User login

Assessment of Automated vs Conventional Blood Pressure Measurements in a Veterans Affairs Clinical Practice Setting

Assessment of Automated vs Conventional Blood Pressure Measurements in a Veterans Affairs Clinical Practice Setting

Hypertension remains one of the most important modifiable risk factors for the prevention of cardiovascular (CV) events. According to a population-based study, 25% of CV events (CV death, heart disease, coronary revascularization, stroke, or heart failure) are attributable to hypertension.1 Recent guidelines have emphasized the importance of accurate blood pressure (BP) measurement in facilitating appropriate hypertension diagnosis and management.2-4

Currently, there are different BP measurement methods endorsed by practice guidelines. These include conventional in-office measurement, 24-hour ambulatory BP monitoring (ABPM), home BP monitoring (HBPM), and automated office BP (AOBP) measurement.2-4 AOBP device protocols vary but generally involve devices automatically taking multiple BP measurements while the patient is unattended. These measurements are then presented as a single averaged reading, with individual BP values available for review by the clinician.

Researchers have found that AOBP measurements have a greater association with ABPM values and can mitigate the white coat effect observed in a substantial proportion of patients during in-clinic BP measurement.5 A meta-analysis found that the use of AOBP was associated with a 10.5 mm Hg reduction in systolic BP (SBP) compared with traditional office-based BP assessments.5 Similarly, a separate meta-analysis found that AOBP SBP measures were on average 14.5 mm Hg lower than routine office or research setting values.6 In addition, CV risk outcomes data support the use of AOBP to screen and manage patients with hypertension. The Cardiovascular Health Awareness Program (CHAP) study used AOBP values to determine the risk for CV events (myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, and stroke) in community-based patients aged ≥ 65 years.7 The study showed a significantly higher risk of CV events in patients with an SBP of 135 to 144 mm Hg and a diastolic BP (DBP) of 80 to 89 mm Hg. Therefore, the CHAP study researchers suggested an AOBP target of < 135/85 mm Hg to decrease the risk of CV events.7The landmark SPRINT trial, which was a major contributor to the development of BP target recommendations in guidelines, utilized AOBP to classify hypertension and guide management.2-4,8 SPRINT ultimately showed that intensive BP-lowering treatment (to SBP < 120 mm Hg) was associated with a 25% reduction in major CV events and a 27% reduction in all-cause mortality.8 Other evaluations found a close association between AOBP values and left ventricular mass index and carotid artery wall thickness as surrogate markers for end-organ damage.9,10 These data show AOBP as a reliable method to guide antihypertensive therapy interventions in the clinical setting.

Considering these proposed advantages, the 2017 Canadian guidelines for hypertension management recommend AOBP as the preferred method for clinic-based BP measurement, and the 2018 European Society of Cardiology/European Society of Hypertension blood pressure guidelines recommend the use of AOBP when feasible.3,4 The 2017 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Guideline for the Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Management of High Blood Pressure in Adults also discusses AOBP as a method to minimize potential confounders in BP values.2

This study evaluated the difference between AOBP and conventional in-office BP measurements obtained during cardiology clinic visits at the West Palm Beach Veterans Affairs Medical Center (WPBVAMC).

METHODS

A retrospective review of AOBP measurements was performed at the WPBVAMC cardiology clinic between May 26, 2017, and February 19, 2019. These AOBP measurements were taken at the discretion of a nurse or other clinician after initial, conventional BP measurements had been taken as part of clinic check-in procedures. No formal protocols dictated the use or timing of AOBP measurements. Similarly, the AOBP results were factored into clinical care decisions.

Clinicians at the cardiology clinic used AOBP averages that were derived using the BpTRU BPM-100 (BpTRU Medical Devices) meter, which averaged 5 BP readings taken at 1-minute intervals. Clinicians selected cuff size based on manufacturer recommendations. The testing was done with the patient seated alone in either a nursing triage area or a clinic office.

Data collected during the retrospective review included the clinician associated with the visit, the patient’s physical location and accompaniment status during AOBP measurement, conventionally measured BP and heart rates, and AOBP-derived BP and heart rate averages. Differences in BP values were compared with the paired t test, while binary comparisons were conducted through the McNemar test. Data collection and analysis were performed using Microsoft Excel.

During data collection, all information was stored in a secure drive accessible only to the investigators. The project was approved by the West Palm Beach Veterans Affairs Healthcare System Research and Development Committee as a nonresearch activity in accordance with Veterans Health Administration Handbook 1058.05; thus, institutional review board approval was not required.

RESULTS

Ninety-five nonconsecutive patients were included in the analysis. AOBP measurements were taken with the patient sitting alone in either a clinic office (n = 83) or nursing triage area (n = 12). Most patients were coming in for follow-up appointments; 13 patients (14%) had appointments related to a 24-hour ABPM session.

