User login

Carol Pohlig is a billing and coding expert with the University of Pennsylvania Medical Center, Philadelphia. She is also on the faculty of SHM’s inpatient coding course.

Document Your Decisions

For all the differences highlighted in my April and May columns studying the 1995 and 1997 documentation guidelines set forth by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) and the American Medical Association (AMA), decision making remains consistent in both.

Physician documentation addresses the complexity of the patient’s condition in terms of the number of diagnoses and/or treatment options, the amount and/or complexity of data ordered/reviewed, and the risk of complications/morbidity/mortality. The “diagnoses” and “data” categories follow a point system (see Table 1, below) determined by local Medicare contractors, whereas the “risk” category utilizes a universal table to define medical and/or procedural risks for the patient. The final result of complexity is classified as straightforward, low, moderate, or high.

A complete and accurate description of the patient’s condition should be conveyed through the plan of care. While acuity and severity may be inferred by a physician’s colleagues from particular pieces of information included in the record (e.g., critical lab values), the importance of this information may be lost on auditors and medical record reviewers. This article will assist in explaining the categories of medical decision making, as well as provide documentation tips to best represent patient complexity.

Diagnoses, Care Options

The plan of care outlines problems the physician personally manages and those that affect their management options, even if another physician directly oversees the problem. For example, the hospitalist may primarily manage a patient’s diabetes while the nephrologist manages renal insufficiency. Since the renal insufficiency may affect the hospitalist’s plan for diabetic management, the hospitalist receives credit for the documented renal insufficiency diagnosis and hospitalist-related care plan.

Physicians should address all problems in the documentation for each encounter regardless of any changes to the treatment plan. Credit is provided for each problem that has an associated plan, even if the plan states “continue same treatment.” Additional credit is provided when the treatment to be “continued” is referenced somewhere in the progress note (e.g., in the history).

The amount of credit varies depending upon the problem type. An established problem, defined as having a care plan established by the physician or someone from the same group practice during the current hospitalization, is considered less complex than an undiagnosed new problem for which a prognosis cannot be determined. Severity of the problem affects the weight of complexity. A stable, improving problem is not as complex as a progressing problem.

When documenting diagnoses/treatment options:

- Identify all problems managed or addressed during each encounter;

- Identify problems as stable or progressing, when appropriate;

- Indicate differential diagnoses when the problem remains undefined; and

- Indicate the management/treatment option(s) for each problem.

When documentation indicates a continuation of current management options (e.g., “continue meds”), be sure the management options to be continued are noted somewhere in the progress note for that encounter (e.g., medication list).

Data Ordered/Reviewed

“Data” order/review comes in many forms: pathology/laboratory testing, radiology, and medicine-based diagnostics. Although an intuitive part of medical practice, the data section of the progress note is often underdocumented by physicians. Pertinent orders or results may be noted in the visit record, but most of the background interactions and communications involving testing are undetected when reviewing the progress note.

When documenting amount and/or complexity of data:

- Specify tests ordered and rationale in the physician’s progress note or make an entry that refers to another auditor-accessible location for ordered tests and studies;

- Test review may be documented by including a brief entry in the progress note (e.g., “decreased Hgb” or “CXR shows NAD”), or by dating and initialing the report;

- Physicians receive credit for reviewing old records or obtaining history from someone other than the patient, when necessary, as long as a summary of the review or discussion is documented in the medical record; and

- Indicate when images, tracings, or specimens are “personally reviewed” by the physician.

Discussion of unexpected or contradictory test results with the performing physician should be summarized in the medical record.

Risks of Complication

Risk is viewed in light of the patient’s presenting problem, diagnostic procedures ordered, and management options selected.

Risk is graded as minimal, low, moderate, and high with corresponding items that help to differentiate each level (see Table 2, right). The single highest item in any given risk category determines the risk level.

Chronic conditions and invasive procedures expose the patient to more risk than acute, uncomplicated illnesses or non-invasive procedures, respectively. As in the diagnoses/treatment options category, a stable or improving problem poses less risk than a progressing problem. Medication risk varies with the type and degree of potential adverse effects associated with each medication.

When documenting risk:

- Indicate status of all problems in the plan of care; identify them as stable, worsening, exacerbating (mild or severe), etc.;

- Document all diagnostic procedures being considered;

- Identify surgical risk factors involving co-morbid conditions, when appropriate; and

- Associate the labs ordered to monitor for toxicity with the corresponding. medication (e.g., “Continue coumadin, monitor PT/INR”). A patient maintains the same level of risk for a given medication whether the dosage is increased, decreased, or continued without change.

Determine Complexity

To determine the final complexity of medical decision making, two of three categories must be met. For example, if a physician satisfies the requirements for “multiple” diagnoses/treatment options, “minimal” data, and “high” risk, the physician achieves moderate complexity decision-making.

Remember that decision-making is just one of three components of evaluation and management services, along with history and exam.

Determining the final visit level (e.g., 9922x) depends upon each of these three key components for initial hospital care and consultations, and two key components for subsequent hospital care. However, medical decision making always should drive visit level selection as it is the best representation of medical necessity for the service involved.

Contributory Factors

In addition to the three categories of medical decision making, a payer (e.g., TrailblazerHealth) may consider contributory factors when determining patient complexity and selecting visit levels.

For example, the nature of the presenting problem may play a role when reviewing claims for subsequent hospital care codes (99231-99233). Found in the code descriptors of the CPT manual, problems are identified as:

- 99231: Stable, recovering or improving;

- 99232: Responding inadequately to therapy or developed a minor complication; and

- 99233: Unstable or has developed a significant complication or a significant new problem.

Although this is not a general requirement, it represents a locally established standard for reviewing claims for medical necessity. It should not be used exclusively to determine the visit level.

Be sure to query your payer’s policy via written communication or Web site posting (e.g., www.trailblazerhealth.com/Publications/Job%20Aid/medical%20necessity.pdf) for guidance on how payers review documentation. TH

Carol Pohlig is a billing and coding expert with the University of Pennsylvania Medical Center, Philadelphia. She also is on the faculty of SHM’s inpatient coding course.

For all the differences highlighted in my April and May columns studying the 1995 and 1997 documentation guidelines set forth by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) and the American Medical Association (AMA), decision making remains consistent in both.

Physician documentation addresses the complexity of the patient’s condition in terms of the number of diagnoses and/or treatment options, the amount and/or complexity of data ordered/reviewed, and the risk of complications/morbidity/mortality. The “diagnoses” and “data” categories follow a point system (see Table 1, below) determined by local Medicare contractors, whereas the “risk” category utilizes a universal table to define medical and/or procedural risks for the patient. The final result of complexity is classified as straightforward, low, moderate, or high.

A complete and accurate description of the patient’s condition should be conveyed through the plan of care. While acuity and severity may be inferred by a physician’s colleagues from particular pieces of information included in the record (e.g., critical lab values), the importance of this information may be lost on auditors and medical record reviewers. This article will assist in explaining the categories of medical decision making, as well as provide documentation tips to best represent patient complexity.

Diagnoses, Care Options

The plan of care outlines problems the physician personally manages and those that affect their management options, even if another physician directly oversees the problem. For example, the hospitalist may primarily manage a patient’s diabetes while the nephrologist manages renal insufficiency. Since the renal insufficiency may affect the hospitalist’s plan for diabetic management, the hospitalist receives credit for the documented renal insufficiency diagnosis and hospitalist-related care plan.

