User login

Acute Hemorrhagic Edema of Infancy: Guide to Prevent Misdiagnosis

Acute hemorrhagic edema of infancy (AHEI) is an uncommon leukocytoclastic vasculitis affecting children aged 6 to 24 months; Henoch-Schönlein purpura (HSP) is the most common misdiagnosis. The 2 entities should be differentiated, as HSP may have renal and gastrointestinal (GI) comorbidities that need serial follow-up, whereas AHEI follows a benign course without systemic sequelae. Patient history and physical examination are the most important factors in differentiating the 2 diseases; histopathologic and direct immunofluorescence (DIF) analyses may lend further diagnostic confidence.

We report the case of a 10-month-old previously healthy boy who presented with acute rash, edema, and low-grade fever in the setting of recent diarrhea. We differentiate between AHEI and HSP to help prevent misdiagnosis by health care providers.

Case Report

A 10-month-old previously healthy boy presented to the emergency department (ED) for evaluation of a rash and swelling of 4 days’ duration. He had nonbloody diarrhea 1 week prior; soon after, he developed bilateral lower leg edema and rash. On evaluation in a different ED, he had a low-grade fever (rectal temperature, 38.0°C) but normal blood work, including complete blood cell count, basic metabolic panel, and coagulation studies. The patient was discharged to outpatient follow-up with his pediatrician who reported normal urinalysis.

Due to progression of the rash, the patient presented to our ED 3 days after his initial ED assessment. Dermatology was consulted. At the time of presentation, he was afebrile but with GI upset and fussiness. His parents denied additional symptoms or blood in urine or stool. Physical examination revealed a nontoxic-appearing infant with scattered palpable, annular, purpuric papules coalescing into plaques on both legs and feet (Figure 1), with sparse petechiae noted on the lower abdomen. The cheeks had scattered purpuric papules and plaques bilaterally, a few with a small central crust (Figure 2), and the right superior helix had a faint purpuric macule. The hands had a few pink edematous coalescing papules.