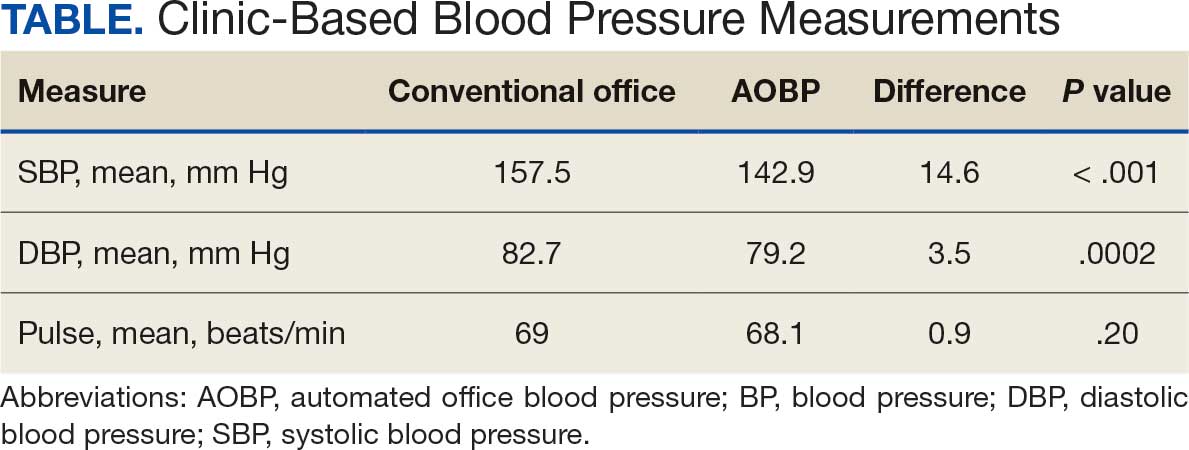

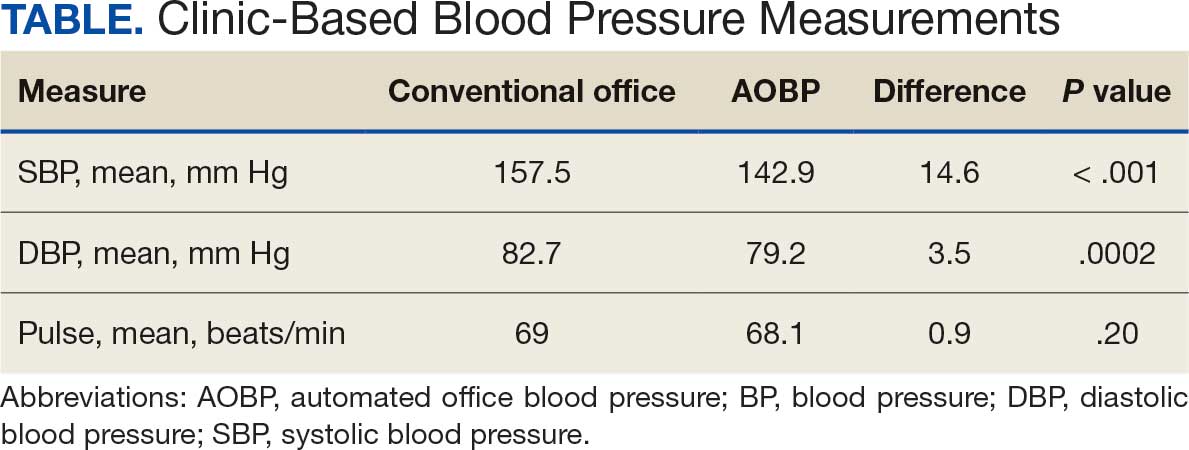

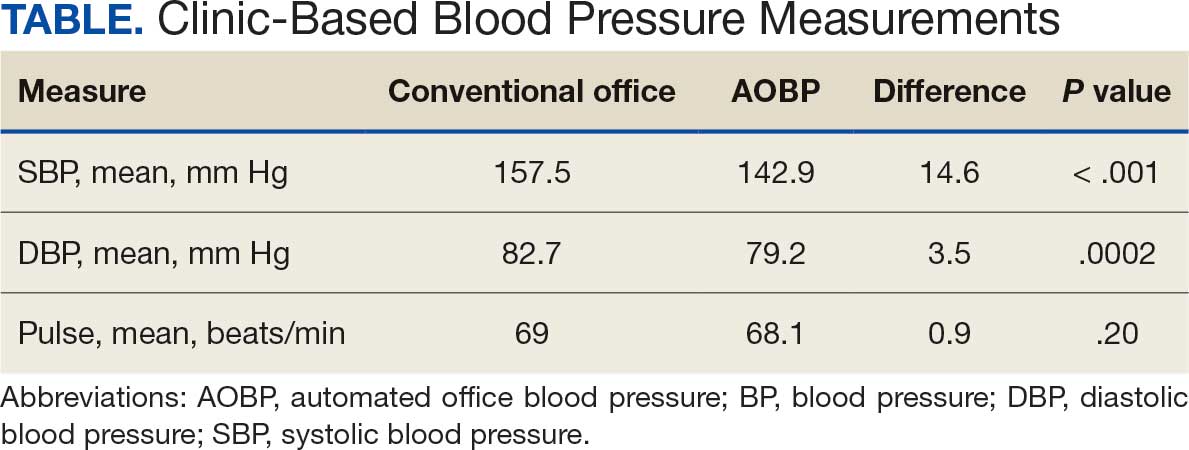

The mean SBP and DBP values were lower for the AOBP measurements vs the conventional BP measurements (mean SBP difference, 14.6 mm Hg; P < .001; mean DBP difference, 3.5 mm Hg; P = .0002) (Table). There were no appreciable differences in heart rates. The white coat effect was suggested based on an SBP reduction of > 20 mm Hg from conventional to AOBP measurements in 22 patients (23%), a DBP reduction of > 10 mm Hg in 21 patients (22%), and a reduction in both values in 8 patients (8%).

A controlled BP (< 130/80 mm Hg) was more common in the AOBP group than in the conventional group (22% vs 7%, respectively; P =.001).2 Review of conventional BP measurements indicated that 11 patients had systolic readings ≥ 180 mm Hg, 2 had diastolic readings ≥ 110 mm Hg, and 1 had a reading that was ≥ 180/110 mm Hg. AOBP measurements indicated that these 14 patients had SBP readings < 180 mm Hg and DBP readings < 110 mm Hg. The use of AOBP measurements may have mitigated unnecessary emergency room visits for these patients.

On review of clinic notes and actions associated with episodes of AOBP testing during routine follow-up clinic appointments, AOBP was determined to be useful with regard to clinical decision-making for 65 (79%) patients. Impacts of AOBP inclusion vs conventional BP assessments included clinician notation of AOBP, support for making changes that would have been considered based on conventional BP assessment. AOBP results gave support to forgoing a therapeutic intervention (ie, therapy addition or intensification) that may have been pursued based on conventional BP measurements in 25 of 82 patients (30%). These data suggest that AOBP readings can be useful and actionable by clinicians.

