User login

Patch Test–Directed Dietary Avoidance in the Management of Irritable Bowel Syndrome

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is one of the most common disorders managed by primary care physicians and gastroenterologists.1 Characterized by abdominal pain coinciding with altered stool form and/or frequency as defined by the Rome IV diagnostic criteria,2 symptoms range from mild to debilitating and may remarkably impair quality of life and work productivity.1

The cause of IBS is poorly understood. Proposed pathophysiologic factors include impaired mucosal function, microbial imbalance, visceral hypersensitivity, psychologic dysfunction, genetic factors, neurotransmitter imbalance, postinfectious gastroenteritis, inflammation, and food intolerance, any or all of which may lead to the development and maintenance of IBS symptoms.3 More recent observations of inflammation in the intestinal lining4,5 and proinflammatory peripherally circulating cytokines6 challenge its traditional classification as a functional disorder.

The cause of this inflammation is of intense interest, with speculation that the bacterial microbiota, bile acids, association with postinfectious gastroenteritis and inflammatory bowel disease cases, and/or foods may contribute. Although approximately 50% of individuals with IBS report that foods aggravate their symptoms,7 studies investigating type I antibody–mediated immediate hypersensitivity have largely failed to demonstrate a substantial link, prompting many authorities to regard these associations as food “intolerances” rather than true allergies. Based on this body of literature, a large 2010 consensus report on all aspects of food allergies advises against food allergy testing for IBS.8

In contrast, by utilizing type IV food allergen skin patch testing, 2 proof-of-concept studies9,10 investigated a different allergic mechanism in IBS, namely cell-mediated delayed-type hypersensitivity. Because many foods and food additives are known to cause allergic contact dermatitis,11 it was hypothesized that these foods may elicit a similar delayed-type hypersensitivity response in the intestinal lining in previously sensitized individuals. By following a patch test–guided food avoidance diet, a large subpopulation of patients with IBS experienced partial or complete IBS symptom relief.9,10 Our study further investigates a role for food-related delayed-type hypersensitivities in the pathogenesis of IBS.

Methods

Patient Selection

This study was conducted in a secondary care community-based setting. All patients were self-referred over an 18-month period ending in October 2019, had physician-diagnosed IBS, and/or met the Rome IV criteria for IBS and presented expressly for the food patch testing on a fee-for-service basis. Subtype of IBS was determined on presentation by the self-reported historically predominant symptom. Duration of IBS symptoms was self-reported and was rounded to the nearest year for purposes of data collection.

Exclusion criteria included pregnancy, known allergy to adhesive tape or any of the food allergens used in the study, severe skin rash, symptoms that had a known cause other than IBS, or active treatment with systemic immunosuppressive medications.

Patch Testing

Skin patch testing was initiated using an extensive panel of 117 type IV food allergens (eTable)11 identified in the literature,12 most of which utilized standard compounded formulations13 or were available from reputable patch test manufacturers (Brial Allergen GmbH; Chemotechnique Diagnostics). This panel was not approved by the US Food and Drug Administration. The freeze-dried vegetable formulations were taken from the 2018 report.9 Standard skin patch test procedure protocols12 were used, affixing the patches to the upper aspect of the back.

Following patch test application on day 1, two follow-up visits occurred on day 3 and either day 4 or day 5. On day 3, patches were removed, and the initial results were read by a board-certified dermatologist according to a standard grading system.14 Interpretation of patch tests included no reaction, questionable reaction consisting of macular erythema, weak reaction consisting of erythema and slight edema, or strong reaction consisting of erythema and marked edema. On day 4 or day 5, the final patch test reading was performed, and patients were informed of their results. Patients were advised to avoid ingestion of all foods that elicited a questionable or positive patch test response for at least 3 months, and information about the foods and their avoidance also was distributed and reviewed.

Food Avoidance Questionnaire

Patients with questionable or positive patch tests at 72 or 96 hours were advised of their eligibility to participate in an institutional review board–approved food avoidance questionnaire study investigating the utility of patch test–guided food avoidance on IBS symptoms. The questionnaire assessed the following: (1) baseline average abdominal pain prior to patch test–guided avoidance diet (0=no symptoms; 10=very severe); (2) average abdominal pain since initiation of patch test–guided avoidance diet (0=no symptoms; 10=very severe); (3) degree of improvement in overall IBS symptoms by the end of the food avoidance period (0=no improvement; 10=great improvement); (4) compliance with the avoidance diet for the duration of the avoidance period (completely, partially, not at all, or not sure).

Questionnaires and informed consent were mailed to patients via the US Postal Service 3 months after completing the patch testing. The questionnaire and consent were to be completed and returned after dietary avoidance of the identified allergens for at least 3 months. Patients were not compensated for participation in the study.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis of data collected from study questionnaires was performed with Microsoft Excel. Mean abdominal pain and mean global improvement scores were reported along with 1 SD of the mean. For comparison of mean abdominal pain and improvement in global IBS symptoms from baseline to after 3 months of identified allergen avoidance, a Mann-Whitney U test was performed, with P<.05 being considered statistically significant.

