User login

Renal vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism

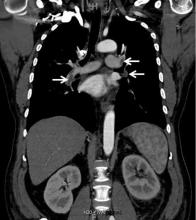

A 49-year-old man developed nephrotic-range proteinuria (urine protein–creatinine ratio 4.1 g/g), and primary membranous nephropathy was diagnosed by kidney biopsy. He declined therapy apart from angiotensin receptor blockade.

Five months after undergoing the biopsy, he presented to the emergency room with marked dyspnea, cough, and epigastric discomfort. His blood pressure was 160/100 mm Hg, heart rate 95 beats/minute, and oxygen saturation by pulse oximetry 97% at rest on ambient air, decreasing to 92% with ambulation.

Initial laboratory testing results were as follows:

- Sodium 135 mmol/L (reference range 136–144)

- Potassium 3.9 mmol/L (3.7–5.1)

- Chloride 104 mmol/L (97–105)

- Bicarbonate 21 mmol/L (22–30)

- Blood urea nitrogen 14 mg/dL (9–24)

- Serum creatinine 1.1 mg/dL (0.73–1.22)

- Albumin 2.1 g/dL (3.4–4.9).

Urinalysis revealed the following:

- 5 red blood cells per high-power field, compared with 1 to 2 previously

- 3+ proteinuria

- Urine protein–creatinine ratio 11 g/g

- No glucosuria.

Electrocardiography revealed normal sinus rhythm without ischemic changes. Chest radiography did not show consolidation.

At 7 months after the thrombotic event, there was no evidence of residual renal vein thrombosis on magnetic resonance venography, and at 14 months his serum creatinine level was 0.9 mg/dL, albumin 4.0 g/dL, and urine protein–creatinine ratio 0.8 g/g.

RENAL VEIN THROMBOSIS: RISK FACTORS AND CLINICAL FEATURES

Severe hypoalbuminemia in the setting of nephrotic syndrome due to membranous nephropathy is associated with the highest risk of venous thromboembolic events, with renal vein thrombus being the classic complication.1 Venous thromboembolic events also occur in other nephrotic syndromes, albeit at a lower frequency.2

Venous thromboembolic events are estimated to occur in 7% to 33% of patients with membranous glomerulopathy, with albumin levels less than 2.8 g/dL considered a notable risk factor.1,2

While often a chronic complication, acute renal vein thrombosis may present with flank pain and hematuria.3 In our patient, the dramatic increase in proteinuria and possibly the increase in hematuria suggested renal vein thrombosis. Proximal tubular dysfunction, such as glucosuria, can be seen on occasion.

DIAGNOSIS AND TREATMENT

Screening asymptomatic patients for renal vein thrombosis is not recommended, and the decision to start prophylactic anticoagulation must be individualized.4

Although renal venography historically was the gold standard test to diagnose renal vein thrombosis, it has been replaced by noninvasive imaging such as computed tomography and magnetic resonance venography.

While anticoagulation remains the treatment of choice, catheter-directed thrombectomy or surgical thrombectomy can be considered for some patients with acute renal vein thrombosis.5

- Couser WG. Primary membranous nephropathy. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2017; 12(6):983–997. doi:10.2215/CJN.11761116

- Barbour SJ, Greenwald A, Djurdjev O, et al. Disease-specific risk of venous thromboembolic events is increased in idiopathic glomerulonephritis. Kidney Int 2012; 81(2):190–195. doi:10.1038/ki.2011.312

- Lionaki S, Derebail VK, Hogan SL, et al. Venous thromboembolism in patients with membranous nephropathy. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2012; 7(1):43–51. doi:10.2215/CJN.04250511

- Lee T, Biddle AK, Lionaki S, et al. Personalized prophylactic anticoagulation decision analysis in patients with membranous nephropathy. Kidney Int 2014; 85(6):1412–1420. doi:10.1038/ki.2013.476

- Jaar BG, Kim HS, Samaniego MD, Lund GB, Atta MG. Percutaneous mechanical thrombectomy: a new approach in the treatment of acute renal-vein thrombosis. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2002; 17(6):1122–1125. pmid:12032209

A 49-year-old man developed nephrotic-range proteinuria (urine protein–creatinine ratio 4.1 g/g), and primary membranous nephropathy was diagnosed by kidney biopsy. He declined therapy apart from angiotensin receptor blockade.

Five months after undergoing the biopsy, he presented to the emergency room with marked dyspnea, cough, and epigastric discomfort. His blood pressure was 160/100 mm Hg, heart rate 95 beats/minute, and oxygen saturation by pulse oximetry 97% at rest on ambient air, decreasing to 92% with ambulation.

Initial laboratory testing results were as follows:

- Sodium 135 mmol/L (reference range 136–144)

- Potassium 3.9 mmol/L (3.7–5.1)

- Chloride 104 mmol/L (97–105)

- Bicarbonate 21 mmol/L (22–30)

- Blood urea nitrogen 14 mg/dL (9–24)

- Serum creatinine 1.1 mg/dL (0.73–1.22)

- Albumin 2.1 g/dL (3.4–4.9).

Urinalysis revealed the following:

- 5 red blood cells per high-power field, compared with 1 to 2 previously

- 3+ proteinuria

- Urine protein–creatinine ratio 11 g/g

- No glucosuria.

Electrocardiography revealed normal sinus rhythm without ischemic changes. Chest radiography did not show consolidation.

At 7 months after the thrombotic event, there was no evidence of residual renal vein thrombosis on magnetic resonance venography, and at 14 months his serum creatinine level was 0.9 mg/dL, albumin 4.0 g/dL, and urine protein–creatinine ratio 0.8 g/g.

RENAL VEIN THROMBOSIS: RISK FACTORS AND CLINICAL FEATURES

Severe hypoalbuminemia in the setting of nephrotic syndrome due to membranous nephropathy is associated with the highest risk of venous thromboembolic events, with renal vein thrombus being the classic complication.1 Venous thromboembolic events also occur in other nephrotic syndromes, albeit at a lower frequency.2

Venous thromboembolic events are estimated to occur in 7% to 33% of patients with membranous glomerulopathy, with albumin levels less than 2.8 g/dL considered a notable risk factor.1,2

While often a chronic complication, acute renal vein thrombosis may present with flank pain and hematuria.3 In our patient, the dramatic increase in proteinuria and possibly the increase in hematuria suggested renal vein thrombosis. Proximal tubular dysfunction, such as glucosuria, can be seen on occasion.

DIAGNOSIS AND TREATMENT

Screening asymptomatic patients for renal vein thrombosis is not recommended, and the decision to start prophylactic anticoagulation must be individualized.4

Although renal venography historically was the gold standard test to diagnose renal vein thrombosis, it has been replaced by noninvasive imaging such as computed tomography and magnetic resonance venography.

While anticoagulation remains the treatment of choice, catheter-directed thrombectomy or surgical thrombectomy can be considered for some patients with acute renal vein thrombosis.5

A 49-year-old man developed nephrotic-range proteinuria (urine protein–creatinine ratio 4.1 g/g), and primary membranous nephropathy was diagnosed by kidney biopsy. He declined therapy apart from angiotensin receptor blockade.

Five months after undergoing the biopsy, he presented to the emergency room with marked dyspnea, cough, and epigastric discomfort. His blood pressure was 160/100 mm Hg, heart rate 95 beats/minute, and oxygen saturation by pulse oximetry 97% at rest on ambient air, decreasing to 92% with ambulation.

Initial laboratory testing results were as follows:

- Sodium 135 mmol/L (reference range 136–144)

- Potassium 3.9 mmol/L (3.7–5.1)

- Chloride 104 mmol/L (97–105)

- Bicarbonate 21 mmol/L (22–30)

- Blood urea nitrogen 14 mg/dL (9–24)

- Serum creatinine 1.1 mg/dL (0.73–1.22)

- Albumin 2.1 g/dL (3.4–4.9).

Urinalysis revealed the following:

- 5 red blood cells per high-power field, compared with 1 to 2 previously

- 3+ proteinuria

- Urine protein–creatinine ratio 11 g/g

- No glucosuria.

Electrocardiography revealed normal sinus rhythm without ischemic changes. Chest radiography did not show consolidation.

At 7 months after the thrombotic event, there was no evidence of residual renal vein thrombosis on magnetic resonance venography, and at 14 months his serum creatinine level was 0.9 mg/dL, albumin 4.0 g/dL, and urine protein–creatinine ratio 0.8 g/g.

