User login

Q Do androgen levels help diagnose low libido?

Expert commentary

In women, androgen insufficiency is generally defined as a cluster of symptoms and signs—diminished well-being, unexplained fatigue, decreased sexual desire, and thinning pubic hair—in the presence of decreased bioavailable testosterone and normal estrogen. However, we lack evidence that this syndrome can be diagnosed by measuring circulating androgens.

Davis and colleagues explored the question by randomly recruiting 1,423 women aged 18 to 75 from the electoral rolls of Victoria, Australia. Voting is mandatory in Australia, where every adult is on the rolls; thus, the study population represented a cross-section of the general female adult population in that country.

After exclusions, Davis et al measured circulating androgens and sexual function (by a self-reported scale) in 1,021 women. The objective: to determine whether women who reported “low sexual well-being” were more likely to have low serum androgen levels than women who did not.

No correlation between testosterone and libido

Davis and colleagues found no evidence that total or free testosterone levels help determine which women have low sexual function. Although significant associations were noted between low levels of dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate (DHEAS) and sexual dysfunction, Davis et al found no diagnostically useful reason to measure DHEAS. Most women with low DHEAS reported no sexual dysfunction, and most women with sexual dysfunction lacked low DHEAS.

The likelihood of a clinically useful association between women with low sexual function and a low androgen level was greatest when the proportion of women with low sexual function was small (less than the fifth percentile) and the normal range for the serum androgen level was relatively large, such as the DHEAS level among young women.1

Still no correlation in women at midlife

In the second study, Dennerstein et al used data collected over 8 years from the Melbourne Women’s Midlife Health Project, a prospective, longitudinal, population-based study of Australian women aged 45 to 55. They chose this age group because hormonal changes during the menopausal transition “do not occur in a vacuum.” Rather, the midlife years coincide with other transitions as children leave home and parents age. In addition, some women may lose or change sexual partners, some of whom have their own problems with sexual function. The authors wanted to determine whether women’s sexual function is more dependent on psychosocial and relationship factors than on actual hormone levels.

The study involved annual measurements of both sexual function (by questionnaire) and hormone levels. Data were available from 336 women.

The findings: Only estradiol levels had a direct effect on sexual function, and then only on sexual response and dyspareunia. However, estradiol levels were less important than prior levels of sexual function, a change in partners, or feelings for the partner. Testosterone and DHEAS levels did not correlate with sexual function.

So how do we diagnose low libido?

Although a correlation may exist between low levels of circulating androgens and sexual dysfunction,2 there is no consensus on the clinical utility of measuring androgens to diagnose it. These studies are consistent with others that have failed to find serum testosterone levels useful in diagnosing androgen insufficiency.3

One possibility may be that commercial assays for testosterone lack sufficient sensitivity and reliability to accurately measure the low levels of testosterone found in women, although the authors of both studies used reliable and reproducible methods.

Thus, for the time being, at least, androgen insufficiency syndrome remains a clinical diagnosis.

The commentators report no financial relationships relevant to this article.

1. Davison S, Bell R, Donath S, Montalto J, Davis S. Androgen levels in adult females: changes with age, menopause and oophorectomy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. In press.

2. Turna B, Apaydin E, Semerci B, Altay B, Cikili N, Nazli O. Women with low libido: correlation of decreased androgen levels with female sexual function index. Int J Impot Res. 2005;17:148-153.

3. Bachmann G, Bancroft J, Braunstein G, et al. Female androgen insufficiency: the Princeton consensus statement on definition, classification, and assessment. Fertil Steril. 2002;77:660-665.

Expert commentary

In women, androgen insufficiency is generally defined as a cluster of symptoms and signs—diminished well-being, unexplained fatigue, decreased sexual desire, and thinning pubic hair—in the presence of decreased bioavailable testosterone and normal estrogen. However, we lack evidence that this syndrome can be diagnosed by measuring circulating androgens.

Davis and colleagues explored the question by randomly recruiting 1,423 women aged 18 to 75 from the electoral rolls of Victoria, Australia. Voting is mandatory in Australia, where every adult is on the rolls; thus, the study population represented a cross-section of the general female adult population in that country.

After exclusions, Davis et al measured circulating androgens and sexual function (by a self-reported scale) in 1,021 women. The objective: to determine whether women who reported “low sexual well-being” were more likely to have low serum androgen levels than women who did not.

No correlation between testosterone and libido

Davis and colleagues found no evidence that total or free testosterone levels help determine which women have low sexual function. Although significant associations were noted between low levels of dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate (DHEAS) and sexual dysfunction, Davis et al found no diagnostically useful reason to measure DHEAS. Most women with low DHEAS reported no sexual dysfunction, and most women with sexual dysfunction lacked low DHEAS.

The likelihood of a clinically useful association between women with low sexual function and a low androgen level was greatest when the proportion of women with low sexual function was small (less than the fifth percentile) and the normal range for the serum androgen level was relatively large, such as the DHEAS level among young women.1

Still no correlation in women at midlife

In the second study, Dennerstein et al used data collected over 8 years from the Melbourne Women’s Midlife Health Project, a prospective, longitudinal, population-based study of Australian women aged 45 to 55. They chose this age group because hormonal changes during the menopausal transition “do not occur in a vacuum.” Rather, the midlife years coincide with other transitions as children leave home and parents age. In addition, some women may lose or change sexual partners, some of whom have their own problems with sexual function. The authors wanted to determine whether women’s sexual function is more dependent on psychosocial and relationship factors than on actual hormone levels.

The study involved annual measurements of both sexual function (by questionnaire) and hormone levels. Data were available from 336 women.

The findings: Only estradiol levels had a direct effect on sexual function, and then only on sexual response and dyspareunia. However, estradiol levels were less important than prior levels of sexual function, a change in partners, or feelings for the partner. Testosterone and DHEAS levels did not correlate with sexual function.

So how do we diagnose low libido?

Although a correlation may exist between low levels of circulating androgens and sexual dysfunction,2 there is no consensus on the clinical utility of measuring androgens to diagnose it. These studies are consistent with others that have failed to find serum testosterone levels useful in diagnosing androgen insufficiency.3

One possibility may be that commercial assays for testosterone lack sufficient sensitivity and reliability to accurately measure the low levels of testosterone found in women, although the authors of both studies used reliable and reproducible methods.

Thus, for the time being, at least, androgen insufficiency syndrome remains a clinical diagnosis.

The commentators report no financial relationships relevant to this article.

Expert commentary

In women, androgen insufficiency is generally defined as a cluster of symptoms and signs—diminished well-being, unexplained fatigue, decreased sexual desire, and thinning pubic hair—in the presence of decreased bioavailable testosterone and normal estrogen. However, we lack evidence that this syndrome can be diagnosed by measuring circulating androgens.