Physicians should address all problems in the documentation for each encounter regardless of any changes to the treatment plan. Credit is provided for each problem that has an associated plan, even if the plan states “continue same treatment.” Additional credit is provided when the treatment to be “continued” is referenced somewhere in the progress note (e.g., in the history).

The amount of credit varies depending upon the problem type. An established problem, defined as having a care plan established by the physician or someone from the same group practice during the current hospitalization, is considered less complex than an undiagnosed new problem for which a prognosis cannot be determined. Severity of the problem affects the weight of complexity. A stable, improving problem is not as complex as a progressing problem.

When documenting diagnoses/treatment options:

- Identify all problems managed or addressed during each encounter;

- Identify problems as stable or progressing, when appropriate;

- Indicate differential diagnoses when the problem remains undefined; and

- Indicate the management/treatment option(s) for each problem.

When documentation indicates a continuation of current management options (e.g., “continue meds”), be sure the management options to be continued are noted somewhere in the progress note for that encounter (e.g., medication list).

Data Ordered/Reviewed

“Data” order/review comes in many forms: pathology/laboratory testing, radiology, and medicine-based diagnostics. Although an intuitive part of medical practice, the data section of the progress note is often underdocumented by physicians. Pertinent orders or results may be noted in the visit record, but most of the background interactions and communications involving testing are undetected when reviewing the progress note.

When documenting amount and/or complexity of data:

- Specify tests ordered and rationale in the physician’s progress note or make an entry that refers to another auditor-accessible location for ordered tests and studies;

- Test review may be documented by including a brief entry in the progress note (e.g., “decreased Hgb” or “CXR shows NAD”), or by dating and initialing the report;

- Physicians receive credit for reviewing old records or obtaining history from someone other than the patient, when necessary, as long as a summary of the review or discussion is documented in the medical record; and

- Indicate when images, tracings, or specimens are “personally reviewed” by the physician.

Discussion of unexpected or contradictory test results with the performing physician should be summarized in the medical record.

Risks of Complication

Risk is viewed in light of the patient’s presenting problem, diagnostic procedures ordered, and management options selected.

Risk is graded as minimal, low, moderate, and high with corresponding items that help to differentiate each level (see Table 2, right). The single highest item in any given risk category determines the risk level.

Chronic conditions and invasive procedures expose the patient to more risk than acute, uncomplicated illnesses or non-invasive procedures, respectively. As in the diagnoses/treatment options category, a stable or improving problem poses less risk than a progressing problem. Medication risk varies with the type and degree of potential adverse effects associated with each medication.

When documenting risk:

- Indicate status of all problems in the plan of care; identify them as stable, worsening, exacerbating (mild or severe), etc.;

- Document all diagnostic procedures being considered;

- Identify surgical risk factors involving co-morbid conditions, when appropriate; and

- Associate the labs ordered to monitor for toxicity with the corresponding. medication (e.g., “Continue coumadin, monitor PT/INR”). A patient maintains the same level of risk for a given medication whether the dosage is increased, decreased, or continued without change.

Determine Complexity

To determine the final complexity of medical decision making, two of three categories must be met. For example, if a physician satisfies the requirements for “multiple” diagnoses/treatment options, “minimal” data, and “high” risk, the physician achieves moderate complexity decision-making.

Remember that decision-making is just one of three components of evaluation and management services, along with history and exam.

Determining the final visit level (e.g., 9922x) depends upon each of these three key components for initial hospital care and consultations, and two key components for subsequent hospital care. However, medical decision making always should drive visit level selection as it is the best representation of medical necessity for the service involved.

Contributory Factors

In addition to the three categories of medical decision making, a payer (e.g., TrailblazerHealth) may consider contributory factors when determining patient complexity and selecting visit levels.

For example, the nature of the presenting problem may play a role when reviewing claims for subsequent hospital care codes (99231-99233). Found in the code descriptors of the CPT manual, problems are identified as:

- 99231: Stable, recovering or improving;

- 99232: Responding inadequately to therapy or developed a minor complication; and

- 99233: Unstable or has developed a significant complication or a significant new problem.

Although this is not a general requirement, it represents a locally established standard for reviewing claims for medical necessity. It should not be used exclusively to determine the visit level.

Be sure to query your payer’s policy via written communication or Web site posting (e.g., www.trailblazerhealth.com/Publications/Job%20Aid/medical%20necessity.pdf) for guidance on how payers review documentation. TH

Carol Pohlig is a billing and coding expert with the University of Pennsylvania Medical Center, Philadelphia. She also is on the faculty of SHM’s inpatient coding course.

For all the differences highlighted in my April and May columns studying the 1995 and 1997 documentation guidelines set forth by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) and the American Medical Association (AMA), decision making remains consistent in both.

Physician documentation addresses the complexity of the patient’s condition in terms of the number of diagnoses and/or treatment options, the amount and/or complexity of data ordered/reviewed, and the risk of complications/morbidity/mortality. The “diagnoses” and “data” categories follow a point system (see Table 1, below) determined by local Medicare contractors, whereas the “risk” category utilizes a universal table to define medical and/or procedural risks for the patient. The final result of complexity is classified as straightforward, low, moderate, or high.

A complete and accurate description of the patient’s condition should be conveyed through the plan of care. While acuity and severity may be inferred by a physician’s colleagues from particular pieces of information included in the record (e.g., critical lab values), the importance of this information may be lost on auditors and medical record reviewers. This article will assist in explaining the categories of medical decision making, as well as provide documentation tips to best represent patient complexity.

Diagnoses, Care Options

The plan of care outlines problems the physician personally manages and those that affect their management options, even if another physician directly oversees the problem. For example, the hospitalist may primarily manage a patient’s diabetes while the nephrologist manages renal insufficiency. Since the renal insufficiency may affect the hospitalist’s plan for diabetic management, the hospitalist receives credit for the documented renal insufficiency diagnosis and hospitalist-related care plan.

Physicians should address all problems in the documentation for each encounter regardless of any changes to the treatment plan. Credit is provided for each problem that has an associated plan, even if the plan states “continue same treatment.” Additional credit is provided when the treatment to be “continued” is referenced somewhere in the progress note (e.g., in the history).

The amount of credit varies depending upon the problem type. An established problem, defined as having a care plan established by the physician or someone from the same group practice during the current hospitalization, is considered less complex than an undiagnosed new problem for which a prognosis cannot be determined. Severity of the problem affects the weight of complexity. A stable, improving problem is not as complex as a progressing problem.

When documenting diagnoses/treatment options:

- Identify all problems managed or addressed during each encounter;

- Identify problems as stable or progressing, when appropriate;

- Indicate differential diagnoses when the problem remains undefined; and

- Indicate the management/treatment option(s) for each problem.

When documentation indicates a continuation of current management options (e.g., “continue meds”), be sure the management options to be continued are noted somewhere in the progress note for that encounter (e.g., medication list).

Data Ordered/Reviewed

“Data” order/review comes in many forms: pathology/laboratory testing, radiology, and medicine-based diagnostics. Although an intuitive part of medical practice, the data section of the progress note is often underdocumented by physicians. Pertinent orders or results may be noted in the visit record, but most of the background interactions and communications involving testing are undetected when reviewing the progress note.

When documenting amount and/or complexity of data:

- Specify tests ordered and rationale in the physician’s progress note or make an entry that refers to another auditor-accessible location for ordered tests and studies;

- Test review may be documented by including a brief entry in the progress note (e.g., “decreased Hgb” or “CXR shows NAD”), or by dating and initialing the report;

- Physicians receive credit for reviewing old records or obtaining history from someone other than the patient, when necessary, as long as a summary of the review or discussion is documented in the medical record; and

- Indicate when images, tracings, or specimens are “personally reviewed” by the physician.