DISCUSSION

The findings of this study add to the growing evidence regarding AOBP use, application, and advantages in clinical practice. In this evaluation, the mean difference in SBP and DBP was 14.6 mm Hg and 3.5 mm Hg, respectively, from the conventional office measurements to the AOBP measurements. This difference is similar to that reported by the CAMBO trial and other evaluations, where the use of AOBP measurements corresponded to a reduction in SBP of between 10 and 20 mm Hg vs conventional measures.5,11-18

These findings showed a significantly higher percentage of controlled BP values (< 130/80 mm Hg) with AOBP values compared with conventional office measurements. The data supported the decision to defer antihypertensive therapy intervention in 30% of patients. Without AOBP data, patients may have been classified as uncontrolled, prompting therapy addition or intensification that could increase the risk of adverse events. Additionally, 14 patients would have met the criteria for hypertensive urgency under the guidelines at that time.2 With the use of AOBP readings, none of these patients were identified as having a hypertensive urgency, and they avoided an acute care referral or urgent intervention.

The discrepancy between AOBP and conventional office BP measurements suggested a white coat effect based on SBP and DBP readings in 22 (23%) and 21 (22%) patients, respectively. Practice guidelines recommend ABPM to mitigate a potential white coat effect.2-4 However, ABPM can be inconvenient for patients, as they need to travel to and from the clinic for fitting and removal (assuming that a facility has the device available for patient use). In addition, some patients may find it uncomfortable. Based on the correlation between AOBP and awake ABPM values, AOBP represents a feasible way to identify a white coat effect.

AOBP monitoring does not appear to be affected by the type of practice setting, as it has been evaluated in a variety of locations, including community-based pharmacies, primary care offices, and waiting rooms.12,19-22 However, potential AOBP implementation challenges may include office space constraints, clinician perception that it will delay workflow, and device cost. Costs associated with an AOBP meter vary widely based on device and procurement source, but have been estimated to range from $650 to > $2000.23 Published reports have described how to overcome AOBP implementation barriers.24,25

Limitations

The results of this evaluation should be interpreted cautiously due to several limitations. First, the retrospective study was conducted at a single clinic that may not be representative of other Veterans Health Administration or community-based populations. In addition, patient data such as age, sex, and body mass index were not available. AOBP measurements were obtained at the discretion of the clinician and not according to a prespecified protocol.

Conclusions

This analysis showed AOBP measurement leads to a greater percentage of controlled BP values compared with conventional office BP measurement, positioning it as a way to reduce BP misclassification, prevent potentially unnecessary therapeutic interventions, and mitigate the white coat effect.

- Cheng S, Claggett B, Correia AW, et al. Temporal Trends in the Population Attributable Risk for Cardiovascular Disease: The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study. Circulation. 2014;130:820-828. doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.008506

- Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA guideline for the prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of high blood pressure in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Hypertension. 2018;71(6):1269-1324. doi:10.1161/HYP.0000000000000066

- Leung AA, Daskalopoulou SS, Dasgupta K, et al. Hypertension Canada’s 2017 guidelines for diagnosis, risk assessment, prevention, and treatment of hypertension in adults. Can J Cardiol. 2017;33(5):557-576. doi:10.1016/j.cjca.2017.03.005

- Williams B, Mancia G, Spiering W, et al. 2018 ESC/ESH guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension. Eur Heart J. 2018;39(33):3021-3104. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehy339

- Pappaccogli M, Di Monaco S, Perlo E, et al. Comparison of automated office blood pressure with office and out-off-office measurement techniques. Hypertension. 2019;73(2):481-490. doi:10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.118.12079

- Roerecke M, Kaczorowski J, Myers MG. Comparing automated office blood pressure readings with other methods of blood pressure measurement for identifying patients with possible hypertension - a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179:351-362. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.6551

- Kaczorowski J, Chambers LW, Karwalajtys T, et al. Cardiovascular Health Awareness Program (CHAP): a community cluster-randomised trial among elderly Canadians. Prev Med. 2008;46(6):537-544. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2008.02.005

- SPRINT Research Group. A randomized trial of intensive versus standard blood-pressure control. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(22):2103-2116. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1511939

- Andreadis EA, Agaliotis GD, Angelopoulos ET, et al. Automated office blood pressure and 24-h ambulatory measurements are equally associated with left ventricular mass index. Am J Hypertens. 2011;24(6):661-666. doi:10.1038/ajh.2011.38

- Campbell NRC, McKay DW, Conradson H, et al. Automated oscillometric blood pressure versus auscultatory blood pressure as a predictor of carotid intima-medial thickness in male firefighters. J Hum Hypertens. 2007;21(7):588-590. doi:10.1038/sj.jhh.1002190

- Myers MG, Godwin M, Dawes M et al. Conventional versus automated measurement of blood pressure in primary care patients with systolic hypertension: randomised parallel design controlled trial. BMJ. 2011;342:d286. doi:10.1136/bmj.d286

- Beckett L, Godwin M. The BpTRU automatic blood pressure monitor compared to 24 hour ambulatory blood pressure monitoring in the assessment of blood pressure in patients with hypertension. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2005;5(1):18. doi:10.1186/1471-2261-5-18

- Myers MG, Valdivieso M, Kiss A. Use of automated office blood pressure measurement to reduce the white coat response. J Hypertens. 2009;27(2):280-286. doi:10.1097/HJH.0b013e32831b9e6b

- Myers MG, Valdivieso M, Kiss A. Consistent relationship between automated office blood pressure recorded in different settings. Blood Press Monit. 2009;14(3):108-111. doi:10.1097/MBP.0b013e32832c5167

- Myers MG, Valdivieso M, Kiss A. Optimum frequency of office blood pressure measurement using an automated sphygmomanometer. Blood Press Monit. 2008;13(6):333-338. doi:10.1097/MBP.0b013e3283104247

- Myers MG. A proposed algorithm for diagnosing hypertension using automated office blood pressure measurement. J Hypertens. 2010;28(4):703-708. doi:10.1097/HJH.0b013e328335d091

- Godwin M, Birtwhistle R, Delva D, et al. Manual and automated office measurements in relation to awake ambulatory blood pressure monitoring. Fam Pract. 2011;28(1):110-117. doi:10.1093/fampra/cmq067

- Myers MG, Valdivieso M, Chessman M, Kiss A. Can sphygmomanometers designed for self-measurement of blood pressure in the home be used in office practice? Blood Press Monit. 2010;15(6):300-304. doi:10.1097/MBP.0b013e328340d128

- Leung AA, Nerenberg K, Daskalopoulou SS, et al. Hypertension Canada’s 2016 Canadian hypertension education program guidelines for blood pressure measurement, diagnosis, assessment of risk, prevention, and treatment of hypertension. Can J Cardiol. 2016;32(5):569-588. doi:10.1016/j.cjca.2016.02.066

- Myers MG. A short history of automated office blood pressure - 15 years to SPRINT. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2016;18(8):721-724. doi:10.1111/jch.12820

- Myers MG, Kaczorowski J, Dawes M, Godwin M. Automated office blood pressure measurement in primary care. Can Fam Physician. 2014;60(2):127-132.