Davis and colleagues explored the question by randomly recruiting 1,423 women aged 18 to 75 from the electoral rolls of Victoria, Australia. Voting is mandatory in Australia, where every adult is on the rolls; thus, the study population represented a cross-section of the general female adult population in that country.

After exclusions, Davis et al measured circulating androgens and sexual function (by a self-reported scale) in 1,021 women. The objective: to determine whether women who reported “low sexual well-being” were more likely to have low serum androgen levels than women who did not.

No correlation between testosterone and libido

Davis and colleagues found no evidence that total or free testosterone levels help determine which women have low sexual function. Although significant associations were noted between low levels of dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate (DHEAS) and sexual dysfunction, Davis et al found no diagnostically useful reason to measure DHEAS. Most women with low DHEAS reported no sexual dysfunction, and most women with sexual dysfunction lacked low DHEAS.

The likelihood of a clinically useful association between women with low sexual function and a low androgen level was greatest when the proportion of women with low sexual function was small (less than the fifth percentile) and the normal range for the serum androgen level was relatively large, such as the DHEAS level among young women.1

Still no correlation in women at midlife

In the second study, Dennerstein et al used data collected over 8 years from the Melbourne Women’s Midlife Health Project, a prospective, longitudinal, population-based study of Australian women aged 45 to 55. They chose this age group because hormonal changes during the menopausal transition “do not occur in a vacuum.” Rather, the midlife years coincide with other transitions as children leave home and parents age. In addition, some women may lose or change sexual partners, some of whom have their own problems with sexual function. The authors wanted to determine whether women’s sexual function is more dependent on psychosocial and relationship factors than on actual hormone levels.

The study involved annual measurements of both sexual function (by questionnaire) and hormone levels. Data were available from 336 women.

The findings: Only estradiol levels had a direct effect on sexual function, and then only on sexual response and dyspareunia. However, estradiol levels were less important than prior levels of sexual function, a change in partners, or feelings for the partner. Testosterone and DHEAS levels did not correlate with sexual function.

So how do we diagnose low libido?

Although a correlation may exist between low levels of circulating androgens and sexual dysfunction,2 there is no consensus on the clinical utility of measuring androgens to diagnose it. These studies are consistent with others that have failed to find serum testosterone levels useful in diagnosing androgen insufficiency.3

One possibility may be that commercial assays for testosterone lack sufficient sensitivity and reliability to accurately measure the low levels of testosterone found in women, although the authors of both studies used reliable and reproducible methods.

Thus, for the time being, at least, androgen insufficiency syndrome remains a clinical diagnosis.

The commentators report no financial relationships relevant to this article.

1. Davison S, Bell R, Donath S, Montalto J, Davis S. Androgen levels in adult females: changes with age, menopause and oophorectomy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. In press.

2. Turna B, Apaydin E, Semerci B, Altay B, Cikili N, Nazli O. Women with low libido: correlation of decreased androgen levels with female sexual function index. Int J Impot Res. 2005;17:148-153.

3. Bachmann G, Bancroft J, Braunstein G, et al. Female androgen insufficiency: the Princeton consensus statement on definition, classification, and assessment. Fertil Steril. 2002;77:660-665.

1. Davison S, Bell R, Donath S, Montalto J, Davis S. Androgen levels in adult females: changes with age, menopause and oophorectomy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. In press.

2. Turna B, Apaydin E, Semerci B, Altay B, Cikili N, Nazli O. Women with low libido: correlation of decreased androgen levels with female sexual function index. Int J Impot Res. 2005;17:148-153.

3. Bachmann G, Bancroft J, Braunstein G, et al. Female androgen insufficiency: the Princeton consensus statement on definition, classification, and assessment. Fertil Steril. 2002;77:660-665.

Sexual dysfunction: The challenge of treatment

Case reports of patients helped by therapy,

Say you see 100 adult patients this week. How many have a sexual dysfunction? 10? 20? Would you believe 43? In a National Health and Social Life Survey1 of 1,749 women and 1,410 men aged 18 to 59 years, 43% of women and 31% of men reported sexual dysfunction. Rates that high make sexual dysfunction an important public health concern—one that is highly associated with impaired well-being and negative experiences in sexual relationships.

Similar findings marked a study2 of general practice patients in Britain: 41% of 979 women and 34% of 789 men reported sexual dysfunction. Although 52% wanted professional help, only 10% had received it.

As primary care providers, Ob/Gyns must identify common problems, treat those within our expertise, and refer the others. In all likelihood, we are the first physicians women see about a sexual problem. For these reasons—and because dysfunction is so common—it is appropriate that we screen for and address female sexual dysfunction.

This article presents a medical model of management and tells how to take a sexual history, formulate a differential diagnosis, manage common sexual problems, and identify indications for referral.

The medical model

According to the medical model, a patient presents with a problem, which is investigated by history and physical examination. A differential diagnosis is formulated, and appropriate laboratory tests or other evaluations are conducted. The patient’s problem is compared to a normal physiologic process to determine pathophysiology. Diagnosis and therapy follow.

The medical model for sexual dysfunction is the same as that for any disease, such as asthma, in which normal breathing is interrupted. In the sexual response cycle, physiologic changes can be measured and specifically described, as Masters and Johnson explained in 1966 in Human Sexual Response (FIGURE 1). Any barriers that interrupt this progression “block” the normal response cycle, resulting in sexual dysfunction. We aim to identify and remove or get around any barriers.

FIGURE 1 Use the sexual response cycle in dialogue with the patient

Most patients with sexual dysfunction can identify the phase in the Masters and Johnson sexual response cycle where normal progression is interrupted. Using a sketch of this cycle helps patients understand and articulate their problem.

The sexual response cycle

Desire initiates the cycle, followed by the excitement phase, during which breathing rate and pulse increase, blood flow shifts away from muscles and into the skin and pelvic organs, and there is an associated expansion, lengthening, and lubrication of the vagina. A plateau follows, during which there is no further increase in signs such as increased pulse rate. Orgasm is the first point in the response cycle that is different in men and women. Men have an obligatory resolution phase and return to baseline state; women can return to the plateau state and then have another orgasm. The resolution phase lengthens in duration in both sexes with increasing age.

The sexual response cycle is innate, like any physiologic process. It cannot be taught or learned, and is not under voluntary control. It is critical that patients understand that the sexual response cycle is a natural function that everyone has—just as everyone has innate capacity to breathe. Patients do not learn it, any more than they have to learn respiration.

Sexual behavior, however, is learned, and sexual dysfunctions are exhibited by behavior. Sex therapy is a learning process, the aim of which is to change the behavior. Sexual dysfunctions have both cognitive and physical components; although response is physiologic, it can be altered by emotion, as can respiration.