Results

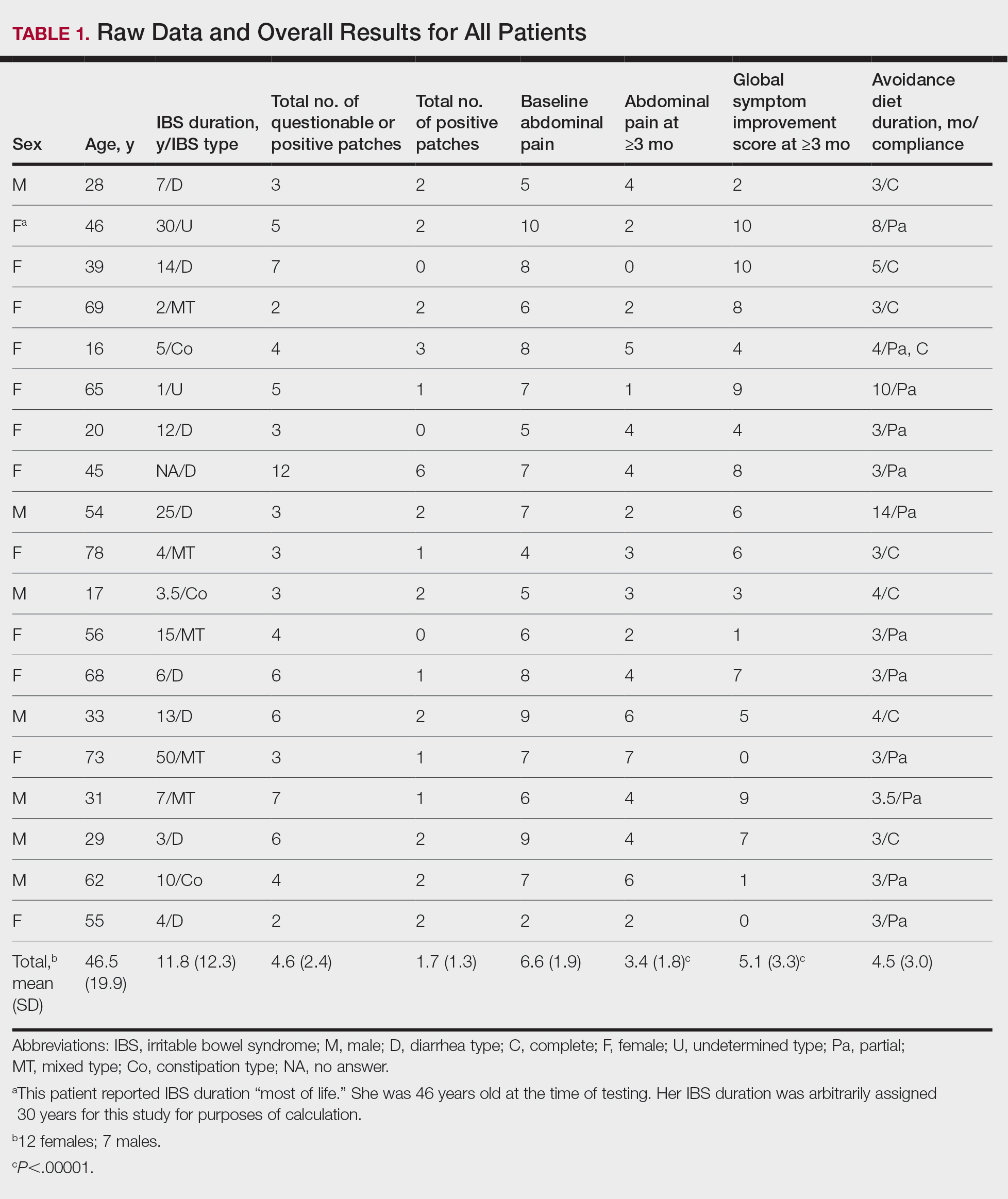

Thirty-seven consecutive patients underwent the testing and were eligible for the study. Nineteen patients were included in the study by virtue of completing and returning their posttest food avoidance questionnaire and informed consent. Eighteen patients were White and 1 was Asian. Subcategories of IBS were diarrhea predominant (9 [47.4%]), constipation predominant (3 [15.8%]), mixed type (5 [26.3%]), and undetermined type (2 [10.5%]). Questionnaire answers were reported after a mean (SD) duration of patch test–directed food avoidance of 4.5 (3.0) months (Table 1).

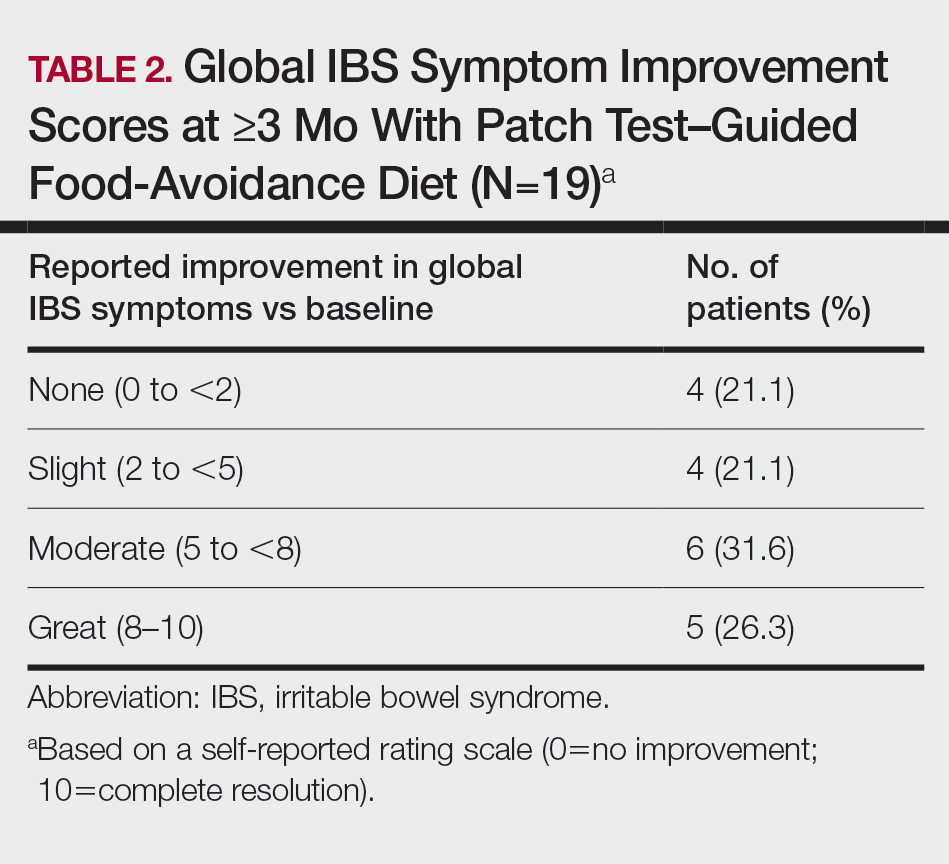

Overall Improvement

Fifteen (78.9%) patients reported at least slight to great improvement in their global IBS symptoms, and 4 (21.1%) reported no improvement (Table 2), with a mean (SD) improvement score of 5.1 (3.3)(P<.00001).