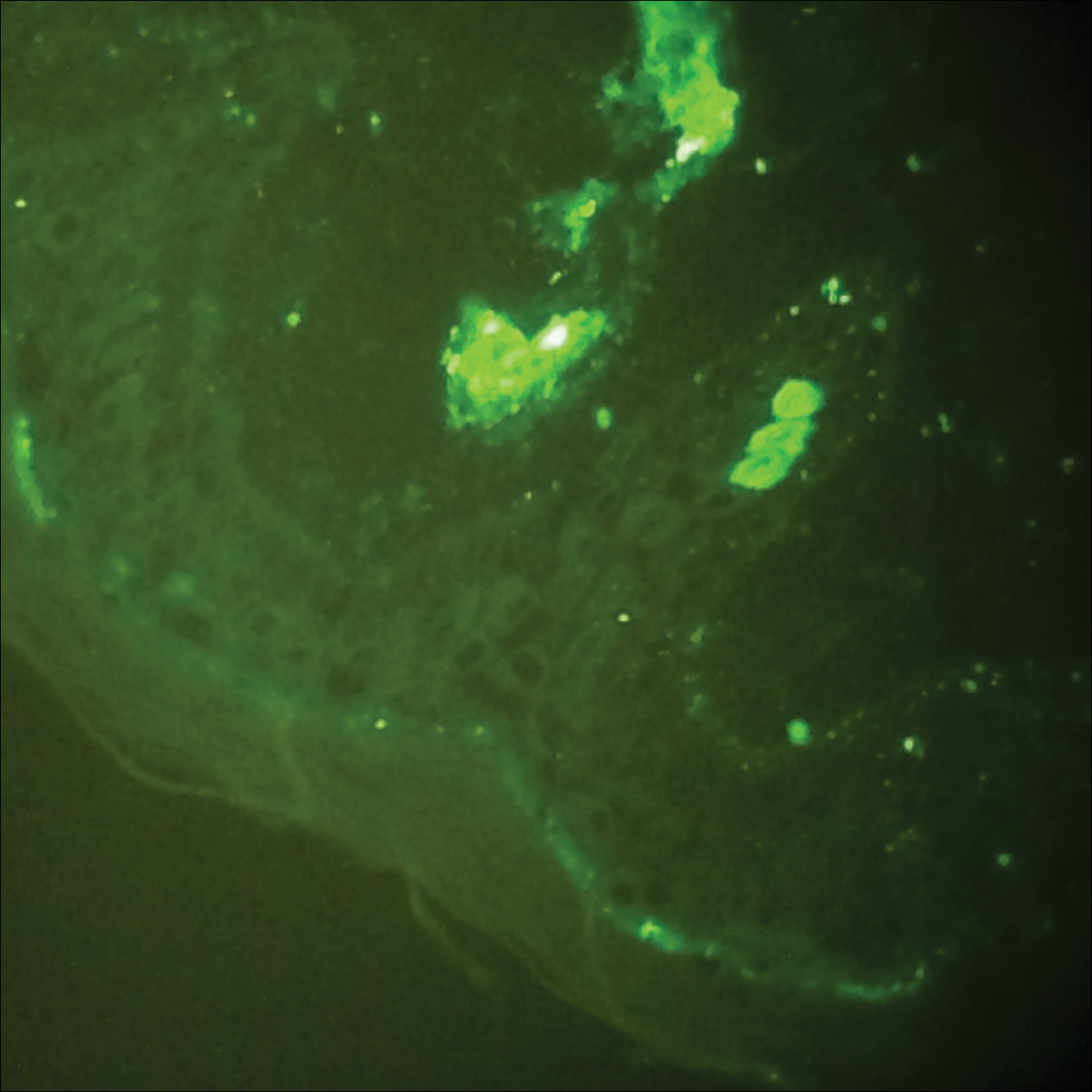

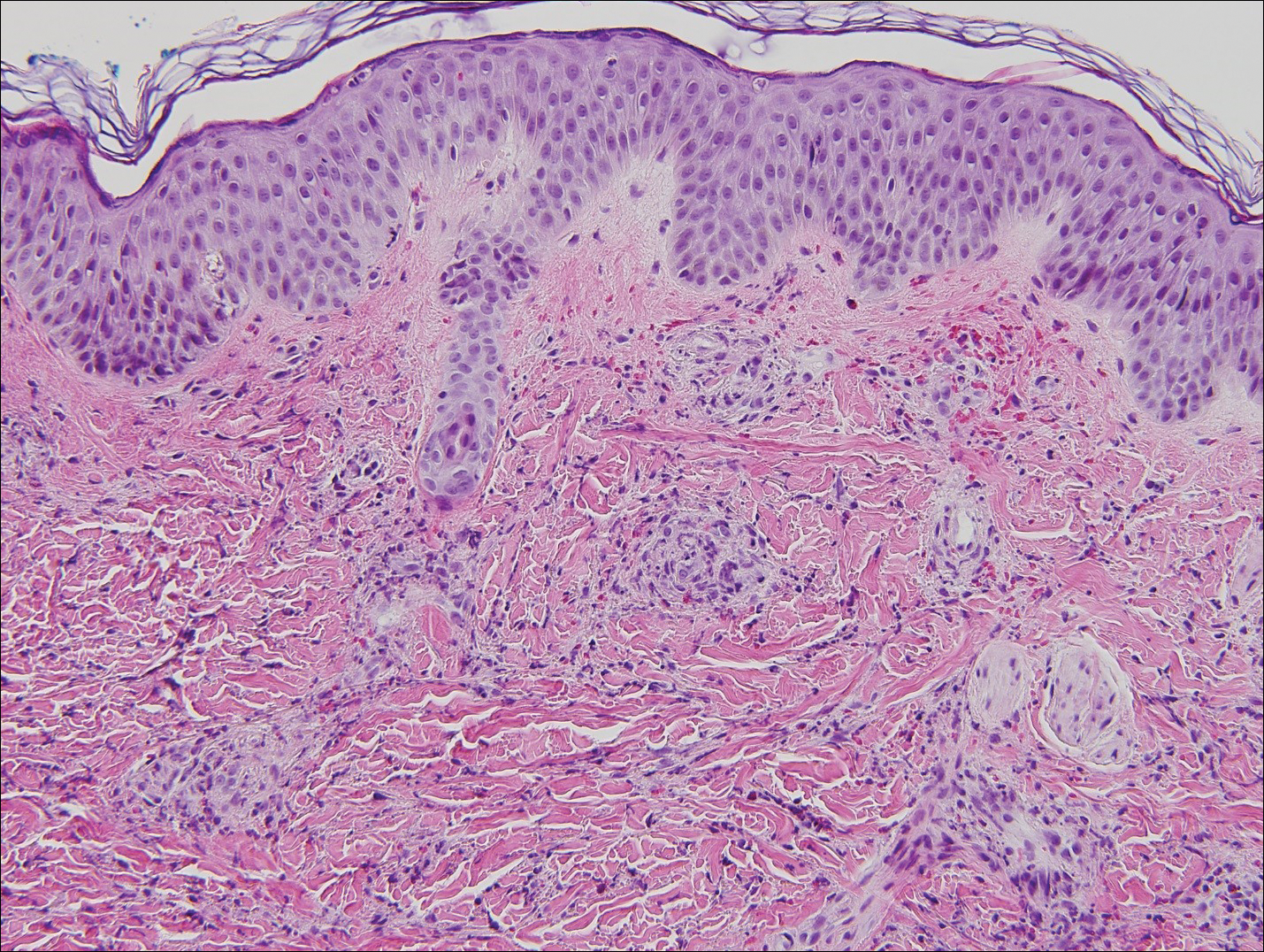

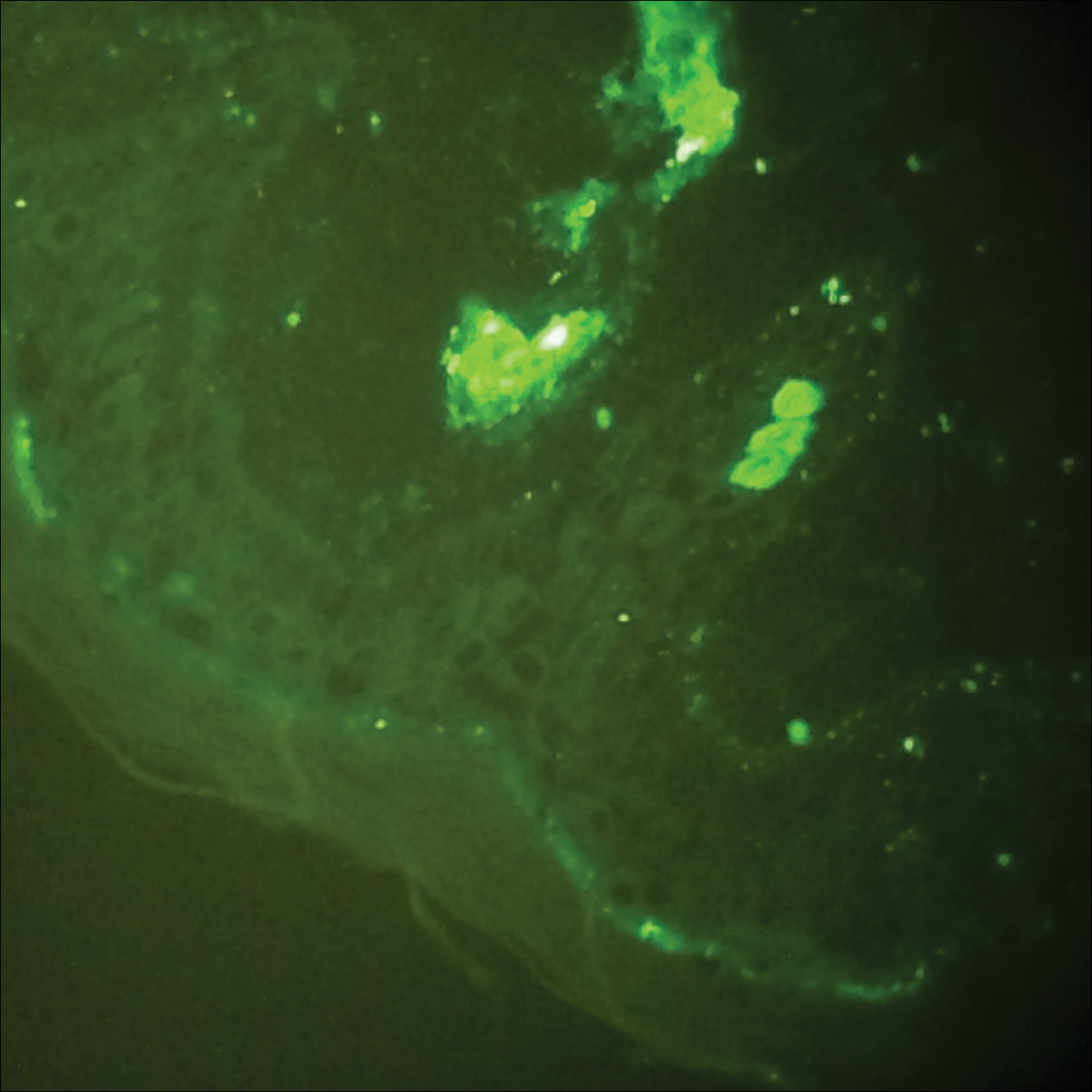

Histopathologic analyses with hematoxylin and eosin staining (Figure 3) and DIF (Figure 4) were performed from within a representative purpuric plaque on the right hip. Direct immunofluorescence was performed to evaluate for an IgA vasculitis versus an alternative type of vasculitis. The hematoxylin and eosin–stained specimen demonstrated a dermal perivascular infiltrate involving superficial and deep vessels with neutrophils, karyorrhexis, and erythrocyte extravasation. The endothelium was intact, with a mild suggestion of fibrinoid change of the blood vessel walls. Direct immunofluorescence revealed granular deposition of IgA, C3, and fibrinogen in multiple dermal blood vessels. Combined, the specimens were interpreted as evolving IgA-associated leukocytoclastic vasculitis.

The case was reviewed with our 2 department pediatric dermatologists; a diagnosis of AHEI was made based on the clinical and supportive histopathological presentations. The patient’s parents chose active treatment with a 2-week taper of oral prednisone because of the patient’s discomfort with edema. No GI or adverse renal sequelae, including findings on urinalysis, were reported at 1-month hospital follow-up with dermatology and pediatrics.