RENAL VEIN THROMBOSIS: RISK FACTORS AND CLINICAL FEATURES

Severe hypoalbuminemia in the setting of nephrotic syndrome due to membranous nephropathy is associated with the highest risk of venous thromboembolic events, with renal vein thrombus being the classic complication.1 Venous thromboembolic events also occur in other nephrotic syndromes, albeit at a lower frequency.2

Venous thromboembolic events are estimated to occur in 7% to 33% of patients with membranous glomerulopathy, with albumin levels less than 2.8 g/dL considered a notable risk factor.1,2

While often a chronic complication, acute renal vein thrombosis may present with flank pain and hematuria.3 In our patient, the dramatic increase in proteinuria and possibly the increase in hematuria suggested renal vein thrombosis. Proximal tubular dysfunction, such as glucosuria, can be seen on occasion.

DIAGNOSIS AND TREATMENT

Screening asymptomatic patients for renal vein thrombosis is not recommended, and the decision to start prophylactic anticoagulation must be individualized.4

Although renal venography historically was the gold standard test to diagnose renal vein thrombosis, it has been replaced by noninvasive imaging such as computed tomography and magnetic resonance venography.

While anticoagulation remains the treatment of choice, catheter-directed thrombectomy or surgical thrombectomy can be considered for some patients with acute renal vein thrombosis.5

- Couser WG. Primary membranous nephropathy. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2017; 12(6):983–997. doi:10.2215/CJN.11761116

- Barbour SJ, Greenwald A, Djurdjev O, et al. Disease-specific risk of venous thromboembolic events is increased in idiopathic glomerulonephritis. Kidney Int 2012; 81(2):190–195. doi:10.1038/ki.2011.312

- Lionaki S, Derebail VK, Hogan SL, et al. Venous thromboembolism in patients with membranous nephropathy. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2012; 7(1):43–51. doi:10.2215/CJN.04250511

- Lee T, Biddle AK, Lionaki S, et al. Personalized prophylactic anticoagulation decision analysis in patients with membranous nephropathy. Kidney Int 2014; 85(6):1412–1420. doi:10.1038/ki.2013.476

- Jaar BG, Kim HS, Samaniego MD, Lund GB, Atta MG. Percutaneous mechanical thrombectomy: a new approach in the treatment of acute renal-vein thrombosis. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2002; 17(6):1122–1125. pmid:12032209

- Couser WG. Primary membranous nephropathy. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2017; 12(6):983–997. doi:10.2215/CJN.11761116

- Barbour SJ, Greenwald A, Djurdjev O, et al. Disease-specific risk of venous thromboembolic events is increased in idiopathic glomerulonephritis. Kidney Int 2012; 81(2):190–195. doi:10.1038/ki.2011.312

- Lionaki S, Derebail VK, Hogan SL, et al. Venous thromboembolism in patients with membranous nephropathy. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2012; 7(1):43–51. doi:10.2215/CJN.04250511

- Lee T, Biddle AK, Lionaki S, et al. Personalized prophylactic anticoagulation decision analysis in patients with membranous nephropathy. Kidney Int 2014; 85(6):1412–1420. doi:10.1038/ki.2013.476

- Jaar BG, Kim HS, Samaniego MD, Lund GB, Atta MG. Percutaneous mechanical thrombectomy: a new approach in the treatment of acute renal-vein thrombosis. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2002; 17(6):1122–1125. pmid:12032209

Urinary Excretion Indices in AKI

The Things We Do for No Reason (TWDFNR) series reviews practices which have become common parts of hospital care but which may provide little value to our patients. Practices reviewed in the TWDFNR series do not represent black and white conclusions or clinical practice standards, but are meant as a starting place for research and active discussions among hospitalists and patients. We invite you to be part of that discussion. https://www.choosingwisely.org/

A 70‐year‐old woman with a history of diabetes mellitus type 2 and hypertension was admitted with abdominal pain following 2 days of nausea and diarrhea. Initial laboratory studies revealed blood urea nitrogen (BUN) 25 mg/dL and serum creatinine 1.3 mg/dL. Computed tomography of the abdomen and pelvis with nonionic, low osmolar intravenous and oral contrast demonstrated acute diverticulitis with an associated small abscess. She was administered intravenous 0.9% sodium chloride solution and antibiotics. Blood pressure on admission was 92/55 mm Hg, and 24 hours later, her BUN and serum creatinine increased to 33 mg/dL and 1.9 mg/dL, respectively. Her urine output during the preceding 24 hours was 500 mL.

In the evaluation of acute kidney injury (AKI), is the measurement of fractional excretion of sodium (FeNa) and fractional excretion of urea (FeUr) of value?

WHY YOU MIGHT THINK ORDERING FeNa AND/OR FeUr IN THE EVALUATION OF AKI IS HELPFUL

The proper maintenance of sodium balance is paramount to regulating the size of body fluid compartments. Through the interaction of multiple physiologic processes, the kidney regulates tubular reabsorption (or lack thereof) of sodium chloride to match excretion to intake. In normal health, FeNa is typically 1%, although it may vary depending on the dietary sodium intake. The corollary is that 99% of filtered sodium is reabsorbed. Acute tubular injury (ATI) that impairs the tubular resorptive capacity for sodium may increase FeNa to >3%. In addition, during states of water conservation, urea is reabsorbed from the medullary collecting duct, explaining the discrepant rise in BUN relative to creatinine in prerenal azotemia. FeUr falls progressively as water is reabsorbed and urine flow declines, and FeUr less than 35% to 40% may result during prerenal azotemia versus >50% in health or ATI. Theoretically, FeUr is largely unaffected by diuretics, whereas FeNa is increased by diuretics.

In 1976, Espinel reported on the use of FeNa in 17 oliguric patients to discriminate prerenal azotemia from ATI.[1] Establishing what are now familiar indices, FeNa <1% was deemed consistent with prerenal physiology versus >3% indicating ATI. Notably, the study excluded patients who had received diuretics or in whom chronic kidney disease (CKD), glomerulonephritis, or urinary obstruction was suspected.

Given the limitations of FeNa in the context of diuretic use, many physicians instead use FeUr to distinguish prerenal versus ATI causes of AKI. Carvounis et al. reported FeUr and FeNa in 50 patients with prerenal azotemia, 27 with prerenal azotemia receiving diuretics and 25 patients with ATI.[2] Patients with interstitial nephritis, glomerulonephritis, and obstruction were excluded. In the entire cohort, the authors reported sensitivity of 90% and specificity of 96% for FeUr <35% in identifying prerenal azotemia (Table 1). FeNa <1% was slightly less sensitive for prerenal azotemia in the entire cohort at 77%, and this fell to 48% in the presence of diuretics as compared to 89% for FeUr. Naturally, the specificity of FeNa for ATI will fall with the use of diuretics. As shown in Table 1, FeUr <35% has an excellent positive likelihood ratio (LR+) of 22 for prerenal azotemia and a moderate LR+ of 9 for FeUr 35% being consistent with ATI, regardless of the presence of diuretics. This contrasts with FeNa, which if 1% in the presence of diuretics, lacked utility in the diagnosis of ATI. Of note, diuretic use was reported only in the prerenal azotemia group and not specifically in the ATI group. Thus, these comparisons assume diuretics have no effect on test characteristics in ATI. This assumption, however, may not be valid.

