, Carbs, and Sugar—Your Brain’s Silent Killers. New York, NY: Little, Brown and Company; 2013.

4. Brown AC. Gluten sensitivity: problems of an emerging condition separate from celiac disease. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;6(1): 43-55.

5. Sapone A, Bai JC, Ciacci C, et al. Spectrum of gluten-related disorders: consensus on new nomenclature and classification. BMC Med. 2012 Feb 7;10:13.

6. Rubio-Tapia A, Hill ID, Kelly CP, et al; American College of Gastroenterology. ACG clinical guidelines: diagnosis and management of celiac disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108(5):656-676.

7. Mansueto P, Seidita A, D’Alcamo A, Carroccio A. Non-celiac gluten sensitivity: literature review. J Am Coll Nutr. 2014;33(1):39-54.

8. Boettcher E, Crowe SE. Dietary proteins and functional gastrointestinal disorders. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108(5):728-736.

9. Fasano A, Sapone A, Zevallos V, Schuppan D. Nonceliac gluten sensitivity. Gastroenterology. 2015;148(6):1195-1204.

10. Catassi C, Bai JC, Bonaz B, Boouma G. Non-celiac gluten sensitivity: the new frontier of gluten related disorders. Nutrients. 2013;5(10):3839-3853.

11. Biesiekierski JR, Peters SL, Newnham ED, et al. No effects of gluten in patients with self-reported non-celiac gluten sensitivity after dietary reduction of fermentable, poorly absorbed, short-chain carbohydrates. Gastroenterology. 2013;145(2):320-328.

12. Guandalini S, Newland C. Differentiating food allergies from food intolerances. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2011;13(5):426-434.

13. Scanlon SA, Murray JA. Update on celiac disease—etiology, differential diagnosis, drug targets, and management devices. Clin Exp Gastroenterol. 2011;4:297-311.

14. Catassi C, Elli L, Bonaz B, et al. Diagnosis of non-celiac gluten sensitivity (NCGS): the Salerno Experts’ Criteria. Nutrients. 2015;7(6):4966-4977.

15. Peters SL, Biesiekierski JR, Yelland GW,et al. Randomised clinical trial: gluten may cause depression in subjects with non-coeliac gluten sensitivity—an exploratory clinical study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014:39(10): 1104–1112.

16. Leffler D, Schuppen D, Pallav K, et al. Kinetics of the histological, serological and symptomatic responses to gluten challenge in adults with coeliac disease. Gut. 2013;62(7):996-1004.

17. Celiac Disease Foundation. Sources of gluten (2015). https://celiac.org/live-gluten-free/glutenfreediet/sources-of-gluten. Accessed November 24, 2015.

IN THIS ARTICLE

• So what is gluten?

• Selected symptoms of celiac disease

• Selected foods and products containing gluten

Gluten has become a dietary pariah (see “So What Is Gluten?"). The American public’s enthusiasm for a gluten-free diet has spurred a gluten-free food industry that has grown, on average, 34% per year since 2009, with annual sales predicted to reach an impressive $15.5 billion by 2016.1 This trend coincides with the national media’s intense focus on gluten sensitivity (GS), as well as best-selling books such as Wheat Belly and Grain Brain.2,3

Gluten-free food products, once relegated to boutique food shops and limited shelf space, now fill sections in large grocery and drugstore chains. Many restaurants have added gluten-free items to their menus (although gluten-free Big Macs have been available in Finland for more than 20 years).4 Only celiac disease (CD), which affects approximately 1% of the American population, requires strict gluten avoidance; yet more than 30% of US adults report having reduced their gluten intake, most claiming they did so to promote a “healthier” diet or support weight loss.1

PREVALENCE AND PATHOLOGY OF GS DISORDERS

Gluten sensitivity, once used to denote CD alone, now includes a group of gluten-intolerant conditions unrelated to CD—primarily nonceliac gluten sensitivity (NCGS) and wheat allergy (WA)—although the nomenclature is likely to change. While these disorders differ in underlying pathogenesis, each demonstrates a resolution of symptoms when the patient is placed on a gluten-free diet. Of these GS disorders, only NCGS lacks clarity with regard to incidence, diagnosis, and pathology.5