The relationship is the patient. Sexual dysfunction occurs within a relationship, and the relationship needs and stands to benefit from therapy.

Reassuring anxious, angry patients

Approach is critical, and must reflect an understanding that sexual dysfunction is real. Many patients have been told that the problem is “all in their head” or that they are deliberately acting dysfunctionally.

Confrontation and support are useful communication tools. Confrontation means identifying behaviors and beliefs and how beliefs influence behaviors. Support means conveying to the patient that you understand that she is in distress and that it couldn’t have happened any other way for her.

A “therapeutic mirror” technique can show the patient her beliefs, attitudes, and behaviors. The therapist repeats the the patient’s beliefs and behaviors until the patient states that they are an accurate reflection, or tells the therapist what is inaccurate.

Assure the patient that anxiety is to be expected, and that her probelm is common and treatable. These patients believe they have thought of everything, and nothing has worked. Just reassuring them may help.

Anger must also be acknowledged—and these patients are angry. Their anger may be directed at their partner, a former physician, or you. You may elicit a surprising outburst of pent-up anger when you ask what seems to be a neutral question.

The patient always has an internal theory and everything you say is filtered through this theory. If there is a dichotomy, it must be addressed before you can proceed successfully. Usually, you can simply ask, “What do you think is the cause?” Often she will tell you. If she is uncertain, you might say, “I realize you don’t really know. What do you think it might be? What are you afraid it might be?”

You have to ask

Many patients do not express the fact that their chief complaint is sexual dysfunction. (See How to take a sexual history,).

In many cases, sexual dysfunction may be suggested in the investigation of another complaint such as infertility, pelvic pain with no particular pattern, malaise, or depression. With these complaints, it is important to pursue a sexual history. Determine any associated or causal condition and look for associated dysfunction.

The sexual history is like a history for any disease, in that you begin with the present illness. The differential diagnosis begins with a determination of where in the cycle the dysfunction occurs.

- One way to start is to describe the normal human sexual response. I find it best to sketch out the response cycle (FIGURE 1 ) on a piece of paper and ask, “Is this what happens to you?” Most patients understand and can tell where in the cycle the interruption occurs.

- 3 questions in a review of systems disclose nearly all sexual dysfunction:

- “How often do you have intercourse?” The only “right” answer is “as often as I want to.” If the patient is not having intercourse, is it by choice or involuntary?

- “Do you have pain with intercourse?”

- “How often do you have orgasm?” Most answer “hardly ever” or “most of the time.”

- Allegories like these are useful:

- Elements and example questions

Physical examination

Ageneral physical examination with pelvic examination should always be performed. If the patient complains of pain, the site of pain should be determined. A wet prep is useful to exclude vaginitis. A patient may have dyspareunia from vaginitis even if there are no obvious physical signs.

The most common dysfunctions: Desire phase disorders

Female sexual arousal disorder is either low libido or inhibited sexual desire. In both cases the patient is likely to report that she has no desire. But if you ask what happens when her partner wants to have intercourse, a patient with low libido describes low interest behavior, and a patient with inhibited desire describes aversion behavior.

Patients with low libido sometimes report that their orgasms are less intense, or that they do not become excited. Women on estrogen replacement after oophorectomy may have low libido related to decreased androgen.

Depression is by far the most common cause. Other contributors: chronic disease, hypoestrogenic states, hyperprolactinemia, and breastfeeding.

Inhibited sexual desire, which is a result of pain or other dysfunction, is far more common than low libido. Careful history usually reveals aversion behavior. They avoid going to bed at the same time as their partner, or develop other behaviors that preclude intercourse.

Women with inhibited desire have a conditioned negative response. In studies, these patients exhibit normal objective measures of vaginal vasocongestion in response to sexual stimuli, but self-reported subjective measures of arousal do not correlate.

They report that they simply have no desire, but the cause of their avoidance is negative conditioning. Here’s where the therapist supports, but also confronts their belief system, and attempts to help them understand that they have a normal desire for intercourse. The therapist may ask the patient to consider whether she ever has sexual dreams, reads romance novels, or fantasizes, to show that these phenomena demonstrate normal desire.

The role of testosterone in inhibited sexual desire

Measuring serum testosterone isn’t helpful. It is my belief that inhibited desire is most often related to other factors. Counseling should be the first-line therapy. Drug therapy without counseling is less likely to be effective than therapy that includes counseling.

Normal serum testosterone levels are 20 to 80 ng/dL in reproductive-age women, who produce 0.2 to 0.3 mg/day of testosterone. Levels increase 10% to 20% at midcycle. Testosterone falls 40% to 60% at natural menopause and by similar amounts with use of oral contraceptive pills, and by 80% with surgical menopause.

Testosterone levels have little correlation with sexual desire in cycling women or women on oral contraceptives.3 Most studies have found no correlation between testosterone levels and sexual function in perimenopausal or naturally menopausal women.4,5 Other studies have failed to show a difference in testosterone levels between women with arousal disorders and normal controls.6

Testosterone therapy may be effective in surgically menopausal women with low libido. Shifrin and colleagues7 randomized 75 surgically menopausal women being treated with conjugated equine estrogens to placebo or transdermal testosterone, 150 or 300 μg per day, in a crossover trial. They reported, “Despite an appreciable placebo response, the higher testosterone dose resulted in further increases in scores for frequency of sexual activity and pleasure-orgasm. At the higher dose, the percentages of women who had sexual fantasies, masturbated, or engaged in sexual intercourse at least once a week increased 2 to 3 times from base line.”

Testosterone is not yet approved for female sexual dysfunction, but a transdermal testosterone is being proposed for women with hypoactive sexual desire disorder who have had bilateral oophorectomy.

Excitement phase disorders

These disorders are caused by pain with intercourse. What the patient says about the site of pain and when she began experiencing pain help form the differential diagnosis.

Dyspareunia can be due to physiological causes such as obstetric laceration, endometriosis, pelvic inflammatory disease, vaginitis, vulvar disease, and vestibulitis. Interstitial cystitis and inflammatory bowel disease can cause dyspareunia, as can a simple fungal infection. Ask how long the pain continues after intercourse. If internal pain continues for hours, it is highly suggestive of intra-abdominal pathology.

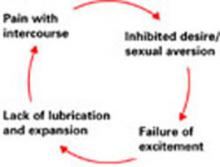

Any cause of pain can begin a self-perpetuating conditioned response cycle that leads to inhibited desire. Anything that causes pain elicits aversion behavior, even without the stimulus. With conditioned response comes failure of excitement, which is where the sexual response cycle is interrupted.

When pain interrupts the sexual response cycle, the patient may still have intercourse, but without excitement, lubrication, and vaginal expansion—and with consequent further pain. Further attempts at intercourse then cause more pain, leading to the cycle of dyspareunia. Pain may be introital, vaginal, or deep. The pain may be reproduced on exam.