- Armstrong D, Matangi M, Brouillard D, Myers MG. Automated office blood pressure - being alone and not location is what matters most. Blood Press Monit. 2015;20(4):204-208. doi:10.1097/MBP.0000000000000133

- Yarows SA. What is the Cost of Measuring a Blood Pressure? Ann Clin Hypertens. 2018;2:59-66. doi:10.29328/journal.ach.1001012

- Cabana MD, Rand CS, Powe NR, et al. Why don’t physicians follow clinical practice guidelines? A framework for improvement. JAMA. 1999;282(15):1458-1465. doi:10.1001/jama.282.15.1458

- Doane J, Buu J, Penrod MJ, et al. Measuring and managing blood pressure in a primary care setting: a pragmatic implementation study. J Am Board Fam Med. 2018;31(3):375-388. doi:10.3122/jabfm.2018.03.170450

Hypertension remains one of the most important modifiable risk factors for the prevention of cardiovascular (CV) events. According to a population-based study, 25% of CV events (CV death, heart disease, coronary revascularization, stroke, or heart failure) are attributable to hypertension.1 Recent guidelines have emphasized the importance of accurate blood pressure (BP) measurement in facilitating appropriate hypertension diagnosis and management.2-4

Currently, there are different BP measurement methods endorsed by practice guidelines. These include conventional in-office measurement, 24-hour ambulatory BP monitoring (ABPM), home BP monitoring (HBPM), and automated office BP (AOBP) measurement.2-4 AOBP device protocols vary but generally involve devices automatically taking multiple BP measurements while the patient is unattended. These measurements are then presented as a single averaged reading, with individual BP values available for review by the clinician.

Researchers have found that AOBP measurements have a greater association with ABPM values and can mitigate the white coat effect observed in a substantial proportion of patients during in-clinic BP measurement.5 A meta-analysis found that the use of AOBP was associated with a 10.5 mm Hg reduction in systolic BP (SBP) compared with traditional office-based BP assessments.5 Similarly, a separate meta-analysis found that AOBP SBP measures were on average 14.5 mm Hg lower than routine office or research setting values.6 In addition, CV risk outcomes data support the use of AOBP to screen and manage patients with hypertension. The Cardiovascular Health Awareness Program (CHAP) study used AOBP values to determine the risk for CV events (myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, and stroke) in community-based patients aged ≥ 65 years.7 The study showed a significantly higher risk of CV events in patients with an SBP of 135 to 144 mm Hg and a diastolic BP (DBP) of 80 to 89 mm Hg. Therefore, the CHAP study researchers suggested an AOBP target of < 135/85 mm Hg to decrease the risk of CV events.7The landmark SPRINT trial, which was a major contributor to the development of BP target recommendations in guidelines, utilized AOBP to classify hypertension and guide management.2-4,8 SPRINT ultimately showed that intensive BP-lowering treatment (to SBP < 120 mm Hg) was associated with a 25% reduction in major CV events and a 27% reduction in all-cause mortality.8 Other evaluations found a close association between AOBP values and left ventricular mass index and carotid artery wall thickness as surrogate markers for end-organ damage.9,10 These data show AOBP as a reliable method to guide antihypertensive therapy interventions in the clinical setting.

Considering these proposed advantages, the 2017 Canadian guidelines for hypertension management recommend AOBP as the preferred method for clinic-based BP measurement, and the 2018 European Society of Cardiology/European Society of Hypertension blood pressure guidelines recommend the use of AOBP when feasible.3,4 The 2017 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Guideline for the Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Management of High Blood Pressure in Adults also discusses AOBP as a method to minimize potential confounders in BP values.2

This study evaluated the difference between AOBP and conventional in-office BP measurements obtained during cardiology clinic visits at the West Palm Beach Veterans Affairs Medical Center (WPBVAMC).

METHODS

A retrospective review of AOBP measurements was performed at the WPBVAMC cardiology clinic between May 26, 2017, and February 19, 2019. These AOBP measurements were taken at the discretion of a nurse or other clinician after initial, conventional BP measurements had been taken as part of clinic check-in procedures. No formal protocols dictated the use or timing of AOBP measurements. Similarly, the AOBP results were factored into clinical care decisions.

Clinicians at the cardiology clinic used AOBP averages that were derived using the BpTRU BPM-100 (BpTRU Medical Devices) meter, which averaged 5 BP readings taken at 1-minute intervals. Clinicians selected cuff size based on manufacturer recommendations. The testing was done with the patient seated alone in either a nursing triage area or a clinic office.

Data collected during the retrospective review included the clinician associated with the visit, the patient’s physical location and accompaniment status during AOBP measurement, conventionally measured BP and heart rates, and AOBP-derived BP and heart rate averages. Differences in BP values were compared with the paired t test, while binary comparisons were conducted through the McNemar test. Data collection and analysis were performed using Microsoft Excel.

During data collection, all information was stored in a secure drive accessible only to the investigators. The project was approved by the West Palm Beach Veterans Affairs Healthcare System Research and Development Committee as a nonresearch activity in accordance with Veterans Health Administration Handbook 1058.05; thus, institutional review board approval was not required.

