User login

Physicians only should perform patient examinations based upon the presenting problem and the standard of care. As mentioned in my previous column (April 2008, p. 21), the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) and the American Medical Association (AMA) set forth two sets of documentation guidelines. The biggest difference between them is the exam component.

1995 Guidelines

The 1995 guidelines distinguish 10 body areas (head and face; neck; chest, breast, and axillae; abdomen; genitalia, groin, and buttocks; back and spine; right upper extremity; left upper extremity; right lower extremity; and left lower extremity) from 12 organ systems (constitutional; eyes; ears, nose, mouth, and throat; cardiovascular; respiratory; gastrointestinal; genitourinary; musculoskeletal; integumentary; neurological; psychiatric; hematologic, lymphatic, and immunologic).

Further, these guidelines let physicians document their findings in any manner while adhering to some simple rules:

- Document relevant negative findings. Commenting that a system or area is “negative” or “normal” is acceptable when referring to unaffected areas or asymptomatic organ systems; and

- Elaborate on abnormal findings. Commenting that a system or area is “abnormal” is not sufficient unless additional comments describing the abnormality are documented.

1997 Guidelines

The 1997 guidelines comprise bulleted items—referred to as elements—that correspond to each organ system. Some elements specify numeric criterion that must be met to credit the physician for documentation of that element.

For example, the physician only receives credit for documentation of vital signs (an element of the constitutional system) when three measurements are referenced (e.g., blood pressure, heart rate, and respiratory rate). Documentation that does not include three measurements or only contains a single generalized comment (e.g., vital signs stable) cannot be credited to the physician in the 1997 guidelines—even though these same comments are credited when applying the 1995 guidelines.

This logic also applies to the lymphatic system. The physician must identify findings associated with at least two lymphatic areas examined (e.g., “no lymphadenopathy of the neck or axillae”).

Elements that do not contain numeric criterion but identify multiple components require documentation of at least one component. For example, one psychiatric element involves the assessment of the patient’s “mood and affect.” If the physician comments that the patient appears depressed but does not comment on a flat (or normal) affect, the physician still receives credit for this exam element.

Levels of Exam

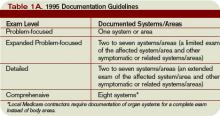

There are four levels of exam, determined by the number of elements documented in the progress note (see Tables 1A and 1B, p. below).

As with the history component, the physician must meet the requirements for a particular level of exam before assigning it. The most problematic feature of the 1995 guidelines involves the “detailed” exam. Both the expanded problem-focused and detailed exams involve two to seven systems/areas, but the detailed exam requires an “extended” exam of the affected system/area related to the presenting problem. Questions surround the number of elements needed to qualify as an “extended” exam of the affected system/area.

Does “regular rate and rhythm; normal S1, S2; no jugular venous distention; no murmur, gallop, or rub; peripheral pulses intact; no edema noted” constitute an “extended” exam of the cardiovascular system, or should there be an additional comment regarding the abdominal aorta? This decision is left to the discretion of the local Medicare contractor and/or the medical reviewer.

Since no other CMS directive has been provided, documentation of the detailed exam continues to be inconsistent. More importantly, review and audit of the detailed exam remains arbitrary. Some Medicare contractors suggest using the 1997 requirements for the detailed exam, while others create their own definition and corresponding number of exam elements needed for documentation of the detailed exam. This issue exemplifies the ambiguity for which the 1995 guidelines often are criticized.

Meanwhile, the 1997 guidelines often are criticized as too specific. While this may help the medical reviewer/auditor, it hinders the physician. Physicians are frequently frustrated trying to remember the explicit comments and number of elements associated with a particular level of exam.

One solution is documentation templates. Physicians can use paper or electronic templates that incorporate cues and prompts for normal exam findings, incorporating adequate space to elaborate abnormal findings.

Remember the physician has the option of utilizing either the 1995 or 1997 guidelines, depending upon which set he perceives as easier to implement.

Additionally, auditors must review physician documentation using both the 1995 and 1997 guidelines, and apply the most favorable result to the final audit score.

Each type of evaluation and management service identifies a specific level of exam that must be documented in the medical record before the associated CPT code is submitted on a claim.

The most common visit categories provided by hospitalists and corresponding exam levels are outlined in Table 2 (above). Similar to the history component, other visit categories, such as critical care and discharge day management, do not have specified levels of exam or associated documentation requirements for physical exam elements. TH

Carol Pohlig is a billing and coding expert with the University of Pennsylvania Medical Center, Philadelphia. She also is on the faculty of SHM’s inpatient coding course.