Comment

Incidence and Clinical Characteristics

Acute hemorrhagic edema of infancy is an uncommon leukocytoclastic vasculitis first described in the United States by Snow1 in 1913. Other names for the disorder include acute hemorrhagic edema of young children, cockade purpura and edema, Finkelstein disease, and Seidlmayer disease.2 Boys are affected more often than girls, with most children presenting at 6 to 24 months of age. Most affected children experience a prodrome of simple respiratory tract illness (most common), diarrhea (as in our case), or urinary tract infection.2 The exact pathophysiology behind AHEI is unknown, but it is thought to be an immune complex–mediated disease evidenced by the fact that infection, use of medication, or immunization precedes most cases.3,4

Diagnosis

Acute hemorrhagic edema of infancy is diagnosed clinically, with or without the support of skin biopsy. It should be differentiated from HSP because of renal and GI sequelae that HSP portends compared to the benign course of AHEI.2 Notably, some health care providers consider AHEI a benign variant of HSP.2,3

Characteristically, AHEI patients are nontoxic-appearing infants with a low-grade fever who develop relatively large (1–5 cm) targetoid purpuric lesions and indurated nonpitting edema of the extremities.2,5 Purpura in AHEI frequently occurs on the face, ears, and upper and lower extremities, whereas purpura in HSP most commonly presents on the buttocks and extensor legs with sparing of the face. Henoch-Schönlein purpura most often affects children aged 3 to 6 years compared to AHEI’s younger demographic (age <2 years).4,5 Clinically, HSP presents with palpable purpura and 1 or more of the following features: diffuse abdominal pain, arthritis/arthralgia, renal involvement, and skin or renal biopsy showing predominant IgA deposition.2,6

Both AHEI and HSP show leukocytoclastic vasculitis on histopathology.2-4,6,7 Positive perivascular IgA staining on DIF is strongly associated with HSP, but nearly one-quarter of AHEI cases also show this deposition pattern2,4,7; therefore, DIF alone cannot exclude a diagnosis of AHEI.

Differential Diagnosis

Alternative diagnoses to consider with AHEI include drug-induced vasculitis, erythema multiforme, HSP, Kawasaki disease, meningococcemia, nonaccidental skin bruising, Rocky Mountain spotted fever, septic vasculitis, and urticarial vasculitis (Table).2-4,6-8

Treatment

Acute hemorrhagic edema of infancy is self-limited, with only rare reports of extracutaneous involvement. Supportive treatment is indicated because spontaneous recovery without sequelae is expected within 21 days.2,3,6 If edema is symptomatic, as was the case with our patient, corticosteroids may shorten the disease course.3

Conclusion

Our case highlights the need to combine clinical history, physical examination, and histopathologic analysis to differentiate between AHEI and HSP, which is important for 2 reasons: (1) it helps with the decision to undertake active or observational treatment, and (2) it helps the clinician counsel the patient and guardians regarding potential associated renal and GI risks.

- Snow IM. Purpura, urticaria and angioneurotic edema of the hands and feet in a nursing baby. JAMA. 1913;61:18-19.

- Fiore E, Rizzi M, Ragazzi M, et al. Acute hemorrhagic edema of young children (cockade purpura and edema): a case series and systematic review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:684-695.

- Freitas P, Bygum A. Visual impairment caused by periorbital edema in an infant with acute hemorrhagic edema of infancy. Pediatr Dermatol. 2013;30:e132-e135.

- Legrain V, Lejean S, Taïeb A, et al. Infantile acute hemorrhagic edema of the skin: study of ten cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;24:17-22.

- Breda L, Franchini S, Marzetti V, et al. Escherichia coli urinary infection as a cause of acute hemorrhagic edema in infancy. Pediatr Dermatol. 2015;32:e309-e311.

- Ozen S, Ruperto N, Dillon MJ, et al. EULAR/PReS endorsed consensus criteria for the classification of childhood vasculitides. Ann Rheum Dis. 2006;65:936-941.

- Saraclar Y, Tinaztepe K, Adalioğlu G, et al. Acute hemorrhagic edema of infancy (AHEI)—a variant of Henoch-Schönlein purpura or a distinct clinical entity? J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1990;86:473-483.

- Shinkai K, Fox L. Cutaneous vasculitis. In: Bolognia J, Jorizzo J, Schaffer J, eds. Dermatology. 3rd ed. China: Elsevier Limited; 2012:385-410.

Acute hemorrhagic edema of infancy (AHEI) is an uncommon leukocytoclastic vasculitis affecting children aged 6 to 24 months; Henoch-Schönlein purpura (HSP) is the most common misdiagnosis. The 2 entities should be differentiated, as HSP may have renal and gastrointestinal (GI) comorbidities that need serial follow-up, whereas AHEI follows a benign course without systemic sequelae. Patient history and physical examination are the most important factors in differentiating the 2 diseases; histopathologic and direct immunofluorescence (DIF) analyses may lend further diagnostic confidence.

We report the case of a 10-month-old previously healthy boy who presented with acute rash, edema, and low-grade fever in the setting of recent diarrhea. We differentiate between AHEI and HSP to help prevent misdiagnosis by health care providers.

Case Report

A 10-month-old previously healthy boy presented to the emergency department (ED) for evaluation of a rash and swelling of 4 days’ duration. He had nonbloody diarrhea 1 week prior; soon after, he developed bilateral lower leg edema and rash. On evaluation in a different ED, he had a low-grade fever (rectal temperature, 38.0°C) but normal blood work, including complete blood cell count, basic metabolic panel, and coagulation studies. The patient was discharged to outpatient follow-up with his pediatrician who reported normal urinalysis.

Due to progression of the rash, the patient presented to our ED 3 days after his initial ED assessment. Dermatology was consulted. At the time of presentation, he was afebrile but with GI upset and fussiness. His parents denied additional symptoms or blood in urine or stool. Physical examination revealed a nontoxic-appearing infant with scattered palpable, annular, purpuric papules coalescing into plaques on both legs and feet (Figure 1), with sparse petechiae noted on the lower abdomen. The cheeks had scattered purpuric papules and plaques bilaterally, a few with a small central crust (Figure 2), and the right superior helix had a faint purpuric macule. The hands had a few pink edematous coalescing papules.

Histopathologic analyses with hematoxylin and eosin staining (Figure 3) and DIF (Figure 4) were performed from within a representative purpuric plaque on the right hip. Direct immunofluorescence was performed to evaluate for an IgA vasculitis versus an alternative type of vasculitis. The hematoxylin and eosin–stained specimen demonstrated a dermal perivascular infiltrate involving superficial and deep vessels with neutrophils, karyorrhexis, and erythrocyte extravasation. The endothelium was intact, with a mild suggestion of fibrinoid change of the blood vessel walls. Direct immunofluorescence revealed granular deposition of IgA, C3, and fibrinogen in multiple dermal blood vessels. Combined, the specimens were interpreted as evolving IgA-associated leukocytoclastic vasculitis.

The case was reviewed with our 2 department pediatric dermatologists; a diagnosis of AHEI was made based on the clinical and supportive histopathological presentations. The patient’s parents chose active treatment with a 2-week taper of oral prednisone because of the patient’s discomfort with edema. No GI or adverse renal sequelae, including findings on urinalysis, were reported at 1-month hospital follow-up with dermatology and pediatrics.