| FeUr | FeNa | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sens | Spec | PPV | NPV | LR+ | LR | Sens | Spec | PPV | NPV | LR+ | LR | |||

| ||||||||||||||

| Carvounis[2] | Prerenal | Overall | 0.90 | 0.96 | 0.99 | 0.75 | 22.4 | 0.1 | 0.77 | 0.96 | 0.98 | 0.57 | 19.2 | 0.2 |

| No diuretics | 0.90 | 0.96 | 0.98 | 0.83 | 22.5 | 0.1 | 0.92 | 0.96 | 0.98 | 0.86 | 23.0 | 0.1 | ||

| Diuretics | 0.89 | 0.96 | 0.96 | 0.89 | 22.2 | 0.1 | 0.48 | 0.96 | 0.93 | 0.63 | 12.0 | 0.5 | ||

| ATI | Overall | 0.96 | 0.90 | 0.75 | 0.99 | 9.2 | 0.0 | 0.96 | 0.77 | 0.57 | 0.98 | 4.1 | 0.1 | |

| No diuretics* | 0.96 | 0.90 | 0.83 | 0.98 | 9.6 | 0.0 | 0.96 | 0.92 | 0.86 | 0.98 | 12.0 | 0.0 | ||

| Diuretics | 0.96 | 0.89 | 0.89 | 0.96 | 8.6 | 0.0 | 0.96 | 0.48 | 0.63 | 0.93 | 1.9 | 0.1 | ||

| Diskin[8] | Prerenal | Overall | 0.97 | 0.85 | 0.96 | 0.89 | 6.5 | 0.0 | 0.44 | 0.75 | 0.88 | 0.25 | 1.8 | 0.7 |

| No diuretics | 0.91 | 0.89 | 0.95 | 0.80 | 8.2 | 0.1 | 0.83 | 0.67 | 0.86 | 0.60 | 2.5 | 0.3 | ||

| Diuretics | 1.00 | 0.82 | 0.97 | 1.00 | 5.5 | 0.0 | 0.29 | 0.82 | 0.89 | 0.18 | 1.6 | 0.9 | ||

| ATI | Overall | 0.85 | 0.97 | 0.89 | 0.96 | 33.6 | 0.2 | 0.75 | 0.44 | 0.25 | 0.88 | 1.3 | 0.6 | |

| No diuretics | 0.89 | 0.91 | 0.80 | 0.95 | 10.2 | 0.1 | 0.67 | 0.83 | 0.60 | 0.86 | 3.8 | 0.4 | ||

| Diuretics | 0.82 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.97 | N/A | 0.2 | 0.82 | 0.29 | 0.18 | 0.89 | 1.1 | 0.6 | ||

WHY THERE IS LITTLE REASON TO ROUTINELY ORDER FeNa AND FeUr IN PATIENTS WITH AKI

The argument against FeNa and FeUr is not primarily financial. FeNa and FeUr testing on all Medicare patients discharged with AKI in 2013 would have cost US$6 million.[3] Although a tiny fraction of annual healthcare expenditure, it would nevertheless be wasteful spending, and its true harm lays in the application of flawed diagnostic reasoning.

That flaw in our conceptual approach to AKI is the broad categorization of patients into either a prerenal or intrinsic etiology of AKI. In reality, renal injury is often multifactorial, and significant prerenal injury may progress to or coexist with intrinsic disease that is commonly ATI. Measurement of a urinary index at a single point in time will often fail to capture this spectrum of causes for AKI. Unfortunately, accurately assessing volume status through physical examination is difficult.[4] Considering FeNa and FeUr may be low in both hemorrhage as well as congestive heart failure, the measurement of these variables adds little to body volume assessment.

It cannot be overemphasized that application of FeNa and FeUr is predicated on the provider already knowing the diagnosis is either prerenal azotemia or ATI. Studies have generally excluded patients >65 years old and those with CKD or notable comorbid renal processes apart from prerenal azotemia or ATI. It is important to recall that a third of kidney biopsies may yield a diagnosis different than the prebiopsy clinical diagnosis, and the gold standard for ATI in studies of FeNa and FeUr was simply a failure of kidney function to improve promptly.[5] Why send a test that is predicated on largely already knowing the answer?

Fractional Excretion of Sodium for Diagnosis

Unfortunately, FeNa is neither sensitive nor specific enough in the general inpatient population to inform important clinical decisions regarding the etiology of AKI. Miller et al. examined 30 patients with oliguric prerenal azotemia, 55 with ATI (oliguric and nonoliguric), 10 with obstructive uropathy, and 7 with glomerulonephritis.[6] None of the patients had received diuretics within 24 hours of study entry. A FeNa <1% was present in 90% of prerenal patients and 4% of oliguric ATI. Importantly, of nonoliguric patients with ATI, 10% had a false positive FeNa <1%. Many subsequent studies have similarly documented the existence of FeNa <1% or otherwise indeterminate in ATI, particularly, but not exclusively, in nonoliguric states.[7] Diskin et al. evaluated FeNa in 100 prospective oliguric AKI patients (80 with prerenal azotemia and 20 with ATI) without CKD, with FeNa <1% being consistent with prerenal azotemia, 1% to 3% indeterminate, and >3% ATI.[8] The derived LR for FeNa for both prerenal azotemia and ATI are unlikely to alter pretest probability (Table 1). In part, this may be due to Diskin et al.'s incorporation of indeterminate FeNa, consistent with clinical reality. Carvounis et al. did not account for indeterminate values, and consequently the LR were likely overinflated in that study. It is now well‐recognized that glomerulonephritis may also result in FeNa <1% despite absence of identifiable prerenal physiology, as can intravenous iodinated contrast administration and rhabdomyolysis. Moreover, diuretic administration, polyuria due to osmotic diuresis, increased excretion of anions such as ketone bodies in diabetic ketoacidosis, the presence of CKD, and increased age, among others, can produce an FeNa that is indeterminate or >3% in the absence of ATI. Regarding diuretics, although the duration of action of furosemide is approximately 6 hours, longer‐acting loop diuretics such as torsemide or thiazide diuretics such as chlorthalidone may result in natriuresis for 24 hours.

Fractional Excretion of Urea for Diagnosis

Despite the potential superiority of FeUr to FeNa in supporting a diagnosis of prerenal azotemia in the setting of diuretic administration, FeUr nevertheless will only moderately increase the post‐test probability of prerenal azotemia under ideal conditions. In the study by Diskin et al., FeUr <40% was deemed consistent with prerenal azotemia and 40% with ATI. In the diagnosis of prerenal azotemia, the LR+ were 5.5 and 8.2 in the presence and absence of diuretics, respectively. Although the LR+ for the diagnosis of ATI was impressive, this was based on only 9 patients in the ATI‐no diuretic and 11 patients in the ATI‐diuretic groups. Carvounis, moreover, demonstrated considerably lower LR+ of approximately 9 for the diagnosis of ATI, and this study was unable to account for diuretic use specifically within the ATI group. Four of the 5 prerenal patients in Diskin et al.'s study misdiagnosed by FeUr had infection, and each were properly diagnosed by FeNa. Experimental data suggest endotoxemia may downregulate urea transporters as does aging, thereby increasing FeUr in sepsis and the elderly even in times of prerenal azotemia.[9, 10] Moreover, osmotic diuresis, such as with hyperglycemia or sickle cell nephropathy with medullary injury, may result in a falsely negative FeUr during prerenal states. In summary, these data suggest FeUr less than 35% to 40%, with the noted caveats, is most applicable to an oliguric patient in whom the pretest probability of prerenal azotemia is high, and it may be superior in the context of diuretics to the use of FeNa. Nonetheless, the impact on posttest probability is marginal. Of note, the diagnostic categories lack gold standards in these studies, and in the Carvounis study, FeNa (index under study) was 1 of several criteria actually used to categorize patients as either prerenal or ATI (outcomes under study). It is important to recognize these datasets contained very small numbers of patients with ATI, limiting the strength and generalizability of the scientific evidence. Other studies have failed to consistently demonstrate any utility to FeUr, particularly in those with CKD or critical illness.[11, 12, 13, 14, 15]

WHAT YOU SHOULD DO INSTEAD: DECIDE IF VOLUME MANIPULATION IS APPROPRIATE

The gold standard for diagnosis, as in many of the above studies, is the prompt improvement of prerenal azotemia with correction of renal hypoperfusion. Ultimately, the decision to administer intravenous fluids or diuretics in the management of AKI will often be independent of both FeNa and FeUr. In considering, for example, the case described above, it is not possible to realistically dichotomize the patient into either a prerenal or ATI category; both are quite likely present. If the clinical assessment supports a component of prerenal azotemia, a low FeNa and/or FeUr will not change the intervention. An elevated FeNa and/or FeUr, however, has at best moderate and potentially no impact on the likelihood for ATI. A patient, moreover, may still require volume manipulation in the context of established ATI. As such, these indices should not alter therapeutic decisions. There may be value in utilizing and identifying new approaches to determining a priori which patients will be fluid responsive, such as inferior vena cava ultrasound.[16] Lastly, evaluation of the urine sediment is an underutilized tool that may prove more useful in discriminating prerenal azotemia from ATI. It also helps to exclude other etiologies of AKI, such as glomerulonephritis and acute interstitial nephritis, which are typical exclusion criteria in studies of FeNa and FeUr.[17, 18]

WHEN IS FeNa AND/OR FeUr USEFUL IN DEFINING THE ETIOLOGY OF AKI?