Treatment is twofold. Identify and correct source of pain first. Then the patient must learn that intercourse is not painful but pleasurable. Sensate focus exercises are often useful.

Vaginismus, an involuntary spasm of muscles around the outer third of the vagina, may make penetration impossible. Vaginismus can be caused by pain, severe negative parental attitudes about sex, or extreme religious orthodoxy. These patients may be hyper-feminine. They often have bizarre mental images of their genitals. They usually have a partner who supports the dysfunction.

Treatment involves dilators, but the purpose is not to dilate the vagina. It is to learn to have something in the vagina and to confront fears and feelings rregarding penetration. Treatment must involve the partner.

Plateau and orgasmic dysfunctions

Delayed or absent orgasm is common. It may be primary or secondary, global, situational, or random. Etiologies include performance anxiety, fear of loss of control, and boredom. Patients with orgasmic dysfunction often develop “spectator” behavior. When they reach plateau they begin to wonder if they will have orgasm. They begin to watch to see what is happening rather than participating. As a result, they lose excitement and do not have orgasm. They become increasingly anxious about whether they will achieve orgasm. Anxiety interferes with the sexual response cycle, and orgasm does not occur.

Treatment involves sensate focus. By learning to focus on the sensations that occur, the patient learns not to focus on anxiety or assume the spectator frame of mind.

When the patient reports “no desire” but describes aversion behavior, inhibited desire is typically a conditioned response to the experience of pain during intercourse. Pain—from any cause—during sexual intercourse, can begin a conditioned response that requires recognition, treatment, and, often, counseling to eliminate.

How can the Ob/Gyn help? Therapy model: P LI SS IT

Permission giving. Many sexual problems can be solved by permission-giving. A patient might be bored and wish to try new positions; permission may be all that is required.

LImited information. A patient might have orgasm with masturbation but not penetration. Explaining to the patient that 50% of women do not have orgasm with penetration alone and that it is OK to combine manual stimulation with penetration may be all that is needed.

Specific Suggestions. A patient on decongestants may note decreased lubrication. Use of a lubricant might help. A patient with the “busy mother syndrome” may need specific instruction to make time for a relationship.

Intensive Therapy. Patients with childhood sexual abuse probably require intensive therapy. Vaginismus may require intensive therapy.

- 47 yo woman married to a physician for 23 years. No intercourse for 20 years, and no communication outside the bedroom about their sexual relationship. She is very angry. Her last gynecologist said she should get a good divorce attorney.

- 50 yo woman complains of no desire and lack of lubrication. Married for 20 years. She has insulin-dependent diabetes. Her last gynecologist told her to use KY jelly. She became very angry saying KY jelly was “too clinical.”

- 30 yo woman referred for severe dyspareunia and pelvic pain. Prior workup including IVP, ultrasound, and laparoscopy found no organic cause. She describes severe inhibited sexual desire and had not attempted intercourse in 4 months.

- 34 yo married woman complains of anorgasmia since starting fluoxetine (Prozac) 2 years ago. She had orgasm prior to that. After changing to bupropion (Wellbutrin), her anorgasmia continued.

Summary

Many gynecologists are concerned about lack of time or skills to deal with sexual problems. However, it often takes less time to deal with the problem than to ignore it. If a problem is uncovered during a scheduled brief visit, the patient can be given a follow-up appointment to ensure adequate time.

Dr. Carey is a member of the Female Sexual Dysfunction CME Steering Committee, sponsored by the University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey, through a grant from Proctor and Gamble.

1. Laumann EO, Paik A, Rosen RC. Sexual dysfunction in the United States: prevalence and predictors. JAMA. 1999;281:537-544.

2. Dunn KM, Croft PR, Hackett GI. Sexual problems: a study of the prevalence and need for health care in the general population. Fam Pract. 1998;15:519-524.

3. Bancroft J, Sherwin BB, Alexander GM, Davidson DW, Walker A. Oral contraceptives, androgens, and the sexuality of young women: II. The role of androgens. Arch Sex Behav. 1991;20:121-135.

4. Dennerstein L, Dudley EC, Hopper JL, Burger H. Sexuality, hormones and the menopausal transition. Maturitas. 1997;26:83-93.

5. Kirchengast S, Hartmann B, Gruber D, Huber J. Decreased sexual interest and its relationship to body build in postmenopausal women. Maturitas. 1996;23:63-71.

6. Schreiner-Engel P, Schiavi RC, White D, Ghizzani A. Low sexual desire in women: the role of reproductive hormones. Horm Behav. 1989;23:221-234.

7. Shifren JL, Braunstein GD, Simon JA, Casson PR, Buster JE, Redmond GP, et al. Transdermal testosterone treatment in women with impaired sexual function after oophorectomy. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:682-688.

Case reports of patients helped by therapy,

Say you see 100 adult patients this week. How many have a sexual dysfunction? 10? 20? Would you believe 43? In a National Health and Social Life Survey1 of 1,749 women and 1,410 men aged 18 to 59 years, 43% of women and 31% of men reported sexual dysfunction. Rates that high make sexual dysfunction an important public health concern—one that is highly associated with impaired well-being and negative experiences in sexual relationships.

Similar findings marked a study2 of general practice patients in Britain: 41% of 979 women and 34% of 789 men reported sexual dysfunction. Although 52% wanted professional help, only 10% had received it.

As primary care providers, Ob/Gyns must identify common problems, treat those within our expertise, and refer the others. In all likelihood, we are the first physicians women see about a sexual problem. For these reasons—and because dysfunction is so common—it is appropriate that we screen for and address female sexual dysfunction.

This article presents a medical model of management and tells how to take a sexual history, formulate a differential diagnosis, manage common sexual problems, and identify indications for referral.

The medical model

According to the medical model, a patient presents with a problem, which is investigated by history and physical examination. A differential diagnosis is formulated, and appropriate laboratory tests or other evaluations are conducted. The patient’s problem is compared to a normal physiologic process to determine pathophysiology. Diagnosis and therapy follow.

The medical model for sexual dysfunction is the same as that for any disease, such as asthma, in which normal breathing is interrupted. In the sexual response cycle, physiologic changes can be measured and specifically described, as Masters and Johnson explained in 1966 in Human Sexual Response (FIGURE 1). Any barriers that interrupt this progression “block” the normal response cycle, resulting in sexual dysfunction. We aim to identify and remove or get around any barriers.

FIGURE 1 Use the sexual response cycle in dialogue with the patient

Most patients with sexual dysfunction can identify the phase in the Masters and Johnson sexual response cycle where normal progression is interrupted. Using a sketch of this cycle helps patients understand and articulate their problem.