Physicians only should perform patient examinations based upon the presenting problem and the standard of care. As mentioned in my previous column (April 2008, p. 21), the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) and the American Medical Association (AMA) set forth two sets of documentation guidelines. The biggest difference between them is the exam component.

1995 Guidelines

The 1995 guidelines distinguish 10 body areas (head and face; neck; chest, breast, and axillae; abdomen; genitalia, groin, and buttocks; back and spine; right upper extremity; left upper extremity; right lower extremity; and left lower extremity) from 12 organ systems (constitutional; eyes; ears, nose, mouth, and throat; cardiovascular; respiratory; gastrointestinal; genitourinary; musculoskeletal; integumentary; neurological; psychiatric; hematologic, lymphatic, and immunologic).

Further, these guidelines let physicians document their findings in any manner while adhering to some simple rules:

- Document relevant negative findings. Commenting that a system or area is “negative” or “normal” is acceptable when referring to unaffected areas or asymptomatic organ systems; and

- Elaborate on abnormal findings. Commenting that a system or area is “abnormal” is not sufficient unless additional comments describing the abnormality are documented.

1997 Guidelines

The 1997 guidelines comprise bulleted items—referred to as elements—that correspond to each organ system. Some elements specify numeric criterion that must be met to credit the physician for documentation of that element.

For example, the physician only receives credit for documentation of vital signs (an element of the constitutional system) when three measurements are referenced (e.g., blood pressure, heart rate, and respiratory rate). Documentation that does not include three measurements or only contains a single generalized comment (e.g., vital signs stable) cannot be credited to the physician in the 1997 guidelines—even though these same comments are credited when applying the 1995 guidelines.

This logic also applies to the lymphatic system. The physician must identify findings associated with at least two lymphatic areas examined (e.g., “no lymphadenopathy of the neck or axillae”).

Elements that do not contain numeric criterion but identify multiple components require documentation of at least one component. For example, one psychiatric element involves the assessment of the patient’s “mood and affect.” If the physician comments that the patient appears depressed but does not comment on a flat (or normal) affect, the physician still receives credit for this exam element.

Levels of Exam

There are four levels of exam, determined by the number of elements documented in the progress note (see Tables 1A and 1B, p. below).

As with the history component, the physician must meet the requirements for a particular level of exam before assigning it. The most problematic feature of the 1995 guidelines involves the “detailed” exam. Both the expanded problem-focused and detailed exams involve two to seven systems/areas, but the detailed exam requires an “extended” exam of the affected system/area related to the presenting problem. Questions surround the number of elements needed to qualify as an “extended” exam of the affected system/area.

Does “regular rate and rhythm; normal S1, S2; no jugular venous distention; no murmur, gallop, or rub; peripheral pulses intact; no edema noted” constitute an “extended” exam of the cardiovascular system, or should there be an additional comment regarding the abdominal aorta? This decision is left to the discretion of the local Medicare contractor and/or the medical reviewer.

Since no other CMS directive has been provided, documentation of the detailed exam continues to be inconsistent. More importantly, review and audit of the detailed exam remains arbitrary. Some Medicare contractors suggest using the 1997 requirements for the detailed exam, while others create their own definition and corresponding number of exam elements needed for documentation of the detailed exam. This issue exemplifies the ambiguity for which the 1995 guidelines often are criticized.

Meanwhile, the 1997 guidelines often are criticized as too specific. While this may help the medical reviewer/auditor, it hinders the physician. Physicians are frequently frustrated trying to remember the explicit comments and number of elements associated with a particular level of exam.

One solution is documentation templates. Physicians can use paper or electronic templates that incorporate cues and prompts for normal exam findings, incorporating adequate space to elaborate abnormal findings.

Remember the physician has the option of utilizing either the 1995 or 1997 guidelines, depending upon which set he perceives as easier to implement.

Additionally, auditors must review physician documentation using both the 1995 and 1997 guidelines, and apply the most favorable result to the final audit score.

Each type of evaluation and management service identifies a specific level of exam that must be documented in the medical record before the associated CPT code is submitted on a claim.

The most common visit categories provided by hospitalists and corresponding exam levels are outlined in Table 2 (above). Similar to the history component, other visit categories, such as critical care and discharge day management, do not have specified levels of exam or associated documentation requirements for physical exam elements. TH

Carol Pohlig is a billing and coding expert with the University of Pennsylvania Medical Center, Philadelphia. She also is on the faculty of SHM’s inpatient coding course.