FeNa and FeUr at best only support a clinical impression of prerenal azotemia or ATI in oliguric AKI, and the accuracy of these metrics is questionable in the setting of CKD, older age, and a variety of comorbidities. There is, however, a setting in which FeNa may be helpful. In practice, FeNa is useful in the evaluation of hepatorenal syndrome, a disorder characterized by oliguria and intense renal sodium reabsorption with resultant spot urine sodium <10 mEq/L and FeNa <1%.[19]

CONCLUSION

The evidence base supporting the use of FeNa and FeUr is limited and often not generalizable to many patients with AKI. The small sample sizes of the studies do not permit adequate capture of diverse mechanisms for renal injury, and these studies are of patients referred for Nephrology consultation and may not be representative of the larger population of patients with less severe AKI. Ultimately, the true etiology will be proven by time and response to therapy. Apart from a supportive role in the diagnosis of hepatorenal syndrome, there is little practical utility to FeNa and FeUr measurement, and these indices should not alter therapeutic decisions when inconsistent with the clinical impression. The evaluation of AKI requires thoughtful clinical assessment, and the gold standard still remains the judicious decision of when to manipulate the intravascular volume status of a patient. In regard to the presented case, urine chemistries are unhelpful due to the combined vasoconstrictive and tubulotoxic effects of the administered intravenous contrast. The ongoing hypotension further contributes to both pre‐renal as well as ischemic tubular injury.

RECOMMENDATIONS

- FeNa can aid in the diagnosis of hepatorenal syndrome. Otherwise, the routine use of FeNa and FeUr in the diagnosis and management of AKI should be avoided.

- In pre‐renal azotemia, therapeutic intervention is guided by etiology of the disorder (e.g., intravenous crystalloid support based on a history of hypovolemia and ongoing hypoperfusion, diuresis and/or inotropic support in setting of decompensated heart failure, etc.), without regard to baseline FeNa and FeUr.

- In ATI, fluid administration is appropriate if hypovolemia is present. FeNa and FeUr cannot diagnose hypovolemia.

Disclosure

Nothing to report.

Do you think this is a low‐value practice? Is this truly a Thing We Do for No Reason? Share what you do in your practice and join in the conversation online by retweeting it on Twitter (#TWDFNR) and liking it on Facebook. We invite you to propose ideas for other Things We Do for No Reason topics by emailing TWDFNR@hospitalmedicine.org.

- . The FENa test. Use in the differential diagnosis of acute renal failure. JAMA. 1976;236(6):579–581.

- , , . Significance of the fractional excretion of urea in the differential diagnosis of acute renal failure. Kidney Int. 2002;62(6):2223–2229.

- Centers for Medicare 275(8):630–634.

- , , , . Etiologies and outcome of acute renal insufficiency in older adults: a renal biopsy study of 259 cases. Am J Kidney Dis. 2000;35(3):433–447.

- , , , et al. Urinary diagnostic indices in acute renal failure: a prospective study. Ann Intern Med. 1978;89(1):47–50.

- , . Urinary indices and chemistries in the differential diagnosis of prerenal failure and acute tubular necrosis. Semin Nephrol. 1985;5(3):224–233.

- , , , , . The comparative benefits of the fractional excretion of urea and sodium in various azotemic oliguric states. Nephron Clin Pract. 2010;114(2):c145–c150.

- MachasNúñez JF, Cameron JS, Oreopoulos DG, eds. The Aging Kidney in Health and Disease. New York, NY: Springer Science + Business Media, LLC; 2008.

- , , . Cytokine‐mediated regulation of urea transporters during experimental endotoxemia. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2007;292(5):F1479–F1489.

- , , . Urinary biochemistry and microscopy in septic acute renal failure: a systematic review. Am J Kidney Dis. 2006;48(5):695–705.

- , , , et al. Diagnostic performance of fractional excretion of urea in the evaluation of critically ill patients with acute kidney injury: a multicenter cohort study. Crit Care. 2011;15(4):R178.

- , , , et al. Fractional excretion of urea as a diagnostic index in acute kidney injury in intensive care patients. J Crit Care. 2012;27(5):505–510.

- , , , . Diagnostic performance of fractional excretion of urea and fractional excretion of sodium in the evaluations of patients with acute kidney injury with or without diuretic treatment. Am J Kidney Dis. 2007;50(4):566–573.

- , , , et al. Transient versus persistent acute kidney injury and the diagnostic performance of fractional excretion of urea in critically ill patients. Nephron Clin Pract. 2014;126(1):8–13.

- , , , , . Emergency department bedside ultrasonographic measurement of the caval index for noninvasive determination of low central venous pressure. Ann Emerg Med. 2010;55(3):290–295.

- , , , , , . Urine microscopy is associated with severity and worsening of acute kidney injury in hospitalized patients. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;5(3):402–408.

- , , , , . Diagnostic value of urine microscopy for differential diagnosis of acute kidney injury in hospitalized patients. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;3(6):1615–1619.

- , , , et al. Definition and diagnostic criteria of refractory ascites and hepatorenal syndrome in cirrhosis. International Ascites Club. Hepatology. 1996;23(1):164–176.

The Things We Do for No Reason (TWDFNR) series reviews practices which have become common parts of hospital care but which may provide little value to our patients. Practices reviewed in the TWDFNR series do not represent black and white conclusions or clinical practice standards, but are meant as a starting place for research and active discussions among hospitalists and patients. We invite you to be part of that discussion. https://www.choosingwisely.org/

A 70‐year‐old woman with a history of diabetes mellitus type 2 and hypertension was admitted with abdominal pain following 2 days of nausea and diarrhea. Initial laboratory studies revealed blood urea nitrogen (BUN) 25 mg/dL and serum creatinine 1.3 mg/dL. Computed tomography of the abdomen and pelvis with nonionic, low osmolar intravenous and oral contrast demonstrated acute diverticulitis with an associated small abscess. She was administered intravenous 0.9% sodium chloride solution and antibiotics. Blood pressure on admission was 92/55 mm Hg, and 24 hours later, her BUN and serum creatinine increased to 33 mg/dL and 1.9 mg/dL, respectively. Her urine output during the preceding 24 hours was 500 mL.

In the evaluation of acute kidney injury (AKI), is the measurement of fractional excretion of sodium (FeNa) and fractional excretion of urea (FeUr) of value?

WHY YOU MIGHT THINK ORDERING FeNa AND/OR FeUr IN THE EVALUATION OF AKI IS HELPFUL

The proper maintenance of sodium balance is paramount to regulating the size of body fluid compartments. Through the interaction of multiple physiologic processes, the kidney regulates tubular reabsorption (or lack thereof) of sodium chloride to match excretion to intake. In normal health, FeNa is typically 1%, although it may vary depending on the dietary sodium intake. The corollary is that 99% of filtered sodium is reabsorbed. Acute tubular injury (ATI) that impairs the tubular resorptive capacity for sodium may increase FeNa to >3%. In addition, during states of water conservation, urea is reabsorbed from the medullary collecting duct, explaining the discrepant rise in BUN relative to creatinine in prerenal azotemia. FeUr falls progressively as water is reabsorbed and urine flow declines, and FeUr less than 35% to 40% may result during prerenal azotemia versus >50% in health or ATI. Theoretically, FeUr is largely unaffected by diuretics, whereas FeNa is increased by diuretics.

In 1976, Espinel reported on the use of FeNa in 17 oliguric patients to discriminate prerenal azotemia from ATI.[1] Establishing what are now familiar indices, FeNa <1% was deemed consistent with prerenal physiology versus >3% indicating ATI. Notably, the study excluded patients who had received diuretics or in whom chronic kidney disease (CKD), glomerulonephritis, or urinary obstruction was suspected.