The sexual response cycle

Desire initiates the cycle, followed by the excitement phase, during which breathing rate and pulse increase, blood flow shifts away from muscles and into the skin and pelvic organs, and there is an associated expansion, lengthening, and lubrication of the vagina. A plateau follows, during which there is no further increase in signs such as increased pulse rate. Orgasm is the first point in the response cycle that is different in men and women. Men have an obligatory resolution phase and return to baseline state; women can return to the plateau state and then have another orgasm. The resolution phase lengthens in duration in both sexes with increasing age.

The sexual response cycle is innate, like any physiologic process. It cannot be taught or learned, and is not under voluntary control. It is critical that patients understand that the sexual response cycle is a natural function that everyone has—just as everyone has innate capacity to breathe. Patients do not learn it, any more than they have to learn respiration.

Sexual behavior, however, is learned, and sexual dysfunctions are exhibited by behavior. Sex therapy is a learning process, the aim of which is to change the behavior. Sexual dysfunctions have both cognitive and physical components; although response is physiologic, it can be altered by emotion, as can respiration.

The relationship is the patient. Sexual dysfunction occurs within a relationship, and the relationship needs and stands to benefit from therapy.

Reassuring anxious, angry patients

Approach is critical, and must reflect an understanding that sexual dysfunction is real. Many patients have been told that the problem is “all in their head” or that they are deliberately acting dysfunctionally.

Confrontation and support are useful communication tools. Confrontation means identifying behaviors and beliefs and how beliefs influence behaviors. Support means conveying to the patient that you understand that she is in distress and that it couldn’t have happened any other way for her.

A “therapeutic mirror” technique can show the patient her beliefs, attitudes, and behaviors. The therapist repeats the the patient’s beliefs and behaviors until the patient states that they are an accurate reflection, or tells the therapist what is inaccurate.

Assure the patient that anxiety is to be expected, and that her probelm is common and treatable. These patients believe they have thought of everything, and nothing has worked. Just reassuring them may help.

Anger must also be acknowledged—and these patients are angry. Their anger may be directed at their partner, a former physician, or you. You may elicit a surprising outburst of pent-up anger when you ask what seems to be a neutral question.

The patient always has an internal theory and everything you say is filtered through this theory. If there is a dichotomy, it must be addressed before you can proceed successfully. Usually, you can simply ask, “What do you think is the cause?” Often she will tell you. If she is uncertain, you might say, “I realize you don’t really know. What do you think it might be? What are you afraid it might be?”

You have to ask

Many patients do not express the fact that their chief complaint is sexual dysfunction. (See How to take a sexual history,).

In many cases, sexual dysfunction may be suggested in the investigation of another complaint such as infertility, pelvic pain with no particular pattern, malaise, or depression. With these complaints, it is important to pursue a sexual history. Determine any associated or causal condition and look for associated dysfunction.

The sexual history is like a history for any disease, in that you begin with the present illness. The differential diagnosis begins with a determination of where in the cycle the dysfunction occurs.

- One way to start is to describe the normal human sexual response. I find it best to sketch out the response cycle (FIGURE 1 ) on a piece of paper and ask, “Is this what happens to you?” Most patients understand and can tell where in the cycle the interruption occurs.

- 3 questions in a review of systems disclose nearly all sexual dysfunction:

- “How often do you have intercourse?” The only “right” answer is “as often as I want to.” If the patient is not having intercourse, is it by choice or involuntary?

- “Do you have pain with intercourse?”

- “How often do you have orgasm?” Most answer “hardly ever” or “most of the time.”

- Allegories like these are useful:

- Elements and example questions

Physical examination

Ageneral physical examination with pelvic examination should always be performed. If the patient complains of pain, the site of pain should be determined. A wet prep is useful to exclude vaginitis. A patient may have dyspareunia from vaginitis even if there are no obvious physical signs.

The most common dysfunctions: Desire phase disorders

Female sexual arousal disorder is either low libido or inhibited sexual desire. In both cases the patient is likely to report that she has no desire. But if you ask what happens when her partner wants to have intercourse, a patient with low libido describes low interest behavior, and a patient with inhibited desire describes aversion behavior.

Patients with low libido sometimes report that their orgasms are less intense, or that they do not become excited. Women on estrogen replacement after oophorectomy may have low libido related to decreased androgen.

Depression is by far the most common cause. Other contributors: chronic disease, hypoestrogenic states, hyperprolactinemia, and breastfeeding.

Inhibited sexual desire, which is a result of pain or other dysfunction, is far more common than low libido. Careful history usually reveals aversion behavior. They avoid going to bed at the same time as their partner, or develop other behaviors that preclude intercourse.

Women with inhibited desire have a conditioned negative response. In studies, these patients exhibit normal objective measures of vaginal vasocongestion in response to sexual stimuli, but self-reported subjective measures of arousal do not correlate.

They report that they simply have no desire, but the cause of their avoidance is negative conditioning. Here’s where the therapist supports, but also confronts their belief system, and attempts to help them understand that they have a normal desire for intercourse. The therapist may ask the patient to consider whether she ever has sexual dreams, reads romance novels, or fantasizes, to show that these phenomena demonstrate normal desire.

The role of testosterone in inhibited sexual desire

Measuring serum testosterone isn’t helpful. It is my belief that inhibited desire is most often related to other factors. Counseling should be the first-line therapy. Drug therapy without counseling is less likely to be effective than therapy that includes counseling.

Normal serum testosterone levels are 20 to 80 ng/dL in reproductive-age women, who produce 0.2 to 0.3 mg/day of testosterone. Levels increase 10% to 20% at midcycle. Testosterone falls 40% to 60% at natural menopause and by similar amounts with use of oral contraceptive pills, and by 80% with surgical menopause.

Testosterone levels have little correlation with sexual desire in cycling women or women on oral contraceptives.3 Most studies have found no correlation between testosterone levels and sexual function in perimenopausal or naturally menopausal women.4,5 Other studies have failed to show a difference in testosterone levels between women with arousal disorders and normal controls.6

Testosterone therapy may be effective in surgically menopausal women with low libido. Shifrin and colleagues7 randomized 75 surgically menopausal women being treated with conjugated equine estrogens to placebo or transdermal testosterone, 150 or 300 μg per day, in a crossover trial. They reported, “Despite an appreciable placebo response, the higher testosterone dose resulted in further increases in scores for frequency of sexual activity and pleasure-orgasm. At the higher dose, the percentages of women who had sexual fantasies, masturbated, or engaged in sexual intercourse at least once a week increased 2 to 3 times from base line.”

Testosterone is not yet approved for female sexual dysfunction, but a transdermal testosterone is being proposed for women with hypoactive sexual desire disorder who have had bilateral oophorectomy.