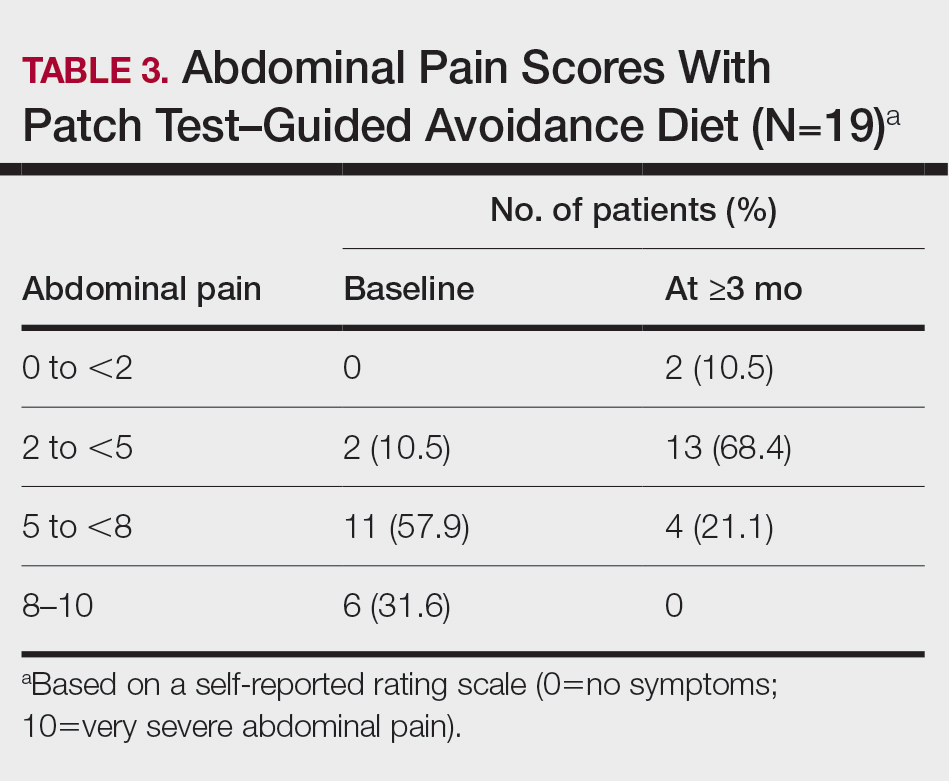

Abdominal Pain

All 19 patients reported mild to marked abdominal pain at baseline. The mean (SD) baseline pain score was 6.6 (1.9). The mean (SD) pain score was 3.4 (1.8)(P<.00001) after an average patch test–guided dietary avoidance of 4.5 (3.0) months (Table 3).

Comment

Despite intense research interest and a growing number of new medications for IBS approved by the US Food and Drug Administration, there remains a large void in the search for cost-effective and efficacious approaches for IBS evaluation and treatment. In addition to major disturbances in quality of life,14,15 the cost to society in direct medical expenses and indirect costs associated with loss of productivity and work absenteeism is considerable; estimates range from $21 billion or more annually.16

Food Hypersensitivities Triggering IBS

This study further evaluated a role for skin patch testing to identify delayed-type (type IV) food hypersensitivities that trigger IBS symptoms and differed from the prior investigations9,10 in that the symptoms used to define IBS were updated from the Rome III17 to the newer Rome IV2 criteria. The data presented here show moderate to great improvement in global IBS symptoms in 58% (11/19) of patients, which is in line with a 2018 report of 40 study participants for whom follow-up at 3 or more months was available,9 providing additional support for a role for type IV food allergies in causing the same gastrointestinal tract symptoms that define IBS. The distinction between food-related studies, including this one, that implicate food allergies9,10 and prior studies that did not support a role for food allergies in IBS pathogenesis8 can be accounted for by the type of allergy investigated. Conclusions that IBS flares after food ingestion were attributable to intolerance rather than true allergy were based on results investigating only the humoral arm and failed to consider the cell-mediated arm of the immune system. As such, foods that appear to trigger IBS symptoms on an allergic basis in our study are recognized in the literature12 as type IV allergens that elicit cell-mediated immunologic responses rather than more widely recognized type I allergens, such as peanuts and shellfish, that elicit immediate-type hypersensitivity responses. Although any type IV food allergen(s) could be responsible, a pattern emerged in this study and the study published in 2018.9 Namely, some foods stood out as more frequently inducing patch test reactions, with the 3 most common being carmine, cinnamon bark oil, and sodium bisulfite (eTable). The sample size is relatively small, but the results raise the question of whether these foods are the most likely to trigger IBS symptoms in the general population. If so, is it the result of a higher innate sensitizing potential and/or a higher frequency of exposure in commonly eaten foods? Larger randomized clinical trials are needed.

Immune Response and IBS

There is mounting evidence that the immune system may play a role in the pathophysiology of IBS.18 Both lymphocyte infiltration of the myenteric plexus and an increase in intestinal mucosal T lymphocytes have been observed, and it is generally accepted that the mucosal immune system seems to be activated, at least in a subset of patients with IBS.19 Irritable bowel syndrome associations with quiescent inflammatory bowel disease or postinfectious gastroenteritis provide 2 potential causes for the inflammation, but most IBS patients have had neither.20 The mucosal lining of the intestine and immune system have vast exposure to intraluminal allergens in transit, and it is hypothesized that the same delayed-type hypersensitivity response elicited in the skin by patch testing is elicited in the intestine, resulting in the inflammation that triggers IBS symptoms.10 The results here add to the growing body of evidence that ingestion of type IV food allergens by previously sensitized individuals could, in fact, be the primary source of the inflammation observed in a large subpopulation of individuals who carry a diagnosis of IBS.

Food Allergens in Patch Testing

Many of the food allergens used in this study are commonly found in various nonfood products that may contact the skin. For example, many flavorings are used as fragrances, and many preservatives, binders, thickeners, emulsifiers, and stabilizers serve the same role in moisturizers, cosmetics, and topical medications. Likewise, nickel sulfate hexahydrate, ubiquitous in foods that arise from the earth, often is found in metal in jewelry, clothing components, and cell phones. All are potential sensitizers. Thus, the question may arise whether the causal relationship between the food allergens identified by patch testing and IBS symptoms might be more of a systemic effect akin to systemic contact dermatitis as sometimes follows ingestion of an allergen to which an individual has been topically sensitized, rather than the proposed localized immunologic response in the intestinal lining. We were unaware of patient history of allergic contact dermatitis to any of the patch test allergens in this study, but the dermatologist author here (M.S.) has unpublished experience with 2 other patients with IBS who have benefited from low-nickel diets after having had positive patch tests to nickel sulfate hexahydrate and who, in retrospect, did report a history of earring dermatitis. Future investigations using pre– and post–food challenge histologic assessments of the intestinal mucosa in patients who benefit from patch test–guided food avoidance diets should help to better define the mechanism.

Because IBS has not been traditionally associated with structural or biochemical abnormalities detectable with current routine diagnostic tools, it has long been viewed as a functional disorder. The findings published more recently,9,10 in addition to this study’s results, would negate this functional classification in the subset of patients with IBS symptoms who experience sustained relief of their symptoms by patch test–directed food avoidance. The underlying delayed-type hypersensitivity pathogenesis of the IBS-like symptoms in these individuals would mandate an organic classification, aptly named allergic contact enteritis.10

Follow-up Data

The mean (SD) follow-up duration for this study and the 2018 report9 was 4.5 (3.0) months and 7.6 (3.9) months, respectively. The placebo effect is a concern for disorders such as IBS in which primarily subjective outcome measures are available,21 and in a retrospective analysis of 25 randomized, placebo-controlled IBS clinical trials, Spiller22 concluded the optimum length of such trials to be more than 3 months, which these studies exceed. Although not blinded or placebo controlled, the length of follow-up in the 2018 report9 and here enhances the validity of the results.

Limitation

The retrospective manner in which the self-assessments were reported in this study introduces the potential for recall bias, a variable that could affect results. The presence and direction of bias by any given individual cannot be known, making it difficult to determine any effect it may have had. Further investigation should include daily assessments and refine the primary study end points to include both abdominal pain and the defecation considerations that define IBS.

Conclusion

Food patch testing has the potential to offer a safe, cost-effective approach to the evaluation and management of IBS symptoms. Randomized clinical trials are needed to further investigate the validity of the proof-of-concept results to date. For patients who benefit from a patch test–guided avoidance diet, invasive and costly endoscopic, radiologic, and laboratory testing and pharmacologic management could be averted. Symptomatic relief could be attained simply by avoiding the implicated foods, essentially doing more by doing less.