Given the limitations of FeNa in the context of diuretic use, many physicians instead use FeUr to distinguish prerenal versus ATI causes of AKI. Carvounis et al. reported FeUr and FeNa in 50 patients with prerenal azotemia, 27 with prerenal azotemia receiving diuretics and 25 patients with ATI.[2] Patients with interstitial nephritis, glomerulonephritis, and obstruction were excluded. In the entire cohort, the authors reported sensitivity of 90% and specificity of 96% for FeUr <35% in identifying prerenal azotemia (Table 1). FeNa <1% was slightly less sensitive for prerenal azotemia in the entire cohort at 77%, and this fell to 48% in the presence of diuretics as compared to 89% for FeUr. Naturally, the specificity of FeNa for ATI will fall with the use of diuretics. As shown in Table 1, FeUr <35% has an excellent positive likelihood ratio (LR+) of 22 for prerenal azotemia and a moderate LR+ of 9 for FeUr 35% being consistent with ATI, regardless of the presence of diuretics. This contrasts with FeNa, which if 1% in the presence of diuretics, lacked utility in the diagnosis of ATI. Of note, diuretic use was reported only in the prerenal azotemia group and not specifically in the ATI group. Thus, these comparisons assume diuretics have no effect on test characteristics in ATI. This assumption, however, may not be valid.

| FeUr | FeNa | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sens | Spec | PPV | NPV | LR+ | LR | Sens | Spec | PPV | NPV | LR+ | LR | |||

| ||||||||||||||

| Carvounis[2] | Prerenal | Overall | 0.90 | 0.96 | 0.99 | 0.75 | 22.4 | 0.1 | 0.77 | 0.96 | 0.98 | 0.57 | 19.2 | 0.2 |

| No diuretics | 0.90 | 0.96 | 0.98 | 0.83 | 22.5 | 0.1 | 0.92 | 0.96 | 0.98 | 0.86 | 23.0 | 0.1 | ||

| Diuretics | 0.89 | 0.96 | 0.96 | 0.89 | 22.2 | 0.1 | 0.48 | 0.96 | 0.93 | 0.63 | 12.0 | 0.5 | ||

| ATI | Overall | 0.96 | 0.90 | 0.75 | 0.99 | 9.2 | 0.0 | 0.96 | 0.77 | 0.57 | 0.98 | 4.1 | 0.1 | |

| No diuretics* | 0.96 | 0.90 | 0.83 | 0.98 | 9.6 | 0.0 | 0.96 | 0.92 | 0.86 | 0.98 | 12.0 | 0.0 | ||

| Diuretics | 0.96 | 0.89 | 0.89 | 0.96 | 8.6 | 0.0 | 0.96 | 0.48 | 0.63 | 0.93 | 1.9 | 0.1 | ||

| Diskin[8] | Prerenal | Overall | 0.97 | 0.85 | 0.96 | 0.89 | 6.5 | 0.0 | 0.44 | 0.75 | 0.88 | 0.25 | 1.8 | 0.7 |

| No diuretics | 0.91 | 0.89 | 0.95 | 0.80 | 8.2 | 0.1 | 0.83 | 0.67 | 0.86 | 0.60 | 2.5 | 0.3 | ||

| Diuretics | 1.00 | 0.82 | 0.97 | 1.00 | 5.5 | 0.0 | 0.29 | 0.82 | 0.89 | 0.18 | 1.6 | 0.9 | ||

| ATI | Overall | 0.85 | 0.97 | 0.89 | 0.96 | 33.6 | 0.2 | 0.75 | 0.44 | 0.25 | 0.88 | 1.3 | 0.6 | |

| No diuretics | 0.89 | 0.91 | 0.80 | 0.95 | 10.2 | 0.1 | 0.67 | 0.83 | 0.60 | 0.86 | 3.8 | 0.4 | ||

| Diuretics | 0.82 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.97 | N/A | 0.2 | 0.82 | 0.29 | 0.18 | 0.89 | 1.1 | 0.6 | ||

WHY THERE IS LITTLE REASON TO ROUTINELY ORDER FeNa AND FeUr IN PATIENTS WITH AKI

The argument against FeNa and FeUr is not primarily financial. FeNa and FeUr testing on all Medicare patients discharged with AKI in 2013 would have cost US$6 million.[3] Although a tiny fraction of annual healthcare expenditure, it would nevertheless be wasteful spending, and its true harm lays in the application of flawed diagnostic reasoning.

That flaw in our conceptual approach to AKI is the broad categorization of patients into either a prerenal or intrinsic etiology of AKI. In reality, renal injury is often multifactorial, and significant prerenal injury may progress to or coexist with intrinsic disease that is commonly ATI. Measurement of a urinary index at a single point in time will often fail to capture this spectrum of causes for AKI. Unfortunately, accurately assessing volume status through physical examination is difficult.[4] Considering FeNa and FeUr may be low in both hemorrhage as well as congestive heart failure, the measurement of these variables adds little to body volume assessment.

It cannot be overemphasized that application of FeNa and FeUr is predicated on the provider already knowing the diagnosis is either prerenal azotemia or ATI. Studies have generally excluded patients >65 years old and those with CKD or notable comorbid renal processes apart from prerenal azotemia or ATI. It is important to recall that a third of kidney biopsies may yield a diagnosis different than the prebiopsy clinical diagnosis, and the gold standard for ATI in studies of FeNa and FeUr was simply a failure of kidney function to improve promptly.[5] Why send a test that is predicated on largely already knowing the answer?

Fractional Excretion of Sodium for Diagnosis

Unfortunately, FeNa is neither sensitive nor specific enough in the general inpatient population to inform important clinical decisions regarding the etiology of AKI. Miller et al. examined 30 patients with oliguric prerenal azotemia, 55 with ATI (oliguric and nonoliguric), 10 with obstructive uropathy, and 7 with glomerulonephritis.[6] None of the patients had received diuretics within 24 hours of study entry. A FeNa <1% was present in 90% of prerenal patients and 4% of oliguric ATI. Importantly, of nonoliguric patients with ATI, 10% had a false positive FeNa <1%. Many subsequent studies have similarly documented the existence of FeNa <1% or otherwise indeterminate in ATI, particularly, but not exclusively, in nonoliguric states.[7] Diskin et al. evaluated FeNa in 100 prospective oliguric AKI patients (80 with prerenal azotemia and 20 with ATI) without CKD, with FeNa <1% being consistent with prerenal azotemia, 1% to 3% indeterminate, and >3% ATI.[8] The derived LR for FeNa for both prerenal azotemia and ATI are unlikely to alter pretest probability (Table 1). In part, this may be due to Diskin et al.'s incorporation of indeterminate FeNa, consistent with clinical reality. Carvounis et al. did not account for indeterminate values, and consequently the LR were likely overinflated in that study. It is now well‐recognized that glomerulonephritis may also result in FeNa <1% despite absence of identifiable prerenal physiology, as can intravenous iodinated contrast administration and rhabdomyolysis. Moreover, diuretic administration, polyuria due to osmotic diuresis, increased excretion of anions such as ketone bodies in diabetic ketoacidosis, the presence of CKD, and increased age, among others, can produce an FeNa that is indeterminate or >3% in the absence of ATI. Regarding diuretics, although the duration of action of furosemide is approximately 6 hours, longer‐acting loop diuretics such as torsemide or thiazide diuretics such as chlorthalidone may result in natriuresis for 24 hours.

Fractional Excretion of Urea for Diagnosis

Despite the potential superiority of FeUr to FeNa in supporting a diagnosis of prerenal azotemia in the setting of diuretic administration, FeUr nevertheless will only moderately increase the post‐test probability of prerenal azotemia under ideal conditions. In the study by Diskin et al., FeUr <40% was deemed consistent with prerenal azotemia and 40% with ATI. In the diagnosis of prerenal azotemia, the LR+ were 5.5 and 8.2 in the presence and absence of diuretics, respectively. Although the LR+ for the diagnosis of ATI was impressive, this was based on only 9 patients in the ATI‐no diuretic and 11 patients in the ATI‐diuretic groups. Carvounis, moreover, demonstrated considerably lower LR+ of approximately 9 for the diagnosis of ATI, and this study was unable to account for diuretic use specifically within the ATI group. Four of the 5 prerenal patients in Diskin et al.'s study misdiagnosed by FeUr had infection, and each were properly diagnosed by FeNa. Experimental data suggest endotoxemia may downregulate urea transporters as does aging, thereby increasing FeUr in sepsis and the elderly even in times of prerenal azotemia.[9, 10] Moreover, osmotic diuresis, such as with hyperglycemia or sickle cell nephropathy with medullary injury, may result in a falsely negative FeUr during prerenal states. In summary, these data suggest FeUr less than 35% to 40%, with the noted caveats, is most applicable to an oliguric patient in whom the pretest probability of prerenal azotemia is high, and it may be superior in the context of diuretics to the use of FeNa. Nonetheless, the impact on posttest probability is marginal. Of note, the diagnostic categories lack gold standards in these studies, and in the Carvounis study, FeNa (index under study) was 1 of several criteria actually used to categorize patients as either prerenal or ATI (outcomes under study). It is important to recognize these datasets contained very small numbers of patients with ATI, limiting the strength and generalizability of the scientific evidence. Other studies have failed to consistently demonstrate any utility to FeUr, particularly in those with CKD or critical illness.[11, 12, 13, 14, 15]