Discussion of unexpected or contradictory test results with the performing physician should be summarized in the medical record.

Risks of Complication

Risk is viewed in light of the patient’s presenting problem, diagnostic procedures ordered, and management options selected.

Risk is graded as minimal, low, moderate, and high with corresponding items that help to differentiate each level (see Table 2, right). The single highest item in any given risk category determines the risk level.

Chronic conditions and invasive procedures expose the patient to more risk than acute, uncomplicated illnesses or non-invasive procedures, respectively. As in the diagnoses/treatment options category, a stable or improving problem poses less risk than a progressing problem. Medication risk varies with the type and degree of potential adverse effects associated with each medication.

When documenting risk:

- Indicate status of all problems in the plan of care; identify them as stable, worsening, exacerbating (mild or severe), etc.;

- Document all diagnostic procedures being considered;

- Identify surgical risk factors involving co-morbid conditions, when appropriate; and

- Associate the labs ordered to monitor for toxicity with the corresponding. medication (e.g., “Continue coumadin, monitor PT/INR”). A patient maintains the same level of risk for a given medication whether the dosage is increased, decreased, or continued without change.

Determine Complexity

To determine the final complexity of medical decision making, two of three categories must be met. For example, if a physician satisfies the requirements for “multiple” diagnoses/treatment options, “minimal” data, and “high” risk, the physician achieves moderate complexity decision-making.

Remember that decision-making is just one of three components of evaluation and management services, along with history and exam.

Determining the final visit level (e.g., 9922x) depends upon each of these three key components for initial hospital care and consultations, and two key components for subsequent hospital care. However, medical decision making always should drive visit level selection as it is the best representation of medical necessity for the service involved.

Contributory Factors

In addition to the three categories of medical decision making, a payer (e.g., TrailblazerHealth) may consider contributory factors when determining patient complexity and selecting visit levels.

For example, the nature of the presenting problem may play a role when reviewing claims for subsequent hospital care codes (99231-99233). Found in the code descriptors of the CPT manual, problems are identified as:

- 99231: Stable, recovering or improving;

- 99232: Responding inadequately to therapy or developed a minor complication; and

- 99233: Unstable or has developed a significant complication or a significant new problem.

Although this is not a general requirement, it represents a locally established standard for reviewing claims for medical necessity. It should not be used exclusively to determine the visit level.

Be sure to query your payer’s policy via written communication or Web site posting (e.g., www.trailblazerhealth.com/Publications/Job%20Aid/medical%20necessity.pdf) for guidance on how payers review documentation. TH

Carol Pohlig is a billing and coding expert with the University of Pennsylvania Medical Center, Philadelphia. She also is on the faculty of SHM’s inpatient coding course.

Choose Your Exam Rules

Physicians only should perform patient examinations based upon the presenting problem and the standard of care. As mentioned in my previous column (April 2008, p. 21), the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) and the American Medical Association (AMA) set forth two sets of documentation guidelines. The biggest difference between them is the exam component.

1995 Guidelines

The 1995 guidelines distinguish 10 body areas (head and face; neck; chest, breast, and axillae; abdomen; genitalia, groin, and buttocks; back and spine; right upper extremity; left upper extremity; right lower extremity; and left lower extremity) from 12 organ systems (constitutional; eyes; ears, nose, mouth, and throat; cardiovascular; respiratory; gastrointestinal; genitourinary; musculoskeletal; integumentary; neurological; psychiatric; hematologic, lymphatic, and immunologic).

Further, these guidelines let physicians document their findings in any manner while adhering to some simple rules:

- Document relevant negative findings. Commenting that a system or area is “negative” or “normal” is acceptable when referring to unaffected areas or asymptomatic organ systems; and

- Elaborate on abnormal findings. Commenting that a system or area is “abnormal” is not sufficient unless additional comments describing the abnormality are documented.

1997 Guidelines

The 1997 guidelines comprise bulleted items—referred to as elements—that correspond to each organ system. Some elements specify numeric criterion that must be met to credit the physician for documentation of that element.

For example, the physician only receives credit for documentation of vital signs (an element of the constitutional system) when three measurements are referenced (e.g., blood pressure, heart rate, and respiratory rate). Documentation that does not include three measurements or only contains a single generalized comment (e.g., vital signs stable) cannot be credited to the physician in the 1997 guidelines—even though these same comments are credited when applying the 1995 guidelines.

This logic also applies to the lymphatic system. The physician must identify findings associated with at least two lymphatic areas examined (e.g., “no lymphadenopathy of the neck or axillae”).

Elements that do not contain numeric criterion but identify multiple components require documentation of at least one component. For example, one psychiatric element involves the assessment of the patient’s “mood and affect.” If the physician comments that the patient appears depressed but does not comment on a flat (or normal) affect, the physician still receives credit for this exam element.

Levels of Exam

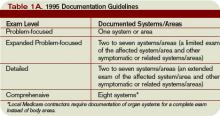

There are four levels of exam, determined by the number of elements documented in the progress note (see Tables 1A and 1B, p. below).

As with the history component, the physician must meet the requirements for a particular level of exam before assigning it. The most problematic feature of the 1995 guidelines involves the “detailed” exam. Both the expanded problem-focused and detailed exams involve two to seven systems/areas, but the detailed exam requires an “extended” exam of the affected system/area related to the presenting problem. Questions surround the number of elements needed to qualify as an “extended” exam of the affected system/area.

Does “regular rate and rhythm; normal S1, S2; no jugular venous distention; no murmur, gallop, or rub; peripheral pulses intact; no edema noted” constitute an “extended” exam of the cardiovascular system, or should there be an additional comment regarding the abdominal aorta? This decision is left to the discretion of the local Medicare contractor and/or the medical reviewer.

Since no other CMS directive has been provided, documentation of the detailed exam continues to be inconsistent. More importantly, review and audit of the detailed exam remains arbitrary. Some Medicare contractors suggest using the 1997 requirements for the detailed exam, while others create their own definition and corresponding number of exam elements needed for documentation of the detailed exam. This issue exemplifies the ambiguity for which the 1995 guidelines often are criticized.

Meanwhile, the 1997 guidelines often are criticized as too specific. While this may help the medical reviewer/auditor, it hinders the physician. Physicians are frequently frustrated trying to remember the explicit comments and number of elements associated with a particular level of exam.

One solution is documentation templates. Physicians can use paper or electronic templates that incorporate cues and prompts for normal exam findings, incorporating adequate space to elaborate abnormal findings.

Remember the physician has the option of utilizing either the 1995 or 1997 guidelines, depending upon which set he perceives as easier to implement.

Additionally, auditors must review physician documentation using both the 1995 and 1997 guidelines, and apply the most favorable result to the final audit score.

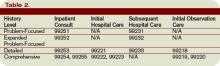

Each type of evaluation and management service identifies a specific level of exam that must be documented in the medical record before the associated CPT code is submitted on a claim.

The most common visit categories provided by hospitalists and corresponding exam levels are outlined in Table 2 (above). Similar to the history component, other visit categories, such as critical care and discharge day management, do not have specified levels of exam or associated documentation requirements for physical exam elements. TH

Carol Pohlig is a billing and coding expert with the University of Pennsylvania Medical Center, Philadelphia. She also is on the faculty of SHM’s inpatient coding course.