Comment

Incidence and Clinical Characteristics

Acute hemorrhagic edema of infancy is an uncommon leukocytoclastic vasculitis first described in the United States by Snow1 in 1913. Other names for the disorder include acute hemorrhagic edema of young children, cockade purpura and edema, Finkelstein disease, and Seidlmayer disease.2 Boys are affected more often than girls, with most children presenting at 6 to 24 months of age. Most affected children experience a prodrome of simple respiratory tract illness (most common), diarrhea (as in our case), or urinary tract infection.2 The exact pathophysiology behind AHEI is unknown, but it is thought to be an immune complex–mediated disease evidenced by the fact that infection, use of medication, or immunization precedes most cases.3,4

Diagnosis

Acute hemorrhagic edema of infancy is diagnosed clinically, with or without the support of skin biopsy. It should be differentiated from HSP because of renal and GI sequelae that HSP portends compared to the benign course of AHEI.2 Notably, some health care providers consider AHEI a benign variant of HSP.2,3

Characteristically, AHEI patients are nontoxic-appearing infants with a low-grade fever who develop relatively large (1–5 cm) targetoid purpuric lesions and indurated nonpitting edema of the extremities.2,5 Purpura in AHEI frequently occurs on the face, ears, and upper and lower extremities, whereas purpura in HSP most commonly presents on the buttocks and extensor legs with sparing of the face. Henoch-Schönlein purpura most often affects children aged 3 to 6 years compared to AHEI’s younger demographic (age <2 years).4,5 Clinically, HSP presents with palpable purpura and 1 or more of the following features: diffuse abdominal pain, arthritis/arthralgia, renal involvement, and skin or renal biopsy showing predominant IgA deposition.2,6

Both AHEI and HSP show leukocytoclastic vasculitis on histopathology.2-4,6,7 Positive perivascular IgA staining on DIF is strongly associated with HSP, but nearly one-quarter of AHEI cases also show this deposition pattern2,4,7; therefore, DIF alone cannot exclude a diagnosis of AHEI.

Differential Diagnosis

Alternative diagnoses to consider with AHEI include drug-induced vasculitis, erythema multiforme, HSP, Kawasaki disease, meningococcemia, nonaccidental skin bruising, Rocky Mountain spotted fever, septic vasculitis, and urticarial vasculitis (Table).2-4,6-8

Treatment

Acute hemorrhagic edema of infancy is self-limited, with only rare reports of extracutaneous involvement. Supportive treatment is indicated because spontaneous recovery without sequelae is expected within 21 days.2,3,6 If edema is symptomatic, as was the case with our patient, corticosteroids may shorten the disease course.3

Conclusion

Our case highlights the need to combine clinical history, physical examination, and histopathologic analysis to differentiate between AHEI and HSP, which is important for 2 reasons: (1) it helps with the decision to undertake active or observational treatment, and (2) it helps the clinician counsel the patient and guardians regarding potential associated renal and GI risks.

Acute hemorrhagic edema of infancy (AHEI) is an uncommon leukocytoclastic vasculitis affecting children aged 6 to 24 months; Henoch-Schönlein purpura (HSP) is the most common misdiagnosis. The 2 entities should be differentiated, as HSP may have renal and gastrointestinal (GI) comorbidities that need serial follow-up, whereas AHEI follows a benign course without systemic sequelae. Patient history and physical examination are the most important factors in differentiating the 2 diseases; histopathologic and direct immunofluorescence (DIF) analyses may lend further diagnostic confidence.

We report the case of a 10-month-old previously healthy boy who presented with acute rash, edema, and low-grade fever in the setting of recent diarrhea. We differentiate between AHEI and HSP to help prevent misdiagnosis by health care providers.

Case Report

A 10-month-old previously healthy boy presented to the emergency department (ED) for evaluation of a rash and swelling of 4 days’ duration. He had nonbloody diarrhea 1 week prior; soon after, he developed bilateral lower leg edema and rash. On evaluation in a different ED, he had a low-grade fever (rectal temperature, 38.0°C) but normal blood work, including complete blood cell count, basic metabolic panel, and coagulation studies. The patient was discharged to outpatient follow-up with his pediatrician who reported normal urinalysis.

Due to progression of the rash, the patient presented to our ED 3 days after his initial ED assessment. Dermatology was consulted. At the time of presentation, he was afebrile but with GI upset and fussiness. His parents denied additional symptoms or blood in urine or stool. Physical examination revealed a nontoxic-appearing infant with scattered palpable, annular, purpuric papules coalescing into plaques on both legs and feet (Figure 1), with sparse petechiae noted on the lower abdomen. The cheeks had scattered purpuric papules and plaques bilaterally, a few with a small central crust (Figure 2), and the right superior helix had a faint purpuric macule. The hands had a few pink edematous coalescing papules.

Histopathologic analyses with hematoxylin and eosin staining (Figure 3) and DIF (Figure 4) were performed from within a representative purpuric plaque on the right hip. Direct immunofluorescence was performed to evaluate for an IgA vasculitis versus an alternative type of vasculitis. The hematoxylin and eosin–stained specimen demonstrated a dermal perivascular infiltrate involving superficial and deep vessels with neutrophils, karyorrhexis, and erythrocyte extravasation. The endothelium was intact, with a mild suggestion of fibrinoid change of the blood vessel walls. Direct immunofluorescence revealed granular deposition of IgA, C3, and fibrinogen in multiple dermal blood vessels. Combined, the specimens were interpreted as evolving IgA-associated leukocytoclastic vasculitis.

The case was reviewed with our 2 department pediatric dermatologists; a diagnosis of AHEI was made based on the clinical and supportive histopathological presentations. The patient’s parents chose active treatment with a 2-week taper of oral prednisone because of the patient’s discomfort with edema. No GI or adverse renal sequelae, including findings on urinalysis, were reported at 1-month hospital follow-up with dermatology and pediatrics.

Comment

Incidence and Clinical Characteristics

Acute hemorrhagic edema of infancy is an uncommon leukocytoclastic vasculitis first described in the United States by Snow1 in 1913. Other names for the disorder include acute hemorrhagic edema of young children, cockade purpura and edema, Finkelstein disease, and Seidlmayer disease.2 Boys are affected more often than girls, with most children presenting at 6 to 24 months of age. Most affected children experience a prodrome of simple respiratory tract illness (most common), diarrhea (as in our case), or urinary tract infection.2 The exact pathophysiology behind AHEI is unknown, but it is thought to be an immune complex–mediated disease evidenced by the fact that infection, use of medication, or immunization precedes most cases.3,4

Diagnosis

Acute hemorrhagic edema of infancy is diagnosed clinically, with or without the support of skin biopsy. It should be differentiated from HSP because of renal and GI sequelae that HSP portends compared to the benign course of AHEI.2 Notably, some health care providers consider AHEI a benign variant of HSP.2,3

Characteristically, AHEI patients are nontoxic-appearing infants with a low-grade fever who develop relatively large (1–5 cm) targetoid purpuric lesions and indurated nonpitting edema of the extremities.2,5 Purpura in AHEI frequently occurs on the face, ears, and upper and lower extremities, whereas purpura in HSP most commonly presents on the buttocks and extensor legs with sparing of the face. Henoch-Schönlein purpura most often affects children aged 3 to 6 years compared to AHEI’s younger demographic (age <2 years).4,5 Clinically, HSP presents with palpable purpura and 1 or more of the following features: diffuse abdominal pain, arthritis/arthralgia, renal involvement, and skin or renal biopsy showing predominant IgA deposition.2,6

Both AHEI and HSP show leukocytoclastic vasculitis on histopathology.2-4,6,7 Positive perivascular IgA staining on DIF is strongly associated with HSP, but nearly one-quarter of AHEI cases also show this deposition pattern2,4,7; therefore, DIF alone cannot exclude a diagnosis of AHEI.

Differential Diagnosis

Alternative diagnoses to consider with AHEI include drug-induced vasculitis, erythema multiforme, HSP, Kawasaki disease, meningococcemia, nonaccidental skin bruising, Rocky Mountain spotted fever, septic vasculitis, and urticarial vasculitis (Table).2-4,6-8

Treatment

Acute hemorrhagic edema of infancy is self-limited, with only rare reports of extracutaneous involvement. Supportive treatment is indicated because spontaneous recovery without sequelae is expected within 21 days.2,3,6 If edema is symptomatic, as was the case with our patient, corticosteroids may shorten the disease course.3

Conclusion

Our case highlights the need to combine clinical history, physical examination, and histopathologic analysis to differentiate between AHEI and HSP, which is important for 2 reasons: (1) it helps with the decision to undertake active or observational treatment, and (2) it helps the clinician counsel the patient and guardians regarding potential associated renal and GI risks.