Celiac Disease

Celiac disease is an autoimmune, T-cell–activated disease that manifests in genetically susceptible individuals (with gene variants HLA-DQ2 and HLA-DQ8); it can occur at any age. The incidence of CD in the US has increased from 1 in 500 in 1974 to a current estimate of 1 in 100, although many with CD are believed to be undiagnosed.4,6

CD is the only autoimmune disease for which a trigger is known: gluten. Suspicion for CD should be heightened if the patient or a family member has a history of autoimmune disease. Nearly one-quarter of patients with CD will develop an autoimmune thyroid disorder.7

In CD, a significant enteropathy occurs in response to gluten intake, characterized by inflammation of the proximal small intestine. Individuals with CD produce tissue transglutaminase (tTG) or transglutaminase 2 (TG2) autoantibodies, resulting in gluten-specific CD4+ Th1 T-cell activation and an immune response that causes an upregulation of zonulin.8 Zonulin, a protein that modulates the permeability of the intestinal mucosal wall, is believed to play a role in “leaky gut syndrome” and autoimmune disease. The upregulation of zonulin in CD creates a disruption of the intestinal mucosal lining, causing villous mucosal atrophy and impairment of intestinal permeability and absorption.9

Nonceliac Gluten Sensitivity

NCGS is a poorly understood condition first described in the 1980s and recently “rediscovered” as a gluten-related disorder.10 Its actual prevalence is unknown because of unclear diagnostic criteria but is likely much higher than that of CD.1,4 Unlike CD, there does not appear to be a genetic predisposition for NCGS, nor is it believed to be an autoimmune disorder. However, research does suggest that NCGS may increase the risk for autoimmune diseases, such as Hashimoto thyroiditis. NCGS can occur at any age but appears more commonly in adults than children, and in women than men.4

A small but meticulous 2013 study raised doubt about NCGS as a specific gluten-related disorder.11 The results suggested that NCGS should be viewed as a variant of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), not triggered by gluten but by poorly absorbed carbohydrates found in wheat known as fructans and galactans, and perhaps by other foods containing fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides, and polyols (FODMAPS). It is believed those with diarrhea-prone IBS are particularly sensitive to gluten.11 As a result, ardent claims of NCGS and improved health with gluten-free diets in those without CD are often discounted.

More recent research findings refute this conjecture, suggesting that NCGS is likely a reaction to other proteins within the gluten family, such as beta-, gamma-, or omega-gliadin, glutenin, wheat germ agglutinin, gluteomorphin, and deamidated gliadin. Development of GS is believed to be triggered by such factors as intestinal infections, altered microbiota, or food additives.4

In any event, the pathogenesis of NCGS remains unclear, and it does not present with the diagnostic antibodies or inflammatory enteropathy seen in patients with CD. Despite this, NCGS does present with gastrointestinal (GI) and extra-intestinal symptoms similar to those of CD.

Wheat Allergies

Wheat is frequently implicated in food allergies, especially in infants and children. The incidence of WA is not known, although up to 4% of adults and 6% of children are estimated to have food allergies. In WA, there is an IgE antibody–mediated reaction to one or more of the wheat proteins (albumin, gliadin, globulin, gluten) that occurs within minutes to hours after exposure to the offending food. Many children with IgE-mediated allergies may “outgrow” them with time.12

Continue for the clinical presentation of GS >>

CLINICAL PRESENTATION OF GS

Although CD is a disorder associated with the GI system, the “classic” GI symptoms of bloating, flatulence, diarrhea, and/or constipation are often absent (silent CD), especially in older individuals. It is for this reason that the diagnosis of CD is easily missed.

Delaying diagnosis can have serious health consequences, as CD is associated with significant morbidities, such as malnutrition (worse in children), iron-deficiency anemia, neuropsychiatric aberrations (depression, anxiety, attention-deficit, and cerebral ataxia), osteoporosis, lymphoma, and death (see Table 1).4,13 CD may also present with dermatitis herpetiformis, a chronic vesicular rash, seen most often in adult males.