- Enck P, Aziz Q, Barbara G, et al. Irritable bowel syndrome. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2016;2:1-24.

- Lacy BE, Patel NK. Rome criteria and a diagnostic approach to irritable bowel syndrome. J Clin Med. 2017;6:99.

- Barbara G, De Giorgio R, Stanghellini V, et al. New pathophysiological mechanisms in irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;20(suppl 2):1-9

- Chadwick VS, Chen W, Shu D, et al. Activation of the mucosal immune system in irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology 2002;122:1778-1783.

- Tornblom H, Lindberg G, Nyberg B, et al. Full-thickness biopsy of the jejunum reveals inflammation and enteric neuropathy in irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2002;123:1972-1979.

- O’Mahony L, McCarthy J, Kelly

P, et al. Lactobacillus and bifidobacterium in irritable bowel syndrome: symptom responses and relationship to cytokine profiles. Gastroenterology. 2005;128:541-551. - Ragnarsson G, Bodemar G. Pain is temporally related to eating but not to defecation in the irritable bowel syndrome (IBS): patients’ description of diarrhea, constipation and symptom variation during a prospective 6-week study. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1998;10:415-421.

- Boyce JA, Assa’ad A, Burks AW, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of food allergy in the United States: report of the NAID-sponsored expert panel. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;126(6 suppl):S1-S58.

- Shin GH, Smith MS, Toro B, et al. Utility of food patch testing in the evaluation and management of irritable bowel syndrome. Skin. 2018;2:1-15.

- Stierstorfer MB, Sha CT. Food patch testing for irritable bowel syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:377-384.

- Marks JG, Belsito DV, DeLeo MD, et al. North American Contact Dermatitis Group patch test results for the detection of delayed-type hypersensitivity to topical allergens. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;38:911-918.

- Rietschel RL, Fowler JF Jr. Fisher’s Contact Dermatitis. BC Decker; 2008.

- DeGroot AC. Patch Testing. acdegroot Publishing; 2008.

- Gralnek IM, Hays RD, Kilbourne A, et al. The impact of irritable bowel syndrome on health-related quality of life. Gastroenterology. 2000;119:654-660.

- Halder SL, Lock GR, Talley NJ, et al. Impact of functional gastrointestinal disorders on health-related quality of life: a population-based case–control study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;19:233-242.

- International Foundation for Gastrointestinal Disorders. About IBS. statistics. Accessed July 20, 2021. https://www.aboutibs.org/facts-about-ibs/statistics.html

- Rome Foundation. Guidelines—Rome III diagnostic criteria for functional gastrointestinal disorders. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2006;15:307-312.

- Collins SM. Is the irritable gut an inflamed gut? Scand J Gastroenterol. 1992;192(suppl):102-105.

- Park MI, Camilleri M. Is there a role of food allergy in irritable bowel syndrome and functional dyspepsia? a systemic review. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2006;18:595-607.

- Grover M, Herfarth H, Drossman DA. The functional-organic dichotomy: postinfectious irritable bowel syndrome and inflammatory bowel disease–irritable bowel syndrome. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7:48-53.

- Hrobiartsson A, Gotzsche PC. Is the placebo powerless? an analysis of clinical trials comparing placebo with no treatment. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:1594-1602.

- Spiller RC. Problems and challenges in the design of irritable bowel syndrome clinical trials: experience from published trials. Am J Med. 1999;107:91S-97S.

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is one of the most common disorders managed by primary care physicians and gastroenterologists.1 Characterized by abdominal pain coinciding with altered stool form and/or frequency as defined by the Rome IV diagnostic criteria,2 symptoms range from mild to debilitating and may remarkably impair quality of life and work productivity.1

The cause of IBS is poorly understood. Proposed pathophysiologic factors include impaired mucosal function, microbial imbalance, visceral hypersensitivity, psychologic dysfunction, genetic factors, neurotransmitter imbalance, postinfectious gastroenteritis, inflammation, and food intolerance, any or all of which may lead to the development and maintenance of IBS symptoms.3 More recent observations of inflammation in the intestinal lining4,5 and proinflammatory peripherally circulating cytokines6 challenge its traditional classification as a functional disorder.

The cause of this inflammation is of intense interest, with speculation that the bacterial microbiota, bile acids, association with postinfectious gastroenteritis and inflammatory bowel disease cases, and/or foods may contribute. Although approximately 50% of individuals with IBS report that foods aggravate their symptoms,7 studies investigating type I antibody–mediated immediate hypersensitivity have largely failed to demonstrate a substantial link, prompting many authorities to regard these associations as food “intolerances” rather than true allergies. Based on this body of literature, a large 2010 consensus report on all aspects of food allergies advises against food allergy testing for IBS.8

In contrast, by utilizing type IV food allergen skin patch testing, 2 proof-of-concept studies9,10 investigated a different allergic mechanism in IBS, namely cell-mediated delayed-type hypersensitivity. Because many foods and food additives are known to cause allergic contact dermatitis,11 it was hypothesized that these foods may elicit a similar delayed-type hypersensitivity response in the intestinal lining in previously sensitized individuals. By following a patch test–guided food avoidance diet, a large subpopulation of patients with IBS experienced partial or complete IBS symptom relief.9,10 Our study further investigates a role for food-related delayed-type hypersensitivities in the pathogenesis of IBS.

Methods

Patient Selection

This study was conducted in a secondary care community-based setting. All patients were self-referred over an 18-month period ending in October 2019, had physician-diagnosed IBS, and/or met the Rome IV criteria for IBS and presented expressly for the food patch testing on a fee-for-service basis. Subtype of IBS was determined on presentation by the self-reported historically predominant symptom. Duration of IBS symptoms was self-reported and was rounded to the nearest year for purposes of data collection.

Exclusion criteria included pregnancy, known allergy to adhesive tape or any of the food allergens used in the study, severe skin rash, symptoms that had a known cause other than IBS, or active treatment with systemic immunosuppressive medications.

Patch Testing

Skin patch testing was initiated using an extensive panel of 117 type IV food allergens (eTable)11 identified in the literature,12 most of which utilized standard compounded formulations13 or were available from reputable patch test manufacturers (Brial Allergen GmbH; Chemotechnique Diagnostics). This panel was not approved by the US Food and Drug Administration. The freeze-dried vegetable formulations were taken from the 2018 report.9 Standard skin patch test procedure protocols12 were used, affixing the patches to the upper aspect of the back.

Following patch test application on day 1, two follow-up visits occurred on day 3 and either day 4 or day 5. On day 3, patches were removed, and the initial results were read by a board-certified dermatologist according to a standard grading system.14 Interpretation of patch tests included no reaction, questionable reaction consisting of macular erythema, weak reaction consisting of erythema and slight edema, or strong reaction consisting of erythema and marked edema. On day 4 or day 5, the final patch test reading was performed, and patients were informed of their results. Patients were advised to avoid ingestion of all foods that elicited a questionable or positive patch test response for at least 3 months, and information about the foods and their avoidance also was distributed and reviewed.