WHAT YOU SHOULD DO INSTEAD: DECIDE IF VOLUME MANIPULATION IS APPROPRIATE

The gold standard for diagnosis, as in many of the above studies, is the prompt improvement of prerenal azotemia with correction of renal hypoperfusion. Ultimately, the decision to administer intravenous fluids or diuretics in the management of AKI will often be independent of both FeNa and FeUr. In considering, for example, the case described above, it is not possible to realistically dichotomize the patient into either a prerenal or ATI category; both are quite likely present. If the clinical assessment supports a component of prerenal azotemia, a low FeNa and/or FeUr will not change the intervention. An elevated FeNa and/or FeUr, however, has at best moderate and potentially no impact on the likelihood for ATI. A patient, moreover, may still require volume manipulation in the context of established ATI. As such, these indices should not alter therapeutic decisions. There may be value in utilizing and identifying new approaches to determining a priori which patients will be fluid responsive, such as inferior vena cava ultrasound.[16] Lastly, evaluation of the urine sediment is an underutilized tool that may prove more useful in discriminating prerenal azotemia from ATI. It also helps to exclude other etiologies of AKI, such as glomerulonephritis and acute interstitial nephritis, which are typical exclusion criteria in studies of FeNa and FeUr.[17, 18]

WHEN IS FeNa AND/OR FeUr USEFUL IN DEFINING THE ETIOLOGY OF AKI?

FeNa and FeUr at best only support a clinical impression of prerenal azotemia or ATI in oliguric AKI, and the accuracy of these metrics is questionable in the setting of CKD, older age, and a variety of comorbidities. There is, however, a setting in which FeNa may be helpful. In practice, FeNa is useful in the evaluation of hepatorenal syndrome, a disorder characterized by oliguria and intense renal sodium reabsorption with resultant spot urine sodium <10 mEq/L and FeNa <1%.[19]

CONCLUSION

The evidence base supporting the use of FeNa and FeUr is limited and often not generalizable to many patients with AKI. The small sample sizes of the studies do not permit adequate capture of diverse mechanisms for renal injury, and these studies are of patients referred for Nephrology consultation and may not be representative of the larger population of patients with less severe AKI. Ultimately, the true etiology will be proven by time and response to therapy. Apart from a supportive role in the diagnosis of hepatorenal syndrome, there is little practical utility to FeNa and FeUr measurement, and these indices should not alter therapeutic decisions when inconsistent with the clinical impression. The evaluation of AKI requires thoughtful clinical assessment, and the gold standard still remains the judicious decision of when to manipulate the intravascular volume status of a patient. In regard to the presented case, urine chemistries are unhelpful due to the combined vasoconstrictive and tubulotoxic effects of the administered intravenous contrast. The ongoing hypotension further contributes to both pre‐renal as well as ischemic tubular injury.

RECOMMENDATIONS

- FeNa can aid in the diagnosis of hepatorenal syndrome. Otherwise, the routine use of FeNa and FeUr in the diagnosis and management of AKI should be avoided.

- In pre‐renal azotemia, therapeutic intervention is guided by etiology of the disorder (e.g., intravenous crystalloid support based on a history of hypovolemia and ongoing hypoperfusion, diuresis and/or inotropic support in setting of decompensated heart failure, etc.), without regard to baseline FeNa and FeUr.

- In ATI, fluid administration is appropriate if hypovolemia is present. FeNa and FeUr cannot diagnose hypovolemia.

Disclosure

Nothing to report.

Do you think this is a low‐value practice? Is this truly a Thing We Do for No Reason? Share what you do in your practice and join in the conversation online by retweeting it on Twitter (#TWDFNR) and liking it on Facebook. We invite you to propose ideas for other Things We Do for No Reason topics by emailing TWDFNR@hospitalmedicine.org.

The Things We Do for No Reason (TWDFNR) series reviews practices which have become common parts of hospital care but which may provide little value to our patients. Practices reviewed in the TWDFNR series do not represent black and white conclusions or clinical practice standards, but are meant as a starting place for research and active discussions among hospitalists and patients. We invite you to be part of that discussion. https://www.choosingwisely.org/

A 70‐year‐old woman with a history of diabetes mellitus type 2 and hypertension was admitted with abdominal pain following 2 days of nausea and diarrhea. Initial laboratory studies revealed blood urea nitrogen (BUN) 25 mg/dL and serum creatinine 1.3 mg/dL. Computed tomography of the abdomen and pelvis with nonionic, low osmolar intravenous and oral contrast demonstrated acute diverticulitis with an associated small abscess. She was administered intravenous 0.9% sodium chloride solution and antibiotics. Blood pressure on admission was 92/55 mm Hg, and 24 hours later, her BUN and serum creatinine increased to 33 mg/dL and 1.9 mg/dL, respectively. Her urine output during the preceding 24 hours was 500 mL.

In the evaluation of acute kidney injury (AKI), is the measurement of fractional excretion of sodium (FeNa) and fractional excretion of urea (FeUr) of value?

WHY YOU MIGHT THINK ORDERING FeNa AND/OR FeUr IN THE EVALUATION OF AKI IS HELPFUL

The proper maintenance of sodium balance is paramount to regulating the size of body fluid compartments. Through the interaction of multiple physiologic processes, the kidney regulates tubular reabsorption (or lack thereof) of sodium chloride to match excretion to intake. In normal health, FeNa is typically 1%, although it may vary depending on the dietary sodium intake. The corollary is that 99% of filtered sodium is reabsorbed. Acute tubular injury (ATI) that impairs the tubular resorptive capacity for sodium may increase FeNa to >3%. In addition, during states of water conservation, urea is reabsorbed from the medullary collecting duct, explaining the discrepant rise in BUN relative to creatinine in prerenal azotemia. FeUr falls progressively as water is reabsorbed and urine flow declines, and FeUr less than 35% to 40% may result during prerenal azotemia versus >50% in health or ATI. Theoretically, FeUr is largely unaffected by diuretics, whereas FeNa is increased by diuretics.

In 1976, Espinel reported on the use of FeNa in 17 oliguric patients to discriminate prerenal azotemia from ATI.[1] Establishing what are now familiar indices, FeNa <1% was deemed consistent with prerenal physiology versus >3% indicating ATI. Notably, the study excluded patients who had received diuretics or in whom chronic kidney disease (CKD), glomerulonephritis, or urinary obstruction was suspected.

Given the limitations of FeNa in the context of diuretic use, many physicians instead use FeUr to distinguish prerenal versus ATI causes of AKI. Carvounis et al. reported FeUr and FeNa in 50 patients with prerenal azotemia, 27 with prerenal azotemia receiving diuretics and 25 patients with ATI.[2] Patients with interstitial nephritis, glomerulonephritis, and obstruction were excluded. In the entire cohort, the authors reported sensitivity of 90% and specificity of 96% for FeUr <35% in identifying prerenal azotemia (Table 1). FeNa <1% was slightly less sensitive for prerenal azotemia in the entire cohort at 77%, and this fell to 48% in the presence of diuretics as compared to 89% for FeUr. Naturally, the specificity of FeNa for ATI will fall with the use of diuretics. As shown in Table 1, FeUr <35% has an excellent positive likelihood ratio (LR+) of 22 for prerenal azotemia and a moderate LR+ of 9 for FeUr 35% being consistent with ATI, regardless of the presence of diuretics. This contrasts with FeNa, which if 1% in the presence of diuretics, lacked utility in the diagnosis of ATI. Of note, diuretic use was reported only in the prerenal azotemia group and not specifically in the ATI group. Thus, these comparisons assume diuretics have no effect on test characteristics in ATI. This assumption, however, may not be valid.