The role of gluten in the development of autism spectrum disorders or schizophrenia, though not proven, remains hotly debated, especially as close biochemical links are now recognized between the gut and the brain. It is clear, however, that gluten intake in severely gluten-sensitive individuals can directly affect mood and brain function. Most CD-associated morbidities will resolve after one year of complete gluten avoidance.1,13

Prominent symptoms of NCGS occur soon after gluten ingestion and disappear within days to weeks of gluten avoidance. The classic NCGS presentation combines IBS-like symptoms, such as abdominal cramps, bloating, diarrhea, and constipation, with systemic manifestations that include “brain fog,” fatigue, headache, joint and muscle pain, peripheral numbness, skin rash, aphthous stomatitis, anemia, and depression or anxiety. As with CD, GI symptoms usually predominate in children and abate with gluten avoidance.14,15

Allergic reactions to wheat will present within minutes to two hours of wheat exposure and may manifest with pruritic rash, hives, swelling of the lips or tongue, rhinitis, abdominal cramps, vomiting, diarrhea, constipation, and/or anaphylaxis. Subtle reactions may make diagnosis difficult.12

DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES FOR GS

The effectiveness of diagnostic testing for CD has been well established. Testing for antitissue transglutaminase antibodies (tTG-IgA) is the preferred laboratory test for CD, with a sensitivity of 93%, specificity of 98%, and few false-negative results. The endomysial antibody (EMA-IgA) test, though highly specific for CD, lacks the sensitivity of tTG-IgA. Newer antibody tests, such as deamidated gliadin peptide IgA and IgG, have not proven superior in detecting CD. Genetic testing for HLA-DQ2 and HLA-DQ8 may also be performed, but many people carry the gene without ever developing CD.13

To improve the reliability of CD antibody tests, the patient should have consumed gluten regularly for at least one month prior to testing. If the patient has been on a gluten-free diet for several weeks, then a gluten challenge should be done: The patient would be instructed to consume at least 3 g/d of gluten (two slices of bread) for a minimum of two weeks (versus eight weeks in previous protocols), after which the celiac antibody tests would be repeated.16

If these antibody test results are negative but the suspicion for CD remains high, an endoscopy with a duodenal biopsy should be performed. The appearance of villous atrophy would confirm the diagnosis of CD.1,13,16

Unlike CD, there are currently no reliable diagnostic tests for NCGS, although some researchers suggest testing for IgG antigliadin antibodies (AGA); NCGS is currently a diagnosis of exclusion.7 In NCGS, celiac antibodies will be negative and the duodenal biopsy will demonstrate only mild inflammation without the mucosal atrophy of CD. As with CD, patients affected by NCGS will also test negative for the wheat allergy IgE response.

Another option is a gluten challenge. The patient is instructed to follow a gluten-free diet for six weeks and monitor for NCGS symptoms. If symptoms abate, a gluten-containing diet is then reintroduced and the patient is evaluated for the reemergence of NCGS symptoms. If symptoms are not reduced with a gluten-free diet, NCGS may be excluded. Newer GS laboratory tests will emerge that can assay more forms of gliadin antibodies, possibly aiding in NCGS diagnosis.4,14

To make a diagnosis of WA, skin prick tests and allergen-specific IgE testing are used, along with a medical history, clinical presentation, and possibly a food challenge.

Continue for management of GS >>

MANAGEMENT OF GS

The hallmark treatment for GS, regardless of its causative factor, is a strict gluten-free diet (GFD). For patients with CD, a 100% GFD is recommended for life. It is not yet known whether this lifelong duration is necessary for those with NCGS and WA, or if there is a safe threshold in these patients for gluten consumption. It is helpful for patients to keep a food diary, noting what they eat and how that affects the appearance or attenuation of symptoms.

Transitioning to a gluten-free lifestyle can be confusing, frustrating, and expensive for patients. Removing gluten from the diet is also challenging, as wheat is the predominant grain consumed in this country. Barley and rye (less so oats) also contain gluten, leaving limited alternatives, like amaranth, corn, quinoa, rice, and tapioca. Unlike CD and NCGS, WA requires only elimination of wheat-containing products; thus, it may not be necessary for affected patients to avoid barley and rye.1,4

Extensive patient education is important for success. Referral to a knowledgeable nutritionist is ideal but not always practical. Lists of foods to avoid on a gluten-free diet are readily available, but important points should be stressed, including how to read food labels. For example, the term wheat-free does not mean gluten-free (see Table 2).1,17 As of August 2014, the food industry, by law, can only claim a product is “gluten-free” if it contains no more than 20 parts per million (ppm) of gluten.1