RESULTS

Ninety-five nonconsecutive patients were included in the analysis. AOBP measurements were taken with the patient sitting alone in either a clinic office (n = 83) or nursing triage area (n = 12). Most patients were coming in for follow-up appointments; 13 patients (14%) had appointments related to a 24-hour ABPM session.

The mean SBP and DBP values were lower for the AOBP measurements vs the conventional BP measurements (mean SBP difference, 14.6 mm Hg; P < .001; mean DBP difference, 3.5 mm Hg; P = .0002) (Table). There were no appreciable differences in heart rates. The white coat effect was suggested based on an SBP reduction of > 20 mm Hg from conventional to AOBP measurements in 22 patients (23%), a DBP reduction of > 10 mm Hg in 21 patients (22%), and a reduction in both values in 8 patients (8%).

A controlled BP (< 130/80 mm Hg) was more common in the AOBP group than in the conventional group (22% vs 7%, respectively; P =.001).2 Review of conventional BP measurements indicated that 11 patients had systolic readings ≥ 180 mm Hg, 2 had diastolic readings ≥ 110 mm Hg, and 1 had a reading that was ≥ 180/110 mm Hg. AOBP measurements indicated that these 14 patients had SBP readings < 180 mm Hg and DBP readings < 110 mm Hg. The use of AOBP measurements may have mitigated unnecessary emergency room visits for these patients.

On review of clinic notes and actions associated with episodes of AOBP testing during routine follow-up clinic appointments, AOBP was determined to be useful with regard to clinical decision-making for 65 (79%) patients. Impacts of AOBP inclusion vs conventional BP assessments included clinician notation of AOBP, support for making changes that would have been considered based on conventional BP assessment. AOBP results gave support to forgoing a therapeutic intervention (ie, therapy addition or intensification) that may have been pursued based on conventional BP measurements in 25 of 82 patients (30%). These data suggest that AOBP readings can be useful and actionable by clinicians.

DISCUSSION

The findings of this study add to the growing evidence regarding AOBP use, application, and advantages in clinical practice. In this evaluation, the mean difference in SBP and DBP was 14.6 mm Hg and 3.5 mm Hg, respectively, from the conventional office measurements to the AOBP measurements. This difference is similar to that reported by the CAMBO trial and other evaluations, where the use of AOBP measurements corresponded to a reduction in SBP of between 10 and 20 mm Hg vs conventional measures.5,11-18

These findings showed a significantly higher percentage of controlled BP values (< 130/80 mm Hg) with AOBP values compared with conventional office measurements. The data supported the decision to defer antihypertensive therapy intervention in 30% of patients. Without AOBP data, patients may have been classified as uncontrolled, prompting therapy addition or intensification that could increase the risk of adverse events. Additionally, 14 patients would have met the criteria for hypertensive urgency under the guidelines at that time.2 With the use of AOBP readings, none of these patients were identified as having a hypertensive urgency, and they avoided an acute care referral or urgent intervention.

The discrepancy between AOBP and conventional office BP measurements suggested a white coat effect based on SBP and DBP readings in 22 (23%) and 21 (22%) patients, respectively. Practice guidelines recommend ABPM to mitigate a potential white coat effect.2-4 However, ABPM can be inconvenient for patients, as they need to travel to and from the clinic for fitting and removal (assuming that a facility has the device available for patient use). In addition, some patients may find it uncomfortable. Based on the correlation between AOBP and awake ABPM values, AOBP represents a feasible way to identify a white coat effect.

AOBP monitoring does not appear to be affected by the type of practice setting, as it has been evaluated in a variety of locations, including community-based pharmacies, primary care offices, and waiting rooms.12,19-22 However, potential AOBP implementation challenges may include office space constraints, clinician perception that it will delay workflow, and device cost. Costs associated with an AOBP meter vary widely based on device and procurement source, but have been estimated to range from $650 to > $2000.23 Published reports have described how to overcome AOBP implementation barriers.24,25

Limitations

The results of this evaluation should be interpreted cautiously due to several limitations. First, the retrospective study was conducted at a single clinic that may not be representative of other Veterans Health Administration or community-based populations. In addition, patient data such as age, sex, and body mass index were not available. AOBP measurements were obtained at the discretion of the clinician and not according to a prespecified protocol.

Conclusions

This analysis showed AOBP measurement leads to a greater percentage of controlled BP values compared with conventional office BP measurement, positioning it as a way to reduce BP misclassification, prevent potentially unnecessary therapeutic interventions, and mitigate the white coat effect.

Hypertension remains one of the most important modifiable risk factors for the prevention of cardiovascular (CV) events. According to a population-based study, 25% of CV events (CV death, heart disease, coronary revascularization, stroke, or heart failure) are attributable to hypertension.1 Recent guidelines have emphasized the importance of accurate blood pressure (BP) measurement in facilitating appropriate hypertension diagnosis and management.2-4

Currently, there are different BP measurement methods endorsed by practice guidelines. These include conventional in-office measurement, 24-hour ambulatory BP monitoring (ABPM), home BP monitoring (HBPM), and automated office BP (AOBP) measurement.2-4 AOBP device protocols vary but generally involve devices automatically taking multiple BP measurements while the patient is unattended. These measurements are then presented as a single averaged reading, with individual BP values available for review by the clinician.

Researchers have found that AOBP measurements have a greater association with ABPM values and can mitigate the white coat effect observed in a substantial proportion of patients during in-clinic BP measurement.5 A meta-analysis found that the use of AOBP was associated with a 10.5 mm Hg reduction in systolic BP (SBP) compared with traditional office-based BP assessments.5 Similarly, a separate meta-analysis found that AOBP SBP measures were on average 14.5 mm Hg lower than routine office or research setting values.6 In addition, CV risk outcomes data support the use of AOBP to screen and manage patients with hypertension. The Cardiovascular Health Awareness Program (CHAP) study used AOBP values to determine the risk for CV events (myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, and stroke) in community-based patients aged ≥ 65 years.7 The study showed a significantly higher risk of CV events in patients with an SBP of 135 to 144 mm Hg and a diastolic BP (DBP) of 80 to 89 mm Hg. Therefore, the CHAP study researchers suggested an AOBP target of < 135/85 mm Hg to decrease the risk of CV events.7The landmark SPRINT trial, which was a major contributor to the development of BP target recommendations in guidelines, utilized AOBP to classify hypertension and guide management.2-4,8 SPRINT ultimately showed that intensive BP-lowering treatment (to SBP < 120 mm Hg) was associated with a 25% reduction in major CV events and a 27% reduction in all-cause mortality.8 Other evaluations found a close association between AOBP values and left ventricular mass index and carotid artery wall thickness as surrogate markers for end-organ damage.9,10 These data show AOBP as a reliable method to guide antihypertensive therapy interventions in the clinical setting.