Excitement phase disorders

These disorders are caused by pain with intercourse. What the patient says about the site of pain and when she began experiencing pain help form the differential diagnosis.

Dyspareunia can be due to physiological causes such as obstetric laceration, endometriosis, pelvic inflammatory disease, vaginitis, vulvar disease, and vestibulitis. Interstitial cystitis and inflammatory bowel disease can cause dyspareunia, as can a simple fungal infection. Ask how long the pain continues after intercourse. If internal pain continues for hours, it is highly suggestive of intra-abdominal pathology.

Any cause of pain can begin a self-perpetuating conditioned response cycle that leads to inhibited desire. Anything that causes pain elicits aversion behavior, even without the stimulus. With conditioned response comes failure of excitement, which is where the sexual response cycle is interrupted.

When pain interrupts the sexual response cycle, the patient may still have intercourse, but without excitement, lubrication, and vaginal expansion—and with consequent further pain. Further attempts at intercourse then cause more pain, leading to the cycle of dyspareunia. Pain may be introital, vaginal, or deep. The pain may be reproduced on exam.

Treatment is twofold. Identify and correct source of pain first. Then the patient must learn that intercourse is not painful but pleasurable. Sensate focus exercises are often useful.

Vaginismus, an involuntary spasm of muscles around the outer third of the vagina, may make penetration impossible. Vaginismus can be caused by pain, severe negative parental attitudes about sex, or extreme religious orthodoxy. These patients may be hyper-feminine. They often have bizarre mental images of their genitals. They usually have a partner who supports the dysfunction.

Treatment involves dilators, but the purpose is not to dilate the vagina. It is to learn to have something in the vagina and to confront fears and feelings rregarding penetration. Treatment must involve the partner.

Plateau and orgasmic dysfunctions

Delayed or absent orgasm is common. It may be primary or secondary, global, situational, or random. Etiologies include performance anxiety, fear of loss of control, and boredom. Patients with orgasmic dysfunction often develop “spectator” behavior. When they reach plateau they begin to wonder if they will have orgasm. They begin to watch to see what is happening rather than participating. As a result, they lose excitement and do not have orgasm. They become increasingly anxious about whether they will achieve orgasm. Anxiety interferes with the sexual response cycle, and orgasm does not occur.

Treatment involves sensate focus. By learning to focus on the sensations that occur, the patient learns not to focus on anxiety or assume the spectator frame of mind.

When the patient reports “no desire” but describes aversion behavior, inhibited desire is typically a conditioned response to the experience of pain during intercourse. Pain—from any cause—during sexual intercourse, can begin a conditioned response that requires recognition, treatment, and, often, counseling to eliminate.

How can the Ob/Gyn help? Therapy model: P LI SS IT

Permission giving. Many sexual problems can be solved by permission-giving. A patient might be bored and wish to try new positions; permission may be all that is required.

LImited information. A patient might have orgasm with masturbation but not penetration. Explaining to the patient that 50% of women do not have orgasm with penetration alone and that it is OK to combine manual stimulation with penetration may be all that is needed.

Specific Suggestions. A patient on decongestants may note decreased lubrication. Use of a lubricant might help. A patient with the “busy mother syndrome” may need specific instruction to make time for a relationship.

Intensive Therapy. Patients with childhood sexual abuse probably require intensive therapy. Vaginismus may require intensive therapy.

- 47 yo woman married to a physician for 23 years. No intercourse for 20 years, and no communication outside the bedroom about their sexual relationship. She is very angry. Her last gynecologist said she should get a good divorce attorney.

- 50 yo woman complains of no desire and lack of lubrication. Married for 20 years. She has insulin-dependent diabetes. Her last gynecologist told her to use KY jelly. She became very angry saying KY jelly was “too clinical.”

- 30 yo woman referred for severe dyspareunia and pelvic pain. Prior workup including IVP, ultrasound, and laparoscopy found no organic cause. She describes severe inhibited sexual desire and had not attempted intercourse in 4 months.

- 34 yo married woman complains of anorgasmia since starting fluoxetine (Prozac) 2 years ago. She had orgasm prior to that. After changing to bupropion (Wellbutrin), her anorgasmia continued.

Summary

Many gynecologists are concerned about lack of time or skills to deal with sexual problems. However, it often takes less time to deal with the problem than to ignore it. If a problem is uncovered during a scheduled brief visit, the patient can be given a follow-up appointment to ensure adequate time.

Dr. Carey is a member of the Female Sexual Dysfunction CME Steering Committee, sponsored by the University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey, through a grant from Proctor and Gamble.

Case reports of patients helped by therapy,

Say you see 100 adult patients this week. How many have a sexual dysfunction? 10? 20? Would you believe 43? In a National Health and Social Life Survey1 of 1,749 women and 1,410 men aged 18 to 59 years, 43% of women and 31% of men reported sexual dysfunction. Rates that high make sexual dysfunction an important public health concern—one that is highly associated with impaired well-being and negative experiences in sexual relationships.

Similar findings marked a study2 of general practice patients in Britain: 41% of 979 women and 34% of 789 men reported sexual dysfunction. Although 52% wanted professional help, only 10% had received it.

As primary care providers, Ob/Gyns must identify common problems, treat those within our expertise, and refer the others. In all likelihood, we are the first physicians women see about a sexual problem. For these reasons—and because dysfunction is so common—it is appropriate that we screen for and address female sexual dysfunction.

This article presents a medical model of management and tells how to take a sexual history, formulate a differential diagnosis, manage common sexual problems, and identify indications for referral.

The medical model

According to the medical model, a patient presents with a problem, which is investigated by history and physical examination. A differential diagnosis is formulated, and appropriate laboratory tests or other evaluations are conducted. The patient’s problem is compared to a normal physiologic process to determine pathophysiology. Diagnosis and therapy follow.

The medical model for sexual dysfunction is the same as that for any disease, such as asthma, in which normal breathing is interrupted. In the sexual response cycle, physiologic changes can be measured and specifically described, as Masters and Johnson explained in 1966 in Human Sexual Response (FIGURE 1). Any barriers that interrupt this progression “block” the normal response cycle, resulting in sexual dysfunction. We aim to identify and remove or get around any barriers.

FIGURE 1 Use the sexual response cycle in dialogue with the patient

Most patients with sexual dysfunction can identify the phase in the Masters and Johnson sexual response cycle where normal progression is interrupted. Using a sketch of this cycle helps patients understand and articulate their problem.

The sexual response cycle

Desire initiates the cycle, followed by the excitement phase, during which breathing rate and pulse increase, blood flow shifts away from muscles and into the skin and pelvic organs, and there is an associated expansion, lengthening, and lubrication of the vagina. A plateau follows, during which there is no further increase in signs such as increased pulse rate. Orgasm is the first point in the response cycle that is different in men and women. Men have an obligatory resolution phase and return to baseline state; women can return to the plateau state and then have another orgasm. The resolution phase lengthens in duration in both sexes with increasing age.