Physicians only should perform patient examinations based upon the presenting problem and the standard of care. As mentioned in my previous column (April 2008, p. 21), the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) and the American Medical Association (AMA) set forth two sets of documentation guidelines. The biggest difference between them is the exam component.

1995 Guidelines

The 1995 guidelines distinguish 10 body areas (head and face; neck; chest, breast, and axillae; abdomen; genitalia, groin, and buttocks; back and spine; right upper extremity; left upper extremity; right lower extremity; and left lower extremity) from 12 organ systems (constitutional; eyes; ears, nose, mouth, and throat; cardiovascular; respiratory; gastrointestinal; genitourinary; musculoskeletal; integumentary; neurological; psychiatric; hematologic, lymphatic, and immunologic).

Further, these guidelines let physicians document their findings in any manner while adhering to some simple rules:

- Document relevant negative findings. Commenting that a system or area is “negative” or “normal” is acceptable when referring to unaffected areas or asymptomatic organ systems; and

- Elaborate on abnormal findings. Commenting that a system or area is “abnormal” is not sufficient unless additional comments describing the abnormality are documented.

1997 Guidelines

The 1997 guidelines comprise bulleted items—referred to as elements—that correspond to each organ system. Some elements specify numeric criterion that must be met to credit the physician for documentation of that element.

For example, the physician only receives credit for documentation of vital signs (an element of the constitutional system) when three measurements are referenced (e.g., blood pressure, heart rate, and respiratory rate). Documentation that does not include three measurements or only contains a single generalized comment (e.g., vital signs stable) cannot be credited to the physician in the 1997 guidelines—even though these same comments are credited when applying the 1995 guidelines.

This logic also applies to the lymphatic system. The physician must identify findings associated with at least two lymphatic areas examined (e.g., “no lymphadenopathy of the neck or axillae”).

Elements that do not contain numeric criterion but identify multiple components require documentation of at least one component. For example, one psychiatric element involves the assessment of the patient’s “mood and affect.” If the physician comments that the patient appears depressed but does not comment on a flat (or normal) affect, the physician still receives credit for this exam element.

Levels of Exam

There are four levels of exam, determined by the number of elements documented in the progress note (see Tables 1A and 1B, p. below).

As with the history component, the physician must meet the requirements for a particular level of exam before assigning it. The most problematic feature of the 1995 guidelines involves the “detailed” exam. Both the expanded problem-focused and detailed exams involve two to seven systems/areas, but the detailed exam requires an “extended” exam of the affected system/area related to the presenting problem. Questions surround the number of elements needed to qualify as an “extended” exam of the affected system/area.

Does “regular rate and rhythm; normal S1, S2; no jugular venous distention; no murmur, gallop, or rub; peripheral pulses intact; no edema noted” constitute an “extended” exam of the cardiovascular system, or should there be an additional comment regarding the abdominal aorta? This decision is left to the discretion of the local Medicare contractor and/or the medical reviewer.

Since no other CMS directive has been provided, documentation of the detailed exam continues to be inconsistent. More importantly, review and audit of the detailed exam remains arbitrary. Some Medicare contractors suggest using the 1997 requirements for the detailed exam, while others create their own definition and corresponding number of exam elements needed for documentation of the detailed exam. This issue exemplifies the ambiguity for which the 1995 guidelines often are criticized.

Meanwhile, the 1997 guidelines often are criticized as too specific. While this may help the medical reviewer/auditor, it hinders the physician. Physicians are frequently frustrated trying to remember the explicit comments and number of elements associated with a particular level of exam.

One solution is documentation templates. Physicians can use paper or electronic templates that incorporate cues and prompts for normal exam findings, incorporating adequate space to elaborate abnormal findings.

Remember the physician has the option of utilizing either the 1995 or 1997 guidelines, depending upon which set he perceives as easier to implement.

Additionally, auditors must review physician documentation using both the 1995 and 1997 guidelines, and apply the most favorable result to the final audit score.

Each type of evaluation and management service identifies a specific level of exam that must be documented in the medical record before the associated CPT code is submitted on a claim.

The most common visit categories provided by hospitalists and corresponding exam levels are outlined in Table 2 (above). Similar to the history component, other visit categories, such as critical care and discharge day management, do not have specified levels of exam or associated documentation requirements for physical exam elements. TH

Carol Pohlig is a billing and coding expert with the University of Pennsylvania Medical Center, Philadelphia. She also is on the faculty of SHM’s inpatient coding course.

Physicians only should perform patient examinations based upon the presenting problem and the standard of care. As mentioned in my previous column (April 2008, p. 21), the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) and the American Medical Association (AMA) set forth two sets of documentation guidelines. The biggest difference between them is the exam component.

1995 Guidelines

The 1995 guidelines distinguish 10 body areas (head and face; neck; chest, breast, and axillae; abdomen; genitalia, groin, and buttocks; back and spine; right upper extremity; left upper extremity; right lower extremity; and left lower extremity) from 12 organ systems (constitutional; eyes; ears, nose, mouth, and throat; cardiovascular; respiratory; gastrointestinal; genitourinary; musculoskeletal; integumentary; neurological; psychiatric; hematologic, lymphatic, and immunologic).

Further, these guidelines let physicians document their findings in any manner while adhering to some simple rules:

- Document relevant negative findings. Commenting that a system or area is “negative” or “normal” is acceptable when referring to unaffected areas or asymptomatic organ systems; and

- Elaborate on abnormal findings. Commenting that a system or area is “abnormal” is not sufficient unless additional comments describing the abnormality are documented.

1997 Guidelines

The 1997 guidelines comprise bulleted items—referred to as elements—that correspond to each organ system. Some elements specify numeric criterion that must be met to credit the physician for documentation of that element.

For example, the physician only receives credit for documentation of vital signs (an element of the constitutional system) when three measurements are referenced (e.g., blood pressure, heart rate, and respiratory rate). Documentation that does not include three measurements or only contains a single generalized comment (e.g., vital signs stable) cannot be credited to the physician in the 1997 guidelines—even though these same comments are credited when applying the 1995 guidelines.

This logic also applies to the lymphatic system. The physician must identify findings associated with at least two lymphatic areas examined (e.g., “no lymphadenopathy of the neck or axillae”).

Elements that do not contain numeric criterion but identify multiple components require documentation of at least one component. For example, one psychiatric element involves the assessment of the patient’s “mood and affect.” If the physician comments that the patient appears depressed but does not comment on a flat (or normal) affect, the physician still receives credit for this exam element.

Levels of Exam

There are four levels of exam, determined by the number of elements documented in the progress note (see Tables 1A and 1B, p. below).

As with the history component, the physician must meet the requirements for a particular level of exam before assigning it. The most problematic feature of the 1995 guidelines involves the “detailed” exam. Both the expanded problem-focused and detailed exams involve two to seven systems/areas, but the detailed exam requires an “extended” exam of the affected system/area related to the presenting problem. Questions surround the number of elements needed to qualify as an “extended” exam of the affected system/area.

Does “regular rate and rhythm; normal S1, S2; no jugular venous distention; no murmur, gallop, or rub; peripheral pulses intact; no edema noted” constitute an “extended” exam of the cardiovascular system, or should there be an additional comment regarding the abdominal aorta? This decision is left to the discretion of the local Medicare contractor and/or the medical reviewer.