- Snow IM. Purpura, urticaria and angioneurotic edema of the hands and feet in a nursing baby. JAMA. 1913;61:18-19.

- Fiore E, Rizzi M, Ragazzi M, et al. Acute hemorrhagic edema of young children (cockade purpura and edema): a case series and systematic review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:684-695.

- Freitas P, Bygum A. Visual impairment caused by periorbital edema in an infant with acute hemorrhagic edema of infancy. Pediatr Dermatol. 2013;30:e132-e135.

- Legrain V, Lejean S, Taïeb A, et al. Infantile acute hemorrhagic edema of the skin: study of ten cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;24:17-22.

- Breda L, Franchini S, Marzetti V, et al. Escherichia coli urinary infection as a cause of acute hemorrhagic edema in infancy. Pediatr Dermatol. 2015;32:e309-e311.

- Ozen S, Ruperto N, Dillon MJ, et al. EULAR/PReS endorsed consensus criteria for the classification of childhood vasculitides. Ann Rheum Dis. 2006;65:936-941.

- Saraclar Y, Tinaztepe K, Adalioğlu G, et al. Acute hemorrhagic edema of infancy (AHEI)—a variant of Henoch-Schönlein purpura or a distinct clinical entity? J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1990;86:473-483.

- Shinkai K, Fox L. Cutaneous vasculitis. In: Bolognia J, Jorizzo J, Schaffer J, eds. Dermatology. 3rd ed. China: Elsevier Limited; 2012:385-410.

- Snow IM. Purpura, urticaria and angioneurotic edema of the hands and feet in a nursing baby. JAMA. 1913;61:18-19.

- Fiore E, Rizzi M, Ragazzi M, et al. Acute hemorrhagic edema of young children (cockade purpura and edema): a case series and systematic review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:684-695.

- Freitas P, Bygum A. Visual impairment caused by periorbital edema in an infant with acute hemorrhagic edema of infancy. Pediatr Dermatol. 2013;30:e132-e135.

- Legrain V, Lejean S, Taïeb A, et al. Infantile acute hemorrhagic edema of the skin: study of ten cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;24:17-22.

- Breda L, Franchini S, Marzetti V, et al. Escherichia coli urinary infection as a cause of acute hemorrhagic edema in infancy. Pediatr Dermatol. 2015;32:e309-e311.

- Ozen S, Ruperto N, Dillon MJ, et al. EULAR/PReS endorsed consensus criteria for the classification of childhood vasculitides. Ann Rheum Dis. 2006;65:936-941.

- Saraclar Y, Tinaztepe K, Adalioğlu G, et al. Acute hemorrhagic edema of infancy (AHEI)—a variant of Henoch-Schönlein purpura or a distinct clinical entity? J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1990;86:473-483.

- Shinkai K, Fox L. Cutaneous vasculitis. In: Bolognia J, Jorizzo J, Schaffer J, eds. Dermatology. 3rd ed. China: Elsevier Limited; 2012:385-410.

Practice Points

- Acute hemorrhagic edema of infancy (AHEI) is an uncommon benign leukocytoclastic vasculitis of unknown precise pathophysiology that is thought be immune complex mediated.

- Clinical history, physical examination, and histopathologic analysis combine to allow the important differentiation between AHEI and Henoch-Schönlein purpura (HSP).

- Differentiation between AHEI and HSP determines treatment decisions and indicates the need for counseling on potential associated renal and gastrointestinal risks of HSP.

Guttate Psoriasis Outcomes

Guttate psoriasis (GP) typically occurs abruptly following an acute infection such as streptococcal pharyngitis. It is thought to have a good prognosis and show rapid resolution; however, there are limited studies addressing long-term outcomes of GP, particularly the probability of developing chronic plaque psoriasis (PP) following a single episode of acute GP.

Ko et al1 reported a long-term follow-up study of Korean patients with acute GP. The investigators determined that 19 of 36 participants (38.9%) with acute GP went on to develop chronic PP over a mean follow-up period of 6.3 years. Martin et al2 reported a smaller follow-up study of 15 patients in England; 5 of 15 patients (33.3%) developed chronic PP within 10 years.

Methods

A retrospective cohort study was performed using data from the Geisinger Medical Center (Danville, Pennsylvania) electronic medical records from January 2000 to September 2012 to identify medical records that showed a specific clinical diagnosis of GP or a diagnosis of either dermatitis or psoriasis with a positive molecular probe for streptococci or antistreptolysin O (ASO) titer. (A molecular probe is used in place of culture for streptococcal pharyngeal specimens at our institution.) A separate search of the Co-Path database for biopsy-proven GP also was performed. Each medical record was reviewed by one of the authors (L.F.P.) to confirm the true diagnosis of GP. Exclusion criteria included a prior diagnosis of PP or a follow-up period of less than 1 year. Based on this chart review, the prevalence of developing chronic PP in patients with GP was determined. The patients were split into 2 cohorts: those who had a single episode of GP with resolution versus those who developed PP. We compared the clinical characteristics to those who developed chronic PP. The clinical characteristics that were recorded included patient age; whether or not the patient developed PP; length of time for clearance of GP; molecular probe or ASO results; family history; GP treatment used; smoking status; and comorbid conditions such as hyperlipidemia, hypertension, diabete mellitus, and obesity, which were lumped under the category of metabolic syndrome due to their low prevalence individually.

The study group data set contained 79 patients with GP who had a history of at least 1 year of follow-up. Descriptive statistics of the patients were provided for continuous and categorical variables in the study. Continuous variables were described using the mean and SD or, for skewed distributions, the median and interquartile range (25th-75th percentiles), while categorical variables were presented using frequency counts and percentages. Comparisons between groups were tested using 2-sample t tests or Wilcoxon rank sum tests, or Pearson χ2 or Fisher exact tests, as appropriate.

Results

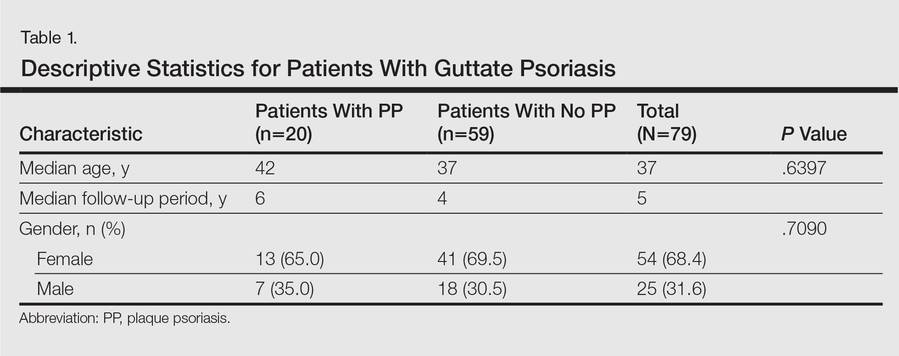

A total of 79 patients were included in the study. Descriptive statistics for the total patient population as well as those who did and did not develop PP are shown in Table 1. The median age of patients was 37 years. The median follow-up time was 5 years. The majority of patients were female (68.4%). There were 20 patients (25.3%) who developed PP and 59 (74.7%) who did not (95% CI, 0.1-0.36).