| FeUr | FeNa | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sens | Spec | PPV | NPV | LR+ | LR | Sens | Spec | PPV | NPV | LR+ | LR | |||

| ||||||||||||||

| Carvounis[2] | Prerenal | Overall | 0.90 | 0.96 | 0.99 | 0.75 | 22.4 | 0.1 | 0.77 | 0.96 | 0.98 | 0.57 | 19.2 | 0.2 |

| No diuretics | 0.90 | 0.96 | 0.98 | 0.83 | 22.5 | 0.1 | 0.92 | 0.96 | 0.98 | 0.86 | 23.0 | 0.1 | ||

| Diuretics | 0.89 | 0.96 | 0.96 | 0.89 | 22.2 | 0.1 | 0.48 | 0.96 | 0.93 | 0.63 | 12.0 | 0.5 | ||

| ATI | Overall | 0.96 | 0.90 | 0.75 | 0.99 | 9.2 | 0.0 | 0.96 | 0.77 | 0.57 | 0.98 | 4.1 | 0.1 | |

| No diuretics* | 0.96 | 0.90 | 0.83 | 0.98 | 9.6 | 0.0 | 0.96 | 0.92 | 0.86 | 0.98 | 12.0 | 0.0 | ||

| Diuretics | 0.96 | 0.89 | 0.89 | 0.96 | 8.6 | 0.0 | 0.96 | 0.48 | 0.63 | 0.93 | 1.9 | 0.1 | ||

| Diskin[8] | Prerenal | Overall | 0.97 | 0.85 | 0.96 | 0.89 | 6.5 | 0.0 | 0.44 | 0.75 | 0.88 | 0.25 | 1.8 | 0.7 |

| No diuretics | 0.91 | 0.89 | 0.95 | 0.80 | 8.2 | 0.1 | 0.83 | 0.67 | 0.86 | 0.60 | 2.5 | 0.3 | ||

| Diuretics | 1.00 | 0.82 | 0.97 | 1.00 | 5.5 | 0.0 | 0.29 | 0.82 | 0.89 | 0.18 | 1.6 | 0.9 | ||

| ATI | Overall | 0.85 | 0.97 | 0.89 | 0.96 | 33.6 | 0.2 | 0.75 | 0.44 | 0.25 | 0.88 | 1.3 | 0.6 | |

| No diuretics | 0.89 | 0.91 | 0.80 | 0.95 | 10.2 | 0.1 | 0.67 | 0.83 | 0.60 | 0.86 | 3.8 | 0.4 | ||

| Diuretics | 0.82 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.97 | N/A | 0.2 | 0.82 | 0.29 | 0.18 | 0.89 | 1.1 | 0.6 | ||

WHY THERE IS LITTLE REASON TO ROUTINELY ORDER FeNa AND FeUr IN PATIENTS WITH AKI

The argument against FeNa and FeUr is not primarily financial. FeNa and FeUr testing on all Medicare patients discharged with AKI in 2013 would have cost US$6 million.[3] Although a tiny fraction of annual healthcare expenditure, it would nevertheless be wasteful spending, and its true harm lays in the application of flawed diagnostic reasoning.

That flaw in our conceptual approach to AKI is the broad categorization of patients into either a prerenal or intrinsic etiology of AKI. In reality, renal injury is often multifactorial, and significant prerenal injury may progress to or coexist with intrinsic disease that is commonly ATI. Measurement of a urinary index at a single point in time will often fail to capture this spectrum of causes for AKI. Unfortunately, accurately assessing volume status through physical examination is difficult.[4] Considering FeNa and FeUr may be low in both hemorrhage as well as congestive heart failure, the measurement of these variables adds little to body volume assessment.

It cannot be overemphasized that application of FeNa and FeUr is predicated on the provider already knowing the diagnosis is either prerenal azotemia or ATI. Studies have generally excluded patients >65 years old and those with CKD or notable comorbid renal processes apart from prerenal azotemia or ATI. It is important to recall that a third of kidney biopsies may yield a diagnosis different than the prebiopsy clinical diagnosis, and the gold standard for ATI in studies of FeNa and FeUr was simply a failure of kidney function to improve promptly.[5] Why send a test that is predicated on largely already knowing the answer?

Fractional Excretion of Sodium for Diagnosis

Unfortunately, FeNa is neither sensitive nor specific enough in the general inpatient population to inform important clinical decisions regarding the etiology of AKI. Miller et al. examined 30 patients with oliguric prerenal azotemia, 55 with ATI (oliguric and nonoliguric), 10 with obstructive uropathy, and 7 with glomerulonephritis.[6] None of the patients had received diuretics within 24 hours of study entry. A FeNa <1% was present in 90% of prerenal patients and 4% of oliguric ATI. Importantly, of nonoliguric patients with ATI, 10% had a false positive FeNa <1%. Many subsequent studies have similarly documented the existence of FeNa <1% or otherwise indeterminate in ATI, particularly, but not exclusively, in nonoliguric states.[7] Diskin et al. evaluated FeNa in 100 prospective oliguric AKI patients (80 with prerenal azotemia and 20 with ATI) without CKD, with FeNa <1% being consistent with prerenal azotemia, 1% to 3% indeterminate, and >3% ATI.[8] The derived LR for FeNa for both prerenal azotemia and ATI are unlikely to alter pretest probability (Table 1). In part, this may be due to Diskin et al.'s incorporation of indeterminate FeNa, consistent with clinical reality. Carvounis et al. did not account for indeterminate values, and consequently the LR were likely overinflated in that study. It is now well‐recognized that glomerulonephritis may also result in FeNa <1% despite absence of identifiable prerenal physiology, as can intravenous iodinated contrast administration and rhabdomyolysis. Moreover, diuretic administration, polyuria due to osmotic diuresis, increased excretion of anions such as ketone bodies in diabetic ketoacidosis, the presence of CKD, and increased age, among others, can produce an FeNa that is indeterminate or >3% in the absence of ATI. Regarding diuretics, although the duration of action of furosemide is approximately 6 hours, longer‐acting loop diuretics such as torsemide or thiazide diuretics such as chlorthalidone may result in natriuresis for 24 hours.

Fractional Excretion of Urea for Diagnosis

Despite the potential superiority of FeUr to FeNa in supporting a diagnosis of prerenal azotemia in the setting of diuretic administration, FeUr nevertheless will only moderately increase the post‐test probability of prerenal azotemia under ideal conditions. In the study by Diskin et al., FeUr <40% was deemed consistent with prerenal azotemia and 40% with ATI. In the diagnosis of prerenal azotemia, the LR+ were 5.5 and 8.2 in the presence and absence of diuretics, respectively. Although the LR+ for the diagnosis of ATI was impressive, this was based on only 9 patients in the ATI‐no diuretic and 11 patients in the ATI‐diuretic groups. Carvounis, moreover, demonstrated considerably lower LR+ of approximately 9 for the diagnosis of ATI, and this study was unable to account for diuretic use specifically within the ATI group. Four of the 5 prerenal patients in Diskin et al.'s study misdiagnosed by FeUr had infection, and each were properly diagnosed by FeNa. Experimental data suggest endotoxemia may downregulate urea transporters as does aging, thereby increasing FeUr in sepsis and the elderly even in times of prerenal azotemia.[9, 10] Moreover, osmotic diuresis, such as with hyperglycemia or sickle cell nephropathy with medullary injury, may result in a falsely negative FeUr during prerenal states. In summary, these data suggest FeUr less than 35% to 40%, with the noted caveats, is most applicable to an oliguric patient in whom the pretest probability of prerenal azotemia is high, and it may be superior in the context of diuretics to the use of FeNa. Nonetheless, the impact on posttest probability is marginal. Of note, the diagnostic categories lack gold standards in these studies, and in the Carvounis study, FeNa (index under study) was 1 of several criteria actually used to categorize patients as either prerenal or ATI (outcomes under study). It is important to recognize these datasets contained very small numbers of patients with ATI, limiting the strength and generalizability of the scientific evidence. Other studies have failed to consistently demonstrate any utility to FeUr, particularly in those with CKD or critical illness.[11, 12, 13, 14, 15]

WHAT YOU SHOULD DO INSTEAD: DECIDE IF VOLUME MANIPULATION IS APPROPRIATE

The gold standard for diagnosis, as in many of the above studies, is the prompt improvement of prerenal azotemia with correction of renal hypoperfusion. Ultimately, the decision to administer intravenous fluids or diuretics in the management of AKI will often be independent of both FeNa and FeUr. In considering, for example, the case described above, it is not possible to realistically dichotomize the patient into either a prerenal or ATI category; both are quite likely present. If the clinical assessment supports a component of prerenal azotemia, a low FeNa and/or FeUr will not change the intervention. An elevated FeNa and/or FeUr, however, has at best moderate and potentially no impact on the likelihood for ATI. A patient, moreover, may still require volume manipulation in the context of established ATI. As such, these indices should not alter therapeutic decisions. There may be value in utilizing and identifying new approaches to determining a priori which patients will be fluid responsive, such as inferior vena cava ultrasound.[16] Lastly, evaluation of the urine sediment is an underutilized tool that may prove more useful in discriminating prerenal azotemia from ATI. It also helps to exclude other etiologies of AKI, such as glomerulonephritis and acute interstitial nephritis, which are typical exclusion criteria in studies of FeNa and FeUr.[17, 18]

WHEN IS FeNa AND/OR FeUr USEFUL IN DEFINING THE ETIOLOGY OF AKI?