Food Avoidance Questionnaire

Patients with questionable or positive patch tests at 72 or 96 hours were advised of their eligibility to participate in an institutional review board–approved food avoidance questionnaire study investigating the utility of patch test–guided food avoidance on IBS symptoms. The questionnaire assessed the following: (1) baseline average abdominal pain prior to patch test–guided avoidance diet (0=no symptoms; 10=very severe); (2) average abdominal pain since initiation of patch test–guided avoidance diet (0=no symptoms; 10=very severe); (3) degree of improvement in overall IBS symptoms by the end of the food avoidance period (0=no improvement; 10=great improvement); (4) compliance with the avoidance diet for the duration of the avoidance period (completely, partially, not at all, or not sure).

Questionnaires and informed consent were mailed to patients via the US Postal Service 3 months after completing the patch testing. The questionnaire and consent were to be completed and returned after dietary avoidance of the identified allergens for at least 3 months. Patients were not compensated for participation in the study.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis of data collected from study questionnaires was performed with Microsoft Excel. Mean abdominal pain and mean global improvement scores were reported along with 1 SD of the mean. For comparison of mean abdominal pain and improvement in global IBS symptoms from baseline to after 3 months of identified allergen avoidance, a Mann-Whitney U test was performed, with P<.05 being considered statistically significant.

Results

Thirty-seven consecutive patients underwent the testing and were eligible for the study. Nineteen patients were included in the study by virtue of completing and returning their posttest food avoidance questionnaire and informed consent. Eighteen patients were White and 1 was Asian. Subcategories of IBS were diarrhea predominant (9 [47.4%]), constipation predominant (3 [15.8%]), mixed type (5 [26.3%]), and undetermined type (2 [10.5%]). Questionnaire answers were reported after a mean (SD) duration of patch test–directed food avoidance of 4.5 (3.0) months (Table 1).

Overall Improvement

Fifteen (78.9%) patients reported at least slight to great improvement in their global IBS symptoms, and 4 (21.1%) reported no improvement (Table 2), with a mean (SD) improvement score of 5.1 (3.3)(P<.00001).

Abdominal Pain

All 19 patients reported mild to marked abdominal pain at baseline. The mean (SD) baseline pain score was 6.6 (1.9). The mean (SD) pain score was 3.4 (1.8)(P<.00001) after an average patch test–guided dietary avoidance of 4.5 (3.0) months (Table 3).

Comment

Despite intense research interest and a growing number of new medications for IBS approved by the US Food and Drug Administration, there remains a large void in the search for cost-effective and efficacious approaches for IBS evaluation and treatment. In addition to major disturbances in quality of life,14,15 the cost to society in direct medical expenses and indirect costs associated with loss of productivity and work absenteeism is considerable; estimates range from $21 billion or more annually.16

Food Hypersensitivities Triggering IBS

This study further evaluated a role for skin patch testing to identify delayed-type (type IV) food hypersensitivities that trigger IBS symptoms and differed from the prior investigations9,10 in that the symptoms used to define IBS were updated from the Rome III17 to the newer Rome IV2 criteria. The data presented here show moderate to great improvement in global IBS symptoms in 58% (11/19) of patients, which is in line with a 2018 report of 40 study participants for whom follow-up at 3 or more months was available,9 providing additional support for a role for type IV food allergies in causing the same gastrointestinal tract symptoms that define IBS. The distinction between food-related studies, including this one, that implicate food allergies9,10 and prior studies that did not support a role for food allergies in IBS pathogenesis8 can be accounted for by the type of allergy investigated. Conclusions that IBS flares after food ingestion were attributable to intolerance rather than true allergy were based on results investigating only the humoral arm and failed to consider the cell-mediated arm of the immune system. As such, foods that appear to trigger IBS symptoms on an allergic basis in our study are recognized in the literature12 as type IV allergens that elicit cell-mediated immunologic responses rather than more widely recognized type I allergens, such as peanuts and shellfish, that elicit immediate-type hypersensitivity responses. Although any type IV food allergen(s) could be responsible, a pattern emerged in this study and the study published in 2018.9 Namely, some foods stood out as more frequently inducing patch test reactions, with the 3 most common being carmine, cinnamon bark oil, and sodium bisulfite (eTable). The sample size is relatively small, but the results raise the question of whether these foods are the most likely to trigger IBS symptoms in the general population. If so, is it the result of a higher innate sensitizing potential and/or a higher frequency of exposure in commonly eaten foods? Larger randomized clinical trials are needed.

Immune Response and IBS

There is mounting evidence that the immune system may play a role in the pathophysiology of IBS.18 Both lymphocyte infiltration of the myenteric plexus and an increase in intestinal mucosal T lymphocytes have been observed, and it is generally accepted that the mucosal immune system seems to be activated, at least in a subset of patients with IBS.19 Irritable bowel syndrome associations with quiescent inflammatory bowel disease or postinfectious gastroenteritis provide 2 potential causes for the inflammation, but most IBS patients have had neither.20 The mucosal lining of the intestine and immune system have vast exposure to intraluminal allergens in transit, and it is hypothesized that the same delayed-type hypersensitivity response elicited in the skin by patch testing is elicited in the intestine, resulting in the inflammation that triggers IBS symptoms.10 The results here add to the growing body of evidence that ingestion of type IV food allergens by previously sensitized individuals could, in fact, be the primary source of the inflammation observed in a large subpopulation of individuals who carry a diagnosis of IBS.

Food Allergens in Patch Testing

Many of the food allergens used in this study are commonly found in various nonfood products that may contact the skin. For example, many flavorings are used as fragrances, and many preservatives, binders, thickeners, emulsifiers, and stabilizers serve the same role in moisturizers, cosmetics, and topical medications. Likewise, nickel sulfate hexahydrate, ubiquitous in foods that arise from the earth, often is found in metal in jewelry, clothing components, and cell phones. All are potential sensitizers. Thus, the question may arise whether the causal relationship between the food allergens identified by patch testing and IBS symptoms might be more of a systemic effect akin to systemic contact dermatitis as sometimes follows ingestion of an allergen to which an individual has been topically sensitized, rather than the proposed localized immunologic response in the intestinal lining. We were unaware of patient history of allergic contact dermatitis to any of the patch test allergens in this study, but the dermatologist author here (M.S.) has unpublished experience with 2 other patients with IBS who have benefited from low-nickel diets after having had positive patch tests to nickel sulfate hexahydrate and who, in retrospect, did report a history of earring dermatitis. Future investigations using pre– and post–food challenge histologic assessments of the intestinal mucosa in patients who benefit from patch test–guided food avoidance diets should help to better define the mechanism.