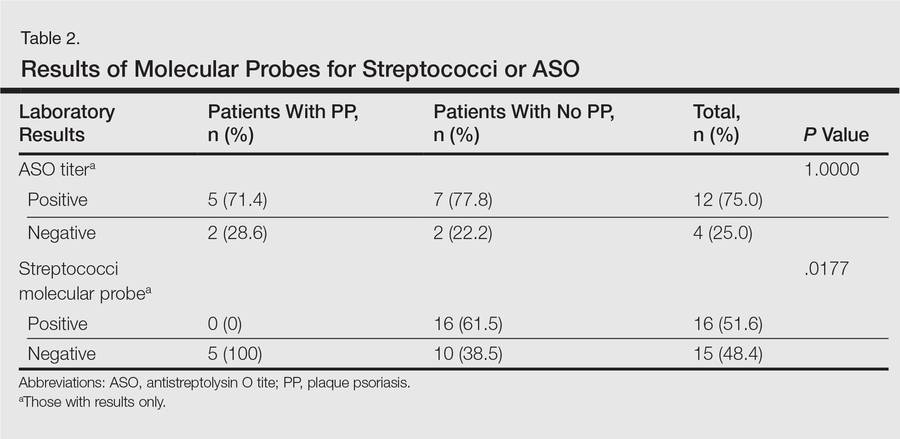

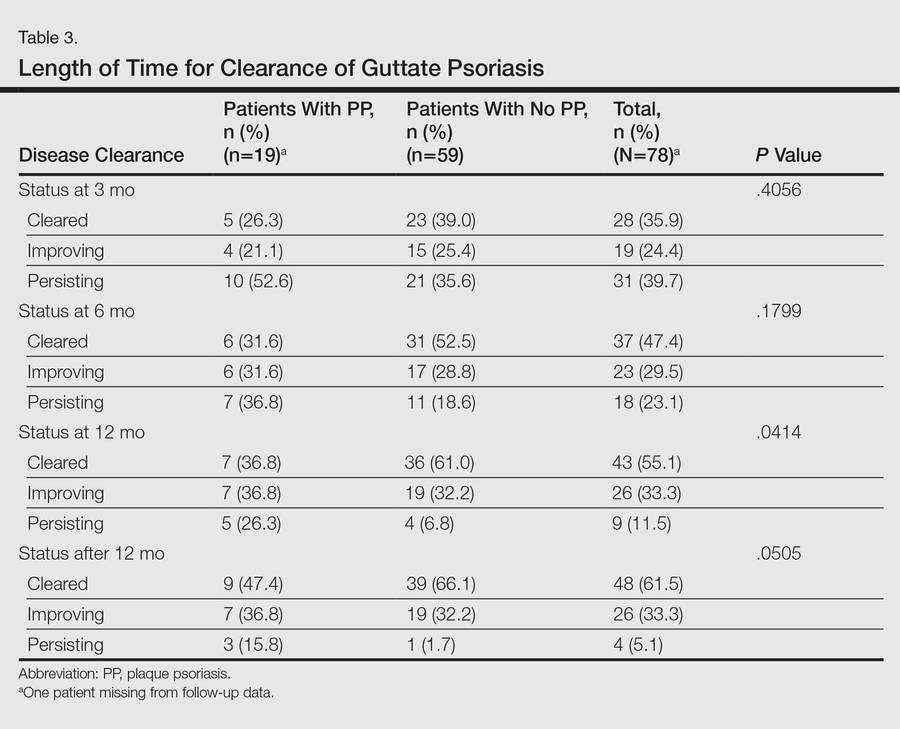

Molecular probes for streptoccoci were obtained from 31 patients (39.2%) during the workup for GP. Patients who had a molecular probe and developed PP were less likely to have had a molecular probe that was positive for streptococci versus patients who did not develop PP (0% vs 61.5%; P=.0177)(Table 2). Patients who developed PP were more likely to have persistent GP at 12 months than patients who did not develop PP (26.3% vs 6.8%, respectively; P=.0414). At the end of the observation period, 4 patients (5.1%) did not yet show GP clearance. The patients who developed PP were more likely to have had a case of GP that never cleared than patients who did not develop PP (15.8% vs 1.7%; P=.0505)(Table 3).

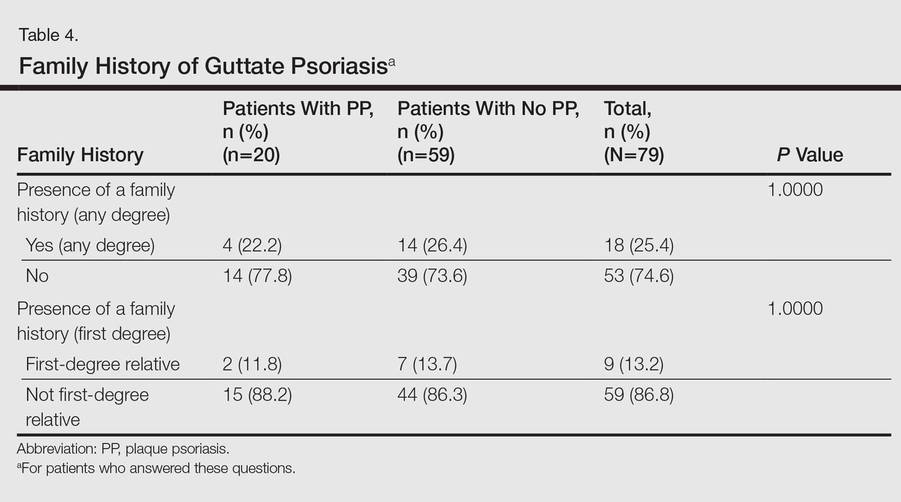

No significant differences were detected among those who developed PP compared to those who did not with respect to any degree of family history of psoriasis (22.2% vs 26.4%; P=1.0000)(Table 4). There were no significant differences in the value of a positive ASO titer between groups (Table 2), but it should be noted that the small number of patients with positive values in each group impacts a test’s power to detect statistically significant differences. There were no significant differences in the likelihood of developing PP if a patient was treated with systemic steroids or antibiotics (data not shown). Additionally, smoking status, hyperlipidemia, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and obesity were not predictive of evolution of GP into PP (data not shown).

Comment

Ryan et al3 noted in a report on research gaps in psoriasis that studies are needed to validate frequency and characteristic factors associated with spontaneous remission for different phenotypes of psoriasis, including disease severity, patient age, morphologic attributes of plaques, and comorbidities. Our analysis attempts to bridge this gap in reference to type, specifically GP, and factors associated with development of chronic PP.

Our study showed that 20 of 79 patients (25.3%) with GP went on to develop chronic PP. The incidence is slightly lower than in prior smaller studies from Korea and England, which reported incidence rates of 38.9% and 33.3%, respectively.1,2 Although Ko et al1 noted that a younger age of onset was more frequently found in the cohort with complete remission of GP, this finding was not observed in our study. Although only a minority of patients underwent a molecular probe for streptococci, of those who were tested and had positive results, they were significantly less likely to develop chronic PP (P=.0177). This finding supports the classic teaching that GP originates after an episode of a streptococcal infection. Of those who developed PP, only one-fourth had been tested for streptococci via molecular probe and all were negative. Interestingly, there was no difference noted in those that had ASO titers drawn (P=1.0000). Although the data were too low to achieve statistical significance, this finding contrasts with Ko et al1 who reported that a high ASO titer correlated with a good prognosis (ie, GP did not evolve into PP). There was no difference in the likelihood of developing PP seen in patients that were treated with antibiotics (P=.1651), suggesting that obtaining a molecular probe that is positive for streptococci may be predictive of prognosis (ie, resolution) and thus is a reasonable diagnostic test to obtain. We do recognize that nonpharyngeal sources for streptococci may occur (ie, perianal), but these data were not captured in our patient population.