FeNa and FeUr at best only support a clinical impression of prerenal azotemia or ATI in oliguric AKI, and the accuracy of these metrics is questionable in the setting of CKD, older age, and a variety of comorbidities. There is, however, a setting in which FeNa may be helpful. In practice, FeNa is useful in the evaluation of hepatorenal syndrome, a disorder characterized by oliguria and intense renal sodium reabsorption with resultant spot urine sodium <10 mEq/L and FeNa <1%.[19]

CONCLUSION

The evidence base supporting the use of FeNa and FeUr is limited and often not generalizable to many patients with AKI. The small sample sizes of the studies do not permit adequate capture of diverse mechanisms for renal injury, and these studies are of patients referred for Nephrology consultation and may not be representative of the larger population of patients with less severe AKI. Ultimately, the true etiology will be proven by time and response to therapy. Apart from a supportive role in the diagnosis of hepatorenal syndrome, there is little practical utility to FeNa and FeUr measurement, and these indices should not alter therapeutic decisions when inconsistent with the clinical impression. The evaluation of AKI requires thoughtful clinical assessment, and the gold standard still remains the judicious decision of when to manipulate the intravascular volume status of a patient. In regard to the presented case, urine chemistries are unhelpful due to the combined vasoconstrictive and tubulotoxic effects of the administered intravenous contrast. The ongoing hypotension further contributes to both pre‐renal as well as ischemic tubular injury.

RECOMMENDATIONS

- FeNa can aid in the diagnosis of hepatorenal syndrome. Otherwise, the routine use of FeNa and FeUr in the diagnosis and management of AKI should be avoided.

- In pre‐renal azotemia, therapeutic intervention is guided by etiology of the disorder (e.g., intravenous crystalloid support based on a history of hypovolemia and ongoing hypoperfusion, diuresis and/or inotropic support in setting of decompensated heart failure, etc.), without regard to baseline FeNa and FeUr.

- In ATI, fluid administration is appropriate if hypovolemia is present. FeNa and FeUr cannot diagnose hypovolemia.

Disclosure

Nothing to report.

Do you think this is a low‐value practice? Is this truly a Thing We Do for No Reason? Share what you do in your practice and join in the conversation online by retweeting it on Twitter (#TWDFNR) and liking it on Facebook. We invite you to propose ideas for other Things We Do for No Reason topics by emailing TWDFNR@hospitalmedicine.org.

- . The FENa test. Use in the differential diagnosis of acute renal failure. JAMA. 1976;236(6):579–581.

- , , . Significance of the fractional excretion of urea in the differential diagnosis of acute renal failure. Kidney Int. 2002;62(6):2223–2229.

- Centers for Medicare 275(8):630–634.

- , , , . Etiologies and outcome of acute renal insufficiency in older adults: a renal biopsy study of 259 cases. Am J Kidney Dis. 2000;35(3):433–447.

- , , , et al. Urinary diagnostic indices in acute renal failure: a prospective study. Ann Intern Med. 1978;89(1):47–50.

- , . Urinary indices and chemistries in the differential diagnosis of prerenal failure and acute tubular necrosis. Semin Nephrol. 1985;5(3):224–233.

- , , , , . The comparative benefits of the fractional excretion of urea and sodium in various azotemic oliguric states. Nephron Clin Pract. 2010;114(2):c145–c150.

- MachasNúñez JF, Cameron JS, Oreopoulos DG, eds. The Aging Kidney in Health and Disease. New York, NY: Springer Science + Business Media, LLC; 2008.

- , , . Cytokine‐mediated regulation of urea transporters during experimental endotoxemia. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2007;292(5):F1479–F1489.

- , , . Urinary biochemistry and microscopy in septic acute renal failure: a systematic review. Am J Kidney Dis. 2006;48(5):695–705.

- , , , et al. Diagnostic performance of fractional excretion of urea in the evaluation of critically ill patients with acute kidney injury: a multicenter cohort study. Crit Care. 2011;15(4):R178.

- , , , et al. Fractional excretion of urea as a diagnostic index in acute kidney injury in intensive care patients. J Crit Care. 2012;27(5):505–510.

- , , , . Diagnostic performance of fractional excretion of urea and fractional excretion of sodium in the evaluations of patients with acute kidney injury with or without diuretic treatment. Am J Kidney Dis. 2007;50(4):566–573.

- , , , et al. Transient versus persistent acute kidney injury and the diagnostic performance of fractional excretion of urea in critically ill patients. Nephron Clin Pract. 2014;126(1):8–13.

- , , , , . Emergency department bedside ultrasonographic measurement of the caval index for noninvasive determination of low central venous pressure. Ann Emerg Med. 2010;55(3):290–295.

- , , , , , . Urine microscopy is associated with severity and worsening of acute kidney injury in hospitalized patients. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;5(3):402–408.

- , , , , . Diagnostic value of urine microscopy for differential diagnosis of acute kidney injury in hospitalized patients. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;3(6):1615–1619.

- , , , et al. Definition and diagnostic criteria of refractory ascites and hepatorenal syndrome in cirrhosis. International Ascites Club. Hepatology. 1996;23(1):164–176.

- . The FENa test. Use in the differential diagnosis of acute renal failure. JAMA. 1976;236(6):579–581.

- , , . Significance of the fractional excretion of urea in the differential diagnosis of acute renal failure. Kidney Int. 2002;62(6):2223–2229.

- Centers for Medicare 275(8):630–634.

- , , , . Etiologies and outcome of acute renal insufficiency in older adults: a renal biopsy study of 259 cases. Am J Kidney Dis. 2000;35(3):433–447.

- , , , et al. Urinary diagnostic indices in acute renal failure: a prospective study. Ann Intern Med. 1978;89(1):47–50.

- , . Urinary indices and chemistries in the differential diagnosis of prerenal failure and acute tubular necrosis. Semin Nephrol. 1985;5(3):224–233.

- , , , , . The comparative benefits of the fractional excretion of urea and sodium in various azotemic oliguric states. Nephron Clin Pract. 2010;114(2):c145–c150.

- MachasNúñez JF, Cameron JS, Oreopoulos DG, eds. The Aging Kidney in Health and Disease. New York, NY: Springer Science + Business Media, LLC; 2008.

- , , . Cytokine‐mediated regulation of urea transporters during experimental endotoxemia. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2007;292(5):F1479–F1489.

- , , . Urinary biochemistry and microscopy in septic acute renal failure: a systematic review. Am J Kidney Dis. 2006;48(5):695–705.

- , , , et al. Diagnostic performance of fractional excretion of urea in the evaluation of critically ill patients with acute kidney injury: a multicenter cohort study. Crit Care. 2011;15(4):R178.

- , , , et al. Fractional excretion of urea as a diagnostic index in acute kidney injury in intensive care patients. J Crit Care. 2012;27(5):505–510.

- , , , . Diagnostic performance of fractional excretion of urea and fractional excretion of sodium in the evaluations of patients with acute kidney injury with or without diuretic treatment. Am J Kidney Dis. 2007;50(4):566–573.

- , , , et al. Transient versus persistent acute kidney injury and the diagnostic performance of fractional excretion of urea in critically ill patients. Nephron Clin Pract. 2014;126(1):8–13.

- , , , , . Emergency department bedside ultrasonographic measurement of the caval index for noninvasive determination of low central venous pressure. Ann Emerg Med. 2010;55(3):290–295.

- , , , , , . Urine microscopy is associated with severity and worsening of acute kidney injury in hospitalized patients. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;5(3):402–408.

- , , , , . Diagnostic value of urine microscopy for differential diagnosis of acute kidney injury in hospitalized patients. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;3(6):1615–1619.

- , , , et al. Definition and diagnostic criteria of refractory ascites and hepatorenal syndrome in cirrhosis. International Ascites Club. Hepatology. 1996;23(1):164–176.

© 2015 Society of Hospital Medicine