Because IBS has not been traditionally associated with structural or biochemical abnormalities detectable with current routine diagnostic tools, it has long been viewed as a functional disorder. The findings published more recently,9,10 in addition to this study’s results, would negate this functional classification in the subset of patients with IBS symptoms who experience sustained relief of their symptoms by patch test–directed food avoidance. The underlying delayed-type hypersensitivity pathogenesis of the IBS-like symptoms in these individuals would mandate an organic classification, aptly named allergic contact enteritis.10

Follow-up Data

The mean (SD) follow-up duration for this study and the 2018 report9 was 4.5 (3.0) months and 7.6 (3.9) months, respectively. The placebo effect is a concern for disorders such as IBS in which primarily subjective outcome measures are available,21 and in a retrospective analysis of 25 randomized, placebo-controlled IBS clinical trials, Spiller22 concluded the optimum length of such trials to be more than 3 months, which these studies exceed. Although not blinded or placebo controlled, the length of follow-up in the 2018 report9 and here enhances the validity of the results.

Limitation

The retrospective manner in which the self-assessments were reported in this study introduces the potential for recall bias, a variable that could affect results. The presence and direction of bias by any given individual cannot be known, making it difficult to determine any effect it may have had. Further investigation should include daily assessments and refine the primary study end points to include both abdominal pain and the defecation considerations that define IBS.

Conclusion

Food patch testing has the potential to offer a safe, cost-effective approach to the evaluation and management of IBS symptoms. Randomized clinical trials are needed to further investigate the validity of the proof-of-concept results to date. For patients who benefit from a patch test–guided avoidance diet, invasive and costly endoscopic, radiologic, and laboratory testing and pharmacologic management could be averted. Symptomatic relief could be attained simply by avoiding the implicated foods, essentially doing more by doing less.

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is one of the most common disorders managed by primary care physicians and gastroenterologists.1 Characterized by abdominal pain coinciding with altered stool form and/or frequency as defined by the Rome IV diagnostic criteria,2 symptoms range from mild to debilitating and may remarkably impair quality of life and work productivity.1

The cause of IBS is poorly understood. Proposed pathophysiologic factors include impaired mucosal function, microbial imbalance, visceral hypersensitivity, psychologic dysfunction, genetic factors, neurotransmitter imbalance, postinfectious gastroenteritis, inflammation, and food intolerance, any or all of which may lead to the development and maintenance of IBS symptoms.3 More recent observations of inflammation in the intestinal lining4,5 and proinflammatory peripherally circulating cytokines6 challenge its traditional classification as a functional disorder.

The cause of this inflammation is of intense interest, with speculation that the bacterial microbiota, bile acids, association with postinfectious gastroenteritis and inflammatory bowel disease cases, and/or foods may contribute. Although approximately 50% of individuals with IBS report that foods aggravate their symptoms,7 studies investigating type I antibody–mediated immediate hypersensitivity have largely failed to demonstrate a substantial link, prompting many authorities to regard these associations as food “intolerances” rather than true allergies. Based on this body of literature, a large 2010 consensus report on all aspects of food allergies advises against food allergy testing for IBS.8

In contrast, by utilizing type IV food allergen skin patch testing, 2 proof-of-concept studies9,10 investigated a different allergic mechanism in IBS, namely cell-mediated delayed-type hypersensitivity. Because many foods and food additives are known to cause allergic contact dermatitis,11 it was hypothesized that these foods may elicit a similar delayed-type hypersensitivity response in the intestinal lining in previously sensitized individuals. By following a patch test–guided food avoidance diet, a large subpopulation of patients with IBS experienced partial or complete IBS symptom relief.9,10 Our study further investigates a role for food-related delayed-type hypersensitivities in the pathogenesis of IBS.

Methods

Patient Selection

This study was conducted in a secondary care community-based setting. All patients were self-referred over an 18-month period ending in October 2019, had physician-diagnosed IBS, and/or met the Rome IV criteria for IBS and presented expressly for the food patch testing on a fee-for-service basis. Subtype of IBS was determined on presentation by the self-reported historically predominant symptom. Duration of IBS symptoms was self-reported and was rounded to the nearest year for purposes of data collection.

Exclusion criteria included pregnancy, known allergy to adhesive tape or any of the food allergens used in the study, severe skin rash, symptoms that had a known cause other than IBS, or active treatment with systemic immunosuppressive medications.

Patch Testing

Skin patch testing was initiated using an extensive panel of 117 type IV food allergens (eTable)11 identified in the literature,12 most of which utilized standard compounded formulations13 or were available from reputable patch test manufacturers (Brial Allergen GmbH; Chemotechnique Diagnostics). This panel was not approved by the US Food and Drug Administration. The freeze-dried vegetable formulations were taken from the 2018 report.9 Standard skin patch test procedure protocols12 were used, affixing the patches to the upper aspect of the back.

Following patch test application on day 1, two follow-up visits occurred on day 3 and either day 4 or day 5. On day 3, patches were removed, and the initial results were read by a board-certified dermatologist according to a standard grading system.14 Interpretation of patch tests included no reaction, questionable reaction consisting of macular erythema, weak reaction consisting of erythema and slight edema, or strong reaction consisting of erythema and marked edema. On day 4 or day 5, the final patch test reading was performed, and patients were informed of their results. Patients were advised to avoid ingestion of all foods that elicited a questionable or positive patch test response for at least 3 months, and information about the foods and their avoidance also was distributed and reviewed.

Food Avoidance Questionnaire

Patients with questionable or positive patch tests at 72 or 96 hours were advised of their eligibility to participate in an institutional review board–approved food avoidance questionnaire study investigating the utility of patch test–guided food avoidance on IBS symptoms. The questionnaire assessed the following: (1) baseline average abdominal pain prior to patch test–guided avoidance diet (0=no symptoms; 10=very severe); (2) average abdominal pain since initiation of patch test–guided avoidance diet (0=no symptoms; 10=very severe); (3) degree of improvement in overall IBS symptoms by the end of the food avoidance period (0=no improvement; 10=great improvement); (4) compliance with the avoidance diet for the duration of the avoidance period (completely, partially, not at all, or not sure).

Questionnaires and informed consent were mailed to patients via the US Postal Service 3 months after completing the patch testing. The questionnaire and consent were to be completed and returned after dietary avoidance of the identified allergens for at least 3 months. Patients were not compensated for participation in the study.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis of data collected from study questionnaires was performed with Microsoft Excel. Mean abdominal pain and mean global improvement scores were reported along with 1 SD of the mean. For comparison of mean abdominal pain and improvement in global IBS symptoms from baseline to after 3 months of identified allergen avoidance, a Mann-Whitney U test was performed, with P<.05 being considered statistically significant.

Results

Thirty-seven consecutive patients underwent the testing and were eligible for the study. Nineteen patients were included in the study by virtue of completing and returning their posttest food avoidance questionnaire and informed consent. Eighteen patients were White and 1 was Asian. Subcategories of IBS were diarrhea predominant (9 [47.4%]), constipation predominant (3 [15.8%]), mixed type (5 [26.3%]), and undetermined type (2 [10.5%]). Questionnaire answers were reported after a mean (SD) duration of patch test–directed food avoidance of 4.5 (3.0) months (Table 1).