In our study, patients were more likely to develop chronic PP if they had a GP history that was longer than 12 months. Ko et al1 also showed that GP patients who did not develop PP were typically cleared after 8 months. There were no statistical differences noted when comparing the different treatments used to treat GP. It appears that the rapidity with which the episode clears is more predictive than the method used to clear it.

There were several limitations to this study including the small number of patients, the median 5-year follow-up time, and the retrospective design.

Conclusion

Based on our cohort study, we have concluded that GP evolves into chronic PP in approximately 25% of cases. Obtaining a group A streptococcal molecular probe or culture may serve as a prognostic tool, as physicians should recognize that GP flares associated with a positive result indicate a favorable prognosis. Additionally, GP flares that resolve within the first year of an outbreak, regardless of treatment choice, are less likely to be followed by chronic PP.

- Ko HC, Jwa SW, Song M, et al. Clinical course of guttate psoriasis: long-term follow up study. J Dermatol. 2010;37:894-899.

- Martin BA, Chalmers RJ, Telfer NR. How great is the risk of further psoriasis following a single episode of acute guttate psoriasis? Arch Dermatol. 1996;132:717-718.

- Ryan C, Korman NJ, Gelfand JM, et al. Research gaps in psoriasis: opportunities for future studies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:146-167.

Guttate psoriasis (GP) typically occurs abruptly following an acute infection such as streptococcal pharyngitis. It is thought to have a good prognosis and show rapid resolution; however, there are limited studies addressing long-term outcomes of GP, particularly the probability of developing chronic plaque psoriasis (PP) following a single episode of acute GP.

Ko et al1 reported a long-term follow-up study of Korean patients with acute GP. The investigators determined that 19 of 36 participants (38.9%) with acute GP went on to develop chronic PP over a mean follow-up period of 6.3 years. Martin et al2 reported a smaller follow-up study of 15 patients in England; 5 of 15 patients (33.3%) developed chronic PP within 10 years.

Methods

A retrospective cohort study was performed using data from the Geisinger Medical Center (Danville, Pennsylvania) electronic medical records from January 2000 to September 2012 to identify medical records that showed a specific clinical diagnosis of GP or a diagnosis of either dermatitis or psoriasis with a positive molecular probe for streptococci or antistreptolysin O (ASO) titer. (A molecular probe is used in place of culture for streptococcal pharyngeal specimens at our institution.) A separate search of the Co-Path database for biopsy-proven GP also was performed. Each medical record was reviewed by one of the authors (L.F.P.) to confirm the true diagnosis of GP. Exclusion criteria included a prior diagnosis of PP or a follow-up period of less than 1 year. Based on this chart review, the prevalence of developing chronic PP in patients with GP was determined. The patients were split into 2 cohorts: those who had a single episode of GP with resolution versus those who developed PP. We compared the clinical characteristics to those who developed chronic PP. The clinical characteristics that were recorded included patient age; whether or not the patient developed PP; length of time for clearance of GP; molecular probe or ASO results; family history; GP treatment used; smoking status; and comorbid conditions such as hyperlipidemia, hypertension, diabete mellitus, and obesity, which were lumped under the category of metabolic syndrome due to their low prevalence individually.

The study group data set contained 79 patients with GP who had a history of at least 1 year of follow-up. Descriptive statistics of the patients were provided for continuous and categorical variables in the study. Continuous variables were described using the mean and SD or, for skewed distributions, the median and interquartile range (25th-75th percentiles), while categorical variables were presented using frequency counts and percentages. Comparisons between groups were tested using 2-sample t tests or Wilcoxon rank sum tests, or Pearson χ2 or Fisher exact tests, as appropriate.

Results

A total of 79 patients were included in the study. Descriptive statistics for the total patient population as well as those who did and did not develop PP are shown in Table 1. The median age of patients was 37 years. The median follow-up time was 5 years. The majority of patients were female (68.4%). There were 20 patients (25.3%) who developed PP and 59 (74.7%) who did not (95% CI, 0.1-0.36).

Molecular probes for streptoccoci were obtained from 31 patients (39.2%) during the workup for GP. Patients who had a molecular probe and developed PP were less likely to have had a molecular probe that was positive for streptococci versus patients who did not develop PP (0% vs 61.5%; P=.0177)(Table 2). Patients who developed PP were more likely to have persistent GP at 12 months than patients who did not develop PP (26.3% vs 6.8%, respectively; P=.0414). At the end of the observation period, 4 patients (5.1%) did not yet show GP clearance. The patients who developed PP were more likely to have had a case of GP that never cleared than patients who did not develop PP (15.8% vs 1.7%; P=.0505)(Table 3).

No significant differences were detected among those who developed PP compared to those who did not with respect to any degree of family history of psoriasis (22.2% vs 26.4%; P=1.0000)(Table 4). There were no significant differences in the value of a positive ASO titer between groups (Table 2), but it should be noted that the small number of patients with positive values in each group impacts a test’s power to detect statistically significant differences. There were no significant differences in the likelihood of developing PP if a patient was treated with systemic steroids or antibiotics (data not shown). Additionally, smoking status, hyperlipidemia, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and obesity were not predictive of evolution of GP into PP (data not shown).

Comment

Ryan et al3 noted in a report on research gaps in psoriasis that studies are needed to validate frequency and characteristic factors associated with spontaneous remission for different phenotypes of psoriasis, including disease severity, patient age, morphologic attributes of plaques, and comorbidities. Our analysis attempts to bridge this gap in reference to type, specifically GP, and factors associated with development of chronic PP.

Our study showed that 20 of 79 patients (25.3%) with GP went on to develop chronic PP. The incidence is slightly lower than in prior smaller studies from Korea and England, which reported incidence rates of 38.9% and 33.3%, respectively.1,2 Although Ko et al1 noted that a younger age of onset was more frequently found in the cohort with complete remission of GP, this finding was not observed in our study. Although only a minority of patients underwent a molecular probe for streptococci, of those who were tested and had positive results, they were significantly less likely to develop chronic PP (P=.0177). This finding supports the classic teaching that GP originates after an episode of a streptococcal infection. Of those who developed PP, only one-fourth had been tested for streptococci via molecular probe and all were negative. Interestingly, there was no difference noted in those that had ASO titers drawn (P=1.0000). Although the data were too low to achieve statistical significance, this finding contrasts with Ko et al1 who reported that a high ASO titer correlated with a good prognosis (ie, GP did not evolve into PP). There was no difference in the likelihood of developing PP seen in patients that were treated with antibiotics (P=.1651), suggesting that obtaining a molecular probe that is positive for streptococci may be predictive of prognosis (ie, resolution) and thus is a reasonable diagnostic test to obtain. We do recognize that nonpharyngeal sources for streptococci may occur (ie, perianal), but these data were not captured in our patient population.

In our study, patients were more likely to develop chronic PP if they had a GP history that was longer than 12 months. Ko et al1 also showed that GP patients who did not develop PP were typically cleared after 8 months. There were no statistical differences noted when comparing the different treatments used to treat GP. It appears that the rapidity with which the episode clears is more predictive than the method used to clear it.

There were several limitations to this study including the small number of patients, the median 5-year follow-up time, and the retrospective design.

Conclusion

Based on our cohort study, we have concluded that GP evolves into chronic PP in approximately 25% of cases. Obtaining a group A streptococcal molecular probe or culture may serve as a prognostic tool, as physicians should recognize that GP flares associated with a positive result indicate a favorable prognosis. Additionally, GP flares that resolve within the first year of an outbreak, regardless of treatment choice, are less likely to be followed by chronic PP.