Since no other CMS directive has been provided, documentation of the detailed exam continues to be inconsistent. More importantly, review and audit of the detailed exam remains arbitrary. Some Medicare contractors suggest using the 1997 requirements for the detailed exam, while others create their own definition and corresponding number of exam elements needed for documentation of the detailed exam. This issue exemplifies the ambiguity for which the 1995 guidelines often are criticized.

Meanwhile, the 1997 guidelines often are criticized as too specific. While this may help the medical reviewer/auditor, it hinders the physician. Physicians are frequently frustrated trying to remember the explicit comments and number of elements associated with a particular level of exam.

One solution is documentation templates. Physicians can use paper or electronic templates that incorporate cues and prompts for normal exam findings, incorporating adequate space to elaborate abnormal findings.

Remember the physician has the option of utilizing either the 1995 or 1997 guidelines, depending upon which set he perceives as easier to implement.

Additionally, auditors must review physician documentation using both the 1995 and 1997 guidelines, and apply the most favorable result to the final audit score.

Each type of evaluation and management service identifies a specific level of exam that must be documented in the medical record before the associated CPT code is submitted on a claim.

The most common visit categories provided by hospitalists and corresponding exam levels are outlined in Table 2 (above). Similar to the history component, other visit categories, such as critical care and discharge day management, do not have specified levels of exam or associated documentation requirements for physical exam elements. TH

Carol Pohlig is a billing and coding expert with the University of Pennsylvania Medical Center, Philadelphia. She also is on the faculty of SHM’s inpatient coding course.

Document Patient History

Documentation in the medical record serves many purposes: communication among healthcare professionals, evidence of patient care, and justification for provider claims.

Although these three aspects of documentation are intertwined, the first two prevent physicians from paying settlements involving malpractice allegations, while the last one assists in obtaining appropriate reimbursement for services rendered. This is the first of a three-part series that will focus on claim reporting and outline the documentation guidelines set forth by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) in conjunction with the American Medical Association (AMA).

1995, 1997 Guidelines

Two sets of documentation guidelines are in place, referred to as the 1995 and 1997 guidelines. Increased criticism of the ambiguity in the 1995 guidelines from auditors and providers inspired development of the 1997 guidelines.

While the 1997 guidelines were intended to create a more objective and unified approach to documentation, the level of specificity required brought criticism and frustration. But while the physician community balked, most auditors praised these efforts.

To satisfy all parties and allow physicians to document as they prefer, both sets of guidelines remain. Physicians can document according to either style, and auditors are obligated to review provider records against both sets of guidelines, selecting the final visit level with the set that best supports provider documentation.

Elements of History

Chief complaint (CC): The CC is the reason for the visit as stated in the patient’s own words. This must be present for each encounter, and should reference a specific condition or complaint (e.g., patient complains of abdominal pain).

History of present illness (HPI): This is a description of the present illness as it developed. It is typically formatted and documented with reference to location, quality, severity, timing, context, modifying factors, and associated signs/symptoms as related to the chief complaint. The HPI may be classified as brief (a comment on fewer than HPI elements) or extended (a comment on more than four HPI elements). Sample documentation of an extended HPI is: “The patient has intermittent (duration), sharp (quality) pain in the right upper quadrant (location) without associated nausea, vomiting, or diarrhea (associated signs/symptoms).”

The 1997 guidelines offer an alternate format for documenting the HPI. In contrast to the standard method above, the physician may list and status the patient’s chronic or inactive conditions. An extended HPI consists of the status of at least three chronic or inactive conditions (e.g., “Diabetes controlled by oral medication; extrinsic asthma without acute exacerbation in past six months; hypertension stable with pressures ranging from 130-140/80-90”). Failing to document the status negates the opportunity for the physician to receive HPI credit. Instead, he will receive credit for a past medical history.

The HPI should never be documented by ancillary staff (e.g., registered nurse, medical assistant, students). HPI might be documented by residents (e.g., residents, fellows, interns) or nonphysician providers (nurse practitioners and physician assistants) when utilizing the Teaching Physician Rules or Split-Shared Billing Rules, respectively (teaching Physician Rules and Split-Shared Billing Rules will be addressed in an upcoming issue).

Review of systems (ROS): This is a series of questions used to elicit information about additional signs, symptoms, or problems currently or previously experienced by the patient:

- Constitutional;

- Eyes; ears, nose, mouth, throat;

- Cardiovascular;

- Respiratory;

- Gastrointestinal;

- Genitourinary;

- Musculoskeletal;

- Integumentary (including skin and/or breast);

- Neurological;

- Psychiatric;

- Endocrine;

- Hematologic/lymphatic; and

- Allergic/immunologic.

The ROS may be classified as brief (a comment on one system), expanded (a comment on two to nine systems), or complete (a comment on more than 10 systems).

Documentation of a complete ROS (more than 10 systems) can occur in two ways:

- The physician can individually document each system. For example: “No fever/chills (constitutional) or blurred vision (eyes); no chest pain (cardiovascular); shortness of breath (respiratory); or belly pain (gastrointestinal); etc.”; or

- The physician can document the positive findings and pertinent negative findings related to the chief complaint, along with a comment that “all other systems are negative.” This latter statement is not accepted by all local Medicare contractors.

Information involving the ROS can be documented by anyone, including the patient. If documented by someone else (e.g., a medical student) other than residents under the Teaching Physician Rules or nonphysician providers under the Split-Shared Billing Rules, the physician should reference the documented ROS in his progress note. Re-documentation of the ROS is not necessary unless a revision is required.

Past, family, and social history (PFSH): Documentation of PFSH involves data obtained about the patient’s previous illness or medical conditions/therapies, family occurrences with illness, and relevant patient activities. The PFSH can be classified as pertinent (a comment on one history) or complete (a comment in each of the three histories). Documentation that exemplifies a complete PFSH is: “Patient currently on Prilosec 20 mg daily; family history of Barrett’s esophagus; no tobacco or alcohol use.”

As with ROS, the PFSH can be documented by anyone, including the patient. If documented by someone else (e.g., a medical student) other than residents under the Teaching Physician Rules or nonphysician providers under the Split-Shared Billing Rules, the physician should reference the documented PFSH in his progress note. Re-documentation of the PFSH is not necessary unless a revision is required. It is important to note that while documentation of the PFSH is required when billing higher level consultations (99254-99255) or initial inpatient care (99221-99223), it is not required when reporting subsequent hospital care services (99231-99233).

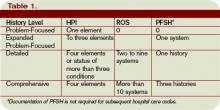

Levels of History

There are four levels of history, determined by the number of elements documented in the progress note (see Table 1, p. 21). The physician must meet all the requirements in a specific level of history before assigning it.

If all of the required elements in a given history level are not documented, the level assigned is that of the least documented element. For example, physician documentation may include four HPI elements and a complete PFSH, yet only eight ROS. The physician can only receive credit for a detailed history. If the physician submitted a claim for 99222 (initial hospital care requiring a comprehensive history, a comprehensive exam, and moderate-complexity decision making), documentation would not support the reported service due to the underdocumented ROS. Deficiencies in the ROS and family history are the most common physician documentation errors involving the history component.

A specific level of history is associated with each type of physician encounter, and must be documented accordingly (see Table 2, right). The most common visit categories provided by hospitalists that include documentation requirements for history are initial inpatient consultations, initial hospital care, subsequent hospital care, and initial observation care. Other visit categories, such as critical care and discharge day management, have neither associated levels of history nor documentation requirements for historical elements. TH

Carol Pohlig is a billing and coding expert with the University of Pennsylvania Medical Center, Philadelphia. She is also on the faculty of SHM’s inpatient coding course.