Considering these proposed advantages, the 2017 Canadian guidelines for hypertension management recommend AOBP as the preferred method for clinic-based BP measurement, and the 2018 European Society of Cardiology/European Society of Hypertension blood pressure guidelines recommend the use of AOBP when feasible.3,4 The 2017 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Guideline for the Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Management of High Blood Pressure in Adults also discusses AOBP as a method to minimize potential confounders in BP values.2

This study evaluated the difference between AOBP and conventional in-office BP measurements obtained during cardiology clinic visits at the West Palm Beach Veterans Affairs Medical Center (WPBVAMC).

METHODS

A retrospective review of AOBP measurements was performed at the WPBVAMC cardiology clinic between May 26, 2017, and February 19, 2019. These AOBP measurements were taken at the discretion of a nurse or other clinician after initial, conventional BP measurements had been taken as part of clinic check-in procedures. No formal protocols dictated the use or timing of AOBP measurements. Similarly, the AOBP results were factored into clinical care decisions.

Clinicians at the cardiology clinic used AOBP averages that were derived using the BpTRU BPM-100 (BpTRU Medical Devices) meter, which averaged 5 BP readings taken at 1-minute intervals. Clinicians selected cuff size based on manufacturer recommendations. The testing was done with the patient seated alone in either a nursing triage area or a clinic office.

Data collected during the retrospective review included the clinician associated with the visit, the patient’s physical location and accompaniment status during AOBP measurement, conventionally measured BP and heart rates, and AOBP-derived BP and heart rate averages. Differences in BP values were compared with the paired t test, while binary comparisons were conducted through the McNemar test. Data collection and analysis were performed using Microsoft Excel.

During data collection, all information was stored in a secure drive accessible only to the investigators. The project was approved by the West Palm Beach Veterans Affairs Healthcare System Research and Development Committee as a nonresearch activity in accordance with Veterans Health Administration Handbook 1058.05; thus, institutional review board approval was not required.

RESULTS

Ninety-five nonconsecutive patients were included in the analysis. AOBP measurements were taken with the patient sitting alone in either a clinic office (n = 83) or nursing triage area (n = 12). Most patients were coming in for follow-up appointments; 13 patients (14%) had appointments related to a 24-hour ABPM session.

The mean SBP and DBP values were lower for the AOBP measurements vs the conventional BP measurements (mean SBP difference, 14.6 mm Hg; P < .001; mean DBP difference, 3.5 mm Hg; P = .0002) (Table). There were no appreciable differences in heart rates. The white coat effect was suggested based on an SBP reduction of > 20 mm Hg from conventional to AOBP measurements in 22 patients (23%), a DBP reduction of > 10 mm Hg in 21 patients (22%), and a reduction in both values in 8 patients (8%).

A controlled BP (< 130/80 mm Hg) was more common in the AOBP group than in the conventional group (22% vs 7%, respectively; P =.001).2 Review of conventional BP measurements indicated that 11 patients had systolic readings ≥ 180 mm Hg, 2 had diastolic readings ≥ 110 mm Hg, and 1 had a reading that was ≥ 180/110 mm Hg. AOBP measurements indicated that these 14 patients had SBP readings < 180 mm Hg and DBP readings < 110 mm Hg. The use of AOBP measurements may have mitigated unnecessary emergency room visits for these patients.

On review of clinic notes and actions associated with episodes of AOBP testing during routine follow-up clinic appointments, AOBP was determined to be useful with regard to clinical decision-making for 65 (79%) patients. Impacts of AOBP inclusion vs conventional BP assessments included clinician notation of AOBP, support for making changes that would have been considered based on conventional BP assessment. AOBP results gave support to forgoing a therapeutic intervention (ie, therapy addition or intensification) that may have been pursued based on conventional BP measurements in 25 of 82 patients (30%). These data suggest that AOBP readings can be useful and actionable by clinicians.

DISCUSSION

The findings of this study add to the growing evidence regarding AOBP use, application, and advantages in clinical practice. In this evaluation, the mean difference in SBP and DBP was 14.6 mm Hg and 3.5 mm Hg, respectively, from the conventional office measurements to the AOBP measurements. This difference is similar to that reported by the CAMBO trial and other evaluations, where the use of AOBP measurements corresponded to a reduction in SBP of between 10 and 20 mm Hg vs conventional measures.5,11-18

These findings showed a significantly higher percentage of controlled BP values (< 130/80 mm Hg) with AOBP values compared with conventional office measurements. The data supported the decision to defer antihypertensive therapy intervention in 30% of patients. Without AOBP data, patients may have been classified as uncontrolled, prompting therapy addition or intensification that could increase the risk of adverse events. Additionally, 14 patients would have met the criteria for hypertensive urgency under the guidelines at that time.2 With the use of AOBP readings, none of these patients were identified as having a hypertensive urgency, and they avoided an acute care referral or urgent intervention.

The discrepancy between AOBP and conventional office BP measurements suggested a white coat effect based on SBP and DBP readings in 22 (23%) and 21 (22%) patients, respectively. Practice guidelines recommend ABPM to mitigate a potential white coat effect.2-4 However, ABPM can be inconvenient for patients, as they need to travel to and from the clinic for fitting and removal (assuming that a facility has the device available for patient use). In addition, some patients may find it uncomfortable. Based on the correlation between AOBP and awake ABPM values, AOBP represents a feasible way to identify a white coat effect.