Overall Improvement

Fifteen (78.9%) patients reported at least slight to great improvement in their global IBS symptoms, and 4 (21.1%) reported no improvement (Table 2), with a mean (SD) improvement score of 5.1 (3.3)(P<.00001).

Abdominal Pain

All 19 patients reported mild to marked abdominal pain at baseline. The mean (SD) baseline pain score was 6.6 (1.9). The mean (SD) pain score was 3.4 (1.8)(P<.00001) after an average patch test–guided dietary avoidance of 4.5 (3.0) months (Table 3).

Comment

Despite intense research interest and a growing number of new medications for IBS approved by the US Food and Drug Administration, there remains a large void in the search for cost-effective and efficacious approaches for IBS evaluation and treatment. In addition to major disturbances in quality of life,14,15 the cost to society in direct medical expenses and indirect costs associated with loss of productivity and work absenteeism is considerable; estimates range from $21 billion or more annually.16

Food Hypersensitivities Triggering IBS

This study further evaluated a role for skin patch testing to identify delayed-type (type IV) food hypersensitivities that trigger IBS symptoms and differed from the prior investigations9,10 in that the symptoms used to define IBS were updated from the Rome III17 to the newer Rome IV2 criteria. The data presented here show moderate to great improvement in global IBS symptoms in 58% (11/19) of patients, which is in line with a 2018 report of 40 study participants for whom follow-up at 3 or more months was available,9 providing additional support for a role for type IV food allergies in causing the same gastrointestinal tract symptoms that define IBS. The distinction between food-related studies, including this one, that implicate food allergies9,10 and prior studies that did not support a role for food allergies in IBS pathogenesis8 can be accounted for by the type of allergy investigated. Conclusions that IBS flares after food ingestion were attributable to intolerance rather than true allergy were based on results investigating only the humoral arm and failed to consider the cell-mediated arm of the immune system. As such, foods that appear to trigger IBS symptoms on an allergic basis in our study are recognized in the literature12 as type IV allergens that elicit cell-mediated immunologic responses rather than more widely recognized type I allergens, such as peanuts and shellfish, that elicit immediate-type hypersensitivity responses. Although any type IV food allergen(s) could be responsible, a pattern emerged in this study and the study published in 2018.9 Namely, some foods stood out as more frequently inducing patch test reactions, with the 3 most common being carmine, cinnamon bark oil, and sodium bisulfite (eTable). The sample size is relatively small, but the results raise the question of whether these foods are the most likely to trigger IBS symptoms in the general population. If so, is it the result of a higher innate sensitizing potential and/or a higher frequency of exposure in commonly eaten foods? Larger randomized clinical trials are needed.

Immune Response and IBS

There is mounting evidence that the immune system may play a role in the pathophysiology of IBS.18 Both lymphocyte infiltration of the myenteric plexus and an increase in intestinal mucosal T lymphocytes have been observed, and it is generally accepted that the mucosal immune system seems to be activated, at least in a subset of patients with IBS.19 Irritable bowel syndrome associations with quiescent inflammatory bowel disease or postinfectious gastroenteritis provide 2 potential causes for the inflammation, but most IBS patients have had neither.20 The mucosal lining of the intestine and immune system have vast exposure to intraluminal allergens in transit, and it is hypothesized that the same delayed-type hypersensitivity response elicited in the skin by patch testing is elicited in the intestine, resulting in the inflammation that triggers IBS symptoms.10 The results here add to the growing body of evidence that ingestion of type IV food allergens by previously sensitized individuals could, in fact, be the primary source of the inflammation observed in a large subpopulation of individuals who carry a diagnosis of IBS.

Food Allergens in Patch Testing

Many of the food allergens used in this study are commonly found in various nonfood products that may contact the skin. For example, many flavorings are used as fragrances, and many preservatives, binders, thickeners, emulsifiers, and stabilizers serve the same role in moisturizers, cosmetics, and topical medications. Likewise, nickel sulfate hexahydrate, ubiquitous in foods that arise from the earth, often is found in metal in jewelry, clothing components, and cell phones. All are potential sensitizers. Thus, the question may arise whether the causal relationship between the food allergens identified by patch testing and IBS symptoms might be more of a systemic effect akin to systemic contact dermatitis as sometimes follows ingestion of an allergen to which an individual has been topically sensitized, rather than the proposed localized immunologic response in the intestinal lining. We were unaware of patient history of allergic contact dermatitis to any of the patch test allergens in this study, but the dermatologist author here (M.S.) has unpublished experience with 2 other patients with IBS who have benefited from low-nickel diets after having had positive patch tests to nickel sulfate hexahydrate and who, in retrospect, did report a history of earring dermatitis. Future investigations using pre– and post–food challenge histologic assessments of the intestinal mucosa in patients who benefit from patch test–guided food avoidance diets should help to better define the mechanism.

Because IBS has not been traditionally associated with structural or biochemical abnormalities detectable with current routine diagnostic tools, it has long been viewed as a functional disorder. The findings published more recently,9,10 in addition to this study’s results, would negate this functional classification in the subset of patients with IBS symptoms who experience sustained relief of their symptoms by patch test–directed food avoidance. The underlying delayed-type hypersensitivity pathogenesis of the IBS-like symptoms in these individuals would mandate an organic classification, aptly named allergic contact enteritis.10

Follow-up Data

The mean (SD) follow-up duration for this study and the 2018 report9 was 4.5 (3.0) months and 7.6 (3.9) months, respectively. The placebo effect is a concern for disorders such as IBS in which primarily subjective outcome measures are available,21 and in a retrospective analysis of 25 randomized, placebo-controlled IBS clinical trials, Spiller22 concluded the optimum length of such trials to be more than 3 months, which these studies exceed. Although not blinded or placebo controlled, the length of follow-up in the 2018 report9 and here enhances the validity of the results.

Limitation

The retrospective manner in which the self-assessments were reported in this study introduces the potential for recall bias, a variable that could affect results. The presence and direction of bias by any given individual cannot be known, making it difficult to determine any effect it may have had. Further investigation should include daily assessments and refine the primary study end points to include both abdominal pain and the defecation considerations that define IBS.

Conclusion

Food patch testing has the potential to offer a safe, cost-effective approach to the evaluation and management of IBS symptoms. Randomized clinical trials are needed to further investigate the validity of the proof-of-concept results to date. For patients who benefit from a patch test–guided avoidance diet, invasive and costly endoscopic, radiologic, and laboratory testing and pharmacologic management could be averted. Symptomatic relief could be attained simply by avoiding the implicated foods, essentially doing more by doing less.

- Enck P, Aziz Q, Barbara G, et al. Irritable bowel syndrome. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2016;2:1-24.

- Lacy BE, Patel NK. Rome criteria and a diagnostic approach to irritable bowel syndrome. J Clin Med. 2017;6:99.