Physicians only should perform patient examinations based upon the presenting problem and the standard of care. As mentioned in my previous column (April 2008, p. 21), the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) and the American Medical Association (AMA) set forth two sets of documentation guidelines. The biggest difference between them is the exam component.

1995 Guidelines

The 1995 guidelines distinguish 10 body areas (head and face; neck; chest, breast, and axillae; abdomen; genitalia, groin, and buttocks; back and spine; right upper extremity; left upper extremity; right lower extremity; and left lower extremity) from 12 organ systems (constitutional; eyes; ears, nose, mouth, and throat; cardiovascular; respiratory; gastrointestinal; genitourinary; musculoskeletal; integumentary; neurological; psychiatric; hematologic, lymphatic, and immunologic).

Further, these guidelines let physicians document their findings in any manner while adhering to some simple rules:

- Document relevant negative findings. Commenting that a system or area is “negative” or “normal” is acceptable when referring to unaffected areas or asymptomatic organ systems; and

- Elaborate on abnormal findings. Commenting that a system or area is “abnormal” is not sufficient unless additional comments describing the abnormality are documented.

1997 Guidelines

The 1997 guidelines comprise bulleted items—referred to as elements—that correspond to each organ system. Some elements specify numeric criterion that must be met to credit the physician for documentation of that element.

For example, the physician only receives credit for documentation of vital signs (an element of the constitutional system) when three measurements are referenced (e.g., blood pressure, heart rate, and respiratory rate). Documentation that does not include three measurements or only contains a single generalized comment (e.g., vital signs stable) cannot be credited to the physician in the 1997 guidelines—even though these same comments are credited when applying the 1995 guidelines.

This logic also applies to the lymphatic system. The physician must identify findings associated with at least two lymphatic areas examined (e.g., “no lymphadenopathy of the neck or axillae”).

Elements that do not contain numeric criterion but identify multiple components require documentation of at least one component. For example, one psychiatric element involves the assessment of the patient’s “mood and affect.” If the physician comments that the patient appears depressed but does not comment on a flat (or normal) affect, the physician still receives credit for this exam element.

Levels of Exam

There are four levels of exam, determined by the number of elements documented in the progress note (see Tables 1A and 1B, p. below).

As with the history component, the physician must meet the requirements for a particular level of exam before assigning it. The most problematic feature of the 1995 guidelines involves the “detailed” exam. Both the expanded problem-focused and detailed exams involve two to seven systems/areas, but the detailed exam requires an “extended” exam of the affected system/area related to the presenting problem. Questions surround the number of elements needed to qualify as an “extended” exam of the affected system/area.

Does “regular rate and rhythm; normal S1, S2; no jugular venous distention; no murmur, gallop, or rub; peripheral pulses intact; no edema noted” constitute an “extended” exam of the cardiovascular system, or should there be an additional comment regarding the abdominal aorta? This decision is left to the discretion of the local Medicare contractor and/or the medical reviewer.

Since no other CMS directive has been provided, documentation of the detailed exam continues to be inconsistent. More importantly, review and audit of the detailed exam remains arbitrary. Some Medicare contractors suggest using the 1997 requirements for the detailed exam, while others create their own definition and corresponding number of exam elements needed for documentation of the detailed exam. This issue exemplifies the ambiguity for which the 1995 guidelines often are criticized.

Meanwhile, the 1997 guidelines often are criticized as too specific. While this may help the medical reviewer/auditor, it hinders the physician. Physicians are frequently frustrated trying to remember the explicit comments and number of elements associated with a particular level of exam.

One solution is documentation templates. Physicians can use paper or electronic templates that incorporate cues and prompts for normal exam findings, incorporating adequate space to elaborate abnormal findings.

Remember the physician has the option of utilizing either the 1995 or 1997 guidelines, depending upon which set he perceives as easier to implement.

Additionally, auditors must review physician documentation using both the 1995 and 1997 guidelines, and apply the most favorable result to the final audit score.

Each type of evaluation and management service identifies a specific level of exam that must be documented in the medical record before the associated CPT code is submitted on a claim.

The most common visit categories provided by hospitalists and corresponding exam levels are outlined in Table 2 (above). Similar to the history component, other visit categories, such as critical care and discharge day management, do not have specified levels of exam or associated documentation requirements for physical exam elements. TH

Carol Pohlig is a billing and coding expert with the University of Pennsylvania Medical Center, Philadelphia. She also is on the faculty of SHM’s inpatient coding course.