The sexual response cycle is innate, like any physiologic process. It cannot be taught or learned, and is not under voluntary control. It is critical that patients understand that the sexual response cycle is a natural function that everyone has—just as everyone has innate capacity to breathe. Patients do not learn it, any more than they have to learn respiration.

Sexual behavior, however, is learned, and sexual dysfunctions are exhibited by behavior. Sex therapy is a learning process, the aim of which is to change the behavior. Sexual dysfunctions have both cognitive and physical components; although response is physiologic, it can be altered by emotion, as can respiration.

The relationship is the patient. Sexual dysfunction occurs within a relationship, and the relationship needs and stands to benefit from therapy.

Reassuring anxious, angry patients

Approach is critical, and must reflect an understanding that sexual dysfunction is real. Many patients have been told that the problem is “all in their head” or that they are deliberately acting dysfunctionally.

Confrontation and support are useful communication tools. Confrontation means identifying behaviors and beliefs and how beliefs influence behaviors. Support means conveying to the patient that you understand that she is in distress and that it couldn’t have happened any other way for her.

A “therapeutic mirror” technique can show the patient her beliefs, attitudes, and behaviors. The therapist repeats the the patient’s beliefs and behaviors until the patient states that they are an accurate reflection, or tells the therapist what is inaccurate.

Assure the patient that anxiety is to be expected, and that her probelm is common and treatable. These patients believe they have thought of everything, and nothing has worked. Just reassuring them may help.

Anger must also be acknowledged—and these patients are angry. Their anger may be directed at their partner, a former physician, or you. You may elicit a surprising outburst of pent-up anger when you ask what seems to be a neutral question.

The patient always has an internal theory and everything you say is filtered through this theory. If there is a dichotomy, it must be addressed before you can proceed successfully. Usually, you can simply ask, “What do you think is the cause?” Often she will tell you. If she is uncertain, you might say, “I realize you don’t really know. What do you think it might be? What are you afraid it might be?”

You have to ask

Many patients do not express the fact that their chief complaint is sexual dysfunction. (See How to take a sexual history,).

In many cases, sexual dysfunction may be suggested in the investigation of another complaint such as infertility, pelvic pain with no particular pattern, malaise, or depression. With these complaints, it is important to pursue a sexual history. Determine any associated or causal condition and look for associated dysfunction.

The sexual history is like a history for any disease, in that you begin with the present illness. The differential diagnosis begins with a determination of where in the cycle the dysfunction occurs.

- One way to start is to describe the normal human sexual response. I find it best to sketch out the response cycle (FIGURE 1 ) on a piece of paper and ask, “Is this what happens to you?” Most patients understand and can tell where in the cycle the interruption occurs.

- 3 questions in a review of systems disclose nearly all sexual dysfunction:

- “How often do you have intercourse?” The only “right” answer is “as often as I want to.” If the patient is not having intercourse, is it by choice or involuntary?

- “Do you have pain with intercourse?”

- “How often do you have orgasm?” Most answer “hardly ever” or “most of the time.”

- Allegories like these are useful:

- Elements and example questions

Physical examination

Ageneral physical examination with pelvic examination should always be performed. If the patient complains of pain, the site of pain should be determined. A wet prep is useful to exclude vaginitis. A patient may have dyspareunia from vaginitis even if there are no obvious physical signs.

The most common dysfunctions: Desire phase disorders

Female sexual arousal disorder is either low libido or inhibited sexual desire. In both cases the patient is likely to report that she has no desire. But if you ask what happens when her partner wants to have intercourse, a patient with low libido describes low interest behavior, and a patient with inhibited desire describes aversion behavior.

Patients with low libido sometimes report that their orgasms are less intense, or that they do not become excited. Women on estrogen replacement after oophorectomy may have low libido related to decreased androgen.

Depression is by far the most common cause. Other contributors: chronic disease, hypoestrogenic states, hyperprolactinemia, and breastfeeding.

Inhibited sexual desire, which is a result of pain or other dysfunction, is far more common than low libido. Careful history usually reveals aversion behavior. They avoid going to bed at the same time as their partner, or develop other behaviors that preclude intercourse.

Women with inhibited desire have a conditioned negative response. In studies, these patients exhibit normal objective measures of vaginal vasocongestion in response to sexual stimuli, but self-reported subjective measures of arousal do not correlate.

They report that they simply have no desire, but the cause of their avoidance is negative conditioning. Here’s where the therapist supports, but also confronts their belief system, and attempts to help them understand that they have a normal desire for intercourse. The therapist may ask the patient to consider whether she ever has sexual dreams, reads romance novels, or fantasizes, to show that these phenomena demonstrate normal desire.

The role of testosterone in inhibited sexual desire

Measuring serum testosterone isn’t helpful. It is my belief that inhibited desire is most often related to other factors. Counseling should be the first-line therapy. Drug therapy without counseling is less likely to be effective than therapy that includes counseling.

Normal serum testosterone levels are 20 to 80 ng/dL in reproductive-age women, who produce 0.2 to 0.3 mg/day of testosterone. Levels increase 10% to 20% at midcycle. Testosterone falls 40% to 60% at natural menopause and by similar amounts with use of oral contraceptive pills, and by 80% with surgical menopause.

Testosterone levels have little correlation with sexual desire in cycling women or women on oral contraceptives.3 Most studies have found no correlation between testosterone levels and sexual function in perimenopausal or naturally menopausal women.4,5 Other studies have failed to show a difference in testosterone levels between women with arousal disorders and normal controls.6

Testosterone therapy may be effective in surgically menopausal women with low libido. Shifrin and colleagues7 randomized 75 surgically menopausal women being treated with conjugated equine estrogens to placebo or transdermal testosterone, 150 or 300 μg per day, in a crossover trial. They reported, “Despite an appreciable placebo response, the higher testosterone dose resulted in further increases in scores for frequency of sexual activity and pleasure-orgasm. At the higher dose, the percentages of women who had sexual fantasies, masturbated, or engaged in sexual intercourse at least once a week increased 2 to 3 times from base line.”

Testosterone is not yet approved for female sexual dysfunction, but a transdermal testosterone is being proposed for women with hypoactive sexual desire disorder who have had bilateral oophorectomy.

Excitement phase disorders

These disorders are caused by pain with intercourse. What the patient says about the site of pain and when she began experiencing pain help form the differential diagnosis.