AOBP monitoring does not appear to be affected by the type of practice setting, as it has been evaluated in a variety of locations, including community-based pharmacies, primary care offices, and waiting rooms.12,19-22 However, potential AOBP implementation challenges may include office space constraints, clinician perception that it will delay workflow, and device cost. Costs associated with an AOBP meter vary widely based on device and procurement source, but have been estimated to range from $650 to > $2000.23 Published reports have described how to overcome AOBP implementation barriers.24,25

Limitations

The results of this evaluation should be interpreted cautiously due to several limitations. First, the retrospective study was conducted at a single clinic that may not be representative of other Veterans Health Administration or community-based populations. In addition, patient data such as age, sex, and body mass index were not available. AOBP measurements were obtained at the discretion of the clinician and not according to a prespecified protocol.

Conclusions

This analysis showed AOBP measurement leads to a greater percentage of controlled BP values compared with conventional office BP measurement, positioning it as a way to reduce BP misclassification, prevent potentially unnecessary therapeutic interventions, and mitigate the white coat effect.

- Cheng S, Claggett B, Correia AW, et al. Temporal Trends in the Population Attributable Risk for Cardiovascular Disease: The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study. Circulation. 2014;130:820-828. doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.008506

- Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA guideline for the prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of high blood pressure in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Hypertension. 2018;71(6):1269-1324. doi:10.1161/HYP.0000000000000066

- Leung AA, Daskalopoulou SS, Dasgupta K, et al. Hypertension Canada’s 2017 guidelines for diagnosis, risk assessment, prevention, and treatment of hypertension in adults. Can J Cardiol. 2017;33(5):557-576. doi:10.1016/j.cjca.2017.03.005

- Williams B, Mancia G, Spiering W, et al. 2018 ESC/ESH guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension. Eur Heart J. 2018;39(33):3021-3104. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehy339

- Pappaccogli M, Di Monaco S, Perlo E, et al. Comparison of automated office blood pressure with office and out-off-office measurement techniques. Hypertension. 2019;73(2):481-490. doi:10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.118.12079

- Roerecke M, Kaczorowski J, Myers MG. Comparing automated office blood pressure readings with other methods of blood pressure measurement for identifying patients with possible hypertension - a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179:351-362. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.6551

- Kaczorowski J, Chambers LW, Karwalajtys T, et al. Cardiovascular Health Awareness Program (CHAP): a community cluster-randomised trial among elderly Canadians. Prev Med. 2008;46(6):537-544. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2008.02.005

- SPRINT Research Group. A randomized trial of intensive versus standard blood-pressure control. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(22):2103-2116. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1511939

- Andreadis EA, Agaliotis GD, Angelopoulos ET, et al. Automated office blood pressure and 24-h ambulatory measurements are equally associated with left ventricular mass index. Am J Hypertens. 2011;24(6):661-666. doi:10.1038/ajh.2011.38

- Campbell NRC, McKay DW, Conradson H, et al. Automated oscillometric blood pressure versus auscultatory blood pressure as a predictor of carotid intima-medial thickness in male firefighters. J Hum Hypertens. 2007;21(7):588-590. doi:10.1038/sj.jhh.1002190

- Myers MG, Godwin M, Dawes M et al. Conventional versus automated measurement of blood pressure in primary care patients with systolic hypertension: randomised parallel design controlled trial. BMJ. 2011;342:d286. doi:10.1136/bmj.d286

- Beckett L, Godwin M. The BpTRU automatic blood pressure monitor compared to 24 hour ambulatory blood pressure monitoring in the assessment of blood pressure in patients with hypertension. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2005;5(1):18. doi:10.1186/1471-2261-5-18

- Myers MG, Valdivieso M, Kiss A. Use of automated office blood pressure measurement to reduce the white coat response. J Hypertens. 2009;27(2):280-286. doi:10.1097/HJH.0b013e32831b9e6b

- Myers MG, Valdivieso M, Kiss A. Consistent relationship between automated office blood pressure recorded in different settings. Blood Press Monit. 2009;14(3):108-111. doi:10.1097/MBP.0b013e32832c5167

- Myers MG, Valdivieso M, Kiss A. Optimum frequency of office blood pressure measurement using an automated sphygmomanometer. Blood Press Monit. 2008;13(6):333-338. doi:10.1097/MBP.0b013e3283104247

- Myers MG. A proposed algorithm for diagnosing hypertension using automated office blood pressure measurement. J Hypertens. 2010;28(4):703-708. doi:10.1097/HJH.0b013e328335d091

- Godwin M, Birtwhistle R, Delva D, et al. Manual and automated office measurements in relation to awake ambulatory blood pressure monitoring. Fam Pract. 2011;28(1):110-117. doi:10.1093/fampra/cmq067

- Myers MG, Valdivieso M, Chessman M, Kiss A. Can sphygmomanometers designed for self-measurement of blood pressure in the home be used in office practice? Blood Press Monit. 2010;15(6):300-304. doi:10.1097/MBP.0b013e328340d128

- Leung AA, Nerenberg K, Daskalopoulou SS, et al. Hypertension Canada’s 2016 Canadian hypertension education program guidelines for blood pressure measurement, diagnosis, assessment of risk, prevention, and treatment of hypertension. Can J Cardiol. 2016;32(5):569-588. doi:10.1016/j.cjca.2016.02.066

- Myers MG. A short history of automated office blood pressure - 15 years to SPRINT. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2016;18(8):721-724. doi:10.1111/jch.12820

- Myers MG, Kaczorowski J, Dawes M, Godwin M. Automated office blood pressure measurement in primary care. Can Fam Physician. 2014;60(2):127-132.