- Barbara G, De Giorgio R, Stanghellini V, et al. New pathophysiological mechanisms in irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;20(suppl 2):1-9

- Chadwick VS, Chen W, Shu D, et al. Activation of the mucosal immune system in irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology 2002;122:1778-1783.

- Tornblom H, Lindberg G, Nyberg B, et al. Full-thickness biopsy of the jejunum reveals inflammation and enteric neuropathy in irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2002;123:1972-1979.

- O’Mahony L, McCarthy J, Kelly

P, et al. Lactobacillus and bifidobacterium in irritable bowel syndrome: symptom responses and relationship to cytokine profiles. Gastroenterology. 2005;128:541-551. - Ragnarsson G, Bodemar G. Pain is temporally related to eating but not to defecation in the irritable bowel syndrome (IBS): patients’ description of diarrhea, constipation and symptom variation during a prospective 6-week study. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1998;10:415-421.

- Boyce JA, Assa’ad A, Burks AW, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of food allergy in the United States: report of the NAID-sponsored expert panel. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;126(6 suppl):S1-S58.

- Shin GH, Smith MS, Toro B, et al. Utility of food patch testing in the evaluation and management of irritable bowel syndrome. Skin. 2018;2:1-15.

- Stierstorfer MB, Sha CT. Food patch testing for irritable bowel syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:377-384.

- Marks JG, Belsito DV, DeLeo MD, et al. North American Contact Dermatitis Group patch test results for the detection of delayed-type hypersensitivity to topical allergens. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;38:911-918.

- Rietschel RL, Fowler JF Jr. Fisher’s Contact Dermatitis. BC Decker; 2008.

- DeGroot AC. Patch Testing. acdegroot Publishing; 2008.

- Gralnek IM, Hays RD, Kilbourne A, et al. The impact of irritable bowel syndrome on health-related quality of life. Gastroenterology. 2000;119:654-660.

- Halder SL, Lock GR, Talley NJ, et al. Impact of functional gastrointestinal disorders on health-related quality of life: a population-based case–control study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;19:233-242.

- International Foundation for Gastrointestinal Disorders. About IBS. statistics. Accessed July 20, 2021. https://www.aboutibs.org/facts-about-ibs/statistics.html

- Rome Foundation. Guidelines—Rome III diagnostic criteria for functional gastrointestinal disorders. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2006;15:307-312.

- Collins SM. Is the irritable gut an inflamed gut? Scand J Gastroenterol. 1992;192(suppl):102-105.

- Park MI, Camilleri M. Is there a role of food allergy in irritable bowel syndrome and functional dyspepsia? a systemic review. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2006;18:595-607.

- Grover M, Herfarth H, Drossman DA. The functional-organic dichotomy: postinfectious irritable bowel syndrome and inflammatory bowel disease–irritable bowel syndrome. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7:48-53.

- Hrobiartsson A, Gotzsche PC. Is the placebo powerless? an analysis of clinical trials comparing placebo with no treatment. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:1594-1602.

- Spiller RC. Problems and challenges in the design of irritable bowel syndrome clinical trials: experience from published trials. Am J Med. 1999;107:91S-97S.

- Enck P, Aziz Q, Barbara G, et al. Irritable bowel syndrome. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2016;2:1-24.

- Lacy BE, Patel NK. Rome criteria and a diagnostic approach to irritable bowel syndrome. J Clin Med. 2017;6:99.

- Barbara G, De Giorgio R, Stanghellini V, et al. New pathophysiological mechanisms in irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;20(suppl 2):1-9

- Chadwick VS, Chen W, Shu D, et al. Activation of the mucosal immune system in irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology 2002;122:1778-1783.

- Tornblom H, Lindberg G, Nyberg B, et al. Full-thickness biopsy of the jejunum reveals inflammation and enteric neuropathy in irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2002;123:1972-1979.

- O’Mahony L, McCarthy J, Kelly

P, et al. Lactobacillus and bifidobacterium in irritable bowel syndrome: symptom responses and relationship to cytokine profiles. Gastroenterology. 2005;128:541-551. - Ragnarsson G, Bodemar G. Pain is temporally related to eating but not to defecation in the irritable bowel syndrome (IBS): patients’ description of diarrhea, constipation and symptom variation during a prospective 6-week study. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1998;10:415-421.

- Boyce JA, Assa’ad A, Burks AW, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of food allergy in the United States: report of the NAID-sponsored expert panel. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;126(6 suppl):S1-S58.

- Shin GH, Smith MS, Toro B, et al. Utility of food patch testing in the evaluation and management of irritable bowel syndrome. Skin. 2018;2:1-15.

- Stierstorfer MB, Sha CT. Food patch testing for irritable bowel syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:377-384.

- Marks JG, Belsito DV, DeLeo MD, et al. North American Contact Dermatitis Group patch test results for the detection of delayed-type hypersensitivity to topical allergens. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;38:911-918.

- Rietschel RL, Fowler JF Jr. Fisher’s Contact Dermatitis. BC Decker; 2008.

- DeGroot AC. Patch Testing. acdegroot Publishing; 2008.

- Gralnek IM, Hays RD, Kilbourne A, et al. The impact of irritable bowel syndrome on health-related quality of life. Gastroenterology. 2000;119:654-660.

- Halder SL, Lock GR, Talley NJ, et al. Impact of functional gastrointestinal disorders on health-related quality of life: a population-based case–control study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;19:233-242.

- International Foundation for Gastrointestinal Disorders. About IBS. statistics. Accessed July 20, 2021. https://www.aboutibs.org/facts-about-ibs/statistics.html

- Rome Foundation. Guidelines—Rome III diagnostic criteria for functional gastrointestinal disorders. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2006;15:307-312.

- Collins SM. Is the irritable gut an inflamed gut? Scand J Gastroenterol. 1992;192(suppl):102-105.

- Park MI, Camilleri M. Is there a role of food allergy in irritable bowel syndrome and functional dyspepsia? a systemic review. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2006;18:595-607.

- Grover M, Herfarth H, Drossman DA. The functional-organic dichotomy: postinfectious irritable bowel syndrome and inflammatory bowel disease–irritable bowel syndrome. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7:48-53.

- Hrobiartsson A, Gotzsche PC. Is the placebo powerless? an analysis of clinical trials comparing placebo with no treatment. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:1594-1602.

- Spiller RC. Problems and challenges in the design of irritable bowel syndrome clinical trials: experience from published trials. Am J Med. 1999;107:91S-97S.

Practice Points

- Recent observations of inflammation in irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) challenge its traditional classification as a functional disorder.

- Delayed-type food hypersensitivities, as detectable by skin patch testing, to type IV food allergens are one plausible cause for intestinal inflammation.

- Patch test–directed food avoidance improves IBS symptoms in some patients and offers a new approach to the evaluation and management of this condition.

- Dermatologists and other health care practitioners with expertise in patch testing are uniquely positioned to utilize these skills to help patients with IBS.