Documentation in the medical record serves many purposes: communication among healthcare professionals, evidence of patient care, and justification for provider claims.

Although these three aspects of documentation are intertwined, the first two prevent physicians from paying settlements involving malpractice allegations, while the last one assists in obtaining appropriate reimbursement for services rendered. This is the first of a three-part series that will focus on claim reporting and outline the documentation guidelines set forth by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) in conjunction with the American Medical Association (AMA).

1995, 1997 Guidelines

Two sets of documentation guidelines are in place, referred to as the 1995 and 1997 guidelines. Increased criticism of the ambiguity in the 1995 guidelines from auditors and providers inspired development of the 1997 guidelines.

While the 1997 guidelines were intended to create a more objective and unified approach to documentation, the level of specificity required brought criticism and frustration. But while the physician community balked, most auditors praised these efforts.

To satisfy all parties and allow physicians to document as they prefer, both sets of guidelines remain. Physicians can document according to either style, and auditors are obligated to review provider records against both sets of guidelines, selecting the final visit level with the set that best supports provider documentation.

Elements of History

Chief complaint (CC): The CC is the reason for the visit as stated in the patient’s own words. This must be present for each encounter, and should reference a specific condition or complaint (e.g., patient complains of abdominal pain).

History of present illness (HPI): This is a description of the present illness as it developed. It is typically formatted and documented with reference to location, quality, severity, timing, context, modifying factors, and associated signs/symptoms as related to the chief complaint. The HPI may be classified as brief (a comment on fewer than HPI elements) or extended (a comment on more than four HPI elements). Sample documentation of an extended HPI is: “The patient has intermittent (duration), sharp (quality) pain in the right upper quadrant (location) without associated nausea, vomiting, or diarrhea (associated signs/symptoms).”

The 1997 guidelines offer an alternate format for documenting the HPI. In contrast to the standard method above, the physician may list and status the patient’s chronic or inactive conditions. An extended HPI consists of the status of at least three chronic or inactive conditions (e.g., “Diabetes controlled by oral medication; extrinsic asthma without acute exacerbation in past six months; hypertension stable with pressures ranging from 130-140/80-90”). Failing to document the status negates the opportunity for the physician to receive HPI credit. Instead, he will receive credit for a past medical history.

The HPI should never be documented by ancillary staff (e.g., registered nurse, medical assistant, students). HPI might be documented by residents (e.g., residents, fellows, interns) or nonphysician providers (nurse practitioners and physician assistants) when utilizing the Teaching Physician Rules or Split-Shared Billing Rules, respectively (teaching Physician Rules and Split-Shared Billing Rules will be addressed in an upcoming issue).

Review of systems (ROS): This is a series of questions used to elicit information about additional signs, symptoms, or problems currently or previously experienced by the patient:

- Constitutional;

- Eyes; ears, nose, mouth, throat;

- Cardiovascular;

- Respiratory;

- Gastrointestinal;

- Genitourinary;

- Musculoskeletal;

- Integumentary (including skin and/or breast);

- Neurological;

- Psychiatric;

- Endocrine;

- Hematologic/lymphatic; and

- Allergic/immunologic.

The ROS may be classified as brief (a comment on one system), expanded (a comment on two to nine systems), or complete (a comment on more than 10 systems).

Documentation of a complete ROS (more than 10 systems) can occur in two ways:

- The physician can individually document each system. For example: “No fever/chills (constitutional) or blurred vision (eyes); no chest pain (cardiovascular); shortness of breath (respiratory); or belly pain (gastrointestinal); etc.”; or

- The physician can document the positive findings and pertinent negative findings related to the chief complaint, along with a comment that “all other systems are negative.” This latter statement is not accepted by all local Medicare contractors.

Information involving the ROS can be documented by anyone, including the patient. If documented by someone else (e.g., a medical student) other than residents under the Teaching Physician Rules or nonphysician providers under the Split-Shared Billing Rules, the physician should reference the documented ROS in his progress note. Re-documentation of the ROS is not necessary unless a revision is required.

Past, family, and social history (PFSH): Documentation of PFSH involves data obtained about the patient’s previous illness or medical conditions/therapies, family occurrences with illness, and relevant patient activities. The PFSH can be classified as pertinent (a comment on one history) or complete (a comment in each of the three histories). Documentation that exemplifies a complete PFSH is: “Patient currently on Prilosec 20 mg daily; family history of Barrett’s esophagus; no tobacco or alcohol use.”

As with ROS, the PFSH can be documented by anyone, including the patient. If documented by someone else (e.g., a medical student) other than residents under the Teaching Physician Rules or nonphysician providers under the Split-Shared Billing Rules, the physician should reference the documented PFSH in his progress note. Re-documentation of the PFSH is not necessary unless a revision is required. It is important to note that while documentation of the PFSH is required when billing higher level consultations (99254-99255) or initial inpatient care (99221-99223), it is not required when reporting subsequent hospital care services (99231-99233).

Levels of History

There are four levels of history, determined by the number of elements documented in the progress note (see Table 1, p. 21). The physician must meet all the requirements in a specific level of history before assigning it.

If all of the required elements in a given history level are not documented, the level assigned is that of the least documented element. For example, physician documentation may include four HPI elements and a complete PFSH, yet only eight ROS. The physician can only receive credit for a detailed history. If the physician submitted a claim for 99222 (initial hospital care requiring a comprehensive history, a comprehensive exam, and moderate-complexity decision making), documentation would not support the reported service due to the underdocumented ROS. Deficiencies in the ROS and family history are the most common physician documentation errors involving the history component.

A specific level of history is associated with each type of physician encounter, and must be documented accordingly (see Table 2, right). The most common visit categories provided by hospitalists that include documentation requirements for history are initial inpatient consultations, initial hospital care, subsequent hospital care, and initial observation care. Other visit categories, such as critical care and discharge day management, have neither associated levels of history nor documentation requirements for historical elements. TH

Carol Pohlig is a billing and coding expert with the University of Pennsylvania Medical Center, Philadelphia. She is also on the faculty of SHM’s inpatient coding course.

Documentation in the medical record serves many purposes: communication among healthcare professionals, evidence of patient care, and justification for provider claims.

Although these three aspects of documentation are intertwined, the first two prevent physicians from paying settlements involving malpractice allegations, while the last one assists in obtaining appropriate reimbursement for services rendered. This is the first of a three-part series that will focus on claim reporting and outline the documentation guidelines set forth by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) in conjunction with the American Medical Association (AMA).

1995, 1997 Guidelines

Two sets of documentation guidelines are in place, referred to as the 1995 and 1997 guidelines. Increased criticism of the ambiguity in the 1995 guidelines from auditors and providers inspired development of the 1997 guidelines.

While the 1997 guidelines were intended to create a more objective and unified approach to documentation, the level of specificity required brought criticism and frustration. But while the physician community balked, most auditors praised these efforts.

To satisfy all parties and allow physicians to document as they prefer, both sets of guidelines remain. Physicians can document according to either style, and auditors are obligated to review provider records against both sets of guidelines, selecting the final visit level with the set that best supports provider documentation.

Elements of History

Chief complaint (CC): The CC is the reason for the visit as stated in the patient’s own words. This must be present for each encounter, and should reference a specific condition or complaint (e.g., patient complains of abdominal pain).