- Armstrong D, Matangi M, Brouillard D, Myers MG. Automated office blood pressure - being alone and not location is what matters most. Blood Press Monit. 2015;20(4):204-208. doi:10.1097/MBP.0000000000000133

- Yarows SA. What is the Cost of Measuring a Blood Pressure? Ann Clin Hypertens. 2018;2:59-66. doi:10.29328/journal.ach.1001012

- Cabana MD, Rand CS, Powe NR, et al. Why don’t physicians follow clinical practice guidelines? A framework for improvement. JAMA. 1999;282(15):1458-1465. doi:10.1001/jama.282.15.1458

- Doane J, Buu J, Penrod MJ, et al. Measuring and managing blood pressure in a primary care setting: a pragmatic implementation study. J Am Board Fam Med. 2018;31(3):375-388. doi:10.3122/jabfm.2018.03.170450

- Cheng S, Claggett B, Correia AW, et al. Temporal Trends in the Population Attributable Risk for Cardiovascular Disease: The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study. Circulation. 2014;130:820-828. doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.008506

- Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA guideline for the prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of high blood pressure in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Hypertension. 2018;71(6):1269-1324. doi:10.1161/HYP.0000000000000066

- Leung AA, Daskalopoulou SS, Dasgupta K, et al. Hypertension Canada’s 2017 guidelines for diagnosis, risk assessment, prevention, and treatment of hypertension in adults. Can J Cardiol. 2017;33(5):557-576. doi:10.1016/j.cjca.2017.03.005

- Williams B, Mancia G, Spiering W, et al. 2018 ESC/ESH guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension. Eur Heart J. 2018;39(33):3021-3104. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehy339

- Pappaccogli M, Di Monaco S, Perlo E, et al. Comparison of automated office blood pressure with office and out-off-office measurement techniques. Hypertension. 2019;73(2):481-490. doi:10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.118.12079

- Roerecke M, Kaczorowski J, Myers MG. Comparing automated office blood pressure readings with other methods of blood pressure measurement for identifying patients with possible hypertension - a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179:351-362. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.6551

- Kaczorowski J, Chambers LW, Karwalajtys T, et al. Cardiovascular Health Awareness Program (CHAP): a community cluster-randomised trial among elderly Canadians. Prev Med. 2008;46(6):537-544. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2008.02.005

- SPRINT Research Group. A randomized trial of intensive versus standard blood-pressure control. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(22):2103-2116. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1511939

- Andreadis EA, Agaliotis GD, Angelopoulos ET, et al. Automated office blood pressure and 24-h ambulatory measurements are equally associated with left ventricular mass index. Am J Hypertens. 2011;24(6):661-666. doi:10.1038/ajh.2011.38

- Campbell NRC, McKay DW, Conradson H, et al. Automated oscillometric blood pressure versus auscultatory blood pressure as a predictor of carotid intima-medial thickness in male firefighters. J Hum Hypertens. 2007;21(7):588-590. doi:10.1038/sj.jhh.1002190

- Myers MG, Godwin M, Dawes M et al. Conventional versus automated measurement of blood pressure in primary care patients with systolic hypertension: randomised parallel design controlled trial. BMJ. 2011;342:d286. doi:10.1136/bmj.d286

- Beckett L, Godwin M. The BpTRU automatic blood pressure monitor compared to 24 hour ambulatory blood pressure monitoring in the assessment of blood pressure in patients with hypertension. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2005;5(1):18. doi:10.1186/1471-2261-5-18

- Myers MG, Valdivieso M, Kiss A. Use of automated office blood pressure measurement to reduce the white coat response. J Hypertens. 2009;27(2):280-286. doi:10.1097/HJH.0b013e32831b9e6b

- Myers MG, Valdivieso M, Kiss A. Consistent relationship between automated office blood pressure recorded in different settings. Blood Press Monit. 2009;14(3):108-111. doi:10.1097/MBP.0b013e32832c5167

- Myers MG, Valdivieso M, Kiss A. Optimum frequency of office blood pressure measurement using an automated sphygmomanometer. Blood Press Monit. 2008;13(6):333-338. doi:10.1097/MBP.0b013e3283104247

- Myers MG. A proposed algorithm for diagnosing hypertension using automated office blood pressure measurement. J Hypertens. 2010;28(4):703-708. doi:10.1097/HJH.0b013e328335d091

- Godwin M, Birtwhistle R, Delva D, et al. Manual and automated office measurements in relation to awake ambulatory blood pressure monitoring. Fam Pract. 2011;28(1):110-117. doi:10.1093/fampra/cmq067

- Myers MG, Valdivieso M, Chessman M, Kiss A. Can sphygmomanometers designed for self-measurement of blood pressure in the home be used in office practice? Blood Press Monit. 2010;15(6):300-304. doi:10.1097/MBP.0b013e328340d128

- Leung AA, Nerenberg K, Daskalopoulou SS, et al. Hypertension Canada’s 2016 Canadian hypertension education program guidelines for blood pressure measurement, diagnosis, assessment of risk, prevention, and treatment of hypertension. Can J Cardiol. 2016;32(5):569-588. doi:10.1016/j.cjca.2016.02.066

- Myers MG. A short history of automated office blood pressure - 15 years to SPRINT. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2016;18(8):721-724. doi:10.1111/jch.12820

- Myers MG, Kaczorowski J, Dawes M, Godwin M. Automated office blood pressure measurement in primary care. Can Fam Physician. 2014;60(2):127-132.

- Armstrong D, Matangi M, Brouillard D, Myers MG. Automated office blood pressure - being alone and not location is what matters most. Blood Press Monit. 2015;20(4):204-208. doi:10.1097/MBP.0000000000000133

- Yarows SA. What is the Cost of Measuring a Blood Pressure? Ann Clin Hypertens. 2018;2:59-66. doi:10.29328/journal.ach.1001012

- Cabana MD, Rand CS, Powe NR, et al. Why don’t physicians follow clinical practice guidelines? A framework for improvement. JAMA. 1999;282(15):1458-1465. doi:10.1001/jama.282.15.1458

- Doane J, Buu J, Penrod MJ, et al. Measuring and managing blood pressure in a primary care setting: a pragmatic implementation study. J Am Board Fam Med. 2018;31(3):375-388. doi:10.3122/jabfm.2018.03.170450

Assessment of Automated vs Conventional Blood Pressure Measurements in a Veterans Affairs Clinical Practice Setting

Assessment of Automated vs Conventional Blood Pressure Measurements in a Veterans Affairs Clinical Practice Setting