Guttate psoriasis (GP) typically occurs abruptly following an acute infection such as streptococcal pharyngitis. It is thought to have a good prognosis and show rapid resolution; however, there are limited studies addressing long-term outcomes of GP, particularly the probability of developing chronic plaque psoriasis (PP) following a single episode of acute GP.

Ko et al1 reported a long-term follow-up study of Korean patients with acute GP. The investigators determined that 19 of 36 participants (38.9%) with acute GP went on to develop chronic PP over a mean follow-up period of 6.3 years. Martin et al2 reported a smaller follow-up study of 15 patients in England; 5 of 15 patients (33.3%) developed chronic PP within 10 years.

Methods

A retrospective cohort study was performed using data from the Geisinger Medical Center (Danville, Pennsylvania) electronic medical records from January 2000 to September 2012 to identify medical records that showed a specific clinical diagnosis of GP or a diagnosis of either dermatitis or psoriasis with a positive molecular probe for streptococci or antistreptolysin O (ASO) titer. (A molecular probe is used in place of culture for streptococcal pharyngeal specimens at our institution.) A separate search of the Co-Path database for biopsy-proven GP also was performed. Each medical record was reviewed by one of the authors (L.F.P.) to confirm the true diagnosis of GP. Exclusion criteria included a prior diagnosis of PP or a follow-up period of less than 1 year. Based on this chart review, the prevalence of developing chronic PP in patients with GP was determined. The patients were split into 2 cohorts: those who had a single episode of GP with resolution versus those who developed PP. We compared the clinical characteristics to those who developed chronic PP. The clinical characteristics that were recorded included patient age; whether or not the patient developed PP; length of time for clearance of GP; molecular probe or ASO results; family history; GP treatment used; smoking status; and comorbid conditions such as hyperlipidemia, hypertension, diabete mellitus, and obesity, which were lumped under the category of metabolic syndrome due to their low prevalence individually.

The study group data set contained 79 patients with GP who had a history of at least 1 year of follow-up. Descriptive statistics of the patients were provided for continuous and categorical variables in the study. Continuous variables were described using the mean and SD or, for skewed distributions, the median and interquartile range (25th-75th percentiles), while categorical variables were presented using frequency counts and percentages. Comparisons between groups were tested using 2-sample t tests or Wilcoxon rank sum tests, or Pearson χ2 or Fisher exact tests, as appropriate.

Results

A total of 79 patients were included in the study. Descriptive statistics for the total patient population as well as those who did and did not develop PP are shown in Table 1. The median age of patients was 37 years. The median follow-up time was 5 years. The majority of patients were female (68.4%). There were 20 patients (25.3%) who developed PP and 59 (74.7%) who did not (95% CI, 0.1-0.36).

Molecular probes for streptoccoci were obtained from 31 patients (39.2%) during the workup for GP. Patients who had a molecular probe and developed PP were less likely to have had a molecular probe that was positive for streptococci versus patients who did not develop PP (0% vs 61.5%; P=.0177)(Table 2). Patients who developed PP were more likely to have persistent GP at 12 months than patients who did not develop PP (26.3% vs 6.8%, respectively; P=.0414). At the end of the observation period, 4 patients (5.1%) did not yet show GP clearance. The patients who developed PP were more likely to have had a case of GP that never cleared than patients who did not develop PP (15.8% vs 1.7%; P=.0505)(Table 3).

No significant differences were detected among those who developed PP compared to those who did not with respect to any degree of family history of psoriasis (22.2% vs 26.4%; P=1.0000)(Table 4). There were no significant differences in the value of a positive ASO titer between groups (Table 2), but it should be noted that the small number of patients with positive values in each group impacts a test’s power to detect statistically significant differences. There were no significant differences in the likelihood of developing PP if a patient was treated with systemic steroids or antibiotics (data not shown). Additionally, smoking status, hyperlipidemia, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and obesity were not predictive of evolution of GP into PP (data not shown).

Comment

Ryan et al3 noted in a report on research gaps in psoriasis that studies are needed to validate frequency and characteristic factors associated with spontaneous remission for different phenotypes of psoriasis, including disease severity, patient age, morphologic attributes of plaques, and comorbidities. Our analysis attempts to bridge this gap in reference to type, specifically GP, and factors associated with development of chronic PP.

Our study showed that 20 of 79 patients (25.3%) with GP went on to develop chronic PP. The incidence is slightly lower than in prior smaller studies from Korea and England, which reported incidence rates of 38.9% and 33.3%, respectively.1,2 Although Ko et al1 noted that a younger age of onset was more frequently found in the cohort with complete remission of GP, this finding was not observed in our study. Although only a minority of patients underwent a molecular probe for streptococci, of those who were tested and had positive results, they were significantly less likely to develop chronic PP (P=.0177). This finding supports the classic teaching that GP originates after an episode of a streptococcal infection. Of those who developed PP, only one-fourth had been tested for streptococci via molecular probe and all were negative. Interestingly, there was no difference noted in those that had ASO titers drawn (P=1.0000). Although the data were too low to achieve statistical significance, this finding contrasts with Ko et al1 who reported that a high ASO titer correlated with a good prognosis (ie, GP did not evolve into PP). There was no difference in the likelihood of developing PP seen in patients that were treated with antibiotics (P=.1651), suggesting that obtaining a molecular probe that is positive for streptococci may be predictive of prognosis (ie, resolution) and thus is a reasonable diagnostic test to obtain. We do recognize that nonpharyngeal sources for streptococci may occur (ie, perianal), but these data were not captured in our patient population.

In our study, patients were more likely to develop chronic PP if they had a GP history that was longer than 12 months. Ko et al1 also showed that GP patients who did not develop PP were typically cleared after 8 months. There were no statistical differences noted when comparing the different treatments used to treat GP. It appears that the rapidity with which the episode clears is more predictive than the method used to clear it.

There were several limitations to this study including the small number of patients, the median 5-year follow-up time, and the retrospective design.

Conclusion

Based on our cohort study, we have concluded that GP evolves into chronic PP in approximately 25% of cases. Obtaining a group A streptococcal molecular probe or culture may serve as a prognostic tool, as physicians should recognize that GP flares associated with a positive result indicate a favorable prognosis. Additionally, GP flares that resolve within the first year of an outbreak, regardless of treatment choice, are less likely to be followed by chronic PP.

- Ko HC, Jwa SW, Song M, et al. Clinical course of guttate psoriasis: long-term follow up study. J Dermatol. 2010;37:894-899.

- Martin BA, Chalmers RJ, Telfer NR. How great is the risk of further psoriasis following a single episode of acute guttate psoriasis? Arch Dermatol. 1996;132:717-718.

- Ryan C, Korman NJ, Gelfand JM, et al. Research gaps in psoriasis: opportunities for future studies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:146-167.

- Ko HC, Jwa SW, Song M, et al. Clinical course of guttate psoriasis: long-term follow up study. J Dermatol. 2010;37:894-899.

- Martin BA, Chalmers RJ, Telfer NR. How great is the risk of further psoriasis following a single episode of acute guttate psoriasis? Arch Dermatol. 1996;132:717-718.

- Ryan C, Korman NJ, Gelfand JM, et al. Research gaps in psoriasis: opportunities for future studies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:146-167.

Practice Points

- Following an initial episode of guttate psoriasis, a patient has a 25.3% chance of developing plaque psoriasis (PP).

- A streptococci culture can be prognostic; if the culture is positive, the patient is less likely to develop PP.

- If the patient’s rash clears within 1 year, he/she is less likely to develop PP.