History of present illness (HPI): This is a description of the present illness as it developed. It is typically formatted and documented with reference to location, quality, severity, timing, context, modifying factors, and associated signs/symptoms as related to the chief complaint. The HPI may be classified as brief (a comment on fewer than HPI elements) or extended (a comment on more than four HPI elements). Sample documentation of an extended HPI is: “The patient has intermittent (duration), sharp (quality) pain in the right upper quadrant (location) without associated nausea, vomiting, or diarrhea (associated signs/symptoms).”

The 1997 guidelines offer an alternate format for documenting the HPI. In contrast to the standard method above, the physician may list and status the patient’s chronic or inactive conditions. An extended HPI consists of the status of at least three chronic or inactive conditions (e.g., “Diabetes controlled by oral medication; extrinsic asthma without acute exacerbation in past six months; hypertension stable with pressures ranging from 130-140/80-90”). Failing to document the status negates the opportunity for the physician to receive HPI credit. Instead, he will receive credit for a past medical history.

The HPI should never be documented by ancillary staff (e.g., registered nurse, medical assistant, students). HPI might be documented by residents (e.g., residents, fellows, interns) or nonphysician providers (nurse practitioners and physician assistants) when utilizing the Teaching Physician Rules or Split-Shared Billing Rules, respectively (teaching Physician Rules and Split-Shared Billing Rules will be addressed in an upcoming issue).

Review of systems (ROS): This is a series of questions used to elicit information about additional signs, symptoms, or problems currently or previously experienced by the patient:

- Constitutional;

- Eyes; ears, nose, mouth, throat;

- Cardiovascular;

- Respiratory;

- Gastrointestinal;

- Genitourinary;

- Musculoskeletal;

- Integumentary (including skin and/or breast);

- Neurological;

- Psychiatric;

- Endocrine;

- Hematologic/lymphatic; and

- Allergic/immunologic.

The ROS may be classified as brief (a comment on one system), expanded (a comment on two to nine systems), or complete (a comment on more than 10 systems).

Documentation of a complete ROS (more than 10 systems) can occur in two ways:

- The physician can individually document each system. For example: “No fever/chills (constitutional) or blurred vision (eyes); no chest pain (cardiovascular); shortness of breath (respiratory); or belly pain (gastrointestinal); etc.”; or

- The physician can document the positive findings and pertinent negative findings related to the chief complaint, along with a comment that “all other systems are negative.” This latter statement is not accepted by all local Medicare contractors.

Information involving the ROS can be documented by anyone, including the patient. If documented by someone else (e.g., a medical student) other than residents under the Teaching Physician Rules or nonphysician providers under the Split-Shared Billing Rules, the physician should reference the documented ROS in his progress note. Re-documentation of the ROS is not necessary unless a revision is required.

Past, family, and social history (PFSH): Documentation of PFSH involves data obtained about the patient’s previous illness or medical conditions/therapies, family occurrences with illness, and relevant patient activities. The PFSH can be classified as pertinent (a comment on one history) or complete (a comment in each of the three histories). Documentation that exemplifies a complete PFSH is: “Patient currently on Prilosec 20 mg daily; family history of Barrett’s esophagus; no tobacco or alcohol use.”

As with ROS, the PFSH can be documented by anyone, including the patient. If documented by someone else (e.g., a medical student) other than residents under the Teaching Physician Rules or nonphysician providers under the Split-Shared Billing Rules, the physician should reference the documented PFSH in his progress note. Re-documentation of the PFSH is not necessary unless a revision is required. It is important to note that while documentation of the PFSH is required when billing higher level consultations (99254-99255) or initial inpatient care (99221-99223), it is not required when reporting subsequent hospital care services (99231-99233).

Levels of History

There are four levels of history, determined by the number of elements documented in the progress note (see Table 1, p. 21). The physician must meet all the requirements in a specific level of history before assigning it.

If all of the required elements in a given history level are not documented, the level assigned is that of the least documented element. For example, physician documentation may include four HPI elements and a complete PFSH, yet only eight ROS. The physician can only receive credit for a detailed history. If the physician submitted a claim for 99222 (initial hospital care requiring a comprehensive history, a comprehensive exam, and moderate-complexity decision making), documentation would not support the reported service due to the underdocumented ROS. Deficiencies in the ROS and family history are the most common physician documentation errors involving the history component.

A specific level of history is associated with each type of physician encounter, and must be documented accordingly (see Table 2, right). The most common visit categories provided by hospitalists that include documentation requirements for history are initial inpatient consultations, initial hospital care, subsequent hospital care, and initial observation care. Other visit categories, such as critical care and discharge day management, have neither associated levels of history nor documentation requirements for historical elements. TH

Carol Pohlig is a billing and coding expert with the University of Pennsylvania Medical Center, Philadelphia. She is also on the faculty of SHM’s inpatient coding course.

Report Critical Care

Hospitalists often encounter patients who are or could become critically ill. The increased efforts while caring for these patients are best captured through critical-care service codes 99291 and 99292.

Although these codes yield higher reimbursement ($204.15 and $102.45, respectively, per national Medicare average payment), they are reported only under certain circumstances. The physician’s documentation must include enough detail to support critical-care claims: the patient’s condition, the nature of the physician’s care, and the time spent rendering care. Documentation of any other pertinent information is strongly encouraged because these services often come under payer scrutiny.

Condition and Care

A patient’s condition must meet the established criteria before the service qualifies as critical care. More specifically, the patient must have a critical illness or injury that acutely impairs one or more vital organ systems such that there is a high probability of imminent or life-threatening deterioration in the patient’s condition.

The physician’s personal attention (i.e., care involving one critically ill patient at a time) is essential for rendering the highly complex decisions necessary to prevent the patient’s decline if left untreated. Given the seriousness of the patient’s condition, the physician is expected to focus only on the patient for whom critical-care time is reported.

Duration

Critical care is a time-based service. It constitutes the physician’s time spent providing direct care at the bedside and gathering and reviewing data on the patient’s unit or floor.

If the physician is not immediately available to the patient, the time associated with indirect care (e.g., reviewing data, calling the family from the office) is not counted in the overall critical-care service.

The physician keeps tracks of his/her total critical-care time throughout the day. A new period of critical-care time begins each calendar day. There is no prohibition against reporting multiple hours or days of critical care, as long as the patient’s condition prompts the service and documentation supports it.

Code 99291 represents the first “hour” of critical care, which physicians may report after accumulating the first 30 minutes of care. Alternately, physician management of the patient involving less than 30 minutes of critical-care time on a given day must be reported with the appropriate evaluation and management (E/M) code:

- Initial inpatient service (99221-99223);

- Subsequent hospital care (99231-99233); or

- Inpatient consultation (99251-99255).

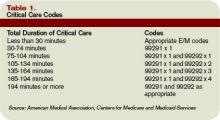

Once the physician achieves 75 minutes of critical-care time, he/she reports 99292 for the additional “30 minutes” of care beyond the first hour. Never report 99292 alone on the claim form. Code 99292 is considered an “add-on” code, which means it must be reported in addition to a primary code. Code 99291 is always the primary code (reported once per physician/group per day) for critical-care services. Code 99292 can be reported in multiple units per physician/group per day according to the number of minutes spent after the initial hour (see Table 1, p. 30).

Service Inclusions

Critical care involves highly complex decision making to manage the patient’s condition. This includes the physician’s performance and/or interpretation of labs, diagnostic studies, and procedures inherent in critical care.

Therefore, do not report the following services when billing 99291-99292:

- Cardiac output measurements (93561, 93562);

- Chest X-rays (71010, 71015, 71020);

- Pulse oximetry (94760, 94761, 94762); and

- Blood gases (multiple codes).