Dyspareunia can be due to physiological causes such as obstetric laceration, endometriosis, pelvic inflammatory disease, vaginitis, vulvar disease, and vestibulitis. Interstitial cystitis and inflammatory bowel disease can cause dyspareunia, as can a simple fungal infection. Ask how long the pain continues after intercourse. If internal pain continues for hours, it is highly suggestive of intra-abdominal pathology.

Any cause of pain can begin a self-perpetuating conditioned response cycle that leads to inhibited desire. Anything that causes pain elicits aversion behavior, even without the stimulus. With conditioned response comes failure of excitement, which is where the sexual response cycle is interrupted.

When pain interrupts the sexual response cycle, the patient may still have intercourse, but without excitement, lubrication, and vaginal expansion—and with consequent further pain. Further attempts at intercourse then cause more pain, leading to the cycle of dyspareunia. Pain may be introital, vaginal, or deep. The pain may be reproduced on exam.

Treatment is twofold. Identify and correct source of pain first. Then the patient must learn that intercourse is not painful but pleasurable. Sensate focus exercises are often useful.

Vaginismus, an involuntary spasm of muscles around the outer third of the vagina, may make penetration impossible. Vaginismus can be caused by pain, severe negative parental attitudes about sex, or extreme religious orthodoxy. These patients may be hyper-feminine. They often have bizarre mental images of their genitals. They usually have a partner who supports the dysfunction.

Treatment involves dilators, but the purpose is not to dilate the vagina. It is to learn to have something in the vagina and to confront fears and feelings rregarding penetration. Treatment must involve the partner.

Plateau and orgasmic dysfunctions

Delayed or absent orgasm is common. It may be primary or secondary, global, situational, or random. Etiologies include performance anxiety, fear of loss of control, and boredom. Patients with orgasmic dysfunction often develop “spectator” behavior. When they reach plateau they begin to wonder if they will have orgasm. They begin to watch to see what is happening rather than participating. As a result, they lose excitement and do not have orgasm. They become increasingly anxious about whether they will achieve orgasm. Anxiety interferes with the sexual response cycle, and orgasm does not occur.

Treatment involves sensate focus. By learning to focus on the sensations that occur, the patient learns not to focus on anxiety or assume the spectator frame of mind.

When the patient reports “no desire” but describes aversion behavior, inhibited desire is typically a conditioned response to the experience of pain during intercourse. Pain—from any cause—during sexual intercourse, can begin a conditioned response that requires recognition, treatment, and, often, counseling to eliminate.

How can the Ob/Gyn help? Therapy model: P LI SS IT

Permission giving. Many sexual problems can be solved by permission-giving. A patient might be bored and wish to try new positions; permission may be all that is required.

LImited information. A patient might have orgasm with masturbation but not penetration. Explaining to the patient that 50% of women do not have orgasm with penetration alone and that it is OK to combine manual stimulation with penetration may be all that is needed.

Specific Suggestions. A patient on decongestants may note decreased lubrication. Use of a lubricant might help. A patient with the “busy mother syndrome” may need specific instruction to make time for a relationship.

Intensive Therapy. Patients with childhood sexual abuse probably require intensive therapy. Vaginismus may require intensive therapy.

- 47 yo woman married to a physician for 23 years. No intercourse for 20 years, and no communication outside the bedroom about their sexual relationship. She is very angry. Her last gynecologist said she should get a good divorce attorney.

- 50 yo woman complains of no desire and lack of lubrication. Married for 20 years. She has insulin-dependent diabetes. Her last gynecologist told her to use KY jelly. She became very angry saying KY jelly was “too clinical.”

- 30 yo woman referred for severe dyspareunia and pelvic pain. Prior workup including IVP, ultrasound, and laparoscopy found no organic cause. She describes severe inhibited sexual desire and had not attempted intercourse in 4 months.

- 34 yo married woman complains of anorgasmia since starting fluoxetine (Prozac) 2 years ago. She had orgasm prior to that. After changing to bupropion (Wellbutrin), her anorgasmia continued.

Summary

Many gynecologists are concerned about lack of time or skills to deal with sexual problems. However, it often takes less time to deal with the problem than to ignore it. If a problem is uncovered during a scheduled brief visit, the patient can be given a follow-up appointment to ensure adequate time.

Dr. Carey is a member of the Female Sexual Dysfunction CME Steering Committee, sponsored by the University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey, through a grant from Proctor and Gamble.

1. Laumann EO, Paik A, Rosen RC. Sexual dysfunction in the United States: prevalence and predictors. JAMA. 1999;281:537-544.

2. Dunn KM, Croft PR, Hackett GI. Sexual problems: a study of the prevalence and need for health care in the general population. Fam Pract. 1998;15:519-524.

3. Bancroft J, Sherwin BB, Alexander GM, Davidson DW, Walker A. Oral contraceptives, androgens, and the sexuality of young women: II. The role of androgens. Arch Sex Behav. 1991;20:121-135.

4. Dennerstein L, Dudley EC, Hopper JL, Burger H. Sexuality, hormones and the menopausal transition. Maturitas. 1997;26:83-93.

5. Kirchengast S, Hartmann B, Gruber D, Huber J. Decreased sexual interest and its relationship to body build in postmenopausal women. Maturitas. 1996;23:63-71.

6. Schreiner-Engel P, Schiavi RC, White D, Ghizzani A. Low sexual desire in women: the role of reproductive hormones. Horm Behav. 1989;23:221-234.

7. Shifren JL, Braunstein GD, Simon JA, Casson PR, Buster JE, Redmond GP, et al. Transdermal testosterone treatment in women with impaired sexual function after oophorectomy. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:682-688.

1. Laumann EO, Paik A, Rosen RC. Sexual dysfunction in the United States: prevalence and predictors. JAMA. 1999;281:537-544.

2. Dunn KM, Croft PR, Hackett GI. Sexual problems: a study of the prevalence and need for health care in the general population. Fam Pract. 1998;15:519-524.

3. Bancroft J, Sherwin BB, Alexander GM, Davidson DW, Walker A. Oral contraceptives, androgens, and the sexuality of young women: II. The role of androgens. Arch Sex Behav. 1991;20:121-135.

4. Dennerstein L, Dudley EC, Hopper JL, Burger H. Sexuality, hormones and the menopausal transition. Maturitas. 1997;26:83-93.

5. Kirchengast S, Hartmann B, Gruber D, Huber J. Decreased sexual interest and its relationship to body build in postmenopausal women. Maturitas. 1996;23:63-71.

6. Schreiner-Engel P, Schiavi RC, White D, Ghizzani A. Low sexual desire in women: the role of reproductive hormones. Horm Behav. 1989;23:221-234.

7. Shifren JL, Braunstein GD, Simon JA, Casson PR, Buster JE, Redmond GP, et al. Transdermal testosterone treatment in women with impaired sexual function after oophorectomy. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:682-688.