Due to malabsorption issues, it is recommended that patients with CD be monitored for micronutrient deficiencies (ie, iron, B1, B6, B12, and zinc), and osteopenia/osteoporosis (dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry [DEXA] at the time of diagnosis) and be offered fertility counseling. What patients with GS need most of all are informed, caring providers to help guide them through diagnosis and treatment.6,13

Continue for the conclusion >>

CONCLUSION

Gluten-free diets are increasing in popularity, and many people who do not have CD claim improved health and vitality when they avoid gluten. Much is known about the incidence and pathogenesis of the gluten-associated disorders of CD and WA. Far less is known about the controversial disorder of NCGS. The symptoms and morbidities associated with NCGS have been well documented and present a curious mix of CD and IBS, yet neither condition fully accounts for the pathogenesis of NCGS. While CD is linked to more serious morbidities (including death if the disease is not readily diagnosed), NCGS and WA do produce significant manifestations and risks.

Research into NCGS remains limited and conflicting, and biomarkers for the disorder are not yet known. Unsupported or not, many patients attribute mood disorders, pain, and chronic ills to gluten intake and seek input from their health care providers. Rather than dismiss their claims, clinicians can provide pertinent instructions on a gluten-free lifestyle and healthy diet, and encourage the use of food diaries to document food-symptom associations. Gluten sensitivities are not benign and “going gluten-free” may be of great benefit for many patients with GS. That’s a fact.

REFERENCES

1. Capili B, Chang M, Anastasi JK. Nonceliac gluten sensitivity—is it really the gluten? J Nurs Pract. 2014;10(9):666-673.

2. Davis W. Wheat Belly: Lose the Wheat, Lose the Weight, and Find Your Path Back to Health. Emmaus, PA: Rodale Books; 2011.

3. Perlmutter D. Grain Brain: The Surprising Truth about Wheat, Carbs, and Sugar—Your Brain’s Silent Killers. New York, NY: Little, Brown and Company; 2013.

4. Brown AC. Gluten sensitivity: problems of an emerging condition separate from celiac disease. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;6(1): 43-55.

5. Sapone A, Bai JC, Ciacci C, et al. Spectrum of gluten-related disorders: consensus on new nomenclature and classification. BMC Med. 2012 Feb 7;10:13.

6. Rubio-Tapia A, Hill ID, Kelly CP, et al; American College of Gastroenterology. ACG clinical guidelines: diagnosis and management of celiac disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108(5):656-676.

7. Mansueto P, Seidita A, D’Alcamo A, Carroccio A. Non-celiac gluten sensitivity: literature review. J Am Coll Nutr. 2014;33(1):39-54.

8. Boettcher E, Crowe SE. Dietary proteins and functional gastrointestinal disorders. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108(5):728-736.

9. Fasano A, Sapone A, Zevallos V, Schuppan D. Nonceliac gluten sensitivity. Gastroenterology. 2015;148(6):1195-1204.

10. Catassi C, Bai JC, Bonaz B, Boouma G. Non-celiac gluten sensitivity: the new frontier of gluten related disorders. Nutrients. 2013;5(10):3839-3853.

11. Biesiekierski JR, Peters SL, Newnham ED, et al. No effects of gluten in patients with self-reported non-celiac gluten sensitivity after dietary reduction of fermentable, poorly absorbed, short-chain carbohydrates. Gastroenterology. 2013;145(2):320-328.

12. Guandalini S, Newland C. Differentiating food allergies from food intolerances. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2011;13(5):426-434.

13. Scanlon SA, Murray JA. Update on celiac disease—etiology, differential diagnosis, drug targets, and management devices. Clin Exp Gastroenterol. 2011;4:297-311.

14. Catassi C, Elli L, Bonaz B, et al. Diagnosis of non-celiac gluten sensitivity (NCGS): the Salerno Experts’ Criteria. Nutrients. 2015;7(6):4966-4977.

15. Peters SL, Biesiekierski JR, Yelland GW,et al. Randomised clinical trial: gluten may cause depression in subjects with non-coeliac gluten sensitivity—an exploratory clinical study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014:39(10): 1104–1112.

16. Leffler D, Schuppen D, Pallav K, et al. Kinetics of the histological, serological and symptomatic responses to gluten challenge in adults with coeliac disease. Gut. 2013;62(7):996-1004.

17. Celiac Disease Foundation. Sources of gluten (2015). https://celiac.org/live-gluten-free/glutenfreediet/sources-of-gluten. Accessed November 24, 2015.