Further, don’t report interpretation of data stored in computers:

- Electrocardiograms, blood pressures, hematologic data (99090);

- Gastric intubation (43752, 91105);

- Temporary transcutaneous pacing (92953);

- Ventilation management (94002-94004, 94660, 94662); and

- Vascular access procedures (36000, 36410, 36415, 36591, 36600).

Any other service or procedure provided by the physician can be billed in addition to 99291-99292.

Be sure not to add separately billable procedure time into the physician’s total critical-care time. A notation in the medical record should reflect this (e.g., time spent inserting a central line is not included in today’s critical-care time).

Location

Because a patient can become seriously ill in any setting, physicians often provide critical-care services in emergency departments (EDs) and on standard medical-surgical floors before the patient is transferred to the intensive care unit (ICU).

Bed location alone does not determine critical-care reporting. Patients assigned to an ICU might be critically ill or injured and meet the “condition” requirements for 99291-99292.

However, the care provided may not meet the remaining requirements. According to the American Medical Association’s Current Procedural Terminology 2008 (Professional Edition) and the Medicare Claims Processing Manual, payment can be made for critical-care services provided in any location as long as the care provided meets the definition of critical care. Services for a patient who is not critically ill and unstable but who happens to be receiving care in a critical-care, intensive-care, or other specialized-care unit are reported using subsequent hospital care codes 99231-99233 or hospital consultation codes 99251-99255. TH

Carol Pohlig is a billing and coding expert with the University of Pennsylvania Medical Center, Philadelphia. She is also on the faculty of SHM’s inpatient coding course.

Hospitalists often encounter patients who are or could become critically ill. The increased efforts while caring for these patients are best captured through critical-care service codes 99291 and 99292.

Although these codes yield higher reimbursement ($204.15 and $102.45, respectively, per national Medicare average payment), they are reported only under certain circumstances. The physician’s documentation must include enough detail to support critical-care claims: the patient’s condition, the nature of the physician’s care, and the time spent rendering care. Documentation of any other pertinent information is strongly encouraged because these services often come under payer scrutiny.

Condition and Care

A patient’s condition must meet the established criteria before the service qualifies as critical care. More specifically, the patient must have a critical illness or injury that acutely impairs one or more vital organ systems such that there is a high probability of imminent or life-threatening deterioration in the patient’s condition.

The physician’s personal attention (i.e., care involving one critically ill patient at a time) is essential for rendering the highly complex decisions necessary to prevent the patient’s decline if left untreated. Given the seriousness of the patient’s condition, the physician is expected to focus only on the patient for whom critical-care time is reported.

Duration

Critical care is a time-based service. It constitutes the physician’s time spent providing direct care at the bedside and gathering and reviewing data on the patient’s unit or floor.

If the physician is not immediately available to the patient, the time associated with indirect care (e.g., reviewing data, calling the family from the office) is not counted in the overall critical-care service.

The physician keeps tracks of his/her total critical-care time throughout the day. A new period of critical-care time begins each calendar day. There is no prohibition against reporting multiple hours or days of critical care, as long as the patient’s condition prompts the service and documentation supports it.

Code 99291 represents the first “hour” of critical care, which physicians may report after accumulating the first 30 minutes of care. Alternately, physician management of the patient involving less than 30 minutes of critical-care time on a given day must be reported with the appropriate evaluation and management (E/M) code:

- Initial inpatient service (99221-99223);

- Subsequent hospital care (99231-99233); or

- Inpatient consultation (99251-99255).

Once the physician achieves 75 minutes of critical-care time, he/she reports 99292 for the additional “30 minutes” of care beyond the first hour. Never report 99292 alone on the claim form. Code 99292 is considered an “add-on” code, which means it must be reported in addition to a primary code. Code 99291 is always the primary code (reported once per physician/group per day) for critical-care services. Code 99292 can be reported in multiple units per physician/group per day according to the number of minutes spent after the initial hour (see Table 1, p. 30).

Service Inclusions

Critical care involves highly complex decision making to manage the patient’s condition. This includes the physician’s performance and/or interpretation of labs, diagnostic studies, and procedures inherent in critical care.

Therefore, do not report the following services when billing 99291-99292:

- Cardiac output measurements (93561, 93562);

- Chest X-rays (71010, 71015, 71020);

- Pulse oximetry (94760, 94761, 94762); and

- Blood gases (multiple codes).

Further, don’t report interpretation of data stored in computers:

- Electrocardiograms, blood pressures, hematologic data (99090);

- Gastric intubation (43752, 91105);

- Temporary transcutaneous pacing (92953);

- Ventilation management (94002-94004, 94660, 94662); and

- Vascular access procedures (36000, 36410, 36415, 36591, 36600).

Any other service or procedure provided by the physician can be billed in addition to 99291-99292.

Be sure not to add separately billable procedure time into the physician’s total critical-care time. A notation in the medical record should reflect this (e.g., time spent inserting a central line is not included in today’s critical-care time).

Location

Because a patient can become seriously ill in any setting, physicians often provide critical-care services in emergency departments (EDs) and on standard medical-surgical floors before the patient is transferred to the intensive care unit (ICU).

Bed location alone does not determine critical-care reporting. Patients assigned to an ICU might be critically ill or injured and meet the “condition” requirements for 99291-99292.

However, the care provided may not meet the remaining requirements. According to the American Medical Association’s Current Procedural Terminology 2008 (Professional Edition) and the Medicare Claims Processing Manual, payment can be made for critical-care services provided in any location as long as the care provided meets the definition of critical care. Services for a patient who is not critically ill and unstable but who happens to be receiving care in a critical-care, intensive-care, or other specialized-care unit are reported using subsequent hospital care codes 99231-99233 or hospital consultation codes 99251-99255. TH

Carol Pohlig is a billing and coding expert with the University of Pennsylvania Medical Center, Philadelphia. She is also on the faculty of SHM’s inpatient coding course.

Hospitalists often encounter patients who are or could become critically ill. The increased efforts while caring for these patients are best captured through critical-care service codes 99291 and 99292.

Although these codes yield higher reimbursement ($204.15 and $102.45, respectively, per national Medicare average payment), they are reported only under certain circumstances. The physician’s documentation must include enough detail to support critical-care claims: the patient’s condition, the nature of the physician’s care, and the time spent rendering care. Documentation of any other pertinent information is strongly encouraged because these services often come under payer scrutiny.

Condition and Care

A patient’s condition must meet the established criteria before the service qualifies as critical care. More specifically, the patient must have a critical illness or injury that acutely impairs one or more vital organ systems such that there is a high probability of imminent or life-threatening deterioration in the patient’s condition.

The physician’s personal attention (i.e., care involving one critically ill patient at a time) is essential for rendering the highly complex decisions necessary to prevent the patient’s decline if left untreated. Given the seriousness of the patient’s condition, the physician is expected to focus only on the patient for whom critical-care time is reported.

Duration

Critical care is a time-based service. It constitutes the physician’s time spent providing direct care at the bedside and gathering and reviewing data on the patient’s unit or floor.

If the physician is not immediately available to the patient, the time associated with indirect care (e.g., reviewing data, calling the family from the office) is not counted in the overall critical-care service.

The physician keeps tracks of his/her total critical-care time throughout the day. A new period of critical-care time begins each calendar day. There is no prohibition against reporting multiple hours or days of critical care, as long as the patient’s condition prompts the service and documentation supports it.